Abstract

Antihypertensives that modulate the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) on AD conversion in those with MCI has not been explored. Evidence suggests that blood-brain-barrier (BBB) permeability is necessary for these effects. We assessed the impact of RAS modulation on conversion to AD and cognitive decline in those with MCI, and the impact of BBB permeability and race on these associations.

We analyzed data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center from the NIA-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. We included individuals receiving antihypertensives with MCI at baseline and who had cognitive assessments on at least 2 follow-up visits. Outcomes included conversion to AD and cognitive and functional decline.

Of 784 participants (M=75 years, 48% men), 488 were receiving RAS medications. RAS users were less likely to convert to AD (33% vs 40%; p=0.04) and demonstrated slower decline on the Clinical Dementia Rating sum-of-boxes (CDR-SOB, p<0.01) and Digit Span Forward (p=0.02) than non-RAS users. BBB-crossing RAS medications were associated with slower cognitive decline on the CDR-SOB, (p<0.01), the Mini Mental Status Examination, (p<0.01) and the Boston Naming test (p<0.01). RAS medications were somewhat associated with cognitive benefits in African Americans, more so than Caucasians. (MMSE (p=0.05) category fluency (p=0.04) and Digit Span Backwards, p=0.03)).

RAS-modulating medications were associated with less conversion to AD. BBB permeability may produce additional cognitive benefit, and African Americans may benefit moreso from RAS-modulation than Caucasians. Results highlight the need for trials investigating RAS modulation during prodromal disease stages.

Keywords: Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, Hypertension, Renin Angiotensin System, Cognition

1. Introduction

Midlife elevated blood pressure (BP) is associated with cognitive and functional decline and has been found to be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1 Similarly, research shows that reductions in BP via lifestyle intervention or medication may be associated with AD-related cognitive benefits and protection again AD.2

Research suggests that controlling BP with certain antihypertensives may reduce inflammation, improve cerebral blood flow, and degrade Aβ – the pathological hallmark of AD.3,4 While evidence supports a link between midlife antihypertensive use and later cognitive decline, there is a paucity of research focused on the clinical and mechanistic potential of these medications in individuals with established, prodromal disease stages such as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

The renin angiotensin system (RAS) regulates BP in the body and the brain, and represents a plausible mechanism linking vascular functioning and AD neuropathology. Evidence supporting the role of the RAS in AD comes from findings of increased ACE activity (a component of the RAS) in the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, frontal cortex, and caudate nucleus in AD patients. 5 Increased ACE levels have also been reported in post-mortem AD brain tissue, in direct relation to parenchymal Aβ load 6 and Braak-staged AD severity. 7

Some research shows that antihypertensives acting on the RAS, particularly those that cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), may have the potential to reduce AD risk.8,9 For instance, studies have shown that treatment with RAS acting BP medications decrease Aβ in AD animal models, 10 decrease AD incidence in non-demented humans 11 and improve cognition in AD patients, 2 more so than non-RAS medications and RAS-acting medications that do not cross the BBB. Notably, these benefits are observed irrespective of change in BP.

It is unknown whether RAS medications influence cognitive and functional ability or disease conversion during prodromal disease stages (i.e. MCI). This is of the utmost importance, because implementing targeted therapeutic interventions early in the disease process may reduce Aβ toxicity, thereby delaying the development of AD pathology. It is also unknown to what extent RAS acting antihypertensives may interact with race. It is well documented that the peripheral RAS functions differently in African Americans and Caucasians, such that African Americans have higher endogenous sodium and lower renin levels than Caucasians. Because African Americans are at high risk for AD, and it is unknown if racial differences in brain RAS function exists, it is important to address these mechanistic questions in both groups.

Our objective was to examine the extent to which BBB-crossing RAS medications are related to conversion from MCI to AD and decline in cognitive and functional ability in non-Hispanic Caucasians and African Americans over time.

2. Methods

Information was collected from the Uniform Data Set (UDS), a functional and cognitive assessment battery maintained by the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC), with 31 Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) across the US 12. Each form contains standardized administration instructions, and NACC monitors the reliability of data via range and logic checks. Written consent was obtained subjects and the study was approved by the institutional review board at each site.

2.1 Participants

Data was current as of December, 2013 and all participants had 3 or more annual visits. Five years was chosen as the maximum follow-up period because this was the largest number of visits that most participants had in common. Participants had complete annual diagnostic, cognitive and functional assessments, and medication information. Only non-Hispanic Caucasians and African Americans were included. Participants were diagnosed at baseline as having MCI based on the NIA-Alzheimer’s Association diagnostic guidelines.13

2.2 Medication Classification

Normotensive and untreated hypertensive participants (BP reading ≥ 140 mmHg systolic or ≥ 90 mmHg diastolic) were excluded. Antihypertensive medications were classified into 5 groups: ACE-inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (A2RB), beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and diuretics. ACE-I and A2RB comprised the RAS medication group. Participants were then divided into those taking RAS acting medications across all visits, and those never taking RAS medications, across all visits. Participants taking non-RAS acting antihypertensives in addition to a RAS medication were included in the RAS group, as long as RAS medication use was consistent across all visits. RAS medication users were further divided into those who were taking centrally acting RAS medications vs. non-centrally acting RAS medications.

2.3 Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was rate of progression from MCI to AD. We also evaluated performance on ten cognitive tests administered at all ADCs, which have been previously described.12 Five domains were evaluated: attention, language, memory, executive functioning, and global cognitive status. Attention was assessed according to the maximum number of correct trials for Digit Span Forward 14 and the number of seconds needed to sequence numbers using a pencil (Trail-Making Test (TMT) Part A).15 Language was examined according to the 30-item version of the Boston Naming Test. 16 Memory tests included verbal episodic memory (immediate and delayed story recall)14 and semantic memory (animals).17 Executive functioning was measured using set shifting tasks 14 and rapid alternation of numbers/letters and symbols (TMT B and Digit Symbol). 18 Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score was used to assess global cognition. 19 All analyses controlled for age, gender, race, education, BP, heart disease, diabetes and depression, at baseline.

We also evaluated longitudinal decline via the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). 20 The CDR is a well-validated instrument that has been in use for more than 20 years in clinical trials in AD and MCI. The CDR assesses three cognitive domains (memory, orientation, and judgment/problem solving), and three functional domains (community affairs, home/hobbies, personal care) using structured interviews with the subject and an informant. Scores on each domain range from 0 points (no impairment) to 3 points (severe impairment), and a total score is then generated by summing the domain scores to yield an index of the overall degree of impairment (0–18 points) (CDR-Sum of Boxes or SOB).

2.4 Analyses

We analyzed rate of progression from MCI to AD via Cox proportional hazards model (SAS PROC PHREG) to estimate the effect of RAS acting medication with adjustment for baseline age, gender, race, education, BP, heart disease, diabetes, stroke and depression. The time variable was time to conversion to AD after baseline. The principle variable of interest was RAS acting medication use vs non-RAS acting medication use over time. Hazard ratios with their 95% confidence intervals were calculated from the model. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by including interaction terms between time and predictors in the models and examining all the time dependent covariates. Same analysis method was applied to compare conversion to AD between centrally acting RAS users vs. non-centrally acting RAS users.

We also performed longitudinal analyses to evaluate the effect of RAS-acting medications on cognitive and functional decline. The main term for RAS represented cognitive performance across visits in RAS users vs. non-users, while the interaction terms between time and RAS were used to evaluate whether change over time differed between RAS users vs. non-users. All cognitive tests and the CDR-SOB were included. Cognitive scores were continuous, approximately followed normal distribution and were analyzed with linear mixed models (SAS PROC MIXED) in which a compound symmetry correlation was used to account for repeated measures on the same subject. Because the CDR-SOB is a discrete outcome with multiple categories staging dementia severity, a multinomial logistic regression model (SAS PROC GLIMMIX) was applied. Because 11 tests were included in the cognitive and functional testing battery, the threshold P-value for declaring significance using a false discovery rate approximation was adjusted such that the threshold P-value for determining statistical significance was alpha*(m + 1)/2 m, where alpha is the original conventional threshold of 0.05, and m is the number of tests. Thus, a threshold P-value of .05[(11 + 1)/(2*11)], or .027 was used. Systolic blood pressure was included both as a linear term and categorical variable in the survival analysis and the longitudinal analyses. In order to model change over time in RAS users vs non-users, we included an interaction term between time (visit) and RAS use, and we also looked at the change over time in RAS user and non-users separately. Analogously, we compared BBB crossing vs. non-BBB crossing RAS medications for cognitive and functional change over time via an interaction term and also modeling change for each group separately. In order to test for an effect of race, we conducted a 3-way interaction.

3. Results

Participants

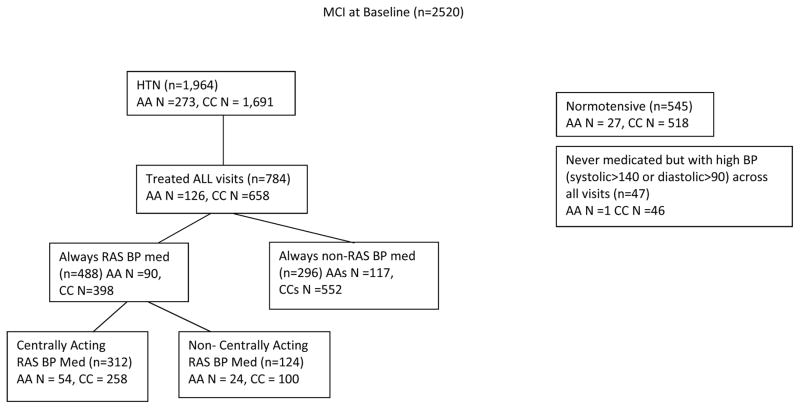

Figure 1 shows the participants included in the analyses. There were 2,520 participants with MCI at baseline who had 2 or more follow-up visits. Of these, 1,964 (77.9%) were classified as hypertensive and 545 (21.6%) were normotensive. Among hypertensive participants, 273 (13.9%) were African American and 1691 (86.1%) were Caucasian. 488 participants were taking RAS medications across all visits and 296 were RAS non-users at all visits. Among RAS users, 312 were taking BBB-crossing medications while 124 were taking non-BBB crossing formulations.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of participants included in the present study. Note: Analyses include only participants treated for hypertension at each study visit. Participants with high blood pressure but not on a medication, as well as normotensives were not included.

AA = African American, CC = Caucasian, RAS = renin-angiotensin system, BP = blood pressure.

*Note: Participants who alternated between centrally acting and non-centrally acting medications across visits were excluded for the BBB group analysis, but were included in the RAS vs. non-RAS acting medication analyses.

Table 1 lists baseline demographic and clinical variables by RAS user group. Both groups were well educated (15 yrs), older (75 yrs), and most were diagnosed with amnestic MCI (79% and 84% for RAS users and RAS non-users respectively). Approximately one quarter of participants were taking a medication indicated for AD. RAS users (N=488) vs. non-users (N=296) differed on measures of systolic BP (p < 0.001) and self-reported diabetes (p < 0.001), such that RAS users had higher BP values and higher prevalence of diabetes. There was one difference on cognitive test performance at baseline, such that non-RAS users to performed better on Digit Span Forward (p = 0.01; data not shown). There were no between group differences in incident stroke at baseline, nor during follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and vascular measures for RAS users and RAS non-users diagnosed with MCI at baseline and treated with an antihypertensive medication.

| Variable | RAS Users N = 488 |

RAS non-users N = 296 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 74.6± 8.0 | 75.5±8.8 | p = 0.15 |

| Gender (% Male) | 46% | 49% | p = 0.56 |

| Education (yrs) | 15.0±0.63 | 14.9±0.61 | p = 0.71 |

| Systolic (mmHg) | 138.1±(18.9) | 132.6±(15.5) | p < 0.00 |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 74.8±(10.8) | 74.1±(9.7) | p = 0.34 |

| Amnestic MCI | 79% | 84% | p = 0.07 |

| Stroke (%) | 14 % | 16 % | p = 0.61 |

| Heart disease (%) | 40% | 44 % | p = 0.21 |

| Diabetes (%) | 22% | 0.09% | p < 0.01 |

| Depression w/in 2 years(%) | 32% | 33% | p = 0.91 |

| Ever Smoker (%) | 55.2% | 58.7% | p = 0.17 |

| AD Medication User (%) | 23% | 25% | p = 0.59 |

| AD Family History (%) | 56% | 63% | p = 0.24 |

| FU time in years | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | p = 0.81 |

Racial differences in baseline demographic, vascular, and cognitive scores were present. Caucasians were more highly educated (p< 0.01). African Americans had a higher prevalence of diabetes (p < 0.01) while Caucasians self-reported more depression (p = 0.02). Cognitive scores revealed racial differences favoring Caucasians on 8 of 10 cognitive tests. In contrast, the CDR-SOB score was significantly higher for Caucasians than African Americans. Among individuals taking an antihypertensive medication, African Americans were statistically more likely to be prescribed RAS medications (p = 0.02).

3.1 Conversion Rates to AD as a Function of RAS Medication Use

We analyzed whether there were differences in conversion rate from MCI to AD, for both 1) RAS acting vs. non-RAS acting users and 2) centrally acting RAS users vs. non-centrally acting RAS users, over an average of three years. As a whole, 280 of the 784 participants taking an antihypertensive medication converted to AD, which is consistent with reported conversion rates of 10% – 30% annually.21

Unadjusted conversion rates for each group are as follows: RAS users 161 (33.0%), RAS non-users 119 (40.2%), centrally acting RAS users 98(30.7%), non-centrally acting RAS users 48(40.0%). Adjusted results show that conversion rate from MCI to AD was significantly lower for RAS users vs. non-users (p = 0.04) and that among RAS users, those using centrally acting medication converted less often than non-centrally acting users (p = 0.06). We found no significant interaction between Caucasians and African Americans for either model, although our power to detect such an interaction was low because of the small numbers of African Americans who converted (N =35). We found no violation of the proportional hazards assumption for either model.

3.2 Impact of RAS medications on cognitive and functional ability

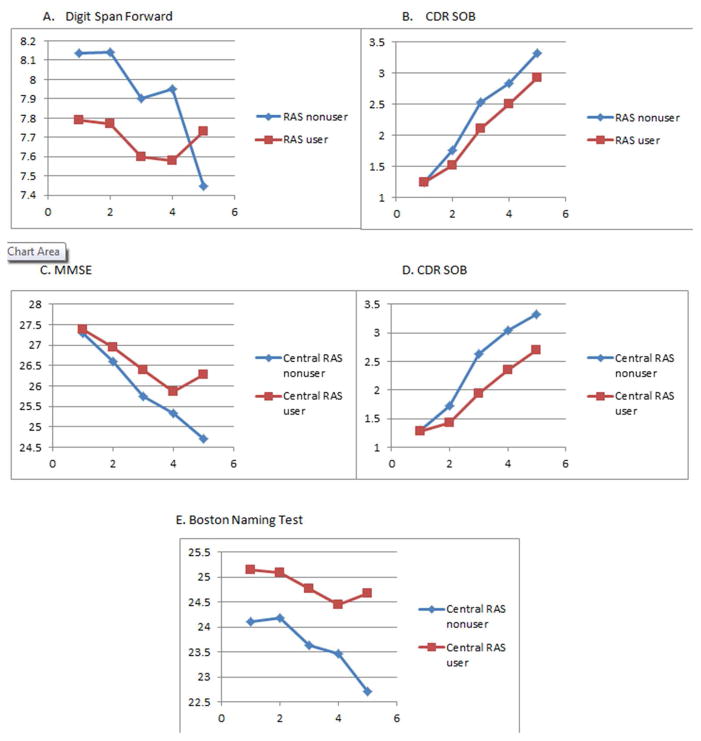

Table 2 shows results comparing RAS-acting medication users vs. RAS non-users on cognitive performance and functional ability. Results revealed a beneficial effect of RAS use compared to non-RAS medications, over time on the CDR-SOB (p < 0.01) and Digit Span Forward (p = 0.021).

Table 2.

Within group change scores and between group parameter estimates and p values for cognitive and functional ability over time by RAS medication group.

| Cognitive Test | RAS User (mean change ± SD)a | RAS Non User (mean change ± SD)a | RAS user vs non-userb | RAS use * visitc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trail A | 8.1±1.5 p < 0.0001 |

8.9 ± 2.0 p < 0.0001 |

−2.6 ± 2.1 p = 0.36 |

−.27 ± 0.5 p = 0.59 |

|

| ||||

| Trail B | 35.0 ± 4.2 p < <0.0001 |

42.0 ± 5.4 p < 0.0001 |

−5.6 ± 6.2 p = 0.36 |

−1.2 ± 1.4 p = 0.37 |

| Boston naming | −1.6 ± 0.2 p < 0.0001 |

−1.4 ± 0.3 p < 0.0001 |

0.44 ± 0.36 p = 0.22 |

−.06 ± 0.07 p = 0.39 |

| MMSE | −2.1 ± 0.2 p < 0.0001 |

−2.6 ± 0.2 p < 0.0001 |

−.12 ± 0.26 p = 0.63 |

0.10 ± 0.06 p = 0.13 |

| Logical Memory immediate | −0.3 ± 0.2 p = 0.15 |

−0.7 ± 0.3 p = 0.0178 |

−.12 ± 0.37 p = 0.74 |

0.06 ± 0.08 p = 0.47 |

| Logical Memory delayed | −0.2 ± 0.2 p = 0.49 |

−0.3 ± 0.3 p = 0.36 |

0.35 ± 0.41 p = 0.39 |

−.02 ± 0.08 p = 0.81 |

| Digit Symbol | −4.2 ± 0.5 p < 0.0001 |

−5.1 ± 0.7 p < 0.0001 |

1.98 ± 0.92 * p = 0.03 |

0.00 ± 0.18 p = 0.98 |

| Category fluency (animals) | −1.5 ± 0.3 p < 0.0001 |

−2.4 ± 0.4 p < 0.0001 |

0.40 ± 0.40 p = 0.31 |

0.12 ± 0.09 p = 0.21 |

| Digits forward | −0.2 ± 0.1 p = 0.0405 |

−0.8 ± 0.1 p < 0.0001 |

−0.39 ± 0.17 * p = 0.017 |

0.09 ± 0.04 * p = 0.02 |

| Digits backward | −0.4 ± 0.1 p = 0.0003 |

−0.5 ± 0.2 p = 0.0007 |

−0.04 ± 0.17 p = 0.78 |

0.01 ± 0.04 p = 0.85 |

| CDR-SOB | 2.1 ± 0.2 p < 0.0001 |

2.8 ± 0.2 p < 0.0001 |

0.11 ± .28 p = 0.70 |

−.17 ± 0.06 ** p < 0.005 |

Within group change over time

Change in test score over time for RAS uses vs non-users

Interaction between time RAS medication use, p<0.005 indicates significant difference in decline per year between RAS users and non-users, a positive coefficient indicates RAS users had higher slope over time for change in test scores than non-RAS users, and a negative coefficient indicates a lower slope over time

3.3 Impact of BBB crossing RAS acting medications on cognitive and functional ability

Next, we explored whether participants taking BBB-crossing RAS medications would exhibit additional cognitive protection than participants taking non-centrally acting RAS medications (Table 3, Figure 2). Three hundred and twelve and 124 participants were taking BBB-crossing RAS medications vs. non-BBB crossing medications at baseline, respectively. Results regarding rate of decline showed beneficial cognitive and functional effects on the Boston Naming Test (p < 0.01), MMSE (p < 0.01) and CDR-SOB (p < 0.01) tests, such that participants taking BBB-crossing RAS medications had less cognitive decline than those taking non-BBB-crossing RAS medications.

Table 3.

Within group change scores and between group parameter estimates and p values for cognitive and functional ability over time by centrally acting RAS medication group.

| Cognitive Test | Centrally Acting RAS User (mean change ± SD)a | Non Centrally Acting RAS User (mean change ± SD)a | Centrally acting vs. non- centrally acting)b | Centrally acting vs. non- centrally acting * visit)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trail A | 7.77 ± 1.90 p < 0.0001 |

10.11±2.94 p <0.0001 |

0.91 ± 2.97 p = 0.75 |

−1.30 ± 0.73 p = 0.75 |

| Trail B | 32.64 ± 5.27 p <0.0001 |

45.35±8.01 p < 0.0001 |

0.46 ± 8.62 p = 0.95 |

−1.20 ± 2.00 p = 0.55 |

| Boston naming | −0.85 ± 2.51 p =0.0018 |

−2.51±0.42 p <0.0001 |

−0.09 ± 0.50 p = 0.86 |

0.32 ± 0.10 ** p< 0.005 |

| MMSE | −1.62 ± 0.24 p =0.10 |

−3.05±0.36 p <0.0001 |

−0.29 ± 0.36 p = 0.42 |

0.29 ± 0.09 ** p < 0.005 |

| Logical Memory immediate | −0.21 ± 0.30 p =0.49 |

−0.76±0.46 p =0.10 |

0.93 ± 0.53 * p = 0.08 |

0.09 ± 0.11 p = 0.43 |

| Logical Memory delayed | 0.12 ± 0.29 p =0.69 |

−0.61±0.44 p =0.16 |

0.93 ± 0.59 p = 0.08 |

0.14 ± 0.11 p = 0.20 |

| Digit Symbol | −3.50 ± 0.70 p <0.0001 |

−6.48±1.09 p <0.0001 |

0.61 ± 1.30 p = 0.63 |

0.14 ± 0.13 p = 0.13 |

| Category fluency (animals) | −1.46 ± 0.35 p <0.0001 |

−1.60±0.54 p =0.0029 |

−0.05 ± 0.56 p = 0.92 |

0.14 ± 0.13 p = 0.28 |

| Digits forward | −0.16 ± 0.14 p =0.27 |

−0.50±0.22 p =0.0205 |

0.02 ± 0.23 p = 0.93 |

0.02 ± 0.05 p = 0.67 |

| Digits backward | −0.48 ± 0.15 p =0.0014 |

−0.30±0.23 p =0.19 |

−0.38 ± 0.23 p = 0.09 |

0.01 ± 0.06 p = 0.80 |

| CDR-SOB | 1.87±0.23 p <0.0001 |

2.40±0.34 p <0.0001 |

−0.09 ± 0.40 p = 0.81 |

−0.22 ± 0.08 ** p < 0.005 |

Within group change over time

Change in test score over time for centrally acting RAS uses vs non-users

Interaction between time and centrally acting RAS medication use, p<0.005 indicates significant difference in decline per year between RAS users and non-users, a positive coefficient indicates centrally acting RAS users had higher slope over time for change in test scores than non-centrally acting RAS users, and a negative coefficient indicates a lower slope over time

Figure 2.

Performance over time between RAS users and non-users on the: (A) Digit Span Forward test and (B) the CDR-SOB. The lower three boxes show centrally acting vs. non-centrally acting RAS medication use on the (C) MMSE, the (D) CDR-SOB and the (E) Boston Naming Test.

3.4 Race and longitudinal decline by RAS use

Due to lack of statistical power we are unable to test for racial differences in conversion rates to AD. However, to determine if there was an interaction of RAS medication use and race on cognitive and functional ability, we performed a 3 way interaction (test x race x time) for all cognitive tests and the CDR-SOB. While results generally did not reveal a consistent effect of race on the CDR-SOB or Digit Span Forward, we did see a trend of the 3 way interaction on the MMSE (p = 0.05), category fluency (p = 0.04), and Digit Span Backwards (p = 0.03) tests, such that African Americans taking RAS medications showed more robust cognitive benefits than Caucasians taking RAS medications, though these p values were not considered significant with our conservative p value of 0.027. Finally, we performed a second 3-way analysis (test x race x time) to test for racial effects regarding centrally acting RAS medications. Unlike the results of RAS vs. non-RAS users, analyses of centrally acting RAS users vs. non-centrally acting RAS users did not reveal an effect of race on functional or cognitive ability.

4. Conclusions

Our main results are that individuals taking RAS acting antihypertensives for at least three years were less likely to convert from MCI to AD and showed less cognitive and functional decline compared to individuals taking non-RAS acting antihypertensives. Results also show that BBB crossing RAS medications conferred additional cognitive and functional benefits compared to non-BBB crossing RAS medications in individuals with MCI. These results did not generally differ between Caucasians and African Americans. However, for three cognitive tests African Americans benefited more than Caucasians from RAS acting medications.

Our results are in line with a prior observational study reporting slower disease progression among AD patients undergoing treatment of atherosclerosis and dyslipidemia vs. untreated patients. 22 In studies investigating conversion rate from MCI to AD, one study reported that treatment with any antihypertensive therapy was associated with slower disease conversion, but only in participants with circulatory dysregulation. A secondary analysis of a clinical trial reported that diuretics were associated with reduced conversion to AD among MCI patients.23 Results from both studies were observed irrespective of any change in BP levels.

Some prior studies have suggested both cognitive and functional benefits associated with BBB-crossing, RAS acting antihypertensives. Epidemiological, histopathological, and more recently, clinical data 9,24 suggest that the RAS is involved in AD incidence and progression, potentially via direct actions on Aβ neuropathology. 24 Another study assessed the ability of 55 different antihypertensives to reduce Aβ oligomerization in vitro in hippocampal neurons from Tg2576 AD mice and found that RAS acting medications (i.e. valsartan) attenuated oligomeric Aβ pathology and Aβ mediated cognitive deterioration.25 In cohort studies, Sink et al.8 and Ohrui et al.2 reported that centrally acting RAS medications reduced cognitive decline, as assessed by the Modified Mini-Mental State Test and decreased AD incidence compared to non-centrally acting RAS medications. In addition, our group 26 has reported that individuals taking RAS medications vs. non-RAS medications exhibited reduced amyloid accumulation and AD-related pathologic changes upon autopsy.

RAS medications also may have benefits in patients with AD. In studies assessing functional ability among AD patients, RAS medications have been associated with improved exercise tolerance and less risk of falls.27 A recent secondary analysis from a randomized trial showed that treatment with centrally acting RAS medications reduced functional decline in AD patients, as measured by the CDR-SOB, compared to patients taking non-centrally acting RAS medications.28

That the present study revealed an additional benefit of BBB-crossing RAS medications on conversion rate and cognitive and functional decline in MCI patients may support the hypotheses that the role of the BBB in the RAS - AD relationship is particularly important. Indeed, the contribution of BBB permeability to cognitive impairment, as well as the salutary influence of BBB-crossing RAS medications on cognition, have been reported.29 Moreover, our group has reported that BBB-crossing RAS medications are able to significantly reduce ACE levels in the brain among individuals at risk for AD by virtue of a parental history.9

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to investigate conversion rate and the cognitive and functional effects of centrally acting RAS medication use in African American and Caucasians with MCI. The first benefit of this study was that participants were diagnosed with MCI at baseline. Most cohort studies and metaanalyses include cognitively normal individuals or those with established AD. Present data show that clinically significant and measurable effects of RAS medication use are detectible during prodromal disease stages, which is the optimal time to stage an intervention. It is unlikely that BP control explains our results, as non-RAS acting medication users had statistically better BP control compared to RAS acting medication users (p < 0.00, Table 1).

Another strength is the diagnostic expertise at individual ADC testing sites and the comprehensive battery of tests included. Additionally, to our knowledge, no other study has included such a large sample of African Americans in an investigation of RAS-acting medications and AD. Some research shows that African Americans are at higher risk for AD and hypertension than Caucasians, though some research regarding reading level and education quality may explain some of the AD related discrepancies.30 While not observed in this study, differences typically exist in the types of BP medications prescribed to Caucasians vs. African Americans based on past studies of clinical efficacy and outcomes including stroke. These racial discrepancy prescription recommendations were recently reiterated in the 2014 Guidelines for Blood Pressure Management. Compared to Caucasians, African Americans are more likely to be prescribed antihypertensive therapy in general, and are prescribed calcium channel blockers and diuretics, while Caucasians are likely to be prescribed RAS acting antihypertensives. Based on current results, not only are centrally acting RAS medications cognitively and functionally beneficial in African Americans, but African Americans may benefit more than Caucasians, as evidenced by less decline in African Americans vs. Caucasians among RAS users on 3 of 10 cognitive tests. Targeting groups who are most at risk for AD, with an existing treatment options, should be a priority for future AD clinical trials.

4.1 Limitations

Our sample consists of research volunteers with more education and likely better overall cardiovascular health profiles than the general population and thus results may not be generalizable. However, we have no apriori reason to believe that the effect of RAS medications differs between those with more or less education. Information regarding medication duration and dose was not available, and should be included in future analyses, particularly because African Americans are generally prescribed higher doses of RAS medications.

4.2 Future Directions

Further research, particularly clinical trials, investigating the influence of BBB-crossing RAS medications on AD biomarkers during prodromal disease stages is warranted. Studies utilizing neuroimaging and collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) will be particularly crucial to fully understanding the AD - RAS relationship to preclinical AD related neuropathology.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported by the Emory Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (NIH-NIA 5 P50 AG025688) and National Institute on Aging (K01AG042498). This project was accomplished through the auspices of the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC), a NIH-NIA funded Center that facilitates collaborative research. NACC provided the data used in this study under cooperative agreement number U01 AG016976. We thank the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ participants for their willingness to devote their time to research, and the staff members who work tirelessly to make the research possible.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Hanninen T, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and late-life mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. Neurology. 2001 Jun 26;56(12):1683–1689. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohrui T, Tomita N, Sato-Nakagawa T, et al. Effects of brain-penetrating ACE inhibitors on Alzheimer disease progression. Neurology. 2004 Oct 12;63(7):1324–1325. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140705.23869.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. May;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craft S. The role of metabolic disorders in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia: two roads converged. Archives of neurology. 2009 Mar;66(3):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savaskan E, Hock C, Olivieri G, et al. Cortical alterations of angiotensin converting enzyme, angiotensin II and AT1 receptor in Alzheimer’s dementia. Neurobiology of aging. 2001 Jul-Aug;22(4):541–546. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miners JS, Ashby E, Van Helmond Z, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels and activity in Alzheimer’s disease, and relationship of perivascular ACE-1 to cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 2008 Apr;34(2):181–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miners JS, van Helmond Z, Raiker M, Love S, Kehoe PG. ACE variants and association with brain Abeta levels in Alzheimer’s disease. American journal of translational research. 2010;3(1):73–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sink KM, Leng X, Williamson J, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cognitive decline in older adults with hypertension: results from the cardiovascular health study. Archives of internal medicine. 2009 Jul 13;169(13):1195–1202. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wharton W, Stein JH, Korcarz C, et al. The effects of ramipril in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease: results of a pilot clinical trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32(1):147–156. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes JM, Barnes NM, Costall B, Horovitz ZP, Naylor RJ. Angiotensin II inhibits the release of [3H]acetylcholine from rat entorhinal cortex in vitro. Brain research. 1989 Jul 3;491(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohrui T, Matsui T, Yamaya M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in Japan. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004 Apr;52(4):649–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52178_7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2009 Apr-Jun;23(2):91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011 May;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodrill C. A neuropsychological battery for epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1978;19:611–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1978.tb05041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neuropsychological tests. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1982 Jun;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devanand DP, Folz M, Gorlyn M, Moeller JR, Stern Y. Questionable dementia: clinical course and predictors of outcome. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997 Mar;45(3):321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deschaintre Y, Richard F, Leys D, Pasquier F. Treatment of vascular risk factors is associated with slower decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009 Sep 1;73(9):674–680. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b59bf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasar S, Xia J, Yao W, et al. Antihypertensive drugs decrease risk of Alzheimer disease: Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study. Neurology. 2013 Sep 3;81(10):896–903. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a35228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajjar I, Hart M, Chen YL, et al. Antihypertensive therapy and cerebral hemodynamics in executive mild cognitive impairment: results of a pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013 Feb;61(2):194–201. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Ho L, Chen L, et al. Valsartan lowers brain beta-amyloid protein levels and improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007 Nov;117(11):3393–3402. doi: 10.1172/JCI31547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajjar I, Brown L, Mack WJ, Chui H. Impact of Angiotensin receptor blockers on Alzheimer disease neuropathology in a large brain autopsy series. Archives of neurology. 2012 Dec;69(12):1632–1638. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onder G, Penninx BW, Balkrishnan R, et al. Relation between use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and muscle strength and physical function in older women: an observational study. Lancet. 2002 Mar 16;359(9310):926–930. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Caoimh R, Healy L, Gao Y, et al. Effects of centrally acting Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors on functional decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014 Jan 1;40(3):595–603. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelisch N, Hosomi N, Mori H, Masaki T, Nishiyama A. RAS inhibition attenuates cognitive impairment by reducing blood- brain barrier permeability in hypertensive subjects. Current hypertension reviews. 2013 May;9(2):93–98. doi: 10.2174/15734021113099990003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Sano M, et al. Effect of literacy on neuropsychological test performance in nondemented, education-matched elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 1999 Mar;5(3):191–202. doi: 10.1017/s135561779953302x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]