Abstract

Objective:

Aggressive spinal haemangiomas (those with significant osseous expansion/extraosseous extension) represent approximately 1% of spinal haemangiomas and are usually symptomatic. In this study, we correlate imaging findings with presenting symptomatology, review treatment strategies and their outcomes and propose a treatment algorithm.

Methods:

16 patients with aggressive haemangiomas were retrospectively identified from 1995 to 2013. Imaging was assessed for size, location, CT/MR characteristics, osseous expansion and extraosseous extension. Presenting symptoms, management and outcomes were reviewed.

Results:

Median patient age was 52 years. Median size was 4.5 cm. Lumbar spine was the commonest location (n = 8), followed by thoracic spine (n = 7) and sacrum (n = 2); one case involved the lumbosacral junction. 12 haemangiomas had osseous expansion; 13 had extraosseous extension [epidural (n = 11), pre-vertebral/paravertebral (n = 10) and foraminal (n = 6)]. On CT, 11 had accentuated trabeculae and 5 showed lysis. On MRI, eight were T1 hyperintense, six were T1 hypointense and all were T2 hyperintense. 11 symptomatic patients underwent treatment: chemical ablation (n = 6), angioembolization (n = 3, 2 had subsequent surgery), radiotherapy (n = 2, 1 primary and 1 adjuvant) and surgery (n = 4). Median follow-up was 20 months. Four of six patients managed only by percutaneous methods had symptom resolution. Three of four patients requiring surgery had symptom resolution.

Conclusion:

Aggressive haemangiomas cause significant morbidity. Treatment is multidisciplinary, with surgery reserved for large lesions and those with focal neurological signs. Minimally invasive procedures may be successful in smaller lesions.

Advances in knowledge:

Aggressive haemangiomas are rare, but knowledge of their imaging features and treatment strategies enhances the radiologist's role in their management.

INTRODUCTION

Vertebral haemangiomas are the most common benign angiomatous lesions involving the spine with an estimated incidence of 10–12% and most commonly affect the thoracic spine.1–3 Histologically, these lesions are composed of fully developed adult blood vessels with slow flowing, dilated venous channels surrounded by fat, infiltrating the medullary cavity.4–6 Despite recommendations terming these lesions' venous malformations by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies, the term “vertebral haemangioma” has persisted throughout the literature, and these lesions will be referred to as “haemangiomas” throughout this article for consistency.

While the majority of vertebral haemangiomas are asymptomatic and incidentally discovered on CT or MR evaluation of the spine, they may become symptomatic owing to pathologic fracture, osseous expansion and/or extraosseous extension, resulting in mass effect upon adjacent neural structures (spinal cord or nerve roots).1,2,7,8 The term aggressive haemangioma refers to haemangiomas with extraosseous extension or significant osseous expansion and accounts for approximately 1% of spinal haemangiomas.9,10 While uncommon, they may present acutely with back pain, radiculopathy or myelopathy, warranting emergent evaluation. These have an increased incidence during pregnancy with the potential for rapid symptom progression to myelopathy or cauda equina syndrome owing to epidural mass effect.7,10 We analysed the outcome of patients with aggressive haemangiomas, treated at University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, over an 18-year period, with respect to their clinical presentation, imaging findings, treatments performed and propose a potential treatment algorithm for these patients.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Following the approval from University of Pennsylvania institutional review board, we retrospectively reviewed our database from January 1995 to February 2013 and identified 16 patients (5 males and 11 females) with 16 aggressive haemangiomas. CT and MRI data in 14 patients was reviewed for the following criteria: vertebral level (cervical, thoracic, lumbar or sacral spine), vertebral location (vertebral body, posterior elements or both), lesion size, osseous expansion, extraosseous extension (epidural, pre-vertebral/paravertebral and/or foraminal), internal architecture on CT, and MRI characteristics on T1 weighted, T2 weighted (including chemical fat-suppressed T2 and short tau inversion-recovery sequences) and post-contrast T1 weighted sequences. In two patients, imaging pre-dated our picture archiving and communication system, and cross-sectional imaging could not be reviewed. Electronic medical records were reviewed to correlate presenting symptomatology with imaging findings. Each patient's management and clinical outcome were assessed.

RESULTS

Imaging characteristics

The 16 patients in our study had a median age of 52 years (range, 23–72 years). The aggressive haemangiomas were located in the lumbar spine (n = 8), thoracic spine (n = 7) and the sacrum (n = 2); one aggressive haemangioma was centred in the sacrum but involved L5 posterior elements as well (L5–S2). Median size of these haemangiomas was 4.5 cm (range, 2.1–12.4 cm). Lesions tended to be larger in the sacrum (mean size 8.3 cm), smaller within the lumbar spine (mean size 5.4 cm) and the smallest in the thoracic spine (mean size 3.6 cm). Within the involved vertebra, lesions were present in the vertebral body (n = 16), posterior elements (n = 9) and diffusely present throughout the vertebrae (n = 3). Isolated involvement of the posterior elements was not seen. Evaluation of CT images (n = 13) showed accentuation of trabecular markings in 10 cases (Figure 1a), and areas of lysis were present in 5 cases (Figure 2a). Review of MR studies (n = 13) showed T1 hyperintensity associated with the haemangioma relative to the marrow in eight cases and T1 hypointensity in six cases (Figure 3a). T2 weighted images showed hyperintensity of the haemangiomas relative to marrow in all cases (Figure 3b). 12 were associated with osseous expansion (Figure 1a). Extraosseous extension was present in 13 patients. Extension into the epidural spinal canal was present in 11 patients (Figure 4a,b), and extension into the pre-vertebral or paravertebral (Figure 1c) spaces was present in 10 patients. In six cases, epidural and paravertebral extraosseous extension were both present. Foraminal extension with narrowing was present in six cases including both cases involving the sacrum (Figure 2b). When present, extraosseous soft tissue was T1 hypointense/T2 hyperintense and enhanced similar to the vertebral component of the haemangioma (Figure 3a–c). In eight patients with epidural disease, there was narrowing of the spinal canal with median stenosis of 52% (range, 19–84%). Table 1 summarizes these results.

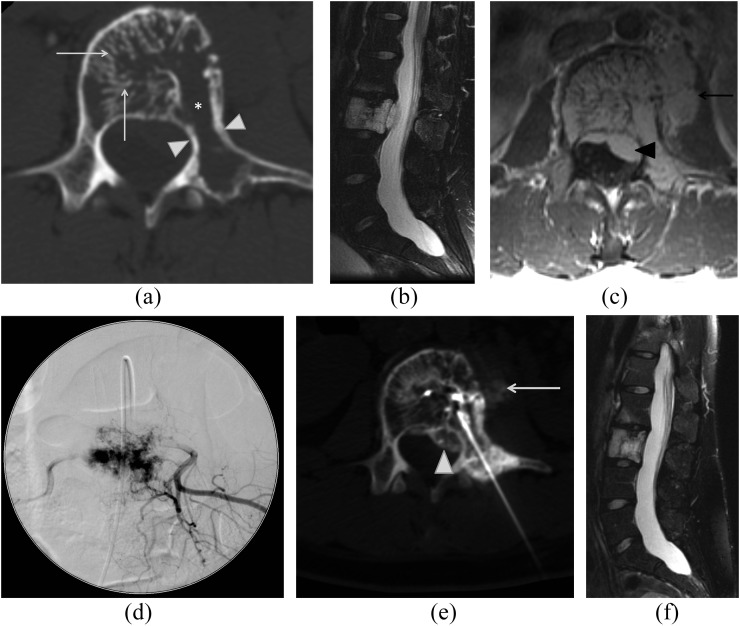

Figure 1.

A 27-year-old female with back pain with an aggressive L3 haemangioma. Axial CT image (a) of L3 shows accentuation of trabecular markings within the vertebral body (arrows), areas of lysis (asterisk) and osseous expansion of the vertebral body extending into the left pedicle and transverse process (white arrowheads). Fat-suppressed sagittal T2 weighted (b) and axial T1 weighted post-contrast (c) images show diffuse abnormal marrow signal throughout the L3 vertebral body with prominent epidural (black arrowhead) and pre-vertebral (black arrow) components. Spot image (d) from subselective angiography of the L3 lumbar vertebral artery demonstrates prominent accumulation of contrast in the L3 during the capillary phase of injection corresponding to the patient's haemangioma. This was subsequently treated with particulate agent embolization. Axial CT image (e) demonstrates transpedicular approach for subsequent absolute alcohol sclerosis. Both the epidural (white arrowhead) and pre-vertebral (white arrow) components are demonstrated during injection of contrast through the intraosseous needle confirming appropriate position. Follow-up sagittal fat-suppressed T2 weighted image of the lumbar spine (f) demonstrates resolution of the extraosseous component of the haemangioma.

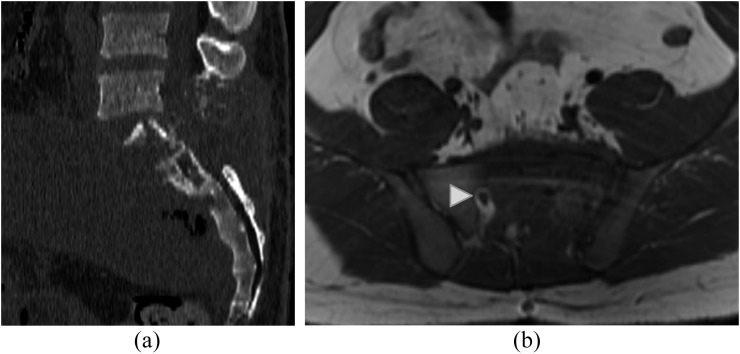

Figure 2.

A 24-year-old male with extensive lumbosacral aggressive haemangioma. Sagittal CT image (a) of the lumbosacral spine demonstrates extensive lysis of S1 vertebral body and posterior elements as well as posterior elements of L5 with prominent soft-tissue component present. Axial T1 weighted image (b) demonstrates diffuse abnormal marrow signal in the left hemisacrum with obliteration of S1/S2 foramen on the left. The right S1/S2 foramen appears normal (white arrowhead). This was proven to be an aggressive haemangioma following resection.

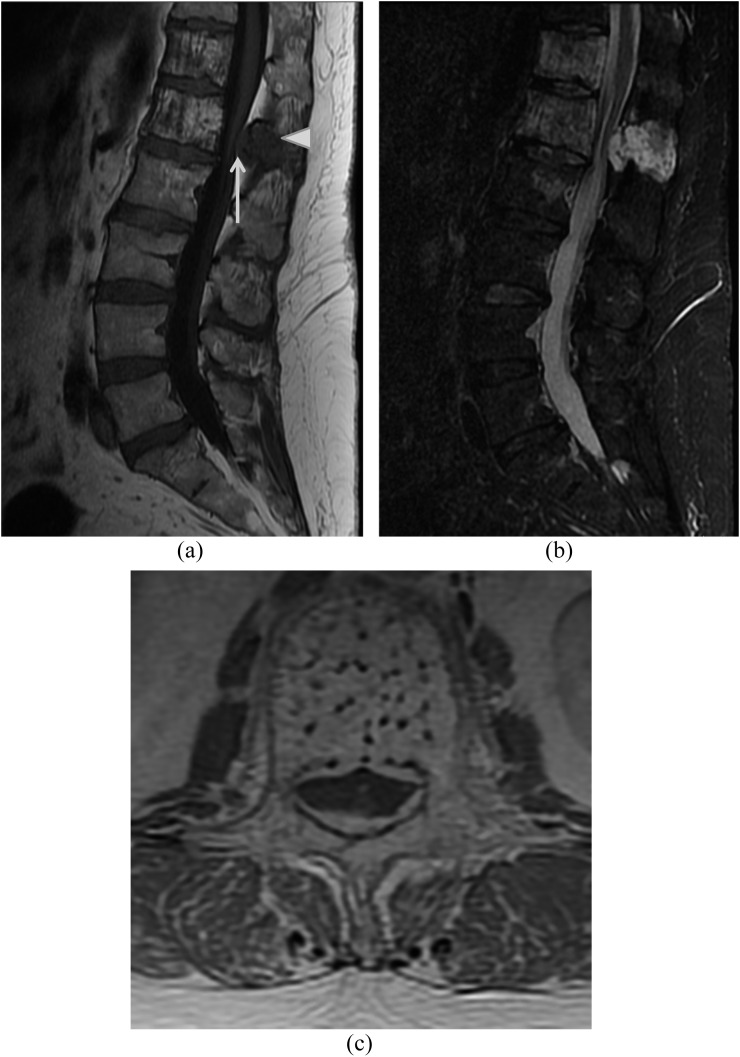

Figure 3.

A 55-year-old female with back pain and right lower extremity radiculopathy due to an aggressive L1 haemangioma. Sagittal T1 (a) and sagittal short tau inversion-recovery (b) images show multiple haemangiomas within the imaged thoracolumbar spine with the largest haemangioma at L1 with prominent epidural component. Note that while there is typical T1 hyperintense appearance of the vertebral body marrow, there is hypointense appearance of the imaged marrow of the posterior elements of L1 (white arrowhead), an atypical imaging feature and of the epidural soft tissue (white arrow). Post-contrast axial (c) image highlights the coarsened appearing trabeculae and the prominent epidural component.

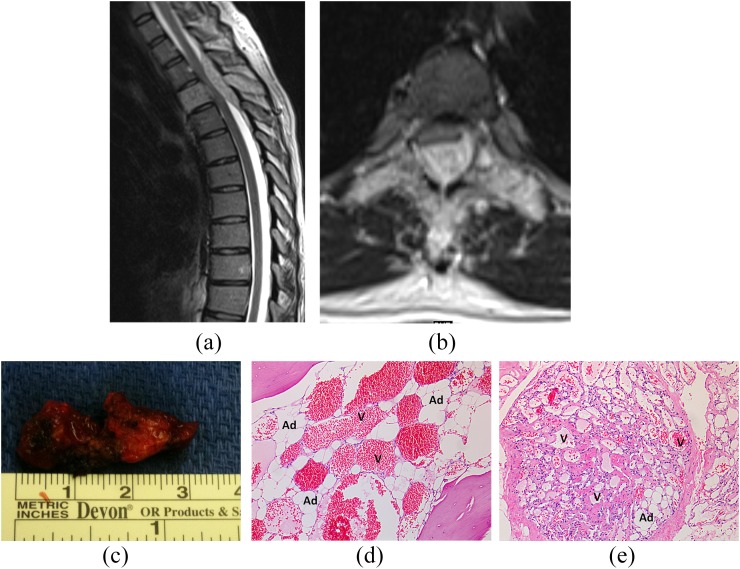

Figure 4.

A 36-year-old pregnant female with subacute, progressive myelopathy due to an aggressive T3 haemangioma. Sagittal T2 weighted (a) and axial T2 weighted (b) images demonstrate diffuse abnormal hyperintense appearance of the T3 vertebra with prominent epidural soft tissue with resultant marked spinal canal stenosis and mass effect on the cord. There is subtle abnormal T2 prolongation of the cord. Gross specimen (c) of patient's resected aggressive haemangioma following decompressive thoracic laminectomies demonstrates engorged appearance of the haemangioma, reflective of its vascularity. ×10 view of haematoxylin and eosin stained sections from the patient's T3 lamina (d) and epidural tissues (e) demonstrate both the vascular channels (V) and adipocytes (Ad) associated with haemangiomas.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and imaging features

| Patient | Age (years)/sex | Vertebral level | Vertebral location |

Size (cm) | CT features |

MR marrow features |

Extraosseous involvement |

Osseous expansion | Epidural canal stenosis (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VB | PE | D | Coarsened trabeculae | Lysis | T1 | T2 | E | Fo | P | ||||||

| 1 | 23/M | L5, S1–S2 | + | + | + | 12.4 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 75 |

| 2 | 24/M | L1 | + | − | − | 2.6 | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | 54 |

| 3 | 27/F | L3 | + | + | − | 7.1 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 52 |

| 4 | 33/F (P) | T5 | + | − | − | 4.6 | NP | NP | + | + | + | − | + | + | 20 |

| 5 | 36/F (P) | T3 | + | + | + | 6.2 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | 73 |

| 6 | 46/F | T1 | + | − | − | 1.7 | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | – |

| 7 | 51/F | S3–S4 | + | + | − | 4.2 | NP | NP | + | + | + | + | + | + | 50 |

| 8 | 53/F | L5 | + | − | − | 4.4 | + | + | NP | NP | + | − | − | + | 27 |

| 9 | 55/F | L1 | + | + | + | 7.7 | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | 57 |

| 10 | 58/F | T5 | + | − | − | 2.5 | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | – |

| 11 | 62/F | T2 | + | + | − | 4.3 | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | – |

| 12 | 63/M | L4 | + | + | − | 8.0 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 84 |

| 13 | 65/F | L4 | + | − | − | 4.8 | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | 37 |

| 14 | 72/F | T10 | + | + | − | 2.1 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | 19 |

| 15 | 73/F | L1 | + | − | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | 74/F | T8 | + | + | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

+, present; −, absent; D, diffuse; E, epidural; F, female; Fo, foraminal; M, male; N/A, measurements unavailable as imaging pre-dated picture archiving and communication system implementation; NP, examination not performed; P, pre-vertebral or paravertebral; (P), pregnant at symptom onset; PE, posterior elements; T1, hyperintense to marrow on T1 weighted imaging; T2, hyperintense to marrow on T2 weighted imaging; VB, vertebral body.

Clinical characteristics

Of the 16 patients, 5 were asymptomatic and 11 were symptomatic. The most common presenting symptoms were back pain (n = 8) and localizing neurological symptoms [n = 7: radiculopathy (n = 5), neurogenic claudication (n = 1) and myelopathy (n = 1)]. All patients with neurological symptoms demonstrated epidural soft-tissue extension. Two patients developed their symptoms during their pregnancies.

Procedures were performed in 11 patients, including all 6 patients with localizing neurological symptoms. Transarterial embolization was performed in three patients utilizing polyvinyl alcohol particles (Figure 1d): two patients subsequently had surgical resection of their haemangiomas and spinal fusion, and the third patient subsequently had CT-guided ethanol sclerosis of their haemangioma. CT-guided ethanol sclerosis of vertebral body haemangiomas was performed in six patients (three with back pain, two with radiculopathy and back pain and one with isolated radiculopathy) (Figure 1e,f); a total of eight procedures were performed, as two patients required repeat procedures. Four patients required surgical resection of their haemangiomas (one patient with subacute myelopathy, one patient with neurogenic claudication and two patients with back pain and radiculopathy). Two patients had decompressive laminectomies and resection of their haemangiomas (Figure 4c–e). In another patient with an aggressive L1 haemangioma, corpectomy and thoracolumbar fusion was initially performed; however, a recurrence necessitated repeat transarterial embolization and re-resection. In a patient with an extensive aggressive sacral haemangioma with foraminal extension and neural compression, repeat transarterial embolizations and resections were performed; adjuvant radiation therapy was given for persistent lower extremity radiculopathy and back pain due to their haemangioma. One patient had primary radiation therapy for an L5 haemangioma; 2 years later, an acute compression fracture developed which was managed by vertebral augmentation, primarily for pain control.

Median follow-up of the 16 patients was 20 months (range, 1–204 months). Of the four patients who underwent surgery, two required repeat surgeries owing to the recurrence of their haemangiomas. Of the four patients requiring surgery, one has persistent neurological symptoms (neurogenic claudication). Of the six patients treated with alcohol sclerosis, four reported relief of back pain with resolution of radiculopathy in one patient; two patients have continued back pain. The patient who underwent primary radiation of her L5 aggressive haemangioma and subsequent vertebral augmentation has remained clinically stable and required no further intervention. The remaining five patients not requiring intervention have remained clinically stable without development of localizing neurological symptoms or back pain. Table 2 summarizes the presenting symptoms, interventions performed, clinical courses and outcomes of our patients.

Table 2.

Clinical findings, interventions and patient outcomes

| Patient | Vertebral level | Symptoms | Treatment |

Follow-up (months) | Clinical course/outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sclerosis | Embo | RadTx | Srgy | Obs | |||||

| 1 | L5, S1–S2 | Back pain, radiculopathy | − | + | + | + | − | 12 | Embo followed by L3–S1 fusion. Following initial fusion, repeated resection and iliolumbar fusion performed with adjuvant RadTx. No back pain or radiculopathy on follow-up |

| 2 | L1 | Neurogenic claudication | − | − | − | + | − | 13 | L1–L2 laminectomies. Post-operative course complicated by parapsoas abscess treated by percutaneous drainage and antibiotic course. Persistent neurogenic claudication |

| 3 | L3 | Back pain | + | + | − | − | − | 96 | Embo and sclerosis. No neurologic deficits and no reported back pain on follow-up |

| 4 | T5 | Left scapular neck and back pain | + | − | − | − | − | 9 | Transient back pain relief following ethanol sclerosis but with persistent pain on follow-up |

| 5 | T3 | Subacute progressive myelopathy | − | − | − | + | − | 12 | T1–T4 laminectomies. Myelopathy resolved |

| 6 | T1 | Headache and neck pain | − | − | − | − | + | 16 | Stable. Continued neck pain and headache |

| 7 | S3–S4 | None | − | − | − | − | + | 10 | Stable. No reported symptoms |

| 8 | L5 | Back pain | − | − | + | − | − | 48 | Pain relief after RadTx. Recurrent pain due to L5 compression fracture. Symptom relief following vertebroplasty |

| 9 | L1 | Back pain and radiculopathy | + | − | − | − | − | 14 | Radiculopathy resolved. Persistent back pain |

| 10 | T5 | Back pain | + | − | − | − | − | 1 | Pain markedly diminished following sclerosis |

| 11 | T2 | None | − | − | − | − | + | 20 | Stable. No reported symptoms |

| 12 | L4 | Radiculopathy | + | − | − | − | − | 64 | Sclerosis performed twice due to persistent radiculopathy. No longer symptomatic |

| 13 | L4 | Back pain and radiculopathy | + | − | − | − | − | 37 | No reported back pain/radiculopathy following sclerosis |

| 14 | T10 | None | − | − | − | − | + | 62 | Stable. No reported symptoms |

| 15 | L1 | Back pain and radiculopathy | − | + | − | + | − | 120 | L1 corpectomy with T12–L2 fusion. Recurrence prompting embo followed by L1 re-resection, L1 transpedicular decompression and fusion extension from T11–L3. No recurrence to date |

| 16 | T8 | None | − | − | − | − | + | 204 | Stable. No reported symptoms |

+, intervention pursued; −, intervention not pursued; Embo, transarterial embolization; F, female; M, male; Obs, observation; RadTx, radiation therapy; Sclerosis, ethanol sclerosis; Srgy, surgery.

DISCUSSION

Vertebral haemangiomas are histologically benign venous malformations characterized by prominent slow flow intraosseous abnormal venous channels with flattened endothelium and absence of smooth muscle.3,6 Characteristic findings on radiography include coarsened and thickened appearance of the vertical bony trabeculae of the affected vertebrae.11 On CT imaging, typical haemangiomas show characteristic thickened trabeculae and interposed fat yielding a “honeycomb” appearance on axial images and a striated appearance on sagittal and coronal reconstructions, akin to their classical appearance on conventional radiography.11,12 Typical MRI findings of vertebral haemangiomas include T1 and T2 hyperintensity on non-contrast imaging.13,14 While the hyperintense signal on T2 weighted imaging may reflect a combination of T2 properties of fat, vascularity and/or oedema,14 hyperintense signal relative to marrow on T1 weighted images may relate to increased lipid components associated with these lesions relative to adjacent marrow elements.14 Occasionally, haemangiomas may appear isointense or hypointense to marrow on T1 weighted sequences as in our series, reflecting relatively decreased lipid content associated with the haemangioma, and the term atypical haemangioma has been applied to these lesions when other reassuring imaging characteristics (e.g., coarsened vertebral trabeculae) are present.14

Aggressive haemangiomas describe haemangiomas with osseous expansion and/or extraosseous soft-tissue extension contiguous with the osseous haemangioma.9,10 While the extraosseous component may be hypointense relative to marrow on non-contrast T1 weighted sequences, uniform enhancement and T2 hyperintensity of osseous and extraosseous components is typical (Figure 3a–c).3,14 Differential diagnosis of aggressive haemangiomas includes conditions such as malignancy and infection. Homogeneous soft-tissue enhancement, non-aggressive osseous features (such as absence of aggressive osteolysis or aggressive periosteal reaction) and accompanying typical imaging characteristics (i.e. trabecular coarsening, T1 hyperintense marrow) help in distinguishing aggressive haemangioma from these imaging mimics. Aggressive haemangiomas may become symptomatic. Pain attributed to aggressive haemangiomas may reflect sequelae from osseous expansion or a complicating compression fracture.2,7 Extraosseous extension may result in compression of the spinal cord and/or nerve roots which may manifest as myelopathy or radiculopathy.2,7

When symptomatic, management of aggressive haemangiomas frequently requires surgery often with endovascular embolization prior to surgery to minimize intraoperative blood loss, or these lesions can be managed with minimally invasive image-guided techniques to include chemical (absolute alcohol) ablation, transarterial embolization or radiotherapy. Surgical resection of aggressive haemangiomas is usually pursued with large lesions and those with focal neurologic deficits.7,10 The appropriate surgical procedure depends on multiple factors including lesion location within the spine, location within the affected vertebra (isolated to vertebral body, posterior elements or diffuse) and acuity of symptoms.

Endovascular embolization is almost always performed at our institution in the pre-operative setting to reduce intraoperative blood loss in patients with neurologic deficits or focal symptoms from their aggressive haemangiomas.15–17 Infrequently, transarterial embolization may be performed in combination with image-guided chemical ablation. While embolization has been described utilizing particulate agents, detachable coils and polymerizing liquid agents, we most commonly employ particulate agents (polyvinyl alcohol particles, 150–250 mm) via a transarterial approach.9,15,16

The goal of absolute alcohol sclerosis (chemical ablation) is to dehydrate the symptomatic portion of a haemangioma, and it is an effective treatment, commonly performed via a transpedicular or parapedicular approach.18,19 Chemical ablation of haemangiomas is performed with optimal outcomes in patients with back pain without focal neurological signs or symptoms. Relief of pain occurs in up to 70–90% of patients, and there are isolated reports of alcohol ablation utilized as a primary intervention to manage patients with radiculopathy or myelopathy.18,19 Vertebral body compression fractures are the most common complication of this procedure and may be addressed by vertebral augmentation (i.e. vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty).20 There are rare reports of neurological complications following sclerosing therapy such as Brown–Sequard syndrome.21

Radiotherapy has been used successfully to treat symptomatic vertebral body haemangiomas as they are radiation sensitive.7,22 Radiotherapy may be performed alone as was performed in one of our cases or in concert with other therapies to treat pain as well as neurological symptoms. With the advent of endovascular embolization to minimize intraoperative blood loss, surgical treatment of aggressive haemangiomas causing neurologic deficits has been advocated over primary radiotherapy. Surgery allows biomechanical stability, immediate decompression of neural contents, and eliminates the risks of osteonecrosis and skin ulceration associated with radiation therapy.7

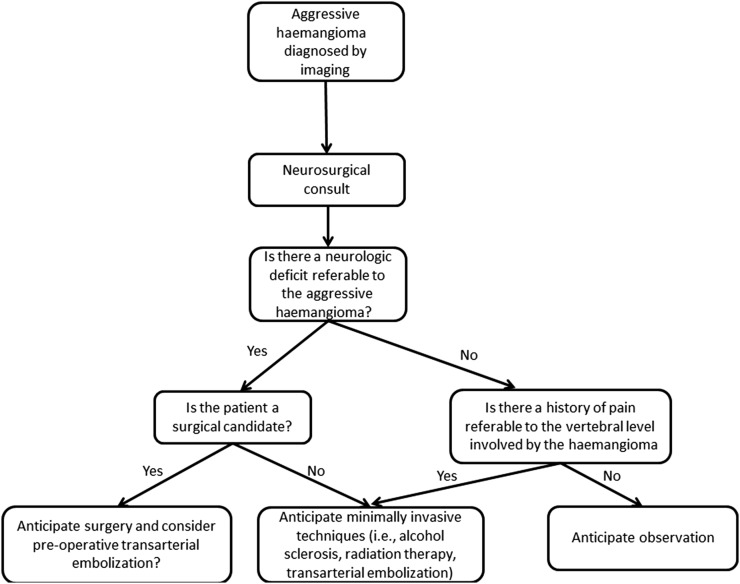

Realizing that a larger symptomatic, patient population (i.e. from a multicentric study of aggressive haemangiomas) could clarify optimal clinical management, we propose the following treatment algorithm (Figure 5). Neurosurgical consultation in the setting of aggressive haemangiomas, especially in the setting of neurologic deficits, is essential. For patients undergoing definitive surgical resection, endovascular embolization should be considered to minimize intraoperative blood loss. If surgery is not contemplated as the primary treatment (often in the setting of isolated back pain or comorbidities precluding surgery), other minimally invasive management options such as image-guided alcohol sclerosis, transarterial embolization and/or radiation therapy can be performed. Our experience with aggressive haemangiomas with pre-vertebral/paravertebral extraosseous extension or those without localizing neurological symptoms suggests that these patients may be managed conservatively with pain medication or minimally invasive image-guided interventions.

Figure 5.

Proposed treatment algorithm for aggressive haemangiomas.

CONCLUSION

Aggressive spinal haemangiomas, while histopathologically benign, can cause significant morbidity owing to mass effect from marked expansion or extraosseous extension. It is paramount that radiologists recognize the imaging features of aggressive haemangiomas and assess for mass effect on neural elements to expedite appropriate clinical management. Minimally invasive procedures (i.e., ethanol ablation) may be appropriate for a subset of patients with isolated back pain, radiculopathy or comorbidities precluding definitive surgery; however, surgery frequently with pre-operative embolization is optimal for patients with large lesions and/or progressive neurologic deficits (especially myelopathy). The treatment of aggressive haemangiomas requires a multidisciplinary approach.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The views and opinions expressed in this publication/presentation are those of the author(s) and do not reflect official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or US Government.

Contributor Information

Francis J Cloran, Email: cloranf@gmail.com.

Bryan A Pukenas, Email: bryan.pukenas@uphs.upenn.edu.

Laurie A Loevner, Email: laurie.loevner@uphs.upenn.edu.

Christopher Aquino, Email: Christopher.aquino@gmail.com.

James Schuster, Email: james.schuster@uphs.upenn.edu.

Suyash Mohan, Email: suyash.mohan@uphs.upenn.edu.

FUNDING

There was no external funding for this research. All research was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania utilizing institutional resources.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dagi TF, Schmidek HH. Vascular tumors of the spine. In: Sundaresan N, Schmidek HH, Schiller AL, et al. , eds. Tumors of the spine: diagnosis and clinical management. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co.; 1990. pp. 181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox MW, Onofrio BM. The natural history and management of symptomatic and asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. J Neurosurg 1993; 78: 36–45. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphey MD, Fairbairn KJ, Parman LM, Baxter KG, Parsa MB, Smith WS. Musculoskeletal angiomatous lesions: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 1995; 15: 893–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander J, Meir A, Vrodos N, Yau YH. Vertebral hemangioma: an important differential in the evaluation of locally aggressive spinal lesions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: E917–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yousem DM, Grossman RI. Nondegenerative disease of the spine. In: Yousem DM, Grossman RI, eds. Neuroradiology: the requisites. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc.; 2010. pp. 543–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe LH, Marchant TC, Rivard DC, Scherbel AJ. Vascular malformations: classification and terminology the radiologist needs to know. Semin Roentgenol 2012; 47: 106–17. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta FL, Jr, Sanai N, Chi JH, Dowd CF, Chin C, Tihan T, et al. Comprehensive management of symptomatic and aggressive vertebral hemangiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2008; 19: 17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen JP, Djindjian M, Gaston A. Vertebral hemangiomas presenting with neurologic symptoms. Surg Neurol 1987; 27: 391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurley MC, Gross BA, Surdell D, Shaibani A, Muro K, Mitchell CM, et al. Preoperative Onyx embolization of aggressive vertebral hemangiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 1095–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastushyn AI, Slin'ko EI, Mirzoyeva GM. Vertebral hemangiomas: diagnosis, management, natural history and clinicopathological correlates in 86 patients. Surg Neurol 1998; 50: 535–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perman F. On hemangiomata in the spinal column. Acta Chir Scand 1926; 61: 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price HI, Batnitzky S. Computed tomographic findings in benign diseases of the vertebral column. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 1985; 24: 39–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Modic MT, Carter JR, Mapstone T, Dengel FH. Vertebral hemangiomas: MR imaging. Radiology 1987; 165: 165–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.165.1.3628764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudrez V, Galant C, Vande Berg BC. Benign vertebral hemangioma: MR-histological correlation. Skeletal Radiol 2001; 30: 442–6. doi: 10.1007/s0025610300442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkefeld J, Scale D, Kirchner J. Hypervascular spinal tumors: influence of the embolization technique on perioperative hemorrhage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 757–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith TP, Koci T, Mehringer CM, Tsai FY, Fraser KW, Dowd CF, et al. Transarterial embolization of vertebral hemangioma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1993; 4: 681–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raco A, Ciappetta P, Artico M, Salvati M, Guidetti G, Guglielmi G. Vertebral hemangiomas with cord compression: the role of embolization in five cases. Surg Neurol 1990; 34: 164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doppman JL, Oldfield EH, Heiss JD. Symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas: treatment by means of direct intralesional injection of ethanol. Radiology 2000; 214: 341–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe46341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goyal M, Mishra NK, Sharma A, Gaikwad SB, Mohanty BK, Sharma S, et al. Alcohol ablation of symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 1091–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, Zhang CL, Tang TS. Cement vertebroplasty combined with ethanol injection in the treatment of vertebral hemangioma. Chin Med J 2007; 120: 1136–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemeyer T, McClellan J, Webb J, Jaspan T, Ramli N. Brown-Sequard syndrome after management of vertebral hemangioma with intralesional alcohol: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999; 24: 1845–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heyd R, Seegenschmiedt MH, Rades D, Winkler C, Eich HT, Bruns F, et al. Radiotherapy for symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas: results of a multicenter study and literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 77: 217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]