We describe improvements in exposure to antiretroviral therapy and virologic status, including decreased rates of human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance, among 819 illicit drug users in a Canadian setting during a community-wide treatment-as-prevention campaign.

Keywords: plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load, HIV drug resistance, people who use illicit drugs, treatment-as-prevention

Abstract

Background. Although treatment-as prevention (TasP) is a new cornerstone of global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–AIDS strategies, its effect among HIV-positive people who use illicit drugs (PWUD) has yet to be evaluated. We sought to describe longitudinal trends in exposure to antiretroviral therapy (ART), plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) and HIV drug resistance during a community-wide TasP intervention.

Methods. We used data from the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services study, a prospective cohort of HIV-positive PWUD linked to HIV clinical monitoring records. We estimated longitudinal changes in the proportion of individuals with VL <50 copies/mL and rates of HIV drug resistance using generalized estimating equations (GEE) and extended Cox models.

Results. Between 1 January 2006 and 30 June 2014, 819 individuals were recruited and contributed 1 or more VL observation. During that time, the proportion of individuals with nondetectable VL increased from 28% to 63% (P < .001). In a multivariable GEE model, later year of observation was independently and positively associated with greater likelihood of nondetectable VL (adjusted odds ratio = 1.20 per year; P < .001). Although the proportion of individuals on ART increased, the incidence of HIV drug resistance declined (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.78 per year; P = .011).

Conclusions. We observed significant improvements in several measures of exposure to ART and virologic status, including declines in HIV drug resistance, in this large long-running community-recruited cohort of HIV-seropositive illicit drug users during a community-wide ART expansion intervention. Our findings support continued efforts to scale up ART coverage among HIV-positive PWUD.

Despite substantial scientific advances in methods to prevent and treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, members of some high-risk groups continue to experience elevated rates of infection and HIV–AIDS-related morbidity and mortality [1–3]. Outside of sub-Saharan Africa, at least 1 in 4 new infections occurs among people who use illicit drugs (PWUD) [4]. Even in many high-resource settings, PWUD living with HIV–AIDS are less likely to access antiretroviral therapy (ART) and experience optimal HIV treatment outcomes [3].

In the wake of recent studies showing how ART can reduce HIV transmission at the individual [5] and population [6, 7] levels, HIV treatment-as-prevention (TasP) is now recognized as a cornerstone of efforts to control the HIV–AIDS pandemic globally [8–10]. Interventions to expand coverage of ART and suppress individual- and community-level plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) to, in part, curb HIV incidence are ongoing worldwide [9]. There is a need for evidence to optimize seek, test, treat, and retain campaigns, including improvements in HIV testing, retention in care, clinical monitoring, and management of HIV–AIDS-associated comorbidities [11, 12]. A key scientific issue is the effect of increasing ART coverage among hard-to-reach populations on virologic outcomes. Specifically, there are concerns that expanding ART coverage, especially among members of groups that face well-known barriers to ART adherence, will lead to increases in virologic failure and the consequent increase in the incidence of secondary HIV drug resistance. This, in turn, may lead to an increase in the incidence of primary (or transmitted) HIV drug resistance, possibly compromising the effectiveness of current ART regimens and the effectiveness of the overall TasP strategy [13, 14].

Like many urban settings in the Americas, Europe, and Asia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, has a widespread HIV epidemic among PWUD [15, 16]. In response, the local government launched a number of initiatives including a seek, test, and treat initiative aimed at expanding ART use among PWUD and members of other traditionally hard-to-treat groups. This multifaceted community-wide intervention included efforts to increase testing rates, such as community-based testing events and opt-out testing policies; changes to clinical guidelines in order to increase initiation of ART; and provision of ART adherence supports, for example, directly observed therapy-based programs. In this study, we describe long-term patterns of exposure to ART and virologic outcomes, including the prevalence of controlled VL and rates of HIV drug resistance, over calendar time among a community-recruited longitudinal cohort of HIV-positive PWUD.

METHODS

For these analyses, we examined data from the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS), an ongoing observational prospective cohort of HIV-seropositive individuals who use illicit drugs and live in Vancouver [17]. Study recruitment, which began in May 1996 and focused on the city's downtown eastside neighborhood, an area with a well-described epidemic of illicit drug use–associated HIV infection, used community-based methods such as outreach to low-barrier services for PWUD. In 2005, to replenish the cohort, a new wave of recruitment, using similar community-based methods, was initiated in the same setting, which includes a long-standing open drug market alongside high levels of homelessness and poverty. Individuals were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were HIV positive as demonstrated through serology, aged ≥18 years, had used illicit drugs other than cannabis in the previous month, and provided written informed consent. The University of British Columbia/Providence Healthcare Research Ethics Board approved the ACCESS study.

At recruitment and every 6 months thereafter, individuals complete an interviewer-administered survey and undergo an examination by a study nurse. At baseline, participants provide their personal health number, a unique and persistent identifier issued for billing and tracking purposes to all residents of British Columbia by the government-run universal no-cost medical system. Using this identifier, study staff established a confidential linkage with the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC-CfE) Drug Treatment Programme (DTP). Through the DTP, the BC-CfE provides HIV care including all ART and clinical monitoring to all individuals living with HIV–AIDS in the province of British Columbia. Through this linkage, a complete retrospective and clinical profile, including data on all CD4+ cell counts, VL observations, and viral genotyping tests conducted under the aegis of the study or as a part of ongoing clinical care, is available for each participant. The linkage also provides records on all dispensations of ART, including dates, quantity, and regimen dispensed.

In this study, we included all individuals recruited between 1 January 2006 and 30 June 2014 who completed 1 or more VL tests. Individuals were included in these analyses from the date of their first VL observation or 1 January 2006, whichever was later, until 30 June 2014 or death, as ascertained through a confidential linkage to the British Columbia government's Vital Statistics Agency.

The primary outcome of interest was plasma HIV-1 RNA VL (copies per milliliter, log10 transformed). To incorporate all observations over time, each individual's VL measurements were aggregated into 6-month periods (ie, 1 January to 30 June; 1 July to 31 December) in each calendar year. During each period, the VL was defined as the mean of all observations in each period or, if there were none in any period, the most recent observation. The Roche Amplicor Monitor assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, California) was used to determine VL from participant blood samples. For all study periods, the lower bound of detection for the VL assay used was 50 c/mL; individuals with an undetectable VL were assigned a value of 49 c/mL. In analyses of viremic control, we defined an individual's period as being controlled if all observations in the period were <50 c/mL. If there were no VL observations in the period, we defined the period as being viremically uncontrolled, unless pharmacy records indicated the individual was successfully dispensed ART for more than 95% of the days in the period.

For analyses of ART resistance, we followed laboratory and analytic protocols previously described [18]. Genotyping was systematically performed on all samples gathered from individuals previously exposed to 1 or more days of ART with VL above 250 c/mL. Viral protease and reverse transcriptase genes were amplified through nested reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [19], and an Applied Biosystems automated sequencer was used to sequence the products in both the 5′ and 3′ directions to generate a consensus sequence. Samples were determined to be resistant if they contained 1 or more major resistance mutations for any of the 3 categories of antiretroviral agents (protease inhibitors, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, or nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors) using the International AIDS Society–USA guidelines [20].

Our primary explanatory variable of interest was year of observation. We also considered other explanatory variables gathered during the baseline interview, including age, sex, educational attainment, self-reported ethnicity, and whether illicit drugs via injection had ever been used. From the confidential linkage, we gathered information on the following time-updated variables: CD4+ cell count and whether the participant had ever been exposed to ART. As with VL, we defined CD4+ cell count as the mean of all observations conducted during the period or, if none, the most recent observation. For each individual, we also identified the date they were added to the HIV treatment registry (ie, date of first VL observation, viral resistance genotyping, or ART dispensation). Among ART-exposed participants, we collected the following variables in all periods following the date of ART initiation (inclusive): number of days dispensed ART, ever exposed to a protease inhibitor, time since ART initiation, and CD4+ cell count at ART initiation. Adherence to ART was defined as the ratio of days of ART dispensed during the period to days since ART initiation in the period, dichotomized at 95%. We have previously demonstrated that this validated pharmacy-refill measure is strongly associated with VL suppression [21] and survival [22].

As a first step, we compared all individuals for their first 6-month period by VL (<50 c/mL vs ≥50 c/mL) and several explanatory variables. Next, we visualized the distribution of VL (log10 transformed; median, first, and third quartile; and outliers), the proportion of individuals with VL <50 c/mL, and the proportion in mutually exclusive ART exposure categories. To test for trends over time, we used the Mann–Kendall test of medians and the Cochran-Armitage test of proportions. As a third step, we built generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression models to model changes in controlled viremia over time. We used the GEE approach to account for multiple observations per individual as well as to model the marginal change in proportions. Our primary explanatory variable of interest was year of observation. To best estimate changes in VL over time, we also included secondary explanatory variables that we hypothesized might be associated with both year of observation and the likelihood of controlled VL but not on the causal pathway, including age, sex, white ethnicity, education, injection drug use, and time since first database record. Next, we fit a multivariable model using an a priori manual stepwise backward model building protocol suggested by Maldonado and Greenland [23] and used previously [24].

To analyze trends in drug resistance over time, we first calculated the incidence of positive tests for genotypic resistance per 100 person-years of observation per annum. Next, we built survival models of time to incident resistance among resistance-free individuals. As in a previous analysis [18], we modeled the time to the generation of resistance in any category. Individuals were then censored in that category; using a repeated-measures framework, time to generation of resistance in remaining categories was analyzed. Our primary explanatory variable of interest was year of observation. We also included secondary explanatory variables we hypothesized were associated with year of observation and resistance but not on the causal pathway, including age, sex, white ethnicity, education, injection drug use, and time since ART initiation. We fit a multivariable Cox extended model using the protocol described above.

RESULTS

Between 1 January 2006 and 30 June 2014, 844 HIV-seropositive illicit drug users were recruited. Of these, 819 (97%) had at least 1 VL observation during the study period and were included in these analyses. These included 276 (33.7%) women and 454 (55.4%) individuals self-reporting white ancestry. The mean age of all participants was 40.9 years (interquartile range [IQR], 34.8–46.3). Those included did not differ from those excluded by age, gender, ancestry, or CD4+ cell count at baseline (all P > .05). In total, individuals included in these analyses contributed 25 746 VL observations, or a median of 2 (IQR, 1–3) per 6-month observation period, and 6095 person-years of observation, or a median of 8.5 (7.0–8.5) years per individual. Among these individuals, 553 were ART exposed and had at least 1 period of VL > 250 c/mL and contributed 3272 resistance tests, or a median of 3 (1–6) per individual.

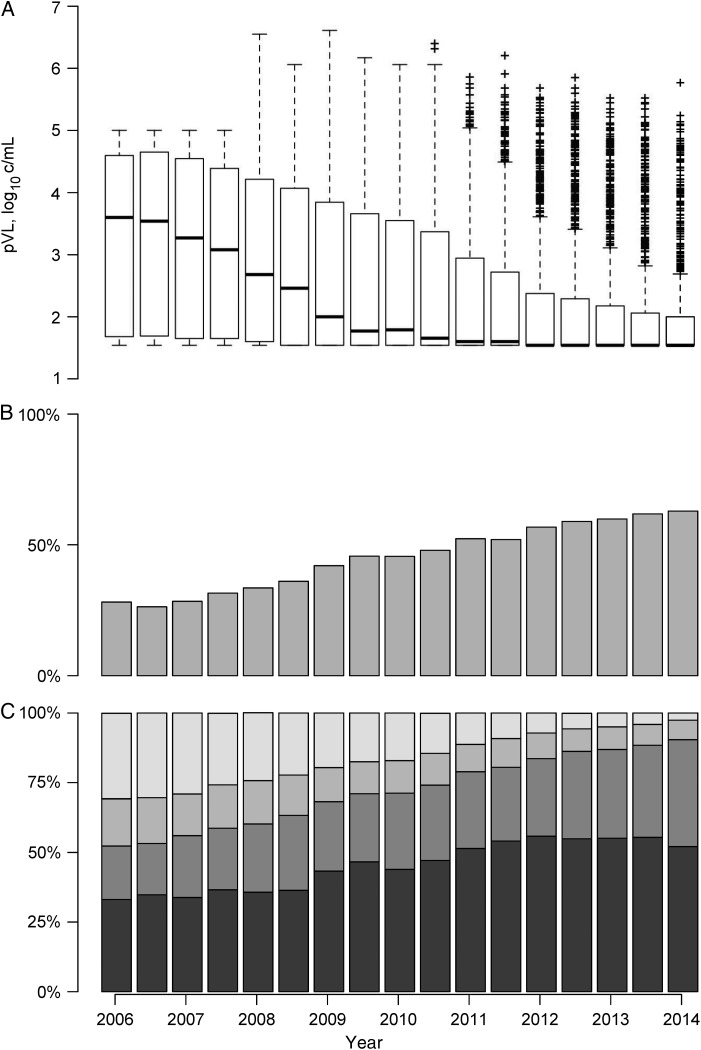

The characteristics of all 819 individuals at their baseline study period, stratified by nondetectable VL, are presented in Table 1. Three box plots depicting virologic status and engagement in HIV care at each observation period are shown in Figure 1. Of note, in the top panel, mean VL declined among all individuals from 3.6 log10 c/mL (IQR, 1.7–4.6) during the earliest period to 1.5 log10 c/mL (1.5–2.0) in the latest period. In the middle panel, the proportion of individuals with undetectable VL increased from 28.1% to 62.9% (P < .001). The bottom panel, which depicts the distribution of individuals in mutually exclusive ART exposure categories, shows a decrease in the proportion of individuals who were ART naive (30.7% to 2.6%; P < .001) and an increase in the proportion of individuals with ≥95% adherence (47.8% to 53.5%; P < .001)

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 819 Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Positive Illicit Drug Users, AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services Study

| Characteristic | Plasma Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA (copies/mL) |

Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥50 629 (70.6) n (%) |

<50 190 (29.4) n (%) |

||||

| All participants (819, 100.0%) | |||||

| Age, y (per year) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 40 (34–45) | 44 (30–49) | 1.07 | 1.05–1.10 | <.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 404 (64.2) | 139 (73.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 225 (35.8) | 51 (26.8) | 0.66 | .46–.94 | .022 |

| White ethnicity | |||||

| No | 284 (45.2) | 81 (42.6) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 345 (54.8) | 109 (57.3) | 1.11 | .80–1.54 | .540 |

| Education | |||||

| <High school diploma | 338 (53.7) | 107 (56.3) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥High school diploma | 291 (46.3) | 83 (43.7) | 0.90 | .65–1.25 | .531 |

| Injection drug use | |||||

| Never | 65 (10.3) | 21 (11.1) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 564 (89.7) | 169 (88.9) | 0.93 | .55–1.56 | .777 |

| CD4 cell count (per 100 c/mL) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.8–4.6) | 3.8 (2.5–5.4) | 1.15 | 1.07–1.23 | <.001 |

| ART | |||||

| Never | 323 (51.4) | 7 (3.7) | 1.00 | ||

| Ever | 306 (48.6) | 183 (96.3) | 27.60 | 12.77–59.65 | <.001 |

| Time since first record (per year) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (0.0–8.1) | 7.9 (4.2–9.2) | 1.21 | 1.15–1.27 | <.001 |

| All baseline ART-exposed participants (489, 59.7%) | |||||

| ART dispensed last 180 d (days) | |||||

| 0 | 109 (35.6) | 2 (1.1) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥1 | 197 (64.7) | 181 (98.9) | 50.07 | 12.19–205.72 | <.001 |

| ART adherence | |||||

| <95% | 216 (70.6) | 28 (15.3) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥95% | 90 (29.4) | 155 (84.7) | 13.29 | 8.29–21.29 | <.001 |

| Ever exposed to protease inhibitor | |||||

| No | 75 (24.5) | 51 (27.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 231 (75.5) | 132 (72.1) | 0.84 | .55–1.27 | .411 |

| Time since ART initiation (per year) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 6.5 (2.1–8.9) | 6.7 (2.8–9.4) | 1.03 | .98–1.09 | .195 |

| CD4 cell count at ART initiation (cells/µL) | |||||

| >500 | 42 (13.7) | 16 (8.7) | 1.00 | ||

| ≤500 and >350 | 60 (19.6) | 24 (13.1) | 1.05 | .50–2.21 | .900 |

| ≤350 and >200 | 84 (27.5) | 56 (30.6) | 1.75 | .90–3.41 | .098 |

| ≤200 | 120 (39.2) | 87 (47.5) | 1.90 | 1.00–3.60 | .046 |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1.

A, Box plot of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA viral load (VL; log10 transformed) by study period. B, Proportion of all individuals with VL <50 copies/mL plasma by study period. C, Proportion of all individuals in period in discrete antiretroviral therapy (ART) exposure categories (Lightest grey = ART naive; Second-lightest grey = ART exposed and 0 days in period; Second-darkest grey = ART exposed and 1 or more days in period and <95% adherence; and Darkest grey = ART exposed and ≥95% adherence). Abbreviation: pVL, plasma viral load.

The bivariable and multivariable GEE analyses of nondetectable VLs are displayed in Table 2. In the multivariable model adjusted for age and time since first database record, later year of observation was independently associated with greater prevalence of undetectable VL (adjusted odds ratio = 1.15 per year; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11–1.18; P < .001).

Table 2.

Longitudinal Bivariable and Multivariable Generalized Estimating Equation Analyses of Factors Associated With Plasma Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) RNA Viral Load <50 c/mL Among 819 HIV-Positive Illicit Drug Users, 2006–2014

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of observation (per year) | 1.23 | 1.20–1.26 | <.001 | 1.15 | 1.11–1.18 | <.001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.06 | 1.05–1.07 | <.001 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.05 | <.001 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 0.80 | .66–.96 | .017 | |||

| White (yes vs no) | 1.02 | .85–1.21 | .847 | |||

| Education (≥high school diploma vs <high school diploma) | 0.95 | .80–1.13 | .562 | |||

| Injection drug use (ever vs never) | 0.93 | .70–1.23 | .598 | |||

| Time since registration (per year) | 1.12 | 1.10–1.14 | <.001 | 1.07 | 1.05–1.09 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

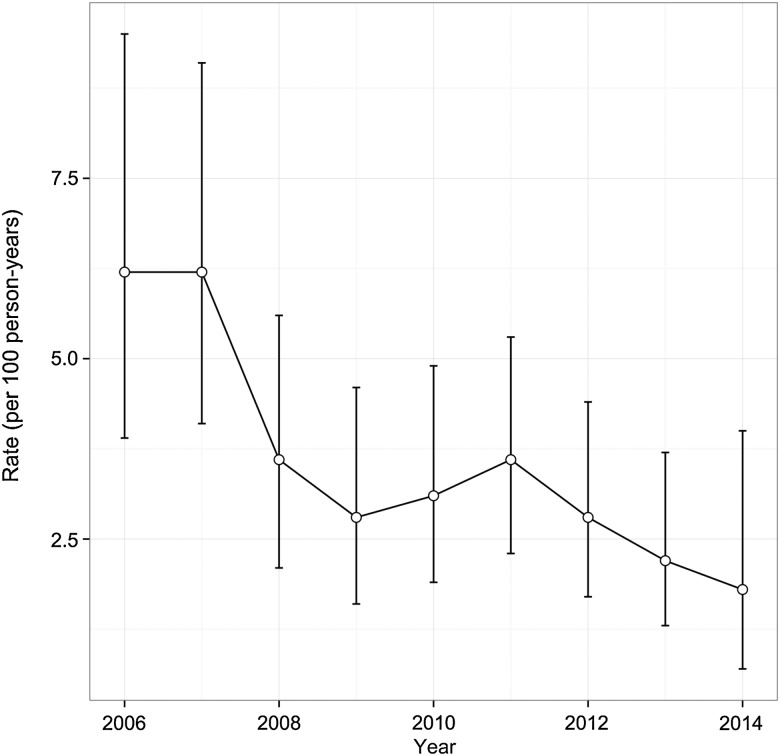

Figure 2 depicts the crude incidence of drug resistance detected per annum. As shown, the incidence per 100 person-years declined from 6.2 (95% CI, 3.9–9.5) to 1.8 (0.7–4.0) per annum. The bivariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with time to resistance are presented in Table 3. In the multivariable model adjusted for age and education, later year of observation remained inversely associated with time to resistance (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.78; 95% CI, .65–.94; P = .011).

Figure 2.

Incidence rates of drug resistance detected per annum per 100 person-years of antiretroviral therapy (ART; circle) with 95% confidence intervals among 773 ART-exposed human immunodeficiency virus–positive people who use illicit drugs, 2006–2014.

Table 3.

Bivariable and Multivariable Analyses of Factors Associated With Time to Detection of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Antiretroviral Resistance Among 773 HIV-Positive and Antiretroviral Therapy–Exposed Illicit Drug Users, 2006–2014

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (per year) | 0.81 | .67–.97 | .024 | 0.78 | .65–.94 | .011 |

| Age (per year) | 0.99 | .97–1.00 | .083 | 0.98 | .96–.99 | .025 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 1.21 | .91–1.61 | .184 | |||

| White (yes vs no) | 0.87 | .66–1.15 | .330 | |||

| Injection drug use (ever vs never) | 1.04 | .63–1.71 | .885 | |||

| Education (≥high school diploma vs < high school diploma) | 1.21 | .92–1.60 | .171 | 1.27 | .96–1.68 | .089 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

These analyses of data from a community-recruited cohort of HIV-positive illicit drug users describe substantial and significant improvements in exposure to ART and virologic status over calendar time coincident with a local TasP initiative. Between 2006 and mid-2014, median VL declined while the proportion of all individuals with controlled VL more than doubled to 62.9%. Meanwhile, an increase in the proportion of individuals exposed to HIV treatment was accompanied by a significant decrease in rates of drug resistance.

Previous analyses of HIV treatment outcomes among PWUD have found lower likelihoods of virologic suppression [21, 25]. In the current study, improvements in VL over time were apparent both in the descriptive serial cross-sectional analyses as well as the multivariable longitudinal model. Our findings are consistent with those from recent analyses of changes in virologic status over calendar time in several clinic- [26–29] and population-based [6, 18] studies. For example, in clinical studies in Baltimore, Maryland [28, 30], and Washington, D.C. [27], both with substantial proportions of people reporting substance use and other risk factors for suboptimal HIV treatment outcomes, the proportion of individuals exposed to combination ART and achieving nondetectable VL both increased. Our findings build on these observations, as participants in the present study were recruited from community settings rather than clinical environments, and, in this cohort, previous reports have described high levels of illicit drug use [31], incarceration [24], homelessness [32], and other barriers to effective HIV–AIDS care [33] during an ART scale-up initiative. In addition, we are unaware of any other studies of PWUD that have reported on rates of HIV drug resistance resulting from systematic monitoring among all ART-exposed individuals.

Mathematical simulations of the possible population-level impacts of increased ART coverage that have included consideration of viral resistance all predict substantial increases in resistance [13, 14, 34]. For example, Sood and colleagues projected that a test-and-treat initiative among men who have sex with men in Los Angeles County, California, would result in a 33.8% decrease in the number of new infections and a near doubling of multidrug resistance (9.1% vs 4.8%) [14]. Although we are unaware of any model that attempts to simulate a test-and-treat initiative among PWUD, our findings do not support concerns that increased coverage of ART among PWUD will lead to increased viral resistance. In our study, we observed a sharp increase in ART coverage among study participants accompanied by a significant decrease in rates of viral resistance. Declining rates of resistance are consistent with an earlier report among all individuals exposed to HIV treatment in this setting [18]. To date, empiric data have not borne out model-based fears of increased levels of resistance as a result of increased ART coverage.

As an observational study with nonrandom sample recruitment, we cannot conclude that the observed trends in virologic status over time are necessarily representative of the larger population of HIV-positive PWUD in Vancouver or elsewhere. However, our analyses benefit from use of data from a large cohort of HIV-seropositive PWUD recruited from community settings and followed over the long term. Also, our outcomes of interest were observed from an administrative source of comprehensive clinical monitoring data in a setting where all HIV treatment and care are delivered free of charge. Finally, it should be noted that while these analyses indicated significant improvements in several measures of HIV treatment over time, we did not evaluate potentially causal factors related to these changes, such as exposure to specific interventions related to the community-wide TasP campaign. To help optimize HIV treatment outcomes among PWUD in other settings, future analyses could assess the contribution to these changes of various factors, including improvements in antiretroviral potency, tolerability, and durability; new strategies to engage and retain PWUD in clinical care; and changes in the social and structural contexts of treatment delivery, such as homelessness and incarceration. Future studies should also seek to determine the effect of the current TasP campaign as well as other public health–based responses on HIV incidence among PWUD in this setting.

These results have immediate relevance to settings with suboptimal coverage of ART among HIV-positive PWUD. Although TasP is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of the global effort to control the HIV–AIDS pandemic and has been adopted in several jurisdictions with substantial epidemics among PWUD, there are very limited data on efforts to scale up ART among members of these groups [35]. Unfortunately, surveys of HIV treatment patterns among PWUD suggest large proportions remain unexposed to ART with detectable VL [3]. For example, a recent study among 790 members of a community-recruited cohort of HIV-positive PWUD in Baltimore reported that more than one-third remained ART naive during the 7-year study period and only 9% exhibited sustained viral suppression [36]. A key concern remains the criminalization of PWUD, which has fostered persistent barriers to optimal HIV treatment outcomes in many settings [33, 36, 37].

To conclude, we used data from a long-running observational cohort of HIV-positive PWUD to describe changes in virologic status over calendar time during a community-wide TasP initiative. We observed substantial and significant improvements, including a doubling of the proportion of individuals with a nondetectable plasma VL, coincident with a large increase in ART coverage. In contrast to recent concerns [13, 14], we observed a significant decrease in the rate of HIV drug resistance coinciding with ART scale-up in this population. Given high levels of preventable HIV–AIDS-related morbidity and mortality observed among PWUD worldwide, our results support redoubling efforts to scale-up ART among HIV-seropositive PWUD.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the study participants for their contributions to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We specifically thank Kristie Starr, Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Carmen Rock, Brandon Marshall, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, Benita Yip, and Guillaume Colley for their research and administrative assistance.

Authorship. E. W. and T. K. designed the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services study and secured funding and data. B. H. and P. R. H. contributed data. M.-J. M. conceived of the current study, conducted all statistical analyses, and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript, contributed revisions, and approved the final version to be submitted.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant number R01-DA021525). M.-J. M. is supported, in part, by the NIH (grant number R01-DA021525). This work was supported in part by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner-City Medicine awarded to E. W. P. R. H. is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research/GlaxoSmithKline Research Chair in Clinical Virology. J. M. is supported by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and through an Avant-Garde Award (award number 1DP1DA026182) from NIDA at the NIH.

Potential conflicts of interest. J. M. has received financial support from the International AIDS Society, United Nations AIDS Program, World Health Organization, National Institutes of Health Research–Office of AIDS Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, United Nations Children's Fund, the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, Providence Health Care, and Vancouver Coastal Health Authority. He has received grants from Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. P. R. H. has received grants from, served as an ad hoc advisor to, or spoke at various events sponsored by Pfizer, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Abbott, Merck, Virco, and Monogram. He has consulted or received grant funding from a variety of pharmaceutical diagnostic companies. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet 2008; 372:1733–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet 2010; 376:268–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet 2010; 376:355–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet 2010; 376:532–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science 2013; 339:966–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinton HR. Remarks on creating an “AIDS-free generation.” Bethesda, Maryland, USA: Government of the United States, 2011. Available at: http://www.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2011/11/176810.htm. Accessed 16 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS. 90–90–90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Programmatic update: Antiretroviral treatment as prevention (TasP) of HIV and TB. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieffenbach CW. Preventing HIV transmission through antiretroviral treatment-mediated virologic suppression: aspects of an emerging scientific agenda. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2012; 7:106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granich R, Williams B, Montaner J. Fifteen million people on antiretroviral treatment by 2015: treatment as prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2013; 8:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RJ, Okano JT, Kahn JS, Bodine EN, Blower S. Evolutionary dynamics of complex networks of HIV drug-resistant strains: the case of San Francisco. Science 2010; 327:697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood N, Wagner Z, Jaycocks A, Drabo E, Vardavas R. Test-and-treat in Los Angeles: a mathematical model of the effects of test-and-treat for the population of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles County. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:1789–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL et al. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS 1997; 11: F59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P et al. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS 2003; 17:887–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA 1998; 280:547–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill VS, Lima VD, Zhang W et al. Improved virological outcomes in British Columbia concomitant with decreasing incidence of HIV type 1 drug resistance detection. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50:98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrigan PR, Hogg RS, Dong WW et al. Predictors of HIV drug-resistance mutations in a large antiretroviral-naive cohort initiating triple antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch MS, Gunthard HF, Schapiro JM et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adult HIV-1 infection: 2008 recommendations of an International AIDS Society-USA panel. Top HIV Med 2008; 16:266–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood E, Montaner JS, Yip B et al. Adherence and plasma HIV RNA responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected injection drug users. CMAJ 2003; 169:656–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood E, Hogg RS, Lima VD et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and survival in HIV-infected injection drug users. JAMA 2008; 300:550–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 138:923–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:1215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP et al. Correlates of retention in HIV care after release from jail: results from a multi-site study. AIDS Behav 2013; 17(suppl 2): S156–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale HB, Rodriguez MD, Hoffman HJ et al. Progress realized: trends in HIV-1 viral load and CD4 cell count in a tertiary-care center from 1999 through 2011. PloS One 2013; 8: e56845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore RD, Keruly JC, Bartlett JG. Improvement in the health of HIV-infected persons in care: reducing disparities. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:1242–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Metlay JP, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Sustained viral suppression in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2012; 308:339–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore RD, Bartlett JG. Dramatic decline in the HIV-1 RNA level over calendar time in a large urban HIV practice. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:600–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerr T, Marshall BD, Milloy MJ et al. Patterns of heroin and cocaine injection and plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among a long-term cohort of injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012; 124:108–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Bangsberg DR et al. Homelessness as a structural barrier to effective antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive illicit drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26:60–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Buxton J et al. Social and environmental predictors of plasma HIV RNA rebound among injection drug users treated with antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 59:393–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saenz RA, Bonhoeffer S. Nested model reveals potential amplification of an HIV epidemic due to drug resistance. Epidemics 2013; 5:34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milloy MJ, Montaner J, Wood E. Barriers to HIV treatment among people who use injection drugs: implications for ‘treatment as prevention’. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2012; 7:332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westergaard RP, Hess T, Astemborski J, Mehta SH, Kirk GD. Longitudinal changes in engagement in care and viral suppression for HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS 2013; 27:2559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA 2009; 301:848–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]