Abstract

Mambalgins are peptides isolated from mamba venom that specifically inhibit a set of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) to relieve pain. We show here the first full stepwise solid phase peptide synthesis of mambalgin-1 and confirm the biological activity of the synthetic toxin both in vitro and in vivo. We also report the determination of its three-dimensional crystal structure showing differences with previously described NMR structures. Finally, the functional domain by which the toxin inhibits ASIC1a channels was identified in its loop II and more precisely in the face containing Phe-27, Leu-32, and Leu-34 residues. Moreover, proximity between Leu-32 in mambalgin-1 and Phe-350 in rASIC1a was proposed from double mutant cycle analysis. These data provide information on the structure and on the pharmacophore for ASIC channel inhibition by mambalgins that could have therapeutic value against pain and probably other neurological disorders.

Keywords: acid sensing ion channel (ASIC), pain, peptide chemical synthesis, peptide interaction, sodium channel, structural model, toxin, X-ray crystallography, mambalgin

Introduction

Mambalgins are pain-relieving peptides that have been recently isolated from black and green mamba venoms (1) and characterized for their capacity to specifically inhibit a set of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs).4 ASICs are voltage-independent cation channels activated by extracellular acidification (2). They are widely expressed throughout the pain pathway and more generally in the nervous system (3). The involvement of ASICs has been recognized in an increasing number of physiological and pathophysiological processes ranging from synaptic plasticity and neuronal injury to nociception and mechanoperception (4, 5). ASICs therefore emerge as unique pharmacological targets with potential clinical applications in the management of pain, psychiatric disorders, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases (5).

Mambalgin-1–3 are 57-amino acid peptides that only differ by one or two residues and display the same pharmacological profile (1, 6). These three-finger fold toxins block all the ASIC channel combinations expressed in central neurons and some expressed in nociceptors. More specifically, inhibition of ASIC1a- and ASIC1b-containing channels (with IC50 ranging from 11 to 252 nm) produces potent analgesic effects in vivo in mice that can be as strong as morphine but are resistant to naloxone and do not involve opioid receptors (1). Mambalgins have no apparent toxicity and seem to produce fewer unwanted side effects than morphine, illustrating the potential therapeutic value of these ASIC-inhibitory peptides (7–9). Mambalgins act as gating modifiers that bind to the closed state of the channel and induce a strong shift of the pH-dependent activation of ASIC1a channel toward more acidic pH, decreasing its apparent affinity for protons (1). The binding site on ASIC channels and the inhibitory mechanism of these peptides have been recently identified (10). Mambalgins bind into the acidic pocket of the extracellular domain of ASIC1a and have been proposed to block the channel by a pH sensor-trapping mechanism. Chemical synthesis of mambalgin-1 and -2 has been done recently using the chemical ligation approach (11, 12), and their structures have been determined using NMR. However, stepwise synthesis of the entire 57-residue toxin failed, even with optimized protocols (11, 12), and the crystal structure of the peptide was not solved. In addition, residues of mambalgins involved in the inhibition of ASIC channels remain to be determined.

In this work, we report the stepwise solid phase synthesis of mambalgin-1, the x-ray crystal structure of wild-type mambalgin-1, and those of various variants, and we propose a crucial role for its central loop in the interaction with ASIC1a. Furthermore, using a double mutant cycle approach, proximity between Leu-32 in mambalgin-1 and Phe-350 in rat ASIC1a is proposed and used to build a binding model of the toxin-channel complex.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

Fmoc-amino acids, Fmoc-pseudoproline dipeptides, and 2-(6-chloro-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3,-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HCTU) were obtained from Activotec (Cambridge, UK). The resin and all the peptide synthesis grade reagents (N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP), N-methylmorpholine (NMM), dichloromethane, piperidine, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), anisole, thioanisole, and triisopropylsilane) were purchased from Sigma (Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France).

Synthesis of sMamb-1 and Alanine Variants

Peptide synthesis of mambalgin-1 and 11 alanine variants was performed on a Protein Technologies, Inc., prelude synthesizer at a 12.5-μmol scale using a 10-fold excess of Fmoc-amino acid relative to the preloaded Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-wang-LLresin (0.33 mmol/g). Fmoc-protected amino acids were used with the following side-chain protections: tert-butyl ester (Glu and Asp), tert-butyl ether (Ser, Thr, and Tyr), trityl (Cys, His, Asn, and Gln), tert-butoxycarbonyl (Lys), and 2,2,5,7,8-pentamethyl-chromane-6-sulfonyl (Arg). Amino acids were coupled twice for 5 min using 1:1:2 amino acid/HCTU/NMM in NMP. Pseudoproline dipeptides were coupled twice for 10 min. Amino acids in the sequence fragments 1–5 (LKCYQ) and 30–34 (LKLIL) were coupled four times for 5 min. After incorporation of each residue, the resin was acetylated for 5 min using a 50-fold excess of a mixture of acetic anhydride and NMM in NMP. Fmoc deprotection was performed twice for 2 min using 20% piperidine in NMP, and 30-s NMP top washes were performed between deprotection and coupling steps. Following chain assembly, the peptidyl-resin was treated with a mixture of TFA/thioanisole/anisole/thioanisole and triisopropylsilane/water (82:5:5:2.5:5) for 2 h. The crude peptide was obtained after precipitation and washes in cold ethyl ether followed by dissolution in 10% acetic acid and lyophilization. The different peptides were purified by reverse phase HPLC using an X-Bridge BHE C18-300-5 semi-preparative column (Waters) (250 × 10 mm; 4 ml·min−1; solvent A, H2O/TFA 0.1%; solvent B, acetonitrile/TFA 0.1%; gradient, 20–40% solvent B in 40 min), and checked by mass spectrometry using ESI-MS (Bruker, Germany).

Disulfide Bond Formation and Characterization

The purified peptides were dissolved in 6 m guanidine HCl in 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 8, and diluted (1:100) in degassed 0.1 m Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8, buffer in the presence of reduced (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (molar ratio of 1:10:100 peptide/oxidized glutathione/GSH at a peptide concentration of 0.05 mg/ml) and then incubated at 4 °C for 24–36 h. After acidification, purification of the refolded toxins was performed on an X-Bridge BHE C18-300-5 semi-preparative column (Waters) (250 × 10 mm; 4 ml·min−1; solvent A, H2O/TFA 0.1%; solvent B, acetonitrile/TFA 0.1%; gradient, 20–40% solvent B in 40 min). Each toxin was checked by mass spectrometry using ESI-MS (Bruker, Germany) (Table 1) after analytical reverse phase HPLC on a X-Bridge BHE C18-300-5 analytical colum (Waters) (250 × 4.5 mm; 1 ml·min−1; solvent A, H2O/TFA 0.1%; solvent B, acetonitrile/TFA 0.1%; gradient, 20–40% solvent B in 40 min).

TABLE 1.

Mass determination of wild-type and sMamb-1 variants

| sMamb-1 variant | Theoretical mean Mr | Observed mean Mr |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced wild type | 6562.5 | 6562.3 ± 0.2 |

| Oxidized wild type | 6554.6 | 6554.4 ± 0.3 |

| H21A | 6488.5 | 6488.2 ± 0.2 |

| T23A | 6524.5 | 6524.2 ± 0.2 |

| F27A | 6478.4 | 6478.2 ± 0.1 |

| R28A | 6469.4 | 6469.4 ± 0.3 |

| N29A | 6511.5 | 6511.4 ± 0.2 |

| L30A | 6512.5 | 6512.0 ± 0.1 |

| K31A | 6497.4 | 6497.4 ± 0.4 |

| L32A | 6512.5 | 6512.4 ± 0.1 |

| I33A | 6512.5 | 6512.4 ± 0.2 |

| L34A | 6512.5 | 6512.4 ± 0.1 |

| K57A | 6497.4 | 6497.2 ± 0.1 |

Xenopus Oocyte Preparation, DNA Injection, and Electrophysiological Measurements

Animal handling and experiments fully conformed to French regulations and were approved by local governmental veterinary services (authorization number B 061525 delivered by the Ministère de l'Agriculture, Direction des Services Vétérinaires). Briefly, animals were anesthetized by exposure for 20 min to a 0.2% solution of 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (MS-222). Oocytes were surgically removed, dissociated with collagenase type IA (Sigma), and then injected into the nucleus with 20 nl of pCI-rat ASIC1a (3–5 ng/μl) or pCI rat ASIC1b (100 ng/μl) plasmids, or a mixture of pCI-rat ASIC1a (10 ng/μl) + pCI-rat ASIC2a (5 ng/μl). Oocytes were kept at 19 °C in ND96 solution containing 96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH) with penicillin (6 μg/ml) and streptomycin (5 μg/ml). ASIC currents were recorded using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique using two standard glass microelectrodes (0.5–2.5 megaohms) filled with a 3 mm KCl (manual setup) or with a mixture (50:50) of 1 m KCl and 1.5 m potassium acetate (Roboocyte2), 1–2 days after injection using either a Roboocyte2 automated work station (MultiChannelSystems MCS, Reutlingen, Germany) or a manual setup (Dagan TEV 200 amplifier, Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN). Oocytes were clamped at −60 mV (Roboocyte2 recordings) or −50 mV (manual recordings), and ASIC currents were activated by rapid changes in extracellular pH induced by microperfusion systems. HEPES was replaced by MES (5 mm) for buffer solutions at pH 5.0. Stimulation, data acquisition, and analysis for manual recordings were performed using pCLAMP 9.2 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) or Roboocyte2+ software. All experiments were performed at 19–21 °C in ND96 solution supplemented with 0.05% fatty acid- and globulin-free bovine serum albumin (Sigma) to prevent nonspecific adsorption of the toxins to tubing and containers. Mambalgins were applied 30 s before the acid stimulation. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4.03 software. Data are represented as means ± S.E., and the statistical significance of differences between sets of data were estimated using the Kruskal-Wallis statistical multiple comparison followed by Dunn's post test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001).

Double Mutant Cycle Analysis

The difference in binding energy caused by a punctual modification is calculated through ΔΔGWT>mut (ΔΔGWT > mut = ΔGmut − ΔGWT = RT ln(Kd(mut)/Kd(WT)), with R = 1.99 cal/mol/K and T = 293 K). When the ΔΔG associated with a couple of modifications (i.e. on the toxin and on the channel) was significantly different from the sum of the ΔΔG values associated with each single modification, the two modified residues were considered to be in proximity and possibly in interaction (13). The coupling energy (ΔΔGint), which reflects the interaction energy for the two modified residues, was calculated from ΔΔGint = RT ln(Ω), with Ω = K(WT1, WT2) × K(mut1, mut2)/K(WT1, mut2) × K(mut1, WT2), where K is Kd or Ki; WT1 is Phe-350; mut1 is F350L; WT2 is Phe-27 or Leu-32 or Leu-34; and mut2 is F27A, L32A, or L34A. According to the equation, Ki = (T)(I/Io)/(1 − (I/Io)) (13), where Io is the control current level, and I is the current in presence of toxin concentration [T], we can deduce that Ki = IC50 when [T] = IC50. Thus, we can deduce Ω = IC50(WT1, WT2) × IC50(mut1, mut2)/IC50,(WT1, mut2) × IC50, (mut1, WT2).

Pain Behavior Experiments

Experiments were performed on 7–13-week-old (20–25 g) male C57BL/6J mice (Charles River). Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Local Ethical Committee and the French “Ministère de la Recherche” according to the European Union Regulations (Agreements C061525, NCE/2011-06, and 01550.03).

Inflammation was evoked by intraplanar (i.pl.) injection in the left hind paw of 20 μl of 2% carrageenan (Sigma). After 2 h, the time course of paw-flick latency was measured before and after injection of sMamb-1 or vehicle. Heat pain was assessed measuring the hind paw withdrawal latency (seconds) from a 46 °C bath using the paw-flick test, with a cutoff time at 30 s. Synthetic mambalgin-1 was i.pl.-injected (0.34 nmol/mouse) in the left hind paw (vehicle, 0.9% NaCl + 0.05% BSA) on carrageenan-induced heat hyperalgesia, and the paw withdrawal latency was measured during 2 h after injection.

Data analysis and statistics were performed with Microcal Origin 6.0 and GraphPad Prism 4 software. After testing the normality of data distribution with Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Shapiro-Wilk, and D'Agostino-Pearson tests, the statistical difference between two different experimental groups was analyzed by unpaired Student's t test. For data within the same experimental group, a paired Student's t test was used.

Crystallization and Crystallographic Structure Determination

Crystallization experiments were carried out with lyophilized wild-type sMamb-1 and various modified toxins derived from alanine scanning, redissolved at 5 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5. The crystallization trials were carried out using Cryst ChemTM sitting drop vapor diffusion plates with 1-μl drops of protein and precipitant, stored in a constant temperature incubator at 20 °C using the Stura Screens (14) from Molecular Dimensions. Crystals of wild-type sMamb-1 for x-ray data collection were obtained from drops that were streak-seeded (15) using a reservoir solution consisting of 30% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 600, 200 mm imidazole malate, pH 7.0, in the tetragonal space group P41212 with cell parameters a = b = 46.9 Å, c = 80.6 Å. Screening for different polymorphs can be a useful strategy not only in drug design (16) but also to obtain heavy atom derivatives, a molecular replacement solution in difficult cases, and to ensure that structural variations are not the result of lattice interactions. With a reservoir consisting of 18% PEG 4000, 3% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, 3% 1,4-dioxane, 188 mm imidazole malate, pH 6.0, a different polymorph was obtained in the monoclinic space group P21 with cell parameters a = 40.2 Å, b = 50.6 Å, c = 46.9 Å, and β = 93.26 °. Unfortunately, all attempts to solve the structure using molecular replacement starting from the NMR mambalgin-1 (2MJY (12)) or mambalgin-2 (2MFA (11)) models with either of the two wild-type polymorphs were unsuccessful. Similarly, derivatization of the wild-type crystals did not give sufficiently high quality data to obtain a structure solution using SAD data, probably because of the low solvent content of the crystals. The structure was solved using iodine SAD data collected from another polymorph in the orthorhombic space group C2221 using crystals of the T23A variant with cell parameters a = 55.9 Å, b = 101.0 Å, and c = 53.5 Å, grown from 21.6% PEG 600, 3.6% PEG 20,000, 90 mm mixed l-malic acid, MES, Tris (MMT), pH 4.0, and 90 mm mixed sodium malonate, imidazole, boric acid (MIB), pH 10.0. Before data collection, the crystals were soaked in 6 μl of cryoprotectant solution consisting of 30% monomethyl PEG 550, 100 mm KI, 40% Cryomix9 (CryoProtX, from Molecular Dimensions) (16), 100 mm sodium acetate, pH 6.5, for 1 min. The data for the iodide derivative was collected at Soleil on the microfocus beamline Proxima 2A (17) and tuned to wavelength 0.9801 Å using the helican scan procedure to reduce radiation damage. All crystallographic data were integrated using XDS and scaled with XSCALE (18). The Phenix AutoSol Wizard (19) was used to determine the phases from the SAD data (20) and to fit automatically (21) the electron density map starting with the sequence and 1.7 Å resolution data. The anomalous data extends to 1.9 Å resolution with a merging R-factor of 15.7% at this resolution. About 80% of the two molecules in the asymmetric unit were correctly fitted by the automatic procedure, and the structure was then completed using COOT (22) and refined with both REFMAC (23) and phenix.refine (24). The sMamb-1 wild-type structures, with two and four molecules in the asymmetric unit, could be solved by molecular replacement using either MOLREP (25) or Phaser (20) starting either from the dimer present in the T23A mutant C2221 lattice or from a single molecule. The crystal structure for the variant R28A, with similar P41212 cell as the wild type, was determined as well as the more problematic structure of the F27A mutant in the rare P2 space group with 16 molecules in the asymmetric unit, twinning problems, diffracting to lower resolution.

Accession Codes

The crystal structure data for the sMamb-1 wild-type and variants have been deposited at Protein Data Bank with accession codes (T23A, 5DO6; wild type P21, 5DU1; and wild type P41212, 5DZ5).

Docking Studies

We used ZDOCK (server version 2.3.2f) to carry out the protein-protein docking simulations of rASIC1a to sMamb-1 crystal structures. ZDOCK performs rigid-body docking by exploring both the rotational and translational degrees of freedom of the protein structures. The homology model of the channel in the desensitized state at conditioning pH 7.0 was used. The toxin was represented by its four crystal structures of wild-type PDB 5DU1 chains A–D. ZDOCK was used with default settings along with the filtering option. To take into account the data from alanine scanning, complex solutions from the top 2000 ZDOCK predictions were filtered using the rASIC1a-Phe-350/sMamb-1-Leu-32 pairing residues and a 6-Å distance cutoff. Only two out of the four chains (PDB 5DU1 chain B and D) led to binding modes in agreement with experimental results.

Results

Synthesis and Refolding of Wild-type and Alanine Variants of Mambalgin-1

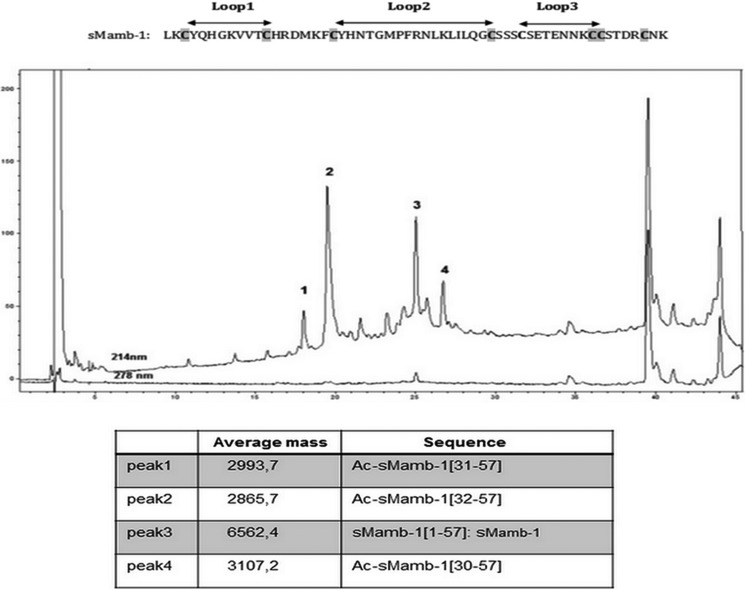

Despite a size accessible to standard Fmoc-based solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) (57 residues), this strategy was reported to fail in obtaining mambalgin-1 (Mamb-1) (11). As shown on the LC-MS profile (Fig. 1), we reached a similar conclusion by using a Fast Fmoc solid phase peptide strategy associated with a large excess of amino acids and using HCTU/NMM as coupling reagents. We confirmed massive chain terminations at positions 32, 31, and 30 and found only traces of fully synthesized mambalgin-1. To address this issue, we modified our strategy to adopt a full stepwise solid phase peptide synthesis of Mamb-1 by replacing Ser-40, Thr-23, and Thr-11 by pseudoproline residues and incorporating the commercial dimethyloxazolidine of the di-peptides Ser-Ser at position 39–40, Asn-Thr at position 22–23, and Val-Thr at position 10–11. These compounds, called pseudoprolines, disrupt peptide chain aggregation in the same manner as a proline residue does (26). At the end of the synthesis, regeneration of the serine or threonine from the oxazolidine occurs during the course of the normal TFA-mediated cleavage reaction. Synthesis was performed by Fast Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis using HCTU as coupling reagent and coupling times of 5 min. A longer coupling time (10 min) was used for the incorporation of the three pseudoproline dipeptides. Moreover, double coupling was repeated to incorporate residues in sequence fragments 1–5 (LKCYQ) and 30–34 (LKLIL). The synthesis was performed successfully on 0.1- and 0.01-mmol scales in 45 h. The full-length polypeptide was isolated readily after HPLC purification (Fig. 2A), and 8.5 mg of pure linear synthetic mambalgin-1 (sMamb-1) was obtained from a 0.01-mmol scale synthesis. The purity of the linear sMamb-1 was determined by RP-HPLC and ESI-MS (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

LC-ESI/MS of the crude mixture resulting from the synthesis of sMamb-1 in the absence of pseudoproline. Analysis was performed on an Agilent 1100 series (Santa Clara, CA) coupled on line to ion trap mass spectrometer Esquire equipped with an AP-ESI source (Bruker, Germany) LC separation Xbridge C18 BEH300, 3.5 μm (4.6 × 150 mm), gradient: 10–45% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA, 45 min, 1 ml·min−1. The sequence of sMamb-1 is shown at the top of the figure.

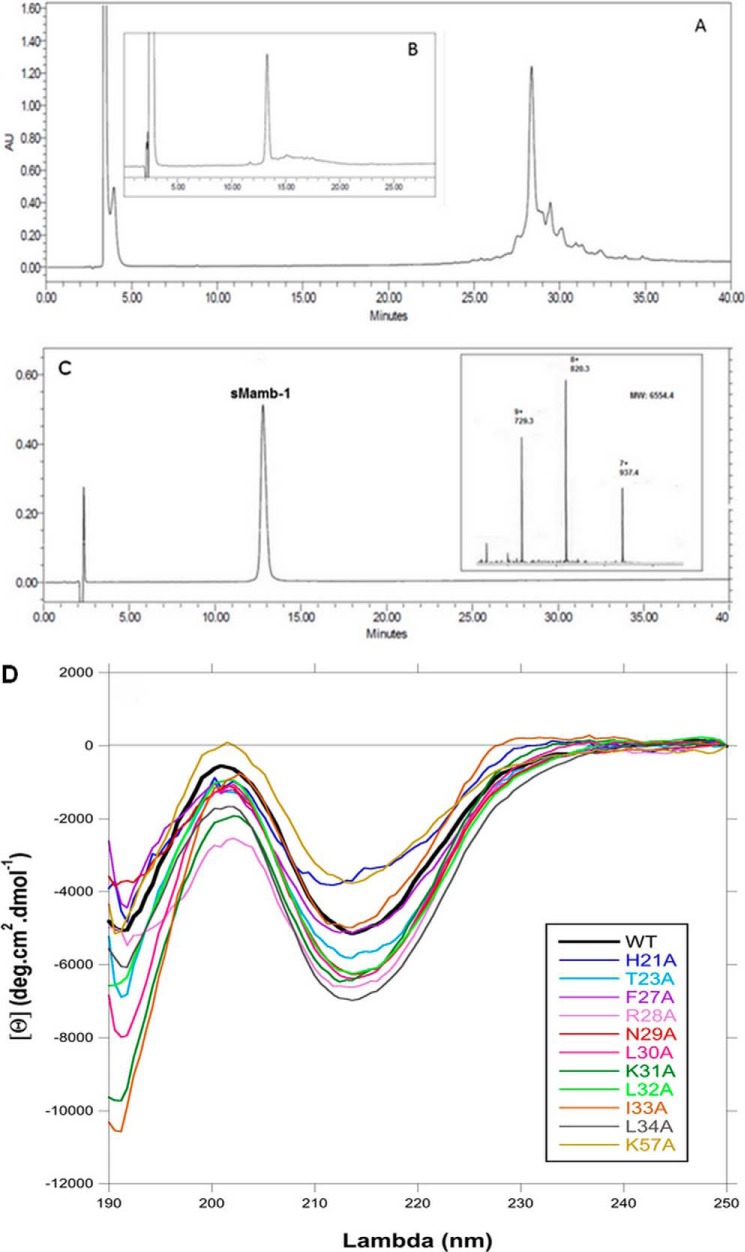

FIGURE 2.

RP-HPLCs of sMamb-1 synthesis and refolding and MS spectrum and circular dichroism analyses. A, crude mixture obtained after SPPS of sMamb-1, and the major peak at 28.5 min corresponds to mambalgin-1; B, crude mixture after 36 h of refolding; and C, chromatogram of the purified toxin. Separations were performed on a X-Bridge BHE C18-300-5 analytical column (Waters) (250 × 4.5 mm; 1 ml·min−1; solvent A, 0.1%H2O/TFA; solvent B, 0.1%acetonitrile/TFA; gradient, 20–40% solvent B in 40 min). Inset in C shows the ESI-MS spectrum of the individual peak. D, circular dichroism spectra of wild-type and alanine variants of sMamb-1 showing their three-finger fold signature characterized by a maxima and a minima at 202 and 213 nm, respectively.

Folding of sMamb-1 was achieved using the experimental conditions that were successfully applied to other members of the three-finger fold toxin family such as nicotinic and muscarinic toxins and are similar to those reported for mambalgin-1 and -2 (11, 12). As shown in Fig. 2B, sMamb-1 folds efficiently with 55% yield after 36 h, giving 4.6 mg of pure homogenous sMamb-1 after purification. The purity of sMamb-1 was determined by RP-HPLC and ESI-MS (Fig. 2C: observed mass, 6554.4 Da; calculated mass, 6554.6 Da, average isotope composition). Then, to perform an alanine-scanning study, 11 sMamb-1 alanine variants were obtained with a similar strategy. Mass analysis of all these variants was performed to confirm their purity and correct sequences (Table 1). Their CD spectra revealed a typical β-sheet signature with a minimum signal close to 213 nm, similar to that of sMamb-1, thus confirming a correct pairing of the four disulfide bridges (Fig. 2D).

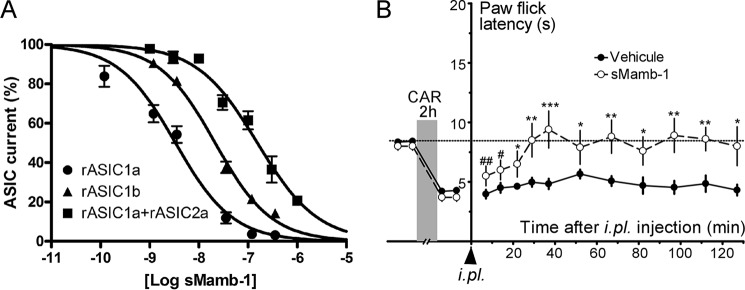

sMamb-1 Inhibits Recombinant ASIC Channels and Evokes Peripheral Analgesic Effects in Vivo

sMamb-1 inhibits efficiently homomeric rat ASIC1a, rat ASIC1b, and heteromeric rat ASIC1a + ASIC2a channels heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes (IC50 values are 3.4 ± 0.6, 22.2 ± 1.7, and 152 ± 21 nm, respectively) (Fig. 3A). These values compare well with those previously reported in the Xenopus oocyte expression system for native mambalgin-1 isolated from snake venom, i.e. 11, 44, and 252 nm (6). The slightly higher potency of sMamb-1 may reflect the higher purity of the synthetic peptide or the fact that different two-electrode voltage clamp setups have been used.

FIGURE 3.

In vitro and in vivo biological activity of sMamb-1. A, inhibition by sMamb-1 of recombinant ASIC channels. Inhibitory sMamb-1 dose-response curves (% of control current) for homomeric rat ASIC1a, homomeric rat ASIC1b, and heteromeric rat ASIC1a + ASIC2a channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Curves were fitted according to the sigmoidal dose-response equation: Y = current %/(1 + 10)[caret]((logIC50 − X)·nH)), where nH is the Hill slope number, and IC50 is the concentration that inhibits 50% of the control current. IC50 values are 3.4 ± 0.6 (nH = −0.75), 22.2 ± 1.7 (nH = −0.9), and 152 ± 21 nm (nH = −1) for rASIC1a, rASIC1b, and rASIC1a + rASIC2a currents, respectively (n = 3–5). B, intraplantar injection of sMamb-1 reverses thermal inflammatory hyperalgesia. Effect of i.pl. injection of sMamb-1 (0.34 nmol/mouse) in the left hind paw (vehicle, saline + 0.05% BSA) on carrageenan-induced heat hyperalgesia (carrageenan 2%, 2 h) determined using the paw immersion test (46 °C). Mean ± S.E., n = 10–20. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.005 compared with vehicle (unpaired t test); #, p < 0.05 and ##, p < 0.001 compared with control value before carrageenan injection (paired t test). CAR, carrageenan.

Local intraplantar injection of sMamb-1 in mice reversed heat inflammatory hyperalgesia, although injection of vehicle did not, similarly to what we previously described with native mambalgin-1 purified from Dendroaspis polylepis venom (Fig. 3B) (1). The paw-flick latency increased from 3.7 ± 0.3 to 9.4 ± 1.5 s (n = 10), a value not significantly different from the control latency value before carrageenan injection (8.0 ± 0.3 s). The anti-hyperalgesic effect reached its maximum within 30 min and lasted for the 2 h of the experiment.

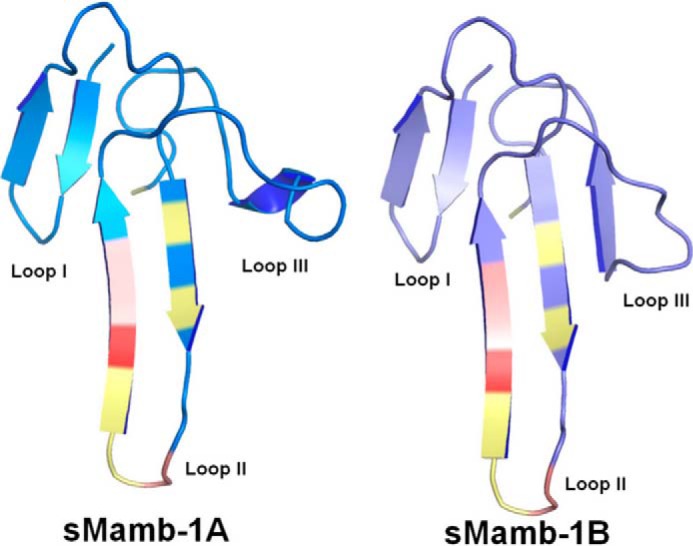

Crystallographic Structure Determination of sMamb-1 and Alanine Variants

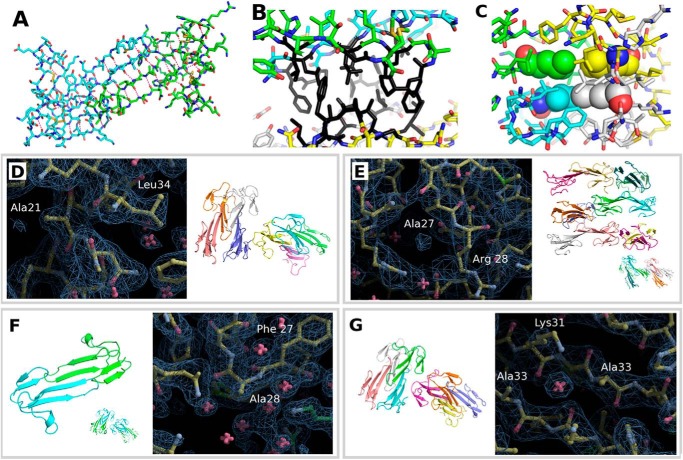

Wild-type sMamb-1 and several alanine variants were crystallized in various crystal forms (Tables 2 and 3). The preferred crystal form depends strongly on the protein sequence, but most modified toxins respond positively to streak seeding (15) with the tetragonal crystal form. Even if the crystal seeds deposited along the streak fail to grow, crystals of a different polymorph nucleate along the line to yield crystals suitable for x-ray data collection. The resolution to which the crystals diffract ranges from 2.9 to 1.5 Å. The crystal structures of two wild-type sMamb-1 polymorphs and five alanine variants have been determined (Table 3). Among the variants, the T23A crystal form with a higher solvent content was instrumental in obtaining a solution for the x-ray structures. No molecular replacement solution could be obtained using neither the NMR models nor using truncated crystal structures from three-finger fold toxins. The crystal structure of the T23A variant in C2221 was solved by short-soak iodide SAD phasing permitting the solution of all the other structures by molecular replacement (PDB_id = 5DO6). The asymmetric unit of the C2221 polymorph contains a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The same dimer is the sole constituent of the asymmetric unit of the tetragonal P41212 polymorph of wild-type sMamb-1 (PDB_id = 5DZ5), although the asymmetric unit of the second wild-type polymorph in space group P21 is composed of two such dimers (PDB_id = 5DU1). The wild-type crystal data can be exploited to 1.75 and 1.8 Å (27), respectively, with good refinement statistics (Table 2). The precise fold adopted by the T32A variant and the wild-type toxin in either of the two polymorphs is also found in all alanine scan variant structures, with conformational variations being limited to finger III as exemplified in Fig. 4. This fold conforms to that of the other three-finger family with a long extended finger II and a short finger III. Finger I leaves residues 29–35 of finger II exposed. In all the crystal polymorphs analyzed so far, this stretch mediates dimer formation through a long β-zipper interaction. The dimer assembles to form a tetramer through interactions that shield Pro-26 and Phe-27 from solvent (Fig. 5, A and B). The tetramer generated through the interaction of several hydrophobic residues centered on Leu-32 can be found in several polymorphs when symmetry mates are taken into account (Fig. 5C). The dimer and tetramer interactions may be important to confer good water solubility to the polypeptide when concentrated in vitro. In a dilute solution and in vivo, the monomer is likely to prevail. Although the overall structure resembles that of the three-finger fold toxins, the short 57-residue sequence confers sMamb-1, a unique character in its second loop. Indeed, the short fingers I and III flanking finger II allow it to form a long anti-parallel double-stranded β-sheet that protrudes to a large extent into the solvent. Although finger I maintains the classical short fold, the third finger shows unprecedented flexibility. Portions of this finger (residues 47–50) can form a short β-strand to extend the β-sheet through main-chain hydrogen bonding interactions with residues 17–21 or switch to form a short single turn α-helix (Fig. 4). This conformational duality is the likely cause for the higher B values of finger III residues. The crystallographic structures of five variants were solved, and their analysis shows a variable number of sMamb-1 molecules in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 5, D–G). In addition, comparison of these structures reinforces the variability of finger III that can assume many intermediate conformations between those of sMamb-1A and sMamb-1B. Conversely, the finger II is well defined and virtually identical in all the crystallographic structures (Fig. 5, D–G).

TABLE 2.

Statistics for x-ray data collection, processing and refinement

| PDB code | 5DU1 | 5DZ5 | 5DO6 |

| Mutation | Wild type | Wild type | T23A |

| Protein solution | MMB-1 5 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5 | MMB-1 5 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5 | 200 μg of MMB-1-T23A + 40 μl of 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5 |

| Crystallizationa | 18% PEG 4000, 3% methyl pentanediol, 3% 1,4-dioxane, 1.88 m imidazole malate, pH 6.0 | 30% PEG 600, 0.2 m imidazole malate, pH 7.0 | 21.6% PEG 600, 3.6% PEG 20,000, 72 mm MMTb, pH 4.0, 108 mm MIBb, pH 10.0 |

| Cryoprotectant | 40% SM5, 30% PEG 600, 100 mm AABb 40/60, pH 7.0 | 40% SM5, 30% PEG 600, 100 mm AABb 40/60, pH 7.0 | 40%c CM9, 30% MPEG 550, 100 mm sodium acetate, pH 6.5, 100 mm KI soaked for 1 min |

| Data collection | |||

| Source | ESRF Massif-1 ID30A-1 | ESRF Massif-1 ID30A-1 | Soleil Proxima-2 |

| Method | Automatic data collection | Automatic data collection | Helical scan |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9650 | 0.9650 | 0.9801 |

| Space group | P21 | P41212 | C2221 |

| Unit cell (Å/°) | 39 50.2 46.9/β = 93.4 | 46.8 46.8 80.6 | 55.9 101.0 53.5 |

| Molecular asymmetry | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.0–1.80/1.91–1.80 | 40.5–1.95/2.00–1.95 | 36.1–1.70/1.74–1.70 |

| CC1/2d | 99.7/96.2 | 99.8/45.9 | 99.9/95.7 |

| Rmerge(%) | 6.3/25.7 | 18.3/180.2 | 6.1/40.8 |

| Rp.i.m.(%) | 5.2/21.0 | 17.1/168.7 | 5.7/36.5 |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 13.8/4.35 | 9.66/1.19 | 21.8/4.6 |

| Completeness (%) | 95.3/84.7 | 99.9/100.0 | 97.5/78.7 |

| Multiplicity | 2.98 | 7.5 | 7.12 |

| Structural determination | |||

| Method | Molecular replacement | Molecular replacement | SAD phasing |

| Program | Phaser | MOLREP | AutoSol |

| Model | 5DO6 | 5DO6 | Iodide |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.80 | 1.95 | 1.7 |

| No. of reflections | 16,139 | 6981 | 16,719 (non-anomalous) |

| No. of atoms | 2054 | 1000 | 1171 |

| Rwork (%) | 18.6 | 19.5 | 17.2 |

| Rfree (%) | 23.6 | 24.4 | 20.5 |

| Average B (Å2) | 28.0 | 34.0 | 22.0 |

| r.m.s.d. | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 2.065 | 1.991 | 1.017 |

| Ramachandrane | |||

| Favored (%) | 96 | 97.3 | 97.5e |

| Outliers (no.) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aFor crystallization, resuspended lyophilized protein was crystallized in Cryst Chem plates stored in a cooled incubator at 20 °C.

bBuffers are 100 mm. AAB, sodium acetate; ADA, Bicine; MMT, l-malic acid, MES, Tris (component A pH 4; component B pH 9); sodium malonate, imidazole, boric acid (component A pH 4; B pH 10) (36).

cFor cryoprotection, CM9, 12.5% diethylene glycol + 12.5% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol + 25% glycerol + 12.5% 1,2-propanediol + 12.5% DMSO were used (16); for SM5, 12.5% ethylene glycol + 12.5% glycerol + 12.5% 1,2-propanediol + 12.5% 2,3-butanediol +25% DMSO + 25% 1,4-dioxane (35) were used.

dCC1/2 indicates data quality correlation coefficient (27).

eData were from phenix.refine output (24).

TABLE 3.

List of crystal polymorphs

Crystallization experiments for sMamb-1 variants were carried out with lyophilized peptide redissolved at 5 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.5, in CrysChemTM sitting drop vapor diffusion plates with 1-μl drops of protein and precipitant and stored at a constant temperature incubator at 20 °C starting from optimized crystallization conditions used in the crystallization of wild-type sMamb-1, which were streak-seeded (15). All variants required minor variations in precipitant formulation to yield large crystals, and this, combined with the mutation, has resulted in various polymorphs, in which each variant makes different lattice interactions. The large number of polymorphs is not unusual when screening enzyme-drug complexes (16) but is less usual with three-finger toxins, with the exception of D. angusticeps MT7, for which crystals of various morphology were obtained but none that lead to useful x-ray data until the diiodotyrosine variant was successfully crystallized (37).

| Protein | Space group | Molecules/asymmetric unit | Solvent content | Cell parameters | Cell angles | Resolution | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å | ° | Å | |||||

| Wild type | P21 | 4 | 29.4% | 39. 50.2 46.9 | 90 93.4 90 | 2.0–1.8 | Deposited PDB code 5DU1 |

| Wild type | P41212 | 2 | 26.7% | 46.8 46.8 80.6 | 90 90 90 | 2.8–1.75 | Deposited PDB code 5DZ5 |

| Wild type | P1 | 16 | 43.7% | 46.2 47.6 106.9 | 91.9 90.2 101.9 | 1.97 | Refined R = 24.2% Rfree = 30.1% |

| H21A | P1 | 8 | 41.0% | 46.3 46.6 52.3 | 85.8 86.2 77.3 | 2.05 | Refined R = 22.6% Rfree = 28.8 |

| T23A | C2221 | 2 | 57.2% | 55.9 101.0 53.5 | 90 90 90 | 1.7 | Deposited PDB code 5DO6 |

| F27A | P2 | 12 | 39.3% | 46.3 55.5 124.6 | 90 92.7 90 | 2.5 | Being refined R = 25.1% Rfree = 36.1% |

| R28A | P41212 | 2 | 38.4% | 49.3 49.3 86.4 | 90 90 90 | 1.55 | Refined R = 13.7% Rfree = 22.8% |

| K31A | P2 | (4)a | 41.0%a | 35.2 51.6 59.9 | 90 90.05 90 | 2.5 | Collected |

| I33A | P21 | 8 | 43.0% | 58.9 52.6 73.2 | 90 90.6 90 | 2.85 | Being refined R = 28.5% Rfree = 35.2% |

a These are the predicted values.

FIGURE 4.

Crystallographic structures of sMamb-1 polymorphs. The sMamb-1 structures belong to the three-finger fold toxin family, and the two structures obtained differ on loop III that can form either a short β-strand (sMamb-1A) or a short single turn α-helix (sMamb-1B).

FIGURE 5.

Electron density and asymmetric unit content for four variants of sMamb-1. The various crystal polymorphs that have been obtained for the wild-type and for the various alanine variants show a variable number of sMamb-1 molecules assembled together to form dimers and tetramers that constitute the asymmetric unit of the various polymorphs. The comparison of the structures reinforce the variability of finger III that can assume many intermediate conformations between those of sMamb-1A and sMamb-1B. A, center of symmetry of the well conserved dimer formed by a β-zipper is shown in stick representation. B, assembly of the tetramer is mediated by an ensemble of hydrophobic residues shown in black. C, Leu-32, shown in space-filling spheres, from four different molecules form the center of the ensemble by their interaction with each other. D, H21A variant shows two such tetramers, although the wild-type P21 crystal forms just one. E, loss of Phe-27 side chain by the F27A variant results in 12 molecules in the asymmetric unit. The dimer is preserved but not the integrity of the tetramer, and in the lattice the typical manner in which the tetramers assemble is lost completely. F, in those cases where a single dimer is found in the asymmetric unit such as for the R28A variant, which shares the same polymorph as the P41212 form of the wild-type protein and the T23A variant in the C2221 space group, a symmetry operation rebuilds the tetramer. The tetramers then assemble together in a manner that reproduces the lattice found in the asymetric unit of the polymorphs of lower symmetry. G, I33A substitution is close to the center of symmetry of the well conserved dimer formed by a β-zipper shown in stick representation in A.

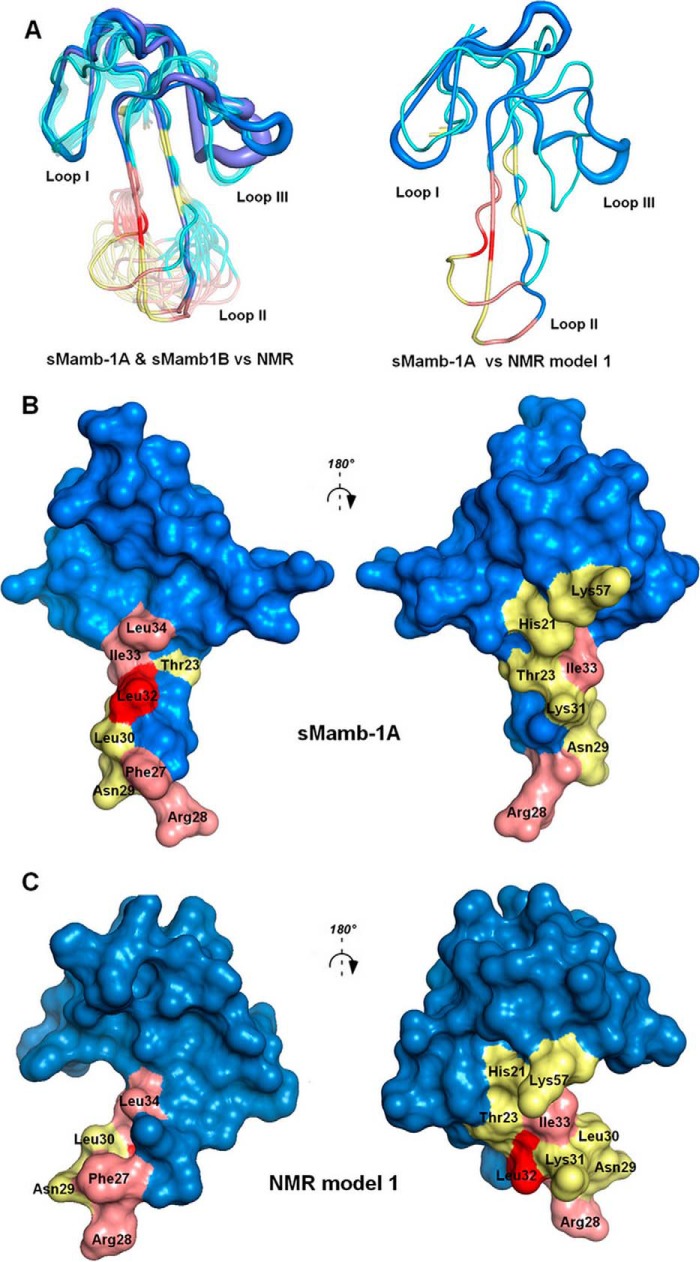

Comparison of the Crystal and NMR Structures of sMamb-1

The crystal structure of sMamb-1 is significantly different from the structure previously obtained by NMR (11, 12). The comparison is best done excluding finger III as the root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) on Cα between the crystallographic structures can be as high as 2 Å if residues 40–57 are included. This is higher than the best agreement with Mamb-1 NMR structure (PDB code 2MJY) (r.m.s.d. 1.6 Å, model 16 versus 5DU1 chain D on Cα residues 1–39). Alanine variants and wild-type sMamb-1 crystal structures obtained in different space groups with up to 16 molecules in the asymmetric unit provide a large diversity of models to compare against an ensemble of 20 models obtained by NMR (Fig. 6). The ensemble of molecules obtained by x-ray crystallography gives an idea of the diversity that exists in the crystal lattice. The regions that show the greatest variation are finger III and to a lesser extent the tip of finger II. The highest r.m.s.d. on Cα for residues 1–39 is 0.7 Å, twice that for the best agreement with any of the NMR models. This stems from variations in the NMR ensemble that are mainly located in the lower part of finger II, a region well conserved among all the crystal structures. In addition, there are differences in the well structured disulfide-stabilized core of the polypeptide between the crystal and NMR structures (Fig. 6A). Among the various conformations for finger III found in the crystal structures, that of sMamb-1A with a single-turn helix is the most ordered and the most frequent conformation observed, and it is the form chosen for comparison because it is likely to be the most representative structure. Within the conformations for finger III, the one that is closest to the NMR structure is sMamb-1B. It contains a short β-sheet, but its B values within the finger III region are higher than for sMamb-1A (thick tubes; Fig. 6A). The observed differences between the crystallographic and NMR structures yield molecular surfaces that are different from each other, mainly in the lower part of finger II, which is well defined in the crystallographic structures (with low B values; Fig. 6, B and C) and shows more conformational variability within the NMR ensemble.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison between NMR and x-ray mambalgin structures. A, left, superimposition of all the NMR structures of sMamb-1 with the two polymorph crystallographic structures shown in blue and violet; right, profile view of the superimposition of NMR model 1 with crystal structure sMamb-1A. Visualization of the residues studied in this paper in the x-ray (B) or NMR structures (C) of Mamb-1, respectively (12, is shown. Modified residues are colored in pink for interacting and yellow for non-interacting. The key residue Leu-32 is shown in red.

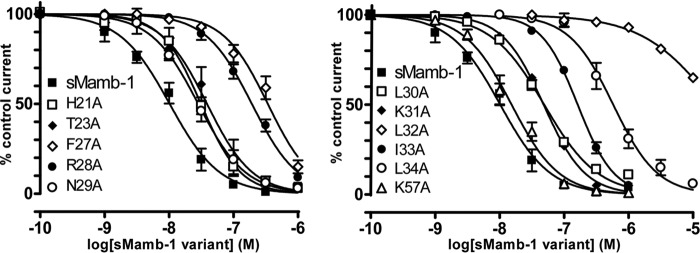

Alanine Scanning Confirms the Role of Finger II and Identifies a Hydrophobic Patch Region in sMamb-1 Crucial for Its Interaction with ASIC1a

Alanine scanning was achieved on both faces of the second loop of the toxin. The alanine variants of the positively charged Arg-28 or of the hydrophobic Phe-27, Leu-32, Ile-33, and Leu-34 induce a significant increase in the IC50 values for ASIC1a channel, suggesting a participation in ASIC1a binding (Fig. 7 and Table 4). Interestingly, the L32A substitution provokes a drastic 3-order of magnitude decrease in the affinity of sMamb-1 for ASIC1a channel (Table 4). However, mambalgin-1 analogues H21A, T23A, N29A, L30A, K31A, and K57A share more or less the same affinity for ASIC1a channel than the wild-type toxin (less than 5-fold decrease in affinity) (Table 4). These data support the interaction of finger II with ASIC1a channel but on a face different from the one initially predicted from the docking of mambalgin (NMR structure) onto the channel (10) where no binding constraints were applied.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of recombinant ASIC1a channels by sMamb-1 variants. Alanine scanning of residues located in or close to the finger II region of sMamb-1. Dose-response curves (% of control current) of the inhibition of homomeric rat ASIC1a channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by sMamb-1 and its variants. See Table 4 for IC50 values and Hill slopes of the sigmoidal fits shown (n = 4–10). For clarity, curves have been split in two panels and the same curve for sMamb-1, which is different from the one shown in Fig. 3 (see legend Table 4), is included in both panels.

TABLE 4.

Pharmacological properties of sMamb-1 variants

IC50 values (mean ± S.E.) of the inhibition of rat ASIC1a current by wild-type and sMamb-1 variants. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference compared with wild-type sMamb-1 (Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn's post hoc test done from 4–10 dose-response curves for each mutant). Note that two-electrode voltage clamp recordings have been obtained using a manual setup, leading to an IC50 value for sMamb-1 that is not exactly the same as the one obtained with the Roboocyte2 automated workstation shown in Fig. 3A (10 versus 3.4 nm, respectively).

| Peptide | IC50 | Hill slope | -Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| nm | |||

| sMamb-1 | 10 ± 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | - |

| H21A | 31 ± 3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 3.1 |

| T23A | 39 ± 5 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 3.8 |

| F27A | 341 ± 29*** | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 33.3 |

| R28A | 193 ± 11** | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 18.8 |

| N29A | 28 ± 2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.8 |

| L30A | 51 ± 3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.8 |

| K31A | 49 ± 2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 4.8 |

| L32A | 21979 ± 4174*** | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 2147.8 |

| I33A | 163 ± 5*** | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 15.9 |

| L34A | 579 ± 59*** | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 56.6 |

| K57A | 15 ± 4 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.5 |

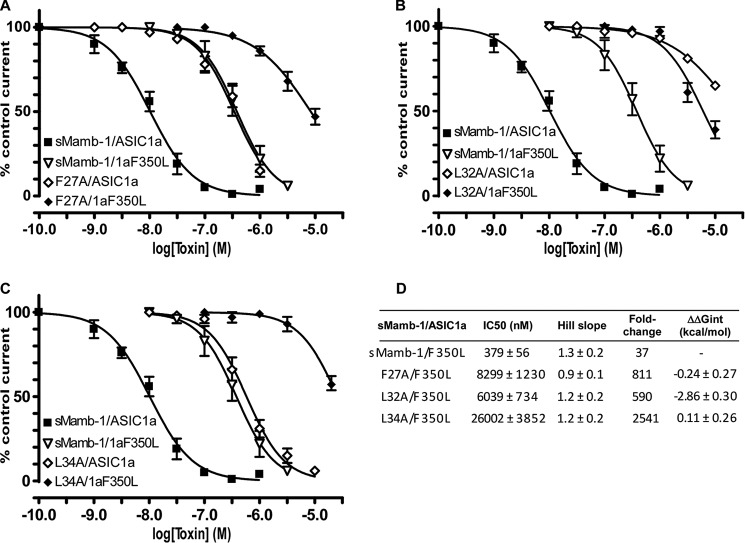

Double Mutant Analysis Suggests Proximity between Leu-32 in Mambalgin-1 and Phe-350 in ASIC1a

Inhibition of the ASIC1a-F350L mutant channel by sMamb-1 variants F27A, L32A, and L34A has been analyzed to address the possible proximity of these residues located into the hydrophobic region of the toxin, with Phe-350 in ASIC1a, which is located near the acidic pocket of the channel and has been shown to be important for the toxin interaction (10). The four possible combinations have been explored for each sMamb-1/ASIC1a double mutant (i.e. F27A/F350L, L32A/F350L, and L34A/F350L; Fig. 8, A–C). A pure additive effect was observed for the double mutants F27A/F350L and L34A/F350L (Fig. 8, A and C), which was characterized by a free coupling energy close to zero (ΔΔGint = −0.24 ± 0.27 and 0.11 ± 0.26 kcal/mol, respectively) (Fig. 8D). This suggests that although Leu-34 and Phe-27 are important for the interface with ASIC1a, they are probably not in contact with Phe-350. Conversely, a high free energy of coupling was calculated for the double mutant L32A/F350L (ΔΔGint = −2.86 ± 0.30 kcal/mol) (Fig. 8, B and D), supporting a proximity between these two residues.

FIGURE 8.

Inhibition of recombinant ASIC1a-F350L channels by the sMamb-1 variants F27A, L32A, and L34A. A–C, dose-response curves (% of control current) of the inhibition of F350L mutant ASIC1a channels by sMamb-1 (n = 4) and its variants F27A (A, n = 5), L32A (B, n = 4), and L34A (C, n = 4). Inhibition of ASIC1a by WT sMamb-1 and its variants was described in Fig. 7. D, pharmacological properties of the ASIC1a-F350L inhibition by sMamb-1 and its variants (calculated from data shown in A–C). The fold-change is relative to ASIC1a inhibition by wild-type sMamb-1 (see Table 4). The variation in free energy of interaction (ΔΔGint) was calculated from the IC50 values shown here and in Table 2. For clarity, curves have been split in three panels (A–C) and the same curves for sMamb-1/ASIC1a (see also Fig. 7) and sMamb-1/ASIC1aF350L are shown in all panels.

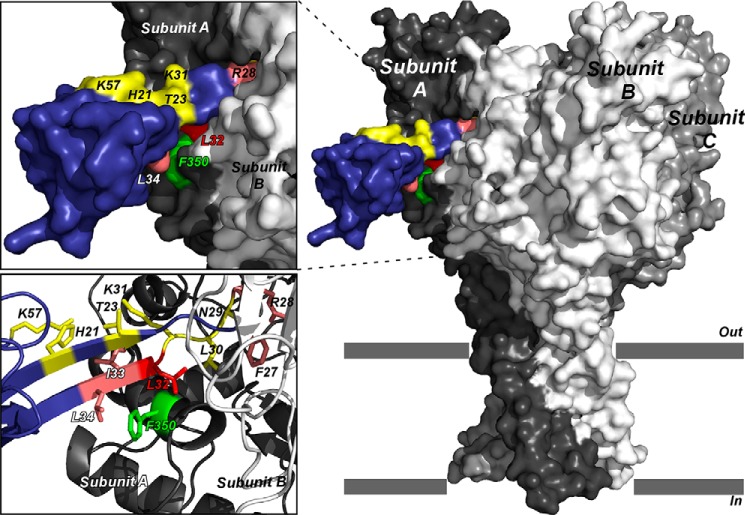

Refined Model of the Interaction between Crystal Structures of sMamb-1 and the Three-dimensional Model of Rat ASIC1a

Taking into account alanine scanning data, double mutant analysis, and x-ray structures, we generated new toxin-channel binding mode predictions by using in silico rigid body docking of toxin crystal structures onto the homology model of rat ASIC1a channel (Fig. 9). Unlike the previous modeling (10), we used the double mutant L32A/F350L pairing to filter output predictions such that only those with specified residues in the binding site are returned. The selected model exhibits a binding mode where toxin residues His-21, Thr-23, Lys-31, and Lys-57 are solvent-exposed, residues Phe-27 and Arg-28 are buried into the acidic pocket of the channel, and residues Leu-32, IIe-33, and Leu-34 are in interaction with the thumb domain of the channel and in proximity with residue Phe-350 in rASIC1a (Fig. 9). Despite the fact that residues Asn-29 and Leu-30 are flanking residues Phe-27 and Arg-28, these residues are likely inserted into the acidic pocket as well, but without deleterious effect when mutated to alanine (Fig. 9). This model is also in good agreement with the fact that mambalgin-2 and -3 inhibit ASIC channels with the same potency as mambalgin-1 because residues at positions 4 and 23, which are different in Mamb-2 and -3, respectively, do not appear to be in interaction with the channel.

FIGURE 9.

Selected binding model of sMamb-1 crystal structure on the three-dimensional model structure of rat ASIC1a. Surface representation of the ASIC1a-mambalgin-1 complex (side view). Subunits are shown with different gray levels and toxin is shown in blue. A close view of the binding interface between ASIC1a and mambalgin-1 is shown on the top left. Mutated residues are colored in pink and yellow for interacting and non-interacting ones, respectively. Key residue Leu-32 is shown in red, and residue Phe-350 in ASIC1a that may form part of the binding surface is indicated in green (10). Bottom left, zoom on the interaction surface between sMamb-1 and ASIC1a, highlighting the proximity between Phe-350 and the toxin.

Discussion

Mambalgins are three-finger folded toxins isolated from the venom of the black mamba Dendroaspis polylepis (mambalgins-1 and -2) and from the venom of the green Mamba Dendroaspis angusticeps (mambalgin-3) (1, 6). These 57-amino acid peptides contain four disulfide bonds and differ by only one residue in position 4 (Tyr to Phe in mambalgin-2) or 23 (Thr to Ile in mambalgin-3) compared with mambalgin-1. Because of their relatively small size, they are, like other members of this family, potentially accessible to stepwise solid phase peptide synthesis. However, two groups recently reported the failure of this strategy to produce these toxins in a stepwise manner and localize the termination of chain extension around residue Lys-31. To address this issue, they proposed for each of them a similar elegant but sophisticated strategy. Mambalgin-2 was therefore obtained by using a combination of solid phase peptide synthesis and native chemical ligation (11), although mambalgin-1 was obtained by using a one-pot chemical synthesis and ligation approach combining azide switch strategy and hydrazide-based native chemical ligation (NCL) (12). Despite a rather long synthesis time, requiring preparation of modified resins, peptide synthesis, purification, and ligation of several toxin fragments, the procedure resulted in milligrams of the two mambalgin toxins, giving mambalgin-1 in 21% yield and mambalgin-2 in 3.5% yield, calculated from the initial quantity of the less abundant peptide fragment.

Interestingly, such a chain termination, associated with low coupling efficiency, was already observed in our laboratory during the synthesis of the three-finger fold polypeptides, such as muscarinic and adrenergic toxins (28, 29), and was located (i) in a β-sheet rich area in the central second loop of the molecules, and (ii) in the N-terminal part of the sequences. We addressed this difficulty by replacing Ser or Thr residues located during the synthetic process just before the critical regions by their corresponding dimethyloxazolidine. These commercially available compounds are called pseudoproline because they disrupt peptide chain aggregation in the same manner as does a proline residue (26). Here again, the use of these dipeptide derivatives, associated with repeated double couplings in sequence 1–5 (LKCYQ) and 30–34 (LKLIL) were very effective in overcoming the difficulties in the synthesis of sMamb-1. For the first time, the full stepwise SPPS of sMamb-1 was successful in only 45 h. Our standard refolding procedure, similar to that used by Pan et al. (12), allowed us to produce sMamb-1 with an overall yield of 6%. Nonetheless, this yield, calculated from the starting synthesis scale, cannot be compared with those resulting from the ligation approach. Actually, Schroeder et al. (11) and Pan et al. (12) published a ligation-refolding yield without taking into account the yields obtained during the synthesis of the various fragments needed for the ligation process, which would decrease their overall values. Moreover, NCL is quite time-consuming, especially in fragment purification by HPLC. For instance, NCL synthesis of mambalgins first required synthesis and purification of three peptide fragments, which was not the case in our process. We demonstrate here that, for mambalgins, optimized SPPS is more competitive in terms of time, quantity of toxin produced, and overall cost than the NCL approaches described previously. Indeed with only two purification steps (crude linear peptide and refolded peptide) multiple milligrams of homogeneous and pure sMamb-1 were obtained and several sMamb-1 alanine variants were readily produced by parallel synthesis, allowing the first structure-activity relationship study of the toxin.

The crystal structures of two wild-type sMamb-1 polymorphs have been determined at 1.75–1.8 Å. Mambalgin-1 has a unique character compared with other three-finger fold toxins, with finger II forming a very long anti-parallel double-stranded β-sheet that protrudes into the solvent and finger III showing unprecedented flexibility. In addition, crystal structures are significantly different from the two structures previously obtained by NMR (11, 12). The region that shows the greatest variations is finger III, although conformational variability within the NMR ensemble is mainly located in the lower part of finger II (11, 12), which is well defined in the crystallographic structures. In addition, several x-ray structures of sMamb-1 variants were solved to ensure that the changes in affinity associated with some alanine substitutions (Table 4) were due to side chain truncation and not the result of conformational changes that might influence finger II and consequently ASIC channel binding. The structures obtained in different crystal forms exclude an involvement of lattice interactions in conformational artifacts. All variants maintain the wild-type conformation and superimposed well with canonical three-finger fold structures.

Indeed, alanine scanning modification in and close to the finger II region of mambalgin-1 identifies several residues (Phe-27, Arg-28, Leu-32, Ile-33, and Leu-34) that significantly decreased the IC50 value of the toxin toward the ASIC1a channel. This provides the experimental confirmation that finger II is crucial for interaction with ASIC1a, as suggested in the ASIC1a-mambalgin initial model we previously described (10). A loss of inhibitory effect was observed with wild-type mambalgin on the mutant channel rASIC1a-Phe-350, suggesting that residue Phe-350, located near the acidic pocket in ASIC1a, could be involved in the binding surface with the toxin (10). Double mutant cycle analysis performed between the F350L mutant in ASIC1a and various sMamb-1 variants suggests proximity between Leu-32 in sMamb-1 and Phe-350 in ASIC1a. Even if interpretation of double mutant cycle analysis should be taken with caution (30), these data further support an interaction of the concave face of the toxin containing Phe-27, Leu-32, and Leu-34 with the receptor-binding site. Leu-34 in sMamb-1 is also important for the interface with ASIC1a and has been proposed to contribute to a hydrophobic patch domain in the finger II region, but our data suggest that this residue may probably not be in close contact with Phe-350 in the channel. Modification of Arg-28 (R28A) at the tip of the Mamb-1 finger II also induces a significant effect on the toxin affinity similar to replacement of Arg-28 by alanine in the spider toxin PcTx1 (31). However, changing Asn-29, Leu-30, and Lys-31 to alanine in mambalgin-1 induces no significant effect on the toxin affinity, whereas mutations of residues at equivalent positions in the spider toxin PcTx1 (Arg-27 and Arg-26), which also binds into the acidic pocket of ASIC1a (32, 33), strongly affect their IC50 values (31). Interestingly, co-crystallization of the PcTx1 toxin bound to the chicken ASIC1 channel (32) shows close interactions of residue Phe-351 of cASIC1 to Trp-7 and Trp-24 in PcTx1, and mutation of these two amino acids to alanine affects the IC50 values in a range equivalent to the L32A and L34A variants in sMamb-1 (31, 34), supporting a similar mechanism. Therefore, although sharing some features, these results highlight differences in the inhibitory mechanisms of mambalgin-1 and PcTx1 on the ASIC1a channel (10). These data clearly identify the binding face of mambalgin-1 on ASIC channels and the crucial role of toxin's loop II (and more particularly Leu-32) in this interaction.

In conclusion, this present work presents the first full stepwise solid phase peptide synthesis of mambalgin-1, confirms the biological activity of this synthetic toxin, and reports the determination of its three-dimensional crystal structure. Furthermore, the functional domain of the toxin for ASIC1a inhibition was delineated, supporting a crucial role of loop II in the toxin-channel interaction. Finally, the proximity of Mamb-1 Leu-32 with Phe-350 in rASIC1a suggested by double mutant cycle experiments and the localization of critical toxin interacting residues were exploited to propose a structural model of the toxin-channel complex.

Author Contributions

G. M., P. K., and M. L. performed the chemical synthesis, purification, and CD spectra analysis of wild-type and sMamb-1 variants. Electrophysiological measurements and in vivo analgesic experiments were carried out by M. S., S. D., T. B., and A. B. E. A. S. and L. T. determined the crystal structures of wild-type and alanine variants of sMamb-1. D. D. performed the structural modeling of the toxin-ASIC channel complex. E. L. and D. S. conceived and designed the project. All the authors made contributions to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Lingueglia team for discussions, M. Lazdunski for support, V. Friend for technical assistance, and C. Chevance for secretarial assistance. The help of the staff at the Soleil beamline Proxima 2A and ESRF beamline Massif1 ID30A-1 and the grant of beamtime are acknowledged with gratitude, in particular to Drs. Shepard and Savko for assistance during data collection. We thank G. Upert for fruitful discussion.

This work was supported by CNRS, INSERM, and Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant ANR-13-BSV4-0009. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 5DU1, 5DZ5, and 5DO6) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- ASIC

- acid-sensing ion channel

- sMamb-1

- synthetic mambalgin-1

- HCTU

- hexafluorophosphate

- NMP

- N-methylpyrrolidone

- NMM

- N-methylmorpholine

- TIPS

- triisopropylsilane

- SPPS

- solid phase peptide synthesis

- r.m.s.d.

- root-mean-square deviation

- Fmoc

- N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- NCL

- native chemical ligation

- RP-HPLC

- reverse phase HPLC

- Bicine

- N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine.

References

- 1.Diochot S., Baron A., Salinas M., Douguet D., Scarzello S., Dabert-Gay A. S., Debayle D., Friend V., Alloui A., Lazdunski M., and Lingueglia E. (2012) Black mamba venom peptides target acid-sensing ion channels to abolish pain. Nature 490, 552–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldmann R., Champigny G., Bassilana F., Heurteaux C., and Lazdunski M. (1997) A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature 386, 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deval E., and Lingueglia E. (2015) Acid-sensing ion channels and nociception in the peripheral and central nervous systems. Neuropharmacology 94, 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noël J., Salinas M., Baron A., Diochot S., Deval E., and Lingueglia E. (2010) Current perspectives on acid-sensing ion channels: new advances and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 3, 331–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wemmie J. A., Taugher R. J., and Kreple C. J. (2013) Acid-sensing ion channels in pain and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 461–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron A., Diochot S., Salinas M., Deval E., Noël J., and Lingueglia E. (2013) Venom toxins in the exploration of molecular, physiological and pathophysiological functions of acid-sensing ion channels. Toxicon 75, 187–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baron A., and Lingueglia E. (2015) Pharmacology of acid-sensing ion channels– physiological and therapeutical perspectives. Neuropharmacology 94, 19–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolf C. J. (2013) Pain: morphine, metabolites, mambas, and mutations. Lancet Neurol. 12, 18–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diochot S., Alloui A., Rodrigues P., Dauvois M., Friend V., Aissouni Y., Eschalier A., Lingueglia E., and Baron A. (2015) Analgesic effects of mambalgin peptide inhibitors of acid-sensing ion channels in inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas M., Besson T., Delettre Q., Diochot S., Boulakirba S., Douguet D., and Lingueglia E. (2014) Binding site and inhibitory mechanism of the mambalgin-2 pain-relieving peptide on acid-sensing ion channel 1a. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13363–13373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder C. I., Rash L. D., Vila-Farrés X., Rosengren K. J., Mobli M., King G. F., Alewood P. F., Craik D. J., and Durek T. (2014) Chemical synthesis, 3D structure, and ASIC binding site of the toxin mambalgin-2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 1017–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan M., He Y., Wen M., Wu F., Sun D., Li S., Zhang L., Li Y., and Tian C. (2014) One-pot hydrazide-based native chemical ligation for efficient chemical synthesis and structure determination of toxin Mambalgin-1. Chem. Commun. 50, 5837–5839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidalgo P., and MacKinnon R. (1995) Revealing the architecture of a K+ channel pore through mutant cycles with a peptide inhibitor. Science 268, 307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stura E. A., Nemerow G. R., and Wilson I. A. (1992) Strategies in the crystallization of glycoproteins and protein complexes. J. Cryst. GroWTh 122, 273–285 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stura E. A., and Wilson I. A. (1991) Applications of the streak seeding technique in protein crystallization. J. Cryst. GroWTh 110, 270–282 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vera L., Antoni C., Devel L., Czarny B., Cassar-Lajeunesse E., Rossello A., Dive V., and Stura E. A. (2013) Screening using polymorphs for the crystallization of protein-ligand complexes. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 1878–1888 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duran D., Couster S., Le D., K., Delmotte A., Fox G., Meijers R., and Shepard W. (2013) PROXIMA 2A– a new fully tunable micro-focus beamline for macromolecular crystallography. J. Phys. Confer. Ser. 425, 012005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terwilliger T. C., Adams P. D., Read R. J., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Afonine P. V., Zwart P. H., and Hung L. W. (2009) Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 582–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCoy A. J., Storoni L. C., and Read R. J. (2004) Simple algorithm for a maximum-likelihood SAD function. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1220–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terwilliger T. C. (2002) Automated structure solution, density modification and model building. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1937–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and CoWTan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murshudov G. N., Skubák P., Lebedev A. A., Pannu N. S., Steiner R. A., Nicholls R. A., Winn M. D., Long F., and Vagin A. A. (2011) REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 355–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., et al. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vagin A., and Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutter M., Nefzi A., Sato T., Sun X., Wahl F., and Wöhr T. (1995) Pseudo-prolines (Psi-Pro) for accessing inaccessible peptides. Pept. Res. 8, 145–153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diederichs K., and Karplus P. A. (2013) Better models by discarding data? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 69, 1215–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mourier G., Dutertre S., Fruchart-Gaillard C., Ménez A., and Servent D. (2003) Chemical synthesis of MT1 and MT7 muscarinic toxins: critical role of Arg-34 in their interaction with M1 muscarinic receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fruchart-Gaillard C., Mourier G., Blanchet G., Vera L., Gilles N., Ménez R., Marcon E., Stura E. A., and Servent D. (2012) Engineering of three-finger fold toxins creates ligands with original pharmacological profiles for muscarinic and adrenergic receptors. PLoS One 7, e39166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chowdhury S., Haehnel B. M., and Chanda B. (2014) A self-consistent approach for determining pairwise interactions that underlie channel activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 144, 441–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saez N. J., Mobli M., Bieri M., Chassagnon I. R., Malde A. K., Gamsjaeger R., Mark A. E., Gooley P. R., Rash L. D., and King G. F. (2011) A dynamic pharmacophore drives the interaction between Psalmotoxin-1 and the putative drug target acid-sensing ion channel 1a. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 796–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baconguis I., and Gouaux E. (2012) Structural plasticity and dynamic selectivity of acid-sensing ion channel-spider toxin complexes. Nature 489, 400–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson R. J., Benz J., Stohler P., Tetaz T., Joseph C., Huber S., Schmid G., Hügin D., Pflimlin P., Trube G., Rudolph M. G., Hennig M., and Ruf A. (2012) Structure of the acid-sensing ion channel 1 in complex with the gating modifier Psalmotoxin 1. Nat. Commun. 3, 936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saez N. J., Deplazes E., Cristofori-Armstrong B., Chassagnon I. R., Lin X., Mobli M., Mark A. E., Rash L. D., and King G. F. (2015) Molecular dynamics and functional studies define a hot spot of crystal contacts essential for PcTx1 inhibition of acid-sensing ion channel 1a. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172, 4985–4995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciccone L., Tepshi L., Nencetti S., and Stura E. A. (2015) Transthyretin complexes with curcumin and bromo-estradiol: evaluation of solubilizing multicomponent mixtures. New Biotechnol. 32, 54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman J. (2004) Novel buffer systems for macromolecular crystallization. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 610–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fruchart-Gaillard C., Mourier G., Marquer C., Stura E., Birdsall N. J., and Servent D. (2008) Different interactions between MT7 toxin and the human muscarinic M1 receptor in its free and N-methylscopolamine-occupied states. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1554–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]