Dear Editor,

Bietti crystalline retinal dystrophy (BCD) is an autosomal recessive retinal dystrophy first described in 1937. It is characterized by numerous yellow-white crystals on the retina, associated with retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) atrophy and choroidal sclerosis [1]. Crystals and complex lipid inclusions are found in choroidal fibroblasts, cornea, conjunctiva, and circulating lymphocytes, implying that this condition results from a systemic abnormality. Although many cases with the CYP4V2 gene mutation have been reported worldwide, the first report of BCD in a Korean patient with a CYP4V2 gene mutation was recently published [2].

Herein, we present a Korean case of BCD confirmed to have a CYP4V2 gene mutation, review the previously reported BCD cases and their causative mutations, and present the key structural features of BCD with a novel hypothesis and the genetic disparity between Asians and non-Asians.

A 45-year-old man was referred to Seoul National University Bundang Hospital with impaired vision in both eyes. He had monocular diplopia, nyctalopia, and photopsia, persisting for the previous 2 months. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Blood analysis and tests for autoantibodies revealed no abnormalities.

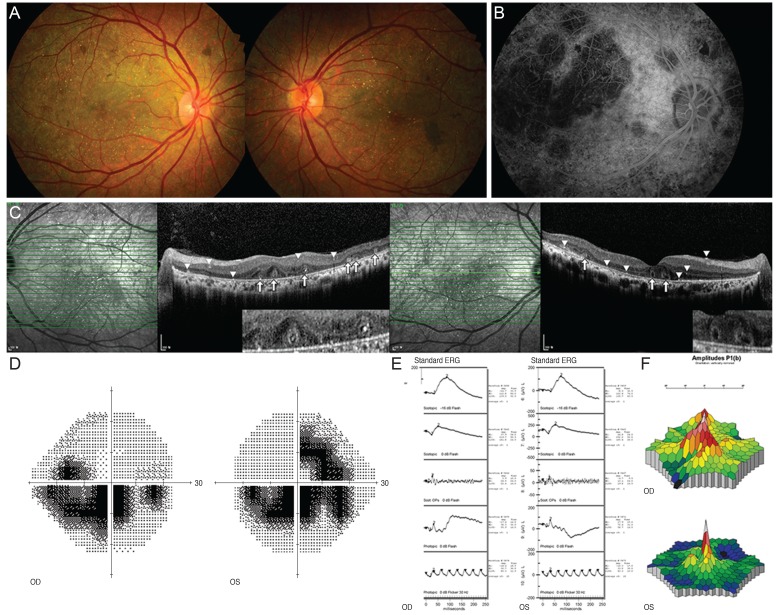

At the initial examination, his uncorrected visual acuities were 12 / 20 in the right eye and 14 / 20 in the left eye, with refractive errors of -2.625 Dsph in the right eye and -2.250 Dsph in the left eye. Slit lamp examination revealed a few crystal deposits in the cornea. Fundoscopic examination showed numerous yellowish-white crystals over the whole retina. RPE degeneration was observed with choroidal atrophy, which was more severe in the posterior pole than in the peripheral area (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Fundus photographs of both eyes (A) of our 45-year-old male patient with confirmed Bietti crystalline retinal dystrophy. Numerous retinal crystals are observed throughout the posterior pole and in the mid-periphery. Retinal pigment epithelium degeneration and choroidal atrophy are also found. A fundus fluorescence angiography image of the retinal arterial phase in the right eye (B) showing well-defined choriocapillaris filling defects, pigment epithelial window defects, and punctate blocked fluorescence. Optical coherence tomograph showing intraretinal and intrachoroidal crystalline deposits (arrowheads) with outer retinal rosette (arrows) (C). Grayscale image from Humphrey visual field test showing a central scotoma (D). Standard electroretinogram (ERG) showing slightly reduced amplitudes (E). Multifocal ERG showing reduced amplitude in the central macular area (F). OD = right eye; OS = left eye.

Fundus fluorescein angiography showed a well-demarcated window defect due to RPE degeneration and choroidal atrophy and punctate fluorescein blockage caused by RPE hypertrophy (Fig. 1B). Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) showed generalized photoreceptor layer disruption and multiple small hyper-reflective crystals in the retina, RPE-choriocapillary complex, and choroidal layers (Fig. 1C). Multiple circular structures with a hyper-reflective core were also observed. A standard 24-2 static visual field test (Humphrey Field Analyzer; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) showed central scotoma (Fig. 1D). A standard electroretinogram showed slightly reduced amplitudes, while multifocal electroretinogram revealed a loss of peak response in the fovea (Fig. 1E and 1F). The patient was diagnosed with BCD based on these characteristic features. Genetic analysis of the CYP4V2 gene revealed a c.802-8_810delinsGC homozygote mutation. After 6 months, his visual acuity and the ophthalmologic findings remained unchanged.

Although BCD cases have been reported worldwide, this condition is more common in East Asia. In most of the studies on BCD, Exon 7-related mutations including the c.802-8_810delinsGC mutation account for at least 83.2% of the cases in Chinese and Japanese populations but for 30.0% in 20 non-Asian families presented to date [3]. In Korea, Chung et al. [2] also identified the same mutation in one Korean BCD patient. Identification of the same c.802-8_810delinsGC mutation in our patient suggests that this is a predominant BCD mutation in Koreans as in other Asians.

In addition to the typical hyper-reflective dots in the retina, an interesting feature on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography was the outer-retinal circular structures. Some researchers have proposed these structures to be an outer-retinal rosette formation such as an outer retinal tubulation, infrequently found in chronic photoreceptor degeneration such as age-related macular degeneration [4]. However, no definite mechanism has been proposed for the outer rosette formation in BCD [5]. From an in-depth analysis of the circular structure, we suggest that the photoreceptors surrounding the crystal nidus cause the rosette formation. The solitary crystals in BCD make the structure circular, while the linear RPE debris in age-related macular degeneration makes it tubular (outer retinal tabulation). We speculate that the surface of the crystal in BCD has an affinity for photoreceptor outer segments such as RPE clumps, which enables rosette formation. However, this hypothesis remains to be further elucidated using methods including electron microscopy.

In summary, we report a Korean case of BCD confirmed by genetic identification of the known CYP4V2 mutation. A literature review suggested that Asians and other ethnicities have differing genetic predisposition to this mutation. We also propose a new hypothesis for the cause of outer-retinal rosette formation in BCD and other retinal degenerative diseases such as age-related macular degeneration.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Li A, Jiao X, Munier FL, et al. Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy is caused by mutations in the novel gene CYP4V2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:817–826. doi: 10.1086/383228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung JK, Shin JH, Jeon BR, et al. Optical coherence tomographic findings of crystal deposits in the lens and cornea in Bietti crystalline corneoretinopathy associated with mutation in the CYP4V2 gene. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2013;57:447–450. doi: 10.1007/s10384-013-0256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao X, Mai G, Li S, et al. Identification of CYP4V2 mutation in 21 families and overview of mutation spectrum in Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojima H, Otani A, Ogino K, et al. Outer retinal circular structures in patients with Bietti crystalline retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:390–393. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.199356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iriyama A, Aihara Y, Yanagi Y. Outer retinal tubulation in inherited retinal degenerative disease. Retina. 2013;33:1462–1465. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31828221ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]