Introduction

(−)-Lobeline (1) (2R, 6S, 10S-, Fig. 1) is the major alkaloidal constituent of Lobelia inflata, a plant native to North America with a long history of use as a natural remedy. The plant is also called Indian tobacco because Native Americans smoked the dried leaves as a substitute for tobacco.1 The remarkable pharmacological profile of lobeline has been demonstrated in numerous studies, especially in the research areas of substance abuse and neurological disorders.2–5 Neurochemical and behavioral studies from our laboratories have suggested that the effect of lobeline on psychostimulant abuse is through inhibition of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2).2 In neuropharmacolgical studies, lobelane (2, Fig. 1), a “des-oxygen” derivative of lobeline, has been demonstrated to be a more specific VMAT2 inhibitor compared to lobeline.6,7 Lobelane is also behaviorally active in decreasing methamphetamine self-administration in rats,8 validating VMAT2 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of methamphetamine abuse. A number of lobeline/lobelane analogues have been designed and synthesized and the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of these analogues has been reviewed recently.5 The present review summarizes (2005–2014) the synthesis of lobeline, lobelane and structurally related analogues.

Figure 1.

I. Lobeline

The history of the use, biology and chemistry of alkaloids from Lobelia inflata, with a focus on lobeline, has been reviewed in 2004.3 The present survey focuses on the recent advances in the synthesis of lobeline for the years 2005–2014.

1. Epimerization of Lobeline

One of the most important chemical properties of lobeline is that it readily undergoes a pH-dependent epimerization at C2 of the piperidine ring via the transient retro-aza Michael addition product 3, yielding a mixture of 2R,6R-cis-lobeline (1) and its 2S,6S-trans-isomer 4 (Fig. 2).9–13

Figure 2.

2. Synthesis of Lobeline

Three elegant asymmetric syntheses of (−)-lobeline (1) have been discussed in previous reviews.3,9 However, those synthetic routes might not be suitable for large scale preparations as they are fairly lengthy and of low efficiency. Klingler and Sobotta14 have disclosed an efficient asymmetric hydrogenation process for the preparation of (−)-lobeline (1) from 2,6-cis-lobelanine (5) on an industrial scale (Scheme 1). The process involves a catalyst system consisting of dichloro-bis-[(cycloocta-1,5-diene)rhodium (I)] ([RhCl(COD)]2) and (2R,4R)-4-(dicyclohexyl-phosphino)-2-(diphenylphosphinomethyl)-N-methylaminocarbonyl pyrrolidine (6).15 Good yields in good optical purity were obtained utilizing this catalyst system. Lobelanine (5), a chemical precursor for the biosynthesis of lobeline,16 can be easily obtained by reaction of 3-oxo-3-phenylpropionic acid, glutaric dialdehyde, and methylamine hydrochloride in acetone and citrate buffer (Scheme 1).17

Scheme 1.

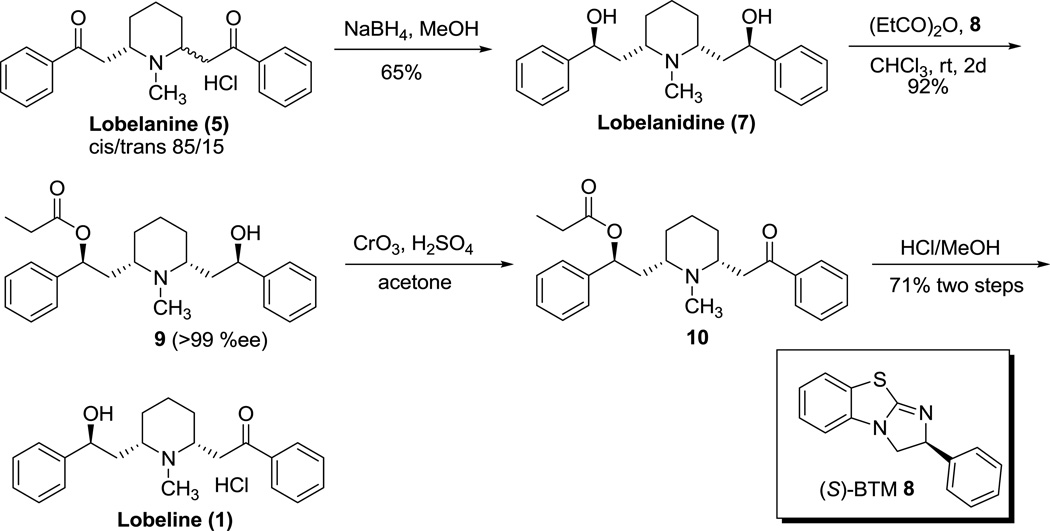

Birman et al.12 have reported an asymmetric synthesis of (−)-lobeline (1) via de-symmetrization of lobelanidine (7) with the use of a non-enzymatic, enantioselective acyl transfer catalyst, (S)-benzotetra-misole (BTM, 8), forming monoester 9, followed by oxidation with Jones’ reagent and removal of the acyl group under acid condition to avoid epimerization (Scheme 2). Lobelanidine (7), a minor alkaloid from Lobelia inflata, was synthesized by NaBH4 reduction of lobelanine (5) to afford an 85/15 mixture of diastereomeric diols in favor of 7, followed by recrytallization (Scheme 2).12 Lobelanine hydrochloride was obtained as an 85/15 mixture of cis/trans isomers using the same method described in Scheme 1.17

Scheme 2.

A Pd-catalyzed, aerobic oxidative, kinetic resolution method, developed by Stoltz group (Scheme 3),18,19 was used for selective oxidation of one of the two hydroxy groups in lobelanidine (7) to afford a 1:1 mixture of cis/trans equilibrating diastereomers of lobeline in high ee% (99%) (Scheme 4).13 Using a dynamic crystallization procedure by first converting the mixture of the cis/trans diastereomers into their hydrochloride salts, followed by heating in i-PrOH and slow cooling, the cis-isomer of lobeline was selectively precipitated out (Scheme 4).13 The lobelanidine (7) used in this procedure was synthesized via a novel multi-step route starting from aldehyde 11 (Scheme 4).13

Scheme 3.

Scheme 4.

Chênevert and Morin20 have reported the synthesis of (−)-lobeline (1) via enzymatic desymmetrization of lobelanidine (7). Acylation of 7 with vinyl acetate as both the acylation reagent and solvent in the presence of Candida antarctica lipase B (CAL-B) at 50 °C for 18 h afforded monoester 18 in 70% yield and high ee% (> 98%). Jones oxidation of the hydroxy group in 18, followed by removal of the acetyl group under acidic condition afforded (−)-lobeline (1) (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

II. Synthesis of Lobeline Derivatives

Using (−)-lobeline (1) as the starting material, a number of derivatives have been synthesized and utilized in biological screening assays. (−)-Sedamine (20), which can be considered as a “partial” analogue of lobeline, was synthesized by Zheng et al. utilizing the intramolecular retro-aza Michael addition reaction of (−)-lobeline (Scheme 6).10

Scheme 6.

A series of carboxylic acid esters (24) and sulfonic acid esters (25) of (−)-lobeline (1) has been reported by Hojahmat et al.21 These lobeline derivatives were synthesized by reacting 1 with various acyl chlorides and sulfonyl chlorides (Scheme 7). To minimize the epimerization of the products, the acylation and sulfonylation reactions were conducted in the absence of base. Wieland et al.22 and Flammia et al.23 treated (−)-lobeline (1) with PCl3 or SOCl2, respectively, to afford chloro analogue 26 (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Jones’ oxidation of the 10-hydroxy group of lobeline by Wieland and E. Dane24 affords lobelanine (5). Flammia et al.23 and Ebnöther25 both used 85% H3PO4 as a dehydration reagent to convert lobeline (1) to compound 27 (Scheme 8). As reported by Ebnöther,25 the carbonyl functional group of lobeline can be stereoselectively reduced to lobelanidine (7) using either NaBH4 or LAH. Such stereroselectivity for the reduction of ketone was also reported by Birman et al.12 However, no mechanism has been proposed. Based on the crystal structure of lobelanidine,26 there is a three-centered intramolecular hydrogen bond between the nitrogen atom and the two oxygen atoms in lobelanidine. Such structural feature is probably the driving force for the stereoselectivity. Or maybe the starting material, lobeline, forms similar type of intramolecular H bond thus resulted in face selectivity.

Scheme 8.

Flammia et al.23 reported the synthesis of compound 28a via Clemmensen reduction of lobeline (Scheme 8).23

Stereoisomers of compound 28a, i.e. compounds 28b, 28c, and 28d, have been synthesized using 28a and 27 as starting materials (Scheme 9) by Zheng et al.27 Conversion of 28a to compound 29 under Jones’ oxidation conditions, followed by NaBH4 reduction, gave a mixture of 28a and 28b, in a ratio of 9:20, from which 28a was isolated by fractional recrystallization of the isomeric mixture; 28b was obtained by purification via silica gel chromatography from the mother liquors. Similarly, reduction of compound 27 with NaBH4 afforded 28c and its diastereomer 28d, which were isolated in a manner similar to 28a and 28b. The structures of 28c and 28d were characterized by comparing NMR with their corresponding enantiomers 28a and 28b, respectively. Hydrogenation of 28a, 28b, 28c, and 28d afforded the corresponding saturated compounds 30a, 30b, 30c, and 30d, respectively (Scheme 9).27

Scheme 9.

Further de-functionalization of lobeline resulted into a series of “des-oxygenated” analogues (Scheme 10), as reported by Zheng et al.6 Epimerization of cis-lobeline (1) at C-2 under basic condition in methanol for 48 h at room temperature afforded a 1:1 mixture of the two C-2 epimers, which were reduced to product 31, consisting a mixture of the four possible diastereomers. Dehydration of 31 with 85% H3PO4 yielded a mixture of cis- and trans-distyryl compounds 32a (cis-) and 32b [(−)-2S,6S-trans], which could be readily separated by silica gel column chromatography. The structural of 32a and 32b were further confirmed by X-ray crystallography.28,29 Hydrogenation of 32a and 32b afforded lobelane (2) and its (−)-2S,6S-trans isomer, respectively. Similarly, epimerization of 29, followed by reduction and dehydration, yielded 32a and its (+)-2R,6R-trans epimer (32c). Hydrogenation of 32c afforded (+)-2R,6R-trans-lobelane. Simultaneous reduction of the double bond and the carbonyl group of cis/trans 29 by Pd/C catalyzed hydrogenation in 10% HOAc/MeOH afforded 34a. Dehydration of 34a yielded 35a and 35b. Similarly, compounds 35c and 35d, enantiomers of 35a and 35b, respectively, were obtained from 27 by following the same procedure for the synthesis of 35a and 35b from 29. Separation of 35a from 35b and 35c from 35b was accomplished by silica gel chromatography.

Scheme 10.

III. Synthesis of Lobelane Analogues

All the lobeline analogues synthesized in Section II were evaluated for their interaction with VMAT.6,7 Lobelane (2) appears to be the most selective and potent VMAT2 inhibitor.7 Systematic structural modifications have been carried out on the lobelane molecule in searching for analogues with increased potency/selectivity and improved drug proprieties (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

1. Analogues with Modifications on the Phenyl Rings

Lobelane can also be synthesized via a three-step procedure,30 initial condensation of 2,6-lutidine with benzaldehyde, forming the conjugated product 36 (Ar = Ph), followed by hydrogenation in the presence of Adams’ catalyst, to give nor-lobelane 37 (Ar = Ph), and N-methylation using NaCNBH3/(CH2O)n (Scheme 11). Utilizing the same approach, a series of lobelane and nor-lobelane analogues, 37 and 38, in which the two phenyl rings are replaced by two naphthalenyl rings or substituted phenyl rings, has been synthesized (Scheme 11).6,31

Scheme 11.

The synthesis of azaaromatic ring containing lobelane analogues, on the other hand, had to be carried out utilizing an alternative approach, since side-chain azaaromatic moieties are also susceptible to hydrogenation under Adams’ catalyst. Vartak et al..32 have employed N-methylated 2,6-lutidine (39) as a condensation partner with various azaaromatic aldehydes to form compound 40,33 which was then hydrogenated to afford the desired product 41. Interestingly, each type of heterocyclic moiety requires different reaction conditions for both condensation (method A) and hydrogenation (method B) steps (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12.

Ding et al.34 have reported an efficient synthesis of an azaaromatic analogue of nor-lobelane, cis-2,6-di-(2-quinolylpiperidine) (42), featuring a Wittig reaction between dialdehyde 45 and phosphonium intermediate 46. Compound 45 was synthesized via Swern oxidation of dihydroxy 44, derived from pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (43). Compound 46 was synthesized via a four-step procedure by initial SeO2 oxidation of 2-methylquinoline (49), followed by reduction, bromination, and phosphonium intermediate formation (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

Conversion of 47 to 42 was achieved by deprotection of the Cbz group using 6 N HCl at reflux followed by catalytic hydrogenation to reduce the double bonds (Scheme 13). Attempts to convert 47 into 42 in one step, via simultaneous removal of the Cbz group and reduction of the double bonds by hydrogenation were not successful, possibly due to hydrogenolytic ring opening of the piperidine ring under these conditions. The method should be applicable to the synthesis of other heterocyclic analogues.34

2. Analogues with Modifications on the Ethylene Linkers of Lobelane

In a series of lobelane homologues, the two ethylene groups connecting the two phenyl rings to the C-2 and C-6 positions of the piperidine ring in lobelane have been replaced by linkers of 0–3 carbons (Figure 4).35

Figure 4.

Analogue 51, in which two phenyl rings are attached directly to C-2 and C-6 of the central piperidine ring, was synthesized by initial N-methylation of 2,6-biphenylpyridine (60), followed by exhaustive reduction of the pyridinium moiety in 61 with sequential NaBH4 reduction and catalytic hydrogenation (Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

Analogue 52a was obtained by catalytic hydrogenation of 65, which was synthesized via Suzuki coupling of 2-chloro-6-benzylpyridine (64) with phenylboronic acid using [1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene](3-chloropyridyl)palladium(II) dichloride (PEPPSI-IPr) as a catalyst and t-BuOK as a base in i-PrOH.36 Compound 64 was synthesized by Kumada coupling of 2-bromo-6-methoxypyridine (62) with benzylmagnesium chloride, followed by treatment of the coupling product 63 with POCl3 in DMF. Analogue 52a was converted to 52b by N-methylation, as described in Scheme 11 (Scheme 15).

Scheme 15.

Analogues 53a/53b and 54a/54b were synthesized from compounds 68 and 69, respectively, in a similar manner as described above for the synthesis of 52a/52b from 65. Compound 67, the common intermediate for 68 and 69, was synthesized by Suzuki coupling of 2-bromo-6-methylpyridine (66) with phenylboronic acid. Condensation of 67 with benzaldehyde, or deprotonation of the 2-methyl group of 67 followed by an SN2 reaction with 2-iodoethylbenzene afforded 68 and 69, respectively (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16.

Similarly, analogues 55a/55b, 56a/56b, and 57a/57b, which contain a single methylene linker at C-6 and a methylene, an ethylene or a propylene linker at C-2 of the piperidine ring, were prepared from their corresponding pyridinyl precursors, 71, 72, and 73, respectively (Scheme 17 and 18). Compound 71 was obtained via Kumada coupling of 2,6-dibromopyridine (70) with benzylmagnesium chloride (Scheme 17). Compounds 72 and 73 were synthesized via Negishi coupling of 64 with 2-phenyl-1-ethylzinc iodide or 3-phenyl-1-propylzinc iodide, respectively, using PEPPSI-IPr as a catalyst and LiBr as an additive in THF/DMF (Scheme 18).37

Scheme 17.

Scheme 18.

Analogues 58a and 58b, in which the two phenyl rings are linked to the central piperidine ring by an ethylene moiety at C-6 and a propylene moiety at C-2, were synthesized by initial mono-condensation of 2,6-lutidine with benzaldehyde, yielding the conjugated product 74, followed by a similar procedure to that described in Scheme 16 for the synthesis of 54a and 54b (Scheme 19).

Scheme 19.

Analogues 59a/59b were synthesized using a similar procedure to that described for the synthesis of 55a/55b (Scheme 20).

Scheme 20.

It is important to note that analogues 52a/52b, 53a/53b, 54a/54b, 56a/56b, 57a/57b, and 58a/58b, synthesized as described in Schemes 15, 16, 18, and 19, all are in racemic forms. Racemic mixtures are acceptable for initial pharmacological assays; however, chiral pure compounds should be used for further studies. Thus, enantioselective synthetic methods need to be developed, should any of these analogues selected for further development.

3. Isomerized Lobelane Analogues

A series of isomerized lobelane analogues in which the C2, C6 phenethyl groups of lobelane are repositioned to the N1, C2 (77a); N1, C3 (77b); N1, C4 (77c); C2, C4 (78a/78b); or C3, C5 (79a/79b) positions of the piperidine ring, has been synthesized (Figure 5).31

Figure 5.

The syntheses of these analogues were initiated from the condensation reaction of 2-, 3-, 4-picoline, 2,4-, or 3,5-lutidine with benzaldehyde or N-benzylidene-4-chloroaniline (for 3-picoline and 3,5-lutidine) to form conjugated products 80 or 82. Due to the low activity of the pyridinyl 3-methyl group, N-benzylidene-4-chloroaniline was used as an activated form of benzaldehyde in the condensation reactions. Transformation of 80 and 82 to their corresponding final products was achieved by utilizing a similar procedure to that used for the synthesis of 37 and 38 in Scheme 11 (Scheme 21 and 22).

Scheme 21.

Scheme 22.

Compounds 83a and 83b, which are isomerized and unsaturated lobelane analogues containing a linker unit that is one carbon shorter between the piperidine and the phenyl rings than compound 79a/79b, were synthesized starting from N-methyl-4-piperidone (84).38 Condensation of 84 with an aromatic aldehyde afforded compound 85, which was treated with a pre-equilibrated 1:4 (mol/mol) mixture of sodium borohydride and trifluoroacetic acid in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of DCM and ACN to yield two separable geometrical isomers 83a and 83b (Scheme 23).

Scheme 23.

4. Analogues with Modifications on the Piperidine Ring

The piperidine ring of lobelane has been replaced by a piperazine, quinuclidine, tropane, pyrrolidine, or azetidine ring, for a variety of SAR studies.

a) Analogues Containing a Piperazine Ring

The synthesis of piperazine ring-containing analogues, 86a and 86b, was achieved by employment of a similar approach to that described in Scheme 11 for the synthesis of 37 and 38, using 2,6-dimethylpyrazine (87) as a starting material (Scheme 24).31

Scheme 24.

b) Analogues Containing a Conformational Restricted Heterocyclic Ring

The quinuclidine ring represents a conformationally restricted form of the piperidine ring. Quinuclidine ring-containing compounds 89a and 89b have been designed to mimic the stereochemistry of the spatially confined axial/axial conformer or the fully extended equatorial/equatorial conformer of lobelane, respectively. Both compounds were synthesized via an SN2-type cyclization of intermediates 92 and 93, respectively.39 Utilizing a dissolving metal reduction procedure developed by Watson et al.,40,41 2,4-trans-isomer 92 was obtained from its precursor 90 with high stereoselectivity (16:1, trans:cis). The Troc group was also removed during the reaction. Under similar reaction conditions, 2,4-cis-isomer 93 was obtained from compound 91, a des-Troc product of 90 (Scheme 25).

Scheme 25.

Compound 90 was synthesized via Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of piperidinone intermediate 94 with triethyl phosphonoacetate. Two synthetic routes were used for the synthesis of 94. The first route starts with the condensation of 2,6-dimethyl-4-hydroxypyridine (95) with benzaldehyde, followed by catalytic hydrogenation to form compound 96. O-Benzylation of 96 with BnBr in the presence of K2CO3 in DMF, followed by N-benzylation by treatment with excess BnBr (20 equivalent) in ACN afforded the quaternary ammonium product 97. Reduction of 97 with NaBH4 followed by the treatment with TFA in DCM/H2O furnished piperidinone 98. Replacement of the N-benzyl group in 94 with an N-Troc group afforded the desired intermediate 94 (Scheme 26).39

Scheme 26.

The second synthetic route for the preparation of compound 94, a more efficient method compared to the one above, is based on a strategy developed by the Comins’ group,42–45 involving sequential stereoselective addition of Grignard reagent phenethylmagnesium chloride to the N-Troc pyridinium salt of 4-methoxypyridine (99) (Scheme 27).39

Scheme 27.

The tropane ring represents another conformationally restricted form of the piperidine ring. Analogues 101 and 102, in which a trop-2-ene or tropane ring is substituted for the piperidine ring in lobelane, were synthesized.46 Clemmensen reduction of compound 103 afforded 101, which was converted to 102 by catalytic hydrogenation. Compound 103 was obtained by aldol condensation of tropinone with benzaldehyde or a substituted benzaldehyde (Scheme 28).

Scheme 28.

c) Analogues Containing a Smaller Sized Pyrrolidine or Azetidine Ring

Pyrrolidine-containing lobelane analogues, 105a, 105b, 106a, 106b, have been prepared by initial nucleophilic addition of phenethylmagnesium chloride to Katritzky’s bicyclic hemiaminal 108, forming a pair of separable diastereomers 109a and 109b in a 2:1 ratio.47 Hydrogenolysis of 109a and 109b by a catalytic hydrogen transfer reaction with Pd(OH)2 on carbon as a catalyst and ammonium formate as a hydrogen source afforded the meso isomer 105a and the (+)-trans-2R,5R isomer 106a, respectively, which were then treated with paraformaldehyde and NaBH(OAc)3 to form their corresponding N-methylated products 105b and 106b (Scheme 29).48 Starting from D-phenylglycinol (110) in place of L-phenylglycinol (107) in the above synthetic route, the (−)-trans-2S,5S isomer 111a and its N-methylation product 111b were also obtained (Scheme 29).48 Utilizing this synthetic strategy, a series of homologues of 105a/105b, including 112a/112b and 113a/113b,48 and phenyl ring substituted analogues of 105a, i.e. compounds 114,49 has been synthesized (Figure 6).

Scheme 29.

Figure 6.

A series of cis-meso and trans-racemic azetidine-containing lobelane analogues, 115 and 116, respectively, has been synthesized from cis- (118) and trans-dibenzyl 1-benzylazetidine-2,4-dicarboxylate (119), respectively (Scheme 30).50 The synthetic approach is similar to the synthesis of 42 described in Scheme 13. Isomers 118 and 119 were obtained as a separable (by silica gel column) 2:1 mixture, via a reported four-step sequence starting from glutaric anhydride (117).51,52 Treatment of 118 with NaBH4 afforded diol 120, which was then converted into compound 121 via hydrogenolysis of the benzyl group followed by protection of the exposed NH with a Cbz group. Swern oxidation of alcohol 121, followed by in situ Wittig olefination with an appropriate phosphonium salt afforded compound 122. Hydrogenation of the alkene moieties in 122 with simultaneous hydrogenolysis of N-Cbz group under Pd/C or Pd(OH)2 catalyzed hydrogenation resulted in a complex mixture. Instead, 122 was hydrogenated in the presence of Wilkinson’s reagent to afford compound 123, followed by removal of the Cbz group via hydrogenolysis over Pd/C to yield 115. Utilizing the same procedure, trans isomer 116 was obtained from 119 (Scheme 30).50

Scheme 30.

5. Analogues with Modifications on the N-Methyl Group

Replacement of the N-methyl group in lobelane with a more polar N-substituent, i.e. carboxylic ester, nitrile, hydroxy, hydrazine, amine, and guanidine, has been carried out.53 These analogues were designed to have improved water solubility. N-Alkylation of nor-lobelane with methyl bromoacetate or chloroacetonitrile afforded analogues 124 and 125, respectively. Treatment of 124 and 125 with DIBAL-H furnished the corresponding amino alcohol analogue 126 and the diamino analogue 127. N-Methylation of 127 afforded 128. Reaction of 127 with N,N′-di-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)thiourea, followed by treatment with CF3COOH afforded the guanidino analogue 129. Conversion of nor-lobelane to the corresponding hydrazino analogue 130 was accomplished by initial N-nitrosation followed by LAH reduction. N-Methylation of 130 afforded dimethyl derivative 131 (Scheme 31).

Scheme 31.

Analogues 132a and 132b, which contain an N-1,2(R)-dihydroxypropyl and N-1,2(S)-dihydroxypropyl group, respectively, were prepared by reacting phenyl ring substituted nor-lobelane analogue 37 with S-glycidol or R-glycidol, respectively (Scheme 32).53 Similarly, Penthala et al.49 has synthesized a series of N-1,2(R)-dihydroxypropyl derivatives of 105a and 114 (Scheme 33).

Scheme 32.

Scheme 33.

Conclusion

This review has summarized the progress on the synthesis of lobeline, lobelane, and their analogues. Significant progress has been made over the last 10 years on the development of efficient methods for the total synthesis of lobeline and on extensive structural modifications of lobelane. With the continued interest in finding treatments for psychostimulant abuse, drug discovery effort based on structural modification of the lobeline and lobelane molecules is likely to continue. The authors hope that this review will generate more interest in future SAR expansion on these molecules.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by NIH grant R01DA13519 and U01DA13519.

References

- 1.Millspaugh CF. Lobelia Inflata. American Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated and Descriptive Guide to Plants Indigenous to and Naturalized in the United States Which Are Used in Medicine. New York, NY: Dover; 1974. p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;63:89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felpin FX, Lebreton J. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:10127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. AAPS J. 2006;8:E682. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crooks PA, Zheng G, Vartak AP, Culver JP, Zheng F, Horton DB, Dwoskin LP. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011;11:1103. doi: 10.2174/156802611795371332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Norrholm SD, Crooks PA. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5551. doi: 10.1021/jm0501228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickell JR, Krishnamurthy S, Norrholm S, Deaciuc AG, Siripurapu KB, Zheng G, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP. J. Pharmcol. Exp. Ther. 2010;332:612. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.160275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neugebauer NM, Harrod SB, Stairs DJ, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;571:33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felpin FX, Lebreton A. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:9192. doi: 10.1021/jo020501y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8514. doi: 10.1021/jo048848j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compere D, Marazano C, Das BC. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:4528. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birman VB, Jiang H, Li X. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3237. doi: 10.1021/ol071064i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan S, Bagdanoff JT, Ebner DC, Ramtohul YK, Tambar UK, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;30:13745. doi: 10.1021/ja804738b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klingler FD, Sobotta R. PCT Int. Appl. 2006 WO 2006008029. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klingler FD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1367. doi: 10.1021/ar700100e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odonovan DG, Forde T. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1971:2889. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schöpf C, Lehmann G. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1935;518:1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7725. doi: 10.1021/ja015791z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagdanoff JT, Stoltz BM. Angew Chem. Int. Edit. 2004;43:353–357. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chenevert R, Morin P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:1837. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hojahmat M, Horton DB, Norrholm SD, Miller DK, Grinevich VP, Deaciuc AG, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:640. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieland H, Schöpf C, Hermsen W. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1925;444:40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flammia D, Dukat M, Damaj MI, Martin B, Glennon RA. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:3726. doi: 10.1021/jm990286m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wieland HK, Dane E. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1929;473:118. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebnöther A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1958;41:386. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19760590721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arai T, Tanaka R, Hirayama N. Anal. Sci. 2004;20:x83. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng G, Horton DB, Deaciuc AG, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:5018. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng G, Parkin S, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E. 2009;66:o77. doi: 10.1107/S1600536809049617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng G, Parkin S, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E. 2009;66:o78. doi: 10.1107/S1600536809049587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JF, Freudenberg W. J. Org. Chem. 1944;9:537. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Zhu J, Jones MD, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:3899. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vartak AP, Deaciuc AG, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:3584. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fichera M, Fortuna CG, Impallomeni G, Musumarra G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002:145. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding DR, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:5211. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:6509. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Brien CJ, Kantchev EA, Valente C, Hadei N, Chass GA, Lough A, Hopkinson AC, Organ MG. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:4743. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Organ MG, Avola S, Dubovyk I, Hadei N, Kantchev EA, O'Brien CJ, Valente C. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:4749. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horton DB, Siripurapu KB, Norrholm SD, Culver JP, Hojahmat M, Beckmann JS, Harrod SB, Deaciuc AG, Bardo MT, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP. J. Pharmcol. Exp. Ther. 2011;336:940. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Crooks PA. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6072. doi: 10.1021/jo901082r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watson PS, Jiang B, Scott B. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3679. doi: 10.1021/ol006589o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson PS, Jiang B, Harrison K, Asakawa N, Welch PK, Covington M, Stowell NC, Wadman EA, Davies P, Solomon KA, Newton RC, Trainor GL, Friedman SM, Decicco CP, Ko SS. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:5695. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Comins DL, Brown JD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:4549. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown JD, Foley MA, Comins DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:7445. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Comins DL, Lamunyon DH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:5053. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comins DL, Joseph SP, Goehring RR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4719. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:4463. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katritzky AR, Cui XL, Yang B, Steel PJ. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1979. doi: 10.1021/jo9821426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vartak AP, Nickel JR, Chagkutip J, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:7878. doi: 10.1021/jm900770h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Penthala NR, Ponugoti PR, Nickell JR, Deaciuc AG, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:3342. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding D, Nickell JR, Deaciuc AG, Penthala NR, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:6771. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodebaug RM, Cromwell NH. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1968;5:309. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baldwin JE, Adlington RM, Jones RH, Schofield CJ, Zaracostas C, Greengrass CW. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:4879. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng G, Horton DB, Penthala NR, Nickell JR, Culver JP, Deaciuc AG, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Med Chem Comm. 2013;4:564. doi: 10.1039/C3MD20374C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]