Abstract

Background

The sensory belief that ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes are smoother can also influence the belief that ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes are less harmful. However, the ‘light’ concept is one of several factors influencing beliefs. No studies have examined the impact of the sensory belief about one’s own brand of cigarettes on perceptions of harm.

Objective

The current study examines whether a smoker’s sensory belief that their brand is smoother is associated with the belief that their brand is less harmful and whether sensory beliefs mediate the relation between smoking a ‘light/low tar’ cigarette and relative perceptions of harm among smokers in China.

Methods

Data are from 5209 smokers who were recruited using a stratified multistage sampling design and participated in wave 3 of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey, a face-to-face survey of adult smokers and non-smokers in seven cities.

Results

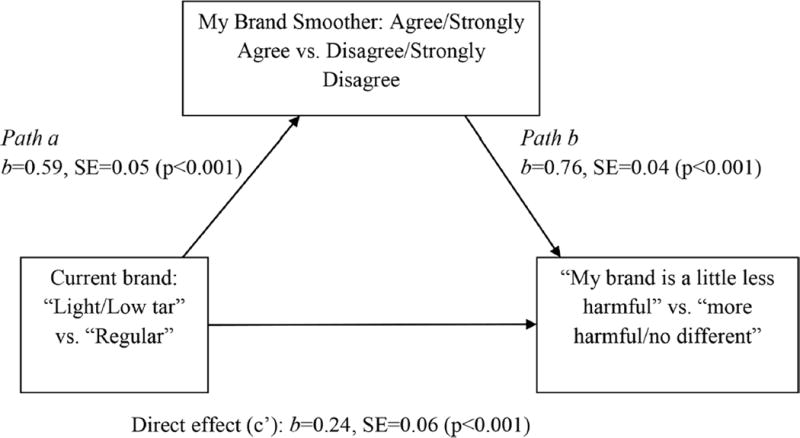

Smokers who agreed that their brand of cigarettes was smoother were significantly more likely to say that their brand of cigarettes was less harmful (p<0.001, OR=6.86, 95% CI 5.64 to 8.33). Mediational analyses using the bootstrapping procedure indicated that both the direct effect of ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers on the belief that their cigarettes are less harmful (b=0.24, bootstrapped bias corrected 95% CI 0.13 to 0.34, p<0.001) and the indirect effect via their belief that their cigarettes are smoother were significant (b=0.32, bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% CI 0.28 to 0.37, p<0.001), suggesting that the mediation was partial.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the importance of implementing tobacco control policies that address the impact that cigarette design and marketing can have in capitalising on the smoker’s natural associations between smoother sensations and lowered perceptions of harm.

INTRODUCTION

Despite evidence that ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes are just as harmful as ‘regular’ cigarettes,1,2 many smokers continue to believe that these cigarettes are less harmful.3–6 Descriptors such as ‘light’, or ‘mild’, and features of the cigarette package, including shape, colours, numbers or symbols are used to convey information about the relative health risks associated with a particular brand.7,8 To deter misperceptions of risk, bans on misleading descriptors such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’ have been implemented by 95 countries to date in accordance with Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).9 However, research suggests that these bans are not sufficient.10,11

One potential limitation of these bans is that they fail to address other important characteristics of the cigarette and package designs that also create erroneous risk perceptions. Sensory beliefs are used as indicators of relative harm.12 A key factor associated with the belief that ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes are less harmful is the belief that these cigarettes are smoother.3,6,13,14 Cigarettes labelled with a ‘smooth’ descriptor (not covered under these bans) are perceived to be less harmful.7,8 Experimental research has demonstrated that addressing perceptions of the smoothness of ‘light’ cigarettes appears to be the most effective way to change smokers’ perceptions about the relative harm of ‘light’ cigarettes.14

Existing research focuses on beliefs about the smoothness and harm of ‘light’ cigarettes. Focusing on ‘light’ descriptors alone is limited because cigarettes in many countries are no longer labelled with these explicit descriptors. Moreover, ‘light’ descriptors are one of several factors that reinforce the belief that a particular cigarette is smoother, including: the physical engineering of the cigarette (eg, filter ventilation),15,16 nicotine levels,17 lighter package colour,18–20 softer packaging,20 pack shape (eg, rounded corners)21 and descriptors such as ‘smooth’ or ‘silver’ on the cigarette packaging.18

The issue of whether the smoker’s own sensory perceptions of the cigarettes they smoke relate to the belief that their particular brand of cigarettes is less harmful is important and warrants further study. The current study is an extension of the existing research demonstrating a link between the belief that ‘light’ and ‘low tar’ cigarettes are smoother and the belief that ‘light’ and ‘low tar’ cigarettes are less harmful among smokers in China.13 The study focuses on how Chinese smokers’ perception of their own brand of cigarettes relates to the belief that their cigarette is less harmful. It is particularly important to improve tobacco control research efforts in China because it has the largest consumption of cigarettes in the world.22 China banned descriptors such as ‘light’, ‘mild’ or ‘low tar’ on cigarette packages in January 2006 in accordance with Article 11 of the WHO FCTC. However, marketing ‘low tar’ cigarettes as less harmful has been and continues to be one of the key strategies to counter tobacco control in China.23 Initiatives have included: developing lower tar cigarettes, regulating increasingly lower maximum tar thresholds, and conducting research to purportedly demonstrate that these lower tar cigarettes are less harmful.23–25

A high proportion of smokers in China continue to believe that ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes are less harmful.13,22 The factor most strongly associated with belief that ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes are less harmful was the belief that these cigarettes were smoother.13 Use of ‘low tar’ cigarettes is also on the rise as more smokers in China become health concerned and as maximum tar levels are decreased.25 Lower tar yields are accomplished mainly by increasing the filter ventilation in cigarettes,26 and filter ventilation is a significant contributor to the perception that a brand is smoother.16 An increasing number of smokers in China are therefore smoking cigarettes that may feel smoother due to the increased filter ventilation. Thus, examining how sensory beliefs relate to perceptions of harm is particularly important in China.

The current paper uses a population-level survey of smokers from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey to test whether smokers who believe that their cigarette brand is smoother were significantly more likely to believe that their cigarette brand is less harmful. We also examined the extent to which smokers’ sensory beliefs might mediate the relation between smoking ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes and the belief that their cigarettes are less harmful. We hypothesised that ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers would be more likely to say that their brand of cigarettes is less harmful to the extent that they believed that their brand of cigarettes is smoother.

METHODS

Participants

Respondents are from wave 3 of the ITC China Survey conducted from May to October 2009 in seven cities: Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenyang, Yinchuan, Shanghai, Changsha and Kunming. The paper is restricted to data from the wave 3 survey because the question asking smokers whether they smoked a cigarette that was described as ‘light’ or ‘low tar’ was added in wave 3. Respondents at wave 3 were either initially recruited in wave 1 or wave 2 (n=3549) or were recruited for the first time during wave 3 as part of the replenishment sample (n=1660). Kunming was added to the ITC China Project at wave 3. Only smokers were included in the analyses for this paper. The total sample size for this study was 5209.

Procedures

The ITC China Survey uses a stratified multistage cluster sampling design where each city is a stratum. Within each city, Jie Dao (street districts) were randomly selected and within each of the Jie Dao, residential blocks (Ju Wei Hui) were randomly selected. The probability of selection was proportional to the population size of the Jie Dao/Ju Wei Hui. Within the selected Ju Wei Hui, a complete list of household addresses was compiled and then a random sample of houses was drawn from the list using simple random sampling without replacement. Respondents within households were selected using the next birthday method where there was more than one person in a sampling category (smoker, non-smoker, etc).27

The smoker survey was a 40 min face-to-face survey conducted in Chinese by experienced survey interviewers specially trained to conduct the ITC China Survey. Respondents were given a small gift worth approximately ¥20 in appreciation for their participation. This compensation is typical for survey participation in China.

Research ethics approval was obtained from: the University of Waterloo, Canada, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, USA, the Cancer Council Victoria, Australia, and the Chinese National Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China. Further details about the ITC China Survey protocol and specific details about the wave 3 sampling, protocols and weight construction can be found online.27,28

Measures

Dependent variable: belief about respondents’ own brand of cigarettes

Respondents were asked: “Do you think that the brand you usually smoke might be a little less harmful, no different, or a little more harmful, compared to other cigarette brands?” Responses were: 1=“A little less harmful,” 2=“No different,” 3=“A little more harmful.” This variable was recoded so that 1=“A little less harmful” and 0=“A little more harmful/No different/don’t know.” Refused (n=25) responses were excluded.

Key Predictors

Sensory beliefs about own brand

Respondents were asked whether “The brand of cigarettes I usually smoke is smoother on my respiratory (throat and chest) system than other cigarette brands.” Response options were on a five-point Likert scale from 1=“Strongly disagree” to 5=“Strongly agree.” For the purpose of this analysis, sensory beliefs were coded as follows: 1=“Strongly agree/Agree” and 0=“Strongly disagree/Disagree/Neither/Don’t know.”

Self-reported use of ‘light’ and ‘low tar’ cigarettes

Respondents reported whether they currently smoked a cigarette that was described as ‘light’, ‘mild’ or ‘low tar’ (response options were: ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Don’t know’).

Potential covariates

Standard demographic measures included: sex, age (18–39, 40–54, 55+), ethnicity (Han vs ‘other’ ethnic groups), household income per month (categorised as: “Low<1000 Yuan per month,” “Medium≥1000 Yuan to 2999 Yuan,” “High≥3000 Yuan,” “don’t know/refused”), education (categorised as: “Low=No education or elementary school,” “Medium=Junior high school or high school/technical high school,” “High=College, university or higher”) and city. Measures of cigarette consumption included: smoking ‘every day’ vs ‘some days’ and cigarettes smoked per day (0–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31+).

Knowledge of health effects of smoking

Respondents were asked whether smoking causes: stroke, lung cancer in smokers, emphysema, premature ageing, cardiovascular heart disease, oral cancer, impotence in male smokers, lung cancer in non-smokers from second-hand smoke; second-hand smoke causes chronic respiratory diseases in non-smokers; second-hand smoke causes heart attacks in non-smokers and secondhand smoke causes pregnant women to miscarry and have underweight babies. Responses were coded so that “No/Don’t know”=0 and “Yes”=1. The measure of health knowledge was the sum of all responses.

Health concerns about smoking

To assess health concerns, respondents were asked: “To what extent, if at all, has smoking damaged your health?” and “How worried are you, if at all, that smoking will damage your health in the future?” (“Not at all/Don’t know,” “A little” and “Very much”). Respondents were also asked: “In general, how would you describe your health?” 1=“Poor” to 5= “Excellent.” In addition, respondents were asked to what extent they considered themselves addicted to cigarettes (“Not at all,” “A little,” “Somewhat” and “A lot”). “Don’t know” or missing responses were excluded (n=12).

Statistical analyses

SAS (V.9.3) was used for all statistical analyses except the mediation which used M-PLUS (V.6.11). Unweighted and weighted (using PROC SURVEYFREQ) frequencies were calculated for key variables. Weights were based on the number of people in the city population and the sampling category (household, residential block and street district). χ2 analyses were used to determine whether there were significant differences in the proportion of respondents who thought that their cigarettes were: (A) smoother and (B) less harmful by type of cigarette smoked (‘light/low tar’, ‘regular’ or ‘don’t know’). A weighted logistic regression equation using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC was used to determine whether the belief that your cigarette brand is smoother was significantly associated with the belief that your cigarette brand is less harmful after adjusting for all covariates including current use of ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes. The covariates reported in the results were entered in step 1 and the belief that your brand is smoother was entered in step 2. Models were adjusted for strata and cluster (Jie Dao, Ju Wei Hui). The mediation analysis was conducted using M-Plus based on the protocol defined by Hayes29 to test whether the belief that your brand is smoother mediates the relation between being a ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smoker (vs regular/don’t know) and the belief that your brand is less harmful. Bootstrapped bias corrected 95% CIs of the direct and indirect effect were computed with 5000 bootstrapped samples (no adjustments were made for additional covariates in this simple test of the mediation).29

RESULTS

Online supplementary table S1 presents the unweighted and weighted (respectively) sample characteristics for respondents from the ITC China wave 3 Survey. Overall, the majority of smokers in our sample (74.5% weighted) reported that they currently smoked cigarettes described as ‘light’, ‘mild’ or ‘low tar’.

Smokers’ beliefs about their usual brand of cigarettes

Table 1 presents smokers’overall beliefs about their own brand of cigarettes at wave 3 stratified by the type of cigarettes smoked. The majority of smokers ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that their brand was smoother on the respiratory system (throat and chest) than other brands (52.8%). A greater proportion of ‘light/low tar’ smokers ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that their brand of cigarettes was smoother (58.3%) compared to ‘regular’ cigarette smokers (35.3%) and respondents who did not know whether their cigarettes were ‘light/low tar’ (41.4%). Both differences were statistically significant (p<0.001). A minority of smokers in our sample said that their brand was a little less harmful than other brands of cigarettes (28.3%). ‘Light/low tar’ cigarette smokers were significantly more likely to say that their brand was a little less harmful than other brands (32.6%) than were ‘regular’ cigarette smokers (16.1%) and smokers who did not know whether their cigarettes were ‘light/low tar’ (13.6%; both comparisons p<0.001).

Table 1.

Smokers’ beliefs about their usual cigarette brand: International Tobacco Control (ITC) China (Wave 3 weighted percentages)

| Factor | Overall (N=5166) (%) | ‘Light/low tar’ cigarette smokers (n=3829) (%) | ‘Regular’ cigarette smokers (n=1050) (%) | ‘Don’t know brand type’ cigarette smokers (n=287) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My brand is smoother | χ2 (df=10)=256.86, p<0.001 | |||

| Strongly disagree | 2.6 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 1.5 |

| Disagree | 23.8 | 21.1 | 34.6 | 21.9 |

| Neutral | 15.7 | 13.9 | 21.1 | 20.3 |

| Agree | 50.5 | 55.7 | 33.4 | 40.9 |

| Strongly agree | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 0.5 |

| Don’t know | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 15.0 |

| My brand | χ2 (df=6)=284.64, p<0.001 | |||

| No different | 60.4 | 58.8 | 66.9 | 59.5 |

| A little less harmful | 28.3 | 32.6 | 16.1 | 13.6 |

| A little more harmful | 4.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 3.6 |

| Don’t know | 7.3 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 23.3 |

Factors associated with the belief that “my own brand of cigarettes is less harmful”

Table 2 presents the results of a weighted logistic regression to determine which factors at wave 3 were associated with the belief that “my own brand of cigarettes is a little less harmful.” Respondents who were older were significantly more likely to say that their brand of cigarettes was less harmful than other brands (40–54 vs 18–39: p<0.001, OR=1.79, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.28; 55+ vs 18–39: p<0.001, OR=2.11, 95% CI 1.71 to 2.61). Respondents who were worried that smoking would damage their health in the future were more likely to believe that their cigarettes were less harmful (‘a little’ vs ‘not at all/don’t know’: p=0.002, OR=1.37, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.67). Current ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers were significantly more likely to say that their brand of cigarettes was less harmful than other brands (p<0.001, OR=2.42, 95% CI 1.93 to 3.04). Smokers who agreed that their brand of cigarettes was smoother were significantly more likely to say that their brand of cigarettes was less harmful (p<0.001, OR=6.86, 95% CI 5.64 to 8.33).

Table 2.

Logistic regression of the belief that “my usual brand is less harmful”: International Tobacco Control (ITC) China wave 3

| Factor | n | My brand less harmful (%)*† | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1419 | 28.1 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Female | 87 | 31.8 | 1.08 (0.83 to 1.41) | 0.57 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39 | 232 | 18.8 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 40–54 | 697 | 29.2 | 1.79 (1.41 to 2.28) | <0.001 |

| 55+ | 577 | 32.9 | 2.11 (1.71 to 2.61) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Han | 1418 | 28.5 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Other | 86 | 25.6 | 1.07 (0.82 to 1.39) | 0.64 |

| Income | ||||

| Low | 132 | 26.3 | 0.87 (0.65 to 1.18) | 0.38 |

| Medium | 573 | 27.3 | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.12) | 0.38 |

| High | 714 | 29.4 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Don’t Know/Refused | 84 | 28.1 | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.62) | 0.56 |

| Education | ||||

| Low | 173 | 30.4 | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.37) | 0.95 |

| Medium | 965 | 27.9 | 0.89 (0.73 to 1.07) | 0.22 |

| High | 365 | 28 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Smoking behaviour | ||||

| Every day | 1418 | 28.1 | 0.96 (0.64 to 1.43) | 0.83 |

| Some days | 88 | 31.6 | 1.00 (reference) Cigarettes per day |

|

| 0–10 | 630 | 30.6 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 11–20 | 663 | 26.7 | 0.88 (0.72 to 1.06) | 0.18 |

| 21–30 | 127 | 27.3 | 0.92 (0.63 to 1.35) | 0.67 |

| 31+ | 86 | 28.3 | 0.95 (0.63 to 1.43) | 0.8 |

| Health knowledge | ||||

| 0 | 151 | 26.5 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03)‡ | 0.71 |

| 1 | 55 | 29.8 | ||

| 2 | 80 | 26.3 | ||

| 3 | 78 | 24 | ||

| 4 | 116 | 30.4 | ||

| 5 | 126 | 28.8 | ||

| 6 | 138 | 25.8 | ||

| 7 | 148 | 29.3 | ||

| 8 | 150 | 30.2 | ||

| 9 | 119 | 25 | ||

| 10 | 156 | 30.6 | ||

| 11 | 188 | 30.2 | ||

| Current brand | ||||

| ‘Regular’ | 168 | 16.1 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| ‘Light/low tar’ | 1291 | 32.7 | 2.42 (1.93 to 3.04) | <0.001 |

| Don’t know | 44 | 13.6 | 0.82 (0.54 to 1.24) | 0.34 |

| Health Concern | ||||

| Worried smoking has damaged health | ||||

| Very much | 204 | 26.4 | 0.87 (0.63 to 1.17) | 0.34 |

| A little | 795 | 28.9 | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.13) | 0.43 |

| Not at all/don’t know | 498 | 28 | 1.00 (reference) Worried smoking will damage health | |

| Very much | 305 | 27.7 | 1.29 (0.94 to 1.77) | 0.11 |

| A little | 765 | 30.3 | 1.37 (1.12 to 1.67) | 0.002 |

| Not at all/don’t know | 430 | 25.3 | 1.00 (reference) Describe your health | |

| 1 Poor | 38 | 31.6 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 2 | 76 | 27.3 | 0.80 (0.44 to 1.45) | 0.46 |

| 3 | 689 | 27.4 | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.24) | 0.3 |

| 4 | 481 | 28.5 | 0.82 (0.50 to 1.35) | 0.43 |

| 5 Excellent | 213 | 30.3 | 0.90 (0.55 to 1.47) | 0.67 |

| Perceived Addiction | ||||

| Not at all | 180 | 32.8 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| A little | 806 | 28.5 | 0.84 (0.63 to 1.12) | 0.24 |

| Somewhat | 389 | 27.7 | 0.86 (0.64 to 1.14) | 0.28 |

| A lot | 129 | 24 | 0.70 (0.45 to 1.08) | 0.1 |

| My brand smoother | ||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 1239 | 44.7 | 6.86 (5.64 to 8.33) | <0.001 |

| Disagree/strongly Disagree/neither/don’t know | 264 | 10.1 | 1.00 (reference) |

Response options for my brand less harmful ‘a little less’ n=1473 and ‘no different/a little more’ n=3588.

Controlling for city.

The belief prevalences presented for each response category of each factor are not adjusted for the other predictor variables in the model. These prevalences and the reported sample sizes represent the respondents who endorsed the belief that their brand is less harmful in each category.

Continuous variable

Testing whether perceptions of smoothness is a mediator of the relation between ‘light/low tar’ smoking and perceptions of harmfulness

Figure 1 reports the results of the mediation analysis. The estimate for the indirect effect of ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers on the belief that their cigarettes are less harmful via their belief that their cigarettes are smoother was significant (b=0.32, bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% CI 0.28 to 0.37, p<0.001). ‘Light/low tar’ cigarette smokers are more likely to believe that their cigarettes are less harmful to the extent that they believe their cigarettes are smoother. The direct effect was also significant (b=0.24, bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% CI 0.13 to 0.34, p<0.001), which indicated that the mediation was partial and other factors may also mediate this association. Overall, the mediational model accounted for 39.7% of the variance in beliefs about the harmfulness of one’s own brand.

Figure 1.

Reports the results of the mediation analysis.

DISCUSSION

This study of a probability sample of smokers across seven cities in China found that smokers who perceive that their cigarettes are smoother than other brands are more likely to say that their brands are less harmful. The magnitude of this association is remarkable (OR=6.86) and demonstrates how important sensory beliefs are to smokers’ belief that their brand is less harmful. Consistent with previous research, ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers were more likely to say that their brand of cigarettes was less harmful.13 Few other factors (age, health concern) predicted this belief. ‘Light/low tar’ cigarette smokers were also more likely to say that their brand of cigarette was smoother compared to that of ‘regular’ cigarette smokers. There was evidence of a mediation effect wherein ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers were more likely to say that their cigarettes were less harmful to the extent that they believed that their brand of cigarettes was smoother. The mediation was only partial, suggesting that smoothness is only one of the factors that influences ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers’ perceptions that their cigarettes may be less harmful.

The data for this study were collected several years after a voluntary removal of ‘light’ and ‘low tar’ descriptors in China in accordance with Article 11 of the WHO FCTC. However, the majority of respondents in our survey indicated that they smoked a ‘light’ or ‘low tar’ cigarette. Given that smokers, particularly those who reported smoking ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes, are more likely to believe that their brand is less harmful, this suggests that consistent with research in other jurisdictions the removal of ‘light’ descriptors is not sufficient to eliminate misperceptions.10,11 Moreover, the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (STMA) in China further perpetuated the belief that ‘low tar’ cigarettes are less harmful through their ‘low tar less harm’ campaign,23 and these results suggest that this strategy was effective. Tobacco control policies and programmes to remove misperceptions about the relative harms of cigarettes in China, including eliminating the low tar less harm campaign, are therefore urgently needed.

The majority of smokers in our sample believed that their brand of cigarettes was smoother than other brands (52.8%). We would anticipate that ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smokers would believe that their cigarettes were smoother.3 However, a high proportion of respondents who did not know whether their cigarette brand was ‘light/low tar’ or who smoked a ‘regular’ cigarette also said that their brand of cigarettes was smoother. As previously mentioned, the belief that ‘your brand is smoother than other brands’ derives from many factors beyond ‘light/low tar’ descriptors. Smokers in China may also feel that their brands are smoother because overall cigarettes in China are likely to have become smoother with the increase in filter ventilation over time.30 This finding therefore highlights the importance of examining beliefs about smokers’ own brand of cigarettes rather than their beliefs about ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes, especially in those countries where such explicit descriptors have been eliminated.

The market share of ‘low tar’ cigarettes is on the rise in China, possibly because awareness of the health risks of smoking is on the rise and the government has been promoting the use of ‘low tar’ cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy.23,25 Smokers may be choosing ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes as a way to reduce their health risks. The rate of respondents indicating that they smoked a ‘light/low tar’ cigarette was also high, but this may reflect the fact that the definition of ‘low tar’ cigarettes has changed over time, and relatively speaking, most Chinese cigarettes are lower in tar compared with what they were previously.30

Recent tobacco control policies addressing the issue of ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes have focused on banning ‘light’ and ‘low tar’ descriptors in countries such as China. However, these regulations do not specifically address the association between smokers’ sensory beliefs and risk perceptions. More recently, the Australian government has implemented plain packaging regulations specifying the removal of colours, brand imagery, trademarks and logos. Research has demonstrated that plain packaging reduces perceived cigarette smoothness.31 Implementation of plain packaging is therefore a good first step in reducing sensory beliefs and risk perceptions. However, this research suggests that the introduction of plain packaging alone may not be sufficient. ‘Light/low tar’ cigarettes are designed to taste smoother. Therefore, to truly eliminate the association between the sensory characteristics of ‘light/low tar’ cigarettes and the perception that these cigarettes are less harmful, there would also need to be regulations on the cigarette design. Articles 9 and 10 of the FCTC pertain to tobacco product regulation. These articles could be used to regulate any aspects of the cigarette design that create the perception that a particular cigarette is smoother and therefore less harmful.

Limitations

We relied on smokers’ self-reports to determine whether they smoked a ‘light/low tar’ cigarette. Respondents could have incorrectly identified themselves as a ‘light/low tar’ cigarette smoker. We do not directly assess the engineering and other cigarette package design features which affect smokers’ sensory experience and perceptions of risks of their own brands. Had we been able to use information about the engineering of the cigarette and package design, we could have also tested whether smoothness mediated the relation between these factors and perceptions of relative harm. Future research should incorporate these factors rather than relying solely on respondents’ self-reported use of ‘light’ cigarettes.

Sensory perceptions may also be related to other factors that were not considered in depth in this paper such as personal smoking style, smoking history and severity of dependence. Additional research studies should examine whether these factors are related to perceptions of smooth and relative harm.

The paper presents findings from a representative sample of smokers in seven cities in China. However, given that experimental studies in other jurisdictions have demonstrated a strong connection between sensory beliefs and perceptions of harm, we would anticipate that the findings should generalise elsewhere. Research in other jurisdictions should be conducted to replicate these findings.

CONCLUSION

Smokers’ beliefs about the harmfulness of their cigarettes are highly associated with their sensory beliefs. ‘Light/low tar’ cigarette smokers are more likely to say that their cigarettes are less harmful to the extent that they believe that their cigarettes are smoother. These findings demonstrate the importance of implementing tobacco control policies that address the impact that cigarette design and marketing can have in capitalising on a smoker’s natural associations between smoother sensations and lowered perceptions of harm.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Harris JE, Thun MJ, Mondul AM, et al. Cigarette tar yields in relation to mortality from lung cancer in the cancer prevention study II prospective cohort, 1982–8. BMJ. 2004;328:72–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37936.585382.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thun MJ, Burns DM. Health impact of “reduced yield” cigarettes: a critical assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Tob Control. 2001;10(Suppl 1):i4–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.suppl_1.i4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borland R, Yong HH, King B, et al. Use of and beliefs about light cigarettes in four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S311–21. doi: 10.1080/1462220412331320716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kropp RY, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents’ beliefs about the risks involved in smoking “light” cigarettes. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e445–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollay RW. Targeting youth and concerned smokers: evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2000;9:136–47. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiffman S, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL, et al. Smokers’ beliefs about “light” and “ultra light” cigarettes. Tob Control. 2001;10(Suppl 1):i17–23. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.suppl_1.i17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond D, Dockrell M, Arnott D, et al. Cigarette pack design and perceptions of risk among UK adults and youth. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:631–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond D, Parkinson C. The impact of cigarette package design on perceptions of risk. J Public Health. 2009;31:345–53. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO) 2012 Global progress report on implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO; 2012. http://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/2012_global_progress_report_en.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borland R, Fong GT, Yong HH, et al. What happened to smokers’ beliefs about light cigarettes when “Light/Mild” brand descriptors were banned in the UK? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2008;17:256–62. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.023812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yong H-H, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Impact of the removal of misleading terms on cigarette pack on smokers’ beliefs about light/mild cigarettes: cross-country comparisons. Addiction. 2011;106:2204–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutti S, Hammond D, Borland R, et al. Beyond light and mild: cigarette brand descriptors and perceptions of risk in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2011;106:1166–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elton-Marshall T, Fong GT, Zanna MP, et al. Beliefs about the relative harm of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tob Control. 2010;19(Suppl 2):i54–62. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.029025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiffman S, Pillitteri JL, Burton SL, et al. Effect of health messages about “Light” and “Ultra Light” cigarettes on beliefs and quitting intent. Tob Control. 2001;10(Suppl 1):i24–32. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.suppl_1.i24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozlowski LT, O’Connor RJ. Cigarette filter ventilation is a defective design because of misleading taste, bigger puffs, and blocked vents. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):I40–50. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor RJ, Caruso RV, Borland R, et al. Relationship of cigarette-related perceptions to cigarette design features: findings from the 2009 ITC U.S. Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1943–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKinney DL, Frost-Pineda K, Oldham MJ, et al. Cigarettes with different nicotine levels affect sensory perception and levels of biomarkers of exposure in adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:948–60. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, et al. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:674–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. The dark side of marketing seemingly “light” cigarettes: successful images and failed fact. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):i18–31. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, et al. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002;11:i73–80. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotnowski K, Hammond D. The impact of cigarette pack shape, size and opening: evidence from tobacco company documents. Addiction. 2013;108:1658–68. doi: 10.1111/add.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) China 2010 Country Report. Beijing, China: Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang G. Marketing ‘less harmful, low-tar’ cigarettes is a key strategy of the industry to counter tobacco control in China. Tob Control. 2014;23:167–72. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Euromonitor International. 2012 http://www.euromonitor.com/tobacco-in-china/report (accessed 18 Jul 2014)

- 25.Tobacco China. Low tar, low harm: a new chapter for cigarette consumption. 2011 http://www.tobaccochina.com/zt/2011Lowcoke/first.html (accessed11 Aug 2014)

- 26.King W, Borland R. The “low tar” strategy and the changing construction of Australian cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:85–94. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C, Thompson ME, Fong GT, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tob Control. 2010;19(Suppl 2):i1–5. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.029900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ITC China Research Team. Wave 3(2009) ITC China Technical Report. Waterloo: ITC; 2011. International Tobacco Control China Survey Wave. http://www.itcproject.org/files/Report_Publications/Technical_Report/cn3_trrevisedfinalaqsept92011.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes AF. http://www.afhayes.com/macrofaq.html (accessed 18 Jul 2014)

- 30.Schneller LM, Zwierzchowski BA, Caruso RV, et al. Changes in tar yields and cigarette design in samples of Chinese cigarettes, 2009–2012. Tob Control. 2014 Oct 28; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051803. Published Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White CM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF, et al. The potential impact of plain packaging of cigarette products among Brazilian young women: an experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:737. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.