Abstract

The current study evaluated connections between marital distress, harsh parenting, and child externalizing behaviors in line with predictions from the Family Stress Model (FSM). Prospective, longitudinal data came from 273 mothers, fathers, and children participating when the child was 2, between 3 to 5, and 6 to 10 years old. Assessments included observational and self-report measures. Information regarding economic hardship and economic pressure were assessed during toddlerhood, and parental emotional distress, couple conflict, and harsh parenting were collected during early childhood. Child externalizing behavior was assessed during both toddlerhood and middle childhood. Results were consistent with predictions from the FSM in that economic hardship led to economic pressure which was associated with parental emotional distress and couple conflict. This conflict was associated with harsh parenting and child problem behavior. This pathway remained statistically significant controlling for externalizing behavior in toddlerhood.

Keywords: economic hardship, family processes, externalizing behavior

Economic hardship increases risk for behavior problems, mental disorders, and physical health problems and thus represents a significant public health concern (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010; Sareen, Afifi, McMillan, & Asmundson, 2011). Indeed, growing up in an economically disadvantaged household places children at risk for a range of adjustment difficulties (Amato, Booth, Johnson, & Rogers, 2007; Conger & Conger, 2002; Gershoff, Aber, Raver, & Lennon, 2007). Research suggests that economic hardship may affect child development via disrupted family processes including marital distress and harsh parenting (e.g., Conger et al., 2010). According to the Family Stress Model (FSM; Conger & Conger, 2002), these family processes may play a critical role in mediating the effects of economic disadvantage on child outcomes.

Although there has been a number of replication of predictions from the FSM, most studies have used cross-sectional data which is limited in terms of evaluating the hypothesized temporal ordering of causal influences. Therefore, it is important to conduct tests of the FSM using longitudinal data (Conger et al., 2010; Donnellan, Martin, Conger, & Conger, 2013). Furthermore, much of the research investigating the FSM has involved adolescents rather than the development of younger children (Donnellan et al., 2013). Moreover, few studies have included all of the measures as proposed in the original FSM. For example, many studies include economic hardship, parental emotional distress, and harsh or positive parenting, but may not account for economic pressure or couple conflict within the model. For instance, White, Liu, Nair, and Tein (2015) examined elements of the FSM from late childhood to middle adolescence in a sample of Mexican origin families. Although this study used a longitudinal design, it did not include all key pathways of the FSM and was focused on adolescents rather than younger children. With these ideas in mind, the present investigation extended earlier research testing predictions from the FSM by studying changes in child development over time during early to middle childhood. Specifically, we investigated all key pathways of the FSM which include economic hardship, economic pressure, disrupted interpersonal processes, and child problem behavior using a sample of families with children moving from toddlerhood to the elementary school years. We used longitudinal data so we could evaluate relative change in problem behavior across time by controlling for earlier levels.

The Family Stress Model

Economic adversity has been associated with a range of child outcomes, including elevated risk for behavior problems (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Evans & English, 2002), reduced social competence (Bolger, Patterson, Thompson, & Kupersmidt, 1995), lower cognitive ability (Gershoff et al., 2007), and elevated physiological markers of stress (Evans & English, 2002). Moreover, family income and socioeconomic status are both related to a number of factors including harsh parenting and externalizing problems in youth (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). An important issue is how to tie these findings together into an integrated model that helps to understand the processes underlying these associations. In particular, the Family Stress Model (FSM) proposes that both social and economic situations create differences in developmental outcomes for children and their parents (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). The FSM focuses on social and emotional pathways through which economic problems affect significant developmental difficulties for children, especially when poverty is severe or persistent (Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor, 2001; Duncan & Magnuson, 2003; Magnuson & Duncan, 2002). The model was originally developed to help explain how economic disadvantage affected the lives of families experiencing the agricultural economic downtown in the 1980s in the rural United States (see Conger & Conger, 2002).

The FSM proposes that economic hardship leads to economic pressure in the family. Markers of hardship may include low income, negative financial events, high debts relative to assets, or whether a family meets governmental guidelines for defining poverty status (e.g., Conger, et al., 2012). These objective economic conditions are expected to influence family functioning and child adjustment primarily through the economic pressures they generate. Pressures such as unmet material needs (e.g., inadequate food or clothing), the inability to pay bills or make ends meet, and having to cut back on necessary expenses (e.g., health insurance, medical care) are the psychological manifestations and responses to economic hardships. These pressures are thought to place parents at increased risk for emotional distress (e.g., depression, anxiety, anger). These emotional problems are then expected to increase conflict between parents which, in turn, disrupts supportive parenting. Parents preoccupied by their personal problems and marital distress are expected to demonstrate less affection and more hostility toward their partner. These disruptions in the relationships between parents are expected to “spill over” into interactions with children thus leading to harsh and inconsistent parenting, a key proximal influence on the social and emotional well-being of children. In short, disrupted interpersonal processes are a key conduit for connecting economic problems to child developmental outcomes.

Empirical support for the FSM was first demonstrated with data when the parents in the present study were adolescents (see Conger & Conger, 2002; Conger et. al., 2010). The current study extends this previous work by focusing on those adolescents from the original project who have now grown to adulthood and had children of their own. Since the initial supportive findings for the FSM, several other independent studies have replicated specific pathways within the model (see also Behnke et al., 2008; Conger et al., 2002; Gershoff et al., 2007; Mistry et al., 2008; Mistry, Lowe, Benner, & Chien, 2008; Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002; Parke et al., 2004; Scaramella, Sohr-Preston, Callahan, & Mirabile, 2008; Yeung, Linver, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; Yoder & Hoyt, 2005). For example, White et al. (2015) found that economic pressure was associated with increases in harsh parenting for Mexican origin mothers. Harsh parenting was related to increases in adolescent externalizing behavior. Similarly, Ponnet (2014) examined financial stress in families with different income levels. Results showed that for all families, parental depressive symptoms, interparental conflict, and positive parenting mediated the relation between financial stress and adolescent problem behavior. Finally, Newland, Crnic, Cox, and Mills-Koonce (2013) found that economic pressure was associated with maternal depression and somatization, which in turn were significantly related to decreases in sensitive and supportive parenting practices. We extend this work by investigating all key elements of the original FSM into one analysis with a sample of young children.

Likewise, other studies have successfully applied the FSM to families and other diverse racial groups who live outside of the U.S. (e.g., Aytaç & Rankin, 2009; Borge, Rutter, Cote, & Tremblay, 2004; Gutman, McLoyd, & Tokoyawa, 2005; Prior, Sanson, Smart, & Oberklaid, 1999; Robila & Krishnakumar, 2005; Solantaus, Leinonen, & Punamäki, 2004; Wickrama, Noh, & Bryant, 2005; Zevalkink & Riksen-Walraven, 2001). A recent study of Turkish minority mothers in the Netherlands found that maternal stress mediated the association between socioeconomic status and parenting (Emmen et al., 2014). Thus, a wide range of studies have found support for the mediating pathways proposed by the FSM.

The Present Investigation

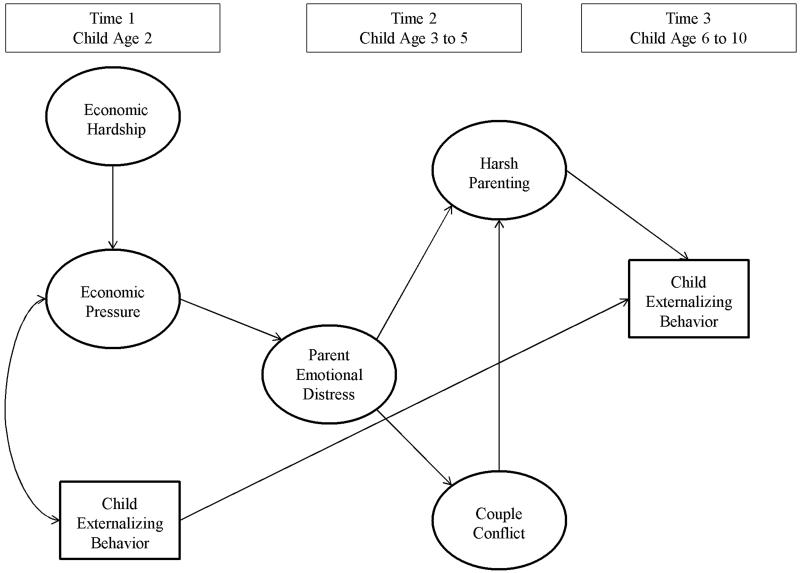

The present study tested predictions derived from the FSM to understand how economic hardship is associated with externalizing problems in young children. Specifically, family economic hardship and economic pressure were assessed when the child was two years old. Parental emotional distress, observed couple conflict, and observed hostile parenting were assessed when the child was between the ages of three and five years old. These variables were then used to predict child externalizing behavior assessed when the child was between the ages of six and ten years old (see Figure 1) while also including earlier levels. The current study contributes to the body of literature by examining the effects of economic pressure over time; from toddlerhood through late childhood. As illustrated in Figure 1, the FSM proposes that economic hardship leads to economic pressure. The model also posits that parents experiencing economic pressure will show higher levels of emotional distress, which will lead to couple conflicts and hostile parenting. In line with the FSM, the association between couple conflict and child outcomes is thought to be mediated by disrupted parenting processes. Therefore, we did not predict that couple conflict would directly influence child behavior. Because we controlled for problem behavior of the child during the toddler years, the model predicts relative change in child adjustment over time.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

In the present investigation we also controlled for the age of the parent and child, as well as gender for parent and child. Previous research shows that these control variables may be related to parenting behaviors. For example, research investigating demographic characteristics such as age and gender found that younger mothers have an increased chance of negative life outcomes. In a study of children born to mothers younger than 19 years of age, sons were more likely than daughters to experience externalizing problems (Pogarsky, Thornberry, & Lizotte, 2006). In terms of child age, mothers with older compared to younger boys showed less effective parenting and older sons showed an increase in antisocial behavior (Bank, Forgatch, Patterson, & Fetrow, 1993).

Method

Participants

Data are drawn from the Family Transitions Project (FTP), a longitudinal study of 559 target youth and their families. The FTP represents an extension of two earlier studies: The Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP) and the Iowa Single Parent Project (ISPP). In the IYFP, data from the family of origin (N=451) were collected annually from 1989 through 1992. Participants included the target adolescent, their parents, and a sibling within 4 years of age of the target adolescent (217 females, 234 males). These 451 families were originally recruited for a study of family economic stress in the rural Midwest. When interviewed in 1989, the target adolescent was in seventh grade (M age = 12.7 years; 236 females, 215 males). Families were recruited from schools in eight rural Iowa counties. Due to the rural nature of the sample there were few minority families (approximately 1% of the population); therefore, all participants were Caucasian. Seventy-eight percent of eligible families agreed to participate in the study. Families were primarily lower middle- or middle-class with thirty-four percent residing on farms, 12% living in nonfarm rural areas, and 54% living in towns with fewer than 6,500 residents. In 1989, parents averaged 13 years of schooling and had a median family income of $33,700. Fathers’ average age was 40 years, while mothers’ average age was 38.

The ISPP began in 1991 when the target adolescent was in 9th grade (M age = 14.8 years), the same year of school for the IYFP target youth. Participants included the target adolescents, their single-parent mothers, and a sibling within 4 years of age of the target adolescent (N=108). Families were headed by a mother who had experienced divorce within two years prior to the start of the study. All but three eligible families agreed to participate. The participants were Caucasian, primarily lower middle- or middle-class, one-parent families that lived in the same general geographic area as the IYFP families. Measures and procedures for the IYFP and ISPP studies were identical.

In 1994, families from the ISPP were combined with families from the IYFP to create the FTP. At that time adolescents from both studies were in 12th grade. In 1994, target youth participated in the study with their parents as they had during earlier years of adolescence. Beginning in 1995, the target adolescent (1 year after completion of high school) participated in the study with a romantic partner or friend. In 1997, the study was expanded to include the first-born child of the target adolescent, now a young adult. To be eligible for the study, the target’s child had to be at least 18 months of age. By 2005, the children of the FTP targets ranged in age from 18 months to 13 years old.

The present report includes 273 target adults (M age = 29.1; males = 113) who had an eligible child participating in the study at least once by 2005. The report also includes the target’s romantic partner (spouse, cohabitating partner, or boy/girlfriend) who was either the other biological parent, step-parent, or parental figure to the target’s child. The data were analyzed at the three developmental periods. Time 1 included 228 children at age 2 (boys = 122). Time 2 included 222 children ranging from 3 to 5 years of age (M child age = 3.2 years; boys = 119). Since the same child could participate at age 3-5, we include data only from the first time a child was assessed during that time period to assure that the same child is not counted within that age range multiple times. A total of 190 3-year-olds, 24 4-year-olds, and 8 5-year-olds participated at Time 2. Time 3 included 125 children between the ages of 6 and 10 years old (M child age = 6.1 years). Again, we included data only from the first time a child was assessed during that age range: 111 6-year olds, 11 7-year-olds, 1 8-year-olds, 1 9-year-old, and 1 10-year-old child participated (75 boys).

Procedures

From 1997 through 2005, each target parent, their romantic partner, and the target’s first-born child were visited in their home each year by a trained interviewer. During the visit, the target parent and his/her romantic partner completed a number of questionnaires, some of which included measures of parenting and individual characteristics. In addition to questionnaires, the target parents and their children participated in two separate videotaped interaction tasks. These tasks included a parent-child puzzle completion task and a clean-up task. Observational codes derived from both the puzzle completion task and clean-up task were used for this study. Target parents and their children were presented with a puzzle that was too difficult for children to complete alone. Parents were instructed that children must complete the puzzle alone, but they could provide any assistance necessary. The task lasted 5 minutes. Puzzles varied by age group so that the puzzle slightly exceeded the child’s skill level. The clean-up task was completed at the end of the in-home visit. The task began after the child played with a variety of toys, first alone (for 6 minutes) and then with the interviewer present (5 minutes). The target parent was asked to return to the room and subsequently instructed that it was time for their child to clean-up the toys. The interviewer informed the target parent that he or she could offer help to the child as necessary, but the child was expected to clean-up the toys alone. Both interaction tasks created a stressful environment for both parent and child and the resulting behaviors indicated how well the parent handled the stress and how adaptive the child was to an environmental challenge. Trained observers coded aspects of harsh parenting from video recordings of the puzzle and clean-up tasks using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby et al., 1998).

Also during this assessment, the target adult and his or her romantic partner participated in a videotaped 25-minute discussion task. This interaction task allowed for the discussion of various topics such as childrearing, employment, and other life events. Trained observers rated the quality of interactions during these tasks using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby et al., 1998). The project observers were staff members who had received training on rating family interactions and specialized in coding one of the interaction tasks. The FTP has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Iowa State University. Additional details regarding each interaction task are provided in the following discussion of study measures.

Measures

The means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum scores for all study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables (N = 273).

| Variables | M | SD | Min | Max | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Hardship A | |||||

| Income-to-needs Ratio | −3.70 | 1.92 | −11.92 | 0.00 | |

| Economic Pressure A | |||||

| Unmet Material Needs | 13.01 | 4.68 | 6.00 | 30.00 | .65 |

| Can’t Make Ends Meet | 0.00 | 1.83 | −3.16 | 4.83 | .88 |

| Cutbacks | 3.63 | 3.76 | 0.00 | 18.00 | .76 |

| Emotional Distress B | |||||

| Depression | 1.38 | 0.46 | 1.00 | 4.38 | .91 |

| Anxiety | 1.15 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 4.60 | .77 |

| Hostility | 1.32 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 5.00 | .81 |

| Couple Conflict B | |||||

| Hostility | 3.99 | 2.37 | 1.00 | 9.00 | .97 |

| Antisocial | 5.16 | 1.98 | 1.00 | 9.00 | .88 |

| Angry Coercion | 2.08 | 1.81 | 1.00 | 9.00 | .70 |

| Harsh Parenting B | |||||

| Hostility | 2.61 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 8.50 | .99 |

| Antisocial | 3.40 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 8.50 | .89 |

| Angry Coercion | 2.38 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 9.00 | .95 |

| Child Externalizing Behavior A (2) | 49.56 | 7.06 | 30.00 | 67.00 | |

| Child Externalizing Behavior C (6 to 10) | 52.04 | 8.41 | 33.00 | 71.00 | |

| Target Parent Age A | 26.34 | 2.55 | 20.69 | 30.28 |

Notes.

(Time 1). Target’s child 2 years old;

(Time 2). Target’s child 3,4, or 5 years old,

(Time 3). Target’s child 6,7,8,9 or 10 years old.

Economic hardship (Time 1)

Economic hardship was measured as low income-to-needs when the child of the target parent was two years old (see Conger et al., 2012). Low income-to-needs ratio was calculated for by dividing total family income by the poverty level for a family of a given size (see U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1989), and then multiplied by −1 so that high scores reflect a low income level.

Economic pressure (Time 1)

Economic pressure was measured when the target’s child was two years old. It was a latent construct with three indicators: unmet material needs, can’t make ends meet, and cutbacks. Unmet material needs included six items asking the Target parent whether they had enough money to afford adequate housing, clothing, furniture, car, food, and medical care. Each item ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. All items were summed together and the scale had an alpha coefficient of .91.

The second indicator was not being able to make ends meet. Two items asked the target parent whether they had difficulty paying their bills (1 = a great deal of difficulty to 5 = no difficulty at all) and how much money they have left at the end of each month (1 = more than enough money left over to 4 = not enough to make ends meet). The first item was recoded and then both items were standardized and summed together. The correlation between the two items was .67.

The last indicator, cutbacks, consisted of 29 items which asked the target parent whether they had made significant financial cutbacks in the past 12 months. Questions included items such as postponing medical or dental care, changing food shopping or eating habits to save money, and taking an extra job to help meet expenses. Each item was answered by 1 = yes or 0 = no. All items were summed together and demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = .83).

Emotional distress (Time 2)

Emotional distress was assessed through target self-report using the depression, anxiety, and hostility subscales from the SCL-R-90 (Derogatis, 1994) when their child was three, four, or five years of age. Items from each subscale were summed and used as a separate indicator for the latent construct. Response categories assessed how distressed the parent felt during the past week, ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely. For the depression scale, Target parents were asked 13 questions regarding depressive symptoms such as crying easily or feelings of worthlessness. The anxiety subscale included 10 questions assessing behavior such as nervousness or shakiness inside, suddenly feeling scared for no reason, and feeling fearful. Finally, hostility included 6 items asking questions related to feeling easily annoyed or irritated, having temper outbursts that you could not control, and having the urge to break or smash things. The alpha coefficients for the subscales were .89, .92, and .82, respectively.

Couple conflict (Time 2)

Observer ratings were used to assess the target’s hostility, antisocial behavior, and angry coerciveness toward his or her romantic partner during the romantic partner discussion task. This task was assessed when the target parent’s child was either three, four, or five years old. Each rating was scored on a 9-point scale, ranging from low (no evidence of the behavior) to high (the behavior is highly characteristic of the parent). Each scale was used as a separate indicator for the latent construct. Hostility measures hostile, angry, critical, disapproving and/or rejecting behavior. Antisocial is the demonstration of socially irresponsible behavior, including resistance, defiance, and insensitivity. Angry coercion is the attempt to control or change the behavior of another in a hostile manner. It includes demands, hostile commands, refusals, and threats.

During the romantic partner discussion task, couples discussed questions from a series of cards. Each person took turns reading questions related to subjects such as household responsibilities, each other’s family, and raising a child. The person reading the card was instructed to read each question out loud and give his or her answers first. The other person was instructed to give their answer next and then the couple talked together about the answers that were given. They were to go on to the next card once they felt as though they had said everything they wanted to about each question. The observational ratings were internally consistent (α = .88) and interobserver agreement was high (α = .94).

Harsh parenting (Time 2)

Direct observations assessed target harsh parenting behaviors to their three, four, or five year old child during the videotaped puzzle and clean-up tasks. Trained observers rated the same behaviors as for couple conflict. Hostility, antisocial, and angry coercion were rated by observers on a 9-point scale. Each scale was averaged across tasks and used as a separate indicator for the latent construct. The scores for the harsh parenting construct were internally consistent (α = .96) and inter-rater reliability was substantial (α = .94). The observers used to code the parenting tasks were different than the observers who coded the romantic partner discussion task. Therefore, different informants generated the behavioral scores for couple conflict and harsh parenting.

Child externalizing behavior (Time 1)

Target parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1 ½ - 5 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) when their child was two years old. Externalizing behavior included five items from the attention problems subscale and 19 items from the aggressive behavior subscale. Target parents rated each statement on a 3-point scale ranging from not true to very true regarding their child’s behavior during the past 2 months. Sample items from the attention problems subscale included can’t concentrate, can’t sit still, and wanders away. Attention problems included items such as is defiant, hits others, and has angry moods. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients indicated very good internal consistency (α = .84). Items were averaged across subscales to create a total externalizing score. The total score was standardized.

Child externalizing behavior (Time 3)

Target parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 6-18 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) when their child was between 6 and 10 years old. Scores included the first time the child was assessed during that age range. Externalizing behavior included the 17 item rule-breaking and 18 item aggressive behavior subscales. Target parents rated each statement on a 3-point scale ranging from not true to very true regarding their child’s behavior during the past 2 months. Sample items from the rule-breaking subscale include lacks guilt, runs away, and lies or cheats. Sample items from the aggressive behavior subscale include argues a lot, gets in fights, attacks people, and is disobedient at home and at school. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients indicated very good internal consistency (α = .85). Items were averaged across the subscales to create a total score which was standardized.

Control variables

The control variables measured at time 1 when the child was two years old included target report of their gender and their child’s gender (1 = male, 2 = female), and target self-report of their age when their child was 2 years old. Target self-report of their relationship status (1 = married or cohabiting, 0 = not married or cohabiting) was measured at time 2 when their child was 3, 4, or 5 years old.

Results

Correlations among Constructs

Table 2 shows the zero-order correlations among theoretical constructs. Consistent with theoretical predictions, economic hardship was significantly correlated with economic pressure (r = .42, p < .001), which was significantly correlated with parental emotional distress (r = .27, p < .01), as well as with externalizing behaviors in children between the ages of 6 and 10 years old (r = .21, p < .05). Parental emotional distress was also significantly correlated with couple conflict (r = .20, p < .05), harsh parenting (r = .26, p < .001) and externalizing behaviors in children between the ages of 6 and 10 (r = .28, p < .001). Couple conflict was significantly correlated with harsh parenting (r = .36, p < .001), which, in turn, was significantly related to child externalizing behaviors at ages of 6 and 10 (r = .29, p < .01). There was stability for externalizing behavior in children at age 2 to externalizing behavior in children ages 6 and 10 (r = .36, p < .001). The patterns of associations were consistent with expectations and justified the formal test of the model.

Table 2. Correlations among Variables Used in Analyses.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic HardshipA | |||||||||||

| 2. Economic PressureA | .42*** | ||||||||||

| 3. Emotional DistressB | .22** | .27** | |||||||||

| 4. Couple ConflictB | .18** | .01 | .20* | ||||||||

| 5. Harsh ParentingB | .22** | .13 | .26*** | .36*** | |||||||

| 6. Child ExternalizingA (2) | .08 | .24** | .31*** | −.07 | .14† | ||||||

| 7. Child ExternalizingC (6 to 10) | .09 | .21* | .28*** | .01 | .29** | .36*** | |||||

| 8. Target GenderA | −.02 | −.02 | −.17* | −.21** | −.06 | −.01 | −.07 | ||||

| 9. Child GenderA | −.01 | .07 | −.09 | .00 | .12† | .11 | −.02 | .04 | |||

| 10.Target Relationship StatusA | −.19* | −.25** | .06 | .26*** | .02 | .07 | −.07 | .10 | −.13† | ||

| 11.Target AgeA | −.42*** | −.19** | −.10 | −.40*** | −.28** | −.10 | .04 | .20** | −.03 | .04 |

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p<.01

p < .000.

(Time 1). Target’s child 2 years old,

(Time 2). Target’s child 3,4, or 5 years old,

(Time 3). Target’s child 6,7,8,9 or 10 years old.

Structural Equation Analyses

Structural equation models (SEMs) were estimated using the Mplus 7.0 software package (Muthen & Muthen, 2012) and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation procedures. FIML procedures are recommended for handling missing data in longitudinal research (Allison, 2003). Economic hardship, economic pressure, emotional distress, couple conflict, and harsh parenting were examined as latent variables. Child externalizing behavior at age 2 and 6 to 10 was examined as manifest variables. The SEMs were estimated in two ways. First, models were estimated with all of the control variables in the analyses: target relationship status, target age, and gender for both target parent and child. Second, the models were specified without the control variables. Separate analyses generated similar findings; therefore, we present the results without the inclusion of the control variables in the final model.

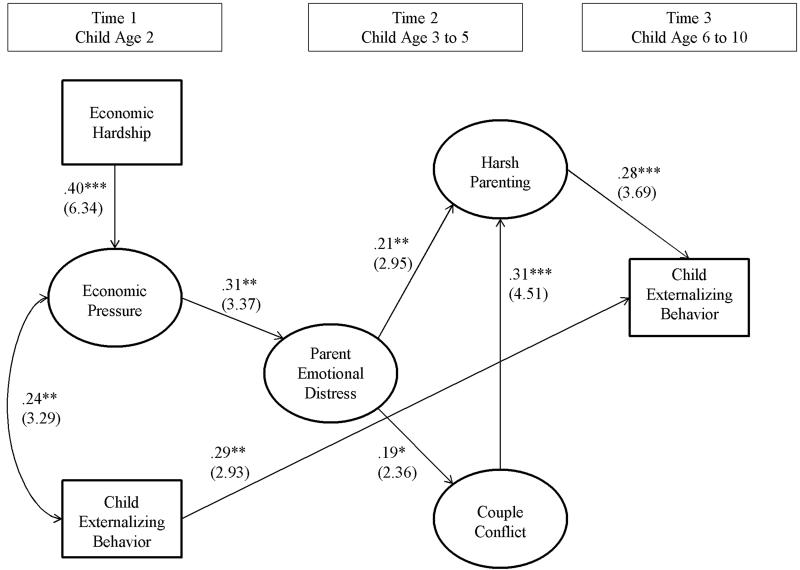

Several fit indices were used to evaluate the fit of structural models to the data. First, the standard chi–square value was evaluated. Two indices of practical fit, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and the comparative fit index (CFI; Hu & Bentler, 1999) were also used. RMSEA values under .05 indicate close fit to the data, and values between .05 and .08 represent reasonable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the CFI, fit index values should preferably be greater than .95 to consider the fit of a model to data to be acceptable. This model showed an acceptable fit, χ2 (84) = 129.34, p < .001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .044, and was the model used for our primary analyses. Factor loadings for all variables ranged from .65 to .99 (see Table 1). Standardized coefficients from the final model which reached statistical significance are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Statistical Model.

Consistent with theoretical predictions, economic hardship was significantly associated with higher levels of economic pressure (β = .40, SE = .06). Economic pressure was significantly associated with higher parental emotional distress (β = .31, SE = .09). Parental emotional distress was significantly associated with higher levels of couple conflict (β = .19, SE = .08) and higher levels of harsh parenting (β = .21, SE = .07). Couple conflict was significantly associated with higher levels of harsh parenting (β = .31, SE = .07), which, in turn, was significantly associated with externalizing behaviors in children between the ages of 6 and 10 (β = .28, SE = .08). There was stability from externalizing behavior in children at age 2 to externalizing behavior in children ages 6 and 10 (β = .29, SE = .10).

Indirect effects

In addition to examining the direct relationships within the model, we also examined the significance of the mediating pathways through which economic pressure is associated with child problem behavior. All indirect analyses were conducted using the capabilities of Mplus to estimate indirect effects (Muthen & Muthen, 2012). Results indicated that the direct association between economic pressure and externalizing behavior at ages 6 to 10 was significant (β = .24, SE = .11). However, when emotional distress, couple conflict, and harsh parenting were added to the model, the direct relation between economic pressure and externalizing during middle childhood was no longer significant (β = .15, SE = .12). In addition, economic pressure was not associated with couple conflict or harsh parenting. Rather, there was a significant indirect effect through emotional distress for harsh parenting (β = .06, SE = .03 and a significant indirect effect through emotional distress for couple conflict (β = .06, SE = .03). Couple conflict did not directly predict externalizing behavior in children between ages 6 and 10, rather it was related through harsh parenting even after controlling for earlier externalizing behavior in children at age 2 (β = .09, SE = .03).

Finally, the SEMs were re-estimated to ascertain whether child problem behavior at age 2 impacted the other variables in the model. Specifically, pathways from early problem behavior to parental emotional distress, couple conflict, and harsh parenting were added to the model. In addition, the path from economic hardship to early child problem behavior was also included. Consistent with study expectations, the inclusion of these additional pathways did not change the results as outlined above.

Discussion

The present investigation applied the Family Stress Model (FSM) to evaluate connections between economic adversity, family processes and child externalizing problems across time. We tested how economic hardship related to economic pressure in the family and, in turn, how economic pressure was related to both parental emotional distress and couple conflict, as well as harsh parenting behavior. These family processes were examined in relation to child externalizing behavior in middle childhood while controlling for earlier levels during the toddler years. This study adds to the existing literature surrounding the FSM by using longitudinal data and studying younger children at three developmental time points. Results showed support for the model in that economic hardship as experienced when children were toddlers was associated with economic pressure felt within the family. Economic pressure was related to parental emotional distress when children moved into the preschool years. This distress was associated with observed conflict between the couple, which in turn, was associated with higher levels of observed harsh parenting. Harsh parenting during early childhood was directly related to childhood problem behavior during middle childhood. This was true even after earlier child problem behavior was taken into account. These results suggest that economic pressure, emotional distress, and couple conflict are associated with parenting and thus may contribute to externalizing problems in later childhood.

Altogether, the current results replicate and extend previous studies examining economic adversity, family processes, and child developmental outcomes. For example, the current findings replicate results with the first two generations from the present study (see Conger & Conger, 2002; Conger et. al., 2010). That is, the pathways of the FSM operated similarly both when target parents were adolescents in the family of origin, and when they became parents themselves. Both generations of adults within the study experienced economic pressure which influenced parenting and led to problematic youth outcomes. The present study extends this original work by examining these processes with younger children. Future research should continue to extend the model from early childhood into later adolescence. Continuing to research children during developmentally sensitive periods may hold an important key to understanding the impact of economic stressors on development throughout childhood and adolescence.

The current results also extend work conducted by other researchers. For example, Gershoff et al. (2007), Ponnet (2014), and Yeung et al. (2002) found that the association between economic adversity and child behavioral outcomes was mediated through parental distress and parenting practices. Likewise, Parke et al. (2004) replicated the FSM and found that economic hardship was related to economic pressure which was associated with parental depressive symptoms, marital problems, and harsh parenting. These problems, in turn, were related to child adjustment problems. While studies such as these included nationally represented samples (e.g., Gershoff et al., 2007), or reports by multiple reporters (e.g., Parke et al., 2004; Yeung et al., 2002), some limitations with this earlier work include being cross-sectional in nature, relying solely on self-report data, or focusing only on mother’s behavior. Indeed, Parke et al. (2004) pointed out that it is important to replicate FSM findings using a multi-method, multi-reporter, longitudinal design. Therefore, the current study used a prospective, longitudinal design which helps to eliminate retrospective biases. It also used multiple reporters which included observer ratings of parenting behavior and couple conflict, as well as mother and father-reported measures of economic adversity, emotional distress, and child behavior.

In addition, Solantaus et al. (2004) examined children’s mental health before Finland’s economic recession in order to examine whether change in a family’s economic situation led to problematic child behavior. They found that after controlling for pre-recession child mental health, economic hardship led to changes in children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior. While this study controlled for earlier child behavior, the data collected during the recession occurred at one time point. It was concluded that findings pertained to changes in economic circumstances rather than how persistent the consequences of adversity could be. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to investigate such relations between economic disparity and child developmental outcomes (Solantaus et al., 2004). The current study extends these findings by investigating the impact of economic hardship as assessed in toddlerhood on child problem behavior up to four years later.

Unlike many of the earlier studies that have used cross-sectional data, White et al. (2015) tested pathways of the FSM from late childhood to middle adolescence. Likewise, Mistry et al. (2008) used longitudinal data to examine the effects of socioeconomic status on children’s behavioral outcomes in a sample of low-income, immigrant families. They also included earlier assessments of children’s behavior as covariates in the analyses. Their results were consistent with the present study in that parental socialization practices mediated the effects of SES on children’s aggressive behavior. While White et al. (2015) and Mistry et al. (2008) both used longitudinal data to examine the socialization pathways consistent with the FSM, they did not include all of the family variables as outlined in the original model. For example, White et al. (2015) did not assess economic hardship, psychological distress, or marital interactions, and Mistry et al. (2008) did not include economic pressure or marital interactions. Therefore, the present study extends these findings by including all pathways consistent with the FSM.

It should be acknowledged that there are alternative explanations for some of the findings. It could be that shared genetic factors passed directly from parent to child help explain some of the observed associations. Similarly, genetically influenced individual differences in children might elicit particular parenting practices (Klahr & Burt, 2014). For example, Oliver, Trzaskowski, and Plomin (2014) examined heritability of parent reports of parenting in a large twin sample. They found genetic heritability for negative aspects of parenting, and similar characteristics of children elicited negativity from parents. However, other studies examining observed parenting behaviors found little or no evidence of genetic influences on parenting (Fearon et al., 2006; Neiderhiser et al., 2004), thus highlighting the varying estimates of genetic influences across studies (Klahr & Burt, 2014). In addition to genetic differences in parenting, there may be genetically influenced differences contributing to the emotional distress of those parents experiencing economic difficulties. Thus, future research should evaluate genetic factors within the pathways of the FSM. In addition, there are contemporaneous effects that could influence the association between economic disparity and child developmental outcomes. For example, it could be that economic hardship at time 1 predicts economic hardship at times 2 and 3, which helps further explain how economic hardship at time 1 is related to child externalizing at time 3. The idea is that current economic hardship is more relevant than previous levels and this possibility could be explored in future tests of the FSM. There are also limitations of this study worthy of comment. The sample was primarily white and came from the rural Midwest which could limit generalizability of the findings; however as outlined in this report, earlier research has shown similar findings using more diverse samples. These earlier findings help to increase the confidence in the current results.

The current results have applied implications. In particular, economic adversity is associated with a host of disadvantages including parental emotional distress, couple conflict, harsh parenting, and the development of child problematic behavior into the middle school years. Thus, prevention efforts aimed at mitigating the effects of economic hardship by focusing on family functioning may be beneficial in reducing child negative outcomes. For example, strategies to improve parent psychological wellbeing, couple relationships, or parenting practices during times of stress (Walsh, 2012) may be helpful in preventing negative consequences for children. Indeed, parenting that is high in warmth and effective communication has been associated with child positive outcomes even for families facing economic disparity (Neppl, Jeon, Schofield, & Donnellan, 2015). By increasing supportive family interactions, such intervention efforts may help foster long lasting positive developmental outcomes for children exposed to economic hardship. In addition, direct efforts to alleviate economic pressure such as antipoverty programs are also important for helping families cope with economic adversity.

In sum, the present results suggest that economic pressure contributes to interpersonal distress which is associated with conflict between parents. These observed interactions are associated with parenting behaviors marked by hostility and coercion. These kinds of observed parenting behaviors, in turn, are associated with child behavior problems. Understanding the impact that economic pressure has on family relationships and child development over time can help pave the way for policy makers and mental health professionals working with families living in economically challenging times.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD064687). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, MH48165, MH051361), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724, HD051746, HD047573), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Contributor Information

Tricia K. Neppl, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, 4389 Palmer Suite 2356, Ames, IA 50011.

Jennifer M. Senia, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, jmsenia@iastate.edu.

M. Brent Donnellan, Dept. of Psychology, Texas A & M University, 4235 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843; mbdonnellan@tamu.edu; phone: 979-845-2581.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Booth A, Johnson D, Rogers S. Alone together: How marriage in America is changing. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aytaç IA, Rankin BH. Economic crisis and marital problems in Turkey: Testing the family stress model. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:756–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00631.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Forgatch M, Patterson GR, Fetrow RA. Parenting practices of single mothers: Mediators of negative contextual factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:371–384. doi: 10.2307/352808. [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, MacDermid SM, Coltrane SL, Parke RD, Duffy S, Widaman KF. Family cohesion in the lives of Mexican American and European American parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1045–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00545.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Thompson WW, Kupersmidt JB. Psychosocial adjustment among children experiencing persistent and intermittent family economic hardship. Child Development. 1995;66:1107–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00926.x. [Google Scholar]

- Borge AIH, Rutter M, Cote S, Tremblay RE. Early childcare and physical aggression: Differentiating social selection and social causation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00227.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children. 1997;7:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Martin MJ, Reeb BT, Little WM, Craine JL, Shebloski B, Conger RD. Economic hardship and its consequences across generations. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. Oxford Handbook of Child Development and Poverty. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:361–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ebert-Wallace L, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody G. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, McCartney K, Taylor BA. Change in family income-to-needs matters more for children with less. Child Development. 2001;72:1779–1793. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Symptom checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R): Administration, scoring and procedures manual. National Computer Systems; Minneapolis, MN: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Monica MJ, Conger KJ, Conger RD. Economic distress and poverty in families. In: Fine MA, Fincham FD, editors. Handbook of family theories: A content-based approach. Routledge/Psychology Press; New York: 2013. pp. 338–355. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson KA. Off with Hollingshead: Socioeconomic resources, parenting, and child development. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Emmen RAG, Malda M, Mesman J, van IJzendoorn MH, Prevoo MJL, Yeniad N. Socioeconomic status and parenting in ethnic minority families: Testing a minority family stress model. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:896–904. doi: 10.1037/a0034693. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon RM, Fonagy P, Schuengel C, Van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Bokhorst CL. In search of shared and nonshared environmental factors in security of attachment: A behavior-genetic study of the association between sensitivity and attachment security. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1026–1040. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, Lennon MC. Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development. 2007;78:70–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, McLoyd VC, Tokoyawa T. Financial strain, neighborhood stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescent adjustment in urban African American families. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:425–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00106.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternative. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Klahr AM, Burt SA. Elucidating the etiology of individual differences in parenting: A meta-analysis of behavioral genetic research. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:544–586. doi: 10.1037/a0034205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson KA, Duncan GJ. Parents in poverty. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Volume 4. Social conditions and applied parenting. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 95–121. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Jayaratne TE, Ceballo R, Borquez J. Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: Effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Child Development. 1994;65:562–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00769.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby J, Conger R, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, Scaramella L. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. Fifth Edition Iowa State University, Institute for Social and Behavioral Research; Ames: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC. Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development. 2002;73:935–951. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00448. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Lowe ED, Benner AD, Chien N. Expanding the family economic stress model: Insights from a mixed-methods approach. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:196–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00471.x. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Fifth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Lichtenstein P, Hansson K, Cederblad M, Elthammer O, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on mothering of adolescents: A comparison of two samples. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:335–351. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.335. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland RP, Crnic KA, Cox MJ, Mills-Koonce R. The family model stress and maternal psychological symptoms: Mediated pathways from economic hardship to parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:96–105. doi: 10.1037/a0031112. doi: 10.1037/a0031112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Jeon S, Schofield TJ, Donnellan MB. The impact of economic pressure on parent positivity, parenting, and adolescent positivity into emerging adulthood. Family Relations. 2015 doi: 10.1111/fare.12098. doi: 10.1111/fare.12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver BR, Trzaskowski M, Plomin R. Genetics of parenting: The power of the dark side. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:1233–124. doi: 10.1037/a0035388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, French S, Widaman KF. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogarsky G, Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ. Developmental outcomes for children of young mothers. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2006;68:332–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00256.x. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K. Financial stress, parent functioning and adolescent problem behavior: An actor-partner interdependence approach to family stress processes in low-, middle-, and high-income families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:1752–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0159-y. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Sanson A, Smart D, Oberklaid F. Psychological disorders and their correlates in an Australian community sample of preadolescent children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:563–580. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robila M, Krishnakumar A. Effects of economic pressure on marital conflict in Romania. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:246–251. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.246. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG. Relationship between household income and mental disorders: Findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:419–427. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Sohr-Preston SL, Callahan KL, Mirabile SP. A test of the family stress model on toddler-aged children’s adjustment among Hurricane Katrina impacted and non-impacted low income families. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:530–541. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148202. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewski JM, Amato PR. Economic hardship in the family of origin during childhood and psychological well-being in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:141–156. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00011.x. [Google Scholar]

- Solantaus T, Leinonen J, Punamäki RL. Children’s mental health in times of economic recession: Replication and extension of the family economic stress model in Finland. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:412–429. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S Bureau of the Census . Money income and poverty status in the United States: 1988 (series P-60, No. 166) U.S. Department of Commerce; Washington, DC: Oct, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Family resilience: Strengths forged through adversity. In: Walsh F, editor. Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity. 4th ed. Guilford; New York: NY: 2012. pp. 399–427. [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Liu Y, Nair RL, Tein JY. Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:649–662. doi: 10.1037/a0038993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0038993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Noh S, Bryant C. Racial differences in adolescent distress: Differential effects of the family and community for blacks and whites. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:261–282. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20053. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung WJ, Linver MR, Brooks-Gunn J. How money matters for young children’s development: Parental investment and family processes. Child Development. 2002;73:1861–1879. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KA, Hoyt DR. Family economic pressure and adolescent suicide ideation: Application of the family stress model. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:251–264. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.251. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zevalkink J, Riksen-Walraven JMA. Parenting in Indonesia: Inter- and intracultural differences in mothers’ interactions with their young children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:167–175. doi: 10.1080/01650250042000113. [Google Scholar]