Dear Editor,

Intraocular lens (IOL) fracture is a relatively rare complication of cataract surgery during IOL implantation [1]. Foldable IOLs specifically are often fractured by either forceps or injector systems during IOL loading [2,3]. To improve the efficacy and safety of cataract surgery, many preloaded IOLs have been developed and are widely used. Here, we report the first optic fracture in a preloaded IOL during posterior chamber, hydrophobic, acrylic IOL insertion.

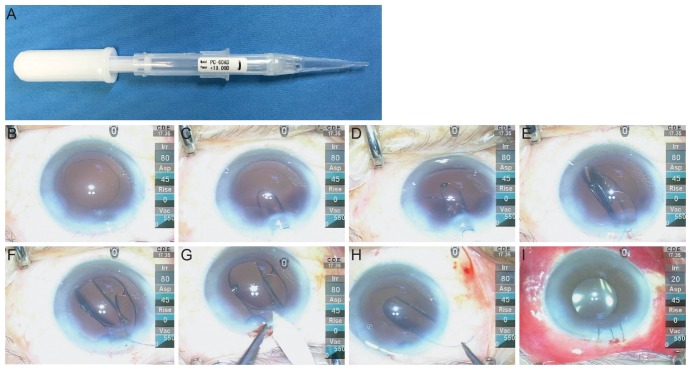

A 75-year-old male patient was admitted for left eye cataract surgery. He had no recent systemic disease and no history of ocular trauma. During surgery, the lens nucleus was successfully removed. For IOL insertion, we prepared a preloaded, three-piece IOL (Hoya iSert PS AF-1 [UV], PC-60AD; Hoya, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 1A) after removal of the remnants of both the epinucleus and cortex (Fig. 1B). We lubricated the iSert system inside (Hoya) case. We firmly grasped the body and slowly inserted the system in one continuous motion using the slider. We gently pushed the plunger forward and slowly rotated the iSert system clockwise in order to engage the threads and allow insertion of the IOL (Fig. 1C and 1D). However, during IOL insertion, we heard a cracking sound. Upon investigation, we found that the IOL optic had unfolded and broken into two pieces, with small posterior capsule rupture (Fig. 1E and 1F). We widened the corneal incision and withdrew the IOL from the chamber (Fig. 1G and 1H). After ensuring that there had been no loss of vitreous, a three-piece IOL was fixed inside the ciliary sulcus, and we successfully completed the cataract surgery (Fig. 1I). There were no further postoperative complications in the 3 months following surgery.

Fig. 1. The preloaded intraocular lens (Hoya iSert PS AF-1 [UV], PC-60AD; Hoya, Tokyo, Japan) and intraoperative clinical photographs. (A) The whole instrument. (B) Removal of the remnants of both the epinucleus and cortex. (C) Pushing the plunger forward. (D) Inserting the intraocular lens (IOL). (E) The unfolded IOL. (F) Optic fracture of the IOL. (G) Widening the corneal incision. (H) Withdrawing the IOL. (I) Fixation within the sulcus, and completion of the surgery.

Our case is unique due to optic fracture of the preloaded IOL during IOL insertion. The IOL was a three-piece lens with a 6.0-mm hydrophobic acrylic optic and polymethyl methacrylate chemically bonded haptics. The overall diameter was 12.5 mm. The IOL was preloaded into a unique system (iSert system) that reduces the time-consuming aspect of inserter preparation, cleaning, and sterilization. Moreover, using the iSert system, the IOL remains untouched throughout surgery, as it is contained within a disposable, closed, preloaded system. For this reason, one would expect fewer cases of lens damage.

Although the majority of IOL fractures are the result of mechanical causes [1,2,3,4,5] and the possibility of mechanical causes due to surgeon- or manufacturer-related factors cannot be excluded, the authors have suggested other possible mechanisms.

The IOL optic material has a glass transition temperature (Tg), the temperature above which an IOL becomes flexible and below which it remains rigid, of 11℃ [4]. As a result of this Tg, single and multi-piece hydrophobic IOLs can be folded and inserted through very small incisions, while still resisting damage at body temperature [5].

However, there are also a few disadvantages of this temperature. It is difficult to insert the IOL into the capsular bag using an injector system because of the rigid nature of the IOL at temperatures less than Tg. Eom et al. [4] have suggested that warmed ophthalmic viscoelastic devices (OVD) reduce the rigidity of the IOL, leading to decreased unfolding time. The same mechanism may have been important in our own case. Despite our operation room being maintained at 18℃ to 20℃, the OVD was stored in the refrigerator at 2℃ to 5℃. In addition, although we could not determine the exact mechanism of the IOL fracture in this patient, we suspect that the IOL may have been more rigid than desirable due to its storage at a temperature lower than its Tg. Deformation by pressure inside the preloaded injector may therefore have caused optic fracture of the IOL during insertion.

In conclusion, optic fracture of a preloaded, hydrophobic, acrylic IOL can occur during insertion. The present fracture may have been caused by increased rigidity or by mechanical factors. It might have been related to the Tg, suggesting that warming an OVD may help with reducing IOL rigidity.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Schmidbauer JM, Peng Q, Apple DJ, et al. Rates and causes of intraoperative removal of foldable and rigid intraocular lenses: clinicopathological analysis of 100 cases. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khokhar S, Sinha A, Saxena R. Intraoperative fracture of AMO Tecnis (silicone) foldable intraocular lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:1069–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasubramanya R, Rani A, Dada T. Forceps-induced cracking of a single-piece acrylic foldable intraocular lens. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2003;34:306–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eom Y, Lee JS, Rhim JW, et al. A simple method to shorten the unfolding time of prehydrated hydrophobic intraocular lens. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tetz M, Jorgensen MR. New hydrophobic IOL materials and understanding the science of glistenings. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40:969–981. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.978476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]