Abstract

This study examined mediators of a brief couples intervention. Intimate safety, acceptance, and activation were examined in two roles: their contribution to marital satisfaction gains in the first two weeks after treatment (contemporaneous effects), and how early changes in the mediators influenced longer-term changes in marital satisfaction over two years of follow-up (lagged effects). Married couples (N = 215) were randomized to intervention or wait-list control and followed for two years. Latent change score models were used to examine contemporaneous and time-lagged mediation. A booster intervention in the second year was used for a replication study. Changes in intimate safety and acceptance were uniquely associated with contemporaneous treatment effects on relationship satisfaction in year one, but only acceptance was uniquely associated with contemporaneous effects in year two. With respect to lagged effects, early changes in acceptance partially mediated later changes in marital satisfaction in year one, whereas the same effect for intimate safety was marginally significant. These lagged paths were moderate in size and indirect effects were small. No lagged effects were significant in year two. Changes in activation were not significant as either a contemporaneous or lagged predictor of changes in relationship satisfaction. This study found moderate support for acceptance and more limited support for intimate safety as mediators of short and long-term treatment response, suggesting that these processes play an important role in sustaining marital health.

Keywords: marriage, mediation, brief intervention, acceptance, intimacy

A stream of reviews over the past fifteen years has found few studies and little empirical support for hypothesized mechanisms of change in relationship interventions (Lebow, 2000; Snyder, Castellani & Whisman, 2006; Wadsworth & Markman, 2012; Bradbury & Lavner, 2012), despite increasingly widespread agreement amongst couples researchers (Wadsworth & Markman, 2012) and within the broader psychotherapy research community (Kazdin, 2001) of the importance of process research. The paucity of findings for change mechanisms is not just an issue for relationship research, but as Kazdin repeatedly notes, it is a shortcoming of psychotherapy research in general (Kazdin, 2001; Kazdin, 2007). Kazdin (2007) suggests a number of important reasons to understand mechanisms of change, including: understanding the critical components necessary to build better treatments; understanding which components must not be diluted in transition from the lab to more resource-limited real world settings; bringing order and parsimony to the broad array of treatments currently available; clarifying the connection between treatment and a broad range of more distal outcomes; and identifying moderators of treatment.

The present study examines mediators of change in the Marriage Checkup (MC; Cordova et al., 2005; Cordova et al., 2014), a brief, preventive intervention for couples at-risk of relationship deterioration. We situate the MC’s theory of change in the existing body of process research and discuss methodological considerations and recent statistical innovations that enable us to best marry the theory of change to the analytic method. We model couples’ processes of change as occurring in two discrete stages: an early period surrounding the intervention where couples achieve rapid gains in both the mediator and outcome variables, and a longer-term follow-up period where early gains in mediators may operate to prevent the subsequent deterioration of relationship satisfaction.

Process Research in Couples Interventions

Christensen and colleagues (Christensen et al., 2010; Benson, McGinn & Christensen, 2012) have argued that couples interventions are unified by their influence on five common principles, which underlie all of the changes in marital satisfaction created by these interventions. The principles are: (1) facilitating shared narratives and dyadic views of the relationship, (2) modifying dysfunctional interactional behavior (e.g., physical or emotional abuse), (3) eliciting avoided private behavior, (4) improving communication, and (5) promoting strengths. Although Christensen and colleagues created this framework with specific reference to couple therapy, we believe these principles are also usefully applied as an organizing framework for brief, preventive, relationship interventions.

Two main types of interventions target the prevention of couple distress: skills-based relationship education, and assessment and feedback interventions (Halford & Snyder, 2012). Skills-based interventions, such as the Premarital Relationship Enhancement Program (PREP; Markman, Renick, Floyd, Stanley & Clements, 1993), Couple CARE (Halford, Moore, Wilson, Dyer & Farrugia, 2006), and Relationship Enhancement (Guerney & Maxson, 1990) primarily target satisfied couples and aim to change risk factors that have been identified as both malleable and useful in forecasting long-term trajectories of relationship satisfaction. These programs impart knowledge and skills in a curriculum format. Although the interventions vary with respect to their content and may touch on any of Christensen’s proposed common principles, the most central and recurring theme is a focus on improving communication (Halford & Snyder, 2012).

Research on mediators of change in skills interventions has been inconclusive, with few studies showing associations between changes in skills and changes in marital satisfaction (for reviews, see Wadsworth & Markman, 2012, and Halford & Snyder, 2012), and some studies showing associations that were directionally opposite from their hypotheses (Baucom, Hahlweg, Atkins, Engel & Thurmaier, 2006; Schilling, Baucom, Burnett, Allwen & Ragland, 2003). Several hypotheses have been put forth to reconcile these inconsistencies, including the possibility that benefits are driven by couples with the poorest baseline skills (Halford & Snyder, 2012) and the possibility that distressed couples are not deficient in skills, but simply do not employ them at home (Snyder & Schneider, 2002). It may also be the case that topographically similar behaviors function differently in the context of different relationships (e.g., McNulty, 2010).

In their examination of mediation effects in couple therapy, Doss and colleagues (2005) showed that behavior exchange mediated gains in the first half of therapy, whereas acceptance mediated gains in both the first and second halves of therapy. A notable difference between that study and the present one is that Doss and colleagues examined only contemporaneous effects, limiting the degree to which they could discern causal direction.

To our knowledge, no published studies have tested hypothesized mediators in assessment and feedback interventions, perhaps because there have been fewer assessment and feedback interventions (Halford & Snyder, 2012) and their individually tailored nature implies more complex or multifaceted mediating processes. Assessment and feedback interventions such as PREPARE (Olson, Fournier & Druckman, 1996), RELATE (Busby, Holman & Taniguchi, 2001), and the Marriage Checkup (MC; Cordova et al., 2014) administer batteries of questionnaires and use the results to provide feedback designed to help couples consolidate strengths and address weaknesses. These interventions may also include other targeted, within-session components, such as the MC’s focus on building intimacy bridges (Morrill & Cordova, 2010). In some respects, process research on individually tailored interventions such as the MC may face a complex task, since the proximal targets of change may be different between couples. For example, some couples might learn communication skills, while others might work on identifying their relational patterns of behavior or increasing avenues for expressing affection. However, the complexity of process research depends not just upon topological differences in the treatment approach, but also upon the underlying theory of change. For example, the MC teaches communication skills to some couples in the direct service of fostering a more intimate and accepting atmosphere in the relationship. In this vein, Doss and colleagues (2005) suggested that one potential reason that much of couples intervention mediation research has been unsuccessful is that interventions may be targeting and measuring one inactive ingredient, but hitting another, active ingredient. Under this reasoning, interventions would only be successful to the extent they moved the “true” mediator. Supporting this hypothesis, Rogge, Cobb, Lawrence, Johnson and Bradbury (2013) found that skills interventions performed more poorly with respect to the skills they targeted but produced positive effects in other, untargeted domains, implying that relationship skills may not be the active ingredient in skills-based interventions.

Doss and colleagues (2005) also suggested that the failure of tertiary couple therapy to demonstrate mediating relationships could in part be due to pre-post designs that do not disentangle the nuance of change or adequately reflect the theoretical model. Conceptualizing processes as occurring in phases is particularly relevant to brief interventions, whose effects may consist of two discrete phases: an early phase when a broad array of relationship skills and processes may change at once, followed by a gear-shift to a longer term follow-up over which the role of active preventive ingredients may unfold. Thus, individuals could have differential early responses to treatment, and differential patterns of long-term response conditioned on their early responses.

The Marriage Checkup

The MC is conceptualized as the relationship health equivalent of an annual physical health checkup, with the goal of attending to emerging issues before they lead to more severe distress. The MC theorizes that some degree of hurt is inevitable in intimate relationships and that helping couples find adaptive responses to their problematic issues early can foster immediate increases and prevent subsequent deterioration in marital satisfaction (Cordova, 2013). In keeping with the model of the annual checkup, the MC offers booster sessions targeted at detecting unhealthful, emergent patterns in the relationship dynamic, as small external stresses can accumulate over time to negatively impact the functioning of the relationship (Repetti, Wang & Saxbe, 2009). In service of this goal, the MC targets three mediating processes: intimate safety, acceptance, and behavioral activation.

Intimacy is conceptualized as a behavioral process, where one person engages in vulnerable behavior in relation to their partner (Cordova & Scott, 2001). When the behavior is reinforced by the partner’s accepting and non-punitive response, intimate behaviors are theorized to happen more frequently, and when punished, less frequently. Intimate safety refers to a person’s felt sense that they are safe being their authentic, vulnerable self in relation to their partner. A higher degree of intimate safety should lead to a larger proportion of approach behaviors, even and perhaps especially in times of inevitable hurts and stressors, whereas a lower degree of intimate safety is hypothesized to lead towards fewer approach behaviors and withdrawal from the relationship, particularly in times of hurt. Intimate safety falls quite clearly under Christensen’s third principle, eliciting avoided private behavior.

The concept of partner acceptance is borrowed from Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy (Jacobson & Christensen, 1996), which theorizes that accepting unwanted behaviors expands couples’ behavioral repertoires to make space for new, more reinforcing interactions (Cordova, 2001). Acceptance fits most easily into Christensen’s first principle, theoretically functioning to help couples see their partner and their interactions in a different light, enabling couples to create more adaptive responses to situations that previously generated relationship distress. The MC targets acceptance by utilizing several techniques from IBCT (e.g. uncovering soft emotions, eliciting understandable reasons, and identifying themes and patterns) in response to each partner’s concern during the Assessment session.

The final hypothesized mediator, activation, is thought to function by uniting couples towards taking concrete actions intended to improve their relationship satisfaction. During the Feedback session, couples are provided a menu of targeted, therapist-generated options for actively addressing their concerns and the couple also works together to generate several of their own ideas. These actions could touch on any of Christensen’s proposed common couple intervention principles, but are unified by the couple’s engagement in taking concrete steps to improve their relationship.

In line with Christensen and colleagues’ (2010) notions of unifying processes and Doss and colleagues’ (2005) discussion of mediators that are targeted versus those that are hit, the MC uses a number of different means to achieve gains in intimate safety, acceptance, and activation. While the MC might address communication skills such as the speaker-listener technique with some couples and encourage others to gain a deeper understanding of their relationship patterns or vulnerable emotions, these techniques are all employed in the service of promoting gains in intimate safety, acceptance, and activation.

The present study examines data used in the outcome analysis of the largest clinical trial to date of the MC (Cordova et al., 2014). Over the course of that clinical trial, couples attended an assessment and feedback session at baseline and a booster assessment and feedback session one year later. Effect sizes at two weeks post treatment were small and remained relatively steady across the first year, spiked after the booster session, then tended to decline across the second year. Given that the bulk of the treatment effect was realized within the two-week period after treatment, the MC displayed the gearshift in trajectories characteristic of many brief interventions, suggesting that couples experienced two discrete phases of change.

Present Aims

The present study aims to test the Marriage Checkup’s theory of change. We conceptualized change in the MC as occurring in two discrete phases, one consisting of a quick shock to the system where many variables changed at once and where we might see contemporaneous mediation effects, and the longer-term period over which longitudinal preventive effects would become apparent. We hypothesized that early changes in intimate safety, acceptance, and activation would be related to early gains in relationship satisfaction. We also hypothesized that those early gains in the mediators would be associated with subsequent changes in marital satisfaction, whereas early changes in marital satisfaction would not be associated with subsequent changes in the mediators. Finally, we hypothesized that this pattern of results would replicate over the booster session that occurred in year two.

Method

Participants

Participants were 215 married couples (N = 430 individuals) whose relationship satisfaction ranged from severely distressed to highly satisfied. Six couples were same-sex and 209 were opposite-sex. To be eligible to participate, couples needed to be married and cohabiting, and they could not currently be attending couples therapy. Ages of participants ranged from 20 to 78 years, with the average age of participants 45.7 years (SD = 11.3). Most participants were Caucasian (93.9%). On average, couples were married 15.1 years (SD = 12.0) and had 2.0 (SD = 1.5) children. Participants had a median annual household income of $75,000 to $99,000 with the median level of education being a bachelor’s degree. Means and standard deviations of study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Variable | base | 4wk | 1yr | 1yr 4wk | 2yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QMI | |||||

| Control | 36.45 (8.39) | 36.57 (7.91) | 37.41 (7.43) | 37.23 (8.12) | 37.74 (8.28) |

| MC | 36.18 (8.31) | 38.39 (6.76) | 37.89 (7.57) | 38.94 (6.61) | 37.87 (7.25) |

| GDS | |||||

| Control | 52.62 (9.50) | 50.87 (9.40) | 50.61 (9.08) | 50.7 (9.69) | 51.38 (8.49) |

| MC | 52.34 (9.20) | 50.56 (8.53) | 49.09 (9.12) | 48.31 (8.67) | 49.85 (8.94) |

| RAQ | |||||

| Control | 4.06 (0.77) | 4.14 (0.80) | 4.15 (0.81) | 4.09 (0.85) | 4.19 (0.81) |

| MC | 3.99 (0.88) | 4.25 (0.80) | 4.24 (0.75) | 4.38 (0.70) | 4.27 (0.75) |

| ISQ | |||||

| Control | 3.08 (0.46) | 3.12 (0.49) | 3.12 (0.52) | 3.10 (0.62) | 3.12 (0.55) |

| MC | 3.02 (0.52) | 3.16 (0.47) | 3.20 (0.47) | 3.27 (0.50) | 3.19 (0.51) |

| SCQ | |||||

| Control | 3.26 (0.89) | 3.4 (0.88) | 3.36 (0.89) | 3.19 (0.86) | 3.33 (1.03) |

| MC | 3.29 (0.85) | 3.73 (0.81) | 3.66 (0.77) | 3.51 (0.79) | 3.54 (0.86) |

Note. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Descriptives ignore clustering due to couple and are based on available data at each assessment point. QMI = Quality of Marriage Index. GDS = Global Distress Subscale of Marital Status Inventory-Revised. ISQ = Intimate Safety Questionnaire. RAQ = Relationship Acceptance Questionnaire. SCQ = Stages of Change Questionnaire.

Procedures

Participants were randomized into intervention and wait-list control groups. Treatment couples attended an assessment and feedback session at baseline and again one year later. Couples completed questionnaires at baseline, the end of the feedback session, two-week, six-month, and one-year follow-up. Over the second year, data were collected following the same pattern as the first year. Control couples attended a MC at the end of two years. All activities were approved by the Clark University Institutional Review Board. By the two-year follow-up, 27% of the sample had dropped out. This study included all participants, making it a full intent-to-treat analysis. In previous work (Cordova et al., 2014), dropout status was found not to bias estimates of mediator or outcome variables, although differential dropout (13 treatment couples vs. 1 control couple) between randomization and intervention suggested that some couples—after learning of their randomization—chose not to attend the MC. More detailed information on procedures and a detailed analysis of dropouts can be found in Cordova and colleagues (2014).

Measures

Marital satisfaction was assessed using the six-item Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, 1983), and the 22 true/false item Global Distress Subscale of the Marital Satisfaction Inventory—Revised (GDS; Snyder, 1997). The QMI sums six items, with five items rated 1–7, and a global assessment rated 1–10, producing a possible range of scores of 6–45. The GDS is normed separately by sex, with a mean score of 50 and standard deviation of 10. Cronbach’s alphas were .97 for the QMI and .93 for the GDS.

Intimate safety was assessed using the 28-item Intimate Safety Questionnaire, which measures the degree to which partners feel safe being vulnerable across different relationship domains. All items were scored 0–4, with 0 representing “Never” and 4 representing “Always.” Sample items include, “I feel comfortable telling my partner things I would not tell anyone else,” “When I need to cry I go to my partner,” and “Sex with my partner makes me uncomfortable.” A validation study in a different sample from the present one (Cordova, Blair & Meade, 2010) found support for four different domains of intimate safety assessed in the questionnaire, with the best fitting model indicating a global factor of intimate safety underlying the four specific domains. Higher intimate safety scores were associated with greater commitment and trust, and intimate safety was measurably distinct from trust, shyness, extraversion, and a traditional measure of intimacy. To further assess discriminant validity for the current study, we added the six items of the Quality of Marriage Index to the model, and the best fitting model identified the global intimate safety factor as distinct from marital satisfaction. In the present analysis, we used the second order factor by taking the mean of all 28 items. Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

Acceptance was measured using the Relationship Acceptance Questionnaire (RAQ), a global measure of acceptance developed for the Marriage Checkup project based on the theory of acceptance described by Cordova (2001). The RAQ measures acceptance directed towards the partner and acceptance felt from the partner. Consistent with Cordova et al. (2014), this study focused exclusively on the 13-items measuring felt acceptance. Felt acceptance items include, “I feel like my partner accepts me as a person, ‘warts and all’,” “My partner always wants to change me,” and “I am comfortable just being myself around my partner.” All items were scored 1–5, strongly disagree to strongly agree. The mean was taken as the scale score.

A confirmatory factor analysis performed with the present sample found the hypothesized two-factor solution, felt acceptance and acceptance directed towards the partner, to fit the data well. To assess discriminant validity, we added the Quality of Marriage Index, dedication commitment (Stanley & Markman, 1992), and affective communication (Snyder, 1997) to the model, first in pairwise fashion, and finally all together. All models identified felt acceptance as conceptually distinct but correlated with all three variables, with correlations of .65, .54, and .72 with marital quality, commitment, and affective communication, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for felt acceptance was .94.

Activation was measured with the action subscale of a modified version of the 32-item University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale—Psychotherapy (McConnaughy, Diclemente, Prochaska & Velicer, 1989). The scale was modified to ask specifically about a couple’s relationship. For example, one item in the original scale says, “Anyone can talk about changing; I’m actually doing something about it,” whereas the version in the present study said, “Anyone can talk about improving their marriage; I’m actually doing something about it.” Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

In the present sample, correlations of intimate safety, marital satisfaction, and acceptance were high. Correlations of intimate safety with marital satisfaction ranged from .64 to .68, acceptance with marital satisfaction ranged from .60 to .67, and intimate safety with acceptance ranged from .69 to .71. Despite the high cross-sectional correlations, there is a rich literature delineating the theoretical differences of these mechanisms, and earlier research on the MC (Cordova et al., 2014) has substantiated that while interrelated, these variables moved somewhat differently over time throughout the study. Beyond the steps described above, we took additional steps in the analytic strategy to ensure conceptual distinction throughout the analysis.

Data Analytic Strategy

Collins (2006) stated that strong longitudinal research integrates three elements: an articulated theoretical model of change, a temporal design with intervals that capture the unfolding of the process, and a statistical model that operationalizes the theoretical model. In the MC study, more measures were collected in the time immediately surrounding the treatment period as change was expected to occur more rapidly in the weeks immediately surrounding treatment and more slowly over the follow-up period. The pattern of results presented in the Marriage Checkup two-year outcome study indicated that the process and outcome variables tended to change in close proximity to one another (Cordova et al., 2014). Therefore, the two central challenges of this analysis were simultaneously disentangling changes that were hypothesized to occur in close temporal proximity and understanding the downstream effects of early changes. MacKinnon (2008) suggested that the most useful type of model for this design might be the latent change score model (McArdle, 2009), which directly model between-person differences in within-person change. Moreover, latent change score models parcel out measurement error, examine change as a latent rather than observed variable, and incorporate the effects of initial status on the amount of change, addressing a number of limitations of observed change scores. We used latent change score models to test longitudinal effects in the MC.

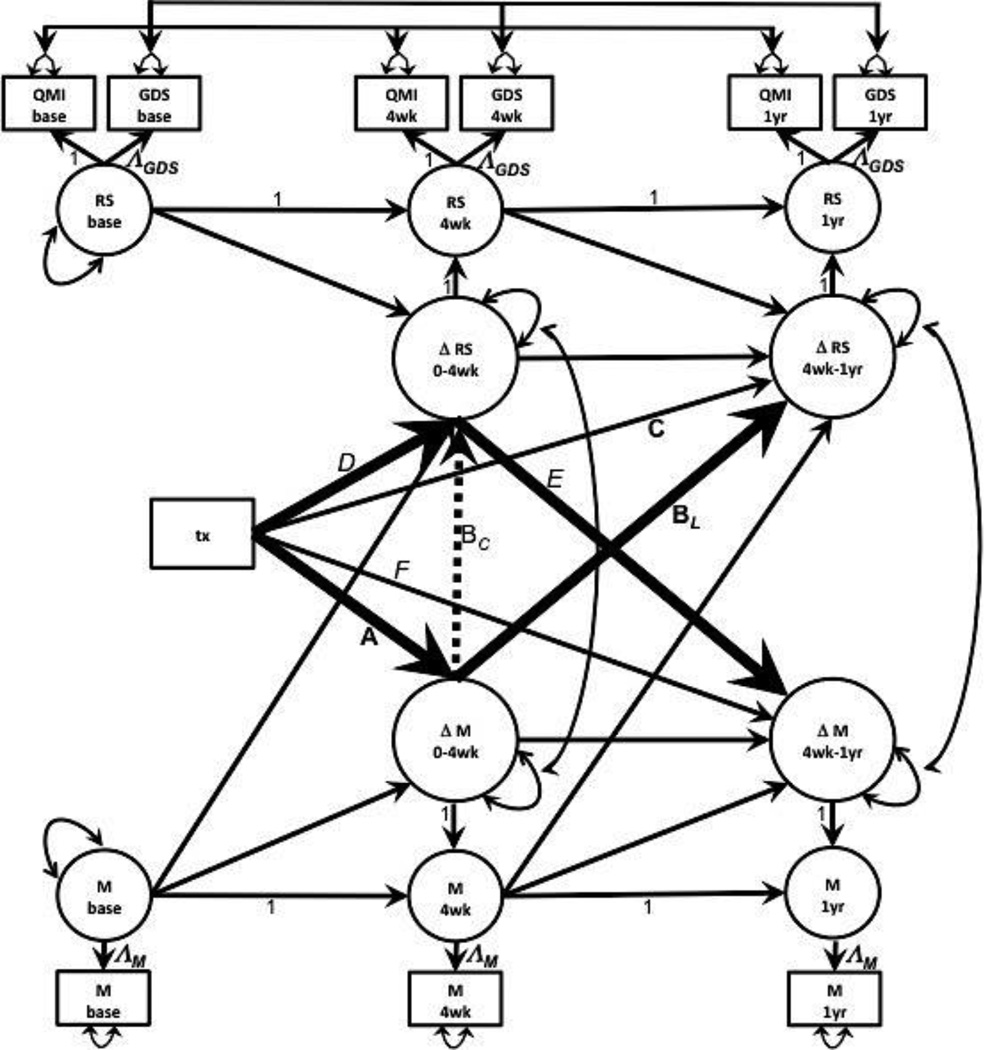

We divided our analysis into two parts. Substantively, these parts describe the immediate mechanisms of action and the processes associated with long term preventive effects. Because we hypothesized that our mediators would be associated with both rapid short term gains and long-term preventive effects, the most natural mapping of this theory to our design and hypotheses was to examine contemporaneous effects in the period of time immediately surrounding treatment, and then test how treatment gains in mediators over that brief window were associated with marital satisfaction over the next 11 months of the follow-up period. The lagged-change component of this study is particularly important, as Kazdin (2007) has argued that the demonstration of temporal precedence is the “Achilles’ heel of treatment studies” (p. 5). A path diagram of the conceptual model is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Note. The paths of primary interest are bolded. M = mediator. RS = relationship satisfaction. The contemporaneous model includes only data through 4 weeks, and path Bc represents a path that is only in the contemporaneous model (it is replaced by the pictured covariance in the lagged model).

The first part of the analysis examined change between the pre-intervention and two-week post intervention time points, corresponding to the “shock to the system” component of treatment. This analysis had the drawback of examining only contemporaneous change, but allowed a straightforward analysis of the size of mediation effects and the simultaneous inclusion of multiple mediators in the model. The second part of our analysis tested whether the amount of change in the mediator over the active treatment phase was related to the amount of change in marital satisfaction during the subsequent longer-term follow-up period (Path BL in Figure 1). Because the treatment effects peaked by the two-week follow-up period, this analysis can be considered a test of those intervention ingredients that have enduring contributions to the sustainment of treatment gains and prevention of relationship deterioration.

Due to the high intercorrelations between intimate safety, acceptance, and marital satisfaction, it was important to verify that mediators were acting above and beyond the effect of early changes in relationship satisfaction. Therefore, we also included paths from each variable’s earlier change to its own subsequent change.

We first modeled each variable and each sex separately to ensure good local fit before combining them to form the larger multivariate models. Preliminary models indicated that partners were largely indistinguishable, so we simplified our final models by treating couple-level nonindependence as a nuisance term, using a sandwich estimator to calculate standard errors, rather than modeling partners in parallel. This strategy enabled us to include the six same-sex couples in the analysis. The tradeoff here is parsimony versus complexity; the covariance structure was greatly simplified, increasing model stability and decreasing researcher degrees of freedom in the nuisance part of the model. This comes at a cost of not explicitly modeling partner effects, which were not part of our planned comparisons.

All analyses were performed with Mplus Version 7.3. Despite several significant chi square tests, all other fit statistics indicated excellent fit. Fit statistics are presented in Table 2. All results are presented in standard deviation units, calculated by dividing model parameters by the square root of their intercept variance.

Table 2.

Fit Statistics for Structural Equation Models

| Model | χ2 (df) | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Week Contemporaneous | 81.23 (29)*** | 0.07 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| 1yr 4wk Contemporaneous | 54.69 (29)*** | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.97 |

| 1 Year Cross-Lagged Intimacy | 32.37 (20)* | 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 1 Year Cross-Lagged Acceptance | 29.26 (20) | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| 1 Year Cross-Lagged Activation | 47.82 (20)** | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| 2 Year Cross-Lagged Intimacy | 16.63 (20) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 Year Cross-Lagged Acceptance | 19.76 (20) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 Year Cross-Lagged Activation | 40.37 (20)** | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

Results

Contemporaneous Mediation

Contemporaneous change was modeled with a series of latent change score models, which examined the change between pre-intervention and two-weeks post-intervention, controlling for the initial level of each variable in the analysis. Initially, each mediator was examined individually with the outcome. The final model, presented in Table 3, included all three mediators simultaneously. When examined individually, changes in all three mediators (Path BC) were significantly associated with changes in relationship satisfaction, with activation having the smallest association (β = 0.10, p = .027). In the final model, activation’s association with changes in relationship satisfaction became nonsignificant, but the associations between changes in intimate safety and acceptance with changes in relationship satisfaction remained significant. Asymmetric confidence intervals of the indirect effect were generated with bias-corrected bootstrapping and indicated the indirect effects of the intervention through intimate safety and acceptance were statistically significant, equivalent in size and together, accounted for 83% of the treatment effect. In the second year replication including all three mediators, only changes in acceptance were significantly associated with changes in marital satisfaction, although when modeled on its own, changes in intimate safety were also significantly associated with treatment gains (β = .28, p < .001). For the second year, the confidence interval of the indirect effect of acceptance excluded zero, and acceptance accounted for the entire treatment effect.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates (SD Units) for Contemporaneous Mediation Models

| Year 1 | Year 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p |

| Tx → Δ RS0–4wk | 0.05 (0.06) | .361 | 0.01 (0.06) | .832 |

| Tx → Δ RAQ0–4wk (A1 path) | 0.22 (0.07) | .001 | 0.22 (0.06) | <.001 |

| Tx → Δ ISQ0–4wk (A2 path) | 0.23 (0.07) | .001 | 0.15 (0.06) | .014 |

| Tx → Δ SCQ0–4wk (A3 path) | 0.37 (0.10) | <.001 | 0.16 (0.09) | .072 |

| level RS → Δ RS0–4wk | −0.29 (0.07) | <.001 | −0.20 (0.09) | .024 |

| level RAQ → Δ RS0–4wk | 0.11 (0.05) | .026 | 0.08 (0.06) | .176 |

| level ISQ → Δ RS0–4wk | 0.10 (0.05) | .057 | 0.07 (0.06) | .203 |

| level SCQ → Δ RS0–4wk | −0.01 (0.03) | .682 | 0.00 (0.03) | .900 |

| Δ RAQ0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk (B1 path) | 0.31 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.28 (0.07) | <.001 |

| Δ ISQ0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk (B2 path) | 0.25 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.14 (0.10) | .168 |

| Δ SCQ0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk (B3 path) | −0.01 (0.03) | .867 | 0.00 (0.04) | .961 |

| Total Tx → Δ RS0–4wk (sum of direct + indirect paths) | 0.18 (0.07) | .012 | 0.10 (0.07) | .146 |

| Indirect Effects | ||||

| Tx → Δ RAQ0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk | 0.07 [0.03,0.15] | 0.09 [0.03,0.25] | ||

| Tx → Δ ISQ0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk | 0.08 [0.03,0.17] | 0.02 [−0.04,0.09] | ||

| Tx → Δ SCQ0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk | 0.01 [−0.02,0.05] | 0.01 [−0.01,0.05] | ||

Note. Brackets denote bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. tx=treatment. RS=Relationship Satisfaction. RAQ = Relationship Acceptance Questionnaire. ISQ=Intimate Safety Questionnaire. SCQ=Stages of Change Questionnaire.

Time-lagged Mediation

Time-lagged processes were also examined with latent change score models, allowing the change in the mediators over the first month of the study—where the treatment effect peaked—to predict subsequent changes in satisfaction over the next 11 months of follow-up for both years one and two (Path BL). Because the bivariate models grew quite large, analyses were performed pairwise, with a separate model examining the relationship of each mediator with relationship satisfaction. Table 4 presents the results of the bivariate longitudinal analyses. Pathways not of substantive interest have been omitted from the table for parsimony. Full results can be obtained from the first author.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates (SD Units) for Time-Lagged Latent Change Score Models

| Acceptance | Intimate Safety | Activation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p | B (SE) | p |

| Year 1 | ||||||

| Tx → Δ M0–4wk (A path) | 0.23 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.22 (0.07) | .001 | 0.39 (0.10) | <.001 |

| Δ M0–4wk → Δ RS4wk–1yr (BL path) | 0.20 (0.08) | .016 | 0.15 (0.09) | .076 | 0.01 (0.05) | .913 |

| Total Tx → Δ RS4wk–1yra (C + all indirect paths) | 0.00 (0.08) | .976 | −0.02 (0.08) | .819 | −0.01 (0.08) | .850 |

| Δ RS0–4wk → Δ RS4wk–1yr | −0.32 (0.20) | .103 | −0.29 (0.19) | .135 | −0.18 (0.17) | .273 |

| ISQ level → Δ RS4wk–1yr | −0.10 (0.07) | .182 | −0.02 (0.09) | .850 | 0.06 (0.06) | .264 |

| RS level → Δ RS4wk–1yr | −0.07 (0.09) | .432 | −0.14 (0.09) | .138 | −0.14 (0.05) | .003 |

| Δ RS0–4wk → Δ M4wk–1yr (E path) | −0.17 (0.12) | .165 | 0.19 (0.16) | .234 | −0.17 (0.17) | .293 |

| Tx → Δ M0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk (A * BL paths) | 0.04 [0.01,0.09] | 0.02 [0.00,0.05] | 0.00 [−0.03,0.04] | |||

| Year 2 | ||||||

| Tx → Δ M0–4wk (A path) | 0.22 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.15 (0.06) | .015 | 0.18 (0.09) | .041 |

| Δ M0–4wk → Δ RS4wk–1yr (BL path) | −0.26 (0.16) | .100 | −0.14 (0.12) | .232 | 0.06 (0.05) | .259 |

| Total Tx → Δ RS4wk–1yra (C + all indirect paths) | −0.03 (0.10) | .765 | −0.03 (0.10) | .778 | 0.01 (0.10) | .934 |

| Δ RS0–4wk → Δ RS4wk–1yr | −0.10 (0.39) | .804 | −0.23 (0.35) | .514 | −0.29 (0.29) | .323 |

| ISQ level → Δ RS4wk–1yr | 0.01 (0.10) | .933 | 0.02 (0.10) | .884 | −0.06 (0.04) | .145 |

| RS level → Δ RS4wk–1yr | −0.11 (0.11) | .303 | −0.09 (0.11) | .412 | −0.10 (0.06) | .075 |

| Δ RS0–4wk → Δ M4wk–1yr (E path) | 0.13 (0.27) | .639 | −0.11 (0.22) | .617 | −0.16 (0.27) | .538 |

| Tx → Δ M0–4wk → Δ RS0–4wk (A * BL paths) | −0.05 [−0.20,0.02] | −0.01 [−0.06,0.01] | 0.01 [−0.01,0.04] | |||

Note. M denotes mediator variable in column heading. Brackets denote 95% confidence intervals. Tx = treatment. RS = Relationship Satisfaction. RAQ = Relationship Acceptance Questionnaire. ISQ = Intimate Safety Questionnaire. SCQ = Stages of Change Questionnaire.

The delta method was used to sum all paths leading from treatment to the change in satisfaction.

The between-group differences in change in marital satisfaction over the follow-up period in both year one and year two (Path C) were not significantly different from zero, indicating that early treatment gains were largely maintained. However, indirect pathways may be significant even in the absence of a significant change in the dependent variable (MacKinnon, 2008). In this case, a significant indirect effect (Path A * Path BL) would suggest that early changes in the mediator partially explained the effect of the intervention on between-group differences in the maintenance of marital satisfaction. Over the first year of the study, early changes in acceptance were significantly associated with later changes in relationship satisfaction (Path BL). The cross-lag from change in intimate safety to later change in satisfaction (Path BL) trended in the same direction but was nonsignificant, and the effect of change in activation (Path BL) was nonsignificant. The bootstrapped indirect effects for acceptance were small but excluded zero, suggesting that treatment-related gains in acceptance influenced later changes in marital satisfaction. For intimacy, the lower bound of the indirect effect was 0.00, indicating marginal significance. None of the parameters of interest were significant in year two. To compare the pathways from early changes in the mediators to later changes in satisfaction between years one and two, we conducted Wald tests that constrained the point estimates in year two to equal those in year one. Both acceptance, Wald(1) = 8.28, p = .004, and intimate safety, Wald(1) = 6.15, p = .013, were significantly different between years one and two, meaning the lagged findings in year one did not replicate across year two.

To understand the specificity of our mediation effects, we also examined whether early changes in satisfaction led to later changes in the mediators (Path E). If this were the case, it would undermine the specificity of our pathways, increasingly the likelihood that an unobserved variable drove the mediators and marital satisfaction. All of these pathways were nonsignificant, supporting the specificity of our findings.

Effects of Control Variables

In all models, the levels (intercepts) of mediator variables and relationship satisfaction were included as covariates in order to disentangle the effects of between-person status from within-person change. The baseline level of satisfaction was consistently negatively associated with change in relationship satisfaction in the short-term follow-up to treatment (see Table 3). This change was likely driven by treatment status, where more distressed couples experienced larger gains from treatment. Additionally, when controlling for satisfaction, individuals with higher levels of acceptance at baseline tended to have larger treatment gains over both the first and second year. Relationship satisfaction did not exhibit a significant homeostatic effect in this study, as the amount of earlier change was not significantly associated with the amount of change over the follow up period. Results were not sensitive to the inclusion/exclusion of control variables.

Sensitivity Analyses

We ran sensitivity analyses to understand the failure to replicate the lagged findings. We speculated that the discrepancy between the time-lagged findings in years one and two might be due to imperfect timing of lagged measures leading to the lagged effect being washed out. We examined this by controlling for the contemporaneous effects of the mediator on the outcomes, partialling out the effect of the mediators’ changes between four weeks and one year. In this analysis, the lagged effect of intimate safety became statistically significant in year one, marginally significant in year two, and the point estimate was not significantly different between years one and two (year 1: β = 0.37, p = < .001, year 2: β = 0.21, p = .054, Wald(1) = 2.12, p = .15), whereas the lagged effect of acceptance in year two was not significantly different from year one but also not significantly different from zero (year 1: β = 0.30, p = < .001, year 2: β = 0.17, p = .14, Wald(1) = 0.84, p = .36).

Discussion

This study examined the roles of acceptance, intimate safety, and activation in promoting short and long term changes in relationship satisfaction following a brief couples’ intervention. We found the strongest support for acceptance, which consistently accounted for early treatment gains, accounted for longitudinal change in relationship satisfaction over the first year of the study, and indirectly prevented deterioration of marital satisfaction in the treatment group over the follow-up period. The association between early changes in intimate safety and subsequent changes in marital satisfaction was borderline significant over the first year of treatment but not replicated over the second year, although a sensitivity analysis found that the effects for intimate safety were statistically significant in year one and marginally significant in year two. Activation accounted for little of the variability in satisfaction on its own and none when the model included intimate safety and acceptance.

To our knowledge, this paper provides the first evidence of a time-lagged, within-person relationship between mediator and outcome in a couple intervention. Work of this nature is useful because although researchers have been successful in identifying a host of risk factors for relationship deterioration (see Stanley, 2001, for an exhaustive list), changes in these risk factors have generally not been associated with gains in relationship satisfaction, although the interventions themselves have been somewhat successful at producing satisfaction gains (Hawkins, Blanchard, Baldwin & Fawcett, 2008). To the extent that researchers can disentangle underlying processes of change, it will direct the focus of future research to a better understanding of how to manipulate these active ingredients and develop more effective interventions. This paper provides moderate support for acceptance and more limited support for intimate safety as active ingredients in the Marriage Checkup (MC). Of particular consequence is our finding that a couple’s growth in acceptance and intimate safety influenced the amount of change in relationship satisfaction over the following year, indicating that not only can intimate safety and acceptance be changed by a brief intervention, but these changes have direct bearing on how the relationship evolves in the year following the intervention. Therefore, preserving and fostering acceptance and intimate safety may be a key to preventing relationship distress.

The indirect effects in this study are small, as would be expected from a brief intervention whose total effect is small, but the study was largely successful in explaining the majority of the effects of the intervention. Understanding the pathways that transmit small effects is useful because when clinicians see couples for a short period of time, focusing that time on the active ingredients of the intervention becomes crucial. Perhaps most important are the moderately sized cross-lagged associations between the amount of earlier change in acceptance and intimate safety and later changes in marital satisfaction. Directing future efforts towards enhancing treatment’s effect on these two critical pathways may help grow and sustain marital satisfaction.

The shared variance between intimate safety and acceptance over both years of this study is consistent with Christensen and colleagues’ (Christensen et al., 2010; Benson, McGinn & Christensen, 2012) five unifying principles for mechanisms of change in couple therapy. Intimate safety falls clearly within the principle they characterize as eliciting avoided private behavior. Acceptance fits with this principle as well, but may also encourage dyadic views of the relationship. The acceptance of partner behaviors may function to reorient individuals from blame to a view of the couple in context, opening a path for more adaptive responses to situations that had previously generated relationship distress. Together, we might conceive of intimate safety and acceptance as constituting the emotional climate in a relationship. An orientation towards the dyad and an accepting stance towards unwanted behaviors may depersonalize the discussion of difficult content and foster a sense of intimate safety, just as intimate safety may aid in the development of an understanding that contextualizes sticking points, leading to understanding rather than blaming. To the extent that the emotional climate is warm, partners may be more likely to approach each other with vulnerable content, engaging in positive exchanges that enhance relationship satisfaction and confronting issues that could threaten satisfaction. The results of this study suggest that the MC functions by warming this emotional climate, leading to a greater sense of relationship satisfaction in the short term and paving the way for more approach behaviors that sustain satisfaction in the long term.

Just as we have described overlap between the principles of dyadic relationship perspectives and the elicitation of avoided private behavior, Benson, McGinn and Christensen (2012) point out that there is also overlap between the elicitation of private behavior and communication skills, as some couples may benefit from guidance in how to effectively reinforce each other’s disclosures. An exploration of this overlap may be useful for situating the current findings in the broader body of research, which has been conducted largely on relationship education and skills-based interventions. While skills-based interventions often generate gains in satisfaction, these gains tend not to be related to the skills imparted in the intervention (Wadsworth & Markman, 2012). How then might skills-based interventions be working? Many good things might happen over the course of skills interventions that have nothing to do with the acquisition of skills. While these interventions target skills, they may be successful in increasing satisfaction to the extent that they alter common principles other than communication skills. Although the present study does not directly examine the role of communication skills, it follows from our theory that altering the emotional climate through processes such as intimacy and acceptance may motivate couples to employ the skills they do have. While we strongly suspect that some relationships have grown so toxic that expertise in communication skills may be necessary for repair, this might not be the case with the average, relatively satisfied couple that attends a preventive intervention. Snyder and Schneider (2002) describe how even many distressed couples demonstrate ample communication skills in laboratory settings, but simply do not employ them at home. It stands to reason that when the emotional climate is warm, couples might be more motivated to utilize their communication skills in the service of understanding their partner and eliciting understanding from their partner. When the climate is less inviting, performances of self-disclosure may be more likely to be punished than reinforced and the preferred path for individuals may be to withdraw from their partner and withhold emotionally vulnerable content. In this way, for many couples targeted by preventive programs, communication skills may serve as a variable marker rather than a causal risk factor of relationship distress.

Reconciling Inconsistent and Null Findings

Our initial analyses indicated a statistically significant discrepancy in the size of the lagged pathways between the initial session and booster sessions, but sensitivity analyses found that controlling for contemporaneous changes over the follow-up period made the comparisons across the initial and booster sessions essentially equivalent. This discrepancy may stem from the quick erosion of the spike in the mediators seen after the booster session. Changes to the mediators produced subsequent benefits in relationship satisfaction, but those changes were short-lived. This highlights the fact that our replication was on a sample that was previously exposed to the intervention. It is possible that those couples that successfully united around issues discussed during the first checkup benefitted less from an additional checkup. Uniting around those issues may have activated a process whereby couples began engaging in fundamentally new approach behaviors. Having addressed the open issues in the first year, the therapeutic potential of the booster session may lie more in maintaining gains and less in paving new ground. The brief spikes in the emotional climate may perhaps be due to warm feelings stemming from dedicating time to take stock of the relationship, producing increased feelings of closeness in the short run but not creating a qualitative shift in couples’ patterns of relating. However, to empirically establish the true additive effect of the booster session, a design that randomizes once-treated couples into a booster session would be necessary.

The weak direct effect between activation and marital satisfaction was also surprising. We offer two potential explanations. First, it is possible that the benefit that couples derived from attending the MC was largely driven by processes that occurred in the room during treatment as opposed to what couples did in the weeks and months following treatment. For example, reflections by the clinician may have helped partners to see each other in a new light, or the treatment room may have created a safe space for couples to have mastery experiences, where one person’s disclosure of previously privately held emotional content was reinforced by their partner, promoting feelings of acceptance and intimate safety. In a study assessing the impact of homework completion on treatment gains, [AUTHOR, in press] found that completing recommendations assigned in the MC contributed to couples’ short term but not long term gains, meaning that even couples that completed substantially less homework eventually achieved gains comparable to those who completed more homework. A second possibility is that activation alone is not particularly helpful for couples. One study found that the average couple that attended psychotherapy had already been highly distressed for six years (Notarius & Buongiorno, 1992, as cited in Gottman, 2002). Intuitively, couples may be able to resolve most issues on their own, but those that are left unresolved may be particularly unresponsive to a couple’s repertoire. Thus, even if couples are highly activated towards changing, activation without expert guidance may be ineffectual.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The dose of mediator variables was not randomized, but rather was driven by each couple’s unique response to treatment, opening the possibility that an unobserved variable drove changes in both the mediators and relationship satisfaction. We explored this possibility through our use of cross lags. Because relationship satisfaction did not produce subsequent changes in the mediators, the probability that an unobserved confound accounted for our findings appears lower. In the contemporaneous analyses, we could not discern causal direction. In the longitudinal analyses, the mediators were entered pairwise rather than simultaneously, so it was not possible to partial out the independent effects of each mediator. Furthermore, our use of self-report measures to assess mediators presented two issues. First, these measures were constructed in-house for the present study, so formal studies verifying construct validity have not been published. Second, self-report questionnaires introduced the “glop problem” (Gottman, 2002) of high correlations amongst variables of interest. In the future, gathering observational data would be helpful to obtain ratings of acceptance and intimate safety more disconnected from a couple’s global rating of relationship quality.

Although this study adds useful data to the important ingredients for a healthy relationship, our sample is relatively homogeneous and our timeframe relatively short. The variables affecting relationship satisfaction may differ across cultural groups (Lucas et al., 2008), and there may also be important differences across the lifespan. The different “clocks” affecting development have been written about for some time (see Schaie, 1965), and while the clock in the present study starts at couples’ baseline measures, it may also be important to examine maturational clocks, like age or length of relationship, and cohort clocks, like birth year, which can influence individuals’ values and the processes most related to their relationship change.

Conclusions and future directions

The present findings, which provide evidence for the mediating role of acceptance and intimate safety in sustaining marital satisfaction, would be complemented by an understanding of the treatment mechanisms responsible for the initial change in the mediators. The most fruitful place to look may be in the interaction between the clinician and couple in-session. Linking specific therapeutic mechanisms to changes in the mediators identified here would help flesh out the full causal chain of change in this intervention.

More generally, relationship interventions draw from a broad range of theoretic frameworks, but very little work has examined competing theories of change from a theory outside of that in which an intervention was developed. A notable exception to this is a recent study by Benson, Sevier and Christensen (2013), examining the role of attachment in a behaviorally based couple therapy. Work of this nature is critical for achieving a dialog that leverages different theoretic frameworks towards an empirically coherent body of knowledge.

Couples research can be particularly challenging because so many variables and processes change in tandem. Perhaps as a result of this, researchers draw from a wide range of theoretic frameworks and interventions target many different processes. Identifying those variables with a time-lagged, within-person relationship can help determine the most useful targets, a task that is critical for improving models of relationship health and developing more effective interventions. The present study adds to the literature in several regards. It utilizes an innovative statistical methodology to flexibly examine the short and long-term impacts of mediators in a brief couples intervention, providing a dynamic model of mediation. Critically, it identifies intimate safety and acceptance as variables whose early changes lead to subsequent changes in relationship satisfaction, suggesting they may be key processes for improving relationship quality, maintaining gains, and preventing distress.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baucom DH, Hahlweg K, Atkins DC, Engl J, Thurmaier F. Long-term prediction of marital quality following a relationship education program: being positive in a constructive way. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(3):448. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson LA, McGinn MM, Christensen A. Common principles of couple therapy. Behavior therapy. 2012;43(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson LA, Sevier M, Christensen A. The impact of Behavioral Couple Therapy on attachment in distressed couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2013;39(4):407–420. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Lavner JA. How can we improve preventive and educational interventions for intimate relationships? Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(1):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby DM, Holman TB, Taniguchi N. RELATE: Relationship Evaluation of the Individual, Family, Cultural, and Couple Contexts. Family Relations. 2001;50(4):308–316. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A. A unified protocol for couple therapy. In: Hahlweg K, Grawe-Gerber M, Baucom DH, editors. Enhancing couples: The shape of couple therapy to come. Gottingen, Germany: Hogrefe; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV. Acceptance in behavior therapy: Understanding the process of change. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24(2):213. doi: 10.1007/BF03392032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JC, Blair J, Meade AE. The Intimate Safety Questionnaire: measuring the private experience of intimacy. Worcester, Massachusetts: Department of Psychology, Clark University; 2010. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Scott R. Intimacy: A behavioral interpretation. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24:75–86. doi: 10.1007/BF03392020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV. The Marriage Checkup practitioner’s guide: Promoting lifelong relationship health. Washington D.C.: APA Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Eubanks Fleming CJ, Ippolito Morrill M, Hawrilenko M, Sollenberger JW, Harp AG, Wachs K. The Marriage Checkup: A randomized controlled trial of annual relationship health checkups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(4):592. doi: 10.1037/a0037097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Gee CB, Warren LZ. Emotional skillfulness in marriage: Intimacy as a mediator of the relationship between emotional skillfulness and marital satisfaction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(2):218–235. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova JV, Scott RL, Dorian M, Mirgain S, Yaeger D, Groot A. The Marriage Checkup: An indicated preventive intervention for treatment-avoidant couples at risk for marital deterioration. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(4):301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Thum YM, Sevier M, Atkins DC, Christensen A. Improving relationships: mechanisms of change in couple therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):624. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. The mathematics of marriage: Dynamic nonlinear models. MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guerney B, Jr, Maxson P. Marital and family enrichment research: A decade review and look ahead. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990:1127–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Moore EM, Wilson KL, Dyer C, Farrugia C. Couple commitment and relationship enhancement: A guidebook for life partners. Brisbane: Australian Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Snyder DK. Universal Processes and Common Factors in Couple Therapy and Relationship Education. In: Halford W.Kim, Snyder Douglas K., editors. Behavior Therapy. 1. Vol. 43. 2012. pp. 1–12. Guest Editors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Blanchard VL, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(5):723. doi: 10.1037/a0012584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherington L, Friedlander ML, Greenberg L. Change process research in couple and family therapy: methodological challenges and opportunities. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(1):18. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito Morrill M, Cordova JV. Building intimacy bridges: from the Marriage Checkup to Integrative Behavioral Couple Therapy. In: Gurman AS, editor. Clinical casebook of couple therapy. Guilford Press; 2010. (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Christensen A. Integrative couple therapy: Promoting acceptance and change. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Progression of therapy research and clinical application of treatment require better understanding of the change process. Clinical Psychology: science and practice. 2001;8(2):143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of. Clinical. Psychology. 2007;3:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebow J. What does the research tell us about couple and family therapies? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;56(8):1083–1094. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200008)56:8<1083::AID-JCLP7>3.0.CO;2-L. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200008)56:8<1083::AID-JCLP7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas T, Parkhill MR, Wendorf CA, Imamoglu EO, Weisfeld CC, Weisfeld GE, Shen J. Cultural and Evolutionary Components of Marital Satisfaction: A Multidimensional Assessment of Measurement Invariance. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2008;39(1):109–123. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Renick MJ, Floyd FJ, Stanley SM, Clements M. Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: a 4-and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(1):70. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnaughy EA, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. Stages of change in psychotherapy: A follow-up report. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1989;26(4):494. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. When positive processes hurt relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19(3):167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Fournier D, Druckman JM. Life Innovations. Minneapolis, MN: 1996. Prepare. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti R, Wang SW, Saxbe D. Bringing it all back home: how outside stressors shape families' everyday lives. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(2):106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, Cobb RJ, Lawrence E, Johnson MD, Bradbury TN. Is skills training necessary for the primary prevention of marital distress and dissolution? A 3-year experimental study of three interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(6):949. doi: 10.1037/a0034209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin. 1965;64(2):92. doi: 10.1037/h0022371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Baucom DH, Burnett CK, Allen ES, Ragland L. Altering the course of marriage: the effect of PREP communication skills acquisition on couples' risk of becoming maritally distressed. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(1):41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK. Marital satisfaction inventory, revised (MSI-R) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK, Castellani AM, Whisman MA. Current status and future directions in couple therapy. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:317–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK, Schneider WJ. Affective reconstruction: A pluralistic, developmental approach. In: Gurman AS, Jacobson NS, editors. Clinical handbook of couple therapy. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 151–179. (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM. Making A Case for Premarital Education. Family Relations. 2001;50(3):272–280. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and The Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Markman HJ. Where's the action? Understanding what works and why in relationship education. Behavior therapy. 2012;43(1):99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.