Significance

Elevated incidence of childhood leukemia relative to young adult ages is difficult to explain from the standpoint of oncogenic mutation accumulation. We applied a stochastic Monte Carlo model of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) clonal dynamics based on published age-dependent parameters of HSCs. Our modeling results demonstrate that childhood and adult HSC clonal dynamics differ by the factors that determine the number of cell divisions per clonal context. Late in life, positive selection leading to clonal expansions increases the number of cell divisions per clone, whereas in childhood a similar increase is achieved by the much higher HSC division frequencies and drift-affected clonal expansions. We provide a mathematical argument that the obtained clonal dynamics and cell division measurements can explain the age-dependent incidence of leukemia.

Keywords: childhood leukemia, somatic evolution, cancer, stochastic modeling, aging

Abstract

Young children have higher rates of leukemia than young adults. This fact represents a fundamental conundrum, because hematopoietic cells in young children should have fewer mutations (including oncogenic ones) than such cells in adults. Here, we present the results of stochastic modeling of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) clonal dynamics, which demonstrated that early HSC pools were permissive to clonal evolution driven by drift. We show that drift-driven clonal expansions cooperate with faster HSC cycling in young children to produce conditions that are permissive for accumulation of multiple driver mutations in a single cell. Later in life, clonal evolution was suppressed by stabilizing selection in the larger young adult pools, and it was driven by positive selection at advanced ages in the presence of microenvironmental decline. Overall, our results indicate that leukemogenesis is driven by distinct evolutionary forces in children and adults.

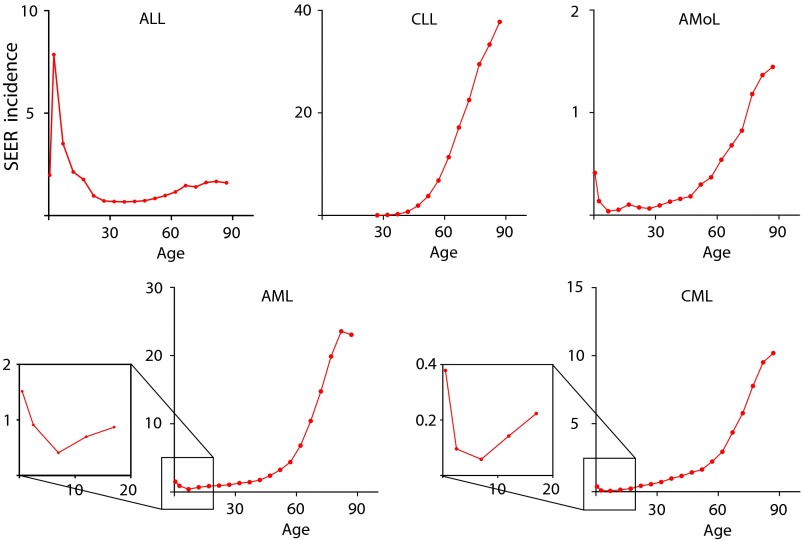

The incidence of leukemia, like most cancers in humans, increases exponentially with age. However, most types of leukemia have an early peak of incidence (at 0–7 y of age), which subsequently decreases before rising again later in life (Fig. S1). Cancer development is generally thought to result from a sequence of cancer driver mutations that promote selection for recipient cells by conferring a positive fitness advantage within competing stem cell (SC) and progenitor cell pools (1–4). The acquisition of oncogenic mutations is thus thought to be rate-limiting for cancer development, leading to increased cancer incidence with age. Within this paradigm, the higher incidence of leukemia in young children compared with young adults is puzzling, because younger tissues should have accumulated fewer mutations.

Fig. S1.

Incidence of various types of human leukemia based on Surveillance, Epidemology, and End Results (SEER) database statistics (seer.cancer.gov). Incidence per 100,000 is shown. ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia (all forms); AMoL, acute monocytic leukemia (a form of acute myeloid leukemia); CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia.

Evolution is driven by multiple forces, including mutation, selection, and drift. Although mutation is necessary for cancer development, a large body of evidence has accumulated indicating that the ability of oncogenic mutations to drive clonal evolution is not universal and depends on external factors (5–12). Carcinogenesis may therefore be driven or suppressed by non–cell-autonomous processes. One factor capable of limiting the ability of selection to influence population dynamics is drift. In evolutionary biology, the power of drift is known to be inversely related to population size (13). This relationship also holds true for mammalian tissues, as shown for intestinal SC pools, which are segregated into small groups within intestinal crypts (10, 14, 15). The number of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) per individual has been reported to be conserved across mammals at 11,000–22,000 cells in adults (16, 17), with an initial pool size of ∼300 HSCs at birth (17) (Fig. S2A). Although higher estimates of the pool size exist (18), it is clear that during prenatal development, and perhaps the early postnatal period of life, the number of HSCs is substantially smaller than the number in the adult pool. Because HSCs have been shown to effectively represent one large competing population within the body (19), and with evidence from wild populations and intestinal SCs in mind, the small size of early childhood HSC pools led us to hypothesize that early somatic evolution in HSCs would be affected by drift. We analyzed the rates of somatic evolution by measuring maximal clonal expansions at different ages and show that drift, stabilizing selection, and positive selection have a differential impact on somatic evolution at different ages.

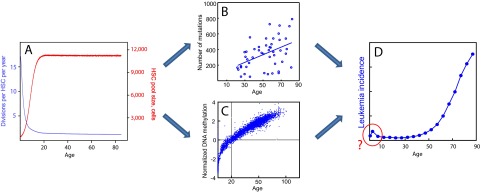

Fig. S2.

Nonlinear changes in HSC dynamics and leukemia incidence with age. (A) Modeled changes in HSC pool size (red) and cell division frequency (blue) with age inferred using data from a combination of experimental and modeling studies (16, 17) (for HSC numbers) and data for the dynamics of telomere shortening in leukocytes with age (43) (for cell division rates). (B) Accumulation of neutral mutations in AML genomes with age revealed by whole-genome sequencing, as a proxy for mutation accumulation in HSC (47). (C) Accumulation of DNA methylation changes in hematopoietic cells with age (41). (D) Leukemia incidence with age in humans (seer.cancer.gov).

Results

We previously generated a computational model that replicates stochastic cell fate decisions and cell competition for SC niche space over time (20). Monte Carlo simulation within the model allows for tracking somatic evolution across a wide range of mutation parameters, and replicates clonal divergence by capitalizing on the assumption that all random cellular damage (including DNA mutations and epigenetic changes, referred to hereafter in aggregate as “mutations”) forms a distribution of fitness effects (DFE). This DFE defines the probabilities per cell division that the accumulated damage will have a certain net effect on a cell’s fitness in its competition for niche space within the HSC compartment [details are provided by Rozhok et al. (20)]. As demonstrated for wild populations (21), the DFE that we derived for HSCs should be zero-centered (the mode, or the most frequent type of mutations, is neutral) and negatively skewed (because most phenotype-affecting mutations decrease cellular fitness) (20).

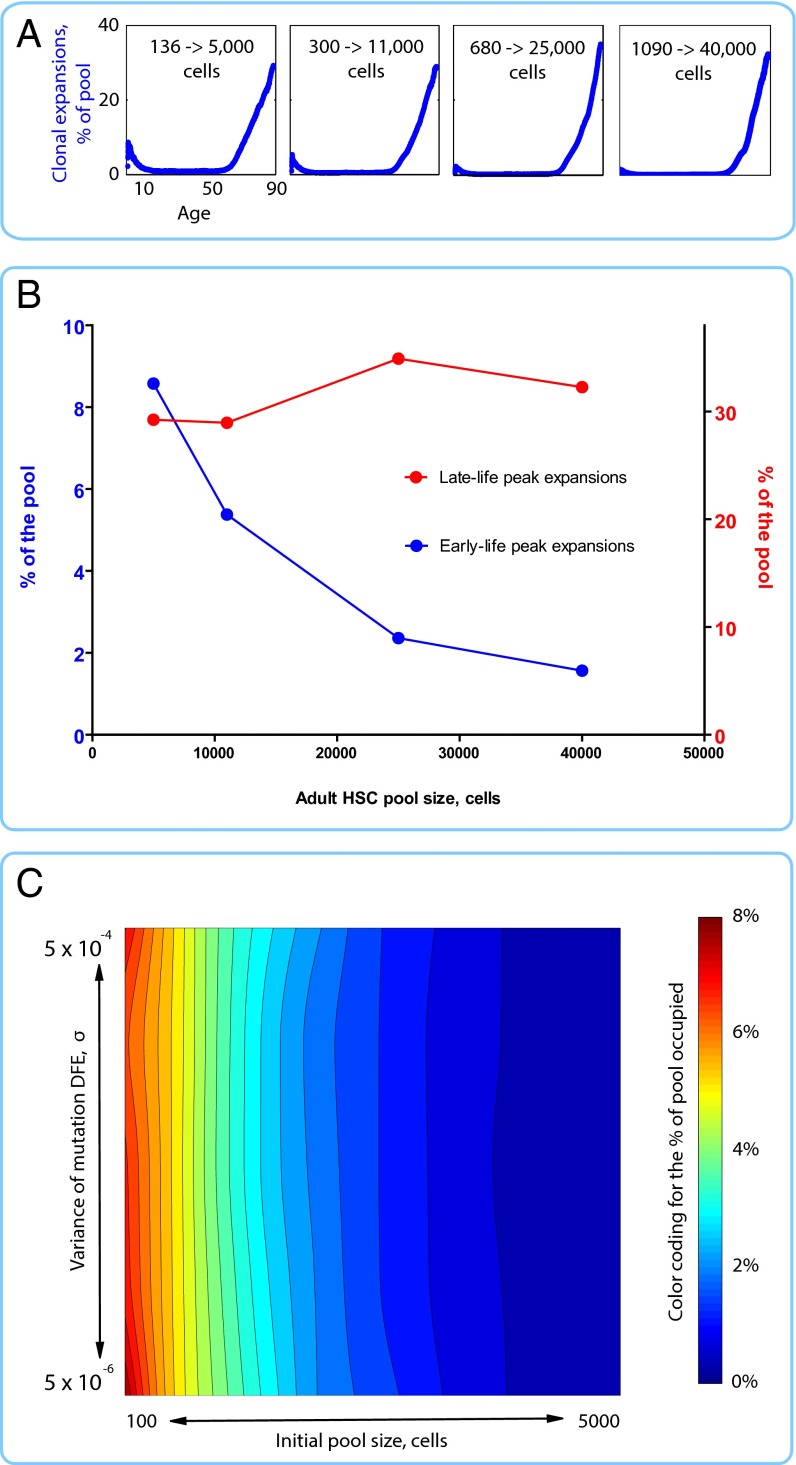

We independently manipulated the power of drift and selection within the stochastic model by altering HSC pool size and mutation DFE variance (σ), respectively. Narrow mutation DFEs (small σ) are composed of mostly neutral mutations and have limited power to generate a fitness differential among cells, whereas wide DFEs (large σ) harbor more functional mutations and generate a strong fitness differential among cells that is amenable to selection. From classic population models (22, 23), the power of random drift is known to be inversely proportional to population size (HSC pool size in our modeling), and in small populations, drift can significantly diminish the effects of selection. We measured the share of the pool occupied by the most successful clone at any given age. Given the stochastic nature of mutations and the dynamics of particular clones, the identity of the most successful clone changes over time, because individual clones are constantly competing with each other. Measuring the share of the most successful clone, rather than tracking an individual clone, allowed us to explore the upper limits of somatic evolution with age and under varying HSC pool characteristics.

The stochastic model generated age-dependent clonal expansions (Fig. 1A) that resemble the combined age-dependent incidence curve of human leukemias (Figs. S1 and S2D), with an exponential increase in late life and a smaller but notable peak in early childhood. Proportionally increasing the initial and adult HSC pool sizes led to a progressive suppression of the early childhood peak, whereas late-life expansions remained unaffected (Fig. 1 A and B). We further fixed the adult pool size at 11,000 cells and measured the maximum extent of early clonal expansions under various values of initial pool size (influencing drift) and DFE σ (influencing selection). Early clonal dynamics were relatively insensitive to changes in mutation DFE but were quite sensitive to changes in pool size (Fig. 1C). Thus, early somatic evolution in HSC pools is primarily drift-driven, with selection playing a lesser role.

Fig. 1.

Age-dependent character of somatic evolution under different initial HSC pool sizes. (A) Clonal expansions (i.e., the share of the pool occupied by the most successful clone at any given time) in HSC pools of different sizes (initial and adult pool sizes are kept proportional to the studied pool of 300 to >11,000 cells and mutation DFE variance σ = 0.0003). (B) Changes in early-life (0–10 y of age) and late-life (50–87 y of age) peak clonal expansions in response to changes in the initial and adult pool size (as in A, the initial pool size was changed to maintain the same proportional relationship with the adult pool size). (C) Landscape plot of the maximum extent of somatic evolution (measured by the percentage of the pool occupied by the most successful clone at peak expansion within the first 10 y of life) under a range of mutation DFE variance and initial pool sizes (the adult pool size is fixed at 11,000 cells).

Somatic evolution, being changes in the composition and frequencies of cellular clones, is a widespread process in normal animal tissues that does not necessarily lead to cancer development (10, 14, 24–29). However, recent evidence indicates that increased rates of clonality in SC pools are associated with increased risk for leukemias (24, 25). These studies reveal that clonality increases exponentially in HSC pools during the postreproductive portion of the human life span, consistent with the clonal dynamics generated by our model. We have argued that the probability of accumulating multiple driver mutations in one clonal context (hereafter used as a synonym of the term “clone,” reflecting cells of common descent with a common genetic/phenotypic background) heavily depends on the expansion of the clone, which contributes to the total number of cell divisions within the clone (20). An approximation of this relationship is demonstrated in Eq. S1. The total number of cell divisions within a clone by time t is represented in Eq. S1 as the term D(t), and is the product of cell division rates and clonal size as functions of time. If cell division rates, clonal size, and mutation rate are known as a function of time, this equation can be transformed as follows:

| [1] |

where Pd1…dn(t) is the probability of acquiring n drivers in one clonal context by time t, C(t) is the cell division rate as a function of time, S(t) is the size of the clonal context as a function of time, and pi is the probability of acquiring a driver di ∈ {d1, …, dn} per cell per division as a linear function of the effective mutation rate.

Whether the mutation rate changes with age is not known, particularly for human HSCs. Mutator phenotypes, however, represent a special case when the mutation rate term in Eq. 1 can significantly change the odds of multidriver cancers. In a general case, the terms C(t) (cell division rate) and S(t) (clonal size) are important factors in determining the risk of accumulating multiple drivers in one clonal context. As will be indicated by the modeling below, the interaction of these factors creates three distinct periods in the human life span, whereby during the early adult (the reproductive period) portion of life, both the low rate of cell division and small clone sizes represent the most unfavorable conditions for sequential driver mutation accumulation.

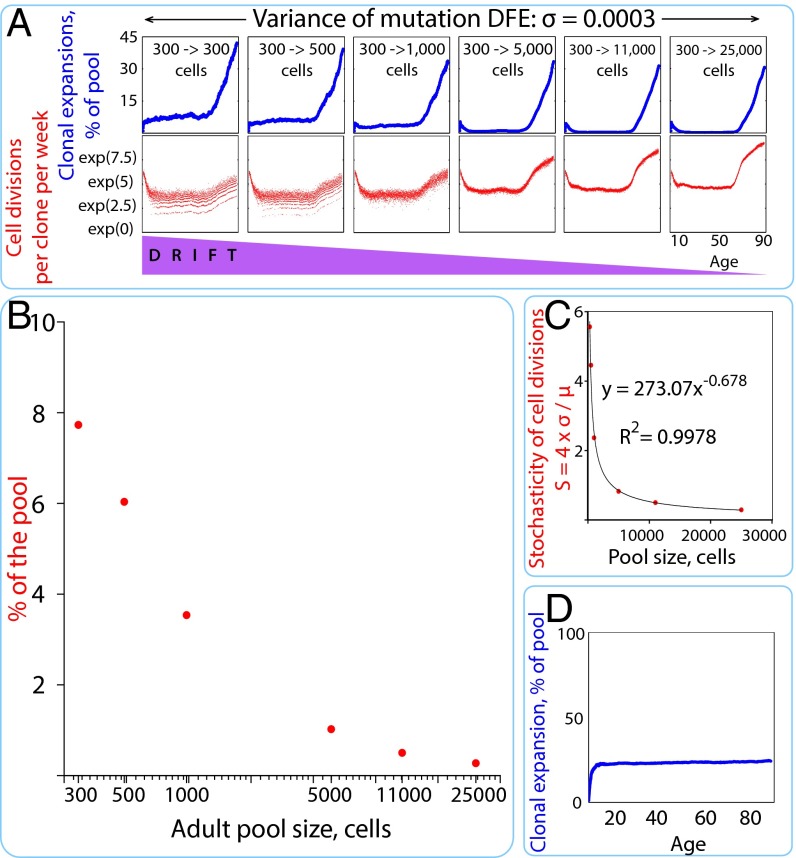

HSC pool size increases dramatically during early body growth (Fig. S2A). A clone occupying a small share of the large adult pool can have more cells, and thus more cell divisions per clone, than a clone occupying a larger share of the small early pool. However, HSCs in the adult pool will divide much more slowly than HSCs in the early pool, because the frequency of HSC divisions declines steeply starting early in life (Fig. S2A). To determine the net result of these nonlinear changes with age, we directly measured the number of cell divisions per clone in the model across a range of pool size changes (Fig. 2A). Although the greatest number of cell divisions per clone was consistently observed in late-life pools (at ∼60–90 y of age), small early pools provided for more cell divisions per clone than did larger adult pools within the reproductive portion of the life span (at ∼15–40 y of age). Thus, there exists greater opportunity for acquisition of multiple drivers within one clonal context in late life and early childhood than during the reproductive ages in between. We conclude that the age-dependent curve of somatic evolution generated by the model is informative as to the relative difference in the probability of leukemia generation in HSC pools at different ages.

Fig. 2.

Age-dependent character of somatic evolution under different adult HSC pool sizes. (A) Clonal expansions (blue) and the number of cell divisions per week for the most successful clone in the pool (red) in HSC pools of different sizes (exp, expansion). (B) Percentage of the simulated HSC pool occupied by the most successful clone in young adults (σ = 0.0003 and initial pool size = 300 cells); we measured the average expansion of the most successful clone within the reproductive period between the ages of 15 and 40 y. (C) Stochasticity (S) of the frequency of cell divisions in HSC pools of different size. μ, average division frequency; σ, SD of mean frequency of cell divisions. (D) Clonal expansions in the HSC pool under no selection (all mutations are neutral, mutation DFE variance is 0), with a modeled pool of 300 to >11,000 cells.

One of the most interesting features of the age-dependent incidence of leukemia is the decrease in incidence in young adults relative to young children (Figs. S1 and S2D). A similar pattern was observed with our simulations, but the suppression of somatic evolution in young adults notably diminished as HSC pool growth was limited (Fig. 2 A and B). Pools larger than 5,000 HSCs appeared to be largely unaffected by drift, as evidenced by greatly reduced stochasticity in cell divisions per clone (Fig. 2 A and C). Moreover, in the absence of selection (DFE σ = 0), the suppression of clonal expansions during reproductive years was lost completely (Fig. 2D). These data indicate that selection limits drift-driven clonal expansions as the HSC pool size increases as the individual approaches young adulthood. The absence of selection also led to greater early childhood clonal expansions (∼20%, compared with ∼7% for expansions with σ = 0.00003; compare Fig. 2 D and A), indicating that selection is active in early childhood pools, even if substantially weakened by drift.

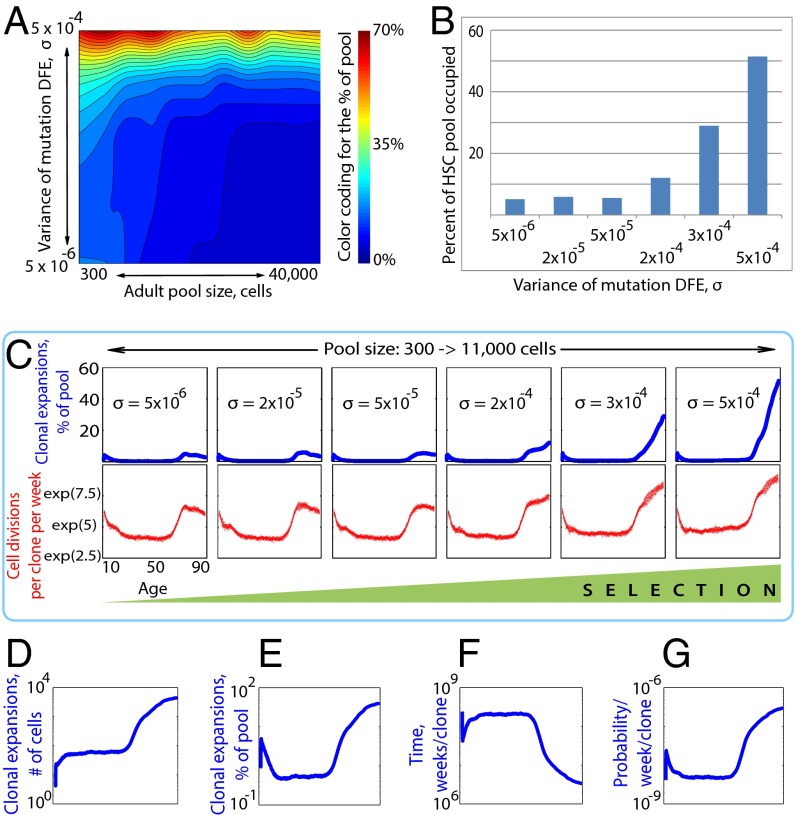

Importantly, late-life clonal expansions were absent when DFE σ = 0 (Fig. 2D), suggesting that selection dominates over drift in this age group. Indeed, late-life clonal expansions were largely insensitive to pool size (Fig. 3A), whereas both the magnitude of expansion and the number of cell divisions per clone were markedly affected by mutation DFE σ (Fig. 3 B and C). Increasing the variance of mutation DFE is significantly positively correlated with the magnitude of late life clonal expansions (Spearman ρ = 0.94, P < 0.017), with the number of cell divisions for the most successful clone increasing from ∼900 cell divisions per week to over 10,000 (Spearman ρ = 0.97, P < 0.002).

Fig. 3.

Age-dependent character of somatic evolution under different variance of mutation DFE. (A) Landscape of the maximum extent of somatic evolution (measured by the percentage of the pool occupied by the most successful clone) between the ages 30 and 87 y under a range of mutation DFE variance and pool sizes (the initial pool size is always 300 cells). (B) Maximum extent of somatic evolution (measured by the percentage of the pool occupied by the most successful clone) between the ages of 30 and 87 y under a range of mutation DFE variance and an HSC pool size of 11,000 cells. (C) Clonal expansions (blue) and the dynamics of the number of cell divisions (red) for the most successful clone in pools with an initial size of 300 cells and an adult size of 11,000 cells under a range of mutation DFE variance. (D) Age-dependent size of the most successful clone in absolute cell numbers. (E) Age-dependent size of the most successful clone as a percentage of the total pool size. (F) Time in weeks necessary to generate any given mutation within the most successful clone with a probability approaching 1. (G) The probability that any given mutation will happen within the most successful clone per week. The y axes in D–G are in natural logarithm scale. The x axes in D–G represent age from birth through the age of 95 y. Data in D–G were generated using mutation DFE variance σ = 0.0003, with a modeled pool of 300 to >11,000 cells.

To address the issue of leukemia risk more directly, we used the logic that for a sequence of mutations (e.g., A and B) to happen in one cell, it matters how fast the cells divide and how many cells make up the clonal context A. For example, if there are 100 cells early in life containing mutation A and they divide X times per week, then the likelihood of mutation B occurring in this clone will be proportional to 100 * X times the effective mutation rate. If only 10 cells containing mutation A remain later and they divide at rate 0.1 * X, then the likelihood that mutation B occurs in this clone will be proportional to 10 * 0.1 * X times the effective mutation rate, which is much smaller than early in life. Thus, if a clone “A + B” is needed to form cancer, then the likelihood of generating such a clone will be higher in the first few years of life (when cell division rates are higher and the influence of drift results in overrepresentation of some clones).

Therefore, we calculated, at various ages, the probability that any given mutation can occur within the most successful clone. This measure, for any given time T, is the product of the mutation rate per division per base pair [M, we assumed 3 × 10−9 (20)], division rate (C), and clonal size (S; number of cells): P = M × C × S, where P is the expected probability that any given mutation will happen within the most successful clone within time T. Both C and S were measured at each simulated week of life span. We also calculated, at each age, the expected time needed for any given mutation to occur within the most successful clone with probability approaching 1. Because the above probability P can also be interpreted as the frequency (F) of the occurrence of any given mutation within time T (a week), we can calculate the expected time to the next mutation as its inverse: T = 1/F = 1/P = 1/(M * C * S). Age-dependent clonal dynamics for this simulation (averaged for 100 simulated individuals) are shown in Fig. 3 D and E. Note that the absolute size of the most successful clone early in life is smaller than during adulthood (Fig. 3D), despite drift-driven clonal expansions, given the much smaller size of the overall pool (Fig. S2A). The estimated time T and probability P are shown in Fig. 3 F and G, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3 F and G, the model suggests that early adulthood is associated with a longer expected time to, and thus lower frequency of, the occurrence of the next mutation within the clone. This pattern results from the smaller clonal size and less frequent cell division during early adulthood. In contrast, the lower cell number and higher cell division frequency early in life, together with drift-driven clonal expansions, increase the probability of the next mutation occurring within a premalignant clonal context. Thus, if a preleukemic clone existing in an early HSC pool does not accumulate additional mutations needed to transform its cells into malignant cells during the early postnatal period (when cells are most actively dividing), the chances of accumulating those mutations will be low during the reproductive portion of life, providing for less frequent occurrences of leukemia. Further examples of measures in Fig. 3 F and G are provided in SI Cell Dynamics and Leukemia Risk and Table S1.

Table S1.

Sampled clonal size and cell division rates from three periods of the simulated life span

| Age, y | 2.5 | 32 | 82 |

| S, cells | 25.4 | 58.8 | 2,722.7 |

| C, divisions/cell/wk | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| M, mutations/bp/division | 3 × 10−9 | 3 × 10−9 | 3 × 10−9 |

| T, wk/clone | 8.3 × 107 | 2.1 × 108 | 5.1 × 106 |

| P, probability/wk/clone | 1.2 × 10−8 | 4.8 × 10−9 | 2 × 10−7 |

Discussion

Our modeling results suggest that somatic evolution in HSC pools is governed by different evolutionary forces throughout the human life span. Early in life, drift has a greater impact due to the smaller pool size. Clonal dynamics in larger HSC pools through early adulthood experience reduced drift and are marked by a dominant role of stabilizing selection, which suppresses somatic evolution. Then, in postreproductive ages, positive selection becomes a major force, acting on the fitness differential generated by mutation acquisition. As we have shown previously, increased positive selection in old ages is primarily driven by alterations in tissue microenvironments (20). This result is consistent with what is known from organismal populations, whereby positive selection and rapid evolution are promoted primarily by major alterations in the environment, in line with the environment-dependent nature of fitness.

A potential caveat to our modeling studies is that HSC populations could be larger than those populations modeled here, because one group estimated adult HSC pools to be roughly 20-fold greater based on multilineage repopulation assays in immunocompromised mice (18). Regardless of the true size, childhood HSC pools should be substantially smaller than those pools in adults, and thus more influenced by drift. Moreover, the number of HSCs that initiate definitive hematopoiesis during fetal development is very small (17); thus, irrespective of the HSC pool size at birth, the effective HSC pool will be of a size that is influenced by drift (at least prenatally, if not also in the postnatal period).

Our model suggests that the balance of the relative roles of drift, stabilizing, and positive selection that dictate somatic evolution in HSC pools change over a lifetime. Our results do not directly describe carcinogenesis, because carcinogenesis is just one type of somatic evolution. The model incorporates theoretical cancer driver mutations as part of all mutations possible within a cell (total mutation DFE). Clones that realized significant expansions in our simulations therefore effectively mimic high rates of both malignant and nonmalignant somatic evolution, both of which occur in HSC pools. Indeed, clonality increases exponentially in the human hematopoietic system during postreproductive ages regardless of whether or not cancer driver mutations are detected (24, 25, 27–29). These findings are consistent with our result and indicate that increased positive selection in aged tissues is a rather general pattern, irrespective of the occurrence of oncogenic mutations. Nonmalignant clonal expansions still seem to have an impact on carcinogenesis, however, because increased clonality in the hematopoietic system has, in fact, been found to associate with higher risk of leukemia (24, 25). This correlation is consistent with the argument presented in Eq. 1, in that conditions that promote significant clonal expansions elevate the probability of sequential driver acquisition, and it further supports the idea that age-dependent somatic evolution is informative in regard to cancer risk. A reservation should be made, however, that our results, just like the results in other reports (24, 25, 27–29), do not provide a direct assessment of the risk of leukemia. Instead, our results reveal factors that are likely to contribute to leukemia risk at the very early stages of premalignant somatic evolution in HSC pools, and this risk can be influenced by other factors at later stages of leukemogenesis. Many environmental factors have been proposed to modulate the risk of leukemia in children, such as the immune system and infection (30). However, the development of leukemia, as well as other cancers, critically depends on these initiating stages of nonmalignant somatic evolution that affect the chances of appearance and expansion of cellular clones containing multiple driver mutations; in this way, leukemia risk is markedly affected by the somatic evolutionary forces that operate in normal HSC pools.

Leukemia is not one disease but a class of diseases that includes a number of types based on the character of carcinogenesis (chronic or acute), the cell lineage affected (lymphoid or myeloid), and other characteristics. Although these leukemia types have different age-dependent incidence, all nonetheless exhibit an early childhood peak, except for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Fig. S1). There is evidence that the leukemia-initiating oncogenic mutations, which are distinct among the different types but always rate-limiting for subsequent stages, occur in HSCs and early multipotent progenitors (31–36). Although the HSC/multipotent progenitor origin for leukemias like acute myeloid, chronic myeloid, and chronic lymphocytic leukemias and leukemias driven by mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) translocations is better substantiated, the cell of origin for childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is less established (36). The nature of mutations occurring in HSC can also influence lineage choice during differentiation, and thus determine the nature of the eventual leukemia SC (37). Thus, the processes of somatic evolution in HSC pools should be important for providing initial rate-limiting steps for the genesis of various types of leukemia. Differences in age-dependent incidence among various leukemia types indicates that, even when initiating oncogenic events happen in HSCs, additional events key to leukemogenesis can occur in more committed hematopoietic progenitor pools. These later stages of carcinogenesis should significantly affect type-specific risk. Thus, our results are limited in their power to predict the risk of specific types of leukemia, and only describe the portion of risk that is defined by the earliest stages of somatic evolution happening at the HSC level.

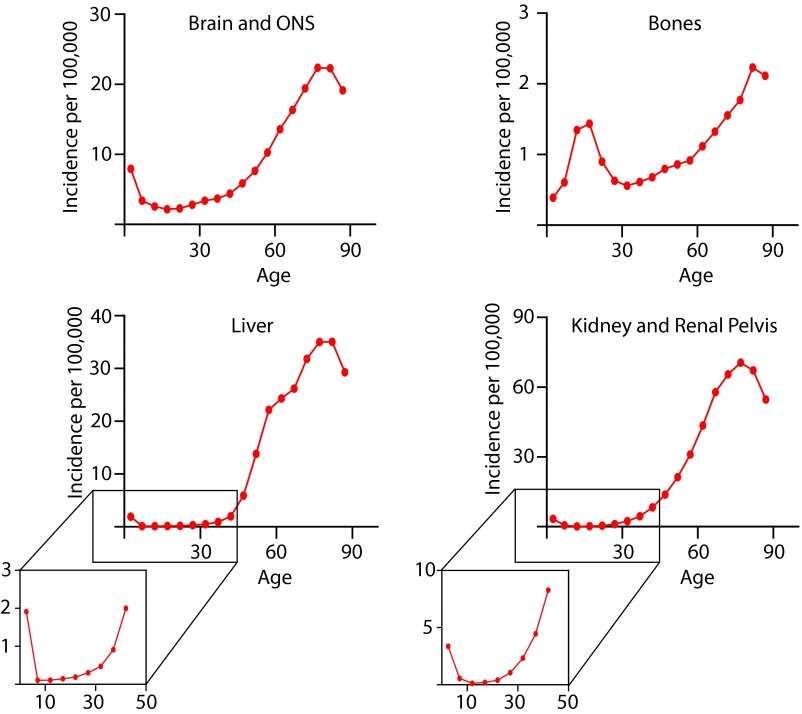

It should be noted that leukemia is not the only type of cancer that demonstrates an early childhood incidence peak. As shown in Fig. S3, a similar pattern is observed in some other cancers, such as cancers of the brain and other parts of the neural system, bone, and liver, as well as cancers of the kidney and renal pelvis. This similar incidence pattern could indicate that the SCs that give rise to these cancers show similar organization and age-dependent dynamics as HSCs, including a smaller underlying precursor pool size (increasing drift-driven expansions) with substantially higher cycling rates (increasing mutation accumulation) early in life, as well as larger and more quiescent precursor pools during adulthood. Notably, the incidence of bone cancers is shifted toward later ages, peaking around the age of 15 y, perhaps due to the fast rates of bone tissue growth (and supposedly high division rates of the underlying SCs) during this period. Still, without a better understanding of these parameters, and even the cells of origin for these cancers, it would be premature to speculate overmuch. Other explanations, such as precursor pools for these cancers that are only abundant in early childhood, are, of course, also possible.

Fig. S3.

Examples of cancers other than leukemia that demonstrate an early childhood peak. ONS, other neural system (following the SEER database designation). Data from seer.cancer.gov.

Notably, this incidence pattern, with an early childhood peak followed by low risk during reproductive years, is not apparent for carcinomas. The explanation for such a discrepancy may be in the difference of SC pool organization between epithelia and such systems as HSCs and perhaps other SCs. SCs in epithelial tissues are often clustered into small effective populations, which should expose their clonal dynamics to a high influence of drift throughout the entire life span (38). In fact, clonal dynamics of gut epithelia have been shown to be heavily drift-driven (10, 14, 15). Therefore, the relative risk of carcinomas as a function of age should not be influenced by shifts in the relative power of drift and selection over a lifetime.

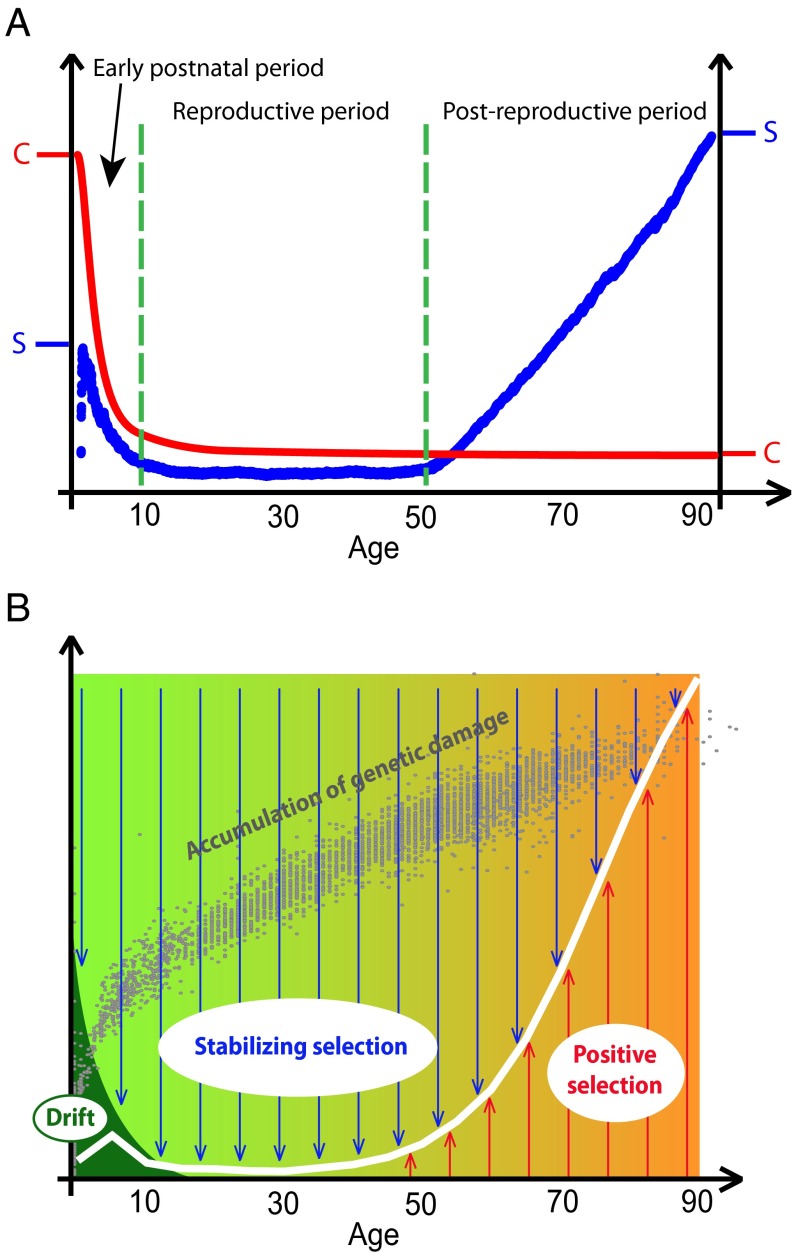

As shown in Fig. 4A, three distinct patterns of HSC division rates (C) and clonal size (S) dynamics can be seen within the human life span. The earliest postnatal period is characterized by high cell division rates and visible clonal expansions driven by drift. During the early adulthood (reproductive) period, cell division rates decrease dramatically and clonal size is suppressed by the increased stabilizing selection. Fig. 2D, which demonstrates the lack of suppression of clonal size when mutation DFE variance was set to 0, corroborates the role of selection in suppressing somatic evolution during the reproductive portion of life. The third, postreproductive period is characterized by low cell division rates but highly increased frequencies of clonal expansions driven by positive selection. This late pattern has recently been shown experimentally for the hematopoietic system in multiple studies (24–27), which is consistent with the results generated by our model. Consistent with Eq. 1, this pattern suggests that the early adulthood (reproductive) period is the most unfavorable for the appearance of cells containing multiple cancer driver mutations, in line with strong natural selection to avoid cancer during this period to maximize reproductive potential.

Fig. 4.

Model of leukemia incidence shaped by a changing age-dependent balance of drift, stabilizing selection, and positive selection. (A) Schema depicting three distinct periods in the human life span in regard to HSC cell division rates (C; red line, published data as in Fig. S2A) and clonal expansions (S; blue line, model-generated maximal clonal size as a function of age is shown as in Fig. 2A). Data are shown without preserving scale. (B) Our results suggest that early-life somatic evolutionary processes in HSCs are primarily driven by drift. In larger adult HSC pools, somatic evolution becomes suppressed by the increasing role of stabilizing selection. During late life, somatic evolution is promoted by positive selection, as the fitness differential in HSC populations builds up. The accumulation of genetic damage is based on age-dependent changes in DNA methylation (41). The background color indicates age-dependent changes in tissue microenvironment from young healthy (green) to age-degraded (yellow-orange), which is thought to be the main factor promoting positive selection (20, 42).

Based on the modeled age-dependent character of somatic evolution in HSCs, we propose that leukemogenesis is driven by different forces early and late in life. A revised model to explain age-dependent leukemia incidence is proposed in Fig. 4B. Being more dependent on selection, late-life leukemias should mostly be promoted by oncogenic mutations that confer a strong selective advantage to recipient cells in the aged tissue context. Conversely, because leukemogenesis in early childhood is more affected by drift and high cell division rates, childhood leukemias should harbor a different spectrum of drivers that may not confer an immediate selective advantage. Indeed, the frequencies of oncogenic mutations differ among leukemias from children and adults. For example, in ALL, the most common childhood leukemia, BCR-ABL translocations are rare (2–3%) among children but prevalent (25–30%) in adults (39). Conversely, the TEL-AML1 fusion (also known as ETV6-RUNX1) is found in over 25% of childhood ALLs, whereas it is detected in less than 3% of adult ALLs (39). Moreover, the presence of TEL-AML1 and AML1-ETO translocations in blood cells of newborns is ∼100-fold greater than the risk of the associated leukemias (36), consistent with the idea that early childhood leukemia may result from oncogenic mutations conferring very little, if any, selective advantage, thereby allowing them to disappear either by drift or subsequent stabilizing selection. Still, some genetic abnormalities, such as translocations involving the MLL gene, appear to be essentially sufficient on their own to cause childhood leukemia (40), which indicates that a subset of oncogenic mutations may be able to overcome the drift barrier and promote strong selection for mutant cells even in the small prenatal and early postnatal pools. Thus, the effects of drift we demonstrated in this study are likely to vary in affecting the fate of different oncogenic mutations.

It should be noted, however, that the somatic evolutionary patterns presented in this study are likely to have a greater effect on the early, initiating stages of leukemogenesis, rather than governing advanced stages. As the size of the preleukemic clone increases, the role of selection should become more dominant, particularly because the growth of the preleukemic clone will itself create a new context favoring oncogenic adaptation. Still, because initiating oncogenic events in cells are rate-limiting to subsequent stages of leukemogenesis, the age-dependent character of somatic evolution we demonstrate in this study is likely to affect the ultimate odds of the whole process. In all, our modeling studies indicate that leukemias of children and older adults are different diseases, forged by different evolutionary forces and propagated under different circumstances.

Methods

Simulations were performed using a Monte Carlo model of HSC clonal dynamics as described by Rozhok et al. (20). The model uses a simulated pool of HSCs in which cell properties, such as age-dependent division frequency and pool size increase, are defined based on published data. Initially, all cells in the pool are designated as separate clones. If a cell changes its fitness, as a result of mutation during cell division, which deviates from its predivision fitness by a certain threshold postdivision (simulating the acquisition of a functional mutation), it is assigned a new clonal status and becomes a founder of a new clone (details are provided in SI Methods). The model simulates fitness change and competition in HSC pools as a result of the effect of mutations and microenvironment on HSCs in an age-specific manner and tracks the dynamics of HSC clones over time. The model also allows for measuring cell divisions per clone, clonal size, probability of sequential mutation accumulation, waiting time until the next mutation, and multiple other somatic evolution-related parameters of interest.

Details on model architecture and parameters, as well as the MatLab code (Dataset S1), are provided in SI Methods and the study by Rozhok et al. (20).

SI Methods

Basic Model Architecture.

To elucidate how drift and selection affect somatic evolution in HSC pools across the human life span, we applied a stochastic model of HSC clonal dynamics (20) that replicates cell fate decisions and clonal evolution in HSC pools. The model is a stochastic discrete time-continuous state space model that operates with a matrix of cells (HSCs) for which cell fate decisions are made based on probability distributions over discrete increments of time. Details are described by Rozhok et al. (20). The simulated HSC pool has an age-dependent capacity (number of HSCs it can contain), which increases from birth until the age of ≈20–25 y to simulate body growth. Modeled changes in HSC pool size (Fig. S2A) with age were derived from experimental and modeling studies, with standard values of 300 HSCs at birth and 11,000 HSCs during adulthood based on these previous studies (16, 17). Both pool capacity and HSC state are updated in weekly increments, totaling 4,420 wk, to simulate a human 85-y life span. The HSC cell population grows by HSC divisions, and its maximal size is controlled by HSC competition for space to total approximately the current pool capacity. The MATLAB (MathWorks) code is provided in Dataset S1.

Outcompeted HSCs disappear from the simulated pool, reflecting their differentiation or death. On each weekly update, individual HSCs may divide, change their fitness based on mutation occurrence or microenvironmental effects (or both), stay in the pool, or leave the pool. Competition for persistence in the pool is based on cell fitness, which is initially set to 1 and changes based on the effects of mutations, epigenetic changes, and tissue microenvironment. The effects of these fitness-altering factors are drawn for each cell at each update from the respective DFEs. Cells with lower fitness have higher chances to disappear from the pool, but their fate at each weekly point is determined in a binomial trial, with a probability of staying in the pool that depends on the current number of cells after all cell divisions, pool capacity, and individual cell fitness. Initially, all cells are designated as separate clones. Over time, clones compete for the pool space based on their fitness, with more fit clones generally expanding with age.

The average frequency of HSC divisions changes with age (Fig. S2A). HSC division frequency with age was modeled using data for the dynamics of telomere shortening in leukocytes with age (43). Average age-dependent cell division frequencies ranged from once per 3 wk in early postnatal pools to their adult frequency of one division per ≈40 wk (with a 95% confidence interval of ±8 wk). Because variance in cell divisions should be proportional to the mean, based on evidence that HSC division is a Poisson process in a previous study that addressed the mathematical properties of HSC dynamics (19), we kept the mean/variance relationship throughout all ages defined as mean ± (8/40). Clonal divergence in the model is based on the magnitude of functional changes in cells, such that a cell that deviates from its predivision fitness by a certain threshold postdivision is assigned a new clonal identifier and becomes a founder of a new clone.

Parameters Used.

We have argued previously that all random genetic and epigenetic changes occurring in a cell on a per cell division basis can be assumed to have a net probability DFE on the recipient cell (20). Based on the results of this previous study, we applied a mutation DFE with 1% of mutation effects per cell division being in the positive tail (advantageous mutations), with the DFE being centered (mode) at 0 (most mutations are neutral) and heavily skewed toward the negative tail (most functional mutations decrease fitness). In experiments, in which variance of this DFE (measured as SD) was not manipulated, it was set to 0.0003. We have shown previously that within a credible range, mutation DFE variance does not have significant effects on the principal behavior of the model. However, we have shown that the effects of tissue microenvironment do have a critical effect. Therefore, in the present model, cell fitness is affected by both random cell-autonomous processes, such as mutations and epigenetic changes, and tissue microenvironment, as described by Rozhok et al. (20). For microenvironmental effects, the model assumes that the magnitude of changes in microenvironment follows with age the sigmoidal decline in fitness, which is largely delayed until postreproductive periods of life. The extent of the decline is threefold, based on measurements of HSC fitness in both humans and mice (44–46). Based on this curve of fitness decline, an equal amount of fitness is subtracted from all cells at each weekly update (independent of whether they divide); this fitness reduction is the uniform component. Given genetic and epigenetic variability in the HSC population, we then incorporate a stochastic component to the microenvironmental effects, whereby individual cell fitness is randomly changed within a distribution of effects which was negatively skewed (1% of mutations in the positive tail). The magnitude of both the uniform and stochastic component effects is age-dependent, and dictated by the speed of microenvironmental degradation.

In experiments where HSC pool sizes were not manipulated, the initial postnatal pool size was set to 300 cells, increasing with age to its adult size of 11,000 cells. In experiments where we artificially turn off selection from the pool (fixing σ at 0), we disabled both the fitness effects of random cell-autonomous processes and tissue microenvironment so that cells did not undergo any fitness changes throughout the simulated life span.

Measurements of Age-Dependent Rates of Somatic Evolution.

The rates of somatic evolution in all experiments were measured as the share of the most successful clone in the pool at each weekly update (averaged by 20 simulated life spans at each age/week). This measure allowed us to track the maximum extent of somatic evolution possible under given experimental conditions at a given age. The justification for measuring the share of the most successful clone lies in the stochastic nature of the model. Each cell changes its fitness in stochastic trials (draws from applicable DFEs) after each cell division (incorporating mutation DFE) or each weekly update (incorporating microenvironmental effects). Each clone consists of a certain number of cells at any given time, for which individual fitness determines the general success (expansion) of their clone. The most successful clones may change over time. In total, this scenario results in a pool-wise multitude of stochastic trials based on DFEs, such that the most successful clone essentially represents a high confidence value of the likelihood that high-fitness clones that are rapidly selected for can appear in the pool over time/age. Each simulation thus results in an age-dependent curve representing the share of the most successful clone at each measured age (in weeks). These curves are then averaged based on 20 simulated life spans.

SI Equation

| [S1] |

where Pd1…dn(t) is the probability of acquiring n drivers in one cell by time t, D(t) is the total number of cell divisions within a clonal context by time t, and pi is the probability of acquiring a driver di ∈ {d1, …, dn} per cell per division as a linear function of the effective mutation rate (20).

SI Cell Dynamics and Leukemia Risk

As shown in Table S1, we sampled three distinct ages as examples of the simulated clonal dynamics in relation to leukemia risk. Notations for S, M, C, T, and P are as in the explanation for Fig. 3 F and G. As shown in Table S1, the time to generate the next mutation within the most successful clone is significantly greater at the age of 32 y, compared with the ages of 2.5 and 82 y. It should be noted, however, that T is given per most successful clone; as oncogenic mutations accumulate in multiple clones, T should be shorter if measured for the entire cell pool (per individual), and the actual measures of T and P in Table S1 should be corrected for the population of 100,000 per year to reflect a measure more directly related to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database leukemia risk/incidence statistics. Also, our model only demonstrates the very initial stage when mutations (including oncogenic) accumulate in the HSC pool, and thus become rate-limiting for leukemia incidence. Further stages of carcinogenesis beyond the HSC pool are important in leukemia development, as well as other factors, such as tissue microenvironment and inflammation. Therefore, the statistics in Table S1, as well as other results in the paper, cannot be translated directly into leukemia risk and only reflect the portion of leukemia risk related to early HSC dynamics in an age-specific manner.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Porter and Craig Jordan of the University of Colorado for review of the manuscript. These studies were supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA180175), the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome, and the Leukemia Lymphoma Society (to J.D.), and by a grant from the St. Baldrick’s Foundation (to J.L.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1509333113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Armitage P. Multistage models of carcinogenesis. Environ Health Perspect. 1985;63:195–201. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8563195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194(4260):23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiter JG, Bozic I, Allen B, Chatterjee K, Nowak MA. The effect of one additional driver mutation on tumor progression. Evol Appl. 2013;6(1):34–45. doi: 10.1111/eva.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogelstein B, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillies RJ, Verduzco D, Gatenby RA. Evolutionary dynamics of carcinogenesis and why targeted therapy does not work. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(7):487–493. doi: 10.1038/nrc3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry CJ, Marusyk A, Zaberezhnyy V, Adane B, DeGregori J. Declining lymphoid progenitor fitness promotes aging-associated leukemogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(50):21713–21718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005486107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marusyk A, et al. Irradiation alters selection for oncogenic mutations in hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(18):7262–7269. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marusyk A, DeGregori J. Declining cellular fitness with age promotes cancer initiation by selecting for adaptive oncogenic mutations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marusyk A, Porter CC, Zaberezhnyy V, DeGregori J. Irradiation selects for p53-deficient hematopoietic progenitors. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(3):e1000324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeulen L, et al. Defining stem cell dynamics in models of intestinal tumor initiation. Science. 2013;342(6161):995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1243148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bondar T, Medzhitov R. p53-mediated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell competition. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(4):309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bissell MJ, Hines WC. Why don’t we get more cancer? A proposed role of the microenvironment in restraining cancer progression. Nat Med. 2011;17(3):320–329. doi: 10.1038/nm.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright S. Evolution in Mendelian Populations. Genetics. 1931;16(2):97–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/16.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snippert HJ, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143(1):134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Garcia C, Klein AM, Simons BD, Winton DJ. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science. 2010;330(6005):822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1196236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abkowitz JL, Catlin SN, McCallie MT, Guttorp P. Evidence that the number of hematopoietic stem cells per animal is conserved in mammals. Blood. 2002;100(7):2665–2667. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catlin SN, Busque L, Gale RE, Guttorp P, Abkowitz JL. The replication rate of human hematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Blood. 2011;117(17):4460–4466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JC, Doedens M, Dick JE. Primitive human hematopoietic cells are enriched in cord blood compared with adult bone marrow or mobilized peripheral blood as measured by the quantitative in vivo SCID-repopulating cell assay. Blood. 1997;89(11):3919–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abkowitz JL, Catlin SN, Guttorp P. Evidence that hematopoiesis may be a stochastic process in vivo. Nat Med. 1996;2(2):190–197. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozhok AI, Salstrom JL, DeGregori J. Stochastic modeling indicates that aging and somatic evolution in the hematopoetic system are driven by non-cell-autonomous processes. Aging (Albany, NY) 2014;6(12):1033–1048. doi: 10.18632/aging.100707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(8):610–618. doi: 10.1038/nrg2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer RA. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon; Oxford: 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldane JBS. The Causes of Evolution. Longmans, Green and Co.; London: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genovese G, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2477–2487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaiswal S, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKerrell T, et al. Understanding Society Scientific Group Leukemia-associated somatic mutations drive distinct patterns of age-related clonal hemopoiesis. Cell Reports. 2015;10(8):1239–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie M, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1472–1478. doi: 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs KB, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism and its relationship to aging and cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):651–658. doi: 10.1038/ng.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laurie CC, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism from birth to old age and its relationship to cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):642–650. doi: 10.1038/ng.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greaves M. Infection, immune responses and the aetiology of childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):193–203. doi: 10.1038/nrc1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fialkow PJ, Gartler SM, Yoshida A. Clonal origin of chronic myelocytic leukemia in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58(4):1468–1471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.4.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jan M, et al. Clonal evolution of preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells precedes human acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(149):149ra118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kikushige Y, et al. Self-renewing hematopoietic stem cell is the primary target in pathogenesis of human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(2):246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyamoto T, Weissman IL, Akashi K. AML1/ETO-expressing nonleukemic stem cells in acute myelogenous leukemia with 8;21 chromosomal translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(13):7521–7526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shlush LI, et al. HALT Pan-Leukemia Gene Panel Consortium Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014;506(7488):328–333. doi: 10.1038/nature13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greaves MF, Wiemels J. Origins of chromosome translocations in childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(9):639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrc1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stier S, Cheng T, Dombkowski D, Carlesso N, Scadden DT. Notch1 activation increases hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in vivo and favors lymphoid over myeloid lineage outcome. Blood. 2002;99(7):2369–2378. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozhok AI, DeGregori J. Toward an evolutionary model of cancer: Considering the mechanisms that govern the fate of somatic mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(29):8914–8921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501713112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greaves M. When one mutation is all it takes. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):433–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorban AN, Pokidysheva LI, Smirnova EV, Tyukina TA. Law of the Minimum paradoxes. Bull Math Biol. 2011;73(9):2013–2044. doi: 10.1007/s11538-010-9597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sidorov I, Kimura M, Yashin A., Aviv A Leukocyte telomere dynamics and human hematopoietic stem cell kinetics during somatic growth. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(4):514–524. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dykstra B, Olthof S, Schreuder J, Ritsema M, de Haan G. Clonal analysis reveals multiple functional defects of aged murine hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2691–2703. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pang WW, et al. Human bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells are increased in frequency and myeloid-biased with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(50):20012–20017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116110108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossi DJ, et al. Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(26):9194–9199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503280102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2013) Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368(22):2059–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.