Abstract

Developing programs to support low-income married couples requires an accurate understanding of the challenges they face. To address this question, we assessed the salience and severity of relationship problems by asking 862 Black, White, and Latino newlywed spouses (N=431 couples) living in low-income neighborhoods to (a) free list their three biggest sources of disagreement in the marriage, and (b) rate the severity of the problems appearing on a standard relationship problem inventory. Comparing the two sources of information revealed that, although relational problems (e.g., communication and moods) were rated as severe on the inventory, challenges external to the relationship (e.g., children) were more salient in the free listing task. The pattern of results is robust across couples of varying race/ethnicity, parental status, and income levels. We conclude that efforts to strengthen marriages among low-income couples may be more effective if they address not only relational problems, but also couples’ external stresses by providing assistance with childcare, finances, or job training.

Keywords: Conflict, Family Policy, Low-Income Families, Qualitative Research, Welfare Reform

Although maintaining a fulfilling marriage is challenging in all segments of society, it appears to be disproportionately challenging within low-income communities, where rates of divorce are nearly twice as high as in more affluent communities (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Raley & Bumpass, 2003). Recognizing the heightened vulnerability of low-income couples, and the severely negative consequences of divorce for low-income spouses and their children (e.g., poverty, mortality, lower education; see McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994; Rogers, 1995; Smock, Manning, & Gupta, 1999), the federal government has allocated hundreds of millions of dollars over the past 15 years toward the Healthy Marriage Initiative (HMI), a collection of policies and programs explicitly designed to strengthen marriages among low-income populations through education and relationship-skills training (Administration for Children and Families, 2012).

Evaluations of the HMI studies have recently concluded and the results have not been promising. The Building Strong Families (BSF) study, which used a sample of 5,102 couples to test skills-based relationship education programs for low-income unmarried expectant parents, had no effects on relationship satisfaction, relationship stability, or co-parenting when examined 36 months post-treatment (Wood, McConnell, Moore, Clarkwest, & Hsueh, 2012). A similar program aimed at low-income married parents (Supporting Healthy Marriages; SHM) used a sample of 6,298 couples to test the effectiveness of skills-based relationship education and found slightly better results; the intervention had a small but significant effect on relationship satisfaction at 30 months post-treatment, but it did not make couples more likely to stay married and did not improve parenting or co-parenting (Lundquist et al., 2014).

Why did these HMI programs have so little success at improving relationship outcomes, despite spending millions of dollars on interventions? One possibility is that eligible couples did not perceive a match between the program’s goals and their own needs and therefore did not participate fully or did not have their specific problems addressed when they did participate. Indeed, 45% of couples assigned to the treatment group in BSF never attended a group relationship education session (Wood, Moore, Clarkwest, & Killewald, 2014). Moreover, a meta-analytic evaluation of relationship education programs similarly suggested that these programs may be ineffective in low-income populations because “the curricula are less relevant to the daily challenges they face” (Hawkins & Erickson, 2015, p. 64). Previous research has demonstrated that couples seek help with their relationships based on how well the help matches their own perceptions of their relationship problems (Doss, Simpson, & Christensen, 2004). Moreover, to the extent that the type of help provided matches their needs and expectations, couples show greater persistence in continued help-seeking (Allgood & Crane, 1991) and better relationship outcomes (Crane, Griffin, & Hill, 1986). If there was indeed a gap between HMI programs and the needs of couples in the target population, this might be attributable to the fact that most research on the determinants of relationship functioning has been conducted on middle-class samples (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), whereas basic research with low-income couples is sparse by comparison (Fein & Ooms, 2006). Developing policies that are responsive to the needs of, and attractive to, low-income couples requires, at minimum, descriptive data on the challenges those couples perceive in their own relationships. The current study seeks to address this question by assessing the salience and severity of relationship problems among 431 Black, White, and Latino newlywed couples living in low-income neighborhoods.

What marital problems are low-income couples likely to face?

When asked to rate the challenges they face in their marriages, middle-class couples typically highlight difficulties with communication and intimacy. For example, when divorcing couples are asked to indicate the problems that led to their divorce, communication is the most cited problem, followed by general unhappiness and incompatibility (e.g., Bodenmann et al., 2007). Couple therapists asked about the problems most often reported by their clients (likely to be more affluent couples who can afford therapy) also cite spousal communication as the leading challenge (e.g., Geiss & O’Leary, 1981).

Yet there are strong reasons to expect that lower-income couples may experience a different range of relationship problems than those faced by more affluent couples. Several theoretical perspectives converge to suggest that, in contexts where chronic stress is high, couples’ concerns about resources will take precedence over their concerns about emotional fulfilment. Maslow’s (1943) “hierarchy of needs” is the classic expression of this idea, predicting that before individuals can devote attention toward higher-order needs such as intimacy and emotional fulfillment, they must address basic needs, such as money, food, and housing. For low-income couples whose basic needs are not easily or predictably met, relationship problems related to income and employment may attract more attention than challenges related to maintaining or improving emotional connections. Elaborating on the premise that a family’s level of stable resources affects their interpretation of and coping with specific stressors, Hill’s Crisis Theory (1949) predicts that where resources are few (e.g., in low-income communities), stressors that may be minor annoyances in more affluent communities may be highly salient, and may therefore affect marriages in those communities disproportionately. Thus, although lower-income couples value having a healthy marriage as much as higher-income couples (Trail & Karney, 2012), the intrusion of external stressors into low-income couples’ lives may draw focus away from concerns about the relationship, such as communication and intimacy, and toward concerns about financial and physical security.

Given that the explicit goals of Healthy Marriage Initiative programs were to support couples in low-income communities, one might expect that these predictions had been examined and that the needs of low-income couples had been thoroughly documented. On the contrary, few studies have assessed perceptions of relationship challenges within low-income communities. Those studies confirm that low-income individuals do perceive a wider array of relationship challenges than more affluent individuals. For example, ratings of the severity of relationship-specific issues like communication, sex, and being a parent do not differ significantly by income, but low-income individuals do rate money, drinking or drug use, being faithful, and friends as more difficult problems for their relationships than do more affluent respondents (Trail & Karney, 2012). Two studies of divorced individuals found that their reasons for divorcing differed by socioeconomic status, such that lower-SES individuals were more likely to attribute their divorce to issues such as abuse, financial problems, employment problems, and criminal activities, whereas higher-SES individuals were more likely to attribute their divorce to personality clashes, incompatibility, and lack of communication (Amato & Previti, 2003; Kitson 1992). Qualitative research on low-income, cohabiting couples in the Fragile Families study reached a similar conclusion, revealing that the majority of these couples experienced tensions over issues of housing, economics, employment, childcare, household chores, and personal issues such as drug and alcohol use (Waller, 2008).

Together, these results suggest that relationships in lower-income communities may face a greater array of relationship problems than relationships in more affluent communities. However it remains unclear whether this is specifically true of the young married couples that the Healthy Marriage Initiative programs were designed to support (Administration for Children and Families, 2012). Perhaps because rates of marriage are lower and rates of unmarried parenthood are higher in low-income communities as compared to more affluent communities (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Pew Research Center, 2010), most research on perceptions of marriage in low-income communities has gathered data from unmarried couples, individuals in established relationships, or single parents (e.g, the Welfare, Children, and Families study; Fomby, Estacion, & Moffitt, 2003; the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study; Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001). Much of this work has described parenting and child outcomes (e.g., McLanahan, 2009) or obstacles to marriage and aspirations for marriage (e.g., Edin & Kefalas, 2005). Yet, despite the fact that current policies aim directly at promoting and improving marital relationships, the challenges faced by young couples in the early stages of marriage have yet to be studied within the low-income communities being targeted.

Do different groups of low-income couples experience different problems?

Although federal policies have targeted low-income communities containing wide diversity, there has been no attempt to date to identify whether the challenges reported by low-income couples differ across various demographic subgroups. Yet the same perspectives that highlight differences in the relationship problems likely to be reported between low-income and more affluent couples also predict differences within lower-income communities. Minority stress theory, for example, highlights the fact that members of stigmatized racial groups face chronically high levels of stress through repeated exposure to prejudice and discrimination (Meyer, 2003). To the extent that racial and ethnic minority couples are experiencing additional stress, their psychological and emotional resources may be even more limited compared to those of White couples in similarly low-income communities. Thus, relative to White couples, Latino and Black couples may be especially likely to identify external problems as more salient within their marriages as compared to relational problems.

The same reasoning suggests that other sub-populations within lower-income communities facing particularly high levels of stress may similarly focus their attention toward relationship problems stemming from concrete stressors rather than relationship-specific stressors like communication. Two of these subgroups are couples with children and couples who are especially poor. Just as minority couples experience additional stress through experiences of discrimination, so too do couples experience additional stress in raising children (Cowan & Cowan, 1992; 2014) and in living in poverty (Heymann, 2000). Therefore, relative to non-parents or more financially secure couples within the same communities, parents and poorer couples may view concrete stressors (e.g., childcare, work, or financial pressures) as more salient relationship problems than emotional issues. Investigating these possible differences is important, as policies and programs implemented in low-income communities will be most effective when they are informed by data on the unique challenges perceived by members of the communities they target.

Do standard assessments of problem severity identify the problems that are most salient to low-income couples?

To study the needs and challenges of low-income couples, prior research has typically borrowed tools from similar research on other populations. For example, researchers have used ratings of standard lists of relationship problems to assess how couples evaluate the severity of each potential problem on the list. Such lists can be useful tools, but only when the content of the list addresses the domain of salient problems that the population being studied is actually facing. Unfortunately, the relevance of most current lists of relationship problems to the lives of low-income couples has not been established. For example, one influential list (Geiss & O’Leary, 1981) was developed through interviews with couples therapists, who presumably serve a mostly affluent, well-educated population. Research that relies exclusively on preexisting lists of challenges such as this therefore may overlook issues that are unique to low-income couples.

An alternative approach is a free-listing task that allows participants to nominate the problems that are the most salient or pressing for them, without imposing a predetermined set of responses (Thompson & Juan, 2006). This technique can be as reliable and valid as fixed-response techniques (Krosnick, 1999) and is capable of uncovering issues that are important to respondents that may not be included on fixed-response inventories (Schuman, Ludwig, & Krosnick, 1986). Research in other fields suggests that responses to open-ended questions are as good as or better than responses to survey questions at predicting a number of important outcomes, including candidate approval ratings and voting behavior (Bratton, 1994), attitude expression, financial contributions, and group meeting attendance (Miller, Krosnick & Fabrigar, 2014). Moreover, responses to a fixed- vs. open-ended question may reflect different information. Indeed, research on political attitudes reveals that the issues that voters recognize as important in fixed-response questions are not always the ones that they spontaneously report when asked to recall issues that are important to them using open-ended prompts (e.g., RePass, 1971; Schuman & Scott, 1987). These differences suggest that to understand the challenges that low-income couples perceive as relevant to their own relationships, free-listing techniques are an important complement to standard survey questions. To date, we are aware of no research that has collected and compared responses to both types of questions within a single study.

The current study

In an effort to align future efforts to strengthen marriage in low-income communities with the needs of couples in those communities, the current study aims to 1) describe the challenges that low-income couples perceive at the beginning of their marriages, 2) compare and contrast the problems couples report across two different methodologies; a problem inventory and a free-listing task, and 3) determine whether the most salient and severe problems differ across racial/ethnic groups, between parents and non-parents, and at different levels of income. To address these goals, we asked newlywed couples living in low-income communities to free-list the biggest sources of disagreement in their marriages and then, on a standard list of relationship problems, to rate the severity of potential areas of disagreement. Newlyweds are an appropriate sample in which to address these goals, for several reasons. First, even in more affluent communities, the first years of marriage are a period of elevated risk for declines in marital satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2005), suggesting that the challenges couples face during this period are particularly important for the future of the relationship. Second, younger couples (i.e., of childbearing age) are the explicit targets of federal policies and programs (Ooms, Bouchet, & Parke, 2004). Third, restricting the sample to couples at a similar early stage of development ensures that the sample does not exclude the most vulnerable couples, who might dissolve and therefore be absent from populations of more established relationships (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Drawing upon existing theories of family stress, we predicted that low-income couples would be significantly more likely to consider their external stressors as salient than relationship-specific stressors, such as communication.

METHOD

Sampling

Our sampling procedure was designed to yield a sample of first-married newlywed couples living in low-income communities. To accomplish this, participants were recruited from Los Angeles County, a region with a large and diverse low-income population. Recently married couples were identified through names and addresses provided on marriage license applications in 2009. These addresses were matched with census data to identify applicants who resided in low-income communities, defined as census block groups wherein the median household income was no more than 200% of the 1999 federal poverty level for a four person family (a similar definition has been used in analyses of the National Survey of Family Growth; e.g., Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Next, names on the licenses were weighted using data from a recently developed Bayesian Census Surname Combination (BCSC; Elliott et al., 2013), which integrates census and surname information to produce a multinomial probability of membership in each of five racial/ethnic categories (Latino, Black, Asian, White, or other) based on residential address and surname. Couples were selected from the total population of recently married couples using probabilities proportionate to the ratio of target prevalence to the population prevalence, weighted by the couple’s average estimated probability of being Latino, Black, or White. These couples were contacted by phone and screened to ensure that they had actually married, that neither partner had been previously married, and that both spouses identified either as Latino, Black, or White. A total of 3,793 couples were contacted through the addresses they listed on their marriage licenses, and offered the opportunity to participate in a longitudinal study of newlywed development. Of the 3,793 couples contacted, 2,049 could not be reached and 1,522 responded to the mailing and agreed to be screened for eligibility. Of those, 824 couples were screened as eligible, and 658 of them agreed to participate in the study, with 431 couples actually completing the study.

Participants

Of the 431 recently married, heterosexual couples that participated in the study, 76% self-identified as Latino, 12% as Black, and 12% as White. The proportions of each group in the sample roughly matched the proportion of each group living in low-income neighborhoods in Los Angeles (i.e., 60.5% Latino, 12.9% Black, and 14.7% White; U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). Of the Latino sample, the majority of respondents were U.S. citizens (70.3% of wives, 63.9% of husbands), and most were maternal first-generation Americans (92.1% of wives’ mothers and 92.7% of husbands’ mothers were born outside of the US). The vast majority of White and Black respondents were born in the United States (90.0% of White wives, and 94.0% of White husbands; 96.1% of Black wives, and 96.1% of Black husbands). The mean length of marriage across couples was 4.9 months (SD = 2.5) at the time of data collection. Wives’ mean age was 26.2 years (SD = 5.0), and husbands’ mean age was 27.9 years (SD = 5.8). White wives were significantly older than Black and Latino wives (Ms = 29.6, 26.9, and 25.6 years, respectively), and White husbands were significantly older than Black and Latino husbands (Ms = 31.3, 28.7, and 27.3, respectively).

Wives had a mean income of $25,944 (SD = $24,121) and husbands had a mean income of $33,379 (SD = $26,740). As expected, White wives and husbands had significantly higher incomes (Ms = $47,082 and $62,020, respectively) than did Black wives and husbands (Ms = $28,869 and $29,241, respectively) or Latino wives and husbands (Ms = $22,027 and $29,410, respectively). Overall, 166 (38.5%) couples had at least one biological child in the household (6.0% of White couples, 52.9% of Black couples, and 41.2% of Latino couples), with 66 couples (15%) having more than one child.

Procedure

Couples were visited in their homes by two trained interviewers. Study procedures were fully explained and informed consent was obtained from each spouse. Husbands and wives were then taken to separate areas (either inside or outside the house) and interviewed one-on-one. All interviewers were fluent Spanish and English speakers, and interviews with Latino respondents were conducted in Spanish (19%), English (63%), or a mix of Spanish and English (18%). The interview encompassed a wide range of topics, including detailed demographics, relationship experiences, and physical health. Respondents gave their answers to questions verbally, and interviewers either recorded their responses numerically for fixed-response items or transcribed their responses for open-ended and free-response items. Upon completion of the home visit, couples were debriefed and compensated in cash for their time. Data for the current analysis makes use of responses collected at the baseline assessment only.

Measures

Problem Salience

We assessed respondents’ free-response description of the problems in their relationship with their spouse by asking: “All couples experience some difficulties or differences of opinion in their marriage, even if they are only very minor ones. What are the three biggest sources of disagreement between you and [spouse’s name]?” If respondents had difficulty coming up with responses, the interviewer probed them by asking: “If you had to pick one thing that you don’t see eye to eye on, what would it be?”

Problem Severity Scale

Participants then completed a version of the Relationship Problems Inventory (RPI; Geiss & O’Leary, 1981). This scale consisted of 22 items, and respondents were asked to “rate how much [each] issue is a source of difficulty or disagreement for you and your spouse, on a scale from 0 to 10.” Respondents were told that items rated toward the low end of the scale (0–2) should be “issues that rarely if ever raise conflict or disagreement,” and items rated toward the high end of the scale (8–10) should be “issues that raise frequent or intense conflict or disagreements” in the relationship.

Coding Procedures and Reliability Measures

We developed coding categories for the transcribed responses to the free-response items using standard procedures for coding open-ended survey questions (Ryan & Bernard, 2003). The goal of this procedure was to develop a comprehensive set of categories that would accurately describe responses to each item without being overly general or overly specific in their scope. In the first step of this process, a sample of the responses to a free-response item was given to four trained coders. Each coder read through the sample responses and independently developed a set of categories to capture the content of the responses to the question. The four coders then met with the researchers and discussed the categories that they had generated. This discussion yielded a set of categories that were agreed upon by all coders. In the next step, two of the coders independently assigned each response to one of the topic categories. At least one of the two coders was fluent in Spanish per pair. The coders then met with the researchers and discussed any uncertainties about the codes in an iterative process, with coders sorting and categorizing all responses to one free-response question before moving on to the next question. Inter-coder reliability was calculated two ways: A simple percent agreement score and a kappa score. Reliability was adequate, with 85.8% agreement between coders and a kappa of .85. Discrepancies between codes assigned to a response were resolved by randomly choosing one of the two codes.

Analysis Strategy

The primary goal of this study was to explore the spontaneous responses that couples gave to open-ended questions about their relationships and to compare those responses to a standardized closed-ended measure of problem severity, measured using the RPI. Thus, we sought to quantify what immediately came to respondents’ minds when asked about different aspects of their spouse and their experiences in the relationship. In order to accomplish this, we subjected the sample’s coded responses to a salience analysis using Visual Anthropac 1.5 (Borgatti, 2003) software. Salience analyses are used to uncover the words or issues that are significant to people within a specific domain (e.g., relationship problems; Thompson & Juan, 2006). This technique uncovers the scope of issues within a particular domain and how salient each issue is for that group of people. Previous research has shown that the most salient items will be named by most people in the sample and those items will appear earlier in individual’s lists (Bousfield & Barclay, 1950; Friendly, 1977). Here we calculate salience using Sutrop’s salience index S = F/(N mP), where F is the frequency that each item was mentioned across participants, N the number of subjects (in this case 431 each for husband and wife analyses) and mP is the mean position, or average ranking of each item (i.e., whether it was mentioned first, second, or third; Sutrop, 2001). Using this index, an issue that was mentioned by only a few participants, but usually mentioned first when it was mentioned, would receive a higher salience score than would an issue that was infrequently mentioned and was listed second or third on average when it appeared. These aggregated sample salience scores were then compared to the mean ratings of problem severity for each item in the RPI.

Follow up analyses were conducted to determine whether there were any individual influences on salience and severity. Because salience analyses result in only group-level statistics, we analyzed individual influences on responses through logistic regression using SAS 9.3. For each of the top 10 salience categories across the sample, we created a binary variable indicating whether or not the respondent included the category in their list of salient problems. This analysis allowed us to estimate the relationship between individual characteristics (i.e., household income, parental status and race/ethnicity) and problem salience. To evaluate individual influences on problem severity, we conducted regression using SAS 9.3 predicting an individual’s severity score from 0 to 10 (for each of the top 10 salient issues) from the same individual characteristics. All analyses were conducted separately for husbands and wives and used Bonferroni-corrected alpha values (p = .05/40 = .001 for analyses of race, and p = .05/20 = .0025 for analyses of income and parental status) to ensure we made conservative estimates of effects across the large number of moderation tests conducted.

RESULTS

Comparing Open-Ended Responses to RPI Items

To identify whether standard marital problem inventories sample the content domains most salient to couples in low-income communities, we compared the marital problems featured on the RPI to the categories that emerged from coding spouses’ free listing of their marital problems. The majority of items from the version of the RPI used in the current study mapped directly onto categories of problems that emerged from spouses’ free-listing of their top marital problems. However, three categories that emerged as salient problems for spouses did not match items included on the RPI. The first of these categories was support, i.e., respondents asking for too much or not getting enough support from their spouse. Examples included: “I’m always exhausted and he wants me to attend to him” and “He doesn’t defend or stand up for me as he should.” The second was health, i.e., tensions over issues related to physical well-being. Examples included: “My weight—I weigh too much,” and “I always have conflicts with her about her not eating well.” The third was living situation, i.e., housing issues such as “Household - she wants her own house (not my parents house);” and “Living situation- we don’t have the resources.” Together, these three categories may be issues that are especially salient to low-income populations, but less so to the moderate or high-income couples who originally generated the topics on the RPI and related problem inventories. For all other categories of marital problems, the RPI inventory included the issues that emerged as salient to newlyweds in low-income communities.

Comparing Severity Ratings and Salience Scores

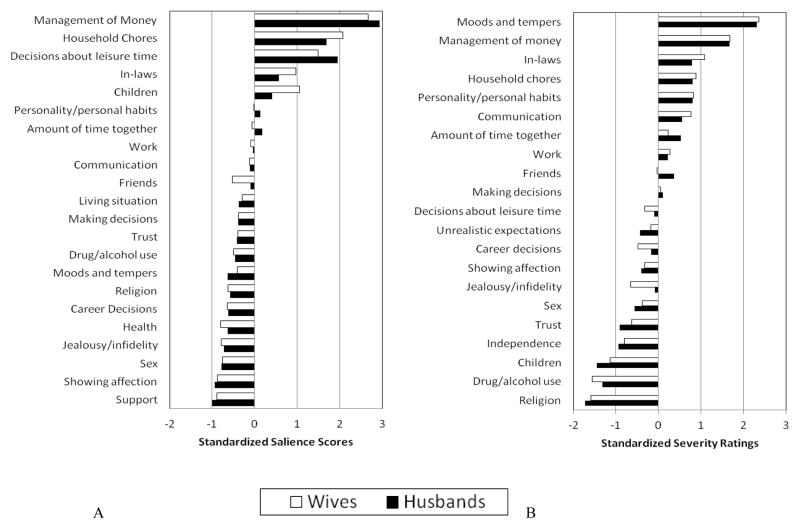

Although a standard problem inventory like the RPI appears to address most of the domains of salient marital problems for couples in low-income communities adequately, it does not necessarily follow that problem severity as assessed by inventories provides the same picture as problem salience as assessed by free listing tasks. To evaluate this question, we first conducted Pearson correlations between the two methods, separately for husbands and for wives, to determine whether the standardized salience scores for each marital problem category derived from the free listing task (see Figure 1A) were correlated with the standardized severity ratings of each problem on the RPI (see Figure 1B). We then compared the problems reported by husbands and wives to determine the level of agreement across spouses. Finally, we compared and contrasted the rankings of specific problems across these two methodologies.

Figure 1.

Standardized salience scores (A) and RPI ratings (B) for husbands and wives. In Figure 1A, higher numbers reflect greater salience, and in Figure 1B, higher numbers reflect greater severity ratings.

The Pearson correlations reveal small non-significant correlations between the standardized problem salience and standardized problem severity scores for both husbands r(19) = .38, p = .10, and for wives r(19) = .41, p = .08. In studies of social psychological phenomena, correlations between .3 and .5 are considered medium-sized effects (Cohen, 1992). However, these are guidelines provided for evaluating the associations between distinct psychological and behavioral phenomena. Given that the free-listing problem task and the problem inventory essentially ask the same question in two different ways, we should expect significantly higher correlations comparable to those found in reliability analyses (i.e., those higher than .7 or .8). In fact, the shared variance across these measures is only r2 = 14% for husbands and r2 = 17% for wives, both of which are not significantly different from zero. This suggests that the free-listing task and the problem inventory are in fact distinct measures of couples’ problems, with each revealing unique information about the experiences of low-income couples.

Comparing across husbands’ and wives’ reports indicates that there is little agreement between partners in their own problems, but high agreement in the problems faced by low-income couples generally. Husbands’ and wives’ severity rankings had small correlations ranging from r(431) = .10 – .43, p < .01 across the 28 problems in the RPI. With the free-listing task, there is a similar pattern of discordance. Only 2% of couples in the sample agreed on their top 3 relationship problems, 31% agreed on at least 2 out of 3, and 81% agreed on at least 1 of 3. However, correlations of the salience and severity of problems between husbands and wives reports’ across the whole sample reveal significantly high correspondence in which problems were reported as salient r(19) = .97, p <.001, and those rated as severe r(19) = .97, p <.001. Thus, although spouses frequently disagree about the problems they face within their own marriage, they do agree about the central issues across all marriages.

Comparing the two panels of Figure 1 reveals that, for most problems and problem categories, marital problems rated as above average in severity were also marital problems that were above average in salience for both husbands and wives. Among these newlywed couples living in low-income communities, the following three marital problems were above average in salience and severity: management of money (e.g., “Paying bills” or “Not having enough money for the baby and to go out”), household chores (e.g., “She feels like I don’t do enough household chores, and she doesn’t like the way I do them”), and in-laws (e.g., “She never wants to see my family” or “Helping the extended family too much”).

Yet despite some correspondence between the two kinds of ratings, the salience and severity ratings did not correspond for four problems. Two marital problems emerged as above average in severity for this sample, but below average in salience. Consistent with our predictions, couples in low-income communities rated moods and tempers (e.g., “I get mad too quick”; “I tell her she is too moody”; “She gets frustrated too easily”) and communication (e.g., “I don’t like the way he talks to me sometimes”) as above average in severity when rating the problem on the RPI, yet these same issues emerged as below average in salience on the free listing task. The difference in ratings of moods and tempers was especially striking: on average husbands and wives rated this problem as more severe than any other problem on the list, yet when asked to generate their biggest problems, it did not appear among the top ten most-frequently mentioned issues. In other words, although these relational challenges are recognized as serious problems when spouses are reminded of them, they are not problems that couples in low-income communities spontaneously retrieve when thinking about the problems in their marriages.

In contrast, two problems that were above average in salience within this sample were rated as below average in severity. Again consistent with our predictions, couples in low-income communities rated children (e.g., “We disagree on how many kids we want to have”; “We disagree on how to reprimand the kids”) and decisions about leisure time (e.g., “He spends too much time online”) as above average in salience, even though the same issues were rated as below average in problem severity. Here, the difference in the ranking of children as a relationship problem was especially striking: when presented on a list, children was rated as one of the least severe problems that couples disagree about, but when asked about their biggest disagreements, children was one of the most frequently mentioned topics. Together, this pattern suggests that the marital problems that come to mind most readily for couples in low-income communities are not always the problems that they experience as most severe.

Moderation in Problem Salience and Severity

The couples in this sample varied widely in race/ethnicity, parental status, and income. We hypothesized that each of these variables might moderate the sorts of problems that couples experienced as most severe and most salient. To evaluate this possibility, we conducted two sets of analyses to look for moderation by key variables that signal stress or disadvantage. Results of these tests revealed that the ranking of problem severity and salience was generally robust throughout the sample, with only a few exceptions.

Race/Ethnicity

Using White couples as a reference group, Black and Latino couples did not significantly differ from White couples in their problems in all 40 of the 40 comparisons made for problem salience and in 38 of the 40 comparisons for problem severity. However, Hispanic and Black husbands were less likely than White husbands to rate problems with work as severe (for Hispanic husbands: b = −1.73, SE = 0.46, p < .001, for Black husbands: b = −2.13, SE = 0.59, p < .001) after controlling for parental status and income.

Parental Status

Controlling for race/ethnicity and income, analyses of moderation by parental status failed to reach significance in 18 of the 20 comparisons for problem salience and in 18 of the 20 comparisons for problem severity. Not surprisingly, parents in the sample listed problems with children as more salient (for husbands: OR = 6.74, p < .001; for wives: OR = 7.82, p < .001) and as more severe (for husbands: b = 0.73, SE = 0.23, p < .001; for wives: b = 0.96, SE = 0.25, p < .001) than non-parents.

Income

Controlling for race/ethnicity and parental status, analyses of moderation by household income failed to reach significance in 19 of the 20 comparisons for problem salience and in all 20 of the 20 comparisons for problem severity. Wives with lower household income were less likely than their more affluent peers to rate problems with household chores as salient (OR = 0.65, p < .001).

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade, the federal government has allocated hundreds of millions of dollars towards programs designed to promote and strengthen marriage in low-income communities. Despite this considerable investment, recent evaluations reveal that the existing programs have had a negligible impact (e.g., Wood et al., 2014). Understanding why these programs failed requires, at minimum, basic research documenting the specific challenges that low-income couples face in maintaining successful relationships, but to date such research has been sparse. To address this gap in the literature and to inform the next generation of interventions to support low-income couples, the current study used open-ended and fixed-response measures to examine the salience and severity of relationship problems in 431 Black, White and Latino newlywed couples living in low-income neighborhoods.

When responses to the two approaches to assessing low-income spouses’ perceptions of their relationship problems were standardized and presented side-by-side, the results revealed considerable overlap in content within the lists broadly, yet the rankings of different problems were uncorrelated across the two lists. Three problems emerged as above average on both lists: management of money, household chores, and in-laws. Consistent with predictions, when spouses living in low-income communities were asked to describe the biggest sources of disagreement in their relationship, the sources of those disagreements seem to reflect specific aspects of life outside of their relationship. This generalization held true for husbands and for wives, and regardless of whether we examined problem severity or problem salience.

Some relationship problems were ranked differently depending on how problems were assessed, and these differences highlight the value of combining both open-ended and fixed-response questions in a single study. For example, an exclusive reliance on severity ratings would suggest that moods and communication were among the most important and challenging problems that low-income couples face, and would support the relational focus of current interventions aimed at this population. Yet these were not the problems that most low-income couples spontaneously generated when asked to consider the problems in their marriages. The issue of moods and tempers, in particular, was far below average in salience when assessed in the open-ended task, despite being rated the most severe problem when it appeared on the fixed-response list. One explanation for the difference may be that free-listing tasks and problem-rating tasks invoke cognitive processes at different levels of abstraction (Schuman et al., 1986). Several of the problems listed on the RPI are quite broad (e.g., moods and tempers, communication, personality). These categories ask spouses to retrieve their own examples from memory, and the breadth of the category means that most spouses will be able to find relevant examples when asked to do so. Thus, a problem like moods and tempers may be rated as more severe than other problems on the list because many common negative experiences within a marriage may be seen as an example of that problem, whereas the experiences relevant to a concrete problem, like drug use for example, are more infrequent. In contrast, when asked to generate their own problems, spouses appear to have gravitated toward more concrete issues.

What were those more concrete issues raised in the open-ended task? Many of the most salient marital problems generated by spouses overlapped with the problems rated as most severe on the RPI, suggesting that, in general, standard lists of marital problems do address the relevant domains of marital problems for a wide range of couples. But several problems that emerged as salient on the free-listing task were not represented or rated highly on the marital problem inventory used here, and these issues tended to stem from stress outside of the relationship. For example, coders recognized within the free-listing responses three issues that do not appear on standard lists of relationship problems: support, health, and living situation. In addition, issues regarding children and decisions about leisure time emerged as above average in salience, even though both issues were rated as below average in problem severity. Together these problems reflect the challenges that arise within the relationship when couples face challenges outside their relationship, like competing demands (e.g., children, health issues, or an unsatisfying living situation) or constraints on their time together. These issues, highlighted within responses to the free-listing task, are underemphasized or missed entirely by exclusive reliance on problem inventories. However when combined with the fixed-responses, these open-ended reports can yield a better understanding of the complex nature of couples’ relationship problems, a phenomenon other family researchers have also documented (see Clark, Huddleston-Casas, Churchill, Green, & Garrett, 2008 for a review).

We also predicted that this pattern of results might differ across subgroups facing varying levels of stress and greater demands on their relationships (e.g., minority vs. white couples, parents vs. non-parents, and especially poor couples vs. couples who were more secure financially). Analyses that examined how each of these dimensions moderated spouses’ perceptions of their marital problems did not support this view. Instead, the ratings and rankings of most marital problems were, for the most part, not significantly moderated by minority group status, parenthood, or household income. The results of these moderation analyses instead support the view that the problems low-income populations face tend to be robust across subsets of the population regardless of the additional stressors they may face individually.

Strengths and Limitations

A number of strengths in the methodology and design of this study enhance confidence in the results. First, our sampling strategy yielded a sample that was large and relatively homogeneous on age, length of marriage (i.e., newlyweds within nine months of marriage), and previous marital status (i.e., all spouses were in their first marriage). Thus, the results described here are unlikely to be confounded by unexamined sources of variance between couples. Second, we obtained data from husbands and wives, allowing us to ensure that the basic pattern of results described here was not idiosyncratic to one spouse. Third, this study is the first of which we are aware to obtain spouses’ perceptions of their marital problems through open-ended and forced choice assessments, allowing us to evaluate the similarities and differences between these approaches directly.

Despite these strengths, several limitations of the study also suggest caution in drawing broad conclusions about the problems faced by couples in low-income communities. First, all the data described here were obtained through self-reports. To the extent that couples struggle with significant problems of which they are unaware or which they are unwilling to report, those problems would not be represented in these data. Second, although the sampling strategy yielded a diverse, low-income sample, it was not designed to yield a nationally representative sample. The sample was drawn from an urban environment (Los Angeles County), and it is possible that low-income couples from rural environments or other regions of the country face different problems. Third, although these findings may generalize to the young, first-married newlyweds that we sampled, cohabiting unmarried couples, older couples, remarried couples, or couples of longer marital duration may experience different problems as more or less salient or severe. Finally, with regard to the free-listing task, we asked respondents to list their three biggest sources of disagreements in their marriages, but it is possible that a longer or more detailed free-listing assessment would have revealed additional issues.

Implications for Policy

Interventions aimed at low-income communities will be most effective to the extent that they address the problems perceived to be most salient to couples within those communities (Dion, 2005; Ooms et al., 2004). The results reported here suggest that the communication and conflict resolution problems identified in prior marital research on white, middle-class couples may not be the ones most relevant for the mostly minority, primarily lower-income couples targeted by federal policies. As other scholars have begun to argue (e.g., Hawkins & Erickson, 2015; Johnson, 2012), this mismatch may account for the disappointing results of recent, expensive national interventions (e.g., Wood et al., 2014). Relationship skills were the central focus of the interventions but not the most salient problems for couples within the population. When couples do not perceive that an offered intervention meets their needs, they are unlikely to make the effort to participate (Doss et al., 2004), and they may not benefit when they do (Crane et al., 1986).

Describing spouses’ perceptions of their marital problems within low-income communities suggests an alternative direction for future efforts to promote and strengthen low-income families. To the extent that lower-income couples are more likely to view their problems as stemming from sources outside the relationship, future interventions should consider ways of addressing those external demands directly, in addition to current efforts to improve couples’ marriages. Policies that promote the health and well-being of low-income couples (e.g., through offering childcare, healthcare, or job training) may benefit marriages indirectly but significantly (Karney & Bradbury, 2005; for an example of such a program, see Hardoy & Schøne, 2008). Some state programs are already taking this approach, building job training, financial assistance, and financial advice and training into their marriage promotion programs (Ooms, et al., 2004). The current research suggests that these multimodal interventions, to the extent that they meet a perceived need, may be more effective and may have greater program uptake and persistence than programs that do not offer this assistance.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this report was supported by Research Grants HD053825 and HD061366 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to Benjamin R. Karney. We gratefully acknowledge the crucial assistance of Kelly Campbell, Elizabeth Glanzer, Maya Harel, Amber Piatt and Davina Simantob for their assistance in coding.

Contributor Information

Grace L. Jackson, University of California, Los Angeles

Thomas E. Trail, RAND Corporation

David P. Kennedy, RAND Corporation

Hannah C. Williamson, University of California, Los Angeles

Thomas N. Bradbury, University of California, Los Angeles

Benjamin R. Karney, University of California, Los Angeles

References

- Administration for Children and Families. ACF Healthy Marriage Initiative. 2012 Retrieved May 3, 2012, from http://acf.gov/healthymarriage/

- Allgood SM, Crane DR. Predicting marital therapy dropouts. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1991;17(1):73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1991.tb00866.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Previti D. People’s reasons for divorcing: Gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:602–626. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03254507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LE, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Charvoz L, Bradbury TN, Bertoni A, Iafrate R, Giuliani C, Banse R, Behling J. The role of stress in divorce: A three-nation retrospective study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24(5):707–728. doi: 10.1177/0265407507081456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP. Visual anthropac 1.5. Lexington, KY: Analytic Technologies, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bousfield WA, Barclay WD. The relationship between order and frequency of occurrence of restricted associative responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1950;40:643–647. doi: 10.1037/h0059019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States Vital and Health Statistics. Vol. 23. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton KA. Retrospective voting and future expectations: The case of the budget deficit in the 1988 election. American Politics Research. 1994;22(3):277–296. doi: 10.1177/1532673X9402200302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VLP, Huddleston-Cases CA, Churchill SL, Green DON, Garrett AL. Mixed methods approaches in family science research. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(11):1543–1566. doi: 10.1177/0192513X08318251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman DL, Gilligan TD. Social support, stress, and self-efficacy: Effects on students’ satisfaction. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice. 2002;4(1):53–66. doi: 10.2190/BV7X-F87X-2MXL-2B3L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Controversies in Couple Relationship Education (CRE): Overlooked evidence and implications for research and policy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2014;20(4):361–383. doi: 10.1037/law0000025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crane DR, Griffin W, Hill RD. Influence of therapist skills on client perceptions of marriage and family therapy outcome: Implications for supervision. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1986;12(1):91–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1986.tb00642.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dion MR. Healthy marriage programs: Learning what works. The Future of Children. 2005;15(2):139–156. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Simpson LE, Christensen A. Why do couples seek marital therapy? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(6):608–614. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.35.6.608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MN, Becker K, Beckett MK, Hambarsoomian K, Pantoja P, Karney B. Using indirect estimates based on name and census tract to improve the efficiency of sampling matched ethnic couples from marriage license data. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2013;77(1):375–384. doi: 10.1093/poq/nft007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fein D, Ooms T. What Do We Know About Couples and Marriage in Disadvantaged Populations? Reflections from a Researcher and a Policy Analyst. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, Estacion A, Moffitt R. Welfare, families, and children: Characteristics of the three-city sample: wave 1 and wave 2. Johns Hopkins University; 2003. Retrieved from http://web.jhu.edu/threecitystudy/images/CharacteristicsReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Friendly ML. In search of the M-gram: The structure of organization in free recall. Cognitive Psychology. 1977;9:188–249. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(77)90008-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss SK, O’Leary KD. Therapist ratings of frequency and severity of marital problems: Implications for research. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1981;7(4):515–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1981.tb01407.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Erickson SE. Is couples and relationship education effective for lower income participants? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2015;29(1):59–68. doi: 10.1037/fam0000045.supp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann SJ. The widening gap: Why America’s working families are in jeopardy - and what can be done about it. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. Families under stress. New York: Harper & Row; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1982;116:123–140. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Moore D. Spouses as observers of the events in their relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49(2):269–277. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.49.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD. Healthy marriage initiatives: On the need for empiricism in policy implementation. American Psychologist. 2012;67(4):296–308. doi: 10.1037/a0027743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Cohan CL, Davila J, Lawrence E, Rogge RD, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Problem-solving skills and affective expressions as predictors of change in marital satisfaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):15–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.73.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118(1):3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Contextual influences on marriage: Implications for policy and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(5):171–174. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00358.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson GC. Portrait of divorce: Adjustment to marital breakdown. New York: Guilford; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick JA. Survey Research. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50(1):537–567. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist E, Hsueh J, Lowerstein AE, Faucetta K, Gubits D, Michalopoulos C, Knox V. A Family-Strengthening Program for Low-Income Families: Final Impacts from the Supporting Healthy Marriage Evaluation. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. OPRE Report 2014-09A. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370–96. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Fragile families and the reproduction of poverty. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;621:111–131. doi: 10.1177/0002716208324862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM, Krosnick JA, Fabrigar LR. The origins of policy issue salience: Personal and national importance impact on behavioral, cognitive, and emotional issue engagement. In: Krosnick JA, Chiang I-C, Stark T, editors. Explorations in Political Psychology. Psychology Press; New York, New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooms T, Bouchet S, Parke M. A state-by-state snapshot. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy; 2004. Beyond marriage licenses: Efforts in states to strengthen marriage and two-parent families. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The decline of marriage and rise of new families. Pew Research Center; 2010. Retrieved from http://pewsocialtrends.org/2010/11/18/the-decline-of-marriage-and-rise-of-new-families/ [Google Scholar]

- Raley K, Bumpass L. The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research. 2003;8:245–259. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2003.8.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman N, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan S. The Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23:303–326. doi: 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RePass DE. Issue salience and party choice. The American Political Science Review. 1971;65:389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG. Marriage, sex, and mortality. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1995;57:515–526. doi: 10.2307/353703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. doi: 10.1177/1525822X02239569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Ludwig J, Krosnick JA. The perceived threat of nuclear war, salience, and open questions. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1986;50(4):519–536. doi:10.1086/ [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Scott J. Problems in the use of survey questions to measure public opinion. Science. 1987;236:957–959. doi: 10.1126/science.236.4804.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Gupta S. The effect of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:794–812. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrop U. List task and a cognitive salience index. Field Methods. 2001;13(3):263–276. doi: 10.1177/1525822X0101300303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EC, Juan Z. Comparative cultural salience: Measures using free-listdata. Field Methods. 2006;18(4):398–412. doi: 10.1177/1525822x06293128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trail TE, Karney BR. What’s (not) wrong with low-income marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:413–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00977.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waller MR. How do disadvantaged parents view tensions in their relationships? Insights for relationship longevity among at-risk couples. Family Relations. 2008;57(2):128–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00489.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RG, McConnell S, Moore Q, Clarkwest A, Hsueh J. The effects of building strong families: A healthy marriage and relationship skills education program for unmarried parents. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2012;31(2):228–252. doi: 10.1002/pam.21608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RG, Moore Q, Clarkwest A, Killewald A. The long-term effects of Building Strong Families: A program for unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76(2):446–463. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]