Abstract

Background and objectives

Prior studies have shown that the APOL1 risk alleles are associated with a greater risk of HIV-associated nephropathy and FSGS among blacks who are HIV positive. We sought to determine whether the APOL1 high–risk genotype incrementally improved the prediction of these underlying lesions beyond conventional clinical factors.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In a cross-sectional study, we analyzed data from 203 blacks who are HIV positive, underwent kidney biopsies between 1996 and 2011, and were genotyped for the APOL1 G1 and G2 alleles. Predictive logistic regression models with conventional clinical factors were compared with those that also included APOL1 genotype using receiver-operating curves and bootstrapping analyses with crossvalidation.

Results

The addition of APOL1 genotype to HIV–related risk factors for kidney disease in a predictive model improved the prediction of non–HIV–associated nephropathy FSGS, specifically, increasing the c statistic from 0.65 to 0.74 (P=0.04). Although two risk alleles were significantly associated with higher odds of HIV-associated nephropathy, APOL1 genotype did not add incrementally to the prediction of this specific histopathology.

Conclusions

APOL1 genotype may provide additional diagnostic information to traditional clinical variables in predicting underlying FSGS spectrum lesions in blacks who are HIV positive. In contrast, although APOL1 risk genotype predicts HIV-associated nephropathy, it lacked a high c statistic sufficient for discrimination to eliminate the role of kidney biopsy in the clinical care of blacks who are HIV positive with nephrotic proteinuria or unexplained kidney disease.

Keywords: HIV; APOL1; AIDS-associated nephropathy; African Americans; alleles; biopsy; genotype; glomerulosclerosis, focal segmental; humans; kidney diseases

Introduction

Blacks face a much greater risk of developing kidney disease and progressing to ESRD in the context of HIV infection, particularly HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), compared with whites (1). This population difference in CKD persists, despite greater availability and earlier initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (2). Recent studies have identified variants in the APOL1 gene encoding ApoL1, which have risen to high allele frequency in sub–Saharan African populations and are strongly associated with population differences of CKD risk in HIV–positive as well as HIV–negative patient cohorts with various etiologies of CKD (3,4). The G1 allele consists of the two single–nucleotide polymorphisms rs73885319 and rs60910145, whereas the G2 allele consists of a 6-bp deletion, rs71785313. Kopp et al. (5) subsequently showed that individuals who are HIV positive carrying two copies of the risk alleles are at 29-fold higher odds of HIVAN compared with individuals with one/no risk allele, and the odds ratio rises to 89 in South Africa (6). We additionally observed that, among individuals who are HIV positive with biopsy–proven non–HIVAN kidney disease, a greater proportion of individuals with two risk alleles had FSGS versus immune complex GN (7).

Previous studies have not examined whether knowledge of APOL1 genotype incrementally improves the prediction of the underlying renal histopathology above conventional clinical factors, such as HIV viremia and proteinuria severity. Knowledge of APOL1 genotype may have implications for renal disease monitoring and timing of combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) initiation among individuals of African descent who are HIV positive. Moreover, given the high odds ratio for association of the APOL1 risk variants with non-HIVAN forms of CKD, especially FSGS, there will likely be cohorts of individuals who are HIV positive and have APOL1–associated non–HIVAN FSGS. In this study, we generated predictive models for non-HIVAN FSGS and HIVAN, which include APOL1 genotype, and evaluated their predictive performance among individuals who are HIV positive with biopsy–proven kidney disease.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This study was a retrospective study of blacks who are HIV positive ages 21 years old or older who underwent clinically indicated percutaneous native kidney biopsies between January of 1996 and June of 2011. Among those who underwent multiple renal biopsies, only specimens from the first biopsy were included. The study population included 216 individuals (but ultimately 203): (1) 98 individuals previously described who had sufficient kidney tissue available, non-HIVAN histopathology, and previously underwent successful genotyping for the APOL1 G1 and G2 variants (8); (2) 60 individuals previously described with HIVAN histopathology who previously underwent successful genotyping for the APOL1 G1 and G2 single–nucleotide polymorphisms (8); and (3) an additional 58 individuals subsequently identified as having undergone kidney biopsies. Of the third group, 13 individuals did not have sufficient clinical data available, leaving 45 individuals with kidney biopsy and clinical data. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and undertaken in accordance with the principles of the Declarations of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board waived the requirement for informed consent of this study.

Histopathologic Review of Kidney Biopsy Specimens

The original pathology slides were reviewed by a pathologist masked to the genotype and compared with the original pathology reports. If the review findings differed from the original report, a second pathologist also masked to the genotype reviewed the slides and finalized the diagnosis. This occurred for only one patient, where the original diagnosis was arterionephrosclerosis and replaced with FSGS on review. HIVAN diagnoses were on the basis of the presence of collapsing glomerulosclerosis, microcystic tubular dilation, and tubulointerstitial inflammation on light microscopy and diffuse foot process effacement on electron microscopy.

The presence of segmental glomerular sclerosis in the absence of any glomerular collapse or microcystic tubular dilation defined FSGS. Histopathologic findings were categorized into HIVAN, non-HIVAN FSGS, and other diagnoses.

DNA Extraction from Formalin–Fixed, Paraffin–Embedded Tissue

The DNA extraction methods used for the patients with non-HIVAN and the patients with HIVAN included in previous studies by our group were described in detail elsewhere (7,8). For the additional kidney biopsies, tissue sections 5- to 10-µm thick were obtained from formalin–fixed, paraffin–embedded tissues. Genomic DNA was extracted using the QuickExtract FFPE DNA Extraction Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was concentrated using DNA Clean & Concentrator 5 (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Genotyping for APOL1 High–Risk Alleles

The methods used to genotype APOL1 variants G1 (rs73885319 and rs60910145) and G2 (rs71785313) alleles in the patients with initial non-HIVAN or HIVAN included in our prior studies were detailed previously (7,8). Briefly, some participants underwent genotyping by Taqman Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), whereas others were genotyped using direct sequencing and high–resolution melting assay. The additional participants new to this study were also genotyped using direct Sanger sequencing and high–resolution melting assay as previously reported (7).

Covariates

Sociodemographic (age and sex), clinical, and laboratory data at the time of the kidney biopsy were abstracted from electronic health records. Clinical data abstracted included hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, history of diabetes mellitus or hypertension, clinical AIDS, and cART exposure. We also abstracted for the following laboratory data at the time of kidney biopsy: HCV antibody status, CD4+ cell count, HIV-1 RNA level, serum creatinine, urine protein, and urine creatinine. HIV viral suppression was defined as a viral load <400 copies/ml. eGFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Equation (9), whereas proteinuria at the time of kidney biopsy was estimated using a random urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.

Statistical Analyses

Variables with skewed distributions were log transformed. Baseline characteristics were compared according to the number of APOL1 risk alleles using the Kruskal–Wallis test, chi-squared test, or Fisher exact test as appropriate. To estimate the odds of having either FSGS or HIVAN and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), we used univariable logistic regression models. Covariates that had a P value of <0.05 on univariable analyses were included in the multivariable logistic regression model. A second model was constructed that included these covariates as well as APOL1 genotype modeled as two risk alleles versus one or no risk allele. This is consistent with prior observations of significant disease association under a two–risk allele inheritance model (3,8,10). A separate model, which is predictive of performance of multivariable models with and without APOL1 to estimate the odds of having either FSGS or HIVAN, was also constructed. We also constructed a model to assess the predictive performance of multivariable models with and without APOL1 after considering HIVAN and non-HIVAN FSGS as one entity. To examine the relative predictive performance of multivariable models with and without APOL1 genotyping, we conducted receiver–operating curve analyses and compared the c statistics. The predictive performance of multivariable models with and without APOL1 was also remodeled using bootstrapping technique with 100 random sampling and replacement iterations. Finally, we validated the predictive model containing APOL1 genotype by crossvalidation, in which we randomly divided the study population into ten equal subsamples. For each of ten rounds of crossvalidation, nine subsamples were used as the training set, whereas the tenth subsample was used as the validation set. The mean c statistic across all of the rounds of crossvalidation was calculated. In addition, we evaluated the predictive performance of each variable within the multivariable model containing APOL1 genotyping by comparing the c statistics for each variable. Separate parallel analyses were conducted to determine the performance of a model to predict each non-HIVAN FSGS and HIVAN specifically.

Results

Study Population Characteristics

Of 216 blacks who are HIV positive who underwent clinically indicated kidney biopsies, 203 were successfully genotyped for the APOL1 G1 and G2 alleles and had clinical data available from the time of biopsy. Of these individuals, 70 (34%) carried two risk alleles, whereas 86 (42%) had one risk allele, and 47 (23%) carried no risk alleles. Table 1 displays the study population characteristics by the number of APOL1 risk alleles. Patients carrying two risk alleles were younger and less likely to have a history of diabetes mellitus. They were also less likely to be HCV antibody positive. The proportion of patients with HIV-1 RNA levels <400 copies/ml at the time of biopsy was similar by APOL1 genotype (P=0.31). In contrast, those with two or one risk allele generally had lower median (interquartile range [IQR]) CD4+ cell counts (184; IQR, 47–340 and 155; IQR, 50–309 cells/mm3, respectively) at the time of biopsy compared with those with no risk allele (341; IQR, 241–479 cells/mm3; P<0.001). The median eGFR (IQR) among those with two APOL1 risk alleles was 24.1 (IQR, 11.9–29.2) ml/min per 1.73 m2 compared with 35.5 (IQR, 15.5–58.7) and 44.3 (IQR, 33.6–59.4) ml/min per 1.73 m2 among those carrying one or no risk alleles, respectively (Ptrend=0.001). The median (IQR) level of proteinuria, assessed as protein-to-creatinine ratio, was higher among patients having two risk alleles (2.7; IQR, 1.0–7.0 g/g) compared with those carrying one (1.6; IQR, 0.34–4.6 g/g) or no risk alleles (0.8; IQR, 0.14–2.7 g/g; Ptrend=0.01).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants at the time of kidney biopsy by APOL1 genotype

| Characteristic | No Risk Allele | One Risk Allele | Two Risk Alleles | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 47 | 86 | 70 | |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 49 (7) | 47 (9) | 43 (9) | 0.003 |

| Women, n (%) | 18 (38) | 29 (34) | 27 (39) | 0.87 |

| Injection drug use (N=199), n (%) | 26 (57) | 53 (62) | 31 (46) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus (N=198), n (%) | 19 (41) | 16 (19) | 7 (10) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 32 (68) | 46 (53) | 42 (61) | 0.27 |

| HCV antibody positive, n (%) | 24 (51) | 55 (64) | 30 (43) | 0.03 |

| Antiretroviral treatment (N=197), n (%) | 20 (43) | 37 (44) | 25 (37) | 0.69 |

| ACE inhibitor use (N=153), n (%) | 9 (3) | 8 (13) | 8 (13) | 0.11 |

| Median HIV-1 RNA level, 1000 copies/ml (IQR) | 1.4 (0.005–98.8) | 33.1 (0.59–270.3) | 20.9 (0.40–227.0) | 0.09 |

| HIV-1 RNA level <400 copies/ml | 16 (39) | 20 (26) | 15 (28) | 0.31 |

| Median CD4 cell count, cells per mm3 (IQR) | 341 (241–479) | 155 (50–309) | 184 (47–340) | <0.001 |

| Median serum creatinine, mg/dl (IQR) | 1.9 (1.5–2.6) | 2.4 (1.6–4.3) | 3.1 (2.1–5.8) | <0.001 |

| Median eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 (IQR) | 44.3 (33.6–59.4) | 35.5 (15.5–58.7) | 24.1 (11.9–29.2) | 0.001 |

| Median proteinuria, g/g (IQR) | 0.79 (0.14–2.7) | 1.6 (0.34–4.6) | 2.7 (1.0–7.0) | <0.01 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; IQR, interquartile range.

Development and Performance of the Predictive Model for Non–HIVAN FSGS Histopathology

In the univariable model, the presence of two risk alleles was associated with nearly threefold higher odds of non-HIVAN FSGS (odds ratio, 2.95; 95% CI, 1.48 to 5.84) (Table 2). With the addition of the APOL1 genotype in a multivariable model, higher CD4+ cell count was associated with 1.48-fold higher odds of non-HIVAN FSGS (95% CI, 1.04 to 2.10).

Table 2.

Odds of non–HIV–associated nephropathy FSGS histopathology

| Variables at the Time of Kidney Biopsy | Multivariable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable (n=203) | Model without APOL1 (n=168)a | Model with APOL1 (n=168)a | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age, per 10 yr older | 1.34 | 0.91 to 1.97 | 0.13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Women | 0.51 | 0.24 to 1.08 | 0.08 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Injection drug use | 0.96 | 0.48 to 1.89 | 0.91 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CD4 count, per 1 log higher | 1.47 | 1.10 to 1.97 | 0.01 | 1.32 | 0.96 to 1.81 | 0.09 | 1.48 | 1.04 to 2.10 | 0.03 |

| HIV-1 RNA <400 copies/ml | 2.42 | 1.18 to 4.99 | 0.02 | 1.78 | 0.81 to 3.91 | 0.15 | 1.89 | 0.82 to 4.37 | 0.13 |

| Proteinuria, per 1 log higher | 0.90 | 0.75 to 1.08 | 0.25 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| eGFR, per 10 ml higher | 1.01 | 0.90 to 1.13 | 0.84 | ||||||

| HCV antibody positive | 0.73 | 0.37 to 1.42 | 0.34 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| APOL1 risk alleles, two versus zero or one | 2.95 | 1.48 to 5.84 | 0.002 | NA | NA | NA | 5.25 | 2.37 to 11.62 | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not applicable; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Variables with P values <0.05 in univariable analyses were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model.

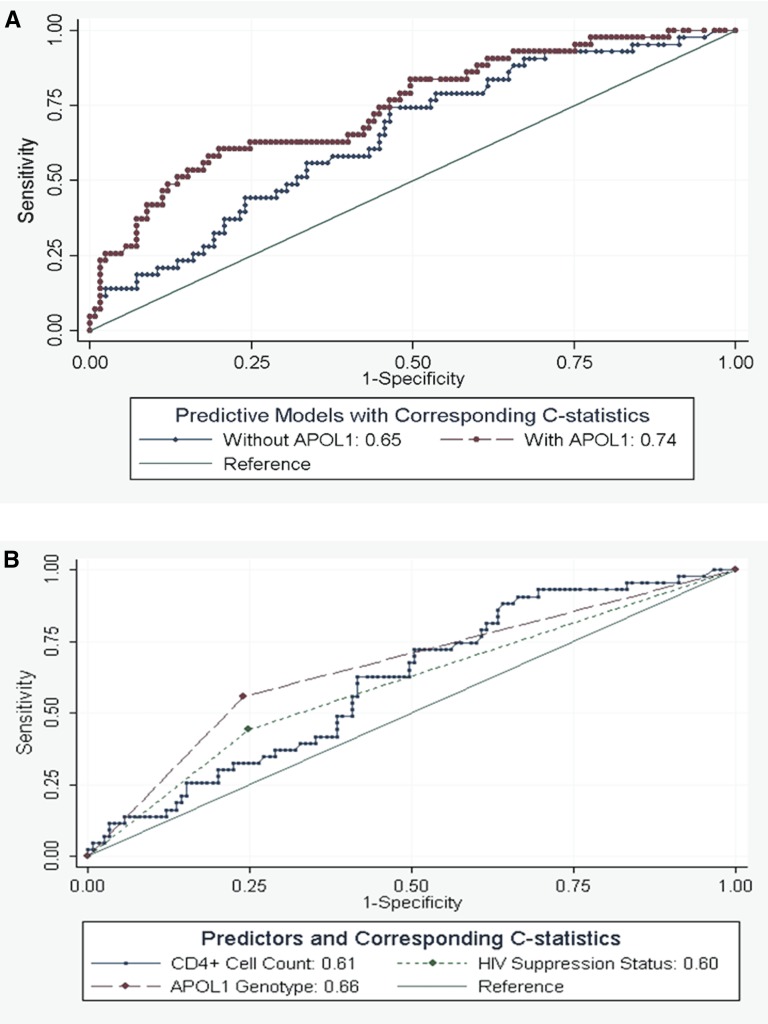

As displayed in Figure 1A, inclusion of the APOL1 genotype in the predictive model improved the prediction of non–HIVAN FSGS histopathology from a c statistic of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.55 to 0.74) to 0.74 (95% CI, 0.65 to 0.83; P=0.04); a similar estimate was obtained with crossvalidation. Similarly, bootstrapping showed that including APOL1 genotype incrementally improved the prediction of non–HIVAN FSGS histopathology (Table 3) from a c statistic of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.74) to 0.74 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.83). Figure 1B shows that, although APOL1 genotype seemed the strongest predictor of non–HIVAN FSGS histopathology (c statistic =0.66; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.75) compared with viral suppression status and CD4+ cell count (c statistic =0.60; 95% CI, 0.51 to 0.68 and c statistic =0.61; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.70, respectively), these differences did not reach statistical significance (P=0.59).

Figure 1.

Receiver-operating curves of predictive models and their corresponding c statistics of non–HIV–associated nephropathy FSGS. (A) Both models include CD4+ cell count and HIV suppression status. P<0.04 for differences in c statistics between the model without and with APOL1 genotype. (B) Shown are the receiver operating curves for CD4+ cell count, HIV suppression status, and APOL1 genotype. All curves are on the basis of multivariable models.

Table 3.

Bootstrap predictive model of renal histology with and without APOL1 with 100 random samples and replacement

| Histological Category | Observations | ROC Area | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-HIVAN FSGS without APOL1 | 168 | 0.65 | 0.56 to 0.74 |

| Non-HIVAN FSGS with APOL1 | 168 | 0.74 | 0.66 to 0.83 |

| HIVAN without APOL1 | 157 | 0.86 | 0.81 to 0.92 |

| HIVAN with APOL1 | 157 | 0.87 | 0.82 to 0.93 |

| HIVAN and FSGS without APOL1 | 167 | 0.72 | 0.64 to 0.80 |

| HIVAN and FSGS with APOL1 | 167 | 0.82 | 0.75 to 0.88 |

ROC, receiver-operating curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HIVAN, HIV-associated nephropathy.

Development and Performance of the Predictive Model for HIVAN Histopathology

To determine whether APOL1 genotype incrementally improved the prediction of HIVAN histopathology, we next developed a separate set of models without and with APOL1 genotype (Table 4). In univariable models, two APOL1 risk alleles were associated with 4.5-fold higher odds of HIVAN compared with one or no risk alleles (95% CI, 2.41 to 8.44). In the multivariable model with APOL1 genotype, two risk alleles were associated with threefold higher odds of HIVAN (95% CI, 1.20 to 7.59) compared with one or no risk alleles; however, this did not reach statistical significance when the analysis was restricted to individuals with viral suppression at the time of biopsy (odds ratio, 2.07; 95% CI, 0.11 to 38.86).

Table 4.

Odds of HIV–associated nephropathy histopathology

| Variables at the Time of Kidney Biopsy | Multivariable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable (n=203) | Model without APOL1 (n=158)a | Model with APOL1 (n=158)a | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age, per 10 yr older | 0.42 | 0.28 to 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.31 to 1.08 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.35 to 1.28 | 0.23 |

| Women | 1.63 | 0.90 to 2.97 | 0.11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Injection drug use | 1.15 | 0.63 to 2.09 | 0.65 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CD4+ count, per 1 log higher | 0.58 | 0.47 to 0.73 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.51 to 0.90 | <0.01 | 0.67 | 0.50 to 0.90 | <0.01 |

| HIV-1 RNA <400 copies/ml | 0.11 | 0.03 to 0.39 | 0.001 | 0.31 | 0.07 to 1.26 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.06 to 1.10 | 0.07 |

| Proteinuria, per 1 log higher | 2.07 | 1.55 to 2.76 | <0.001 | 1.57 | 1.10 to 2.25 | 0.01 | 1.62 | 1.10 to 2.37 | 0.01 |

| eGFR, per 10 ml higher | 0.66 | 0.55 to 0.80 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.66 to 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.68 to 1.04 | 0.11 |

| HCV antibody positive | 0.82 | 0.46 to 1.48 | 0.52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| APOL1 risk alleles, two versus zero or one | 4.51 | 2.41 to 8.44 | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA | 3.01 | 1.20 to 7.59 | 0.02 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not applicable; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Variables with P values <0.05 in univariable analyses were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model.

The addition of APOL1 genotype to the model including conventional clinical factors did not improve prediction of HIVAN (c statistic =0.87 versus 0.86; P=0.47). The two strongest predictors were APOL1 genotype (c statistic =0.65; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.74) and proteinuria severity at the time of biopsy (c statistic =0.77; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.85). Similar results were obtained from the bootstrapping technique shown in Table 3.

As displayed in Table 5, combining patients with HIVAN and patients with FSGS significantly increased the predictive power of the APOL1 genotype. In this multivariable model, two risk alleles were associated with 11-fold higher odds of combined HIVAN and FSGS. The addition of APOL1 genotype to the model significantly improved prediction of combined HIVAN and FSGS from a c statistic of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.64 to 0.79) to 0.82 (95% CI, 0.75 to 0.88; P=0.001). Similar estimates were obtained from bootstrapping as displayed in Table 3.

Table 5.

Odds of HIV-associated nephropathy and non–HIV–associated nephropathy FSGS histopathology

| Variables at the Time of Kidney Biopsy | Multivariable | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable (n=203) | Model without APOL1 (n=167)a | Model with APOL1 (n=167)a | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age, per 10 yr older | 0.61 | 0.43 to 0.85 | 0.004 | 0.68 | 0.43 to 1.05 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.49 to 1.36 | 0.44 |

| Women | 1.01 | 0.57 to 1.80 | 0.96 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Injection drug use | 1.10 | 0.63 to 1.93 | 0.73 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CD4 count, per 1 log higher | 0.75 | 0.61 to 0.93 | <0.01 | 0.85 | 0.67 to 1.08 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.64 to 1.08 | 0.17 |

| HIV-1 RNA <400 copies/ml | 0.62 | 0.32 to 1.20 | 0.16 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Proteinuria, per 1 log higher | 1.41 | 1.18 to 1.70 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.96 to 1.45 | 0.11 | 1.19 | 0.95 to 1.50 | 0.13 |

| eGFR, per 10 ml higher | 0.79 | 0.70 to 0.90 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.75 to 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.76 to 1.02 | 0.10 |

| HCV antibody positive | 0.67 | 0.38 to 1.18 | 0.17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| APOL1 risk alleles, two versus zero or one | 15.4 | 6.55 to 36.34 | <0.001 | NA | NA | NA | 11.19 | 4.26 to 29.41 | <0.001 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not applicable; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Variables with P values <0.05 in univariable analyses were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model.

Discussion

In this study of blacks who are HIV positive undergoing kidney biopsy, the addition of APOL1 genotype to clinical factors in a predictive model significantly improved the prediction of non-HIVAN FSGS. However, although two risk alleles were significantly associated with HIVAN, APOL1 genotype specifically did not add incrementally to the prediction of this histology beyond traditional CKD– and HIV–related risk factors. These results suggest that APOL1 risk genotype predicts non-HIVAN FSGS and HIVAN but not with sufficient discrimination to obviate a renal biopsy, particularly in the diagnosis of the most aggressive form, HIVAN, in blacks who are HIV positive.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the potential role of the APOL1 risk alleles in the context of traditional noninvasive clinical measurements in predicting underlying kidney pathology in this patient population at high risk for kidney disease. Most prior studies of APOL1 and kidney disease in HIV infection have included individuals who are HIV negative with FSGS or else focused primarily on HIVAN histopathology among individuals who are HIV positive (5,11). Papeta et al. (11) compared 44 individuals who are HIV negative with FSGS with 21 individuals who are HIV negative with HIVAN, 32 individuals who are HIV negative with IgA nephropathy, and 74 healthy controls and found that APOL1 risk alleles were associated with a 2.1- to 2.7-fold higher odds for FSGS and HIVAN but not IgA nephropathy. In comparing blacks with FSGS or HIVAN with whites with similar pathology and healthy controls, Kopp et al. (5) observed a similar association between APOL1 risk alleles; however, the reported odds ratios for FSGS or HIVAN far exceeded those reported by Papeta et al. (11) (odds ratio, 17 for FSGS in individuals who are HIV negative and odds ratio, 29 for HIVAN individuals who are HIV negative). In a previous study comprised of blacks who are HIV positive with only non-HIVAN disease, we showed that a greater proportion of participants carrying two risk alleles had FSGS (7). This study builds on this prior observation and shows the ability of APOL1 risk alleles to improve the prediction of underlying pathology beyond traditional clinical factors.

Observational studies in the HIV-negative population with kidney disease indicate that the APOL1 risk alleles play a role in CKD progression (10,12). However, the APOL1 risk alleles have also been associated with higher odds for early kidney disease among individuals who are HIV negative as well as individuals who are HIV positive (13–15). Moreover, studies of HIV-positive populations suggest that HIV itself augments the detrimental effects of the APOL1 risk alleles on the kidneys (16). The exact mechanisms by which the risk alleles lead specifically to glomerulosclerotic lesions and of how HIV interacts with APOL1 remain unclear. APOL1 circulates in the extracellular milieu and is also expressed intracellularly (17,18). Early experiments showed that upregulation of APOL1 expression is induced by TNF (16,19); however, circulating APOL1 levels did not correlate with cytokine levels in recent comparisons among blacks who are HIV positive with CKD (20). Although this area remains a focus of intense investigation, additional mechanistic studies are needed to determine the importance of intracellular APOL1 expression in kidney disease. An early study suggests that APOL1 is expressed in podocytes, but the number of cells expressing the protein was reported to be reduced in FSGS and HIVAN compared with healthy controls (21). A recent study by Taylor et al. (22) also implicates that intracellular APOL1 expression in macrophages is induced by proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF, in an attempt to suppress viral replication. Increased APOL1 levels may, in turn, lead to collateral damage of renal cells, which have been implicated as reservoirs for HIV (23,24). Whether viral suppression by effective cART lowers APOL1 expression, thereby limiting APOL1-related injury in HIVAN, requires additional study. In addition, whether the variant APOL1 encoded by the APOL1 risk alleles influences HIV disease progression remains to be determined.

In contrast to our findings with non-HIVAN FSGS, the APOL1 genotype did not seem to improve the prediction of HIVAN alone (unless it was combined with FSGS) beyond traditional clinical factors, such as viremia or proteinuria, although the presence of two risk alleles was associated with three-fold higher odds of HIVAN. This may be attributed to the known independent association of APOL1 risk alleles with non-HIVAN FSGS also, such that individuals who are HIV positive included in the study would also be at risk for both HIVAN and non-HIVAN FSGS. This finding highlights the necessity for kidney biopsy to exclude this aggressive form of kidney disease in this population. Despite our findings, APOL1 genotyping may still have clinical implications with regards to the timing of cART initiation in blacks who are HIV positive; however, trials are needed to determine whether cART initiation at higher CD4+ cell counts ameliorates early kidney disease, such as proteinuria, among HIV–positive risk allele carriers. As expected, lower CD4 count was associated with HIVAN, whereas surprisingly, higher CD4 count was associated with other kidney disorders, including non-HIVAN FSGS. These disorders may have the opportunity to emerge over the course of time in immunocompetent individuals when factors believed to be critical for HIVAN pathophysiology, particularly the presence of HIV gene products and cytokine dysregulation, are not present. It is also potentially possible that non-HIVAN FSGS is representative of an early or treated HIVAN.

Although our study represents the largest study to date that evaluates the association between the APOL1 risk alleles and biopsy–proven kidney disease among blacks who are HIV positive, there are several noteworthy limitations. First, our results are specific to blacks who are HIV positive and at high risk for kidney disease and are not generalizable to HIV-negative populations. Second, the study population was comprised of patients who had undergone a clinically indicated kidney biopsy and therefore, may not be representative of all blacks who are HIV positive with kidney disease, many of whom do not undergo kidney biopsy. Therefore, this study cohort, by virtue of having undergone clinically indicated kidney biopsy, is likely to have more severe kidney disease, which in turn, may modify the distribution of underlying diagnoses. This is important in consideration of the possible relationship of HIV infection to non-HIVAN FSGS. Nonetheless, the availability of a large number of individuals with kidney biopsy results affords an opportunity to thoroughly examine the association between APOL1 risk alleles and underlying renal pathology. Third, although we internally validated our predictive models through cross-validation, we did not have an external study population available in which to evaluate the performance of the predictive models. Fourth, the lack of information on hematuria as an important predictor of non-FSGS histology may have limited the results of our predictive model.

In summary, this study shows that, although the addition of APOL1 genotyping to traditional clinical factors significantly improves the prediction of underlying histopathology of non-HIVAN FSGS, it failed to increase the predictive value of the most aggressive form, HIVAN, among blacks who are HIV positive with kidney disease. However, the predicative value of APOL1 genotype is significantly improved if HIVAN and FSGS are considered one entity. As such, our results suggest the potential role of APOL1 genotyping in the diagnosis of specific HIV–related kidney disease if validated in other populations of blacks who are HIV positive. Kidney biopsy, however, remains central to accurate diagnosis of kidney disease in this population with severe kidney disease. Additional studies are also needed to determine whether APOL1 genotyping predicts blacks who are HIV positive and would benefit from earlier initiation of cART to prevent not only HIVAN but also, early kidney disease.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded, in part, with federal funds from National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Contract HHSN26120080001E. This research was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, Center for Cancer Research and the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), NIH. M.G.A. and D.M.F. are supported by NIH/NIDDK Grant P01DK056492. M.M.E. is supported by NIH/NIDDK Grant K23DK081317. M.M.E. and G.M.L. are supported by Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research Grant P30AI094189. K.S. and D.M.F. are supported by a grant from the Johns Hopkins-Technion Program of the American Technion Society. K.S. is supported by Israel Science Foundation Grant 2013504 and the Ernest and Bonnie Beutler Grant Program at Rambam Health Care Campus. G.M.L. is supported by NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grants K24DA035684 and R01DA026770.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Lucas GM, Lau B, Atta MG, Fine DM, Keruly J, Moore RD: Chronic kidney disease incidence, and progression to end-stage renal disease, in HIV-infected individuals: A tale of two races. J Infect Dis 197: 1548–1557, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham AG, Althoff KN, Jing Y, Estrella MM, Kitahata MM, Wester CW, Bosch RJ, Crane H, Eron J, Gill MJ, Horberg MA, Justice AC, Klein M, Mayor AM, Moore RD, Palella FJ, Parikh CR, Silverberg MJ, Golub ET, Jacobson LP, Napravnik S, Lucas GM, North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) : End-stage renal disease among HIV-infected adults in North America. Clin Infect Dis 60: 941–949, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, Bernhardy AJ, Hicks PJ, Nelson GW, Vanhollebeke B, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Pays E, Pollak MR: Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 329: 841–845, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, Yudkovsky G, Selig S, Tarekegn A, Bekele E, Bradman N, Wasser WG, Behar DM, Skorecki K: Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet 128: 345–350, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, Johnson RC, Genovese G, An P, Friedman D, Briggs W, Dart R, Korbet S, Mokrzycki MH, Kimmel PL, Limou S, Ahuja TS, Berns JS, Fryc J, Simon EE, Smith MC, Trachtman H, Michel DM, Schelling JR, Vlahov D, Pollak M, Winkler CA: APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2129–2137, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasembeli AN, Duarte R, Ramsay M, Mosiane P, Dickens C, Dix-Peek T, Limou S, Sezgin E, Nelson GW, Fogo AB, Goetsch S, Kopp JB, Winkler CA, Naicker S: APOL1 risk variants are strongly associated with HIV-associated nephropathy in black South Africans. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2882–2890, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine DM, Wasser WG, Estrella MM, Atta MG, Kuperman M, Shemer R, Rajasekaran A, Tzur S, Racusen LC, Skorecki K: APOL1 risk variants predict histopathology and progression to ESRD in HIV-related kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 343–350, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atta MG, Estrella MM, Kuperman M, Foy MC, Fine DM, Racusen LC, Lucas GM, Nelson GW, Warner AC, Winkler CA, Kopp JB: HIV-associated nephropathy patients with and without apolipoprotein L1 gene variants have similar clinical and pathological characteristics. Kidney Int 82: 338–343, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, Feldman HI, Parekh RS, Kusek JW, Greene TH, Fink JC, Anderson AH, Choi MJ, Wright JT, Jr., Lash JP, Freedman BI, Ojo A, Winkler CA, Raj DS, Kopp JB, He J, Jensvold NG, Tao K, Lipkowitz MS, Appel LJ, AASK Study Investigators. CRIC Study Investigators : APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2183–2196, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papeta N, Kiryluk K, Patel A, Sterken R, Kacak N, Snyder HJ, Imus PH, Mhatre AN, Lawani AK, Julian BA, Wyatt RJ, Novak J, Wyatt CM, Ross MJ, Winston JA, Klotman ME, Cohen DJ, Appel GB, D’Agati VD, Klotman PE, Gharavi AG: APOL1 variants increase risk for FSGS and HIVAN but not IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1991–1996, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, Astor BC, Grams M, Franceschini N, Boerwinkle E, Parekh RS, Kao WH: APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1484–1491, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Turner J, Núñez M, High KP, Spainhour M, Hicks PJ, Bowden DW, Reeves-Daniel AM, Murea M, Rocco MV, Divers J: Association of APOL1 variants with mild kidney disease in the first-degree relatives of African American patients with non-diabetic end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 82: 805–811, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estrella MM, Wyatt CM, Pearce CL, Li M, Shlipak MG, Aouizerat BE, Gustafson D, Cohen MH, Gange SJ, Kao WH, Parekh RS: Host APOL1 genotype is independently associated with proteinuria in HIV infection. Kidney Int 84: 834–840, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman DJ, Kozlitina J, Genovese G, Jog P, Pollak MR: Population-based risk assessment of APOL1 on renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2098–2105, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopp JB: Rethinking hypertensive kidney disease: Arterionephrosclerosis as a genetic, metabolic, and inflammatory disorder. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 266–272, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page NM, Butlin DJ, Lomthaisong K, Lowry PJ: The human apolipoprotein L gene cluster: Identification, classification, and sites of distribution. Genomics 74: 71–78, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duchateau PN, Pullinger CR, Cho MH, Eng C, Kane JP: Apolipoprotein L gene family: Tissue-specific expression, splicing, promoter regions; discovery of a new gene. J Lipid Res 42: 620–630, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monajemi H, Fontijn RD, Pannekoek H, Horrevoets AJ: The apolipoprotein L gene cluster has emerged recently in evolution and is expressed in human vascular tissue. Genomics 79: 539–546, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruggeman LA, O’Toole JF, Ross MD, Madhavan SM, Smurzynski M, Wu K, Bosch RJ, Gupta S, Pollak MR, Sedor JR, Kalayjian RC: Plasma apolipoprotein L1 levels do not correlate with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 634–644, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madhavan SM, O’Toole JF, Konieczkowski M, Ganesan S, Bruggeman LA, Sedor JR: APOL1 localization in normal kidney and nondiabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2119–2128, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor HE, Khatua AK, Popik W: The innate immune factor apolipoprotein L1 restricts HIV-1 infection. J Virol 88: 592–603, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winston JA, Bruggeman LA, Ross MD, Jacobson J, Ross L, D’Agati VD, Klotman PE, Klotman ME: Nephropathy and establishment of a renal reservoir of HIV type 1 during primary infection. N Engl J Med 344: 1979–1984, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruggeman LA, Ross MD, Tanji N, Cara A, Dikman S, Gordon RE, Burns GC, D’Agati VD, Winston JA, Klotman ME, Klotman PE: Renal epithelium is a previously unrecognized site of HIV-1 infection. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2079–2087, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]