Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Investigation of dietary therapy for diabetes has focused on meal size and composition; examination of the effects of meal sequence on postprandial glucose management is limited. The effects of fish or meat before rice on postprandial glucose excursion, gastric emptying and incretin secretions were investigated.

Methods

The experiment was a single centre, randomised controlled crossover, exploratory trial conducted in an outpatient ward of a private hospital in Osaka, Japan. Patients with type 2 diabetes (n = 12) and healthy volunteers (n = 10), with age 30–75 years, HbA1c 9.0% (75 mmol/mol) or less, and BMI 35 kg/m2 or less, were randomised evenly to two groups by use of stratified randomisation, and subjected to meal sequence tests on three separate mornings; days 1 and 2, rice before fish (RF) or fish before rice (FR) in a crossover fashion; and day 3, meat before rice (MR). Pre- and postprandial levels of glucose, insulin, C-peptide and glucagon as well as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide were evaluated. Gastric emptying rate was determined by 13C-acetate breath test involving measurement of 13CO2 in breath samples collected before and after ingestion of rice steamed with 13C-labelled sodium acetate. Participants, people doing measurements or examinations, and people assessing the outcomes were not blinded to group assignment.

Results

FR and MR in comparison with RF ameliorated postprandial glucose excursion (AUC−15–240 min-glucose: type 2 diabetes, FR 2,326.6 ± 114.7 mmol/l × min, MR 2,257.0 ± 82.3 mmol/l × min, RF 2,475.6 ± 87.2 mmol/l × min [p < 0.05 for FR vs RF and MR vs RF]; healthy, FR 1,419.8 ± 72.3 mmol/l × min, MR 1,389.7 ± 69.4 mmol/l × min, RF 1,483.9 ± 72.8 mmol/l × min) and glucose variability (SD−15–240 min-glucose: type 2 diabetes, FR 1.94 ± 0.22 mmol/l, MR 1.68 ± 0.18 mmol/l, RF 2.77 ± 0.24 mmol/l [p < 0.05 for FR vs RF and MR vs RF]; healthy, FR 0.95 ± 0.21 mmol/l, MR 0.83 ± 0.16 mmol/l, RF 1.18 ± 0.27 mmol/l). FR and MR also enhanced GLP-1 secretion, MR more strongly than FR or RF (AUC−15–240 min-GLP-1: type 2 diabetes, FR 7,123.4 ± 376.3 pmol/l × min, MR 7,743.6 ± 801.4 pmol/l × min, RF 6,189.9 ± 581.3 pmol/l × min [p < 0.05 for FR vs RF and MR vs RF]; healthy, FR 3,977.3 ± 324.6 pmol/l × min, MR 4,897.7 ± 330.7 pmol/l × min, RF 3,747.5 ± 572.6 pmol/l × min [p < 0.05 for MR vs RF and MR vs FR]). FR and MR delayed gastric emptying (Time50%: type 2 diabetes, FR 83.2 ± 7.2 min, MR 82.3 ± 6.4 min, RF 29.8 ± 3.9 min [p < 0.05 for FR vs RF and MR vs RF]; healthy, FR 66.3 ± 5.5 min, MR 74.4 ± 7.6 min, RF 32.4 ± 4.5 min [p < 0.05 for FR vs RF and MR vs RF]), which is associated with amelioration of postprandial glucose excursion (AUC−15–120 min-glucose: type 2 diabetes, r = −0.746, p < 0.05; healthy, r = −0.433, p < 0.05) and glucose variability (SD−15–240 min-glucose: type 2 diabetes, r = −0.578, p < 0.05; healthy, r = −0.526, p < 0.05), as well as with increasing GLP-1 (AUC−15–120 min-GLP-1: type 2 diabetes, r = 0.437, p < 0.05; healthy, r = 0.300, p = 0.107) and glucagon (AUC−15–120 min-glucagon: type 2 diabetes, r = 0.399, p < 0.05; healthy, r = 0.471, p < 0.05). The measured outcomes were comparable between the two randomised groups.

Conclusions/interpretation

Meal sequence can play a role in postprandial glucose control through both delayed gastric emptying and enhanced incretin secretion. Our findings provide clues for medical nutrition therapy to better prevent and manage type 2 diabetes.

Trial registration:

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000017434.

Funding:

Japan Society for Promotion of Science, Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care, and Japan Vascular Disease Research Foundation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00125-015-3841-z) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: Gastric emptying, GIP, GLP-1, Meal sequence, Postprandial glucose variability

Introduction

Postprandial glucose homeostasis is controlled by numerous factors including meal size and composition, gastric emptying and intestinal glucose absorption through the secretion and action of insulin and glucagon, and the incretins. As postprandial glucose elevation and variability are implicated in the pathogenesis of micro- and macro-vascular complications related to diabetes [1–3], they represent an important area of study from both a pharmacological and medical nutrition therapy perspective. The quantity and type of carbohydrate in a meal influences postprandial glucose excursion; the total amount of carbohydrate is the primary predictor of the glycaemic response [4]. However, recent studies indicate that preloading of foods such as vegetables, whey proteins and olive oil before carbohydrate intake can improve postprandial glucose excursions in type 2 diabetes [5–7], suggesting meal sequence as a novel target in management of postprandial glucose excursion in type 2 diabetes.

The gastric emptying rate is known to be critical in early and overall postprandial glucose excursions in individuals both with and without type 2 diabetes; even modest changes in the rate of gastric emptying or glucose entry into the duodenum have a substantial impact on glucose excursion after ingestion of various carbohydrates [8, 9]. Gastric emptying is known to be controlled by neuro-endocrine systems involving gut-derived hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), cholecystokinin and peptide tyrosine tyrosine, which delay gastric emptying, and motilin and ghrelin, which accelerate gastric emptying [8, 9]. These gut-derived hormones mediate gastric emptying rate through macronutrient composition (fat, protein and carbohydrate) [8, 9]. Previous studies found that preload of whey protein or olive oil enhanced GLP-1 secretion and delayed gastric emptying in individuals both with and without type 2 diabetes [6, 7], suggesting that preload of small amounts of proteins or fats before meals might be effective in postprandial glucose control for diabetes. However, this model needs to be tested with more generally available, ordinary foods for such nutrition therapy to be practicable in patients’ daily lives.

Incretin is an important area of research for postprandial glucose management; the hormones are known to be responsible for more that 50–70% of insulin secretion after oral ingestion of glucose [10–12]. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 are secreted from the gut in response to ingestion of nutrients including carbohydrates, proteins and fats, and enhance insulin secretion glucose-dependently to exert their glucose-lowering effects [10–12]. GLP-1 also delays gastric emptying rate and suppresses glucagon secretion, which ameliorates postprandial glucose elevation [10–12]. It has been demonstrated that GIP has no such effects, but facilitates fat accumulation, increasingly impairing glycaemic control [13]. Pharmacological interventions targeting incretins, such as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) and GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), are widely used in the management of type 2 diabetes [11, 14]. However, nutritional intervention based on the incretins has not been established. Preload of some proteins or fats ameliorates postprandial glucose elevation through enhancement of GLP-1 secretion and delayed gastric emptying [6, 7, 15]. Previous studies in cultured cells and experimental animals also indicate that fish oils, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA), enhance GLP-1 secretion [16, 17]; we hypothesised that nutrients in fish might stimulate GLP-1 secretion and improve postprandial glucose elevation.

In this study, we compared the effects of fish before and after rice intake, in a crossover fashion, on postprandial glucose excursion, gastric emptying and incretin secretion in type 2 diabetes patients and healthy controls. We also included a meat before rice (MR) intake arm, as a comparator for the fish before rice (FR) arm, using meat with total calorie and protein/fat ratio similar to fish in the same individuals.

Methods

The protocol (UMIN registration number: UMIN000017434) was approved by the ethics committee of Kansai Electric Power Hospital and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Individuals with untreated type 2 diabetes and healthy volunteers aged 30–75 years, HbA1c 9.0% (75 mmol/mol) or less, and BMI 35 kg/m2 or less were recruited to investigate the effects of meal sequence on postprandial glucose excursion, secretion of insulin, glucagon and the incretins and on gastric emptying (Table 1). At screening, participants with type 1 diabetes, gastrointestinal tract disease including gastroparesis, history of gastrointestinal operation, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, pancreatic disease, liver disease, renal disease, alcohol or drug abuse, glucose-lowering medication, diabetogenic medication or malignancy, or pregnancy were excluded. Individuals allergic to mackerel were excluded. No participants had thyroid diseases. Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes accords to the criteria of the Japanese Diabetes Society [18]. No individuals demonstrated positive Schellong test or decreased coefficient of RR interval in electrocardiogram variation, suggesting the absence of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Previous studies employing six to eight individuals with type 2 diabetes demonstrated that preload of whey protein or olive oil ameliorated postprandial glucose excursion, enhanced GLP-1 secretion and delayed gastric emptying [6, 7]. Our preliminary experiments employing 12–13 individuals with type 2 diabetes demonstrated that preload of fish or meat suppressed postprandial glucose elevation and enhanced GLP-1 secretion (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Figs 1-6). These results supported the current exploratory study sample size of 10–12 individuals each for controls and type 2 diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals with type 2 diabetes and healthy controls participating in the current study

| Healthy controls | Type 2 diabetes | |

|---|---|---|

| n (male/female) | 10 (10/0) | 12 (9/3) |

| Age (years) | 38.4 ± 4.9 | 59.7 ± 9.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 2.4 | 25.3 ± 4.1 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | – | 3.6 ± 5.5 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 4.86 ± 0.13 | 6.84 ± 0.31 |

| HbA1c (%) (mmol/mol) | 5.4 ± 0.3 (35.1 ± 8.2) | 6.6 ± 0.5 (49.1 ± 5.2) |

| HOMA-IR | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 2.2 |

| HOMA-β | 81.1 ± 27.7 | 55.1 ± 47.9 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 115.3 ± 8.2 | 123.6 ± 11.4 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 72.4 ± 7.0 | 76.7 ± 10.5 |

Each value indicates the mean ± SD

Meal sequence test

Participants were subjected to meal sequence tests in the morning after overnight fast on three separate days: FR and rice before fish (RF) on the first 2 days in a crossover manner, and MR on the third day. In FR and MR, participants first ingested 920 kJ of boiled mackerel or grilled beef (ESM Table 1) and, 15 min later, 1,004 kJ of steamed rice. In RF, participants first ingested 1,004 kJ of steamed rice followed by 920 kJ of boiled mackerel 15 min later. The time patients received steamed rice is defined as 0 (in the experiments described in ESM Figs 1-6, the time at which patients received the first dish was defined as 0). The boiled mackerel and grilled beef had similar calorie and protein/fat ratio with limited carbohydrates. The amounts of boiled mackerel, grilled beef and steamed rice were prepared such that total energy and nutrient balance (protein:fat:carbohydrate ratio) were within dietary recommendations by the Japan Diabetes Society [19]. To measure levels of glucose and selected hormones, blood samples were withdrawn at −15, 0, 15, 30 60, 90, 120 and 240 min and stored as described previously [20]. To analyse gastric emptying rate, end-tidal breath samples were collected into small exhalation bags (PYLORI-BAG20, Otsuka Electronics Company, Osaka, Japan) at −15 min, 0 min and every 5 min until 120 min, and every 30 min until 240 min as recommended by the Japan Society of Smooth Muscle Research [21]. End-tidal breath samples were also collected into three large exhalation bags (PYLORI-BAG1.3L, Otsuka Electronics Company) at −15 min to use as reference for exhalation gas analysis. The canned boiled mackerel (4901901145899, Maruha Nichiro Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was obtained commercially and stored at room temperature until use. The grilled beef was prepared by grilling sirloins of beef on an iron plate and subdividing them into small pieces stored in vacuum packs at −20°C. The boiled mackerel and grilled beef were prepared without seasonings that might affect digestion or absorption of ingested foods. The rice was prepared by steaming with 13C-labelled sodium acetate (CLM-156-0, Cambridge Isotope, MA, USA) at a ratio of 150 g steamed rice and 200 mg of 13C-labelled sodium acetate, and was stored at −20°C until use. The boiled mackerel, grilled beef and steamed rice were microwaved before being served.

Laboratory determinations

Hormones were measured using the following assays as described previously [20, 22]. Total GLP-1, human total GLP-1 (ver. 2) assay kit (K150JVC-2; Mesoscale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD, USA); total GIP, human GIP (total) ELISA (EZHGIP-54K; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany); glucagon, glucagon RIA (GL-3K; Merck Millipore); insulin, lumipulse presto insulin (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan); and C-peptide, lumipulse presto C-peptide (Fujirebio). Gastric emptying rate was determined by mathematical modelling, based on changes of the 13CO2/12CO2 ratio in breath samples measured by an infrared spectral analyser (POCone, Otsuka Electronics Company) [23]. Stable 13C-labelled sodium acetate is emptied from the stomach following the trituration and liquefaction of the steamed rice, and is transported to the liver via the portal vein, where it is oxidised to 13CO2 and exhaled into breath. The Wagner–Nelson method was applied to adjust the time for 13CO2 distribution [8, 24]. Other laboratory measurements including HbA1c and plasma glucose were done by standard assays.

Calculations and statistical analyses

Results are reported as mean ± SE of the mean unless otherwise stated. AUC of each measurement was calculated according to the trapezoidal rule. Standard deviation (SD)-glucose was expressed as SD of glucose levels from −15 min to 240 min. All statistical calculations were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows ver. 22 (SAS Institute, Berkeley, CA, USA). Repeated measures were analysed by mixed effects model. AUCs, SDs, and half time for emptying ingested steamed rice (Time 50%) were compared by Wilcoxon rank sum test. A p value <0.05 was taken to indicate significant differences.

Results

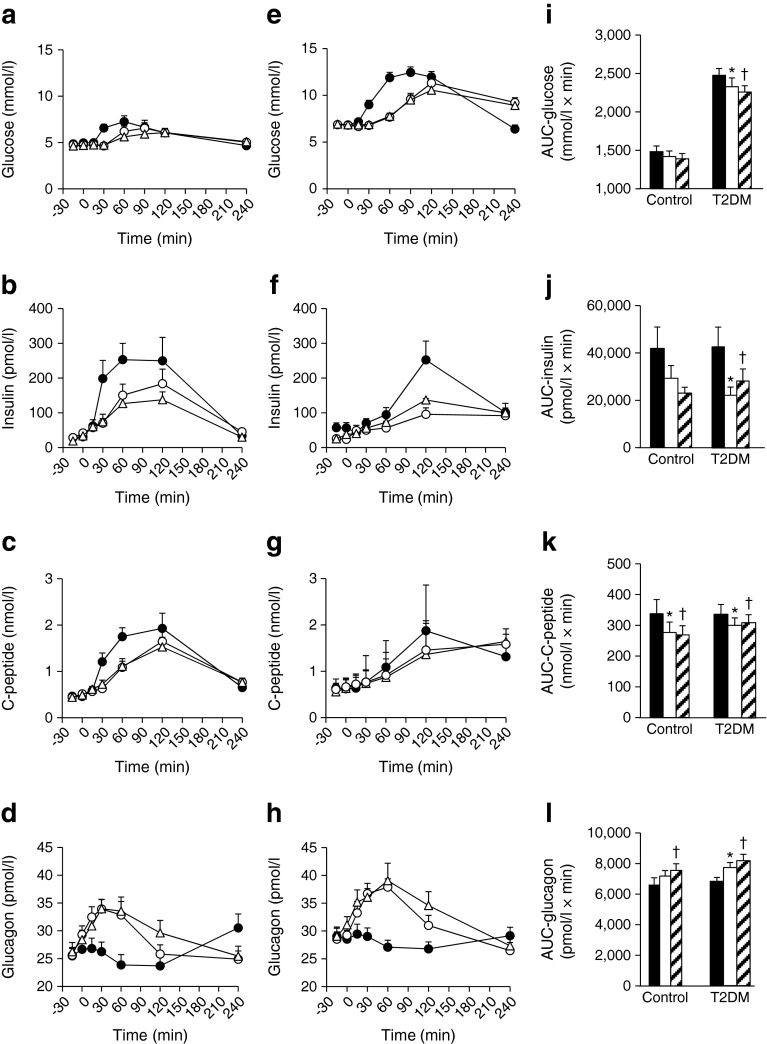

Effects of changing meal sequence (RF, FR and MR) on glucose excursion, and secretions of insulin and glucagon were assessed. In FR and MR, in comparison with RF, the rapid glucose elevation after rice ingestion was suppressed in type 2 diabetes and controls (Fig. 1). FR and MR suppressed glucose elevation from 30 to 90 min in type 2 diabetes, but elevated glucose levels at 240 min. Similar suppressive effects by FR and MR on glucose elevation were observed in controls. Likewise, FR and MR lowered both AUC−15–240 min-glucose (Fig. 1) and SD−15–240 min-glucose (type 2 diabetes, FR 1.94 ± 0.22 mmol/l, MR 1.68 ± 0.18 mmol/l, RF 2.77 ± 0.24 mmol/l; healthy, FR 0.95 ± 0.21 mmol/l, MR 0.83 ± 0.16 mmol/l, RF 1.18 ± 0.27 mmol/l) in type 2 diabetes and controls; the reduction in AUC−15–240 min-glucose and SD−15–240 min-glucose reached statistical significance in type 2 diabetes but not in controls, possibly due to the milder glucose elevation after rice ingestion. No significant differences in AUC−15–240 min-glucose and SD−15–240 min-glucose were observed between FR and MR in type 2 diabetes or controls. To clarify the mechanism of suppressed glucose elevation by FR and MR, the levels of insulin, C-peptide and glucagon were examined (Fig. 1). Insulin and C-peptide levels after rice ingestion as well as AUC−15–240 min-insulin and AUC−15–240 min-C-peptide were reduced by FR and MR in T2DM and controls, compared with RF. Reduction of AUC−15–240 min-insulin in type 2 diabetes and reduction of AUC−15–240 min-C-peptide in type 2 diabetes and controls reached statistical significance. Levels of glucagon and AUC−15–240 min-glucagon were elevated by FR and MR in type 2 diabetes and controls, when compared with RF. Elevation of AUC−15–240 min-glucagon by FR in type 2 diabetes and by MR in type 2 diabetes and controls reached statistical significance. No significant differences in AUC−15–240 min-insulin, AUC−15–240 min-C-peptide, or AUC−15–240 min-glucagon were observed between FR and MR in type 2 diabetes and controls. Similar results in type 2 diabetes were obtained in experiments comparing FR and RF (ESM Fig. 1), MR and rice before meat (RM) (ESM Fig. 3), and MR and FR (ESM Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

Time course curves are indicated for glucose, insulin, C-peptide and glucagon in healthy controls (a–d) and patients with type 2 diabetes (e–h) during three different meal sequences: RF, black circles; FR, white circles; or MR, white triangles (a–h). The p values for differences due to sequence (X), time (Y), and the interaction of sequence and time (Z), were calculated by mixed effects models as follows: (a) X0.000, Y0.001 and Z0.007; (b) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.012; (c) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.001; (d) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000; (e) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000; (f) X0.000, Y0.004 and Z0.614; (g) X0.000, Y0.163 and Z0.000; (h) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000. AUC−15–240 min are indicated (RF, black bars; FR, white bars; MR, hatched bars) (i–l). AUCs were analysed by Wilcoxon’s rank sum test; * and † indicate p < 0.05 for RF vs FR, and RF vs MR, respectively

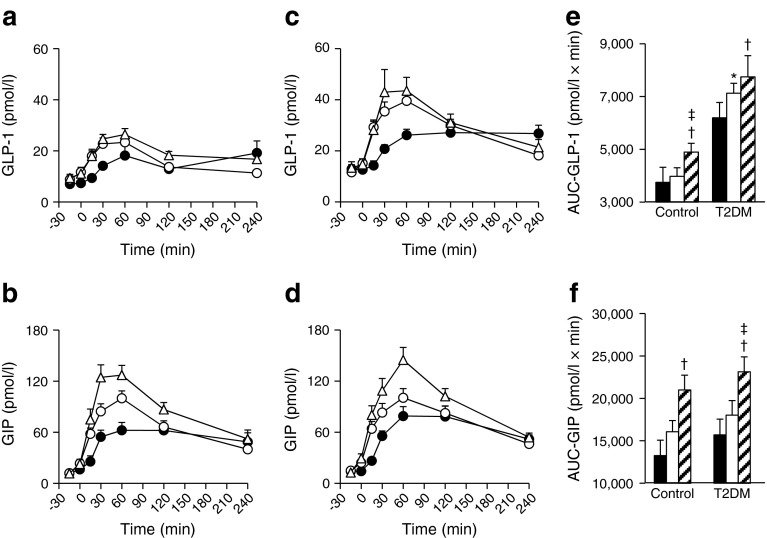

To investigate involvement of incretin secretion in the effects of FR and MR on glucose levels, GLP-1 and GIP were measured (Fig. 2). Interestingly, levels of GIP and GLP-1 were elevated by FR and MR in type 2 diabetes and controls, when compared with RF. Elevation of AUC−15–240 min-GLP-1 and AUC−15–240 min-GIP by MR in type 2 diabetes and controls and elevation of AUC−15–240 min-GLP-1 by FR in type 2 diabetes reached statistical significance. Furthermore, GIP levels were more strongly elevated in MR than FR in both type 2 diabetes and controls. The difference in AUC−15–240 min-GIP between FR and MR in type 2 diabetes reached statistical significance. The difference in AUC−15–240 min-GLP-1 between FR and MR in controls, but not in type 2 diabetes, also reached statistical significance. Similar results for type 2 diabetes were obtained in comparison with FR and RF (ESM Fig. 2), MR and RM (ESM Fig. 4), and MR and FR (ESM Fig. 6).

Fig. 2.

Time course curves are indicated for GLP-1 and GIP in healthy controls (a, b) and patients with type 2 diabetes (c, d) during three different meal sequences: RF, black circles; FR, white circles; or MR, white triangles (a–d). The p values for differences due to sequence (X), time (Y), and the interaction of sequence and time (Z), were calculated by mixed effects models as follows: (a) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000; (b) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000; (c) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000; and (d) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000. AUC−15–240 min are indicated (RF, black bars; FR, white bars; MR, hatched bars) (e, f). AUCs were analysed by Wilcoxon’s rank sum test; *, † and ‡ indicate p < 0.05 for RF vs FR; RF vs MR; and FR vs MR, respectively

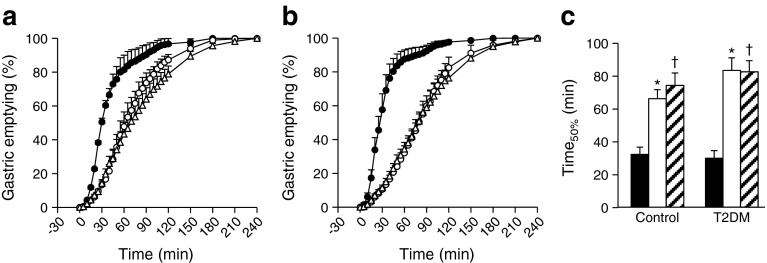

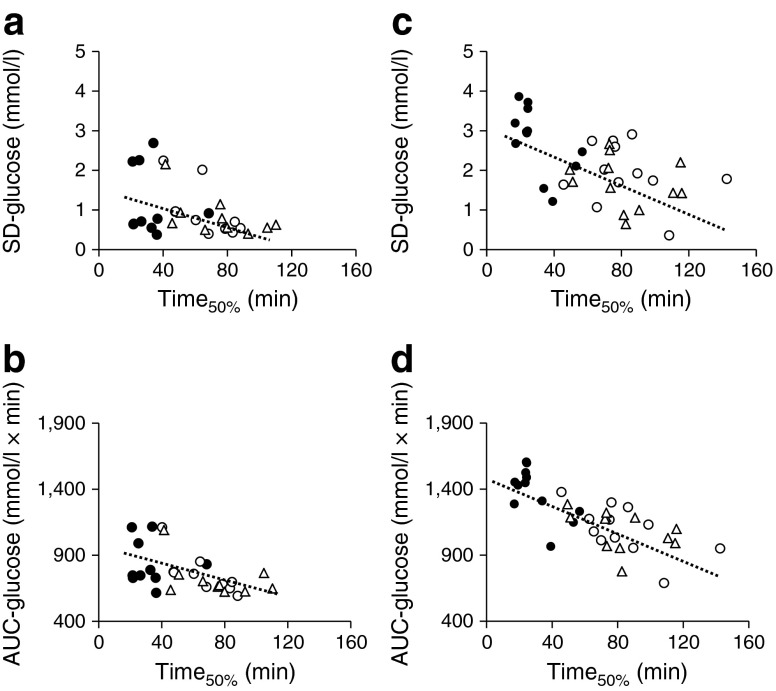

To clarify the mechanism by which FR and MR affect glucose levels, the gastric emptying rate was measured using a 13C-acetate breath test. FR and MR significantly delayed gastric emptying rate and extended Time50%, the time required for 50% of 13C-labelled acetate to exit the stomach, in type 2 diabetes and controls (Fig. 3). Interestingly, Time50% was well correlated with AUC−15–120 min-glucose and SD−15–240 min-glucose in type 2 diabetes and controls (Fig. 4), indicating that extension of the gastric emptying rate of rice plays a pivotal role in suppression of glucose elevation in FR and MR. Correlation of Time50% with AUC−15–120 min-glucagon (type 2 diabetes, r = 0.399, p < 0.05; controls, r = 0.471, p < 0.05) and AUC−15–120 min-GLP-1 (type 2 diabetes, r = 0.437, p < 0.05; controls, r = 0.300, p = 0.107) suggests involvement of glucagon and/or GLP-1 in this process.

Fig. 3.

Time course curves are indicated for gastric emptying in healthy controls (a) and patients with type 2 diabetes (b) during three different meal sequences: RF, black circles; FR, white circles; or MR, white triangles (a, b). The p values for differences due to sequence (X), time (Y), and the interaction of sequence and time (Z), were calculated by mixed effects models as follows: (a) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000; and (b) X0.000, Y0.000 and Z0.000. Half times for emptying the ingested steamed rice (Time50%) are indicated (RF, black bars; FR, white bars; MR, hatched bars) (c). Time50% was analysed by Wilcoxon’s rank sum test; * and † indicate p < 0.05 for RF vs FR, and RF vs MR, respectively

Fig. 4.

Scatter plots of SD−15–240 min-glucose (SD-glucose) and AUC−15–120 min-glucose (AUC-glucose) with time 50% during meal sequence tests (Time50%) were plotted (RF, black circles; FR, white circles; MR, white triangles) for healthy controls (a, b) and type 2 diabetes patients (c, d). The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and p values were calculated, respectively, as follows: (a) r = −0.526, p < 0.05; (b) r = −0.433, p < 0.05; (c) r = −0.578, p < 0.05; and (d) r = −0.746, p < 0.05

Discussion

We find in this study that altered meal sequence can improve postprandial glucose regulation through delayed gastric emptying in type 2 diabetes and healthy controls. FR and MR enhanced glucagon and GLP-1, both of which may be involved in delayed gastric emptying. We also found that GIP secretion is affected by meal composition as well as meal sequence.

Postprandial glucose excursion is influenced by many factors including meal size and composition, gastric emptying and intestinal glucose absorption, as well as secretion and action of insulin and glucagon and the incretins. The gastric emptying rate accounts for ~35% of the variance in the initial rise of postprandial glucose levels in healthy and type 2 diabetes individuals [8, 9]. Delayed gastric emptying is well correlated with glucose excursions and glucose variability (Fig. 4). Remaining questions include how FR and MR slow the gastric emptying rate. Previous studies found that nutrients in ingested foods, including proteins and fats, influence differences in gastric emptying rate, possibly through modulation of GLP-1 [25, 26]. While the nutrients in fish and meat responsible for the modulation of gastric emptying remain unknown, the levels of glucagon and GLP-1 were well correlated with the gastric emptying rate, indicating involvement of glucagon and/or GLP-1 in the process. In addition, it is possible that cholecystokinin, which is secreted from the duodenum and jejunum in response to ingestion of fat and protein and delays gastric emptying [8, 9], might also be involved in this process, but the hormone was not measured in the present study. While the second meal phenomenon, in which suppression of NEFA after preloading low-carbohydrate and protein-rich snacks 1–2 h before meals associates with amelioration of postprandial glucose excursions, has been discussed in health and type 2 diabetes [27–29], the current study found no NEFA suppression by fish or meat preload, indicating that the current finding differs from the second meal phenomenon (DY, unpublished observations).

Preload of fish or meat before rice similarly enhanced GLP-1 secretion (Fig. 2, and ESM Figs 2, 4, 6). We initially supposed that fish oils such as EPA and DHA might selectively enhance GLP-1 secretion; such fatty acid-enhanced GLP-1 secretion occurs in cultured cells and experimental animals [16, 17]. However, the similarity of the effects of fish and meat on GLP-1 secretion indicates little involvement of fish oils. This is consistent with our observation that oral ingestion of EPA and preload of EPA before meal ingestion did not enhance GLP-1 secretion in humans (DY, unpublished observations). It was previously reported that preload of olive oil, whey proteins or glutamine before ingestion of carbohydrates enhanced GLP-1 secretion and delayed gastric emptying [6, 7, 15, 30].

On the other hand, preload of meat promoted GIP secretion but fish did not (Fig. 2). The fish and the meat meal used in the current study differed in fatty acid composition but had similar amino acid composition (ESM Table 1). It is known that saturated and monounsaturated fats can enhance GIP secretion in humans [31, 32]. Higher GIP promotes high fat diet-induced fat accumulation [13], suggesting that preload of meat before carbohydrates chronically could result in increased fat accumulation and increased insulin resistance. Our group previously reported that the HbA1c-lowering effects of DPP-4i were significantly correlated with estimated daily fish intake, and, to a lesser degree, with that of meat [33]. The chronic effects of fish and meat preload prior to carbohydrate on the therapeutic efficacy of DPP-4i in randomised, controlled clinical trials needs be examined in future.

Enhanced incretin secretion was not correlated with changes in the secretion of insulin or glucagon in the current study. Insulin and C-peptide levels were decreased by fish and meat preload in type 2 diabetes and healthy individuals, despite enhanced secretions of GIP and GLP-1 that should stimulate insulin secretion glucose-dependently. Previous studies on preloading whey proteins or glutamine showed increased insulin secretion concomitant with enhanced GLP-1 secretions [6, 15, 30]; however, the study on preloading olive oil showed no such enhancement [7]. Gastric emptying appears to be delayed more strongly by olive oil than by whey proteins [6, 7]. It is possible that stronger inhibition of gastric emptying limits the glucose elevation, thereby minimising the enhancement of glucose-dependent insulin secretion by incretins. A similar scenario has been noted between short- and long-acting GLP-1RA [14, 34]: short-acting GLP-1RA has stronger effects on gastric emptying but limited action on postprandial insulin secretion. Thus, enhanced glucagon secretion due to slower gastric emptying by fish and meat preload could result from stimulatory effects of amino acids on glucagon secretion at early time points and/or delayed inhibitory effects of glucose at later time points [35]. In addition, the effects of GLP-1 and GIP on glucagon secretion are glucose-dependent [36, 37], and may have limited effects on glucagon secretion.

Meal sequence has similar effects in type 2 diabetes and controls, which raises questions. First, levels of insulin and C-peptide immediately after ingestion of rice are much lower in type 2 diabetes compared with controls, while AUC−15–240 min-insulin in type 2 diabetes and AUC−15–240 min-C-peptide is comparable between type 2 diabetes and controls (Fig. 1). These findings are consistent with previous findings that insulin secretion immediately after ingestion of glucose or mixed meal is substantially impaired in Japanese patients with even short duration of the disease [38, 39]. Second, GLP-1 levels after rice ingestion and AUC−15–240 min-GLP-1 were much higher in type 2 diabetes than in controls. While it has been demonstrated that glucose tolerance does not affect GLP-1 secretion after ingestion of glucose or mixed meal [38, 40], the GLP-1 response in a particular meal sequence might differ between type 2 diabetes and controls. Further investigations are needed to characterise the GLP-1 responses during altered meal sequences. Moreover, glucagon levels after rice ingestion and AUC−15–240 min-glucagon were similar in type 2 diabetes and controls. Although hypersecretion of glucagon after ingestion of glucose or mixed meal is well known in type 2 diabetes [38], this might not be observed in this study because our participants had only mild type 2 diabetes.

The current study has limitations. The present experiment was intended to examine the effects of meal sequence in a single meal in a workable fashion, and was designed with a uniform 15 min interval between fish or meat and rice, which is similar to the interval used in previous studies (30 min) but potentially more practicable [6, 7]. Additional investigation is required to clarify optimal time intervals as well as amount, form and type of foods. Prospective, randomised clinical trials also are required to evaluate the chronic impact of altered meal sequences in type 2 diabetes management and prevention. In addition, the underlying mechanism of delayed gastric emptying by fish or meat preload remains largely unknown, although increased GLP-1 and glucagon levels are important in the process. The mechanisms by which altered meal sequence links to changes in the secretions of GLP-1 and GIP remain unclear, despite recent findings on the molecular regulation of incretin secretions [41]. Studies using cultured cells and experimental animals are in progress to identify possible dietary and pharmacological targets for management of postprandial glucose excursions. Although a ‘rice before meat’ arm might help to complete the current findings, it was not included to lighten the burden of the participants, and the results were expected from our preliminary studies (ESM Figs 1–6).

In conclusion, meal sequence is an important regulator of gastric emptying rate and postprandial glucose elevation through GLP-1 and glucagon secretions in individuals both with and without type 2 diabetes. Our current findings on meal sequence and composition with regard to the incretin secretions provide clues for medical nutrition therapy to better prevent and manage type 2 diabetes.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 328 kb)

(PDF 273 kb)

(PDF 326 kb)

(PDF 272 kb)

(PDF 273 kb)

(PDF 245 kb)

(PDF 60 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to all past and present members of the Center for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism; and the Center for Metabolism and Clinical Nutrition, Kansai Electric Power Hospital who contributed to the work. The authors especially thank T. Murakami, T. Yamaguchi and H. Eto of Kansai Electric Power Hospital for technical support. We also thank M. Yamane of Kansai Electric Power Hospital for secretarial assistance. The current study was presented by D. Yabe et al as an abstract entitled ‘Comparison of fish or meat intake before and after rice on postprandial glucose excursions and incretin secretion in type 2 diabetes: meal-sequence as a novel target in dietary therapies for diabetes’ (Abstract number: SUN-1063) at the 96th Annual Meeting and Expo of the Endocrine Society (Chicago, 12–24 June 2014); and by D. Yabe et al as a late breaking abstract entitled ‘Effects of fish or meat intake before and after rice on postprandial glucose excursions and incretin secretion in type 2 diabetes: meal sequence as a novel target in dietary therapies for diabetes’ (Number 52-LB; Category 18 Nutrition-Clinical) at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the ADA (San Francisco, 5–9 June 2014).

Abbreviations

- DHA

Docosahexanoic acid

- DPP-4i

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

- EPA

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- FR

Fish before rice

- GIP

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- GLP-1RA

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

- MR

Meat before rice

- RF

Rice before fish

- RM

Rice before meat

Funding

This study was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science, Grants for young researchers from the Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care, and Grants from the Japan Vascular Disease Research Foundation.

Duality of interest

DY received consulting and/or speaker fees from Eli Lilly Japan K.K., MSD K.K., Sanofi K.K., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited and Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. DY received clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company and MSD K.K. SSe received consulting and/or speaker fees from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited and Astellas Pharma Inc. SSe also received clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd, MSD K.K., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Sanofi K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Astellas Pharma Inc., Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma K.K. and Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. TK received consulting and/or speaker fees from Astellas Pharma Inc., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi K.K., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd, MSD K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Kowa Company Ltd, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, AstraZeneca K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd. TK also received clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd, MSD K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Nippon Eli Lilly K.K., Teijin Ltd, and Sanofi K.K. YSe received consulting and/or speaker fees from Nippon Eli Lilly K.K., Sanofi, K.K., Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd, Glaxo-Smith-Kline K.K., Taisho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Astellas Pharma Inc., BD, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson K.K. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. YSe received clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company and MSD K.K. CN is an employee of Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd. All other authors declare no duality of interest associated with their contribution to this manuscript.

Contribution statement

DY, HK, MI, SSh and YS contributed to conception and design of the research, collection and analysis of data, and writing the manuscript. KM, HM and SSe contributed to design of the research, incretin measurements, and revision of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KN and CN contributed to design of the research, measurements of gastric emptying of ingested rice, and revision of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. KM contributed to design of the research, statistical analysis, and revision of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. TK contributed to design of the research, analysis and interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the version to be published. DY and YS are the guarantors of this work.

Footnotes

Hitoshi Kuwata, Masahiro Iwasaki and Shinobu Shimizu contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Smith-Palmer J, Brandle M, Trevisan R, Orsini Federici M, Liabat S, Valentine W. Assessment of the association between glycemic variability and diabetes-related complications in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The DECODE study group on behalf of the European Diabetes Epidemiology Group Glucose tolerance and mortality: comparison of WHO and American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria. Lancet. 1999;354:617–621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiter LA, Ceriello A, Davidson JA, et al. Postprandial glucose regulation: new data and new implications. Clin Ther. 2005;27(Suppl B):S42–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, et al. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S120–S143. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai S, Matsuda M, Hasegawa G, et al. A simple meal plan of ‘eating vegetables before carbohydrate’ was more effective for achieving glycemic control than an exchange-based meal plan in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J, Stevens JE, Cukier K, et al. Effects of a protein preload on gastric emptying, glycemia, and gut hormones after a carbohydrate meal in diet-controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1600–1602. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gentilcore D, Chaikomin R, Jones KL, et al. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2062–2067. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips LK, Deane AM, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Gastric emptying and glycaemia in health and diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;11:112–128. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips LK, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Measurement of gastric emptying in diabetes. J Diabet Complicat. 2014;28:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1409–1439. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seino Y, Fukushima M, Yabe D. GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: similarities and differences. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drucker DJ. Incretin action in the pancreas: potential promise, possible perils, and pathological pitfalls. Diabetes. 2013;62:3316–3323. doi: 10.2337/db13-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seino Y, Yabe D. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1: incretin actions beyond the pancreas. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:108–130. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yabe D, Seino Y. Defining the role of GLP-1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2014;9:659–670. doi: 10.1586/17446651.2014.949672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samocha-Bonet D, Wong O, Synnott EL, et al. Glutamine reduces postprandial glycemia and augments the glucagon-like peptide-1 response in type 2 diabetes patients. J Nutr. 2011;141:1233–1238. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.139824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, et al. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med. 2005;11:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morishita M, Tanaka T, Shida T, Takayama K. Usefulness of colon targeted DHA and EPA as novel diabetes medications that promote intrinsic GLP-1 secretion. J Control Release. 2008;132:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N, et al. Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1:212–228. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tajima N, Noda M, Origasa H, et al. Evidence-based practice guideline for the treatment for diabetes in Japan 2013. Diabetol Int. 2015;6:151–187. doi: 10.1007/s13340-015-0206-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabe D, Watanabe K, Sugawara K, et al. Comparison of incretin immunoassays with or without plasma extraction: incretin secretion in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:70–79. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanaka M, Nakada K. Stable isotope breath tests for assessing gastric emptying: a comprehensive review. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2010;46:267–280. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.46.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yabe D, Rokutan M, Miura Y, et al. Enhanced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in a patient with glucagonoma: implications for glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from pancreatic alpha cells in vivo. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102:e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanaka M, Nakada K, Nosaka C, Kuyama Y. The Wagner-Nelson method makes the [13C]-breath test comparable to radioscintigraphy in measuring gastric emptying of a solid/liquid mixed meal in humans. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:641–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin AS, Camilleri M. Diagnostic assessment of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes. 2013;62:2667–2673. doi: 10.2337/db12-1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma J, Checklin HL, Wishart JM, et al. A randomised trial of enteric-coated nutrient pellets to stimulate gastrointestinal peptide release and lower glycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1236–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu T, Bound MJ, Standfield SD, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. Effects of taurocholic acid on glycemic, glucagon-like peptide-1, and insulin responses to small intestinal glucose infusion in healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E718–E722. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolever TM, Bentum-Williams A, Jenkins DJ. Physiological modulation of plasma free fatty acid concentrations by diet. Metabolic implications in nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:962–970. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.7.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jovanovic A, Gerrard J, Taylor R. The second-meal phenomenon in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1199–1201. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen MJ, Jovanovic A, Taylor R. Utilizing the second-meal effect in type 2 diabetes: practical use of a soya-yogurt snack. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2552–2554. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakubowicz D, Froy O, Ahren B, et al. Incretin, insulinotropic and glucose-lowering effects of whey protein pre-load in type 2 diabetes: a randomised clinical trial. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1807–1811. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh K, Moriguchi R, Yamada Y, et al. High saturated fatty acid intake induces insulin secretion by elevating gastric inhibitory polypeptide levels in healthy individuals. Nutr Res. 2014;34:653–660. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lardinois CK, Starich GH, Mazzaferri EL. The postprandial response of gastric inhibitory polypeptide to various dietary fats in man. J Am Coll Nutr. 1988;7:241–247. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1988.10720241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwasaki M, Hoshian F, Tsuji T, et al. Predicting efficacy of DPP-4 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: association of HbA1c reduction with serum eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid levels. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:464–467. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meier JJ. GLP-1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:728–742. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawamori D, Welters HJ, Kulkarni RN. Molecular pathways underlying the pathogenesis of pancreatic alpha-cell dysfunction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;654:421–445. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3271-3_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holst JJ, Christensen M, Lund A, et al. Regulation of glucagon secretion by incretins. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(Suppl 1):S89–S94. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lund A, Bagger JI, Christensen M, Knop FK, Vilsboll T. Glucagon and type 2 diabetes: the return of the alpha cell. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:555. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0555-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yabe D, Kuroe A, Watanabe K, et al. Early phase glucagon and insulin secretory abnormalities, but not incretin secretion, are similarly responsible for hyperglycemia after ingestion of nutrients. J Diab Complicat. 2015;29:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yabe D, Seino Y, Fukushima M, Seino S. Beta cell dysfunction versus insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes in East Asians. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:602. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0602-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calanna S, Christensen M, Holst JJ, et al. Secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses of clinical studies. Diabetologia. 2013;56:965–972. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2841-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ezcurra M, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Emery E. Molecular mechanisms of incretin hormone secretion. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:922–927. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 328 kb)

(PDF 273 kb)

(PDF 326 kb)

(PDF 272 kb)

(PDF 273 kb)

(PDF 245 kb)

(PDF 60 kb)