Abstract

This research examined the relation between early adolescent aggression and parenting practices in an urban, predominately African American sample. Sixth graders (N = 209) completed questionnaires about their overt and relational aggressive behaviors and perceptions of caregivers’ parenting practices. Findings indicated that moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions at Time 1 were associated with a lower likelihood of overt aggression at Time 2. Furthermore, findings suggest that when caregivers’ support and knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts were relatively low or when caregivers’ exerted high psychological control, moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions protected early adolescents against engagement in both overt and relational aggression. The implications of the findings for schools and other youth violence prevention settings are discussed.

Keywords: youth aggression, parenting, low-income schools, urban, minority population

Aggressive behavior in childhood and early adolescence places many youth on a trajectory that involves later engagement in delinquent behaviors, including more serious forms of violence (Loeber & Hay, 1997; Petras et al., 2004). Youth from the most disadvantaged urban communities may be at a higher risk for aggression involvement compared to youth from communities with greater resources and less exposure to violence (Beyers, Loeber, Wikstrom, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2001; Gorman-Smith, 2003). Research suggests that disadvantaged urban African American communities provide a social context that exacerbates risk for aggression including exposure to community and school violence, weak mechanisms of social control, and scarce social capital (e.g., Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994; Bruce, 2004; Decoster, Heimer, & Wittrock, 2006). Particular parenting practices may serve to buffer the influence of the myriad environmental influences that increase risk for aggression in these communities.

Although numerous studies on parenting practices and adolescent aggression include urban African American study participants, few researchers stratify findings by race, ethnicity, and/or socioeconomic status. Further, while responsive and demanding parenting practices such as support and monitoring have been widely studied, the influence of parent psychological control and parental expectations about adolescent aggression has not been extensively examined in urban, low-income predominately African American samples. Many youth violence prevention interventions and programs include parenting components. Thus, a better understanding of how parenting behavior contributes to early adolescent aggression may facilitate the development of effective multitiered violence prevention interventions in urban communities with high levels of violence.

Responsive and Demanding Parenting Practices

Responsive and demanding parenting practices have been shown to be protective against a wide range of adolescent problem behaviors (Barber, 1996; Simons-Morton, Chen, Hand, & Haynie, 2008; Steinberg, Lamborn, Darling, Mounts, & Dornbusch, 1994). There is strong evidence that responsive parenting practices such as parent support, involvement, and regard, foster positive adolescent development and lower risk for maladaptive outcomes. For example, aggression is inversely related to parental responsiveness constructs in multiethnic samples (Jackson & Foshee, 1998; Simons-Morton, Hartos, & Haynie, 2004). Likewise, parent support is correlated with lower levels of youth delinquency (Barber, Olsen, & Shagle, 1994; Bean, Barber, & Crane, 2006; Pittman & Chase-Lansdale, 2001) and externalizing problems (Prelow, Bowman, Weaver, & Scott, 2007).

Demanding parenting practices such as monitoring and knowledge, have also demonstrated protective potential in diverse samples (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Laird, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2003; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005). Numerous studies have shown that adolescents are less likely to engage in aggressive behaviors when parents provide high levels of monitoring or have knowledge of their adolescents’ whereabouts (e.g., Richards, Miller, O’Donnell, Wasserman, & Colder, 2004; Simons-Morton et al., 2004; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005; Wright & Fitzpatrick, 2006). Although some researchers have conceptualized monitoring and knowledge as demanding parenting, some research suggests that knowledge may be associated with the parent-child relationship. Responsive parenting may enhance the parent-child relationship and, consequently, foster an adolescent’s free, willing disclosure of information (i.e., knowledge) about his or her whereabouts to the parents (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Kerr, Stattin, Biesecker, & Ferrer-Wreder, 2002; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Although monitoring is often assessed using items that measure knowledge, few studies have attempted to assess the extent to which measures of parent knowledge are distinct from measures of responsiveness like support.

Parent Psychological Control

Parent psychological control is parenting behavior that impedes the development of a child’s independence and self-worth through restrictiveness, invalidation of a child’s feelings, and love withdrawal. The literature on psychological control and problem behaviors, including aggression, remains scant. In general, this research indicates that psychological control is associated with higher delinquency and related problem behaviors (Barber, 1996; Barber et al., 1994; Loukas, Paulos, & Robinson, 2005), while greater levels of autonomy, which is more or less the opposite of psychological control, mediates the relationship between parental monitoring and adolescent conduct problems (Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005). Most of these studies included samples that were primarily White, middle-class adolescents; few researchers have examined the role of psychological control in predicting adolescent aggression in African American samples.

Albeit limited, the existing research on parent psychological control among African Americans adolescents provides some evidence that its influence may vary by race or ethnicity (Bean et al., 2006; Mason, Cauce, Gonzales, & Hiraga, 1996). Due to a host of methodological limitations, the relations between parent psychological control and adolescent problem behaviors, like aggression, among African American youth is still poorly understood. For example, the African American samples in these studies were geographically and economically heterogeneous. Thus, it is uncertain whether findings were driven by race or ethnicity related parenting norms or contextual variations related to family socioeconomic status and/or exposure to community and school violence.

Parental Expectations

Consistent and clear parental expectations may also influence aggression and other problem behavior outcomes. Parental expectations have been shown to protect adolescents against aggression and substance use progress (e.g., Simons-Morton et al., 2004; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2005). Few studies have examined the relations between parental expectations specific to aggression involvement and adolescent aggression outcomes. In two multiethnic studies, middle school students who perceived that their parent wanted them to fight in a conflict situation reported engaging in greater levels of fighting behavior (Malek, Chang, & Davis, 1998; Orpinas, Murray, & Kelder, 1999). Parents who communicate expectations for aggressive solutions to conflict may intend to protect their children from recurrent victimization by emphasizing self-defense and similar strategies. Some research suggests that residents of urban communities with high violence may perceive that youth are highly vulnerable to victimization due to peer norms that emphasize using aggression to get and maintain respect (Stewart, Schreck, & Simons, 2006). Thus, the role of parental expectations for both aggressive solutions and peaceful solutions to aggression is particularly relevant to urban parents raising adolescents exposed to pervasive community and school violence.

Interplay Between Parental Expectations and Other Parenting Practices

Parental expectations for aggressive solutions or peaceful solutions to aggression may be least effective in the context of high psychological control. Parents’ exertion of psychological control may foster conflict and hostile parent-child interactions and thus obstruct the development of a strong parent-child relationship. In contrast, parental expectations may be most effective in the context of a high quality parent-child relationship characterized by responsive and supportive parenting. A parent who is supportive may facilitate a child’s willingness to meet his or her parents’ expectations for aggressive solutions or peaceful solutions to aggression. Parent support, as previously discussed, may also facilitate parent knowledge about their child’s whereabouts (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Kerr et al., 2002; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Because parent knowledge may be the indicator of a parent-child relationship characterized by high support, parent communication of expectations may also be more effective when parents have high levels of knowledge.

Study Purpose

The present study examined the relation between perceived parenting practices and aggression among youth who lived in neighborhoods and attended schools characterized by high levels of violence. The first aim of this study was to examine the extent to which each parenting variable (expectations for peaceful solutions to aggression, expectations for aggressive solutions to aggression, support, knowledge, and psychological control) directly predicted early adolescent aggression. Controlling for Time 1 adolescent aggression, we hypothesized that parental expectations for peaceful solutions, support, and knowledge would be negatively associated with adolescent aggression at Time 2, and parental expectations for aggressive solutions would be positively associated with adolescent aggression at Time 2. Though the findings regarding psychological control in African American adolescent samples have been equivocal, we also expected that psychological control would be positively associated with aggression at Time 2. Given that parent support, knowledge, and psychological control are indicators of parent-child relationship quality, the level of support, knowledge, and psychological control provided to the adolescent may alter the effectiveness of parental expectations. Thus, the second aim was to examine the interactions between expectations and support, knowledge, and psychological control on early adolescent aggression. Controlling for Time 1 adolescent aggression, we expected that support, knowledge, and psychological control at Time 1 would each independently moderate the relation between parental expectations at Time 1 and adolescent aggression at Time 2.

METHOD

Sample

Sixth graders and their parents or guardians were recruited from two middle schools in a large northeastern city. Both schools were on probation for the federal designation of being “persistently dangerous,” a label based on the numbers of student expulsions and suspensions for violent offenses (Maryland State Department of Education, 2005). Recruitment eligibility criteria included the following: (a) first-time sixth grader and (b) not in self-contained special education classes. Of the students eligible to participate, 274 (58%) returned forms indicating parental consent to participate, a response rate consistent with that found in other school-based studies involving minority adolescents (e.g., Murry, Berkel, Brody, Gibbons, & Gibbons, 2007). A combination of transfers, absences, and suspensions resulted in 213 students completing baseline and follow-up surveys. Four students were excluded from this study due to an excessive level of missing data. Therefore, the current study sample consisted of 209 sixth graders. The majority of the sample was male (54%) and the mean age was 12 years. The sample was 96% African American and 13% reported Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Sixty-two percent lived in households with one biological parent and at least one other adult (including a second biological parent), 29% of participants lived in single-parent households (one biological parent), and 9% lived in other household configurations (e.g., households headed by two grandparents).

Procedure

This study is an analysis of data from a randomized, controlled trial testing the impact of a 10-week school-based violence prevention curriculum on early adolescent aggressive behaviors. The Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins University and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) approved this study. Overall, parent engagement in the intervention was designed to encourage parents to reinforce the goals of the youth intervention (which were for students to engage in problem solving and exercise self control rather than responding to aggression with aggressive behavior of their own), rather than to change overt parenting behaviors. Data were collected in the sixth grade at pretest and posttest during 2004—2005 academic school year. Follow-up data were collected in the seventh grade, but these data were not included in these analyses due to extensive loss of students to follow up.

Information about the study and parent consent forms were distributed to sixth-grade students by homeroom teachers at the beginning of the 2004–2005 academic year. Study staff presented at school assemblies and visited the classrooms several times during the recruitment period to encourage participation and return of consent forms. Study staff also presented at the schools’ back-to-school nights, PTA meetings, and similar programs, but these were generally poorly attended. Classroom teachers who managed to get at least 80% of signed consent forms returned (either consenting or refusing) were provided with an individual incentive valued at $20, and the homeroom class was provided a donut breakfast.

Youth who returned signed consent forms indicating parental consent to participate in the study were randomized to either the intervention or control condition. In a second step, participants were randomly assigned to participate in the study during either the fall or spring semester. Participating youth signed assent forms prior to completing the baseline survey in either the fall (October) or the winter (January). Youth completed follow-up surveys postintervention approximately three months later in either the month of February or the month of May. Students who were unable to read the survey were not eligible for the study. Youth received incentives for completing the survey including t-shirts and pens.

Measures

Dependent variables

Aggressive behavior was measured using overt aggression and relational aggression indices. The overt and relational aggression indices were adapted from the Aggression Scale used by Orpinas and colleagues (Orpinas & Frankowski, 2001). This adapted measure of aggressive behavior included five questions that assessed how frequently the youth was aggressive at home or in the neighborhood in the last 30 days. The response options ranged from “never” to “5 or more times,” and were recoded into two binary categories due to their highly skewed distribution. The indices were created as a sum of the relevant items. Overt aggression was coded as not aggressive = 0 or aggressive = 1 if the respondent endorsed one or more times on any of three questions regarding overtly aggressive behaviors (e.g., “Push, shove, slap, or kick another student?,” “Hurt someone on purpose?,” “Threaten to hit or hurt another student?”). Relational aggression was coded as not aggressive = 0 or aggressive = 1 if the respondent endorsed one or more times on either of two questions about relationally aggressive behaviors (e.g., “Spread rumors or gossip?,” “Say or do something just to make someone mad?”).

Independent variables

Early adolescents’ perceptions of parental expectations about fighting were measured using an adapted version of the Parental Support for Fighting scale (Orpinas et al., 1999). The adapted measure included 10 items from the original scale, and an additional 2 items developed for the larger aggression study. Five of the scale items reflect statements about parental expectations for peaceful solutions to aggression (e.g., “Ignore someone if he or she calls me a name,” “Tell a teacher or another adult if someone asks me to fight”). Seven items reflect parental expectations for aggressive solutions to aggression (e.g., “Stay and fight instead of walking away so I won’t be a coward or a ‘chicken’,” “Stay and fight so I won’t get ‘picked on’ even more”). The scale has a 10-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree).

Participants’ perceptions of parent supportive behavior was measured using the 10-item Acceptance subscale from the revised Child Report of Parent Behavior Inventory (Barber, 1996). Items asked about having a parent the participant perceived as supportive (I have a parent/guardian who: “Is easy to talk to,” “gives me care and attention”). Participants responded on a five-point response scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Participants’ perceptions of parent knowledge were measured using the five-item monitoring scale (Brown, Mounts, Lamborn, & Steinberg, 1993). Items included statements about parents’ knowledge of their child’s whereabouts, companions, and activities when unsupervised (I have a parent/guardian who: “Really knows where I am after school,” “Really knows where I go at night”). Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). One item was excluded from the analysis because data on this item was not collected at Time 2 of youth survey.

Participants’ perceptions of parent psychological control were assessed with the 8-item Psychological Control Scale Youth Self-Report (Barber, 1996). Items included statements about such parent behaviors as love withdrawal, guilt induction, and invalidation of child’s feelings (I have a parent/guardian who: “Brings up past mistakes when he/she criticizes me,” “If I have hurt feelings, stops talking to me until I please her/him again”). Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Analyses

Preliminary analyses

The 12 items of the adapted Parental Support for Fighting scale were submitted to Principal Components Analysis (PCA). The PCA yielded three eigenvalues greater than one (3.19, 2.05, 1.10) suggesting a maximum of three factors be extracted using the Kaiser criterion (Kaiser, 1960). However, a two-factor PCA was also examined given the findings of previous research (Multisite Violence Prevention Project, 2006). Varimax rotation was used because we did not expect the factors to be correlated. The three-factor solution revealed that all 12 items loaded at .40 or greater on one of the three factors with no cross-loading and explained 52% of variance; however, the two-factor solution yielded a more meaningful structure conceptually (Pett, Lackey, & Sullivan, 2003), and accounted for 44% variance. This solution combined 5 conceptually similar items (i.e., expectations for aggressive solutions) that loaded at .40 or greater on the first and third factors. In the two-factor solution, these 5 items loaded at .40 or greater on one factor that reflected an expectations for aggressive solutions dimension; the second factor was comprised of seven items loaded at .40 or greater and reflected parental expectations for peaceful solutions. Thus, two variables were used, which were labeled expectations for peaceful solutions (α = .73 at Time 1, .80 at Time 2) and expectations for aggressive solutions (α = .78 at Time 1, .84 at Time 2).

PCA with Varimax rotation was also performed to determine whether the support, knowledge, and psychological control items loaded on factors consistent with their respective scales. The relation between each factor and the dependent variables was the aim of our subsequent analyses, thus Varimax rotation was chosen to constrain the factors to be uncorrelated. Although the PCA yielded five eigenvalues greater than one (5.53, 2.77, 1.33, 1.29, 1.20), the shape of the scree plot suggested a four factor extraction. With the goal of reducing the number of factors extracted to enhance interpretability, four-, three-, and two-factor solutions were examined.

In the four-factor solution, the support and psychological control items generally loaded at .40 or greater on the first and second factors, respectively. Knowledge items loaded at .40 or greater on either the first, third, or fourth factor. The third and fourth factors were composed of items from each of the three scales and failed to exhibit a meaningful structure. This pattern of findings was similarly observed in the three-factor solution which explained 44% of the variance. Although the first and second factors were conceptually meaningful, the third factor demonstrated little conceptual cohesion. A two-factor solution explained 38% of the variance and provided the clearest solution; the first factor consisted of only support and knowledge items and the second factor consisted of psychological control items. Thirteen of the 22 items loaded at .40 or greater on a dimension of support or knowledge, and 7 items loaded .40 or greater on a dimension of psychological control. Thus, two variables were used, which were labeled support/knowledge (α = .85 at Time 1, .86 at Time 2) and psychological control (α = .71 at Time 1, .81 at Time 2). One knowledge and one psychological control item were dropped because factor loadings were less than .40 on both dimensions.

Items were summed and a tertile split was used to create high, moderate, and low categories for the parent support/knowledge, parental expectations for peaceful solutions, and parental expectations for aggressive solutions variables. A median split was used to create high and low categories for the parent psychological variable. Variables were coded such that higher values represented levels of parenting practices protective against engagement in early adolescent aggression.

Analytic strategy

Multiple imputation (MI), a multistage procedure designed to replace missing values with a set of plausible values, was employed. MI provides the advantage of yielding more precise parameter estimates (e.g., beta coefficients) when compared to datasets with missing values imputed one time (Schafer, 1999). Prior to performing MI, the data were evaluated to ensure that missing values were missing at random (MAR) rather than systematically missing (i.e., participants with missing data on a particular variable were not likely to have significantly lower [or higher] values on that variable compared to participants with data present [Allison, 2002]). Next, the level of missing data was inspected to ensure a rate of 15% or less missing data across scale or index scores, a rate not exceeded in studies on the treatment of missing scale score data (van Ginkel, van der Ark, & Sijtsma, 2007). The assumption of MAR was met and the rate of missing data across scales or indices (5–10%) was acceptable. Missing values were imputed using the PROC MI procedure in SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, 2003).

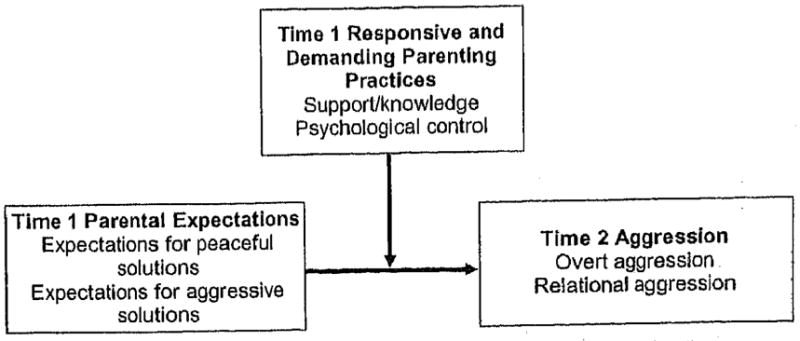

Unadjusted logistic regression odds ratios were used to examine the bivariate relations among the independent and dependent variables. Gender, age, and Time 1 aggression were controlled for in all multivariate models. Although preliminary analyses revealed that the larger youth violence study intervention was not associated with changes in aggression in both the intervention and control groups between Time 1 and Time 2, the overt and relational aggression indices used in the current study were not tested in those prior analyses. Thus, treatment status is controlled for in this study. We also controlled for participation (fall or spring semester) because bivariate analyses indicated that youth who reported Time 2 relational aggression were more likely to have been in the fall semester group. Multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the relations between each parenting variable at Time 1 (expectations for peaceful solutions, expectations for aggressive solutions, support/knowledge, and psychological control) and aggression at Time 2. Interaction effects models were tested to explore whether (a) Time 1 support/knowledge moderated the relation between Time 1 parental expectations and Time 2 aggression, and (b) Time 1 psychological control moderated the relation between Time 1 parental expectations and Time 2 aggression (Figure 1). The logistic regression interaction effects models also revealed whether parental expectations moderated the relation between Time 1 support/knowledge and Time 2 aggression and whether parental expectations moderated the relation between Time 1 psychological control and Time 2 aggression. The SAS 9.1 statistical software program was used to perform these analyses (SAS Institute, 2003).

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized relation between parental expectations and responsive and demanding parenting practices at Time 1 in the prediction of early adolescent aggression at Time 2.

RESULTS

Unadjusted Logistic Regression Results

As shown in Table 1, overt and relational aggression increased between Time 1 and Time 2, however, this increase was not statistically significant. Table 2 shows that the proportion of youth who reported engaging in overt aggression at Time 2 (78%) was higher than those who reported engaging in relational aggression at Time 2 (67%). Participants who reported moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions were almost 45% (odds ratio [OR] = 0.57, confidence interval [CI]: 0.35–0.93) less likely to report engaging in overt aggression at Time 2. Early adolescents reporting low levels of parental expectations for aggressive solutions had a similar decrease in the likelihood of engaging in Time 2 overt aggression (OR = 0.62, CI: 0.39–0.98). Participants reporting high levels of support/knowledge were nearly 40% less likely to engage in overt aggression at Time 2 (OR = 0.59, CI: 0.36–0.96).

TABLE 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Dependent and Independent Variables (N = 209)

| Variable | Time 1

|

Time 2

|

Mean difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | ||

| Overt aggression | 0–15 | 3.46 | 3.59 | 0–15 | 3.96 | 3.97 | .50 |

| Relational aggression | 0–10 | 2.12 | 2.65 | 0–10 | 2.37 | 2.66 | .25 |

| Parental expectations for peaceful solutions | 1–10 | 6.73 | 2.41 | 1–10 | 6.65 | 2.67 | −.08 |

| Parental expectations for aggressive solutions | 1–10 | 4.30 | 2.21 | 1–10 | 4.50 | 2.47 | .20 |

| Parent support/knowledge | 1–5 | 4.04 | .83 | 1–5 | 4.19 | .80 | .15 |

| Parent psychological control | 1–5 | 2.82 | 1.01 | 1–5 | 2.49 | 1.08 | .33*** |

p < .001.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Early Adolescent Reports of Aggression at Time 2 by Level of Parenting Practices at Time 1 (N = 209)

| Overt aggression T2

|

Relational aggression T2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR (95% CI) | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sample prevalence | 162 (78%) | 141 (67%) | ||

| Parental expectations for peaceful solutions | ||||

| High | 46 (22%) | 1.18 (0.69–2.02) | 38 (18%) | 0.98 (0.61–1.58) |

| Moderate | 53 (26%) | 0.57 (0.35–0.93)* | 46 (22%) | 0.67 (0.44–1.03) |

| Low | 63 (30%) | 1.00 | 57 (27%) | 1.00 |

| Parental expectations for aggressive solutions | ||||

| Low | 45 (22%) | 0.62 (0.39–0.98)* | 49 (23%) | 1.17 (0.74–1.84) |

| Moderate | 56 (27%) | 1.17 (0.69–1.98) | 45 (22%) | 0.87 (0.54–1.40) |

| High | 61 (29%) | 1.00 | 47 (22%) | 1.00 |

| Parent support/knowledge | ||||

| High | 47 (23%) | 0.59 (0.36–0.96)* | 41 (20%) | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) |

| Moderate | 55 (26%) | 0.87 (0.49–1.56) | 49 (23%) | 1.02 (0.65–1.60) |

| Low | 60 (29%) | 1.00 | 51 (24%) | 1.00 |

| Parent psychological control | ||||

| Low | 76 (37%) | 1.07 (0.76–1.50) | 63 (30%) | 0.88 (0.66–1.19) |

| High | 86 (41%) | 1.00 | 78 (37%) | 1.00 |

Note. The last category was the reference group.

p < .05.

Adjusted Logistic Regression Results

Adjusted analyses of the relations just reported are shown in Table 3. Controlling for gender, age, treatment status, participation (fall or spring semester) and Time 1 aggression, the relation between moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions at Time 1 and overt aggression at Time 2 remained significant (OR = 0.49, CI: 0.28–0.87). Parental expectations for peaceful solutions at Time 1 was unrelated to relational aggression at Time 2. Parental expectations for aggressive solutions, support/knowledge control, and psychological control, were also not significantly associated with either overt or relational aggression (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Adjusteda Odds Ratios for Early Adolescent Reports of Aggression at Time 2 in Relation to Time 1 Parental Expectations for Peaceful Solutions (N = 209)

| Overt aggression T2

|

|

|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1 | |

| Gender (male) | 0.89 (0.61–1.31) |

| Age (12 years or <) | 0.83 (0.55–1.24) |

| Treatment (intervention group) | 1.49 (1.00–2.22) |

| Participation (fall) | 1.16 (0.78–1.73) |

| T1 aggression | 2.19 (1.40–3.41)*** |

| Model 2 | |

| Gender (male) | 0.89 (0.61–1.31) |

| Age (12 years or <) | 0.83 (0.55–1.24) |

| Treatment (intervention group) | 1.49 (1.00–2.22) |

| Participation (fall) | 1.16 (0.78–1.73) |

| T1 aggression | 2.19 (1.40–3.41)*** |

| Parental expectations for peaceful solutions: High | 1.43 (0.79–2.56) |

| Parental expectations for peaceful solutions: Moderate | 0.49 (0.28–0.87)* |

| Parental expectations for peaceful solutions: Low | 1.00 |

Note. The last parental expectations for peaceful solutions category was the reference group. The reference groups for control variables are Gender: female; Age: > 12 years; Treatment status: control group; Participation: fall; Time 1 Aggression: not aggressive.

Adjusted for gender, age, treatment group, semester participated in study (fall or spring), and baseline aggression.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

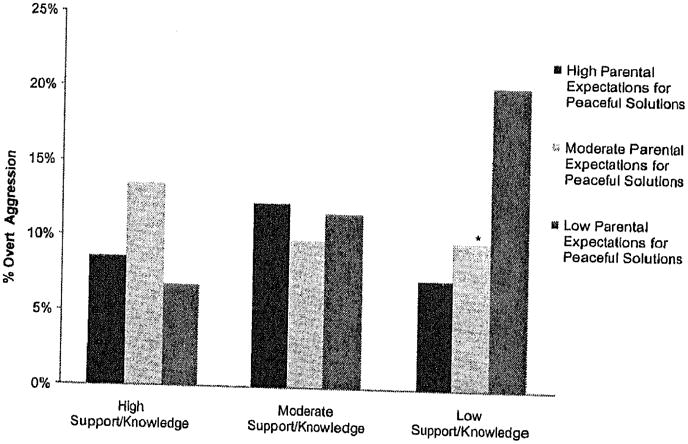

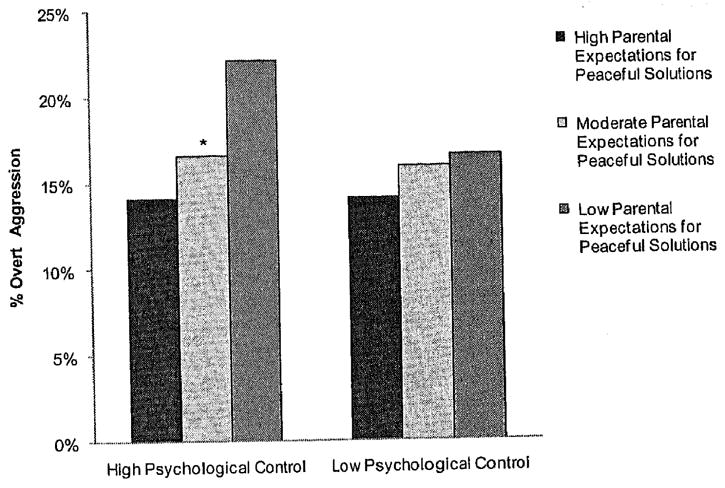

Interaction Effects

The analyses examining the moderation by support/knowledge of the relation between parental expectations and overt or relational aggression were not significant. Parent psychological control did not moderate the relation between parental expectations and overt or relational aggression. However, as shown in Figure 2, parental expectations for peaceful solutions at Time 1 moderated the relation between support/knowledge at Time 1 and overt aggression at Time 2. Participants reporting moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions and low parent support/knowledge were less likely to report engaging in overt aggression at Time 2 (OR = 0.46, CI: 0.24–0.88) compared to those reporting both low parental expectations for peaceful solutions and low support/knowledge. In addition, as shown in Figure 3, participants reporting moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions and high parent psychological control were less likely to report engaging in Time 2 overt aggression (OR = 0.48, CI: 0.27–0.87) compared to youth reporting both low parental expectations for peaceful solutions and high psychological control. Early adolescents reporting moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions and high parent psychological control were also less likely to report engaging in Time 2 relational aggression (OR = 0.58, CI: 0.34–0.99; relational aggression figure not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of overt aggression by parental expectations for peaceful solutions and support/knowledge interaction groups (N = 209; *p < .05).

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of overt aggression by parental expectations for peaceful solutions and psychological control interaction groups (N = 209; *p < .05).

DISCUSSION

Multivariate model findings indicate that study participants who reported having parents who they perceived as having expectations for peaceful solutions to aggression at a moderate level were less likely to report engaging in overt aggression three months later. This finding suggests that when youth perceive that their parents communicate expectations about avoiding aggression such as walking away, telling an adult, or peacefully solving problems with peers, young adolescents can adopt or sustain these strategies in a relatively short period of time. The association between parental expectations and early adolescent aggression in this study is consistent with that of previous studies (Malek et al., 1998; Orpinas et al., 1999). These previous studies have exclusively examined the role of parental endorsement of aggressive solutions. Thus, the present study represents one of the first studies to report on the effect of a protective parental expectation to aggression, expectations for peaceful solutions, on early adolescent aggression.

A direct relation between support/knowledge and aggression was only partially demonstrated in the current study. Parent support/knowledge was associated with aggression in the unadjusted, but not the adjusted overt aggression models. This finding runs counter to other studies that have revealed inverse associations between aggression and measures of both support and knowledge among similar samples (e.g., Laird et al., 2003; Prelow et al., 2007; Simons-Morton et al., 2004). The finding that psychological control was unrelated to aggression is not consistent with other adolescent studies that have found positive associations between psychological control and problem behaviors (e.g., Barber, 1996; Loukas et al., 2005). However, these studies have included samples that were predominately White, and middle class. Using a sample more similar to this study, Bean et al. (2006) found that psychological control and delinquency were unrelated in multivariate models. The nonfindings of this study and the Bean et al. study suggest a need to understand more comprehensively the role of psychological control in African American families. Perhaps certain aspects of psychological control like restrictiveness, as found in the Mason et al. (1996) study are most relevant to African American parenting among families living in high violence urban communities.

Neither support/knowledge nor psychological control moderated the relation between parental expectations and aggression. Therefore, the premise that indicators of a high quality parent-child relationship (support/knowledge and psychological control) alter the effectiveness of parental expectations was not empirically supported in this urban African American sample. Yet, another relation between these indicators of the parent-child relationship and parental expectations was found. Study participants who perceived both moderate parental expectations for peaceful solutions to aggression and relatively low levels of parental support and knowledge were less likely to report engaging in overt aggression. Similarly, participants who perceived both moderate parental expectations for peaceful solutions and high levels of psychological control were less likely to report engaging in overt and relational aggression. These findings suggest that parental expectations for peaceful solutions may play an important role in lowering risk for aggression in the context of parenting characterized by relatively low levels of parental responsiveness and awareness of adolescents’ whereabouts and high levels of psychological control. Given the high levels of violence in their school and community environments, this effect may have been observed over a three-month period because the fear of victimization and other consequences of aggression prompted these young middle students to heed parental messages.

Although moderate levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions emerged as a significant predictor in several models, high levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions was unrelated to aggression. This unexpected finding is similar to findings observed by Mason et al. (1996) in their examination of the influence of parental behavioral control (monitoring) at varying levels of peer problem behavior. When early adolescents reported having many problem-behaving peers, moderate levels of parent behavioral control were protective against early adolescent problem behavior (e.g., fighting, gang activity, drug use). In contrast, high levels of behavioral control and low levels of behavioral control were associated with increased early adolescent problem behavior. The Mason et al. findings suggest that providing moderate levels of behavioral control was sufficient for parents to reduce youth problem behavior, while providing high levels of behavioral control represented parents’ efforts to counteract their adolescent’s existing problem behavior, and low levels proved ineffective.

There is indication that a similar curvilinear relationship between parenting and behavior may have been demonstrated in the current study. A consistent, though nonsignificant, finding across study models was that study participants who reported high levels of parental expectations for peaceful solutions were more likely to have engaged in overt or relational aggression at Time 2 relative to early adolescents who reported low levels of this parenting strategy. Thus, like the Mason et al. (1996) study, findings in this study may represent parents’ reacting to their adolescents’ existing aggressive behavior by reiterating a protective parenting strategy (i.e., parental expectations for peaceful solutions to aggression).

PCA results revealed a factor that combined parental support and knowledge suggesting that the adolescent perceptions of parents’ knowledge items were closely correlated with the adolescent perceptions of parent support items. More specifically, parent support may facilitate greater parental knowledge about the child’s whereabouts and peer affiliations including who the child’s friends are, where the child spends his or her free time, and where the child is after school. This finding is consistent with other studies that have found high correlations between knowledge and measures of responsiveness such as support (Kerr et al., 2002; Kerr & Stattin, 2000).

Study Limitations

Findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The sample was relatively small and not all eligible students in the school participated. Although previous studies of similar populations have reported response rates comparable to that found in this study, the low response rate could have reflected important selection effects. Furthermore, the three-month follow-up in the current study is relatively brief. Previous middle school-based violence prevention programs typically follow-up six months to one year after intervention (Harrington, Giles, Hoyle, Feeney, & Yungbloth, 2001; Orpinas et al., 2000). However, we anticipated that participants’ transition to middle schools characterized by high levels of violence might prompt new patterns in parenting making change during this time period plausible. Another possible study limitation was the assessment of youth perceptions of parenting, without assessment of parent report measures.

Conclusion

Additional research is necessary that explores the effect of parental expectations, support, knowledge, and psychological control on early adolescent aggression in urban, African American early adolescent samples taken from a large sample of schools that vary in violent incidents. The finding that parental expectations altered the effectiveness of both support/knowledge and psychological control merits further research, particularly the distinction between practices that specifically encourage aggressive solutions and those that encourage peaceful responses. Research is also recommended that examines parental expectations and other parenting practices in combination with other economic, community, cultural, and peer norms regarding aggressive behavior among urban, African American early adolescents residing in low-income and under-resourced neighborhoods. For example, school practices and procedures regarding student aggression and adolescent perceptions of school climate might be considered. Longitudinal studies with multiple time intervals provide an opportunity to evaluate how youths’ preexisting levels of aggression, parenting, and other social influences including neighborhood and school characteristics, influence developmental and relationship patterns overtime.

The findings of this study have important implications for aggression and violence prevention interventions targeted to African American early adolescents and their parents living in environments with high levels of community violence. Study findings suggest that it may be warranted to evaluate the effects of interventions designed to increase and improve parent’s communication about their expectations for peaceful solutions. Providing opportunities for parents to clarify their values related to aggression and violence is one possible method that could assist parental communication of aggression avoidance messages. In addition, programs could seek to facilitate parents’ supportive bonds with their teens.

Contributor Information

KANTAHYANEE W. MURRAY, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

DENISE L. HAYNIE, Division of Epidemiology, Statistics, and Prevention Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Rockville, Maryland, USA

DONNA E. HOWARD, Department of Public and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Maryland College Park, College Park, Maryland, USA

TINA L. CHENG, Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

BRUCE SIMONS-MORTON, Division of Epidemiology, Statistics, and Prevention Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Barber B. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development. 1996;67:3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber B, Olsen JE, Shagle SC. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development. 1994;65:1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean RA, Barber BK, Crane DR. Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African-American youth. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1335–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Loeber R, Wikstrom PH, Stouthamer-Loeber M. What predicts adolescent violence in better-off neighborhoods? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:369–381. doi: 10.1023/a:1010491218273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Mounts N, Lamborn SD, Steinberg L. Parenting practices and peer affiliations in adolescence. Child Development. 1993;64:467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MA. Inequality and adolescent violence: An exploration of community, family, and individual factors. Journal of the National Medication Association. 2004;96:486–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decoster S, Heimer K, Wittrock SM. Neighborhood disadvantage, social capital, street context, and youth violence. The Sociological Quarterly. 2006;44:723–753. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D. The social ecology of community and neighborhood and risk for antisocial behavior. In: Essau CA, editor. Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Mahwah, NT: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington N, Giles SM, Hoyle RH, Feeney GJ, Yungbluth SC. Evaluation of the All Stars character education and problem behavior prevention program: Effects on mediator and outcome variables for middle school students. Health Education Behavior. 2001;28:533–546. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Foshee VA. Violence-related behaviors of adolescents: Relations with responsive and demanding parenting. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1998;13:343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser H. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Biesecker G, Ferrer-Wreder L. Relationships with parents and peers in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Easterbrooks MA, Mistry J, editors. Handbook of psychology: Developmental psychology. Vol. 6. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002. pp. 395–419. [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Peuit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Change in parents’ monitoring knowledge: Links with parenting, relationship quality, adolescent beliefs, and antisocial behavior. Social Development. 2003;12:401–419. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Hay D. Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:371–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Paulos SK, Robinson S. Early adolescent social and overt aggression: Examining the roles of social anxiety and maternal psychological control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Malek MK, Chang B, Davis TC. Fighting and weapon-carrying among seventh-grade students in Massachusetts and Louisiana. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23:94–102. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CA, Cauce AM, Gonzales N, Hiraga Y. Neither too sweet nor too sour: Problem peers, maternal control, and problem behavior in African American adolescents. Child Development. 1996;67:2115–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland State Department of Education. Maximizing implementation of No Child Left Behind. Component 16, School Safety and Health, 3–105. 2005 Retrieved February 28, 2010, from http://www.marylandpublicschools.org/NR/rdonlyres/0146EDA2-5F91-47DD-9A84-16164BDEA25C/6754/MaiylandDiagnosticReport.pdf.

- Multisite Violence Prevention Project. Description of measures: Cohort-wide student survey. 2006. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Berkel C, Brody GH, Gibbons M, & Gibbons FX. The strong African American families program: Longitudinal pathways to sexual risk reduction. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Frankowski R. The Aggression Scale: A self-report measure of aggressive behavior for young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Kelder S, Frankowski R, Murray N, Zhang Q, McAlister A. Outcome evaluation of a multi-component violence prevention program for middle school students: The Students for Peace project. Health Education Research. 2000;15:45–58. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Murray N, Kelder S. Parental influences on students’ aggressive behaviors and weapon carrying. Health Education and Behavior. 1999;26:774–787. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petras H, Schaeffer C, Ialongo N, Hubbard S, Muthen B, Lamert S. When the course of aggressive behavior in childhood does not predict antisocial outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood: An examination of potential explanatory variables. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;15:919–941. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pett MA, Lackey NR, Sullivan JJ. Making sense of factor analysis: The use of factor analysis for instrument development in health care research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD, Chase-Lansdale PL. African American adolescent girls in impoverished communities: Parenting style and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Research on Adolescents. 2001;11:199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Bowman MA, Weaver SR, Scott R. Predictors of psychosocial well-being in urban African American and European American youth: The role of ecological factors. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2007;36:543–553. [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Miller BV, O’Donnell PC, Wasserman MS, Colder C. Parental monitoring mediates the effects of age and sex on problem behaviors among African-American urban young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. Version 9.1 [Computer Program] Gary, NC: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: A primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;89(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Chen R. Latent growth curve analyses of parent influences on drinking progression among early adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Chen R, Hand L, Haynie D. Parenting behavior and adolescent conduct problems: Reciprocal and meditational effects. Journal of School Violence. 2008;7(1):3–15. doi: 10.1300/J202v07n01_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Hartos JL, Haynie DL. Prospective analysis of peer and parent influences on minor aggression among early adolescents. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31(1):22–33. doi: 10.1177/1090198103258850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, Mounts NS, Dornbusch SM. Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development. 1994;65:754–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Schreck CJ, Simons RL. ‘I Ain’t Gonna Let No One Disrespect Me’: Does the code of the street reduce or increases violent victimization among African American adolescents? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2006;43:427–458. [Google Scholar]

- van Ginkel JR, van der Ark LA, Sijtsma K. Multiple imputation of item scores in test and questionnaire data, and influence on psychometric results. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:387–414. doi: 10.1080/00273170701360803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DR, Fitzpatrick KM. Violence and minority youth: The effects of risk and asset factors on fighting among African-American children and adolescents. Adolescence. 2006;41(162):251–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]