Abstract

RNA is a polymeric molecule implicated in various biological processes, such as the coding, decoding, regulation, and expression of genes. Numerous studies have examined RNA features using whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) approaches. RNA-seq is a powerful technique for characterizing and quantifying the transcriptome and accelerates the development of bioinformatics software. In this review, we introduce routine RNA-seq workflow together with related software, focusing particularly on transcriptome reconstruction and expression quantification.

Keywords: bioinformatics tools, gene expression, high-throughput RNA sequencing, transcript

Introduction

The transcriptome is the entire set of RNA transcripts in a given cell for a specific developmental stage or physiological condition [1]. Understanding the transcriptome is necessary for interpreting the functional elements of the genome as well as for understanding the underlying mechanisms of development and disease. Microarray technologies have been used for high-throughput large-scale RNA-level studies, such as to identify differentially expressed genes between developmental stages or between healthy and diseased groups [2]. However, its hybridization- based nature limits the ability to catalog and quantify RNA molecules expressed under various conditions. Advances in massive parallel DNA sequencing technologies have enabled transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) by sequencing of cDNA. RNA-seq has rapidly replaced microarray technology because of its better resolution and higher reproducibility; this method can be used to extend our knowledge of alternative splicing events [3], novel genes and transcripts [4], and fusion transcripts [5].

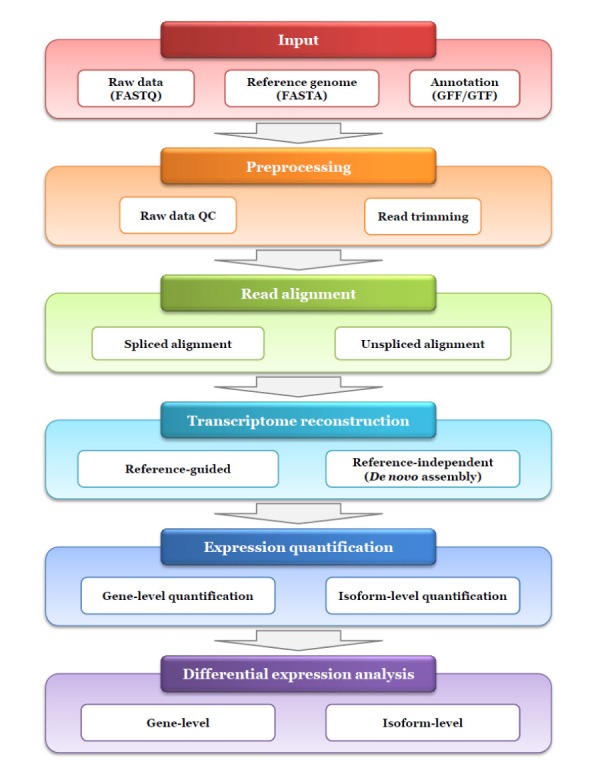

One concern regarding the application of RNA-seq is abundance estimation at the gene-level and transcript-level differential expression under distinct conditions. Routine RNA-seq workflow may consist of the following five steps as shown in Fig. 1: (1) preprocessing of raw data, (2) read alignment, (3) transcriptome reconstruction, (4) expression quantification, and (5) differential expression analysis. As an initial step, RNA-seq data may be subjected to quality control (QC) of the raw data before data analysis. Similar to whole genome or exome sequencing, read alignment can be performed to map the reads to the reference genome or transcriptome. Clinical samples including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimen and cancer tissue biopsies are often degraded or exist in limited amount [6]. Thus additional QC procedure can be performed to evaluate the performance of the RNA-seq experiment itself after read alignment. Next, transcriptome reconstruction is carried out to identify all transcripts expressed in a specimen based on read mapping data. If there is no available reference sequence, this procedure can be conducted directly using a de novo assembly approach. Once all transcripts are identified, their abundances can be estimated using read mapping data. Finally, differential expression analysis is conducted using currently available programs. In this review, we discuss the RNA-seq workflow and its related bioinformatics tools in each step (Table 1), focusing on transcriptome reconstruction and abundance quantification.

Fig. 1. Typical workflow for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis. This workflow shows an example for expression quantification and differential expression analysis at gene and/or transcript level using RNA-seq, which is typically consisted of five steps as following: preprocessing, read alignment, transcriptome reconstruction, expression quantification and differential expression analysis. For each step, currently available programs are written in Table 1. QC, quality control.

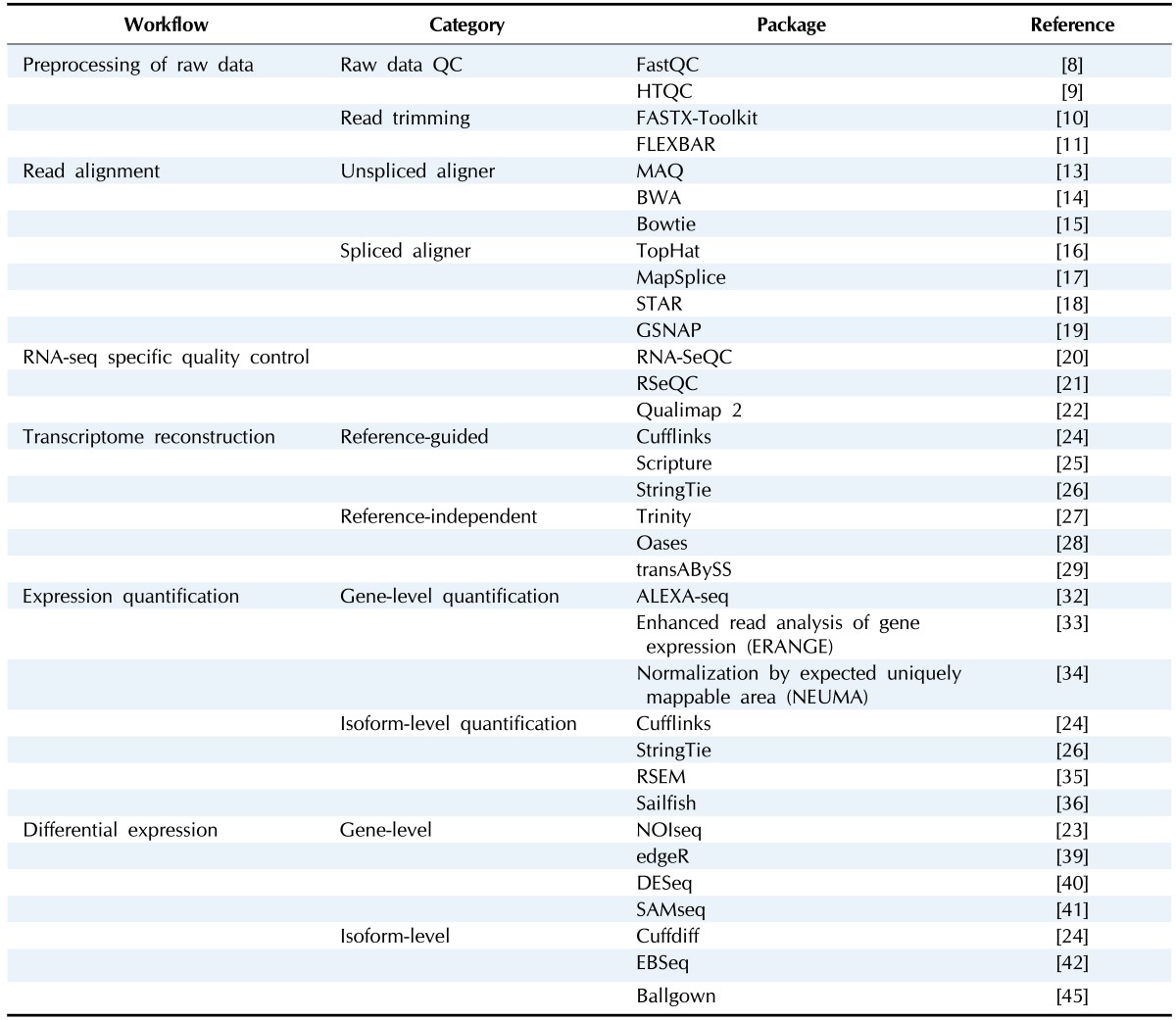

Table 1. Selected list of RNA-seq analysis programs.

RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; MAQ, Mapping and Assembly with Quality; BWA, Burrow-Wheeler Aligner.

Preprocessing of Raw Data

Similarly to whole genome or exome sequencing, RNAseq data is formatted in FASTQ (sequence and base quality). Numerous erroneous sequence variants can be introduced during the library preparation, sequencing, and imaging steps [7], which should be identified and filtered out in the data analysis step. Thus, QC of raw data should be performed as the initial step of routine RNA-seq workflow. Tools such as FastQC [8] and HTQC [9] can be applied in this step to assess the quality of raw data, enabling assessment of the overall and per-base quality for each read (i.e., read 1 and 2 in case of paired-end sequencing) in each sample. Depending on the RNA-seq library construction strategy, some form of read trimming may be advisable prior to aligning the RNA-seq data. Two common trimming strategies include "adapter trimming" and "quality trimming." Adapter trimming involves removal of the adapter sequence by masking specific sequences used during library construction. Quality trimming generally removes the ends of reads where base quality scores have decreased to a level such that sequence errors and the resulting mismatches prevent reads from aligning. The adapter trimming step is typically not necessary, as most recent sequencers provide raw data in which the adapters are already trimmed. In contrast, quality trimming may be an essential step depending on the analysis strategy used. The FASTX-Toolkit [10] and FLEXBAR [11] are useful for this purpose.

Read Alignment

There are two strategies in which a genome or transcriptome is used as a reference for the read alignment step [12]. The transcriptome comprises all transcripts in a given specimen and in which splicing has been conducted by including the exons and excluding the introns. If a transcriptome is used as a reference, unspliced aligners that do not allow large gaps may be the proper choice for accurate read mapping. Stampy, Mapping and Assembly with Quality (MAQ) [13], Burrow-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [14], and Bowtie [15] can be used in this case. This alignment is limited to the identification of known exons and junctions because it does not identify splicing events involving novel exons. However, if the genome is used as a reference, spliced aligners that allow a wide range of gaps should be employed because reads aligned at exon-exon junctions will be split into two fragments. This approach may increase the probability of identifying novel transcripts generated by alternative splicing. Various spliced aligners have been developed, including TopHat [16], MapSplice [17], STAR [18], and GSNAP [19].

RNA-Seq Specific QC

Several intrinsic biases and limitations including nucleotide composition bias, GC bias and polymerase chain reaction bias can be introduced to RNA-seq data of clinical samples with low quality or quantity. To evaluate the biases from RNA-seq data, several metrics may be examined as following: percentage of exonic or rRNA reads, accuracy and biases in gene expression measurements, GC bias, evenness of coverage, 5'-to-3' coverage bias, and coverage of 5' and 3' ends [6]. Some programs including RNA-SeQC [20], RSeQC [21], and Qualimap 2 [22] are currently available for the purposes, which take typically BAM file as input.

RNA-SeQC [20] provides three types of QC metrics based on read count (total, unique and duplicate reads, rRNA content, strand specificity, etc.), coverage (mean coverage, 5'/3' coverage, GC bias, etc.), and expression correlation (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads [RPKM]–based estimation of expression levels and correlation matrix by all pairwise comparison). The software also provides multisample evaluation regarding library construction protocols, input materials and other experimental parameters.

RSeQC [21] is a Python-based package program that provides several metrics containing sequence quality, GC bias, polymerase chain reaction bias, nucleotide composition bias, sequencing depth, strand specificity, coverage uniformity, and read distribution over the genome structure. Of the metrics, sequencing depth is importance, because it allows users to determine if current RNA-seq data is suitable for such application including expression profiling, alternative splicing analysis, novel isoform identification, and transcriptome reconstruction by checking whether the sequencing depth is saturated or not.

Qualimap 2 [22] is consisted of four analysis modes: BAM QC, Counts QC, RNA-seq QC, and Multi-sample BAM QC. Compared to previous release, this version focuses on multi-sample QC for high-throughput sequencing data. Multi-sample BAM QC mode allows combined QC for multiple alignment files, which takes the metrics from the single-sample BAM QC mode as input. RNA-seq QC mode is added to compute the metrics specific to RNA-seq data, which contains per-transcript coverage, junction sequence distribution, genomic localization of reads, 5'-3' bias and consistency of the library protocol. Counts QC mode enables to estimate the saturation of sequencing depth, read count densities, correlation of samples and distribution of counts among classes of selected features along with gene expression estimation based on NOIseq [23].

Transcriptome Reconstruction

Transcriptome reconstruction is the identification of all transcripts expressed in a specimen. There are two strategies used for transcriptome reconstruction, including the reference-guided approach and the reference-independent approach. First, the reference-guided approach consists of two sequential steps: (1) alignment of raw reads to the reference as described in the previous section and (2) assembly of overlapping reads for reconstructing transcripts. This approach is advantageous when reference annotation information is well-known, such as in human and mouse, which is employed in Cufflinks [24], Scripture [25], and StringTie [26]. Second, the reference-independent approach uses a de novo assembly algorithm to directly build consensus transcripts from short reads without reference, which is useful when there is no known reference genome or transcriptome. Trinity [27], Oases [28], and transABySS [29] may be used for this purpose.

Two publications have described RNA-seq protocols: one is de novo transcriptome reconstruction without reference using the Trinity platform [30] and the other is differential expression analysis of a gene and transcript using a combination of TopHat and Cufflinks [31]. The latter protocol also includes a transcriptome reconstruction procedure (using Cufflinks) from read mapping data to a reference genome (using TopHat). These protocols are good examples of different strategies that can be used for transcriptome reconstruction according to the presence or absence of a reference sequence.

Expression Quantification

Numerous methods have been developed for expression quantification using RNA-seq data. The methods are grouped into two according to the target levels: gene- and isoform-level quantification. Alternative expression analysis by sequencing (ALEXA-seq) [32], enhanced read analysis of gene expression (ERANGE) [33], and normalization by expected uniquely mappable area (NEUMA) [34] support gene-level quantification. Isoform-level quantification methods are divided into three groups according to the reference type and requirement of alignment results. The first group (e.g., RSEM [35]) requires the alignment result of reads using the transcriptome as a reference. The second group (e.g., Cufflinks [24] and StringTie [26]) also requires alignment results of reads using whole genome sequences as a reference rather than the transcriptome. The last group (e.g., Sailfish [36]) uses an alignment-free method. We discuss each isoform-level quantification method in detail in the following sections.

RSEM

RSEM is software that quantifies transcript-level abundance from RNA-seq data. RSEM is operated in two steps: (1) generation and preprocessing of a set of reference transcript sequences and (2) alignment of reads to the reference transcripts followed by estimation of transcript abundances and their credibility intervals. A FASTA formatted file of transcript sequences is used to generate the reference transcripts, which can be obtained from a reference genome database, a de novo transcriptome assembler, or an Expressed Sequence Tags (EST) database. Alternatively, a gene annotation file in GTF format and the full genome sequence in FASTA format may be supplied. RSEM uses the Bowtie alignment program [15]. A user-provided aligner can be used for mapping RNA-seq reads using reference transcripts. RSEM provides gene-level and isoform-level estimates as the primary output by computing maximum likelihood abundance estimates based on the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm after read mapping. Abundance estimates are given in terms of two measures: an estimate of the number of fragments and the estimated fraction of transcripts comprising a given isoform or gene. The latter estimates can be multiplied by 10-6 to obtain a measure of transcripts per million (TPM). RSEM also supports the visualization of alignment and read depth using a genome browser such as the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser.

Cufflinks

The Tuxedo package is the most widely used software for transcript assembly and quantification using RNA-seq and consists of a number of different programs, including TopHat, Cufflinks, and Cuffdiff [31]. In the initial step, TopHat is employed for mapping raw RNA-seq reads to a reference genome, where some reads can be spliced when they were aligned on the exon-exon junctions of transcripts. These mapped reads are provided as input to Cufflinks for transcript assembly and abundance estimation. Transcript assembly is achieved by building an overlap graph from the mapped reads followed by computing minimal path cover in the overlap graph, generating a minimum number of transcripts that will explain all reads in the graph. Abundance estimation is performed by estimating the maximum likelihood abundance based on transcript coverage and compatibility together with the use of fragment length distribution. Abundances are reported in fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments (FPKM) for paired-end and RPKM for a single-end. Cuffdiff, a part of the Cufflinks package, also uses the mapped reads to report genes and transcripts that are differentially expressed. CummeRbund can produce figures and plots from the Cuffdiff outputs.

StringTie

StringTie is software used for transcriptome reconstruction and abundance estimation. Similarly to other tools, including Cufflinks, spliced aligners such as TopHat2 [37] or GSNAP [19] are used to directly align RNA-seq reads or subsequent alignment after generating pre-assembled contigs from the reads using a de novo assembler such as MaSurCa [38]. StringTie can perform transcriptome reconstruction and abundance estimation simultaneously by building a flow network for the path of the heaviest coverage and computing the maximum flow to estimate abundance. StringTie reports estimated abundance in FPKM for paired-end and RPKM for single-end.

Sailfish

Sailfish is unique software adopting an alignment-free approach for isoform quantification. An index is built from a set of reference transcripts and a specific choice of k-mer length, which consists of data structures that maps each k-mer in the reference transcripts to a unique integer identifier, enabling to count k-mers in a set of reads and to resolve their origin in the set of transcripts. Until the set of reference transcripts or the k-mer length is changed, it is not necessary to rebuild the index. Sailfish computes an estimate of the relative abundance of each transcript in the reference by employing an EM algorithm similar to that used in RSEM. Because Sailfish avoids read alignment entirely, the running time for quantification is much lower than for other existing methods. Sailfish reports terms of abundance measures, including (1) RPKM, (2) k-mers per kilobase per million mapped k-mers (KPKM), and (3) TPM.

We described four programs, RSEM, Cufflinks, StringTie, and Sailfish in detail. In addition to the use of specific algorithm, a major difference between these programs may be the reference type used. A set of transcript sequences is used as a reference in RSEM and Sailfish, indicating that the programs may be suitable for estimating the abundance of known transcripts. In contrast, a reference genome is employed in Cufflinks and StringTie, making it possible to present the estimated abundance of novel transcripts as well as already known transcripts, as spliced read mapping data can reveal known and novel splice junction information simultaneously.

Differential Expression using RNA-seq

For differential expression analysis, a number of software packages and pipelines have been developed including edgeR [39], DESeq [40], NOIseq [23], SAMseq [41], Cuffdiff [24], and EBSeq [42]. Unlike edgeR and DESeq, which adopt negative binomial models, and NOIseq and SAMseq, which are non-parametric, Cuffdiff and EBSeq can be used to compare differentially expressed genes by employing transcript-based detection methods. Many of the programs accept read count data as input, which can be produced by using HTSeq [43] or BEDTools [44]. Similarly to Cuffdiff, Ballgown program [45] is employed for differential expression analysis using read mapping data from StringTie [26] (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/index.shtml?t=manual). The above programs adopt one or more of the several available normalization methods (total count, upper quartile, median, DESeq normalization, trimmed mean of M values, quantile and RPKM normalization) to correct biases that may appear between samples (sequencing depth [33]) or within sample (gene length [46] and GC contents [45]).

Although many programs have been developed, one research group reported that there may be large differences between these programs and that no single method may be optimal under all experimental conditions [48]. Thus, it may be difficult for most of users with no or weak statistical background to select a proper method. However, because RNA-seq data sets are rapidly accumulating, we expect that new bioinformatics tools for differential expression will be developed, which will function robustly under a wide range of conditions.

Conclusion

Numerous bioinformatics programs have been developed for RNA-seq data analysis. Even tools developed for a same purpose are based on distinct approaches using different algorithms and models. The diversity of the methodology makes it possible to customize analysis protocols by choosing a program that provides the best fit to each specific goal. In this review, we described the routine RNA-seq analysis workflow, focusing on transcriptome reconstruction and expression quantification, and also introduced its related bioinformatics programs. Therefore, we expect that this review will be helpful for preparing a specific pipeline for RNA-seq data analysis, enabling to design new biological experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bio-Synergy Research Project (NRF-2014M3A9C4066449) of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning through the National Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Ozsolak F, Milos PM. RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:87–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marioni JC, Mason CE, Mane SM, Stephens M, Gilad Y. RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 2008;18:1509–1517. doi: 10.1101/gr.079558.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denoeud F, Aury JM, Da Silva C, Noel B, Rogier O, Delledonne M, et al. Annotating genomes with massive-scale RNA sequencing. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R175. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-12-r175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher CA, Kumar-Sinha C, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Han B, Jing X, et al. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009;458:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adiconis X, Borges-Rivera D, Satija R, DeLuca DS, Busby MA, Berlin AM, et al. Comparative analysis of RNA sequencing methods for degraded or low-input samples. Nat Methods. 2013;10:623–629. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robasky K, Lewis NE, Church GM. The role of replicates for error mitigation in next-generation sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babraham Bioinformatics. Fast QC. Cambridgeshire: Babraham Institute; 2015. [Accessed 2015 Nov 2]. Available from: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Liu D, Liu F, Wu J, Zou J, Xiao X, et al. HTQC: a fast quality control toolkit for Illumina sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FASTX-Toolkit. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2015. [Accessed 2015 Nov 2]. Available from: http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodt M, Roehr JT, Ahmed R, Dieterich C. FLEXBAR-flexiblebarcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. Biology (Basel) 2012;1:895–905. doi: 10.3390/biology1030895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garber M, Grabherr MG, Guttman M, Trapnell C. Computational methods for transcriptome annotation and quantification using RNA-seq. Nat Methods. 2011;8:469–477. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Ruan J, Durbin R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008;18:1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang K, Singh D, Zeng Z, Coleman SJ, Huang Y, Savich GL, et al. MapSplice: accurate mapping of RNA-seq reads for splice junction discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e178. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu TD, Nacu S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:873–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLuca DS, Levin JZ, Sivachenko A, Fennell T, Nazaire MD, Williams C, et al. RNA-SeQC: RNA-seq metrics for quality control and process optimization. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1530–1532. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Wang S, Li W. RSeQC: quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2184–2185. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okonechnikov K, Conesa A, Garcia-Alcalde F. Qualimap 2: advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015 Oct 1; doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv566. [Epub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarazona S, Furio-Tari P, Turra D, Pietro AD, Nueda MJ, Ferrer A, et al. Data quality aware analysis of differential expression in RNA-seq with NOISeq R/Bioc package. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guttman M, Garber M, Levin JZ, Donaghey J, Robinson J, Adiconis X, et al. Ab initio reconstruction of cell type-specific transcriptomes in mouse reveals the conserved multi-exonic structure of lincRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E. Oases: robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1086–1092. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson G, Schein J, Chiu R, Corbett R, Field M, Jackman SD, et al. De novo assembly and analysis of RNA-seq data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:909–912. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith M, Griffith OL, Mwenifumbo J, Goya R, Morrissy AS, Morin RD, et al. Alternative expression analysis by RNA sequencing. Nat Methods. 2010;7:843–847. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S, Seo CH, Lim B, Yang JO, Oh J, Kim M, et al. Accurate quantification of transcriptome from RNA-Seq data by effective length normalization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patro R, Mount SM, Kingsford C. Sailfish enables alignment-free isoform quantification from RNA-seq reads using lightweight algorithms. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:462–464. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimin AV, Marcais G, Puiu D, Roberts M, Salzberg SL, Yorke JA. The MaSuRCA genome assembler. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2669–2677. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, Tibshirani R. Finding consistent patterns: a nonparametric approach for identifying differential expression in RNA-Seq data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:519–536. doi: 10.1177/0962280211428386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leng N, Dawson JA, Thomson JA, Ruotti V, Rissman AI, Smits BM, et al. EBSeq: an empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1035–1043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq: a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quinlan AR. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2014;47:11.12.1–11.12.34. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frazee AC, Pertea G, Jaffe AE, Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Leek JT. Ballgown bridges the gap between transcriptome assembly and expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:243–246. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oshlack A, Wakefield MJ. Transcript length bias in RNA-seq data confounds systems biology. Biol Direct. 2009;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pickrell JK, Marioni JC, Pai AA, Degner JF, Engelhardt BE, Nkadori E, et al. Understanding mechanisms underlying human gene expression variation with RNA sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:768–772. doi: 10.1038/nature08872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seyednasrollah F, Laiho A, Elo LL. Comparison of software packages for detecting differential expression in RNA-seq studies. Brief Bioinform. 2015;16:59–70. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]