Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this prospective registry-based population study was to investigate the efficacy of extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) regarding local recurrence rates within 3 years after surgery.

Background:

Local recurrence of rectal cancer is more common after abdominoperineal excision (APE) than after anterior resection. Extralevator abdominoperineal excision was introduced to address this problem. No large-scale studies with long-term oncological outcomes have been published.

Methods:

All Swedish patients operated on with an APE and registered in the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry 2007 to 2009 were included (n = 1397) and analyzed with emphasis on the perineal part of the operation. Local recurrence at 3 years was collected from the registry.

Results:

The local recurrence rates at 3 years [median follow-up, 3.43 years (APE, 3.37 years; ELAPE, 3.41 years; not stated: 3.43 years)] were significantly higher for ELAPE compared with APE (relative risk, 4.91). Perioperative perforation was also associated with an increased risk of local recurrence (relative risk, 3.62). There was no difference in 3-year overall survival between APE and ELAPE. In the subgroup of patients with very low tumors (≤4 cm from the anal verge), no significant difference in the local recurrence rate could be observed.

Conclusions:

Extralevator abdominoperineal excision results in a significantly increased 3-year local recurrence rate as compared with standard APE. Intraoperative perforation seems to be an important risk factor for local recurrence. In addition to significantly increased 3-year local recurrence rates, the significantly increased incidence of wound complications leads to the conclusion that ELAPE should only be considered in selected patients at risk of intraoperative perforation.

Keywords: abdominoperineal excision, APE, ELAPE, extralevator abdominoperineal excision, rectal cancer

Distal rectal cancer is operated on with an abdominoperineal excision (APE) when an anterior resection with an anastomosis cannot be performed.1,2 Local recurrence rates are higher after APE than after anterior resection as reported in several studies.3–9 Holm and colleagues10–12 proposed a more extensive procedure, the extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE), to improve local tumor control and with the aim to reduce local recurrence.12–14 Extralevator abdominoperineal excision results in a cylindrical specimen without a “waist,” common after standard APE, to minimize the risk of inadvertent tumor involvement of the circumferential resection margin (CRM) and to reduce the risk of intraoperative tumor perforation. The results of ELAPE have been analyzed in 3 systematic reviews15–17 with different conclusions regarding the oncological safety and superiority of ELAPE. Recently, Klein and colleagues18 presented short-term data on the basis of the Danish registry, including patients operated on between 2009 and 2012, and did not find any oncological advantage with ELAPE. In a large multicenter study, Ortiz and colleagues19 found no advantages of ELAPE compared with standard APE regarding mortality, local recurrence, intraoperative tumor perforation, or CRM involvement. We have previously reported short-term oncological outcomes from a Swedish national cohort of patients undergoing APE or ELAPE in 2007 to 2009. We found in a subgroup analysis that ELAPE resulted in fewer intraoperative perforations than standard APE for the most distal tumors but no differences in CRM involvement or intraoperative perforations for the entire group.20 Furthermore, ELAPE seemed to generate more wound-related complications especially increased incidence of wound infections than standard APE.21,22

The primary objective of this study was to compare long-term oncological outcomes after ELAPE and standard APE.

METHODS

A detailed description of the study has previously been published.21

Data From the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry

The Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry23 was used to retrieve perioperative data on patients operated on between 2007 and 2009 such as cTNM classification, level of tumor from the anal verge, patient demographics, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, preoperative adjuvant treatment, operative technique, perioperative complications, and perforation of the specimen. Postoperative data such as pTNM classification, CRM, distal margin, lymph node harvest, and involvement were included, as were postoperative complications. Postoperative data such as adjuvant treatment, local recurrence, and survival until 3 years postoperatively were also collected from the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry and from the Swedish Population Register.

Data From Operative Notes

Description of the perineal dissection was not included in the registry at this time. Therefore, operative notes for each patient were collected from the hospital where the patient was operated on. A clinical record form was developed and used to extract the specific details of the perineal part of the procedure.21 All retrieved operative notes were read and analyzed using the clinical record form. The operating notes were reviewed by one of the authors (MP). The operation was considered an extralevator APE if the operation was described in the operating chart as a “Holm procedure,” if it was described as a cylindrical specimen, or if it was stated that the levator muscle was dissected laterally or with a distance from the rectum. In the case of uncertainty as to how the dissection was done, operative notes were reviewed by 2 other authors (EH and EA) separately. The operation type was classified as “not stated” if no consensus was reached or if all agree that it was impossible to classify the procedure.

Using this information, the patients were classified as belonging to one of the following 3 groups: “APE”—operated on with a traditional APE; “ELAPE”—operated on with an extralevator APE; “not stated”—where the classification of type of perineal dissection from the operating notes was not possible.

Patient Questionnaires

All patients who were alive 3 years after the index surgery were asked to answer an extensive questionnaire. The questionnaire includes functional aspects and quality of life experiences and has been validated in a pilot study.24 Results will be presented separately.

Statistics

All data were collected in a database and statistical analysis was performed using SAS v. 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R v. 3.1.0. Patient characteristics were summarized descriptively. Continuous outcome variables were compared between the 3 groups using analysis of variance, and categorical data were compared between the 3 groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Because of multiplicity, statistical significance should be interpreted with caution and should mainly serve as highlighting noteworthy differences.

To assess the primary objective exploring differences between APE and ELAPE with regard to local recurrence within 3 years, odds ratios were estimated by logistic regression. Relative risk was estimated by Poisson regression with robust error variances because of failure of convergence of the log-binomial model. The results are presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

When quantifying the group-specific risk of local recurrence, identifying and adjusting for possible influential variables is needed. The pool of variables was clinical and pathology T- and N-stage, CRM, sex, ASA, bleeding (mean centered), operating time (mean centered), perioperative perforation, and preoperative radiotherapy. Variables not included were participation in preoperative multidisciplinary therapy conference, as participation in multidisciplinary therapy conference was at such high levels in all 3 groups that further distinction of the influence of this variable was impossible, and tumor level from the anal verge. Tumor level was not included as data suggested that this factor was part of the rationale for choice of ELAPE versus APE. For each variable considered potentially clinically relevant and represented in both surgical techniques, a regression model including operating technique was fit. Variables with a P value of less than 0.2 for a Wald test of the true regression coefficient being zero were included in a multivariate regression model. The relative risk was estimated by Poisson regression using the same variables as in the logistic regression.

In a previous subgroup analysis of tumors 4 cm or less, we found a higher rate of perforations in the APE group compared with the ELAPE group.20 This subgroup was analyzed here with regard to local recurrence by estimation in a multivariate model, with the same explanatory variables as in the model for the main group. The outcome of this analysis should be regarded as an interesting finding rather than as conclusive evidence.

RESULTS

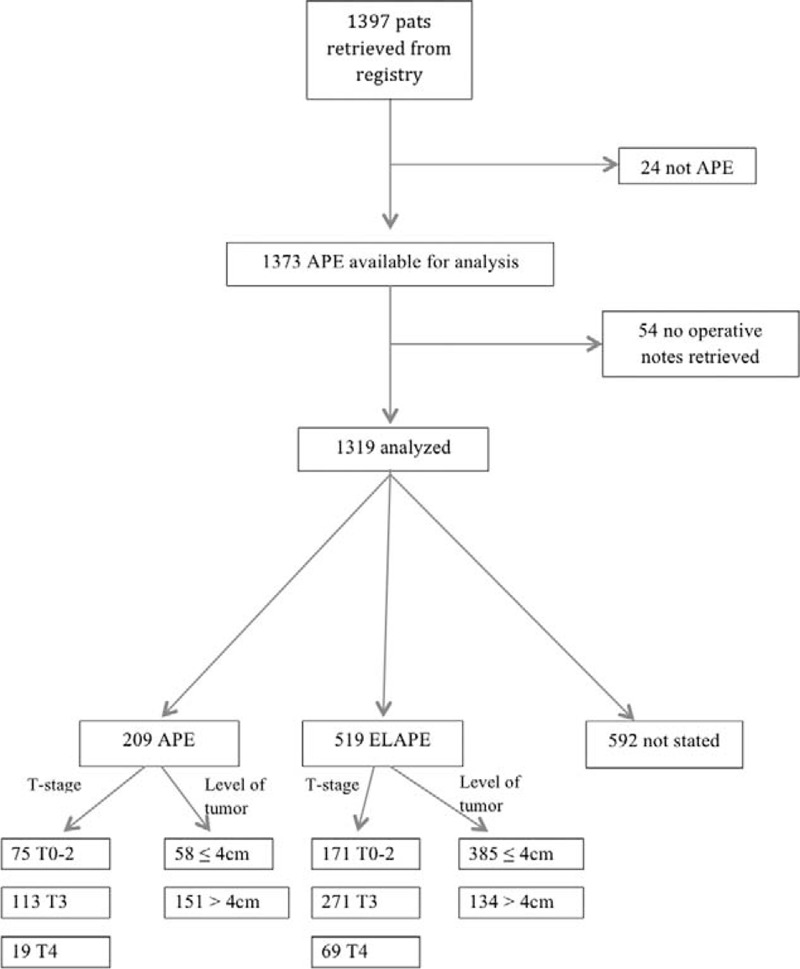

A total of 1397 patients were collected from the registry. In the flow chart (Fig. 1), exclusions are described, leaving 1319 patients for the analysis. For the group excluded because of the lack of surgical notes (4%), clinical and demographic data from the registry did not differ compared with the patients included in the study.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study population.

Patient characteristics are found in Table 1. There were more T0 to T2 tumors in the “not stated” group, but T-stage was similar between APE and ELAPE groups. M-stage differed between groups with more patients with distant metastases in the APE group 17% versus ELAPE 9% and “not stated” 10%. Regarding tumor level from the anal verge, the groups differed with a larger proportion of tumors (≤4 cm) from the anal verge in the ELAPE group compared with the other 2 groups. Preoperative radiotherapy and radiochemotherapy were part of treatment for the majority of patients regardless of the operative technique. However, more patients in the ELAPE group (88%) received radiotherapy compared with APE (69%) and “not stated” (80%). To identify possible influential variables, bivariate regression models were fit with each of the prespecified variables as covariates (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics in APE, ELAPE, and the Group Without Description of the Type of Perineal Dissection (“Not Stated”)

| APE | ELAPE | “Not Stated” | Total | P* | |

| Patients—n (%) | 209 (16) | 518 (39) | 592 (45) | 1319 | |

| Age, yrs—median (interquartile range) | 71 (63–79) | 68 (61–76) | 70 (62–78) | 69 (62–77) | 0.004 |

| BMI, kg/m2—median (interquartile range) | 25.1 (22.3–27.9) | 25.0 (22.6–28.1) | 24.9 (22.8–27.7) | 25.0 (22.6–27.8) | 0.712 |

| Female/male—n (%) | 93/116 (44/56) | 209/309 (40/60) | 228/364 (39/61) | 530/789 (40/60) | 0.289 |

| ASA, 1/2/3/4—n (%) | 35/113/57/2 (17/55/27/1) | 115/281/104/4 (23/56/21/1) | 124/320/121/5 (22/56/21/1) | 274/714/282/11 (21/56/22/1) | 0.019 |

| pT-stage, 0–2/3/4—n (%) | 75/113/19 (36/55/9) | 172/270/69 (34/53/13) | 237/314/32 (41/54/5) | 484/697/120 (37/54/9) | 0.001 |

| pN-stage, 0/1/2/X—n (%) | 121/37/46/5 (58/18/22/2) | 288/125/93/12 (56/24/18/2) | 324/152/103/12 (55/26/17/2) | 733/314/242/29 (56/24/18/2) | 0.12† |

| M-stage, 0/1/X—n (%) | 170/35/4 (81/17/2) | 461/44/12 (89/9/2) | 512/58/18 (87/10/3) | 1143/137/34 (87/10/3) | 0.001‡ |

| Tumor differentiation, low/medium/high/unknown—n (%) | 27/151/16/14 (13/73/8/7) | 75/358/33/52 (14/69/6/10) | 102/391/42/51 (17/67/7/9) | 204/901/91/117 (16/69/7/9) | 0.233 |

| Tumor level from anal verge, cm—median (interquartile range) | 6.0 (4–9) | 3.0 (2–4) | 4.0 (2–5) | 4.0 (2–5) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor level from anal verge, 0–4.9 cm—n (%) | 58 (28) | 386 (75) | 353 (61) | 797 (61) | <0.0001 |

| Tumor level from anal verge, ≥5 cm—n (%) | 151 (72) | 128 (25) | 226 (39) | 505 (39) | <0.0001 |

| CRM, positive/negative§—n (%) | 58/151 (28/72) | 152/366 (29/71) | 238/352 (40/60) | 448/869 (34/66) | <0.0001 |

| Preoperative radiotherapy—n (%) | 144 (69) | 456 (88) | 472 (80) | 1072 (81) | <0.0001 |

| Preoperative radiochemotherapy—n (%) | 32 (15) | 159 (31) | 88 (15) | 279 (21) | <0.0001 |

| Type of radiotherapy, short||/long¶/other—n (%) | 109/34/1 (76/24/1) | 284/166/5 (62/36/1) | 365/99/5 (78/21/1) | 758/299/11 (71/28/1) | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding, mL—median (interquartile range) | 600 (300–1000) | 550 (300–900) | 500 (300–900) | 500 (300–900) | 0.325 |

*Based on the analysis of variance for continuous data and Kruskal-Wallis test for categorical data.

†pNX were excluded from the analysis.

‡MX were excluded from the analysis.

§Positive: <2 mm; negative: ≥2 mm.

||Short radiotherapy equals 5 Gy × 5.

¶Long radiotherapy equals 1.8/2.0 Gy × 25.

BMI indicates body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate∗ Logistic Regression Analyses With Odds Ratios Indicating the Risk of Local Recurrence

| Variable | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Pathology T-stage | <0.001 | – |

| 0 | – | Reference |

| 1 | N/A† | |

| 2 | 0.283 | 0.41 (0.09–2.85) |

| 3 | 0.778 | 1.23 (0.36–7.77) |

| 4 | 0.101 | 3.55 (0.96–23.05) |

| Pathology N-stage | 0.001 | – |

| 0 | – | Reference |

| 1 | 0.402 | 1.32 (0.69–2.54) |

| 2 | <0.001 | 2.82 (1.56–5.09) |

| Clinical T-stage | 0.002 | – |

| 1–2 | Reference | |

| 0 | N/A† | |

| 3 | 0.094 | 2.32 (0.87–6.24) |

| 4 | 0.001 | 5.44 (2.05–14.4) |

| Clinical N-stage | 0.278 | – |

| 0 | Reference | |

| 1–2 | 0.278 | 1.38 (0.77–2.47) |

| CRM | <0.001 | |

| Negative | Reference | |

| Positive | <0.001 | 2.49 (1.49–4.13) |

| Sex | 0.176 | – |

| Male | – | Reference |

| Female | 0.176 | 1.41 (0.85–2.33) |

| ASA class | 0.933 | – |

| 1 | – | Reference |

| 2 | 0.536 | 1.23 (0.63–2.41) |

| 3 | 0.741 | 0.87 (0.37–2.04) |

| 4 | 0.438 | 2.34 (0.27–20.14) |

| Bleeding (500 mL) | 0.006 | 1.13 (1.04–1.23) |

| Operating time (120 min) | 0.646 | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) |

| Perioperative perforation | <0.001 | – |

| No | – | Reference |

| Yes | <0.001 | 5.08 (2.81–9.19) |

| Preoperative radiotherapy | 0.177 | – |

| No | – | Reference |

| Yes | 0.177 | 0.65 (0.35–1.21) |

*Group is included as a factor in all analyses.

†No recurrence in pathology T-stage 1, and clinical T-stage 0, therefore not possible to calculate.

CI indicates confidence interval.

All variables but clinical N-stage, ASA-classification, and Operating Time were included in a multivariate logistic regression. Variables such as pathology T-stage, preoperative radiotherapy, CRM, and sex were subsequently removed because of having P values more than 0.20. pT-stage and cT-stage were highly correlated, and pT-stage was thus removed as cT-stage made a larger reduction in the Akaike information criterion compared with pT-stage. The most pronounced interactive effect was between bleeding and pT-stage (P = 0.169) but this was not included in the model because it gave no reduction in the Akaike information criterion. There was no serious multicollinearity between the variables in the final model. The results for the multivariate model are presented in Table 3 and the relative risk in Table 4. Results for the subgroup analysis are presented in Tables 5 and 6.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses With Odds Ratios Indicating the Risk of Local Recurrence (n = 1319)

| Variable | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Group | 0.076 | – |

| APE | – | Reference |

| ELAPE | 0.025 | 4.10 (1.19–14.08) |

| Not stated | 0.082 | 3.06 (0.87–10.78) |

| Pathology N-stage | 0.011 | – |

| 0 | – | Reference |

| 1 | 0.206 | 1.63 (0.76–3.48) |

| 2 | 0.003 | 2.98 (1.47–6.04) |

| Clinical T-stage | 0.091 | – |

| 1–2 | Reference | |

| 0 | N/A* | |

| 3 | 0.244 | 1.83 (0.66–5.09) |

| 4 | 0.022 | 3.33 (1.19–9.29) |

| Bleeding (500 mL) | 0.043 | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) |

| Perioperative perforation | <0.001 | – |

| No | – | Reference |

| Yes | <0.001 | 5.30 (2.64–10.66) |

*No recurrence in clinical T-stage 0, therefore not possible to calculate.

CI indicates confidence interval.

TABLE 4.

Multivariate∗ Poisson Regression Analyses With Relative Risk of Local Recurrence (n = 1319)

| Variable | P | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

| Group | 0.006 | – |

| APE | – | Reference |

| ELAPE | 0.007 | 4.91 (1.53–15.74) |

| Not stated | 0.087 | 2.82 (0.86–9.26) |

| Perioperative perforation | <0.001 | – |

| No | – | Reference |

| Yes | <0.001 | 3.62 (2.13–6.13) |

*Additional covariates are pathology N-stage, clinical T-stage, nodes, and bleeding.

CI indicates confidence interval.

TABLE 5.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses With Odds Ratios Indicating the Risk of Local Recurrence∗

| Variable | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Group | 0.515 | – |

| APE | – | Reference |

| ELAPE | 0.258 | 3.42 (0.41–28.87) |

| Not stated | 0.331 | 2.94 (0.33–25.93) |

| Pathology N-stage | 0.039 | – |

| 0 | – | Reference |

| 1 | 0.114 | 2.05 (0.84–5.04) |

| 2 | 0.012 | 3.09 (1.28–7.49) |

| Clinical T-stage | 0.048 | – |

| 1–2 | Reference | |

| 0 | N/A† | |

| 3 | 0.085 | 3.86 (0.83–17.94) |

| 4 | 0.010 | 7.51(1.63–34.52) |

| Bleeding (500 mL) | 0.632 | 1.04 (0.88–1.24) |

| Perioperative perforation | <0.001 | – |

| No | – | Reference |

| Yes | <0.001 | 8.90 (3.84–20.65) |

*Subgroup of patients with tumors 4 cm or less from the anal verge (n = 797).

†No recurrence in clinical T-stage 0, therefore not possible to calculate.

CI indicates confidence interval.

TABLE 6.

Multivariate∗ Poisson Regression Analyses With Relative Risk of Local Recurrence

| Variable | P | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

| Group | 0.530 | – |

| APE | – | Reference |

| ELAPE | 0.281 | 3.05 (0.40–23.08) |

| Not stated | 0.662 | 1.15 (0.61–2.20) |

| Perioperative perforation | <0.001 | – |

| No | – | Reference |

| Yes | <0.001 | 5.96 (3.19–11.14) |

Subgroup of patients with tumors 4 cm or less from the anal verge (n = 797).

*Additional covariates are pathology N-stage, clinical T-stage, nodes, and bleeding.

CI indicates confidence interval.

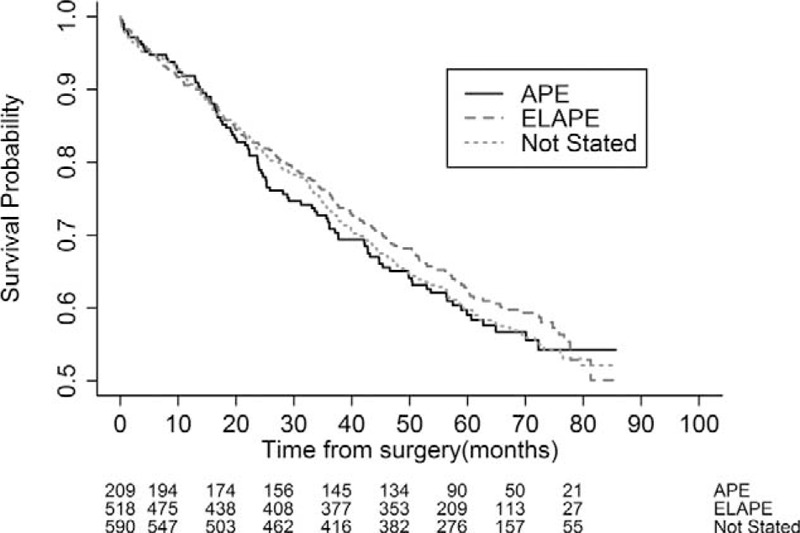

No difference was found in 3-year overall survival between groups (Fig. 2). Three-year local recurrence rates were higher for ELAPE than for APE, with a relative risk of 4.91 [median follow-up, 3.43 years (APE, 3.37 years; ELAPE, 3.41 years; not stated, 3.43 years)]. The relative risk of local recurrence for perioperative perforation was 3.62. In the subgroup of patients with tumors 4 cm or less, the corresponding figure was 3.05 and 5.96, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots of overall survival for the 3 groups (APE, ELAPE, and “not stated” groups).

DISCUSSION

In this study of a large national cohort of patients operated on with APE, we found no reduction in 3-year local recurrence for ELAPE compared with standard APE. There was no difference in 3-year overall survival. However, risk factors for local recurrence were more advanced tumors (T4- and N2-stages) and intraoperative perforation.

The major strength of our study is that it is a population-based and relatively large and national cohort. The cohort comprises 94% of all Swedish patients operated on with any kind of APE in the years 2007 to 2009. Selection bias should therefore not be a problem. This is a strength compared with other reports presenting data from selected case series11 or by selection of including centers.19 The Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry is a well-established registry, with high coverage and regular updating, which has undergone validations.23,25,26 The cohort is prospectively registered, and the time frame of the inclusion is recent and relevant. There were no comparisons to historical data, but rather between contemporary practices within the same health care system. Furthermore, the missing data are low for the variables collected from the registry. We were able to collect operative notes for a high proportion of included patients. We have a model for analysis, which can be used for a reevaluation for a cohort from the time point when the Swedish ColoRectal Cancer Registry included data on perineal dissections techniques.

Previous reports on ELAPE have been varying; West et al10,11 described lower perforation rates and fewer cases with involved CRM using ELAPE in a comparison with historical controls with high rates of both perforations and involved margins. Stelzner et al15 suggested from a systematic review of 14 nonrandomized studies in the time frame of 1997 to 2011 on “extended APE” and 50 studies on traditional APE from 1991 to 2011 that “extended APE” had a reduced risk of intraoperative perforation. It was not possible to analyze the effects on local recurrence and survival rates in their review. Other reports of case series with historical controls have been unable to confirm these findings.16,22 More recently, Ortiz and colleagues19 present propensity score-matched data on 914 patients from 2008 to 2013 with no advantage for ELAPE on intraoperative perforations, involved CRM, local recurrence, or mortality. Their study is a prospectively registered, large, multicenter study. The fact that not all Spanish centers took part may represent a possible selection bias. In addition, a recently presented study from Denmark18 on all Danish patients operated on with standard APE or ELAPE from 2009 to August 2012 shows no benefit for ELAPE regarding short-term oncological outcomes (involved CRM). One randomized controlled trial by Han et al27 reported reduced recurrence rates after ELAPE, suggesting that there is an oncological advantage with ELAPE in comparison with traditional APE in patients with T3 and T4 tumors. However, their study was small (n = 67) and lacked details of external and internal validity. Because of these methodological weaknesses, their findings may be regarded as interesting but not conclusive.

There are limitations in our study. Although the national coverage of the registry is more than 97%, there are still missing data. However, for most variables reported, the rate of missing data is low and ranges from 0% to 3%. A 3-year follow-up has the advantage of a more rapid presentation of results, but the limitation is a relatively low event rate and a lack of 5-year long-term data. There seems to have been a selection bias in favor of ELAPE for patients with the most distal tumors, indicating that there may have been a perception among Swedish colorectal surgeons that there was an advantage of ELAPE for patients with distal tumors. This might affect the possibility to compare the 2 techniques in our study. Another limitation is that the national registry did not include data on the perineal dissection technique at that time. The large proportion of operative notes that could not be classified as APE or ELAPE (the “not stated” group) limits the possibility to draw accurate and definitive conclusions. In this publication, we have chosen to present all groups, and our interpretation of the results is that this group included cases performed as APE and cases performed as ELAPE (ie, a mixed group). There is no indication that the lack of detail regarding the description of the perineal dissection performed is an indication of “poor surgery.”

Interestingly, although intraoperative perforation appears as a major risk factor for local recurrence and we found a lower incidence of intraoperative perforations for the more distal tumors (≤4 cm from the anal verge)20 using the ELAPE technique compared with APE, there was still an higher rate of local recurrence in the ELAPE group.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe, on the basis of the results from this study and supported by the results from Ortiz et al, that ELAPE should not be suggested as a standard operative technique for all low rectal cancers. On the basis of our results, we suggest that ELAPE should be used with discretion, primarily for cases with high risk of intraoperative perforation—which in our study seems as a major risk factor for local recurrence.

Analyses of patient-reported functional outcomes and quality of life 3 years after surgery in the same cohort will shed further light on the effects of the 2 different techniques.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2012–1768), the Swedish Cancer Society (2010/593, 2013/497), Ruth and Richard Julin's Foundation, the Assar Gabrielssons Foundation, the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, the Bengt Ihre Foundation, Lion's Cancer Foundation West, Region Västra Götaland, Sahlgrenska University Hospital (ALF grant, agreement concerning research and education of doctors), and the Health & Medical Care Committee of the Regional Executive Board, Region Västra Götaland. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miles WE. A method of performing abdomino-perineal excision for carcinoma of the rectum and of the terminal portion of the pelvic colon (1908). CA Cancer J Clin 1971; 21:361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry WB, Connaughton JC. Abdominoperineal resection: how is it done and what are the results? Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2007; 20:213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.How P, Shihab O, Tekkis P, et al. A systematic review of cancer related patient outcomes after anterior resection and abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer in the total mesorectal excision era. Surg Oncol 2011; 20:e149–e155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shihab OC, Brown G, Daniels IR, et al. Patients with low rectal cancer treated by abdominoperineal excision have worse tumors and higher involved margin rates compared with patients treated by anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2010; 53:53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wibe A, Syse A, Andersen E, et al. Oncological outcomes after total mesorectal excision for cure for cancer of the lower rectum: anterior vs. abdominoperineal resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47:48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Dulk M, Putter H, Collette L, et al. The abdominoperineal resection itself is associated with an adverse outcome: the European experience based on a pooled analysis of five European randomised clinical trials on rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45:1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.den Dulk M, Marijnen CA, Putter H, et al. Risk factors for adverse outcome in patients with rectal cancer treated with an abdominoperineal resection in the total mesorectal excision trial. Ann Surg 2007; 246:83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marr R, Birbeck K, Garvican J, et al. The modern abdominoperineal excision: the next challenge after total mesorectal excision. Ann Surg 2005; 242:74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagtegaal ID, van de Velde CJ, Marijnen CA, et al. Low rectal cancer: a call for a change of approach in abdominoperineal resection. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:9257–9264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West NP, Finan PJ, Anderin C, et al. Evidence of the oncologic superiority of cylindrical abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:3517–3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West NP, Anderin C, Smith KJ, et al. Multicentre experience with extralevator abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2010; 97:588–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holm T, Ljung A, Haggmark T, et al. Extended abdominoperineal resection with gluteus maximus flap reconstruction of the pelvic floor for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2007; 94:232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore TJ, Moran BJ. Precision surgery, precision terminology: the origins and meaning of ELAPE. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14:1173–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shihab OC, Heald RJ, Holm T, et al. A pictorial description of extralevator abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14:e655–e660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stelzner S, Koehler C, Stelzer J, et al. Extended abdominoperineal excision vs. standard abdominoperineal excision in rectal cancer—a systematic overview. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011; 26:1227–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna A, Rickard MJ, Keshava A, et al. A comparison of published rates of resection margin involvement and intra-operative perforation between standard and ‘cylindrical’ abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2013; 15:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu HC, Peng H, He XS, et al. Comparison of short- and long-term outcomes after extralevator abdominoperineal excision and standard abdominoperineal excision for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014; 29:183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein M, Fischer A, Rosenberg J, et al. ExtraLevatory AbdominoPerineal Excision (ELAPE) does not result in reduced rate of tumor perforation or rate of positive circumferential resection margin: a nationwide database study. Ann Surg 2015; 261:933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortiz H, Ciga MA, Armendariz P, et al. Multicentre propensity score-matched analysis of conventional versus extended abdominoperineal excision for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2014; 101:874–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prytz M, Angenete E, Ekelund J, et al. Extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) for rectal cancer-short-term results from the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry. Selective use of ELAPE warranted. Int J Colorectal Dis 2014; 29:981–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prytz M, Angenete E, Haglind E. Abdominoperineal extralevator resection. Dan Med J 2012; 59:A4366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asplund D, Haglind E, Angenete E. Outcome of extralevator abdominoperineal excision compared with standard surgery. Results from a single centre. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14:1191–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pahlman L, Bohe M, Cedermark B, et al. The Swedish rectal cancer registry. Br J Surg 2007; 94:1285–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angenete E, Correa-Marinez A, Heath J, et al. Ostomy function after abdominoperineal resection—a clinical and patient evaluation. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012; 27:1267–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorgren F, Johansson R, Damber L, et al. Risk factors of rectal cancer local recurrence: population-based survey and validation of the Swedish rectal cancer registry. Colorectal Dis 12:977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunnarsson U, Seligsohn E, Jestin P, et al. Registration and validity of surgical complications in colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 2003; 90:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han JG, Wang ZJ, Wei GH, et al. Randomized clinical trial of conventional versus cylindrical abdominoperineal resection for locally advanced lower rectal cancer. Am J Surg 2012; 204:274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]