Abstract

Plant stem cells give rise to all tissues and organs and also serve as the source for plant regeneration. The organization of plant stem cells has undergone a progressive change from simple to complex during the evolution of vascular plants. Most studies on plant stem cells have focused on model angiosperms, the most recently diverged branch of vascular plants. However, our knowledge of stem cell function in other vascular plants is limited. Lycophytes and euphyllophytes (ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms) are two existing branches of vascular plants that separated more than 400 million years ago. Lycophytes retain many of the features of early vascular plants. Based on genome and transcriptome data, we identified WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX (WOX) genes in Selaginella kraussiana, a model lycophyte that is convenient for in vitro culture and observations of organ formation and regeneration. WOX genes are key players controlling stem cells in plants. Our results showed that the S. kraussiana genome encodes at least eight members of the WOX family, which represent an early stage of WOX family evolution. Identification of WOX genes in S. kraussiana could be a useful tool for molecular studies on the function of stem cells in lycophytes.

Keywords: Selaginella kraussiana, lycophyte, stem cell, WOX, regeneration, vascular plants

Introduction

Stem cells are characterized by their ability to self-renew in an undifferentiated state and their potential to differentiate into functional cells (Jaenisch and Young, 2008; Lander, 2009). All plant organs are derived from stem cells, and stem cells are also important in plant regeneration (Sugimoto et al., 2011; Xu and Huang, 2014). In angiosperms, stem cells are organized in a special environment; that is, the stem cell niche within the meristem (Scheres, 2007; Aichinger et al., 2012). Genes in the WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX (WOX) family encode the key controllers of stem cell niche in many plant species. The WOX family homeobox proteins can be divided into three clades according to the time of their appearance during plant evolution: the ancient clade, the intermediate clade, and the WUS clade (Haecker et al., 2004; van der Graaff et al., 2009). The specification and organization of stem cells have become increasingly complex during the evolution of vascular plants, accompanied by increased complexity of WOX genes in diverse stem cell niches (Aichinger et al., 2012). To fully understand the complexities of stem cell activity, it would be useful to understand how stem cells functioned in the early evolution of vascular plants, as this may provide an evolutionary view of plant stem cells and stem cell niches.

More than 400 million years ago, the appearance of vascular plants was an important step in evolution during the colonization of land by plants (Bennici, 2007, 2008; Banks, 2009). Since then, vascular plants have diverged into several lineages, only two of which survive today; the lycophytes such as Selaginella (spikemosses), and the euphyllophytes consisting of monilophytes (ferns), gymnosperms, and angiosperms (Figure 1A; Raubeson and Jansen, 1992; Duff and Nickrent, 1999; Qiu and Palmer, 1999; Pryer et al., 2001; Qiu et al., 2007; Banks, 2009; Banks et al., 2011; Kenrick and Strullu-Derrien, 2014). Many lycophytes retain the typical features of early vascular plants, and therefore, are suitable for studies on the early evolution of vascular plants. For example, lycophytes have a simple and bifurcating apical meristem at the shoot and root tips (i.e., dichotomous branching), which is representative of early vascular plants during evolution (Banks, 2009). The genome of Selaginella moellendorffii, a model plant of lycophytes, was sequenced (Banks et al., 2011), and this greatly improves our knowledge on lycophytes. Identification of WOX family genes in S. moellendorffii suggests that lycophytes do not have the WUS clade (Deveaux et al., 2008; Mukherjee et al., 2009; van der Graaff et al., 2009).

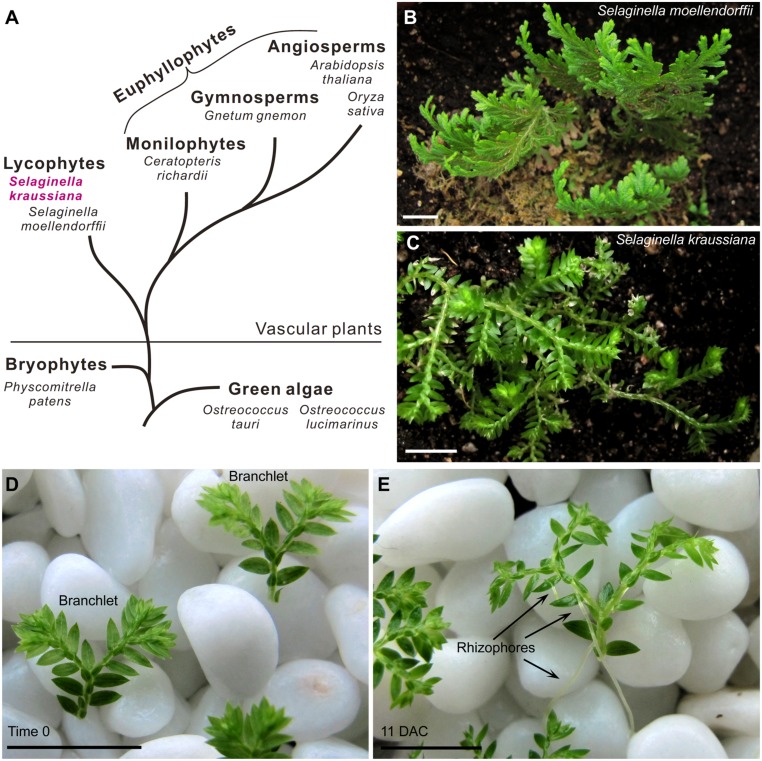

FIGURE 1.

Selaginella kraussiana as a model plant for studies on lycophytes. (A) Simplified evolutionary route of green plants, showing two existing branches of vascular plants; lycophytes and euphyllophytes. (B,C) Phenotypes of S. moellendorffii (B) and S. kraussiana (C). Note that the stem of S. moellendorffii is upright (B), while that of S. kraussiana is prostrate (C). (D,E) In vitro culture system of S. kraussiana. Detached branchlets of S. kraussiana were cultured on wet stones at time 0 (D) and 11 DAC (E). Growth of rhizophores that bear roots could be observed (E). Scale bars, 1 cm in (B–E).

Selaginella kraussiana, another model lycophyte, is easy to culture in vitro and suitable for studies on stem cells and regeneration. In this study, we identified WOX genes in S. kraussiana and analyzed their expression patterns in tissues based on genome and transcriptome data.

Results

In Vitro Culture System of S. kraussiana

Selaginella is a lycophyte lineage that separated from the euphyllophytes more than 400 million years ago (Figure 1A; Kenrick and Crane, 1997; Banks, 2009). Several species of Selaginella have been used to study different aspects of development. The stem phenotypes of Selaginella species are generally characterized by a prostrate or upright growth habit (Rost et al., 1997). S. moellendorffii has an upright stem (Figure 1B), and its genome has been sequenced (Banks et al., 2011). Different from S. moellendorffii, S. kraussiana is another commonly used species that has a typical prostrate stem (Figure 1C; Harrison et al., 2005; Floyd and Bowman, 2006; Prigge and Clark, 2006; Harrison et al., 2007; Otreba and Gola, 2011; Sanders and Langdale, 2013).

Compared with S. moellendorffii, S. kraussiana is more readily cultured in vitro and more amenable to morphological observations (Sanders and Langdale, 2013). In our conditions, the detached distal part of S. kraussiana seedlings with one or two branches grows readily on wet stones with water (Figure 1D). This growth method provides a humid environment that allows the survival of detached branchlets and also provides a physical support for stem, rhizophore, and root development. The rhizophore is a root-bearing organ in Selaginella. The detached S. kraussiana branchlets can grow continuously on the wet stones, producing more dichotomous shoot branches and rhizophores at the Y-shaped branch junctions (Figure 1E). In contrast, it is difficult to culture detached tissues of S. moellendorffii in vitro, and difficult to induce these tissues to form rhizophores.

Organ Formation and Cell Fate Transition in S. kraussiana

Using the in vitro culture system, S. kraussiana is suitable for studying organ formation and regeneration. The rooting process was clearly observed (Figures 2A–E; Otreba and Gola, 2011). In detached S. kraussiana branchlets, a rhizophore primordium was observed at the dorsal angle meristem located at the Y-shaped junction of dichotomous branching 2 days after culture (DAC; Figures 2A,B). Rhizophores continued to elongate (Figures 2C,D), and at 5 DAC the distal portion of the rhizophores started to bend (Figure 2D), indicating that their tips grew in response to gravity. The rhizophores continued to grow and produced bifurcating root tips (Figure 2E).

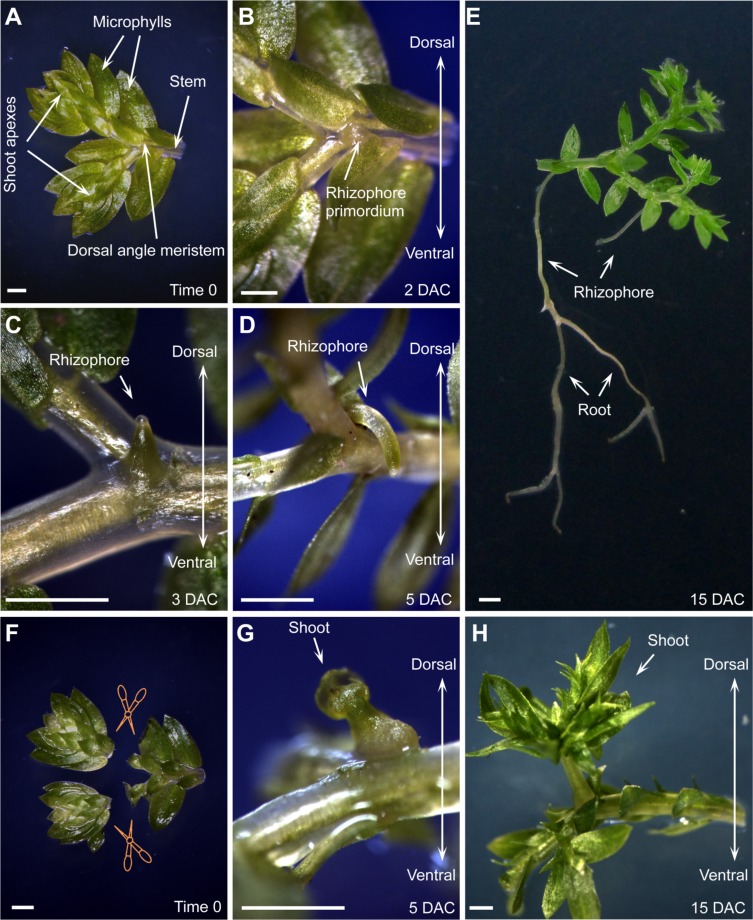

FIGURE 2.

Organ formation and regeneration in S. kraussiana. (A–D) In vitro culture of S. kraussiana, showing rhizophore growth from detached branchlets at time 0 (A), 2 DAC (B), 3 DAC (C), and 5 DAC (D). Note that rhizophore primordium was observed from the dosal angle meristem at 2 DAC (B). (E) Root formation from rhizophore. Note that the newly formed roots could bifurcate continuously. (F–H) Regeneration of shoot at angle meristem after excision of shoot apexes from branchlets. Shown are time-0 (F), 5-DAC (G), and 15-DAC (H) branchlets. Note that the regenerated shoot apex was observed from the dosal angle meristem at 5 DAC (G). Detached branchlets were cultured on wet stones and removed to an agar plate to take pictures. Scale bars, 1 mm in (A–H).

We also analyzed the regenerative ability of S. kraussiana in the in vitro culture system. It was reported that Selaginella has the ability to change the fate of angle meristem cells from rhizophore to shoot upon injury of the shoot apexes (Williams, 1937; Webster and Steeves, 1964; Webster, 1969; Wochok and Sussex, 1975). We repeated this experiment by excision of the two shoot apexes from the detached branchlet (Figure 2F). After excision, the new shoot apex regenerated within 5 DAC from the dorsal angle meristem (Figure 2G), where the rhizophore primordium usually grew in non-excised branchlets (Figures 2B–D). This suggests that the fate of stem cells within the angle meristem was changed from rhizophore or root to shoot during regeneration. The regenerated shoot apex grew continuously to form a seedling (Figure 2H). Overall, these observations confirmed that S. kraussiana is a good system for studying organ formation and regeneration.

Identification of WOX Genes from Genome and Transcriptome Sequencing Data of S. kraussiana

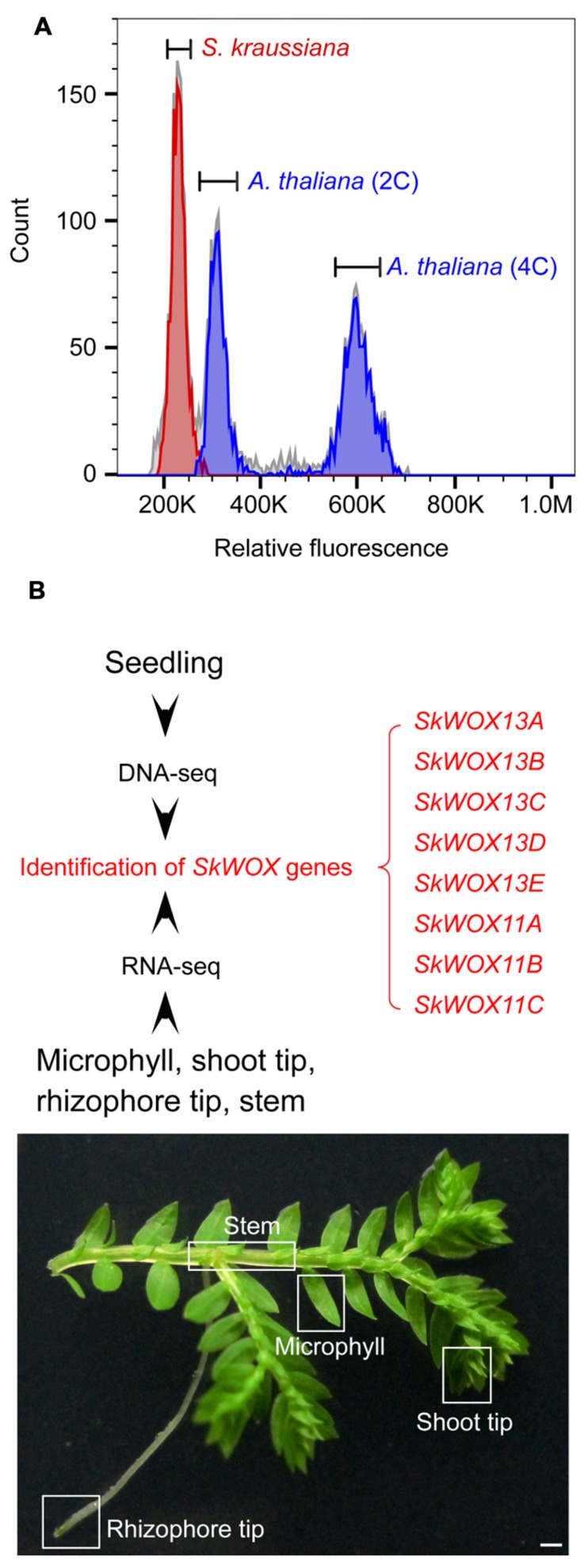

To estimate the size of the S. kraussiana genome, we performed a flow cytometry analysis. The data showed that the genome of S. kraussiana is smaller than that of Arabidopsis thaliana (Figure 3A), consistent with the previous study (Little et al., 2007). We conducted a DNA-seq analysis of the S. kraussiana genome (Figure 3B). The draft assembly of contigs confirmed that the S. kraussiana genome is smaller than that of A. thaliana and similar to the length of the genome of S. moellendorffii (The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000; Banks et al., 2011).

FIGURE 3.

Genome and transcriptome analyses of S. kraussiana. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of genome size of S. kraussiana. Genome size of S. kraussiana (red peak, %CV = 4.74) was estimated using the internal reference standard Arabidopsis thaliana (indigo peaks: 2C, %CV = 4.81; 4C, %CV = 3.66). (B) DNA-seq and RNA-seq analyses of S. kraussiana. Genomic DNA from seedlings was used for DNA-seq and four different tissues were used for RNA-seq. Eight SkWOX genes (SkWOX13A to E and SkWOX11A to C) were identified.

To analyze the transcriptome of S. kraussiana, we performed an RNA-seq analysis using four different tissues: microphyll, shoot tip, rhizophore tip, and stem (Figure 3B). Since WOX genes are key regulators of stem cells in plants, we identified genes encoding members of the WOX family in S. kraussiana (SkWOX genes). Based on our DNA-seq and RNA-seq data, we identified eight genes predicted to encode a homeodomain similar to that of the WOX family proteins (Figure 3B; Table 1). We named the eight candidate SkWOX genes SkWOX13A–E and SkWOX11A–C according to the protein sequence similarity of their homeodomains to those of A. thaliana WOX (AtWOX) proteins. The cDNA or CDS sequences of the eight SkWOX genes were further confirmed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using total RNA from whole seedlings.

Table 1.

Accession numbers of projects/sequences used in this study.

| Projects/sequences | Deposition | Accession number |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Shotgun project (DNA-seq, Draft assembly)∗ | DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank | LDJE00000000 |

| RNA-seq | GEO | GSE69388 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX11A | GenBank | KR870323 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX11B | GenBank | KR870324 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX11C | GenBank | KR870325 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX13A | GenBank | KR870326 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX13B | GenBank | KR870327 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX13C | GenBank | KR870328 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX13D | GenBank | KR870329 |

| BankIt1826187 skWOX13E | GenBank | KR870330 |

∗The version described in this paper is version LDJE01000000.

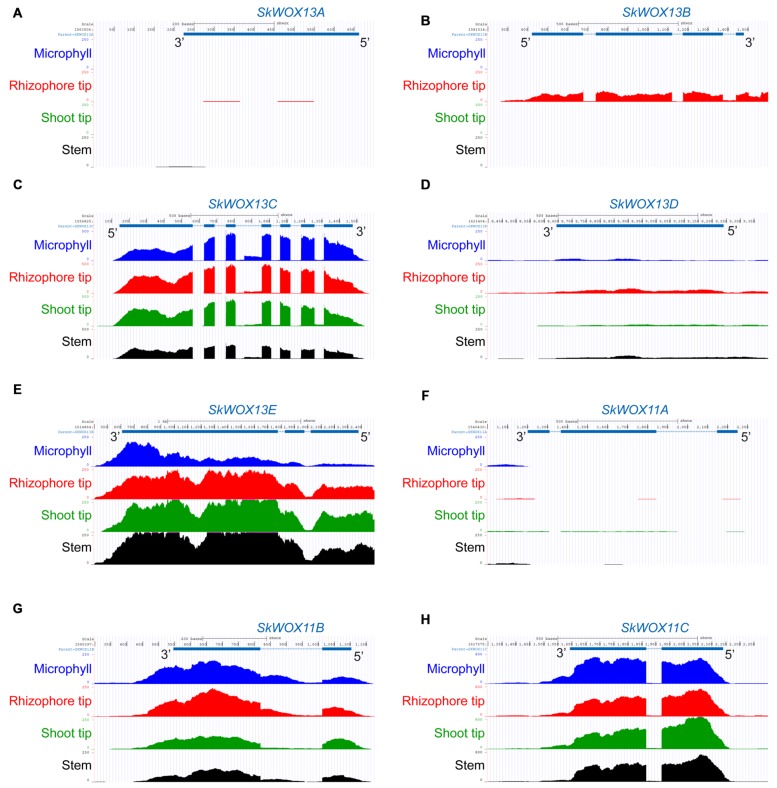

The predicted transcriptional profiles of SkWOX genes showed diverse patterns in the four tissues based on the RNA-seq data (Figures 4A–H). SkWOX13A and SkWOX11A were barely expressed in the tested tissues (Figures 4A,F), and there were low transcript levels of SkWOX13D in all tissues tested (Figure 4D). SkWOX13C, SkWOX13E, SkWOX11B, and SkWOX11C showed relatively high transcript levels in all four tissues (Figures 4C,E,G,H). Interestingly, SkWOX13B was preferentially expressed at the rhizophore tip (Figure 4B). These data suggested that each of the SkWOX genes may play specific role(s) in different tissues.

FIGURE 4.

Predicted expression profiles of SkWOX genes in S. kraussiana. (A–H) RNA-seq analyses of expression patterns of WOX genes in S. kraussiana: SkWOX13A (A), SkWOX13B (B), SkWOX13C (C), SkWOX13D (D), SkWOX13E (E), SkWOX11A (F), SkWOX11B (G), and SkWOX11C (H). Peaks indicate RNA-seq reads aligned to the corresponding gene loci.

Evolution of WOX Family Genes in Plants

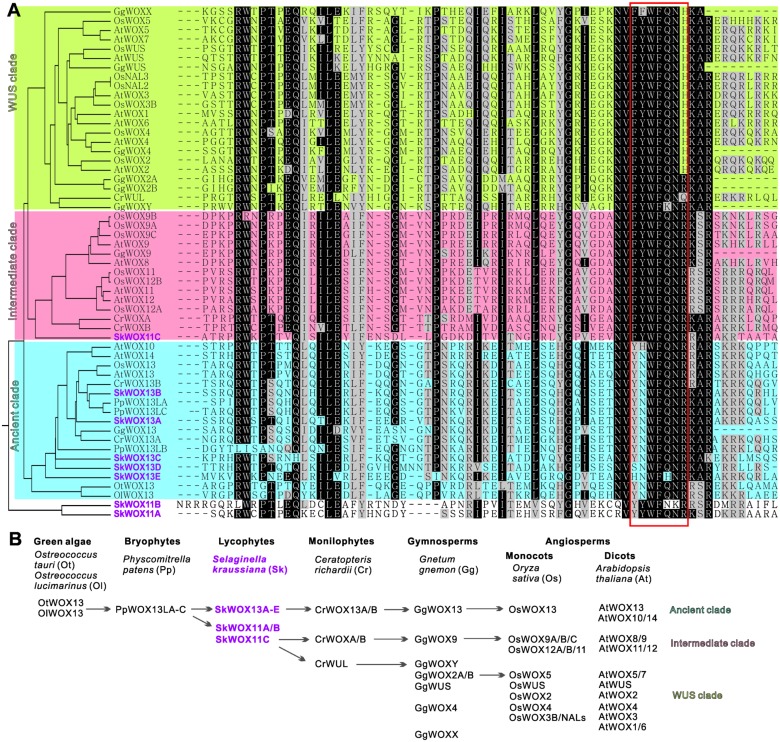

To analyze the possible evolutionary history of the WOX family, we aligned the homeodomains of SkWOX proteins against the WOX homeodomains from the green algae Ostreococcus tauri (OtWOX13) and Ostreococcus lucimarinus (OlWOX13), the bryophyte/moss Physcomitrella patens (PpWOXs), the monilophyte/fern Ceratopteris richardii (CrWOXs), the gymnosperm Gnetum gnemon (GgWOXs), and the angiosperms Oryza sativa (OsWOXs) and A. thaliana (AtWOXs) (Figure 5A; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Nardmann and Werr, 2012, 2013; Sakakibara et al., 2014). Previous studies have suggested that particular peptide sequences in the WOX homeodomain can distinguish the three clades of WOX proteins (red box in Figure 5A): YNWFQNR for the ancient clade, FYWFQNR for the intermediate clade, and FYWFQNH for the WUS clade (Nardmann and Werr, 2012; Zeng et al., 2015).

FIGURE 5.

Evolution of WOX family. (A) Alignment of WOX homeodomains from different model plants. Phylogenetic analysis of homeodomain sequences was conducted using MEGA3.0 (Kumar et al., 2004). Protein sequences were obtained from published bioinformatics data (Haecker et al., 2004; Mukherjee et al., 2009; van der Graaff et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010; Nardmann and Werr, 2012, 2013; Lian et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2015). Red box indicates sequence for classification of three clades. (B) Possible evolutionary route of WOX family genes.

Green algae and mosses only have the ancient clade of WOX genes, and moss WOX genes (PpWOX13Ls) have been shown to play a role in apical stem cell formation and regeneration (Mukherjee et al., 2009; Sakakibara et al., 2014). Our data showed that S. kraussiana has at least five ancient-clade WOX genes, SkWOX13A–E (Figures 5A,B).

Consistent with previous genomic studies on S. moellendorffii (Mukherjee et al., 2009; van der Graaff et al., 2009; Lian et al., 2014), our data showed that the genome of S. kraussiana also encodes WOX proteins in the intermediate clade (Figures 5A,B). SkWOX11C has a FYWFQNR sequence in its homeodomain, typical of the intermediate clade. Interestingly, in S. kraussiana there is a lycophyte-specific clade of WOX proteins, SkWOX11A and B, which have a YYWFQNR (or YYWFNKR) sequence that appears to be transitional between the ancient (YNWFQNR) and the intermediate (FYWFQNR) clades (Figures 5A,B). Based on overall homeodomain sequence similarity, SkWOX11A/B separated from other WOX proteins in all the species tested in this study (Figure 5A), suggesting that this clade may have evolved far apart from the trunk road of the WOX family after they separated from SkWOX11C.

The S. kraussiana genome does not encode WUS-clade genes. The fern C. richardii contains WOX members similar to WUS-clade proteins, such as CrWUL (Nardmann and Werr, 2012). Sequence analysis showed that the CrWUL protein from C. richardii and GgWOXY and GgWOX2A/B from the gymnosperm G. gnemon show high sequence similarity to WUS-clade proteins (Figure 5A). However, none of these proteins contain the WUS-clade sequence FYWFQNH in the homeodomain (Figure 5A; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Nardmann and Werr, 2012, 2013; Zeng et al., 2015). Instead of FYWFQNH, GgWOXY and GgWOX2A/B have an intermediate sequence FYWFQNR (Figure 5A). This suggests that CrWUL, GgWOXY, and GgWOX2A/B might represent a transitional evolutionary stage from intermediate to WUS-clade proteins, although these proteins are usually included in the WUS clade (Figures 5A,B; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Nardmann and Werr, 2012, 2013; Zeng et al., 2015). The WUS-clade genes have further evolved in gymnosperms and angiosperms (Figures 5A,B) (Mukherjee et al., 2009; Nardmann et al., 2009; van der Graaff et al., 2009; Lian et al., 2014).

Discussion

Lycophytes retain many features of vascular plants at the early stage of landing, and therefore, are useful for understanding the early evolution of vascular plants (Banks, 2009). S. moellendorffii and S. kraussiana are two commonly used lycophyte model plants that differ according to their stem phenotype (typical upright and prostrate stems, respectively). Both of them have merits for studies on lycophytes. Compared with S. moellendorffii, S. kraussiana has several advantages for studying organ formation and stem cell functions. First, S. kraussiana grows rapidly and is easy to culture in vitro. Second, it is easy to trace rhizophore and root development in S. kraussiana. Third, it is easy to observe the fate transition of stem cells during organ regeneration in S. kraussiana.

The genome sequence of S. moellendorffii has been reported previously (Banks et al., 2011). This genomic information has greatly improved our understanding of the evolution of the plant kingdom. In this study, we provided raw data of DNA-seq of the S. kraussiana genome and RNA-seq of four different S. kraussiana tissues (Table 1). These sequencing data provide a useful tool to study the developmental regulation of S. kraussiana using a molecular approach.

The WOX genes have evolved from ancient to intermediate to WUS clades, accompanied by the evolution of stem cell function in plants (Haecker et al., 2004; Mukherjee et al., 2009; van der Graaff et al., 2009; Aichinger et al., 2012; Lian et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2015). The WOX family could be a useful tool for studying stem cells in plants. Green algae and mosses only have the ancient clade. Our data from S. kraussiana and previous studies in S. moellendorffii (Deveaux et al., 2008; Mukherjee et al., 2009; van der Graaff et al., 2009) showed that lycophytes have ancient and intermediate clades. Ferns, gymnosperms and angiosperms have all the three clades. Therefore, the intermediate clade might first originate in the common ancestor of lycophytes and euphyllophytes, suggesting that this clade evolved specifically in vascular plants. Conversely, there are no WUS-clade members in lycophytes, suggesting that stem cells in lycophytes are still at an early evolutionary stage.

In this study, we identified a lycophyte-specific clade in S. kraussiana; the evolutionary position of this clade is probably between the ancient and intermediate clades. This clade may have separated from the intermediate clade and further evolved in lycophytes. Studies on the functions of S. kraussiana WOX genes, together with studies on stem cell activities, organ formation, and regeneration in lycophytes using a molecular approach, may help us to understand the developmental mechanisms in the early evolution of vascular plants.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials, Culture Conditions, and Microscopy

Plants of S. kraussiana were grown at 26°C under a 16-h light (∼5000 Lux)/8-h dark photoperiod in a greenhouse or plant chamber. Microscopy analyses were performed using a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

We extracted genomic DNA from seedlings of S. kraussiana and then employed whole-genome shotgun strategy to decode the genome of S. kraussiana. DNA library construction and deep sequencing were performed by Genergy Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The average length of the inserted library was about 200 bp. The paired-end library was sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform following the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.). About 289 millions (289,347,796) of pair-ended reads were generated, which corresponded to 250× sequencing depth. The pair-ended reads were assembled with ABySS software v1.5.1 (Simpson et al., 2009), using the default parameters in ABySS assembler. A total of 49,647 contigs were larger than 500 bp and 8561 contigs were larger than N50 (3096 bp).

RNA-seq and Alignment

We extracted RNA samples from four different tissues of S. kraussiana: microphyll, shoot tip, rhizophore tip, and stem. The RNA extracts were used to construct RNA libraries and sequenced by Genergy Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The average length of inserted library was about 300 bp. The pair-ended libraries were sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 2000. A total of 936843033 (stem, 208693928; leaf, 240658608; rhizophore, 229142616; seeding, 258347936) pair-ended reads were obtained. The first ten base pairs were trimmed off the reads. The trimmed reads were aligned against the assembled genome sequence using TopHat V2.0 and then analyzed by CuffLinks V2.1 (Trapnell et al., 2010).

Genome Annotation by MAKER

To identify SkWOX genes, we used MAKER annotation pipeline (v 2.31) to annotate the assembled genome of S. kraussiana. The aligned RNA-seq dataset were used as EST evidences. The protein sequences of related S. moellendorffii species were used as protein evidences. We trained SNAP predictor with the protein sequences of S. moellendorffii. The repeat sequences dataset from S. moellendorffii were used as the input of RepeatMasker (v 4.0.5). After annotated by MAKER, those genes which were not supported by evidence or did not have a PFAM domain were filtered out. The genes were annotated by InterProScan (version: 5.15-54.0) (Jones et al., 2014).

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry analyses to determine the nuclear DNA contents of S. kraussiana and A. thaliana were performed according to the method described previously (Galbraith et al., 1983; Dolezel et al., 2007; Little et al., 2007). Approximately 150-mg rosette leaves of 3-week-old A. thaliana (Col-0) plants and 60-mg young branchlets of S. kraussiana were homogenized on ice in 1-ml ice-cold modified Galbraith’s buffer (45-mM MgCl2, 30-mM sodium citrate, 20-mM MOPS, 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, pH7.0, 5-mM sodium metabi-sulfite and 5-μl β-mercaptoethanol) complemented with 50-μg/ml PI and 100-μg/ml RNase. The homogenate was filtered through a 40-μm nylon cell strainer (Falcon, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), then the filtrate with an additional 50-μg RNase was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were kept on ice in the dark until analysis. Approximately 5000 particles were measured at a low sample flow rate using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (585/42 BP channel, 488-nm laser, Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed with FlowJo_V10 software.

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from seedlings or rhizophores of S. kraussiana using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and used as the template for reverse transcription as previously described (Xu et al., 2003; He et al., 2012). The RT-PCR analyses were performed using the following gene-specific primers:

5′-GTAAGTAAGCTTTTCAGATG-3′ and 5′-GTATGTGATCTATAAGCTTG-3′ for SkWOX13A; 5′-CACATGCACCTTATATTCCTCC-3′ and 5′-CGTACATACCATTGCATGAG-3′ for SkWOX13B; 5′-GCAGAACGAGGAGATTAGCG-3′ and 5′-GTCGTGTTAGCTCTAGTATAG-3′ for SkWOX13C; 5′-CAATCGCAACGTACGTTACAG-3′ and 5′-GTACTTTGTCGAGAAGGACAC-3′ for SkWOX13D; 5′-TAGGATCAAGTGACCACCTG-3′ and 5′-CAACTCAGAAGTCTGATGATC-3′ for SkWOX13E; 5′-CGAGTCTCTCACACTCAGAC-3′ and 5′-GAGCCTGAACCTGAACACAG-3′ for SkWOX11A; 5′-GTCTCCGTGAAGAAGCCCAAAG-3′ and 5′-GCGCACACAGCGGTGCACTG-3′ for SkWOX11B; and 5′-GGTTCGTGAGTCATTTGTGA-3′ and 5′-GTCGCCAGACTTACGAATTC-3′ for SkWOX11C.

Accession Numbers

The Whole Genome Shotgun project (DNA-seq data) has been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank. RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO. The sequences of WOX genes have been deposited in GenBank. Accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

Author Contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2014CB943500/2012CB910503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91419302/31422005) and Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS.

References

- Aichinger E., Kornet N., Friedrich T., Laux T. (2012). Plant Stem Cell Niches. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 615–636. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks J. A. (2009). Selaginella and 400 million years of separation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60 223–238. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks J. A., Nishiyama T., Hasebe M., Bowman J. L., Gribskov M., Depamphilis C., et al. (2011). The Selaginella genome identifies genetic changes associated with the evolution of vascular plants. Science 332 960–963. 10.1126/science.1203810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennici A. (2007). Unresolved problems on the origin and early evolution of land plants. Riv. Biol. 100 55–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennici A. (2008). Origin and early evolution of land plants: problems and considerations. Commun. Integr. Biol. 1 212–218. 10.4161/cib.1.2.6987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveaux Y., Toffano-Nioche C., Claisse G., Thareau V., Morin H., Laufs P., et al. (2008). Genes of the most conserved WOX clade in plants affect root and flower development in Arabidopsis. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:291 10.1186/1471-2148-8-291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezel J., Greilhuber J., Suda J. (2007). Estimation of nuclear DNA content in plants using flow cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2 2233–2244. 10.1038/nprot.2007.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff R. J., Nickrent D. L. (1999). Phylogenetic relationships of land plants using mitochondrial small-subunit rDNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 86 372–386. 10.2307/2656759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd S. K., Bowman J. L. (2006). Distinct developmental mechanisms reflect the independent origins of leaves in vascular plants. Curr. Biol. 16 1911–1917. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith D. W., Harkins K. R., Maddox J. M., Ayres N. M., Sharma D. P., Firoozabady E. (1983). Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science 220 1049–1051. 10.1126/science.220.4601.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haecker A., Gross-Hardt R., Geiges B., Sarkar A., Breuninger H., Herrmann M., et al. (2004). Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131 657–668. 10.1242/dev.00963dev.00963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C. J., Corley S. B., Moylan E. C., Alexander D. L., Scotland R. W., Langdale J. A. (2005). Independent recruitment of a conserved developmental mechanism during leaf evolution. Nature 434 509–514. 10.1038/nature03410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C. J., Rezvani M., Langdale J. A. (2007). Growth from two transient apical initials in the meristem of Selaginella kraussiana. Development 134 881–889. 10.1242/dev.001008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C., Chen X., Huang H., Xu L. (2012). Reprogramming of H3K27me3 is critical for acquisition of pluripotency from cultured Arabidopsis tissues. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002911 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002911PGENETICS-D-12-00157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch R., Young R. (2008). Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell 132 567–582. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P., Binns D., Chang H. Y., Fraser M., Li W., Mcanulla C., et al. (2014). InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30 1236–1240. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick P., Crane P. R. (1997). The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature 389 33–39. 10.1038/37918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenrick P., Strullu-Derrien C. (2014). The origin and early evolution of roots. Plant Physiol. 166 570–580. 10.1104/pp.114.244517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Tamura K., Nei M. (2004). MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5 150–163. 10.1093/bib/5.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander A. D. (2009). The ‘stem cell’ concept: is it holding us back? J. Biol. 8:70 10.1186/jbiol177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian G., Ding Z., Wang Q., Zhang D., Xu J. (2014). Origins and evolution of WUSCHEL-related homeobox protein family in plant kingdom. Sci. World J. 2014:534140 10.1155/2014/534140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little D. P., Moran R. C., Brenner E. D., Stevenson D. W. (2007). Nuclear genome size in Selaginella. Genome 50 351–356. 10.1139/g06-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee K., Brocchieri L., Burglin T. R. (2009). A comprehensive classification and evolutionary analysis of plant homeobox genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 2775–2794. 10.1093/molbev/msp201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardmann J., Reisewitz P., Werr W. (2009). Discrete shoot and root stem cell-promoting WUS/WOX5 functions are an evolutionary innovation of angiosperms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 1745–1755. 10.1093/molbev/msp084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardmann J., Werr W. (2012). The invention of WUS-like stem cell-promoting functions in plants predates leptosporangiate ferns. Plant Mol. Biol. 78 123–134. 10.1007/s11103-011-9851-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardmann J., Werr W. (2013). Symplesiomorphies in the WUSCHEL clade suggest that the last common ancestor of seed plants contained at least four independent stem cell niches. New Phytol. 199 1081–1092. 10.1111/nph.12343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otreba P., Gola E. M. (2011). Specific intercalary growth of rhizophores and roots in Selaginella kraussiana (Selaginellaceae) is related to unique dichotomous branching. Flora 206 227–232. 10.1016/j.flora.2010.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge M. J., Clark S. E. (2006). Evolution of the class III HD-Zip gene family in land plants. Evol. Dev. 8 350–361. 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer K. M., Schneider H., Smith A. R., Cranfill R., Wolf P. G., Hunt J. S., et al. (2001). Horsetails and ferns are a monophyletic group and the closest living relatives to seed plants. Nature 409 618–622. 10.1038/35054555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y., Li L., Wang B., Chen Z., Dombrovska O., Lee J., et al. (2007). A nonflowering land plant phylogeny inferred from nucleotide sequences of seven chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear genes. Int. J. Plant Sci. 168 691–708. 10.1086/513474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y. L., Palmer J. D. (1999). Phylogeny of early land plants: insights from genes and genomes. Trends Plant Sci. 4 26–30. 10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01361-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raubeson L. A., Jansen R. K. (1992). Chloroplast DNA evidence on the ancient evolutionary split in vascular land plants. Science 255 1697–1699. 10.1126/science.255.5052.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost T. L., Barbour M. G., Stocking C. R., Murphy T. M. (1997). Plant Biology. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara K., Reisewitz P., Aoyama T., Friedrich T., Ando S., Sato Y., et al. (2014). WOX13-like genes are required for reprogramming of leaf and protoplast cells into stem cells in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Development 141 1660–1670. 10.1242/dev.097444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders H. L., Langdale J. A. (2013). Conserved transport mechanisms but distinct auxin responses govern shoot patterning in Selaginella kraussiana. New Phytol. 198 419–428. 10.1111/nph.12183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B. (2007). Stem-cell niches: nursery rhymes across kingdoms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 345–354. 10.1038/nrm2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. T., Wong K., Jackman S. D., Schein J. E., Jones S. J., Birol I. (2009). ABySS: a parallel assembler for short read sequence data. Genome Res. 19 1117–1123. 10.1101/gr.089532.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K., Gordon S. P., Meyerowitz E. M. (2011). Regeneration in plants and animals: dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation, or just differentiation? Trends Cell Biol. 21 212–218. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000). Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408 796–815. 10.1038/35048692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Williams B. A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., Van Baren M. J., et al. (2010). Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28 511–515. 10.1038/nbt.1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Graaff E., Laux T., Rensing S. A. (2009). The WUS homeobox-containing (WOX) protein family. Genome Biol. 10:248 10.1186/gb-2009-10-12-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster T. R. (1969). An investigation of angle-meristem development in excised stem segments of Selaginella martensii. Can. J. Bot. 47 717–722. 10.1139/b69-102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster T. R., Steeves T. A. (1964). Developmental morphology of the root of Selaginella kraussiana A. Br. and Selaginella wallacei Hieron. Can. J. Bot. 42 1665–1676. 10.1139/b64-165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. (1937). Correlation phenomena and hormones in Selaginella. Nature 139 996 10.1038/139966a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wochok Z. S., Sussex I. M. (1975). Morphogenesis in Selaginella III. Meristem determination and cell differentiation. Dev. Biol. 47 376–383. 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90291-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Huang H. (2014). Genetic and epigenetic controls of plant regeneration. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 108 1–33. 10.1016/B978-0-12-391498-9.00009-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Xu Y., Dong A., Sun Y., Pi L., Xu Y., et al. (2003). Novel as1 and as2 defects in leaf adaxial-abaxial polarity reveal the requirement for ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and 2 and ERECTA functions in specifying leaf adaxial identity. Development 130 4097–4107. 10.1242/dev.00622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng M., Hu B., Li J., Zhang G., Ruan Y., Huang H., et al. (2015). Stem cell lineage in body layer specialization and vascular patterning of rice root and leaf. Sci. Bull. 1–12. 10.1007/s11434-015-0849-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zong J., Liu J., Yin J., Zhang D. (2010). Genome-wide analysis of WOX gene family in rice, sorghum, maize. Arabidopsis and poplar. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52 1016–1026. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]