Abstract

Positive parenting practices have been shown to be essential for healthy child development, and yet have also been found to be particularly challenging for parents to enact and maintain. This paper explores an innovative approach for increasing positive parenting by targeting specific positive emotional processes within marital relationships. Couple emotional acceptance is a powerful mechanism that has repeatedly been found to improve romantic relationships, but whether these effects extend to the larger family environment is less well understood. The current longitudinal study examined the role of improved levels of acceptance in mother’s and father’s positive parenting after a couple intervention. Participants included 244 parents (122 couples) in the Marriage Checkup (MC) study, a randomized, controlled, acceptance-based, intervention study. Data indicated that both women and men experienced significantly greater felt acceptance two-weeks after the MC intervention, treatment women demonstrated greater positive parenting two weeks after the intervention, and all treatment participants’ positive parenting was better maintained than control couple’s six months later. Importantly, although mothers’ positive parenting was not influenced by different levels of felt acceptance, changes in father’s positive parenting were positively associated with changes in felt acceptance. As men felt more accepted by their wives, their levels of positive parenting changed in kind, and this effect on positive parenting was found to be mediated by felt acceptance two weeks after the MC. Overall, findings supported the potential benefits of targeting couple acceptance to generate positive cascades throughout the larger family system.

Keywords: positive parenting, couples, acceptance, multilevel modeling, fathering

Research literature and popular press agree that positive parenting behaviors are among the most important skills for healthy child development across cultures (e.g. Castro et al., 2013; Dwairy, 2009; Harwood & Eyberg, 2006; Jones, Forehand, Rakow, Colletti, & McKee, 2008; McKee et al., 2007; Skinner, Johnson & Snyder, 2005; Webster-Stratton, 1982). Positive parenting practices, defined as warmth, acceptance, positive reinforcement, support, affection, and involvement, have been shown to be essential for a child’s self-esteem, cooperation, emotion regulation, and other prosocial skills that contribute to success in school, social interactions, and the workforce (e.g. Barkley, 1997). Although parental discipline and supervision also play important roles in child development, a 2008 meta-analysis of 77 parenting training programs found the most effective component for both parent-child relations and child wellbeing were positive interactions between the parent and child (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2008). Positive parenting is believed to foster a cooperative, reciprocal, compromising tone which enhances mutual enjoyment of parent-child interactions (Kochanska, Aksan, Prisco, & Adams, 2008). Data also suggest that parents who positively reinforce their children’s prosocial behaviors and who express warmth are less likely to fall into a coercive parent-child cycle, which has been linked to many deleterious effects such as Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder (Patterson, 1982). It has also been found to be more effective to implement effective discipline after first having a positive and involved parent-child relationship (McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010).

Despite their critical importance, positive parenting practices are particularly challenging for parents to enact, garner more parental resistance to training, and fade more quickly from parent training repertoires (Barkley, 1997; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010; Patterson, 1982; Webster-Stratton, 1982). At follow-up after parent training, parents were less likely to have maintained the positive parenting skills than the discipline techniques (Barkley, 1997). Human brains seem to be biologically predisposed to be attuned to negative thoughts and behaviors, while tending to overlook the positive aspects (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001; Kazdin, 2008). This bias is further exacerbated given that children and parents are naturally irritating and stressful to each other, and even the best behaved of children only comply about 60–80% of the time (Barkley, 1997; Kazdin, 2008). Indeed, 90% of American caregivers resort to using some kind of psychological aggression against their children, behaviors that have been associated with higher rates of delinquency and psychosocial problems (Straus and Field, 2003). Thus, bridging this divide between the promise of positive parenting and the difficulty implementing and sustaining these essential behaviors is a crucial challenge facing family researchers.

One unique approach for increasing positive parenting is through couple interventions. In 2012, 64% of children ages 0–17 in the U.S. lived with two married parents (U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey), enabling both parents to have a significant impact on child development. Indeed, past research has shown that targeting both parents can have a far-reaching impact on parent-child interactions and therefore child outcomes (e.g. McKee et al., 2007; Owen & Cox, 1997). Furthermore, systems theory and empirical research studies alike consistently support associations between marital relationships and parenting processes, most often through an negative emotional spillover process where tension in the marital dyad is transferred to the parent-child dyad (e.g. Belsky, 1984; Cummings & Davies, 2010; Erel & Burman, 1995; Katz & Gottman, 1996; Kouros, Papp, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2014; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; Minuchin, 1985). On the flip side, Masten and Cicchetti (2010) discussed how positive interactions in one part of a system can engender positive cascades across generations. Goldberg & Easterbrooks (1984) agreed that just as an emotionally draining marriage will deprive parents of resources necessary for warm parenting, marriages that meet parents’ emotional needs will foster stronger relationships with their children. The current paper adds to the literature by exploring the role of positive couple processes to strengthen mothers’ and fathers’ ability to parent in a warm, involved manner (e.g. Bonds & Gondoli, 2007).

Acceptance is a particularly potent emotional process that has consistently been found to increase intimacy in couple relationships (e.g. Christensen, Atkins, Baucom, & Yi, 2010). Acceptance in couples is defined as the ability of romantic partners to welcome, appreciate, and cherish all aspects of each other, “warts and all” (Córdova, 2001). Fruzzetti and Iverson (2004) explained that partners receiving acceptance felt close to, understood, and supported by their partner, which was typically reciprocated in kind, resulting in greater intimacy and healthy relationship functioning. Furthermore, validation and support from one’s spouse bolsters emotion regulation abilities, enabling more effective psychological processing of complex stimuli within the environment. Therefore, partners’ increased emotion regulation from felt acceptance would theoretically facilitate conscious and measured parenting, rather than reflexive reactions to terminate aversive child behaviors (Fruzzetti & Iverson, 2004). Similarly, social support, especially from someone facing the same stressor (e.g. the child), has been found to be especially beneficial for positive coping to help individuals withstand challenges and frustrations (e.g., Schwarzer & Knoll, 2007). Thus, interventions targeting relational acceptance could enable adaptive familial cascades by increasing positive romantic processes that protect against negative outcomes from inherently challenging parent-child interactions (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). This “theory of intervention” would expect that initiating changes in couple acceptance would in turn impact parenting behaviors due to cascading effects from the intervention to the mediator to the outcome (Kim & Kochanska, 2014; Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). That is, acceptance-based couple interventions would influence positive parenting behaviors through the mediator of relational acceptance.

The recent Marriage Checkup study (MC; Córdova et al., 2014) afforded a unique opportunity to examine the influence of couple acceptance on positive parenting. One of the active therapeutic ingredients in the two-session MC intervention was promoting couples acceptance of each other, drawing from Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (IBCT; Jacobson & Christensen, 1996); IBCT was developed to increase emotional acceptance of partners’ immutable differences. Although the MC did not explicitly focus on parenting unless couples raised the issue, 57% of the couples in the study were parents raising children.

Few marital therapy studies have investigated the couple’s parenting behaviors, and the small number that have found divergent outcomes. Gattis, Simpson, and Christensen (2008) reported that couples with children whose overall marital satisfaction improved after treatment with either Traditional Behavioral Couple Therapy (TBCT) or IBCT also experienced less conflict over child rearing, an effect that was maintained for at least two years. Conversely, a 2007 study of the Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET) found that child-related parental conflicts did not decrease markedly after participation in the CCET, despite improvements in overall communication and coping (Ledermann, Bodenmann, & Cina, 2007). The current study aims to add to this debate about whether marital therapy interventions influence parenting behaviors, as well as to extend the literature into the specific role of relational acceptance in mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting practices.

To examine the associations between relational acceptance and positive parenting in the context of the intervention, we examined the following three hypotheses: 1) Mothers and fathers who received the MC treatment would report increased levels of felt acceptance. However, we expected that this treatment effect would wane across time as has been found in previous outcome studies of couple interventions (Christensen et al., 2010; Córdova et al., 2014); 2) Mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting would increase after the MC intervention. However, we anticipated that this effect would be progressively greater, indicating a more distal effect of the MC on parenting (Schwarzer & Knoll, 2007); and 3) When including relational acceptance as a predictor of positive parenting, levels of felt acceptance would be positively associated with levels of mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting across the year, and the effect of the Marriage Checkup on positive parenting would be mediated by felt acceptance.

METHOD

Participants

Of the 215 randomized treatment and control couples recruited between 2007–2010 from a metropolitan area in the northeastern United States, 122 (56.7%) were opposite-sex parents raising children under 18-years-old in their homes (64 treatment couples, 58 control couples). One hundred and one of these parent couples remained in the study at the end of one year (50 treatment couples, 51 control couples), averaging a 17.9% drop-out rate across the year. The reasons for drop outs ranged from simply declining further participation, to situational circumstances such as illness, injury, moving away, or the death of a spouse, to separation or divorce of the couple. The mean age for the mothers was 40.67 (7.22) and for fathers was 43.08 (8.19). Parent participants had been married for an average of 11.46 (7.57) years and the median household income was between $75,000–99,000 per year. As far as racial identification, 95.9% of wives and 91.8% of husbands described themselves as Caucasian, whereas 4.1% of wives and 7.4% of husbands identified as either African American, Asian, Latino/Latina, or Native American or Alaskan Native. On average these couples had 2.38 (1.35) children, and the mean age of the children was 10.24 (6.11) years old.

Measures

Positive Parenting

The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Frick, 1991) is a widely used, 42-item self-report measure of parenting practices that measures parental involvement, positive reinforcement, poor monitoring/supervision, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment. The validity and reliability of the APQ has been established in both clinic and community samples (e.g. Shelton, Frick, & Wootton, 1996), and has been shown to have moderate to high internal consistency (e.g. Dadds, Maujean, & Fraser, 2003). This study combined the two positive parenting scales of APQ – parental involvement (10 items) and positive reinforcement (6 items) – which are highly correlated across informant and assessment versions (r= .41-.85; M=.67) (McKee, Jones, Forehand & Cuellar, in press) and together have strong psychometric properties (August, Lee, Bloomquist, Realmuto, & Hektner, 2003; Hawes & Dadds, 2006). The 16-item positive parenting factor included items such as: “You have a friendly talk with your child” and, “You play games or do other fun things with your child.” Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher mean scores indicating more positive parenting practices.

The APQ was extended in the current study so that each partner rated his or her own as well as his or her partner’s parenting, allowing the mean of self- and partner-reported positive parenting to be used, increasing objectivity and decreasing the likelihood of social desirability and shared-method variance (Marsiglio, Amato, Day, & Lamb, 2000). The correlations between self- and partner-reports for the four time points ranged from .42 to .49, all significant and moderate correlations. Parents who had more than one child were asked to refer to the child they were most concerned about. No pattern of differences was found between the 105 couples who referred to the same child and 17 couples who referred to different children. The internal reliability consistency alphas for both self and partner-reported positive-involved APQ were between .86-.91 for the four time points.

Relational Acceptance

The Relational Acceptance Questionnaire (RAQ; Wachs & Córdova, 2007) is a 26-item scale that was designed to measure the degree to which partners were able to welcome each other as they are. Whereas instruments such as the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (Bond et al., 2011) measures an individual’s acceptance/flexibility versus experiential avoidance, and the Frequency and Acceptability of Partner Behavior Inventory (FAPBI; Christensen & Jacobson, 1997) measures acceptance of specific partner behaviors and relationship problems, the RAQ was developed as a global relational acceptance assessment tool for couples. The RAQ used a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating higher acceptance.

The RAQ measured two dimensions, 1) the respondent’s felt acceptance from his or her partner and 2) the respondent’s reported acceptance of his or her partner. Since the goal of this study was to measure how feeling accepted impacted one’s positive parenting, the former was used, the 13-item Relational Acceptance Questionnaire – Partner (RAQ-P) subscale. Items included statements such as, “My partner is completely accepting of who I am” and, “I am comfortable just being myself around my partner.” Internal reliability consistency alphas in this study for both women and men were between .93-.95 for each of the four time points, similar to the alpha of .94 found in a recent study of the entire sample of MC couples (Córdova et al., 2014).

Procedure

The MC study was a controlled, randomized, longitudinal marital intervention with nine assessment time points over two years. The MC offered annual checkups to couples at all levels of marital health, the relationship health equivalent of a physical health checkup. After completing informed consents and initial packets of questionnaires by mail, couples were randomly enrolled into either the treatment or control group. Treatment couples were immediately invited to attend an in-person assessment session, which culminated in a therapeutic interview based on IBCT. A motivational Feedback session was conducted two weeks later, followed by questionnaires sent two weeks, 6-months, and 1-year later. This cycle was then repeated for a second year. The overall goal of the MC was to enhance the positive emotional tone in the couple’s relationship, with the goal of turning the couples “shoulder to shoulder” and motivating them to move forward together. Control couples completed questionnaires at the same time points as the treatment couples, but were offered the in-person MC intervention at the end of the study.

The parenting data for this study were collected at: 1) pretreatment baseline, 2) two-week post intervention, or equivalent for control couples (~ 6-weeks after the baseline measures), 3) six-month post-intervention, or equivalent (~28 weeks after baseline), and 4) one-year post intervention, or equivalent (~56 weeks). The current study included the first year of the MC study since these time points contained an adequate sample size of parents to conduct fully powered multilevel modeling analyses. Prior research has supported the MC’s safety, acceptability, feasibility, attractiveness (Morrill et al., 2011) and efficacy (Córdova et al., 2005). Further descriptions of the treatments, therapist adherence, and study procedures have been detailed elsewhere (e.g. Sollenberger et al., 2013). The study was completed in compliance with the last author’s University Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Multilevel modeling with maximum likelihood estimation was used to analyze couple members’ evolving responses to treatment (Kenny & Kashy, 2011). Models were estimated using the mixed module of SPSS version 19. All models were two-level no-intercept models for distinguishable dyads using the dyad as the grouping variable and treating couple members as repeated measures which generated separate intercepts and slopes for men and women (Kenny & Kashy, 2011),

Given that we expected the period directly surrounding the intervention to differ from the subsequent follow-up period, we coded treatment as a time-varying pattern variable to accommodate this nonlinearity (Singer & Willett, 2003). Treatment couples were coded as 0 at baseline (before exposure to the intervention) and 1 at subsequent time points (after exposure to the intervention). Time was centered at the two-week post-treatment time point. Therefore, the treatment effect was modeled as two components: 1) the immediate pre-post effect, which is captured by the main effect of treatment on the intercept, and 2) the treatment group’s trajectory between two weeks post-treatment and one-year, as captured by the interaction effect of treatment with time. Thus, the linear slope is the slope for control couples, and the treatment X time interactions characterize the treatment group’s differential from this slope between two weeks post-treatment and one year.

In the final model, we disaggregated the between-person and within-person effects of relational acceptance on positive parenting, following Wang and Maxwell’s (2015) recommendations. The combined equation for women is presented below (see Appendix A for Level 1 and Level 2 models):

where F is a repeated measures that indexes the female within each couple1, for time t and dyad i. This paradigm allowed us to disentangle three effects: (1) whether individuals with higher levels of acceptance also had higher levels of positive parenting (β5); (2) whether individuals who started out higher in acceptance changed more in positive parenting over time (β6); and (3) whether individuals’ changes in acceptance were associated with their own changes in positive parenting (β4). We entered individuals’ baseline acceptance scores as a level–2, between-person effect to facilitate interpretation as the impact of initial status on their intercepts and trajectories, and calculated the level-1, within-person effect as individuals’ time-specific deviations from their baseline score. Baseline acceptance scores were grand-mean centered to yield a meaningful interpretation of the intercept.

To examine whether treatment influenced positive parenting indirectly through its influence on acceptance, we used Tofighi and MacKinnon’s (2011) RMediation package. This package uses a Monte Carlo method to generate asymmetric, 95-percent confidence intervals based on the distribution of the product of mediation pathways.

RESULTS

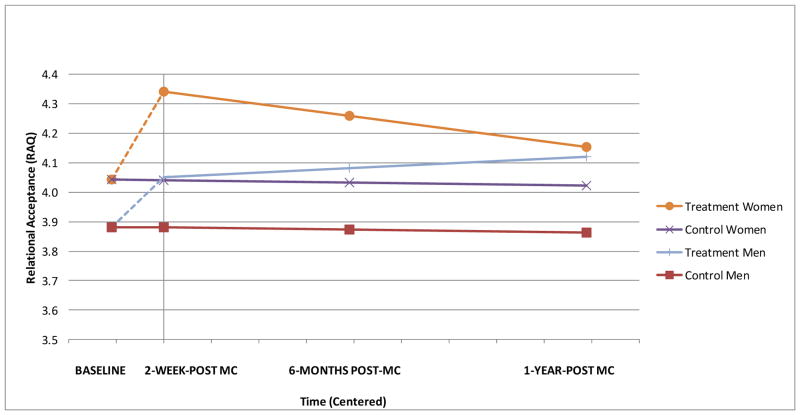

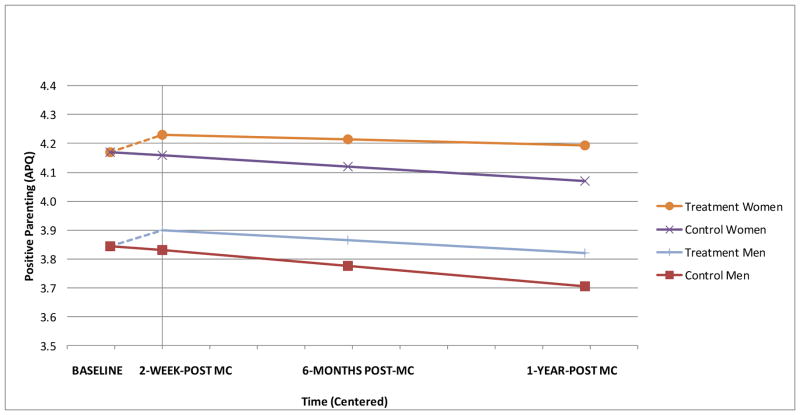

Table 1 presents the raw means and standard deviations of relational acceptance and positive parenting for treatment and control men and women, which are smoothed as multilevel model parameter estimates and used to create interpretable average linear trajectories in Figures 1 and 2. To validate the random assignment, t-tests were conducted on the raw baseline levels of relational acceptance for treatment versus control women (t(120.99) = −0.29, p=.77) and treatment versus control men (t(120) = 0.60, p=.55), and on the baseline levels of positive parenting for treatment versus control women (t(101) = 0.64, p=.53) and treatment versus control men (t(102) = 1.31, p=.19). No statistically significant pre-treatment group differences were found.

Table 1.

Means (Standard Deviations, and Sample Size in Parentheses) for Couple Acceptance and Positive Parenting for Treatment and Control Men and Women per Time Point

| Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | Baseline | 2-weeks | 6-months | 1-year |

| Group | ||||

| Gender | ||||

|

| ||||

| Relational Acceptance | ||||

| Treatment | ||||

| Women | 4.06 (0.92, 64) | 4.36 (0.75, 54) | 4.31 (0.76, 57) | 4.25 (0.72, 50) |

| Men | 3.84 (0.94, 64) | 4.02 (0.84, 53) | 3.98 (0.76, 52) | 4.17 (0.74, 49) |

| Control | ||||

| Women | 4.02 (0.82, 58) | 4.09 (0.88, 49) | 4.11 (0.79, 50) | 4.11 (0.84, 48) |

| Men | 3.93 (0.81, 58) | 3.88 (0.88, 49) | 4.05 (0.85, 50) | 3.99 (0.82, 46) |

|

| ||||

| Positive Parenting | ||||

| Treatment | ||||

| Women | 4.13 (0.48, 53) | 4.22 (0.43, 49) | 4.14 (0.44, 52) | 4.22 (0.50, 49) |

| Men | 3.77 (0.51, 53) | 3.84 (0.49, 50) | 3.81 (0.52, 52) | 3.83 (0.56, 50) |

| Control | ||||

| Women | 4.18 (0.37, 50) | 4.18 (0.42, 45) | 4.12 (0.39, 43) | 4.10 (0.50, 43) |

| Men | 3.89 (0.47, 51) | 3.86 (0.53, 45) | 3.79 (0.57, 44) | 3.80 (0.59, 43) |

Note. Positive Parenting= Alabama Parenting Questionnaire, Positive Parenting Subscale; mean of self and partner-reported scores; Relational Acceptance= Relational Acceptance Questionnaire; how accepted I felt by my partner

Figure 1.

Relational Acceptance of Women and Men by Treatment Condition

Figure 2.

Positive Parenting of Women and Men by Treatment Condition

Hypothesis 1: Intervention Effects on Acceptance

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, although women in general reported higher felt acceptance than men, both treatment women and men reported significant increases in felt acceptance at the two-week post-intervention time point compared to the control group. Over the follow-up, treatment women’s felt acceptance decayed significantly, meaning that the treatment effect decreased over time. Treatment men’s felt acceptance did not significantly change after the two-week point, indicating that men sustained their initial treatment gains. We conducted contrast tests on the model-generated point estimates at each time point and found that for women, the between-group contrasts were statistically significant through six months but no longer significant at the one-year point. For men, between group contrasts were significant throughout the entire follow-up period.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates and Effect Sizes for Treatment and Control Women and Men from Acceptance and Positive Parenting Multilevel Models (MLM) of Intervention Effects

| b (SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mother’s Acceptance | Father’s Acceptance | ||

| Intercept | |||

| Control | 4.04 (.08) | 3.88 (.08) | M̂diff = 0.16(0.07)* |

| Treatment effect | 0.30 (.07)*** | 0.17 (.07)* | |

| Effect size | 0.36 | 0.20 | |

| Rate of Change/Slope | |||

| Control | -.02 (.06) | -.02 (.07) | |

| Treatment effect | -.19 (.09)* | .10 (.11) | |

|

| |||

| Between-Group Differences | |||

| 6 months | 0.22 (.07)** | 0.20 (.07)** | |

| Effect size | 0.27 | 0.25 | |

| 1 year | 0.12 (.09) | 0.26 (.10)** | |

| Effect size | 0.15 | 0.31 | |

|

| |||

| Mother’s Parenting | Father’s Parenting | ||

| Intercept | |||

| Control | 4.16 (.04) | 3.83 (.05) | M̂diff =0.33(0.03)*** |

| Treatment effect | 0.07 (.04)* | 0.07 (.04)+ | |

| Effect size | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| Rate of Change/Slope | |||

| Control | -.10 (.05)* | -.14 (.05)* | |

| Treatment effect | .06 (.07) | .05 (.08) | |

|

| |||

| Between-Group Differences | |||

| 6 months | 0.10 (.04)* | 0.09 (.05)+ | |

| Effect size | 0.19 | 0.17 | |

| 1 year | 0.13 (.07)* | 0.12 (.08) | |

| Effect size | 0.25 | 0.23 | |

Note. N=244. Gender, time, and treatment condition were estimated simultaneously as predictors of positive parenting in one multivariate MLM. Intercepts were centered at two-weeks post-treatment. Predictors were centered or effects coded. Effect sizes were interpreted from Cohen’s d as small (0.2), medium (0.5) and large (0.8). M̂diff =the main effect for gender between mothers and fathers.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Hypothesis 2: Intervention Effects on Positive Parenting

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, women generally had higher positive parenting scores than men. The treatment effect on women’s positive parenting at two-week post intervention was significant and the treatment effect for men at the same time point trended towards statistical significance. The follow-up slopes indicated that all groups’ positive parenting significantly declined over the year. Between group contrasts indicated that treatment women had significantly higher levels of positive parenting than control women throughout the follow up period including at the one year assessment point, and although men’s treatment effect size was larger at six-months and one-year-post intervention than at two-weeks post, the between-group contrast was no longer significant one year later for men, perhaps attributable to decreased power.

Hypothesis 3: Effects of Acceptance on Positive Parenting

Results of Hypothesis 3 are presented in Table 3. For men, higher levels of acceptance were significantly associated with higher levels of positive parenting, and their individual changes in acceptance were associated with their own changes in positive parenting. Initial status of acceptance was not related to trajectories of positive parenting. For women, none of the effects of acceptance on positive parenting were significant. Sensitivity analyses found that results were robust to different centering strategies for the between-person effect (e.g., person-mean centering or centering around the two-week time point).

Table 3.

Between and Within-Person Effects of Acceptance on Positive Parenting

| Parameter | Women b (SE) |

Men b (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | ||

| Control | 4.15 (0.04) | 3.83 (0.04) |

| Treatment effect | 0.08 (0.04)* | 0.05 (0.04) |

| Rate of Change/Slope | ||

| Control | −0.10 (0.05) | −0.12 (0.05) |

| Treatment differential | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.03 (0.08) |

| Effects of Acceptance | ||

| Between-person | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.10 (0.04)* |

| Between-person X Time | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.03 (0.04) |

| Within-person | −0.03 (0.03) | 0.11 (0.03)*** |

| Indirect Effects | ||

| Tx → Acceptance2weeks → positive parenting2weeks | −0.008 [−0.026, 0.007] | 0.017 [0.002, 0.039] |

| Tx → Acceptance slope → positive parenting slope | 0.006 [−0.006, 0.023] | 0.006 [−0.022, 0.035] |

Note. . N=244. 95% confidence intervals are in brackets. Grand-mean centered baseline scores were used for between-person measure of acceptance. Within-person measures were time-specific deviations from baseline.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We also examined whether treatment modified the relationships between acceptance and positive parenting by including interactions with the treatment variable for each of the effects described above, and by comparing the more complex model to the simpler model with a deviance test on the −2 restricted log likelihood. The model without interactions had a better blend of fit and parsimony, χ2(6) = 7.98, p = .76, indicating that the relationship between acceptance and positive parenting did not differ across intervention arms. Lastly, we used Tofighi and MacKinnon’s (2011) RMediation package to test whether treatment indirectly influenced positive parenting through changes (i.e., within-person effects) in acceptance both in the initial period surrounding treatment, as well as between follow-up and one year. Indirect effects are presented in Table 3. For women, neither of these indirect effects were significant. For men, the indirect effect 2-weeks after the intervention was significant, as the 95-percent confidence interval in the initial period excluded zero, and the mediation effect accounted for 25% of the total treatment effect on positive parenting. The indirect effect over the follow-up period was not significant.

Sensitivity and Attrition Analyses

We compared couples based on dropout status before the one-year point. Dropouts did not differ on age, relationship length, income, number of children, or positive parenting, although there was a trend for both female and male dropouts to have lower levels of acceptance at baseline. In addition, women completers had more years of schooling (Mdiff = 1.89, p = .002). We used pattern mixture models (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997) to determine whether dropout status biased the estimate of the treatment effect. Although this model found a baseline difference between dropouts and completers, none of the Dropout x Treatment interactions were significant, indicating that attrition did not bias the estimates of the treatment effects.

Similarly, no model parameters differed significantly when the seventeen couples who reported parenting data on different children were removed from the analysis, indicating that the study findings were not sensitive to this difference.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this paper was to examine whether changes in acceptance were associated with changes in positive parenting, and whether the MC couple intervention increased warm, affectionate, involved parenting practices through its influence on acceptance. As predicted, both women and men reported significant increases in felt acceptance soon after receiving a Marriage Checkup, an acceptance-based intervention. Although in both conditions women felt more accepted by their husbands than men did by their wives, treatment women’s post-intervention jump in acceptance deteriorated over the following year. This post-treatment decline is commonly found after couple interventions, resulting in frequent recommendations for booster sessions (Christensen et al., 2010; Córdova et al., 2014). However, contrary to the existing literature, in this study men’s felt acceptance, though lower than women’s at baseline, not only improved but was maintained over time, suggesting a sustaining process may have been set in motion. It could be that a virtuous family cycle was set up in which as men felt more accepted they engaged in more positive parenting, which in turn perpetuated feeling more accepted by their wives which led to more effective parenting, etc.

Although it was not anticipated that all groups’ positive parenting would decline more or less steeply over the year, this finding was consistent with previous literature that in the absence of intervention the natural order of positive parenting may be steady decline (e.g. Kazdin, 2008; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2010). Doherty (1997) described the natural course of family relationships as “entropic,” naturally losing cohesion without intentional action to maintain positive relationships. These trajectories may also have been influenced by measurement factors, as parents were asked to refer to the child they were most concerned about. It is also possible that participants reported with less social desirability as they became more comfortable in the study. Even if somewhat more pronounced by these factors, the ubiquitous decline in positive parenting reiterated the need for family interventions that emphasize positive parenting skills to replace harsh and coercive parenting behaviors. One potential implication of these results is that, much like relationship satisfaction itself, if a steady decay in healthy parenting proves to be normative upon replication, then positive parenting may also benefit from a public health approach involving regular checkups specifically designed to reestablish positive parenting practices across developmental points (Flamm, Grolnick, & Diggins, 2015).

Despite the overall declines in positive parenting, treatment women’s positive parenting was greater than control women two weeks after the couple intervention, and men’s positive parenting trended toward being greater two-weeks after the intervention. This disparity grew 6-months later as the intervention appeared to protect men and women from the steeper declines seen in the control couples. These positive parenting findings were notable since the MC did not explicitly address parenting. Although the slope was nonsignificant, the growing effect sizes in the predicted direction partially supported the expected distal effect where improvements in relationship functioning provide emotional resources in the couple relationship that are later available to benefit the parent-child relationships (Schwarzer & Knoll, 2007). This potential transfer of emotional resources over time could explain why some past studies of couple therapy may not have detected changes in parenting domains in the absence of longitudinal follow-up in comparison to a control group.

A particularly intriguing finding emerged out of the differential effect of acceptance on mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting. Men who felt more accepted in this study also demonstrated more positive parenting, and as their individual levels of felt acceptance increased or decreased, their positive parenting changed in kind. Neither of these phenomena were found for women. Furthermore, the mediation model indicated that about a quarter of the intervention’s effect on men’s positive parenting two weeks after the MC was transmitted through its effect on acceptance, although no mediation was found for women.

These patterns support past research indicating that fathers’ parenting may be more strongly influenced by their couple relationships than mothers’ (e.g. Belsky et al., 1984; Coiro & Emery, 1998; Kitzmann, 2000; Kouros et al., 2014). Previous studies have suggested that fathers more closely associate their marital relationships with their parent-child relationships, while mothers experience these as distinct roles (Belsky et al., 1984). Indeed, results here suggest that wives were engaged with the kids regardless of how accepted they felt by their husbands, whereas for husbands these two processes were more interrelated. This could also reflect societal norms situating mothers as the primary parent, while relegating fathers to secondary role that therefore allows for a greater ease of withdrawing from parenting in the face of marital stress (e.g. Simons & Johnson, 1996).

It may also be that wives who were more accepting of their husbands engaged in less gatekeeping (Stevenson et al., 2014), facilitating more active paternal involvement followed by greater contingency-shaped fathering skills. Indeed, past research has found that fathers were able to fulfill their desired level of involvement with their child only when mothers were less critical (Schoppe-Sullivan, Brown, Cannon, Mangelsdorf, & Sokolowski, 2008). For men, whose parenting is oftentimes seen as secondary to women’s beginning at the earliest perinatal time, feeling more accepted by their spouses could lower the emotional and behavioral barriers to optimal parenting while building the confidence and self-efficacy necessary for deeply connecting with their children. Future interventions aimed at increasing overall positive parenting should therefore look beyond bolstering positive parenting skills towards targeting the quality of the relationship between the parents, particularly increasing fathers’ feelings of acceptance.

To the degree that our findings suggested that adaptive behaviors spread over time to enhance and protect multi-level family functioning, the clinical implications and future research opportunities for prevention and treatment are substantial (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). As has been recommended before, our findings would encourage couple practitioners and parenting educators to emphasize that the quality of the partners’ intimate relationship directly influences the quality of their parenting and thus ultimately the wellbeing of their child (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2008). Our finding that men generally enacted less positive parenting also supported the need for special efforts to reach and effectively intervene with fathers (e.g. Dwairy, 2010; Marsiglio et al., 2000). On the other hand, women may be particularly receptive to acceptance-based relationship interventions given that this type of emotional climate may not only improve their romantic relationships, but could also facilitate their spouse’s positive fathering. Future outcome research of such interventions with longer-term follow-up could elucidate the cascading mechanisms involved between father’s felt relational acceptance and their ability to be more involved with their children. Furthermore, given the argument that these cascading effects are likely to continue into the children’s functioning in the next generation of their own families, this suggests even longer-term implications of family-wide acceptance-based interventions (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Developmental cascades are believed to have enduring rather than transient effects on the course of development, and thus underscores the importance of vigorously promoting family-level relational processes clinically (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010).

Findings here could be built upon in future studies. For example, upcoming studies could compare couple interventions directly targeting positive parenting, such as through a Parenting Checkup format, to examine whether relational changes as well as parent training can multiplicatively influence positive parenting. Future studies might also disentangle the influence of partner effects (Cook, 1998), or employ latent variable modeling to include multiple raters and subscales of the parenting and acceptance constructs, perhaps with increased power to examine both years of the study. It would also be illuminating to more closely examine mothers’ and fathers’ agreement about their parenting, and whether this is associated with marital and child outcome variables.

Positive parenting is, of course, likely multiply determined, as the effects of the MC and relational acceptance on positive parenting were fairly small. Although a strength of this study was having both self and partner-report of positive parenting, child reports and observational data would allow an even more contextualized perspective of positive marital influences on positive parent-child interactions. Additionally, it would be compelling for future studies to explore how the mindfulness aspect of acceptance may enhance healthy couple and parenting relationships, given the growing body of literature espousing the benefits of mindfulness in many domains of psychological well-being, including parenting (Coyne & Murrell, 2009; Duncan, Coatsworth, & Greenberg, 2009).

The findings here were unfortunately limited by the all too common lack of diversity, hindering generalizations that should be drawn until they are replicated in a more racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse sample. Fortunately, preliminary demographics from a separate, large MC study currently in progress in Tennessee indicated that 48% of the sample reported low socioeconomic status (Gordon, Cordova, Hawrilenko, Gray, & Martin, 2014), which could yield important contributions to recent research with low-income couples (Wilde & Doherty, 2013).

Positive parenting practices have proven to be among the hardest parenting skills to enact and maintain, and yet are essential to fostering healthy family development. This study added to the debate that marital intervention studies could have broader influences on parenting domains, specifically suggesting a protective effect of acceptance-based couple interventions for maintaining warm, involved, parent-child relationships. Improving acceptance within couples to shield positive parenting was especially meaningful for fathers, whose parenting has repeatedly been found, as it was here, to be particularly sensitive to dynamics within romantic relationships. Understanding how positive emotional processes within overall relationship health are associated with the parents’ ability to nurture their children could contribute to subsequent innovative approaches toward healthier families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was provided by a grant (R01HD45281) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the last author.

Special thanks to David A. Kenny for his generous statistical consulting on this project.

Footnotes

The full equation includes the addition of a dummy variable for male followed by the same quantity in brackets, where the repeated measure designates the male in each couple.

Results of this study were presented at the 2013 conference for the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies

Contributor Information

Melinda Ippolito Morrill, Research Fellow, Massachusetts General Hospital, Laboratory of Adult Development, Harvard Medical School, 151 Merrimac Street, Boston, MA 02114

Matt Hawrilenko, Doctoral Student, Clark University, Frances L. Hiatt School of Psychology, 950 Main Street, Worcester, MA 01610

James V. Córdova, Professor of Psychology, Clark University, Frances L. Hiatt School of Psychology, 950 Main Street, Worcester, MA 01610

References

- Adamsons K, Buehler C. Mothering versus fathering versus parenting: Measurement equivalence in parenting measures. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2007;7(3):271–303. doi: 10.1080/15295190701498686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- August GJ, Lee SS, Bloomquist ML, Realmuto GM, Hektner JM. Dissemination of an evidence-based prevention innovation for aggressive children living in culturally diverse, urban neighborhoods: The Early Risers effectiveness study. Prevention Science. 2003;4(4):271–285. doi: 10.1023/a:1026072316380. 1389-4986/03/1200-0271/1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Defiant children: A clinician’s manual for assessment and parenting training. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5(4):323–370. doi: 10.1037//1089-2680.5.4.323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Gilstrap B, Rovine M. The Pennsylvania Infant and Family Development Project I: Stability and change in mother-infant and father-infant interaction in a family setting at one, three, and nine months. Child Development. 1984;55:692–705. doi: 10.2307/1130122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55(1):83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire - II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42(4):676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonds DD, Gondoli DM. Examining the process by which marital adjustment affects maternal warmth: The role of coparenting support as a mediator. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):288–296. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Schilo L, Taylor ZE, Ferrer E, Robins RW, Conger RD, Widaman KF. Parents’ optimism, positive parenting, and child peer competence in Mexican-origin families. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2013;13(2):95–112. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.709151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Atkins DC, Baucom B, Yi J. Marital status and satisfaction five years following a randomized clinical trial comparing traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(2):225–235. doi: 10.1037/a0018132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Jacobson NS. Frequency and Acceptability of Partner Behavior Inventory. University of California; Los Angeles: 1997. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL. Integrating models of interdependence with treatment evaluations in marital therapy research. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(4):529–542. 0893-3200/98. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV. Acceptance in behavior therapy: Understanding the process of change. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24:213–226. doi: 10.1007/BF03392032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV, Fleming CE, Morrill MI, Hawrilenko M, Sollenberger JW, Harp AG, Gray TD, Darling EV, Blair JM, Meade AE, Wachs K. The Marriage Checkup: A randomized controlled trial of annual relationship health checkups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(4):592–604. doi: 10.1037/a0037097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV, Scott RL, Dorian M, Mirgain S, Yaeger D, Groot A. The marriage checkup: A motivational interviewing approach to the promotion of marital health with couples at-risk for relationship deterioration. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(4):301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova JV, Warren LZ, Gee CB. Motivational interviewing with couples: An intervention for at-risk couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2001;27:315–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne LW, Murrell AR. The joy of parenting. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies P. Marital conflict and children. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Maujean A, Fraser JA. Parenting and conduct problems in children: Australian data and psychometric properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Australian Psychologist. 2003;38:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ. The intentional family. N.Y: Addison-Wesley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT. A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review. 2009;12:255–270. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3. doi:10/1007/210567-009-00463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwairy M. Parental acceptance-rejection: a fourth cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;(19):30–35. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9338-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychology Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamm ES, Grolnick WS, Diggins E. Effects of a new preventive intervention on parental attitudes and autonomy support: The Parent Check-In. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Child Development; Philadelphia, PA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. University of Alabama; 1991. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Fruzzetti AE, Iverson KM. Mindfulness, acceptance, validation, and “individual” psychopathology in couples. In: Hayes Steven C, Follette Victoria M, Linehan Marsha M., editors. Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioral Tradition. New York: The Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Garson D. Structural Equation Modeling. North Caroline State University School of Public and International Affairs, Statistical Associates Publishing, Blue Book Series; 2012. New March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gattis KS, Simpson LE, Christensen A. What about the kids? Parenting and child adjustment in the context of couple therapy. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(6):833–842. doi: 10.1037/a0013713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg WA, Easterbrooks MA. Role of marital quality in toddler development. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20(3):504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KC, Cordova J, Hawrilenko M, Gray TD, Martin K. Relationship Rx: Initial findings for a brief intervention for low-income couples. In: Doss BD Chair, editor. Brief Interventions for At-Risk and Distressed Couples; Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Philadelphia, PA. 2014. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Harwood MD, Eyberg SM. Child-directed interaction: prediction of change in impaired mother-child functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(3):335–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9025-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes DJ, Dadds MR. Assessing parenting practices through parent-report and direct observation during parent-training. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15:555–568. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Follette VM, Linehan MM. Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition. Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH, Thomas SL, Tabata LN. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling with IBM SPSS. New York: Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:64–78. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Christensen A. Acceptance and change in couple therapy. New York: Norton; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Rakow A, Colletti CJ, McKee L. The specificity of maternal parenting behavior and child adjustment difficulties: a study of inner-city African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(2):181–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. In: McHale James P, Cowan Philip A., editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. The Kazdin method for parenting the defiant child. New York: Hougton Mifflin; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA. Dyadic data analysis using multilevel modeling. In: Hox Joop J, Roberts Kyle J., editors. Handbook for advanced multilevel analysis. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. pp. 335–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kochanska G. Mothers’ power assertion; children’s negative, adversarial orientation; and future behavior problems in low-income families: Early maternal responsiveness as a moderator of the developmental cascade. Journal of Family Psychology. 2015;29(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0038430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Prisco TR, Adams EE. Mother-child and father-child mutually responsive orientation in the first 2 years and children’s outcomes at preschool age: Mechanisms of influence. Child Development. 2008;79(1):30–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolak AM, Volling BL. Parental expressiveness as moderator of coparenting and marital relationship quality. Family Relations. 2007;56:47–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros CD, Papp LM, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Spillover between marital quality and parent-child relationship quality: Parental depressive symptoms as moderators. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28(3):315–325. doi: 10.1037/a0036804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann T, Bodenmann G, Cina A. The efficacy of couples coping enhancement training (CCET) in improving relationship quality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(8):940–959. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB, John RS. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1037./0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W, Amato P, Day RD, Lamb ME. Scholarship on fatherhood in the 1990s and beyond. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62(4):1173–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, Olson A, Forehand R, Massari C, Jones D, Gaffney C, Zens MS. Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: The roles of positive parenting and gender. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9070-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Forehand R, Rakow A, Reeslund K, Roland E, Hardcastle E, Compas B. Parenting specificity: An examination of the relation between three parenting behaviors and child problem behaviors in the context of a history of caregiver depression. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(5):638–658. doi: 10.1177/0145445508316550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee LG, Jones DJ, Forehand R, Cuellar J. Assessment of parenting style, parenting relationships, and other parenting variables. In: Reynolds CR, editor. Handbook of Psychological Assessment of Children and Adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin TL. Parent-child interaction therapy. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development. 1985;56:289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill MI, Fleming CE, Harp AG, Sollenberger JW, Darling EV, Córdova JV. The Marriage Checkup: Increasing access to marital health care. Family Process. 2011;50(4):471–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2011.01372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MT, Cox MJ. Marital conflict and the development of infant-parent attachment relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11(2):152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family processes. Eugene, Oregon: Castalia Publishing Co; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Brown GL, Cannon EA, Mangelsdorf SC, Sokolowski MS. Maternal gatekeeping, coparenting quality, and fathering behavior in families with infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(3):389–398. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Knoll N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. International Journal of Psychology. 2007;42(4):243–252. doi: 10.1080/00207590701396641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Johnson C. The impact of marital and social network support on quality of parenting. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of Social Support and the Family. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E, Johnson S, Snyder T. Six dimensions of parenting: A motivational model. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2005;5(2):175–235. doi: 10.1207/215327922par0502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sollenberger JS, Fleming CE, Darling EV, Morrill MI, Gray TD, Hawrilenko MJ, Córdova JV. The Marriage Checkup: A public health approach to marital wellbeing. The Behavior Therapist 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Field CJ. Psychological aggression by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, and severity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(4):795–808. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MM, Fabricius WV, Cookston JT, Parke RD, Coltrane S, Braver SL, Saenz D. Marital problems, maternal gatekeeping attitudes, and father-child relaitonships in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(4):1208–1218. doi: 10.1037/a0035327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43(3):692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current population survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements. 2013 Nov 30; Retrieved November 30, 2013, from http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/famsoc1.asp.

- Wachs K, Córdova JV. The Relational Acceptance Questionnaire (RAQ) Department of Psychology, Clark University; Worcester, Massachusetts: 2007. Unpublished measure. [Google Scholar]

- Wang LP, Maxwell SE. On disaggregating between-person and within-person effects with longitudinal data using multilevel models. Psychological Methods. 2015;20(1):63–83. doi: 10.1037/met0000030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/met0000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. The long-term effects of a videotape modeling parent-training program: Comparison of immediate and 1-year follow-up results. Behavior Therapy. 1982;13:702–714. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.