Abstract

Fungal 1,11 cyclizing sesquiterpene synthases are product specific under typical reaction conditions. However, in vivo expression of certain Δ6-protoilludene synthases results in a dual 1,11 and 1,10 cyclization cascade. To determine the factors regulating this mechanistic versatility, in depth characterization of Δ6-protoilludene synthases was conducted in vitro. Divalent metal ions determine cyclization specificity and product promiscuity in Δ6-protoilludene synthases, resulting in dual 1,11 and 1,10 cyclizations. Promiscuity in metal binding is mediated by secondary metal binding sites beyond the conserved D(D/E)XX(D/E) motif that exists in sesquiterpene synthases. We conducted in depth phylogenetic analyses, which revealed a divergent evolution of Basidiomycota trans-humulyl cation producing sesquiterpene synthases, results that indicate a wider diversity in function than previously predicted. This study provides key insights into the functionality and evolution of 1,11 cyclizing fungal sesquiterpene synthases.

Keywords: kinetics, anticancer agents, biosynthesis, natural products, GC/MS

Introduction

Sesquiterpenes are a diverse class of natural products derived from the C15 isoprenoid farnesyl pyrophosphate ((2E,6E)-FPP). Sesquiterpene synthases cyclize this precursor into a variety of volatile hydrocarbon scaffolds. The first step in the cyclization mechanism involves a metal-dependent ionization of (2E,6E)-FPP to release pyrophosphate. Depending on the sesquiterpene synthase, the resulting reactive carbocation can undergo an intramolecular electrophilic attack on the C10-C11 double-bond to yield either the (E,E)-germacradienyl carbocation [1] or trans-humulyl carbocation [2] via a 1,10- or 1,11-cyclization reaction, respectively. Alternatively, certain sesquiterpene synthases catalyze an initial isomerization of the C2-C3 bond of (2E,6E)-FPP, resulting in (3R)-nerolidyl pyrophosphate (3R-NPP). This is also dephosphorylated and cyclized at either the 1,6-position to yield the bisabolyl carbocation [3–4], or potentially at the 1,10-position to yield the (Z,E)-germacradienyl carbocation [5–7]. Subsequently, these carbocations undergo a series of additional electrophilic reactions, resulting in further cyclizations, complex ring rearrangements, hydride and methyl shifts, until a final deprotonation putatively mediated by PPi [8] or attack by water [9]. This results in the release of the final sesquiterpene product(s) from the active site cavity. The nature and position of the amino acid residues lining the active site cavity determine the cyclization mechanism and product spectrum of sesquiterpene synthases [10–15]. Despite the different cyclization reactions catalyzed by these enzymes, they all share a conserved fold [1–2, 16] and two conserved active site motifs D(D/E)XX(D/E) and NSE, which are required for coordinating the divalent metal ions that stabilize the PPi moiety of the substrate [17].

Recently, in our search for the enzymes that initiate the trans-humulane-protoilludane pathway derived bioactive sesquiterpenoids of mushroom-forming fungi (Basidiomycota) [18–19, 20] we identified and characterized five novel Δ6-protoilludene synthases from Omphalotus olearius (Omp6 and Omp7) [21] and Stereum hirsutum (Stehi25180, Stehi64702 and Stehi73029) [22]. These enzymes follow a 1,11 cyclization mechanism to produce the trans-humulyl cation (7) derived Δ6-protoilludene (1) (Scheme 1). When characterized under typical reaction conditions, the purified enzymes were highly active and produced exclusively Δ6-protoilludene (1) (Scheme 1) [21–23]. The exquisite product fidelity of these enzymes contrasts with the majority of characterized sesquiterpene synthases that typically synthesize several products from the same cyclization pathway. Surprisingly, we noted that when expressed in a heterologous host, Stehi64702 and Stehi73029 were capable of following dual cyclization mechanisms, resulting in the detection of mainly the 1,11 cyclization product Δ6-protoilludene (1) but also low levels of the 1,10 cyclization product germacrene A, detected as the heat-induced Cope rearrangement product β-elemene (2) (Scheme 1) [22]. Previous characterization of Omp6 and Omp7 showed that they were highly specific and that their product specificity was not altered upon site directed mutagenesis of active site residues, nor by varying pH, temperature and concentration of NaCl, Mg2+ and Mn2+ ions [21, 23]. It was therefore unexpected that the closely related homologs Stehi64702 and Stehi73029 would be less specific when expressed in a heterologous host [22]. Apparently, despite the fact that the Δ6-protoilludene synthases from the fungal strains are closely related (sharing >50% amino acid sequence identity), a degree of mechanistic versatility must exist for alternative initial cyclization events to occur. Further, unknown environmental conditions must affect the cyclization mechanism of Stehi64702 and Stehi73029.

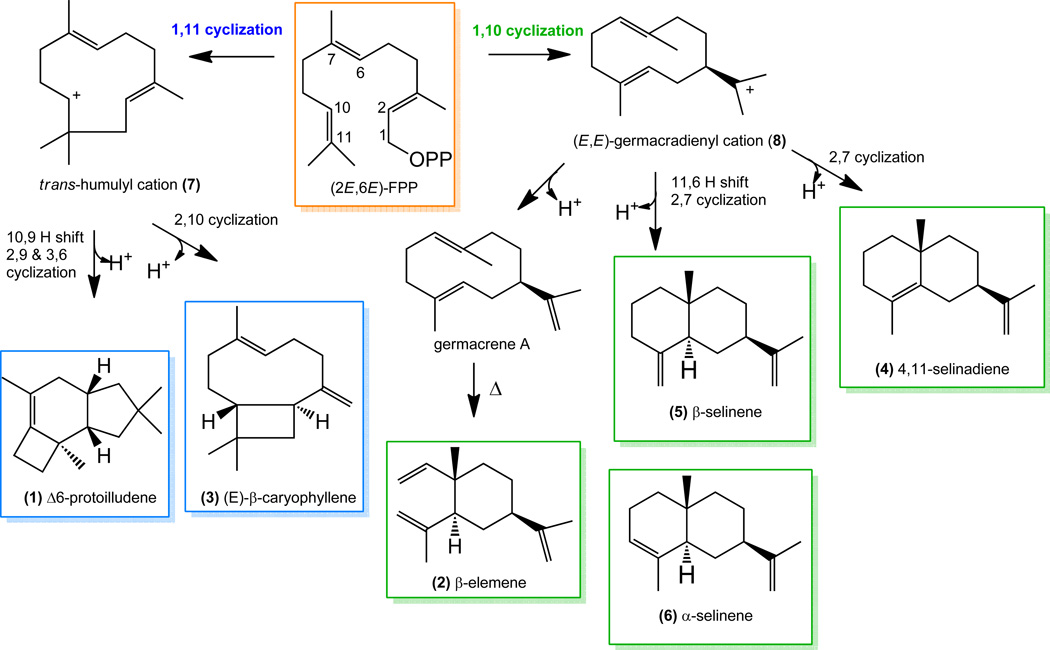

Scheme 1. Proposed mechanisms for sesquiterpene production by Δ6-protoilludene synthases.

Metal-dependent ionization results in the release of the diphosphate moiety (OPP) from farnesyl pyrophosphate ((2E,6E)-FPP) leading to either a 1,11 or 1,10 cyclization of the primary carbocation. A 1,11 cyclization leads to the trans-humulyl cation (7); a 1,10 cyclization of the primary carbocation leads to the (E,E)-germacradienyl cation (8). Further hydride shifts and cyclizations results in final sesquiterpene products (1-6).

The goal of this work was to identify the factor(s) that regulated the preference for particular cyclization mechanisms in Δ6-protoilludene synthases. Screening of reaction conditions reveal that Δ6-protoilludene synthases catalyze ionization of (2E,6E)-FPP with a diversity of divalent metals beyond the canonical Mg2+ and Mn2+ ions [24]. Furthermore, Ca2+ is a key determinant of preference for cyclization mechanism in Δ6-protoilludene synthases, switching the enzymes from a 1,11 cyclization to a dual 1,11/1,10 cyclization mechanism. Mutagenesis studies identify putative secondary metal binding sites, beyond the conserved active site motifs, that play a role in catalytic metal promiscuity. Phylogenetic analyses and modelling indicate the potential for a wider diversity in function in fungal trans-humulyl cation (7) producers than previously predicted. This study provides valuable functional and evolutionary insights into fungal trans-humulyl cation (7) producing sesquiterpene synthases.

Results and Discussion

Metal ions regulate cyclization mechanism in Δ6-protoilludene synthases

Given the different behavior of the Δ6-protoilludene synthase homologs when expressed in a heterologous host (Supplementary Figure 1), we sought to obtain their crystal structure(s) to gain detailed insights into cyclization cascades. Unfortunately, crystals of suitable diffraction quality could not be produced for Omp6 [23], nor any of the other Δ6-protoilludene synthases, despite exhaustive attempts. It was during these efforts that we noted that metal ions modulate the cyclization mechanisms of these enzymes.

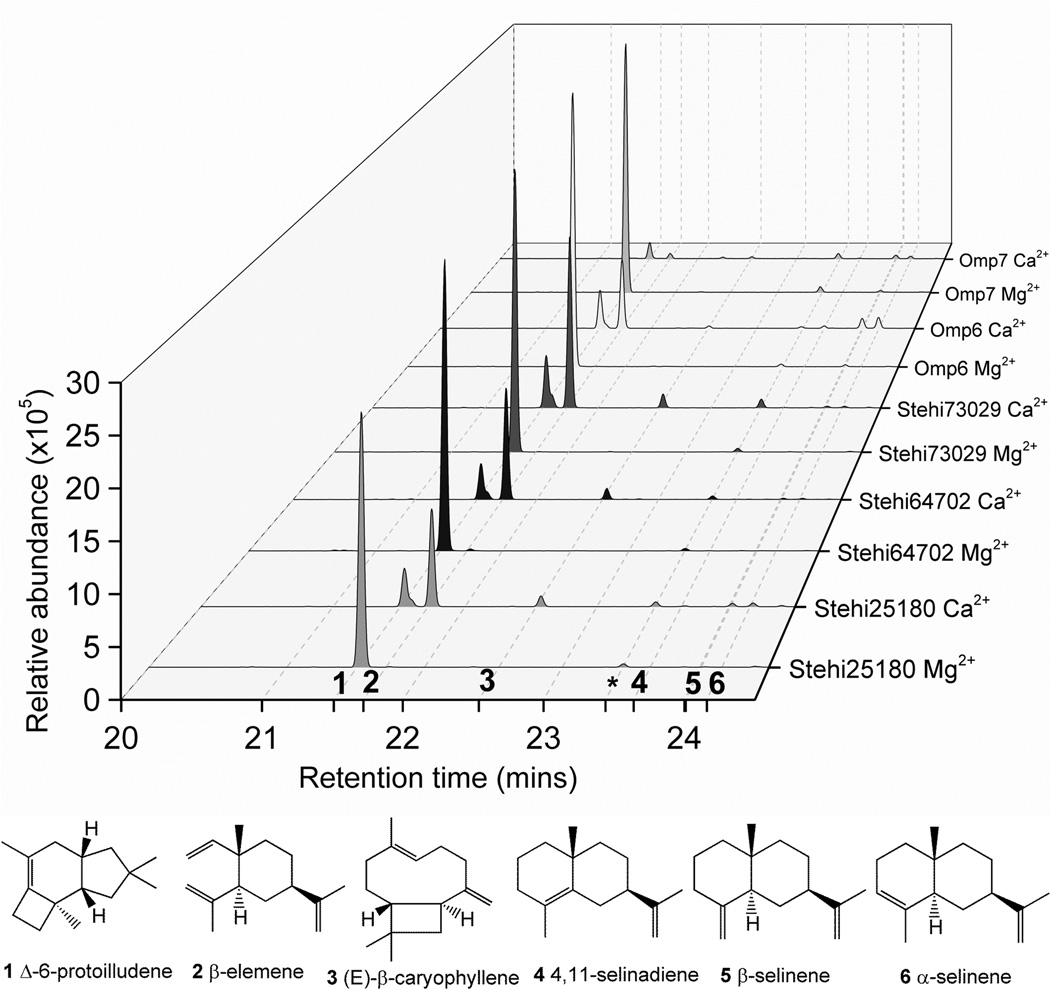

In an attempt to obtain crystals of Stehi73029, a range of buffer conditions, including the addition of CaCl2, were screened for suitability as precipitants. GC-MS analysis of the volatile sesquiterpenes produced by the purified enzyme under these conditions revealed that Stehi73029 produced solely Δ6-protoilludene (1) in the presence of MgCl2 with (2E,6E)-FPP as a substrate; however, addition of CaCl2 resulted in a significant switch in product profile. Instead, with CaCl2 the major sesquiterpene produced by Stehi73029 was the 1,10-cyclization product β-elemene (2), and lower levels of Δ6-protoilludene (1) and (E)-β-caryophyllene (3) were also detected, as well as minute amounts of β-selinene (5) and α-selinene (6) (Figure 1). No changes in secondary structure of Stehi73029 were observed by CD spectroscopy upon addition of Ca2+ to the enzyme, suggesting that the altered product profile was not caused by large scale structural rearrangements (Supplementary Figure 3). Subsequently, metal ion dependent product promiscuity was explored in the other four Δ6-protoilludene synthases. As shown in Figure 1, in the presence of Ca2+ all of the enzymes switched from an 1,11- to a predominantly 1,10-cyclization mechanism. Stehi25180 and Stehi64702 produced Δ6-protoilludene (1), β-elemene (2), (E)-β-caryophyllene (3), β-selinene (5) and α-selinene (6); Omp6 also produced Δ6-protoilludene (1), β-elemene (2), (E)-β-caryophyllene (3), 4,11-selinadiene (4), β-selinene (5) and α-selinene (6); and Omp7 produced low levels of Δ6-protoilludene (1), β-elemene (2), (E)-β-caryophyllene (3), β-selinene (5) and α-selinene (6). Notably, the level of sesquiterpenes detected for Omp7 in the presence of Ca2+ was significantly lower than for any of the other enzymes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Product specificity of Δ6-protoilludene synthases is perturbed in the presence of Ca2+.

In the presence of Mg2+ all Δ6-protoilludene synthases produce Δ6-protoilludene (1) via a 1,11 cyclization of (2E,6E)-FPP as a major volatile product detected by GC-MS. In the presence of Ca2+ Δ6-protoilludene synthase specificity is reduced, enabling a dual 1,11 and 1,10 cyclization. Activity and promiscuity in the presence of Ca2+ is enzyme dependent. The peak highlighted with an asterisk (*) is background siloxane. Peaks corresponding to compounds (1-6) are labelled with ticks and grid lines along the x-axis for clarity. Mass spectra of identified compounds are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

The most abundant volatile terpenes produced by the native fungal host, S. hirsutum, are derived from a 1,11 cyclization mechanism [22] (Supplementary Figure 4), and include Δ6-protoilludene (1) and (E)-β-caryophyllene (3) detected in the in vitro assays described here (Figure 1). Interestingly, S. hirsutum also produces β-elemene (2) as a major product (Supplementary Figure 4). In our previous predictive framework-guided discovery of sesquiterpene synthases from S. hirsutum, we cloned and characterized a suite of 1,11-, 1,10- and 1,6-cyclizing enzymes [22]. We did not, however, find an enzyme responsible for the production of germacrene A (which is rearranged to β-elemene (2) at high temperature). We predicted that several other putative 1,10-cyclizing sesquiterpene synthases exist in S. hirsutum, however, we were unable to clone functional forms of these genes due to challenges in predicting splice variants [22]. It is therefore unclear whether the β-elemene (2) produced by the fungal host derives instead from a series of promiscuous 1,11/1,10-cyclizing enzymes as opposed to a dedicated 1,10-cyclizing sesquiterpene synthase. Notably, the Δ6-protoilludene synthases described here are capable of a mechanistic versatility that could potentially account for the presence of at least some of the β-elemene (2) detected in the headspace of S. hirsutum cultures.

In the presence of Ca2+ Δ6-protoilludene synthases catalyze the diverse cyclization reactions shown in Scheme 1. Δ6-protoilludene (1) and (E)-β-caryophyllene (3) result from a 1,11 cyclization of (2E,6E)-FPP following metal ion mediated ionization. The intermediate trans-humulyl cation (7) may undergo a hydride shift followed by two cyclizations and a deprotonation to yield Δ6-protoilludene (1) [21, 25]. Alternatively, a direct 2,10 cyclization of the trans-humulyl cation (7) leads to (E)-β-caryophyllene (3) [26]. On the other hand, β-elemene (2), 4,11-selinadiene (4), β-selinene (5) and α-selinene (6) are derived from a 1,10 cyclization of (2E,6E)-FPP. A direct deprotonation of the intermediate (E,E)-germacradienyl cation (8) results in germacrene A; β-elemene (2) is the heat-induced Cope rearrangement product [27]. A 2,7 cyclization of the (E,E)-germacradienyl cation (8) followed by deprotonation yields 4,11-selinadiene (4) [28]. Finally, a hydride shift, followed by a 2,7 cyclization of the (E,E)-germacradienyl cation (8) and deprotonation leads to β-selinene (5) and α-selinene (6) [29]. Therefore Δ6-protoilludene synthases are capable of catalyzing simultaneously a 1,10 and a 1,11 cyclization in the presence of an alternative metal ion.

Dual 1,10 and 1,11 cyclizations have been observed upon mutation of active site residues in plant δ-selinene synthase and γ-humulene synthase [11, 30]. Additionally, mutation of a conserved T-G-G-motif increases 1,11-cyclization activity of plant germacrene A synthase [14]. Although the fungal Δ6-protoilludene synthases share this conserved motif (T202-G203-G204 in germacrene A synthase), the second glycine is replaced by a isoleucine in all cases. Interestingly, germacrene A synthase mutant G203I was inactive, suggesting that in fungal Δ6-protoilludene synthases this motif does not regulate the dual 1,10/1,11 cyclization mechanism, which instead can be mediated by binding of the divalent metal ion Ca2+.

Δ6-protoilludene synthases are catalytically functional with a range of metal ions

Sesquiterpene synthases typically bind the divalent metal cations Mg2+ and Mn2+ to ionize the pyrophosphate of (2E,6E)-FPP [17, 31–32]. However, several class I terpene synthases are catalytically functional with alternative metal ions. For example, Co2+ alters substrate and product promiscuity in insect isoprenyl diphosphate synthase [33], and some plant sesquiterpene synthases display cyclization activity in the presence of different divalent metal ions [32, 34]. In other cases, metal ions play additional roles in the activation of terpene synthases, for example, a monovalent potassium ion binding site located near the active site entrance is involved in the activation of apple α-farnesene synthase [35].

Therefore, to explore the cyclization activities of Δ6-protoilludene synthases with metal ions beyond Mg2+ and Ca2+, we incubated the purified enzymes with (2E,6E)-FPP and MnCl2, CoCl2, NiCl2, ZnCl2 or KCl. In the presence of Mn2+, Co2+ and Ni2+ all five enzymes retained activity and produced Δ6-protoilludene (1) as a major volatile sesquiterpene; Stehi73029 also produced β-elemene (2) and (E)-β-caryophyllene (3) in the presence of Mn2+ (Supplementary Figure 5). None of the enzymes were active in the presence of Zn2+ or K+, or when divalent metal ions were not added.

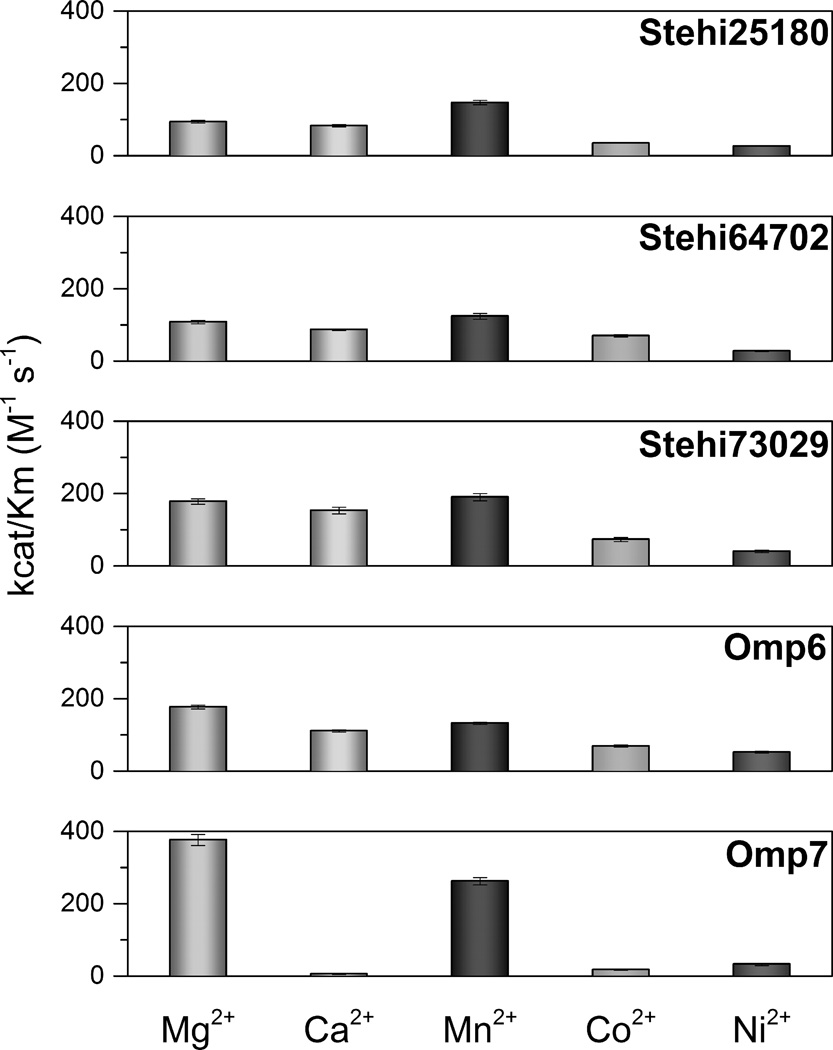

To determine whether the observed activity of Δ6-protoilludene synthases with different metal ions was catalytically relevant, we measured Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2). For all five enzymes release of PPi from (2E,6E)-FPP was most efficient in the presence of the canonical divalent metal ions Mg2+ and Mn2+; turnover rate was greatest with Mg2+. Omp7 had the highest catalytic efficiency in the presence of Mg2+ due to a greater affinity for the substrate than the other enzymes [21]. For all Δ6-protoilludene synthases catalytic efficiencies in the presence of Co2+ and Ni2+ were lower than Mg2+ or Mn2+, which can be attributed to both a reduced affinity for the substrate and a reduced turnover rate (Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, in the presence of Ca2+, Stehi73029 displayed the greatest turnover rate and overall catalytic efficiency of Δ6-protoilludene synthases, whereas Omp7 had a tenfold lower turnover rate and the lowest catalytic efficiency. However, affinity for the substrate was comparable between the two enzymes. This indicates that differences may exist in the coordination of Ca2+ at the active site of Stehi73029 and Omp7, which was intriguing because the two homologs share identical conserved DEXXD/NSE metal ion binding motifs (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 2. Catalytic efficiency of Δ6-protoilludene synthases is divalent metal ion-dependent.

Efficiency of release of PPi from (2E,6E)-FPP catalyzed by Δ6-protoilludene synthases was measured in the presence of a range of divalent metal ions (1 mM) in a coupled spectrophotometric assay. For a detailed list of kinetic parameters see Supplementary Table 2.

Metal ion concentration affects relative activity and promiscuity of Δ6-protoilludene synthases

Divalent metal ion concentration can affect the relative activity of sesquiterpene synthases, as well as product specificity [32]. Therefore, the concentration of metal ions required to reach maximum velocity for Δ6-protoilludene synthases was determined [36]. For all enzymes Mg2+ and Mn2+ were required at the lowest concentration to reach maximum velocity (Table 1). This could imply that Mg2+ and Mn2+ may be more tightly associated with the active site DEXXD/NSE motif which may lead to more efficient removal of PPi (Figure 2). However, this relationship is not apparent in the case of Ca2+, which in order to reach maximum velocity, was required at the highest concentration of the metal ions tested (Table 1). Yet, most Δ6-protoilludene synthases were more efficient with Ca2+ than with Ni2+ or Co2+ (Figure 2). Physical factors such as differences in effective atomic radii and preferred coordination geometry of the metal ions (Supplementary Table 3) may also play a role in determining not only metal ion affinity and catalytic efficiency [37], but also product promiscuity [38]. Notably, of all Δ6-protoilludene synthases, Stehi73029 required the lowest concentration of Ca2+ to reach maximum velocity, whereas Omp7 required the highest concentration (Table 1), supporting kinetic data (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1. Δ6-protoilludene synthases achieve maximum velocity at different concentrations of divalent metal ions.

Concentration of activating metal ion (mM) that achieved Vmax with a fixed concentration of (2E,6E)-FPP (100 µM) in a coupled spectrophotometric assay is defined as [A]max[36].

| [A]max (mM) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Mn2+ | Ni2+ | Co2+ | |

| Stehi25180 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.14 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.03 |

| Stehi64702 | 0.10 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.49 ± 0.05 |

| Stehi73029 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.04 |

| Omp6 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 1.44 ± 0.18 | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.09 | 0.62 ± 0.09 |

| Omp7 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 1.81 ± 0.22 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.07 |

Stehi73029 had the highest capacity for Ca2+ mediated catalysis and it was the most promiscuous of the Δ6-protoilludene synthase homologs, producing 1,11 and 1,10 cyclization products in the presence of both Ca2+ and Mn2+ (Supplementary Figure 5). To understand the relationship between Mg2+, Ca2+, and Mn2+ in triggering product promiscuity in Stehi73029, the enzyme was incubated with varying competitive ratios of divalent metal ion. Mg2+ conferred exquisite product specificity over Ca2+ and Mn2+, indicating that this is the preferred catalytic metal ion. Only in the presence of ten-fold excess Ca2+ or Mn2+ was cyclization pathway specificity altered, with a preference for 1,11 products over 1,10 products (Table 2). We observed a slight perturbation in product specificity when Ca2+ was two-fold more abundant than Mg2+; however, fidelity in 1,11 cyclization was maintained. Ca2+ and Mn2+ acted in a more cooperative manner; at a 1:1 ratio the fidelity of the 1,11 cyclization mechanism was reduced more significantly than in the presence of Mg2+. It appeared that when both Mn2+ and Ca2+ were present at various ratios, Stehi73029 could select Mn2+ over Ca2+ as the catalytic divalent ion; maintaining an overall preference for 1,11 cyclization products. However, Ca2+ did partially affect product specificity, as well as partially derail cyclization mechanism, resulting in the presence of 1,10 cyclization products. This suggests that Ca2+ may be capable of disrupting correct coordination of Mn2+ at the active site. It was not clear whether Ca2+ could compete with Mn2+ to bind at the DEXXD/NSE motif; ionization of (2E,6E)-FPP by Stehi73029 is more efficient in the presence of Mn2+ (Figure 2, Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, Omp7 has a significantly lower catalytic efficiency with Ca2+, even though sequence alignments (Supplementary Figure 6) show that Omp7 shares the same conserved DEXXD/NSE motif as Stehi73029. This raised the question whether additional metal binding sites might exist in Stehi73029.

Table 2. Metal selectivity mediates product specificity in Stehi73029.

Varying ratios of divalent metal ions (M2+) results in varying levels of 1,11 and 1,10 cyclization products. Amount of each product detected by GC-MS is represented as a percentage of the total abundance of sesquiterpenes produced, calculated from peak areas.

| M2+ | [M2+:M2+] (mM) |

Level of sesquiterpene products (%) | Ratio 1,11:1,10 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||||

| Δ6-protoilludene | β-elemene | (E)-β-caryophyllene | 4,11-selinadiene | β-selinene | α-selinene | ||||

| Mg | 10:0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mn | 10:0 | 89 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93.5 | 6.5 |

| Ca | 10:0 | 21.7 | 68.2 | 5.7 | 0 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 27.4 | 72.6 |

| Mg:Mn | 10:10 | 80.1 | 0 | 19.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Mn | 10:5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Mn | 10:1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Mn | 5:10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Mn | 1:10 | 72.9 | 9.6 | 17.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90.4 | 9.6 |

| Mg:Ca | 10:10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Ca | 10:5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Ca | 10:1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Ca | 5:10 | 97.9 | 0 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Mg:Ca | 1:10 | 67.9 | 32.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67.9 | 32.1 |

| Mn:Ca | 10:10 | 75.2 | 12.9 | 11.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 87.1 | 12.9 |

| Mn:Ca | 10:5 | 80.3 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 90.7 | 9.3 |

| Mn:Ca | 10:1 | 86.9 | 4.5 | 8.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 95.5 | 4.5 |

| Mn:Ca | 5:10 | 72.8 | 7.4 | 11.3 | 0 | 8.5 | 0 | 84.1 | 15.9 |

| Mn:Ca | 1:10 | 60.8 | 11.9 | 15.3 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 76.1 | 23.9 |

Secondary metal binding sites are involved in regulating product promiscuity in Stehi73029

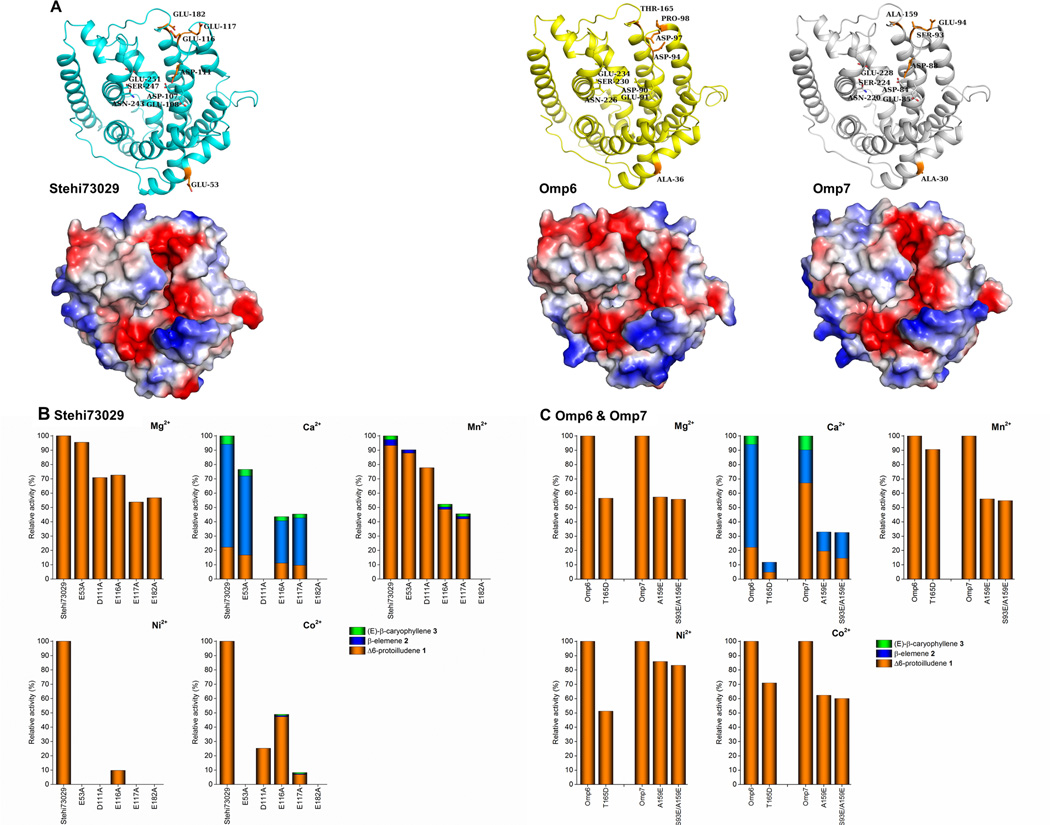

(+)-germacrene D synthase from Solidago canadensis has an additional aspartate-rich site beyond the canonical D(D/E)XX(D/E) and NSE motifs which participates in the coordination of Mg2+ [39]. To determine whether a similar accessory metal ion binding site could exist in Stehi73029, which was the most promiscuous of the five Δ6-protoilludene synthases, structural models of Stehi25180, Stehi64702, Stehi73029, Omp6 and Omp7 were created and compared (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 3. Activity and product specificity of Δ6-protoilludene synthase mutants in the presence of divalent metal ions.

(A) Structural models and electrostatic potential molecular surfaces Stehi73029, Omp6 and Omp7. Electrostatic potentials are colored blue for positive charge and red for negative charge. All enzymes share the highly conserved active site motifs DEXXD and NSE (shown as sticks). Putative surface exposed negatively charged residues located within 6Å of the opening of the active site cavity that may be involved in binding accessory divalent metal ions by are highlighted in orange (Stehi73029 residues E116, E117 and E182). Additionally, a distant surface exposed residue (Stehi73029 residue E53), and one of the conserved active site residues from the metal ion binding motif DEXXD are highlighted (Stehi73029 residue D111). Corresponding residues are shown for Omp6 and Omp7. (B + C) GC-MS analysis of sesquiterpenes produced by purified wild type (WT) enzyme and mutants in the presence of Mg2+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Ni2+ and Co2+ is shown. (B) Relative activity of WT Stehi73029 and its mutants E53A, D111A, E116A, E117A, E182A and (C) WT Omp6 and its mutant T165D and WT Omp7 and its mutants A159E and S93E/A159E is presented as a percentage (%) of activity of the WT enzyme. For each mutant the total activity is displayed as colored bars representing ratios of sesquiterpene products Δ6-protoilludene (1) (orange), β-elemene (2) (blue) and (E)-β-caryophyllene (3) (green).

The canonical DEXXD/NSE motifs were highly conserved in all cases, and no additional aspartate-rich motif was identified in the active site of the enzymes (Supplementary Figures 6 and 7). However, a negatively charged patch is located near the opening of the active site in all Δ6-protoilludene synthases, which in the case of Stehi73029, is most closely associated with the active site motif DEXXD. To investigate the role of this negatively charged patch on the catalytic and cyclization activity of Stehi73029 in the presence of different divalent metal ions, we created mutants of the enzyme. The residues constituting the active site-associated negative patch (E116, E117, E182), as well as the least essential of the residues in the conserved metal binding motif (D111) [40], and as a control, a distant surface exposed negatively charged residue (E53) were mutated to alanine.

As shown in Figure 3B, in the presence Mg2+ all Stehi73029 mutants maintained greater than 50 % relative activity and complete 1,11-cyclization fidelity. Mutation of D111 did not drastically affect cyclization activity, suggesting that Mg2+ must be sufficiently coordinated by the other aspartate-rich motif residues D107 and E108, which are positioned deeper in the active site cavity (Supplementary Figure 7) [40]. As expected, mutation of the distant surface exposed residue E53 did not influence Stehi73029 catalysis.

In the presence of Ca2+, however, activity of Stehi73029 mutants differed (Figure 3B). As with Mg2+ overall activity of the E53A mutant was mostly unchanged compared to the wild-type enzyme. On the other hand, mutants D111A and E182A were not active with Ca2+, suggesting that these residues must be critical for the coordination of Ca2+. We noted a partial restoration of activity of mutants D111A and E182A upon addition of 0.1 mM MgCl2 to the same reactions (ie. a 10:1 ratio Ca2+:Mg2+). In this case, both D111A and E182A produced Δ6-protoilludene (1) as the sole product (at 7 % and 37 % relative activity compared to activity in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2). This suggests that Mg2+ is the preferred catalytic metal ion, as described previously (Table 2). Substitution of the other glutamate residues (E116, E117) also affected cyclization activity of Stehi73029, suggesting that a different binding of Ca2+ and therefore altered coordination of the PPi moiety of (2E,6E)-FPP translates into a less favorable positioning of the substrate in the active site.

The importance of E182 for Stehi73029 activity with divalent metals other than Mg2+ is further corroborated by the fact that activity of E182A was also eliminated in the presence of Mn2+ (Figure 3B). On the other hand, substrate specificity of D111A was improved in the presence of Mn2+, implying that Mn2+ can be coordinated at D107 and E108 in a similar fashion to Mg2+. E182 may play a cooperative role in metal positioning at the DEXXD motif, directing Mn2+ to the active site. Furthermore, E116A and E117A were slightly less promiscuous in the presence of Mn2+, therefore these residues may act in concert to regulate specificity.

In the case of both Ni2+ and Co2+ activity was significantly affected in the Stehi73029 mutants (Figure 3B). As with Mn2+ and Ca2+, the E182A mutant was inactive with both metals. Activity with Ni2+ was most severely affected in almost all of the mutants. D107 and E108 in the DEXXD motif can partially rescue coordination of Co2+ in the D111A mutant. Similarly, mutants E116A and E117A are still capable of coordinating Co2+ in such a way that (2E,6E)-FPP can be cyclized at the 1,11-position with slightly reduced fidelity. Unexpectedly, the control E53A mutant lost all activity with Ni2+ and Co2+. Several additional residues are closely associated with E53 in Stehi73029 (E52, E49, Q55) that are not present in other Δ6-protoilludene synthases (Figure 3A, Supplementary Figures 6 and 7). It could be hypothesized that mutation E53A renders the surrounding negatively charged residues available as a new Co2+ and Ni2+ binding motif, leading to a series of minor conformational shifts that may inactivate the enzyme.

Secondary metal binding sites are not conserved across fungal Δ6-protoilludene synthase homologs

E182 plays a significant role in directing and/or coordinating Mn2+ and Ca2+ in the active site of Stehi73029. This residue, however, is not conserved in either Omp6 or Omp7, which have the lowest affinity for divalent metal ions other than Mg2+. In Omp6 and Omp7 the corresponding amino acids are T165 and A159, respectively (Figure 3A, Supplementary Figures 6 and 7). In an attempt to determine whether E182 was a generic “promiscuity switch” in fungal Δ6-protoilludene synthases, the two homologous residues in Omp6 and Omp7 were mutated to negatively charged amino acids aspartic acid or glutamic acid. Promiscuity did not significantly change in either Omp6 T165D or Omp7 A159E in the presence of Ca2+, in both cases a dual 1,11 and 1,10 cyclization was followed, with a slight preference for 1,11 cyclization in Omp7 A159E (Figure 3C).

In an attempt to explore whether the other residues in the negatively charged patch in Stehi73029 enhance the promiscuous behavior associated with E182, double mutant Omp7 S93E/A159E was created. S93 in Omp7 corresponds to E116 in Stehi73029, which plays a role in positioning alternative metal ions at the active site (Figure 3A and 3B, Supplementary Figures 6 and 7). Because Omp7 already shares a negatively charged residue (E94) at the same position as E117 in Stehi73029, the negative patch provided by double mutant S93E/A159E in Omp7 fully mimics the negative patch in Stehi73029. Once again, no significant change in promiscuity was observed in Omp7 S93E/A159E when incubated the presence of Ca2+. A dual 1,11/1,10 cyclization occurred, albeit with a slight preference for a 1,10 cyclization over a 1,11 cyclization mechanism (Figure 3C).

Therefore, promiscuity in metal binding and cyclization mechanism across Δ6-protoilludene synthases appear to be governed by residues beyond this negatively charged patch. In the absence of a crystal structure(s) of Δ6-protoilludene synthase with divalent metal ions coordinated at the active site, it can only be hypothesized that binding of alternative metal ions such as Ca2+ at the top of the active site cavity may lead to minute or residue-level structural rearrangements that are not detectable by CD spectroscopy (Supplementary Figure 3). This, in turn, could potentially result in a difference in the positioning of the active site lid, which is involved in defining product promiscuity of other fungal sesquiterpene synthases [41].

In order to gain further insights into sequence conservation and diversity beyond the known aspartate rich metal binding motifs of putative trans-humulyl cation (7) producing sesquiterpene synthases from all Basidiomycota, with the aim of predicting residues beyond the metal binding motifs that could be involved in maintaining specificity in Omp7, phylogenetic analyses were undertaken with close protein sequence homologs of the Δ6-protoilludene synthases. A BLAST search of Basidiomycota genomes published in the Joint Genome Institute’s Fungal Genome Database identified a total of 173 putative 1,11 cyclizing sesquiterpene synthase sequences from 23 genomes. Following manual curation to eliminate duplicates and incorrect structural gene predictions and/or pseudogenes, 43 protein sequences were aligned and an unrooted maximum likelihood phylogram was created (Supplementary Figure 8). A significant level of sequence divergence across fungal species emerged, even between closely related homologs of the Δ6-protoilludene synthases. Evolutionary conservation of the amino acid positions in the 43 identified Basidiomycota homologs was calculated using ConSurf [42] with the structural model of Stehi73029 as the input structure (Figure 4).

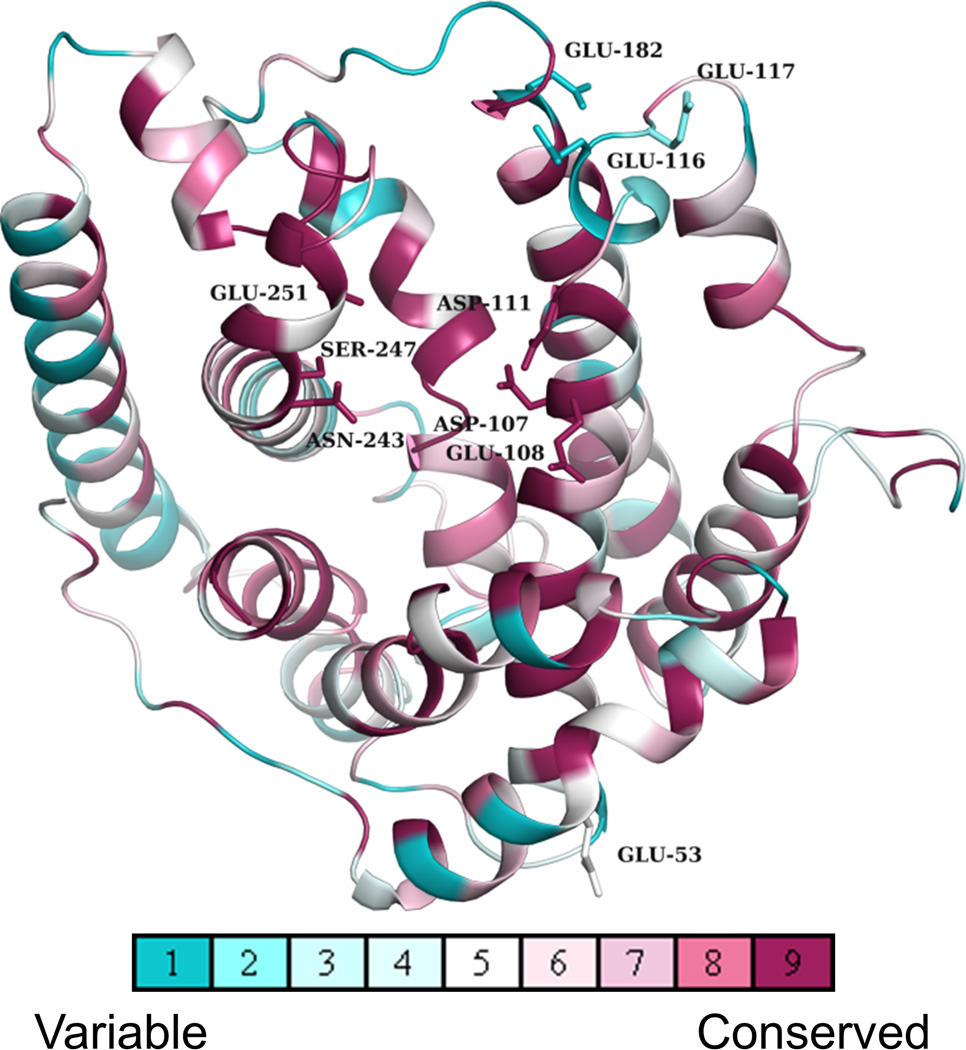

Figure 4. Putative secondary metal binding sites in Δ6-protoilludene synthase homologs are located at positions that are variable.

The evolutionary conservation of amino acids among putative trans-humulyl cation (7) producers is displayed upon a structural model of Stehi73029. The conserved active site motifs, and sites that were mutated in Stehi73029 are shown as sticks and residues are labelled. Evolutionary conservation of sites across Basidiomycota homologs is colored coded from turquoise (variable) to magenta (conserved).

At a structural level, sequence divergence is most prevalent at regions beyond the active site. As expected, amino acids lining the active site cavity of putative trans-humulyl cation (7) producers are highly conserved, indicative of a conserved catalytic function (Figure 4). Notably, there is a high degree of sequence variability at the opening of the active site; this region corresponds to the secondary metal binding site identified in Stehi73029 (Figure 3A, Supplementary Figures 6 and 7). In Stehi73029, this site is involved in binding and directing various metal ions, which in turn regulates product promiscuity and switching of cyclization mechanism (Figure 3B). This is, however, not the case in the closely related homologues Omp6 and Omp7, suggesting that additional, distant residues must be involved in determining product promiscuity. However, it is not possible to deduce the nature of these sites by sequence alignment and modelling alone; determining accessory residues involved in (de)stabilizing the initial cyclization mechanism would require a full site saturation mutagenesis of the entire protein. Therefore, a potential diversity in metal binding of other putative trans-humulyl cation (7) producers from other diverse fungal species remains to be explored.

Fungal cellular environment may play a role in directing sesquiterpenoid biosynthesis

Calcium signaling plays a major role in eukaryotic cell physiology; as such Ca2+ pumps, binding proteins, transporters and channels are highly conserved among fungi. Extensive studies of Ca2+-responsive signaling pathways in the model fungal system S. cerevisiae have revealed complex and intricate regulatory circuits that respond to external stimuli and stressors and play important roles in fungal virulence (reviewed in: [45]). To preserve correct function of Ca2+ dependent signal transduction pathways, cytosolic Ca2+ levels are maintained at a low-to-sub µM range, while orders of magnitude higher levels accounting for >90% of total cellular Ca2+ are stored in fungal acidic vacuoles (~30 µM free and ~ 3 mM polyphosphate bound Ca2+ in yeast vacuoles) [44–45]. Ca2+ is only transiently released from the vacuole in response to specific stimuli and stressors (e.g. hyposomotic conditions, Mg2+ starvation, membrane stress as the result of environmental conditions and microbial toxin attack), and is quickly returned to physiological levels [45].

Therefore, to explore whether the Ca2+-triggered switch of cyclization activity of Δ6-protoilludene synthases observed in vitro may be of physiological relevance by altering the volatile terpenoid profile produced by the fungus, we expressed Stehi73029 and Omp7 in S. cerevisiae. This yeast is the closest genetically tractable host for expression of these enzymes and conditions are known that lead to a transient increase of cytosolic Ca2+ levels [44–45].

The relative abundance of volatile sesquiterpenes detected in the headspace of yeast cultures expressing Omp7 and Stehi73029 was ten-fold greater than that detected in recombinant E. coli strains, likely due to codon usage and other preferences for cellular environments (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 9). Notably, both Omp7 and Stehi73029 were more promiscuous when expressed in yeast than when expressed in E. coli, producing Δ6-protoilludene (1) as the major product, as well as other minor sesquiterpene products derived from a 1,11 cyclization mechanism. Whether or not this is due to levels of overexpression of the enzymes is not known. Stehi73029 also produced the 1,10 cyclization products γ-elemene and 4,11-selinadiene (4), while Omp7 did not produce any 1,10 cyclization products; a similar trend to that observed when the two enzymes were expressed in E. coli. Additionally, some peaks which could not be reliably assigned using the available libraries, had a m/z of 220 or 222, suggesting that a moonlighting P450(s) from the heterologous host is capable of oxygenating the sesquiterpene scaffold(s).

To induce an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels in yeast cells expressing Omp7 and Stehi73209, 50 mM CaCl2 was included in the growth medium as described in [44]. However, under these conditions, yeast cells expressing Stehi73029 had almost the same sesquiterpene profile as cells not subjected to Ca2+ shock, which included both 1,11 and 1,10 cyclization products (Supplementary Figure 9). Two minor new 1,10-cyclization sesquiterpene peaks (γ-elemene and 4,11-selinadiene (4)) were observed in the headspace of yeast cells expressing Omp7 upon addition of Ca2+ (Supplementary Figure 9).

These data suggest that the nature of the cellular environment has a general effect on the cyclization activity of Omp7 and Stehi73029, but that addition of extracellular Ca2+ to recombinant yeast cultures expressing the enzymes likely is insufficient to maintain the sustained elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels that would be required to detect significant changes in the accumulation of volatile sesquiterpenes in the culture headspace. Other stressors and stimuli may be required to elicit more drastic and sustained changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels to trigger synthesis of the 1,10-cylization product germacrene A (β-elemene (2)) by Stehi73209. Identification of such conditions for S. cerevisiae is beyond the scope of this study. Basidiomycota such as Stereum hirsutum are exposed to various membrane stresses, including microbial attacks on nutrient prospecting mycelia and insect and nematode attacks on fruiting bodies, which trigger Ca2+ release from vacuoles and may shift volatile sesquiterpene production in response. Herbivore or pathogen infection induced volatile sesquiterpene (including germacrene and farnesene) production as signaling and defense mechanism are well known in plants [46–47] and comparable mechanisms may also be used by higher fungi.

Conclusions

This work has shown that certain fungal Δ6-protoilludene synthases catalyze a dual 1,10 and 1,11 cyclization in the presence of different divalent metal ions. This mechanistic diversity is enzyme-dependent; even between closely related homologs. Predicting which enzymes would be more inclined to switch cyclization mechanism, or the factors that cause promiscuity cannot be achieved by sequence analyses. These findings provide insights into the evolutionary divergence of seemingly very closely related fungal sesquiterpene synthases, which is particularly relevant for the design of efficient biosynthetic systems to produce pharmaceutically relevant trans-humulyl cation (7) derived sesquiterpenes. Considering the importance of Ca2+ signaling in fungal cell physiology, the discovery that Ca2+ switches the cyclization mechanism of some fungal Δ6-protoilludene synthases opens the possibility that volatile sesquiterpenes may be play a role in signaling and/or defense in fungi which deserves further investigation.

Experimental Section

Protein purification

Prior to purification all glassware was extensively washed and rinsed with nitric acid (10 %) and reagent grade water (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to exclude extraneous metal ions. All buffers were prepared using reagent grade water. Recombinant E. coli cell pellets were resuspended in Buffer A (50 mM Tris.HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) and were lysed by sonication. Soluble proteins were separated from the cell slurry by centrifugation (15000 g, 30 min). The His6-tagged proteins were bound to a HisTrap FF column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) in Buffer A, and were eluted in Buffer B (50 mM Tris.HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 7.5). Following overnight dialysis into Buffer C (50 mM Tris.HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 % glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5), the proteins were separated on a S200 10/300 GL size exclusion column. Following purification, proteins were extensively dialyzed against EDTA (5 mM) and reagent grade water to ensure no metal ions were present prior to all further experiments.

Sampling and GC-MS analysis of sesquiterpene production

In vitro assays with purified sesquiterpene synthases were conducted in Buffer D (50 mM Tris.HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) supplemented with MgCl2, CaCl2, MnCl2, NiCl2, CoCl2, ZnCl2 or KCl (10 mM) in a final reaction volume of 100 µL. Sesquiterpene synthases (10 µg) were incubated with (2E,6E)-FPP (2 µM) in a sealed glass vial for 16 hours at 21 °C. In all cases a negative control (reaction mixture without supplemented metal ions) was conducted to confirm that no extraneous metal ions were present in the system. The headspace of the reaction vessels was sampled for 10 min by a solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fiber followed by GC-MS analysis. GC-MS was conducted on an HP GC 7890A chromatograph coupled to an anion-trap mass spectrometer HP MSD triple axis detector (Agilent Technologies). Compounds were separated and mass spectra were scanned as described previously [22]. The retention indices and mass spectra of peaks were compared to reference spectra in the terpene libraries available from MassFinder 4 [43] and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standard reference database.

Kinetic characterization of sesquiterpene synthases

The kinetic parameters of sesquiterpene synthases were determined using the PiPer Pyrophosphate enzyme-coupled spectrophotometric assay (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) [21–22]. A stopped time point assay was conducted to prevent interference from the MgCl2 (5 mM) in the provided assay reaction buffer. Prior to mixing with the assay kit, sesquiterpene synthases (10 µg) were incubated with a range of concentrations of (2E,6E)-FPP (1-100 µM) in Buffer D supplemented with a fixed concentration of divalent metal ion (1 mM), in a total reaction volume of 100 µl. Reactions were stopped by rapid heat inactivation (boiling for 5 mins) at set time points (0-60 mins enzyme reaction times). Control reactions without enzyme, without substrate, and without metal ion were conducted, and all reactions were performed in triplicate. Mixtures were cooled to room temperature and the release of pyrophosphate (PPi) at each time point was measured by incubating with the PiPer Pyrophosphate assay kit for 30 mins before spectrophotometric measurements were taken. PPi release was compared to a standard curve of known PPi concentration, and kinetic parameters were determined by nonlinear regression analysis in Origin 9.1. To measure [A]max, assays were conducted in the same manner using a fixed concentration of (2E,6E)-FPP (100 µM) and a range of concentrations of divalent metal ion (0.01 – 10 mM). [A]max is defined as the concentration of activating metal ion required to achieve Vmax, as described elsewhere [36].

Molecular biology, bioinformatics and circular dichroism spectroscopy methods are available as Supplemental Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelwen Peng, Arnaud Batchou and Ilya Baranov for assistance with cloning and purifying Stehi73029 mutants. Chris Flynn and Sarah Perdue subcloned the yeast expression vectors pESC-Stehi73029 and pESC-Omp7. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant GM080299 (to C.S-D).

References

- 1.Starks CM, Back K, Chappell J, Noel JP. Science. 1997;277(5333):1815–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesburg CA, Zhai G, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Science. 1997;277(5333):1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vedula LS, Jiang J, Zakharian T, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;469(2):184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vedula LS, Zhao Y, Coates RM, Koyama T, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;466(2):260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gennadios HA, Gonzalez V, Di Costanzo L, Li A, Yu F, Miller DJ, Allemann RK, Christianson DW. Biochemistry. 2009;48(26):6175–6183. doi: 10.1021/bi900483b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-Gallego F, Agger SA, Abate-Pella D, Distefano MD, Schmidt-Dannert C. ChemBioChem. 2010;11(8):1093–1106. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faraldos JA, Miller DJ, Gonzalez V, Yoosuf-Aly Z, Cascon O, Li A, Allemann RK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(13):5900–5908. doi: 10.1021/ja211820p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen M, Al-lami N, Janvier M, D'Antonio EL, Faraldos JA, Cane DE, Allemann RK, Christianson DW. Biochemistry. 2013;52(32):5441–5453. doi: 10.1021/bi400691v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinedo C, Wang CM, Pradier JM, Dalmais B, Choquer M, Le Pecheur P, Morgant G, Collado IG, Cane DE, Viaud M. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3(12):791–801. doi: 10.1021/cb800225v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li JX, Fang X, Zhao Q, Ruan JX, Yang CQ, Wang LJ, Miller DJ, Faraldos JA, Allemann RK, Chen XY, Zhang P. Biochem. J. 2013;451(3):417–426. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little DB, Croteau RB. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;402(1):120–135. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kollner TG, Schnee C, Gershenzon J, Degenhardt J. Plant Cell. 2004;16(5):1115–1131. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshikuni Y, Ferrin TE, Keasling JD. Nature. 2006;440(7087):1078–1082. doi: 10.1038/nature04607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez V, Touchet S, Grundy DJ, Faraldos JA, Allemann RK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(14):14505–14512. doi: 10.1021/ja5066366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhagen BT, O'Maille PE, Noel JP, Chappell J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(26):9826–9831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koksal M, Jin Y, Coates RM, Croteau R, Christianson DW. Nature. 2011;469(7328):116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature09628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cane DE, Xue Q, Fitzsimons BC. Biochemistry. 1996;35(38):12369–12376. doi: 10.1021/bi961344y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham WR. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001;8(6):583–606. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraga BM. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013;30(9):1226–1264. doi: 10.1039/c3np70047j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quin MB, Flynn CM, Schmidt-Dannert C. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31(10):1449–1473. doi: 10.1039/c4np00075g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wawrzyn GT, Quin MB, Choudhary S, Lopez-Gallego F, Schmidt-Dannert C. Chem. Biol. 2012;19(6):772–783. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quin MB, Flynn CM, Wawrzyn GT, Choudhary S, Schmidt-Dannert C. ChemBioChem. 2013;14(18):2480–2491. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quin MB, Wawrzyn G, Schmidt-Dannert C. Acta Crystallogr. F. 2013;69(Pt 5):574–577. doi: 10.1107/S1744309113010749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller DJ, Allemann RK. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29(1):60–71. doi: 10.1039/c1np00060h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zu L, Xu M, Lodewyk MW, Cane DE, Peters RJ, Tantillo DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(28):11369–11371. doi: 10.1021/ja3043245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erkel G, Anke T. In: Biotechnology: products from basidiomycetes. Kleinkauf H, von Döhren H, editors. Weinheim: VCH Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faraldos JA, Wu S, Chappell J, Coates RM. Tetrahedron. 2007;63(32):7733–7742. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pino JA, Marbot R, Vazquez C. J. Agr. Food. Chem. 2002;50(21):6023–6026. doi: 10.1021/jf011456i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams HJ, Sattler I, Moyna G, Scott AI, Bell AA, Vinson SB. Phytochemistry. 1995;40(6):1633–1636. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00577-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steele CL, Crock J, Bohlmann J, Croteau R. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273(4):2078–2089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rynkiewicz MJ, Cane DE, Christianson DW. Biochemistry. 2002;41(6):1732–1741. doi: 10.1021/bi011960g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kollner TG, Schnee C, Li S, Svatos A, Schneider B, Gershenzon J, Degenhardt J. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283(30):20779–20788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frick S, Nagel R, Schmidt A, Bodemann RR, Rahfeld P, Pauls G, Brandt W, Gershenzon J, Boland W, Burse A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(11):4194–4199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221489110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picaud S, Brodelius M, Brodelius PE. Phytochemistry. 2005;66(9):961–967. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green S, Squire CJ, Nieuwenhuizen NJ, Baker EN, Laing W. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(13):8661–8669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807140200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott DJ, da Costa BM, Espy SC, Keasling JD, Cornish K. Phytochemistry. 2003;64(1):123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Needham JV, Chen TY, Falke JJ. Biochemistry. 1993;32(13):3363–3367. doi: 10.1021/bi00064a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben-David M, Wieczorek G, Elias M, Silman I, Sussman JL, Tawfik DS. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425(6):1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prosser I, Altug IG, Phillips AL, Konig WA, Bouwmeester HJ, Beale MH. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;432(2):136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seemann M, Zhai G, de Kraker JW, Paschall CM, Christianson DW, Cane DE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124(26):7681–7689. doi: 10.1021/ja026058q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez-Gallego F, Wawrzyn GT, Schmidt-Dannert C. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2010;76(23):7723–7733. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01811-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashkenazy H, Erez E, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W529–W533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joulain D, König WA. The atlas of spectral data of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons. Hamburg: EB-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forster C, Kane PM. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(49):38245–38253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cunningham KW. Cell Calcium. 2011;50(2):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clavijo McCormick A, Unsicker SB, Gershenzon J. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17(5):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arimura G, Huber DP, Bohlmann J. Plant J. 2004;37(4):603–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2003.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.