Abstract

It is of great concern worldwide that active nitrogenous gases in the global nitrogen cycle contribute to regional and global-scale environmental issues. Nitrous oxide (N2O) and nitric oxide (NO) are generally interrelated in soil nitrogen biogeochemical cycles, while few studies have simultaneously examined these two gases emission from typical croplands. Field experiments were conducted to measure N2O and NO fluxes in response to chemical N fertilizer application in annual greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in southeast China. Annual N2O and NO fluxes averaged 52.05 and 14.87 μg N m−2 h−1 for the controls without N fertilizer inputs, respectively. Both N2O and NO emissions linearly increased with N fertilizer application. The emission factors of N fertilizer for N2O and NO were estimated to be 1.43% and 1.15%, with an annual background emission of 5.07 kg N2O-N ha−1 and 1.58 kg NO-N ha−1, respectively. The NO-N/N2O-N ratio was significantly affected by cropping type and fertilizer application, and NO would exceed N2O emissions when soil moisture is below 54% WFPS. Overall, local conventional input rate of chemical N fertilizer could be partially reduced to attain high yield of vegetable and low N2O and NO emissions in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China.

It is of great concern worldwide that active nitrogenous gases in the global nitrogen cycle contribute to regional and global-scale environmental issues1. Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important long-lived greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming. Both N2O and nitric oxide (NO) play major roles in atmospheric chemistry processes, in which they are involved in the destruction of stratospheric ozone2,3,4. Agricultural activities are responsible for about 60% and 10% of global anthropogenic N2O and NO sources, respectively, largely due to fertilizer application increased in croplands5. The estimates of N2O and NO emissions from croplands have large uncertainties since the sources and sinks of N2O and NO are not well characterized in different agroecosystems (e.g. rice paddies, grain upland croplands, vegetable cropping systems)6,7,8. In addition, N2O and NO are generally interrelated in soil nitrogen biogeochemical cycles, and thus it is important to simultaneously examine these two gases emission from typical croplands9.

In recent years, vegetable production has become economically important in China, with its harvest area accounting for 45% of the world total10. Meanwhile, greenhouse vegetable cultivation has increased rapidly since 2000 and has reached to more than 3.44 million hectares in 201011,12, accounting for 18.1% and 2.1% of the total vegetable and agricultural area, respectively13. It is common that excessive N fertilizer and frequent irrigation are adopted to maintain high yield in greenhouse vegetable fields by the local farmers in China. For example, annual N fertilization application rates are mostly around 1000–1500 kg N ha−1 in the greenhouse vegetable systems14,15, and even more than 2800 kg N ha−1 in some areas of China16,17. Indeed, excessive N fertilizer application with low N use efficiency in intensively vegetable fields in China has been of great concern with respect to agricultural and environmental issues18,19.

Vegetable cropping system has been recognized to be an important source of N2O and NO emissions9,11,20,21. Although greenhouse vegetable production typically constitutes multiple vegetable cropping rotations within a year, most field N2O and NO measurements were taken only within a certain individual vegetable cropping season, which limited insights into annual N2O and NO budgets due to their high inter-seasonal variations10,22,23. Therefore, field measurements of N2O and NO fluxes taken over a whole annual cycle would be particularly important to gain an insight into annual direct N2O and NO emissions from Chinese vegetable cropping systems19,23.

High N application can stimulate nitrification and/or denitrification processes and thus promote N2O and NO emissions from croplands9,20,24. In general, there is a strong increase of both N2O and NO emissions accompanying with N application rates in croplands2,25. Hoben et al.26 found a nonlinear exponentially increasing N2O response to N application rates from a corn-soybean rotation, while N2O emissions were not significantly reduced with decreasing nitrogen fertilizer application in a winter wheat-summer maize rotation cropland by Yan et al.27. Relatively, there were few studies have measured N2O and NO emission fluxes simultaneously from Chinese vegetable cropping systems, especially in the greenhouse vegetable cultivations9,23. It remains unclear whether local conventional input rate of chemical N fertilizer could be reduced to simultaneously attain high yield of vegetable and low N2O and NO emissions in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China.

We conducted an in situ field measurement of annual N2O and NO emissions from greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in southeast China. We examined which factors were important to N2O and NO emissions in terms of NO/N2O ratio or N2O plus NO emissions. The main objectives of this study are to quantify seasonal and annual N2O and NO emissions in response to chemical N fertilizer application in annual greenhouse vegetable cropping systems. Eventually, this study also attempted to optimize N fertilizer rate for the simultaneous achievements of low N2O and NO emissions and high yields in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China.

Results

N2O fluxes

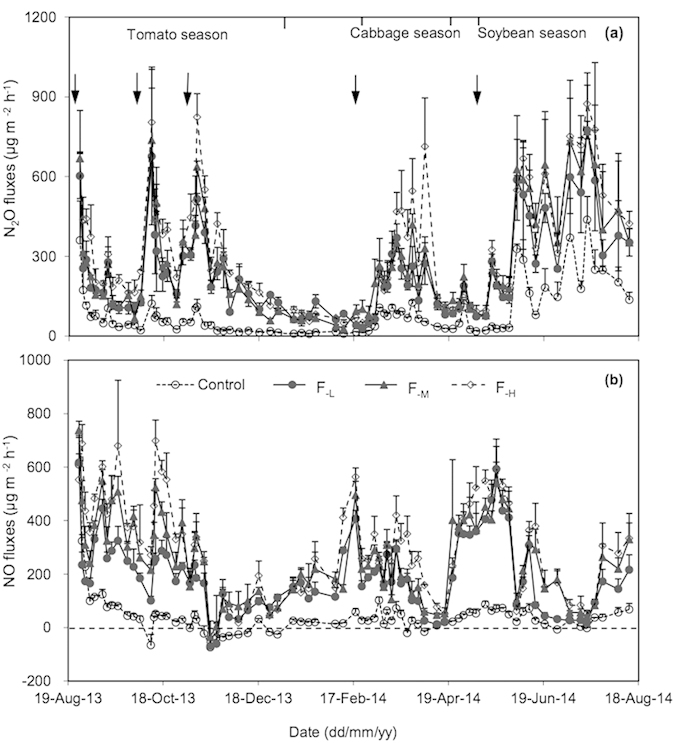

Seasonal dynamics of N2O fluxes showed similar pattern among the fertilizer treatments (Fig. 1a). In general, N2O fluxes followed a sporadic and pulse-like pattern over the whole annual cycle. Substantial N2O emissions occurred during the vegetable-growing seasons, while N2O fluxes were relatively lower during the inter-cropping fallow periods. The intensive N2O flux peaks were mainly observed within one week following basal fertilization and topdressing events accompanied with irrigation (Fig. 1a). Although chemical N fertilizer application did not significantly alter the seasonal pattern of N2O fluxes, it greatly increased the magnitude of N2O fluxes.

Figure 1.

Seasonal dynamics of N2O (a) and NO (b) fluxes from greenhouse vegetable cropping systems over the 2013–2014 annual cycle. Arrows represent basal fertilization and topdressing events. The bars indicate the standard errors of mean (n = 3). F−L, F−M and F−H refer to N fertilizer treatments at the low, medium and high application rates, respectively.

An ANOVA indicated that the N2O emissions were significantly affected by cropping type and fertilizer application, while their interactions were not pronounced (Tables 1 and 2). Among the three vegetable cropping seasons, seasonal mean N2O fluxes showed the highest for green soybean, while they were relatively comparable between the tomato and Chinese cabbage cropping seasons. For the controls without fertilizer application, N2O fluxes averaged 23.90, 39.74 and 115.22 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 during the tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean growing seasons, respectively (Table 1). For the plots with local conventional input level of N fertilizer (F−M), seasonal N2O fluxes averaged 288.69 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 during green soybean season, which were 153% and 115% greater than those during tomato and Chinese cabbage seasons, respectively. Over the whole annual cycle, N2O emissions totaled 12.45–16.47 kg N2O-N ha−1 for the fertilizer treatments, of which, about 37–40%, 14–16% and 44–48% were released during the tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean seasons, respectively.

Table 1. Seasonal and annual total (Mean ± 1SE, n = 3) of N2O and NO emissions and vegetable yield (fresh weight) in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems.

| Measurement period | Treatment | N fertilizer | N2O-N | NO-N | NO-N/N2O-N ratio | Yield (t ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg N ha−1) | ||||||

| Tomato (24 Aug 2013~3 Mar 2014, 190 days) | Control | 0 | 1.09 ± 0.17d | 0.63 ± 0.09fgh | 0.61 ± 0.14abcd | 112.40 ± 5.38a |

| F−L | 260 | 4.97 ± 0.32abc | 3.69 ± 0.28b | 0.74 ± 0.04abc | 120.67 ± 5.46a | |

| F−M | 400 | 5.20 ± 0.34abc | 5.08 ± 0.40a | 0.98 ± 0.17a | 123.07 ± 5.73a | |

| F−H | 520 | 6.60 ± 0.48a | 5.95 ± 0.26a | 0.91 ± 0.08ab | 122.40 ± 9.83a | |

| Chinese cabbage (4 Mar~7 May 2014, 65 days) | Control | 0 | 0.62 ± 0.02d | 0.21 ± 0.12h | 0.33 ± 0.03cd | 71.41 ± 8.57b |

| F−L | 100 | 1.78 ± 0.23cd | 1.25 ± 0.43efgh | 0.72 ± 0.11abc | 79.84 ± 6.50b | |

| F−M | 150 | 2.09 ± 0.26cd | 1.55 ± 0.71defg | 0.76 ± 0.16abc | 73.17 ± 4.52b | |

| F−H | 200 | 2.70 ± 0.48bcd | 1.89 ± 0.34cdef | 0.73 ± 0.07abc | 69.16 ± 4.72b | |

| Green soybean (8 May~13 Aug 2014, 98 days) | Control | 0 | 2.71 ± 0.26bcd | 0.42 ± 0.16gh | 0.16 ± 0.02d | 8.39 ± 1.07c |

| F−L | 60 | 5.71 ± 0.72ab | 2.00 ± 0.57cde | 0.38 ± 0.10cd | 10.25 ± 1.36c | |

| F−M | 90 | 6.79 ± 0.82a | 2.62 ± 0.91bcd | 0.43 ± 0.09bcd | 9.26 ± 0.92c | |

| F−H | 120 | 7.17 ± 1.08a | 2.97 ± 0.61bc | 0.43 ± 0.05bcd | 9.94 ± 0.57c | |

| Annual cycle (24 Aug 2013~13 Aug 2014, 353 days) | Control | 0 | 4.41 ± 0.45 | 1.26 ± 0.37 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 192.20 ± 15.01 |

| F−L | 420 | 12.45 ± 1.27 | 6.94 ± 1.28 | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 210.76 ± 13.31 | |

| F−M | 640 | 14.07 ± 1.42 | 9.25 ± 2.02 | 0.69 ± 0.14 | 205.50 ± 11.17 | |

| F−H | 840 | 16.47 ± 2.04 | 10.81 ± 1.21 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 201.51 ± 15.13 | |

Data shown are means ± standard errors of three replicates. The flux measurements period includes the vegetable-growing season and the following fallow period. Different letters within the same column indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 level.

Table 2. A two-way ANOVA for seasonal N2O and NO emissions, NO-N/N2O-N ratio and yield as affected by cropping type and N fertilizer application in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems.

| Factors | df |

N2O-N |

NO-N |

NO-N/N2O-N ratio |

Yield |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | F-ratio | P-value | SS | F-ratio | P-value | SS | F-ratio | P-value | SS | F-ratio | P-value | ||

| Cropping type (C) | 2 | 91.30 | 32.8 | <0.001 | 43.14 | 114.9 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 22.2 | <0.001 | 73458 | 418.4 | <0.001 |

| Fertilizer (F) | 3 | 81.91 | 19.6 | <0.001 | 52.51 | 93.2 | <0.001 | 0.71 | 7.9 | <0.001 | 184.08 | 0.7 | 0.56 |

| C × F | 6 | 11.98 | 1.4 | 0.24 | 12.53 | 11.1 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 0.84 | 230.41 | 0.4 | 0.85 |

| Model | 11 | 185.18 | 12.1 | <0.001 | 108.18 | 52.4 | <0.001 | 2.12 | 6.4 | <0.001 | 73872 | 76.5 | <0.001 |

| Error | 24 | 33.42 | 4.51 | 0.72 | 2107 | ||||||||

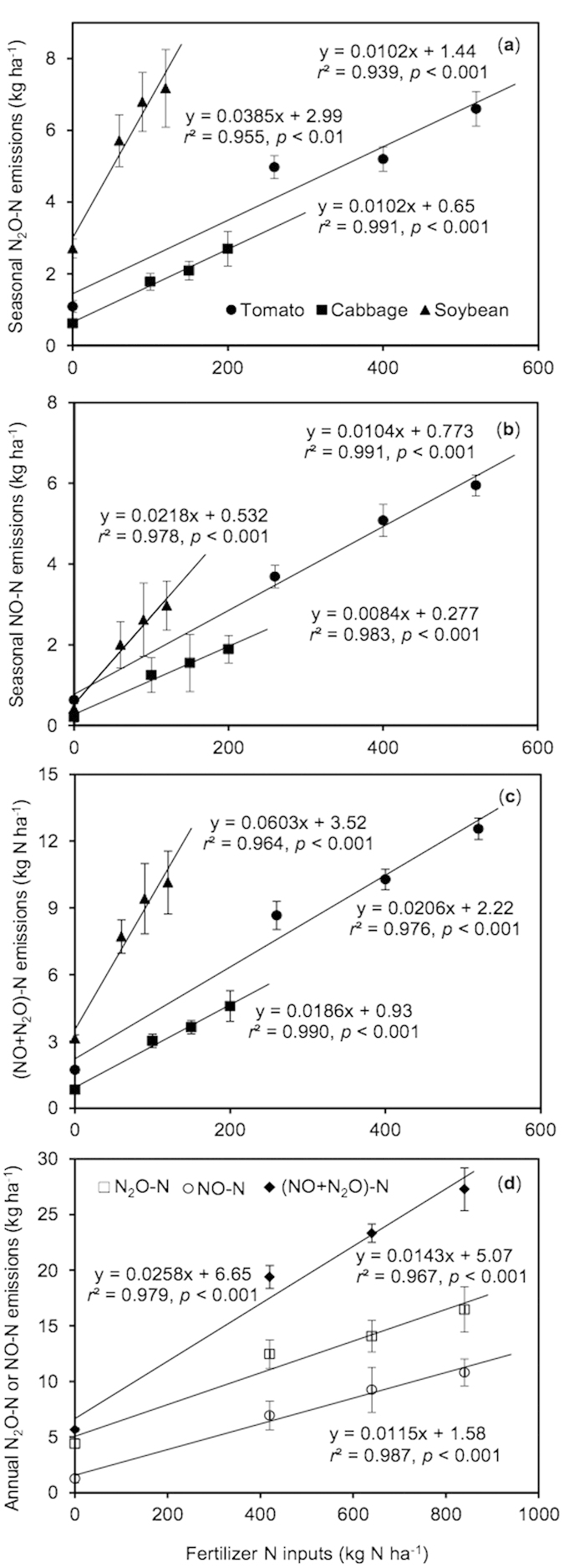

Chemical N fertilizer application significantly and consistently increased N2O emissions during the three cropping seasons (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 2). The strongest response of N2O fluxes to N fertilizer input was found in green soybean, while the response of N2O fluxes to N fertilizer input did not significantly differ between tomato and Chinese cabbage crops (Fig. 2). The parameters in the simulated OLS regressions predicted N fertilizer-induced emission factor of N2O to be 1.02% for tomato and Chinese cabbage, and 3.85% for green soybean (Table 1, Fig. 2a). Over the whole annual cycle, the emission factor of N fertilizer for N2O was estimated to be 1.43% in the greenhouse tomato-Chinese cabbage-green soybean cropping systems (Fig. 2c). The seasonal background emissions of N2O were estimated to be 0.65, 1.44 and 2.99 kg N2O-N ha−1 for tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean, respectively, and thus an annual background emission of N2O amounted to as high as 5.07 kg N2O-N ha−1 (Fig. 2a,c).

Figure 2.

Dependence of seasonal N2O (a) and NO (b) emissions, and annual N2O/NO (c) emissions on N fertilizer inputs in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems.

NO fluxes

Similar to N2O, seasonal pattern of NO fluxes did not significantly differ among the fertilizer treatments (Fig. 1b). Except the controls without fertilizer application, NO fluxes from the N fertilizer treatments showed a sporadic and pulse-like pattern over the whole annual cycle. Besides substantial NO emissions incurred by N fertilizer application during the vegetable-growing seasons, some NO fluxes were also pronounced during the fallow periods prior to Chinese cabbage and green soybean cropping seasons. Over the whole annual cycle, some peaks of NO flux appeared earlier than those of N2O (Fig. 1b).

Seasonal mean NO fluxes did not significantly differ among the three vegetable cropping seasons, although seasonal total NO emissions were significantly affected by cropping type (Tables 1 and 2). For the controls without fertilizer application, NO fluxes averaged 13.82, 13.46 and 17.86 μg NO-N m−2 h−1 during the tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean growing seasons, respectively (Table 1). Seasonal NO fluxes averaged 80.92–85.03 μg NO-N m−2 h−1, 99.36–111.40 μg NO-N m−2 h−1, and 121.15–130.48 μg NO-N m−2 h−1 for the F−L, F−M and F−H treatments, respectively. Over the whole annual cycle, NO emissions totaled 1.26 kg NO-N ha−1 for the controls, and 6.94–10.81 kg NO-N ha−1 for the fertilizer treatments. The tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean contributed 50–55%, 17–18% and 27–33% to the annual total NO-N emissions, respectively.

Seasonal total NO emissions were consistently increased with chemical N fertilizer application for the three crops, while the response of NO fluxes to N fertilizer input was stronger in green soybean, relative to tomato and Chinese cabbage cropping seasons (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 2). On average, the emission factor of NO was estimated to be 1.04% for tomato, 0.84% for Chinese cabbage, and 2.18% for green soybean, respectively (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the annual EF of NO was estimated to be 1.15% in the greenhouse tomato-Chinese cabbage-green soybean cropping systems (Fig. 2c). Over the whole annual cycle, the background NO emission totaled 1.58 kg NO-N ha−1 in the greenhouse vegetable cropping systems. Of which, the tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean cropping seasons were responsible for 49%, 18% and 33%, respectively (Fig. 2b,d).

NO-N/N2O-N ratio

The ratio of NO-N/N2O-N was significantly affected by cropping type and fertilizer application, but it was independent of their interaction (Tables 1 and 2). The ratios of NO-N/N2O-N were lowest for green soybean, and highest for tomato among the three cropping seasons. For the controls without fertilizer application, the NO-N/N2O-N ratio averaged 0.61, 0.33 and 0.16 during the tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean growing seasons, respectively (Table 1). Chemical N fertilizer application consistently increased the NO-N/N2O-N ratios cross the three cropping seasons (Fig. 2d). Relative to the controls, chemical N fertilizer application increased the NO-N/N2O-N ratios by 21–68%, 118–130% and 145–175% during the tomato, Chinese cabbage, and green soybean seasons, respectively. Over the whole annual cycle, the NO-N/N2O-N ratios averaged 0.28 for the controls, and 0.57–0.69 for the N fertilizer treatments.

Vegetable yield

Vegetable yield (fresh weight) significantly differed among the tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean crops, while it was not significantly affected by fertilizer application and the interactions between cropping type and fertilizer input (Tables 1 and 2). Among the fruit-, leaf- and legume-vegetable types, tomato had the highest yield while the yield was the lowest for green soybean. Although chemical N fertilizer slightly increased vegetable yield, this effect was not statistically significant. In particular, no significant difference in vegetable yield among the treatments with different input rates of chemical N fertilizer. Over the whole annual cycle, the highest yield was found for the F−L plots with low input rate of N fertilizer.

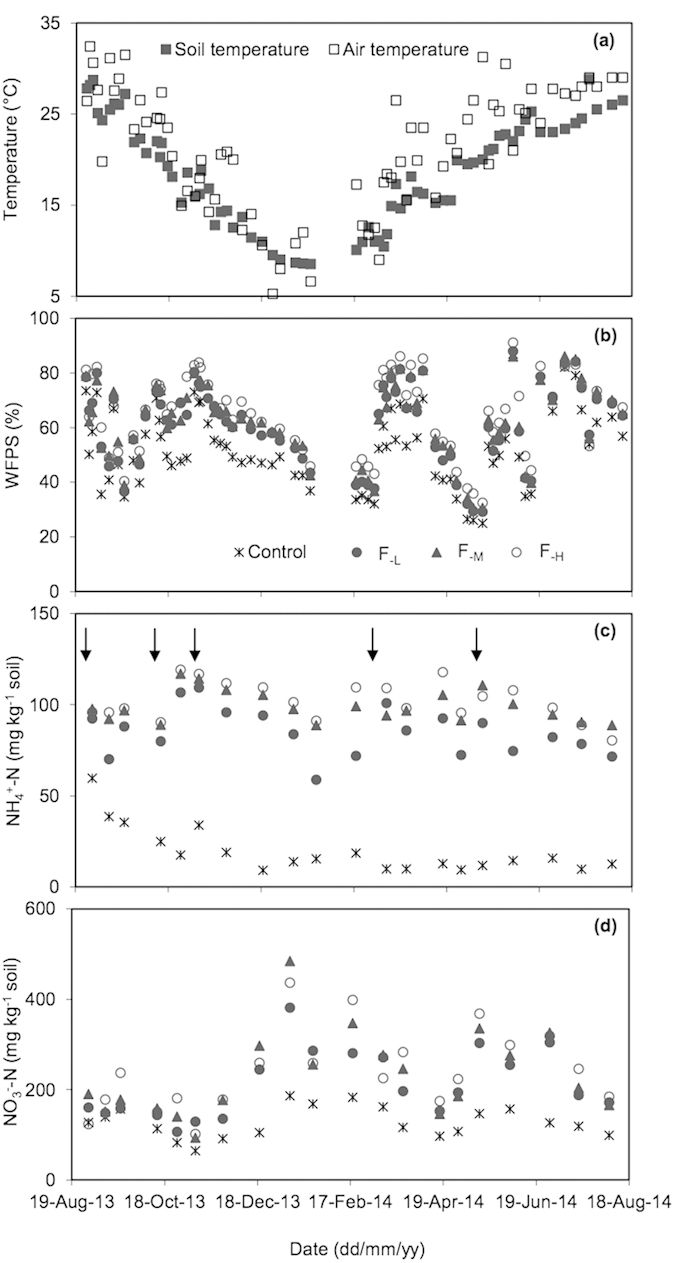

Correlation of N2O and NO with soil properties

Over the whole annual cycle, air temperature was slightly higher than soil temperature in the greenhouse except in the winter season through late December to February (Fig. 3a). Both air temperature and soil temperature showed similar seasonal variation pattern, with the highest in summer season and the lowest in winter season. Annual air temperature and soil temperature averaged 21.4 °C and 18.7 °C, respectively. Soil moisture in different treatments showed similar variation pattern over the whole annual cycle, ranging from 24.9% to 91.1% of WFPS (Fig. 3b). In general, soil mineral N contents were increased following fertilization and irrigation events (Fig. 3c,d). For the control plots, soil mineral N contents varied smoothly and were significantly lower than those of the N fertilization plots.

Figure 3.

Seasonal dynamics of soil and air temperature (a), soil moisture (WFPS, b), and soil ammonium (NH4+-N, c) and nitrate (NO3−-N, d) in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems over the 2013–2014 annual cycle. Arrows represent basal fertilization and topdressing events. F−L, F−M and F−H refer to N fertilizer treatments at the low, medium and high application rates, respectively.

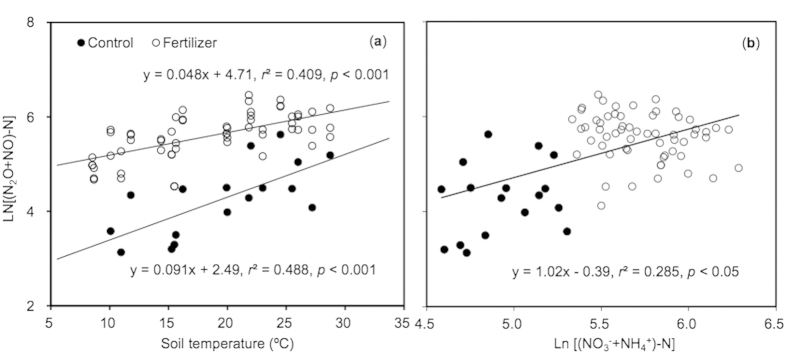

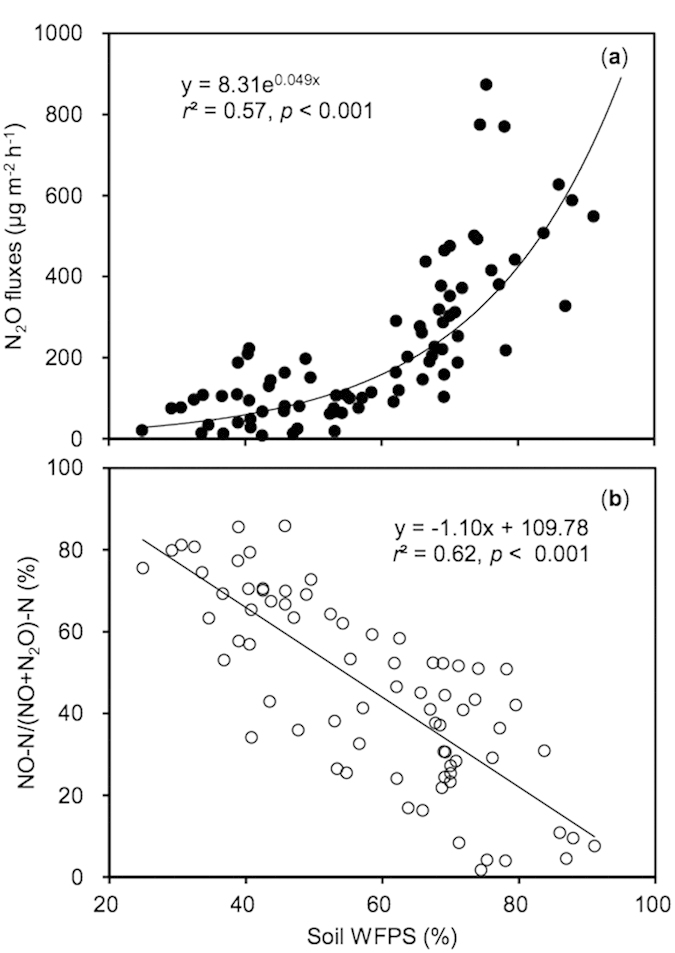

The N2O-N plus NO-N emissions were significantly correlated with soil temperature for the controls and N fertilizer treatments (Fig. 4a). However, the slope of simulated regression was significantly lower for the controls than for the N fertilizer treatments, suggesting chemical N fertilizer application had weakened the response of N2O-N plus NO-N emissions to soil temperature (Fig. 4a). The N2O-N plus NO-N emissions depended significantly on soil mineral N contents across the treatments (Fig. 4b). Over the whole annual cycle, N2O fluxes depended greatly on soil moisture (Fig. 5a). Although NO fluxes were not significantly related to soil moisture over the whole annual cycle, the ratio of NO-N/(NO-N+N2O-N) was linearly correlated with soil moisture (Fig. 5b).

Figure 4.

The sum of N2O-N and NO-N fluxes dependent on soil WFPS (a) and soil mineral N (NH4+-N+NO3−-N, b) contents in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems. Both sum of N2O-N and NO-N fluxes and soil mineral N contents were log-transformed.

Figure 5.

Correlation of soil N2O fluxes (a) and the ratio of NO-N/(NO+N2O)-N (b) with soil WFPS in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems.

Discussion

To meet the increasing demand of vegetable products in China, greenhouse vegetable cropping systems have been greatly developed in recent decades. Recently, an increasing number studies have focused on N2O and NO emissions from Chinese greenhouse vegetables. Consistent with previous studies9,21,22,23,24, the intensive N2O and NO flux peaks generally occurred following fertilizer application accompanied with irrigation during the vegetable-growing seasons. In addition, some peaks of NO flux appeared during the inter-cropping fallow seasons, earlier than the appearance of N2O flux peaks, which was primarily due to lower soil moisture suitable for NO emissions.

It is well documented that N2O emissions depended significantly on vegetable crop types, which often leads to large inter-seasonal variations in annual greenhouse vegetable cropping systems9,23,28. In the present study, consecutive cultivation of tomato, Chinese cabbage and green soybean constitutes a typical annual fruit-leaf-legume vegetables rotation in greenhouse cropping systems in China. Among the three vegetable cropping seasons, N2O emissions showed the highest for green soybean in terms of seasonal mean fluxes or seasonal amount. A similar result was also obtained in an annual greenhouse green soybean-pepper-broccoli vegetables rotation system in China, showing that green soybean contributed the most to the annual total of N2O emissions, while NO emissions were comparable between green soybean and broccoli cropping seasons9. Indeed, green soybean roots can fix atmospheric N2, which can be further transformed into N source for nitrifier and denitrifier to produce N2O, and soybean plant itself can also emit large amounts of N2O29. Higher N2O emissions during green soybean seasons relative to tomato and Chinese cabbage seasons might also due to stronger response of N2O emissions to N fertilizer application in green soybean than in other vegetable crops (Fig. 2a).

Although N2O emissions showed high inter-seasonal variations, annual total of N2O emissions in this study was generally comparable to previous results in the greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China. In the present study, For the N fertilizer treatment, mean annual N2O emissions ranged from 12.45 to 16.47 kg N2O-N ha−1, falling within the range of those (4.20–16.50 kg N2O-N ha−1) reported in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China9,15,19,21,24,30,31. The mean fluxes of NO did not show significant inter-seasonal variations, although seasonal total emissions of NO differed among the three cropping types. Over the whole annual cycle, mean NO emissions from N fertilizer treatments ranged from 6.94 to 10.81 kg NO-N ha−1, highly close to the most previous estimates in annual vegetable cropping systems in China32,33. However, our measurements were greater than those estimates obtained by Yao et al.9, showing annual NO emissions equivalent to be 3.1 kg NO-N ha−1 in an annual greenhouse vegetable cropping system in the present study area. The difference in annual NO emissions between the two studies could be associated with divergence in soil pH in these two studies (5.5 vs. 8.0). Some studies showed that high soil pH can inhibit NO production during nitrification, and high NO fluxes were frequently observed in soils with low pH34,35. In addition, a previous measurement taken in the present study area showed that annual NO emissions were as high as 47.1 kg NO-N ha−1 in the vegetable fields under farmer’s conventional fertilizer practice35, which is remarkably greater than the measurements of this study and some other previous estimates in Chinese vegetable cropping systems.

In the present study, the emission factor of N2O was estimated to be 1.43% in annual greenhouse tomato-Chinese cabbage-green soybean cropping systems, comparable to the estimate of 1.10% in an annual green soybean-pepper-broccoli cropping system9, but greater than the other recent reports23,24,31,36. Based on one year field study in southeast China, the annual N2O emission factor was estimated to be 0.38% in the greenhouse tomato-cucumber-celery rotation systems31, or 0.36% in the greenhouse red pepper-chrysanthemum vegetable rotation systems21. He et al.24 estimated the emission factor of N2O to be 0.27–0.30% in an intensively managed greenhouse tomato cropping system in Northern China. Greater emission factors of N2O in this study and Yao et al.’s9 study than in the other recent vegetable studies was largely attributed to green soybean cropping seasons in greenhouse vegetable systems. Nevertheless, the emission factor of N2O in this greenhouse vegetable cropping system was comparable to the earlier estimate of 1.05–1.35% in Chinese upland staple grain crops37,38,39.

Relatively, few studies have estimated emission factor of N fertilizer for NO in croplands. The emission factor of NO averaged 1.15% over the whole annual vegetation rotation cycle in this study, falling within the range of 0.02–3.60% for NO emission factors observed in the vegetable fields worldwide32. Li and Wang33 estimated the emission factor of NO to be 2.4% in an annual Chinese cabbage cropping field in the Pearl River Delta, China, greater than the estimates of this study. However, our estimated values were significantly greater than the reported value of 0.05% in annual rice-wheat cropping rotation systems40, or 0.36% in annual greenhouse green soybean-pepper-broccoli cropping systems in the present study region. Yan et al.39 estimated the average emission factor of NO to be 0.71% for global upland grain croplands, which is slightly lower than our estimates in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems. By taking N2O and NO emissions into account together, the emission factor of N fertilizer was estimated to be 2.58% in annual greenhouse vegetable cropping systems (Fig. 3c). Nevertheless, more field measurements are highly needed in typical cropping systems given that the emission factors of N2O and NO are documented to be associated with environmental factors, soil properties and agricultural practices9,22,31,32.

A great many studies have documented high background emission of N2O in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China. In the simulated linear regression of N2O emissions with N fertilizer application rates (Fig. 2a,c), the background emission of N2O was, on average, estimated to be 5.07 kg N2O-N ha−1 over the whole annual cycle. The estimate of annual N2O background emissions in this study was highly close to some previous measurements taken in the present study area. Annual background emissions of N2O were estimated to be 3.40, 5.0, and 5.65 kg N2O-N ha−1 in the greenhouse vegetable fields with annual cropping rotations of tomato-cucumber-celery, green soybean-pepper-broccoli and red pepper-chrysanthemum, respectively9,21,31. In contrast, annual background emissions of NO averaged 1.58 kg NO-N ha−1 in this study, greater than previous estimates of 0.16–0.40 kg NO-N ha−1 by Mei et al.32, 0.41 kg NO-N ha−1 by Deng et al.35 or 0.41 kg NO-N ha−1 by Yao et al.9 in vegetable cropping systems in this region.

Although relatively few studies have focused on annual background emissions of N2O and NO in the typical greenhouse vegetable fields, several available studies suggested that background emissions of N2O and NO in greenhouse vegetable fields were generally greater than those in grain staple croplands in China9,21,24,31. Background N2O emissions were estimated, on average, to be 1.22–1.87 kg N2O-N ha−1 yr−1 in Chinese grain croplands39,41,42,43. Greater background N2O and NO emissions from greenhouse vegetable fields relative to grain staple croplands might be associated with frequent irrigation coupled with residual N from heavy fertilizer inputs for several years, and/or run-off from adjacent heavily fertilized plots. Nevertheless, available studies suggest that background N2O and NO emissions from greenhouse vegetable cropping systems could play particularly important roles in developing a national inventory of N2O and NO emissions from vegetable fields in China.

In general, N2O and NO are primarily produced during soil nitrification and denitrification processes2,44, which are highly associated with soil properties in agricultural fields2,23,27,45. Consistent with previous studies9, the N2O-N plus NO-N emissions depended on soil mineral nitrogen availability and temperature in this study (Fig. 4). Moreover, the response of N2O-N plus NO-N emissions to soil temperature was stronger in the control than in N fertilizer application treatments. A similar result showed that fertilizer application increased the response of N2O-N plus NO-N emissions to soil mineral N availability, but decreased their response to temperature in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems9. This suggests that N2O-N plus NO-N emissions were primarily limited by soil mineral N availability.

Soil moisture was lower in the control than fertilizer treatments during the tomato and Chinese cabbage cropping seasons, but there were no obvious differences in soil moisture among all treatments during the green soybean season (Fig. 3b). Relative to green soybean, tomato and Chinese cabbage require more water resource, and thereby tomato and Chinese cabbage crops would uptake more water from soils under fertilizer application. In contrast to previous studies9, the dependence of N2O-N plus NO-N emissions on soil WFPS was not significant in this study. Instead, N2O fluxes were positively related to soil WFPS, while the ratio of NO/(NO + N2O) was negatively correlated to soil WFPS over the whole annual vegetable cropping cycles (Fig. 5). The emission ratio of NO/N2O or NO/(NO+N2O) has been frequently used as an indicator of the relative importance of nitrification and denitrification in producing NO and N2O46,47,48. The simulated regression projected that NO would exceed N2O emissions when soil WFPS was lower than 54% in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems, highly in agreement with the results obtained in aggrading forests49.

Excessive chemical N fertilizer application in vegetable fields in China has been frequently pointed out, which would incur substantial N2O and NO emissions. Among the N fertilizer treatments, the F−L treatments with low N fertilizer input rate showed the highest yield and lowest N2O and NO emissions, suggesting that local conventional input rate of chemical N fertilizer could be reduced by one-third to attain high yield of vegetable and reduce N2O and NO emissions in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China. With the rapid development of greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China, nevertheless, it is urgent to establish fertilizer management optimization strategies specific to greenhouse vegetables production so as to simultaneously improve vegetable production and mitigate greenhouse gases emission in China.

Methods

Experiment site

Field experiments were conducted in Nanjing vegetable production farm located at suburban Nanjing, Jiangsu province, China (32°04′N, 118°58′E). The experimental region is characterized by a monsoon climate with annual mean temperature of 17.8 °C and precipitation of 1090 mm over the annual experimental cycle. The experimental site is dominated by conventional open-air and plastic greenhouse vegetable cropping fields. Soils at the experimental field are classified as silt loam, consisting of 15.2% sand, 30.4% silt and 54.5% clay with an initial pH of 5.5 (1:2.5, water/soil, w/w) and an average bulk density of 1.13 g cm−3. Total N and organic C contents were 1.9 g kg−1 and 14.7 g kg−1, respectively.

Field experiments

In the 2013–2014 annual cycle, field experiment plots were established in the greenhouse vegetable cropping systems. Three parallel greenhouse vegetable cropping field blocks with an over 10-year history of continuous vegetable cultivation were selected as experimental replicates, which were identically covered with polyethylene plastic film and had no extra lighting or heating. Each replicated greenhouse comprised of four experimental treatments, referring to the controls without fertilizer application (Control), and the treatments with chemical N fertilizer applied at low (F−L, about two-third of the farmer’s conventional nitrogen input), medium (F−M, farmer’s conventional nitrogen input), and high (F−H, four-third of the conventional nitrogen input) rates. The two-paired gas-sampling plots for each treatment were randomly established in each 5 × 80 m2 grid of greenhouse vegetable field. In total, each treatment had 6 gas-sampling plots, and each field plot was 1.8 × 1.8 m2. The individual plots were separated by protection rows that were 0.5 m in width.

In line with local cropping rotations for greenhouse vegetable production systems, three vegetable crops, namely, tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), Chinese cabbage (Brassica chinensis), and green soybean (Glycine max) were consecutively cultivated, which constituted an annual fruit-leaf-legume-vegetables cropping rotation pattern. For the fertilizer treatments, compound fertilizer (N: P2O5: K2O = 15%: 15%: 15%) was used as the N fertilizer. According to the local farmer’s practice, basal N fertilizer was broadcasted on the soil surface and then incorporated into the soil by plowing. At the topdressing events, N fertilizer was first dissolved in the water and then flushed to the field with irrigation for the fertilizer plots, and the control plots were irrigated only with similar amount of water. Other management practices, including the fertilization time, irrigation and tillage, were conducted according to the local practices of the farmer. The information about the cultivation and fertilization events was detailed in Table 3.

Table 3. Vegetable cultivation and N fertilization practices in annual greenhouse vegetable cropping systems.

| Cropping system | N Fertilization (kg N ha−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropping type | Transplanting/Sowing | Harvest | Date | Type | F−L | F−M | F−H |

| Tomato | 24 Aug 2013 | 09 Jan 2014 | 23 Aug 2013 | Basal | 130 | 200 | 260 |

| 10 Oct 2013 | Top dressing | 78 | 120 | 156 | |||

| 04 Nov 2013 | Top dressing | 52 | 80 | 104 | |||

| Chinese cabbage | 04 Mar 2014 | 20 Apr 2014 | 28 Feb 2014 | Basal | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| Green soybean | 10 May 2014 | 22 Jul 2014 | 05 May 2014 | Basal | 60 | 90 | 120 |

F−L, F−M and F−H represent N fertilizer treatments at the low, conventional and high application rates, respectively.

N2O and NO fluxes measurement

Fluxes of N2O and NO were simultaneously measured using the static opaque chamber-gas chromatograph (GC) method as described in Liu et al.21 and Yao et al.9. Flux measurements were taken over the period of 26 Aug 2013 to 13 Aug 2014 (353 days) in the greenhouse vegetable cropping systems. A PVC flux collar (50 × 50 × 15 cm) was pre-installed in the middle of each plot before vegetables transplanting or sowing. The top edge of the collar had a groove (5 cm in depth) filled with water to seal the rim of a chamber during gas collection. The sampling chambers were made of opaque PVC materials at a size of 50 cm in height (or 100 cm in height depending on vegetable growth) ×50 cm in width ×50 cm in length. The chamber was wrapped with a layer of sponge and aluminum foil to minimize air temperature changes inside the chamber and equipped with a circulating fan to ensure complete gas mixing during the period of sampling. There was no difference in the vegetable planting density between inside and outside the chamber. Over the whole annual cycle, gas samples were taken twice a week, except that they were taken once every one or two days for one week following fertilizer application. Gas samples were collected between 0800 and 1000 local standard time on each sampling day. A 1.5-L gas sampling bag (Delin Gas Packing Co., LTD, Dalian, China) was used to take gas samples from the headspace at 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 min after the chambers closure, and stored for laboratory analysis within a few hours. The chamber headspace temperature was recorded for gas density correction in flux calculation using a thermometer.

The mixing ratios of N2O were quantified by a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A, USA) equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD), which was detailed in our previous studies21,50,51. A gas mixture of argon-methane (5%:95%) as N2O carrier gas was at a flow rate of 40 mL min−1. The column and ECD detector temperatures were maintained at 40 °C and 300 °C, respectively. The mixing ratio of NO was analyzed with a model 42i chemiluminescence NO-NO2-NOx analyzer (Thermo Environment InstrumentsInc., USA), which was calibrated once every two or three months using the calibration system from the same manufacture and the standard gas from the National Center of Standard Matters (Beijing, China). A nonlinear fitting approach was adopted to determine N2O and NO fluxes, as described by Kroon et al.52. Mean of fluxes taken from the paired plots represent flux measurements of the treatment within each greenhouse. Seasonal and annual cumulative N2O and NO emissions were sequentially accumulated from the emissions between every two adjacent intervals of the measurements.

Auxiliary measurements

Soil temperature and moisture (0–10 cm) were monitored when gas samples were collected using a portable rod probe (MPM-160). Soil moisture was further converted into water filled pore space (WFPS) by the following equation: WFPS = (soil volumetric water content/(1 – (soil bulk density/2.65)) ×100%). Here, 2.65 Mg m−3 was the assumed soil particle density21. Soil samples were collected prior to experiment establishment to determine background information of topsoil (0–15cm) physiochemical properties. Soil bulk density was measured using a 100 cm3 cylinder that was pressed into the soil. Soil pH was determined in a volume ratio of 1:2.5 (soil/water) with a compound glass electrode (PHS-3 C mv/pH detector, Shanghai, China). Over the whole annual cycle, soil samples at 0–15 cm depth were collected every 10–15 days for soil mineral N (NO3− and NH4+) analysis. According to the Chinese Soil Society Guidelines53, soil NO3−-N contents were measured following the two wavelength ultraviolet spectrometry at 220nm and 275nm, and NH4+-N contents were measured using indophenol blue method (HITACHI, U-2900, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

Differences in seasonal cumulative N2O and NO emissions, NO-N/N2O-N ratio and vegetable yield as affected by cropping type, N fertilizer and their interactions were examined using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Linear or nonlinear regression analyses were conducted to examine the dependence of N2O and NO emissions on soil physiochemical parameters. A linear regression model with the character of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) was used to fit N2O-N and NO-N emissions by nitrogen inputs (N) on seasonal and annual scales, in which the simulated slop and constant represented the emission factor of chemical N fertilizer for N2O (EF) and background emission of N2O, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software version 9.0.2 for Windows (SAS Inst., NC, USA, 2010).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhang, Y. et al. Response of nitric and nitrous oxide fluxes to N fertilizer application in greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in southeast China. Sci. Rep. 6, 20700; doi: 10.1038/srep20700 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NSFC (41171194, 41225003), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYT201404, NAU), the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB417102, 2015CB150502), 111 project (B12009) by Ministry of Education. Yaojun Zhang was supported by China Scholarship Council for his study in Australia.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.Z. and J.Z. conceived and designed the research; Y.Z., F.L., Y.J., X.W. and S.L. performed the experiment; Y.Z., S.L. and J.Z analyzed data; Y.Z., S.L. and J.Z. wrote the main manuscript text; Y.Z. and J.Z. reviewed the manuscript.

References

- IPCC. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds T. F. Stocker et al.) 5–14 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Smith K. A., McTaggart I. P. & Tsuruta H. Emissions of N2O and NO associated with nitrogen fertilization in intensive agriculture, and the potential for mitigation. Soil Use Manag. 13, 296–304 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Gasche R. & Papen H. A 3-year continuous record of nitrogen trace gas fluxes from untreated and limed soil of a N-saturated spruce and beech forest ecosystem in Germany: 2. NO and NO2 fluxes. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 18505–18520 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Burger M., Doane T. & Horwath W. Ammonia oxidation pathways and nitrifier denitrification are significant sources of N2O and NO under low oxygen availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 6328–6333 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciais P. et al. Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds T. F. Stocker et al.) 510–514 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Akiyama H. & Tsuruta H. Effect of organic matter application on N2O, NO, and NO2 fluxes from an Andisol field. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 17, doi: 10.1029/2002GB002016 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J. et al. Changes in fertilizer-induced direct N2O emissions from paddy fields during rice-growing season in China between 1950s and 1990s. Global Change Biol. 15, 229–242 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Nishina K., Akiyama H., Nishimura S., Sudo S. & Yagi K. Evaluation of uncertainties in N2O and NO fluxes from agricultural soil using a hierarchical Bayesian model. J. Geophys. Res. 117, doi: 10.1029/2012JG002157 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z., Liu C., Dong H., Wang R. & Zheng X. Annual nitric and nitrous oxide fluxes from Chinese subtropical plastic greenhouse and conventional vegetable cultivations. Environ. Pollut. 196, 89–97 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Xiong Z. & Yan X. Fertilizer-induced emission factors and background emissions of N2O from vegetable fields in China. Atmos. Environ. 45, 6923–6929 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. et al. Assessment of net ecosystem services of plastic greenhouse vegetable cultivation in China. Ecol. Econ. 70, 740–748 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. et al. Analysis of general situation, characteristics, existing problems and development trend of protected horticulture in China. China Veget. 18, 1–14 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Statistical Bureau. China Statistical Yearbook. China Statistics press, Beijing, 466–476 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. et al. Evaluation of current fertilizer practice and soil fertility in vegetable production in the Beijing region. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 69, 51–58 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z., Xie Y., Xing G., Zhu Z. & Butenhoff C. Measurements of nitrous oxide emissions from vegetable production in China. Atmos. Environ. 40, 2225–2234 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Ju X., Liu X., Zhang F. & Roelcke M. Nitrogen fertilization, soil nitrate accumulation, and policy recommendations in several agricultural regions of China. Ambio 33, 300–305 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju X., Kou C., Zhang F. & Christie P. Nitrogen balance and groundwater nitrate contamination: comparison among three intensive cropping systems on the North China Plain. Environ. Pollut. 143, 117–125 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J., Zhou Z., Zheng X. & Li C. Modeling impacts of fertilization alternatives on nitrous oxide and nitric oxide emissions from conventional vegetable fields in southeastern China. Atmos. Environ. 81, 642–650 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Diao T. et al. Measurements of N2O emissions from different vegetable fields on the North China Plain. Atmos. Environ. 72, 70–76 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Fang S. & Mu Y. Air/surface exchange of nitric oxide between two typical vegetable lands and the atmosphere in the Yangtze Delta, China. Atmos. Environ. 40, 6329–6337 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Qin Y., Zou J., Guo Y. & Gao Z. Annual nitrous oxide emissions from open-air and greenhouse vegetable cropping systems in China. Plant Soil 370, 223–233 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Pang X. et al. Nitric oxides and nitrous oxide fluxes from typical vegetables cropland in China: Effects of canopy, soil properties and field management. Atmos. Environ. 43, 2571–2578 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Mei B. et al. Characteristics of multiple-year nitrous oxide emissions from conventional vegetable fields in southeastern China. J. Geophys. Res. 116, doi: 10.1029/2010JD015059 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Jiang R., Chen Q., Zhang F. & Su F. Nitrous oxide emissions from an intensively managed greenhouse vegetable cropping system in Northern China. Environ. Pollut. 157, 1666–1672 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman A. F., Boumans L. J. M. & Batjes N. H. Emissions of N2O and NO from fertilized fields: Summary of available measurement data. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 16, doi: 10.1029/2001GB001811 (2002). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoben J. P., Gehl R. J., Millar N., Grace P. R. & Robertson G. P. Nonlinear nitrous oxide (N2O) response to nitrogen fertilizer in on-farm corn crops of the US Midwest. Global Change Biol. 17, 1140–1152 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yan G. et al. Two-year simultaneous records of N2O and NO fluxes from a farmed cropland in the northern China plain with a reduced nitrogen addition rate by one-third. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 178, 39–50 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Li B., Chen Z., Xie Z. & Xiong Z. Effects of biochar application on vegetable production and emissions of N2O and CH4. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 58, 503–509 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Chen G., Xu H., Zhang Y. & Zhang X. The contribution of maize and soybean to N2O emission from the soil plant system during seedling stage. Environ. Sci. 24, 38–42 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F., Chen Q., Jiang R., Chen X. & Zhang F. Yield and nitrogen balance of greenhouse tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.) with conventional and site-specific nitrogen management in Northern China. Nutr. Cycling Agroecosyst. 77, 1–14 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Min J., Shi W., Xing G., Powlson D. & Zhu Z. Nitrous oxide emissions from vegetables grown in a polytunnel treated with high rates of applied nitrogen fertilizers in Southern China. Soil Use Manag. 28, 70–77 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Mei B. et al. Nitric oxide emissions from conventional vegetable fields in southeastern China. Atmos. Environ. 43, 2762–2769 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Li D. & Wang X. Nitric oxide emission from a typical vegetable field in the Pearl River Delta, China. Atmos. Environ. 41, 9498–9505 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Kesik M., Blagodatsky S., Papen H. & Butterbach-Bahl K. Effect of pH, temperature and substrate on N2O, NO and CO2 production by Alcaligenes faecalis p. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101, 655–667 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J. et al. Annual emissions of nitrous oxide and nitric oxide from rice-wheat rotation and vegetable fields: a case study in the Tai-Lake region, China. Plant Soil 360, 37–53 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W., Liu J., Hu C., Sun X. & Tan Q. Effects of nitrogen and soil moisture on nitrous oxide emissions from an alfisol in Wuhan, China. J. Food Agric. Environ. 8, 592–596 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Han S., Huang Y., Wang Y. & Wang M. Re-quantifying the emission factors based on field measurements and estimating the direct N2O emission from Chinese croplands. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 18, doi: 10.1029/2003GB002167 (2004). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B., Ju X. T., Zhang Q., Christie P. & Zhang F. S. New estimates of direct N2O emissions from Chinese croplands from 1980 to 2007 using localized emission factors. Biogeosciences 8, 3011–3024 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Shimizu K., Akimoto H. & Ohara T. Determining fertilizer-induced NO emission ratio from soils by a statistical distribution model. Biol. Fertil. Soils 39, 45–50 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. et al. Nitric oxide emissions from rice-wheat rotation fields in eastern China: effect of fertilization, soil water content, and crop residue. Plant Soil 336, 87–98 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gu J. et al. Regulatory effects of soil properties on background N2O emissions from agricultural soils in China. Plant Soil 295, 53–65 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Gu J., Zheng X. & Zhang W. Background nitrous oxide emissions from croplands in China in the year 2000. Plant Soil 320, 307–320 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Lu Y. & Huang Y. Estimates of synthetic fertilizer N-induced direct nitrous oxide emission from Chinese croplands during 1980–2000. Environ. Pollut. 158, 631–635 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestone M. K. & Davidson E. A. Microbiological basis of NO and N2O production and consumption in soil (eds Andreae M. O. & Schimel D. S.) 7–21 (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- McSwiney C. P. & Robertson G. P. Nonlinear response of N2O flux to incremental fertilizer addition in a continuous maize (Zea mays L.) cropping system. Global Change Biol. 11, 1712–1719 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. A., Keller M., Erickson H. E., Verchot L. V. & Veldkamp E. Testing a conceptual model of soil emissions of nitrous and nitric oxides. Bioscience 50, 667–680 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Skiba U. & Ball B. The effect of soil texture and soil drainage on emissions of nitric oxide and nitrous oxide. Soil Use Manag. 18, 56–60 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Lan T., Han Y., Roelcke M., Nieder R. & Cai Z. Processing leading to N2O and NO emissions from two different Chinese soils under different soil moisture contents. Plant Soil 371, 611–627 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Erickson H. E. & Perakis S. S. Soil fluxes of methane, nitrous oxide, and nitric oxide from aggrading forests in coastal Oregon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 76, 268–277 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Huang Y., Jiang J., Sass R. & Zheng X. A 3-year field measurement of methane and nitrous oxide emission from rice paddies in China: Effects of water regime, crop residue, and fertilizer application. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19, doi: 10.1029/2004GB002401 (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X. et al. Quantification of N2O fluxes from soil-plant systems may be biased the applied gas chromatograph methodology. Plant Soil 311, 211–234 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Kroon P. S., Hensen A., van den Bulk W. C. M., Jongejan P. A. C. & Vermeulen A. T. The importance of reducing the systematic error due to non-linearity in N2O flux measurements by static chambers. Nutri. Cycling Agroecosyst. 82, 175–186 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Lu R. K. Methods for Soil Agro-chemistry Analysis 157–160 (Agricultural Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 2000). [Google Scholar]