Abstract

Objective

This paper examines trends in cigarette prices and corresponding purchasing patterns over a 9 year period and explores characteristics associated with the quantity and location of cigarettes purchased by adult smokers in the United States.

Methods

The data for this paper come from a nationally representative longitudinal survey of 6,669 adult smokers (18 years and older) who were recruited and surveyed between 2002 and 2011. Telephone interviews were conducted annually, and smokers were asked a series of questions about the location, quantity (i.e., single vs. multiple packs or cartons), and price paid for their most recent cigarette purchase. Generalized estimating equations were used to assess trends and model characteristics associated with cigarette purchasing behaviors.

Results

Between 2002 and 2011, the reported purchase of cigarette cartons and the use of coupons declined while multi-pack purchases increased. Compared with those purchasing by single packs, those who purchased by multi-packs and cartons saved an average of $0.53 and $1.63, respectively. Purchases in grocery and discount stores declined, while purchases in tobacco only outlets increased slightly. Female, older, white smokers were more likely to purchase cigarettes by the carton or in multi-packs and in locations commonly associated with tax avoidance (i.e., duty free shops, Indian reservations).

Conclusions

As cigarette prices have risen, smokers have begun purchasing via multi-packs instead of cartons. As carton sales have declined, purchases from grocery and discount stores have also declined, while an increasing number of smokers report low tax sources as their usual purchase location for cigarettes.

Keywords: taxation, advertising and promotion, economics, price

INTRODUCTION

Many key tobacco control policies are implemented in order to (1) reduce cigarette consumption among current smokers, and (2) discourage tobacco consumption among nonsmokers, especially youth.[1, 2] The most effective way to achieve these goals is to increase the price of cigarettes.[3]The higher the price of purchasing a pack of cigarettes, the less likely it is that people will buy and consume cigarettes.[4]

However, there are many factors that can disrupt the simple relationship between the price of cigarettes and consumption. For example, consumers can offset higher prices by purchasing cigarettes in bulk such as in cartons or in multi-packs rather than as single packs. In addition, smokers can switch to lower priced cigarette brands, switch to brands offering price discounts, and shop for cigarettes in locations where cigarettes are less expensive.[5, 6] Finally, smokers can respond to higher cigarette prices by reducing their daily intake of cigarettes or stop their cigarette consumption all together. While not all smokers will necessarily engage in price-minimizing behaviors, the steady rise in cigarette prices coupled with increasing rates of unemployment, stagnant and/or declining wages, and higher household expenses for items like gasoline and food have combined over the past several years to make cigarettes less affordable. A recent article from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) United States Survey reported an increase in the use of discount cigarettes by US smokers after the 2009increase of $0.61 in the federal excise tax (FET) on cigarettes.[7]

Previous studies from the ITC Project have examined price minimizing behaviors in relationship to smoking cessation and smoker socio-economic status using data from the US, UK, Canada, and Australia.[6, 8] The present study examines trends in purchasing patterns in a group of US adult smokers surveyed annually between 2002 and 2011. During this time period, cigarette prices increased as a result of both state and federal tax increases. In addition, cigarette manufacturers began to compete more directly on purchase price rather than imaged based advertising due to restrictions in advertising.[9]

This paper extends the previous work by (1) examining trends in cigarette prices and typical quantity of cigarettes purchased (i.e., single vs. multiple packs or cartons), use of coupons and locations where cigarettes are typically purchased; (2) assessing characteristics related to bulk purchasing, coupon use, and tax avoidance; and (3) observing how these activities coincide with changes in pricing and tax rates. Taken together, this information is used to evaluate the trends in, and the profile of smokers who use tactics to lower their cigarettes costs in response to increased state and federal cigarette excise taxes over a 9-year period.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

This paper uses data from a nationally representative longitudinal survey of 6,669 adult current smokers who were recruited and surveyed between 2002 and 2011 for the International Tobacco Control (ITC) US Survey. Standardized telephone interviews were conducted annually. At initial enrollment, survey participants included adult smokers (18 years of age and older) who reported that they had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and had smoked at least 1 cigarette in the past 30 days. Probability sampling methods were used to recruit the sample using random-digit dialing. If multiple adult smokers were present in the home, the next-birthday method was used to select the respondent. Survey participants who were lost to follow-up in subsequent survey waves were replenished using the same procedures as the original recruitment. This process was used to maintain a sample size of 1500-2000 participants per wave. The average attrition rate was 35% for each survey wave. Further details of the survey methodology have been documented elsewhere.[10]

Measures

Quantity of Cigarettes Purchased

Participants who reported smoking factory-made cigarettes were asked whether they bought cigarettes by carton, pack, or by individual cigarettes out of a pack on their last purchase occasion. A standard carton of cigarettes contains 10 individual packs of 20 cigarettes each. For the purposes of this study, multi-pack purchases were defined as purchases of >1 and <10 individual packs of cigarettes. Bulk purchases were indicated by purchases of more than a single package of cigarettes (i.e., either multiple packs or cartons). Previous studies have described multi-pack sales in terms of manufacturers “buy one get one free” promotions,[11] however, multi-packs do not need to be part of a special price promotion offer.

Purchasing Locations

Participants were asked where they bought their cigarettes on their last purchase occasion. Purchase locations were selected from a pre-defined list which included the following categories: (1) convenience store/gas station; (2) grocery, discount or drug store; (3) tobacco outlets, smoke shops; (4) Indian reservation; (5) liquor store; (6) outside of the state; (7) duty-free; (8) outside of the country; (9) from a toll-free number; (10) from the internet; and (11) other. Text responses entered under ‘other’ were either added to the appropriate existing category (where appropriate) or left as ‘other.’ Among purchase locations, a purchase made at an Indian reservation; outside of one's home state; duty-free; from a toll-free number; outside of the country; or from the internet were designated as locations with the potential for tax avoidance (low tax location).

Use of Coupon/Special Price Discounts

Participants were also asked whether they used any coupons or received special discounts on their last purchase of cigarettes. Those responding ‘yes’ were considered positive for coupon/discount use.

Purchase price

Participants were asked to report the amount they paid for the cigarettes they purchased last. Self-reported purchase prices were standardized to the cost paid for a single pack of 20 cigarettes and adjusted to reflect the price paid in 2011 US dollars.[12]

Data and Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize trends in per pack cigarette prices and purchasing habits between 2002 and 2011. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to (1) test for trends in bulk purchasing, coupon/special discount usage, and purchase locations; (2) estimate adjusted wave specific prevalence rates for each of the outcomes, and (3) model the characteristics of participants associated with bulk purchasing and tax avoidance.[13] Because all of the outcomes of interest were dichotomous, a repeated measures binomial distribution with the logit link was used for the regression models. An unstructured correlation structure was used to account for correlation among repeated measures on subjects. In cases where the model did not converge or the software indicated that a simpler correlation structure was more appropriate, an exchangeable correlation structure was used. We tested for linear trends in outcomes from 2002 to 2011. We also tested for differences in outcomes between the survey waves conducted prior to (Wave 7, 2008-9) and after (Wave 8, 2010-11) the $0.61 increased in the FET on April 1, 2009. Variables examined as predictors of bulk purchasing and tax avoidance included the participant's gender, age, race, household income (i.e., defined as low: ≤ $29,999; medium: $30,000-$59,999; or high: ≥ $60,000), education (i.e., defined as low: ≤ high school; moderate: some college/tech/trade school, no degree; high: university degree or higher), level of nicotine dependence (i.e., measured by heaviness of smoking index [scored 0-6] and categorized as low: ≤ 4 or high: >4), intention to quit smoking, geographic region of US (i.e., Northeast, South, Midwest, or West), and brand value type (i.e. premium vs. discount). Brand value type was determined using representations from the manufacturers and has been described elsewhere.[7] Results were weighted to reflect the population composition of US adult smokers and all analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3.[14]

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study sample. In general, the sample is representative of the adult smoking population in the United States, with a slight overrepresentation of women and smokers between 40 and 54 years of age. While 44.5% of participants completed at only a single survey, approximately 55.5% completed two or more surveys.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of ITC United States Sample (N=6,669)

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 3032 | (46.5) |

| Female | 3637 | (54.5) |

| Age | ||

| 18-24 | 749 | (11.2) |

| 25-44 | 1710 | (25.6) |

| 45-54 | 2436 | (36.5) |

| 55+ | 1774 | (26.6) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 668 | (10.1) |

| Other | 813 | (12.2) |

| White | 5163 | (77.7) |

| Educationa | ||

| Low | 3037 | (45.6) |

| Moderate | 2547 | (38.2) |

| High | 1073 | (16.1) |

| No Answer | 12 | (0. 2) |

| Incomeb | ||

| Low | 2454 | (36.8) |

| Moderate | 2182 | (32.7) |

| High | 1542 | (23.1) |

| No Answer | 491 | (7. 4) |

| # of Participants Recruited at each Survey Wave | ||

| Wave 1 | 2140 | (32.1) |

| Wave 2 | 684 | (10.3) |

| Wave 3 | 889 | (13.3) |

| Wave 4 | 742 | (11.1) |

| Wave 5 | 745 | (11.1) |

| Wave 6 | 711 | (10.7) |

| Wave 7 | 382 | (5.7) |

| Wave 8 | 376 | (5. 6) |

| # Surveys Completed by Respondents | ||

| 1 | 2969 | (44.5) |

| 2 | 1519 | (22.8) |

| 3 | 876 | (13.1) |

| 4 | 498 | (7.5) |

| 5 | 319 | (4.8) |

| 6 | 212 | (3.2) |

| 7 | 124 | (1.9) |

| 8 | 152 | (2.3) |

Education defined as low= ≤ high school; moderate=some college/tech/trade school, no degree; high= university degree or greater

Income defined as low = ≤ $29,999; moderate = $30,000-$59,999; high ≥$60,000

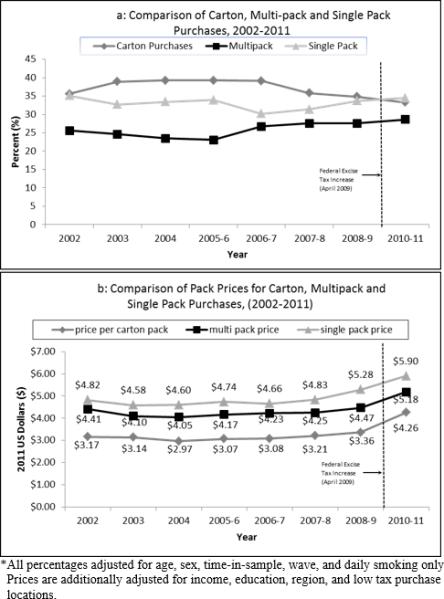

Price Paid Per Pack and Purchase Quantity

Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of carton, multi-pack, and single pack purchases along with the average price paid for cigarettes from each survey wave from 2002-2011. The sharpest increase in the price paid for a package of cigarettes was observed between 2009 and 2011, corresponding to the $0.61 increase in the federal excise tax on cigarettes. Over the entire study period, most smokers purchased by the pack rather than by the carton. However, carton purchases began to decrease after 2007. Comparing the purchase price paid for cartons to single packs, the average savings per pack was $1.63 for carton purchases, although there were fluctuations in savings over the survey period. On average, purchasing cigarettes by multi-packs saved $0.53 on average than purchasing a single pack. No statistically significant linear trends were detected in carton purchases (35.6% to 33.3%; p=0.36) or single pack purchases (35.1% to 34.5%, p=0.40) while a slight increase was observed in multi-pack purchases (25.6% to 28.6%; p<0.05) from 2002 to 2011. Over the survey, the prevalence of switching from cartons to multi-packs ranged from 3.7-7.2%, while the prevalence of switching from single packs to multi-packs ranged from 4.3-6.5% from 2002-2011. No statistically significant linear trends over time were detected.

Figure 1.

Trends in Carton and Pack Purchases with Average Price Paid Per Pack, 2002-2011*

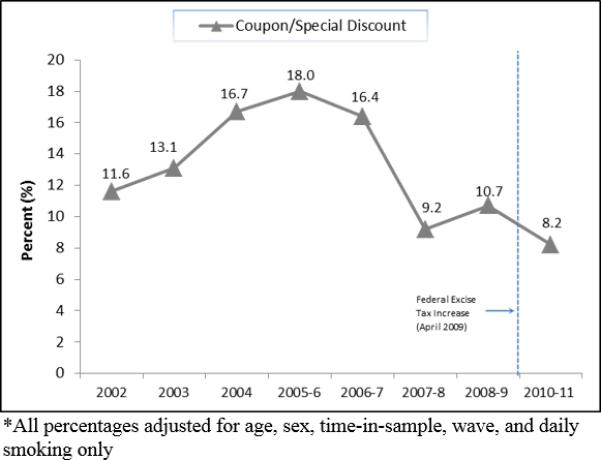

Coupon Use and Special Discount Trends

As shown in Figure 2, the reported use of coupon/special discount was relatively low from 2002-2011. The use of coupons and price discounts declined after 2005 when multi-pack purchasing began to increase, corresponding to the decline in manufacturer expenditures for coupons.[9]

Figure 2.

Coupon/Special Discount Use, 2002-2011*

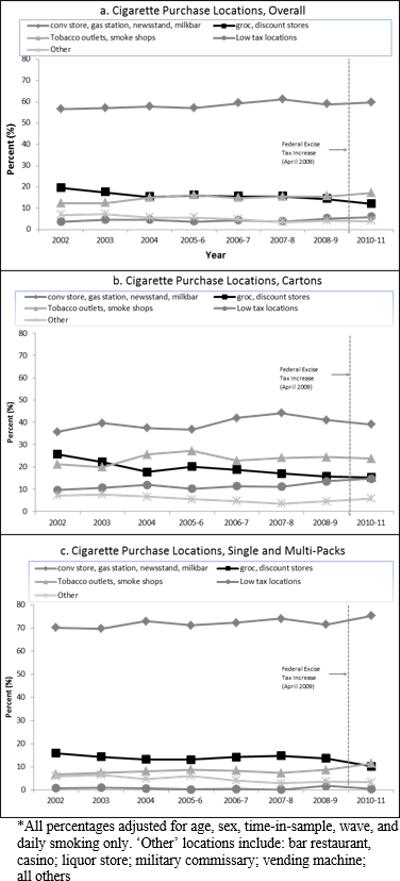

Cigarette Purchase Location Trends

Figure 3 depicts the locations of cigarette purchase over the eight survey waves. (Data values for Figure 3 are available in Appendix 1 online). Convenience stores and gas stations were the most frequently reported locations for cigarette purchases in all survey waves, followed by grocery and discount stores, and tobacco outlets (Figure 3a). Purchases from convenience stores/gas stations were fairly stable over the survey period from 2002 to 2011 (56.6% to 59.7%; p=0.08). Decreases in purchases in grocery, discount and drug stores (19.6% to 12%; p<0.01) and ‘other’ locations, (6.9% to 4.0%; p<0.01) were detected from 2002-2011. The use of tobacco outlets for purchases increased over this time period from 12.3% to 17.1% (p=0.00). Purchases from low tax locations rose from 3.6% in 2002 to 5.9% in 2011, although this result was not statistically significant (p=0.15). This trend was likely due in part to purchasing on Indian reservations, which rose from 2.2% to 3.6% from 2002 to 2011 (p=0.04).

Figure 3.

Locations of Purchase Overall and by Bulk Purchase Type*

Cartons were purchased most often from convenience stores and gas stations; grocery, discount and drug stores; and tobacco outlets (Figure 3b). Purchases of cartons decreased in grocery and discount stores (25.7% to 15.3%; p=0.00) and also in ‘other’ locations (7.2% to 5.8%; p=0.03) from 2002 to 2011. Carton purchases from Indian reservations rose from 5.3% to 10.2% (p=0.00) over the survey period. The majority of single and multi-pack purchases were made at convenience stores and gas stations (Figure 3c). The prevalence of single and multiple pack purchases decreased in ‘other’ locations from 5.9% to 3.3% (p<0.01) over the study period.

Use of bulk purchasing, coupons, or tax avoidance has been highly consistent over the survey period (data not shown). Overall, 67-72% of smokers in each wave utilized either bulk purchasing, coupons, or tax avoidance behaviors from 2002-2011.

Bulk Purchasing and Tax Avoidance Characteristics

Table 2 depicts factors associated with carton purchases, multi-pack purchases and tax avoidance. All outcomes were associated with female gender, older age (age >=25 years), White race, greater nicotine addiction, daily smoking, and use of discount cigarettes and intention to quit smoking. Additionally, carton purchasing was associated with high income. Carton purchasing was more likely in the southern region and less likely in the northeastern region when compared with the western region. Multi-pack purchases (compared with single pack purchase) were additionally associated with moderate income (compared with high income), and living in the mid-western and southern regions of the US. Tax avoidance was more likely in the northeastern region and less likely in the mid-western and southern regions, when compared with the western region. Bulk purchasing and tax avoidance was less likely among smokers intending to quit. Controlling for age, sex, race, addiction, smoking status, intention to quit smoking, brand value, income, education, region, time-in-sample and wave we did not observe a statistically significant change in bulk purchasing and tax avoidance before and after the implementation of the federal excise tax in 2009.

Table 2.

Characteristics Associated with Bulk Purchasing and Tax Avoidance

| Model 1 Carton Purchases vs. Non Carton Purchases (N=6206) | Model 2 Multi-pack vs. Single Pack Purchases (N=4109) | Model 3 Tax Avoidance Location vs. Other Purchase Location (N=6246) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Sex | ||||||

| Females vs. Males | 1.36 | (1.21-1.53) | 1.33 | (1.17-1.52) | 1.51 | (1.18-1.92) |

| Age | ||||||

| 25-39 vs. 18-24 | 2.13 | (1.65-2.76) | 1.70 | (1.35-2.14) | 1.45 | (0.75-2.80) |

| 40-54 vs. 18-24 | 3.85 | (3.00-4.95) | 2.11 | (1.68-2.63) | 2.38 | (1.27-4.45) |

| 55-max vs. 18-24 | 7.59 | (5.86-9.84) | 2.44 | (1.89-3.15) | 2.97 | (1.55-5.66) |

| Race | ||||||

| Other vs. White | 0.60 | (0.49-0.73) | 0.75 | (0.61-0.93) | 0.77 | (0.53-1.11) |

| Black vs. White | 0.23 | (0.17-0.30) | 0.40 | (0.32-0.51) | 0.12 | (0.04-0.32) |

| Incomea | ||||||

| Low vs. high | 0.66 | (0.56-0.76) | 1.13 | (0.94-1.36) | 1.13 | (0.84-1.52) |

| Middle vs. high | 0.79 | (0.69-0.91) | 1.20 | (1.01-1.43) | 0.95 | (0.71-1.28) |

| No answer vs. high | 0.94 | (0.74-1.20) | 1.06 | (0.77-1.48) | 0.73 | (0.41-1.28) |

| Educationb | ||||||

| Low vs. high | 0.99 | (0.84-1.17) | 0.87 | (0.70-1.07) | 0.94 | (0.67-1.33) |

| Middle vs. high | 0.97 | (0.85-1.11) | 1.02 | (0.88-1.19) | 0.71 | (0.54-0.93) |

| Nicotine Dependencec | ||||||

| ≥4 vs <4 | 1.45 | (1.32-1.60) | 2.06 | (1.74-2.44) | 1.44 | (1.19-1.75) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Daily vs. non-daily | 2.76 | (2.16-3.52) | 2.19 | (1.71-2.81) | 1.63 | (0.85-3.14) |

| Brand Value | ||||||

| Premium vs. Discount | 0.58 | (0.51-0.65) | 0.74 | (0.63-0.86) | 0.50 | (0.39-0.63) |

| Region | ||||||

| Midwest vs. West | 0.93 | (0.77-1.11) | 1.40 | (1.15-1.71) | 0.29 | (0.20-0.42) |

| Northeast vs. West | 0.73 | (0.60-0.88) | 0.95 | (0.77-1.18) | 1.93 | (1.46-2.55) |

| South vs. West | 1.25 | (1.06-1.48) | 1.41 | (1.16-1.71) | 0.18 | (0.12-0.26) |

| Quit Intentions | ||||||

| Beyond 6 months vs. not quitting | 0.79 | (0.71-0.87) | 0.80 | (0.68-0.94) | 0.68 | (0.55-0.84) |

| 1-6 months vs. not quitting | 0.57 | (0.50-0.64) | 0.69 | (0.58-0.82) | 0.69 | (0.54-0.90) |

| Within next month vs. not quitting | 0.46 | (0.39-0.55) | 0.51 | (0.41-0.64) | 0.61 | (0.42-0.89) |

| Wave | ||||||

| Wave 1 vs. 8 | 1.02 | (0.80-1.30) | 0.92 | (0.68-1.25) | 0.61 | (0.38-0.99) |

| Wave 2 vs. 8 | 1.16 | (0.92-1.47) | 0.98 | (0.73-1.32) | 0.71 | (0.45-1.11) |

| Wave 3 vs. 8 | 1.19 | (0.95-1.48) | 0.90 | (0.67-1.20) | 0.72 | (0.47-1.11) |

| Wave 4 vs. 8 | 1.25 | (1.01-1.54) | 0.91 | (0.68-1.21) | 0.61 | (0.40-0.92) |

| Wave 5 vs. 8 | 1.18 | (0.97-1.44) | 1.17 | (0.89-1.55) | 0.71 | (0.48-1.07) |

| Wave 6 vs. 8 | 1.04 | (0.87-1.25) | 1.09 | (0.82-1.45) | 0.61 | (0.41-0.89) |

| Wave 7 vs. 8 | 0.99 | (0.84-1.18) | 1.02 | (0.76-1.36) | 0.91 | (0.64-1.28) |

* p<0.05. Models also adjusted for time-in-sample. Statistically significant odds ratios are in boldface.

Income defined as low ≤ $29,999; medium = $30,000-$59,999, or high ≥ $60,000.

Education defined as low: ≤ high school; moderate: some college/tech/trade school, no degree; high: university degree or higher.

Nicotine dependence measured by Heaviness of Smoking Index [scored 0-6] and categorized as either low: ≤ 4, or high: > 4

DISCUSSION

The average price paid for a single package of cigarettes in the United States rose steadily from 2002-2011, with a large increase observed after the 2009 federal excise tax. On a per pack basis, the price was substantially lower for purchasing by the carton than by the pack. The price differential between carton and pack sales was fairly stable over the entire study period. Despite the relative per pack price advantage of purchasing cigarettes by the carton instead by the pack, smokers are increasingly choosing to purchase their cigarettes by the pack instead of by the carton. A number of factors may have contributed to this trend. Additional analyses of these data show that many smokers appear to be smoking fewer cigarettes per day, decreasing from 19 in 2002 to 17 in 2011. Perhaps this is in response to higher cigarette prices, less disposable income, and/or increasing restrictions on when and where they are permitted to smoke. Additionally, it is possible that some smokers may find the high entry cost of a carton of cigarettes too steep, whereas the perceived lower daily per pack price seems more affordable, especially if they are intending to reduce their smoking and/or stop smoking. Additional analyses of the data found that those who were intending to quit had a 20-54% reduced odds of bulk purchasing or purchasing from a low tax location.

Results from this study found that most smokers purchased by the pack rather than by the carton, and this is consistent with other studies.[5, 15, 16]The reported use of coupons and price discounts was not all that common among the smokers we surveyed and peaked in 2005 when multi-pack purchasing increased. These trends may be reflective of changes in price promotions offered by cigarette manufacturers in response to the slowing US economy which negatively impacted the affordability of cigarettes.[6, 17] Coupon use began to decline in the later years of the survey, coinciding with a decline in manufacturer expenditures for coupon promotions.[9] Multi-packs represent an affordable option, with pricing between that of cartons and single packs. Noting price fluctuations and regional variation over the survey period, those purchasing by cartons spent an average of $51.02 per purchase occasion compared with $13.48 for multi-packs, and $5.65 for single packs.

Advertising and price promotions, particularly those at the point of sale (POS) in convenience stores and gas stations (i.e. multi-pack discounts, coupons etc.), constituted a significant proportion of cigarette manufacturer expenditures during the time period of this study, and are often implemented to strategically offset impending tax increases among current and potential smokers.[4, 18, 19] Since pack purchases were overwhelmingly more likely to be made at these locations, advertising promotions at the POS for multi-pack purchases could help to explain why multi-pack purchases increased while carton purchases declined from 2006-2011.

Examination of characteristics of smokers utilizing bulk purchasing and tax avoidance yielded similar results in that choice of discount brand was associated with bulk purchasing and tax avoidance. This may indicate that addicted smokers who exhibit these tactics to minimize price are also likely to use discount cigarette brands at some point. Previous studies have shown that older, heavier smokers were more likely to switch to discount brands,[7] while this analysis has found that older smokers were more likely to use bulk purchasing and tax avoidance methods. Overall, White, female, older, and more addicted smokers were more likely to purchase cigarettes in high quantities and try to avoid taxes. The fact that female smokers were more likely to try purchase in high quantities and try to avoid taxes is consistent with the study by Licht et al.[8] which uses ITC data from four countries. As well, studies using non ITC data have found that female smokers were more likely to purchase in ‘less expensive venues’ or from Indian reservations, and also that female smokers were more likely to use promotional offers ‘every time they see one.’[20-22] An article by Pesko et al.[16] reported that female smokers were more likely to purchase cartons, while a study by Mecredy et al.[23] found that a greater percentage of females purchased contraband tobacco regularly.

A distinguishing characteristic of carton purchasers was higher income, since greater income is needed for this method of cost-cutting; this result is consistent with those from studies by Licht et al.[8]Tax avoidance was more likely in areas where cigarette taxes (in addition to the cost of living) were highest (i.e. West and Northeast regions). Additionally, the higher total cost of cigarettes, in addition to the close proximity of Indian reservations may also explain this occurrence. Previous research has indicated that price promotions are highest where tobacco control policies are strongest (i.e. West and Northeast).[18]Work by Harding et al.[24] has also indicated that the impact of increased tax burden experienced by consumers differs by state tax rate, which, in turn, influences the extent to which consumers seek out strategies to minimize cigarette costs. Results from this study indicate that income is not associated with tax avoidance, while moderate income was associated with multi-pack purchases (compared to high income). Previous studieshave found that price sensitive smokers were more likely to take advantage of price promotions offered at the time of purchase.[4, 5]Licht et al.[8]also reported that ‘higher SES groups more likely to report traveling to a low-tax location to avoid paying higher prices’ relative to low SES groups in a study published in 2011.This may be due in part to an inability to travel to other, cheaper venues for purchases. Although these data do not provide evidence that low income is associated the potential for multi-pack purchase discounts the increasing availability of multi-pack purchases represent a more affordable option to moderate income smokers and undermines the intended effects of increased cigarette pricing among these smokers.[4] Using our definition of low income, it may be that multi-packs, like cartons, remain unaffordable to low income smokers.

Results do not indicate that the federal tax increase resulted in a statistically significant increase in bulk purchasing, tax avoidance or coupon use between Waves 7 and 8, (when the FET increase occurred); however, the price differential between those who did and did not use at least one of the strategies for price minimization was greatest after Wave 7. As well, some participants in Wave 7 were surveyed after April 2009 (323/1763 or ≈18.3%), indicating that this measure of differences from Wave 7 to 8 may be an underestimate of the differences. In order to more accurately isolate the effects of the FET, calendar year was controlled for and differences in outcomes before and after the FET increase were assessed, controlling for time-in-sample, sex, age, wave, and daily smoking. We found that the FET tax increase was associated with decreased odds of purchasing by the carton (OR=0.80; p<0.01), and increased odds of purchasing at low tax locations (OR=1.43; p=0.03). This should be interpreted carefully because other explanations could exist. First, we are unable to analyze differences in prevalence by survey year. Second, consistent price promotions in the years leading up to the tax increase may have minimized the impact in such a way that a sudden, large increase in cost from the federal taxation was not experienced, thus maintaining prior purchase habits, particularly among those purchasing by multi-packs. Price reduction by bulk purchasing appears to be a consistent occurrence, irrespective of changes in tax policies for cigarettes. Third, the changing economy during this time period could have influenced purchase behavior.

Results from this study revealed that 4-7% of participants switched from cartons to multi-packs and also from single packs to multi-packs, from 2002 to 2011. This may indicate not only reduced smoking among previous carton purchasers, but also increased smoking among those who typically purchased by single packs, due to the increased volume of cigarettes on hand, effectively offsetting the benefits of cigarette price increases. This may indicate that multi-pack purchase discounts enable reductions in smoking frequency by heavy smokers to be offset by increases in smoking by moderate to light smokers.DeCicca et al.[15] reported that carton buyers may pay lower taxes, whilenon-daily, less addicted smokers may pay taxes at a slightly higher rate. Such occurrences could explain the increase in multi-pack purchases.

While these data report valuable information regarding behaviors surrounding price increases, there are a few limitations. Our analysis is limited to the last purchase of cigarettes, rather than the usual purchase quantity, which could result in some misclassification. As well, multi-pack purchases do not necessarily indicate a multi-pack discount. In this definition, multi-pack purchases may or may not always represent ‘buy one get one free’ price promotions that are reported to the Federal Trade Commission. However, those who purchased in this manner did save more than those who purchased single packs, on average. Because the questionnaire item asks about coupons and special discounts simultaneously, we were unable to determine whether some smokers may have interpreted ‘buy-one-get-one free’ as a ‘special discount.’ As a result, we were unable to isolate multi-pack discounts from coupon use, and therefore, could not adjust per pack average price without the possibility of excluding multi-pack discounts. Nonetheless, a sensitivity analysis revealed that exclusion of all coupon/discount purchases did not affect estimates of price or prevalence among carton, multi-pack and single pack purchases. Next, we only observed small magnitudes of differences in our outcomes of interest. Despite this, small percent differences may often equate to large numbers of affected lives at the population level. As well, we did not assess purchases of single/loose cigarettes because too few participants indicated purchasing in this quantity. Additionally, small sample sizes of individual tax avoidance methods (except for Indian reservations) prevented us from being able to assess characteristics related to specific tax avoidance methods. It is possible that characteristics may differ by specific tax avoidance methods as found by Licht et al.[8]

Cigarette consumption is reduced by 2.5%-5% among smokers when prices increase 10%; however, consumers’ uses of strategies to lessen the price they pay reduce this impact.[3, 25, 26] We found that these price-reduction strategies have remained high over the last nine years in the US, with differing strategies dominating at different times. Carton, multi-pack purchasing, and coupons have long been an effective method for smokers to save money, with carton purchases more likely among those of higher SES. Multi-pack discounts and coupons serve as an effective method for all smokers (especially those of lower SES) to reduce their cigarette costs. Tax avoidance and coupon use were used less often for price reduction than bulk purchasing.

Results from this study support the notion that price promotions can induce cost savings, which can, in turn, decrease motivation for quitting smoking. The fact that over two-thirds of participants at each of the 8 survey waves over 9 years reported using bulk purchasing, coupons, or tax avoidance demonstrates the very widespread availability of cost saving measures offered by the cigarette manufacturers. Multi-pack purchasing, in particular, may especially lower motivation for quitting smoking. Tobacco manufacturers have used couponing and multi-pack discounts as a mechanism for offsetting the immediate impact of tax increases, resulting in a smaller reduction in cigarette consumption.[4]Utilizing these measures over time periods both prior to and after a tax increase circumvents the perception of a dramatic price increase that might prompt more smokers to think about quitting. Moreover, price promotions simply increase the affordability of smoking, thereby reducing smoking cessation. Standardizing the quantity of cigarettes sold to packs and/or carton sizes only and establishing minimum pricing laws would help limit the manufacturers’ ability to manipulate cigarette affordability which would help strengthen the impact of price increases on smoking cessation.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

This paper examines trends in cigarette prices and corresponding purchasing patterns from 2002 to 2011 and explores characteristics associated with the typical quantity of cigarettes purchased (i.e., single vs. multiple packs or cartons) and location where cigarettes are typically purchased by adult smokers in the United States.

As cigarette prices have risen consumers have found different ways to circumvent the increased costs of purchasing cigarettes. Over two-thirds of respondents reported using bulk purchasing, coupons, and/or tax avoidance to lower the purchase costs of cigarettes. Despite the relative per pack price advantage of purchasing cigarettes by the carton instead by the pack, smokers increasingly chose to purchase their cigarettes by the pack instead of by the carton. A number of factors may have contributed to this trend including the fact that many smokers are smoking fewer cigarettes per dayand/or increasing restrictions on when and where smokers are permitted to light up. It appears that multi-packs are beginning to replace10-pack carton sales as the primary means of bulk purchasing.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement:

This work was supported the National Cancer Institute of the United States, grant numbers R01 CA 100362, P50 CA111236, P01 CA138389, and R25 CA113951, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, grant numbers 57897, 79551, and 115016. Geoffrey T. Fong was supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute.

Footnotes

Contributorship Statement:

Cornelius, Driezen, Cummings, and Chaloupka contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and in drafting the manuscript and revising critically for important intellectual content. Fong, Cummings, and Hyland contributed to the study conception and survey design, and in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests:

KMC has served in the past and continues to serve as a paid expert witness for plaintiffs in litigation against the tobacco industry. Otherwise, the authors have no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. WHO Document Production Services; Geneva, Switzerland: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tips from former smokers: Campaign Overview. 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/about/campaign-overview.html.

- 3.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME. Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(3):235–238. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley C, et al. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(suppl 1):i62–i72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi K, Hennrikus D, Forster J, et al. Use of price-minimizing strategies by smokers and their effects on subsequent smoking behaviors. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;14(7):864–870. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Licht AS, Hyland AJ, O'Connor RJ, et al. How do price minimizing behaviors impact smoking cessation? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2011;8(5):1671–1691. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8051671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelius ME, Driezen P, Fong GT, et al. Trends in use of premium and discount cigarette brands: findings from the ITC US Surveys (2002-2011). Tobacco Control. 2014 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051045. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Licht AS, Hyland AJ, O'Connor RJ, et al. Socio-economic variation in price minimizing behaviors: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2011;8(1):234–252. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8010234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Trade Commission Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Reports for Years 2002-2010. 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.ftc.gov/reports/index.shtm.

- 10.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(suppl 3):iii12–iii18. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tauras JA, Peck RM, Chaloupka FJ. The Role of Retail Prices and Promotions in Determining Cigarette Brand Market Shares. Rev Ind Organ. 2006;28(3):253–284. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adjusting prices for inflation and creating price indices: FEWS NET markets guidance, No 3. Famine Early Warning Systems Network, United States Agency International Development; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson ME, Boudreau C, Driezen P. Incorporating time-in-sample in longitudinal survey models.. Statistics Canada International Symposium Series 2005: Methodological Challenges for Future Needs; Ottawa, ON. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.SAS Institute Inc. SAS Version 9.3. Cary, NC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeCicca P, Kenkel D, Liu F. Who Pays Cigarette Taxes? The Impact of Consumer Price Search. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2012;95(2):516–529. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pesko MF, Kruger J, Hyland A. Cigarette Price Minimization Strategies Used by Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(9):e19–e21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loomis BR, Farrelly MC, Mann NH. The association of retail promotions for cigarettes with the Master Settlement Agreement, tobacco control programmes and cigarette excise taxes. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(6):458–463. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder KM. Tobacco price promotion: local regulation of discount coupons and certain value-added sales. Center of Public Health and Tobacco Policy; Boston, MA: 2013. Available at: http://www.tobaccopolicycenter.org/documents/TR-COUPON%20FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feighery E, Rogers T, Ribisl K. Tobacco control retail price manipulation strategy summit proceedings. California Department of Health, California Tobacco Control Program; Sacramento, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyland A, Bauer JE, Li Q, et al. Higher cigarette prices influence cigarette purchase patterns. Tobacco Control. 2005;14(2):86–92. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyland A, Higbee C, Bauer JE, et al. Cigarette purchasing behaviors when prices are high. Journal of public health management and practice : JPHMP. 2004;10(6):497–500. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White VM, White MM, Freeman K, et al. Cigarette Promotional Offers: Who Takes Advantage? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30(3):225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mecredy GC, Diemert LM, Callaghan RC, et al. Association between use of contraband tobacco and smoking cessation outcomes: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2013;185(7):E287–294. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding M, Leibtag E, Lovenheim MF. The Heterogeneous Geographic and Socioeconomic Incidence of Cigarette Taxes: Evidence from Nielsen Homescan Data. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 2012;4(4):169–198. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tobacco Control. 2012;21(2):172–180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyland A, Higbee C, Li Q, et al. Access to Low-Taxed Cigarettes Deters Smoking Cessation Attempts. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(6):994–995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.