Abstract

Background

Impaired renal function is associated with increased mortality among patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs). The relationship between renal function at time of ICD generator replacement and subsequent appropriate ICD therapies is not known.

Methods and Results

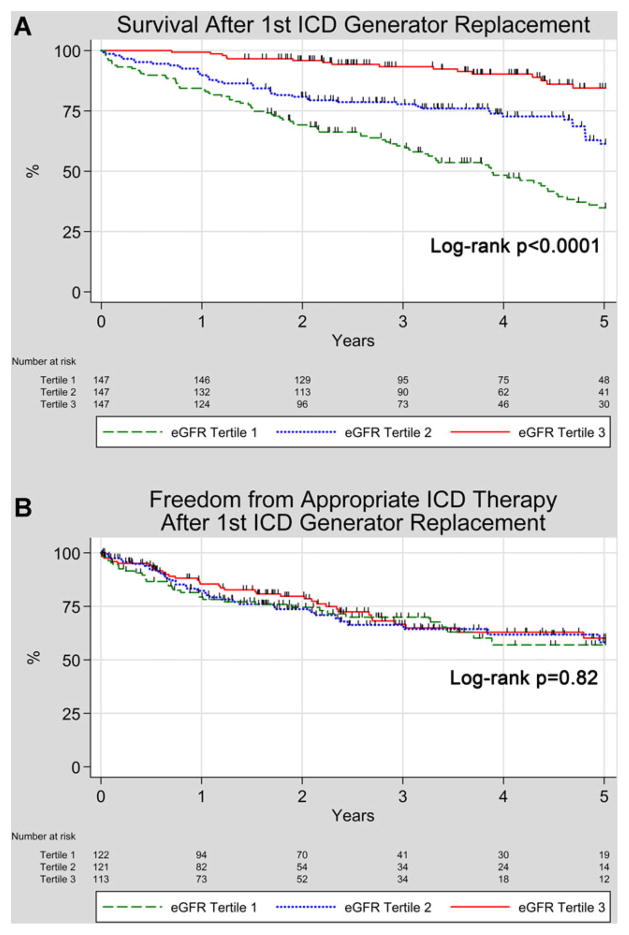

We identified 441 patients who underwent first ICD generator replacement between 2000 and 2011 and had serum creatinine measured within 30 days of their procedure. Patients were divided into tertiles based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Adjusted Cox proportional hazard and competing risk models were used to assess relationships between eGFR and subsequent mortality and appropriate ICD therapy. Median eGFR was 37.6, 59.3, and 84.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 for tertiles 1–3, respectively. Five-year Kaplan–Meier survival probability was 34.8%, 61.4%, and 84.5% for tertiles 1–3, respectively (P < 0.001). After multivariable adjustment, compared to tertile 3, worse eGFR tertile was associated with increased mortality (HR 2.84, 95% CI [1.36–5.94] for tertile 2; HR 3.84, 95% CI [1.81–8.12] for tertile 1). At 5 years, 57.0%, 58.1%, and 60.2% of patients remained free of appropriate ICD therapy in tertiles 1–3, respectively (P = 0.82). After adjustment, eGFR tertile was not associated with future appropriate ICD therapy. Results were unchanged in an adjusted competing risk model accounting for death.

Conclusions

At time of first ICD generator replacement, lower eGFR is associated with higher mortality, but not with appropriate ICD therapies. The poorer survival of ICD patients with reduced eGFR does not appear to be influenced by arrhythmia status, and there is no clear proarrhythmic effect of renal dysfunction, even after accounting for the competing risk of death.

Keywords: creatinine, estimated GFR, generator replacement, heart failure, ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, mortality, renal function

Introduction

Despite significant advances in medicine and technology, sudden cardiac death remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, resulting in approximately 300,000 deaths annually in the United States.1 In properly selected patients with both primary and secondary prevention indications, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) significantly reduce both sudden death and total mortality.2–5 However, given the cost of ICD implantation, the risk of adverse side effects including inappropriate shocks, lead malfunction, and device-related infections,6 and the fact that many patients who get ICDs die from causes unrelated to sudden cardiac death without ever receiving any appropriate ICD therapy, great effort is being made to evaluate the most appropriate and cost effective ways of selecting patients who are most likely to benefit from initial ICD implantation.7,8

The reported median ICD battery lifespan is 4.6 years,9 and many patients will require at least 1 ICD generator replacement in their lifetime. ICD generator replacement is costly and can be associated with significant procedural complications, including bleeding and infection.10 Patients undergoing ICD generator replacement are older, often with progressive or new comorbidities that can limit their functional status, quality of life, and expected longevity compared to their status when their initial ICD was implanted. Despite the significant effort that has been made to select those patients who are the most appropriate candidates for initial ICD implantation, ICD generator replacement often occurs without reconsidering the ongoing appropriateness for ICD therapy.11

Impaired renal function at the time of initial ICD implantation has been shown to predict increased procedural complications12 and increased mortality.8,13–20 Small studies that have evaluated the association between renal function and appropriate ICD therapies after initial ICD implantation have also suggested that impaired renal function is independently associated with a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmias requiring ICD therapy,21–25 although not all reports have confirmed this relationship.26 The correlations between renal function, mortality, and appropriate ICD therapies after ICD generator replacement are not well defined. Because patients at the time of initial ICD implantation are inherently different than patients at the time of ICD generator replacement, the risk factors that are associated with mortality and ventricular arrhythmias at the time of initial ICD implantation may not be valid at the time of ICD generator replacement. We therefore evaluated the association between renal function at the time of first ICD generator replacement and subsequent mortality and ventricular arrhythmias.

Methods

Patient Selection

We searched the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center electrophysiology database to identify all patients who had their first ICD generator replacement performed between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2011. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a serum creatinine (SCr) measured within 30 days of the procedure available in the medical record, and if additional demographic factors (such as age, gender, and race) were available so that estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) could be calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation (see below). If a pre-procedure SCr was not available, a value obtained within 30 days after the procedure was used, although postimplant SCr measurements were excluded if there were significant clinical events between generator replacement and measurement, including hospital admission, procedural complications, or other acute illnesses. Patients who had upgrade of their ICD to a biventricular pacing system were required to have SCr measured prior to generator replacement to avoid confounding by the hemodyanamic effects of biventricular pacing. If multiple SCr values were available, the value obtained closest to generator replacement procedure was used for analysis. Patients were excluded if CKD-EPI eGFR could not be calculated, if the indication for first ICD generator change was ICD infection, or if their device had been extracted prior to reimplantation. Patients with single chamber, dual chamber, and biventricular devices, and any other indication for generator replacement were eligible for inclusion.

Calculation of eGFR

Estimated GFR was calculated according to the CKD-EPI equation as previously described27 using the following equation: eGFR = 141 × min(SCr/κ)α × max(SCr/κ)−1.209 × 0.993 Age × 1.018 (if female) × 1.159 (if African American) where κ = 0.7 for females and 0.9 for males; α = 0.329 for females and −0.411 for males, min indicates the minimum of either the ratio of SCr/κ or 1, and max indicates the maximum of either the ratio of SCr/κ or 1. After eGFR was calculated, patients were divided into eGFR tertiles for further analysis.

Data Collection

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools. All demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed at the time of first ICD generator replacement, with the exception of specific variables related to the time of initial ICD implantation (age at the time of initial ICD implantation and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at the time of initial ICD implantation), via review of the medical record. Measured variables such as New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, echocardiographic parameters, and laboratory values were obtained as close to the time of ICD generator replacement as possible. Laboratory values obtained more than 30 days prior to ICD generator replacement and echocardiographic parameters obtained more than 4 years prior to generator replacement were excluded.

The occurrence of first appropriate ICD therapy and first inappropriate ICD therapy was assessed by review of the medical record and ICD interrogation reports, and direct review of ICD electrograms when available. ICD therapies (including antitachycardia pacing and shocks) were considered appropriate if ICD therapy was triggered by ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF), and inappropriate if an ICD shock was triggered for any other rhythm, inappropriate electromagnetic noise, or lead malfunction, regardless of whether or not the device was functioning properly. Appropriateness of individual ICD therapies was adjudicated by review of the medical record and available intracardiac electrograms by 2 of the authors (J.W.W. and A.E.B). ICD programming and tachyarrhythmia detection parameters were assessed at the time of ICD generator implantation for patients who did not have any appropriate ICD therapies, or at the time of appropriate ICD therapy for those patients who did have appropriate ICD therapy during follow-up. Death was verified by review of the electronic medical record and by searching the Social Security Death Index.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables, reported as a number and percentage of the total, were compared using the Pearson chi-squared test. Continuous variables, reported as the median and interquartile range, were compared using a Kruskal–Wallace test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test when appropriate. To determine the association between eGFR and mortality, univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed with the following variables: eGFR tertile, age, gender, LVEF, NYHA class >II, diabetes, infarct cardiomyopathy, presence of a biventricular ICD, and ICD indication (primary vs. secondary prevention). Patients were censored at the time they were last documented to be alive. To assess the association between eGFR and appropriate ICD therapies, univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed with the following variables: eGFR tertile, LVEF, NYHA class >II, antiarrhythmic therapy, ICD indication, presence of a biventricular ICD, and appropriate ICD therapy for VT/VF prior to first ICD generator replacement. Patients without ICD therapies were censored at the time of their last ICD interrogation, and patients with less than 30 days of ICD follow-up after generator replacement not due to death were excluded from the analysis of ICD therapies. Schoenfeld residuals were used to validate the proportional hazards assumption for each Cox proportional hazards model. A competing risk model accounting for the competing risks of appropriate ICD therapy and mortality was constructed with the following variables: eGFR tertile, age, LVEF, NYHA class >II, antiarrhythmic therapy, ICD indication, presence of a biventricular ICD, and appropriate ICD therapy for VT/VF prior to first ICD generator replacement.

All analyses were performed by the authors using Stata version 12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). All record review and data analyses were performed under the approval of the institutional review board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Six hundred sixty-seven patients had a first ICD generator replacement performed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2011. Of these patients, 8 were excluded because device infection was the indication for their first ICD generator replacement. One hundred fifty-eight patients were excluded because eGFR could not be calculated due to SCr not being measured within 30 days of their procedure. Note that 69.6% of patients had their ICD replaced due to battery depletion, 24.7% had upgrade of their ICD to either a dual chamber or biventricular system, and 19.5% had malfunction of either their initial ICD generator or a pacing/defibrillator lead.

The distribution of eGFRs in the study population is shown in Figure 1, and baseline characteristics of the final cohort of 441 patients by tertile of eGFR are summarized in Table 1. The median eGFR was 37.6 mL/min/1.73 m2 (range 4–47 mL/min/1.73 m2), 59.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 (range 48–71 mL/min/1.73 m2), and 84.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 (range 71–124 mL/min/1.73 m2) for eGFR tertiles 1–3, respectively. Five patients, all in tertile 1, were on dialysis at the time of generator replacement. Patients with worse renal function were older (median age 78.7, 70.9, and 60.4 years, P < 0.0001 for tertiles 1–3, respectively), were more likely to have a biventricular ICD (59.2%, 35.4%, and 23.1%, P < 0.0001 in tertiles 1–3, respectively, and had shorter initial ICD lifetimes (median lifetime 4.2, 5.0, and 5.3 years, P < 0.0001 for tertiles 1–3, respectively). There were no differences between eGFR tertiles in terms of gender, race, or the percentage of patients with a primary prevention indication for their initial ICD. There was no significant difference between eGFR tertiles in the use of β-blockers, but patients with worse eGFR tertile were more likely to be taking antiarrhythmic medications (47.6%, 24.5%, and 23.8% of patients in tertiles 1–3, respectively, P < 0.0001) with the most common medication being amiodarone (77.3%). Patients with worse eGFR tertile were also more likely to have infarct-related cardiomyopathy, worse NYHA functional class, reduced LVEF, and multiple comorbidities including atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, compared to patients with better eGFR tertile.

Figure 1.

Distribution of estimated GFR values at the time of first ICD generator replacement. CKD-EPI = Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics Stratified by CKD-EPI eGFR Tertiles

| Characteristic | All Patients n = 441 |

eGFR Tertile 1 n = 147 |

eGFR Tertile 2 n = 147 |

eGFR Tertile 3 n = 147 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKD-EPI eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 59.3 (42.4–79.0) | 37.6 (28.1–42.4) | 59.3 (54.2–65.1) | 84.8 (79.0–95.8) | 0.0001 |

| Creatinine (g/mL) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.7 (1.5–2.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 0.0001 |

| BUN (g/mL) | 23 (17–32) | 35 (27–48) | 23 (19–28) | 17 (14–20) | 0.0001 |

| Male | 358 (81.2%) | 117 (79.6%) | 127 (86.4%) | 114 (77.6%) | 0.13 |

| Caucasian | 361 (81.9%) | 122 (83.0%) | 121 (82.3%) | 118 (80.3%) | 0.82 |

| Age at initial ICD implant (years) | 65.3 (56.4–74.2) | 74.1 (67.3–78.5) | 65.7 (58.0–73.6) | 56.3 (47.0–63.4) | 0.0001 |

| First ICD lifetime (years) | 4.7 (3.4–6.1) | 4.2 (3.0–5.2) | 5.0 (3.7–6.4) | 5.3 (3.6–6.5) | 0.0001 |

| Age at first ICD replacement (years) | 70.4 (60.5–79.3) | 78.7 (71.1–83.2) | 70.9 (63.7–79.4) | 60.4 (52.3–69.5) | 0.0001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.4 (24.4–31.3) | 27.0 (23.9–30.6) | 28.1 (24.4–31.4) | 27.7 (24.7–32.3) | 0.08 |

| Primary prevention ICD indication | 285 (64.6%) | 98 (68.5%) | 98 (69.5%) | 89 (61.8%) | 0.32 |

| LVEF at initial ICD implant (%)† | 25 (20–33) | 24 (20–30) | 25 (20–35) | 28 (20–37) | 0.01 |

| LVEF at first ICD replacement (%)‡ | 28 (20–40) | 25 (20–33) | 28 (20–40) | 33 (25–50) | 0.0001 |

| Time from most recent LVEF assessment (months) | 7.8 (1.1–20) | 5.5 (0.7–18.7) | 7.9 (1.6–20.1) | 10.2 (1.3–23.7) | 0.29 |

| History of appropriate ICD therapy§ | 135 (37.8%) | 54 (47.4%) | 36 (31.0%) | 45 (35.4%) | 0.030 |

| History of inappropriate ICD therapy¶ | 70 (19.9%) | 16 (15.2%) | 18 (15.1%) | 36 (28.4%) | 0.012 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 200 (45.3%) | 87 (59.2%) | 64 (43.5%) | 49 (33.3%) | <0.0001 |

| History of hypertension | 321 (72.8%) | 119 (81.0%) | 113 (76.9%) | 89 (60.5%) | <0.0001 |

| History of diabetes | 162 (36.7%) | 65 (44.2%) | 52 (35.4%) | 45 (30.6%) | 0.049 |

| History of coronary artery disease | 322 (73.0%) | 130 (88.4%) | 107 (72.8%) | 85 (57.8%) | <0.0001 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 313 (71.0%) | 123 (83.7%) | 106 (72.1%) | 84 (57.1%) | <0.0001 |

| History of CABG | 184 (41.7%) | 79 (53.7%) | 70 (47.6%) | 35 (23.8%) | <0.0001 |

| On dialysis | 5 (1.1%) | 5 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.006 |

| Initial ICD biventricular | 85 (19.3%) | 35 (23.8%) | 31 (21.1%) | 19 (12.9%) | 0.048 |

| First replacement ICD biventricular | 173 (39.2%) | 87 (59.2%) | 52 (35.4%) | 34 (23.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Type of cardiomyopathy | <0.0001 | ||||

| Infarct related | 285 (64.8%) | 114 (77.6%) | 98 (67.1%) | 73 (49.7%) | – |

| Nonischemic | 102 (23.2%) | 20 (13.6%) | 33 (22.6%) | 49 (33.3%) | – |

| Hypertrophic | 13 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (4.8%) | 6 (4.1%) | – |

| Mixed | 19 (4.3%) | 11 (7.5%) | 3 (2.1%) | 5 (3.4%) | – |

| Other | 21 (4.8%) | 2 (1.4%) | 5 (3.4%) | 14 (9.5%) | – |

| NYHA Functional Class | <0.0001 | ||||

| I | 153 (37.9%) | 21 (15.9%) | 55 (40.7%) | 77 (55.2%) | – |

| II | 123 (30.5%) | 37 (28.0%) | 49 (36.3%) | 37 (27.0%) | – |

| III | 124 (30.7%) | 71 (53.8%) | 30 (22.2%) | 23 (16.8%) | – |

| IV | 4 (1.0%) | 3 (2.3%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | – |

| Medications | |||||

| β-blockers | 393 (89.1%) | 135 (91.8%) | 129 (87.8%) | 129 (87.8%) | 0.43 |

| ACEI/ARBs | 316 (71.7%) | 95 (64.6%) | 116 (78.9%) | 105 (71.4%) | 0.025 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 92 (20.9%) | 30 (20.4%) | 37 (25.2%) | 25 (17.0%) | 0.22 |

| Antiarrhythmic agent | 141 (32.0%) | 70 (47.6%) | 36 (24.5%) | 35 (23.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Indication for generator replacement | |||||

| Battery depletion | 307 (69.6%) | 88 (59.9%) | 116 (78.9%) | 103 (71.1%) | 0.005 |

| Upgrade of ICD | 109 (24.7%) | 57 (38.8%) | 28 (19.1%) | 24 (16.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Generator/lead malfunction | 84 (19.5%) | 21 (14.3%) | 26 (17.7%) | 37 (25.2%) | 0.07 |

Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage of the total. Continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range.

n = 385 patients total.

n = 361 patients total.

n = 357 patients total.

n = 351 patients total.

CKD-EPI = Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NYHA = New York Heart Association; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; ACEI/ARB = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker.

Estimated GFR Tertiles and Total Mortality After First ICD Generator Replacement

The median follow-up was 3.6 years (interquartile range 2.1–5.0 years). Kaplan–Meier survival probabilities at 5 years after first ICD generator replacement were 34.9% for patients in eGFR tertile 1, 61.4% for patients in eGFR tertile 2, and 84.5% for patients in eGFR tertile 3 (log-rank P < 0.0001). Kaplan–Meier survival curves for total mortality stratified by eGFR tertile are shown in Figure 2A. Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard model hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality stratified by eGFR tertile are shown in Table 2. After adjusting for age, gender, LVEF, NYHA class >II, diabetes, infarct cardiomyopathy, presence of a biventricular ICD, and ICD indication, compared to patients with the best renal function in eGFR tertile 3, patients in eGFR tertile 2 had a HR for total mortality of 2.84 (95% CI 1.36–5.94, P = 0.005), and patients in eGFR tertile 1 had a HR for total mortality of 3.84 (95% CI 1.81–8.12, P < 0.0001). When eGFR was considered as a continuous variable, after adjustment for the same risk factors as noted above, eGFR remained independently associated with mortality, with each 10 mL/minute/1.73 m2 decrease in eGFR associated with a HR for mortality of 1.30 (95% CI 1.16–1.45, P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier Curves for survival and freedom from appropriate ICD therapy after ICD generator replacement stratified by CKD-EPI eGFR tertiles. A: Survival; B: Freedom from first appropriate ICD therapy. For a high quality, full color version of this figure, please see Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology’s website: www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jce

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Models for Mortality After First ICD Generator Replacement

| Events/n | HR Tertile 2 versus 3 | P Value | HR Tertile 1 versus 3 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||

| Unadjusted | 142/441 | 3.08 (1.74–5.45) | <0.0001 | 6.58 (3.85–11.23) | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted | 102/328 | 2.84 (1.36–5.94) | 0.005 | 3.84 (1.81–8.12) | <0.0001 |

| Primary prevention only | |||||

| Unadjusted | 90/285 | 2.90 (1.36–6.18) | 0.006 | 7.59 (3.75–15.38) | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted | 69/228 | 2.71 (1.10–6.68) | 0.030 | 4.50 (1.83–11.09) | 0.001 |

| Secondary prevention only | |||||

| Unadjusted | 44/143 | 3.32 (1.29–8.55) | 0.013 | 5.49 (2.23–13.48) | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted | 33/100 | 3.24 (0.84–12.42) | 0.09 | 3.21 (0.76–13.63) | 0.11 |

Model adjusted for eGFR tertile, age, sex, LVEF, NYHA class, diabetes, infarct cardiomyopathy, presence of a biventricular ICD, and ICD indication. HR = hazard ratio.

In subgroup analyses, when only primary prevention patients were analyzed (Table 2), the adjusted HR for mortality associated with each eGFR tertile was similar as when all patients were included (HRadj 2.71, P = 0.030 for tertile 2 compared to tertile 3, and HRadj 4.50, P = 0.001 for tertile 1 compared to tertile 3). In unadjusted Cox proportional hazard models only including patients with a secondary prevention ICD indication, there was a gradient of increased risk with worsening eGFR tertile (HR 3.32, P = 0.013 for tertile 2 compared to tertile 3, and HR 5.49, P < 0.0001 for tertile 1 compared to tertile 3). After multivariable adjustment, however, there was no significant association between eGFR tertile and mortality, likely due to the relatively small number of deaths (44 total) in the secondary prevention subgroup and multiple variables in the adjusted model. A formal test for interaction demonstrated that there was no difference in the HRs for mortality between primary and secondary prevention patients (P = 0.58).

Relation of Estimated GFR to Appropriate ICD Therapy After First ICD Generator Replacement

Kaplan–Meier probabilities of freedom from first appropriate ICD therapy through 5 years after first ICD generator replacement are shown in Figure 2B. Median follow-up was 1.9 years (interquartile range 0.8–3.4 years). Kaplan–Meier probability of freedom from first appropriate ICD therapy at 5 years was 57.0% for patients in eGFR tertile 1, 58.1% for patients in eGFR tertile 2, and 60.2% for patients in eGFR tertile 3, with no statistically significant difference between groups (log-rank P = 0.82). Appropriate ICD therapies were triggered by monomorphic VT 86% of the time, and VF/polymorphic VT 14% of the time.

Unadjusted and adjusted HRs for first appropriate ICD therapy stratified by eGFR tertile at the time of first ICD generator replacement are shown in Table 3. After adjusting for age, LVEF, NYHA class >II, antiarrhythmic therapy, ICD indication, presence of a biventricular ICD, and appropriate ICD therapy prior to ICD generator replacement, eGFR tertile was not significantly associated with appropriate ICD therapy after ICD generator replacement (HRadj 1.12, 95% CI [0.61–2.05], P = 0.72) for eGFR tertile 2 compared to eGFR tertile 3; HRadj 1.06 (95% CI 0.54–2.07, P = 0.88) for eGFR tertile 1 compared to eGFR tertile 3). When eGFR was analyzed as a continuous variable, after adjustment for the same factors as noted above, eGFR remained unassociated with appropriate ICD therapy after ICD generator replacement. Each 10 mL/minute/1.73 m2 decrease in GFR was associated with a nonsignificant difference in appropriate ICD therapies with HR 1.06 (95% CI 0.95–1.19, P = 0.31).

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Cox Proportional Hazards Models for First Appropriate ICD Therapies After First ICD Generator Replacement

| Events/n | HR Tertile 2 versus 3 | P Value | HR Tertile 1 versus 3 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||

| Unadjusted | 103/356 | 1.12 (0.71–1.79) | 0.62 | 1.15 (0.72–1.84) | 0.57 |

| Adjusted | 79/251 | 1.12 (0.61–2.05) | 0.72 | 1.06 (0.54–2.07) | 0.88 |

Model adjusted for eGFR tertile, age, LVEF, NYHA class, antiarrhythmic therapy, ICD indication, presence of a biventricular ICD, and prior appropriate ICD therapy. HR = hazard ratio.

Relation of Estimated GFR to Inappropriate ICD Therapy After First ICD Generator Replacement

Over a 5-year follow-up period, 31 patients (7.0%) experienced an inappropriate ICD shock. Median follow-up was 3.1 years (interquartile range 1.6–5.0 years). Kaplan–Meier probability of freedom from first appropriate ICD therapy at 5 years was 94.5% for patients in eGFR tertile 1, 89.5% for patients in eGFR tertile 2, and 84.1% for patients in eGFR tertile 3, with no statistically significant difference between groups (log-rank P = 0.07). Inappropriate ICD therapies were triggered by atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter 55% of the time, other supraventricular tachycardia 23% of the time, sinus tachycardia 13% of the time, lead malfunction 6% of the time, and electromagnetic noise 3% of the time.

The presence of inappropriate ICD shocks had no statistically significant association with subsequent mortality over 5 years of follow-up; 58.7% of patients without inappropriate ICD shocks, and 71.9% of patients with inappropriate ICD shocks were still alive 5 years after ICD generator replacement (P = 0.12). Due to the relatively small number of inappropriate ICD shocks, further statistical analysis was not performed.

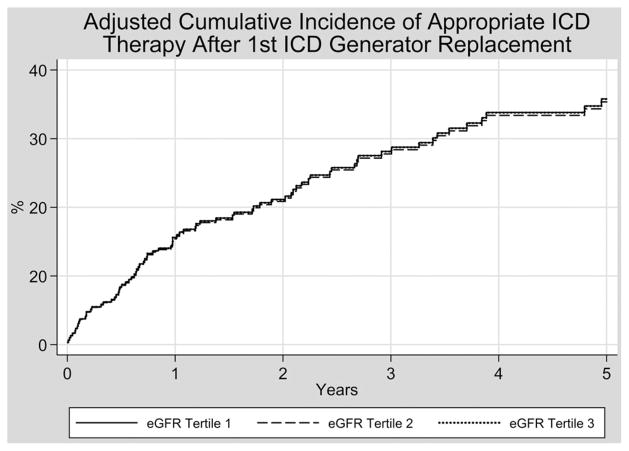

Competing Risk Model for Appropriate ICD Therapies After ICD Generator Replacement

Figure 3 shows the adjusted cumulative incidence of appropriate ICD therapies after first ICD generator replacement as stratified by eGFR tertile, after adjusting for age, LVEF, NYHA class >II, antiarrhythmic therapy, ICD indication, presence of a biventricular ICD, prior appropriate ICD therapy, and the competing risk of death. With this additional adjustment, there remained no statistically significant association between eGFR tertile and appropriate ICD therapies with subhazard ratios of 0.99 (95% CI 0.51–1.90, P = 0.97) for eGFR tertile 2 compared to eGFR tertile 3, and 1.00 (95% CI 0.48–2.08, P = 0.99) for eGFR tertile 1 compared to eGFR tertile 3.

Figure 3.

Adjusted cumulative incidence of appropriate ICD therapy after ICD generator replacement. The parallel nature of the cumulative incidence function curves is a reflection of the way the data are fit to the adjusted model, and the significant overlap in curves is a reflection of the fact that the subhazard ratios for eGFR tertiles 1 and 2 are very close to 1.0 when compared to eGFR tertile 3 (0.99 for eGFR tertile 2 and 1.00 for eGFR tertile 1, respectively).

ICD Programming Parameters

ICD tachyarrhythmia detection parameters for initial and first replacement ICDs are shown in Table 4. In general, detection parameters for both initial and replacement ICDs were well matched between patients who had appropriate ICD therapies during the lifetime of their initial and follow-up device, and those who did not. The only statistically significant difference between patients with and without appropriate ICD therapy during their initial ICD lifetime was in the detection rate of zone 2, although this difference in distribution was of low magnitude given that the median detection rate was 188 bpm for both groups. Among first replacement ICDs, patients who had appropriate ICD therapy during follow-up were more likely to have 3 ICD detection zones compared to those who did not have appropriate ICD therapy (47.2% vs. 22.7%, P < 0.0001). The zone 3 detection rate was also slightly lower among patients who had appropriate ICD therapy compared to those who did not (median 150 bpm vs. 167 bpm, respectively, P = 0.0002). The addition of number of detection zones or zone 3 detection rate to the previous multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for appropriate ICD therapies after first ICD generator replacement had no effect on the magnitude or significance of the HR associated with either tertile of eGFR.

TABLE 4.

ICD Detection Parameters Stratified by Patients with and without Appropriate ICD Therapies

| Initial ICD Detection Parameters | Appropriate ICD Therapy (n = 111) | No Appropriate ICD Therapy (n = 237) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | 0.29 | ||

| Medtronic | 81 (73.0%) | 186 (78.5%) | – |

| St. Jude | 9 (8.1%) | 21 (8.9%) | – |

| Boston Scientific | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (1.7%) | – |

| Guidant | 19 (17.1%) | 22 (9.3%) | – |

| Biotronik | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (1.7%) | – |

| Number of tachycardia zones | 0.42 | ||

| 1 | 29 (30.5%) | 80 (37.9%) | – |

| 2 | 52 (54.7%) | 100 (47.4%) | – |

| 3 | 14 (14.7%) | 31 (14.7%) | – |

| Detection parameters | |||

| Zone 1 cutoff (bpm) | 211 (188–250) | 220 (188–250) | 0.39 |

| Zone 1 NID | 18 (16–18) | 18 (12–18) | 0.20 |

| Zone 1 detection time (seconds) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 0.33 |

| Zone 2 cutoff (bpm) | 188 (170–188) | 188 (182–188) | 0.009 |

| Zone 2 NID | 18 (16–18) | 18 (16–18) | 0.69 |

| Zone 2 detection time (seconds) | 2.5 (2.5–4.0) | 2.5 (2.5–2.5) | 0.23 |

| Zone 3 cutoff (bpm) | 150 (150–162) | 165 (150–171) | 0.09 |

| Zone 3 NID | 16 (16–16) | 16 (16–16) | 0.85 |

| First Replacement ICD Detection Parameters | Appropriate ICD therapy (n = 113) | No Appropriate ICD therapy (n = 242) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | 0.11 | ||

| Medtronic | 88 (77.9%) | 195 (80.6%) | – |

| St. Jude | 8 (7.1%) | 22 (9.1%) | – |

| Boston Scientific | 7 (6.2%) | 16 (6.6%) | – |

| Guidant | 9 (8.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | – |

| Biotronik | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (1.7%) | – |

| Number of tachycardia zones | <0.0001 | ||

| 1 | 7 (6.5%) | 41 (17.5%) | – |

| 2 | 50 (46.3%) | 140 (39.8) | – |

| 3 | 51 (47.2) | 53 (22.7) | – |

| Detection parameters | |||

| Zone 1 cutoff (bpm) | 250 (200–250) | 250 (200–250) | 0.97 |

| Zone 1 NID | 18 (18–18) | 18 (18–18) | 0.97 |

| Zone 1 detection time | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 0.11 |

| Zone 2 cutoff (bpm) | 188 (173–188) | 188 (188–188) | 0.39 |

| Zone 2 NID | 18 (18–18) | 18 (18–18) | 0.74 |

| Zone 2 detection time | 2.5 (2.5–2.5) | 2.5 (2.5–2.5) | 0.37 |

| Zone 3 cutoff (bpm) | 150 (146–162) | 167 (150–171) | 0.0002 |

| Zone 3 NID | 16 (16–16) | 16 (16–16) | 0.70 |

Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage of the total. Continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range. ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NID = number of intervals to detect.

Discussion

In this analysis of 441 patients undergoing first ICD generator replacement, reduced renal function assessed by CKD-EPI eGFR at the time of generator replacement was independently associated with increased mortality in a graded manner, but it had no association with appropriate ICD therapies even after accounting for multiple risk factors and the competing risk of death. When patients were stratified by ICD indication (primary vs. secondary prevention), CKD-EPI eGFR remained associated with mortality among primary prevention patients. Due to a smaller number of secondary prevention patients we cannot exclude a differential association between renal function and mortality among primary and secondary prevention patients. Further study of the interplay between renal function, ICD indication, and mortality is needed.

Patients with advanced chronic renal failure on dialysis are known to be at increased risk for sudden cardiac arrest, but the mechanisms underlying this association are not well defined.28 The association between renal function at the time of initial ICD implantation and subsequent mortality has been previously explored, and most data have suggested an independent association between impaired renal function at the time of initial ICD implantation and subsequent increased mortality.8,13–20 A meta-analysis of the MADIT-I, MADIT-II, and SCD-HeFT randomized control trials also demonstrated that patients with a CKD-EPI eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 derived no net mortality benefit from primary prevention ICD implantation.29

The association between renal function at the time of ICD generator replacement and mortality is less well studied. A retrospective analysis of patients undergoing ICD generator replacement in the National Cardiovascular Disease Registry (NCDR) ICD registry revealed that a 10 point decrease in eGFR (as assessed by the Modified Diet and Renal Disease equation) was associated with an adjusted HR of 1.15 (95% CI 1.14–1.16, P < 0.0001) for total mortality.30 Our results showing an adjusted HR for total mortality of 1.30 (95% CI 1.16–1.44, P < 0.0001) per 10 point decrease in eGFR is consistent with these earlier results, and supports the use of impaired renal function at the time of first ICD generator replacement as a marker for increased mortality risk after the procedure. It should be noted that the NCDR analysis above included patients undergoing any ICD generator replacement, while our analysis only included patients undergoing their first ICD generator replacement.

There are also limited data suggesting that impaired renal function at the time of initial ICD implantation is independently associated with increased rates of appropriate ICD therapies. In a study of 230 patients undergoing initial implantation of an ICD who were stratified into tertiles by SCr, there was a graded increase in appropriate ICD therapies with worsening renal function, with Kaplan–Meier estimates of freedom from first appropriate ICD therapy at 1 year of 91.2%, 79.2%, and 73.7% (P = 0.02) for the lowest to highest SCr tertiles respectively.23 However, the association between renal function at the time of ICD generator replacement and subsequent appropriate ICD therapies is unknown.

Our results suggest that despite the association between impaired renal function at the time of initial ICD implantation and increased rates of subsequent appropriate ICD therapies, there is no association between renal function at the time of ICD generator replacement and appropriate ICD therapies after the procedure. Given the significant influence of renal function on mortality after ICD generator replacement, it could be posited that this lack of difference is the result of increased mortality among patients with renal impairment which limits their “time at risk” for ventricular arrhythmias. However, even after accounting for death in a competing risk model, the rate of appropriate ICD therapies between all 3 eGFR tertiles remained similar. This is not surprising, as we know of no obvious direct link between metabolic abnormalities associated with renal failure and mechanisms underlying sustained VT or VF.

Patients with the most impaired renal function (eGFR tertile 1) had slightly lower LVEFs, more cardiac comorbidities, and more frequent appropriate ICD therapies prior to ICD generator replacement compared to patients with better renal function in eGFR tertiles 2 and 3. Given that patients in GFR tertile 1 had more risk factors for ventricular arrhythmias, the lack of an association between eGFR and appropriate ICD therapies after ICD generator replacement could also potentially be partially explained by a higher rate of antiarrhythmic medication use among patients in eGFR tertile 1. We adjusted for arrhythmia risk factors (including LVEF, prior appropriate ICD therapy, and antiarrhythmic use) in the multivariable Cox and competing risk models to minimize the effect of these potential confounders on the association between renal function and appropriate ICD therapies.

The explanation for the discrepancy in association of impaired renal function with appropriate ICD therapies after initial ICD implantation and after ICD generator replacement is unclear, but likely reflects variations in patient characteristics between the time of initial ICD implantation and first ICD generator replacement; patients who survive long enough to undergo ICD generator replacement are older and have new and progressive comorbidities compared to when their ICDs were initially implanted, and temporal variations in patient characteristics may explain this observation. Some subgroups of patients also are likely to die before they require generator replacement.

Our results support a reduction in the benefit of an ICD among patients undergoing ICD generator replacement with the most severe renal dysfunction, as their risk of all-cause mortality was increased significantly without a concomitant increase in the risk of appropriately treated ventricular arrhythmias. Overall, this suggests that physicians assessing the risks and benefits of ICD generator replacement should consider patients with significantly impaired eGFR to have a high rate of mortality and a potentially reduced benefit to ICD generator replacement compared to patients with normal renal function. Further prospective study is warranted to validate these results.

Limitations

This study was retrospective and performed at a single academic medical center. Therefore, our results may not be completely generalizable to other patient populations, although the similarity of our mortality data to results obtained from the NCDR would tend to refute this concern. Because the study was retrospective and included ICD replacements over an 11-year period, ICD tachyarrhythmia detection parameters were not standardized and this could affect the occurrence of appropriate ICD therapies if devices were programmed to treat ventricular arrhythmias aggressively after very short detection times. We demonstrated, however, that there was minimal difference in programming among patients who did and did not have appropriate ICD therapy after generator replacement making this type of bias less likely. Appropriate ICD therapy is also only a surrogate marker for sudden cardiac death; the delivery of ICD therapy for VT or VF should not imply that the patient would have died had he/she not had an ICD, and our results do not directly correlate with the true risk of sudden/arrhythmic death in this population.

Because ICD generator replacement was performed at a referral center, some patients who underwent generator replacement had subsequent ICD follow-up at outside institutions, and information on appropriate ICD therapies after ICD generator replacement was unavailable. There was, however, no difference in SCr between patients who had follow-up and those who did not (median SCr 1.2 mg/dL vs. 1.2 mg/dL, P = 0.31).

Creatinine was not routinely measured on all patients at the time of ICD generator replacement, and we therefore cannot exclude selection bias in our results. Last, creatinine is a dynamic variable, and we are unable to determine if there were significant variations in renal function during the follow-up period after ICD generator replacement.

Conclusions

Impaired renal function at the time of first ICD generator replacement is strongly associated with mortality, and almost two-thirds of patients with the most impaired eGFR (<47 mL/min/1.73 m2) died within 5 years of their first ICD generator replacement. However, impaired renal function was not significantly associated with appropriate ICD therapies after ICD generator replacement with approximately 40% of patients experiencing an appropriate ICD therapy by 5 years regardless of eGFR. The poorer survival of ICD patients with impaired renal function does not appear to be influenced by ventricular arrhythmia, and there is no clear proarrhythmic effect of increasingly severe renal dysfunction, even after accounting for the competing risk of death in this population. Risk stratification tools which have been designed for and validated in patients at the time of initial ICD implantation may not apply to patients at the time of ICD generator replacement, and clinicians should consider renal function when discussing the risks and benefits of ICD generator replacement.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst. The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NCRR and NCATS, NIH Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

The authors express their appreciation to Mark E. Josephson, M.D., for his review and thoughtful suggestions.

Footnotes

A. Buxton reports research grants from Medtronic, Inc. and Biosense Webster. Other authors: No disclosures.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1882–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators: A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1576–1583. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial III: Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial I: Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiMarco JP. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1836–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Hafley GE, Pires LA, Fisher JD, Gold MR, Josephson ME, Lehmann MH, Prystowsky EN, Investigators M. Limitations of ejection fraction for prediction of sudden death risk in patients with coronary artery disease: Lessons from the MUSTT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1150–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, Zareba W, McNitt S, Andrews ML. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer DB, Kennedy KF, Noseworthy PA, Buxton AE, Josephson ME, Normand SL, Spertus JA, Zimetbaum PJ, Reynolds MR, Mitchell SL. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving new and replacement implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Results from the NCDR. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:488–497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krahn AD, Lee DS, Birnie D, Healey JS, Crystal E, Dorian P, Simpson CS, Khaykin Y, Cameron D, Janmohamed A, Yee R, Austin PC, Chen Z, Hardy J, Tu JV. Predictors of short-term complications after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator replacement: Results from the Ontario ICD Database. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:136–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer DB, Buxton AE, Zimetbaum PJ. Time for a change–A new approach to ICD replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:291–293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tompkins C, McLean R, Cheng A, Brinker JA, Marine JE, Nazarian S, Spragg DD, Sinha S, Halperin H, Tomaselli GF, Berger RD, Calkins H, Henrikson CA. End-stage renal disease predicts complications in pacemaker and ICD implants. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy R, DellaValle A, Atav AS, ur Rehman A, Sklar AH, Stamato NJ. The relationship between glomerular filtration rate and survival in patients treated with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:265–269. doi: 10.1002/clc.20209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreuz J, Horlbeck F, Schrickel J, Linhart M, Fimmers R, Mellert F, Nickenig G, Schwab JO. Kidney dysfunction and deterioration of ejection fraction pose independent risk factors for mortality in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients for primary prevention. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35:575–579. doi: 10.1002/clc.22018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hager CS, Jain S, Blackwell J, Culp B, Song J, Chiles CD. Effect of renal function on survival after implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1297–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckart RE, Gula LJ, Reynolds MR, Shry EA, Maisel WH. Mortality following defibrillator implantation in patients with renal insufficiency. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:940–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong D, Tan BY, Ho KL, Liew R, Teo WS, Ching CK. Clinical markers of organ dysfunction associated with increased 1-year mortality post-implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation. Europace. 2013;15:508–514. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turakhia MP, Varosy PD, Lee K, Tseng ZH, Lee R, Badhwar N, Scheinman M, Lee BK, Olgin JE. Impact of renal function on survival in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams ES, Shah SH, Piccini JP, Sun AY, Koontz JI, Al-Khatib SM, Hranitzky PM. Predictors of mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease and an implantable defibrillator: An EPGEN substudy. Europace. 2011;13:1717–1722. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer DB, Friedman PA, Kallinen LM, Morrison TB, Crusan DJ, Hodge DO, Reynolds MR, Hauser RG. Development and validation of a risk score to predict early mortality in recipients of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi A, Shiga T, Shoda M, Manaka T, Ejima K, Hagiwara N. Impact of renal dysfunction on appropriate therapy in implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2009;11:1476–1482. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alla VM, Anand K, Hundal M, Chen A, Karnam S, Hee T, Hunter C, Mooss AN, Esterbrooks D, Mohiuddin SM. Impact of moderate to severe renal impairment on mortality and appropriate shocks in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Cardiol Res Pract. 2010;2010:150285. doi: 10.4061/2010/150285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hreybe H, Ezzeddine R, Bedi M, Barrington W, Bazaz R, Ganz LI, Jain S, Ngwu O, London B, Saba S. Renal insufficiency predicts the time to first appropriate defibrillator shock. Am Heart J. 2006;151:852–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreuz J, Balta O, Linhart M, Fimmers R, Lickfett L, Mellert F, Nickenig G, Schwab JO. An impaired renal function and advanced heart failure represent independent predictors of the incidence of malignant ventricular arrhythmias in patients with an implantable cardioverter/defibrillator for primary prevention. Europace. 2010;12:1439–1445. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuz J, Horlbeck F, Hoyer F, Mellert F, Fimmers R, Lickfett L, Nickenig G, Schwab JO. An impaired renal function: A predictor of ventricular arrhythmias and mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:894–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng AC, Bertini M, Borleffs CJ, Delgado V, Boersma E, Piers SR, Thijssen J, Nucifora G, Shanks M, Ewe SH, Biffi M, van de Veire NR, Leung DY, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ. Predictors of death and occurrence of appropriate implantable defibrillator therapies in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1566–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herzog CA, Mangrum JM, Passman R. Sudden cardiac death and dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2008;21:300–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2008.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pun PH, Al-Khatib SM, Han JY, Edwards R, Bardy GH, Bigger JT, Buxton AE, Moss AJ, Lee KL, Steinman R, Dorian P, Hallstrom A, Cappato R, Kadish AH, Kudenchuk PJ, Mark DB, Hess PL, Inoue LY, Sanders GD. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in CKD: A meta-analysis of patient-level data from 3 randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:32–39. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer DB, Kennedy KF, Spertus JA, Normand SL, Noseworthy PA, Buxton AE, Josephson ME, Zimetbaum PJ, Mitchell SL, Reynolds MR. Mortality risk following replacement implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation at end of battery life: Results from the NCDR. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]