Abstract

We describe enrollment for the One Thousand Strong panel, present characteristics of the panel relative to other large U.S. national studies of gay and bisexual men (GBM), and examine demographic and behavioral characteristics that were associated with passing enrollment milestones. A U.S. national sample of HIV-negative men were enrolled via an established online panel of over 22,000 GBM. Participants (n = 1071) passed three milestones to join our panel. Milestone 1 was screening eligible and providing informed consent. Milestone 2 involved completing an hour-long at-home computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) survey. Milestone 3 involved completing at-home self-administered rapid HIV testing and collecting/returning urine and rectal samples for gonorrhea and chlamydia testing. Compared to those who completed milestones: those not passing milestone 1 were more likely to be non-White and older; those not passing milestone 2 were less likely to have insurance or a primary care physician; and those not passing milestone 3 were less educated, more likely to be bisexual as opposed to gay, more likely to live in the Midwest, had fewer male partners in the past year, and less likely to have tested for HIV in the past year. Effect sizes for significant findings were small. We successfully enrolled a national sample of HIV-negative GBM who completed at-home CASI assessments and at-home self-administered HIV and urine and rectal STI testing. This indicates high feasibility and acceptability of incorporating self-administered biological assays into otherwise fully online studies. Differences in completion of study milestones indicate a need for further investigation into the reasons for lower engagement by certain groups.

Keywords: men who have sex with men, condomless anal sex, venues, bars/clubs, Internet, sex parties, gay and bisexual men, recruitment, HIV, STI testing

Introduction

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM) represent between 4–15% of the U.S. population (Herbenick et al., 2010; Purcell et al., 2012), but accounted for 68% of all new HIV infections in 2013, and 84% of all new infections among males (CDC, 2015b); a 12% increase from 2009 to 2013 (CDC, 2015a). As a result of the continuing HIV epidemic, much of researchers’ attention to GBM has been grounded in HIV prevention. Moreover, much of what we know about GBM has been based on samples where HIV has taken its greatest toll—those in urban epicenters and who report HIV sexual risk behaviors. As a result, less is known about U.S. GBM who live outside of urban centers and those who do not report recent sexual risk.

Up until the 21st century, it had been logistically challenging to study non-urban GBM both because of geographic dispersion across rural areas and relative invisibility of sexual minority individuals outside of urban setting (Bell & Valentine, 1995; D’Augelli & Hart, 1987; Mustanski, 2001; Preston & D’Augelli, 2013; Williams, Bowen, & Horvath, 2005). However, that changed with expanded use of the Internet both by GBM as well as researchers (Bowen, 2005; Holloway, Dunlap, et al., 2014; Mustanski, 2001; Sullivan, Grey, & Rosser, 2013). Using keyword searches of common terms (e.g., MSM, gay, bisexual, Internet, HIV, online) in behavioral, psychological, and health research databases (e.g., PsychInfo, Google Scholar, EBSCO, PubMed), we sought to provide an overview of the state of online studies for GBM. In short, researchers have responded to the expansion of Internet use among GBM by adopting the Internet as a tool to study them (Chiasson et al., 2006; Grov, Breslow, Newcomb, Rosenberger, & Bauermeister, 2014). This includes using the Internet to identify and enroll participants for facilitated assessments (Bauermeister, Carballo-Dieguez, Ventuneac, & Dolezal, 2009; Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2011; Grov, Agyemang, Ventuneac, & Breslow, 2013; Grov, Rendina, & Parsons, 2014; Hernandez-Romieu et al., 2014; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2015; Hirshfield, Remien, Humberstone, Walavalkar, & Chiasson, 2004; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2014; Mitchell & Petroll, 2013; Pachankis, Rendina, Ventuneac, Grov, & Parsons, 2014; Parsons, Vial, Starks, & Golub, 2013; Vial, Starks, & Parsons, 2014, 2015), identify and enroll participants for facilitated interventions (Adam et al., 2011; Khosropour, Johnson, Ricca, & Sullivan, 2013; Martinez et al., 2014; Parsons et al., 2013; Whiteley et al., 2012), conducting fully online studies (i.e. assessments and recruitment) (Adam et al., 2011; Bull, Lloyd, Rietmeijer, & McFarlane, 2004; Carpenter, Stoner, Mikko, Dhanak, & Parsons, 2009; Chiasson et al., 2005; Chiasson, Shuchat Shaw, Humberstone, Hirshfield, & Hartel, 2009; Christensen et al., 2013; Coleman et al., 2010; Gass, Hoff, Stephenson, & Sullivan, 2012; Greacen et al., 2013; Grov, Rendina, Breslow, et al., 2014; Grov, Rendina, Ventuneac, & Parsons, 2013; Grov, Rodriguez-Diaz, Ditmore, Restar, & Parsons, 2014; Hirshfield et al., 2010; Hirshfield, Grov, Parsons, Anderson, & Chiasson, 2015; Hirshfield et al., 2008; Holloway, Rice, et al., 2014; Jain & Ross, 2008; Marcus, Hickson, Weatherburn, & Schmidt, 2013; Matthews, Stephenson, & Sullivan, 2012; Mitchell & Petroll, 2012; Mustanski, Greene, Ryan, & Whitton, 2015; Mustanski, Rendina, Greene, Sullivan, & Parsons, 2014; Navejas, Neaigus, Torian, & Murrill, 2012; Oldenburg et al., 2015; Reece et al., 2010; Rendina, Breslow, et al., 2014; Rendina, Jimenez, Grov, Ventuneac, & Parsons, 2014; Rosenberg, Rothenberg, Kleinbaum, Stephenson, & Sullivan, 2013; Rosenmann & Safir, 2007; Rosser et al., 2009; Rosser et al., 2010; Sharma, Sullivan, & Khosropour, 2011; Siegler, Sullivan, Khosropour, & Rosenberg, 2013; Sineath et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2011; Wagenaar, Grabbe, Stephenson, Khosropour, & Sullivan, 2013; Wagenaar, Sullivan, & Stephenson, 2012; Wall, Stephenson, & Sullivan, 2013) as well as delivering interventions entirely online (Adam et al., 2011; Bowen, Horvath, & Williams, 2007; Bull et al., 2004; Carpenter et al., 2009; Chiasson et al., 2009; Christensen et al., 2013; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2015; Hirshfield et al., 2012; Kok, Harterink, Vriens, De Zwart, & Hospers, 2006; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2014; Mustanski et al., 2015; Rietmeijer & Shamos, 2007; Ybarra, DuBois, Parsons, Prescott, & Mustanski, 2014; Ybarra et al., in press; Young et al., 2014). This has afforded researchers the opportunity to identify and study GBM who may not live in urban centers or are otherwise geographically diverse (Chiasson et al., 2006; Grov, Breslow, et al., 2014), as well as opportunities to quickly enroll online samples at relatively low cost (Holland, Ritchie, & Du Bois, 2015) or to recruit for in person studies for less cost than field-based recruitment efforts (Parsons et al., 2013; Sanchez, Smith, Denson, Dinenno, & Lansky, 2012a; Vial et al., 2015)

For online recruitment, a number of researchers have enrolled geographically, racially, and ethnically diverse samples of GBM from across the U.S. using only social networking (e.g., Facebook, Myspace) and/or gay news/interest sites (e.g., gay.com, poz.com) (Adam et al., 2011; Chiasson et al., 2005; Christensen et al., 2013; Coleman et al., 2010; Gass et al., 2012; Hirshfield et al., 2015; Hirshfield et al., 2004; Hirshfield et al., 2008; Holloway, Dunlap, et al., 2014; Horvath, Beadnell, & Bowen, 2006; Jain & Ross, 2008; Khosropour & Sullivan, 2011; Matthews et al., 2012; Mitchell & Petroll, 2012; Mustanski et al., 2015; Navejas et al., 2012; Reece et al., 2010; Rosser et al., 2009; Sharma, Stephenson, White, & Sullivan, 2014; Sharma et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2011; Wagenaar et al., 2013; Wagenaar et al., 2012; Wall et al., 2013). Others have enrolled diverse samples across the U.S. identified, either entirely or at least in part, via partnerships with gay sexual networking (i.e., hook up) websites and mobile device applications (apps) (Bull et al., 2004; Burrell et al., 2012; Carpenter et al., 2009; Chiasson et al., 2009; Delaney, Kramer, Waller, Flanders, & Sullivan, 2014; Grov, Rendina, Breslow, et al., 2014; Grov, Rendina, et al., 2013; Grov, Rodriguez-Diaz, et al., 2014; Hirshfield et al., 2010; Khosropour et al., 2013; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2014; Oldenburg et al., 2015; Rendina, Breslow, et al., 2014; Rosenberg et al., 2013; Siegler et al., 2013; Sineath et al., 2013). In so doing, researchers have advertised on websites (via banner or pop-up ads), or partnered with website owners such that websites directly contacted their membership inviting them to participate in a study. The benefit of recruiting via hook-up websites and apps—particularly for HIV prevention and research—is that GBM can be engaged in research and interventions in the exact environments in which they are concurrently negotiating sexual encounters with potential partners (Grov, Breslow, et al., 2014; Pequegnat et al., 2007). These samples, however, are skewed toward men who are more sexually active and thus potentially riskier than GBM more generally (Parsons et al., 2013; Sanchez, Smith, Denson, DiNenno, & Lansky, 2012b). That is that recruiting men from sex sites may not benefit researchers seeking a more general gay sample (with varied, and especially lower, sexual risk). Additionally, for many exclusively online approaches to data collection—regardless of whether social or sexual networking websites were used—there is the opportunity for invalid submissions (e.g., duplicate entries, repeatedly changing responses to a screening survey until eligibility is confirmed) and the inability to verify participants’ identity and eligibility (Bauermeister, Pingel, et al., 2012; Grey et al., 2015; Konstan, Simon, Ross, Stanton, & Edwards, 2005; Teitcher et al., 2015).

Other researchers have used a combination of both face-to-face (e.g., in gay concentrated neighborhoods/venues) and social media to recruit for their studies (Bauermeister, Ventuneac, Pingel, & Parsons, 2012; Elford, Bolding, Davis, Sherr, & Hart, 2004; Fernandez et al., 2004; Hernandez-Romieu et al., 2014; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2015; Hirshfield et al., 2004; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2014; Mitchell & Petroll, 2013; Pachankis et al., 2014; Parsons et al., 2013; Raymond et al., 2010; Siegler et al., 2013; Vial et al., 2014, 2015; Ybarra et al., 2014; Ybarra et al., in press; Young, 2014; Young et al., 2014). Yet, studies have shown that samples recruited via the Internet versus venue-based sampling differ in terms of substance use and sexual behavior (Grov, Rendina, & Parsons, 2014; Hernandez-Romieu et al., 2014; Parsons et al., 2013; Raymond et al., 2010; Vial et al., 2014). In fact, a 2014 meta-analysis found that GBM recruited online (whether through sexually-oriented apps and website or not) report more HIV sexual risk behaviors than those recruited from other venues (Yang, Zhang, Dong, Jin, & Han, 2014). We know of only one study in which a sample of GBM participants were recruited first via random digit dialing—thus purporting U.S. national representativeness—and then subsequently enrolled in fully online studies (Herek, Norton, Allen, & Sims, 2010). In this study, those who did not have a computer or access to the Internet were provided with both as necessary. The larger panel consisted of over 40,000 households, of which 241 were gay men and 110 bisexual men.

In summary, it is becoming increasingly essential to study U.S. national samples of GBM more broadly—including GBM outside of urban centers—who are recruited via other sources than gay sexual networking websites or sexual networking apps (Chiasson, Hirshfield, & Rietmeijer, 2010; Chiasson et al., 2006; Grov, Breslow, et al., 2014). To overcome some of the aforementioned limitations, one approach to recruiting GBM for online assessment could be partnering with Internet marketing and polling entities in search of more representative samples of GBM from across the U.S. (Chang, 2009). This involves partnering with a consumer marketing research firm to recruit potential participants through their existing panel of respondents, while also ensuring that such panelists are representative of GBM more broadly (Voytek et al., 2012). However, research utilizing this approach has been limited for online research with GBM.

Researchers have established the feasibility and acceptability of enrolling and engaging large U.S. national samples of GBM, particularly to complete self-administered online assessments. Building upon this work, researchers have begun exploring ways to additionally engage GBM in at-home HIV testing, with much promise of feasibility and acceptability in spite of fairly limited data (Khosropour et al., 2013; Khosropour & Sullivan, 2011; Sharma et al., 2011). Khosropour et al. (2013) recruited MSM through banner advertisements on social networking and Internet-dating sites. Participants completed both online surveys and returned an at-home HIV test kit (finger stick, dried blood spot). In total, 1489 men were found eligible and consented, 895 (60%) completed the survey and were sent an at-home HIV test kit. Of these, 79% returned the at-home HIV test kit. In addition, 70% of those enrolled in their study remained prospectively for assessments 12 months later. Sharma et al., (2011) surveyed 6163 self-reported HIV-negative MSM via banner ads on MySpace.com and found 62% said they were very likely and an additional 20% being somewhat likely to take an at-home HIV test if offered as part of an online HIV prevention study. They also reported that odds of being willing to take an at-home HIV test nearly doubled when offering a modest incentive ($10) as compared with being offered nothing. For GBM, high acceptability and feasibility for self-sampling of rectal specimens for STI screening was found in a study conducted by Wayal et al. (2009). In a clinic setting, 334 men had rectal samples collected by a nurse, with 82% also providing a self-sampled rectal specimen with instructions, 14% were uncomfortable self-sampling and 4% found the test unacceptable. A majority of men were willing to self-sample at home, providing further support for at-home testing.

Meanwhile, less is known about the feasibility and acceptability of completing at-home self-administered urethral and rectal STI screening. In addition to the present study, at-home self-administered testing is currently being used in ongoing NIH-funded studies and thus data on feasibility and acceptability are forthcoming. Meanwhile, comparable research with (presumably mostly heterosexual) women and men has noted mixed results with the feasibility and acceptability of at-home STI testing. One study indicated strong acceptability for vaginal swabs to test for bacterial STIs (Gaydos et al., 2013). In their study, Gaydos et al. (2013) reported on women who requested at-home testing kits via the website iwantthekit.org—304 (17%) of 1747 women who used the kit indicated on their questionnaire that they had used the kit previously (i.e., return testers). Another study of adults in Sweden reported on online advertising for an at home urine collection kit to test for chlamydia. The website received 19,158 visits which resulted in 838 test requests among women (64.7% returned a sample), and 612 test requests among men (59.5% returned a sample) (Novak & Karlsson, 2006). A second Swedish study targeting young men aged 19–24 found a very low response rate (24%) for at-home chlamydia screening (Domeika, Oscarsson, Hallén, Hjelm, & Sylvan, 2007). For the present study, we present characteristics of the One Thousand Strong panel, an ongoing longitudinal study of GBM from across the U.S. recruited in partnership with a marketing firm, Community Marketing and Insights (CMI). We compared the One Thousand Strong panel to samples from other U.S. national online studies as well as compared participants who completed various enrollment milestones (with those who did not) to join our panel.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The One Thousand Strong panel is a longitudinal study prospectively following a U.S. national sample of GBM for a period of three years. Analyses for the present manuscript are based on our recruitment and enrollment data. Participants were identified via CMI panel of over 45,000 LGBT individuals, over 22,000 of whom are GBM throughout the U.S. Founded in 1992, and based California, CMI draws panelists from over 200 sources ranging from LGBT events to social media and email broadcasts distributed by LGBT organizations, and includes non-gay identified venues/mediums in order to maintain a robust and diverse panel of participants. CMI estimates that roughly 50% of their panelists are drawn from GLBT specific sources and 50% via mainstream social media sources that are not explicitly “gay” (e.g., Facebook and the like). Although a non-probability panel in-and-of itself, CMI is able to target individuals based on predetermined characteristics and invite them to participate in research studies. Our goal was to recruit a sample of GBM who represented the diversity and distribution of GBM at the U.S. population level. In so doing, we used data from the U.S. Census with regard to the distribution of same-sex households and racial ethnic composition by state to populate our recruitment parameters. That is, states with more same-sex households (e.g., California, New York) were weighted heaver in recruitment selection than states with fewer same-sex households (e.g., Wymong) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Through our partnership, CMI identified participants and briefly screen them for eligibility. Those deemed preliminarily eligible had their responses and contact information shared with the research team, and we then independently contacted and followed participants for full enrollment and longitudinal assessment.

To be preliminarily eligible for One Thousand Strong, participants had to reside in the U.S., be at least 18 years of age, be biologically male, identify as male, identify as gay or bisexual, report having sex with a man in the past year (e.g., oral, anal, mutual masturbation), self-identify as HIV-negative, be willing to complete at-home self-administered rapid HIV antibody testing (those testing positive at baseline were not included in the One Thousand Strong panel), be willing to complete self-administered testing for urethral and rectal chlamydia/gonorrhea, be able to complete assessments in English, have access to the Internet such to complete at-home online assessments, have access to a device that was capable of taking a digital photo (e.g., camera phone, digital camera), have an address to receive mail that was not a P.O. Box, and report residential stability (i.e., have not moved more than twice in the past 6 months). We excluded heterosexually identified MSM because the HIV prevention needs as well as interventions targeting these individuals would be vastly different from those targeting gay and bisexually identified men. For example, interventions for heterosexually identified MSM would need to include relevant components with regard to disclosure/concealment with female sex partners, disclosure/concealment of sexual behavior/identity more broadly, and the theoretical models used for HIV prevention among GBM might be obsolete (e.g., gay/bisexual resilience) (Herrick, Stall, Goldhammer, Egan, & Mayer, 2014). Participants were required to be sexually active in the past year; however, please note that we did not require men to report HIV risk behavior (i.e., condomless anal sex). Men needed a digital camera in order to take a picture of their at-home HIV test results and send them to us so results could be verified. We excluded those with only a P.O. Box because testing kits may not have been delivered, and we excluded those having moved more than twice in the past months (e.g., residential instability) to limit the number of participants lost during follow up data collection waves.

We staggered enrollment over a period of 6 months (April 2014–October 2014) such to maintain sufficient staffing resources to guide participants through the enrollment process (e.g., mailing HIV/STI testing kits, following up with participants). The City University of New York (CUNY) Institutional Review Board approved study procedures.

Recruitment Milestones

Participants had to pass three milestones in order to be considered fully enrolled in the One Thousand Strong panel and each milestone involved multiple steps.

Milestone 1

During the enrollment process, CMI first contacted potential participants (n = 9011) via email inviting them to join the study. All invited participants were over the age of 18, male, gay or bisexually identified, and had access to the Internet, and were specifically targeted with regard to location, age range, race, and ethnicity in order to reach out to a sample that was reflective of U.S. Census characteristics. Emails were tracked as opened, screener started, or bounced. Participants were told they would have to complete a brief (2 minute) online screener to determine if they met preliminary eligibility criteria (previously described). Those who met preliminary eligibility criteria were immediately asked to complete a 10-minute screening survey and were compensated with a $10 Amazon gift card. Following the screening survey, the One Thousand Strong study was described in its entirety along with an introduction video explaining the study objectives. Consent for CMI to share participant contact information with the research team was obtained. Preliminarily eligible participants who provided consent had their contact information shared with the research team and we then independently contacted participants to continue the enrollment procedures.

Milestone 2

Preliminarily eligible participants who completed Milestone 1 were sent an email by the research team to complete an at-home baseline CASI survey via Qualtrics survey software (qualtrics.com). The baseline CASI survey included a link to a welcome video that introduced the research staff and explained the survey procedures. The survey itself included questions on a range of topics including depression, substance use, HIV testing history, tobacco use, gay community attachment, and sexual behavior. Participants were able to stop/pause the survey and resume at their leisure. In the event they closed their browser window, the survey would resume where they left off when the link was clicked again. Of those who completed the baseline CASI, the median time to survey completion was 78 minutes, which includes any breaks taken by participants. Those who completed the baseline CASI were compensated with a $25 Amazon gift card.

Milestone 3

Upon completing the at-home baseline CASI survey, we mailed an at-home HIV and STI testing kit in a plain cardboard box to participants. The box contained an OraQuick© rapid HIV home testing kit, testing supplies (urine cup, anal swab, test tubes, barcodes to identify samples) to collect samples for urine and rectum testing of gonorrhea and chlamydia, an instructional brochure and a plain prepaid self-addressed return box mail the urine and rectum samples to the laboratory. We timed kit arrival to coincide with an email to participants. This email contained a link for participants to watch an instructional video on how to proceed with the testing kit as well as a brief (5 minute) survey to complete following testing procedures. The survey asked participants to provide feedback about the testing process, to self-report HIV test results, and upload a photo of the OraQuick© test paddle with visible HIV results for confirmation.

STI test results were disseminated to participants along with compensation of a $25 Amazon gift card for completing the testing. Those who tested positive for an STI were phoned to facilitate connecting them to treatment with a healthcare provider. Those who tested negative for STIs received an email with their results. When test results were inconclusive (3%, n = 38 of 1268), participants were contacted and one additional testing kit was sent for retesting. Preliminarily eligible participants were considered fully enrolled in the panel when they completed all components of the enrollment process and their HIV test results were negative. Project staff members were available to assist participants in all phases of the enrollment process and, as necessary, we reached out to participants (up to two email reminders, two text messages, and four phone calls over a one month period) to encourage timely completion of enrollment steps.

Measures

Measures used in this manuscript included variables collected at different points during the enrollment process (e.g., CMI screening survey vs. baseline CASI). These include demographic characteristics, alcohol and drug use and sexual behavior.

Demographic characteristics

During the CMI screening, participants reported demographic characteristics including race/ethnicity, education, income, age, sexual orientation, U.S. geographic region, HIV testing history, and whether they had health insurance and a primary care doctor.

Sexual behavior

During the CMI screening, participants reported number of male sex partners in the past 12 months. Sex could have included oral sex, anal sex and/or mutual masturbation. During the baseline CASI, participants were asked whether they currently had primary and casual sexual partners in the past 3 months and number of condomless anal sexual acts (CAS) with their partners. Sexual risk was determined as having CAS with any casual male partner or a male main partner whose status was HIV-positive or unknown.

Accessing LGBT resources

During the CMI screening, participants responded to the stem question, “In the last 6 months, how often did you visit a nearby…” with six follow ups—“LGBT community center,” “LGBT ‘friendly’ healthcare provider or facility,” “Gay/LGBT bar or club,” “Gay/LGBT coffee shop or bookstore,” “LGBT ‘friendly’ place of worship,” and “Any other type of LGBT ‘friendly’ space (like an ongoing club/meeting/group).” Response options were “Never,” “Once or twice,” “Three to five times,” “Six to 10 times,” and “More than 10 times.” We computed a mean score for these items (Range, 1 to 5), α = .65. These items were generated after consultation with experts in LGBT health and were used as an indicator of use of LGBT-affirming resources.

Analytic Plan

First we describe univariate characteristics of the One Thousand Strong panel relative to other large scale and U.S. national studies of GBM. Other studies included for comparative purposes were selected based on their being large-scale U.S. national samples of GBM; however, we excluded studies that included only HIV-positive men, had limited sampling with regard to racial and ethnic composition (e.g., 100% Latino men), as well as studies that were, for example, limited to subset populations like male escorts, substance users, or leather/S&M communities. Ten studies met our inclusion criteria. The Men’s National Sex Study (MNNS) (Rosenberger et al., 2011), the Online Sex and Love Study version 1.0 (Grov, Rendina, Breslow, et al., 2014; Grov, Rendina, et al., 2013; Rendina, Breslow, et al., 2014), the Men’s INTernet Sex Study (MINTS-II) (Coleman et al., 2010; Rosser et al., 2009), the Last Sexual Encounter Study (Chiasson et al., 2007), the 9/11 Study (Chiasson et al., 2005; Hirshfield et al., 2004), the Viagra, Drug Use, and HIV Transmission in Men study (Hirshfield et al., 2010), the Novel Internet-based Interventions for MSM (Hirshfield et al., 2012), the Barriers to Online Prevention (BORP) (Sharma et al., 2011), the Internet-based HIV Knowledge Assessment (Khosropour et al., 2013), and the Knowledge Networks study of GBM (Herek et al., 2010). In addition, and for comparative purposes, we also included the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) (Wagenaar et al., 2012), which is a CDC surveillance study of MSM from 21 metropolitan cities in the U.S. Finally, we also included the Urban Men’s Health Study (UMHS) (Catania et al., 2001; Wall et al., 2013). Although not a sample from across the U.S. and nearly two decades old, the UMHS was, for a time, considered a gold standard probability study of MSM because participants were identified using random-digit dialing in four U.S. cities that contained large LGBT populations (Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York). Where appropriate, we used chi-square and t-tests to compare our data to those of others.

Next, we compared demographic characteristics of those who responded to the CMI invitation versus those who did not. We then compared participants who completed various enrollment milestones with those who did not. For Milestone 1, those who were eligible and consented vs. not were compared using CMI screening data. For Milestone 2, those who completed at-home baseline CASI vs. not were compared using CMI screening data. For Milestone 3, those who completed at-home HIV/STI testing and enrolled in the panel vs. not were compared using at-home CASI data and CMI screening data. Descriptive statistics were examined using Pearson’s chi-squared analyses for categorical variables, t-test for age and number of male partners. Cramer’s V and Cohen’s d were calculated as indicators of effect sizes.

Finally, we performed a logistic regression to determine independent variables that were associated with completing Milestone 3 (i.e., at-home HIV and STI testing). Variables selected for the model were those that were significant at the bivariate level p < .05.

Results

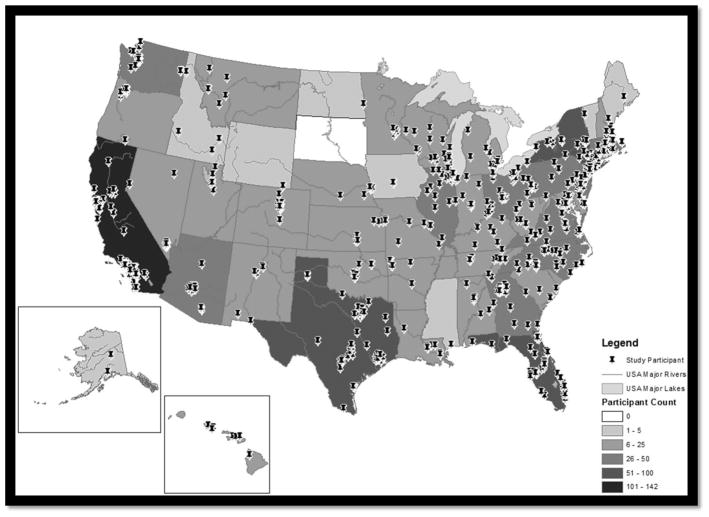

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics of the One Thousand Strong panel as well as those of other large-scale U.S. studies of MSM (previously named). Figure 1 is a map of the US with pins indicating where participants resided. Participants in One Thousand Strong represented 49 of 50 states (no participants from South Dakota were enrolled), 95% self-identified as gay (which was significantly higher than 10 other studies [all p < .05], two studies did not report sexual identity). Of the 54 bisexual men who joined the study, 35 (64.8%) reported sex with women in the past year—all reported sex with men per enrollment criteria. In total, 29% of participants in the One Thousand Strong panel were men of color which, was significantly greater than 6 of the 12 other studies (p < .05)—UMHS; MNNS; Last Sexual Encounter Study; Viagra, Drug use and HIV transmission in Men; and Novel Internet-based Interventions for MSM. The five remaining studies had a significantly greater proportion of men of color than the One Thousand Strong panel. Participants in One Thousand Strong were an average age of 40.2, which was significantly higher than the 4 other studies that reported mean age—MNNS; Online Sex and Love Study version 1.0; MINTS-II; and BORP. Four studies did not report age and three studies only reported median age, which was insufficient to perform a statistical comparison. Participants in One Thousand Strong did not significantly differ in age from those in the Knowledge Network study of GBM—a U.S. representative sample recruited using random digit dialing (p > .05). The duration of the One Thousand Strong baseline assessment was longer than most of the other studies, though compensation was also higher.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the One Thousand Strong panel and other large scale U.S. studies of men who have sex with men

| One Thousand Strong | Urban Mens’ Health Study (UMHS) |

National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) |

Men’s National Sex Study (MNSS) |

Online Sex and Love Study version 1.0 |

Men’s INTernet Sex

Study (MINTS-II) |

Last Sexual Encounter Study |

9/11 Study | Viagra, Drugs Use, and HIV Transmission in Men |

Novel Internet-based Interventions for MSM |

Barriers to Online Prevention (BORP) |

Internet-based HIV Knowledge Assessment |

Knowledge Networks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Year(s) data collected | 2014 | 1996–1998 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2005 | 2003–2004 | 2002 | 2004 – 2005 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2005 |

| Final sample size | 1,071 | 2,881 | 8,175 | 24,787 | 2,063 | 2,716 | 2,964 | 2,916 | 7,001 | 3,092 | 6,163 | 710 | N = 662, n = 351 were GBM |

| Geographic dispersion | 49 of 50 states in the U.S. (missing South Dakota) | Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco | 21 metropolitan cities in the U.S. | All U.S. and the District of Columbia | 49 of 50 states in the U.S. (missing New Hampshire) and Puerto Rico | U.S. Resident | United States and Canada | United States, less than 1% in Guam and Puerto Rico. | Participants resided in every state in the U.S., Canadian territory, or Canadian providance | All 50 states in the U.S. | All 50 states in the U.S. | United States | United States |

| Recruitment methodology | Community Marketing & Insights’ national panel of LGBT U.S. Adults. Targets based on Census data of U.S. same-sex household distribution | Random Digit Dial | Time-Location Sampling in bars and gay venues | E-mail blast using MSM sexual networking (profile-based) website | Banner on a MSM sexual networking (profile-based) website | Banners online - Gay.com | Banner ads on 14 gay-oriented websites. | Banner in U.S. adult chat rooms on gay oriented site. | Banners on via 8 gay-oriented websites, ranging from sexual networking and chat to news sites | Banner ads on 4 gay-oriented sexual networking websites. Plus an e-mail blast via one web site. | Banners online-MySpace.com | Facebook.com, Myspace.com, BlackGayChat.com, Adam4Adam.com | Knowledge Networds panel. Probbality sample of U.S. residents recruited through random digit dial. |

| Response rate | 9,011 emailed, 2,393 responded, 1,375 eligible, 1,268 completed survey, 1,071 enrolled | 95,000 calls made, 3,700 completed survey, 2,881 enrolled | 11,074 eilgible, 10,678 completed survey, 8,175 enrolled | 169,136 emailed, 32,831 responded, 24,787 enrolled | 10,900 clicked banner, 3,334 began survey, 2,063 enrolled | 52,629 clicked banner, 3,035 completed survey, 2,716 enrolled | 6,122 clicked banner, 2,964 completed survey and were eligable | 5,981 clicked banner, 3,697 completed survey, 2,916 enrolled | 19,253 clicked banner, 11,329 completed full survey, 7,001 enrolled | 609,960 e-mails sent, 23,213 clicked link, 13,674 consented, 11,798 completed baseline survey, 3,092 randomized | 30,559 clicks, 9005 consented, 6,163 enrolled | 25,809 clicks, 6,174 eligible, 3,474 consented, 710 enrolled | 902 self-identified LGB individuals e-mailed. 775 accessed questionaire, 662 enrolled, 351 GBM |

| Compensation | $25 for completing CASI, $25 HIV/STI testing (amazon.com gift card) | NR | $20–$30 cash or gift certificate | No incentive | No incentive | $10 | No incentive | No incentive | No incentive | No incentive | No Incentive | $15 for baseline survey, $20 after completing at-home HIV test | NR |

| HIV testing | Yes | Random selection of self reported HIV-seropositive, n = 74 | offered, not required | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Qualitative interview | Yes, n = 80 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Computer-assisted survey | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| STI testing | Uretheral and rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Self-identified Sexuality (%) | n = 351 | ||||||||||||

| Gay | 95.0 | 84.0 | 80.0 | 79.9 | 77.7 | 64.7 | NR | NR | 89.0 | 95.0 (male partners only) | 73% | 84.90% | 68.80% |

| Bisexual | 5.0 | 9.0 | 19.0 | 20.1 | 20.0 | 34.9 | NR | NR | 10.0 | 4.0% (male and female partners) | 24% | 12.40% | 31.20% |

| Other MSM | 0.0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.3 | NR | NR | 1.0 | 1.0 (male and transgender partners) | 3 | 2.70% | 0 |

| Aproximate duration of baseline assessment | 60 minutes + 20 for HIV/STI testing | 75 minutes | 30 minutes | 20 minutes | 10 minutes | 45 minutes | 10–15 Minutes | 10 minutes | 10–15 minutes | 10 – 15 minutes | NR | 60 minutes | NR |

| Sexual activity w/men required? | Yes, in the last year | Yes, since age 14 | Yes, in the last 12 months | Yes, last sexual event must have been with a man | Yes, in last 90 days | Yes, in lifetime | In lifetime | No | Yes, in last year | Yes, currently sexually active. | Yes- in last year | Yes- in last year | No |

| Race and ethnicity (%)a | |||||||||||||

| White | 71.2 | 79.0 | 44.0 | 84.6 | 60.7 | 26.8 | 80.0 | 85.0 | 81.0 | 81.0 | 43.0 | 66.2 | 61.8 |

| Black | 7.7 | 4.0 | 24.0 | 3.6 | 15.4 | 16.4 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 13.0 | 14.9 | 19 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 12.6 | 10.0 | 24.0 | 6.4 | 11.1 | 25.2 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 31.0 | 18.9 | 14.2 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4.6 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 18.9 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0 | |

| Native American | 0.6 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0 | |

| Other | 3.3 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 12.6 | 12.8 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 5 | |

| Mean age | 40.2 | NR | NR | 39.2 | 36.2 | 29 | Median = 36 | NR | Median = 38 | Median = 39 | 24 | NR | 45 |

| Age Range | 18–81 | 18–80 and up | 18 and up | 18–87 | 18 and up | 18–50+ | 18–85 | 18–60+ | 18 – 85 | 18–81 | 18–40+ | 18–54 | 18–89 |

| HIV-Positive (%) | 0.0 | 17.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 28.1 | 4.4 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 14.0 | 17.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NR |

| Relationship status (%) | |||||||||||||

| Single | 54.1 | 51.0 | NR | 61.9 | 31.4 | NR | 57.0 | NR | 70.0 | NR | NR | NR | 50.4 |

| In relationship | 45.9 | 49.0 | 38.1 | 68.6 | NR | 43.0 | NR | 30.0 | NR | NR | NR | 49.6 | |

NR: Not Reported

Some values reported as zero may be because participants were collapsed into the “other” racial/ethnic group

Figure 1.

Distribution of One Thousand Strong participants across the United States

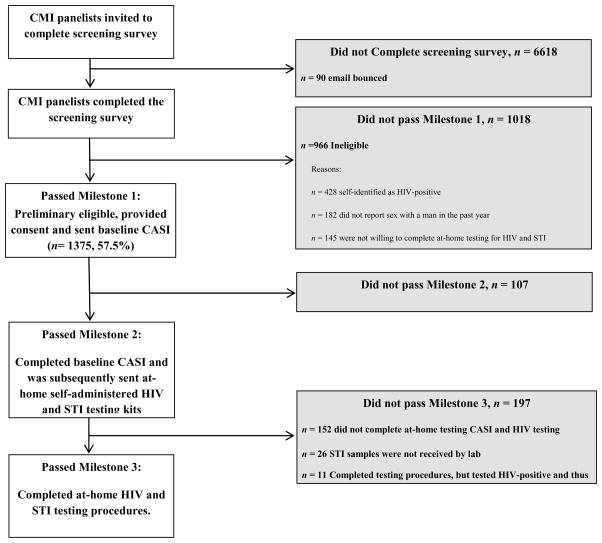

Figure 2 shows data on enrollment milestones throughout the recruitment process. In total, 9,011 individuals received an email inviting them to join the study. Of these, 73.5% did not complete the screening survey (1.4% of these emails bounced, 96.3% of these men did not open the email, and 2.4% opened the email but did not start the screening survey). We compared demographic characteristics of those who responded to the CMI-administered screener and those who did not. In all instances in which significance was observed (i.e., p < .05), we found that the effect size (i.e., Cramer’s V) was small. A higher proportion of those aged 45 or higher responded compared with those in younger age groups, χ2(6) = 39.69, p < 0.001, V = 0.07. A greater proportion of White participants (31.0%) than Black (20.9%), Latino (17.9%), and those of other races (23.6%) responded, χ2(3) = 129.49, p < 0.001, V = 0.12. A significantly larger proportion of gay men (27.1%) responded than bisexual men (22.2%) and other men who have sex with men (4.8%), χ2(2) = 24.21, p < 0.001, V = 0.05. A greater proportion of those with incomes above $100,000 per year (31.8%) responded than those with incomes below $50,000 per year (24.5%), χ2(2) = 30.89, p < 0.001, V = 0.06. Region of the country was not associated with responding to the invitation, χ2(3) = 4.28, p = 0.23, V = 0.02.

Figure 2.

Enrollment of the One Thousand Strong panel

Everyone (100%, n = 2393) who started the initial 2-minute screening survey completed it and was linked to the longer 10-minute survey that assessed full study eligibility criteria. Of those completing the 10-minute survey, 42.5% (n = 966) were ineligible. Reasons for ineligibility are shown in Figure 1, with the most common being self-reported HIV-positive serostatus (44.3% of ineligible participants, n = 428), not having engaged in sex with a male in the past 12 months (18.8% of ineligible participants, n = 182), and unwillingness to complete at-home testing for HIV and STIs (15.0% of ineligible participants, n = 145). In addition, 52 (5.1%) were not interested in the full study or did not consent to continue. Meanwhile, 57.5% (n = 1375) were eligible and provided consent for their contact information to be shared with the research team (i.e., they passed Milestone 1).

Of the 1375 who passed Milestone 1, 92.2% (n = 1268) passed Milestone 2, meaning they completed an hour-long at-home CASI after being independently contacted by the research team. These participants were then sent an at-home HIV and STI testing kit as part of the steps involved to pass Milestone 3. Of the 1268 that were sent testing kits, 84.5% (n = 1071) completed all testing procedures and were subsequently enrolled into the panel. Eleven (0.9%) additional men completed all testing procedures but tested positive for HIV and were thus determined to be ineligible and not enrolled in the panel. Those who tested HIV-positive were phoned to discuss available resources and options for obtaining HIV confirmatory testing with a healthcare provider. Three pairs of men in the sample were known to be cohabiting couples and were retained.

We compared characteristics of participants across recruitment milestones (see Table 2). Compared to men who were not eligible, a significantly larger proportion of those who were eligible and consented to join from the CMI screener (i.e., passed Milestone 1) were White. This appeared to be largely a result of known racial and ethnic disparities in HIV prevalence (CDC, 2015a). In total, 62.4% of Black men and 52.1% of Latino men who were ineligible were deemed so because they self-reported being HIV-positive, compared with only 42.4% of ineligible White men (see Table 3). Men who were eligible and consented were also younger on average; however there were no significant differences with regard to the number of male partners in the previous 12 months or sexual identity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Enrollment milestones

| Milestone 1 | Milestone 2 | Milestone 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study eligible and consented to join from CMI screener | Completed at-home baseline CASI | Completed at-home HIV/STI testing3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||||||||

| n = 1018 | n = 1375 | n = 107 | n = 1268 | n =186 | n = 1071 | ||||||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | V | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | V | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | V | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Black or African American | 141 | 13.9 | 120 | 8.7 | 17.07 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 15 | 14.0 | 105 | 8.3 | 6.91 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 18 | 9.7 | 83 | 7.7 | 4.07 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| Latino | 142 | 13.9 | 181 | 13.2 | 18 | 16.8 | 163 | 12.9 | 26 | 14.0 | 135 | 12.6 | |||||||||

| White | 649 | 63.8 | 951 | 69.2 | 63 | 58.9 | 888 | 70.0 | 120 | 64.5 | 763 | 71.2 | |||||||||

| Mulitracial/Other | 86 | 8.4 | 123 | 8.9 | 11 | 10.3 | 112 | 8.8 | 22 | 11.8 | 90 | 8.4 | |||||||||

| Sexual Orientation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Gay | 941 | 94.0 | 1298 | 94.4 | 1.66 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 103 | 96.3 | 1195 | 94.2 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 167 | 89.9 | 1017 | 95.0 | 7.75 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Bisexual | 60 | 6.0 | 77 | 5.6 | 4 | 3.7 | 73 | 5.8 | 19 | 10.2 | 54 | 5.0 | |||||||||

| Region in the US | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Northeast | NA1 | 17 | 15.9 | 244 | 19.2 | 1.04 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 39 | 21.0 | 204 | 19.0 | 13.9 | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Midwest | 23 | 21.5 | 244 | 19.3 | 51 | 27.4 | 192 | 17.9 | |||||||||||||

| South | 37 | 34.6 | 430 | 34.3 | 49 | 24.7 | 377 | 35.2 | |||||||||||||

| West | 30 | 28.0 | 348 | 27.4 | 46 | 24.7 | 297 | 27.7 | |||||||||||||

| US Territories/Possessions | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | |||||||||||||

| Health Insurance | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | NA1 | 88 | 82.2 | 1155 | 91.1 | 10.4 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 166 | 89.2 | 978 | 91.3 | 2.13 | 0.35 | 0.04 | ||||||

| No | 19 | 17.8 | 108 | 8.5 | 20 | 10.8 | 88 | 8.2 | |||||||||||||

| Don’t Know | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.5 | |||||||||||||

| Primary care doctor | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | NA1 | 71 | 66.4 | 951 | 75.0 | 3.87 | 0.049 | 0.05 | 130 | 69.9 | 814 | 76.0 | 3.17 | 0.08 | 0.05 | ||||||

| No | 36 | 33.6 | 317 | 25.0 | 56 | 30.1 | 257 | 24.0 | |||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| High School Diploma, GED, or less | NA2 | NA2 | 16 | 8.6 | 77 | 7.2 | 12.5 | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||||||||||

| Some College, Associates Degree | 92 | 49.5 | 397 | 37.1 | |||||||||||||||||

| College Degree | 43 | 23.1 | 313 | 29.2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Graduate School | 35 | 18.8 | 284 | 26.5 | |||||||||||||||||

| Income | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Less than $20K | NA2 | NA2 | 35 | 18.8 | 213 | 19.9 | 0.37 | 0.83 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| $20K to $49,999 | 67 | 36.0 | 362 | 33.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| $50K or more | 84 | 45.2 | 496 | 46.3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Anal sex without a condom a casual male partner, or with a main male partner who was HIV+ or of uknown status < 90 days | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | NA2 | NA2 | 71 | 38.4 | 420 | 39.2 | 0.07 | 0.79 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| No | 115 | 61.6 | 651 | 60.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| HIV Testing History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Past year | NA2 | NA2 | 97 | 52.4 | 659 | 61.5 | 6.6 | 0.04 | 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| More than 1 year ago | 71 | 38.4 | 350 | 32.7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Never | 17 | 9.2 | 62 | 5.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | d | M | SD | M | SD | t | p | d | M | SD | M | SD | t | p | d | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 45.1 | 13.4 | 40.5 | 13.9 | 8.22 | <.001 | 33.7 | 42.3 | 14.3 | 40.3 | 13.9 | 1.41 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 41.3 | 14.1 | 40.2 | 13.8 | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.08 |

| # male partners (< 12 months) | 7.2 | 15.0 | 7.9 | 13.2 | −1.2 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 6.0 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 13.5 | −1.6 | 0.11 | 18.5 | 5.8 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 14.3 | −2.5 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

NA1 Not able to make comparison because item was assessed in screening survey after participant met study criteria

NA2 Not able to make comparison because item was assessed at baseline CASI

11 additional men completed all steps, however, were found to be HIV-positive as a result of HIV testing, and thus not enrolled in the panel. These men are excluded from these analyses

V = Cramer’s V, d = Cohen’s d

Table 3.

Racial and ethnic differences in reasons for study ineligiblity on the CMI screener

| Black | Latino | White | Multiracial | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | V | |

| Self-reported HIV-positive | |||||||||||

| * HIV positive | 88 | 62.4 | 74 | 52.1 | 275 | 42.4 | 31 | 36 | 24.29 | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| HIV negative/unknown status | 53 | 37.6 | 68 | 47.9 | 374 | 57.6 | 55 | 64 | |||

| Not willing to complete at-home testing | |||||||||||

| * Not Willing | 28 | 19.9 | 30 | 21.1 | 148 | 22.2 | 16 | 18.6 | 1.25 | 0.74 | 0.04 |

| Willing | 113 | 80.1 | 112 | 78.9 | 501 | 77.2 | 70 | 81.4 | |||

| Residentially Unstable | |||||||||||

| * Yes | 19 | 13.5 | 28 | 19.7 | 80 | 12.3 | 19 | 22.1 | 9.78 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| No | 122 | 86.5 | 114 | 80.3 | 569 | 87.7 | 67 | 77.9 | |||

| Access to a digital camera | |||||||||||

| Yes | 127 | 90.1 | 130 | 91.5 | 588 | 90.6 | 76 | 88.4 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.03 |

| * No | 14 | 9.9 | 12 | 8.5 | 61 | 9.4 | 10 | 11.6 | |||

| Report sex with a man in past year | |||||||||||

| Yes | 116 | 82.3 | 122 | 85.9 | 520 | 80.1 | 71 | 82.6 | 2.76 | 0.43 | 0.05 |

| * No | 25 | 17.7 | 20 | 14.1 | 129 | 19.9 | 15 | 17.4 | |||

| Not interested, did not consent | |||||||||||

| * Yes | 3 | 2.1 | 4 | 2.8 | 40 | 6.2 | 5 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| No | 138 | 97.9 | 138 | 97.2 | 609 | 93.8 | 81 | 94.2 | |||

| Other- PO Box, not male, no surveys, not gay/bisexual/queer identified | |||||||||||

| * Yes | 14 | 9.9 | 7 | 4.9 | 50 | 7.7 | 6 | 7 | 2.6 | 0.46 | 0.05 |

| No | 127 | 90.1 | 135 | 95.1 | 599 | 92.3 | 80 | 93 | |||

Ineligible

V = Cramer’s V

Note: Categories are not mutually exclusive. Participants could be deemed ineligible for more than one reason

Compared to those completing Milestone 2 (i.e., at-home baseline CASI), those who completed Milestone 1 but not Milestone 2 were less likely to have health insurance and less likely to have a primary care physician. There were no differences in sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, U.S. region, age, average number of male partners in the past 12 months, or having accessed LGBT-affirming resources in the prior 6 months.

Of the 1268 participants completing at-home baseline CASI (i.e., passed Milestone 2), 84.5% completed the at-home HIV and STI testing procedures and enrolled in the panel (i.e., passed Milestone 3). Among the 1071 enrolled in the panel, 2.8% (n = 30) experienced an STI sampling error (e.g., fecal contamination of the rectal swab, urine vial improperly sealed and came open during transit to the lab, rectal swab inserted into the vial containing urine), < 1% (n = 2) had an HIV inconclusive result because the photo was unclear/blurry, < 1% (n = 10) did not upload a photo or lost the photo, and < 1% (n = 8) had to be resent a kit because it was reported as lost in the mail. In all instances, attempts to resample were successful.

Compared to those completing milestone 3, those completing milestone 2 but not 3 reported less education, were more likely to identify as bisexual (as opposed to gay), more likely to live in the Midwest, had fewer male partners in the past year, and were less likely to have tested for HIV in the past year. Among bisexual men who were sent at-home testing kits (n = 73), those who did not complete testing (n = 19) were more likely to be currently married to a woman than those who completed testing (37% vs. 13%, p = .02). In contrast to those passing milestone 2, there was no association between health insurance status or having a primary care physician and passing milestone 3. In addition, there were no differences in race and ethnicity, income, reported sex without a condom with a male partner who was HIV-positive or of unknown HIV status in the last 90 days, age, and having accessed LGBT-affirming resources in the prior 6 months.

Finally, we performed a logistic regression to determine independent variables that were associated with completing Milestone 3 (i.e., at-home HIV and STI testing) versus those who only completed milestone 2. Variables selected for the model were those that were significant at the bivariate level (p < .05). In this model, a higher number of male sex partners in the last year (AOR = 1.02, 95%CI[1.00,1.04]), having a college education (yes vs. no, AOR = 1.71, 95%CI[1.24, 2.35]), residing in the southern region of the U.S. (yes vs. no, AOR = 1.61, 95%CI[1.13, 2.30]), and being gay identified (yes vs. no, AOR = 2.19, 95%CI[1.25, 3.82]) were independently associated with completing Milestone 3. Having tested for HIV in the last year (yes vs. no, AOR = 1.31, 95%CI[0.95, 1.81]) was not significantly associated in this model.

Discussion

The purpose of this manuscript was to describe the enrollment procedures for the One Thousand Strong panel, present characteristics of this panel relative to other large U.S. national studies of MSM, and determine if demographic and behavioral characteristics were associated with passing enrollment milestones. The One Thousand Strong panel makes a strong contribution to the field, given its national reach, its broad focus on GBM (including those who did not necessarily report recent HIV risk behavior), and its inclusion of survey and biological methodologies. Given that most studies on GBM utilize convenience samples, the enrollment of a national sample provides plentiful opportunities for improving our understanding of GBM health. The national sample enrolled in the One Thousand Strong panel, which included men from 49 out of the 50 states, will increase generalizability of research on GBM to those who have been underrepresented in research (e.g., those outside of urban epicenters, those who do not report risk behavior). Additionally, the inclusion of biological assays is an important methodological contribution in that it demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of incorporating self-administered HIV/STI testing into otherwise online studies. It will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of GBM health, including an integration of psychosocial, behavioral, and biological factors.

One benefit of online studies is their ability to reach large amounts of geographically diverse participants (Chiasson et al., 2006; Grov, Breslow, et al., 2014). Many previous U.S. national online studies have involved completing self-report surveys assessments and our study found that a large number of individuals (94%) were willing to complete additional at-home self-administered testing for HIV and STIs (i.e., of the 2393 who completed the CMI screening, only 145 were deemed initially ineligible because they were unwilling to complete at-home testing). Additionally, 85% of men who we sent kits by mail completed all testing procedures with minimum errors. This suggests very high feasibility and acceptability of incorporating biological assessments into studies that are otherwise fully online, and demonstrates rates slightly higher than another national study of MSM in which 79% returned biological samples in the form of self-collected dried blood spots for HIV testing (Khosropour et al., 2013).

That being said—compared to men who did not pass Milestone 3—in a logistic regression, those passing Milestone 3 (i.e., HIV and STI testing) had more education, were more likely to be from the South, reported a greater number of male sex partners in the past year, and were more likely to be gay identified (as opposed to bisexual). It may be that men with more education were able to navigate some of the complexities regarding at-home self-administered testing. For One Thousand Strong, we provided participants with written instructions, a link to an instructional video, our email address, and our phone number to call if they had questions. We believe these efforts enhanced retention, but clearly our findings highlight there may have been additional barriers for men with less education. To further enhance retention, researchers might consider using live video feeds (camera-to-camera) to assist those who need additional help with the testing process. Our findings also highlight the need to monitor regional differences in the enrollment process. Should researchers begin to observe differential regional enrollment, researchers might consider reaching out to participants who failed to pass milestones to gather qualitative data on why they decided to withdraw.

On the surface, it makes sense that having a greater number of partners would be associated with participating in free HIV and STI testing because each sex partner increases the risk HIV and STI exposure. Whereas men who did not engage in sex with several male partners may have felt this step was unnecessary and perhaps they perceived these study components to be irrelevant. To retain these men, researchers might consider emphasizing to participants that their data are of value even if the participants themselves do not feel their responses are interesting enough to warrant inclusion.

Interestingly, not having a primary care provider and not having health insurance were associated with failure to pass milestone two (i.e., at-home CASI) but not milestone 3 (HIV and STI testing). The later finding suggests men who may not be well engaged in regular health care (i.e., lack insurance or a provider) are equally willing to complete at-home HIV and STI testing; however, this is only among men who were otherwise willing to participate in a health research study.

In other online studies, there appears to be a wide range of diversity with regard to demographic characteristics such as race and ethnicity, age, relationships status, and sexual identity. Participants in the One Thousand Strong panel appear to be similarly diverse with respect to most demographic characteristics with the exception of sexual orientation. Ninety-five percent of men in the One Thousand Strong panel self-identified as gay, which is higher than other large-scale studies of gay and bisexual men. In our study, sexual identity was associated with enrollment milestones such that, compared to gay men, bisexual men were less likely to complete at-home self-administered HIV and STI testing after previously expressing interest. Certainly, the vast majority (74%, 54 of 73) of bisexual men who received their kits completed the testing, but our findings suggest additional engagement with bisexually identified men may be necessary for researchers seeking to incorporate HIV and STI testing in their online studies. Specifically, it appears that among bisexual men kit return was negatively associated with being married to a woman. It could be that these men were not out to their wives about being bisexual or being sexually active with another male in the past 12 months, and thus more discrete means of testing these individuals should be considered. Researchers might also consider adding measures that would be of specific relevance to bisexual mens’ lived experiences would increase their interest and engagement in research studies. It bears mentioning that although our study did not have an enrollment criterion of recent sexual risk behavior, we did require participants to report sexual behavior with another male in the prior 12 months. In our study bisexual men were not significantly less likely than gay men to have reported sex with another man in the past year, and thus potentially excluded per eligibility criteria. Were researchers to use a narrower recall window (e.g., past 3 months), they may inadvertently exclude bisexual men who are sexually active with other men; however, have not done so recently. Further, one might expect that men who are less involved with the LGBT community might also be less likely to commit to a study such as ours. We found that having accessed LGBT-affirming resources in the last 6 months was not associated with passing enrollment milestone. We recognize, however, that our measure was imperfect and perhaps a scale measuring, for example, perceived attachment to the LGBT community would have been useful.

We also wish to highlight the role that race and ethnicity played in recruiting for this study. In the U.S., White men outnumber Black and Latino men (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015), and this pattern was observed in our sample. However, and although the effect size was small, men of color were less likely to respond to the initial CMI invitation. This invitation did not include any images in it; however, previous researchers have found responses from GBM of color depended upon the race of the model in the advertisement. Black GBM were more likely to click on advertisements featuring a Black model vs. a White model, and Hispanics were more likely to click on an advertisement with an Asian model vs. a White model (Sullivan et al., 2011). The inclusion of tailored images as part of the initial invitation might have improved the response rate. Second, and compared to other racial and ethnic groups, a significantly greater number of Black and Latino men were found to be ineligible for the study because they self-disclosed being HIV-positive (i.e., Milestone 1). This appeared to be largely as a result of known racial disparities in HIV prevalence (CDC, 2014). Second, and although not statistically significant, it appears that men of color trended toward lower completion of the at-home CASI (i.e., Milestone 2). Similar drop off rates have been found in other Internet studies with GBM (Jain & Ross, 2008; Khosropour & Sullivan, 2011; Sullivan et al., 2011; Whiteley et al., 2012; Young, 2014). Meanwhile, race and ethnicity was not associated with completing at-home self-administered STI and HIV testing (Milestone 3). Researchers wanting to study HIV-negative GBM who are representative of the underlying population should expect lower racial and ethnic diversity because of the disproportionate burden of HIV among communities of color. This is particularly relevant given the need to target HIV prevention resources to the populations disproportionally affected (i.e., MSM of color, younger MSM, economically disadvantaged MSM). The introduction of stratified sampling or sample weights allows researchers to target disaffected communities, however this also subsequently overestimates the proportion of men of color among HIV-negative GBM, which may need to be avoided. Likewise, researchers wanting to study HIV-positive GBM who are representative of the underlying population should expect higher racial and ethnic diversity for the aforementioned reasons. In all, it comes down to the questions researchers are seeking to answer as well as the target population they seek to answer it with.

Limitations

In recruiting the present sample, we did not attempt to represent GBM at high risk for HIV infection, but rather tried to approximate the distribution of sexually active, HIV-negative GBM, a fraction of whom may be at risk for HIV. Thus, the strengths of our study should be understood in light of their limitations. MSM who did not identify as gay or bisexual were excluded (n = 15) and thus our study cannot attest to the experiences of individuals who use other labels to describe their sexuality (e.g., pansexual, heterosexual MSM, queer). Next, although our sample is large enough for robust statistical analyses, it is considerably smaller than some other online studies which have managed to survey several thousand individuals; however, only cross-sectional and only with a CASI survey (i.e., biological measures not included) thus involving considerably fewer resources. Although we used parameters taken from the U.S. Census to establish our recruitment targets (specifically around geographic distribution of same-sex male couples across the U.S., as well as age, race and ethnicity), this was based on data on same-sex households (i.e., couples). The U.S. Census does not currently collect data on sexual identity or sexual behavior, thus the true prevalence and distribution of GBM across the U.S.—particularly single and dating GBM—remains unknown. As the only survey of the entire U.S. population, it is becoming increasingly essential for the Census to measure sexual identity in addition to same-sex households. Valid estimates of the number of LGBT individuals overall and by demographic characteristics are necessary both for research as well as for those seeking to develop LGBT affirming and inclusive policies. Because the population characteristics are unknown, it is not possible to weight our sample to the population. Although useful, CDC surveillance data also does not approximate the population. In essence, adding sample weights to match our dataset to CDC surveillance data—or any other dataset for that matter—simply corrects for our sample to match another sample, not to a population.

A large number of individuals received email messages inviting them to participate but did not opt in for the study. CMI was able to track whether an email was opened based on whether content from that email was downloaded onto a person’s computer or device. For our study, this means there may be instances in which we believe a person did not open the email, but in fact they did (message opened, but full content not downloaded). We also do not know how many of our emails that are listed as unread were never seen by panelists because it was pushed to their spam box. Our unread message rate was consistent with what other researchers using CMI’s LGBT panel have documented (Voytek et al., 2012). In addition, although a large number of individuals did not respond to the initial email invitation, the “click through” rate for our study was considerably higher than studies that use banner ads. Researchers choosing to enroll participants via banner ads versus direct contact should consider the strengths and limitations of both approaches, and not limited to costs, response rate, and representativeness. Although several demographic characteristics including age, race, sexual identity, and income were significantly associated with responding to the CMI invitation, we wish to highlight that the effect sizes (Cramer’s V) were small.

By partnering with CMI to enroll members from their LGBT panel, we were able to engage a population that is already attuned to participating in web-based studies. This ensures participants are familiar with, for example, how to complete a survey online as well as how to use a computer. Individuals who do not know how to use a computer or do not have Internet access would not be eligible to be a CMI panelist and thus would not be represented in this present study. It does seem, however, that what was once known as a digital divide (Kalichman, Benotsch, Weinhardt, Austin, & Luke, 2002; Kalichman, Weinhardt, et al., 2002; Pequegnat et al., 2007) has been closing—particularly among GBM both with the expanded uptake of Internet enabled mobile devices and the well documented use of the Internet by GBM to meet sex partners (Grov, Breslow, et al., 2014). We know of at least one organization (Knowledge Networks) that has overcome barriers in Internet and computer access by providing their panelists who do not have a computer or Internet with both as needed, as well as training panelists on how to use the device. Researchers have successfully partnered with Knowledge Networks to conduct sexuality studies among U.S. adults more broadly (Herbenick et al., 2009; Reece et al., 2010; Reece et al., 2009), and we know of one study of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals specifically (Herek et al., 2010). Response rates on these studies varied greatly. For the studies of U.S. adults more broadly it was 54.1% among women and to 55.1% among men. For the study of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals specifically (Herek et al., 2010), 86% responded; however, an additional 7.2% of respondents (56 of 775) were removed because they later disclosed they were heterosexual or refused to answer a question about their sexual identity.

Participants in the One Thousand Strong panel used the OraQuick© rapid HIV-antibody test. Because results must be interpreted within a limited time frame (20–40 minutes), participants were asked to photograph the test paddle and upload that result. Individuals who tested positive for HIV in our study needed confirmatory testing and we contacted these participants to facilitate that process. Other at-home testing options exist such as HomeAccess, where participants gather a small amount of blood (i.e., dried blood spot) and mail the sample for analysis (Khosropour et al., 2013). The benefit of HomeAccess is that they will conduct confirmatory testing. Researchers should fully consider the costs and benefits of whatever approach they use, as finger sticks may be unacceptable to some potential participants.

One benefit to use the Internet to enroll samples is the ability to anonymously engage potential participants. With that, however, comes a host of problems related to fraudulent participants and data, particularly if incentives are used (Bauermeister, Pingel, et al., 2012; Grey et al., 2015; Konstan et al., 2005; Teitcher et al., 2015). By design, our study was confidential, but not anonymous. Each of the 1071 participants enrolled in the study was verified to be unique through the process of sending and receiving HIV/STI testing kits to a personal address as well as using a unique phone number and email address for contact. That being said, the all the limitations of collecting self-reported data apply (e.g, social desirability).

Conclusions

The One Thousand Strong panel is comprised of 1071 HIV-negative GBM from across the U.S. and is being longitudinally followed for a period of three years. For the most part, the panel’s demographic diversity is comparable to that observed in other U.S. national online studies that have been conducted with MSM. In addition to online components, we were able to engage the panel in self-administered at-home HIV and STI testing and only a small proportion of potential participants opted to forgo these components. This suggests that there is high feasibility and acceptability of incorporating biological assays into research studies that would be otherwise fully online. For providers, our study also highlights the feasibility of using the Internet to engage GBM in at-home HIV and STI testing, which might be ideal for populations who otherwise have poor access due to lack of insurance, those who lack a LGBT affirming provider, and those living in rural areas.

However, and although observed effect sizes were small in our study, there may be additional barriers and challenges to engaging men of color into behavioral research, which is consistent with prior research (Sullivan et al., 2011). Given continued racial and ethnic disparities in HIV among MSM, including racial and ethnic minority individuals in research remains critical. Although bisexual men were equally likely to participate in the at-home CASI survey, they were less likely than gay identified men to complete at-home self-administered HIV and STI testing. Further investigation into the reasons for this lower engagement is necessary. Finally, we highlight that other platforms for electronically engaging with populations exist (e.g., text messaging, applications on phones/tablets). Much as the computer-based Internet was used for the present study, it will be important for future researchers to evaluate the ability to enroll and engage geographically diverse samples using alternate digital platforms.

Acknowledgments

The One Thousand Strong study was funded by NIH/NIDA (R01 DA 036466: Jeffrey T. Parsons & Christian Grov). We would like to acknowledge other members of the One Thousand Strong Study Team (Dr. Tyrel Starks, Michael Castro, Ruben Jimenez, Dr. Jonathan Lassiter, Brett Millar, Chloe Mirzayi, Raymond Moody, and Anita Viswanath) and other staff from the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training (Qurrat-Ul Ain, Andrew Cortopassi, Chris Hietikko, Doug Keeler, Chris Murphy, Carlos Ponton, and Brian Salfas). We would also like to thank the staff at Community Marketing Inc (David Paisley, Thomas Roth, and Heather Torch) and Dr. Patrick Sullivan, Jessica Ingersoll, Deborah Abdul-Ali, and Doris Igwe at the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409). Finally, special thanks to Dr. Jeffrey Schulden at NIDA and Dr. Elizabeth Kelvin at Hunter College. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Sources of Funding: One Thousand Strong was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA 036466: Parsons & Grov). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse Career Development Award (K01 DA039030).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Grov, Cain, Whitfield, Rendina, Pawson, Ventuneac, & Parsons all have no conflicts.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Adam BD, Murray J, Ross S, Oliver J, Lincoln SG, Rynard V. HIVstigma.com, an innovative web-supported stigma reduction intervention for gay and bisexual men. Health Education Research. 2011;26(5):795–807. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Carballo-Dieguez A, Ventuneac A, Dolezal C. Assessing motivations to engage in intentional condomless anal intercourse in HIV risk contexts (“bareback sex”) among men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(2):156–168. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Pingel E, Zimmerman M, Couper M, Carballo-Dieguez A, Strecher VJ. Data quality in HIV/AIDS web-based surveys: Handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods. 2012;24(3):272–291. doi: 10.1177/1525822X12443097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Ventuneac A, Pingel E, Parsons JT. Spectrums of love: examining the relationship between romantic motivations and sexual risk among young gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1549–1559. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0123-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D, Valentine G. Queer country: rural lesbian and gay lives. Journal of Rural Studies. 1995;11(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen AM. Internet sexuality research with rural men who have sex with men: can we recruit and retain them? Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(4):317–323. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen AM, Horvath K, Williams ML. A randomized control trial of Internet-delivered HIV prevention targeting rural MSM. Health Education Research. 2007;22(1):120–127. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull S, Lloyd L, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Recruitment and retention of an online sample for an HIV prevention intervention targeting men who have sex with men: the smart sex quest project. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):931–943. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell ER, Pines HA, Robbie E, Coleman L, Murphy RD, Hess KL, Gorbach PM. Use of the location-based social networking application GRINDR as a recruitment tool in rectal microbicide development research. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(7):1816–1820. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0277-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Ventuneac A, Dowsett GW, Balan I, Bauermeister J, Remien RH, Mabragaña M. Sexual pleasure and intimacy among men who engage in “bareback sex”. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(1):57–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9900-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Stoner SA, Mikko AN, Dhanak LP, Parsons JT. Efficacy of a web-based intervention to reduce sexual risk in men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;14:549–557. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9578-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Osmond D, Stall RD, Pollack L, Paul JP, Blower S, Coates TC. The continuing HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):907–914. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Health disparities in HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STDs, and TB. African Americans/Blacks; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/AfricanAmericans.html. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. HIV surveillance - men who have sex with men (MSM) 2015a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance_MSM.pdf.

- CDC. HIV surveillance – epidemiology of HIV infection (through 2013) 2015b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HIV/library/slidesets/index.html.

- Chang L, Krosnick JA. National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2009;73(4):641–678. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfp075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Humberstone M, DiFilippi J, Koblin BA, Remien RH. Increased high risk sexual behavior after September 11 in men who have sex with men: An internet survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2005;34:525–533. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-6278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Humberstone M, Wong T, Wolitski RJ. A comparison of on-line and off-line sexual risk in men who have sex with men: an event-based on-line survey. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;44:235–243. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802e298c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Rietmeijer C. HIV prevention and care in the digital age. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S94–97. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fcb878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Parsons JT, Tesoriero JM, Carballo-Dieguez A, Hirshfield S, Remien RH. HIV behavioral research online. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(1):73–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson MA, Shuchat Shaw F, Humberstone M, Hirshfield S, Hartel D. Increased HIV disclosure three months after and online video intervention for men who have sex with men (MSM) AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1081–1089. doi: 10.1080/09540120902730013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JL, Miller LC, Appleby PR, Corsbie-Massay C, Godoy CG, Marsella SC, Read SJ. Reducing shame in a game that predicts HIV risk reduction for young adult men who have sex with men: a randomized trial delivered nationally over the web. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2) doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Horvath KJ, Miner M, Ross MW, Oakes M, Rosser BR. Compulsive Sexual Behavior and Risk for Unsafe Sex Among Internet Using Men Who Have Sex with Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hart MM. Gay women, men, and families in rural settings: Toward the development of helping communities. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1987;15(1):79–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00919759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney KP, Kramer MR, Waller LA, Flanders WD, Sullivan PS. Using a geolocation social networking application to calculate the population density of sex-seeking gay men for research and prevention services. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014;16(11) doi: 10.2196/jmir.3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domeika M, Oscarsson L, Hallén A, Hjelm E, Sylvan S. Mailed urine samples are not an effective screening approach for Chlamydia trachomatis case finding among young men. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2007;21(6):789–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford J, Bolding G, Davis M, Sherr L, Hart G. Web-based behavioural surveillance among men who have sex with men: a comparison of online and offline samples in London, UK. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(4):421–426. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]