Abstract

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is an adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder presenting with motor impairment and autonomic dysfunction. Urological function is altered in the majority of MSA patients, and urological symptoms often precede the motor syndrome. To date, bladder function and structure have never been investigated in MSA models. We aimed to test bladder function in a transgenic MSA mouse featuring oligodendroglial α-synucleinopathy and define its applicability as a preclinical model to study urological failure in MSA. Experiments were performed in proteolipid protein (PLP)–human α-synuclein (hαSyn) transgenic and control wild-type mice. Diuresis, urodynamics, and detrusor strip contractility were assessed to characterize the urological phenotype. Bladder morphology and neuropathology of the lumbosacral intermediolateral column and the pontine micturition center (PMC) were analyzed in young and aged mice. Urodynamic analysis revealed a less efficient and unstable bladder in MSA mice with increased voiding contraction amplitude, higher frequency of nonvoiding contractions, and increased postvoid residual volume. MSA mice bladder walls showed early detrusor hypertrophy and age-related urothelium hypertrophy. Transgenic hαSyn expression was detected in Schwann cells ensheathing the local nerve fibers in the lamina propria and muscularis of MSA bladders. Early loss of parasympathetic outflow neurons and delayed degeneration of the PMC accompanied the urological deficits in MSA mice. PLP-hαSyn mice recapitulate major urological symptoms of human MSA that may be linked to αSyn-related central and peripheral neuropathology and can be further used as a preclinical model to decipher pathomechanisms of MSA.

Keywords: synuclein, urinary bladder, postresidual volume, cystometry, animal model

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a sporadic adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder that features motor impairment and autonomic dysfunction.1 The motor syndrome commonly includes atypical parkinsonism and cerebellar and pyramidal signs in various combinations.2 The motor manifestation may be predominately parkinsonism in the parkinsonian (MSA-P) subtype or ataxia in the cerebellar (MSA-C) subtype of the disease as defined by the current MSA diagnostic criteria.3 MSA belongs to the group of α-synucleinopathies, and its pathological hallmark, α-synuclein (αSyn)–positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs), are widespread throughout the central nervous system (CNS).4,5 Clinicopathological correlations link striatonigral degeneration (SND) to parkinsonism, whereas olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA) represents the neuropathological substrate of ataxia in MSA.6

Nonmotor features are often premonitory of MSA onset.7 Autonomic failure featuring urogenital dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and respiratory dysfunction makes up the leading nonmotor presentation of MSA and is further essential for the diagnosis of the disease. Retrospective data analyses indicate that urological symptoms emerge early and may precede the neurological presentation by several years in the majority of MSA patients.8

The disturbed urinary bladder control in MSA is associated with widespread degeneration of nigral dopaminergic pathways and nondopaminergic areas, including the pontine micturition center (PMC, also called Barrington’s nucleus), periaqueductal gray, locus coeruleus, cerebellar Purkinje cells, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, intermediolateral columns of the spinal cord, and Onuf’s nucleus.9,10

Transgenic mice with targeted overexpression of human αSyn (hαSyn) in oligodendroglia have been developed to reproduce GCIs and to study related mechanisms of neurodegeneration relevant to the human disease.11 The available models have been thoroughly analyzed in terms of progression of neurodegeneration and motor disability12–17; however, to date, no evaluation of nonmotor deficits in transgenic MSA models has been performed. Several recent neuropathological findings in transgenic mice with oligodendroglial overexpression of hαSyn under the proteolipid protein (PLP) promoter,14,18 including progressive neurodegeneration of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), locus coeruleus, and Onuf’s nucleus suggest possible urinary dysfunction in the MSA model similar to that in human MSA.9 The aim of the present study was to analyze urinary bladder function and structure as well as to identify neuropathology in centers of micturition control in PLP-hαSyn mice, which may model urinary dysfunction in human MSA.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted on 2- and 12-month-old female and male PLP-hαSyn transgenic mice (called MSA mice from here on) that were previously described.14,15,17–20 We used genetic background-, age-, and sex-matched wild-type C57Bl/6 mice (WTs) as controls. Animals were housed in a 12-hour light–dark cycle and allowed water and standard food ad libitum. The experiments were performed with permission of the ethical committee of KU Leuven, Belgium. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Diuresis

Following a 24-hour habituation period, mice were monitored in metabolic cages over a period of 24 hours. The dark period started 6 hours after the beginning of the monitoring and lasted for 12 hours. Urine output was quantified with balances (A&D Company Limited, Griesheim, Germany) placed underneath the cages. Urine collectors were filled with olive oil to avoid evaporation of the voided volume.

Cystometry

The cystometry assay was performed as previously published21 under urethane anesthesia (1.2 g/kg, subcutaneously; Sigma Aldrich, Bornem, Belgium). Via an abdominal midline incision, a PE-50 polyethylene catheter (BD Benelux, Erembodegem, Belgium) with a cuff was inserted in the bladder dome and fixed using a 6/0 monofilament polypropylene purse-string sutures (Ethicon, Noderstedt, Germany). The catheter was flushed with saline to exclude leakage and then tunneled subcutaneously to the neck. Finally, the abdominal wall and skin were closed. The bladder catheter was connected to a pressure transducer (BD Benelux, Erembodegem, Belgium) and an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) via a T tube. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C using a heating lamp and a temperature probe. The pressure transducer output was amplified and recorded using a Windaq data acquisition system (Dataq Instruments, Akron, OH). Bladders were filled at a constant rate (20 μL/minute) with saline and after a 30-minute equilibration period, the intravesical pressure was recorded for 30 minutes. Individual urine voids were collected with filter paper, which was weighed to determine the voided volume.

Contractility

Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and bladders were excised, placed in Krebs solution (NaCl 118 mM, KCl 4.6 mM, CaCl2 2.5 mM, MgSO4 1.2 mM, KH2PO4 1.2 mM, NaHCO3 25 mM, and glucose 11 mM in water), and cut longitudinally from the bladder neck toward the fundus bilaterally to yield 1 longitudinal strip of standardized dimensions (5 × 3.5 mm). The fundus was left intact and became the middle of each bladder strip. The bladder strips were weighed, placed in an organ bath (190 mL), and attached with a fine ligature to a steel hook at one end and to a fixed force transducer at the other end (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) to enable isometric measurements. The incubation fluid was Krebs solution. This was constantly gassed with a mixture of oxygen (95%) and carbon dioxide (5%), and the temperature was maintained between 35 °C and 37 °C. Transducers were calibrated before each experiment. Contractility was measured as tension changes, which were sampled using homemade software that was driving 2 of the 4 A/D channels of a Dalanco D310 DSP board (Dalanco Spry, Rochester, NY) that was connected to the transducers. These recorded data were analyzed offline with OriginPro 7.0 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA). During the accommodation period (30 minutes), we aimed to create a similar pretension on all bladder strips. This was obtained by an initial preload of 1 g, and subsequent readjustments were made every 10 minutes. In each experiment, carbachol (100 nM) was added directly to the organ baths. Then the organ baths were renewed with fresh Krebs solution. Contractility was assessed by depolarizing the strips with a solution containing 27.7 mM KCl.

Bladder Imaging

Frozen sections (10 μm) were prepared from bladders fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS: 2 hours at 4 °C) and cryoprotected in 25% sucrose in PBS for 48 hours before embedding in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed following a standard protocol, and slices were dehydrated in ethanol and mounted with Entellan (Merck, Overijse, Belgium).

For nuclear staining, slices were incubated in 10% donkey serum for 30 minutes, followed by Hoechst stain (1:2000) for 5 minutes at room temperature, and mounted with Fluorsafe (Calbiochem, Overijse, Belgium). For better visual interpretation, colors were inverted to black and white with Image J software. Detrusor cell density was measured by counting the number of individual Hoechst-stained nuclei by surface unit. Images were collected using an Olympus BX41 microscope.

Immunofluorescence for hαSyn was performed according to standard protocols applying the primary monoclonal antibody 15G7 (Enzo Life Sciences, Lörrach, Germany) and secondary Alexa 488–conjugated goat antirat IgG (Dianova, Germany). Counter-staining was done with DAPI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNP) monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was applied as a marker of Schwann cells (SCs) and visualized by secondary Alexa 546–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Dianova, Germany). All immunostaining was performed in parallel to negative controls omitting the primary antibodies. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on a DMI 4000B Leica microscope provided with a Digital Fire Wire Color Camera DFC300 FX.

Neuropathology

Mice were perfused transcardially with 4% PFA, and brains and lumbosacral spinal cords were dissected and postfixed with 4% PFA overnight. After cryoprotection with 25% sucrose, the tissue was sliced on a cryostat (Leica, Nussloch, Germany) at 40 μm. Sections were mounted on slides and stained with cresyl violet. The intermediolateral column (IML) was delineated at the level of L6–S1 according to the Atlas of the Mouse Spinal Cord.22 Barrington’s nucleus, intercalated between the locus coeruleus and laterodorsal tegmental area, was delineated in coronal brain sections at Bregma level −5.40 mm according to the mouse brain atlas.23 The number of neurons was determined using a Nikon 80i microscope provided with StereoInvestigator10 software and imaging system (MicroBrightField Europe e. K., Magdeburg, Germany).

Statistical Analysis

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of the means observed in WT and MSA mice were performed using the Student t test (GraphPad Prism 5, La Jolla, CA). Histological data were analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance with genotype and age as variables.

Results

Voiding Behavior in MSA Transgenic Mice

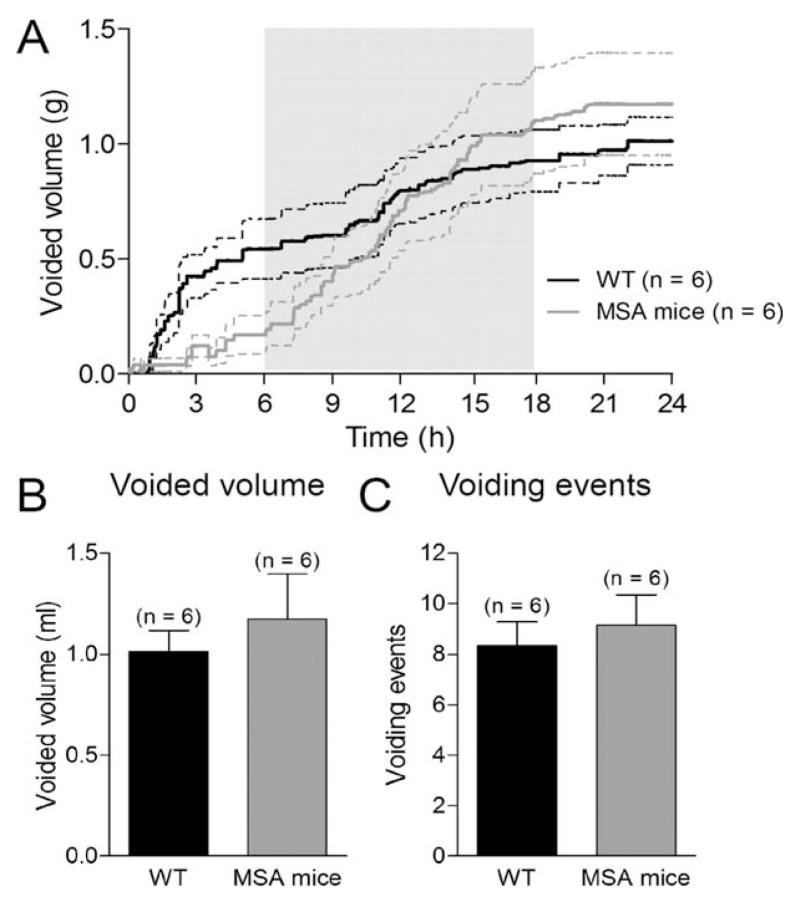

To assess the function of the urinary tract, we measured the voiding behavior of MSA transgenic mice by quantifying the urine drops of freely moving mice over a period of 24 hours with a 12-hour light–dark cycle. Total diuresis and the number of single voiding events were similar between control and MSA mice (Fig. 1A,C). Because bladder function is highly related to the amount of urine produced by the kidney, by evaluating 24-hour output, we excluded renal tubular dysfunction in the MSA model.

FIG. 1.

Diuresis. A: Diuresis in 12-month-old MSA and control wild-type (WT) mice was monitored over a period of 24 hours with dark phase between the 6th and the 18th hours of the observation period. Total voided volume (B) and voiding events (C) within 24 hours were similar between MSA and WT mice. Data are mean ± SEM.

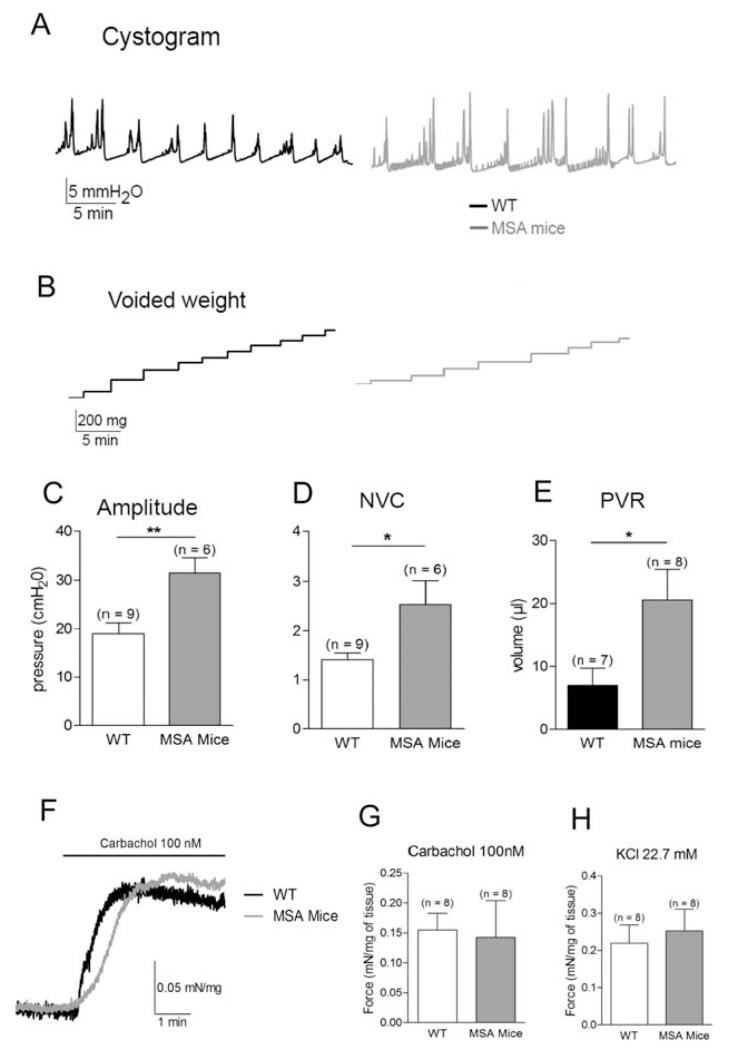

MSA Bladders Are Hyperactive and Less Efficient

The urodynamic investigation did not reveal any striking differences in the general pattern between MSA and WT mice (Fig. 2A,B). Intercontractile interval, basal pressure, and relative threshold pressure were similar (data not shown). However, the amplitude of voiding contraction was increased in MSA mice (from 18.9 ± 2.2 to 31.5 ± 3.2 cm H2O; P < .01; Fig. 2C). During the filling phase there were more nonvoiding contractions in MSA mice than in WT mice (2.5 ± 0.5 and 1.4 ± 0.1, respectively; P < .01; Fig. 2D). We did not observe any urine leakage during these nonvoiding contractions, as would be expected because of the high intravesical pressure, suggesting possible dyssynergia between the detrusor and the sphincter. Finally, the postvoid residual volume showed an increase 3 times the average (7.1 ± 2.7 μL in WT mice and 20.6 ± 4.9 μL in MSA mice; P < .05; Fig. 2E). These results indicated that bladder function in MSA mice was less stable and efficient.

FIG. 2.

Bladder function. A: Typical cystometry traces in 12-month-old WT and MSA mice. B: Voiding contractions were confirmed by measuring the voided volume during the cystometry experiments. Increased amplitude (C), increased frequency of nonvoiding contractions (NVCs; D), and increased postvoid residual (PVR) volume (E) were observed in MSA mice. F: Representative trace of muscle strip experiment following application of carbachol (100 nM) in WT and MSA mice. Force exerted by detrusor strips was similar in WT and MSA bladders on stimulation of carbachol (G) or following depolarization with a 22.7-mM KCl solution (H). Data are mean ± SEM; *P < .05, **P < .01.

Bladder Contractility Is Not Altered in Transgenic MSA Mice

Bladder contractions are induced by the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction by efferent nerves. We applied carbachol (100 nM), a nonselective muscarinic receptor agonist, on detrusor strips to assess detrusor contractility (Fig. 2F,G). No difference in the contractile force between the groups following application of carbachol was observed (0.15 ± 0.02 mN/mg in WT mice vs 0.14 ± 0.06 mN/mg in MSA mice; P > .05). To control the efficiency of the contractile machinery, we further depolarized bladder strips with a 22.7 mM KCl solution (Fig. 2H). No significant differences between WT and MSA mice were detected (0.22 ± 0.05 and 0.25 ± 0.05 mN/mg, respectively; P > .05). These results indicate that the contractile properties of the MSA mouse urinary bladder to physiological stimuli were not modified; rather, the lack of efficient bladder emptying in the MSA mice was a result of changed neural control.

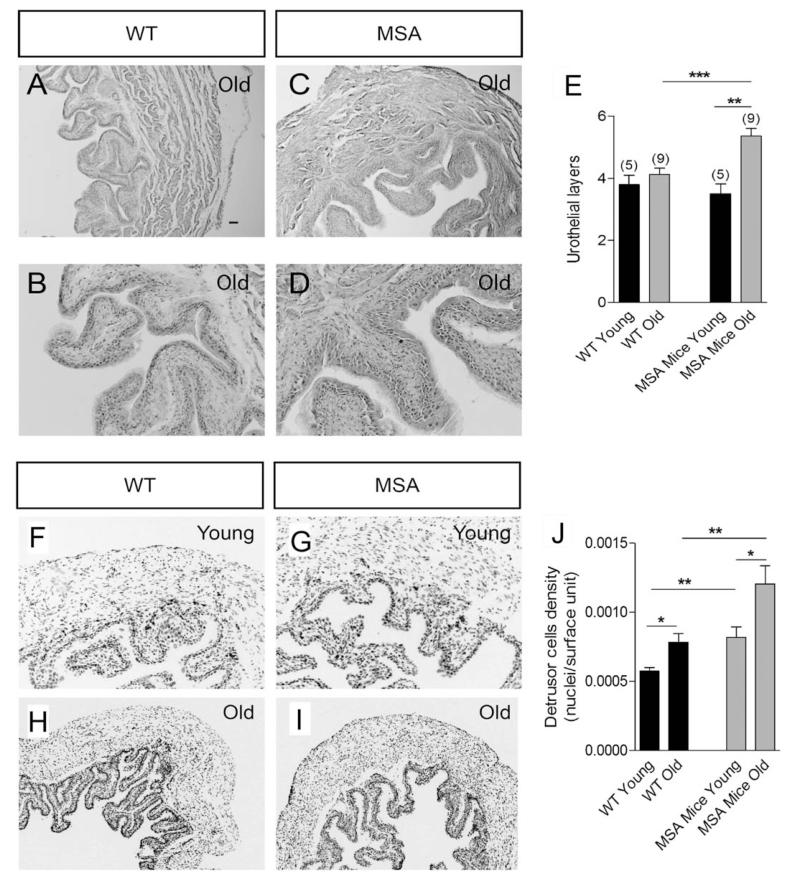

MSA Bladder Cytoarchitecture Is Progressively Modified with Age

H&E staining revealed hypertrophy of the urothelium of MSA mice compared with WT mice at 12 months of age (Fig. 3A–D). The number of urothelial layers was increased by 30% (4.1 ± 0.2 cells in control mice and 5.4 ± 0.2 cells in MSA mice; P < .05; Fig. 3E). However, 2-month-old WT mice and age-matched MSA mice showed no differences in the number of urothelial layers (Fig. 3E). In contrast, the detrusor layers of MSA bladders were thicker with a higher smooth-muscle cell density in both young and old transgenic mice (Fig. 3F–J). These results indicate that bladders from MSA mice may represent structural differences resulting from bladder dysfunction.

FIG. 3.

Bladder cytoarchitecture. A, B, C, D: Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed no drastic differences in the bladder structure between WT and MSA mice. A tendency of hyperplasia of the urothelium in 12-month-old MSA mice compared with age-matched WT mice was noted. E: Morphometric analysis confirmed statistically significant increase in the number of urothelial layers in old MSA mice; however, at 2 months of age (young) WT and MSA mice showed no significant differences in the urothelial structure. F, G, H, I, J: Hoescht staining further revealed increased density of cell nuclei in the bladder walls of MSA mice, both at 2 (young) and at 12 (old) months of age. Scale bar: 100 μm in A, C, E, F; 50 μm in B, D; 200 μm in G, H. Data are mean ± SEM; nyoung = 5, nold = 9; *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

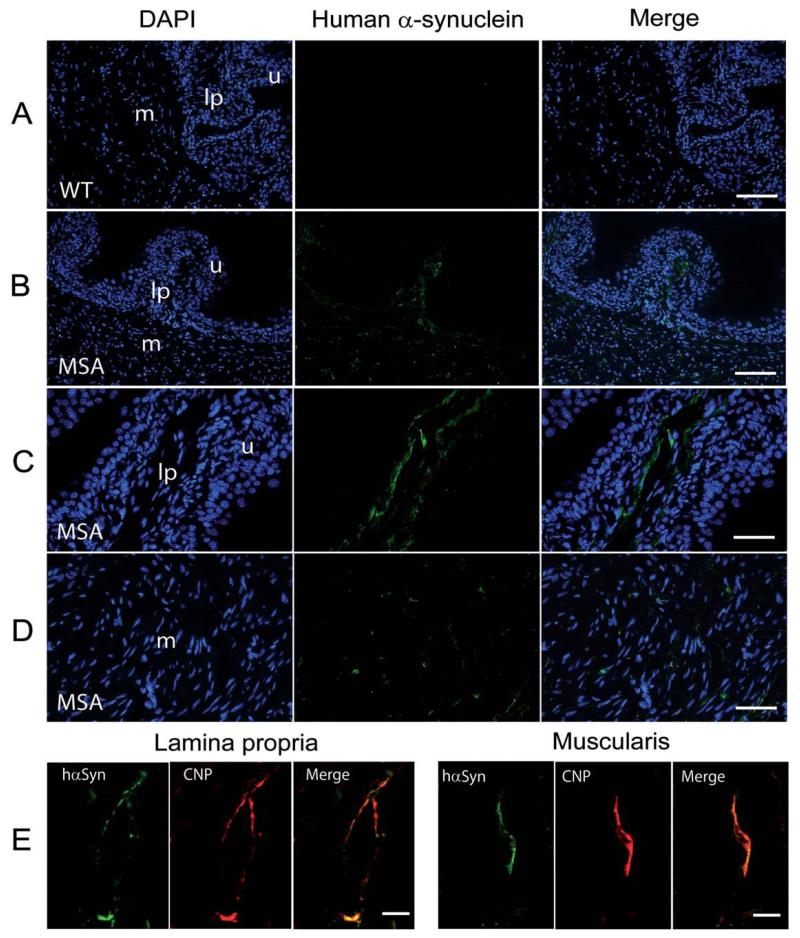

hαSyn immunofluorescent staining of transgenic bladders revealed expression of the transgenic protein in the lamina propria and muscularis in cells with elongated shape and thin processes. This staining pattern was not detectable in WT controls (Fig. 4A–D). Double-labeling identified colocalization of hαSyn and CNP in the lamina propria and muscularis of transgenic urinary bladder (Fig. 4E), suggesting expression of hαSyn in SCs along nerve fibers innervating the bladder wall.

FIG. 4.

Expression of human α-synuclein in the bladder wall of transgenic MSA and wild-type (WT) mice. A: Overview of the bladder wall counter-stained with DAPI showed no human α-synuclein expression in WT mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. B: Overview of the bladder wall counterstained with DAPI showed human α-synuclein expression (green) in transgenic MSA mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. C: At higher magnification the MSA bladder mucosa with the underlying lamina propria showed predominantly fiberlike human α-synuclein-positive structures within the lamina propria. Scale bar, 50 μm. D: At higher magnification the MSA bladder muscularis showed predominantly fiberlike or dotlike human α-synuclein-positive structures. Scale bar, 50 μm. E: Double labeling for human α-synuclein (hαSyn) and CNP (a marker for Schwann cells) identified colocalization of the markers in both lamina propria and muscularis. Scale bar, 10 μm; u, urothelium; lp, lamina propria, m, muscularis.

Neuropathology in Centers of Micturition Control in MSA Mice

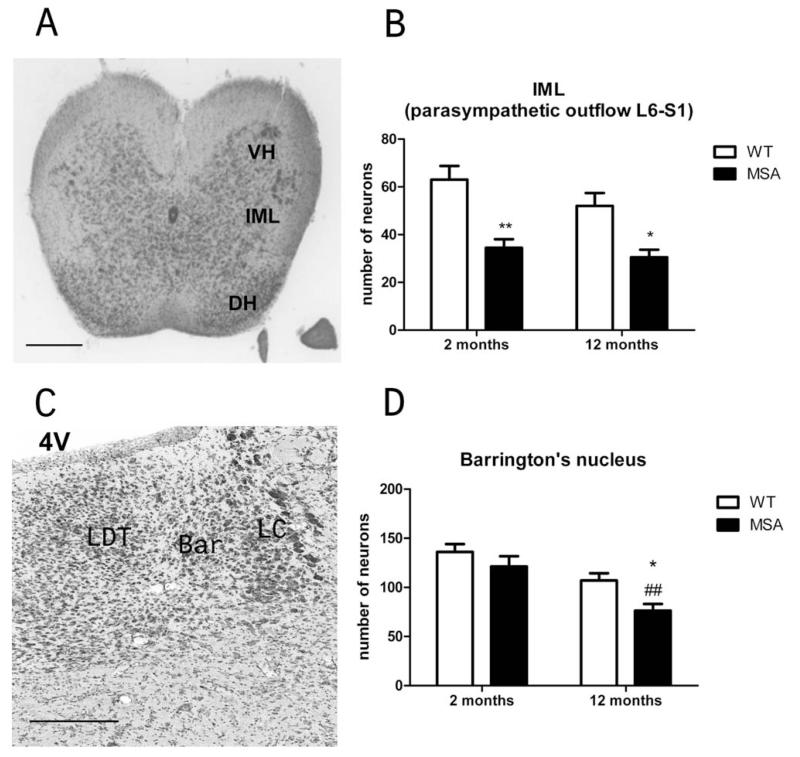

Previously, neuronal loss was reported in regions that participate in the central control of the lower urinary tract (LUT), including Onuf’s nucleus, the locus coeruleus, and the substantia nigra pars compacta in PLP-hαSYN mice.14,15,18 Here we extended this analysis and identified early loss of neurons in the lumbosacral IML at the L6–S1 level of the spinal cord in MSA mice (Fig. 5A,B). To address possible neuropathological correlate of disturbed central coordination control of bladder function, we analyzed Barrington’s nucleus in the brain stem. We detected aggravated degeneration of Barrington’s nucleus in 12-month-old transgenic MSA mice (Fig. 5C,D)

FIG. 5.

Neuropathology of the lumbosacral IML and the Barrington’s nucleus. A: Identification of the IML at the L6–S1 level of the spinal cord in cresyl violet staining according to the atlas of mouse spinal cord.22 Scale bar, 0.5 mm. B: Number of neurons in the IML at the L6–S1 level of the spinal cord was significantly reduced in both 2- and 12-month-old transgenic MSA mice compared with WT age-matched controls. Data are mean ± SEM; in each group, n = 4; *P < .05, **P < .01 C: Identification of the Barrington’s nucleus (Bar) intercalated between the locus coeruleus (LC) and the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT) in cresyl violet staining according to the mouse brain atlas.23 Scale bar, 0.2 mm. D: Number of neurons in Barrington’s nucleus in young MSA mice at 2 months of age was preserved compared with WT age-matched controls. At 12 months of age, old transgenic MSA mice showed significant loss of neurons in Barrington’s nucleus compared with young MSA mice (##P < .01) and compared with age-matched old WT control mice (*P < .5). Data are mean ± SEM; in each group, n = 4.

Discussion

LUT dysfunction is a common nonmotor presentation of MSA that may occur long before the motor syndrome becomes overt.7 LUT dysfunction in MSA may present with urinary incontinence, urgency, increased micturition frequency, and incomplete bladder emptying, resulting in increased postvoid residual urine volume.9 The results of the present study provide the first evidence for modeling MSA-linked bladder dysfunction in a transgenic mouse model featuring GCI pathology.19 We identified that oligodendroglial hαSyn overexpression led to bladder dysfunction, characterized by emptying symptoms related to detrusor contraction inefficiency with indirect evidence of detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia, resulting in increased postvoid residual urine volume. Central nuclei involved in micturition control, including the lumbosacral IML and Barrington’s nucleus, showed progressive neurodegenerative changes, supporting the neurogenic origin of bladder dysfunction in MSA mice.

Previous studies linked oligodendroglial αSyn pathology in PLP-hαSyn mice with microgliosis and selective nigral neurodegeneration related to a mild motor phenotype.14,15 The motor pathology was further extended to SND and OPCA, either through additional oxidative stress or αSyn seeding triggered by transient proteasome inhibition.14,17 However, recent pathological findings reported progressive neuronal loss in nonmotor regions of the CNS of MSA mice relevant to human pathology.18 These findings suggested that the transgenic approach with oligodendroglial αSyn overexpression may go beyond replication of an MSA-like movement disorder and replicate specific nonmotor features of the human disease.

The urinary dysfunction detected in the MSA mice and reported here was not dependent on kidney failure, as suggested by the preserved diuresis volume and the unchanged total number of voiding events over 24 hours. Furthermore, the preserved ex vivo contractility of the bladder wall induced by cholinergic agonists or depolarizing solutions supported the notion that the reported bladder dysfunction was possibly related to changes in the neural control of micturition. According to the observed pathology, we hypothesize that both peripheral and central mechanisms may contribute to the pathogenesis of neurogenic LUT dysfunction in the transgenic MSA model. Finally, the concomitant increase in the amplitude of voiding contractions, the appearance of nonvoiding contractions, and the postvoid residual volume may result from increased spasticity of the pelvic floor and/or from dyssynergia between sphincter relaxation and detrusor contraction.

Central urinary dysfunction in the MSA transgenic model may relate to existing nigral degeneration.14,15 However, LUT dysfunction in MSA mice featuring oli-godendroglial α-synucleinopathy differs from the bladder dysfunction reported in models of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Previous studies in a toxin model of PD indicated that dopaminergic neuronal loss in the SNc may underlie bladder hyperactivity; however, nigral 6-OHDA lesion alone was not sufficient to cause bladder dyssynergia with residual urine after voiding.24–26 Therefore, neurodegeneration and CNS pathology beyond that in the SNc may contribute to the observed LUT dysfunction in MSA mice. Here, we identified neuronal loss in the lumbosacral IML and Barrington’s nucleus (PMC) linked to the oligodendroglial α-synucleinopathy, which together with the previously reported degeneration of Onuf’s nucleus may contribute to neurogenic bladder dysfunction in the MSA transgenic mouse model.

In the current study we identified expression of hαSyn in the wall of the urinary bladder under the control of the PLP promoter. PLP is a myelin-related protein mainly expressed by oligodendroglia but may also be found in peripheral myelin as well as in the cytoplasm of SCs.27 The pattern of distribution of hαSyn and its colocalization with CNP, a common marker for SCs, confirmed that SCs along the fibers innervating the urinary bladder in thelamina propria and muscularis are the ones to bear hαSyn in MSA mice. This peripheral pathology in addition to the central neurodegeneration may contribute to the functional deficiency of the transgenic urinary bladder; however, it is unclear whether the peripheral component induced through the transgenic approach is relevant to the human disease, as to our knowledge no pathological study has analyzed αSyn expression in the urinary bladders of MSA patients. However, an increasing number of reports point toward the involvement of the peripheral nervous system in MSA-linked α-synucleinopathy.28 Moreover, nerve conduction studies identified changes in peripheral conduction velocity, especially relevant in MSA-P,29 that is, the phenotype reproduced by the PLP-hαSyn transgenic mouse.

Intriguingly, urinary bladder dysfunction in transgenic mice with neuronal overexpression of αSyn (PD model)30 differed significantly from that observed in MSA mice with oligodendroglial αSyn expression. Both in PD and MSA transgenic mice, hαSyn was detectable in the bladder wall (in nerve fibers in PD mice but in SCs in MSA mice). However, no general architectural changes were described in the PD model compared with progressive urothelium and detrusor hyperplasia in the MSA model. Furthermore, although PD hαSyn transgenic mice commonly (72%) presented with urinary incontinence, MSA hαSyn transgenic mice showed preserved voiding frequency but increased nonvoiding contractions with indirect evidence of dyssynergia and increased residual postvoid urine volume. Taken together, the comparison between PD and MSA mice with transgenic overexpression of hαSyn suggests different pathogenic mechanisms of LUT dysfunction, which may be of relevance to human PD and MSA.

In conclusion, our study provides the first description of an animal model of MSA-like urinary dysfunction linked to oligodendroglial α-synucleinopathy and presenting with bladder hyperactivity with presumed detrusor/sphincter dyssynergia, increased postvoid residual volume, and morphological bladder wall changes. The observed functional deficits relate to progressive neurodegeneration in micturition control centers in the brains and spinal cords of transgenic MSA mice, resembling the human disease.9,31 At 12 months of age, the transgenic model did not replicate urinary incontinence, a typical sign of the urinary syndrome in MSA31; however, we cannot exclude the appearance of this symptom at a later stage. The clinical relevance of the model supports its applicability as a preclinical tool to study urinary dysfunction related to MSA.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Ion Channel Research Laboratory for the helpful discussions.

Funding agencies: This research work was supported by Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) grants G.0172.03, G.149.03, G0565.07, and G0686.09, Research Council of the KU Leuven grants GOA2004/07 and EF/95/010, an unrestricted educational grant by Astellas (to Dirk De Ridder) and a grant of the Austrian Science Funds (FWF) F4404-B19 (to Gregor K. Wenning and Nadia Stefanova). Mathieu Boudes is a Marie Curie Fellow, and Pieter Uvin is a PhD student of the FWO. Dirk De Ridder is a clinician-fundamental researcher of the FWO Vlaanderen.

Footnotes

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Stefanova N, Bucke P, Duerr S, et al. Multiple system atrophy: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1172–1178. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenning GK, Colosimo C, Geser F, et al. Multiple system atrophy. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71:670–676. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324625.00404.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue M, Yagishita S, Ryo M, et al. The distribution and dynamic density of oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) in multiple system atrophy: a correlation between the density of GCIs and the degree of involvement of striatonigral and olivopontocerebellar systems. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1997;93:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s004010050655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozawa T, Paviour D, Quinn NP, et al. The spectrum of pathological involvement of the striatonigral and olivopontocerebellar systems in multiple system atrophy: clinicopathological correlations. Brain. 2004;127:2657–2671. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliday GM, Holton JL, Revesz T, et al. Neuropathology underlying clinical variability in patients with synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:187–204. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0852-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jecmenica-Lukic M, Poewe W, Tolosa E, et al. Premotor signs and symptoms of multiple system atrophy. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:361–368. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchhof K, Apostolidis AN, Mathias CJ, et al. Erectile and urinary dysfunction may be the presenting features in patients with multiple system atrophy: a retrospective study. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:293–298. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winge K, Fowler CJ. Bladder dysfunction in Parkinsonism: mechanisms, prevalence, symptoms, and management. Mov Disord. 2006;21:737–745. doi: 10.1002/mds.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benarroch EE. Neural control of the bladder: recent advances and neurologic implications. Neurology. 2010;75:1839–1846. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fdabba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stefanova N, Tison F, Reindl M, et al. Animal models of multiple system atrophy. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yazawa I, Giasson BI, Sasaki R, et al. Mouse model of multiple system atrophy alpha-synuclein expression in oligodendrocytes causes glial and neuronal degeneration. Neuron. 2005;45:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shults CW, Rockenstein E, Crews L, et al. Neurological and neurodegenerative alterations in a transgenic mouse model expressing human alpha-synuclein under oligodendrocyte promoter: implications for multiple system atrophy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10689–10699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3527-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefanova N, Reindl M, Neumann M, et al. Oxidative stress in transgenic mice with oligodendroglial alpha-synuclein overexpression replicates the characteristic neuropathology of multiple system atrophy. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:869–876. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62307-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanova N, Reindl M, Neumann M, et al. Microglial activation mediates neurodegeneration related to oligodendroglial alpha-synucleinopathy: Implications for multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2196–2203. doi: 10.1002/mds.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stefanova N, Fellner L, Reindl M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 promotes alpha-synuclein clearance and survival of nigral dopaminergic neurons. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefanova N, Kaufmann WA, Humpel C, et al. Systemic protea-some inhibition triggers neurodegeneration in a transgenic mouse model expressing human alpha-synuclein under oligodendrocyte promoter: implications for multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0977-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stemberger S, Poewe W, Wenning GK, et al. Targeted overexpression of human alpha-synuclein in oligodendroglia induces lesions linked to MSA-like progressive autonomic failure. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahle PJ, Neumann M, Ozmen L, et al. Hyperphosphorylation and insolubility of alpha-synuclein in transgenic mouse oligodendrocytes. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:583–588. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefanova N, Eriksson H, Georgievska B, et al. Myeloperoxidase inhibition ameliorates multiple system atrophy-like degeneration in a transgenic mouse model. Mov Disord. 2010;25:S625. doi: 10.1007/s12640-011-9294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uvin P, Everaerts W, Pinto S, et al. The use of cystometry in small rodents: a study of bladder chemosensation. J Vis Exp. 2012;66:e3869. doi: 10.3791/3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson C, Paxinos G, Kayalioglu G. The Spinal Cord. A Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation Text and Atlas. Academic Press; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soler R, Fullhase C, Santos C, et al. Development of bladder dysfunction in a rat model of dopaminergic brain lesion. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:188–193. doi: 10.1002/nau.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitta T, Matsumoto M, Tanaka H, et al. GABAergic mechanism mediated via D receptors in the rat periaqueductal gray participates in the micturition reflex: an in vivo microdialysis study. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:3216–3225. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshimura N, Kuno S, Chancellor MB, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying bladder hyperactivity in rats with a unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesion of the nigrostriatal pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1425–1432. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garbern JY, Cambi F, Tang XM, et al. Proteolipid protein is necessary in peripheral as well as central myelin. Neuron. 1997;19:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakabayashi K, Mori F, Tanji K, et al. Involvement of the peripheral nervous system in synucleinopathies, tauopathies and other neurodegenerative proteinopathies of the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abele M, Schulz JB, Burk K, et al. Nerve conduction studies in multiple system atrophy. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:221–223. doi: 10.1159/000008179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamill RW, Tompkins JD, Girard BM, et al. Autonomic dysfunction and plasticity in micturition reflexes in human alpha-synuclein mice. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:918–936. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benarroch EE. Brainstem in multiple system atrophy: clinicopathological correlations. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:519–526. doi: 10.1023/A:1025067912199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]