Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been linked to dementia and chronic neurodegeneration. Described initially in boxers and currently recognized across high contact sports, the association between repeated concussion (mild TBI) and progressive neuropsychiatric abnormalities has recently received widespread attention, and has been termed chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Less well appreciated are cognitive changes associated with neurodegeneration in the brain after isolated spinal cord injury. Also under‐recognized is the role of sustained neuroinflammation after brain or spinal cord trauma, even though this relationship has been known since the 1950s and is supported by more recent preclinical and clinical studies. These pathological mechanisms, manifested by extensive microglial and astroglial activation and appropriately termed chronic traumatic brain inflammation or chronic traumatic inflammatory encephalopathy, may be among the most important causes of post‐traumatic neurodegeneration in terms of prevalence. Importantly, emerging experimental work demonstrates that persistent neuroinflammation can cause progressive neurodegeneration that may be treatable even weeks after traumatic injury.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Inflammation: maladies, models, mechanisms and molecules. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2016.173.issue-4

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- CCI

controlled cortical impact

- CTBI

chronic traumatic brain inflammation

- CTE

chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- CTIE

chronic traumatic inflammatory encephalopathy

- DG

dentate gyrus

- ERPs

event‐related potentials

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Catalytic receptors a |

| IL‐4 receptor α |

| Enzymes b |

| Arginase 1 |

| GPCR c |

| mGlu5 receptor |

| LIGANDS | |

|---|---|

| Aβ, β‐amyloid | IL‐1β |

| CCL2 | TGFβ |

| CCL3 | TNFα |

| CCL21 | |

| CHPG, 2‐chloro‐5‐hydroxyphenylglycine | |

| Ibudilast |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2013a), 2013b, 2013c).

Introduction

Neuroinflammation is a prominent feature of many neurodegenerative diseases (Eikelenboom et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2010), and is increasingly being recognized as an important pathophysiological mechanism underlying chronic neurodegeneration following traumatic brain injury (TBI) or spinal cord injury (SCI). As the primary mediators of the innate immune response in the CNS, microglia play a critical role in neuroinflammation and secondary injury following CNS injury. Their persistent activation towards the M1‐like neurotoxic phenotype may in part explain the progressive neuronal loss observed after CNS trauma.

Recent work, both experimental and clinical, has established that moderate or severe TBI may lead to chronic progressive neurodegeneration. A recent retrospective cohort study has shown that there is an increased risk of dementia after TBI (Gardner et al., 2014). Specifically, it demonstrated the influence of age at injury and injury severity on dementia risk after TBI, revealing that even mild TBI (mTBI) increases dementia risk in those aged ≥65 years. An important outstanding question is which type of dementia results from prior brain trauma? It has long been suggested that a prior history of TBI increases the likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer disease (AD) (Mortimer et al., 1985; 1991; Graves et al., 1990; Plassman et al., 2000). Moreover, consistent with the β‐amyloid (Aβ) hypothesis as a key mechanism of AD, brain trauma increases amyloid precursor protein, presenilins and β‐amyloid converting enzyme 1 in injured axons, and results in the deposition of the β‐amyloid fragment, Aβ1–42, in injured brain (see Johnson et al., 2010). However, more recent epidemiological studies involving much larger patient cohorts do not give much support to such an association between TBI and AD (Dams‐O'Connor et al., 2013; Nordstrom et al., 2014). In addition, recent clinical studies have increasingly called into question the role of Aβ as the major driver of cognitive decline in AD patients (Doody et al., 2014; Salloway et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2015). Rather, there is a significant association with non‐AD dementias (Wang et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Barnes et al., 2014; Nordstrom et al., 2014; Faden and Loane, 2015).

Repeated mTBI, in boxers or athletes who participate in high contact sports, has been linked to later onset neurodegeneration. This chronic neurodegeneration may contribute to a pathologically distinct disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) that has a significant τ pathology including phosphorylated τ in neurofibrillary tangles, neurites and glial deposits (Omalu et al., 2005; McKee et al., 2009; 2013). Some cases of CTE also demonstrate diffuse Aβ plaques and pathological accumulations of phosphorylated forms of the DNA‐binding protein TDP‐43 (McKee et al., 2013). Importantly, single TBI appears to have a different pathology. Acutely, it is associated with diffuse Aβ plaques (Roberts et al., 1991; 1994), whereas fibrillary Aβ plaques can be observed in the chronic phase (Johnson et al., 2012). Moreover, single TBI results in accumulation of phosphorylation‐independent TDP‐43 and a relative absence of pathological phosphorylated TDP‐43 (Johnson et al., 2011), which raises questions about whether the neuropathology following single, as distinct from repeated, TBI reflects poly‐pathologies rather than a single entity (e.g. tauopathy; Smith et al., 2013b).

Animal studies show that single moderate or severe TBI, or repeated mTBI, can cause progressive neurodegeneration with cognitive and other behavioural changes (Smith et al., 1997; Pierce et al., 1998; Dixon et al., 1999; Aungst et al., 2014; Loane et al., 2014; Mouzon et al., 2014). Delayed progressive pathological changes have been demonstrated in clinical TBI imaging studies (Trivedi et al., 2007; Bendlin et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2008; Sidaros et al., 2008; 2009; Kumar et al., 2009; Farbota et al., 2012). Post‐traumatic neurodegeneration and/or neurological deficits have been linked to persistent neuroinflammation in preclinical (Nonaka et al., 1999; Nagamoto‐Combs et al., 2007; Acosta et al., 2013; Aungst et al., 2014; Loane et al., 2014; Mouzon et al., 2014) and neuropathological (Johnson et al., 2013) studies. Microglial activation has been proposed as an important pathobiological mechanism in major neurodegenerative disorders, including AD (Eikelenboom et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2010). Such neuroinflammation has also been reported in several case reports of CTE that described the presence of activated microglia throughout the brain following neurotrauma (McKee et al., 2010; Goldstein et al., 2012; Saing et al., 2012). Although no formal studies of neuroinflammation in CTE have been conducted to date, these results are provocative, and the involvement of neuroinflammation in CTE, including pathological evidence of microglia and astrocytes activation, has been previously noted (Daneshvar et al., 2015). Preclinical studies strongly support a role for chronic neurotoxic neuroinflammation in post‐traumatic degeneration and associated neurological or psychiatric symptoms, and several recent experimental studies have demonstrated that delayed, targeted anti‐inflammatory treatments can limit behavioural and pathological changes (Byrnes et al., 2012; Piao et al., 2013; Rodgers et al., 2014).

The analysis of the effects of SCI has, for long, focused on sensorimotor deficits, or secondary complications such as neuropathic pain or bladder/bowel/sexual dysfunction. Most early research on the pathophysiological changes following SCI was predominantly focused on the spinal cord and its afferent and efferent pathways. In contrast, minimal work has addressed the potential effects of SCI on brain regions that regulate learning and memory or emotions, despite accumulating clinical evidence showing significant neuropsychological changes. Recent MRI studies suggest that SCI can cause progressive and widespread brain changes (Nicotra et al., 2006; Wrigley et al., 2009; Freund et al., 2013). Our recently published work demonstrates that SCI in both mouse and rat models causes a chronic neuroinflammatory response in the brain (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b), similar to that observed experimentally and clinically after TBI. This chronic neuroinflammation is associated with progressive neurodegeneration in brain regions associated with cognitive decline and depressive‐like behaviour (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b).

Progressive neurodegeneration after TBI

Increasing evidence, both experimental and clinical, indicates that TBI can result in progressive neurodegeneration (Smith et al., 1997; Dixon et al., 1999; Trivedi et al., 2007; Bendlin et al., 2008; Sidaros et al., 2008; Farbota et al., 2012; Loane et al., 2014). In the late 1990s, Smith et al. (1997) reported progressive brain atrophy and cell loss in multiple brain regions following fluid percussion induced injury in rats. More recently, Loane et al. (2014) found progressive lesion development and neuronal cell loss, using both repeated MRI and histological measurements, through 1 year after controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury in mice. An increasing number of clinical imaging TBI studies have shown progressive tissue loss and brain atrophy, which are likely to reflect chronic neurodegenerative changes, for months to years after TBI (Trivedi et al., 2007; Bendlin et al., 2008; Ng et al., 2008; Sidaros et al., 2008; 2009; Kumar et al., 2009; Farbota et al., 2012). Alterations have been identified in both grey and white matter. In several of these studies, imaging data were correlated with neurological deficits. Importantly, progressive neurodegeneration has been reported after mild as well as moderate or severe TBI (Trivedi et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013). Furthermore, studies in children have also reported similar progressive degeneration after head injuries (Keightley et al., 2014).

Given the published reports on CTE and high‐impact sports, there has been considerable interest in whether repeated concussive or even sub‐concussive insults can lead to chronic neurodegeneration. A recent study used MRI to examine hippocampal size in relation to concussion history in collegiate football players (Singh et al., 2014). They demonstrated reduced hippocampal volumes in football players compared with age‐matched non‐football controls. The greatest changes were found in those with a documented concussion history and they reported an inverse relationship between hippocampal volumes or reaction times and years playing football. Other studies have also recently suggested that exposure to high‐impact sports can lead to brain imaging changes including hyperactivity in the default mode network (Johnson et al., 2014; Abbas et al., 2015) or delayed recovery of cerebral blood flow post‐concussion in slow‐to‐recover athletes (Meier et al., 2015), suggesting that even repeated sub‐concussive head exposures may lead to long‐term pathological alterations in the brain.

Chronic neuroinflammation after TBI

TBI is known to cause acute neuroinflammation that is associated with cytokine release (Loane and Byrnes, 2010; Ziebell and Morganti‐Kossmann, 2010). Indeed, many neuroprotective strategies have been directed at such inflammation or related factors (Kumar and Loane, 2012). Also well supported by clinical data, but less well appreciated is that clinical TBI can cause persistent microglial activation (Engel et al., 2000; Gentleman et al., 2004; Faden, 2011; Ramlackhansingh et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013a; Coughlin et al., 2015), and that such chronic neuroinflammation may contribute to neurodegeneration. Post‐mortem autopsy studies have revealed the presence of reactive microglia at months to years following a single TBI (Gentleman et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2013a). In fact, a recent study demonstrated the presence of CD68‐positive microglia in more than a quarter of brains examined with survival time of >1 year, and this was associated with white matter degeneration in these cases (Johnson et al., 2013). Another clinical TBI study used the PET translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) ligand ([11C]R‐PK11195) to examine chronic neuroinflammatory changes in patients months to years after a single head injury. Brain TSPO levels are increased after TBI in experimental models, likely due to increased expression by activated microglia during secondary neuroinflammation (Papadopoulos and Lecanu, 2009). Increased [11C]R‐PK11195 binding was found diffusely at sites distant from the trauma locus, indicating chronic neuroinflammatory changes in patients who suffered moderate‐to‐severe TBI (Ramlackhansingh et al., 2011). Moreover, localization of neuroinflammation in the diencephalon correlated with long‐term cognitive changes in these studies. Contrary to the neuropathological studies, [11C]R‐PK11195 binding was not observed in corpus callosum of TBI patients, which may be due to reduced sensitivity of the PET ligand for highly activated phagocytic (CD68 positive) microglia or other limitations in current methods to image neuroinflammation at high resolution in the human brain. However, another neuroimaging study using a second‐generation TSPO ligand, [11C]DPA‐713, in retired National Football Leagues (NFL) players supports the findings of Ramlackhansingh et al. and demonstrated increased radioligand binding in several brain regions, including supramarginal gyrus and right amygdala, in former NFL Players compared with age‐matched, healthy controls (Coughlin et al., 2015). Significant atrophy of the right hippocampus as well as varied performance on tests of verbal learning and memory in NFL players were reported, suggesting that neuroinflammatory changes may play a role in cognitive dysfunction and depression among former athletes exposed to sport‐related mTBI (Guskiewicz et al., 2005; Hart et al., 2013). In addition, recent biomarker studies have reported chronic increases of pro‐inflammatory cytokines either in serum or in CSF after head injury, with such changes associated with unfavourable neuropsychiatric outcomes (Juengst et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2014).

Experimental studies strongly support these clinical observations and suggest both possible mechanisms involved and potential therapeutic strategies (Holmin and Mathiesen, 1999; Nonaka et al., 1999; Nagamoto‐Combs et al., 2007; Acosta et al., 2013; Aungst et al., 2014; Loane et al., 2014; Mouzon et al., 2014). We recently reported that moderate‐level CCI in mice caused persistent microglial activation through 1 year post‐trauma that was associated with progressively increased lesion volume and neurodegeneration (Loane et al., 2014). Chronically activated microglia expressed major histocompatibility complex class II (CR3/43), CD68 and NADPH oxidase (NOX2) at the lesion margins at 1 year, along with evidence of oxidative stress. Several groups have shown that repeated mTBI can also cause chronic neuroinflammation associated with pathological changes (Shitaka et al., 2011; Aungst et al., 2014; Mouzon et al., 2014). Utilizing a repeated closed head injury mouse model, Shitaka et al. (2011) reported that reactive microglia were identified adjacent to injured axons at 7 weeks after repetitive mTBI. Also using the repeated mTBI mouse model, Mouzon et al. (2014) demonstrated persistent neuroinflammation and related white matter degeneration, as well as chronic cognitive deficits through 18 months. Our group used a rat lateral fluid percussion model to show that repeated, but not single, mTBI resulted in chronic microglial activation and parallel behavioural deficits, electrophysiological changes and neuronal cell loss (Aungst et al., 2014); importantly, repeated mTBI simulated alterations induced by a single moderate insult, with similar degrees of neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration and associated neurological deficits.

Given that persistent post‐traumatic microglial activation is correlated with chronic neurodegeneration and functional deficits, several studies have addressed whether outcome can be improved by therapeutic targeting of such neuroinflammation late after the traumatic insult. Following CCI in mice, Byrnes et al. (2012) randomized animals at 1 month with the mGlu5 receptor agonist 2‐chloro‐5‐hydroxyphenylglycine (CHPG), vehicle or drug plus an allosteric mGlu5 receptor antagonist. Delayed treatment starting at 1 month post‐injury significantly improved cognitive and motor recovery, while decreasing neuroinflammation, lesion volume and neuronal loss at 4 months post‐injury; in addition, ex vivo diffusion tensor imaging demonstrated considerably greater preservation of white matter tracks in treated animals than vehicle‐treated TBI controls (Byrnes et al., 2012). The protective effects of CHPG were blocked by the mGlu5 receptor antagonist 3‐((2‐Methyl‐4‐thiazolyl)ethynyl)pyridine, indicating that the neuroprotection was mediated by actions at mGlu5 receptors . Similar protective actions and therapeutic mechanisms were reported by Piao et al. (2013) using a delayed 4 week voluntary exercise regimen initiated 5 weeks after mouse CCI. Late, but not early, exercise implementation decreased chronic microglial activation and associated neurodegeneration, and ameliorated behavioural deficits after TBI (Piao et al., 2013); protective effects were associated with an inhibition of NADPH oxidase (NOX2) in microglia. Recently, Rodgers et al. (2014) reported that anti‐inflammatory treatment with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor ibudilast, beginning 1 month following fluid percussion injury in rats, resulted in decreased chronic anxiety‐like behaviour as well as reactive gliosis at 6 months post‐injury.

Microglia and infiltrating macrophages in the CNS are heterogeneous, with diverse functional phenotypes that range from pro‐inflammatory (M1‐like) phenotypes to immunosuppressive (M2‐like) phenotypes (David and Kroner, 2011; Kumar and Loane, 2012). The ‘M1/M2’ paradigm has been increasingly studied in neurodegenerative diseases in an attempt to uncover mechanisms of immunopathogenesis, and advances in understanding of molecular and functional states of microglia/macrophages may provide a framework to help elucidate the relative beneficial versus destructive roles of microglia/macrophages after TBI. Although most studies to date underscore the neurotoxic actions of persistent M1‐like microglial activation following TBI, it is now well recognized that M2‐like phenotypes have anti‐inflammatory and neurorestorative effects (Cherry et al., 2014). For example, by removing cellular debris by phagocytosis and releasing neurotrophic factors and anti‐inflammatory cytokines, microglia can prevent neuronal injury and restore tissue integrity in the injured brain (David and Kroner, 2011; Kumar and Loane, 2012).

Experimental studies in various models of CNS injury (SCI, stroke/ischaemia and TBI) have shown that the majority of microglia and recruited macrophages at the injury site have an M2‐like profile, but that the M2‐like response is short‐lived, with a phenotypic shift towards an M1‐like dominant response within 1 week (Kigerl et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Loane et al., 2014). M1‐like cells that dominate the lesion have reduced phagocytic activity, and increased secretion of pro‐inflammatory and neurotoxic mediators (IL‐1β, TNFα, superoxide radicals, nitric oxide), that can exacerbate injury and contribute to pathology. Following focal TBI, there is a transient up‐regulation of M2‐like markers such as CD206, arginase 1, Ym1, CD163, Fizz1, IL‐4 receptor α and TGFβ (Hsieh et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013; Loane et al., 2014; Turtzo et al., 2014), and the M2‐like phenotype appears to peak between 3 and 5 days post‐injury before tapering off significantly. This coincides with the peak of macrophage infiltration after TBI (Jin et al., 2012). Such observations point to highly complex phenotypic and functional responses after TBI, with resident and infiltrating subsets of cells being activated dynamically to promote either anti‐inflammatory and neuroprotective (M2‐like) or chronic neurotoxic (M1‐like) effects. Importantly, NOX2 activation, which we and others have implicated in post‐traumatic neurotoxic neuroinflammation (Block et al., 2007; Byrnes et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2012; Loane et al., 2014), may serve as a switch that serves to increase M1 activation while suppressing M2 activation (Choi et al., 2012). The concept of microglia/macrophage phenotype switching following TBI is at an early stage of development. Further research is needed to determine key regulatory mechanisms that control phenotype switching in microglia in order to develop therapeutic strategies to optimize functional recovery following TBI.

Cognitive impairment and remote neurodegeneration after SCI

Although not well appreciated by clinicians, there have been multiple reports that SCI patients frequently develop long‐term cognitive impairments (Richards et al., 1988; Roth et al., 1989; Davidoff et al., 1992; Dowler et al., 1997; Lazzaro et al., 2013). Using a battery of neuropsychological tests studies in SCI patients have identified performance impairments in memory span, executive functioning, attention, processing speed and learning ability (Roth et al., 1989; Davidoff et al., 1992; Dowler et al., 1995; 1997; Strubreither et al., 1997; Jensen et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2007; Lazzaro et al., 2013). Moreover, central psychophysiological indices of information processing using scalp‐recorded, late component, event‐related potentials (ERPs) suggested that ERP alterations in SCI patients reflect impairments in distributed integrative cortical/subcortical networks that are engaged in stimulus detection, evaluation and executive functioning (Lazzaro et al., 2013). However, such observations were often discounted as probably reflecting unappreciated concurrent head injuries. Yet, studies clearly show that SCI patients who present without a history of TBI may develop cognitive decline and neurological dysfunction (Hess et al., 2003; Jensen et al., 2007). After SCI, the incidence rate of depression more than doubles, increasing to between 25 and 47% (Umlauf, 1992; Arango‐Lasprilla et al., 2011). An earlier experimental study suggested cognitive decline after SCI, using a projectile injury in pigs wearing body armour (Zhang et al., 2011). But the model, species and outcome used (conditioned feeding behaviour) make both interpretation and relevant comparison difficult. Our recent work revealed that SCI in both mouse and rat causes impairment of spatial and retention memory and depressive‐like behaviour as demonstrated by diminished performance in the Morris water maze, Y‐maze, novel objective recognition, sucrose preference and tail suspension tests (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b). In addition to contributing to disability in their own right, these changes can also negatively affect rehabilitation and impair recovery. Remarkably, despite the clinical evidence showing SCI‐induced cognitive and affective changes, these changes have been assumed to be situational or reactive, and neither clinical nor experimental studies have addressed these changes at a mechanistic level with a view towards limiting such deficits or promoting recovery. Our results (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b) suggest that SCI can result in physiological changes in the brain that can be modified by inhibiting the post‐traumatic neuroinflammatory response.

SCI can produce extensive long‐term reorganization of the cerebral cortex (Endo et al., 2007; Freund et al., 2011), and complete thoracic SCI patients have decreased grey matter volume in primary motor cortex that is consistent with neuronal loss and/or atrophy (Wrigley et al., 2009). Prospective longitudinal MRI studies show that SCI can cause progressive reduction in grey matter volume not only in the sensorimotor cortex but also in the regions not directly connected to the injury site, such as cerebellar cortex, medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices that are critical for the processing of emotional relevant information and the modulation of attentional states (Nicotra et al., 2006; Wrigley et al., 2009; Freund et al., 2013). Crucially, myelin‐sensitive MRI parameters measured at 1 year were reduced within, but also beyond, the atrophic areas of the lesion (Freund et al., 2013). Collectively, these clinical studies suggest that SCI can cause progressive and widespread brain changes.

Until recently, assessment of neurodegeneration in the brain following experimental SCI focused on the sensorimotor cortex and medullary pyramid regions; results have been inconsistent, with outcomes ranging from no cell death to extensive retrograde degeneration (Kalil and Schneider, 1975; Feringa and Vahlsing, 1985; Ganchrow and Bernstein, 1985; Merline and Kalil, 1990; Bonatz et al., 2000; Hains et al., 2003a; Lee et al., 2004; Wannier et al., 2005; Kaas et al., 2008; Nielson et al., 2010; 2011). One of the limitations of these earlier SCI studies is that they were performed over poorly defined areas within the cerebral cortex and/or did not utilize rigorous quantitative assessment techniques. We used stereological methods with computer‐driven, random, systematic sampling to provide quantitative analysis of neuronal densities in defined brain regions after SCI. Isolated thoracic SCI in both rat and mouse models resulted in significant neuronal loss in the hippocampus, cortex and thalamus at 10–12 weeks post‐injury, but not at early time points (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b). Importantly, significant long‐term reduction in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (DG) subregion of the hippocampus has been reported after chronic cervical/thoracic SCI (Felix et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014a). In addition to inflammatory mechanisms (see below), cannabinoid CB1 receptors may be involved in such changes. CB1 receptor immunoreactivity was significantly increased in hippocampal subregions (CA3 and DG) following contusion SCI in rats (Knerlich‐Lukoschus et al., 2011), and this receptor has been implicated in regulation of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, including modulation of proliferation, survival and maturation of new neurons (Wolf et al., 2010).

Chronic neuroinflammation in the brain after SCI

SCI frequently causes neuropathic pain that is associated with chronic inflammation in both the dorsal horn and in spinothalamic projection sites in the thalamus (Schmitt et al., 2000; Hains et al., 2003b; Hains and Waxman, 2006; Zhao et al., 2007a, 2007b; Hulsebosch, 2008; Gwak et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2013a, 2013b). Felix et al. (2012) reported increased inflammation in the brain after rat cervical SCI. Changes included increased mRNA expression of the chemokine receptor CCR5 in the dorsal vagal complex and elevated TNFα in the subventricular zone and subgranular zone of the DG. After severe contusion induced SCI, the chemokines CCL2 and CCL3 were chronically expressed in thalamus, hippocampus (CA3 and DG subregions) and periaqueductal grey matter (Knerlich‐Lukoschus et al., 2011). Very recently, we used the TSPO ligand [125I]‐iodoDPA‐713 (Wang et al., 2009) that was used to analyse chronic neuroinflammation in retired NFL players (Coughlin et al., 2015), in autoradiography studies to assess brain inflammation after SCI in rats (Wu et al., 2014b). All brain regions examined (cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, caudate/putamen) showed significantly elevated [125I]‐iodoDPA‐713 binding. These data complemented microscopy data showing chronic microglial activation in the same brain regions after SCI that was associated with increased expression of markers for activated microglia, including TSPO, CD68 and the chemokine CCL21 (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b). Notably, CCL21 is known to activate microglia at more distant sites following SCI (Zhao et al., 2007b; Hulsebosch et al., 2009). Collectively, these studies indicate that isolated SCI can cause chronic brain inflammation that is remarkably similar to that observed after TBI, resulting in progressive delayed neurodegeneration and functional deficits that include cognitive impairment and depressive‐like behaviour (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b). The functional changes were associated with chronic microglial activation and concurrent activation of cell cycle pathways and CCL21 in the brain. Early treatment with a cell cycle inhibitor following SCI largely prevented both the post‐traumatic neuroinflammation in the brain and the long‐term cognitive dysfunction (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b).

SCI in both rat and mouse models causes significant increases of M1‐like microglial activation genes and MHC II expression in the hippocampus, along with changes in M2‐like markers that are species dependent (Wu et al., 2014a, 2014b). M1/M2‐like phenotypic switching probably depends on the local signals in the microenvironment. However, as our analyses used tissue homogenates, the cellular origin of the gene expression changes remains to be determined.

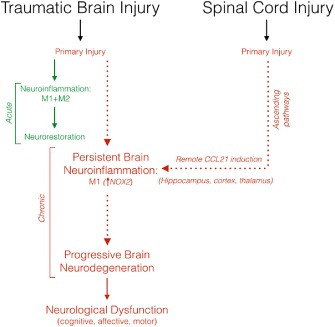

Chronic traumatic inflammatory encephalopathy (CTIE): linking acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders

Although acute neuroinflammation has been implicated in the pathophysiology of both TBI and SCI, a role for chronic brain inflammation and related neurodegeneration in neurotrauma has only recently been recognized (Faden and Loane, 2015). Neuroinflammation is implicated in the pathobiology of most chronic neurodegenerative disorders (Block et al., 2007), and may provide a mechanistic link to the chronic brain neurodegeneration observed after brain or spinal cord trauma ( Figure 1). There is no accepted nomenclature for persistent post‐traumatic neuroinflammation. Chronic traumatic encephalitis probably best describes the persistent M1‐like microglial activation and reactive astroglial changes that occur after TBI or SCI. It clearly shares key pathological features with other, better defined, non‐infectious forms of chronic encephalitis, such as autoimmune encephalitis or paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (Leypoldt and Wandinger, 2014; Leypoldt et al., 2015). But the resulting abbreviation – CTE – would be confused with the well‐established abbreviation for the condition of chronic traumatic encephalopathy found after repeated head injuries (McKee et al., 2009; 2013). Chronic posttraumatic neuroinflammation or chronic traumatic inflammatory encephalopathy (CTIE) appear to be more accurate descriptions, with the latter better conveying the association with brain dysfunction. Finally, chronic traumatic brain inflammation is appropriately descriptive and would have the abbreviation CTBI, although this does not convey the pathological association with neurodegeneration or dysfunction. Thus, either CTIE or CTBI would serve as reasonable descriptors for this important condition. Whatever term is used, this disorder may be a more common cause of progressive neuropsychiatric dysfunction after TBI than CTE. Unlike CTE, chronic neuroinflammation occurs following single moderate or severe TBI, as well as after repeated brain trauma. Moreover, as supported by recent research, CTIE/CTBI can be treated effectively weeks after injury (Byrnes et al., 2012; Piao et al., 2013; Rodgers et al., 2014), which suggests the possibility of effective targeted clinical neuroprotection long after a traumatic insult.

Figure 1.

Chronic inflammation‐mediated neurodegeneration after TBI and SCI. In the acute phase after TBI, M1‐ and M2‐like microglia are activated to limit the primary injury by removing damaged tissue by phagocytosis and resolving destructive pro‐inflammatory responses to improve brain repair and promote neurorestoration. However, repeated mTBI or moderate‐to‐severe TBI results in chronic microglial activation characterized by a predominant M1‐like activation state (i.e. NOX2‐positive neurotoxic phenotype) that contributes to progressive neurodegeneration and loss of neurological function. Similarly, isolated SCI can cause chronic neuroinflammation in the cortex, hippocampus and thalamus at delayed time points after injury. CCL21 expression is up‐regulated in the brain and is associated with increased microglial activation and neurodegeneration, which can cause long‐term neurological deficits after SCI.

Conclusions

Although CTE and AD have received the most attention as chronic brain disorders following TBI, CTIE/CTBI appears to be a more frequent and more likely contributing mechanism for progressive neurodegeneration and related cognitive decline. Surprisingly, SCI may also not uncommonly cause chronic brain inflammation and progressive neurodegeneration, with functional impairments. Thus, both TBI and SCI should be considered chronic, as well as acute, neurodegenerative disorders, in which potentially treatable chronic neuroinflammation plays a critical role.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS037313, R01NS052568, R01NR013601 (A. I. F.) and R01NS082308 (D. J. L.).

Faden, A. I. , Wu, J. , Stoica, B. A. , and Loane, D. J. (2016) Progressive inflammation‐mediated neurodegeneration after traumatic brain or spinal cord injury. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 681–691. doi: 10.1111/bph.13179.

References

- Abbas K, Shenk TE, Poole VN, Breedlove EL, Leverenz LJ, Nauman EA et al (2015). Alteration of default mode network in high school football athletes due to repetitive subconcussive mild traumatic brain injury: a resting‐state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain Connect 5: 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta SA, Tajiri N, Shinozuka K, Ishikawa H, Grimmig B, Diamond D et al (2013). Long‐term upregulation of inflammation and suppression of cell proliferation in the brain of adult rats exposed to traumatic brain injury using the controlled cortical impact model. PLoS ONE 8: e53376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Catalytic Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1676–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1797–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al (2013c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein‐Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1459–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango‐Lasprilla JC, Ketchum JM, Starkweather A, Nicholls E, Wilk AR (2011). Factors predicting depression among persons with spinal cord injury 1 to 5 years post injury. Neurorehabilitation 29: 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aungst SL, Kabadi SV, Thompson SM, Stoica BA, Faden AI (2014). Repeated mild traumatic brain injury causes chronic neuroinflammation, changes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, and associated cognitive deficits. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34: 1223–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Kaup A, Kirby KA, Byers AL, Diaz‐Arrastia R, Yaffe K (2014). Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology 83: 312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlin BB, Ries ML, Lazar M, Alexander AL, Dempsey RJ, Rowley HA et al (2008). Longitudinal changes in patients with traumatic brain injury assessed with diffusion‐tensor and volumetric imaging. Neuroimage 42: 503–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS (2007). Microglia‐mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonatz H, Rohrig S, Mestres P, Meyer M, Giehl KM (2000). An axotomy model for the induction of death of rat and mouse corticospinal neurons in vivo. J Neurosci Methods 100: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes KR, Loane DJ, Stoica BA, Zhang J, Faden AI (2012). Delayed mGluR5 activation limits neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 9: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry JD, Olschowka JA, O'Banion MK (2014). Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. J Neuroinflammation 11: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Aid S, Kim HW, Jackson SH, Bosetti F (2012). Inhibition of NADPH oxidase promotes alternative and anti‐inflammatory microglial activation during neuroinflammation. J Neurochem 120: 292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Munro CA, Ma S, Yue C, Chen S et al (2015). Neuroinflammation and brain atrophy in former NFL players: an in vivo multimodal imaging pilot study. Neurobiol Dis 74: 58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dams‐O'Connor K, Gibbons LE, Bowen JD, McCurry SM, Larson EB, Crane PK (2013). Risk for late‐life re‐injury, dementia and death among individuals with traumatic brain injury: a population‐based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84: 177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar DH, Goldstein LE, Kiernan PT, Stein TD, McKee AC (2015). Post‐traumatic neurodegeneration and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Mol Cell Neurosci pii: S1044‐7431(15)00036‐6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- David S, Kroner A (2011). Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff GN, Roth EJ, Richards JS (1992). Cognitive deficits in spinal cord injury: epidemiology and outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 73: 275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon CE, Kochanek PM, Yan HQ, Schiding JK, Griffith RG, Baum E et al (1999). One‐year study of spatial memory performance, brain morphology, and cholinergic markers after moderate controlled cortical impact in rats. J Neurotrauma 16: 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S et al (2014). Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 370: 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowler RN, O'Brien SA, Haaland KY, Harrington DL, Feel F, Fiedler K (1995). Neuropsychological functioning following a spinal cord injury. Appl Neuropsychol 2: 124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowler RN, Harrington DL, Haaland KY, Swanda RM, Fee F, Fiedler K (1997). Profiles of cognitive functioning in chronic spinal cord injury and the role of moderating variables. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 3: 464–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelenboom P, van Exel E, Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Rozemuller AJ, van Gool WA (2010). Neuroinflammation – an early event in both the history and pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis 7: 38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Spenger C, Tominaga T, Brene S, Olson L (2007). Cortical sensory map rearrangement after spinal cord injury: fMRI responses linked to Nogo signalling. Brain 130: 2951–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel S, Schluesener H, Mittelbronn M, Seid K, Adjodah D, Wehner HD et al (2000). Dynamics of microglial activation after human traumatic brain injury are revealed by delayed expression of macrophage‐related proteins MRP8 and MRP14. Acta Neuropathol 100: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden AI (2011). Microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol 70: 345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden AI, Loane DJ (2015). Chronic neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury: Alzheimer disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or persistent neuroinflammation? Neurother 12: 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbota KD, Sodhi A, Bendlin BB, McLaren DG, Xu G, Rowley HA et al (2012). Longitudinal volumetric changes following traumatic brain injury: a tensor‐based morphometry study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 18: 1006–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix MS, Popa N, Djelloul M, Boucraut J, Gauthier P, Bauer S et al (2012). Alteration of forebrain neurogenesis after cervical spinal cord injury in the adult rat. Front Neurosci 6: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feringa ER, Vahlsing HL (1985). Labeled corticospinal neurons one year after spinal cord transection. Neurosci Lett 58: 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund P, Weiskopf N, Ward NS, Hutton C, Gall A, Ciccarelli O et al (2011). Disability, atrophy and cortical reorganization following spinal cord injury. Brain 134: 1610–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund P, Weiskopf N, Ashburner J, Wolf K, Sutter R, Altmann DR et al (2013). MRI investigation of the sensorimotor cortex and the corticospinal tract after acute spinal cord injury: a prospective longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol 12: 873–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganchrow D, Bernstein JJ (1985). Thoracic dorsal funicular lesions affect the bouton patterns on, and diameters of, layer VB pyramidal cell somata in rat hindlimb cortex. J Neurosci Res 14: 71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Zhou H, Hong JS (2012). NADPH oxidases: novel therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 33: 295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Kaup A, Barnes DE, Yaffe K (2014). Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: the role of age and severity. JAMA Neurol 71: 1490–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman SM, Leclercq PD, Moyes L, Graham DI, Smith C, Griffin WS et al (2004). Long‐term intracerebral inflammatory response after traumatic brain injury. Forensic Sci Int 146: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA, Zhang XL, Velisek L, Sullivan JA et al (2012). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast‐exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model. Sci Transl Med 4: 134ra160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves AB, White E, Koepsell TD, Reifler BV, van Belle G, Larson EB et al (1990). The association between head trauma and Alzheimer's disease. Am J Epidemiol 131: 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, McCrea M, Cantu RC, Randolph C et al (2005). Association between recurrent concussion and late‐life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players. Neurosurgery 57: 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwak YS, Hassler SE, Hulsebosch CE (2013). Reactive oxygen species contribute to neuropathic pain and locomotor dysfunction via activation of CamKII in remote segments following spinal cord contusion injury in rats. Pain 154: 1699–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Waxman SG (2006). Activated microglia contribute to the maintenance of chronic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 26: 4308–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Black JA, Waxman SG (2003a). Primary cortical motor neurons undergo apoptosis after axotomizing spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol 462: 328–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Klein JP, Saab CY, Craner MJ, Black JA, Waxman SG (2003b). Upregulation of sodium channel Nav1.3 and functional involvement in neuronal hyperexcitability associated with central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 23: 8881–8892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J Jr, Kraut MA, Womack KB, Strain J, Didehbani N, Bartz E et al (2013). Neuroimaging of cognitive dysfunction and depression in aging retired National Football League players: a cross‐sectional study. JAMA Neurol 70: 326–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess DW, Marwitz JH, Kreutzer JS (2003). Neuropsychological impairments after spinal cord injury: a comparative study with mild traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Psychol 48: 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Holmin S, Mathiesen T (1999). Long‐term intracerebral inflammatory response after experimental focal brain injury in rat. Neuroreport 10: 1889–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CL, Kim CC, Ryba BE, Niemi EC, Bando JK, Locksley RM et al (2013). Traumatic brain injury induces macrophage subsets in the brain. Eur J Immunol 43: 2010–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S et al (2012). Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 43: 3063–3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebosch CE (2008). Gliopathy ensures persistent inflammation and chronic pain after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 214: 6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebosch CE, Hains BC, Crown ED, Carlton SM (2009). Mechanisms of chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Brain Res Rev 60: 202–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Kuehn CM, Amtmann D, Cardenas DD (2007). Symptom burden in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88: 638–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Ishii H, Bai Z, Itokazu T, Yamashita T (2012). Temporal changes in cell marker expression and cellular infiltration in a controlled cortical impact model in adult male C57BL/6 mice. PLoS ONE 7: e41892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B, Neuberger T, Gay M, Hallett M, Slobounov S (2014). Effects of subconcussive head trauma on the default mode network of the brain. J Neurotrauma 31: 1907–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2010). Traumatic brain injury and amyloid‐beta pathology: a link to Alzheimer's disease? Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH (2011). Acute and chronically increased immunoreactivity to phosphorylation‐independent but not pathological TDP‐43 after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Acta Neuropathol 122: 715–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2012). Widespread tau and amyloid‐Beta pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol 22: 142–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W (2013). Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 136: 28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengst SB, Kumar RG, Arenth PM, Wagner AK (2014). Exploratory associations with Tumor Necrosis Factor‐alpha, disinhibition and suicidal endorsement after traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun 41: 134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Qi HX, Burish MJ, Gharbawie OA, Onifer SM, Massey JM (2008). Cortical and subcortical plasticity in the brains of humans, primates, and rats after damage to sensory afferents in the dorsal columns of the spinal cord. Exp Neurol 209: 407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalil K, Schneider GE (1975). Retrograde cortical and axonal changes following lesions of the pyramidal tract. Brain Res 89: 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley ML, Sinopoli KJ, Davis KD, Mikulis DJ, Wennberg R, Tartaglia MC et al (2014). Is there evidence for neurodegenerative change following traumatic brain injury in children and youth? A scoping review. Front Hum Neurosci 8: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG (2009). Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci 29: 13435–13444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerlich‐Lukoschus F, Noack M, von der Ropp‐Brenner B, Lucius R, Mehdorn HM, Held‐Feindt J (2011). Spinal cord injuries induce changes in CB1 cannabinoid receptor and C‐C chemokine expression in brain areas underlying circuitry of chronic pain conditions. J Neurotrauma 28: 619–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Loane DJ (2012). Neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury: opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Brain Behav Immun 26: 1191–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Stoica BA, Sabirzhanov B, Burns MP, Faden AI, Loane DJ (2013). Traumatic brain injury in aged animals increases lesion size and chronically alters microglial/macrophage classical and alternative activation states. Neurobiol Aging 34: 1397–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Husain M, Gupta RK, Hasan KM, Haris M, Agarwal AK et al (2009). Serial changes in the white matter diffusion tensor imaging metrics in moderate traumatic brain injury and correlation with neuro‐cognitive function. J Neurotrauma 26: 481–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RG, Boles JA, Wagner AK (2014). Chronic inflammation after severe traumatic brain injury: characterization and associations with outcome at 6 and 12 months postinjury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro I, Tran Y, Wijesuriya N, Craig A (2013). Central correlates of impaired information processing in people with spinal cord injury. J Clin Neurophysiol 30: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Lee KH, Kim UJ, Yoon DH, Sohn JH, Choi SS et al (2004). Injury in the spinal cord may produce cell death in the brain. Brain Res 1020: 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, Hou SW, Lee CC, Hsu CY, Huang YS, Su YC (2013). Increased risk of dementia in patients with mild traumatic brain injury: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS ONE 8: e62422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leypoldt F, Wandinger KP (2014). Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Clin Exp Immunol 175: 336–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leypoldt F, Armangue T, Dalmau J (2015). Autoimmune encephalopathies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1338: 94–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loane DJ, Byrnes KR (2010). Role of microglia in neurotrauma. Neurother 7: 366–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loane DJ, Kumar A, Stoica BA, Cabatbat R, Faden AI (2014). Progressive neurodegeneration after experimental brain trauma: association with chronic microglial activation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73: 14–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley‐Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE et al (2009). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68: 709–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Gavett BE, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, Kowall NW et al (2010). TDP‐43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69: 918–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH et al (2013). The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 136: 43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier TB, Bellgowan PS, Singh R, Kuplicki R, Polanski DW, Mayer AR (2015). Recovery of cerebral blood flow following sports‐related concussion. JAMA Neurol 72: 530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline M, Kalil K (1990). Cell death of corticospinal neurons is induced by axotomy before but not after innervation of spinal targets. J Comp Neurol 296: 506–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JA, French LR, Hutton JT, Schuman LM (1985). Head injury as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 35: 264–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JA, van Duijn CM, Chandra V, Fratiglioni L, Graves AB, Heyman A et al (1991). Head trauma as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: a collaborative re‐analysis of case‐control studies. EURODEM Risk Factors Research Group. Int J Epidemiol 20 (Suppl. 2): S28–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzon BC, Bachmeier C, Ferro A, Ojo JO, Crynen G, Acker CM et al (2014). Chronic neuropathological and neurobehavioral changes in a repetitive mild traumatic brain injury model. Ann Neurol 75: 241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray ME, Lowe VJ, Graff‐Radford NR, Liesinger AM, Cannon A, Przybelski SA et al (2015). Clinicopathologic and 11C‐Pittsburgh compound B implications of Thal amyloid phase across the Alzheimer's disease spectrum. Brain 138 (Pt 5): 1370–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RF, Asghari A, Egorov DD, Rutkowski SB, Siddall PJ, Soden RJ et al (2007). Impact of spinal cord injury on self‐perceived pre‐ and postmorbid cognitive, emotional and physical functioning. Spinal Cord 45: 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamoto‐Combs K, McNeal DW, Morecraft RJ, Combs CK (2007). Prolonged microgliosis in the rhesus monkey central nervous system after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 24: 1719–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K, Mikulis DJ, Glazer J, Kabani N, Till C, Greenberg G et al (2008). Magnetic resonance imaging evidence of progression of subacute brain atrophy in moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89: S35–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotra A, Critchley HD, Mathias CJ, Dolan RJ (2006). Emotional and autonomic consequences of spinal cord injury explored using functional brain imaging. Brain 129: 718–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson JL, Sears‐Kraxberger I, Strong MK, Wong JK, Willenberg R, Steward O (2010). Unexpected survival of neurons of origin of the pyramidal tract after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 30: 11516–11528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson JL, Strong MK, Steward O (2011). A reassessment of whether cortical motor neurons die following spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol 519: 2852–2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka M, Chen XH, Pierce JE, Leoni MJ, McIntosh TK, Wolf JA et al (1999). Prolonged activation of NF‐kappaB following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 16: 1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom P, Michaelsson K, Gustafson Y, Nordstrom A (2014). Traumatic brain injury and young onset dementia: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Neurol 75: 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omalu BI, DeKosky ST, Minster RL, Kamboh MI, Hamilton RL, Wecht CH (2005). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player. Neurosurgery 57: 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos V, Lecanu L (2009). Translocator protein (18 kDa) TSPO: an emerging therapeutic target in neurotrauma. Exp Neurol 219: 53–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al; NC‐IUPHAR (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res 42 (Database Issue): D1098–D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH, Nicoll JA, Holmes C (2010). Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 6: 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao CS, Stoica BA, Wu J, Sabirzhanov B, Zhao Z, Cabatbat R et al (2013). Late exercise reduces neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis 54: 252–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JE, Smith DH, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK (1998). Enduring cognitive, neurobehavioral and histopathological changes persist for up to one year following severe experimental brain injury in rats. Neuroscience 87: 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Havlik RJ, Steffens DC, Helms MJ, Newman TN, Drosdick D et al (2000). Documented head injury in early adulthood and risk of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Neurology 55: 1158–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramlackhansingh AF, Brooks DJ, Greenwood RJ, Bose SK, Turkheimer FE, Kinnunen KM et al (2011). Inflammation after trauma: microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol 70: 374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS, Brown L, Hagglund K, Bua G, Reeder K (1988). Spinal cord injury and concomitant traumatic brain injury. Results of a longitudinal investigation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 67: 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GW, Gentleman SM, Lynch A, Graham DI (1991). Beta A4 amyloid protein deposition in brain after head trauma. Lancet 338: 1422–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GW, Gentleman SM, Lynch A, Murray L, Landon M, Graham DI (1994). Beta amyloid protein deposition in the brain after severe head injury: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57: 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers KM, Deming YK, Bercum FM, Chumachenko SY, Wieseler JL, Johnson KW et al (2014). Reversal of established traumatic brain injury‐induced, anxiety‐like behavior in rats after delayed, post‐injury neuroimmune suppression. J Neurotrauma 31: 487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth E, Davidoff G, Thomas P, Doljanac R, Dijkers M, Berent S et al (1989). A controlled study of neuropsychological deficits in acute spinal cord injury patients. Paraplegia 27: 480–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saing T, Dick M, Nelson PT, Kim RC, Cribbs DH, Head E (2012). Frontal cortex neuropathology in dementia pugilistica. J Neurotrauma 29: 1054–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M et al (2014). Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 370: 322–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt AB, Buss A, Breuer S, Brook GA, Pech K, Martin D et al (2000). Major histocompatibility complex class II expression by activated microglia caudal to lesions of descending tracts in the human spinal cord is not associated with a T cell response. Acta Neuropathol 100: 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitaka Y, Tran HT, Bennett RE, Sanchez L, Levy MA, Dikranian K et al (2011). Repetitive closed‐skull traumatic brain injury in mice causes persistent multifocal axonal injury and microglial reactivity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70: 551–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidaros A, Engberg AW, Sidaros K, Liptrot MG, Herning M, Petersen P et al (2008). Diffusion tensor imaging during recovery from severe traumatic brain injury and relation to clinical outcome: a longitudinal study. Brain 131: 559–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidaros A, Skimminge A, Liptrot MG, Sidaros K, Engberg AW, Herning M et al (2009). Long‐term global and regional brain volume changes following severe traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal study with clinical correlates. Neuroimage 44: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Meier TB, Kuplicki R, Savitz J, Mukai I, Cavanagh L et al (2014). Relationship of collegiate football experience and concussion with hippocampal volume and cognitive outcomes. JAMA 311: 1883–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Gentleman SM, Leclercq PD, Murray LS, Griffin WS, Graham DI et al (2013a). The neuroinflammatory response in humans after traumatic brain injury. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 39: 654–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DH, Chen XH, Pierce JE, Wolf JA, Trojanowski JQ, Graham DI et al (1997). Progressive atrophy and neuron death for one year following brain trauma in the rat. J Neurotrauma 14: 715–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DH, Johnson VE, Stewart W (2013b). Chronic neuropathologies of single and repetitive TBI: substrates of dementia? Nat Rev Neurol 9: 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strubreither W, Hackbusch B, Hermann‐Gruber M, Stahr G, Jonas HP (1997). Neuropsychological aspects of the rehabilitation of patients with paralysis from a spinal injury who also have a brain injury. Spinal Cord 35: 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MA, Ward MA, Hess TM, Gale SD, Dempsey RJ, Rowley HA et al (2007). Longitudinal changes in global brain volume between 79 and 409 days after traumatic brain injury: relationship with duration of coma. J Neurotrauma 24: 766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turtzo LC, Lescher J, Janes L, Dean DD, Budde MD, Frank JA (2014). Macrophagic and microglial responses after focal traumatic brain injury in the female rat. J Neuroinflammation 11: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umlauf RL (1992). Psychological interventions for chronic pain following spinal cord injury. Clin J Pain 8: 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Zhang J, Hu X, Zhang L, Mao L, Jiang X et al (2013). Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics in white matter after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33: 1864–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Pullambhatla M, Guilarte TR, Mease RC, Pomper MG (2009). Synthesis of [(125)I]iodoDPA‐713: a new probe for imaging inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 389: 80–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HK, Lin SH, Sung PS, Wu MH, Hung KW, Wang LC et al (2012). Population based study on patients with traumatic brain injury suggests increased risk of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83: 1080–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannier T, Schmidlin E, Bloch J, Rouiller EM (2005). A unilateral section of the corticospinal tract at cervical level in primate does not lead to measurable cell loss in motor cortex. J Neurotrauma 22: 703–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SA, Bick‐Sander A, Fabel K, Leal‐Galicia P, Tauber S, Ramirez‐Rodriguez G et al (2010). Cannabinoid receptor CB1 mediates baseline and activity‐induced survival of new neurons in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Commun Signal 8: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley PJ, Gustin SM, Macey PM, Nash PG, Gandevia SC, Macefield VG et al (2009). Anatomical changes in human motor cortex and motor pathways following complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Cereb Cortex 19: 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Renn CL, Faden AI, Dorsey SG (2013a). TrkB.T1 contributes to neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury through regulation of cell cycle pathways. J Neurosci 33: 12447–12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Raver C, Piao C, Keller A, Faden AI (2013b). Cell cycle activation contributes to increased neuronal activity in the posterior thalamic nucleus and associated chronic hyperesthesia after rat spinal cord contusion. Neurother 10: 520–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zhao Z, Sabirzhanov B, Stoica BA, Kumar A, Luo T et al (2014a). Spinal cord injury causes brain inflammation associated with cognitive and affective changes: role of cell cycle pathways. J Neurosci 34: 10989–11006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Stoica BA, Luo T, Sabirzhanov B, Zhao Z, Guanciale K et al (2014b). Isolated spinal cord contusion in rats induces chronic brain neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairment. Cell Cycle 13: 2446–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Huang Y, Su Z, Wang S, Wang S, Wang J et al (2011). Neurological, functional, and biomechanical characteristics after high‐velocity behind armor blunt trauma of the spine. J Trauma 71: 1680–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Waxman SG, Hains BC (2007a). Extracellular signal‐regulated kinase‐regulated microglia‐neuron signaling by prostaglandin E2 contributes to pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 27: 2357–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Waxman SG, Hains BC (2007b). Modulation of thalamic nociceptive processing after spinal cord injury through remote activation of thalamic microglia by cysteine cysteine chemokine ligand 21. J Neurosci 27: 8893–8902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Kierans A, Kenul D, Ge Y, Rath J, Reaume J et al (2013). Mild traumatic brain injury: longitudinal regional brain volume changes. Radiology 267: 880–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebell JM, Morganti‐Kossmann MC (2010). Involvement of pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Neurother 7: 22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]