Summary

Coliphage T5 injects its DNA in 2 steps: the first step transfer (FST) region 7.9% is injected and its genes are expressed and only then does the remainder (second step transfer, SST) of its DNA enter the cell. In the FST region, only 2 essential genes (A1 and A2) have been identified and a third (dmp) non-essential gene codes for a deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase. Thirteen additional putative ORFs are present in the FST region. Numerous properties have been attributed to FST region, including SST, host DNA degradation, inhibition of host RNA and protein synthesis, restriction insensitivity and protection of T5 DNA. These effects do not occur following infection with an A1 mutant. The A2 gene seems only to be involved in SST transfer. This is puzzling since there are more seemingly unrelated effects than there are essential genes to accomplish them and it is possible that some important genes were not identified. This review attempts to analyze these problems that were first identified in the 1970–80 s. In particular, an attempt is made to determine which potential ORFs are conserved in evolution (and thus likely to be important); by comparing T5 to 10 newly isolated and completely sequenced T5-like phages. A similar approach is used to identify conserved repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes that occur in all T5-like phages in the region containing the injection stop signal (iss) and the terminase substrate. Finally, an attempt is made to re-analyze the mechanism whereby T5 protects itself from the enzymes that degrade host DNA, from the RecBCD nuclease and from restriction enzymes. For all of these FST effects new hypotheses and possible new genetic and biochemical approaches are envisaged.

Keywords: bacteriophage T5, DNA degradation, DNA protection, DNA packaging, phage injection, phage genomes, phage evolution, restriction enzymes

Abbreviations

- bp

base pairs

- FST DNA

first step transfer DNA

- iss

injection stop signal

- kb

kilobase pairs

- LTR

left terminal repeat

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- ORF

open reading frame

- ris

mutationally induced EcoRI site

- RTR

right terminal repeat

- SST DNA

second step transfer DNA

Introduction

T5 is a member of the Siphoviridae and is one of the 7 classical Caudovirales or tailed bacteriophages that were originally designated T (for “Type”) phages by Delbrück and co-workers. It was among the first bacteriophages to be studied; a PubMed search reveals that the first phage T5 publication was in 1949; as compared to 1948 for phage T4 and 1953 for λ. T5 has linear genome of 121,750 bp and has large terminal repeats (LTR and RTR) each comprising 10,219 bp (Fig. 1). Unlike phage T4 DNA, which is glycosylated and methylated, T5 has normal DNA with a GC content of 39.3%. T5 DNA injection in vivo takes place in 2 steps; First Step Transfer (FST), corresponding to about 8% of the genome and is accomplished very rapidly and Second Step Transfer (SST, corresponding to the remaining 92% of the genome) which occurs within 3–5 minutes.1 The SST region is organized into early functions, replicative functions and late function such as capsid components (for review see Sayers, 20062). The SST region also contains a 12 kb region, containing T5 specified 24 tRNA genes, which can be deleted without obvious deleterious effects on phage growth. T5 DNA is unusual in having 5 nicks, all on the 3′ to 5′ strand. Another peculiarity of T5 is that it is insensitive in vivo to several E. coli Type I, Type II and Type III restriction systems.3,4 In the early 1960 s and 70 s, genetic experiments allowed the construction of a genetic linkage map showing the grouping of genes according to pre-early, early and late genes.5 In parallel, biochemical studies characterized many phage functions and enzymes. Toward the mid-1980s research funds for bacteriophages became scarce and T5 research dwindled correspondingly. The nucleotide sequence of phage T5 was determined in 2004;6 at a time when many T5 researchers had left the field. More recently, some new T5-like phages were isolated with the viewpoint of phage therapy and the nucleotide sequences of these were determined. Nothing is known of the genetics and biochemistry of these new phages.

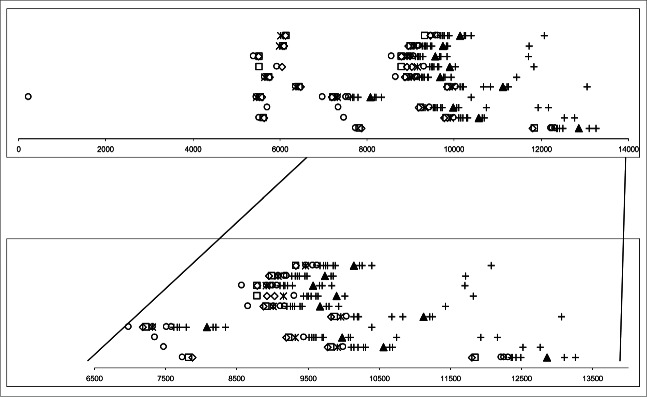

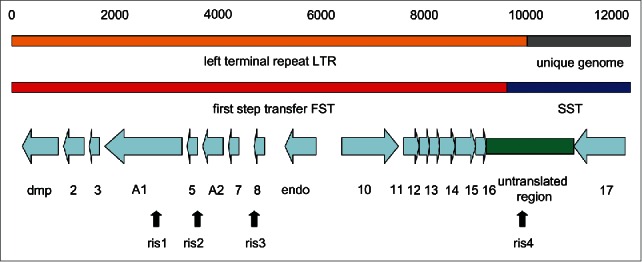

Figure 1.

Genetic map of the LTR of T5. Only the left 12,000 bp of the 121,750 bp phage T5 genome are shown, together with the position of the LTR (line 1) and the FST and SST regions of the genome (line 2). The positions of the ORFs and the non-coding region correspond to the Paris-Orsay nucleotide sequence (accession number AY692264.1) according to the NCBI ORF predictions (line 3). The approximate positions of the ris mutationally induced EcoRI sites (line 4) are according to Heusterspreute et al.11

The present review deals only with the FST functions which are found in the LTR (Fig. 1). The FST region is fascinating since many different and complex phenomena seem to be governed by only a few poorly understood genes. This article reviews our knowledge of the FST genes and of the curious non-coding region at the right end of the left terminal repeat. The availability of the nucleotide sequences of new T5-like phage genomes opens up a different way of genetic analysis of this region. Consequently this review will be divided into 2 parts; the first dealing with phage T5 and the second comparing the genomic structures of the new T5-like phages. The conclusion will attempt to suggest new perspectives and methods of analysis for future T5 research.

The genetics and biochemistry of the FST region

Phage injection

Phage injection takes place from the left hand end of the molecule7 and is initiated by the simple interaction of the bacteriophage with the host outer-membrane receptor protein FhuA.8 FhuA serves as a ferrichrome transporter and also serves as the receptor for the lambdoid phage ϕ80, phage T1 and colicin M. The tip of the phage tail, carrying T5 protein pb5, docks at FhuA and acts as an injection needle to enable the transfer of the entire T5 genome across the cell membrane. The complete injection can be demonstrated in vitro using proteoliposomes containing FhuA protein where the entire phage genome is injected almost instantaneously into the liposome.

Phage injection is a ‘pre’-pre-early event controlled by late gene products and their interaction with the receptor FhuA and is thus outside the scope of this article. It has been recently reviewed.9 However, the finding that the entire T5 DNA molecule is transferred simultaneously into the liposome in vitro is very important for the present discussion since it contrasts with the in vivo situation where the genome is transferred in a 2-step process. This implies an interaction between the host and the phage DNA that has not been explained by the in vitro studies. Possible T5 DNA features that may be involved in such an interaction are discussed below.

The discovery of 2-step DNA transfer

In their classical experiment Hershey and Chase (1952)10 showed that the phage T1 protein head and tails could be stripped from the infected cell by blending without destroying infectivity; thereby demonstrating that DNA, and not protein, was the genetic material. When Lanni (1969)2 attempted to repeat the same experiment using T5 she obtained the same result using long phage absorption times. However, with short absorption times, or in the presence of chloramphenicol, the result was quite different. After three minutes of infection, followed by blending, only 8% of the phage DNA was associated with the cell. The remaining 92% then followed, but only in the presence of protein synthesis; leading to the conclusion that T5 injection takes place in 2 steps. This remarkable experiment demonstrated 2-step injection of T5 DNA and this distinguishes T5 from most other phages.

The genetic map T5 FST region

Nomenclature is important in understanding the genetic and physical maps of T5 (Fig. 1). The left terminal repeat (LTR) of 10.219 kb is identical in nucleotide sequence to the right terminal repeat (RTR). In contrast, the FST region is defined by the point of shear of the phage/bacterium complex in a blender. Consequently, the exact size of the FST region cannot be given, though gel electrophoresis estimations give it as about 7.9% (roughly 9740 bp).2,11 The third concept is that of the T5 Injection Stop Signal (iss) which is the hypothetical signal that stops FST transfer by a DNA/bacterium interaction. The isolation of a deletion mutant of phage BF23 (BF23st4), in which about half of the FST region is deleted (though A1 and A2 are retained) and in which the FST region is correspondingly smaller, argues for the existence of a specific site on the LTR where injection stops.12 Genetic and nucleotide sequencing arguments11 place the injection stop signal iss to the left of nucleotide 9966, since this position is already in SST DNA (discussed in detail below). It is easiest to imagine that shear takes place at the cell surface at a point in time when the iss is already inside the bacterium. This places the shear site to the right of the iss and to the left of nucleotide 9966.

In the early 1960s Lanni and McCorqudale isolated temperature-sensitive mutants and host conditional amber mutants of phage T5 and constructed a genetic linkage map showing the grouping of genes according to pre-early, early and late genes.5 Out of 16 amber mutants in the FST region, only two genes were identified; the A1 and the A2 genes.2 In old reports, reference is made to the A3 gene or to the A2–A3 gene (the idea of an A3 gene refers to the phenotype of abortive infection in a host carrying the ColIb plasmid) but it is now accepted that A3 is part of A2 (see below). One other FST gene was identified by mutation; the deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase (dmp) which participates in the final stages of host DNA degradation.13 However this gene is not essential for T5 growth and could not have been isolated as a conditional lethal mutant. No genes, other than dmp, A1 and A2 have been identified in the ∼9.6 kb FST or the 10.139 kb LTR regions, which are large enough to carry several more genes. Nucleotide sequence (described below) shows a total of 16 putative ORFs (including dmp, A1 and A2) and thus it is not excluded that other essential genes could have been missed in early mutant searches, particularly since some FST ORFs are quite small.

Four other genetically identified sites (not genes) conferring sensitivity to EcoRI (ris mutants), also map in the LTR.3 These are discussed in detail below in the section on restriction insensitivity.

The biochemical functions of the FST region

Within the first few minutes of infection the host DNA is degraded to nucleotides and then to free bases which are excreted from the cell.14 Host DNA degradation also occurs in A2 mutants, but not in A1 mutants. This may be a secondary effect since, while A1 mutants have multiple phenotypes (discussed below), no nuclease activity has been reported to be associated with the A1 protein or any other FST gene. In addition to host DNA degradation, many host functions such as DNA, RNA and protein synthesis are rapidly shut-off following T5 infection. The FST region also provides protection against restriction enzymes and the recBCD nuclease.

Nucleotide sequencing of the T5 genome

In 2004–6, the T5 nucleotide sequence was determined almost simultaneously by three geographically different groups in Hangzhou, China,6 Paris-Orsay,15 and Moscow16 and were respectively given the accession numbers AY587007.1, AY692264.1 and AY543070.1. For simplicity in nomenclature these will be referred to as sequences being from Hangzhou, Paris-Orsay and Moscow. Only the Hangzhou sequence was published as a full length annotated publication, though the other sequences are well annotated in the NCBI databases. It should be noted that the 3 strains of T5 sequenced were not identical and that this leads to sequence differences that can have a considerable effect on the interpretation. The Paris-Orsay sequence was obtained using a deletion mutant st0 that lacks the tRNA genes. However this does not affect the FST region of interest to this article and the Orsay sequence and that from Moscow (for T5+) are nearly identical in the LTR region. In contrast, the Hangzhou sequence carries a 75 bp deletion compared to the Paris-Orsay and Moscow sequences; starting at coordinate 5599. This difference was noticed by the authors who verified its authenticity. It is thus likely that this deletion is not a simple sequencing error but rather represents a real difference in the genetic material studied. Indeed parts of the coding region for the 172 amino acid HNH endonuclease (present in the Paris-Orsay and Moscow sequences) can be detected in the Hangzhou sequence. For the present purposes, we have (arbitrarily) chosen to use the Paris-Orsay sequence which is almost identical to that from Moscow. The predicted ORFs of the Hangzhou, Paris-Orsay, and Moscow sequences are compared in Table 1 where it can be seen that the predicted ORFs for Paris-Orsay and Moscow are very similar, but differ from the Hangzhou predictions in the region of the 75 bp deletion.

Table 1.

ORFs and putative proteins present in the LTR of the 3 T5 nucleotide sequences from Hangzhou, Paris-Orsay and Moscow

| Hangzhou AY587007.1 |

Paris-Orsay AY692264.1 |

Moscow AY543070.1 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus tag | aa | Locus tag | aa | Locus tag | aa |

| ORF001 = dmp | 244 | T5p001 = dmp | 244 | T5.001 = dmp | 244 |

| ORF002 | 131 | T5p002 | 131 | T5.002 | 131 |

| ORF003 | 92 | T5p003 | 92 | T5.003 | 92 |

| ORF004 = A1 | 527 | T5p004 = A1 | 556 | T5.004 | 556 |

| ORF005 | 48 | — | — | — | — |

| ORF006 preA1 | 65 | T5p005 | 65 | T5.005 | 65 |

| ORF007 = A2 | 135 | T5p006 = A2 | 135 | T5.006 = A2 | 135 |

| ORF008 9.2kDa | 83 | T5p007 | 83 | T5.007 | 83 |

| — | — | T5p008 | 67 | T5.008 | 67 |

| — | — | — | — | T5.009 | 35 |

| — | — | T5p009 = endo | 172 | T5.010 = endo | 172 |

| ORF009 | 53 | — | — | — | — |

| ORF010 | 63 | — | — | — | — |

| ORF011 | 245 | T5p010 | 336 | T5.011 | 336 |

| ORF012 | 77 | — | — | — | — |

| ORF013 | 76 | T5p011 | 87 | T5.012 | 76 |

| ORF014 | 59 | T5p012 | 59 | T5.013 | 59 |

| ORF015 | 70 | T5p013 | 70 | T5.014 | 70 |

| ORF016 | 114 | T5p014 | 114 | T5.015 | 114 |

| ORF017 | 31 | — | — | — | — |

| — | T5p015 | 92 | T5.016 | 85 | |

| — | T5p016 | 67 | T5.017 | 67 | |

| End LTR | End LTR | End LTR | |||

| ORF018 | 294 | T5p017 33.8 kDa | 294 | T5.018 | 294 |

The ORF predictions are those of the NCBI database for the accession numbers indicated.

The FST ORFs

The FST region contains 16 ORFs. ORFs01 to 09 (including dmp, A1 and A2) are transcribed from right to left.6,17,18 In contrast, ORFs10 to 16 are transcribed from left to right (Fig. 1). A large 1778 bp non-coding region separates the rightmost FST gene (ORF16) from the first SST gene (ORF17). This non-coding region thus spans the FST/SST junction and carries the iss region (discussed in detail below).

The deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase (dmp) gene

The deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase was identified and characterized as a 244 aa polypeptide active only on 5′-dNMP's.13,14 It is known to participate in the final stages of host DNA degradation but is not essential for T5 growth. Several dmp mutants were isolated that completely lacked deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase activity. In dmp mutants about 30% of the host DNAs' thymine residues are incorporated into T5 DNA during phage replication; in contrast to almost 0% in wild type T5.13 It is not obvious why T5 needs to completely destroy host 5′ deoxynucleotides and export the free bases into the medium. Most other phages re-incorporate substantial amounts of host nucleotides. Phage T7 breaks down host DNA and incorporates 90% into its own genome. Similarly phage T4 re-incorporates about 20% of host nucleotides into its genome.14 In other phages host degradation and phage DNA synthesis proceed simultaneously; unlike in T5 where they are temporally separate processes. For unknown reasons the dmp mutants showed slower growth with delayed production of early enzymes and DNA synthesis, though host DNA degradation, shut-off of DNA synthesis and SST proceed normally. The deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase activity disappears immediately after SST, so that new deoxynucleotides may be synthesized and incorporated into T5 DNA. The mechanism of its shut-off is unknown but is possibly due to a SST function. The deoxyribonucleotide 5′ monophosphatase has little homology to other sequences in the NCBI databases, except for T5-like phages (discussed below).

The A1 gene

The A1 gene product (556 aa) is essential for SST DNA injection and A1 mutants exhibit a bewildering variety of pleiotropic phenotypes of which the most obvious is that, in the absence of A1 gene product, nothing happens after FST transfer. In particular A1 mutants do not inject SST DNA, or cause degradation of host DNA, or shut-off of host RNA and protein synthesis. Another phenotype of some mutants of the A1 gene is that they are sensitive to exclusion by the rex genes of λ lysogens.19

Transcription of pre-early genes is turned off after 3–4 minutes even when SST is prevented by a mutation in gene A2. In contrast, a mutation in gene A1 blocks this turn-off, suggesting that the A1 product is responsible for pre-early transcription turn-off. It was shown that the A1 product binds to purified host RNA polymerase in infected cells, together with another pre-early 11 kda polypeptide.20 The complexed RNA polymerase transcribed early genes better than pre-early genes and it was suggested that A1 product associated with host RNA polymerase to shut off pre-early genes. This 11 kDa protein has similarly been seen to be associated with RNA polymerase in immuno-precipitation assays.21 The identity of the 11 kDa polypeptide was not determined in either study, but (retrospectively) its size suggests that it could correspond to the 10.7 kDa ORF03 protein. The A1 protein has been identified as T5 coded 57 kDa membrane protein22 which roughly corresponds to the size predicted from the A1 ORF (61.5 kDa).

Unlike the Dmp protein and the A2 protein, the A1 protein has homology to many other proteins in the NCBI databases. In particular an A1 homolog is present in unrelated Caulobacter phage PhiCbK23 and several other non-T5 phages. Similar sequences are also present in some bacteria such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Neorhizobium galegae, Brucella abortus, Sulfitobacter pseudonitzschiae, Pseudomonas stutzeri, Myxococcus stipitatus. Indeed there is a small family of A1-related proteins, though the function is unknown in all cases.

The A2 gene

Like A1 mutants, A2 mutants do not inject SST DNA.2 The A2 gene product has been purified and shown to have DNA binding activity,24,25 with a molecular weight of 15,000; which agrees with nucleotide sequence predictions of 14,300 for the A2 ORF protein. The A2 protein also has been reported to interact with the A1 protein and the cell membrane.26

The A2 protein is responsible for abortive infection of T5 on E. coli carrying the colicinogenic plasmid ColIb.27 A host component is also involved in T5 abortive infection of colIb hosts28 so that the abortive infection requires phage, host and plasmid components. A phage λ recombinant carrying an active A2 gene, transcribed from the λ pL promoter, was isolated and was able to complement T5 A2 mutants in mixed infection.29,30 In agreement with sequencing predictions, this recombinant was shown to code for a 14.0 kDa protein corresponding to the A2 product (14.3 kDa). This λ recombinant is unable to grow on a E. coli host carrying the ColIb plasmid, showing that the A2 gene product is the only T5 gene responsible for the abortion of T5 infection by ColIb.

The RecBCD nuclease has double-strand exonuclease, single-strand exonuclease, single-strand endonuclease and helicase activities.31 Phage sensitivity to RecBCD nuclease can occur during DNA injection but also replication and maturation of the DNA.32 Most (perhaps all) linear DNA phages (e.g. mu, T2, T3, T4, T6, T7, λ, ϕ80) encode a protein to protect their DNA from RecBCD nuclease, and T5 is no exception33-35 though the T5 gene that inactivates RecBCD nuclease is unknown. If, as seems possible (discussed below), the T5 genome circularizes, via recombination, after SST injection, it may become protected from the exonuclease (as does λ). Alternatively it may transiently exist in a protected compartment.32 Benzinger and McCorquodale36 investigated the role of RecBCD in T5 transfection of spheroplasts; which differs from phage mediated infection in that all of the DNA enters the cell simultaneously, rather than in a 2-step process. They compared the efficiency of transfection by T5 mutants of non-permissive (su−) E. coli spheroplasts carrying (or not) a mutation in recB, which lacks the RecBCD nuclease. Remarkably it was found that the A2 mutant in the su− recB− host was able to form infective centers at a frequency of 16% of that of wild-type T5. No transfection was found in su− Rec+ spheroplasts due to the highly active RecBCD nuclease. As a control, a different amber mutant D9 (defective in T5 DNA polymerase) was unable to produce any infective centers under the same conditions. It was suggested that the A2 (or the A1/A2) gene product acts to protect the FST DNA from the RecBCD nuclease. The A2 protein may be only necessary for normal infection by phage particles and almost dispensable for the infection of recBCD mutant spheroplasts, whereby the normal injection process is bypassed and RecBCD nuclease is absent.36

The A2 protein has no homology to other sequences in the NCBI databases except for other T5-like phages (discussed below).

Restriction insensitivity in T5

Phage T5 has no EcoRI restriction sites on its FST DNA but carries 6 EcoRI cleavage sites on the rest of its SST genome. Despite the presence of these restriction sites phage T5 is able to grow on an EcoRI restricting host, suggesting that it specifies a restriction protection system.3 In addition, T5 grown on an EcoR1 modifying host does not become modified; its DNA remains sensitive to EcoRI endonuclease in vitro.4 The restriction protection hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that T5 is also not restricted in vivo by restriction enzymes EcoK (Type I) and EcoP1I (Type III) which have different mechanisms and structures from EcoRI. Another report (in Russian)37 shows that T5 is also not cleaved or modified in vivo by either EcoRV or EcoRII. As with EcoRI, there are no EcoRV sites in the T5 FST region and several on the remainder of the genome. On the other hand there are 4 EcoRII sites on the T5 FST region. However, EcoRII requires 2 nearby restriction sites for cleavage and, in the FST region, these are spaced too far apart to act as restriction cleavage sites. Thus T5 is insensitive to restriction by (at least) EcoRI, EcoRII, EcoRV, EcoK and EcoP1I.

Bacteriophage λ has proved invaluable for the analysis of the basic mechanisms of restriction and modification. However other bacteriophages have a more complicated interaction with the restriction/modification systems of the host.38 Thus, for example, bacteriophage T3 produces an S-adenosylmethionine cleaving enzyme which simultaneously prevents both restriction and modification by the EcoK and EcoB restriction/modification systems.39,40 The related phage T7 does not code for such an enzyme but both T7 and T3 have another restriction protection protein Ocr which also prevents EcoK and EcoB restriction.41 The T7 ocr gene codes for a DNA mimic protein that irreversibly binds to the active site of the Type I EcoK restriction enzymes.42 The T7 Ocr protein is homologous to a variety of other phage proteins but has no similarity to proteins of T5-like phages. Ocr is inactive against Type II R-M enzymes such as EcoRI.

In the hope of identifying the T5 restriction protection system, mutants were isolated that are unable to grow on an EcoRI restricting host.3,4 Analysis of the DNA of such mutants shows that they have each acquired one new EcoRI site in each terminal redundancy as a consequence of a new single EcoR1 site (ris) mutation (ris originally meant EcoRI insensitive− but, for reasons given below, it now means EcoRI site). The ris1, ris 2, and ris3 sites are widely spaced on the FST DNA (Fig. 1) and are not situated in a single gene; and thus are not located in the hypothetical restriction protection gene. One mutation, ris1, is located in the A1 gene and exhibits exclusion by the rex genes in a λ lysogen; a known characteristic of some A1 mutants. However this is fortuitous, since revertants of ris1 (able to escape restriction by EcoRI) may be either sensitive or resistant to rex exclusion. Conversely ris1 revertants that escape rex exclusion may be either resistant or sensitive to EcoRI restriction. The ris1, ris2, and ris3 mutations, located on the FST DNA, differ from the natural EcoRI sites in that the latter are situated on the SST DNA, whereas the former are on the FST DNA. This suggests that the in vivo EcoRI sensitivity of ris mutants is a consequence of having an EcoRI site on the FST DNA. This is understandable if the hypothetical restriction protection gene(s) is located on the FST DNA. While expression of the FST restriction protection gene(s) would protect natural sites on the SST DNA, the FST region carrying the ris sites, on the contrary, enters an environment in which the protection protein has not yet been expressed.

Comparison of the ris1, ris2, and ris3 mutants with λ is interesting. A λ mutant carrying only one EcoRI restriction site shows a plating efficiency on a restricting host of only about 10−1. In contrast, the ris1, ris2, and ris3 mutants (which may formally be considered as having only one EcoRI site more than T5+ on the FST DNA) show a plating efficiency of 10−3 to 10−4. This may be due to the fact that T5 DNA ris does not become modified and thus it is completely restricted and only true revertants can survive. In contrast, unmodified λ is only restricted during the first infection in plaque formation and those that escape restriction become modified and are no longer restricted.

Construction of double and triple ris mutants allowed the ordering of the ris sites and correlation with the already established genetic map of this region43 (Fig. 1). A fourth ris mutant (ris4) was fortuitously isolated as a double ris1-ris4 mutant. When the ris4 mutation was separated from ris1 by recombination, it was found to be insensitive to in vivo EcoRI restriction (as are the natural EcoRI sites located on the SST DNA). In fact the ris4 mutation is located to the right of the injection stop signal and thus is on the SST part of the LTR. This confirms the hypothesis that only EcoRI sites on the FST DNA are sensitive to EcoRI restriction.

The logic in isolating mutants of T5 that are sensitive to restriction by EcoRI was that such mutants would be defective in the restriction protection gene. Since the mutants obtained all carried new EcoRI sites in the FST region, and since these mutations were too widely spaced to fit into a single gene it is obvious that the search for the restriction protection gene failed. Obviously the target size of a 6 bp EcoRI site is very much smaller than a gene and yet the EcoRI sensitive ris mutants all resulted in a new EcoRI site rather than a mutant gene. It seems likely that mutants in the restriction protection protein must be lethal and that the restriction protection protein may have another important function. It was suggested43 that protection against EcoRI restriction is a (secondary) consequence of the mechanism of protection of T5 DNA against the nuclease(s) that degrade the host DNA early in infection, and perhaps against RecBCD nuclease (discussed above). The T5 literature provides no information regarding the nature of this nuclease that degrades host DNA (for example whether it is phage or host coded), nor the mechanism of protection of T5 DNA from this nuclease(s). Following this hypothesis, the same protection mechanism would also protect against restriction enzymes and against modification.43 A unifying hypothesis would be that T5 protects its DNA from degradation using a DNA binding protein that protects it from the enzymes that degrade host DNA and also from host restriction enzymes. According to this hypothesis this essential protection protein would be coded by the FST region, probably by one of the small unknown ORFs, and would have escaped the original search for amber mutants in T5. It would not have been found during the search for ris mutants since the absence of the protection product would be lethal. It is noted from the analysis of ORFs in T5-like phages (Table 2, discussed below) that products of ORFs 02, 05, 06 (A2) and 08 are conserved in evolution and are possible candidates for coding for the DNA protection protein. The hypothesis leaves unanswered the mechanism whereby this protection protein differentiates host DNA (unprotected) from T5 DNA (protected), but the answer may lie in the mechanism of injection. It is possible that T5 left LTR terminus remains attached to the host membrane while awaiting the arrival of the SST DNA. In such a position it could be protected from exonucleases (like the RecBCD exonuclease) and then form a circle by recombination between the LTR and the RTR, when the RTR terminus arrives about 5 minutes later.

Table 2.

Presence of T5 LTR protein homologs in the T5-like phages

| T5 | FFH1 | SPC35 | phiR201 | AKFV33 | Shivani | DT57C | Stitch | EPS7 | My1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein/aa | ||||||||||

| T5p01 dmp 244 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T5p02 131 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| T5p03 92 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| T5p04 A1 556 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T5p05 65 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/− |

| T5p06 A2 135 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T5p07 83 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| T5p008 67 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| T5p009 Endo 172 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| T5p010 37 kDa 336 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| T5p011 87 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| T5p012 59 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| T5p013 70 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| T5p014 114 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| T5p015 92 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| T5p016 67 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| End LTR | === | === | === | === | === | === | === | === | === | === |

| T5p017 33.8 kDa 294 | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

Protein homology searches were performed using the Paris-Orsay sequence (accession number AY692264.1) using BlastP program of the NCBI database.

A related possibility is that T5 DNA carries a protective protein against exonucleases (which could be an early or late gene product) that is attached to its ends, into the cell at the moment of injection. This terminal protein would protect T5 DNA from exonucleases until circle formation took place. It is noted that the DNA of T4, P22 and Mu carries such a terminal protective protein attached to the end of the DNA in the capsid and injected together with the genome.44-47 There is no evidence for, or against, the existence of such a protein in T5. An attractive feature of both variants of this hypothesis is that they allow for protection from exonucleases but not from endonuclease such as EcoR1; thereby explaining why FST DNA carrying an EcoRI site is attacked.

A quite different mechanism could be proposed, based on the properties of the Ocr anti-restriction protein of T7. Ocr acts as a DNA mimic protein binding irreversibly to Type I restriction/modification enzymes, such as EcoK and EcoB. Ocr has no effect on Type II restriction enzymes such as EcoRI. However, an Ocr-like DNA mimic protein acting on EcoRI could explain the lack of restriction and modification of T5 DNA. The Ocr-like function hypothesis is attractive since it could be extended further. One could imagine that the Ocr-like function works to inhibit both EcoRI and EcoK restriction and modification systems. Thus T5 phage DNA in the capsid would be unmodified for both EcoRI (as demonstrated in)4 and EcoK. If a mutant in the ocr-like gene was obtained, then the mutant would be lethal under the conditions used to isolate the ris mutants since these were isolated on an EcoRI deficient but EcoK proficient host. The ocr-like mutants would thus be degraded by the EcoK restriction enzymes. In retrospect, according to this hypothesis, in order to obtain such mutants it would have been necessary to use an EcoRI−−EcoK− host. This hypothesis thus also satisfactorily explains why no mutants defective in the protection from EcoRI endonuclease were ever obtained. However the Ocr-like hypothesis does not explain the protection of T5 DNA from the enzyme(s) responsible for host degradation, so these 2 functions would need to be independent.

The other T5 FST ORFs

With the exception of ORF09, which potentially codes for a HNH homing endonuclease (discussed below), none of the other FST putative proteins have similarity to any proteins in the NCBI database.

The inhibitors myth

There was a long time lag between the genetic and biochemical analyses of T5 in the 1960s-80s and the nucleotide sequencing of T5, in 2006, and, because of this, some serious errors of interpretation have crept into the literature. Wang et al.6 reporting the sequence of T5, introduced the concept of 'inhibitors' as the functions of rightward transcribed ORFs 12 to 17, incorrectly citing McCorquodale et al. (1977), which in fact makes no such assertion. Unfortunately, the “inhibitors” nomenclature has since been propagated by other authors, without further experimental justification. As a general rule, a protein must be shown to inhibit something before it can be described as an inhibitor.

The FST region of phages related to T5

The nucleotide sequence of several newly isolated T5-like phages has recently been determined and these closely resemble T5 in genome structure such as size and large terminal repeats and general genomic structure. Given that among the 16 ORFs of the T5 FST region only 3 contain genes with mutationally identified phenotypes (dmp, A1 and A2), it was interesting to compare the T5 FST region to the corresponding region of related T5-like phages. There are 11 such sequenced phage genomes in the NCBI databases: Escherichia phage T56,15,16; Escherichia phage vB_EcoS_FF48; Salmonella phage SPC35,49 Yersinia phage phiR2050; Escherichia phage EPS748; Escherichia phage AKFV3351; Salmonella phage Shivani52; Enterobacteria phage DT57C53; Enterobacteria phage DT571/254; Salmonella phage Stitch,55 Pectobacterium phage My1.56 These phage names are cumbersome to use and so the T5-like phages will be referred to only by their last names and by their accession numbers as shown in Table 2. DT571/2 and DT57C are essentially identical over the LTR region and thus only DT57C was chosen as the representative. The FST sequence of BF23 is largely unknown and so cannot be included in this comparison.

Essential genes are likely to be maintained in evolution while non-essential ORFs are likely to be lost. It must be clear, however, that arguments of this type carry a danger in that, apart for T5 and BF23, none of these phages have been analyzed genetically or biochemically. Thus, there is no hard evidence that these phages (for example) carry out a 2-step transfer, degrade host DNA, are insensitive to restriction, have nicks etc. However the genome comparisons given below encourage belief that this may be so.

Although phage BF23 has not been completely sequenced, it is of importance in that it greatly resembles T5 and is the only T5-like phage that has been studied genetically and biochemically. In particular, one deletion mutant lacks the region from 0.044% to 0.078% of the LTR.12 If these BF23 coordinates are directly translated into T5 coordinates then this deletion mutant would lack the region 5357 to 9496 which includes ORFs 9 to 16 and part of the non-coding region (Fig. 1). Thus, this region does not encode essential functions, at least in BF23.

Leftward transcribed proteins

A comparison of the putative proteins encoded by FST ORFs for T5-like phages is given in Table 2. For the leftward transcribed ORFs, it can be seen that all T5-like phages encode the proteins by the 3 already known genes of the T5 LTR; dmp (T5p01), A1 (T5p04) and A2 (T5p06). Putative protein T5p02 is coded in all phages except My1. All T5-like phages code for hypothetical proteins T5p04, T5p05, T5p07. All T5-like phages, except T5, lack T5p03. T5p08 is present in all T5-like phages except EPS7 and DT57C (which has a large deletion covering ORF8 through 11).

The T5 putative HNH homing nuclease of ORF09 is also present in FFH1 and Shivani but absent in all T5-like phages. HNH endonuclease genes are selfish DNA elements present in many phages and bacteria. HNH endonucleases are site-specific DNA endonucleases that initiate mobility by introducing double-strand breaks at defined positions in genomes lacking the endonuclease gene. In phage T4 they comprise an astonishing 11% of the genome.57 There are 2 other HNH endonucleases in the SST region of T5.6 Shivani carries 3 HNH homing endonucleases in the LTR region; one between dmp and A1, another in the same position as T5, and the third in the non-coding region (data not shown).

Rightward transcribed ORFs

For the rightward transcribed ORFs the situation is much more variable than the leftward transcribed ORFs; indeed the variability almost defies description. There is not a single rightward ORF protein that is present in all T5-like phages (Table 2). Phage DT57C has the shortest LTR and lacks adjacent ORFs 8 through 11 due to a deletion in the DNA for this region. Phage My1 is the most evolutionary distant of the T5-like phage group and has the largest LTR. It is unlike the other T5-like phages in that it lacks most rightward transcribed ORFs. In contrast, phage My1 carries a considerable number of additional leftward transcribed small ORFs that have no relationship with any proteins in the NCBI database.

The rightward transcribed proteins of T5-like phages can be classified into 4 types: those having homology to T5; those having homology to other T5-like phages but not T5; those having homology to other proteins from phages or bacteria but not T5-like phages; and those having no homology to any protein in the NCBI databases. No consistent pattern can be ascribed to the rightward transcribed ORFs, which present a very confusing picture. One could be almost tempted to suggest that these rightward transcribed ORFs serve no useful functions and simply serve to provide enough DNA to make the LTR region a certain size; perhaps to provide homology for circularization via recombination.

The non-coding region and the iss signal

Phage T5 has a large non-coding region (1779 bp) between the leftward transcribed ORF16 and the rightward transcribed ORF17 (Fig. 1). This non-coding region contains the right end of the LTR and continues into the unique genome. Phages, in general, are usually very economical in the use of their DNA and non-coding regions of this size are unusual. This region is also present in the other T5-like phages and, perhaps contrary to what might be expected for a non-coding region, there is considerable DNA homology between the non-coding regions of the T5-like phages which might indicate a structural importance. This is interesting in view of the observation that this region must contain the injection stop signal (iss)11 (next section). In addition to the iss, 2 other interesting sites are in this region. It is known that the leftmost nick is in the non-coding region.11 Finally, logically (but not scientifically demonstrated), the region around the junction LTR and RTR should contain the T5 terminase substrate which acts as a signal for DNA packaging from T5 concatemeric molecules. There are no reports of the nature of the terminase substrate in T5.

The T5 injection stop signal

A deletion mutant of phage BF23 was isolated that lacked about half of the FST region and the FST DNA transferred was shown to be correspondingly shorter. From this it was concluded that the FST region is defined by a signal on the DNA; rather than by a fixed length of DNA transfer.12 Heusterspreute and Davison11 hypothesized that the injection stop signal (iss) could be due to special nucleotide sequence on the DNA and the region potentially containing iss could be calculated and then cloned and sequenced. The iss region showed a bewildering array of repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes.11 These observations were later confirmed and extended by determining the nucleotide sequence of the entire T5 molecule. In this publication the nomenclature of Wang et al.6 for the repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes, will be used. No analysis of the non-coding region has ever been attempted since it contains no genes and since modification of important cis-acting sites would probably be lethal. However the recent nucleotide sequencing of several T5-like phages provides an opportunity to ask new questions as to the significance of these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes. If these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes serve no important functions in phage T5 and other T5-like phages, then it would be expected that they would be lost by genetic drift during evolution; particularly since a non-coding region would not have the constraints of coding for essential gene functions. In contrast, important non-coding motifs (such as iss and the terminase substrate) should be maintained since they must (presumably) interact with phage and/or host proteins.

It is a reasonable supposition that iss is situated to the left of the shear point at +/− 9740 that breaks off the SST DNA in the blender. It may be argued that iss is a sequence that interacts with the host membrane/proteins and already inside the host cell at the time of shear. The presence of the repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes was thus investigated in all T5-like phages. However, it would not be reasonable to look for exactly the same nucleotide sequence as that of T5 since cis-acting DNA motifs are usually variable. For example, promoters and ribosome binding sites are important conserved cis-acting structures that show considerable variation around a common theme. Thus repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes were compared between the 10 T5-like phages (Table 3) using the Fuzznuc program58-60 that allows retrieval of sequences with a pre-defined maximum number of mismatches. It was arbitrarily decided that a 10% mismatch would be permitted and this figure was upgraded to the next whole number; for example a 42 bp sequence was permitted 5 mismatches.

Table 3.

Comparison of direct repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes in T5-like phages

| Phage | Phage T5 | phage FFH1 | phage SPC35 | phage phiR201 | Phage AKFV33 | phage Shivani | phage DT57C | Phage Stitch | Phage EPS7 | phage My1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input sequence | Name/ Length bp | Accession N° | AY587007.1 | KJ190157.1 | HQ406778.1 | HE956708.1 | HQ665011.1 | KP143763.1 | KM979354.1 | KM236244.1 | CP000917.1 | JX195166.1 |

| atttgggaagatttgag | Direct repeat A copy 3 17 bp | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 1(1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| ctggggataagtctgttgataac | Direct repeat B 23 bp | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| ttttaaatacgaatcattatcattc | Direct repeat C 25 bp | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| tgtgcaaatccgaca | Direct repeat D 15 bp | 10 (12) | 9 (12) | 9 (12) | 8 (14) | 10 (13) | 6 (9) | 8 (11) | 11 (14) | 9 (12) | 6 (8) | |

| agtgagaaacactgttatttaa-gttatccacagacttat | Inverted repeat C' 39bp | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| acagacttatccccaggtta-tcctactgtatatttatacag | Inverted repeatD' 41 bp | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| gacggggatcagctccccgt | Palindrome C 20 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | |

| tactgtataaatatacagta | Palindrome D 20 bp | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| aatacgaatcattatcattcgtatt | Palindrome E 25 bp | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| aatcattatcattcgtattccgctt-tttaaatgagaatcatt | Palindrome F 42 bp | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| aaatgagaatcattatcattt | Palindrome G 21 bp | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | |

| aaatgagaatcattatcatttg-catttcactttttaaatga-gattgattctcatta | Palindrome H 56 bp | 1 (1) | 0 (0 | 0;0 | 0;0 | 1;1 | 0;0 | 0;0 | 0;0 | 0;0 | 0;0 | |

| aatgagattgattctcatta | Palindrome I 20 bp | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| gcaggcaattgccctgc | Palindrome J 17/2 bp | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

The presence of direct repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes of T5 present in the 9000- 13,500 region6 was verified for the complete LTRs of other T5-like phages (taking into account the differences in the size of the LTRs). The nomenclature follows that of Wang et al.6. Comparisons were made using the Fuzznuc program provided by Galaxy https://usegalaxy.org/. The maximal of permitted mismatches corresponds to 10% of the input sequence upgraded to the nearest whole number. The numbers in the table show the number of times that sequence is present in the T5 1-14,000 bp region and corresponding regions of other phages. For comparison, the numbers in parentheses show the number of times that sequence is present in the entire genome (including the LTR but excluding the RTR). The sequences shown in bold are present in all T5-like phages and were chosen for further analysis (shown in Fig. 2). Direct repeat B was not chosen since it is a subset of inverted repeat D′. Palindrome I was not chosen since it is a subset of palindrome G.

Phage T5 has many repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes and these are mainly clustered in 2 regions: 1) from 4.5 to 6.5 kb and 2) from 9.0 to 10.5 kb6. The latter cluster corresponds to the postulated region containing the iss sequence and the terminase substrate.11 The results, shown in Table 3, demonstrate that some of these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes are not present in all T5-like phages; whereas others are present in multiple copies in all T5-like phages. The latter (marked in bold on Table 2) are possible candidates for being part of the iss and terminase substrate sequences. It should be noted that these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes are present only in the terminal repeats of the T5-like phages and not present in the remainder of the genome. It was thus interesting to investigate whether the positions and the order of these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes are also conserved on the T5-like genomes.

The positions of likely iss candidate sequences were arranged graphically (Fig. 2). It can be seen that the size of the LTR varies considerably with a difference of 4770 nucleotides between the smallest T5-like genome (DT57C) and the largest (My1). For this reason it is easiest to consider the position of the repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes relative to the right end of the LTR (marked by ▴), rather from the left end of the LTR (which is more distant). Despite the divergence in size and genomic structure, the candidate repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes maintain similar positions in their respective genomes relative to each other and to the position of the right end of the LTR. Importantly there is also an order to the candidate sequences (Fig. 2); so that a pattern of the sequences can easily be visually detected in the region of about from 1000 bp to the left of the right end of the LTR and from 200 bp to the right of the right end of the LTR (T5 coordinates 9219–10410):

Figure 2.

Direct repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes in T5-like phages. The region 1 to 14,000 is shown for all T5-like phages, together with positions of the repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes from Table 3. Symbols are: direct Repeat D 15 bp, +; right end of LTR, ▾; palindrome G 21 bp, ○; inverted repeat D' 41 bp, □; palindrome D 20 bp, ◊; inverted repeat C' 39 bp, *. The repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes are sequences of DNA but are plotted as points since, on this scale, the difference cannot be noticed.

○ ◊□ * ○○○ ++++++ ▴ ++ +

These symbols correspond to: +, direct repeat D (15 bp); ▴, right end of the LTR; ○, palindrome G (21 bp); *, inverted repeat C' (39 bp); □, inverted repeat D' (41 bp); ◊, palindrome D (20 bp). (◊ and □ are often closely linked since palindrome D is often part of the larger inverted repeat D').

Thus it can be concluded that despite considerable genomic evolutionary divergence, these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes have maintained their presence and positions relative to the right end of the LTR. This observed sequence conservation does not permit the conclusion that these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes are part of iss or the terminase substrate. All that can be concluded is that these sequences are conserved in evolution and thus some are likely to be part of some important function of all T5-like phages. They are also located in the region where one would expect to find iss and the terminase substrate. In particular palindrome G (21 bp); *, inverted repeat C' (39 bp); □, inverted repeat D' (41 bp); ◊, palindrome D (20 bp) are particularly well positioned to function as part of iss; being to the left of the shear breakpoint (+/-nucleotide 9740).

Wang et al.6 described 2 clusters of direct repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes and these can also be seen in Figure 2. One cluster (considered in the previous paragraph) at about 9 kb from the left end of the LTR and another smaller cluster at about 6 kb from the left end of the LTR. The former cluster is in a position that would give a FST region of about the correct size, while the latter is not. Rogers et al.65 while investigating FST of wild type T5 region noticed 2 bands in wild-type T5; one at about 9 kb and the other at about 5.8 kb. The first corresponds to the normal FST region. No explanation could be given for the 5.8 kb band; but curiously it corresponds to the position of the second cluster of direct repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes at 6 kb (Fig. 2). This could raise speculation as to whether FST transfer itself takes place in 2 steps. On the other hand, no second FST band of about 5.8 kb was observed by others.11 The difference could perhaps be due to the exact protocol used, or to an artifact of that particular experiment. However, in view of the positions of the clusters, it would be interesting to investigate further.

In an attempt to analyze the iss region, a 757 bp fragment containing iss was cloned into λ but this resulted in miniscule plaques. Deletion of a 68 bp region carrying 2 of the 3 members of the palindrome G family restored normal plaque size.11 However there was no proof that the miniscule plaque size was due to the presence of the T5 iss causing the problems in lambda phage injection. It would be interesting to explore this phenomenon further using modern techniques.

Direct repeats D

Direct repeats D (tgtgcaaatccgaca) are different from the other repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes for several reasons. Firstly, they are very frequent among all T5-like phages (6–13 copies per genome). Secondly, most, but not all, are situated in the region overlapping right end of the LTR and the left part of the unique genome; in a position where they cannot be part of iss but could be part of the terminase substrate (discussed below). Thirdly, there are direct repeat D-like sequences (generally 2 or 3) elsewhere in the SST DNA in loci that cannot have anything to do with iss or the terminase substrate. In particular, T5 has 2 copies direct repeat D-like sequences in tandem, at positions corresponding to T5 coordinates 79019 to 79048. Curiously, this tandem direct repeat D-like sequence is present at the equivalent positions in all other T5-like phages (except My1). This conservation indicates an (unexplained) importance of this sequence.

The leftmost T5 nick

The presence of nicks of phage T5 has fascinated molecular biologists and resulted in a great many publications. Major nicks occur with high frequency at 5 sites on the 3′ to 5′ strand, while the 5′ to 3′ strand is intact. Other nicks are present with a variable frequency at a variety of secondary sites. The subject of T5 nicks is outside of the scope of the present article since the nicks are produced by late proteins. However, the leftmost nick is within the non-coding region of interest and its position was determined to be at position 9670 on the T5 genome.11 Because of its position, the leftmost nick initially seemed a good candidate for both the iss and/or for the shear-sensitive site that breaks when the FST phage/bacterium complex is subjected to shear in the blender. However this is not the case.

To investigate the function of the major nicks, Rhoades et al. (1979)61 isolated site mutants in which one or more of the major nicks were absent. Recombinants could be isolated in which the nick site mutants were assembled on the same genome so that a T5 genome totally lacking nicks could be produced. These nick-free recombinants had full viability and a mutant lacking the nick in the FST region showed normal 2-step DNA transfer.62 T5 mutants were also found in two genes, sciA and sciB responsible for nick formation, in which all of the nicks were absent. These sciA and sciB mutants showed full viability and had no effect on FST injection. Rhoades65 concluded “at least under laboratory conditions the nicks are not necessary for growth or second step transfer.”

The terminase substrate

When the iss concept was proposed in 1987,11 the concept of a terminase substrate was in its infancy in phage λ and had not been considered at all in phage T5. Even today there are only 2 publications that refer to the T5 terminase.63,64 These identified the small DNA binding subunit and the large endonuclease subunit of the terminase enzyme; but did consider the nature of the terminase substrate. Maturation of T5 DNA phage depends on its packaging into the phage capsid and for this the DNA molecule must be of the right size and carry the correct left and right ends. In phages λ, packaging is achieved by a terminase (consisting of 2 subunits: a small DNA binding subunit and a large catalytic subunit) that cleaves the DNA into the correct size at the terminase substrate (cos),

The mode of T5 DNA replication is poorly understood and the substrate and the mechanism of action of the terminase remain unknown. However, by comparison to other phages, the substrate is likely to be concatenated T5 DNA, which is known to be produced during T5 DNA replication. Such concatenates could be produced by a rolling circle type replication, from circular molecule formed by recombination between the terminal repeats of T5 DNA.65 Both types of molecules were observed by electron microscopy: circular monomers that were shorter than unit length T5 by the size of one terminal redundancy and very long concatenated molecules.66,67 Evidence that terminal repeats do recombine was provided by the observation that phage coming from genetic crosses between A1 and A2 mutants were often heterozygotes originally carrying both mutant and wild-type alleles on different terminal repeats.68

Circle T5 molecules shorter than unit length T5 by the size of one terminal redundancy could be generated by the T5 general recombination system and this would automatically eliminate the right end of the RTR, as well as the left end of the LTR; thus deleting both the right and the left ends of the genome. Thus, the hypothetical pac substrate could only come from the recombinationally generated hybrid region containing the right end of the LTR and the left end of RTR.

Thus it seems logical, and simple, that the terminase would cleave the terminase substrate (which I will name pac) on the concatenated molecule in this region to generate a complete T5 genome. However in order to re-generate the LRT and the RTR, terminase must cleave at 2 different positions; once to generate the left end of the genome and once to generate the right end. It is interesting to note that this imagined mode of replication and packaging would be highly inefficient since it would waste 80% of a genome for every genome packaged. An alternative possibility would be the regeneration of the T5 10 kb terminal repeats by RNA polymerase and DNA polymerase at the time of packaging; as has been postulated for T7,69 where the terminal repeats are nonetheless very much smaller (160 bp). There is no evidence to support either suggestion.

A NCBI Blast search of all T5-like phages against the region comprising the rightmost 100 nucleotides of the LTR (coordinates 10039 to 10139) and the first 100 nucleotides of the unique region immediately to the right of the LTR (coordinates 10139 to 10239) of T5 shows near identical homology for all T5-like pages (except phage My1). These homologous regions are consistent with the hypothesis of a pac sequence, conserved between T5-like phages, that functions on a concatenated molecule to generate the T5 right end. Direct repeat D is present in multiple copies (6 to 10) in all T5-like phages and these are located in this conserved region, just before, and just after, the right end of the LTR; and thus in the position of the putative pac site. Only experimentation can reveal the significance of these repeats.

This hypothesis leaves unclear the mechanism generating the left end of the genome. A homology search among the T5-like phages for the region immediately to the left of the RTR revealed no similarity. Indeed this region contains the T5 oad gene that codes for the pb5 tail protein and this region is non-homologous in BF23, which codes for a different non-homologous tail protein hrs which has a different host range.70

Discussion

This review summarizes the state of scientific research on the pre-early and FST region of phage T5 and its relatives. The present discussion will attempt to summarize the problems of phage infection and to propose possible hypotheses to resolve poorly understood issues. T5 has 16 putative pre-early ORFs but only 3 (dmp, A1, A2) have been identified genetically and only A1 and A2 have been shown to be essential for phage viability. Given the multiple phenotypes shown on T5 infection (first step transfer, second step transfer, host DNA degradation, inhibition of host RNA and protein synthesis, restriction insensitivity and protection of T5 DNA) there seem to be too many unrelated effects for only 2 genes. Thus it is likely that some other pre-early ORFs have important functions and that these were missed during the initial mutant screening, performed more than 50 y ago. In particular, some T5 leftward transcribed ORFs (particularly ORFs 02, 05, 07) are conserved in all 10 T5-related phages. Using modern technologies such as site directed mutagenesis, CRISPR/cas9 or recombineering, it should be possible to modify these ORFs by the introduction of an amber mutation in order to determine the effect on T5 viability. The amber mutants could then be transferred to phage λ so that the effect of individual ORFs on cell viability and phage infection could be determined separately or together (by mixed infection). It would be of particular interest, in this respect, to clone an amber mutant version of the A1 gene (which, unlike A2, has never been cloned in E. coli) into λ so that the multiple phenotypes of the A1 gene may be explored.

In contrast to the leftward transcribed ORFs, the T5 rightward transcribed FST ORFs show no such virtually conservation among the T5 related phages.

A region of T5 DNA, containing numerous repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes, was previously identified as containing the putative T5 DNA injection stop signal iss where the injection of the first-step transfer DNA stops. Several of these repeats, inverted repeats and palindromes could also be identified in similar positions in the 10 T5-related phages, indicating an important function that is conserved in evolution.

T5 is insensitive to the presence of Type I, Type II and Type III restriction/modification systems in the host, being neither restricted nor modified. The gene responsible restriction protection has not been identified. T5 mutants sensitive to EcoRI restriction were not defective in the restriction protection gene but has acquired EcoRI restriction site in the FST region.

A possibly related effect is the mechanism of self-protection of T5. Very early in T5 infection the host DNA is degraded to nucleosides which are excreted from the cell rather than being incorporated into phage DNA. Whether this degradation is due to host or phage coded nucleases is unknown. T5 DNA has no obvious chemical differences with the host DNA and yet it is not degraded. Again the mechanism of protection remains unknown.

Finally, T5 must (logically) contain a terminase substrate (pac), located immediately to the left and right of the right end of the LTR, which would interact with the phage encoded terminase enzymes to generate the ends of the DNA for packaging. This region is highly conserved among T5-like phages and contains a conserved direct repeat sequence in multiple copies in of all T5-like phages.

Conclusion

To quote Jon R. Sayers in 20042: “Most of the questions about T5 biology, first posed 30 or more years ago, remain unanswered” and the situation has changed little in the 11 y since this article was written. In this review, specific experimental suggestions are made as to how some of the unresolved questions may be approached. I hope that future research, using new techniques not available 50 y ago, will elucidate these problems.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

I dedicate this review to Harrison (Hatch) Echols (1933–1993) who taught me about phages. I thank Valérie Meyrial and Peter Terpstra for help and useful discussions.

References

- 1.Lanni YT. First-step-transfer deoxyribonucleic acid of bacteriophage T5. Bacteriol Rev 1968; 32:227-42; PMID:4879238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayers JR. Bacteriophage T5 In: Calendar R. (Ed) The bacteriophages. NY: Oxford University Press; 2006; 268-76. ISBN 0-19-514850-9 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison J, Brunel F. Restriction insensitivity in bacteriophage T5. I. Genetic characterization of mutants sensitive to EcoRI restriction. J Virol 1979; 29:11-16; PMID:430589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison J, Brunel F. Restriction insensitivity in bacteriophage T5. II. Lack of EcoRI modification in T5+ and T5ris mutants. J Virol 1979; 29:17-20; PMID:430591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrickson H, McCorquodale DJ. Genetic and physiological studies of bacteriophage T5 I. An expanded genetic map of T5. J Virol 1971; 7(5):612-8; PMID:16789131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Jiang Y, Vincent M, Sun Y, Yu H, Wang J, Bao Q, Kong H, Hu S. Complete genome sequence of bacteriophage T5. Virology 2005; 332:45-65; PMID:15661140; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw AR, Davison J. Polarized injection of the bacteriophage T5 chromosome. J Virol 1979; 30:933-935; PMID:480474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Böhm J, Lambert O, Frangakis AS, Letellier L, Baumeister W, Rigaud JL. FhuA-mediated phage genome transfer into liposomes. A cryo-electron tomography study. Curr Biol 2001; 11:1168-1175; PMID:11516947; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00349-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertin A, de Frutos M, Letellier L. Bacteriophage–host interactions leading to genome internalization. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011; 14:492-496; PMID:21783404; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershey AD, Chase M. Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in the growth of bacteriophage. J Gen Physiol 1951; 36:35-56; PMID:12981234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heusterspreute M, Ha-Thi V, Tournis-Gamble S, Davison J. The first-step transfer-DNA injection-stop signal of bacteriophage T5. Gene 1987; 52:55-164; PMID:3038680; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90042-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw AR, Lang D, McCorquodale DJ. Terminally redundant deletion mutants of bacteriophage. J Virol 1979; 29:220-31; PMID:430593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mozer TJ, Thompson RB, Berget SM, Warner HR. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriophage T5 mutant deficient in deoxynucleoside 5′-monophosphatase activity. J Virol 1977; 24:642-50; PMID:335083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner HR, Drong RF, Berget SM. Early events after infection of escherichia coli by bacteriophage T5 I. Induction of a 5′-nucleotidase activity and excretion of free bases. J Virol 1975; 15(2):273-80; PMID:163355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zivanovic Y, Boulanger P, Confalonieri F, Dutertre M, Decottignies P, Del Castillo G. Bacteriophage T5 strain st0 deletion mutant, complete genome. 2004; NCBI Accession number AY692264.1 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ksenzenko VN, Kaliman AV, Krutilina AI, Shlyapnikov MG. Bacteriophage T5, complete genome. 2004; NCBI Accession number AY543070.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AY692264.1 [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCorquodale DJ, Shaw AR, Shaw PK, Chinnadurai G. Pre-early polypeptides of bacteriophages T5 and BF23. J Virol 1977; 22:480-8; PMID:325230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davison J, Lafontaine D. Direction of transcription in bacteriophage T5 first-step transfer DNA. J. Virol. 1984; 50, 629-31; PMID:6323763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacquemin-Sablon A. Lambda-repressed mutants of bacteriophage T5. II. Physiological characterization. J Mol Biol 1979; 135:545-63; PMID:231679; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90163-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCorquodale DJ, Chen CW, Joseph MK, Woychik R. Modification of RNA polymerase from Escherichia coli by pre-early gene products of bacteriophage T5. J Virol 1981; 40:958-62; PMID:7033565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szabo C, Moyer RW. Purification and properties of a bacteriophage T5-modified form of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Virol 1975; 15:1042-6; PMID:1090747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duckworth DH, Dunn GB, McCorquodale DJ. Identification of the gene controlling the synthesis of the major bacteriophage T5 membrane protein. J Virol 1976; 18 542-9; PMID:775127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill JJ, Berry JD, Russell WK, Lessor L, Escobar-Garcia DA, Hernandez D, Kane A, Keene J, Maddox M, Martin R, et al.. The Caulobacter crescentus phage phiCbK: genomics of a canonical phage. BMC Genomics 2012; 13:542 PMID:23050599; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-13-542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder CE Jr, Benzinger RH. Second-step transfer of bacteriophage T5 DNA: purification and characterization of the T5 gene A2 protein. J Virol 1981; 40:248-57; PMID:72889242059212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder CE, Jr. Amino acid sequence of the bacteriophage T5 gene A2 protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1991; 177:1240-6; PMID:2059212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snyder CE, Jr. 1984. Bacteriophage T5 gene A2 protein alters the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 1984; 60:1191-5 PMID:6389511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duckworth DH, Glenn J, McCorquodale DJ. 1981. Inhibition of bacteriophage replication by extrachromosomal genetic elements. Microbiol Rev 45:52-71. Plasmid; PMID:6452572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hull R, Moody EE. Isolation and genetic characterization of Escherichia coli K12 mutations affecting bacteriophage T5 restriction by the ColIb plasmid. J Bacteriol 1976; 127:229-36; PMID:776926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunel F, Davison J, Merchez M. Cloning of bacteriophage T5 DNA fragments in plasmid pBR322 and bacteriophage lambda gtWES. Gene 1979; 8:53-68; PMID:535730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davison J, Brunel F, Merchez M. A new host-vector system allowing selection for foreign DNA inserts in bacteriophage lambda gtWES. Gene 1979; 8:69-80; PMID:231542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dillingham MS, Kowalczykowski SC. RecBCD enzyme and the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2008; 72:642-71; PMID:19052323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benzinger R, Enquist LW, Skalka A. Transfection of Escherichia coli spheroplasts. V. Activity of recBC nuclease in rec+ and rec-spheroplasts measured with different forms of bacteriophage DNA. J Virol 1975; 15:861-71; PMID:123277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaki Y, Karu AE, Linn S, Echols H. Purification and properties of the gamma-protein specified by bacteriophage lambda: an inhibitor of the host RecBC recombination enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1973; 70:2215-9; PMID:4275917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakaki Y. Inactivation of the ATP-dependent DNase of Escherichia coli after infection with double-stranded DNA phages. J Virol 1974; 14:1611-2; PMID:4610190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behme MT, Lilley GD, Ebisuzaki K. Postinfection control by bacteriophage T4 of Escherichia coli recBC nuclease activity. J Virol 1976; 18:20-5: PMID:130501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benzinger R, McCorquodale DJ. Transfection of Escherichia coli spheroplasts. VI. Transfection of nonpermissive spheroplasts by T5 and BF23 bacteriophage DNA carrying amber mutations in DNA transfer genes. J Virol 1975; 16:1-4 PMID:805845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chernov AP, Kaliman AV. Various characteristics of the anti-restriction mechanism in bacteriophage T5. Mol Gen Mikrobiol Virusol 1987; 1:14-9; PMID:3031490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samson JE, Magadán AH, Sabri M, Moineau S. Revenge of the phages: defeating bacterial defences. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013; 11:675-87; PMID:23979432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Studier FW, Movva NR. SAMase gene of bacteriophage T3 is responsible for overcoming host restriction. J Virol 1976; 19:136-45 PMID:781304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hausmann R. Synthesis of an S-adenosylmethionine-cleaving enzyme in T3-infected Escherichia coli and its disturbance by co-infection with enzymatically incompetent bacteriophage. J Virol 1967; 1:57-63; PMID:4918233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruger DH, Bickle TA. Bacteriophage survival: multiple mechanisms for avoiding the DNA restriction systems of their hosts. Microbiol Rev 1983; 47:345-60. PMID:6314109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atanasiu C, Byron O, McMiken H, Sturrock SS, Dryden DTF. Characterisation of the structure of Ocr, the gene 0.3 protein of bacteriophage T7. Nucl Acids Res 2001; 29:3059-68; PMID:11452031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunel F, Davison J. Restriction insensitivity in bacteriophage T5. III. Characterization of EcoRI-sensitive mutants by restriction analysis. J Mol Biol 1979; 128:527-43; PMID:374742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chase CD, Benzinger RH. Transfection of Escherichia coli spheroplasts with a bacteriophage Mu DNA-protein complex. J Virol 1982; 42:176-85; PMID:6211551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akroyd JE, Symonds N. Localization of the gam gene of bacteriophage Mu and characterization of the gene product. Gene 1986; 49:273-82; PMID:2952555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Appasani K, Thaler DS, Goldberg EB. Bacteriophage T4 gp2 interferes with cell viability and with bacteriophage Red recombination. J Bacteriol 1999; 181:1352-5; PMID:9973367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy KC, Lewis LJ. Properties of Escherichia coli expressing bacteriophage P22 Abc (anti-RecBCD) proteins, including inhibition of Chi activity. J Bacteriol 1993; 175:1756-66; PMID:8383665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong Y, Pan Y, Harman NJ, Ebner PD. Escherichia phage vB_EcoS_FFH1, complete genome. Complete genome sequences of two escherichia coli O157:H7 phages effective in limiting contamination of food products. Genome Announc 2014; 2(5); http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/genomeA.00519-14; Accession number KJ190157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim M, Ryu S. Characterization of a T5-like coliphage, SPC35, and differential development of resistance to SPC35 in salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011; 77, 2042-50; PMID:21257810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Happonen L, Butcher S, Mattinen L, Nawaz A, Skurnik M. Yersinia phage phiR201 complete genome. Unpublished 2012; NCBI Accession number HE956708.1 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niu YD, Stanford K, Kropinski AM, Ackermann HW, Johnson RP, She YM, Ahmed R, Villegas A, McAllister TA. Escherichia phage bV_EcoS_AKFV33, complete genome. Genomic, proteomic and physiological characterization of a T5-like bacteriophage for control of shiga toxin-poducing escherichia coli O157:H7. PLoS One 2012; 7(4):E34585; PMID:22514640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0034585 Accession number HQ665011.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piya D, Xie Y, Hernandez AC, Everett GFK. Complete genome of salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium siphophage shivani. Genome Announc 2015; 3(1); PMID:25720685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/genomeA.01443-14; Accession number KP143763.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golomidova AK, Kulikov EE, Letarov AV, Prokhorov NS. Enterobacteria phage DT57C, complete genome. Host range determinants in two T5-related coliphages isolated from horse feces. Unpublished 2014; NCBI Accession number KM979354.1 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golomidova AK, Kulikov EE, Letarov AV, Prokhorov NS. Enterobacteria phage DT571/2, complete genome. Host range determinants in two T5-related coliphages isolated from horse feces. Unpublished 2014; NCBI Accession number KM979355 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grover JM, Luna AJ, Wood TL, Chamakura KR, Kuty Everett GF. Complete genome of salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium T5-like siphophage stitch. Genome Announc 2015; 3(1); PMID:25657270; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/genomeA.01435-14; NCBI Accession number KM236244.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee DH, Lee JH, Shin H, Ji S, Roh E, Jung K, Ryu S, Choi J, Heu S. Complete genome sequence of pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum bacteriophage My1. J Virol 2012; 86(20):11410-1 PMID:22997426; NCBI Accession number JX195166.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edgell DR, Gibb EA, Belfort M. Mobile DNA elements in T4 and related phages. Virol J 2010; 7:290; PMID:21029434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. The Galaxy Team. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol 2010; 11(8):R86; PMID:20738864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blankenberg D, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, Ananda G, Lazarus R, Mangan M, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. “Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists”. Curr Proto Mol Biol 2010; Chapter 19:Unit 19.10.1-21; PMID:20069535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/0471142727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giardine B, Riemer C, Hardison RC, Burhans R, Elnitski L, Shah P, Zhang Y, Blankenberg D, Albert I, Taylor J, et al. “Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis”. Gen Res 2005; 15(10):1451-5; PMID:16169926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rhoades M. Interruption-deficient mutants of bacteriophage T5: analysis of single-site mutants. J Virol 1986; 59:203-9; PMID:3016291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rogers SG, Hamlett NV, Rhoades M. Interruption-deficient mutants of bacteriophage T5. II. Properties of a mutant lacking a specific interruption. J Virol 1979; 29:726-34; PMID:430607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ponchon L, Boulanger P, Labesse G, Letellier L. The endonuclease domain of bacteriophage terminases belongs to the resolvase/integrase/ribonuclease H superfamily. A bioinformatics analysis validated by a functional study on bacteriophage T5. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:5829-36; PMID:16377618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zivanovic Y, Confalonieri F, Ponchon L, Lurz R, Chami M, Flayhan A, Renouard M, Huet A, Decottignies P, Davidson AR, et al.. Insights into bacteriophage T5 structure from analysis of its morphogenesis genes and protein components. J Virol 2014; 88(2):1162-74; PMID:24198424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Everett RD. DNA replication of bacteriophage T5. 3. Studies on the structure of concatemeric T5 DNA. J Gen Virol 1981; 52:25-38; PMID:7264606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]