Abstract

Here we report the case of a patient with familial dysautonomia (a genetic form of afferent baroreflex failure), who had severe hypertension (230/149 mmHg) induced by the stress of his mother taking his blood pressure. His hypertension subsided when he learnt to measure his blood pressure without his mother’s involvement. The case highlights how the reaction to maternal stress becomes amplified when catecholamine release is no longer under baroreflex control.

Keywords: Emotions, blood pressure, autonomic, stress, Jewish genetic disease, hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy

Background

Familial dysautonomia (FD, OMIM#: 223900), also known as Riley-Day syndrome, and hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type III, is a rare genetic disease that affects the development of sensory and autonomic neurons carrying afferent information to the brain. Affected patients lack incoming information from the arterial baroreceptors conveyed by the glossopharyngeal and vagal nerves, and catecholamine release is no longer under baroreflex control [3].

This genetic form of afferent baroreflex failure prevents the buffering of changes in arterial blood pressure (BP); so even mild emotional, cognitive or physical stress result in unrestrained catecholamine release and paroxysmal hypertension. These hypertensive surges occur sometimes several times a day alternating with orthostatic hypotension. Over time, this blood pressure instability produces end-organ damage [4].

Here we report the case of a young man with FD with daily episodes of systolic BP above 200 mmHg captured by his mother on home BP monitoring. His hypertension resolved when he learned to measure his BP alone and without his mother’s involvement. This case highlights how emotions can induce hypertensive surges in patients with disorders of afferent baroreflex control.

Report

The patient presented in infancy with recurrent pneumonias and failure to thrive. Genetic confirmation of the FD founder mutation was obtained. At the age of 5, he was treated with the stimulant methylphenidate and developed hypertension (BP supine 153/102 and standing 173/143 mmHg). Between age 8 and 13 years he was treated with 0.25 mg/day of fludrocortisone, which worsened his hypertension (BP supine 222/104 and standing 240/113 mmHg). Over the next 7 years, his renal function deteriorated.

By the age of 18, he had stage IIIB chronic kidney disease. At that time, his mother reported a home (seated) BP reading of 230/149 mmHg. She got several “errors” when trying to obtain BP readings with her automated home BP monitor, but manual readings showed repeatedly BP above 200/100 mmHg (Fig 1). The patient was described as “very anxious whenever he is about to have his BP taken”.

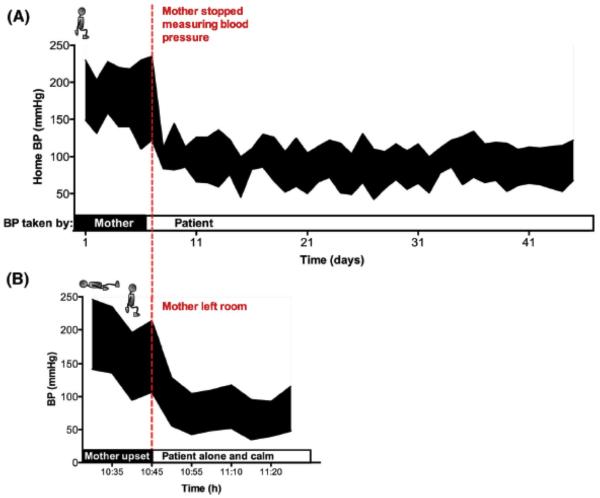

Figure 1. A.

The top tracing shows blood pressure over a six-week period and the bottom tracing shows blood pressure in the office. A) When the mother operated the monitor, the BP was in the hypertensive range. When the patient operated the BP monitor himself (with no involvement of the mother) his BP came back to normal limits. B) At the office, when the mother was present (and upset), BP was hypertensive. Once the mother left, BP decreased back to normal limits. Home blood pressure readings remain normotensive after 1-year follow-up.

Over concerns that he may had developed sustained hypertension owing to his underlying renal disease [2] [4] , ambulatory BP monitoring was performed twice. Surprisingly, the average BP was within normal limits (120/61 mmHg with a highest detected BP of 149/87 mmHg). His mother continued to measure his BP at home and documented severe hypertension, which was refractory to antihypertensive medication (200/115 mmHg 3 hours after 0.05 mg of clonidine). His BP at a routine visit to the nephrologist was 120/75 mmHg.

To further understand the discrepancy between different BP readings, he was examined at our Center with his mother present in the room. He was instructed to lie supine, and fitted with a BP cuff (Press-Mate 8800; Colin Medical Instruments, San Antonio, TX). He subsequently became flushed, sweaty and agitated. BP at that time was 230/149 mmHg. His mother became visibly upset. His BP remained hypertensive when sitting (214/107 mmHg). His mother was then taken out of the room. Within 5 minutes, he relaxed, his BP decreased to 129/56 mmHg, and it remained in the normotensive range over the next 30 minutes (Fig. 1B).

He was given a portable BP cuff (Withings, Issy les Moulineaux, France) compatible with his tablet device and instructed to email to the Center his morning seated BP readings daily for monitoring. His mother and his nurse agreed not to measure his BP or talk about the topic with the patient. His hypertensive response subsided. Over the following 5 weeks, his BP remained within the normal range (Fig 1A). He remains normotensive 1 year later.

Discussion

This case highlights the profound effects of emotions on sympathetic outflow in patients that lack afferent baroreflex control.

In healthy subjects, stressful situations can produce brief but mild increases in BP. This rise, which is due to centrally-mediated sympathetic activation, is rapidly blunted by the baroreflex to avoid excessive BP increases. In patients in whom afferent fibers from baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch traveling the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves have been damaged (i.e., by tumors, surgery, radiotherapy or genetic causes) sympathetic outflow to the blood vessels becomes heavily dependent on emotions [6]. Because surges in sympathetic activity are not restrained by the normal baroreceptor feedback, the increase in BP and heart rate during emotional arousal is amplified and prolonged.

Even mild stressors (phone calls, meals, action sequences in films) can induce dramatic increases in BP and heart rate in subjects with FD [1]. This was particularly evident in this young man, in which the stressor was the mere presence of the patient’s mother during the BP readings. Removal of the stressful emotion that triggered his hypertensive surge (in this case, the presence of his mother during BP readings) normalized his blood pressure.

Our initial concern was that he had developed sustained hypertension owing to his underlying renal disease [2]. Patients with FD have an increased incidence of early onset renal disease, and appear to be susceptible towards hypertensive damage. In hindsight, the case underscores the usefulness of ambulatory BP monitoring [5], which first revealed the discrepancies between the BP obtained by his mother and those not.

Assessment of hypertensive episodes in FD should include the identification of the stressor, close management, and, if appropriate, behavioral therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding source for this work: National Institutes of Health and the Dysautonomia Foundation, Inc.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures related to the article:

LNK: receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (U54NS065736) and the Dysautonomia Foundation, Inc.

JAP: has received fees as consultant for Lundbeck; receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (U54NS065736), the Dysautonomia Foundation, Inc. and the MSA Coalition.

HK: serves on a scientific advisory board for Lundbeck; serves as Editor-in-Chief of Clinical Autonomic Research; receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (U54NS065736 [PI]), the FDA (FD-R-3731-01 [PI]), and the Dysautonomia Foundation, Inc.

References

- 1.Fuente Mora C, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Palma JA, Kaufmann H. Chewing-induced hypertension in afferent baroreflex failure: a sympathetic response? Exp Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1113/EP085340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jelani QU, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Kaufmann H, Katz SD. Vascular endothelial function and blood pressure regulation in afferent autonomic failure. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015;28:166–172. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Axelrod F, Kaufmann H. Afferent baroreflex failure in familial dysautonomia. Neurology. 2010;75:1904–1911. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181feb283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Axelrod FB, Kaufmann H. Developmental abnormalities, blood pressure variability and renal disease in Riley Day syndrome. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;27:51–55. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Kaufmann H. Is ambulatory blood pressure monitoring useful in patients with chronic autonomic failure? Clin. Auton. Res. 2014;24:189–192. doi: 10.1007/s10286-014-0229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson D, Hollister AS, Biaggioni I, Netterville JL, Mosqueda Garcia R, Robertson RM. The diagnosis and treatment of baroreflex failure [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1449–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]