Abstract

Cytokines are potent mediators of cellular communication that have crucial roles in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunoinflammatory responses. Clear evidence has emerged in recent years that the dysregulated production of cytokines may in itself be causative in the pathogenesis of certain immunoinflammatory disorders. Here we review current evidence for the involvement of two different cytokines, IFN‐α and IL‐6, as principal mediators of specific immunoinflammatory disorders of the CNS. IFN‐α belongs to the type I IFN family and is causally linked to the development of inflammatory encephalopathy exemplified by the genetic disorder, Aicardi–Goutières syndrome. IL‐6 belongs to the gp130 family of cytokines and is causally linked to a number of immunoinflammatory disorders of the CNS including neuromyelitis optica, idiopathic transverse myelitis and genetically linked autoinflammatory neurological disease. In addition to clinical evidence, experimental studies, particularly in genetically engineered mouse models with astrocyte‐targeted, CNS‐restricted production of IFN‐α or IL‐6 replicate many of the cardinal neuropathological features of these human cytokine‐linked immunoinflammatory neurological disorders giving crucial evidence for a direct causative role of these cytokines and providing further rationale for the therapeutic targeting of these cytokines in neurological diseases where indicated.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Inflammation: maladies, models, mechanisms and molecules. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2016.173.issue-4

Abbreviations

- ADAR

adenosine deaminases acting on RNA

- AGS

Aicardi–Goutières syndrome

- AQP4

aquaporin 4

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CCL

CC‐chemokine ligand

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GFAP‐IFNα

transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of IFN‐α

- GFAP‐IL6

transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of IL6

- HAD

HIV‐associated dementia

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IBGC

idiopathic basal ganglia calcification

- IFIH1

IFN‐induced with helicase C domain 1

- IFNAR

IFN‐I receptor

- IFN‐I

type I IFN

- IRG

IFN‐regulated gene

- ISG

IFN‐stimulated gene

- ITM

idiopathic transverse myelitis

- MDA5

melanoma differentiation associated protein 5

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NMO

neuromyelitis optica

- SAMHD1

SAM domain HD‐domain‐containing protein 1

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TREX

3′ repair exonuclease

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Catalytic receptors a |

| Gp130 (IL‐6 receptor, β subunit) |

| IFNAR1, IFN‐I receptor |

| IL‐6R, IL‐6 receptor a |

| Enzymes b |

| JAK, Janus kinase |

| PARP, polyADP ribose polymerase |

| SHP2, receptor tyrosine phosphatase |

| Ion channels c |

| AQP4, aquaporin‐4 water channel |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2013c).

Introduction

Cytokines are a large and diverse group of proteins that not only regulate inflammation and immunity but also are extraordinarily pleiotropic, altering the function of most cells in the body including those of the CNS. They act as crucial mediators in the bidirectional signalling between the immune system and the brain. In view of their potent activity, the cellular production of most proinflammatory cytokines in the CNS is under stringent control with very low levels present under physiological conditions. However, the local production of cytokines increases significantly in the CNS following infection, injury and in autoimmune disorders affecting the CNS with some notable examples including multiple sclerosis (MS), neuromyelitis optica (NMO), subacute sclerosing pan encephalitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐associated dementia (HAD), Alzheimer's disease, viral and bacterial meningoencephalitis and stroke (see Rothwell and Hopkins, 1995; John et al., 2003; Steinman, 2008; Uzawa et al., 2014a).

The question of whether cytokines also have a causal role in mediating neurological disease has attracted much interest in recent years. This notion has gained considerable traction from genetic studies identifying specific mutations that lead to increased production of cytokines within the CNS of patients with inflammatory encephalopathy. Furthermore, clinical trials have highlighted significant amelioration of certain neuroinflammatory diseases in patients following intervention with new therapies that target the actions of specific cytokines. Here we review current evidence for the involvement of two different cytokines, IFN‐α and IL‐6, as principal mediators of specific immunoinflammatory disorders of the CNS. In addition to the clinical evidence, we will highlight experimental studies, particularly in transgenic mouse models with CNS‐targeted production of IFN‐α or IL‐6. These transgenic models replicate many of the cardinal neuropathological signs of these human disorders, providing crucial evidence for a direct causal role of these cytokines.

Type I IFN (IFN‐I) and IL‐6 – a brief general perspective

Following viral infection of the host, a rapid deployment of the innate immune response is essential for limiting viral replication and dissemination as well as for promoting viral clearance. A crucial function of innate immunity is the secretion of cytokines such as the IFN‐I and IL‐6. These cytokines have major roles in host antimicrobial defence as powerful immunoregulatory cytokines that couple the innate and adaptive immune responses (Kishimoto, 2005; Seo and Hahm, 2010; Gonzalez‐Navajas et al., 2012; Rincon, 2012).

Since the discovery of IFN over half a century ago by Isaacs and Lindenmann (1957), it is now known that there is a family of these cytokines all with potent antiviral activity. This family is composed of three subfamilies: type I (IFN‐I) that has many members (IFN‐α1–α13, IFN‐β, IFN‐τ), a single type II IFN (IFN‐γ) and type III IFNs (IFN‐λ1–4). All members of the IFN‐I family bind to a single widely expressed heterodimeric receptor [IFN‐I receptor (IFNAR)1/IFNAR2] (reviewed in Thomas et al., 2011; de Weerd and Nguyen, 2012). Although the precise distribution and localization of the IFNAR in the CNS has not been resolved, it is likely to be ubiquitous given the widespread cellular responses to IFN‐I seen in the CNS as well as in vitro (Paul et al., 2007; Hofer and Campbell, 2013). This view is supported by recent RNAseq analysis showing the presence of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 mRNA transcripts in astrocytes, microglia, neurons, oligodendrocytes and cerebrovascular endothelial cells (Zhang et al., 2014b). The binding of IFN‐I to the IFNAR activates a signalling cascade leading to the JAK‐mediated phosphorylation of the transcription factors STAT1 and STAT2 (see Stark et al., 1998). Phosphorylated STAT1 and STAT2 molecules associate with another transcription factor, IFN regulatory factor 9, to form the IFN‐stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) that modulates the transcription of a large number of IFN‐regulated genes (IRGs). Other than this primary signalling pathway, IFN‐I can signal via a number of additional pathways, whose exact role in the IFN‐I response remains to be clarified (see van Boxel‐Dezaire et al., 2006).

IL‐6 was discovered originally as a protein that stimulated the differentiation of B‐cells (Hirano et al., 1985; 1986). It is now known that IL‐6 regulates a large range of biological functions in a variety of tissues and cells (reviewed in Hirano et al., 1990). IL‐6 binds to a transmembrane receptor termed IL‐6Rα that lacks intrinsic signal transduction capacity. Signal transduction following binding of IL‐6 to its receptor is mediated by association with an additional transmembrane protein termed the IL‐6 signal transducer or gp130. The pleiotropism of IL‐6 seems incongruous when it is considered that the surface of most cells including astrocytes (Marz et al., 1999; Van Wagoner et al., 1999) and neurons (Marz et al., 1997) but not microglia (Lin and Levison, 2009) is devoid of IL‐6R. This puzzle was resolved with the finding that the extracellular domain of the IL‐6R is shed from the cell surface and is found at high levels in extracellular fluids where, when bound to IL‐6, it is biologically active (see Rose‐John and Heinrich, 1994; Rose‐John et al., 2006). Because the cellular distribution of the gp130 protein is ubiquitous, the combination of IL‐6 plus the soluble (s)IL‐6R is capable of mediating the effects of this cytokine, even in cells that lack the IL‐6R, in a process that is termed trans‐signalling. The binding of IL‐6 to either the transmembrane or to the sIL‐6R triggers oligomerization with gp130 resulting in activation of associated JAKs with subsequent recruitment and phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3 as well as the protein tyrosine phosphatase, SHP2 (Ernst and Jenkins, 2004). STAT1 and STAT3 form homo‐ and heterodimers that translocate to the nucleus, bind to specific DNA recognition motifs in target genes and regulate transcriptional activity of the cell.

Cellular communication mediated by the IL‐6/sIL‐6R complex is antagonized by a naturally occurring soluble form of gp130 (sgp130) (Jostock et al., 2001). The sgp130 is also found in extracellular fluids and plasma and blocks trans‐signalling by binding the IL‐6/sIL‐6R complex. This property of sgp130 has been applied experimentally to distinguish trans‐signalling from conventional signalling (Rose‐John et al., 2006). Recent evidence indicates that IL‐6 trans‐signalling via the sIL‐6R is the primary pathway of IL‐6 cellular communication involved in the pathogenesis of various experimental models of acute and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases as well as certain neoplastic disorders (see Scheller et al., 2014).

IFN‐α as a causal factor in human CNS disease

A growing number of neuroinflammatory diseases have been identified whose pathogenesis is linked to chronically elevated IFN‐I levels in the CNS. These diseases have also been termed ‘type I interferonopathies’ (Crow, 2011) and share a number of clinicopathological features. They include Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS) (Aicardi and Goutieres, 1984; Aicardi, 2002), Cree encephalitis (Aicardi and Goutieres, 1984; Black et al., 1988a, 1988b; Aicardi, 2002), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)‐associated psychosis (Efthimiou and Blanco, 2009) and congenital (Shet, 2011) as well as chronic viral encephalopathies (Pontrelli et al., 1999).

AGS and Cree encephalitis are allelic hereditary disorders whose common characteristic feature is a progressive inflammatory encephalopathy (Aicardi and Goutieres, 1984; Black et al., 1988a, 1988b; Aicardi, 2002; Crow et al., 2003; Crow and Livingston, 2008). The neuropathological manifestations of AGS include microcephaly, calcifications in the basal ganglia and thalami, vasculopathy, leukodystrophy and CSF lymphocytosis (Aicardi and Goutieres, 1984; Aicardi, 2002; Stephenson, 2008; Chahwan and Chahwan, 2012). Symptoms are present usually in neonates and can include vomiting, feeding difficulties, convulsive seizures, retarded motor and social skill development and in some cases patients may die (Aicardi and Goutieres, 1984; Aicardi, 2002; Chahwan and Chahwan, 2012). In AGS and Cree encephalitis, IFN‐α is markedly increased in the CSF and is associated with an IRG signature in CSF lymphocytes (Lebon et al., 1988; 2002; Crow et al., 2003; Izzotti et al., 2009). Examination of post‐mortem brains from patients has revealed that astrocytes are the major source of IFN‐α production in AGS (van Heteren et al., 2008).

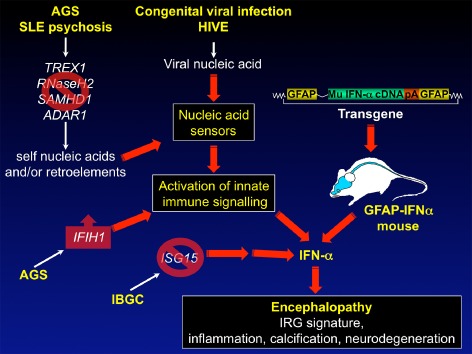

Our understanding of the genetic basis for type I interferonopathies has advanced greatly in recent years with the discovery of mutations in seven genes thought to cause AGS. These genes are the 3′ repair exonuclease 1 [TREX1; (AGS1)], components of the RNaseH2 complex [RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B and RNASEH2C; (AGS2‐4)], the SAM domain HD‐domain‐containing protein 1 [SAMHD1; (AGS5)], adenosine deaminases acting on RNA 1 [ADAR1; (AGS6)] and IFN‐induced with helicase C domain [IFN‐induced with helicase C domain 1 (IFIH1); (AGS7)] (Crow et al., 2000, 2006a, 2006b; Rice et al., 2009; 2012; 2014; Oda et al., 2014). TREX1 mutations also contribute to the pathogenesis of Cree encephalitis (Crow et al., 2003; 2006a). It is proposed that loss‐of‐function mutations in TREX1 result in the inappropriate accumulation of single‐stranded DNA derived from lagging‐strand DNA synthesis (Yang et al., 2007) and non‐processed endogenous retroelements (Crow et al., 2006a; Stetson et al., 2008) activating DNA sensors and triggering chronic production of IFN α. Interestingly, mice lacking the Trex1 gene die prematurely of severe inflammatory myocarditis (Morita et al., 2004) and show elevated myocardial IFN‐β mRNA levels (Stetson et al., 2008). In demonstrating the important role for IFN‐I signalling in this disease, TREX1‐deficient mice that lack IFNAR1 are protected from lethal inflammatory myocarditis (Stetson et al., 2008). Similarly, loss‐of‐function mutations in the genes encoding the RNaseH2 complex, SAMHD1 or ADAR1, may also result in the aberrant build‐up of nucleic acid species in the cell (Eder and Walder, 1991; Rydberg and Game, 2002; Yang et al., 2005; Goldstone et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2011; Rice et al., 2012). Although SAMHD1‐deficient mice develop no spontaneous phenotype (Rehwinkel et al., 2013), mice deficient for ADAR1 show increased IFN‐I levels and gross developmental abnormalities in a number of organs and die as embryos (Hartner et al., 2004; 2009; Wang et al., 2004). Concurrent loss of ADAR1 and IFNAR1 or STAT1 has only minor effects on embryonic lethality suggesting that, in this model, the IFN‐I are not essential (Mannion et al., 2014). However, lack of ADAR1 and MAVS, a downstream adaptor molecule of ADAR1, partially rescues the phenotype and the mice survive until shortly after birth indicating that embryonic death in the ADAR1 null mice is ultimately the consequence of an erroneously activated antiviral immune response (Mannion et al., 2014). Irrespective of the gene involved, the pathomechanisms in patients with AGS1‐6 mutations appear to utilize a similar process viz. the anomalous accumulation of nucleic acid species that trigger unidentified innate pattern recognition receptors to initiate an innate immune response with elevated IFN‐I production in the brain, resulting inflammatory encephalopathy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathways to IFN‐I‐mediated encephalopathy in mice and humans. In AGS, SLE encephalopathy or IBGC inactivating mutations occur in TREX1, RNASEH2, SAMHD1, ADAR1 or ISG15. AGS may also be caused by a gain‐of‐function mutation of the IFIH1 gene. These different mutations together with chronic viral infection of the CNS can lead to the inappropriate production of IFN‐α in the brain which then causes inflammatory encephalopathy with calcification and neurodegeneration. Many of the key neuropathological features of these human ‘interferonopathies’ are reproduced in GFAP‐IFNα transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of IFN‐α providing proof of principle that chronic elevation of IFN‐α in the brain may be a primary cause of disease in AGS.

The recently identified AGS7 is caused by mutations in the IFIH1 gene (Oda et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2014) that encodes for the cytoplasmic dsRNA helicase melanoma differentiation associated protein 5 (MDA5) important in innate virus detection. So far, all identified AGS7 mutations appear to cause a gain‐of‐function in MDA5 leading to the binding of an unidentified double‐stranded RNA species and subsequent activation of innate signalling with increased IFN‐I production. Mice with a similar gain‐of‐function mutation in Ifih1 develop an SLE‐like phenotype with spontaneous inflammation in the kidney and skin and calcification in the liver (the authors do not report on the CNS). These mice have increased cytokine production including IFN‐I for which the latter contributes to the disease as Ifih1:Ifnar1 double‐deficient mice have a partial amelioration of kidney pathology (Funabiki et al., 2014).

In addition to AGS, it has emerged that there are likely other type I interferonopathies with primary neurological involvement – idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (IBGC) or Fahr's disease being a recent example. Patients with IBGC show similar clinicopathological features to those seen in AGS including calcification of the basal ganglia. Although in most patients the cause is unknown, a subgroup of patients has mutations in the ISG15 gene (Bogunovic et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014a). These mutations render ISG15 non‐functional and result in exacerbated IFN‐I responses indicating that this form of IBGC may represent a type I interferonopathy. It will be of interest to see if other forms of IBGC have a similar underlying disease cause.

SLE is a multi‐organ autoimmune syndrome that can include the CNS. The aetiology of SLE is complex and involves genetic and environmental factors (see Deng and Tsao, 2010). Clinically, SLE patients have autoantibodies, complement activation, circulating immune complexes that contribute to progressive organ injury. Neurological involvement in SLE is often found and is associated with serious complications (see Blanco et al., 2001; Efthimiou and Blanco, 2009). Like AGS, pathological changes in the CNS in SLE include leukodystrophy and calcification in the basal ganglia and thalmi (see Rigby et al., 2008). Recently, a number of studies have provided several clues that link IFN‐I directly to the pathogenesis of SLE and in particular the neurological manifestations of SLE. First, elevated levels of IFN‐α are detected in the serum and CSF (Shiozawa et al., 1992; Blanco et al., 2001; Jonsen et al., 2003; Pascual et al., 2003). Second, the molecular basis leading to the elevated IFN‐I is unknown; however, polymorphisms in IFN‐I‐related genes including TYK2, IRF3, IRF5 or IRF7 are commonly found and may give rise to the elevated IFN‐I production (Sigurdsson et al., 2005; Akahoshi et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2012). Third, SLE occurs in some AGS patients (De Laet et al., 2005). Fourth, therapeutic use of high‐dose IFN‐I can induce SLE (Ronnblom et al., 1990). Finally, mutations in TREX1 (AGS1) and SAMHD1 (AGS5) occur in SLE patients with a cutaneous form of the disease (familial chilblain lupus) (Rice et al., 2007; Ravenscroft et al., 2011).

Persistent elevation of IFN‐I in the CNS is also linked to encephalopathies resulting from congenital or chronic viral infections. Congenital or perinatal infections of the CNS with a number of pathogens often have similar clinical symptoms (Shet, 2011). Neonatal HIV infection often causes motor impairment and cognitive decline with decreased intelligence (see Mitchell, 2006). Pathological findings in the brain reveal a microcephaly with ventricular swelling, leukodystrophy and vascular calcifications prominent in the basal ganglia (Brouwers et al., 1998; Civitello, 2005). These features can also often be found in congenital infection involving other viruses (Ishikawa et al., 1982; Noorbehesht et al., 1987; Taccone et al., 1988; Kenneson and Cannon, 2007). Significantly, increased CNS IFN‐I levels accompany pre‐ or neonatal infection with HIV (Krivine et al., 1999) and other viruses (Dussaix et al., 1985), suggesting there may be a similar pathogenetic mechanism to that in AGS (Krivine et al., 1999).

Similar to congenital viral infection, persistent viral infection of the adult CNS can lead to inflammatory encephalopathies. For example, up to 50% of HIV‐infected patients develop neurological symptoms (Liner et al., 2010) with approximately 10% developing HAD (Valcour et al., 2011). Histological changes in the CNS include characteristic microglial nodules and multinucleated macrophages, astrocytosis and reduced neuronal density while neuronal apoptosis is increased (Gray et al., 1996; Petito et al., 2003). Interestingly, calcifications are not found in the CNS of patients with HAD (Belman et al., 1986; Kauffman et al., 1992). The neuronal damage that is observed may result from neurotoxicity mediated by a variety of cytokines and chemokines that include IFN‐α, TNF‐α and CCL2 (Tyor et al., 1992; Rho et al., 1995; Zheng et al., 2001; Ryan et al., 2002; Cook et al., 2005). Consistent with a role for IFN‐α in the pathogenesis of HAD, levels of this cytokine are higher in the CSF of patients with HAD compared with HIV‐infected patients without HAD (Rho et al., 1995; Krivine et al., 1999; Perrella et al., 2001). Moreover, the IFN‐α level in the CSF correlates with viral titres (Krivine et al., 1999), cerebral atrophy (Perrella et al., 2001) and severity of dementia (Rho et al., 1995), suggesting that IFN‐α may have primary involvement in the pathogenesis of HAD.

In summary, the chronic presence of IFN‐I in the CNS is a characteristic finding in several neuroinflammatory diseases such as AGS, Cree encephalitis, IGBC, SLE encephalopathy and congenital and chronic viral encephalopathies. Despite their distinct aetiologies, these diseases may all be considered as ‘type I interferonopathies’.

IL‐6 as a causal factor in human CNS disease

Similar to IL‐6 in peripheral tissues, local production of IL‐6 in the CNS can come from a number of different cell types including infiltrating leukocytes and cells intrinsic to the CNS such as astrocytes and microglia and can exert wide‐ranging actions. This subject has been the focus of some excellent detailed reviews (Spooren et al., 2011; Erta et al., 2012) and here we intend to comment only on recent work in which IL‐6 is linked as a direct causal factor for human neurological disease.

NMO (Devic disease; see Barnett and Sutton, 2012; Uzawa et al., 2014b) is a rare but debilitating autoimmune disease of the CNS characterized by the presence of optic neuritis and extensive inflammatory lesions in the spinal cord resulting in astrocyte degeneration and demyelination. NMO can be distinguished from MS based on a number of features including pathology, neuroimaging, immunology and responses to immunotherapies. The presence of disease‐specific autoantibodies that target the aquaporin‐4 (AQP4) water channel in more than 80% of patients with NMO is a defining feature of this disease (Lennon et al., 2004; 2005). Breakdown of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) in NMO permits anti‐AQP antibodies to access the CNS and bind to astrocytes that then degenerate via a complement‐mediated process (Takano et al., 2010; Uzawa et al., 2010). In addition, other immunopathogenic pathways have been identified that are implicated in the pathogenesis of NMO such as T‐cell‐mediated immunity, principally involving Th17 cells (Linhares et al., 2013).

In NMO, a number of Th2‐ and Th17‐related cytokines and chemokines are elevated in the CSF (Uzawa et al., 2010; 2014a). Among these, IL‐6 is dominant in >80% of NMO patients and has a strong correlation with a number of disease parameters, such as clinical severity, CSF glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and cell counts (Uzawa et al., 2013; 2014a). In the relapse phase of NMO, the CSF/serum ratio of IL‐6 is markedly higher in these patients suggesting that IL‐6 is produced locally in the CSF and/or brain (Uzawa et al., 2010). The identity of the cells responsible for the production of IL‐6 and what drives its production in the CNS of NMO patients is unknown. Notably, in the inflammatory spinal cord disease, idiopathic transverse myelitis (ITM; see below), astrocytes in and around the area of inflammation within the spinal cord are the predominant source of IL‐6 (Kaplin et al., 2005). Given the similar spinal cord pathology found in NMO and ITM, it is reasonable to speculate that astrocytes may also produce IL‐6 in NMO but this needs to be resolved.

The specific B‐cells responsible for the production of the anti‐AQP4 antibodies in NMO have the phenotypic characteristics of plasmablasts (Chihara et al., 2011). The survival of these plasmablasts and the production of anti‐AQP4 antibody by these cells are enhanced by IL‐6 (Chihara et al., 2011). The central role of IL‐6 in driving this key B‐cell population in NMO has provided the rationale for therapeutic targeting of IL‐6. To this end, a number of recent case reports demonstrate the efficacy of tocilizumab therapy in patients with fulminant NMO (Araki et al., 2013; Ayzenberg et al., 2013; Kieseier et al., 2013; Lauenstein et al., 2014). Tocilizumab is a neutralizing monoclonal antibody directed against the human IL‐6R that has proven successful in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, Castleman disease and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Tanaka and Kishimoto, 2012). In a more recent clinical study to evaluate safety and efficacy, in seven NMO patients treated with tocilizumab, the annualized relapse rate, the Expanded Disability Status Scale score, neuropathic pain and general fatigue all declined significantly while CSF anti‐AQP4 antibody titres also decreased significantly (Araki et al., 2014). These studies highlight not only the effectiveness of IL‐6R targeted blockade as a promising therapeutic option for NMO but also provide further support for IL‐6 as a key factor driving the pathogenesis of NMO.

The immune‐mediated disorder ITM is associated with inflammation, demyelination and axonal damage in the spinal cord. Among the immune alterations present in ITM, IL‐6 levels are selectively and markedly elevated in the CSF and correlate directly with markers of tissue injury and sustained clinical disability (Kaplin et al., 2005). CSF from patients with ITM when added to spinal cord organotypic cultures can induce the death of spinal cord cells, an effect that is prevented by the immunodepletion of IL‐6 from the CSF. As noted earlier, astrocytes are the predominant source of IL‐6 in ITM. The mechanism for the IL‐6‐mediated cytotoxicity involves excessive NO production and activation of PARP as many of the adverse spinal cord effects of IL‐6 can be reversed by either NO or PARP inhibitors. These findings, together with animal studies discussed below, demonstrate a central role for IL‐6 in causing ITM and identify IL‐6 as a potential therapeutic target for the management of this disorder.

In contrast to autoimmune diseases such as NMO, autoinflammatory diseases are characterized by apparently unprovoked inflammation without pathogenic autoantibodies or autoreactive T‐cells. Specific mutations that result in constitutive activation of the IL‐1 pathway genes underlie many cases of autoinflammatory disease (Conforti‐Andreoni et al., 2011). Although in general the inflammatory lesions affect many organs, neurological manifestations can also occur such as in chronic infantile neurologic cutaneous articular syndrome and Muckle–Wells syndrome (Conforti‐Andreoni et al., 2011). Recently, a case of chronic inflammatory disease was identified in a patient with primary neurological involvement that may represent a novel autoinflammatory disease caused by the overproduction of IL‐6 in the CNS (Salsano et al., 2013). This patient exhibited chronic disease characterized by aseptic meningitis, progressive hearing loss, persistently raised inflammatory markers and diffuse leukoencephalopathy. Although the patient was found to not have elevated IL‐1 in their serum or CSF, CSF IL‐6 was grossly elevated compared with the serum level indicative of IL‐6 being largely produced by cells within the CNS. Although the basis for the hyperproduction of IL‐6 in the CNS of this patient was not identified, the findings suggest a pathogenetic role for IL‐6. Consequent tocilizumab therapy in this patient produced a normalization of blood inflammatory markers and partial improvement in disease symptoms; however, although reduced, abnormal CSF parameters persisted. The latter finding may reflect the poor permeability of the BBB to tocilizumab, restricting its uptake and availability and therefore efficacy, in the brain and CSF.

Animal models provide direct evidence for IFN‐α and IL‐6 as mediators of CNS disease

Genetically engineered mice with gain‐of‐function mutations offer a valuable experimental approach for developing models of human disease linked to the chronic overproduction of cytokines. They have provided persuasive support for the central role of cytokines as causative effectors in neurological disease and have advanced our knowledge of the molecular and cellular processes that underlie cytokine‐mediated disease in the CNS (Campbell et al., 2010). This point is well illustrated in the case of transgenic mice with CNS‐restricted, astrocyte‐targeted production of murine IFN‐α [transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of IFN‐α (GFAP‐IFNα) mice] (Akwa et al., 1998) or murine IL‐6 [transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of IL6 (GFAP‐IL6) mice] (Campbell et al., 1993). As noted earlier, the astrocyte is a predominant source of IFN‐α and IL‐6 in AGS and ITM, respectively, so the targeting of these cells is a relevant strategy for understanding the neuropathophysiological role of these cytokines.

The GFAP‐IFNα mice produce IFN‐α at a level in the CNS that is similar to that found in the CNS of mice with herpes simplex virus or murine hepatitis virus (Campbell et al., 1999) infection. GFAP‐IFNα mice develop a transgene (i.e. IFN‐α) dose‐dependent, progressive inflammatory encephalopathy (Akwa et al., 1998; Campbell et al., 1999) that is most pronounced in the thalamus, cerebellum and brain stem areas in which the transgene is expressed predominantly (Akwa et al., 1998). Higher expressor GFAP‐IFNα mice develop weight loss, inactivity, ataxia and eventually convulsions leading to early death. Histologically, calcification is prominent in the thalamus, hippocampus and cerebellum and found in association with marked neurodegeneration (Akwa et al., 1998; Campbell et al., 1999) and inflammatory changes with infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cells and B‐cells, significant microgliosis and astrocytosis and vasculopathy. In parallel with these neurodegenerative changes, the hippocampus of GFAP‐IFNα mice exhibits abnormal hyperexcitability and decreased synaptic plasticity and the mice display a moderate learning deficit (Campbell et al., 1999). These observations offer definitive proof that the chronic production of IFN‐α in the brain is detrimental, producing progressive, severe, molecular, structural and functional injury. Importantly, there is considerable overlap in the cellular and clinical phenotype between GFAP‐IFNα mice and that found in AGS and other type I interferonopathies (Figure 1) reinforcing the notion of a primary role for IFN‐α in the pathogenesis of this and other related human disorders.

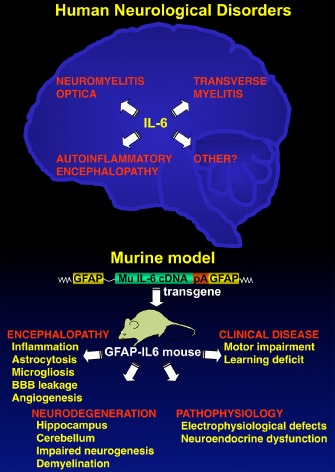

A similar transgenic approach employing a GFAP expression vector was used to generate a mouse model for astrocyte‐targeted production of murine IL‐6 in the CNS of mice (Campbell et al., 1993). In GFAP‐IL6 mice, the IL‐6 transgene expression is localized to astrocytes predominantly in subcortical regions such as the thalamus, the cerebellum and the brain stem. However, IL‐6 transgene expression is not found in the spinal cord that is largely unaffected by the actions of IL‐6 or development of disease in this model (Quintana et al., 2009). This is clearly a limitation of the model for studying the role of IL‐6 in neurological disorders with primary spinal cord involvement such as NMO. GFAP‐IL6 mice develop a range of neurobehavioral, neuroendocrine and neurophysiological deficits that correlate with the transgene dose and age. These deficits include development of ataxia (Campbell et al., 1993), a progressive decline in learning function (Heyser et al., 1997) and altered hypothalamic‐pituitary adrenal function (Raber et al., 1997). GFAP‐IL6 mice have increased seizure susceptibility (Samland et al., 2003), which correlates with abnormal hippocampal excitatory pathophysiology and the loss of inhibitory control (Steffensen et al., 1994). Enhanced synaptic transmission has also been observed in hippocampal slices from GFAP‐IL6 mice (Nelson et al., 2012) together with reduced long‐term potentiation in the dentate gyrus (Bellinger et al., 1995). The altered hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the GFAP‐IL6 mice is likely to be due to neurodegenerative changes that include dendritic vacuolization, stripping of dendritic spines, decreased synaptic density and significantly decreased numbers of inhibitory interneurons (Campbell et al., 1993; Heyser et al., 1997). Marked neurodegeneration also occurs in the cerebellum of these mice with progressive atrophy and loss of molecular and granular layer neurons, spongiosis and extensive demyelination (Campbell et al., 1993). These degenerative changes in the cerebellum underlie the ataxia that occurs in older GFAP‐IL6 mice. Finally, with increasing age, astrocytes are damaged, become vacuolated and degenerate (Brett et al., 1995). Astrocyte degeneration in this model may add further to the demise of neurons by compromising the essential support functions for neurons provided by these cells.

Astrocytes, microglia and endothelial cells but not neurons are the predominant IL‐6 responder cells in the GFAP‐IL6 mice (Sanz et al., 2007). It is unclear why neurons show little or no apparent response to IL‐6 in this model with the implication being that the neuronal injury and death observed in these mice is secondary to other perturbations. Such perturbations include marked activation and proliferation of astrocytes and microglia (Campbell et al., 1993; Chiang et al., 1994). Microglial cell activation associates closely with the degree of neurodegeneration and learning impairment in the GFAP‐IL6 mice and impaired hippocampal neurogenesis (Heyser et al., 1997; Vallieres et al., 2002). How microgliosis might contribute to the development of neurodegeneration in these mice remains unclear but conceivably might involve production of various inflammatory molecules that mediate neuronal injury. Consistent with this, the expression of a number of inflammation‐related factors is increased in the brain of the GFAP‐IL6 mice and includes the up‐regulation of genes for the acute phase response factors α1‐antichymotrypsin, complement C3 and metallothionein I + II and the expression of other cytokine and chemokine genes including those for CXCL10, CCL5, IL‐1α, IL‐1β and TNF‐α (Campbell et al., 1993; Barnum et al., 1996; Carrasco et al., 1998; Quintana et al., 2009). Marked changes also occur in the cerebrovascular compartment in the GFAP‐IL6 mice with progressive proliferative angiopathy in the cerebellum and breakdown of the BBB (Campbell et al., 1993; Brett et al., 1995). Reflective of the chronic inflammatory state in the GFAP‐IL6 brain, vessel dilation and increased expression of vascular adhesion molecules and von Willebrand factor are also found (Campbell et al., 1993; Milner and Campbell, 2006).

In addition to the direct local actions of IL‐6, macrophages, B‐cells and CD4+ T‐cells are recruited and progressively accumulate in the cerebellum of GFAP‐IL6 mice (Campbell et al., 1993; Quintana et al., 2009). Currently, it is not known whether these immune cells contribute to degenerative encephalopathy. However, the presence of these cells suggests that IL‐6 induces a permissive environment in the brain for the attraction of leukocytes. Indeed, induction of experimental autoimmune encephalitis in the GFAP‐IL6 mice causes grossly enhanced cerebellar immune pathology and tissue damage while spinal cord immune lesions are dramatically reduced in size and number (Quintana et al., 2009). These studies show that the local tissue production of IL‐6 can prime the CNS dramatically enhancing inflammatory responses in the brain.

The contribution of trans‐signalling to the actions of IL‐6 in the brain of the GFAP‐IL6 mice was examined by generating GFAP‐IL6 × GFAP‐sgp130Fc bigenic mice (Campbell et al., 2014). Preventing trans‐signalling in the brain of the GFAP‐IL6 mice with sgp130Fc significantly attenuated the expression of the Serpina3n but not Socs3 gene while angiogenesis, BBB leakage and gliosis were also decreased significantly. Impaired neurogenesis seen in GFAP‐IL6 mice was rescued in GFAP‐IL6/sgp130Fc mice. Finally, neurodegenerative changes in the cerebellum of the GFAP‐IL6 mice were significantly ameliorated in GFAP‐IL6/sgp130Fc mice when trans‐signalling was prevented. These findings show that in the CNS, trans‐signalling mediates IL‐6 cellular communication with selective cellular and molecular targets and importantly is the predominant pathway via which IL‐6 exerts many of its detrimental actions. The results of this study also complement those showing that preventing trans‐signalling accelerates the recovery of mice from LPS‐induced sickness behaviour and decreases the hyperactive response of microglia to LPS in aged mice highlighting a role for IL‐6 trans‐signalling in these processes (Burton et al., 2011; 2013). Therefore, the therapeutic targeting of IL‐6 trans‐signalling may be of benefit for the treatment of neuroinflammatory diseases such as NMO.

As noted earlier, one limitation of the GFAP‐IL6 mouse model is the absence of transgene‐encoded IL‐6 production in the spinal cord, preventing the investigation of the ability of IL‐6 to mediate inflammatory myelopathy. An alternative approach has been employed using minipumps to deliver IL‐6 chronically to the spinal subarachnoid space of rats (Kaplin et al., 2005). These animals developed progressive weakness and spinal cord inflammation, demyelination and axonal damage that were blocked by inhibitors of PARP or inducible NOS. These findings are congruent with those observed in the spinal cord of patients with ITM discussed earlier. Interestingly, infusion of IL‐6 into the cerebral ventricles of rats was without apparent effect indicating that the spinal cord may be more vulnerable to the pathological actions of IL‐6.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Although IFN‐α and IL‐6 have a central role in innate defence against infection and injury, the powerful and pleiotropic actions of these cytokines dictate that there must be tight regulation of the production and action of these cytokines to minimize the potential for bystander injury to the host. Nevertheless, and as discussed here, dysregulation of IFN‐α or IL‐6 production occurs in the brain in a variety of neurological disorders such as in AGS or the autoimmune disorder NMO respectively. The view that these cytokines are primary to the pathogenesis of these neurological disorders is convincingly backed by experimental studies using genetically engineered mice in which chronic, cerebral production of IFN‐α (Figure 1) or IL‐6 (Figure 2) was targeted to the CNS. The range of molecular, cellular and functional neurological changes found in these two distinct transgenic models, while differing markedly from each other, show marked correspondence with those found in human neurological diseases in which these cytokines are implicated.

Figure 2.

IL‐6 as a causal factor in human neurological disease replicated in transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of IL‐6. Accumulating evidence reveals IL‐6 to be a key pathogenetic factor in a number of human neurological disorders including neuromyelitis optica, idiopathic transverse myelitis and autoinflammatory encephalopathy. It is likely that there will be other neurological conditions in which a role for IL‐6 is indicated. Formal experimental evidence of IL‐6 as a direct mediator of neurological disease has come from transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted production of murine IL‐6 in the brain. These GFAP‐IL6 mice develop a spectrum of progressive molecular and cellular alterations giving rise to abnormal electrophysiological and neuroendocrine function, as well as learning impairment and motor disease.

Clearly, attaining a greater understanding of the molecular and cellular basis of IFN‐α and IL‐6 actions in the CNS may have important clinical ramifications from understanding basic disease mechanisms to interventional therapies that target these cytokines. Indeed, the recent encouraging results obtained in clinical trials with tocilizumab therapy in NMO provide the impetus for moving forward, where indicated, with the application of anti‐cytokine directed therapies in human neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. In addition to the anti‐IL6R monoclonal antibody tocilizumab, several anti‐IL6 therapeutic monoclonal antibodies have been developed and used or are currently in testing in various clinical trials for peripheral inflammatory disorders and cancer (Rath et al., 2015; Rossi et al., 2015). Apart from targeting IL‐6 or the IL‐6R directly with monoclonal antibodies, new drugs that target downstream of the IL‐6R are also emerging. Of particular interest in light of recent experimental findings highlighting the importance of trans‐signalling in mediating many of the adverse effects of IL‐6 in the CNS (Burton et al., 2011; Campbell et al., 2014) is the fusion protein sgp130‐Fc which is currently undergoing evaluation in phase I clinical trials (Calabrese and Rose‐John, 2014). As with IL‐6, several IFN‐I‐blocking strategies including monoclonal antibodies to IFN‐α or IFNAR as well as active immunization against IFN‐α with IFN‐α kinoid have been developed that have shown efficacy in phase I/II clinical trials to reduce IFN levels in patients without major adverse effects (Kirou and Gkrouzman, 2013; Lauwerys et al., 2014). The developing extensive clinical experience gained from various clinical trials targeting IFN actions bodes well for the eventual application of these therapies to the treatment of neurological disorders such as AGS. Ultimately, time will tell as to how effective these, as well as the anti‐IL6 targeted drugs, will be.

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Claire Thompson for helpful discussions on this manuscript. Research in I. L. C.'s laboratory is financially supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Research in M. J. H.'s laboratory was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Hofer, M. J. , and Campbell, I. L. (2016) Immunoinflammatory diseases of the central nervous system – the tale of two cytokines. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 716–728. doi: 10.1111/bph.13175.

References

- Aicardi J (2002). Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome: special type early‐onset encephalopathy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 6 (Suppl. A): A1–A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicardi J, Goutieres F (1984). A progressive familial encephalopathy in infancy with calcifications of the basal ganglia and chronic cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis. Ann Neurol 15: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akahoshi M, Nakashima H, Sadanaga A, Miyake K, Obara K, Tamari M et al (2008). Promoter polymorphisms in the IRF3 gene confer protection against systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 17: 568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akwa Y, Hassett DE, Eloranta ML, Sandberg K, Masliah E, Powell H et al (1998). Transgenic expression of IFN‐a in the central nervous system of mice protects against lethal neurotropic viral infection but induces inflammation and neurodegeneration. J Immunol 161: 5016–5026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Catalytic Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1676–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1797–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA et al (2013c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ion Channels. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1607–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki M, Aranami T, Matsuoka T, Nakamura M, Miyake S, Yamamura T (2013). Clinical improvement in a patient with neuromyelitis optica following therapy with the anti‐IL‐6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab. Mod Rheumatol 23: 827–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki M, Matsuoka T, Miyamoto K, Kusunoki S, Okamoto T, Murata M et al (2014). Efficacy of the anti‐IL‐6 receptor antibody tocilizumab in neuromyelitis optica: a pilot study. Neurology 82: 1302–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayzenberg I, Kleiter I, Schroder A, Hellwig K, Chan A, Yamamura T et al (2013). Interleukin 6 receptor blockade in patients with neuromyelitis optica nonresponsive to anti‐CD20 therapy. JAMA Neurol 70: 394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MH, Sutton I (2012). Neuromyelitis optica: not a multiple sclerosis variant. Curr Opin Neurol 25: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum SR, Jones JL, Muller‐Ladner U, Samimi A, Campbell IL (1996). Chronic complement C3 gene expression in the CNS of transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted interleukin‐6 expression. Glia 18: 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger FP, Madamba SG, Campbell IL, Siggins G (1995). Reduced long‐term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of transgenic mice with cerebral overexpression of interleukin‐6. Neurosci Letts 198: 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belman AL, Lantos G, Horoupian D, Novick BE, Ultmann MH, Dickson DW et al (1986). Calcification of the basal ganglia in infants and children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Neurology 36: 1192–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DN, Booth F, Watters GV, Andermann E, Dumont C, Halliday WC et al (1988a). Leukoencephalopathy among native Indian infants in northern Quebec and Manitoba. Ann Neurol 24: 490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DN, Watters GV, Andermann E, Dumont C, Kabay ME, Kaplan P et al (1988b). Encephalitis among Cree children in Northern Quebec. Ann Neurol 24: 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P, Palucka AK, Gill M, Pascual V, Banchereau J (2001). Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN‐alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science 294: 1540–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogunovic D, Byun M, Durfee LA, Abhyankar A, Sanal O, Mansouri D et al (2012). Mycobacterial disease and impaired IFN‐gamma immunity in humans with inherited ISG15 deficiency. Science 337: 1684–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boxel‐Dezaire AH, Rani MR, Stark GR (2006). Complex modulation of cell type‐specific signaling in response to type I interferons. Immunity 25: 361–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett FM, Mizisin AP, Powell HC, Campbell IL (1995). Evolution of neuropathologic abnormalities associated with blood‐brain barrier breakdown in transgenic mice expressing interleukin‐6 in astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 54: 766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers P, Wolters P, Civitello L (1998). Central nervous system manifestations and assessment In: Pizzo P, Wilfert CM. (eds). Pediatric AIDS: The Challenge of HIV Infection in Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 3rd edn Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Burton MD, Sparkman NL, Johnson RW (2011). Inhibition of interleukin‐6 trans‐signaling in the brain facilitates recovery from lipopolysaccharide‐induced sickness behavior. J Neuroinflammation 8: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MD, Rytych JL, Freund GG, Johnson RW (2013). Central inhibition of interleukin‐6 trans‐signaling during peripheral infection reduced neuroinflammation and sickness in aged mice. Brain Behav Immun 30: 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese LH, Rose‐John S (2014). IL‐6 biology: implications for clinical targeting in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 10: 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Abraham CR, Masliah E, Kemper P, Inglis JD, Oldstone MBA et al (1993). Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by the cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 10061–10065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Krucker T, Steffensen S, Akwa Y, Powell HC, Lane T et al (1999). Structural and functional neuropathology in transgenic mice with CNS expression of IFN‐a. Brain Res 835: 46–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Hofer MJ, Pagenstecher A (2010). Transgenic models for cytokine‐induced neurological disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 903–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Erta M, Lim SL, Frausto R, May U, Rose‐John S et al (2014). Trans‐signaling is a dominant mechanism for the pathogenic actions of interleukin‐6 in the brain. J Neurosci 34: 2503–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco J, Hernandez J, Campbell IL, Hidalgo J (1998). Localization of metallothionein‐I and‐III expression in the CNS of transgenic mice with astrocyte‐targeted expression of interleukin‐6. Exp Neurol 153: 184–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahwan C, Chahwan R (2012). Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome: from patients to genes and beyond. Clin Genet 81: 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C‐S, Stalder A, Samimi A, Campbell IL (1994). Reactive gliosis as a consequence of interleukin‐6 expression in the brain. Studies in transgenic mice. Dev Neurosci 16: 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chihara N, Aranami T, Sato W, Miyazaki Y, Miyake S, Okamoto T et al (2011). Interleukin 6 signaling promotes anti‐aquaporin 4 autoantibody production from plasmablasts in neuromyelitis optica. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 3701–3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civitello L (2005). Neurologic problems In: Zeichner S, Read J. (eds). Textbook of Pediatric HIV Care. Cambridge University Press: New York, pp. 431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti‐Andreoni C, Ricciardi‐Castagnoli P, Mortellaro A (2011). The inflammasomes in health and disease: from genetics to molecular mechanisms of autoinflammation and beyond. Cell Mol Immunol 8: 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Dasgupta S, Middaugh LD, Terry EC, Gorry PR, Wesselingh SL et al (2005). Highly active antiretroviral therapy and human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Ann Neurol 57: 795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ (2011). Type I interferonopathies: a novel set of inborn errors of immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1238: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Livingston JH (2008). Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome: an important Mendelian mimic of congenital infection. Dev Med Child Neurol 50: 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Jackson AP, Roberts E, van Beusekom E, Barth P, Corry P et al (2000). Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome displays genetic heterogeneity with one locus (AGS1) on chromosome 3p21. Am J Hum Genet 67: 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Black DN, Ali M, Bond J, Jackson AP, Lefson M et al (2003). Cree encephalitis is allelic with Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome: implications for the pathogenesis of disorders of interferon alpha metabolism. J Med Genet 40: 183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Hayward BE, Parmar R, Robins P, Leitch A, Ali M et al (2006a). Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′‐5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome at the AGS1 locus. Nat Genet 38: 917–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow YJ, Leitch A, Hayward BE, Garner A, Parmar R, Griffith E et al (2006b). Mutations in genes encoding ribonuclease H2 subunits cause Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome and mimic congenital viral brain infection. Nat Genet 38: 910–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Laet C, Goyens P, Christophe C, Ferster A, Mascart F, Dan B (2005). Phenotypic overlap between infantile systemic lupus erythematosus and Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome. Neuropediatrics 36: 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Tsao BP (2010). Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6: 683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussaix E, Lebon P, Ponsot G, Huault G, Tardieu M (1985). Intrathecal synthesis of different alpha‐interferons in patients with various neurological diseases. Acta Neurol Scand 7: 504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder PS, Walder JA (1991). Ribonuclease H from K562 human erythroleukemia cells. Purification, characterization, and substrate specificity. J Biol Chem 266: 6472–6479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efthimiou P, Blanco M (2009). Pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus and potential biomarkers. Mod Rheumatol 19: 457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Jenkins BJ (2004). Acquiring signalling specificity from the cytokine receptor gp130. Trends Genet 20: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erta M, Quintana A, Hidalgo J (2012). Interleukin‐6, a major cytokine in the central nervous system. Int J Biol Sci 8: 1254–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Zhao J, Qian X, Wong JL, Kaufman KM, Yu CY et al (2011). Association of a functional IRF7 variant with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 63: 749–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki M, Kato H, Miyachi Y, Toki H, Motegi H, Inoue M et al (2014). Autoimmune disorders associated with gain of function of the intracellular sensor MDA5. Immunity 40: 199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone DC, Ennis‐Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HC, Rice GI, Christodoulou E et al (2011). HIV‐1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 480: 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez‐Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E (2012). Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray F, Scaravilli F, Everall I, Chretien F, An S, Boche D et al (1996). Neuropathology of early HIV‐1 infection. Brain Pathol 6: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner JC, Schmittwolf C, Kispert A, Muller AM, Higuchi M, Seeburg PH (2004). Liver disintegration in the mouse embryo caused by deficiency in the RNA‐editing enzyme ADAR1. J Biol Chem 279: 4894–4902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner JC, Walkley CR, Lu J, Orkin SH (2009). ADAR1 is essential for the maintenance of hematopoiesis and suppression of interferon signaling. Nat Immunol 10: 109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heteren JT, Rozenberg F, Aronica E, Troost D, Lebon P, Kuijpers TW (2008). Astrocytes produce interferon‐alpha and CXCL10, but not IL‐6 or CXCL8, in Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome. Glia 56: 568–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Masliah E, Samimi A, Campbell IL, Gold LH (1997). Progressive decline in avoidance learning paralleled by inflammatory neurodegeneration in transgenic mice expressing interleukin 6 in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1500–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Taga T, Nakano N, Yasukawa K, Kashiwamura S, Shimizu K et al (1985). Purification to homogeneity and characterization of human B‐cell differentiation factor (BCDF or BSFp‐2). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82: 5490–5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Yasukawa K, Harada H, Tage T, Watanabe Y, Matsuda T et al (1986). Complementary DNA for a novel human interleukin (BSF‐2) that induces B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin. Nature 324: 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Akira S, Taga T, Kishimoto T (1990). Biological and clinical aspects of interleukin 6. Immunol Today 11: 443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MJ, Campbell IL (2013). Type I interferon in neurological disease‐the devil from within. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 24: 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs A, Lindenmann J (1957). Virus interference. 1. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B 147: 258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa A, Murayama T, Sakuma N, Takase A, Shishido T, Nagamatsu K et al (1982). Computed cranial tomography in congenital rubella syndrome. Arch Neurol 39: 420–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzotti A, Pulliero A, Orcesi S, Cartiglia C, Longobardi MG, Capra V et al (2009). Interferon‐related transcriptome alterations in the cerebrospinal fluid cells of Aicardi‐Goutieres patients. Brain Pathol 19: 650–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Lee SC, Brosnan CF (2003). Cytokines: powerful regulators of glial cell activation. Neuroscientist 9: 10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsen A, Bengtsson AA, Nived O, Ryberg B, Truedsson L, Ronnblom L et al (2003). The heterogeneity of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus is reflected in lack of association with cerebrospinal fluid cytokine profiles. Lupus 12: 846–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostock T, Mullberg J, Ozbek S, Atreya R, Blinn G, Voltz N et al (2001). Soluble gp130 is the natural inhibitor of soluble interleukin‐6 receptor transsignaling responses. Eur J Biochem 268: 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplin AI, Deshpande DM, Scott E, Krishnan C, Carmen JS, Shats I et al (2005). IL‐6 induces regionally selective spinal cord injury in patients with the neuroinflammatory disorder transverse myelitis. J Clin Invest 115: 2731–2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman WM, Sivit CJ, Fitz CR, Rakusan A, Herzog K, Chandra RS (1992). CT and MR evaluation of intracranial involvement in pediatric HIV infection: a clinical imaging correlation. Am J Neuroradiol 13: 949–957. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ (2007). Review and meta‐analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol 17: 253–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieseier BC, Stuve O, Dehmel T, Goebels N, Leussink VI, Mausberg AK et al (2013). Disease amelioration with tocilizumab in a treatment‐resistant patient with neuromyelitis optica: implication for cellular immune responses. JAMA Neurol 70: 390–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirou KA, Gkrouzman E (2013). Anti‐interferon alpha treatment in SLE. Clin Immunol 148: 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T (2005). Interleukin‐6: from basic science to medicine – 40 years in immunology. Annu Rev Immunol 23: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivine A, Force G, Servan J, Cabee A‐E, Rozenberg F, Dighiero L et al (1999). Measuring HIV‐1 RNA and interferon‐a in the cerebrospinal fluid of AIDS patients: insights into the pathogenesis of AIDS Dementia Complex. J Neurovirol 5: 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauenstein AS, Stettner M, Kieseier BC, Lensch E (2014). Treating neuromyelitis optica with the interleukin‐6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab. BMJ Case Rep 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr‐2013‐202939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauwerys BR, Ducreux J, Houssiau FA (2014). Type I interferon blockade in systemic lupus erythematosus: where do we stand? Rheumatology (Oxford) 53: 1369–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebon P, Badoual J, Ponsot G, Goutieres F, Hemeury‐Cukier F, Aicardi J (1988). Intrathecal synthesis of interferon‐alpha in infants with progressive familial encephalopathy. J Neurol Sci 84: 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebon P, Meritet JF, Krivine A, Rozenberg F (2002). Interferon and Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 6 (Suppl. A): A47–A53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Fujihara K et al (2004). A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet 364: 2106–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Verkman AS, Hinson SR (2005). IgG marker of optic‐spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin‐4 water channel. J Exp Med 202: 473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HW, Levison SW (2009). Context‐dependent IL‐6 potentiation of interferon‐gamma‐induced IL‐12 secretion and CD40 expression in murine microglia. J Neurochem 111: 808–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liner KJ 2nd, Ro MJ, Robertson KR (2010). HIV, antiretroviral therapies, and the brain. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 7: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhares UC, Schiavoni PB, Barros PO, Kasahara TM, Teixeira B, Ferreira TB et al (2013). The ex vivo production of IL‐6 and IL‐21 by CD4+ T cells is directly associated with neurological disability in neuromyelitis optica patients. J Clin Immunol 33: 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, Cox S, Brindle J, Read D et al (2014). The RNA‐editing enzyme ADAR1 controls innate immune responses to RNA. Cell Rep 9: 1482–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz P, Herget T, Lang E, Otten U, Rose‐John S (1997). Activation of gp130 by IL‐6/soluble IL‐6 receptor induces neuronal differentiation. Eur J Neurosci 9: 2765–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz P, Heese K, Dimitriades‐Schmutz B, Rose‐John S, Otten U (1999). Role of interleukin‐6 and soluble IL‐6 receptor in region‐specific induction of astrocytic differentiation and neurotrophin expression. Glia 26: 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner R, Campbell IL (2006). Increased expression of the beta4 and alpha5 integrin subunits in cerebral blood vessels of transgenic mice chronically producing the pro‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐6 or IFN‐alpha in the central nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci 33: 429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CD (2006). HIV‐1 encephalopathy among perinatally infected children: neuropathogenesis and response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 12: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita M, Stamp G, Robins P, Dulic A, Rosewell I, Hrivnak G et al (2004). Gene‐targeted mice lacking the Trex1 (DNase III) 3′→5′ DNA exonuclease develop inflammatory myocarditis. Mol Cell Biol 24: 6719–6727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TE, Olde Engberink A, Hernandez R, Puro A, Huitron‐Resendiz S, Hao C et al (2012). Altered synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of transgenic mice with enhanced central nervous systems expression of interleukin‐6. Brain Behav Immun 26: 959–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorbehesht B, Enzmann DR, Sullender W, Bradley JS, Arvin AM (1987). Neonatal herpes simplex encephalitis: correlation of clinical and CT findings. Radiology 162: 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda H, Nakagawa K, Abe J, Awaya T, Funabiki M, Hijikata A et al (2014). Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome is caused by IFIH1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet 95: 121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual V, Banchereau J, Palucka AK (2003). The central role of dendritic cells and interferon‐alpha in SLE. Curr Opin Rheumatol 15: 548–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Ricour C, Sommereyns C, Sorgeloos F, Michiels T (2007). Type I interferon response in the central nervous system. Biochimie 89: 770–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al; NC‐IUPHAR (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res 42 (Database Issue): D1098–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrella O, Carreiri PB, Perrella A, Sbreglia C, Gorga F, Guarnaccia D et al (2001). Transforming growth factor beta‐1 and interferon‐alpha in the AIDS dementia complex (ADC): possible relationship with cerebral viral load? Eur Cytokine Netw 12: 51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petito CK, Adkins B, McCarthy M, Roberts B, Khamis I (2003). CD4+ and CD8+ cells accumulate in the brains of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients with human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Neurovirol 9: 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontrelli L, Pavlakis S, Krilov LR (1999). Neurobehavioral manifestations and sequelae of HIV and other infections. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 8: 869–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana A, Muller M, Frausto RF, Ramos R, Getts DR, Sanz E et al (2009). Site‐specific production of IL‐6 in the central nervous system retargets and enhances the inflammatory response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 183: 2079–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raber J, O'Shea RD, Bloom FE, Campbell IL (1997). Modulation of hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal function by transgenic expression of interleukin‐6 in the CNS of mice. J Neurosci 17: 9473–9480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath T, Billmeier U, Waldner MJ, Atreya R, Neurath MF (2015). From physiology to disease and targeted therapy: interleukin‐6 in inflammation and inflammation‐associated carcinogenesis. Arch Toxicol 89: 541–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft JC, Suri M, Rice GI, Szynkiewicz M, Crow YJ (2011). Autosomal dominant inheritance of a heterozygous mutation in SAMHD1 causing familial chilblain lupus. Am J Med Genet A 155A: 235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehwinkel J, Maelfait J, Bridgeman A, Rigby R, Hayward B, Liberatore RA et al (2013). SAMHD1‐dependent retroviral control and escape in mice. EMBO J 32: 2454–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho MB, Wesselingh S, Glass JD, McArthur JC, Choi S, Griffin J et al (1995). A potential role for interferon‐a in the pathogenesis of HIV‐associated dementia. Brain Behav Immun 9: 366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice G, Patrick T, Parmar R, Taylor CF, Aeby A, Aicardi J et al (2007). Clinical and molecular phenotype of Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 81: 713–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, Brunette RL, Manfield IW, Carr IM et al (2009). Mutations involved in Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet 41: 829–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Kasher PR, Forte GM, Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Szynkiewicz M et al (2012). Mutations in ADAR1 cause Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome associated with a type I interferon signature. Nat Genet 44: 1243–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice GI, Del Toro Duany Y, Jenkinson EM, Forte GM, Anderson BH, Ariaudo G et al (2014). Gain‐of‐function mutations in IFIH1 cause a spectrum of human disease phenotypes associated with upregulated type I interferon signaling. Nat Genet 46: 503–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby RE, Leitch A, Jackson AP (2008). Nucleic acid‐mediated inflammatory diseases. Bioessays 30: 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon M (2012). Interleukin‐6: from an inflammatory marker to a target for inflammatory diseases. Trends Immunol 33: 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnblom LE, Alm GV, Oberg KE (1990). Possible induction of systemic lupus erythematosus by interferon‐alpha treatment in a patient with a malignant carcinoid tumour. J Intern Med 227: 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose‐John S, Heinrich PC (1994). Soluble receptors for cytokines and growth factors: generation and biological function. Biochem J 300 (Pt 2): 281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose‐John S, Scheller J, Elson G, Jones SA (2006). Interleukin‐6 biology is coordinated by membrane‐bound and soluble receptors: role in inflammation and cancer. J Leukoc Biol 80: 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi JF, Lu ZY, Jourdan M, Klein B (2015). Interleukin‐6 as a therapeutic target. Clin Cancer Res 21: 1248–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell NJ, Hopkins SJ (1995). Cytokines and the nervous system II: actions and mechanisms of action. Trends Neurosci 18: 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan LA, Cotter RL, Zink WE 2nd, Gendelman HE, Zheng J (2002). Macrophages, chemokines and neuronal injury in HIV‐1‐associated dementia. Cell Mol Biol 48: 137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydberg B, Game J (2002). Excision of misincorporated ribonucleotides in DNA by RNase H (type 2) and FEN‐1 in cell‐free extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 16654–16659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsano E, Rizzo A, Bedini G, Bernard L, Dall'olio V, Volorio S et al (2013). An autoinflammatory neurological disease due to interleukin 6 hypersecretion. J Neuroinflammation 10: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samland H, Huitron‐Resendiz S, Masliah E, Criado J, Henriksen SJ, Campbell IL (2003). Profound increase in sensitivity to glutamatergic‐ but not cholinergic agonist‐induced seizures in transgenic mice with astrocyte production of IL‐6. J Neurosci Res 73: 176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz E, Hofer MJ, Unzeta M, Campbell IL (2007). Minimal role for STAT1 in interleukin‐6 signaling and actions in the murine brain. Glia 56: 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller J, Garbers C, Rose‐John S (2014). Interleukin‐6: from basic biology to selective blockade of pro‐inflammatory activities. Semin Immunol 26: 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo YJ, Hahm B (2010). Type I interferon modulates the battle of host immune system against viruses. Adv Appl Microbiol 73: 83–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shet A (2011). Congenital and perinatal infections: throwing new light with an old TORCH. Indian J Pediatr 78: 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa S, Kuroki Y, Kim M, Hirohata S, Ogino T (1992). Interferon‐a in lupus psychosis. Arthritis Rheum 35: 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Goring HH, Lindroos K, Wiman AC, Sturfelt G et al (2005). Polymorphisms in the tyrosine kinase 2 and interferon regulatory factor 5 genes are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Hum Genet 76: 528–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren A, Kolmus K, Laureys G, Clinckers R, De Keyser J, Haegeman G et al (2011). Interleukin‐6, a mental cytokine. Brain Res Rev 67: 157–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BRG, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD (1998). How cells respond to interferons. Ann Rev Biochem 67: 227–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen SC, Campbell IL, Henriksen SJ (1994). Site‐specific hippocampal pathophysiology due to cerebral overexpression of interleukin‐6 in transgenic mice. Brain Res 652: 149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L (2008). Nuanced roles of cytokines in three major human brain disorders. J Clin Invest 118: 3557–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson JB (2008). Aicardi‐Goutieres syndrome (AGS). Eur J Paediatr Neurol 12: 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, Medzhitov R (2008). Trex1 prevents cell‐intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell 134: 587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taccone A, Gambaro G, Ghiorzi M, Ferrea G, Gianbartolomei G, Rolando S et al (1988). Computed tomography (CT) in children with herpes simplex encephalitis. Pediatr Radiol 19: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano R, Misu T, Takahashi T, Sato S, Fujihara K, Itoyama Y (2010). Astrocytic damage is far more severe than demyelination in NMO: a clinical CSF biomarker study. Neurology 75: 208–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Kishimoto T (2012). Targeting interleukin‐6: all the way to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Int J Biol Sci 8: 1227–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Moraga I, Levin D, Krutzik PO, Podoplelova Y, Trejo A et al (2011). Structural linkage between ligand discrimination and receptor activation by type I interferons. Cell 146: 621–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyor WR, Glass JD, Griffin JW, Becker PS, McArthur JC, Bezman L et al (1992). Cytokine expression in the brain during the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol 31: 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa A, Mori M, Arai K, Sato Y, Hayakawa S, Masuda S et al (2010). Cytokine and chemokine profiles in neuromyelitis optica: significance of interleukin‐6. Mult Scler 16: 1443–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa A, Mori M, Sawai S, Masuda S, Muto M, Uchida T et al (2013). Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin‐6 and glial fibrillary acidic protein levels are increased during initial neuromyelitis optica attacks. Clin Chim Acta 421: 181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa A, Masahiro M, Kuwabara S (2014a). Cytokines and chemokines in neuromyelitis optica: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. Brain Pathol 24: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa A, Mori M, Kuwabara S (2014b). Neuromyelitis optica: concept, immunology and treatment. J Clin Neurosci 21: 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcour V, Sithinamsuwan P, Letendre S, Ances B (2011). Pathogenesis of HIV in the central nervous system. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 8: 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallieres L, Campbell IL, Gage FH, Sawchenko PE (2002). Reduced hippocampal neurogenesis in adult transgenic mice with chronic astrocytic production of interleukin‐6. J Neurosci 22: 486–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner NJ, Oh JW, Repovic P, Benveniste EN (1999). Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) production by astrocytes: autocrine regulation by IL‐6 and the soluble IL‐6 receptor. J Neurosci 19: 5236–5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Miyakoda M, Yang W, Khillan J, Stachura DL, Weiss MJ et al (2004). Stress‐induced apoptosis associated with null mutation of ADAR1 RNA editing deaminase gene. J Biol Chem 279: 4952–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weerd NA, Nguyen T (2012). The interferons and their receptors – distribution and regulation. Immunol Cell Biol 90: 483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Lamm AT, Fire AZ (2011). Competition between ADAR and RNAi pathways for an extensive class of RNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WD, Zhang YJ, Xu K, Zhai Y, Li BZ, Pan HF et al (2012). IRF7, a functional factor associates with systemic lupus erythematosus. Cytokine 58: 317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Wang Q, Howell KL, Lee JT, Cho DS, Murray JM et al (2005). ADAR1 RNA deaminase limits short interfering RNA efficacy in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 280: 3946–3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YG, Lindahl T, Barnes DE (2007). Trex1 exonuclease degrades ssDNA to prevent chronic checkpoint activation and autoimmune disease. Cell 131: 873–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Bogunovic D, Payelle‐Brogard B, Francois‐Newton V, Speer SD, Yuan C et al (2014a). Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon‐alpha/beta over‐amplification and auto‐inflammation. Nature 517: 89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O'Keeffe S et al (2014b). An RNA‐sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 34: 11929–11947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Thylin MR, Persidsky Y, Williams CE, Cotter RL, Zink W et al (2001). HIV‐1 infected immune competent mononuclear phagocytes influence the pathways to neuronal demise. Neurotox Res 3: 461–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]