Abstract

KCNQ (voltage-gated K+ channel family 7 (Kv7)) channels control cellular excitability and underlie the K+ current sensitive to muscarinic receptor signaling (the M current) in sympathetic neurons. Here we show that the novel anti-epileptic drug retigabine (RTG) modulates channel function of pore-only modules (PMs) of the human Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 homomeric channels and of Kv7.2/3 heteromeric channels by prolonging the residence time in the open state. In addition, the Kv7 channel PMs are shown to recapitulate the single-channel permeation and pharmacological specificity characteristics of the corresponding full-length proteins in their native cellular context. A mutation (W265L) in the reconstituted Kv7.3 PM renders the channel insensitive to RTG and favors the conductive conformation of the PM, in agreement to what is observed when the Kv7.3 mutant is heterologously expressed. On the basis of the new findings and homology models of the closed and open conformations of the Kv7.3 PM, we propose a structural mechanism for the gating of the Kv7.3 PM and for the site of action of RTG as a Kv7.2/Kv7.3 K+ current activator. The results validate the modular design of human Kv channels and highlight the PM as a high-fidelity target for drug screening of Kv channels.

Keywords: channel activation, epilepsy, gating, ion channel, potassium channel, KCNQ, Kv7, KvLm, retigabine, pore module

Introduction

Members of the voltage-gated K+ (Kv)5 channel family 7 (Kv7, otherwise known as KCNQ) are key determinants of cellular excitability in the heart (Kv7.1) and brain (Kv7.2–7.5) (1, 2). There is no crystal structure for any member of Kv7 family, although they constitute prominent targets of clinically relevant drugs, and their dysfunction is implicated in a number of human diseases (1–3). In their physiological context, Kv7 channels open at subthreshold voltages and are modulated by G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathways via secondary messengers (1, 2). In neurons, Kv7.2/3 heteromers presumably underlie the K+ current sensitive to muscarinic receptor signaling, the M current (4–7). Mutations in the Kv7.2 (8–11) and Kv7.3 (11, 12) subunits underlie a form of inherited human epilepsy: benign familial neonatal convulsions. Retigabine (RTG, ezogabine) (ethyl N-[2-amino-4-[(4-fluorophenyl)methylamino]phenyl]carbamate), an anticonvulsant drug approved for the adjunctive treatment of partial-onset seizures in adults, is thought to act primarily by increasing the propensity to reside in the open conformation of neuronal Kv7.2/3 channels (13–15), leading to hyperpolarization of the membrane potential toward the K+ equilibrium potential and, therefore, attenuating the repetitive firing pattern that underlies seizures (16–19). However, the molecular mechanism by which RTG opens the Kv7.2/3 channels is not well understood. Remarkably, cardiac Kv7.1 channels are insensitive to RTG (15, 20, 21). This exquisite specificity affords an opportunity to dissect the target site of action on Kv7.2/3 channels.

We selected the PM of the Kv7 (KCNQ) channel family because the amino acid sequence of its pore and voltage sensor modules is similar to that of KvLm, a bacterial Kv for which we solved the structure of the pore-only module in a lipid environment at atomic resolution (22). We exploit the structural independence of the pore and sensor modules of Kvs (22–24) to produce homomers (6, 7, 13–15, 20, 21, 25–27) and heteromers (6, 7, 13–15, 20, 25–27) of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 PMs by in vitro transcription and translation. Single-channel activity of the purified pore-only module (PM) was characterized after reconstitution in lipid bilayers. Single-channel currents through purified Kv7.2, Kv7.3, and Kv7.2/Kv7.3 PMs are K+-selective and blocked by specific Kv7 channel blockers (28). Interestingly, RTG potentiates channel function by increasing single channel open probability in all functional assemblies of Kv7 PMs, validating that the site of action of RTG is embodied in the sensorless PM. Furthermore, a key mutation in Kv7.3 PM W265L renders the channel insensitive to RTG, further confirming the PM of Kv7 channels as the interaction site for the drug.

Experimental Procedures

Gene Synthesis of Kv7.2, Kv7.3 PM WT, and Mutants

The DNA sequences of the human Kv7.2 (gi 26051260) and Kv7.3 (gi 5921785) PMs were synthesized codon-optimized for Escherichia coli expression with a C terminus His6 tag by GENEWIZ and cloned into the pT7-SC1 vector (29). The amino acid sequences of the Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 PMs extended from Met-211 to Arg-333 and from Asp-241 to Lys-373. Mutants were synthesized using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Protein Expression and Purification

Cell-free (in vitro transcription/translation) expression of the PMs was accomplished using the E. coli T7 S30 extract system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the instructions of the manufacturer but supplemented at the reaction surface with liposomes (10% molar 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) plus 90% molar 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) in 0.2 m KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml. All lipids used were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). At the end, the reaction was incubated with DNase (1 μg/ml final) for 10 min at room temperature, followed by incubation in 1 mm dodecyl maltoside (Anatrace, Maumee, OH) for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was then subjected to centrifugation at 1000 × g, and the supernatant was incubated with His-60 nickel magnetic beads (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) for 30 min. Following a wash with 0.2 m KCl, 10 mm imidazole, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), and 1 mm dodecyl maltoside, proteoliposomes were eluted with 0.2 m KCl, 0.3 m imidazole, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), and 1 mm dodecyl maltoside. Purification of the His-tagged PMs was verified by Western blotting utilizing a primary rabbit anti-penta-His BSA-free antibody (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, catalog no. 34660) and a secondary goat anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated fluorescent antibody (Life Technologies, catalog no. A21058) (Fig. 1A).

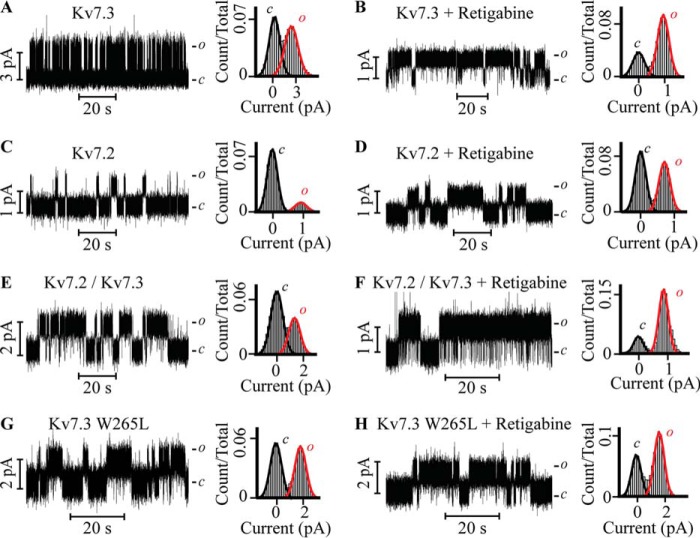

FIGURE 1.

Single-channel recordings of the in vitro transcription and translation-purified Kv7.3 PM reconstituted in droplet lipid bilayers. A, Western blotting of Kv7.3 PM proteoliposomes purified by nickel affinity. Lane 1, Mr standards. Lane 3, flow-through (FT). Lane 5, 10 mm imidazole wash (W). Lane 7, 300 mm imidazole eluate (E) of the purified Kv7.3 PM used for reconstitution. The purified protein migrates as a monomer with an apparent Mr of ∼15. B–E, representative current versus voltage (IV) relationship of the Kv7.3 PM (left panels) at V = 150 mV (B), V = 100 mV (C), V = 50 mV (D), and V = 30 mV (E) recorded in 0.5 m KCl. Bursting activity is readily discerned in the center panels, in which the currents are displayed at a faster time resolution. The corresponding normalized all-point current histograms (right panels) for the entire analyzed record are fitted to the Gaussian curve. c and o denote the closed and open states of the channel, respectively. Kv7.3 PM exhibits a single-channel slope conductance of 27 ± 3 pS.

Single-channel Recordings Using Droplet Lipid Bilayers

Liposomes were prepared as described previously (22, 23, 30, 31). For reconstitution, the protein was diluted ∼100- to 200-fold into preformed liposomes in 0.5 m KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4). The experiments were performed in 90% 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine supplemented with 10% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate symmetric bilayers in 0.5 m KCl to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. Single-channel currents were recorded from droplet lipid bilayers as described previously (22, 23, 30–32), with proteoliposomes always added to the cis aqueous compartment. The electrode in the cis compartment was connected to the grounded end of the amplifier head stage. The electrode in the trans compartment was connected to the working end of the amplifier. In the indicated experiments, NaCl was injected to a final concentration of 0.2 m, whereas amitriptyline (Sigma-Aldrich, Carlsbad, CA) and linopirdine (1,3-dihydro-1-phenyl-3,3-bis(4-pyridinylmethyl)-2H-indol-2-one) (Sigma-Aldrich) were injected to a final concentration of 10 and 50 μm respectively, using a Nano injector (WPI, Sarasota, FL). Linopirdine and amitriptyline stocks of 1 mm were made in 200 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4). The known sided-block by linopirdine was used to establish the channel orientation in lipid bilayers; therefore, the extracellular side of the channels was assigned to the cis droplet. Only records in which this channel orientation was observed were analyzed. A retigabine (LGM Pharma, Beit Shemesh, Israel) stock of 3 mm was made in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted further to 10 μm in 10% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate containing liposomes. The liposomes containing RTG were extruded through 100-μm filter (Avanti Polar Lipids). The protein was added to the RTG-containing liposomes and incubated for 2–5 h prior to the single-channel recordings.

Single-channel Acquisition and Analysis

Single-channel acquisition and analysis were performed as described previously (22, 23, 30–32) with slight modifications. Segments of continuous recordings in the range of 50 s ≤ t ≤ 500 s were used for analysis. The currents were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered to 2 kHz. Additional offline filtering of 1 kHz was applied to all recordings. To avoid the detection of erroneous events, the receiver's dead time (td) was set at 300 μs. All current recordings were measured at V = +100 mV unless indicated otherwise. The calculated values are reported as mean ± S.D.

Statistical Analysis

N and n denote number of events analyzed and the number of single-channel experiments, respectively. For the statistical analysis of single-channel parameters of the indicated Kv7 PMs, N (n) were as follows: Kv7.3 = 73,179 (7); Kv7.3 + RTG = 4140 (6); Kv7.2 = 3286 (5); Kv7.2 + RTG = 2857 (5); Kv7.2/Kv7.3 = 11,911 (5); Kv7.2/Kv7.3 + RTG = 960 (5); W265L-Kv7.3 = 4291 (4); and W265L-Kv7.3 + RTG = 3319 (4).

Molecular Modeling and Retigabine Docking

Two structural models of the Kv7.3 PM were constructed using the KvLm PM (PDB code 4H33) and Kv1.2–2.1 PM (PDB code 2R9R) structures as templates in YASARA (YASARA Bioscience, Vienna, Austria). Docking of RTG to the Kv7.3 PM model utilizing the Kv 1.2–2.1 PM structure was performed using the VINA (33) docking algorithm in YASARA, allowing for limited side chain flexibility by docking onto 10 model structures of Kv7.3 of equal energy while exploring full ligand flexibility. The two lowest-energy docking models in which RTG forms an interaction with Trp-265 in the Kv7.3 PM are shown.

Results

The Sensorless PM of Kv7.3 Forms K+-selective Channels after Reconstitution in Lipid Bilayers

Kv7.3 PM was expressed by coupled in vitro transcription and translation and purified by a nickel affinity column (see “Experimental Procedures”). To verify the molecular weight of the synthesized and purified sample, a small volume was loaded on a 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad) and visualized by Western blotting (Fig. 1A). A distinct band with an apparent Mr of ∼15 was observed in the eluate, in agreement with the calculated mass of the Kv7.3 PM of 16.3 kDa. We adopted the purified eluted sample for subsequent protein reconstitution in droplet lipid bilayers. A family of single-channel currents of the Kv7.3 PM recorded at the indicated depolarizing voltages in symmetrical 0.5 m KCl is illustrated (Fig. 1, B–E). The PM opens frequently, and the pattern of activity is characterized by bursts of openings interrupted by quiescent periods. The single-channel current increases with voltage in an ohmic manner with a slope conductance (γ) of 27 ± 3 pS. The corresponding normalized all-point histograms (Fig. 1, B–E, right panels) show that the open probability of the channel (Po) increases from 0.30 ± 0.01 at 30 mV to 0.50 ± 0.01 at 150 mV. Therefore, in the absence of the sensor, the Kv7.3 PM retains only vestigial voltage-gating, as observed previously in the PM of KvLm (24). The Kv7.3 PM also retains the classical K+ selectivity over Na+. In symmetric 0.5 m KCl solutions, γ = 28 ± 3 pS at +50 mV (Fig. 2A). Injection of 0.2 m NaCl to the trans aqueous compartment reduces γ to 10 ± 2 pS, with the openings featuring a brief mean open time (τopen) (Fig. 2B).

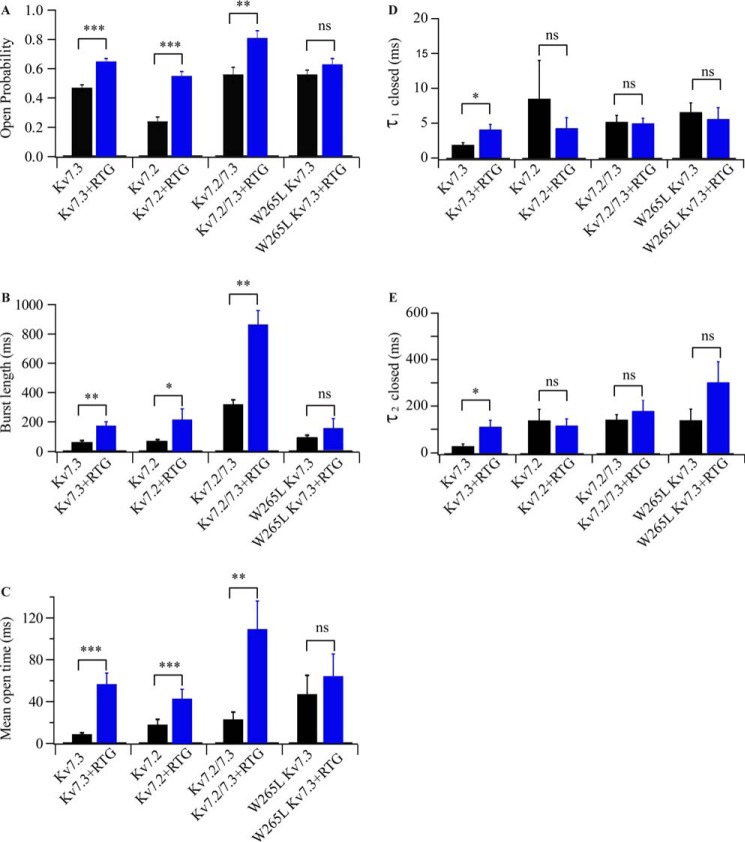

FIGURE 2.

The reconstituted Kv7.3 PM recapitulates K+ selectivity and blocker sensitivity of authentic Kv7.3 channels. A, Kv7.3 PM currents recorded at 50 mV in 0.5 m KCl before the injection of NaCl. B, after 5 min of channel activity, 0.2 m NaCl was injected in the trans droplet, evoking an immediate decrease in the current. C, Kv7.3 PM currents recorded under bi-ionic conditions (0.5 m KCl in the cis droplet and 0.5 m NaCl in the trans droplet). No currents were detected at +50 mV when Na+ was the current-carrying ion, whereas currents were evoked readily at −50 mV when K+ was the current-carrying species. Channel activity ceased at +50 mV in the later part of the recording. D, representative single-channel recordings of the Kv7.3 PM reconstituted under physiological salt conditions (0.15 m KCl) measured at 100 mV (left and center panels) and the all-point current histogram for the entire analyzed record (right panel). The segment of the record demarcated by the red line in the left panel is displayed at higher time resolution in the center panel. E, Kv7.3 PM single-channel activity recorded at 100 mV in 0.5 m KCl before the injection of the sided blocker linopirdine (left panel) and after the injection of 50 μm linopirdine in the trans side (center panel). In the same experiment, after 2 min of recording activity, 50 μm linopirdine was injected in the cis side, resulting in an immediate block (right panel). F and G, Kv7.3 PM single-channel activity recorded at 100 mV in 0.5 m KCl before the injection of the extracellular blocker amitriptyline (F) and after the injection of 10 μm amitriptyline in the cis side (G). c and o denote the closed and open states of the channel, respectively.

In a separate set of experiments (Fig. 2C), under bi-ionic conditions (0.5 m KCl in the cis compartment and 0.5 m NaCl in the trans compartment), no current was detected at +50 mV when Na+ was the expected current carrying species, whereas channel activity was evoked immediately at −50 mV, conditions under which K+ is the current carrying ion. At the end of the recording, the voltage was switched to +50 mV, and no current was detected, as anticipated for a K+-selective channel (Fig. 2C). To determine whether the Kv7.3 PM retains the permeation properties under physiological ionic conditions, channel activity was recorded in 0.15 m KCl (Fig. 2D). The γ of 9 ± 2 pS at +100 mV recapitulates the previously measured γ for heterologously expressed Kv7.3 recorded in 0.15 m KCl (34), suggesting that deletion of voltage sensors had little effect on the permeation properties of the Kv7.3 PM channel and that high salt conditions (0.5 m KCl) are an appropriate means to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio for the purpose of single-channel analysis. These results indicate that the Kv7.3 PM recapitulates the permeation properties characteristic of the Kv7.3 channel (20, 26).

To ascertain that the Kv7.3 PM exhibits the pharmacological specificity of the full-length channel, we explored the activity of two known blockers/modulators. To determine the orientation of the channel in the lipid bilayer, we utilized the Kv7 channel blocker linopirdine, known to block Kv7 channels expressed in cells when applied from the extracellular side but not from the cytosol (28). Injection of 50 μm linopirdine into the trans compartment (Fig. 2E, center panel) has no discernible effect on γ and Po of the reconstituted PM. In sharp contrast, injection of 50 μm linopirdine into the cis compartment during the same experiment blocks the single-channel currents (Fig. 2E, right panel). This indicates that the Kv7.3 PM is oriented in the lipid bilayer predominantly with the intracellular side facing the trans compartment, whereas the extracellular side faces the cis compartment. Therefore, at positive potentials, the physiologically relevant outward K+ flux is assayed. The result that linopirdine blocks only when applied to the compartment corresponding to the extracellular side of the channels establishes that the Kv7.3 PM retains the linopirdine sensitivity of the authentic full-length channel when expressed in a cellular context.

Next we assayed the effect of the widely prescribed tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline, a Kv7.3 channel blocker shown to act from the extracellular side (35), on the single channel currents of the Kv7.3 PM. Injection of 10 μm amitriptyline in the cis compartment (Fig. 2, F and G), equivalent to the extracellular aqueous compartment in cells, decreased single-channel currents to an undetectable amplitude, confirming amitriptyline as a blocker of the Kv7.3 PM and validating the pharmacological integrity of the Kv7.3 PM.

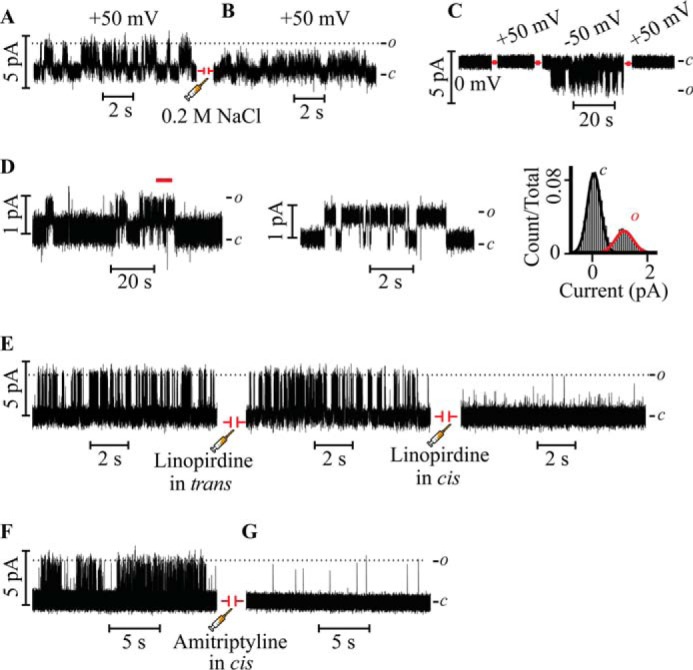

Retigabine Stabilizes the Conductive Conformation of the Reconstituted Kv7 Pore Module

To determine the functional intactness of the Kv7.3 PM, we used RTG as a selective probe, given its well characterized activity as Kv7.3 channel opener in cellular assays (15, 20). Specifically, we asked whether the interaction between RTG and the Kv7.3 PM suffices to recapitulate the RTG action on the full-length Kv7.3 channel expressed in cells. Accordingly, the Kv7.3 PM was incubated with 10 μm RTG prior to the single-channel recordings. As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, RTG promotes prolonged bursts of discrete channel activity with a 3-fold increased longer burst length, 1.4-fold increased Po, 7-fold increased τopen, 2-fold increase in τ1closed, and 3-fold increase in τ2closed (Figs. 3B and 4). These results define the activity of RTG in the Kv7.3 PM as a stabilizer of the conductive conformation of Kv7.3 PM that emulates the RTG sensitivity of the full-length Kv7.3 channel (15, 20). The implication is that the sensorless PM is sufficient to confer RTG sensitivity to the authentic Kv7.3 channel.

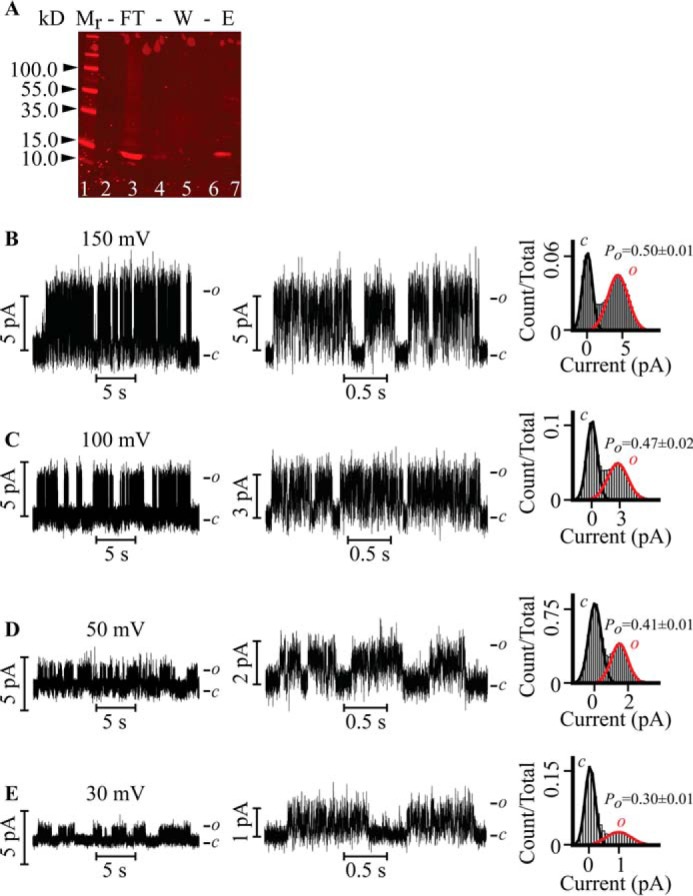

FIGURE 3.

The reconstituted Kv7.3 PM, Kv7.2 PM, and Kv7.2/Kv7.3 PM recapitulate retigabine (activator) sensitivity of the authentic counterparts, whereas the mutant W265L is RTG-insensitive. A, C, E, and G, current recordings of the indicated Kv7 PM channels prior to the application of RTG with the corresponding normalized all-point histograms (right panels). B, D, F, and H, the indicated Kv7 PM currents produced by preincubation with 10 μm RTG and the corresponding normalized all-point histograms (right panels). Note that the height of histograms in an open state (red) indicates a higher open probability in the presence of RTG compared with the absence of RTG, except for the mutant channels (H). c and o denote the closed and open states of the channel, respectively. The recordings were performed in 0.5 m KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) at V = 100 mV. The orientation of the Kv channels in the bilayer was established by amitriptyline block (as shown in Fig. 2) at the end of each experiment. The calculated single channel conductances of Kv PMs were as follows: Kv7.3 = 27 ± 3 pS, Kv7.3 + RTG = 10 ± 2 pS, Kv 7.2 = 9 ± 1 pS, Kv7.2 + RTG = 7 ± 1 pS, Kv7.2/Kv7.3 = 15 ± 3 pS, Kv7.2/Kv7.3 + RTG = 11 ± 3 pS, W265L Kv7.3 = 18 ± 2 pS, and W265L Kv7.3 + RTG = 15 ± 2 pS.

FIGURE 4.

Single-channel parameters of Kv7 pore modules in the absence or presence of retigabine. A–E, single-channel Po (A), median burst length (B), mean open time (C), and mean closed times (τ1 closed and τ2 closed) of the indicated Kv7 PMs in the absence (black columns) or presence (blue columns) of 10 μm RTG (D and E). All experiments were performed in 0.5 m KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) at +100 mV. Calculated values are presented as mean ± S.E. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test. p > 0.05 indicates that two groups in question are not significantly different (ns). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Given that Kv7.2/3 heteromers are thought to predominantly determine the neuronal M current, we next characterized the single-channel properties of Kv7.2 PM homomers and Kv7.2/3 PM heteromers in the absence and presence of RTG (Figs. 3, C–F, and 4). Kv7.2 PM homomers exhibit a γ of 9 ± 1 pS, whereas Kv7.2/3 PM heteromers exhibit a γ of 15 ± 3 pS in symmetric 0.5 m KCl at +50 mV (Fig. 3, C and E). Both assemblies also have distinct gating patterns. Po and burst length for the Kv7.2/3 PM heteromer increased ∼2.3-fold and ∼4.3-fold in comparison with Kv7.2 PM homomers (Po = 0.24 ± 0.03 and burst length = 73 ± 8 ms, Fig. 4, A and B). Notably, a single population of conductance and gating parameters was observed in records of Kv7.2/3 PM heteromer assemblies, suggesting that Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits oligomerize with a predominantly unique stoichiometry when coexpressed in a cell-free in vitro transcription and translation system to generate functional assemblies with gating and permeation features different from either Kv7.2 or Kv7.3 homomers. In additional semblance to the reported features of the heteromer expressed in cells (6, 7, 13–15, 20, 25–27), the Kv7.2/3 heteromeric PM (Fig. 3E) displays a statistically significant longer burst length than either homomeric assembly (Figs. 3, A and C, and 4, A and B), implying that co-assembly of the Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits generates a more stable conductive conformation of the PM (Fig. 4).

Most importantly, we queried whether the RTG binding site present in Kv7.3 PM (Figs. 3B and 4) remained intact in Kv7.2 PM and Kv7.2/3 PM channels. In homomeric Kv7.2 PM channels, incubation with RTG promoted an ∼2.5-fold increase in Po, τopen, and burst length (Figs. 3, C and D, and 4, A–C). In comparison, when the Kv7.2/3 PM heteromers were incubated with RTG, the Po increased 1.5-fold, τopen increased 4.7-fold, and burst length increased 3-fold (Figs. 3, E and F, and 4). The implication is that RTG stabilizes the open conformation of both Kv7.2 PM and Kv7.2/3 PM channels, as observed for the native channels in the cellular context (13, 14, 20, 21, 36).

How Does RTG Modulate the PM Conformation?

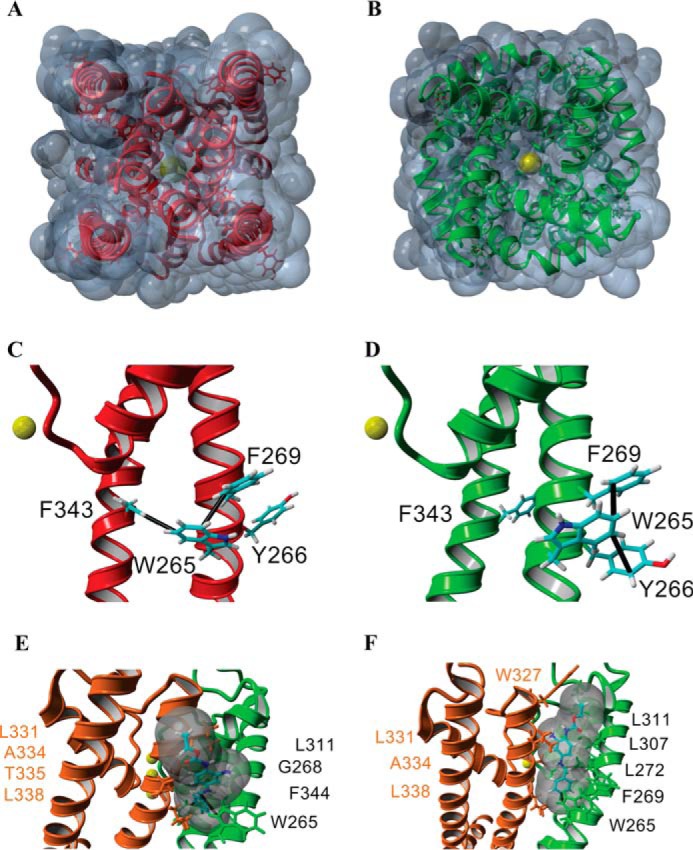

A tryptophan at position 265 of Kv7.3, conserved in Kv7.2 (Trp-236) (21) to Kv7.5 but absent in Kv7.1, was identified as a necessary constituent of the RTG binding site (20). Accordingly, a mutant Kv7.3, W265L, was studied, and, as shown in Fig. 3, G and H, it is practically insensitive to RTG given that, in its absence, the characteristic γ, Po, burst length, τopen, τ1closed, and τ2closed are all equal, within error, to those measured after incubation with 10 μm RTG (Figs. 3, G and H, and 4). Importantly, the Po of the mutant is higher than that of the Kv7.3 WT and equal, within error, to that observed for the Kv7.3 WT in the presence of RTG (Fig. 4A). To further examine this, we turned to homology modeling, using as templates the open pore conformation of the Kv1.2–2.1 channel (PDB code 2R9R) (37), the closed structure of KvLm PM (PDB code 4H33) (22), and in silico docking in YASARA (YASARA Biosciences). The solvent-exposed surface depiction of the homology model on the basis of the KvLm closed channel structure shows that the Kv7.3 channel is closed (Fig. 5A). In this closed conformation model, Trp-265 is shown to form two distinct intrasubunit π-π (π stacking) interactions: one with Phe-269 within the same transmembrane helix (S5 following the convention of full-length channels) and the other with Phe-343 in the sixth transmembrane segment (S6 in full-length channels) (Fig. 5B). In contrast, a solvent-accessible surface representation of the Kv7.3 homology model utilizing the PDB code 2R9R open channel template shows that the channel is open (Fig. 5C). In this open model conformation, the indole ring of Trp-265 in a Kv7.3 subunit forms two π-π intrasubunit interactions with Tyr-266 and Phe-269 within the same transmembrane segment, S5 (Fig. 5D). Therefore, the models suggest that, in transitioning from closed to open, a π-π interaction that holds S5 to S6 within the same subunit is lost in the Kv7.3 PM and replaced by a π-π interaction within S5.

FIGURE 5.

Structural model for the gating transition of the pore in Kv7.3 and the site of action of RTG. A–F, homology models of the Kv7.3 PM in the closed (red, A and C) and open conformations (green, B and D; orange/green, E and F) built using the closed channel structure of KvLm (PDB code 4H33) (22) and open channel structure of Kv1.2-Kv2.1 (PDB code 2R9R) (37). The end view of a solvent-accessible surface map of the closed model (A) shows that the channel is occluded, whereas a similar depiction of the open channel model (B) delineates the presence of K+ in the permeation pathway, consistent with the passage of K+ (yellow, B) through the channel pore. Side views of a single subunit in the closed conformation (C) and in the open conformation (D) highlight predicted π-π interactions (black lines) in each monomer that delineate a change in the interaction partners when the channel gates open. E and F, two low-energy docking models of RTG onto the open channel module (side views), both involving a π-π interaction between Trp-265 and RTG, with amino acids forming the pocket (distance between protein and RTG, <5 Å) labeled explicitly.

The described Kv7.3 PM gating model proposes the testable hypothesis that the π-π interaction between Trp-265 in S5 and Phe-343 in S6 is a major determinant of the stability of the closed conformation of the PM. In experimental agreement, the Po of the reconstituted Kv7.3 W265L mutant PM is observed to be larger than the WT. When expressed heterologously in cells, the Kv7.3 mutant W265L has been shown to have a left-shifted voltage of activation relative to the wild type (20), demonstrating a higher probability of finding the channel open at lower potentials and justifying the proposed role for Trp-265 in determining closed structure stability. To understand how a presumed RTG interaction with Trp-265 in the reconstituted PM and also in cells destabilizes the closed conformation of the Kv7.3 PM (13–15), we docked RTG on the open model structure. The two lowest-energy docking models in which RTG interacts with Trp-265 suggest that the aromatic ring in RTG forms a π-π interaction with Trp-265 (Fig. 5, E and F). The model presented here differs from an earlier model proposed by Lange et al. (38), particularly in the orientation of RTG within the same binding pocket. In their model, RTG is not positioned to form a π-π interaction with Trp-265. Because, in all our calculated models, RTG fails to form a strong interaction with Phe-343 in S6, we propose that RTG stabilizes Kv7.3 PM by preventing Trp-265 from interacting with Phe-343 to stabilize the closed pore structure mediated through a π-π interaction. This hypothesis awaits further experimental validation.

Discussion

RTG, an anticonvulsant drug currently prescribed for the treatment of epilepsy, has been shown to prolong the open conformation of neuronal Kv7.2/3 channels (13–15) and its effect demonstrated to depend on the presence of Trp-265 in Kv7.3 (20) and/or Trp-236 in Kv7.2 (21). However, the mechanism by which RTG produces its effect has not yet been outlined at the molecular level. Here we show that RTG increases the open probability of the Kv7.2 PM, Kv.7.3 PM, and Kv7.2/7.3 heteromeric PMs in the absence of the voltage sensor module, suggesting that its sufficient target site resides exclusively on the PM. But how does an interaction between RTG and the pore module subunits of Kv7.3 or Kv7.2 produce this effect? Homology modeling of the closed structure of Kv7.3, using as a template the only available closed structure of a Kv channel with significant homology to Kv7.3 (22), allows us to propose a mechanism. In the modeled closed conformation of Kv7.3, we identify a π-π interaction between Trp-265 and Phe-343 within the same subunit. We propose that destabilizing such π-π interaction either by mutations or by RTG favors the open channel conformation. These findings outline a new path forward to design and test drugs that modulate the function of Kv7 channels and the ensued signaling networks.

Author Contributions

R. S. synthesized and purified proteins and performed all current measurements. J. S. S. designed all clones, developed the protocol for synthesis and purification of proteins, including execution of these, and performed all modeling and docking experiments. M. M. conceived and designed the strategy. All authors designed the study, analyzed the results, wrote the paper, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-49711 (to M. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- Kv7

- voltage-gated K+ channel family 7

- RTG

- Retigabine

- PM

- pore module

- Po

- open probability.

References

- 1.Jentsch T. J. (2000) Neuronal KCNQ potassium channels: physiology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soldovieri M. V., Miceli F., and Taglialatela M. (2011) Driving with no brakes: molecular pathophysiology of Kv7 potassium channels. Physiology 26, 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maljevic S., Wuttke T. V., Seebohm G., and Lerche H. (2010) KV7 channelopathies. Pflügers Arch. 460, 277–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown D. A., and Adams P. R. (1980) Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neuron. Nature 283, 673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrion N. V. (1997) Control of M-current. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59, 483–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selyanko A. A., Hadley J. K., Wood I. C., Abogadie F. C., Jentsch T. J., and Brown D. A. (2000) Inhibition of KCNQ1–4 potassium channels expressed in mammalian cells via M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Physiol. 522, 349–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro M. S., Roche J. P., Kaftan E. J., Cruzblanca H., Mackie K., and Hille B. (2000) Reconstitution of muscarinic modulation of the KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K+ channels that underlie the neuronal M current. J. Neurosci. 20, 1710–1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh N. A., Charlier C., Stauffer D., DuPont B. R., Leach R. J., Melis R., Ronen G. M., Bjerre I., Quattlebaum T., Murphy J. V., McHarg M. L., Gagnon D., Rosales T. O., Peiffer A., Anderson V. E., and Leppert M. (1998) A novel potassium channel gene, KCNQ2, is mutated in an inherited epilepsy of newborns. Nat. Genet. 18, 25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biervert C., Schroeder B. C., Kubisch C., Berkovic S. F., Propping P., Jentsch T. J., and Steinlein O. K. (1998) A potassium channel mutation in neonatal human epilepsy. Science 279, 403–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerche H., Biervert C., Alekov A. K., Schleithoff L., Lindner M., Klinger W., Bretschneider F., Mitrovic N., Jurkat-Rott K., Bode H., Lehmann-Horn F., and Steinlein O. K. (1999) A reduced K+ current due to a novel mutation in KCNQ2 causes neonatal convulsions. Ann. Neurol. 46, 305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroeder B. C., Kubisch C., Stein V., and Jentsch T. J. (1998) Moderate loss of function of cyclic-AMP-modulated KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K+ channels causes epilepsy. Nature 396, 687–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlier C., Singh N. A., Ryan S. G., Lewis T. B., Reus B. E., Leach R. J., and Leppert M. (1998) A pore mutation in a novel KQT-like potassium channel gene in an idiopathic epilepsy family. Nat. Genet. 18, 53–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Main M. J., Cryan J. E., Dupere J. R., Cox B., Clare J. J., and Burbidge S. A. (2000) Modulation of KCNQ2/3 potassium channels by the novel anticonvulsant retigabine. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wickenden A. D., Yu W., Zou A., Jegla T., and Wagoner P. K. (2000) Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 58, 591–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatulian L., Delmas P., Abogadie F. C., and Brown D. A (2001) Activation of expressed KCNQ potassium currents and native neuronal M-type potassium currents by the anti-convulsant drug retigabine. J. Neurosci. 21, 5535–5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armand V., Rundfeldt C., and Heinemann U. (1999) Effects of retigabine (D-23129) on different patterns of epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in rat entorhinal cortex hippocampal slices. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 359, 33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orhan G., Wuttke T. V., Nies A. T., Schwab M., and Lerche H. (2012) Retigabine/ezogabine, a KCNQ/Kv7 channel opener: pharmacological and clinical data. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 13, 1807–1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter R. J., Nohria V., and Rundfeldt C. (2007) Retigabine. Neurotherapeutics 4, 149–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunthorpe M. J., Large C. H., and Sankar R. (2012) The mechanism of action of retigabine (ezogabine), a first-in-class K+ channel opener for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia 53, 412–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenzer A., Friedrich T., Pusch M., Saftig P., Jentsch T. J., Grötzinger J., and Schwake M. (2005) Molecular determinants of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channel sensitivity to the anticonvulsant retigabine. J. Neurosci. 25, 5051–5060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wuttke T. V., Seebohm G., Bail S., Maljevic S., and Lerche H. (2005) The new anticonvulsant retigabine favors voltage-dependent opening of the Kv7. 2 (KCNQ2) channel by binding to its activation gate. Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 1009–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos J. S., Asmar-Rovira G. A., Han G. W., Liu W., Syeda R., Cherezov V., Baker K. A., Stevens R. C., and Montal M. (2012) Crystal structure of a voltage-gated K+ channel pore module in a closed state in lipid membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 43063–43070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syeda R., Santos J. S., Montal M., and Bayley H. (2012) Tetrameric assembly of KvLm K+ channels with defined numbers of voltage sensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16917–16922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos J. S., Grigoriev S. M., and Montal M. (2008) Molecular template for a voltage sensor in a novel K+ channel: III: functional reconstitution of a sensorless pore module from a prokaryotic Kv channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 132, 651–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H. S., Pan Z., Shi W., Brown B. S., Wymore R. S., Cohen I. S., Dixon J. E., and McKinnon D. (1998) KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science 282, 1890–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang W.-P., Levesque P. C., Little W. A., Conder M. L., Ramakrishnan P., Neubauer M. G., and Blanar M. A. (1998) Functional expression of two KvLQT1-related potassium channels responsible for an inherited idiopathic epilepsy. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 19419–19423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selyanko A. A., Hadley J. K., and Brown D. A. (2001) Properties of single M-type KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channels expressed in mammalian cells. J. Physiol. 534, 15–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamas J. A., Selyanko A. A., and Brown D. A (1997) Effects of a cognition-enhancer, linopirdine (DuP 996), on M-type potassium currents (IK(M)) and some other voltage- and ligand-gated membrane currents in rat sympathetic neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 605–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheley S., Malghani M. S., Song L., Hobaugh M., Gouaux J. E., Yang J., and Bayley H. (1997) Spontaneous oligomerization of a staphylococcal α-hemolysin conformationally constrained by removal of residues that form the transmembrane beta-barrel. Protein Eng. 10, 1433–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos J. S., Syeda R., and Montal M. (2013) Stabilization of the conductive conformation of a Kv channel: the lid mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 16619–16628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syeda R., Santos J. S., and Montal M. (2014) Lipid bilayer modules as determinants of K+ channel gating. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 4233–4243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coste B., Xiao B., Santos J. S., Syeda R., Grandl J., Spencer K. S., Kim S. E., Schmidt M., Mathur J., Dubin A. E., Montal M., and Patapoutian A. (2012) Piezo proteins are pore-forming subunits of mechanically activated channels. Nature 483, 176–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trott O., and Olson A. J. (2010) AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., Gamper N., and Shapiro M. S. (2004) Single-channel analysis of KCNQ K+ channels reveals the mechanism of augmentation by a cysteine-modifying reagent. J. Neurosci. 24, 5079–5090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punke M. A., and Friederich P. (2007) Amitriptyline is a potent blocker of human Kv1.1 and Kv7.2/7.3 channels. Anesth. Analg. 104, 1256–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatulian L., and Brown D. A. (2003) Effect of the KCNQ potassium channel opener retigabine on single KCNQ2/3 channels expressed in CHO cells. J. Physiol. 549, 57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long S. B., Tao X., Campbell E. B., and MacKinnon R. (2007) Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature 450, 376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange W., Geissendörfer J., Schenzer A., Grötzinger J., Seebohm G., Friedrich T., and Schwake M. (2009) Refinement of the binding site and mode of action of the anticonvulsant Retigabine on KCNQ K+ channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 272–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]