Abstract

Background. Prospective studies in various cardiovascular populations show that Type D personality predicted impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and disease-specific health status. We examined the effect of negative affectivity (NA), social inhibition (SI) and their combined effect (Type D personality) on HRQoL and disease-specific health status among colorectal cancer (CRC) patients.

Methods. CRC patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2009, as registered in the Dutch population-based Eindhoven Cancer Registry, received questionnaires on Type D personality (DS14), HRQoL (EORTC QLQ-C30) and disease-specific health status (EORTC QLQ-CR38) in 2010, 2011 and 2012.

Results. Response rates were 73% (n = 2625), 83% (n = 1643) and 82% (n = 1458), respectively. Analyses were done on those completing at least two questionnaires (n = 1735). Individuals with Type D (NA+/SI+; 19%) and high NA (NA+/SI-; 11%) reported a significantly worse HRQoL and disease-specific health status compared to NA-/SI+ and NA-/SI-. Differences were stable over time. Linear mixed effects models showed that Type Ds had a lower quality of life, cognitive and emotional functioning, more insomnia, diarrhea, gastrointestinal, defecation and stoma-related problems and poor body image and future perspective compared to the reference group (NA-/SI-), even after controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables. High NA individuals (NA+/SI-) reported similar poor health outcomes as Type Ds. However, they also reported lower social functioning and more fatigue, pain, micturition- and financial problems, while Type Ds reported more constipation, sexual problems and less sexual enjoyment.

Conclusions. Type D personality and high NA both have a significant negative stable impact on HRQoL and disease-specific health status among CRC patients.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most prevalent cancer in the Netherlands. There were about 45 000 CRC survivors in 2000, while in 2020 the total number is expected to have doubled [1]. Most research among CRC survivors focusses on the role of clinical variables, like diagnosis and treatment, on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and disease-specific health status (e.g. side effects and symptoms). However, the role of individual differences in this matter is under exposed. The holy grail of personalized medicine, which is currently the dominant ambition of translational research, will remain elusive unless we can find ways to identify those patients that experience a healthy cancer survivorship, and those patients who do not. In addition to clinical and demographic characteristics, individual differences in personality can probably help to identify those patients [2].

Type D personality has been shown to be an important predictor of HRQoL and disease-specific health status in medical and general populations, above and beyond clinical characteristics [3–5]. Type D is defined by the combination of two personality traits; the tendency to experience negative emotions [negative affectivity (NA)] and to inhibit self-expression in social interaction [social inhibition (SI)] [6]. As such, Type D has been associated with adverse health outcomes, impaired health status and HRQoL, more serious illness perceptions and an increased health care utilization [2,4,5,7,8]. Overall, the NA component of Type D plays a more important role than the SI component in terms of general HRQoL, while the specific combination of NA and SI in Type D has been related to symptoms of anhedonia, mental fatigue and decreased motivation [9]. There are a number of potential pathways that could explain the relationship between personality and worse self-reported health and HRQoL. For example, patients with Type D and high NA may be more likely to perceive and attend to somatic symptoms and to interpret them as potentially pathological [8]. In addition, Type D personality has been associated with an unhealthy lifestyle and poor treatment adherence, which, in turn, may have an adverse effect on perceived health [8].

Research on the association of personality and HRQoL among CRC cancer patients is scarce but rising. A recent cross-sectional study among 162 CRC patients reported that personality was associated with HRQoL, independent of disease severity and psychological distress [10]. Furthermore, a prospective study among 144 CRC patients stated that personality variables can predict a decrease in HRQoL over a one-year period [11]. Also, Type D personality was associated with poor quality of life and mental health among CRC and other cancer survivors in a cross-sectional population-based study (n = 3080) [7].

A recent review stated that “more well-designed prospective investigations are necessary to establish the contributory role of personality dimensions for the development of and protection from distress and impairment in the HRQoL of CRC patients” [8]. In order to predict which CRC patients will experience a self-reported healthy cancer survivorship, we will investigate the degree to which HRQoL and disease-specific health status can be explained by individual differences in the personality (e.g. NA, SI and Type D personality), while controlling for clinical characteristics.

Methods

Setting and participants

Data from the first three waves (2010, 2011 and 2012) of a prospective population-based yearly survey among CRC survivors from the Eindhoven Cancer Registry (ECR) was used. The ECR compiles data of all individuals newly diagnosed with cancer in the southern part of the Netherlands, an area with 10 hospitals serving 2.3 million inhabitants [12]. Everyone diagnosed with CRC from 2000 to 2009 as registered in the ECR was eligible for participation. Those with unverifiable addresses, with cognitive impairment, who died prior to the start of study or were terminally ill, with stage 0/carcinoma in situ, and those already included in our 2009 study or another study (n = 169) were excluded. A complete overview of the selection of patients can be found on our website http://www.profilesregistry.nl/dataarchive/study_units/view/22 under ‘data & documentation’. This study was approved by the certified Medical Ethics Committee of the Maxima Medical Centre, Veldhoven, The Netherlands.

Data collection was done within PROFILES [13]. Data from the PROFILES registry is freely available for non-commercial scientific research, subject to study question, privacy and confidentiality restrictions, and registration (www.profilesregistry.nl).

Data collection

Survivors were informed of the study via a letter from their (ex-)attending specialist. The letter included a link to a secure website, a login name, and a password, so that interested patients could provide informed consent and complete questionnaires online. If the patient preferred written rather than digital communication, (s)he could return our postcard by mail after which (s)he received our paper-and-pencil informed consent form and questionnaire. Non-respondents were sent a reminder letter and paper-and-pencil questionnaire within two months.

Survivors’ sociodemographic and clinical information were available from the ECR. Comorbidity at the time of the study was assessed with the adapted Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire [14]. Questions on marital status, educational level, and current occupation were included in the questionnaire.

NA, SI and Type D personality

NA, SI, and the Type D personality construct were assessed with the Type D Personality Scale (DS14) [6]. The 14 items are answered on a five-point response scale ranging from 0 (false) to 4 (true). The DS14 has good measurement properties; the subscales have high reliability (Cronbach's alpha 0.88/0.86) and good test-retest reliability over a three-month period of r = 0.72/0.82 for the two subscales, respectively, and the DS14 discriminates well between Type D and non-Type personality [6,15]. To compare the separate and combined effects of high and low trait levels, the standard cut-off score ≥ 10 on the NA and SI subscales of the DS14 [6] was used to classify patients in four personality groups based on their scores at T1: NA ≥ 10 and SI ≥ 10 (NA+/SI+; the ‘Type D’ group), NA ≥ 10 but SI ≤ 9 (NA+/SI-; the ‘NA only’ group), SI ≥ 10 but NA ≤ 9 (NA-/SI+; the ‘SI only’ group), and both NA ≤ 9 and SI ≤ 9 (NA-/SI-; the ‘reference’ group).

Quality of life

The EORTC QLQ-C30 (Version 3.0) was used to assess cancer-specific QoL [16]. It contains five functional scales, a global health status/QoL scale, three symptoms scales, and six single items. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert-scale, except the global QoL scale, which has a seven-point Likert-scale. Scores were linear transformed to a 0–100 scale [17]. A higher score on the functional scales and global QoL scale means better functioning and QoL. A higher score on the symptom scales mean more complaints.

Disease-specific health status

Disease-specific health status was assessed with the EORTC QLQ-CR38 [18]. It consists of two multi-item and two single-item scales, seven symptom scales, and an item on weight loss. Items were scored on a four-point Likert-scale. All scales were linearly converted to a 0–100 scale. A higher score on the EORTC QLQ-CR38 functional scales and single items (i.e. body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective) represent a higher level of function. For the symptom scales and single items, a higher score represents a higher level of symptoms.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) comprising of seven items on a four-point Likert-scale [19]. It assesses levels of symptoms in the last week. The scale mainly covers anhedonia and loss of interest, which are core depressive symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between respondents, non-respondents or patients with unverifiable addresses at T1 and between patients who completed one or more questionnaires were compared with a χ2, ANOVA or independent samples t-test where appropriate.

All other analyses are based on patients who completed at least two questionnaires. Differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between patients with different personality types (NA-/SI-; NA-/SI+; NA+/SI-; Type D) were compared with a χ2 or ANOVA while differences in HRQoL and disease-specific health status were determined by ANOVAs at each time point. As our results showed that NA had a large effect on our outcomes, the same analyses were performed for continuous NA scores divided into quartiles.

The course of HRQoL and disease-specific health status (separate models for each scale) according to the four personality groups was analyzed using linear mixed effects models (i.e. covariance pattern model with an unstructured error variance matrix and maximum likelihood estimation). This technique uses data efficiently by also including incomplete cases in the analyses. As a result of this, bias is limited and statistical power is preserved. Time was analyzed as a regular categorical predictor with three levels (i.e. three time points). Sex, age, time since diagnosis, treatment, disease stage, comorbid conditions, partnership and educational level and depression levels were entered as covariates into the models, based on a priori assumptions/hypotheses. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed as time-invariant predictors (i.e. baseline characteristics were used). Depression scores were analyzed as continuous time varying predictors. In order to correctly interpret all model parameters, all continuous variables have been grand-mean centered.

Finally, a sub analyses using linear mixed-effects models was performed on the general subscale global health status/QoL over time stratified by NA divided into quartiles.

All statistical tests were two-sided and considered significant if p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA). Missing items from multi-item scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 were mean-imputed if at least half of the items from the scale were answered, according to the EORTC guideline. Missing items on the DS14 and HADS scales were mean imputed if only one item was missing, otherwise the scale score became missing [6,19].

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The questionnaire was completed by 73% (n = 2625) at T1, 83% (n = 1643) at T2 and 82% (n = 1458) at T3. Respondents were significantly younger (69.4 vs. 72.4; p < 0.01), more often male (55% vs. 48%; p < 0.01), were more often diagnosed with stage I disease (30% vs. 25%; p = 0.02) and were more often treated with radiotherapy (31% vs. 24%; p < 0.01) compared to non-respondents. Respondents significantly more often received radiotherapy (31% vs. 26%; p < 0.01) and surgery (99% vs.96%; p = 0.01) and were more often male (55% vs. 48%; p < 0.01) compared to patients with unverifiable addresses.

Those who completed one versus those who completed ≥ 2 questionnaires differed with respect to gender (49% vs. 43% female; p < 0.01), age (71.3 vs. 68.4 years; p < 0.001), having a partner (71% vs. 79%; p < 0.001), having a job (10% vs. 19%; p < 0.01), and radiotherapy treatment (27% vs. 32%; p < 0.01). Also, they more often had a lower educational level (p < 0.001), were more often diagnosed with stage IV disease (p < 0.001) and had worse scores on more than half of the subscales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 (global QoL, physical, role emotional and social functioning, fatigue, nausea, pain, dyspnea, appetite loss, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, future perspective, chemotherapy side effects and weight loss; data not shown). Those who completed ≥ 2 questionnaires had worse scores on the subscales gastrointestinal problems and defecation problems. From this point forward, only those who completed ≥ 2 questionnaires are described in the analyses.

At T1, 328 CRC survivors (19%) had a Type D personality (Table I). No statistically significant differences were observed between those with and without a Type D personality in age, years since diagnosis, primary treatment and tumor type. However, CRC survivors with a Type D personality were significantly more often female, more often diagnosed with stage II disease, had a lower educational level and had a partner less often compared to those without a Type D personality. Furthermore, those with NA only were younger compared to the other three groups. Finally, those with Type D and those with NA only had more comorbid conditions compared to the other two groups.

Table I.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at T1 according to Type D personality.

| N (%) | All (n = 1735) | NA-/SI- (n = 911) | NA-/SI+ (n = 297) | NA+/SI- (n = 199) |

NA+/SI+ (n = 328) |

p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Female) | 743 (43%) | 383 (42%) | 110 (37%) | 92 (46%) | 158 (48%) | 0.03 |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 68.4 (9.4) | 68.8 (9.1) | 68.4 (9.2) | 66.6 (10.5) | 68.5 (9.8) | 0.03 |

| Years since diagnosis [mean (SD)] | 5.1 (2.8) | 5.1 (2.9) | 5.4 (2.8) | 5.1 (2.7) | 5.0 (2.7) | 0.21 |

| Tumor type Colon Rectal |

1031 (59%) 704 (41%) |

558 (61%) 353 (34%) |

171 (58%) 126 (42%) |

112 (56%) 87 (44%) |

190 (58%) 138 (42%) |

0.42 |

| Stage I II III IV |

522 (31%) 610 (36%) 503 (30%) 55 (3%) |

267 (30%) 327 (37%) 264 (30%) 30 (3%) |

100 (35%) 93 (32%) 91 (32%) 5 (2%) |

63 (32%) 59 (30%) 60 (31%) 13 (7%) |

92 (29%) 131 (42%) 88 (28%) 7 (2%) |

0.03 |

| Chemotherapy (yes) | 516 (30%) | 265 (29%) | 88 (30%) | 67 (34%) | 96 (29%) | 0.64 |

| Radiotherapy (yes) | 562 (32%) | 277 (30%) | 107 (36%) | 68 (36%) | 110 (34%) | 0.27 |

| Number of comorbid conditions None One Two or more |

422 (25%) 501 (30%) 736 (44%) |

239 (28%) 273 (32%) 353 (41%) |

95 (33%) 92 (32%) 99 (35%) |

33 (17%) 51 (27%) 108 (56%) |

55 (17%) 85 (27%) 176 (56%) |

< 0.001 |

| Partner (yes) | 1357 (79%) | 706 (78%) | 247 (84%) | 158 (81%) | 246 (75%) | 0.05 |

| Educational level Low Middle High |

285 (17%) 1055 (61%) 383 (22%) |

138 (15%) 560 (62%) 206 (23%) |

48 (16%) 169 (57%) 79 (27%) |

29 (15%) 123 (63%) 44 (22%) |

70 (21%) 203 (62%) 54 (17%) |

0.02 |

| Quality of life [mean (SD)] Global quality of life Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Fatigue Nausea Pain Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhea Financial problems |

78.9 (17.7) 82.3 (19.0) 82.0 (26.0) 86.8 (18.6) 85.3 (20.3) 87.1 (21.6) 20.1 (22.1) 3.2 (10.5) 15.6 (23.8) 12.6 (23.3) 20.3 (27.8) 4.2 (13.5) 8.6 (19.2) 10.6 (21.5) 7.0 (19.1) |

83.3 (15.4) 84.7 (17.7) 85.9 (23.8) 94.0 (10.4) 90.1 (15.3) 91.3 (18.1) 15.6 (19.6) 2.3 (9.4) 12.5 (21.8) 9.9 (20.8) 15.9 (24.8) 2.5 (10.4) 6.7 (16.8) 8.5 (19.2) 5.3 (16.9) |

82.0 (15.4) 84.7 (17.4) 85.3 (23.0) 91.6 (13.1) 87.7 (17.6) 90.9 (16.7) 16.0 (18.7) 2.5 (8.9) 12.8 (20.6) 10.5 (21.1) 15.8 (24.0) 3.3 (13.5) 8.7 (18.7) 9.6 (19.9) 4.1 (15.0) |

70.5 (19.0)b 77.0 (20.7)b 73.4 (29.0)b 71.9 (22.3)b 75.6 (25.9)b 79.0 (24.2)b 31.2 (25.0)b 5.7 (14.1)b 22.1 (27.1)b 19.5 (27.7)b 32.8 (34.1)b 8.0 (19.0)b 11.2 (22.7) 13.8 (24.6)b 12.2 (23.9)b |

69.1 (19.3)b 77.0 (21.1)b 73.3 (29.2)b 71.3 (23.3)b 75.6 (25.1)b 77.0 (27.4)b 29.9 (24.4)b 4.7 (11.8) 22.7 (27.3)b 18.1 (26.9)b 29.3 (30.6)b 7.3 (16.1)b 11.7 (22.8)b 15.4 (25.5)b 11.4 (23.4)b |

< 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 |

| EORTC QLQ-CR38 [mean (SD)] Body image Future perspectives Sexual functioning Sexual enjoyment Micturition problems Chemotherapy side effects Gastrointestinal problems Male sexual problemsc Female sexual problemsc Defecation problems Stoma-related problems Weight loss |

84.7 (21.7) 72.8 (27.1) 24.4 (23.1) 58.7 (27.7) 21.4 (17.5) 10.4 (15.5) 15.4 (14.5) 43.4 (37.6) 23.6 (24.8) 13.2 (12.6) 23.5 (21.2) 4.5 (14.1) |

89.0 (18.0) 79.5 (23.3) 26.0 (23.8) 61.9 (26.8) 19.6 (17.0) 8.3 (13.2) 12.6 (12.6) 40.2 (37.4) 22.6 (25.8) 11.5 (11.3) 20.2 (19.7) 3.6 (12.3) |

86.9 (19.3) 77.6 (23.5) 23.8 (21.7) 56.4 (26.4) 20.2 (17.1) 8.1 (12.5) 15.4 (13.8) 44.7 (36.4) 20.3 (20.5) 12.6 (11.9) 18.0 (17.8) 4.2 (13.5) |

75.5 (27.3) 58.2 (30.9) 23.5 (22.7) 59.4 (29.7) 26.0 (18.5) 14.0 (17.3) 22.1 (15.8) 45.9 (40.3) 27.3 (26.3) 16.7 (13.1) 30.9 (20.5) 7.0 (17.3) |

76.0 (24.8) 58.8 (28.8) 21.0 (22.4) 50.8 (28.7) 24.6 (17.8) 15.9 (20.1) 19.4 (16.9) 49.9 (37.4) 27.5 (24.3) 16.9 (15.1) 32.9 (24.4) 5.9 (16.5) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 0.02 < 0.01 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 0.04 0.51 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.01 |

| HADS [mean (SD)] Anxiety Depression |

4.5 (3.7) 4.0 (3.4) |

2.9 (2.6) 2.7 (2.4) |

3.4 (2.6) 3.2 (2.7) |

7.4 (3.7) 5.8 (3.5) |

7.8 (3.8) 7.0 (4.0) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 |

Only those who completed two or more questionnaires were included in the analyses.

A higher score on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 functional scales, global QOL scale and single items (i.e. body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspective) represent a higher level of function. For the symptom scales and single items, a higher score represents a higher level of symptoms.

ap-Value represents the difference between the four personality groups; bClinically relevant differences between the Type D group (NA+ SI+) and the reference group (NA-SI-) and between the NA only group (NA+ SI-) and the reference group (NA-SI-) according the guidelines [20]; cthis question was filled out by a small number of patients.

HRQoL and disease-specific health status

At T1, patients with Type D and NA only reported a significantly worse HRQoL and more disease- specific symptoms compared to the other two groups except for sexual enjoyment which was only worse among those with a Type D personality, and female sexual problems which showed no differences between the groups (Table I). Furthermore, the differences in HRQoL scores between the Type D group and the reference group, and between the NA only group and the reference group, were clinically relevant for all subscales except for nausea (Type D group) and constipation (NA only group) [20].

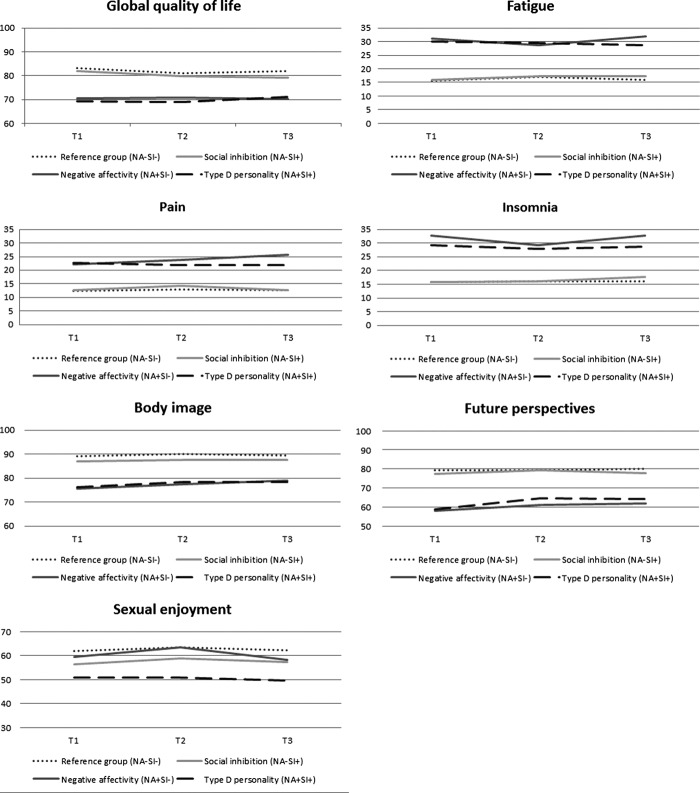

These differences in HRQoL and disease-specific health status between Type D and NA only groups versus the SI only and reference groups were quite stable across the three time points, the most relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 subscales with respect to survivorship [21] are presented in Figure 1. However, problems with weight loss and female sexual functioning were more prevalent in the Type D group than in the other three groups at T2, and Type D patients also reported more problems regarding sexual enjoyment across all time points. Type D patients also reported more problems with sexual functioning and male sexual functioning at T1, but not at T2 or T3 and for female sexual functioning at T2 but not T1 or T3 than patients with NA only.

Figure 1.

The most relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 subscales regarding survivorship over time stratified by personality. Only those who completed two or more questionnaires were included in the analyses. A selection of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 subscales that are most relevant with respect to survivorship are included in this figure [21].

Linear mixed effects models showed that CRC survivors with a Type D personality were at a significantly increased risk of an impaired global quality of life, more insomnia, less sexual enjoyment, and a worse body image and future perspective compared to the reference group (NA-/SI-), even after controlling for sex, age, time since diagnosis, stage, chemotherapy, comorbidity, partner, education, time of questionnaire, and depression (Table II). Also, CRC survivors with a Type D personality were at a significantly increased risk of an impaired cognitive functioning (Beta -4.7, 95% CI -6.7–-2.6), emotional functioning (Beta -10.3, 95% CI-11.8–-8.7), more diarrhea (Beta 3.6, 95% CI 1.2–6.1), constipation (Beta 2.3, 95% CI 0.1–4.5), gastrointestinal problems (Beta 3.2, 95% CI 1.6–4.8), defecation problems (Beta 3.6, 95% CI 2.0–5.2), stoma-related problems (Beta 8.9, 95% CI 3.8–14.0), and female sexual problems (Beta 14.8, 95% CI 5.5–24.0) in comparison to the reference group. Other important determinants of HRQoL and disease-specific symptoms were sex, age, time since diagnosis, comorbid conditions and depression (data not shown).

Table II.

Generalized linear mixed model estimating effects of Type D personality on the most relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 subscales regarding survivorship over time, mutually adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | EORTC-QLQ-CR38 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global quality of life Beta and 95% CI |

Fatigue Beta and 95% CI |

Pain Beta and 95% CI |

Insomnia Beta and 95% CI |

Body image Beta and 95% CI |

Future perspective Beta and 95% CI |

Sexual enjoyment Beta and 95% CI |

||||||||

| Sex Female vs. male |

2.0 | 0.8–3.1** | − 3.9 | − 5.5–− 2.3** | − 4.9 | − 6.7–− 3.1** | − 10.7 | − 12.9–− 8.6** | 0.6 | − 1.2–2.3 | 3.7 | 1.8–5.7** | 11.8 | 8.3–15.2** |

| Agea | 0.1 | 0.1–0.2** | − 0.1 | − 0.2–0.01* | − 0.2 | − 0.3–− 0.1** | − 0.1 | − 0.2–− 0.1* | 0.3 | 0.2–0.3** | 0.3 | 0.2–0.4** | − 0.4 | − 0.6–− 0.2** |

| Time since diagnosisa |

0.3 | 0.1–0.5** | − 0.5 | − 0.7–− 0.2** | − 0.3 | − 0.6–0.1 | − 0.4 | − 0.8–− 0.1* | 0.6 | 0.3–0.9** | 1.0 | 0.6–1.3** | 0.1 | − 0.4–0.7 |

| Stage Stage I vs. IV Stage II vs. IV Stage III vs. IV |

− 0.4 − 0.5 0.8 |

− 3.9–3.1 − 4.0–2.9 − 2.6–4.1 |

− 3.9 − 3.6 − 4.4 |

− 8.6–0.8 − 8.2–1.0 − 8.8–0.1 |

− 2.1 − 1.4 − 0.9 |

− 7.3–3.0 − 6.5–3.7 − 5.8–4.0 |

2.2 0.9 2.2 |

− 4.3–8.6 − 5.4–7.2 − 3.9–8.3 |

− 4.8 − 3.9 − 3.2 |

− 9.9–0.4 − 8.9–1.2 − 8.0–1.7 |

12.3 10.7 9.6 |

6.6–18.0** 5.0–16.3** 4.2–15.1** |

− 4.1 − 2.4 − 4.0 |

− 13.5–5.4 − 11.6–6.9 − 12.9–4.9 |

| Chemotherapy yes vs. no |

1.1 | − 0.6–2.7 | − 1.2 | − 3.4–1.0 | 0.9 | − 1.5–3.3 | 0.1 | − 2.9–3.1 | 1.7 | − 0.8–4.0 | 0.3 | − 2.4–3.0 | − 0.6 | − 5.0–3.8 |

| Comorbid conditionsa | − 2.3 | − 2.7–− 2.0** | 2.6 | 2.2–3.0** | 4.0 | 3.5–4.5** | 1.9 | 1.3–2.5** | − 0.6 | − 1.1–− 0.2** | − 1.8 | − 2.4–− 1.3** | 0.1 | − 0.8–1.0 |

| Partner no vs. yes |

0.6 | − 0.7–2.0 | − 1.8 | − 3.6–− 0.1* | − 2.7 | − 4.7–− 0.6* | − 4.6 | − 7.1–− 2.2** | − 0.7 | − 2.7–1.3 | 0.8 | − 1.4–3.1 | 1.6 | − 2.8–6.0 |

| Education High vs. Middle High vs. Low |

0.2 0.1 |

− 1.1–1.5 − 1.7–1.9 |

0.1 − 1.1 |

− 1.7–1.7 − 3.4–1.3 |

0.6 1.1 |

− 1.4–2.5 − 1.5–3.8 |

0.6 − 0.1 |

− 1.8–2.9 − 3.2–3.2 |

1.0 2.3 |

− 0.8–2.8 − 0.1–4.9 |

0.8 1.6 |

− 1.3–3.0 − 1.3–4.6 |

− 0.1 − 3.7 |

− 3.4–3.3 − 8.8–1.5 |

| Time T2 vs. T1 T3 vs. T1 |

− 1.1 − 1.3 |

− 1.9–− 0.3** − 2.2–− 0.4** |

0.2 0.8 |

− 0.8–1.1 − 0.3– 1.8 |

0.7 0.7 |

− 0.5–1.8 − 0.6–1.9 |

− 0.5 0.7 |

− 1.8–0.7 − 0.7–2.2 |

1.1 0.4 |

0.1–2.1* − 0.7–1.5 |

1.5 0.6 |

0.2–2.7* − 0.8–2.0 |

0.4 − 1.1 |

− 1.8–2.5 − 2.5–2.3 |

| Depressiona | − 2.2 | − 2.4–− 2.1** | 2.5 | 2.3–2.7** | 1.7 | 1.5–1.9** | 1.6 | 1.3–1.9** | − 1.8 | − 2.0–− 1.6** | − 2.2 | − 2.5–2.0** | − 1.5 | − 2.0–− 1.1** |

| Type D NA-/SI+ vs. NA-/SI- NA+/SI- vs. NA-/SI- NA+/SI+ vs. NA-/SI- |

− 0.7 − 3.5 − 2.3 |

− 2.3–0.8 − 5.5–− 1.6** − 3.9–− 0.6** |

0.2 5.1 1.8 |

− 1.9–2.3 2.5–7.7** − 0.4–4.0 |

0.4 3.3 0.1 |

− 1.9–2.7 0.5–6.2* − 2.3–2.6 |

0.1 8.0 4.3 |

− 2.8–3.0 4.5–11.6** 1.3–7.3** |

− 1.0 − 6.2 − 4.9 |

− 3.3–1.3 − 9.0–− 3.3** − 7.3–− 2.5** |

− 0.5 − 11.1 − 7.5 |

− 3.1–2.1 − 14.2–− 7.9** − 10.2–− 4.8** |

− 4.7 3.9 − 6.4 |

− 9.0–− 0.5* − 1.5–9.2 − 10.9–− 2.0** |

Only those who completed two or more questionnaires were included in the analyses.

A selection of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CR38 subscales that are most relevant with respect to survivorship are included in this figure [21].

aContinuous variables are grand-mean centered; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Furthermore, linear mixed effects models showed that patients with NA only also reported an impaired global quality of life, more insomnia, a worse body image, and future perspective compared to the reference group but moreover, they also reported and more fatigue and pain (Table II). Additionally, those who score high on NA reported more problems with cognitive functioning (Beta –5.4, 95% CI –7.8––2.9), social functioning (Beta –2.7, 95% CI –5.1––0.3), emotional functioning (Beta –12.6, 95% CI –14.4––10.7), and more diarrhea (Beta 3.7, 95% CI 0.8–6.6), gastrointestinal problems (Beta 4.4, 95% CI 2.5–6.5), defecation problems (Beta 2.9, 95% CI 1.0–4.8), stoma-related problems (Beta 8.6, 95% CI 2.7–14.5), micturition problems (Beta 3.1, 95% CI 0.8–5.4) and financial problems (Beta 3.2, 95% CI 0.7–5.6).

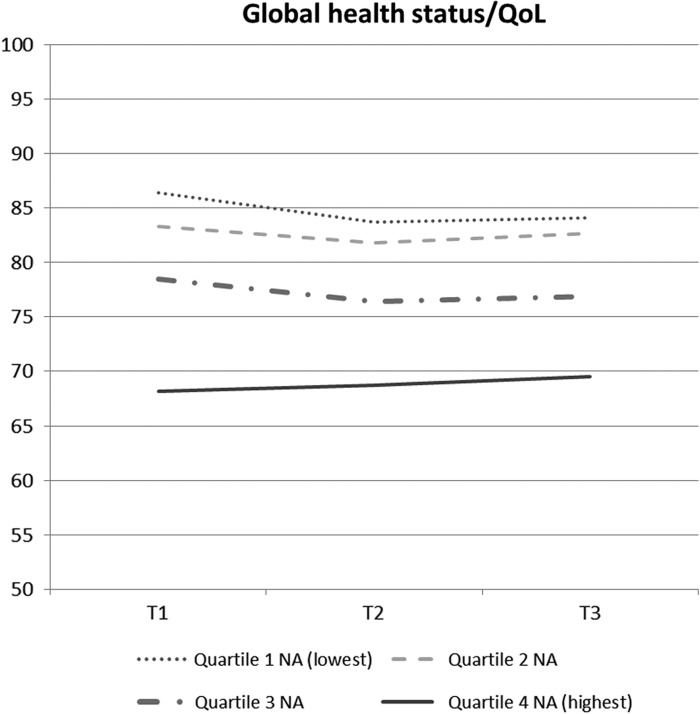

As patients with Type D and NA only reported very similar scores on most outcomes, we performed a sub analysis on the general and overarching “global health status/QoL” scale over time stratified by NA divided into quartiles (Figure 2). Results showed that all NA quartiles differed significantly from each other at each time point with respect to Global health status/QoL, except for quartile 1 (lowest) and 2 which did not differ.

Figure 2.

Global health status/QoL over time stratified by negative affectivity. Only those who completed two or more questionnaires were included in the analyses.

Discussion

CRC survivors with a Type D personality and those with high NA reported a significantly worse HRQoL and disease-specific health status and these differences were quite stable over time. Furthermore, linear mixed effects models showed that Type D patients had a lower quality of life, cognitive and emotional functioning, and sexual enjoyment, and they reported more insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, gastrointestinal-, defecation-, stoma-related-, and female sexual problems, and a worse body image and future perspective compared to the reference group, even after controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables. High NA patients reported similar poor outcomes as Type Ds. However, they also reported a lower social functioning and more fatigue, pain, micturition- and financial problems, while Type D individuals reported more sexual problems and less sexual enjoyment.

To our knowledge, other studies that prospectively describe the influence of Type D personality and its components on HRQoL and disease-specific health status among cancer patients are lacking. However, a prospective study among 144 CRC patients showed that personality variables can predict a decrease in HRQoL over a one-year period [11]. Furthermore, our results confirm those of a cross-sectional study on Type D personality among 124 Taiwanese CRC survivors that also reported that Type D personality was an important factor associated with QoL [22]. Finally, prospective studies among cardiovascular patients also showed that Type D personality has a negative influence on HRQoL and disease-specific health status [23–26].

Importantly, our study showed that the NA component of Type D was more prominent than SI in predicting worse patient-reported outcomes. This suggests that NA should be the primary focus when evaluating personality-related differences in patient-reported outcomes. Other studies also suggested that the NA component of Type D is the key predictor of subjective health outcomes in both healthy [27] and cardiac populations [28]. The specific combination of NA and SI in the Type D construct may be more important regarding the risk of adverse cardiac events. A recent study in 541 patients with coronary artery disease showed that Type D personality was associated with cardiac death and myocardial infarction, while patients with high NA or SI alone were not at an increased risk [29].

The present study has some limitations. Although we had sociodemographic and clinical information of non-respondents, it remains unknown whether they declined to participate because of poor health. Furthermore, personality traits like neuroticism or a low sense of coherence are also known to exert influence on HRQoL and we did not take them into account. Finally, although Type D personality is a stable construct [30], and although this is a prospective study, our analyses limit the determination of causal association between personality and patient-reported outcomes as baseline data on these outcomes are unknown. The strengths of this study are that we assessed HRQoL and disease-specific health status prospectively in a large population-based setting which provides information on the persistence of these constructs over time in a representative group of CRC patients in daily practice.

Type D personality and high NA were associated with poor HRQoL and disease-specific health status among survivors of CRC, even after controlling for sociodemographic and clinical variables. By taking a patient's personality into account, this study offers a different view on personalized medicine. Evaluating HRQoL and disease-specific health status according to personality is of great value as this informs about the disease burden and treatment-related effects directly from the patients’ perspective. This information will help clinicians to inform CRC patients about potential late side effects. Furthermore, this can possibly lead to the development and evaluation of strategies for tailored long-term management and support for survivors on the basis of a more individualized approach, as a function of stable differences in coping with chronic medical conditions. For example, mindfulness-based stress reduction may reduce levels of negative affectivity and social inhibition [31]. Paying attention to the recognition of NA seems warranted as these patients reported a worse HRQoL and disease-specific health status.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all patients and their doctors for their participation in the study. Special thanks go to Dr. M. van Bommel, who was willing to function as an independent advisor and to answer questions of patients. In addition, we want to thank the following hospitals for their cooperation: Amphia Hospital, Breda; Bernhoven Hospital, Veghel and Oss; Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven; Elkerliek Hospital, Helmond; Jeroen Bosch Hospital, ‘s Hertogenbosch; Maxima Medical Centre, Eindhoven and Veldhoven; Sint Anna Hospital, Geldrop; St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg; Twee Steden Hospital, Tilburg and Waalwijk; VieCury Hospital, Venlo and Venray. The present research was supported by a VENI grant (#451-10-041) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (The Hague, The Netherlands) awarded to Floortje Mols.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Signaleringscommissie_kanker Kanker in Nederland tot 2020; trends en prognoses [Cancer in the Netherlands till 2020; trends and prognoses] 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Thong MS, van de Poll-Franse LV, Roukema JA, Denollet J. Type D (distressed) personality is associated with poor quality of life and mental health among 3080 cancer survivors. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denollet J, Schiffer AA, Spek V. A general propensity to psychological distress affects cardiovascular outcomes: Evidence from research on the type D (distressed) personality profile. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:546–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.934406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Denollet J. Type D personality among noncardiovascular patient populations: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Denollet J. Type D personality in the general population: A systematic review of health status, mechanisms of disease, and work-related problems. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denollet J. DS14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:89–97. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Oerlemans S, Denollet J, Roukema JA, van de Poll-Franse LV. Type D personality is associated with increased comorbidity burden and health care utilization among 3080 cancer survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:352–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales PM, Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS, Pavlidis N, Hyphantis TN. Psychosocial predictors of health outcomes in colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:800–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunevicius A, Brozaitiene J, Staniute M, Gelziniene V, Duoneliene I, Pop VJ, et al. Decreased physical effort, fatigue, and mental distress in patients with coronary artery disease: Importance of personality-related differences. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:240–7. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paika V, Almyroudi A, Tomenson B, Creed F, Kampletsas EO, Siafaka V, et al. Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients’ quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology. 2010;19:273–82. doi: 10.1002/pon.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyphantis T, Paika V, Almyroudi A, Kampletsas EO, Pavlidis N. Personality variables as predictors of early non-metastatic colorectal cancer patients’ psychological distress and health-related quality of life: A one-year prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:411–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Louwman WJ, Van de Poll-Franse LV, Coebergh JWW. Eindhoven: Eindhoven Cancer Registry; 2005. Results of 50 years cancer registry in the South of the Netherlands: 1955–2004 (in Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, van Eenbergen M, Denollet J, Roukema JA, Aaronson NK, et al. The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: Scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The self-administered comorbidity questionnaire: A new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–63. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons WH, Meijer RR, Denollet J. Negative affectivity and social inhibition in cardiovascular disease: Evaluating type-D personality and its assessment using item response theory. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayers P, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K. Group. ObotEQoL . The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: EORTC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sprangers MAG, te Velde A, Aaronson NK. The construction and testing of the EORTC Colorectal Cancer-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire Module (QLQ-CR38) Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:238–47. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM, Brown JM. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:89–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Aouizerat BE. Biomarkers: Symptoms, survivorship, and quality of life. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shun SC, Hsiao FH, Lai YH, Liang JT, Yeh KH, Huang J. Personality trait and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:E221–8. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E221-E228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquarius AE, Denollet J, de Vries J, Hamming JF. Poor health-related quality of life in patients with peripheral arterial disease: Type D personality and severity of peripheral arterial disease as independent predictors. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:507–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middel B, El Baz N, Pedersen SS, van Dijk JP, Wynia K, Reijneveld SA. Decline in health-related quality of life 6 months after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: The influence of anxiety, depression, and personality traits. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29:544–54. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182a102ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Martens EJ, Denollet J. Type D personality and depressive symptoms are independent predictors of impaired health status following acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2010;96:30–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.170357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogaro E, Schinina F, Burgisser C, Orso F, Pallante R, Aloi T, et al. Type D personality impairs quality of life, coping and short-term psychological outcome in patients attending an outpatient intensive program of cardiac rehabilitation. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2010;74:181–91. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2010.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson C, Williams L. Type D personality, quality of life and physical symptoms in the general population: A dimensional analysis. Psychol Health. 2014;29:365–73. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.856433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, O’Connor RC, Grubb NR, O’Carroll RE. Type D personality and three-month psychosocial outcomes among patients post-myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72:422–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denollet J, Pedersen SS, Vrints CJ, Conraads VM. Predictive value of social inhibition and negative affectivity for cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: The type D personality construct. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:873–81. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper N, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJ, Denollet J, Willemsen G. Nine-year stability of type D personality: Contributions of genes and environment. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:75–82. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181fdce54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyklicek I, van Beugen S, Denollet J. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on distressed (type D) personality traits: A randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2013;36:361–70. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9431-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]