Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether visually stratified CT findings and pulmonary function variables are helpful in predicting mortality in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE).

Methods:

We retrospectively identified 113 patients with CPFE who underwent high-resolution CT between January 2004 and December 2009. The extent of emphysema and fibrosis on CT was visually assessed using a 6- or 5-point scale, respectively. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional regression analyses were performed to determine the prognostic value of visually stratified CT findings and pulmonary function variables in patients with CPFE. Differences in 5-year survival rates in patients with CPFE according to the extent of honeycombing were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results:

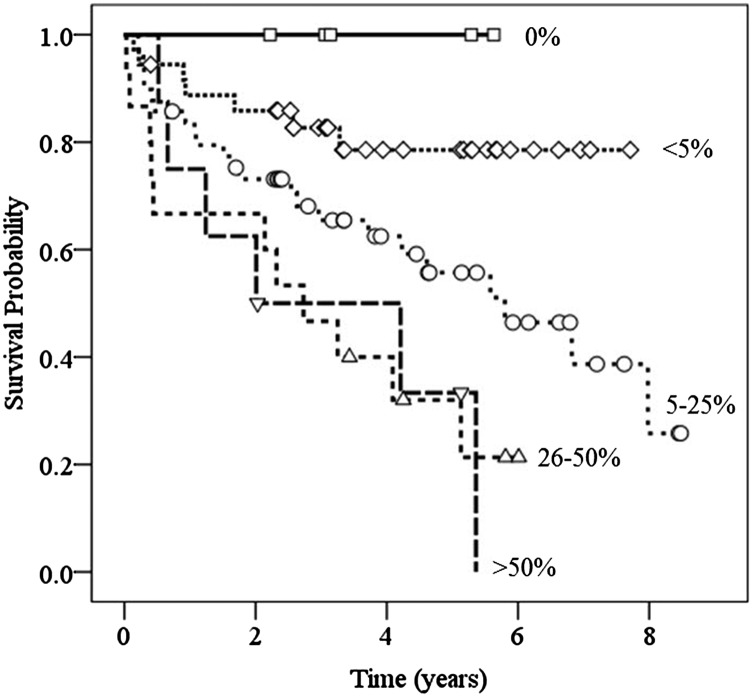

An increase in the extent of visually stratified honeycombing on CT [hazard ratio (HR), 1.95; p = 0.018; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.12–3.39] and reduced diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (HR, 0.97; p = 0.017; 95% CI, 0.94–0.99) were independently associated with increased mortality. In patients with CPFE, the 5-year survival rate was 78.5% for <5% honeycombing, 55.7% for 5–25% honeycombing, 32% for 26–50% honeycombing and 33.3% for >50% honeycombing on CT.

Conclusion:

The >50% honeycombing on CT and reduced DLCO are important prognostic factors in CPFE.

Advances in knowledge:

Visual estimation of honeycombing extent on CT can help in the prediction of prognosis in CPFE.

INTRODUCTION

Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) has received increased attention as a distinct disease entity or syndrome characterized by two pathological processes of the lung—upper lobe emphysema and lower lobe diffuse parenchymal lung disease with fibrosis.1–3 There is a general consensus among researchers regarding certain characteristics and/or risk factors for CPFE, including male sex, cigarette smoking, near-normal spirometry, severe impairment of gas exchange, pulmonary hypertension and poor survival.2 However, until now, there are differences in opinion regarding mortality in CPFE compared with that of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) without emphysema and prognostic factors for CPFE with various physiological variables that have been identified as potential prognostic factors.4–12

From a radiological perspective, CPFE is an interesting disease entity or syndrome because CT can easily detect and evaluate both of the pathological processes of CPFE. In the literature on pulmonary emphysema or interstitial lung disease (ILD), radiologists generally quantified CPFE extent by visual assessment or quantitative indices using semiautomated commercialized or in-house software (Pulmonary Workstation; Vida Diagnostics, Coralville, IA).13 Disease extent on high-resolution CT (HRCT) is used to quantify serial changes in disease progression, thus serving as a prognostic determinant of fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP).14,15 Therefore, we hypothesized that extent of the two pathological processes, upper lobe emphysema and lower lobe diffuse parenchymal lung disease with fibrosis, on HRCT in patients with CPFE may provide a tool for predicting outcome in CPFE. In everyday practice, visual stratification of CT findings using a 5-point or 6-point scale is a fast and easy way to quantify CT abnormalities. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine whether visually stratified CT findings and pulmonary function variables are helpful in predicting mortality in patients with CPFE.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patient selection

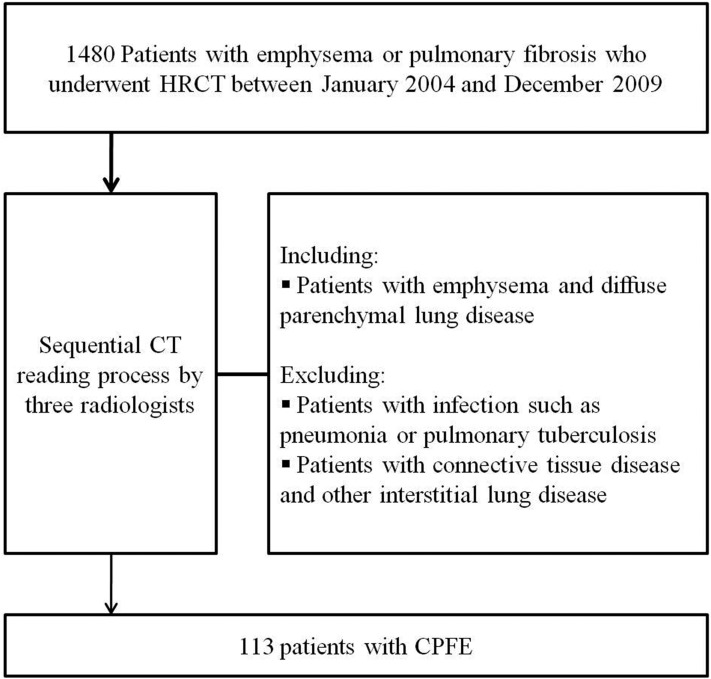

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board (Chonbuk National University Hospital), which waived the need for informed consent. Subject selection is outlined in Figure 1. From January 2004 to December 2009, there were 1480 male patients with emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis aged 40 years or above who underwent HRCT at our institute. Two radiologists (YSK and KJC) used the sequential reading process developed by Washko et al16 to review the HRCT images of these subjects. Of these patients, we excluded those with infection such as pneumonia or pulmonary tuberculosis owing to difficulty with visual assessment in infected patients. Exclusion of patients with infection was decided after careful consideration of clinical features, laboratory findings and follow-up images. Patients with connective tissue disease were excluded from this study, as well as patients with a diagnosis of other ILDs, such as drug-induced ILD, pneumoconiosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis, pulmonary histiocytosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis or eosinophilic pneumonia. In an official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement, regarding the classification of the IIP, CPFE was not believed to represent distinctive IIP but accepted as an example of co-existing patterns of emphysema and fibrosis in the same patient.17 Therefore, cases were acceptable for inclusion as CPFE if the following CT criteria were met: (1) presence of emphysema on CT scan, defined as well-demarcated areas of decreased attenuation compared with contiguous normal lung and marginated by a thin (<1 mm) or no wall, and/or multiple bullae (>1 cm) with upper zone predominance; (2) presence of diffuse parenchymal lung disease with significant pulmonary fibrosis on CT scan, defined as reticular opacities with peripheral and basal predominance, honeycombing, architectural distortion and/or traction bronchiectasis, focal ground-glass opacities and/or areas of alveolar condensation. In total, there were 113 patients [7.6% of 1480 patients, 95% confidence interval (CI), 6.4–9.1%] identified as having CPFE by a final reviewer (GYJ with 13 years' experience in chest radiology).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selection of the study population. CPFE, combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema; HRCT, high-resolution CT.

Clinical data

Clinical assessment of demographic data, smoking history in pack-years, pulmonary symptoms and signs, such as cough, sputum, dyspnoea, chest discomfort and basal crackles, and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) including forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), FEV1/FVC, vital capacity and diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) were evaluated using a review of medical records performed by one of the authors (YSK), who was blinded to the CT assessment results. All clinical data including PFTs were obtained within 1 month from the CT examination. The date of CPFE diagnosis was defined as the date of the CT examination. For survival analysis, survival time and cause of death were obtained from the medical records of our institution or the National Statistical Office of Korea.

CT Acquisition and image evaluation

Patients with CPFE underwent HRCT scan with one of two CT scanners (Somatom® Sensation 16 or Somatom® Definition AS; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The typical CT parameters were as follows: 120 kVp, 100 mAs, 1-mm slice thickness, 10-mm reconstruction interval with a high-spatial-frequency algorithm. Of the 113 patients with CPFE, 39 also had 1-mm reconstruction interval with no gap reconstruction and interval standard algorithm in addition. The HRCT images were evaluated using a standard window width of 1500 Hounsfield units (HU) and a window level of −700 HU. All CT data images were interfaced directly to our picture archiving and communication system (m-viewTM; Marotech, Seoul, Korea).

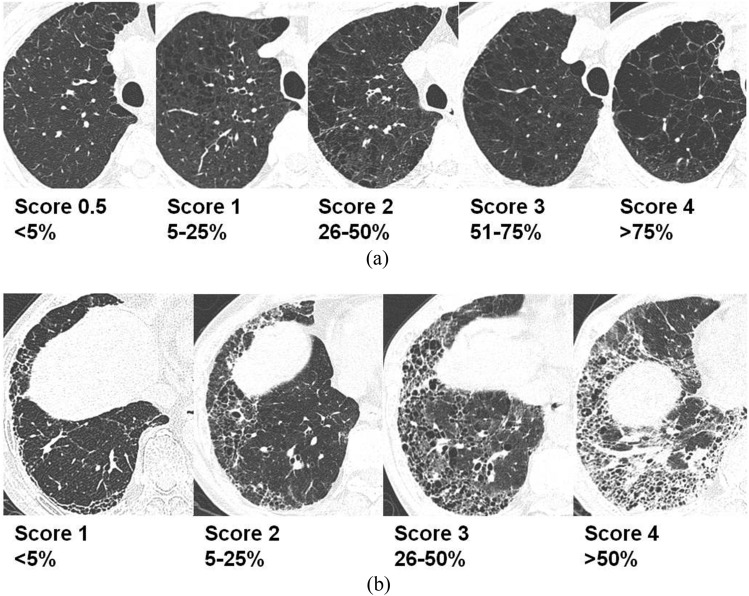

Two board-certified radiologists (SBJ and YSL, with 10 and 6 years' experience in HRCT interpretation, respectively) reviewed the HRCT of patients with CPFE and were blinded to any clinical information. The HRCT findings were interpreted on the basis of recommendations from the nomenclature committee of the Fleischner Society.18 Visual assessment of emphysema and fibrosis was performed based on the whole lobe rather than slices. Visual assessment methods for CPFE were made by modifying prior methods proposed by other researchers.19,20 The extent of emphysema was visually assessed using a 6-point scale for each lung lobe as follows: 0 = no emphysema, 0.5 = <5% (trivial), 1 = 5–25% (mild), 2 = 26–50% (moderate), 3 = 51–75% (marked) and 4 = >75% (very severe) involvement. Any disagreement surrounding the extent of emphysema based on discrepancies in more than one category were resolved by a third reader (GYJ). Overall extent of emphysema was calculated by averaging the 6-point scale scores of six lobes. The extent of each fibrotic component was also assessed in a whole lung using a 5-point scale for ground-glass attenuation (GGA), reticular abnormalities with GGA and honeycombing as follows: 0 = no abnormality, 1 = <5% (trivial), 2 = 5–25% (mild), 3 = 26–50% (moderate) and 4 = >50% (marked) involvement. Overall extent of fibrosis was separately assessed using a 5-point scale rather than averaging the score of each fibrotic component. Any disagreement surrounding the extent of fibrotic component and overall fibrosis based on discrepancies in more than one category was also resolved by a third reader (JGY). Reference images for each score range were prepared by the third reader and were provided to the two readers in order to enhance interobserver agreement (Figure 2). One of the authors (KJC) also calculated the emphysema index (EI) of patients with CPFE (n = 39) using commercialized software (syngo®, CT Pulmo 3D software; Siemens Healthcare).

Figure 2.

Reference high-resolution CT images for visual assessment of emphysema and overall fibrosis. (a) The extent of emphysema was visually assessed using a 6-point scale in each lung lobe. (b) The extent of overall fibrosis was also assessed using a 5-point scale for whole lung.

Statistical analyses

Interobserver agreement on the visually assessed extent of abnormalities (emphysema, GGA, reticular abnormalities with GGA and honeycombing) was analysed using a quadratic-weighted kappa statistic. Interobserver agreement was classified as follows: poor, κw = 0–0.20; fair, κw = 0.21–0.40; moderate, κw = 0.41–0.60; good, κw = 0.61–0.80; and excellent, κw = 0.81–1.00. EI and visually assed extent of emphysema were compared using a Spearman rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed to identify associations between mortality and HRCT extent of abnormalities, pulmonary function indices and clinical variables (age, pack-years smoking and presence of lung cancer). Variables with a p-value <0.20 in univariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model. A survival curve for the extent of honeycombing was generated using Kaplan–Meier methods and was compared using the log-rank test. At the time of survival analysis, patients were censored whether they were still alive, died from unknown cause or died from a known cause other than CPFE. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® software v. 18.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and MedCalc v. 12 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Results with a p-value <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and pulmonary function profiles

As detailed in Figure 1, 113 patients (mean age ± standard deviation, 67.2 ± 8.1 years; age range, 48–92 years) were analysed. The median follow-up time was 40.2 months (range, 1–102 months). Of the 113 patients with CPFE, 69 patients (61.1%) have more than 10% of emphysema. During the study period, 63 of 113 (55.8%) patients died, and the causes of death were respiratory cause including pneumonia (n = 24), lung cancer (n = 25), cardiovascular cause (n = 2), cerebrovascular (n = 2), other malignancy (n = 6), trauma (n = 1) and unknown (n = 3). Among 113 patients, the pattern of pulmonary fibrosis on CT were typical usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (n = 75), possible UIP (n = 27), non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (n = 4) and probable NSIP (n = 7). Histopathological confirmation of the fibrotic lung disease was available in 24 patients (13 patients with possible UIP, 4 patients with NSIP and 7 patients with probable NSIP) who were diagnosed as UIP.

A summary of patient demographics, smoking histories and PFTs are given in Table 1. The major clinical symptoms in the CPFE group were cough in 61.1% of the patients (69 of 113) and exertional dyspnoea in 53.1% of the patients (60 of 113). There were 28 patients (24.8% of 113 patients) with lung cancer (small-cell lung cancer = 8, non-small-cell lung cancer = 16 and histological subtypes of lung cancer not recorded exactly = 4). Of the eight small-cell lung cancer, two were limited stage and six were extensive stage. Of the 16 non-small-cell lung cancer, 1 was Stage I, 5 were Stage IIIA, 5 were Stage IIIB, 5 were Stage IV and there were no Stage II cancers (Clinical staging was measured according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging 7th edition). There were 8 cases of lung cancer that occurred during the follow-up period, 3 cases of lung cancer that occurred before the diagnosis of CPFE and the remaining 17 cases of lung cancer were found in combination with CPFE. The median follow-up duration between the diagnosis of CPFE and lung cancer was 21.5 months (range, 7.3–73.9 months).

Table 1.

Clinical data and pulmonary function indices of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema at the time of CT examination

| Variables | Valuea |

|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 67.2 ± 8.1 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 22.8 ± 4.1 |

| Smoking statusb | |

| Current | 72 (63.7) |

| Former | 41 (36.3) |

| Smoking (pack-years) | 38.1 ± 17.5 |

| Clinical manifestationb | |

| Cough | 69 (61.1) |

| Sputum | 55 (48.7) |

| Dyspnoea | 60 (53.1) |

| Chest discomfort | 10 (8.8) |

| Basal crackles | 36 (31.9) |

| Lung cancerb | 28 (24.8) |

| Physiological parameters | |

| FVC (percentage predicted) | 87.8 ± 16.7 |

| FEV1 (percentage predicted) | 91.0 ± 20.2 |

| FEV1/FVC (percentage) | 72.2 ± 10.2 |

| VC (percentage predicted) | 88.1 ± 17.0 |

| DLCO (percentage predicted)b | 69.7 ± 20.5 |

DLCO, diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; VC, vital capacity.

Unless otherwise noted, data are expressed in mean ± standard deviation.

Data are number of patients and values in parentheses are percentages.

Pulmonary function variables, with the exception of DLCO, were preserved. The FEV1 was <80% of percent predicted in 33.6 % (38 of 113 patients). The mean FEV1/FVC was 72.2%, and only 38.1% (43/113 patients) presented with an obstructive ventilatory defect, as defined by FEV1/FVC <70%. Impaired DLCO was the only abnormal pulmonary function value in 23.9% (27 of 113 patients).

Interobserver agreement of CT visual assessment

For visual assessments, interobserver agreement regarding the extent of emphysema in each lobe was graded from moderate to excellent (mean κw = 0.51–0.83), and the extent of fibrosis showed fair-to-good agreement (mean κw = 0.38–0.62). In the lobe-based visual assessment of emphysema, the upper lobes showed greater agreement (mean κw = 0.83) than the lower lobes (mean κw = 0.51). Honeycombing showed good agreement (mean κw = 0.61), whereas fair-to-moderate agreement was achieved for GGA and reticular abnormalities with GGA (mean κw = 0.38–0.43) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Visual assessment of CT findings

| Characteristics | CT visual assessment score | Interobserver agreement (κw) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | ||

| Extent of CT findings | |||

| Emphysemaa | |||

| Upper lobe | 1.60 ± 1.25 | 0.83 | 0.77–0.91 |

| Middle lobeb | 0.92 ± 1.10 | 0.74 | 0.65–0.84 |

| Lower lobe | 0.85 ± 1.02 | 0.51 | 0.38–0.69 |

| Overall | 1.38 ± 1.08 | 0.80 | 0.72–0.89 |

| Fibrosisa | |||

| GGA | 0.65 ± 0.97 | 0.43 | 0.24–0.61 |

| Reticulation with GGA | 0.49 ± 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.22–0.61 |

| Honeycombing | 1.87 ± 0.95 | 0.61 | 0.45–0.77 |

| Overall | 2.10 ± 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.48–0.77 |

CI, confidence interval; GGA, ground-glass attenuation.

Data are expressed in mean ± standard deviation.

The lingula of the left lung was evaluated as middle lobe.

Comparison of emphysema index and visually assessed emphysema extent

Mean EI, available in 39 patients, was 9.10 ± 9.26, and the visual assessment score was 1.45 ± 1.26. The Spearman correlation coefficient for the relationships between EI and visually assessed extent of emphysema were 0.685 (right upper lobe, p = 0.000), 0.394 (right middle lobe, p = 0.013), 0.138 (right lower lobe, p = 0.403), 0.563 (left upper lobe, p = 0.000), 0.450 (left lingular segment, p = 0.004) and 0.353 (left lower lobe, p = 0.028). In the whole lung, the correlation coefficient was 0.528 (p = 0.001). This result shows that the extent of emphysema on visual assessment correlated relatively well with EI.

Risk factor for survival

In this study, age, pack-years smoking, FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, VC, DLCO, visually assessed emphysema extent, visually assessed honeycombing extent and lung cancer were considered to be candidate prognostic factors. Through univariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, pack-years smoking, FVC, FEV1, DLCO, honeycombing extent and lung cancer were identified as risk factors for survival in patients with CPFE (Table 3). Multivariate analysis revealed that the three variables of DLCO [hazard ratio (HR), 0.967; 95% CI, 0.94–0.99; p = 0.017], honeycombing extent (HR, 1.950; 95% CI, 1.12–3.39; p = 0.018) and lung cancer (HR, 5.567; 95% CI, 2.29–13.51; p < 0.001) were significant independent risk factors for survival (Table 4). However, pack-years smoking, FVC and FEV1 were not significant risk factors for survival (p = 0.411 and p = 0.767, respectively).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for survival rate of patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in a univariate Cox model

| Prognostic factor | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.007 | 0.97–1.05 | 0.696 |

| Pack-years smoking | 1.013 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.143 |

| FVC | 0.972 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.005 |

| FEV1 | 0.984 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.039 |

| FEV1/FVC | 1.010 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.561 |

| VC | 0.987 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.318 |

| DLCO | 0.968 | 0.94–0.99 | 0.001 |

| Emphysema extent | 1.105 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.434 |

| Honeycombing extent | 1.762 | 1.32–2.35 | <0.001 |

| Lung cancer | 8.480 | 4.55–15.82 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; DLCO, diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; VC, vital capacity.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (HRs) for survival rate of patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in a multivariate Cox model

| Prognostic factor | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pack-years smoking | 1.014 | 0.985–1.044 | 0.338 |

| FVC | 1.011 | 0.984–1.039 | 0.411 |

| FEV1 | 0.994 | 0.957–1.033 | 0.767 |

| DLCO | 0.967 | 0.941–0.994 | 0.017 |

| Honeycombing extent | 1.950 | 1.123–3.385 | 0.018 |

| Lung cancer | 5.567 | 2.293–13.514 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; DLCO, diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

The 5-year survival rate of patients with CPFE with 5–25% honeycombing in both lower lobes on CT was 55.7% (Figure 3). The 5-year survival rate decreased to 33.3% in patients with >50% honeycombing (p = 0.0009). In patients with CPFE, the median survival time decreased according to honeycombing extent: 5.80 ± 1.16 (5–25%), 2.73 ± 0.71 (26–50%) and 2.01 ± 1.08 (>50%) years, respectively.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of survival rate with respect to extent of honeycombing in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. The 5-year survival rate was 78.5% in patients with honeycombing that was <5% in both lower lobes, 55.7% in patients with 5–25% honeycombing, 32% in patients with 26–50% honeycombing and 33.3% in patients with >50% honeycombing.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests the following: (a) visual stratification of honeycombing on CT is useful for predicting the prognosis in patients with CPFE; (b) the 5-year survival rate was 78.5% for <5% honeycombing and 33.3% for >50% honeycombing on CT; (c) >50% honeycombing extent on CT predicts worse outcome in patients with CPFE.

Recently, Choi et al12 reported that fibrosis-weighted CT index [doubled fibrosis score (visually estimated to the nearest 5% of parenchymal involvement) + EI] was an independent predictor of survival in a biopsy-proven CPFE cohort. Compared with the study by Choi et al,12 we used visual stratification using a 5-point or 6-point scale for CT abnormalities. Thus, our study highlights the importance of simplified scoring system when conveying prognostic information to patients in everyday practice. Thus, regardless of semiautomatic quantitative or automatic quantification of honeycombing, we think it is important to quantify the extent of honeycombing on serial CT in patients with CPFE. In our study, among various pulmonary function variables, only reduction in DLCO was significantly and independently associated with increased mortality in patients with CPFE. In addition, differing from our present results, Choi et al12 reported that FVC was the only predictor of survival among various pulmonary function variables. One possible reason for this difference might be the difference in study population. In CPFE, owing to the counterbalancing effects of emphysema (obstructive) and pulmonary fibrosis (restrictive) on FVC, the extent of disease (i.e. emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis) is not proportionately reflected in FVC. This corresponds with findings recently described by Ando et al21 who demonstrated that CPFE had a good correlation between DLCO and low attenuation area in the upper lobe (emphysema) or parenchymal density in the lower lobe (pulmonary fibrosis) but no significant correlation between FVC and low attenuation area or parenchymal density. Accordingly, our results suggest that direct measurement of each pathological component using CT and DLCO, which is not counterbalanced by each pathologic component, adequately reflects disease status and more precisely predicts disease prognosis.

In contrast to the extent of honeycombing, the extent of emphysema showed no statistical significance (HR, 1.105; p = 0.434; 95% CI, 0.86–1.42) in predicting prognosis of CPFE in this study. One possible explanation for this observation is that the physiological effect of pulmonary fibrosis had greater impact than that of emphysema. This hypothesis is supported by a previous comparative study between CPFE and IPF or emphysema alone.22 Patients with CPFE present with a worse prognosis than emphysema-only patients. However, survival rate of patients with CPFE is better or similar to that of patients with IPF.1,4,6,8–10 Therefore, it is difficult to prove the statistical significance of emphysema extent, even if emphysema has a deteriorative effect on survival with CPFE. An alternative possibility for this observation is that CPFE is not the simple coincidence of IPF and emphysema. If CPFE is a distinct disease entity, the prognostic effect of emphysema in CPFE will be different from that in emphysema alone.

In this study, increased mortality was associated with lung cancer, which was responsible for 39.7% of deaths. In patients with CPFE, lung cancer is common. The previously reported prevalence of lung cancer in patients with CPFE ranged from 5% to 47%.3 In our study, lung cancer had a prevalence of 24.8% in patients with CPFE. The prevalence of lung cancer in the CPFE cohort might be affected by the definition of CPFE used in the study. Although a consensus definition of CPFE syndrome does not currently exist,2 we used 5% of emphysema and 5% of honeycombing on CT as the minimal requirement for defining CPFE cases in this study. Therefore, the inclusion of relatively early disease states of CPFE contributes to reducing the prevalence of lung cancer. The prevalence of lung cancer in patients with CPFE is also influenced by the duration of the follow-up period. In this study, the median follow-up duration for all cases of CPFE was 40.2 months. The duration between the diagnosis of CPFE and lung cancer for eight cases of lung cancer diagnosed during the follow-up period ranged from 7.3 to 73.9 months. If the pathogenesis of lung cancer in CPFE is chronic inflammation and repeated lung injury, as in IPF or emphysema,23,24 early CPFE may have a longer duration between the diagnosis of CPFE and lung cancer. In this respect, a longer follow-up can alter the analysed prevalence of lung cancer in CPFE. However, to our knowledge, there has not been a published report on risk factors or incidence of lung cancer in CPFE. Therefore, future work investigating the relationship between lung cancer and CPFE is needed.

There were several limitations in this study. First, our study was limited by its retrospective study design. Second, in this study, surgical resection for fibrotic lung disease was performed in only 21.2% (24 of 113) of patients. Prognosis and survival time of fibrotic lung disease such as IPF or NSIP are affected by histopathology. Therefore, further study on the histopathology of CPFE may be required. Third, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate emphysema with overlapping GGA from honeycombing on dependent portions of CT. Thus, emphysema with overlapping GGA could be misinterpreted as honeycombing.25 Also, the CT protocol in this study did not include prone scanning, which might be very useful for the evaluation of GGA and emphysema in dorsal lungs. To overcome this problem, we attempted to exclude all infected patients in this study. In spite of this effort, we acknowledge the difficulties in differentiating emphysema with overlapping GGA from ILDs in the lower lobe on CT. Fourth, Cox proportional hazard analysis was conducted using the visually assessed extent of emphysema rather than computer-aided quantification. Because this study was retrospective, most CT images were not appropriate for quantitative analysis with commercial analysis tools. However, Kim et al13 showed that visual assessment of emphysema in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may also provide reproducible, physiologically substantial information that rivals information provided by quantitative CT assessments. Additionally, our limited analysis of 39 patients shows a relatively good correlation between EI and visually assessed extent of emphysema. Fifth, we did not evaluate clinical staging of lung cancer as a risk factor of survival because the number of patients for each clinical stage was too small to perform Cox hazard regression analysis. Also, advanced stage of lung cancer was more included in our study. Therefore, our result regarding lung cancer as a risk factor of survival could be of exaggerated statistical significance.

We found that >50% honeycombing on CT predicts worse outcome in patients with CPFE. In addition to honeycombing on CT, presence of lung cancer and reduction of DLCO may identify patients with a poor outcome. Therefore, careful quantification of honeycombing extent on initial CT and regular CT follow-up for early detection of lung cancer with PFT including DLCO provides useful prognostic information to guide management of patient with CPFE.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

“This paper was supported by Fund of Biomedical Research Institute, Chonbuk National University Hospital”

Contributor Information

Yong Seek Kim, Email: yongseek.kim@gmail.com.

Gong Yong Jin, Email: gyjin@chonbuk.ac.kr.

Kum Ju Chae, Email: para2727@gmail.com.

Young Min Han, Email: ymhan@jbnu.ac.kr.

Su Bin Chon, Email: chonsb66@hanmail.net.

Young Sun Lee, Email: drlys0828@naver.com.

Keun Sang Kwon, Email: drkeunsang@jbnu.ac.kr.

Hye Mi Choi, Email: hchoi@jbnu.ac.kr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cottin V, Nunes H, Brillet PY, Delaval P, Devouassoux G, Tillie-Leblond I, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a distinct underrecognised entity. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 586–93. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00021005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankowich MD, Rounds SI. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a review. Chest 2012; 141: 222–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papiris SA, Triantafillidou C, Manali ED, Kolilekas L, Baou K, Kagouridis K, et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Expert Rev Respir Med 2013; 7: 19–31; quiz 32. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mejia M, Carrillo G, Rojas-Serrano J, Estrada A, Suarez T, Alonso D, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: decreased survival associated with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2009; 136: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottin V, Le Pavec J, Prevot G, Mal H, Humbert M, Simonneau G, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome. Eur Respir J 2010; 35: 105–11. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00038709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishaba T, Shimaoka Y, Fukuyama H, Yoshida K, Tanaka M, Yamashiro S, et al. A cohort study of mortality predictors and characteristics of patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. BMJ Open 2012; 2. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt SL, Nambiar AM, Tayob N, Sundaram B, Han MK, Gross BH, et al. Pulmonary function measures predict mortality differently in IPF versus combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 176–83. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurashima K, Takayanagi N, Tsuchiya N, Kanauchi T, Ueda M, Hoshi T, et al. The effect of emphysema on lung function and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2010; 15: 843–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akagi T, Matsumoto T, Harada T, Tanaka M, Kuraki T, Fujita M, et al. Coexistent emphysema delays the decrease of vital capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2009; 103: 1209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jankowich MD, Rounds S. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema alters physiology but has similar mortality to pulmonary fibrosis without emphysema. Lung 2010; 188: 365–73. doi: 10.1007/s00408-010-9251-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryerson CJ, Hartman T, Elicker BM, Ley B, Lee JS, Abbritti M, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2013; 144: 234–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi SH, Lee HY, Lee KS, Chung MP, Kwon OJ, Han J, et al. The value of CT for disease detection and prognosis determination in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE). PLoS One 2014; 9: e107476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SS, Seo JB, Lee HY, Nevrekar DV, Forssen AV, Crapo JD, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: lobe-based visual assessment of volumetric CT by using standard images—comparison with quantitative CT and pulmonary function test in the COPDGene study. Radiology 2013; 266: 626–35. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin KM, Lee KS, Chung MP, Han J, Bae YA, Kim TS, et al. Prognostic determinants among clinical, thin-section CT, and histopathologic findings for fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: tertiary hospital study. Radiology 2008; 249: 328–37. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483071378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edey AJ, Devaraj AA, Barker RP, Nicholson AG, Wells AU, Hansell DM. Fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: HRCT findings that predict mortality. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 1586–93. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2098-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Washko GR, Lynch DA, Matsuoka S, Ross JC, Umeoka S, Diaz A, et al. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad Radiol 2010; 17: 48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 733–48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Muller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008; 246: 697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva CI, Muller NL, Hansell DM, Lee KS, Nicholson AG, Wells AU. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: changes in pattern and distribution of disease over time. Radiology 2008; 247: 251–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2471070369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gietema HA, Muller NL, Fauerbach PV, Sharma S, Edwards LD, Camp PG, et al. Quantifying the extent of emphysema: factors associated with radiologists' estimations and quantitative indices of emphysema severity using the ECLIPSE cohort. Acad Radiol 2011; 18: 661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ando K, Sekiya M, Tobino K, Takahashi K. Relationship between quantitative CT metrics and pulmonary function in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Lung 2013; 191: 585–91. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9513-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CH, Kim HJ, Park CM, Lim KY, Lee JY, Kim DJ, et al. The impact of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema on mortality. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15: 1111–16. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwano K, Kunitake R, Kawasaki M, Nomoto Y, Hagimoto N, Nakanishi Y, et al. P21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 and p53 expression in association with DNA strand breaks in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 154(2 Pt 1): 477–83. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao H, Rahman I. Current concepts on the role of inflammation in COPD and lung cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2009; 9: 375–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akira M, Inoue Y, Kitaichi M, Yamamoto S, Arai T, Toyokawa K. Usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia with and without concurrent emphysema: thin-section CT findings. Radiology 2009; 251: 271–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511080917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]