Abstract

Objective

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) include the application of meditation and mind-body practices used to promote mindful awareness in daily life. Operationalizing the construct of mindfulness is important in order to determine mechanisms of therapeutic change elicited by mindfulness practice. In addition to existing state and trait measures of mindfulness, process measures are needed to assess the ways in which individuals apply mindfulness in the context of their practice.

Method

This report details three independent studies (qualitative interview, N = 8; scale validation, N = 134; and replication study, N = 180) and the mixed qualitative-quantitative methodology used to develop and validate the Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS), a 15-item process measure designed to quantify how mindfulness practitioners actively use mindfulness to remediate psychological suffering in their daily lives.

Results

In Study 1, cognitive interviewing yielded a readily comprehensible and accessible scale of 15 items. In Study 2, exploratory factor analysis derived a potential three-factor solution: decentering, positive emotion regulation, and negative emotion regulation. In Study 3, confirmatory factor analysis verified better model fit with the three-factor structure over the one-factor structure.

Conclusions

AMPS functions as a measure to quantify the application of mindfulness and processes of change in the context of MBIs and general mindfulness practice.

Keywords: Mindfulness, process measure, coping, validation, scale, psychometric, meditation, mindfulness-based intervention

Introduction

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) include an amalgam of mind-body practices used to enhance a mode of mindful awareness characterized by a present-centered non-judgmental attention to experience liberated from cognitive-emotional abstractions and preoccupations (see (Kabat-Zinn, 2003) for an extended definition and discussion). Over the last decade, MBIs have received significant public and empirical attention. Particularly, extant research has shed light on the therapeutic benefits of MBIs toward psychological and physical health ailments, including addiction (Black, 2014; Garland, Manusov, et al., 2014), learning disabilities (Black, Milam, & Sussman, 2009), distress in persons with chronic illness (Bohlmeijer, Prenger, Taal, & Cuijpers, 2010) and healthy persons (Chiesa & Serretti, 2009), somatic problems (De Vibe, Bjørndal, Tipton, Hammerstrøm, & Kowalski, 2012), obesity-related behaviors (O’Reilly, Cook, Spruijt-Metz, & Black, 2014), and immune function in people living with HIV (SeyedAlinaghi et al., 2012).

While these studies greatly add to our knowledge of the therapeutic benefits of mindfulness, psychometric scales currently used to operationalize the suspected central ingredient of MBIs mainly assess the presence or absence of state-like or dispositional (trait-like) characteristics (e.g., lapses in attention, inability to express oneself) underlying mindfulness. As a result, there remains limited understanding of the degree to which mindfulness-based practices and skills are applied in daily life when life stressors are encountered. Limitations to measuring mindfulness have been discussed (Grossman & Van Dam, 2011; Van Dam, Hobkirk, Danoff-Burg, & Earleywine, 2012), and warrant the development of a process measure to use in the context of research on MBIs in order to elucidate therapeutic modes of change attained through mindfulness practice.

Among the available scales are the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Brown & Ryan, 2003), the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006), Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) (Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmüller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006), Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale (CAMS) (Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007), the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS) (Cardaciotto, Herbert, Forman, Moitra, & Farrow, 2008), and the Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS) (Lau et al., 2006), as well as others less tested scales. Together, these scales offer different conceptual or linguistic approaches to capture the gamut of mindful states or traits. While some items may superficially appear to be behavioral in nature, these items are actually capturing the presence or absence of state- or trait-like mindfulness during one’s experiences (e.g., being non-judgmental, attentive, and focused on events in the present moment) rather than the actual perception of how mindfulness is applied when encountering the challenges and stresses of daily life.

The process of applying mindfulness in everyday life is known as mindfulness practice. In that regard, practice refers to the use of formal and informal techniques and approaches to achieving mindfulness as the moment unfolds (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Both the way and the degree to which a person has engaged in practice (taken together, the process of mindfulness practice) are likely to influence both their level of mindfulness and the clinical benefits that flow from it (Chiesa, 2013; Chiesa, Anselmi, & Serretti, 2014; Chiesa & Malinowski, 2011; Erisman & Roemer, 2012). Yet, even with a control condition, it is difficult to attribute increases in mindfulness directly to daily mindful practice rather than other external elements such as benefit’s expectations or changes in social support (Chiesa et al., 2014; Chiesa & Malinowski, 2011) without measuring mindfulness practice concurrently with existing scales of mindful states. Another value of a measuring the application of mindfulness practice is that it can elucidate how the practical value of mindfulness differs between persons, and in turn, how it influences their perspectives on life and values (Chiesa, 2013; Grossman & Van Dam, 2011).

Given that existing mindfulness measures already provide comprehensive ways to capture the mindfulness as a state (e.g., TMS) or disposition (e.g., FFMQ), a process measure of mindfulness practice offers a way to capture a different therapeutic aspect of MBIs—namely, how people actively apply mindfulness in everyday life to cope with daily hassles, stressors, and adversity. In other words, in conjunction with evaluating the relative presence or absence of state- or trait-like characteristics representing mindfulness, it may be important to measure mindfulness as a process measure to describe and quantify the ways in which people actively apply mindfulness practice to life experiences. Together, these measures would allow researchers to better identify pathways and mechanisms by which mindfulness and associated benefits are achieved in participants enrolled in trials of MBIs and in the context of daily life. For example, researchers (Chiesa, 2013; Chiesa et al., 2014) describe the challenge of determining whether changes in self-reported mindfulness levels following completion of MBIs truly reflect improvement or are instead biased by social desirability biases. A potential way to address this issue would be to test associations between reports of applied mindfulness practice (i.e., the process of mindfulness practice) when encountering stressors and expected benefits of mindfulness, as well as the degree to which these associations are mediated or moderated by levels of state or dispositional mindfulness. Lastly, a process measure may provide a means for researchers to measure maintenance behaviors pertaining to mindfulness practice, as this is required for longer-term achievement of mindfulness (Chiesa et al., 2014).

For these reasons, the objective of the present study is to develop a psychometric process measure, guided by both qualitative inquiry and quantitative empirical data, which captures the use of applied mindfulness practice in everyday life. We obtained data from three independent samples corresponding to three different studies. Each study informed the next by using a mixed methods approach inclusive of both qualitative and quantitative data collection.

STUDY 1 Materials and Methods

Study 1 employed a reflexive approach to qualitative inquiry that allowed us to identify initial domains of mindfulness application and then to refine our understanding around these domains (Agee, 2009). The first stage employed conventional content analysis, which involved obtaining domains of mindful practice and names for these domains from the data rather than using preconceived domains (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The second stage utilized directed content analysis to confirm these categories and to refine items developed to reflect these categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Participants

In Study 1, a total of eight participants were recruited for qualitative content analysis. Participants were mindfulness practitioners sampled from regions across the United States who had received various forms of training, including MBSR, Zen Buddhist meditation, and Goenka vipassana. The practitioners were recruited via quota sampling to capture varying levels of experience with mindfulness practice (adept practitioners – e.g., an individual trained in the Shambhala Buddhist tradition with >25 years of practice experience; intermediate practitioners – e.g., an individual with ≥5 years training in MBSR and Southeast Asian vipassana; novice practitioner – e.g., an individual who had completed a MBSR course and had <1 year of practice experience). The sample was comprised of six female participants and two males, with ages ranging from 27–60. Of the 8 participants, seven were Caucasian and one was Hispanic. Education levels varied from Bachelor’s to post-doctorate degree.

Procedures

In the first stage of Study 1, qualitative data were obtained via in-depth, semi-structured interviews, varying in length between 25–50 minutes. Following the recommendations outlined by Padgett (1998), the interview schedule was designed with careful attention to wording questions in a manner that would promote the disclosure of indigenous beliefs instead of eliciting simple confirmation of the researcher’s theory. Using the mindfulness and coping literatures as guiding conceptual frameworks, a series of open-ended questions were crafted with the intent to avoid embedding implicit answers: “How have you used mindfulness to help you cope with stress or challenges in life? When you have dealt with everyday kind of hassles, how have you used mindfulness to help yourself? When you have faced seriously difficult life situations, how have you used mindfulness to help yourself? How have you used mindfulness to help you improve stressful or difficult situations in your life?” (Baer, 2003; Bishop et al., 2004; Folkman, 1997; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Hölzel et al., 2011; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). These questions were used as prompts to stimulate discussion of the use of mindfulness practice in everyday life.

The interview schedule was viewed as a heuristic device to facilitate an inductive exploration of the phenomena under question. Interviewees answered questions from the interview schedule, and elaborated on themes and issues related to applications of mindfulness. In line with a constructivist-phenomenological approach to qualitative interviewing, the interviewer was aware to avoid imposing preconceived theoretical notions on interviewees. This approach acknowledges how the stance of the researcher can inadvertently shape interview responses, and consequently eschews the imposition of a priori theorizing on interview responses by promoting a stance of openness and curiosity (Ercikan & Roth, 2006).

Interview data were transcribed and then managed, coded, and subsequently analyzed using the software program ATLAS/ti Version 5.0 for Windows. Coding and analysis of interview data accorded with the method previously detailed (Harry, Sturges, & Klingner, 2005). Open and in-vivo coding procedures were used to apply first-level descriptors to the raw data (Harry et al., 2005). A total of 42 codes were developed using the method of constant comparison, where the researcher engaged in an iterative process of examining interview data to develop conceptual labels that then informed the subsequent interpretation and coding of data. Out of these iterations, open codes were aggregated into logical categories by relating them to each other via inductive and deductive reasoning. These superordinate categories were then mined for underlying themes. Finally, a typology was generated from the concrete instances and themes depicted in the interviews (Weiss, 1994). During the process of generating the codes, an independent researcher with more than a decade of qualitative research and cognitive interviewing experience (not one of the authors) reviewed the coding scheme and provided suggestions for alternative means of coding responses.

Following established guidelines (DeVellis, 2003), induction from these qualitative themes and deduction from theory informed the construction of a 15-item instrument with a 5-point Likert scale called the Applied Mindfulness Process Scale (AMPS), which we designed to assess the varieties of mindfulness application. To capture applied mindful practice from a number of perspectives, three question items were generated to tap each of the five themes identified in Study 1 (i.e., decentering, reappraisal, relaxation, stopping, and savoring). Prominent theoretical conceptualizations of mindfulness and coping were used to clarify the operationalization of mindfulness and coping into discrete, specific, and measurable variables (Baer, 2003; Folkman, 1997; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Hölzel et al., 2011; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In-vivo descriptions of interviewees were used to guide the wording of scale items. The same independent researcher involved in reviewing the coding scheme also reviewed the scale items that had been formed as a result of the cognitive interviewing and qualitative analysis, and provided feedback regarding item content and structure. In addition, the AMPS was reviewed by two consultants, one of whom was a licensed psychotherapist with expertise in stress and coping and MBIs and another who was a researcher with considerable experience with cognitive interviewing methodology.

The readability of items was ensured by obtaining a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score with Microsoft Word, which rated the items to be at a 7th grade reading level. Items were worded positively to avoid confusion (DeVellis, 2003). Items were equally weighted to allow for the possibility of calculating a summary score for the total scale. A response format indicating degree of endorsement of scale items was used to quantify how often a respondent used each mindfulness-related action to cope with adverse events. A time frame of one week was specified in order to capture mindful coping over time in response to participation in MBIs.

The second stage of Study 1 was key to the reflexive process of refining the AMPS instrument and confirming the domains of mindfulness practice captured by its items (Agee, 2009). Directed content analysis was employed to cross-check the categorical themes and AMPS scale items developed from Study 1 (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Following an established protocol (Willis, 2005), the interviewer employed cognitive interviewing techniques (Woolley, Bowen, & Bowen, 2004), which entailed think out loud interviewing and verbal probes (i.e., “How did you arrive at that answer?”) to prompt further discussion when the directive to “Think out loud as you answer this question” gave insufficient information. This combined technique was used to monitor information processing and metacognitive processes involved in answering scale items (Willis, 2005; Woolley et al., 2004). Ultimately, this systematic evaluation of how respondents interpreted questions was designed to improve test score interpretation (i.e., validity) of the measure around the domains of mindfulness practice. This informed scale revision was then subjected to cognitive interviewing with the sample of mindfulness practitioners described above. Using a directed content analysis, all feedback was transcribed, informally characterized, analyzed (including frequency counts of problems with questions), and then incorporated into a final iteration of the scale. The IRB authors’ home institution approved all procedures in Study 1.

STUDY 1 Results

Qualitative content analysis of the first stage of interviews derived five predominant themes for mindful applied processes: decentering, reappraisal, relaxation, stopping, and savoring. The qualitative themes uncovered by our interviews were as follows:

Decentering

Decentering, the metacognitive process of viewing thoughts, feelings, sensations, and the sense of self not as veritable realities but as ephemeral, insubstantial phenomena within the field of awareness, was identified by all three interviews as an essential component of mindful achievement(Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995). An adept practitioner made a philosophical expression of her use of decentering to “hold the space of awareness in the present moment, so that what is coming up can just come up… and I don’t have to react to it so quickly... just experience it coming up, and let it have its space.” An intermediate practitioner discussed how she used mindfulness to decenter from “the loop of your thoughts… you create this little story in your head. You can see that you’re creating this little story and you can say, ‘Ok, that’s a little story. I don’t have to buy into that.’” A novice practitioner spoke about her use of decentering to “step back” and dis-identify from her self-denigrating thoughts about her Hispanic accent.

Reppraisal

Positive reappraisal is an emotion-focused cognitive strategy through which events are re-construed as benign, beneficial, or meaningful for the purpose of regulating negative emotions and coping with stress (Folkman, 1997; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Congruent with conceptual and empirical work suggesting that mindfulness training may promote positive reappraisal (Garland, Farb, Goldin, & Fredrickson, 2015), all three interview respondents identified this strategy as an integral component of coping with mindfulness (Garland, Gaylord, & Park, 2009; Garland, Gaylord, & Fredrickson, 2011; Troy, Shallcross, Davis, & Mauss, 2013). In discussing her coping with adverse work and family circumstances, an adept practitioner described using mindfulness as a way of “reframing or framing the situation as a practice opportunity because otherwise, that actually helps me to heighten my awareness.” An intermediate practitioner reported that she used mindfulness to reappraise stressful situations when her son “is not attentive to deadlines and being 21 and driving too fast… I can stop and say ‘Is this the end of the world? No, it’s not.’… It’s a matter of being able to reevaluate the situation.” A novice practitioner succinctly expressed that “mindfulness just affirms my ability to see the positive in any situation. To see the positive part of anything, even a bad or negative situation.”

Relaxation

Consistent with classical conceptualizations of mindfulness as a means of generating a relaxation response or a balance between hyper- and hypo- arousal, both the intermediate and novice practitioners mentioned using the mindfulness technique of attending to the breath as a means of producing physiological and emotional relaxation in the face of adversity (Benson, Beary, & Carol, 1974; Britton, Lindahl, Cahn, Davis, & Goldman, 2014). When her son was admitted to the hospital for a seizure, a novice practitioner used mindful breathing to calm herself: “When I was in the ER waiting for him to be released, I was sitting and breathing.”

Stopping

Mindfulness is thought to facilitate self-regulation of automatic behavioral reactions to negative thoughts and emotions (Jimenez, Niles, & Park, 2010; Tang et al., 2007). This theme was reflected in comments from both the adept and novice practitioners. An adept practitioner explained that she was able use mindfulness to stop her negative reactions at work: “a particular employee is really passive aggressive, and is very cruel … I am very aware of this situation - I don’t give any energy to it. I think, okay this happens, and this person might be having a bad day.” In contrast, she found it more difficult to stop her reactions via mindfulness during confrontations with her son: “Whenever my son and I get into it, whenever I argue with him, things get worse... I am working my way back from how many minutes of yelling and screaming to how soon can I cut it off [with mindfulness].” On the contrary, a novice practitioner reported that mindfulness helped her to stop her negative reactions to a family member. After completing her initial MBSR course, she found that she was “happy, more open to talk with him or to listen to him. Before I was yelling at him in situations when I was disappointed with him. I don’t do that anymore.”

Savoring

The last theme expressed by the interviewees related to their use of mindfulness to cope by enhancing their sense of reward from pleasant events, a finding has been corroborated by recent empirical research (Garland, Froeliger, & Howard, 2014, 2015; Geschwind, Peeters, Drukker, van Os, & Wichers, 2011). An adept practitioner reported that mindfulness was a form of “cultivation of being in the present moment - you get to appreciate the moment.” A novice practitioner stated that mindfulness had enabled her to “appreciate nature” which in turn helps her to savor “the good things that happen every day”. Savoring of pleasant events through mindfulness is theorized to broaden the practitioner’s attentional scope beyond an initial focus on immediate stressors to encompass positively-valenced features of the environment from which he or she might derive a sense of contentment or happiness (Garland et al., 2010).

Findings from directed content analysis confirmed these domains captured by our scale and informed iterative refinement of scale items. Cognitive interviewing (Willis, 2005) and content analysis regarding preliminary items highlighted recommendations and informed changes in wording of items, redundancy of items, requests for clarification about the meaning of questions, and requests for clarification regarding response options. Feedback from the initial review of scale items led to a revision of the wording of the original question stems and response options. Once respondents found the last iteration of the scale to be comprehensible and clear, we moved to a quantitative evaluation of the scale in a large sample of practitioners.

STUDY 2 Materials and Methods

Participants

Data from a second sample (N=134) were used to test the psychometric properties of the AMPS. The sample had a mean age of 32.3 (SD=10.1, range=18–55), 62.9% were female, and the average respondent completed a Master’s degree. The majority of the sample was White (85.5%), followed by Asian (3.0%), Hispanic (1.5%), Black (1.0%), and other (9.0%). Most (92.5%) of respondents had some form of formal training in mindfulness meditation (MBSR, MBCT, or Buddhist forms of mindfulness training from the Tibetan, Zen, Mahayana, and Theravada traditions), and the average number of years of meditation practice was 10.8 (SD=8.4, range = 1–31 years). The majority of respondents reported 6 to 10 hours of meditation per month (range ≤1 hour to 36–40 hours).

Procedures

Participants for Study 2, were obtained by sending an email containing a link to the electronic survey was sent to a listserv comprised of mindfulness practitioners during a one-month period in Fall 2010. The hyperlink provided information about the study and assured anonymity of responses. The online survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete. A total of 134 respondents completed the online survey. The IRB of the authors’ home institution approved all study procedures.

Measures

The AMPS with administration instructions is provided in the Appendix. The AMPS is conceptualized as a process measure that quantifies the frequency with which people use various mindfulness approaches to cope with daily stressors. Respondents are asked to indicate how often they have used mindfulness to cope in a variety of ways for the period of the past 7 days. Response options range from 0--Never to 4--Almost always. Higher scores indicate more frequent use of each particular item of applied mindfulness.

Two additional scales of mindfulness were measured to determine the relationship between the AMPS and previously validated measures of trait mindfulness. A validated six-item version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Cronbach’s α = .87; 4-week test-retest r = .81) (Cronbach’s α = .89; 12-week test-retest r = .52) was used to quantify trait mindfulness in everyday experience (Black, Sussman, Johnson, & Milam, 2012; Brown & Ryan, 2003). A brief version was used to reduce respondent burden. Response options range from 1--almost always to 6--almost never. Responses were reverse coded and higher scores indicate higher trait mindfulness. The 14-item Freiberg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) as measured previously (Kohls, Sauer, & Walach, 2009) was used to quantify trait mindfulness in the past seven days. Response options range from 1--rarely to 4--almost always and higher scores indicate higher mindfulness (Kohls et al., 2009; Walach et al., 2006).

Three measures of mental health or wellbeing were assessed to determine relationships between the AMPS and other substantive measures. The five-item WHO Well Being Index (WHO-5) assesses subjective wellbeing as an indicator of overall perceived quality of life experienced in the past 2 weeks (WHO, 1998). Response options range from 0--not present to 5--constantly present. Scores were summed and higher scores indicate more subjective wellbeing. The one-item Personal Wellbeing Index is measures global life-satisfaction (i.e., Thinking about your own life and personal circumstances, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole?) (International Wellbeing Group, 2006). Response options from 0 completely dissatisfied to 10 completely satisfied and higher scores indicate higher life satisfaction. The 21-item Depression, Anxiety, Stress (DASS-21) quantifies the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress experienced in the past week (Henry & Crawford, 2005; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Response option from 1--Did not apply to me at all to 4--Applied to me most of the time; and higher scores indicate higher levels of negative emotional states.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses for Study 2 were analyzed in SPSS v20 and in Mplus v5. The intent of this analysis was to determine if the AMPS contained multiple factors. First, using Mplus, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component analysis was conducted, and model fit was assessed via the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Visual inspection of the scree plot informed the number of underlying factors. Goodness of fit criteria includes CFI and TLI values of 0.90 or greater, RMSEA estimates of 0.08 or less, and SRMR estimates of 0.06 or less. The maximum likelihood estimation default was used to produce fit indices. To provide a metric for latent factors, the path from the first factor loading was set at a value of 1.0, which is the default in Mplus.

Scale test score reliability was assessed with Cronbach’s α and item–total correlation values. To determine the interpretation of test scores, correlational relationships between the AMPS and related psychometric scale scores of substantive interest were assessed to determine nomological validity. To make substantive sense, the AMPS should be positively and significantly correlated with other measures of mindfulness (e.g., MAAS, FMI) and with measures of psychological health. Moreover, the AMPS should be negatively and significantly correlated with psychological ailments (e.g., depression, stress, and anxiety). Partial correlations were used to interpret test scores for incremental validity (i.e., correlations between the AMPS and the other measures were assessed after adjusting for validated trait mindfulness scales).

STUDY 2 Results

Psychometric Properties of the AMPS

Table 1 provides basic psychometric properties of the AMPS. The full 15-item scale scores showed strong internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.91) and item-total reliability (range=0.51–0.72). EFA results indicated that a three-factor (χ2=91.78, df=63, CFI=0.97, TLI=0.94, RMSEA=0.06 (CI=0.03–0.08), SRMR=0.04) structure had a better fit to the data than either a two-factor (χ2=137.73 (df=76), CFI=0.93, TLI=0.90, RMSEA=0.08 (CI=0.06–0.10), SRMR=0.05) or one-factor structure (χ2=204.65 (df=90), CFI=0.86, TLI=0.84, RMSEA=0.10 (CI=0.08–0.12), SRMR=0.07) and these fit statistics corroborated the scree plot. Items representing each of the three factors were assessed for content. Then, using theoretical insights garnered from our qualitative data and previous literature, we labeled the three factors decentering, positive emotion regulation, and negative emotion regulation. Conceptualization of the first of these factors was influenced by theoretical work by Teasdale and colleagues (Teasdale et al., 1995), who, using an Interacting Cognitive Subsystems framework, emphasized the role of decentering as a central means by which mindfulness exerts therapeutic effects. Conceptualization of the second factor was shaped by the upward spiral model (Garland et al., 2010) and the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory (Garland, Farb, Goldin, & Fredrickson, in press), which focus on the effects of mindfulness on positive emotion regulation through reappraisal and savoring. Lastly, conceptualization of the third factor was influenced both by classical theories of mindfulness meditation as a means of regulating negative emotions and stress by reducing arousal and inducing calm, as well as by psychological operationalizations of the role of mindfulness in regulating maladaptive behavior (Baer, 2003; Benson et al., 1974).

Table 1.

Psychometric characteristics of the AMPS items (Study 2), N=134

| Item | M | SD | I-T |

|---|---|---|---|

| I used mindfulness practice to… | |||

| 1. observe my thoughts in a non-attached manner. | 3.92 | .68 | .51 |

| 2. relax my body when I was tense. | 3.75 | .87 | .56 |

| 3. see that my thoughts were not necessarily true. | 3.64 | .90 | .56 |

| 4. enjoy the little things in life more fully. | 4.02 | .79 | .57 |

| 5. calm my emotions when I was upset. | 3.55 | .82 | .68 |

| 6. stop reacting to my negative impulses. | 3.36 | .89 | .61 |

| 7. see the positive side of difficult circumstances. | 3.45 | .88 | .72 |

| 8. reduce tension when I was stressed. | 3.76 | .81 | .58 |

| 9. realize that I can grow stronger from difficult circumstances. | 3.32 | 1.13 | .68 |

| 10. stop my unhelpful reactions to situations. | 3.51 | .85 | .58 |

| 11. be aware of and appreciating pleasant events. | 3.95 | .80 | .53 |

| 12. let go of unpleasant thoughts and feelings. | 3.63 | .73 | .61 |

| 13. realize that my thoughts were not facts. | 3.71 | .88 | .67 |

| 14. notice pleasant things in the face of difficult circumstances. | 3.47 | .88 | .66 |

| 15. see alternate views of a situation. | 3.70 | .89 | .68 |

Notes. See AMPS questionnaire and instructions in the appendix; Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 never to 5 almost always; I-T = item-total correlations

Table 2 provides a correlation matrix to determine the nomological validity of the AMPS test scores based on the Study 2 sample of practitioners. The AMPS total score and the three individual sub-factor scores were associated with all other constructs in the expected direction. The AMPS total score was positively correlated with both the MAAS (r=0.29, p<.01) and FMI (r=0.52, p<.01) measures of trait mindfulness. The AMPS was also positively correlated with meditation practice assessed on various time intervals (r range=0.29–0.31, p’s<.01). The AMPS correlated positively with the WHO-5 (r=0.48, p<.01) and PWI (r=0.45, p<.01), and inversely with DASS-21 (r=−0.48, p<.01). Correlation degree and significance remained relatively stable across the three factors of the AMPS. Furthermore, correlation directions (positive versus negative correlation) for AMPS paralleled those for MAAS. Of the three sub-factor scores, AMPS1 (decentering) was most strongly correlated with MAAS (r=0.30, p<.01), FMI (r=−0.50, p<.01), WHO (r=0.48, p<.01), and DASS-21 (r=−0.46, p<.01), while AMPS2 (positive emotional regulation) was most strongly correlated with PWI (r=−0.44, p<.01).

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis sequence of model structuring (Study 2), N=134

| Model Structure | χ2(df) | Δχ2testa | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 942.72 (105)*** | |||||

| One-factor model | 204.65 (90)*** | 49.20** | .86 | .84 | .10 | .07 |

| Three-factor model | 162.36 (87)*** | 14.01** | .91 | .89 | .08 | .06 |

| Three-factor model - R | 130.48 (85)*** | 15.94** | .95 | .93 | .06 | .06 |

Notes.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.0001;

normed χ2 difference test comparing the nested model to the one previous, where Δχ2= (χ2n − χ2n+1)/(dfn − dfn−1);

R = Revised three-factor model that allowed two correlated errors (to maintain factor integrity, errors were correlated only within their respective factor (e.g., items 2 & 8 and items 4 & 11))

Partial correlations adjusted for the MAAS and FMI provided evidence for incremental validity of the AMPS test scores. After adjusting for the MAAS, partial correlations were as follows between the AMPS and WHO (r=0.46, p<.01), PWI (r=0.38, p<.01), and DASS-21 (r=−0.41, p<.01). After adjusting for the FMI, partial correlations were as follows between the AMPS and WHO (r=0.28, p<.01), PWI (r=0.23, p=.01), and DASS-21 (r=−0.29, p<.01). AMPS scores explain additional variance in measures of psychological health that are not accounted for by previously established measures of trait mindfulness.

STUDY 3 Materials and Methods

Participants

Study 3 (N=180) participants were students, faculty, and staff who were enrolled and participating in the Mindful USC Program at the authors’ home institution. The majority of participants were female (71%). Regarding race and ethnicity, 58% were White, 20% Asian/Pacific Islander, 12% Hispanic/Latino, over 3% Black/African American, and 7% other.

Procedures

Mindful USC Program offers courses for free to students, faculty, and staff at the authors’ home institution. The courses are available through online registration and takes place for 90 minutes per week for five weeks. The course is led by a senior mindfulness meditation teacher with over 10 years of experience and provides foundational information and techniques for mindfulness meditation. Participants were contacted via email to complete online surveys at two time points: (1) within 10 days prior to the start of class and (2) within 10 days following the end of the course. Participants were contacted up to 4 times to complete each survey. Study 3 procedures were approved by the IRB of the authors’ home institution.

Measures

In Study 3, we measured AMPS within 10 days following completion of the Mindful USC course. Because the primary purpose of a process measure is to examine processes learned and experienced from a specific intervention, the AMPS was only measured following participation in the intervention (Das, Sarnath, Nakayama, & Janzen, 2013; Godfrey, Chalder, Ridsdale, Seed, & Ogden, 2007). In other words, it would have been meaningless to assess intervention processes before participants had engaged in a MBI, so measurement of the AMPS is not recommended until at least several weeks of intervention have elapsed. As such, the scoring of AMPS would serve as a predictor of the desired health outcome (i.e., reduction in perceived stress). All AMPS items were identical to those measured in Study 2. As in Study 2, we calculated one total AMPS score and three sub-factor scores pertaining to the three factors identified in the EFA. The six-item version of MAAS (Black et al., 2012) was once again measured to quantify state-like mindfulness in the Mindful USC sample. Additionally, we measured stress using a four-item version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Items ranged from 0--never to 4--very often and were summed. High scores indicated high perceived stress. We measured generalized anxiety using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006). Possible responses ranged from 0--not at all sure to 3--nearly every day. High total scores corresponded with high levels of anxiety. We measured depression using the short Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale (CESD-10) (Santor & Coyne, 1997) across ten items, with responses ranging from 0--rarely or none of the time to 3--all of the time. High total scores indicated high levels of depression.

Statistical Analysis

We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the AMPS in a separate sample using factor structures identified in EFA. To evaluate model fit, we calculated the χ2 goodness-of-fit, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. We also performed χ2 tests of comparison to nested models. Lagrange Multiplier tests were used to identify additional parameters that would improve model fit. We calculated internal consistency reliability with Cronbach’s α and evaluated nomological validity by testing correlations between AMPS, its three sub-factor scores, and related psychometric scale scores—MAAS, PSS-4, GAD-7, and CESD-10—all measured upon completion of the Mindful USC course. Conceptually, AMPS and its sub-factor scores should be positively correlated with MAAS and negatively correlated with the PSS-4, GAD-7, and CES-D 10.

STUDY 3 Results

Based on data from the second, replication sample, results from CFA of the one-factor model and for the three-factor model once again indicated that the three-factor model (χ2=265.86 (df=87), CFI=0.89, TLI=0.87, RMSEA=0.11 (CI=0.09–0.12), SRMR=0.06) had better fit than the one-factor model (χ2=343.58 (df=90), CFI=0.85, TLI=0.82, RMSEA=0.13 (CI=0.11–0.14), SRMR=0.06) (Table 4). Fit indices for the three-factor model in this second sample were at the border of our acceptable criteria. In both models, all items loaded onto their respective factors with loadings of 0.60 or higher. The internal consistency for the overall scale was very good (Cronbach’s α=0.94).

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis of nested and baselines models (Study 3), N=180

| Model Structure | χ2(df) | Δχ2 testa | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 1776.94 (105)*** | |||||

| One-factor model | 343.58 (90)*** | 95.56*** | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Three-factor model | 265.86 (87)*** | 25.91*** | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Three-factor model - R | 238.53 (86) *** | 27.33*** | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

Notes.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.0001;

normed χ2 difference test comparing the nested model to the one previous, where Δχ2= (χ2n − χ2n+1)/(dfn − dfn−1);

R = Revised three-factor model that allowed one correlated error (to maintain factor integrity, errors were correlated only within their respective factor (i.e., items 3 & 13)

The AMPS total score was positively correlated with MAAS (r=0.35, p<.001) and negatively correlated with PSS-4 (r=−0.40, p<.001), GAD-7 (r=−0.37, p<.001), and CESD-10 (r=−0.36, p<.001). MAAS was correlated with PSS-4 (r=−0.39, p<.001), GAD-7 (r=−0.42, p<.001), and CESD-10 (r=−0.47, p<.001) in the same directions as AMPS. The AMPS sub-factor scores were associated with these constructs in the same direction as the total score. Generally, the strength of correlation and significance were consistent across the three sub-factor scores. Of the three sub-factor scores, AMPS2 (positive emotional regulation) was most strongly correlated with CESD-10 (r=−0.38, p<.001), while AMPS3 (negative emotional regulation) was most strongly correlated with PSS-4 (r=−0.40, p<.001) and GAD-7 (r=−0.37, p<.001).

Discussion

Informed by prior theoretical conceptualizations of mindfulness and the indigenous experiences of mindfulness practitioners, we employed a mixed qualitative-quantitative methodology to generate the AMPS as a MBI process measure. This instrument was designed to assess how individuals who participate in a MBI, and mindfulness practice more generally, apply mindfulness to cope with stress in their daily lives. In that regard, as a process measure the AMPS may be well-suited for use in MBI trials, and can be used to ascertain to what extent the application of mindfulness towards various therapeutic processes (e.g., decentering, positive emotion regulation, negative emotion regulation) predicts a range of clinical outcomes (e.g., improvements in well-being, substance use, pain severity, depressive symptoms, etc.). Some of the skills described in the AMPS may also be developed by other psychotherapeutic approaches, as there are a number of shared goals between MBIss and psychotherapies (Herbert & Forman, 2011). However, each item described by the AMPS reflects a different skill trained in MBI programs, as well as processes toward achieving specific mindfulness characteristics that have been previously described in dispositional mindfulness scales (Baer et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Cardaciotto et al., 2008; Lau et al., 2006; Walach et al., 2006). Though the AMPS may tap MBI-specific processes, it may also be useful for measuring change processes in other therapies with elements in common with MBIs, such acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes et al., 2006). It should also be noted that the AMPS is not a general measure of mindful dispositionality independent of mindfulness practice.

Previously, Erisman and Roemer (2012) developed the 7-item Mindfulness Process Questionnaire (MPQ) for a similar purpose as the AMPS. The MPQ captures situations where a person might move from a less mindful state—described in the scale as “uncertainties of life”—to a more mindful state, with a particular emphasis on adjusting from rumination to present awareness and acceptance. The AMPS distinguishes itself from the MPQ in the way it contextualizes the application of mindfulness. Rather than describing how mindfulness moves individuals from mindlessness to mindfulness, each AMPS item is intended to describe the use of mindfulness to cope with daily stressors, adverse life events, and unpleasant states through decentering, positive emotional regulation, and negative emotional regulation. These three factors underlying the AMPS are consistent with previous research and theory.

The first factor, Decentering, was comprised of items reflecting the use of mindfulness to cope by disidentifying from negative thoughts and feelings and by regarding one’s mental experience as lacking absolute veridicality (Teasdale et al., 1995). This mindfulness strategy has been shown to reduce depressive relapse and may promote cognitive flexibility (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009; Holas & Jankowski, 2013; Teasdale et al., 2002). By recognizing that thoughts are not veridical truths and that the self is not identical with mental experience, a mindfulness practitioner may make more accurate situational appraisals with less bias due to cognitive distortions (e.g., catastrophizing). Indeed, mindfulness has been conceptualized as awareness without emotional distortions and reactivity (Bishop et al., 2004). Emotional distortions and reactions bias perception, leading to exaggerated, overestimated appraisals of threat and underestimations of self-efficacy, thereby resulting in increased stress (Mathews & MacLeod, 2005). In contrast, decentering may enable a practitioner to view his or her circumstances more clearly and adaptively, and to more accurately assess his or her ability to cope with present challenges (Garland, 2007).

The second factor of the AMPS, Positive Emotion Regulation, is comprised of items tapping the use of mindfulness to cope by refocusing attention onto positive emotional experience and positively reappraising adverse life events. This factor is consistent with modern psychological theories linking mindfulness with the generation of positive affective states, and endorsements by Buddhist scholars to use mindfulness to promote the “cultivation of happiness, the genuine inner transformation by deliberately selecting and focusing on positive mental states” (Garland et al., 2010; Lama, 1998). Beyond the intent of mindfulness meditation as producing an austere, neutral state of bare attention, mindfulness practice has also been classically described in some contemplative traditions as a means of generating decidedly positive or pleasurable emotions (Namgyal, 2006). Empirical data demonstrate that mindfulness training exerts significant effects on positive affective processes by augmenting savoring of pleasant events, improving memory for positive information, and promoting positive reappraisal (Garland, Farb, Goldin, & Fredrickson, 2015; Garland et al., 2011; Geschwind et al., 2011; Nyklícek & Kuijpers, 2008; Orzech, Shapiro, Brown, & McKay, 2009; Roberts-Wolfe, Sacchet, Hastings, Roth, & Britton, 2012; Troy et al., 2013; Zautra et al., 2008). By attending to the positive aspects of experience in daily life, a mindfulness practitioner may maintain the positive affective balance that has been shown to be essential to psychological flourishing (Garland et al., 2010).

The third factor, Negative Emotion Regulation, was comprised of items reflecting the use of mindfulness to cope by reducing emotional distress. Extensive empirical and theoretical work has established that mindfulness can improve regulation of negative emotions (for a review, see (Hölzel et al., 2011)). Items representing this AMPS factor tap the use of mindfulness to calm emotional upset and inhibit negative emotional reactions. Mindfulness meditation has been classically conceptualized as reducing distress via evocation of a relaxation response (Benson et al., 1974). Indeed, mindfulness training induces patterns of parasympathetic nervous system activation that are reflective of relaxation and calm (Jain et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2007). However, mindfulness meditation has been shown to produce significantly different cardiovascular and autonomic effects than relaxation training, as well as generally superior effects on stress and negative emotion regulation when compared to relaxation therapy (Ditto, Eclache, & Goldman, 2006; Sedlmeier et al., 2012). Thus, mindfulness practitioners may also cope with stress by adopting an attitude of nonreactivity toward negative emotions, allowing them to arise and abate without reacting to them. Mindfulness practice has been shown to be associated with increased nonreactivity, which in turn predicts decreased negative emotional reactions (Carmody & Baer, 2008). In the face of negative emotions triggered by the encounter with a stressor, practitioners may use mindfulness to generate a state of calm or equanimity, and thereby restrain the impulse to react negatively when under stress.

Therefore, in addition to offering utility as a standalone process measure for researchers attempting to quantify applications of mindfulness practice in daily life, AMPS can also be used in parallel with current measures of mindfulness as a trait-like construct. Furthermore, examination of the three AMPS subscores—decentering, positive emotion regulation, and negative emotion regulation—can serve to elucidate which types of applied mindful processes are most predictive of mindfulness as a single construct (i.e., MAAS) (Brown & Ryan, 2003) or its different facets such as those identified by the FFMQ (e.g., observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudging, and nonreacting) (Baer et al., 2006). Across our three sub-factor scores—decentering, positive emotional regulation, and negative emotional regulation—tests of correlation showed variation in strength of correlation with related psychometric constructs. This suggests that each sub-factor score may have different predictive utility for different psychometric constructs. Furthermore, researchers can use the process measure to evaluate the impact of different applied mindfulness practices on other health outcomes, as well as the degree to which mindfulness as a construct mediates these effects.

Limitations and Conclusions

Although employing qualitative methods provided rich information necessary for the development of the AMPS, this approach posed some limitations. Qualitative investigations have been criticized for their lack of generalizability (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004); however, this method uses systematic description and categorization of qualitative, subjective reports of perceptual experience to develop generalizations that pertain to human experiences on the whole (Ercikan & Roth, 2006). Future statistical tests of the AMPS with larger and more diverse sample sizes are needed to confirm the external validity of study findings collected with this instrument. For this reason, strength of correlation between each AMPS sub-factor and each related psychometric scale determined in this study should be confirmed in other samples. The scale is not meant for use in non-practitioners. In order to test sensitivity to change, the AMPS will also need to be tested on larger samples of participants who are participating in MBIs, or who have an ongoing mindfulness practice, and determine if the AMPS scores change over the course of a MBI. Use of the scale for this purpose should entail first measuring AMPS at the midpoint of the intervention (i.e., at week 4 of an 8-week MBI) followed by final measurement the end of the intervention (i.e., at week 8 of an 8-week MBI). In addition, although we outline three domains for how mindfulness may be applied to cope with daily stressors, there may be other mindfulness domains untapped by the AMPS that are central to mindfulness practice. Lastly, to determine the utility of the scale as a process measure for clinical trials of MBIs, the AMPS should be used by future researchers to assess how mindfulness practices are used by participants to cope with stressors and hassles in everyday life, and AMPS scores can then be correlated with study outcomes.

Table 3.

Zero-order correlation matrix to interpret nomological validity of AMPS scores (Study 2), N=134

| AMP S-T | AMP S1 | AMP S2 | AMP S3 | Med Mnt | Med Day | Med Hrs | MA AS | FM I | WH O | PW I | DAS S-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPS-T | 1 | |||||||||||

| AMPS1 | .90** | 1 | ||||||||||

| AMPS2 | .90** | .69** | 1 | |||||||||

| AMPS3 | .84** | .64** | .65** | 1 | ||||||||

| MedYrs | .31** | .34** | .21* | .24** | 1 | |||||||

| MedDay | .27** | .21* | .23** | .21* | .25** | 1 | ||||||

| MedHrs | .29** | .30** | .20* | .21* | .20* | .60** | 1 | |||||

| MAAS | .29** | .30** | .27** | .25** | .39** | .20* | .25** | 1 | ||||

| FMI | .52** | .50** | .48** | .44** | .34** | .29** | .29** | .59** | 1 | |||

| WHO | .48** | .44** | .42** | .30** | .08 | .20* | .20* | .23* | .56** | 1 | ||

| PWI | .45** | .37** | .44** | .28** | .27** | .10 | .16 | .35** | .52** | .56** | 1 | |

| DAS | - | - | - | - | - | −.12 | −.22* | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| S-21 | .48** | .46** | .36** | .23** | .27** | .40** | .52** | .57** | .62** |

p<.01,

p<.05;

AMPS-T = Applied Mindfulness Process Scale-Total score; AMPS1 = decentering subfactor ; AMPS2 = positive emotion regulation subfactor; AMPS3 = negative emotion regulation subfactor; MedYrs = How many years have you practiced mindfulness meditation practice? (response options from 1 <1 year to 31 30 or more years); MedDay = How many days per month do you practice mindfulness meditation? (response options from 1 <1 day to 31 all 30 days); MedHrs = How many hours per month do you practice mindfulness meditation? (response options in 5 hour increments from 1 less than 1 hour to 9 51 or more hours); MAAS = Mindful Attention Awareness; FMI = Freiberg Mindfulness Inventory; WHO-5 = WHO Well Being Index; PWI = Personal Wellbeing Index; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety, Stress-21

Table 5.

Zero-order correlation matrix to interpret nomological validity of AMPS scores (Study 3), N=180

| AMPS-T | AMPS1 | AMPS2 | AMPS3 | MAAS | PSS-4 | GAD-7 | CESD-10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPS-T | 1 | |||||||

| AMPS1 | .90*** | 1 | ||||||

| AMPS2 | .91*** | .72*** | 1 | |||||

| AMPS3 | .91*** | .73*** | .75*** | 1 | ||||

| MAAS | .35*** | .28*** | .35*** | .33*** | 1 | |||

| PSS-4 | −.40*** | −.31*** | −.37*** | −.40*** | −.39*** | 1 | ||

| GAD-7 | −.37*** | −.30*** | −.34*** | −.37*** | −.42*** | .59*** | 1 | |

| CESD-10 | −.36*** | −.27*** | −.38*** | −.33*** | −.47*** | .66*** | .72*** | 1 |

p<0.001;

AMPS-T = Applied Mindfulness Process Scale-Total score; AMPS1 = decentering subfactor ; AMPS2 = positive emotion regulation subfactor ; AMPS3 = negative emotion regulation subfactor; MAAS = Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; PSS-4 = Perceived Stress Scale-4; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; CESD-10 = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-10

Highlights.

Qualitative inquiry yielded a mindfulness process measure comprised of 15 items.

Exploratory factor analysis and theory yielded three factors for the scale.

Correlations with related psychometric scales confirmed nomological validity.

Confirmatory factor analysis verified good model fit with three-factors.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA032517 to E.G.) and the National Cancer Institute (T32 CA09492 to D.B.).

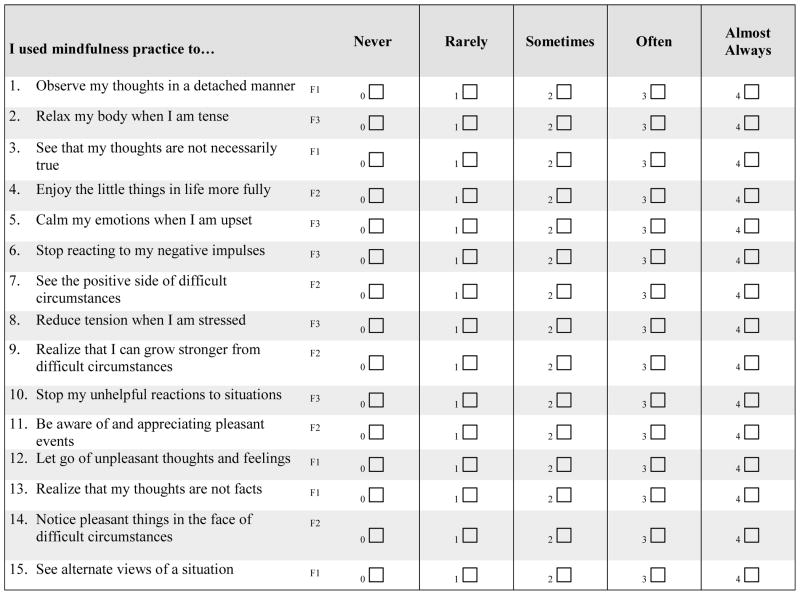

Appendix. Mindfulness Applied Practice Scale (AMPS)

Everyone gets confronted with negative or stressful events in daily life, and people who practice mindfulness cope with these events in different ways. Please indicate how often you have used mindfulness to cope in each of these ways (if at all) for the period of the last week (past 7 days).

Notes. F1 = Factor 1 (Decentering), F2 = Factor 2 (Positive Emotion Regulation), F3 = Factor 3 (Negative Emotion Regulation)

Instructions for administration: We suggest that the AMPS process measure be administered one or more times during the course of the intervention when the participant has become familiar with the practice (e.g., at week 4 - the intervention mid-point, at week 8 - the end of the MBI).

Instructions for scoring: (1) sum each factor individually to obtain score ranging from 0–20, and/or (2) sum all 15 items to obtain score ranging from 0–60.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors (M.L., D.B., E.G.) indicate no conflict of interest or financial gain for publishing this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agee J. Developing qualitative research questions: A reflective process. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2009;22(4):431–447. doi: 10.1080/09518390902736512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using Self-Report Assessment Methods to Explore Facets of Mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson H, Beary JF, Carol MP. The relaxation reponse. Psychiatry. 1974;37(1):37. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1974.11023785. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4810622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, Velting D. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS. Mindfulness-based interventions: An antidote to suffering in the context of substance use, misuse, and addiction. Substance Use & Misuse. 2014;49(5):487–491. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.860749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS, Milam J, Sussman S. Sitting-meditation interventions among youth: a review of treatment efficacy. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e532–541. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS, Sussman S, Johnson CA, Milam J. Psychometric assessment of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS) among Chinese adolescents. Assessment. 2012;19(1):42–52. doi: 10.1177/1073191111415365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, Cuijpers P. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;68(6):539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton WB, Lindahl JR, Cahn BR, Davis JH, Goldman RE. Awakening is not a metaphor: the effects of Buddhist meditation practices on basic wakefulness. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2014;1307(1):64–81. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardaciotto L, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Moitra E, Farrow V. The Assessment of Present-Moment Awareness and Acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment. 2008;15(2):204–223. doi: 10.1177/1073191107311467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Gullone E, Allen NB. Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(6):560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A. The Difficulty of Defining Mindfulness: Current Thought and Critical Issues. Mindfulness. 2013;4(3):255–268. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0123-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Anselmi R, Serretti A. Psychological Mechanisms of Mindfulness-Based Interventions: What Do We Know? Holistic nursing practice. 2014;28(2):124–148. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Malinowski P. Mindfulness-based approaches: are they all the same? Journal of clinical psychology. 2011;67(4):404–424. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY) 2009;15(5):593–600. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of health and social behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das JP, Sarnath J, Nakayama T, Janzen T. Comparison of Cognitive Process Measures Across Three Cultural Samples: Some Surprises. Psychological Studies. 2013;58(4):386–394. doi: 10.1007/s12646-013-0220-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vibe M, Bjørndal A, Tipton E, Hammerstrøm KT, Kowalski K. Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life, and social functioning in adults. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2012;3:1–127. Retrieved from http://campbellcollaboration.org/lib/download/1767/ [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and applications. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ditto B, Eclache M, Goldman N. Short-term autonomic and cardiovascular effects of mindfulness body scan meditation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;32(3):227–234. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3203_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercikan K, Roth WM. What good is polarizing research into qualitative and quantitative? Educational Researcher. 2006;35(5):14–23. doi: 10.3102/0013189X035005014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erisman SM, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the process of mindfulness. Mindfulness. 2012;3(1):30–43. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0078-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman G, Hayes A, Kumar S, Greeson J, Laurenceau JP. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29(3):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s10862-006-9035-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(8):1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist. 2000;55(6):647. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL. The meaning of mindfulness: A second-order cybernetics of stress, metacognition, and coping. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2007;12(1):15–30. doi: 10.1177/1533210107301740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Farb NAS, Goldin P, Fredrickson BL. Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry. 2015 doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294. in print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, Penn DL. Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotional dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(7):849–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Effects of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement on reward responsiveness and opioid cue-reactivity. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231(16):3229–3238. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3504-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Neurophysiological evidence for remediation of reward processing deficits in chronic pain and opioid misuse following treatment with Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement: exploratory ERP findings from a pilot RCT. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;38(2):327. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9607-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord S, Park J. The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2009;5(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Fredrickson BL. Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: An upward spiral process. Mindfulness. 2011;2(1):59–67. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0043-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, Kelly A, Williams JM, Howard MO. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: Results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(3):448. doi: 10.1037/a0035798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N, Peeters F, Drukker M, van Os J, Wichers M. Mindfulness training increases momentary positive emotions and reward experience in adults vulnerable to depression: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(5):618. doi: 10.1037/a0024595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey E, Chalder T, Ridsdale L, Seed P, Ogden J. Investigating the ‘active ingredients’ of cognitive behaviour therapy and counselling for patients with chronic fatigue in primary care: developing a new process measure to assess treatment fidelity and predict outcome. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46(3):253–272. doi: 10.1348/014466506X147420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Van Dam NT. Mindfulness, by any other name…: trials and tribulations of sati in western psychology and science. Contemporary Buddhism. 2011;12(1):219–239. doi: 10.1080/14639947.2011.564841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harry B, Sturges KM, Klingner JK. Mapping the process: An exemplar of process and challenge in grounded theory analysis. Educational Researcher. 2005;34(2):3–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X034002003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44(2):227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert JD, Forman EM. Acceptance and Mindfulness in Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Understanding and Applying the New Therapies. Hoboken, N.J: J. Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holas P, Jankowski T. A cognitive perspective on mindfulness. International Journal of Psychology. 2013;48(3):232–243. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.658056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(6):537–559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Wellbeing Group. Personal wellbeing index. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/wellbeing_index.htm.

- Jain S, Shapiro S, Swanick S, Roesch S, Mills P, Bell I, Schwartz GR. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: Effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33(1):11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez SS, Niles BL, Park CL. A mindfulness model of affect regulation and depressive symptoms: Positive emotions, mood regulation expectancies, and self-acceptance as regulatory mechanisms. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49(6):645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher. 2004;33(7):14–26. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033007014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1982;4(1):33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls N, Sauer S, Walach H. Facets of mindfulness: Results of an online study investigating the Freiburg mindfulness inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46(2):224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lama D. The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living. Manhattan, NY: Penguin Group (USA) Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lau MA, Bishop SR, Segal ZV, Buis T, Anderson ND, Carlson L, Devins G. The Toronto mindfulness scale: Development and validation. Journal of clinical psychology. 2006;62(12):1445–1467. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company LLC; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namgyal DT. Mahamudra: The Moonlight--Quintessence of Mind and Meditation. 2. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nyklícek I, Kuijpers KF. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological well-being and quality of life: Is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35(3):331–340. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly GA, Cook L, Spruijt-Metz D, Black DS. Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: A literature review. Obesity Reviews. 2014;15(6):453–461. doi: 10.1111/obr.12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzech KM, Shapiro SL, Brown KW, McKay M. Intensive mindfulness training-related changes in cognitive and emotional experience. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2009;4(3):212–222. doi: 10.1080/17439760902819394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research: Challenges and Rewards. Vol. 36. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Wolfe D, Sacchet M, Hastings E, Roth H, Britton W. Mindfulness training alters emotional memory recall compared to active controls: support for an emotional information processing model of mindfulness. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:15. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santor DA, Coyne JC. Shortening the CES-D to Improve Its Ability to Detect Cases of Depression. Psychological assessment. 1997;9(3):233–243. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlmeier P, Eberth J, Schwarz M, Zimmermann D, Haarig F, Jaeger S, Kunze S. The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(6):1139–1171. doi: 10.1037/a0028168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SeyedAlinaghi S, Jam S, Foroughi M, Imani A, Mohraz M, Djavid GE, Black DS. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction delivered to human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients in Iran: effects on CD4+ T lymphocyte count and medical and psychological symptoms. Psychosomatic medicine. 2012;74(6):620–627. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31825abfaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The gad-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YY, Ma Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Feng S, Lu Q, Fan M. Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(43):17152–17156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707678104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, Segal ZV. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: Empirical evidence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):275–287. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Segal Z, Williams JMG. How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33(1):25–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)E0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AS, Shallcross AJ, Davis TS, Mauss IB. History of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is associated with increased cognitive reappraisal ability. Mindfulness. 2013;4(3):213–222. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NT, Hobkirk AL, Danoff-Burg S, Earleywine M. Mind Your Words: Positive and Negative Items Create Method Effects on the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Assessment. 2012;19(2):198–204. doi: 10.1177/1073191112438743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness -- The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40(8):1543–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. 1. New York: Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Psychiatric research unit, WHO collaborating center for mental health. Frederiksborg General Hospital; 1998. Retrieved from http://www.cure4you.dk/354/WHO-5_English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Sage Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley ME, Bowen GL, Bowen NK. Cognitive pretesting and the developmental validity of child self-report instruments: Theory and applications. Research on Social Work Practice. 2004;14(3):191–200. doi: 10.1177/1049731503257882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW, Nicassario P, Tennen H, Finan P, Irwin MR. Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(3):408–421. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]