Abstract

The current study used data from the ECLS-B to explore determinants of resident father involvement. Families (N=2900) were measured at three time points (9-months, 2 years, and 4 years of age). Father, mother, and child factors were examined in relation to father caregiving and play. Latent change score models indicated that fathers engaged in more caregiving and play behaviors and increased at a faster rate when they more strongly identified with their role as a father. Fathers engaged in more caregiving when mothers reported higher depressive symptoms and increased in play more slowly when marital conflict was higher. In addition, a mother depressive symptoms X marital conflict interaction emerged indicating that fathers differed in their levels of caregiving depending on mothers’ report of depressive symptoms but only when marital conflict was low. Fathers also increased in caregiving at a faster rate with girls than boys. A comprehensive framework for examining resident father involvement is presented.

Keywords: fathers, father involvement, marital conflict, depressive symptoms, child temperament

While the effect of parental involvement on child development has been well researched with mothers, in recent decades, focus on the involvement of fathers in the family has increased substantially (Pleck, 2010). Research has indicated that the infant-father relationship is not simply an imitation of the infant-mother relationship, but develops differently (Planalp & Braungart-Rieker, 2013; Braungart-Rieker, Garwood, Powers, & Wang, 2001) and has positive outcomes on child emotional, cognitive, and academic development (Pleck, 2010). Therefore, it is important to examine fathers and their role in the family system.

Systems theories such as Family Systems Theory (Cox & Paley, 1997) or Bioecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1995) posit that within a family, members are inherently dependent on one another, each influencing the other and the system as a whole. These perspectives have been used as a framework for developmental research for many years, and provide substantial motivation from which to include fathers in studies of family relations. It is possible however, that parent, child, or family-wide factors have differing effects on each other and on the family system. For example, conflict within the marital relationship may carry over into parent-child interactions (Cummings, Goeke-Morey & Raymond, 2004), and child characteristics such as temperament may also affect fathers more so than mothers (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Therefore, the current study looks at parent, child, and family-wide contextual factors independently to examine the unique contributions that each may have on father involvement; then we examine a full model incorporating parent and child factors to determine which may be more robust in their influence on father involvement with their children.

We draw from Belsky’s (1984) process model of parenting to determine which characteristics may influence father involvement. Belsky’s (1984) three-factor model asserts that parenting is affected by three characteristics: (1) parent personality and psychological resources, (2) contextual resources for stress and support, and (3) individual child characteristics. For the purposes of this study, we examine fathers’ beliefs in his role as a parent and father depressive symptoms as father characteristics; mother depressive symptoms, mother involvement and the level of conflict in the marital relationship as contextual or partner support characteristics, and finally child temperament and gender as child characteristics in relation to fathering behaviors.

Additionally, father engagement is often studied by examining overall amounts of time or involvement in which a father engages with his child. Palkovitz (1997), however, suggests that caregiving and play activities are qualitatively different aspects of fathering, and it is important to examine them separately. In fact, fathers typically engage in more play activities with their infants and young children than caregiving activities (Lamb, Chuang, & Hwang, 2004; Mehall, Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Gaertner, 2009). Therefore, the current study delineates between these two involvement constructs to determine the degree to which factors related to each are similar.

It is also possible that the role of the father in the family, and therefore with his infant, changes over time. Previous research has found that fathers increase in the number of play and caregiving activities they engage in with infants from three to 20 months (Planalp, Braungart-Rieker, Lickenbrock & Zentall, 2013). Alternatively, the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2000) found that fathers’ responsibility in caregiving was relatively stable from six to 36 months; Lamb and colleagues (2004) found decreases in the amount of time fathers spend with their children from one to seven years of age. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of longitudinal research examining fathering behaviors so possible reasons for these differences are unclear. Many studies look at father involvement over two time points (e.g., Mehall et al., 2009; Volling & Belsky, 1991) or concurrently (e.g., Bronte-Tinkew, Moore, Matthews, & Carrano, 2007; Cabrera et al., 2011), but to our knowledge, only the aforementioned three studies have examined father involvement across multiple time points (Lamb et al., 2004; NICHD 2000; Planalp et al., 2013). The current study adds to the literature by looking at father caregiving and play not only across three waves of measurement, but we also use advanced statistical methods to assess nonlinear change in father involvement across different developmental periods.

In addition, research on determinants of father involvement has found that many factors affect the types and amount of involvement with which fathers engage with their children. Therefore, we examine multiple determinants (parent, child, and contextual family-wide factors) to gain a better understanding of how fathers interact with their children and what factors may influence different types of father engagement over time.

Factors Influencing Father Involvement

Fathering Role Identification

Fathers’ beliefs about their role relationships (that of father vs. husband vs. financial provider) direct his behaviors, and in particular, father-infant interactions (Fox & Bruce, 2001). For example, if a father believes that his sense of self is determined by how well he addresses his role as a father, then we would expect father involvement with his children to be higher. Alternatively, if a father’s sense of self is strengthened by increased time and effort in the workplace, we would expect father involvement to be lower (Fox & Bruce, 2001). Using the same data as the current study, Bronte-Tinkew and colleagues found that father role identity was related to father involvement at 9 months, but this was not assessed longitudinally (Bronte-Tinkew, Carrano, & Guzman, 2006). Therefore, we extend previous research by examining how a father’s beliefs about his own role as a father may relate to changes in father involvement during infancy.

Parent Depression

Although there is evidence that parental depressive symptoms affect parenting behaviors and child outcomes, most research has focused on mothers (Wilson & Durbin, 2010). A recent meta-analysis examining depressive symptoms and fathering behaviors indicated that there was a small, though significant association between father depressive symptoms and decreased positive/increased negative fathering (Wilson & Durbin, 2010). Father depressive symptoms have been found to be directly related to fathering during infancy, such that fathers who reported more depressive symptoms engaged in fewer father-child activities (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007; Paulson, Dauber, & Leiferman, 2011). There is also evidence to suggest that paternal depressive symptoms may differentially relate to father caregiving and play behaviors. Roggman and colleagues (1999) found that fathers who reported more depressive symptoms were less involved in activities with their 14-month old infants, but not necessarily less involved in caregiving. It is possible that psychological dysfunction does not affect those parenting behaviors which are considered necessary for the infant (i.e., direct caregiving), but only those that are thought to be more optional (i.e., play activities, reading books).

Furthermore, family systems theory suggests that parent psychopathology may affect the parent-parent relationship as well as the parent-infant relationship. Bronte-Tinkew and colleagues (2007) found that father depression was related to decreased engagement and increased negativity in the marital relationship. In addition, they found that higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms were partially related to increased father engagement (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007). Therefore, the current study included mother and father depressive symptoms, as well as interactions between depressive symptoms and marital conflict, as possible determinants of father involvement in order to take a more comprehensive look at parental psychopathology and its impact on fathering.

Mother Involvement

Studies examining determinants of father involvement have often studied father involvement in isolation and not included mother involvement in analyses (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). This is curious given that the father-child dyad is not an isolated unit and mothers may impact the amount of time that fathers spend with their children. One study that did assess this association over time used a sample of adolescent children, not infants, and found that mother involvement predicted father involvement but the reverse was not true (Pleck & Hofferth, 2008). In addition, though mothers interact with their infants more than do fathers, levels of parent involvement within families are positively related to one another (Planalp et al., 2013; Pleck & Hofferth, 2008). Thus, it is possible that fathers base their own levels of involvement on what their spouse is doing (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). If this is the case, we would expect fathers’ levels of involvement to be positively related to mothers’ levels. Alternatively, fathers may compensate for a less involved mother, or not feel the need to engage when the mother is more involved, leading to a negative association between mother and father involvement.

The Marital Relationship

Family systems theory incorporates multiple relationships in the study of family dynamics. In the study of child development, not only is it important to assess parent-infant interactions, but parent-parent interactions as well, and possible indirect pathways through which the family system may operate. Volling and Belsky (1991) found that a negative marital relationship (higher in conflict and ambivalence) related to poorer father-infant interactions at 9 months. Similarly, Easterbrooks, Raskin, and McBrian (2014) found that mothers of infants who reported more marital conflict also had partners who were less involved. Interestingly, Mehall and colleagues (2009) did not find an association between concurrent marital satisfaction and father involvement, yet marital satisfaction at 7 months predicted father involvement at 14 months. Therefore, the current study’s longitudinal examination of marital conflict predicting father involvement over time adds to existing literature on how the parent relationship may relate to parent-infant interactions.

Child Temperament

Research on fathering suggests that compared to mother involvement, father involvement and father-child interactions are more affected by child characteristics, such as temperament (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Temperament refers to biologically based individual differences in reactivity and regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Previous research has found that fathers tend to engage more with temperamentally easy infants (Brown, McBride, Bost, & Shin, 2011) and are also less responsive to infants higher in difficult temperament (Volling & Belsky, 1991). Taken together, this line of work relating infant temperament to father involvement has found that fathers engage less when the infant is challenging and more when the infant is easier. It is possible that as traditionally secondary caregivers, fathers have a choice whether to engage with a temperamentally difficult infant or not. It is also possible that interactions between an infant’s temperament and other familial characteristics interact to affect parenting behaviors. For example, fathers exhibit a higher quality of coparenting with temperamentally challenging infants when marital quality is higher (Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, Brown, & Sokolowski, 2007). Additionally, Du Rocher Schudlich, White, Fleischhauer, and Fitzgerald (2011) observed mothers, fathers, and their infants in a laboratory conflict paradigm and found that infants showed heightened negative responses, such as sadness, frustration, and dysregulation in response to parental conflict. It is possible that father involvement with infants may be moderated by the infant’s response to conflict. Thus, in addition to possible direct effects of temperament and marital conflict, the current study examined the interaction between infant temperament and marital conflict within the family system in relation to father involvement.

Child Gender

Research examining infant gender and father involvement is mixed. Some research has found that fathers engage more with young boys (Manlove & Vernon-Feagans, 2002) and adolescent boys than girls (Pleck & Hofferth, 2008). Research also suggests that fathers interact differently with sons and daughters of varying temperaments. Specifically, Frodi and colleagues (1982) found that fathers were more involved with temperamentally easy infant daughters and difficult infant sons, whereas McBride et al. (2002) that fathers engaged less with girls than boys who were rated low in sociability. Therefore, the current study explored the direct role infant gender may have on father involvement, as well as a gender X temperament moderating pathway, though no directional hypotheses were proposed.

Socio-demographic Factors

Previous research has found that Latino and African American fathers engage in more caregiving and play behaviors than Caucasian fathers (Cabrera et al., 2011), and that biological fathers engage more with children than nonbiological fathers (Hofferth, 2003). In addition, fathers who are employed may spend less time with their children (Cabrera et al., 2011; Hofferth & Anderson, 2003; NICHD 2000) and mother employment has been shown to be related to levels of father involvement, such that fathers are more involved in childcare when mothers work more hours (NICHD, 2000; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004) Fathers’ level of education has also been shown to predict higher levels of verbal stimulation, one component of father involvement (Cabrera et al., 2011). Thus, as many of these socio-demographic factors have been associated with fathering using the same data as the current study (Cabrera et al., 2011), we controlled for minority status and SES (a composite variable including income, mother and father education, and mother and father employment status), and mother and father working hours in its examination of the socioemotional processes that may differentially determine father caregiving and play trajectories.

The Current Study

We examined determinants of father caregiving and play during early childhood in order to examine direct father involvement with children. Previous research has found associations between each of the factors tested in the current study and father involvement. However, in order to determine which factors at play within the family have a more robust effect on fathering, we take a systems wide approach and examine determinants of fathering in a stepwise manner. Specifically, the current study used data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort to look at father factors (fathers’ role identification, father depressive symptoms), mother factors (mother depressive symptoms, marital conflict, mother involvement), and child factors (child temperament and gender) in relation to levels and trajectories of father involvement in caregiving and play. First, we examine father, mother, and child factors independently, and then test a comprehensive model to ascertain which predictors are more robust in their relation to father involvement within the family system. Furthermore, family systems theory presumes that multiple factors within the family may interact to affect parenting, so we also examine several interactions in relation to father caregiving and play (depressive symptoms X marital conflict, temperament X marital conflict, gender X marital conflict, and temperament X gender).

Method

Participants

Data were collected as part of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), a nationally representative dataset collected by the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Approximately 10,700 children born in 2001 were followed through kindergarten in order to enhance our understanding of early childhood development and experiences. Assessments were conducted when children were approximately 9-months old (T1), 2 years (T2), 4 years (T3), and at kindergarten entry (5 or 6 years; T4 or T5). Data from the first three visits are included in the current study, as fathers did not report on their own or child behaviors at T4 or T5.

At each wave of data collection, parent interviews were conducted using a computer assisted parent interview form (Parent CAPI), and resident father questionnaires (RFQ) were completed in households where fathers were cohabitating with mothers. Hofferth and Anderson (2003) found that biologically related married cohabitating fathers spend on average 5 more hours per week engaging with their children compared to non-biological fathers. Children with non-biological resident fathers (stepfather or mother’s partner) or biological nonresident fathers may spend additional time with their biological father outside the home, which was not captured in the ECLS-B data collection, thus we looked at only resident biological fathers in analyses. In addition, as the research questions of interest pertain to fathers’ direct engagement with children, and in order to generalize our findings to a larger population, only those respondents who completed questionnaires and were biological, resident parents at each wave were included in analyses. Additionally, the ECLS-B oversampled twins, and in order to reduce shared method variance, twins were excluded from analyses. This resulted in a sample size of 2,9001 biological mothers and fathers who completed questionnaires at T1, T2, and T3. All further analyses use this subsample of the dataset to examine the study’s hypotheses. Demographics at T1 for the sample used in further analyses can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for the full sample and those used in analyses (resident biological mothers and fathers) as reported at T1.

| Full Sample (N=10,700) | Subsample (N=2,900) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Gender | ||||

| Male | 5450 (51.1%) | 1550 (52.4%) | ||

| Female | 5250 (48.9%) | 1400 (47.6%) | ||

| Child Race | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 4400 (41.4%) | 1500 (52.0%) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1700 (15.9%) | 150 (4.5%) | ||

| Hispanic | 2200 (20.5%) | 500 (16.9%) | ||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1200 (11.3% | 500 (16.0%) | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0 (.4%) | 0 (.2%) | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 300 (2.8%) | 50 (1.9%) | ||

| More than one race | 800 (7.6%) | 250 (8.6%) | ||

| Not ascertained | 0 (.2%) | 0 (.1%) | ||

| Child Age in months | ||||

| Mean (std. dev.) | 10.52 (1.88) | 10.29 (1.69) | ||

|

| ||||

|

Fathers N (%) |

Mothers N (%) |

Fathers N (%) |

Mothers N (%) |

|

|

| ||||

| Resident Parent Status | ||||

| Biological parent | 8300 (77.7%) | 10600 (99%) | 2900 (100%) | 2900 (100%) |

| Adoptive parent | 50 (.1%) | 50 (.2%) | n/a | n/a |

| Step-parent | 50 (.2%) | 0 (0%) | n/a | n/a |

| Other | 100 (1%) | 50 (.1%) | n/a | n/a |

| No resident father | 2250 (20.9%) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Race of Resident Parent | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 4350 (40.9%) | 5000 (45.7%) | 1700 (58.6%) | 1650 (55.7%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 800 (7.7%) | 1700 (16.1%) | 150 (5.1%) | 150 (4.7%) |

| Hispanic | 1500 (14.2%) | 1900 (17.8%) | 400 (14.3%) | 400 (14.5%) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1250 (11.5%) | 1400 (13.0%) | 500 (16.9%) | 550 (19.3%) |

| Pacific Islander | 40 (.4%) | 50 (.5%) | 0 (.2%) | 0 (.2%) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 250 (2.2%) | 400 (3.8%) | 50 (2.2%) | 100 (2.7%) |

| More than one race | 250 (2.1%) | 300 (2.8%) | 100 (2.8%) | 100 (2.8%) |

| Education Level of Resident Parent | ||||

| 8th grade | 450 (4.0%) | 500 (4.7%) | 100 (3.7%) | 100 (3.6%) |

| Some high school | 1000 (8.9%) | 1500 (14.5%) | 100 (6.8%) | 150 (5.6%) |

| High school (or equivalent) | 2050 (19.4%) | 3000 (27.6%) | 500 (17.6%) | 550 (18.9%) |

| VOC/Tech Program | 500 (4.7%) | 500 (3.2%) | 200 (6.6%) | 100 (2.9%) |

| Some college | 1800 (16.8%) | 2500 (23.5%) | 650 (22.5%) | 750 (25.7%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1450 (13.4%) | 1700 (15.8%) | 650 (21.4%) | 750 (25.5%) |

| Graduate school (no degree) | 200 (1.7%) | 200 (1.7%) | 100 (3.1%) | 100 (2.9%) |

| Master’s degree | 650 (6.0%) | 700 (6.4%) | 300 (10.4%) | 350 (11.4%) |

| Doctorate or Professional Degree | 450 (4.2%) | 250 (2.4%) | 250 (7.7%) | 100 (3.5%) |

| Work Status of Resident Parent | ||||

| Not working | 400 (3.7%) | 4400 (41.2%) | 100 (2.9%) | 1250 (42.6%) |

| Looking for work | 350 (3.3%) | 900 (8.3%) | 100 (2.8%) | 100 (3.5%) |

| <35 hours per week | 450 (4.0%) | 1900 (17.6%) | 150 (4.6%) | 600 (21.0%) |

| 35+ hours per week | 7200 (67.1%) | 3500 (32.4%) | 2600 (89.6%) | 950 (32.7%) |

| Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | Mean (s.d.) | |

| Parent Age in years | 32.11 (6.94) | 28.50 (6.55) | 32.90 (6.40) | 30.38 (5.63) |

| Average Household Income | $30,001 – $35,000 | $50,001 – $75,000 | ||

Note: Due to data requirements from the National Center for Education Statistics, and in order to protect participant identity, all sample numbers are rounded to the nearest n=50. Percentages are not rounded and reflect actual percentage within the sample.

Measures

Parental Involvement

Mothers and fathers were asked about the frequency they engaged in several caregiving and play activities with their child. For mother and father play variables, parents were asked to respond to a set of questions with the stem “In a typical week, how often do you do the following things with your child?” with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (every day) on a Likert scale. The three items at each time point were “tell stories,” “read to the child,” and “sing songs with the child.” Fathers responded to questions relating to play at T1, T2, and T3, whereas mothers only responded to play questions at T1. Internal consistency for father play at T1, T2, and T3 resulted in Cronbach’s alphas of .63, .66, and .66 respectively. The three items used to measure mother play at T1 mirrored those used for father play, with internal consistency of .60.

For caregiving at T1, T2, and T3, fathers were asked to respond to a set of questions with the stem “In the past month, how often did you do the following things with your child?” with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (more than once a day) on a 6-point Likert scale. Three items (“wash child,” “dress child,” and “put child to sleep”) were the same at each time point. Other items, however, changed to reflect the child’s developmentally appropriate needs. At T1, additional items included “change your child’s diaper” and “prepare food.” At T2, additional items were “change diaper/help toilet train,” “prepare food,” and “help brush teeth.” At T3, the additional item was “help brush teeth.” Internal consistency for T1, T2, and T3 father caregiving scales resulted in Cronbach’s alphas of .84, .84, and .78 respectively. Mothers were not asked about caregiving at T1, thus a mother caregiving variable is not included in analyses.

Father Role Identification

Fathers’ role identification was assessed using five questions adapted from the Role of the Father Questionnaire (Palkovitz, 1984). Fathers were asked to respond on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree whether they agreed with several questions. Sample items include “It is essential for the child’s well-being that fathers spend time playing with their children,” “A father should be as heavily involved as the mother in the care of the child,” and “All things considered, fatherhood is a highly rewarding experience.” Responses were reverse scored so that higher scores indicated a father who endorsed fatherhood as more rewarding. Reliability for this composite was α = .59.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms for mothers and fathers at T1 were assessed using a modified version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Mothers and fathers are asked to respond to a question stem “How often during the past week have you felt these ways?” with sample response items “bothered by things that usually don’t bother you” and “That you could not shake off the blues, even with help from your family and friends?” Responses ranged from 0 (rarely or never) to 3 (most or all days). Internal consistency of the scale was .86 mothers and .84 for fathers at T1.

Marital Conflict

Marital conflict for mothers and fathers at T1 was assessed using 10 questions in which respondents were asked to respond on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often) about arguments with their spouse. Sample items include “chores and responsibilities,” “money,” and “leisure time.” Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alphas (α=.77 for mothers; α=.80 for fathers). The association between mothers and fathers reports of marital conflict was significant (r=.41, p<.001), so an average of mother and father marital conflict was used in further analyses.

Child Difficult Temperament

The ECLS-B used a subset of questions from the Infant/Toddler Symptom Checklist (ITSC; DeGangi, Poisson, Sickel, & Wiener, 1995) to assess behavior problems. A difficult temperament factor was created using seven age relevant ITSC questions at T1. Sample items include “Is frequently irritable or fussy,” and “Goes easily from a whimper to an intense cry,” with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (most times) on a 4-point Likert scale. Internal consistency of the difficult temperament scale at T1 was .60.

Covariates

Socio-economic Status

A composite socio-economic status variable was computed for each family. Mother and father education, employment, and income were included in the variable. Mothers and fathers reported on their own education and employment, and mothers reported on household income. Descriptive statistics for these variables are in Table 1. The ECLS-B then reports an SES composite score using each of these variables as a continuous variable z-score, ranging from −2.10 to 2.25 with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one (ECLS-B 9-month User’s Manual).

Mother and Father Working Hours

Parents’ responded to one question “How many hours a week do you work?” with four response choices: 0) not in the workforce, 1) looking for work, 2) work less than 35 hours per week, 3) work more than 35 hours per week.

Siblings in the Household

In addition, because fathers’ involvement with one child may depend upon the number of children in the household, we entered number of siblings at each time point as a covariate. At T1, 1190 of the infants in the current study were first-born children, 1070 were second born children, and the remainder had two (n=460) to seven (n=4) siblings.

Results

Results for the current study are presented in several sections. First, caregiving and play items were examined for continuity over time using methods to test for factorial invariance. Second, latent difference score models for caregiving and play were examined for model fit to determine which model of change (e.g., no change, linear, nonlinear) best explained the data in the current study. Next, we examined three models of father involvement including one set of predictor factors (father, mother, and child) to examine the unique effects of each on father involvement. Finally, we looked at a comprehensive final model in order to assess which predictors were most robust in predicting father involvement. We assessed patterns of missing data and found that data on the outcome variables of caregiving and play were missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: X2(5) = 1.57, p=.90). The largest proportion of missing data came from child temperament ratings where 18.4% of data were missing, and mother ratings of depressive symptoms and conflict, with 7.7% and 7.1% missing, respectively. Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is the most appropriate method with which to estimate and examine missing data (Enders, 2010), thus all of our analyses used MPlus version 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2011) and MLE to account for missing data and appropriately compare model fit.

Factorial Invariance Over Time for Caregiving and Play

In order to conclude that the caregiving and play factors were comparable over time even if items changed, models assessing factorial invariance were compared (see Widaman, Ferrer, & Conger, 2010 for a full description of factorial invariance). Results showed evidence for weak invariance for both caregiving and play, indicating that these constructs were meaningfully similar across time even though the items change in a developmentally appropriate manner with infant age. Factor scores determined from the weak invariance models were used in further analyses as composite caregiving and play scores. Unweighted means, standard deviations, and correlations between caregiving and play at each time point are presented in Table 2, in addition to other study variables. Because we have support for factorial invariance, longitudinal analyses assessing changes in caregiving and play factor scores can be appropriately conducted.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for father caregiving and play behaviors and determinants of father involvement

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Father Care T1 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Father Care T2 | .70** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Father Care T3 | 54*** | .58*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 4. Father Play T1 | .29*** | .30*** | .26*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 5. Father Play T2 | .28*** | .37*** | .30*** | .73*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 6. Father Play T3 | .26*** | .32*** | .39*** | .65*** | .73*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 7. Father Role Ident | .21*** | .20*** | .16*** | .22*** | .21*** | .20*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 8. Father Dep. | −.02 | −.01 | .05* | −.05** | −.04* | −.04* | −.05* | 1.00 | ||||||

| 9. Mother Dep. | .04* | .04 | .03 | −.05** | −.06** | −.05* | −.01 | .22*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 10. Father MC | −.03 | −.06** | −.04 | −.11** | −.10*** | −.09*** | −.15*** | .27*** | .18*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 11. Mother MC | −.02 | −.02 | −.04* | −.07** | −.07*** | −.08*** | −.06** | .16*** | .33*** | .41*** | 1.00 | |||

| 12. Mother Play T1 | .04* | .04* | .05*** | .30*** | .28*** | .21*** | .13*** | −.01 | .06** | −.07*** | −.08*** | 1.00 | ||

| 13. Infant Gender | .07*** | −.08*** | −.11*** | .05* | .06** | .03 | .01 | −.03 | −.03 | −.01 | .02 | .05* | 1.00 | |

| 14. Infant Diff. Temp. | −.04* | .01 | .02 | −.03 | −.05** | −.04 | −.04 | .09*** | .16*** | .13*** | .15*** | −.05* | −.04 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Mean | .03 | 2.21 | 2.13 | 1.67 | 1.93 | 1.81 | 3.54 | 3.31 | 4.17 | .84 | .75 | 2.67 | .48 | 1.15 |

| Standard Deviation | .49 | .48 | .50 | .59 | .62 | .58 | .32 | 4.18 | 4.60 | .50 | .46 | .96 | .50 | .55 |

| Skewness | −.96 | −.74 | −.69 | .23 | .24 | .30 | −.65 | 2.09 | 1.88 | .56 | .73 | −.35 | .10 | .10 |

| Kurtosis | .96 | .91 | .66 | −.17 | −.35 | −.07 | .01 | 6.02 | 4.94 | .52 | 1.20 | −.59 | −1.99 | −.37 |

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Diff. Temp = Infant Difficult Temperament, Ident = Identification, Dep = Depressive symptoms, MC = Marital Conflict. Infant gender is coded such that males = 0, females = 1.

Latent Difference Score Models for Caregiving and Play

One way to measure change is to use Latent Difference Score Models (LDS; McArdle & Nesselroade, 2002). LDS models examine dynamic longitudinal change and incorporate determinants of such change as well as account for nonlinear change. LDS models integrate trajectory analysis with the ability to examine cross lagged determinants of interrelated change (McArdle & Hamagami, 2001). This is particularly important because more common methods of analyzing data with only three time points of analysis, such as simple linear modeling, test no change and linear trajectories. However, it is possible that as children get older, fathers’ interactions with them change in a nonlinear manner, especially from infancy to toddlerhood. Indeed, the factor means of caregiving and play in the current study (Table 2) indicate that there may be a non-linear change occurring.

In LDS modeling, latent “true” scores are modeled from observed scores. In this way, the latent “true” score is assumed to reflect a score without measurement error or residual variance. From these latent true scores, a latent difference score is determined based on the latent variable both concurrently (at time t) and from the previous time point (t−1). Thus, the difference score can be understood as the true difference between latent true scores, free of measurement error. The dual change score model is an additive LDS model in which change over time in a construct is a result of scores at each time point plus the effect of the previous time point’s score.

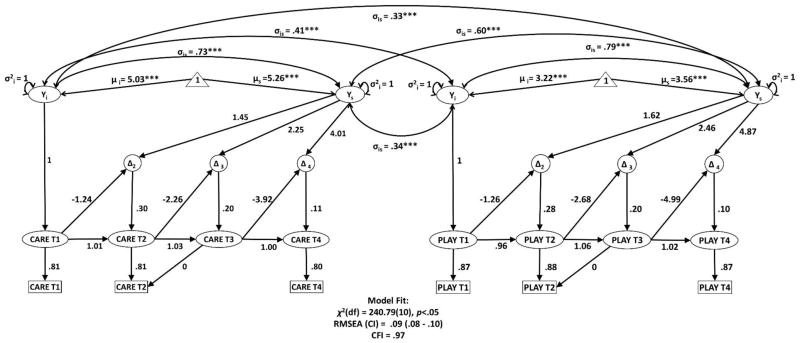

A latent dual change score model examining caregiving and play without predictors was first examined to determine that this model did, in fact, fit our data for caregiving and play2. Model fit parameters are in Figure 1, along with intercept and slope estimates for caregiving and play over time. The intercept estimates represent initial levels of caregiving and play, and slope estimates represent the average yearly change in involvement. As can be seen by the significant positive estimates for intercepts and slopes when no predictors are included in the model, fathers increase in both caregiving (β = 5.26, p<.001) and play (β = 3.56, p<.01) over time.

Figure 1.

Dual Change Latent Difference Score Models for Caregiving and Play with No Determinants: Model Fit Parameters and Standardized Path Estimates

The current study proposed several hypotheses with T1 determinants relating to initial level and change in caregiving and play, thus a second set of dual change score models including time invariant determinants of intercepts and slopes of involvement were also tested. In order to examine the unique effects father, mother, and child factors may have on fathering, we first ran three separate models predicting father involvement (see Table 3). Father role identification at T1 consistently predicted initial levels and slopes of father caregiving and play, such that when father role identification is higher, fathers engage in more caregiving and play with their infants, but also increase in such behaviors at a faster rate. Father depressive symptoms were unrelated to caregiving and play whereas mother depressive symptoms were related to father caregiving but not play behaviors. Specifically, fathers engaged in more caregiving behaviors when mothers reported higher levels of depressive behaviors at T1 and also increased in caregiving at a faster rate. Marital conflict was also consistently related to caregiving and play, such that when parents reported higher marital conflict, fathers were less involved initially and also increased in involvement at a slower rate. In addition, mother level of play at T1 related to concurrent levels of caregiving and play, as well as fathers’ increased play over time. In terms of child factors, fathers engaged in less caregiving with girls than boys and showed a slower increase in caregiving over time with girls vs. boys; they also showed more initial play with girls than boys. In addition, fathers engaged in less initial caregiving when mothers reported more difficult child temperament, and increased in play at a slower rate with the same infants.

Table 3.

Standardized Estimates for Determinants of Caregiving and Play with predictors included only by determining factor

| Model | Father Factors | Mother and Marital Factors | Child Factors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | ||||||||||||

| χ2(df) | 316.43 (28), p<.05 | 291.66 (30), p<.05 | 255.80, (28) p<.05 | |||||||||

| RMSEA (C.I.) | .06 (.06 – .07) | .06 (.05 – .06) | .06 (.05 – .07) | |||||||||

| CFI | .97 | .97 | .97 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Caregiving | Play | Caregiving | Play | Caregiving | Play | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Int. | Slope | Int. | Slope | Int. | Slope | Int. | Slope | Int. | Slope | Int. | Slope | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | |

| Father Role Ident. | .23*** (.02) | .16*** (.02) | .21*** (.02) | .18*** (.02) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Father Dep. | −.01 (.02) | −.04 (.03) | −.03 (.02) | −.01 (.02) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mother Dep. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | .09*** (.02) | .07** (.03) | −.02 (.02) | .01 (.02) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mother Play | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | .05* (.02) | .03 (.03) | .30*** (.02) | .15*** (.02) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Marital Conflict | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | −.09*** (.02) | −.09** (.03) | −.08*** (.02) | −.10*** (.02) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Infant Gender | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | −.09 *** (.02) | −.13*** (.03) | .06** (.02) | .03 (.02) |

| Infant Temp. | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | −.05* (.02) | .04 (.03) | −.04 (.02) | −.05* (.02) |

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Temp = Infant Temperament, Ident. = Identification, Dep = Depressive symptoms, MC = Marital Conflict. Infant Gender is coded male = 0, female = 1. Mother and father working hours at T1, SES, father minority status, and the number of siblings in the household at each time point were included in each analysis as covariates.

A final model including all predictors as well as well as five two-way interactions (temperament X gender, temperament X marital conflict, gender X marital conflict, father depressive symptoms X marital conflict, and mother depressive symptoms X marital conflict) was tested to see which of these factors may prove to have robust effects on father involvement. Results for model fit and estimates for determinants of involvement are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Standardized Estimates for Determinants of Caregiving and Play Full Model

| Model | Full Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | ||||

| χ2(df) | 257.77 (46), p<.05 | |||

| RMSEA (C.I.) | .05 (.04 – .05) | |||

| CFI | .97 | |||

|

| ||||

| Caregiving | Play | |||

|

| ||||

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

|

| ||||

| Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | Est (s.e.) | |

| Father Role Ident. | .25*** (.03) | .18*** (.03) | .20*** (.02) | .15*** (.03) |

| Father Dep. | −.07 (.06) | −.01 (.06) | −.06 (.05) | −.09 (.06) |

| Mother Dep. | .25*** (.06) | .11 (.07) | −.001 (.06) | .09 (.06) |

| Marital Conflict | −.02 (.06) | −.09 (.07) | −.09 (.06) | −.14* (.06) |

| Mother Play | .05 (.03) | .03 (.03) | .26*** (.02) | .15*** (.03) |

| Infant Gender | −.03 (.07) | −.17* (.08) | .06 (.07) | −.04 (.07) |

| Infant Temp. | −.09 (.06) | .02 (.07) | −.08 (.06) | −.10 (.06) |

| Father Dep X MC | .09 (.06) | −.01 (.07) | .04 (.06) | .10 (.06) |

| Mother Dep X MC | −.25** (.07) | −.07 (.08) | −.06 (.07) | −.10 (.07) |

| Temp X MC | .10 (.08) | .06 (.09) | .10 (.08) | .08 (.08) |

| Gender X MC | −.05 (.06) | .02 (.07) | −.05 (.06) | .02 (.06) |

| Gender X Temp | −.03 (.06) | .01 (.07) | .04 (.06) | .04 (.06) |

|

| ||||

| Correlations between latent intercepts and slopes | ||||

|

| ||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

| 1. Caregiving Intercept | 1.00 | |||

| 2. Caregiving Slope | .71*** | 1.00 | ||

| 3. Play Intercept | .40*** | .29*** | 1.00 | |

| 4. Play Slope | .35*** | .60*** | .74*** | 1.00 |

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Temp = Infant Temperament, Ident. = Identification, Dep = Depressive symptoms, MC = Marital Conflict. Mother working hours at T1, SES, father minority status, and the number of siblings in the household at each time point were included in each analysis as covariates.

Several predictors which had previously emerged as significant in the simple one-factor (father, mother, or child) models fell away, yet those remaining indicated that some predictors may have a more reliable influence on father involvement. Similar to the one factor models, father role identification was related to both initial levels and changes in father caregiving and play, such that fathers whose role identification was more strongly related to their sense of being a father engaged in more caregiving and play initially, as well as had a steeper increase over time. In addition, fathers engaged in more caregiving when mothers reported higher depressive symptoms, and increased in play at a slower rate when marital conflict was higher. A significant mother depressive symptoms X marital conflict interaction also emerged, indicating that fathers engaged in the sale levels of caregiving regardless of mother reports of depressive symptoms when marital conflict was high; however, when marital conflict was low, fathers engaged in more caregiving when mother depressive symptoms were high and less caregiving when mother depressive symptoms were low. Finally, mother and father play behaviors were also related, such that fathers engaged in higher initial levels of play behaviors, and increased in play behaviors at a faster rate when mothers played with their infants more as well. In terms of child factors, a direct effect for infant gender was found such that fathers increased in caregiving behaviors at a slower rate with girls than boys, but no significant effects for infant temperament emerged.

Discussion

The current study examined patterns and determinants of father caregiving and play behaviors over time. Previous research has found that father involvement is determined by multiple influences, specifically marital conflict and parental depressive symptoms (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007), and child factors such as gender (Manlove & Vernon-Feagans, 2002) and temperament (McBride & Mills, 1993). By using a large dataset with multiple predictors we were able to test a series of father involvement models indicating which factors may be more robust in their relation to fathers’ caregiving and play behaviors.

Additionally, fathers’ levels of caregiving and play increased over time. This is similar to previous research that has found caregiving and play to increase from 3 to 20 months (Planalp et al., 2013), but differs from other large scale survey data (NICHD, 2000). This could be due to differences in measurement of father involvement. In the current study, we would expect certain play behaviors to increase, such as story-telling and reading books as the child develops a greater cognitive capacity to engage in such behaviors. Fathers increased in caregiving over time because the items assessing caregiving also changed in a developmentally appropriate manner as the child got older. For example, caregiving at nine months was assessed with a question about changing diapers, whereas at four years of age, it included a question toilet training. It is possible that fathers, who were less involved in changing diapers, helped with toilet training and dressing more as the child got older. Thus, while these results diverge from some previous studies on father involvement (e.g. Lamb et al., 2004), they support the idea that fathering changes over time in response to child needs and developmental stages.

Factors Influencing Father Involvement

Results supported the hypothesis that father caregiving and play were differentially related to various empirically supported determinants of involvement, though there were some similarities between the two. Similar to previous research with the ECLS-B, how a father defined his role in the family impacted how he engaged with his child (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2006). A father whose identity in his role as a father was stronger exhibited more caregiving and play behaviors with his child. The current study, however, yielded new and interesting information on the prediction of trajectories over time such that fathers whose identity in his role as a father was stronger showed increases in caregiving and play over time at a faster rate. It is not unexpected that father role identity was related to involvement as they were both self-reported and it reflects a father’s belief that being involved in childrearing is more important than financial support or other provisions. It is interesting, however, that role identity was the only factor included in the current study which consistently related to fathering, indicating that perhaps whether the father finds satisfaction in his role as a parent is particularly salient when fathers are deciding how to spend their time with their children.

Mother characteristics also played a role in father caregiving. Mother depressive symptoms were related to levels and changes in father caregiving in models examining mother and marital factors, and the association between mother depressive symptoms and caregiving emerged as significant in the full model, indicating that depressive symptoms are a robust predictor of father’s level of caregiving but not change over time. An abundance of previous research links mother depression to negative parenting (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Mothers who exhibit depressive symptoms may reveal negative parenting by being less involved. It is possible that fathers engage in more caregiving with these infants in order to compensate for the lower amounts of caregiving from mothers. Interestingly, mother depressive symptoms were unrelated to father play behaviors. Fathers may compensate for a mother who exhibits depressive symptoms by increasing those behaviors necessary for infant development, such as feeding and diaper changing, but not necessarily engage in more play behaviors.

When examined as a sole predictor, marital conflict predicted initial levels and changes in both caregiving and play. However, once included in the full model we found that marital conflict was related to a slower increase in father play behaviors. It is possible that, analogous to mother depressive symptoms affecting more primary behaviors such as father caregiving, marital conflict affects the more secondary behaviors of father play. Fathers who are less happy in their marriage may withdraw from their role as a parent (Cummings et al., 2004). Alternatively, mothers may act as a gatekeeper, preventing fathers from engaging with their children in play contexts (Schoppe-Sullivan, Brown, Cannon, Mangelsdorf, & Sokolowski, 2008).

Mehall et al. (2009) found that higher marital satisfaction at 7 months of age predicted increased father involvement with 14-month old infants, though not concurrent involvement at 7 months. Planalp and colleagues (2013) also found that increased marital satisfaction related to increased play over time. Though Mehall et al. and Planalp et al. measured marital positivity and not conflict, our findings are similar in that fathers’ marital quality predicts later involvement. Admittedly, the current study examined only partners who were cohabitating for the three time points of interest. Those couples who separated or were not cohabitating were excluded from analyses, possibly limiting the effect conflict would have on parenting. Thus, future work would benefit from examining conflict in relation to involvement in higher risk families.

Mothers’ levels of play behaviors were also consistently related to fathers’ play behaviors. This is similar to previous research with both infants (Planalp et al., 2013) and adolescents (Pleck & Hofferth, 2008). Interestingly, mother play was not related to father caregiving, though the reliability estimate of mother play as measured in this study was relatively low. It could be that our assessment of mother play did not accurately portray the association between mother and father involvement behaviors because it was not able to reliably gauge maternal behaviors. Nonetheless, if fathers model their own involvement behaviors from their spouses’ behaviors, levels of mother play would be related to father play and unrelated to father caregiving, as found in the current study. Unfortunately, the current study was not able to assess motivation in father involvement, nor were we able to examine mother caregiving in relation to father caregiving; thus, future studies would benefit by including a comprehensive examination of the role of mother involvement on father involvement.

Interestingly, the current study did not find that father depressive symptoms were related to father involvement in caregiving or play. Previous research has found that father depressive symptoms are related to lower father investment in and lower engagement with children (e.g. Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007; Paulson et al., 2011). Levels of depressive symptomology in the current study were fairly low, possibly obscuring the effect depressive symptoms may have on father caregiving or father play. In addition, due to limitations in the ECLS-B design, father depressive symptoms were measured only at T1. Therefore, examining changes in depressive symptoms relating to changes in involvement were not possible.

Previous research has also found that infant temperament may affect the level or quality of father involvement. For example, McBride and colleagues (2002) found that fathers engaged with daughters higher in sociability and sons with an easier temperament; Manlove and Vernon-Feagans (2002) found that fathers engaged more with sons lower in negative temperament, and Brown et al. (2011) found that fathers’ time spent with children depended on child temperament and their own availability. However, these studies did not include father role identity, which we found to be more salient in predicting father involvement. Specifically, we found that temperament was only associated with father caregiving and play in initial models that excluded parenting factors, such as role identity. In the full model, infant temperament was unrelated to father involvement though gender still impacted father caregiving. Fathers engaged in less initial caregiving and increased in caregiving at a slower rate with girls than boys, possibly because fathers may be more comfortable caring for boys than girls, as they have more experience being a male themselves. Since father role identity emerged as such a robust predictor of fathering and we did not find temperament differences, it is possible that previous findings regarding temperament would not be as compelling if role identity was included.

There were limitations in our measurement of temperament, however, so that it may not accurately reflect the relation between infant temperament and fathering. Specifically, there was significant missingness in mother reports of infant temperament, and the reliability of the construct was fairly low. These may both affect how temperament, as measured in the current study, relates to father involvement. Additionally, the current study was not able to assess more positive aspects of infant temperament, such as sociability or surgency. Using a smaller community sample, Planalp and colleagues (2013) found that infant surgency related to mothers’ but not fathers’ levels and changes in caregiving and play behaviors. It is possible that surgency or other positive temperamental dimensions may relate to father involvement in a larger sample. Future research examining father involvement should include a comprehensive measure of infant temperament in order to examine how both positive and negative aspects of temperament may affect fathering.

Conclusions, Limitations and Future Directions

Results highlight that father involvement within the family is influenced by multiple determinants. Comprehensive studies incorporating many characteristics of the family are needed to fully capture the effects one variable, for example marital conflict, may have on the family system and father involvement. Still, we did not include many factors which have been found to be associated with fathering, such as maternal gatekeeping and co-parenting quality (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2008), positive child temperament (Planalp et al. 2013) or the quality of the parent-child relationship (Caldera, 2007). Nonetheless, we identified several factors which are robust in their prediction of father involvement and may be ideal candidates with which to develop interventions aimed at increasing father engagement in the family.

The current study is also limited by several factors. Notably, we only examined biological resident fathers, thus our findings are only generalizable to this specific population of fathers. We would anticipate factors such as employment and maternal gatekeeping to be particularly salient in the role nonresident fathers have with their children. Future research on father involvement would benefit from a more comprehensive look at nonresident fathers and step (resident, non-biological) fathers.

Second, due to the fact that this study uses secondary data, measures used in the current study are limited by the design of and questionnaire items asked in the ECLS-B interviews. In addition, shared method variance may be a problem as fathers reported on their own involvement, role identity, depressive symptoms and marital conflict. Therefore, significant findings relating to these factors may reflect overlapping rater variance. Despite these limitations, the current study provides support for a theory of resident father involvement which includes differential determinants of caregiving and play behaviors over time. Based on these findings, it is important for future work examining father involvement to distinguish between the constructs of caregiving and play, and also look at distinct predictors of such fathering behaviors within the family system.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the first author was awarded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32MH018931.

Footnotes

Due to data requirements from the National Center for Education Statistics, and in order to protect participant identity, all sample numbers are rounded to the nearest n=25. Percentages are not rounded and reflect actual percentage within the sample.

Note: The authors tested a series of models using MPlus 6.o. First, a simple linear growth model was examined for father involvement but results indicated a poor model fit with a non-positive definite latent variable covariance matrix. The nonlinear change over time indicated that a more complex SEM model may fit the data better. Thus, a series of Latent Difference Score Models (No Change, Proportional Change, Constant Change, Dual Change) were examined. Comparative fit indices indicated that the Dual Change Latent Difference Score Model fit the data best. For more information and complete fit indices, contact the first author.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth M. Planalp, University of Wisconsin—Madison

Julia M. Braungart-Rieker, University of Notre Dame

References

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.2307/1129836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker JM, Garwood MM, Powers BP, Wang X. Parental sensitivity, infant affect, and affect regulation: Predictors of later attachment. Child Development. 2001;72:252–270. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental Ecology Through Space and Time: A Future Perspective. In: Moen P, Elder GH Jr, Luscher K, editors. Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of Human Development. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 619–647. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Carrano J, Guzman L. Resident fathers’ perceptions of their roles and links to involvement with infants. Fathering. 2006;4(3):254–285. 1537-6680.04.254. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Moore KA, Matthews G, Carrano J. Symptoms of major depression in a sample of fathers of infants: Sociodemographic correlates and links to father involvement. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(1):61–99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192513X06293609. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, McBride BA, Bost KK, Shin N. Parental involvement, child temperament, and parents’ work hours: Differential relations for mothers and fathers. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2011;32:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Hofferth SL, Chae S. Patterns and predictors of father–infant engagement across race/ethnic groups. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2011;26(3):365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.01.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldera Y. Paternal involvement and infant–father attachment: A Q-set study. Fathering. 2004;2:191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Raymond J. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 196–121. [Google Scholar]

- DeGangi G, Poisson S, Sickel R, Wiener AS. Infant/Toddler Symptom Checklist: A screening tool for parents. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Du Rocher Schudlich TD, White CR, Fleischhauer EA, Fitzgerald KA. Observed infant reactions during live interparental conflict. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(1):221–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00800.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Raskin M, McBrian SF. Father involvement and toddlers’ behavior regulation: Evidence from a high social risk sample. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers. 2014;12(1):71–93. doi: 10.3149/fth.1201.71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frodi A, Lamb M, Frodi M, Hwang P, Forsstrom B, Corry T. Stability and change in parental attitudes following an infant’s birth into traditional and nontraditional Swedish families. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1982;23:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1982.tb00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Bruce C. Conditional fatherhood: Identity theory and parental investment theory as alternative sources of explanation of fathering. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(2):394–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL. Race/ethnic differences in father involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy? Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(2):185–216. doi: 10.1177/0192513X02250087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Anderson KG. Are all dads equal? Biology versus marriage as a basis for paternal investment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(1):213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JN, Kelley ML. Predictors of father involvement in childcare in dual-earner families with young children. Fathering. 2006;4(1):23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Chuang SS, Hwang CP. Internal reliability, temporal stability, and correlates of individual differences in paternal involvement: A 15-year longitudinal study in Sweden. In: Day RD, Lamb ME, editors. Conceptualizing and measuring father involvement. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lavery D. [November 5, 2013];More Mothers of Young Children in US Workforce. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2012/us-working-mothers-with-children.aspx.

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Mother depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove EE, Vernon-Feagans L. Caring for infant daughters and sons in dual earner households: Mother reports of father involvement in weekday time and tasks. Infant and Child Development. 2002;11:305–320. doi: 10.1002/icd.260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Linear dynamic analyses of incomplete longitudinal data. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. Methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 139–175. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Growth curve analysis in contemporary psychological research. In: Schinka J, Velicer W, editors. Comprehensive handbook of psychology: Vol. 3, Research methods in psychology. New York: Pergamon Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Mills G. A comparison of mother and father involvement with their preschool age children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1993;8:457–477. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80080-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Schoppe SJ, Rane TR. Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:998–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00998.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehall KG, Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Gaertner BM. Examining the relations of infant temperament and couples’ marital adjustment to mother and father involvement: A longitudinal study. Fathering. 2009;7:23–48. doi: 10.3149/fth.0701.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Factors associated with fathers’ caregiving activities and sensitivity with young children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:200–219. doi: 10.1037//D893-3200.14.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R. Parental attitudes and fathers’ interactions with their 5-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20(6):1054–1060. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.20.6.1054. [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R. Reconstructing “involvement”: Expanding conceptualizations of men’s caring in contemporary families. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JF, Dauber SE, Leiferman JA. Parental depression, relationship quality, and nonresident father involvement with their infants. Journal of Family Issues. 2011;32(4):528–549. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0192513X10388733. [Google Scholar]

- Planalp EM, Braungart-Rieker JM. Temperamental precursors of infant attachment with mothers and fathers. Infant Behavior & Development. 2013;36(4):796–808. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.09.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planalp EM, Braungart-Rieker JM, Lickenbrock DM, Zentall SR. Trajectories of parenting during infancy: The role of infant temperament and marital adjustment for mothers and fathers. Infancy. 2013;18:E16–E45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/infa.12021. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. Father involvement: Revised conceptualization and theoretical linkages with child outcomes. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 5. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. pp. 459–485. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Hofferth SL. Mother involvement as an influence on father involvement with early adolescents. Fathering. 2008;6(3):267–286. doi: 10.3149/fth.0603.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH, Masciadrelli B. Father involvement by U.S. residential fathers: Levels, source and consequences. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. pp. 222–271. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roggman LA, Benson B, Boyce L. Fathers with infants: Knowledge and involvement in relation to psychosocial functioning and religion. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1999;20(3):257–277. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199923)20:3<257::AID-IMHJ4>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional and personality development. 6. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Brown GL, Sokolowski MS. Goodness-of-fit in family context: Infant temperament, marital quality, and early coparenting behavior. Infant Behavior and Development. 2007;30(1):82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Brown GL, Cannon EA, Mangelsdorf SC, Sokolowski MS. Maternal gatekeeping, coparenting quality, and fathering behavior in families with infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(3):389. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Belsky J. Multiple determinants of father involvement during infancy in dual earner and single earner families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;53:461–474. doi: 10.2307/352912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Ferrer E, Conger RD. Factorial invariance within longitudinal structural equation models: Measuring the same construct across time. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4(1):10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Durbin CE. Effects of father depression on fathers’ parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]