Abstract

Objectives

Progression-free survival (PFS) has not been validated as a surrogate endpoint for overall survival (OS) for anthracycline (A) and taxane-based (T) chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer (ABC). Using trial-level, meta-analytic approaches, we evaluated PFS as a surrogate endpoint.

Methods

A literature review identified randomized, controlled A and T trials for ABC. Progression-based endpoints were classified by prospective definitions. Treatment effects were derived as hazard ratios for PFS (HRPFS) and OS (HROS). Kappa statistic assessed overall agreement. A fixed-effects regression model was used to predict HROS from observed HRPFS. Cross-validation was performed. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were performed for PFS definition, year of last patient recruitment, line of treatment, and constant rate assumption.

Results

Sixteen A and fifteen T trials met inclusion criteria, producing seventeen A (n = 4,323) and seventeen T (n = 5,893) trial-arm pairs. Agreement (kappa statistic) between the direction of HROS and HRPFS was 0.71 for A (p = .0029) and 0.75 for T (p = .0028). While HRPFS was a statistically significant predictor of HROS for both A (p = .0019) and T (p = .012), the explained variances were 0.49 (A) and 0.35 (T). In cross-validation, 97 percent of the 95 percent prediction intervals crossed the equivalence line, and the direction of predicted HROS agreed with observed HROS in 82 percent (A) and 76 percent (T). Results were robust in sensitivity and subgroup analyses.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggests that the trial-level treatment effect on PFS is significantly associated with the trial-level treatment effect on OS. However, prediction of OS based on PFS is surrounded with uncertainty.

Keywords: Progression-free survival, Surrogate endpoint, Meta-analytic validation, Advanced breast cancer, Overall survival

Surrogate endpoints are attractive in clinical trials when the primary endpoint is difficult to measure because of time, costs, the need to test multiple regimens, ethical considerations, or pressure from patient advocacy groups (27;41). In advanced breast cancer, prolongation of survival and symptom improvement are commonly accepted as evidence of clinical benefit and as appropriate primary endpoints (27;65). However, a validated surrogate endpoint allows for inferences about a treatment’s benefit when primary endpoint data are not available (6;7;26). One potential surrogate endpoint for overall survival (OS) in advanced breast cancer is progression-free survival (PFS), a composite endpoint defined by the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the time from randomization to documented progression or death from any cause (25;65). However, the association between PFS and OS has not been systematically evaluated in advanced breast cancer for anthracycline and taxane-based chemotherapy.

PFS includes death as part of its composite endpoint— and, therefore, differs from other progression-based endpoints. For example, time to progression is defined by the U.S. FDA as the time from randomization until tumor progression (death is censored), and time to treatment failure is a composite endpoint defined as the time from randomization until the patient stops the trial treatment for any reason including progression, toxicity, or preference (death is censored) (25;65). The inclusion of death in PFS may be important in advanced breast cancer because tumor growth, whether or not it is documented, usually precedes death. In other words, background mortality contributes relatively little to the 2-year median survival for advanced breast cancer and death likely reflects the treatment’s ability, or lack thereof, to control disease progression (30;64;65). Therefore, censored deaths may constitute informative censoring and may impact the ability of other progression-based endpoints to predict OS. Because PFS uniquely overcomes this limitation by including death, its ability to predict OS should be evaluated separately from other progression-based endpoints.

PFS has additional benefits as an endpoint because it is measured before postprogression treatments are initiated. Therefore, PFS data is not affected by postprotocol agents. Furthermore, PFS is measured earlier and has a higher event frequency compared to OS. Consequently, PFS results may be available sooner and, potentially, with smaller and less costly trials (2;22;33).

However, PFS has several potential limitations that it shares with all progression-based endpoints. The need for frequent radiologic studies raises the potential for assessment bias and increases the complexity of data capture and validation (25;65). PFS may be sensitive to differences in the duration between assessments (25;47), unprotocolled assessments (25;47), variations in censoring (25;46), and the use of cytostatic agents (67). Furthermore, variability in PFS measurement may be magnified when it is used to predict OS (20;26). With multiple effective therapies available for advanced breast cancer, the link between PFS and OS may be distorted by nonprotocolled treatments given after the trial regimen (19;22;33).

Although PFS has not been systematically evaluated in advanced breast cancer for anthracyclineand taxane-based chemotherapy, studies suggest that time to progression and response rate have a statistically significant association with OS (1;33). However, only 34 to 37 percent of OS variability was explained by variability in time to progression and response rate, respectively (1;33). An abstract suggested a similar result (R2 = .44) for PFS for trials comparing taxane and anthracycline chemotherapy (13). However, cross-validation was not performed for this narrowly defined set of trials. Although there is controversy about the optimal approach for validating surrogate endpoints (12;15;42), one option is to evaluate performance at the trial level (33).

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the association between the direction and magnitude of the treatment effect on PFS compared with the treatment effect on OS for anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapy regimens in advanced breast cancer using a trial-based, meta-analytic approach. We limited our analysis (and the generalization of our results) to anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer because the relationship between PFS and OS may differ for different anti-cancer agents and in different cancers due to underlying biologic factors, the interaction of each anti-cancer agent with each cancer, and differences in the availability of active subsequent line treatments (26).

METHODS

Literature Search, Inclusion Criteria, and Data Abstraction

A systematic literature search in Medline (January 2007) based on published search strategies (32;33) was performed to identify English-language publications of randomized controlled advanced breast cancer trials of anthracycline-based (5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide [FEC]; and 5-fluorouracil, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide [FAC]) or taxane-based (any combination) chemotherapy. Abstract databases for the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium annual meetings were also searched.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) PFS data and OS endpoint data reported; (ii) evidence of adequate randomization and blinding; (iii) 80 percent of the sample with advanced breast cancer; (iv) at least one trial regimen included anthracycline- (FEC/FAC) or taxane-based chemotherapy (33). To maximize inclusion, all publications reporting any progression-based data were reviewed and endpoints were classified according to U.S. FDA definitions. Any publication reporting a progression-based endpoint that met the “strict” U.S. FDA definition of PFS (time from randomization to progression or death from any cause) (25;65) was included in the analysis, even if terminology in the publication differed.

Publications using PFS terminology but not providing a definition of the progression-based endpoint were included if there was no evidence of deviation from the U.S. FDA definition after careful review of the entire the publication. These trials were excluded from subgroup analysis of trials meeting the “strict” definition of PFS. Those trials whose endpoint consisted of both progression and death but had a minor deviation from the U.S. FDA definition were included in the primary analysis but excluded from the subgroup of trials meeting the “strict” PFS definition.

Classification of progression-based endpoints and data extraction was independently performed by at least two authors. All discrepancies were refereed by two authors (R.M., U.S.). The extracted data were: (i) definition of progressionbased endpoint; (ii) deviation from prospectively defined PFS definition; (iii) treatment regimen in each arm; (iv) median OS and PFS for each arm; (v) number of patients used to calculate PFS; (vi) year the last patient was recruited; (vii) line of trial treatment; (viii) published hazard ratios; and (ix) description of censoring technique(s) and therapies received subsequent to trial protocol. For trials with multiple publications, data from the longest follow-up period was used.

Statistical Methods

Calculation of Hazard Ratios

The hazard ratio (HR) for the treatment effect on OS (HROS) and on PFS (HRPFS) was estimated by calculating the median OS and PFS ratios for each pair of trials arms. An exponential distribution was assumed for the survival function. The trial arm containing the chemotherapy of interest (anthracycline or taxane) was designated as Group 2 for that analysis: HROS = Median OS of Group 1 / Median OS of Group 2 (Table 1). If a trial compared two different regimens for the chemotherapy of interest, the treatment arm most similar to the current U.S. FDA approved regimen was designated as Group 2. For trials with multiple arms, each pair of arms was evaluated and included in the analysis. The anthracycline and taxane trials were evaluated separately.

Table 1.

Anthracycline (FEC/FAC) and Taxane-Based Chemotherapy Trials Included in Analysis

| Author (year published) |

Year last subject enrolled |

Number of Subjects Randomized |

Calculated HROS |

Calculated HRpfs |

Progression endpoint terminology in publication |

Definition of progression endpoint in publication (Differences in bold) |

Predicted HR |

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Leave one out analysis | ||||||||||

| Anthracyclines (FEC/FAC) | ||||||||||

| A | Perry(51) (1987) | 1982 | 451 | 1.04 | 1.20 | TTF | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.10 | 0.78 | 1.55 |

| B | Boccardo(11) (1985) | 1982 | 73 | 1.70 | 1.62 | PFS | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.24 | 0.91 | 1.70 |

| C | Bennett(8) (1988) | 1985 | 331 | 0.98 | 0.83 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.91 | 0.63 | 1.31 |

| D | Conte(17) (1987) | 1985 | 116 | 1.27 | 1.04 | PFS | No definition provided | 1.02 | 0.73 | 1.43 |

| E | Aisner (I)(3) (1995) | 1987 | 335 | 1.16 | 1.03 | TTF | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.01 | 0.72 | 1.44 |

| F | Aisner (II)(3) (1995) | 1987 | 329 | 1.17 | 1.08 | TTF | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.04 | 0.73 | 1.47 |

| G | Ejlertsen(24) (1993) | 1989 | 359 | 1.28 | 1.40 | PFS | No definition provided | 1.17 | 0.80 | 1.71 |

| H | Speyer(61) (1992) | 1989 | 150 | 1.10 | 1.07 | PFS | No definition provided | 1.04 | 0.73 | 1.47 |

| I | Conte(18) (1996) | 1990 | 258 | 1.16 | 1.17 | PFS | No definition provided | 1.08 | 0.76 | 1.54 |

| J | Ackland(2) (2001) | 1992 | 460 | 0.91 | 0.71 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.82 | 0.55 | 1.21 |

| K | Sledge(59) (2000) | 1992 | 227 | 0.98 | 1.31 | TTF | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.63 |

| L | Pierga(52; 53) (1995, 1998) |

1993 | 258 | 0.91 | 0.86 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.93 | 0.65 | 1.33 |

| M | Parnes(50) (2003) | 1995 | 241 | 0.99 | 1.05 | TTF | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.03 | 0.73 | 1.45 |

| N | Namer(45) (2001) | 1995 | 280 | 0.85 | 1.00 | PFS | No definition provided | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.38 |

| O | Del Mastro(21) (2001) | 1997 | 151 | 0.83 | 0.90 | TTF | No definition provided | 0.95 | 0.68 | 1.32 |

| P | Jassem(34; 35) (2004, 2001) |

1998 | 267 | 1.26 | 1.31 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.14 | 0.79 | 1.63 |

| Q | Zielinski(68) (2005) | 2002 | 259 | 1.18 | 1.01 | Time to Progressive. Disease |

Difference from strict PFS definition: All

deaths included if evidence of progression during treatment period or if clinical diagnosis/post-mortem examination indicated that death related to study drug or breast cancer. |

1.01 | 0.71 | 1.42 |

| Taxanes | ||||||||||

| R | Nabholtz(43) (1996) | 1992 | 471 | 0.90 | 0.71 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.92 | 0.68 | 1.23 |

| S | Sledge (I)(58) (2003) | 1995 | 487 | 0.85 | 0.95 | TTF | Difference from strict PFS definition: All

death included if due to progression, toxicity or breast cancer within 6 weeks of date last known to be alive with stable disease. |

0.99 | 0.75 | 1.31 |

| T | Sledge (II)(58) (2003) | 1995 | 489 | 0.85 | 0.73 | TTF | As above | 0.92 | 0.69 | 1.24 |

| U | Paridaens(48) (2000) | 1996 | 331 | 1.17 | 1.92 | PFS | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.18 | 0.83 | 1.68 |

| V | Smith(60) (1999) | 1996 | 563 | 1.04 | 1.14 | Event Free Survival |

Fits strict PFS definition | 1.03 | 0.77 | 1.39 |

| W | Winer (I)(66) (2004) | >1996 | 314 | 1.09 | 1.05 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.01 | 0.76 | 1.35 |

| X | Winer (II)(66) (2004) | >1996 | 313 | 1.27 | 1.26 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.05 | 0.81 | 1.37 |

| Y | Chan(16) (1999) | 1997 | 326 | 0.93 | 0.81 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.95 | 0.71 | 1.27 |

| Z | Nabholtz(44) (1999) | 1997 | 392 | 0.76 | 0.58 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.89 | 0.65 | 1.20 |

| AA | Sjostrom(57) (1999) | 1997 | 282 | 1.06 | 0.48 | TTP | Difference from strict PFS definition: PFS measured until progression, death or last follow-up visit. |

0.76 | 0.58 | 1.01 |

| BB | Bishop(10) (1999) | 1997 | 209 | 0.80 | 1.21 | PFS | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.06 | 0.81 | 1.38 |

| CC | Jassem(34;35) (2001,2004) |

1998 | 267 | 0.80 | 0.77 | TTP | Fits strict PFS definition | 0.94 | 0.71 | 1.24 |

| DD | Biganzoli(9) (2002) | 1999 | 275 | 1.00 | 1.00 | PFS | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.34 |

| EE | Langley(38) (2005) | 1999 | 705 | 1.08 | 1.01 | PFS | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.34 |

| FF | Jones(36) (2005) | 2001 | 449 | 0.82 | 0.63 | TTP | Difference from strict PFS definition: All

deaths included if occurred less than 6 months after last study drug dose. |

0.89 | 0.66 | 1.21 |

| GG | Zielinski(68) (2005) | 2002 | 259 | 0.84 | 0.99 | Time to Progressive Disease |

Difference from strict PFS definition. All

deaths included if evidence of progression during treatment period or if clinical diagnosis/post-mortem examination indicated that death related to study drug or breast cancer. |

1.00 | 0.75 | 1.32 |

| HH | Gennari(31) (2006) | 2002 | 215 | 1.04 | 1.13 | PFS | Fits strict PFS definition | 1.03 | 0.77 | 1.38 |

Note. Data extracted during literature review, assessment of progression-based endpoint definition and calculation of hazard ratio (HR) based on published data. Standardized definitions: PFS, progression free survival, time from randomization to progression or death from any cause; TTP, time to disease progression, time from randomization to progression; OS, overall survival, time from randomization until death from any cause; TTF, time to treatment failure, time from randomization to treatment failure for any cause; HR, hazard ratio; I, first trial-arm pair from study; II, second trial-arm pair from study.

Agreement in Direction of PFS and OS Treatment Effects

For both anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapy trials, the level of agreement (kappa coefficient) between the direction of the HRPFS and HROS was calculated along with a p value. Kappa tests the null hypothesis that there is no more agreement between HRs than might occur by chance alone (4;37).

Prediction of the Magnitude of the Treatment Effect on OS

The explanatory power of the trial-level treatment effect on PFS for the trial-level treatment effect on OS was evaluated using a meta-analytic, fixedeffects weighted linear regression model: log10(HROS) = α + β*log10(HRPFS). The intercept term α was included to avoid spurious associations from forcing the regression through the origin and to facilitate comparison with prior studies (33). Each trial arm pair was weighted by the total number of patients assessed for PFS (usually the intent to treat population). For trials with multiple arms, each arm was downweighted (downweighting factor = number of independent trial arm pairs/number of total trial arm pairs) to adjust for multiple comparisons. The coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated for each model to measure the proportion of variability in HROS explained by variability in HRPFS.

Leave-one-out cross-validation

The validity of the regression model was tested using leave-one-out crossvalidation. The regression model was re-fitted with the Nth trial arm pair excluded. For each excluded trial arm pair, the observed HRPFS was used in the refitted regression equation to calculate the predicted HROS and 95 percent prediction interval (5;23). This process was repeated for every trial and each predicted HROS was compared with the respective observed HROS.

Sensitivity Analyses and Subgroup Analyses

The robustness of the regression model was assessed by evaluating key parameters in repeat analyses: (i) when available, the published HR was substituted for the calculated HR; and (ii) only those trials explicitly meeting the strictest definition of PFS were evaluated.

The potential impact of therapies given after the trial regimen was assessed using two proxy measures: year of last patient entry (before versus after 1990) and line of trial therapy (first versus subsequent-line). These proxies were chosen because the numbers of active treatment options available after progression tend to be greater after first-line protocols and after 1990 (33). The regression model was refitted with an interaction term between HRPFS and an indicator variable for the respective proxy.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). A two-sided p value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Literature Search and Description of Included Studies

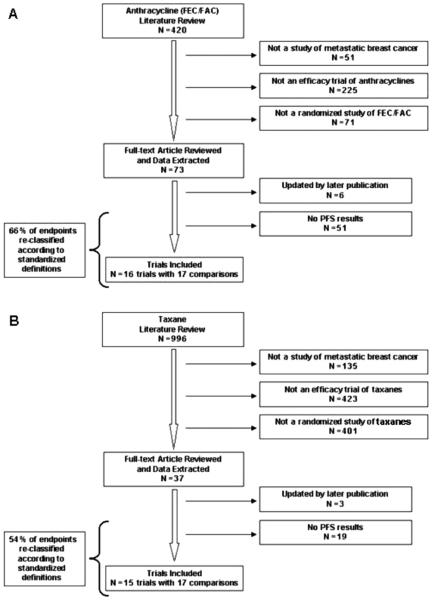

We identified 420 individual publications of anthracyclinebased (FEC/FAC) and 996 of taxane-based trials for advanced breast cancer (Figure 1). Seventy-three anthracycline and thirty-seven taxane publications reported a progressionbased endpoint and met other inclusion criteria. These publications were reviewed to identify trials with PFS data as defined by the U.S. FDA. Six anthracycline and three taxane publications were excluded because the trial was updated with a later publication included in the review. Forty-two percent (31/73) anthracycline and 30 percent (11/37) taxane publications did not provide a detailed description of how the progression-based endpoint was determined: of these publications 6 anthracycline and no taxane trial arm pairs reported PFS data for which scrutiny of the methods and results did not reveal obvious deviations from the U.S. FDA definition of PFS. (11;17;18;24;45;61) The majority of these publications (4/6) were published in 1990 or earlier. These six trials were excluded in a sensitivity analysis of trials meeting the “strict” definition of PFS.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review for anthracycline (A) and taxane-based chemotherapy (B) for advanced breast cancer. Results of systematic review of the literature. FEC, 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide; FAC, 5-fluorouracil, adriamycin and cyclophosphamide; N = number.

Of those publications providing a definition of the progression-based endpoint, 66 percent (28/42) of the anthracycline and 54 percent (14/26) of the taxane publications did not have a description consistent with U.S. FDA definitions and terminology. These publications were reclassified according to U.S. FDA endpoint definitions. The majority of re-classifications occurred from time to progression to PFS and from time to treatment failure to time to progression. The most common reason for exclusion from this analysis was that the endpoint did not include all causes of death and, therefore, did not meet the definition of PFS.

To maximize the number of studies in the analysis, four trials were included that reported a composite progressionbased endpoint of death and progression but differed from the strict PFS definition in the following ways: (i) all deaths were included except those occurring after a predefined time interval from date of last study treatment (36;58;68); (ii) all deaths were included except those not attributed to study drug or breast cancer (58;68); and (iii) the last follow-up visit was defined as a PFS event (57). These four trials were excluded in a sensitivity analysis of trials meeting the “strict” definition of PFS.

Ultimately, sixteen anthracycline and fifteen taxane trials reported PFS data and met the other inclusion criteria (Table 1). All included anthracycline trials evaluated firstline therapy and 53 percent (9/17) recruited the last patient after 1990. A total of seventeen trial-arm pairs (n = 4,323) were available to evaluate HROS and HRPFS for anthracycline regimens. All included taxane trials recruited the last patient after 1990 and 47 percent (8/17) were second/subsequentline regimens. A total of 17 trial-arm pairs (n = 5,893) were available to evaluate HROS and HRPFS for taxane regimens. The majority of trial-arm pairs exactly met the U.S. FDA (strict) definition of PFS: 59 percent (10/17) of anthracycline (FEC/FAC) and 71 percent (12/17) of taxane trial arm pairs.

Information about censoring techniques was presented for less than half of the trial arm pairs: 41 percent (7/17) of anthracycline (FEC/FAC) and 35 percent (6/17) of taxane trial arm pairs. Details about subsequent treatments were provided in 41 percent (7/17) of anthracycline and 53 percent (9/17) of taxane trial arm pairs. An HR estimate for OS and PFS was published for 12 percent (2/17) of anthracycline (2;35) and 35 percent (6/17) of taxane trial arm pairs (9;16;35;36;38;48).

Agreement in Direction of PFS and OS Treatment Effects

For both regimens, there was good agreement between the direction of PFS and OS (Table 2). The kappa statistic for the anthracycline trial arm pairs was 0.71 (95 percent confidence interval (CI), 0.36–1.00; p = .0029) and was 0.75 (95 percent CI, 0.42–1.00; p = .0028) for taxane trial arm pairs.

Table 2.

Agreement in Direction of the Hazard Ratios (HR) for Progression Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS)

| Number of trial-arm pairs (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| HROS <1 | HROS >1 | Total | |

| Anthracyclines (FEC/FAC) | |||

| HRPFS <1 | 4 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (25%) |

| HRPFS >1 | 2 (12.5%) | 10 (62.5%) | 12 (75%) |

| Total (%) | 6 (37.5%) | 10 (62.5%) | 16 (100%) |

| Taxanes | |||

| HRPFS <1 | 8 (50%) | 1 (6.35%) | 9 (56.25%) |

| HRPFS >1 | 1 (6.25%) | 6 (37.5%) | 7 (43.75%) |

| Total (%) | 9 (56.25%) | 7 (43.75%) | 16 (100%) |

Prediction of the Magnitude of the Treatment Effect on OS

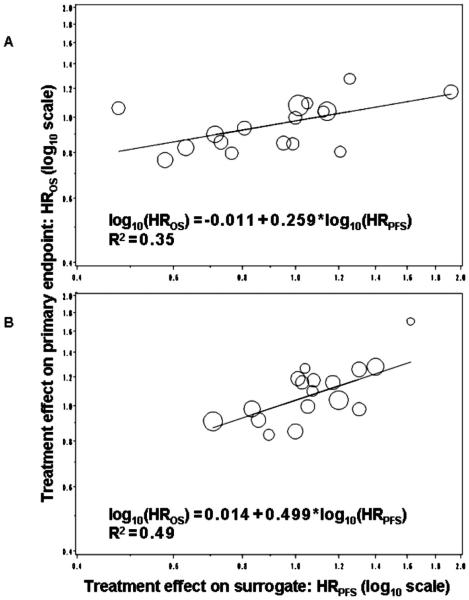

In the primary meta-analytic, fixed-effects regression analysis of anthracycline-based (FEC/FAC) chemotherapy, HRPFS was a significant predictor for HROS (p = .0019), with an explained variance (R2) of .49 (Table 3 and Figure 2). Similarly, HRPFS was a significant predictor for HROS (p = .012) for taxane-based chemotherapy with an R2 of .35. Elimination of a potential outlier (11) did not change results.

Table 3.

Results for Meta-analytic, Fixed-Effects Regression Analysis: Primary Model, Sensitivity Analysis, and Subgroup Analysis

| Model | Trial-arm pairs (N) |

Model R2 |

p value for HRPFS

as a predictor HROS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracyclines (FEC/FAC) | |||

| Primary model | 17 | .48 | .002 |

| Sensitivity analysis: Strict PFS definition | 10 | .46 | .032 |

| Sensitivity analysis: Published HR substituted (n = 2) | 17 | .56 | .0005 |

| Sub-group analysis: Interaction term for year last patient recruited | 17 | .51 | .009 (interaction p value = .44) |

| Sub-group analysis:Last patient recruited > 1990 | 8 | .34 | .127 |

| Sub-group Analysis:Last patient recruited <1990 | 9 | .51 | .030 |

| Taxanes | |||

| Primary model | 17 | .35 | .0120 |

| Sensitivity Analysis: Strict PFS definition | 12 | .59 | .0036 |

| Sensitivity analysis:Published HR substituted (n = 6) | 17 | .25 | .040 |

| Subgroup analysis:Interaction term for first line trial | 17 | .36 | .095 (interaction p value = .60) |

| Subgroup analysis: First-line trial | 8 | .61 | .022 |

| Subgroup analysis: Second/subsequent-line trial | 9 | .48 | .038 |

Note. Results of meta-analytic regression analysis, with regression model: log10 HR (OS) = α +β *log 10 HR (PFS). HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; log, logarithm; FEC, 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide; FAC, 5-fluorouracil, adriamycin and cyclophosphamide.

Figure 2.

Primary meta-analytic, fixed-effects regression model for anthracycline (A) and taxane-based chemotherapy (B). Primary, fixed-effects meta-analytic regression analysis assessing the association of HRPFS and HROS. Size of circle indicates relative sample size of each trial-arm pair. Regression equation noted in figure, along with R2 value. HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; log, logarithm.

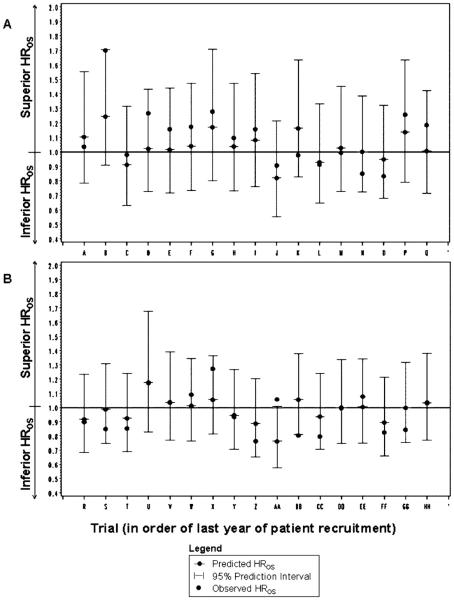

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation

All 95 percent prediction intervals for the predicted HROS based on the observed HRPFS were wide and all but one in the taxane analysis crossed the equivalence (HROS = 1) line (Figure 3). All observed HROS fell within the 95 percent prediction intervals for the anthracyclines (FEC/FAC) trial arm pairs, and 88 percent (15/17) did so for the taxane trial arm pairs. However, the observed and predicted HROS fell on the opposite side of the equivalence (HROS = 1) line for 18 percent (3/17) of anthracycline and 24 percent (4/17) of taxane trial-arm pairs. The majority of the predicted HROS were closer to the equivalence line than the observed HROS:82 percent (14/17) of taxane and 71 percent (12/17) of anthracycline trial-arm pairs.

Figure 3.

Leave-one-out cross-validation: anthracycline- (A) and taxane-based chemotherapy (B). Observed HROS for each trial-arm pair is plotted against the predicted HROS and 95% prediction intervals calculated from the HRPFS in the primary meta-analytic, fixed-effects regression model. HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival.

Sensitivity Analyses and Subgroup Analyses

When two available published HR values for the anthracyclines were substituted for calculated HRs, the primary model R2 increased to .56 and HRPFS remained significant (p = .0005) (Table 3). In contrast, when six available published HR values for taxane trial-arm pairs were substituted, the R2 decreased to .25 and the HRPFS remained significant (p = .040).

To assess the impact of adhering to a strict definition of PFS based on information in the publication, the analysis was repeated after excluding those trial arm pairs that did not provide a definition of PFS or deviated from the strict PFS definition. PFS remained significant in both models, although the R2 decreased to .46 (p = .032) for anthracyclines and increased to .59 for taxanes (p = .0036) (Table 3).

Analysis of the potential impact of subsequent-line treatments for anthracyclines showed a nonsignificant interaction (p = .44) between HRPFS and year of last patient recruitment (before versus after 1990) (Table 3). The anthracycline subgroup of trials recruiting patients after 1990 had a lower R2 (.34) than the primary model and HRPFS was not statistically significant (p = .13). However, the anthracycline subgroup of trials recruiting the last patient before 1990 was similar to the primary model (R2 = .51), and HRPFS remained statistically significant (p = .03).

Similarly, there was a statistically nonsignificant interaction between line of trial treatment and HRPFS for taxanes (p = .60). However, PFS remained a significant predictor in each taxane subgroup (p = .022 and .038 for eight first-line and nine subsequent-line trials, respectively). Each taxane subgroup model had a higher R2 than the primary model: .61 and .48 for first-line and subsequent-line, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Based on our meta-analytic evaluation of anthracycline(FEC/FAC) and taxane-based chemotherapy trials in advanced breast cancer, there is a statistically significant association between both the direction and the magnitude of the trial-level treatment effect on PFS and the trial-level treatment effect on OS. However, prediction of OS based on PFS is surrounded with uncertainty. Although the direction of the observed HRPFS and the observed HROS showed good agreement by the kappa statistic (4), 18 percent (anthracyclines) to 24 percent (taxanes) of the predicted HROS fell on the opposite side of the equivalence line compared with the observed HROS (i.e., the converse conclusion with respect to which regimen is superior). All of the 95 percent prediction intervals were wide and the majority crossed the HR equivalence line. Approximately half (anthracycline) to one-third (taxanes) of the variance in the treatment effect on OS is explained by the variance in the treatment effect on PFS. In light of our results, the finding of a significant PFS but an insignificant OS in a recent large advanced breast cancer trial (39) published after the conclusion of our study is not unexpected.

The results of this study were robust in cross-validation as well as in sensitivity analyses. Using limited data, heterogeneity of results could not be explained by the constant rate assumption, differences in PFS definition, year of last patient recruitment, or line of therapy. However, exploratory subgroup analyses indicated that PFS may perform better for anthracycline trials that recruited the last patient before 1990 and for taxanes trials stratified by line of treatment.

This study adds to and expands prior work on surrogate endpoint validation (1;13;33). We (i) systematically classified all published trial-level progression-based endpoints of anthracycline- and taxane-based (FEC/FAC) advanced breast cancer trials according to U.S. FDA and EMEA definitions; (ii) assessed trial-level PFS as a surrogate for taxane-based chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer using meta-analytic, trial-level regression analysis techniques; and (iii) evaluated trial-level PFS for taxane and anthracycline trials with leave-one-out crossvalidation and sensitivity analyses. We extended prior work on trial-level PFS for anthracycline-based (FEC/FAC) chemotherapy (33) by including additional trials, verifying endpoint definitions and performing cross-validation. We also enhanced the generalizability of prior work using individual level data (14) by not limiting our evaluation to those trials with this type of data available. The R2 findings of this study for PFS are consistent with prior studies of other progression-based surrogate endpoints in advanced breast cancer, including the recent individual level analysis with fewer trials (1;13;14;33). We extended the prior work by performing a cross-validation to assess the robustness of the results. Our findings for PFS as a surrogate endpoint differ from those found for colon cancer, suggesting that different diseases, and, perhaps, different agent types, need separate evaluation (54;55;62). Future work on surrogate endpoints for different types of chemotherapy agents and different types of cancers may further elucidate the factors influencing the relationship of PFS and OS.

This study also highlights the variability in terminology and definition for progression-based endpoints such as PFS. Although most of the trials without a definition of PFS were published in 1990 or earlier, half of the trials with minor deviations from the U.S. FDA definition were published after 2000. While unique logistical and biologic considerations (and pretrial discussions with regulatory agencies) may have led to the definition choice, we believe it is important that the health-services research and clinical community be aware that these differences exist.

Our study must be considered within the context of its limitations. To focus on PFS as a unique endpoint differing from other progression-based endpoints, only a modest number of trials met eligibility criteria and power was limited. A systematic review of the published literature and abstract databases was performed to maximize the number of eligible trials and to minimize potential publication bias. In addition, publications of all trials with progression-based endpoints were reviewed to determine whether the endpoint met the U.S. FDA definition of PFS, even if this terminology was not used in the publication. Although individual level data were not available and we used median survival and PFS values, we followed the work of Parmer et al. to develop hazard ratios based on summary statistics (49). A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the potential limitation of using calculated HRs.

Variability in the definition of and the use of progressionbased endpoints in the original trials may have introduced heterogeneity into our analysis. To limit potential heterogeneity, each trial was classified according to the U.S. FDA definitions, which were prospectively established. A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether exclusion of trials with differences from the strict definition of PFS changed results. Because some trials did not publish PFS data, the number of trials eligible for inclusion in this triallevel analysis was limited. Although great care was taken to include only trials with PFS data, it was impossible to discern if evaluation for disease progression occurred at similar time points for each arm of the trial. Therefore, variability in evaluation schedules between arms may have altered the observed PFS treatment differences. Insufficient data limited analysis of the impact of censoring, the radiologic standard used to determine progression, and follow-up periods: If the true PFS and OS length was not reached due to short follow-up, the predictive value of PFS may be underestimated. Finally, PFS is not the only potential composite endpoint for breast cancer. In contrast to PFS, other composite endpoints such as QTWiST give differential weights to fatal and nonfatal endpoints and may have a different relationship to OS (28;29).

Some authors argue that the association between PFS and OS may be underestimated because of numerous subsequent-line therapies and cross-over from the control arm to active treatment (56). Nonrandomized use of secondline agents may alter the relationship between PFS and OS by distorting the causal pathway between the intervention and the primary endpoint. If the use of subsequent-line treatments is random with respect to PFS (nondifferential bias), the performance of PFS as a surrogate may be diminished. However, if the use of subsequent-line treatments is not random with respect to PFS or is protocolled conditional on PFS (differential bias), then the relationship between PFS and OS reflects the entire treatment strategy and the potential bias may be in either direction. Therefore, it is possible that differences in the predictive ability of HRPFS are due to differences in the impact of subsequent therapies. Because most trial publications did not directly report the use of subsequent line or cross-over therapies, we used proxy variables for the availability of subsequent-line therapies to explore this issue.

Although prediction of OS from PFS was surrounded by uncertainty, PFS is a statistically significant predictor in our trial-based meta-analytic regression model and progression is also a biologically plausible precursor to death. To reduce uncertainty about PFS as a surrogate, the hypothesis that subsequent-line agents or changes in supportive care over time impact the ability of PFS to reliably predict OS could be directly tested. As suggested by a recent editorial, PFS is a biologically plausible measure of efficacy and a goal of breast cancer treatment is to improve both quality and quantity of life (56). Therefore, PFS may be an appropriate primary endpoint even if is not a formal surrogate endpoint with an ability to predict OS (56). Analyzing the association between PFS and quality-of-life and/or freedom from symptom progression data would further test the value of PFS as an independent, clinically meaningful primary endpoint.

The high percentage of progression-based endpoints that were re-classified to meet U.S. FDA and EMEA definitions and the sensitivity analysis results suggest that the definition of PFS should be universal and carefully detailed in trial protocols and publications. The U.S. FDA and EMEA draft proposals regarding surrogate endpoints have the same PFS definition. However, recommendations for censoring, determination of the date of progression, and missed visits differ (25;65). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement (40) and the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (63) may provide a model for standardizing PFS definition, measurement, and reporting.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This meta-analytic, trial-based analysis of anthracyclineand taxane-based chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer suggests that while the trial-level treatment effect on PFS is significantly associated with the trial-level treatment effect on OS, predictions based on trial-level PFS are surrounded with uncertainty for these treatments in advanced breast cancer. However, use of standardized endpoint definitions may increase the reliability and validity of surrogate endpoint data in advanced breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was in part funded by an unrestricted educational grant from Hoffmann La-Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland. The authors had complete and independent control over the following: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and publication of the manuscript. Dr. Miksad also received funding as a research fellow with the United States National Institutes of Health’s Program in Cancer Outcomes Research Training [R25-CA92203] at the Institute for Technology Assessment at the Massachusetts General Hospital. We acknowledge the assistance of Allan Hackshaw and Davina Ghersi for providing detailed information about their work.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were orally presented at the 29th Annual Meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making on October 23, 2007 (Lee Lusted Prize for outstanding presentation) and at the Eastern Oncology Cooperative Group Young Investigator Symposium on November 11, 2007 (Clinical Research Award for outstanding presentation) and as a poster at the Annual European Congress of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) on October 21, 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.A’Hern RP, Ebbs SR, Baum MB. Does chemotherapy improve survival in advanced breast cancer? A statistical overview. Br J Cancer. 1988;57:615–618. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackland SP, Anton A, Breitbach GP, et al. Dose-intensive epirubicin-based chemotherapy is superior to an intensive intravenous cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil regimen in metastatic breast cancer: A randomized multinational study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:943–953. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aisner J, Cirrincione C, Perloff M, et al. Combination chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent carcinoma of the breast—A randomized phase III trial comparing CAF versus VATH versus VATH alternating with CMFVP: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 8281. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1443–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. 1st Chapman and Hall; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armitage P, Berry G, Matthews JNS. Statistical methods in medical research. 4th Blackwell Science; Malden, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker SG, Kramer BS. A perfect correlate does not a surrogate make. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker SG. Surrogate endpoints: Wishful thinking or reality? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:502–503. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett JM, Muss HB, Doroshow JH, et al. A randomized multicenter trial comparing mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, and fluorouracil with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and fluorouracil in the therapy of metastatic breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1611–1620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biganzoli L, Cufer T, Bruning P, et al. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel versus doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 10961 Multicenter Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3114–3121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bishop JF, Dewar J, Toner GC, et al. Initial paclitaxel improves outcome compared with CMFP combination chemotherapy as front-line therapy in untreated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2355–2364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Rosso R, Santi L. Chemotherapy with or without tamoxifen in postmenopausal patients with late breast cancer. A randomized study. J Steroid Biochem. 1985;23:1123–1127. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(85)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burzykowski T, Molenberghs G, Buyse M. The validation of surrogate end points by using data from randomized clinical trials: A case-study in advanced colorectal cancer. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2004;167:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burzykowski T, Piccart MJ, Sledge G, et al. A quantitative study of tumor response and progression-free survival as surrogate endpoints for overall survival in first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer; 28th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas, United States. 2005. Abstract 6084. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burzykowski T, Buyse M, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, et al. Evaluation of tumor response, disease control, progression-free survival, and time to progression as potential surrogate end points in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1987–1992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buyse M, Molenberghs G. Criteria for the validation of surrogate endpoints in randomized experiments. Biometrics. 1998;54:1014–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan S, Friedrichs K, Noel D, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus doxorubicin in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2341–2354. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conte PF, Pronzato P, Rubagotti A, et al. Conventional versus cytokinetic polychemotherapy with estrogenic recruitment in metastatic breast cancer: Results of a randomized cooperative trial. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:339–347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conte PF, Baldini E, Gardin G, et al. Chemotherapy with or without estrogenic recruitment in metastatic breast cancer. A randomized trial of the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest (GONO) Ann Oncol. 1996;7:487–490. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Gruttola V, Fleming T, Lin DY, Coombs R. Perspective: Validating surrogate markers–are we being naive? J Infect Dis. 1997;175:237–246. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Gruttola VG, Clax P, DeMets DL, et al. Considerations in the evaluation of surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Summary of a National Institutes of Health workshop. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22:485–502. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Mastro L, Venturini M, Lionetto R, et al. Accelerated-intensified cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil (CEF) compared with standard CEF in metastatic breast cancer patients: Results of a multicenter, randomized phase III study of the Italian Gruppo Oncologico Nord-Ouest-Mammella Inter Gruppo Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2213–2221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Leo A, Bleiberg H, Buyse M. Overall survival is not a realistic end point for clinical trials of new drugs in advanced solid tumors: A critical assessment based on recently reported phase III trials in colorectal and breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2045–2047. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Efron B. Estimating the error rate of a prediction rule: Improvement on cross-validation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78:316–331. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ejlertsen B, Pfeiffer P, Pedersen D, et al. Decreased efficacy of cyclophosphamide, epirubicin and 5-fluorouracil in metastatic breast cancer when reducing treatment duration from 18 to 6 months. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:527–531. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Medicines Agency Appendix 1 to the guidelines on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man: Methodological considerations for using Progression Free Survival (PFS) as primary endpoint in confirmatory trials for registration [Draft] 2006 Dec; www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/ 26757506en.pdf.

- 26.Fleming TR, DeMets DL. Surrogate end points in clinical trials: Are we being misled? Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:605–613. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-7-199610010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming TR. Surrogate endpoints and FDA’s accelerated approval process. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:67–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A. A new endpoint for the assessment of adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal women with operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:1772–1779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.12.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelber RD, Gelber S. Quality-of-life assessment in clinical trials. Cancer Treat Res. 1995;75:225–246. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2009-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gennari A, Conte P, Rosso R, et al. Survival of metastatic breast carcinoma patients over a 20-year period: A retrospective analysis based on individual patient data from six consecutive studies. Cancer. 2005;104:1742–1750. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gennari A, Amadori D, De Lena M, et al. Lack of benefit of maintenance paclitaxel in first-line chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3912–3918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghersi D, Wilcken N, Simes RJ. A systematic review of taxane-containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:293–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hackshaw A, Knight A, Barrett-Lee P, Leonard R. Surrogate markers and survival in women receiving first-line combination anthracycline chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1215–1221. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jassem J, Pienkowski T, Pluzanska A, et al. Doxorubicin and paclitaxel versus fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophos-phamide as first-line therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: Final results of a randomized phase III multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1707–1715. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jassem J, Pluzanska A, Pienkowski T, et al. Randomized phase III multicenter trial of doxorubicin and paclitaxel (AT) versus fluorouracil-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide (FAC) as first-line therapy metastatic breast cancer (MBC): Long-term efficacy and external review of results. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, Texas, USA: 2004. Abstract 5043. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones SE, Erban J, Overmoyer B, et al. Randomized phase III study of docetaxel compared with paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer [see comment] J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5542–5551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langley RE, Carmichael J, Jones AL, et al. Phase III trial of epirubicin plus paclitaxel compared with epirubicin plus cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute trial AB01. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8322–8330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molenberghs G, Burzykowski T, Alonso A, Buyse M. A perspective on surrogate endpoints in controlled clinical trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2004;13:177–206. doi: 10.1191/0962280204sm362ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molenberghs G, Buyse ME, Burzykowski T. The history of surrogate endpoint validation. In: Molenberghs G, Buyse ME, Burzykowski T, editors. Statistics for biology and health: The evaluation of surrogate endpoints. New York: Springer: 2005. pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nabholtz JM, Gelmon K, Bontenbal M, et al. Multicenter, randomized comparative study of two doses of paclitaxel in patients with metastatic breast cancer [see comment] J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1858–1867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nabholtz JM, Senn HJ, Bezwoda WR, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus mitomycin plus vinblastine in patients with metastatic breast cancer progressing despite previous anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. 304 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1413–1424. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Namer M, Soler-Michel P, Turpin F, et al. Results of a phase III prospective, randomised trial, comparing mitoxantrone and vinorelbine (MV) in combination with standard FAC/FEC in front-line therapy of metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1132–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niimi M, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, et al. The Influence of handling censored data on estimating progression-free survival in cancer clinical trials (JCOG9913-A) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:19–26. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyf003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Panageas KS, Ben-Porat L, Dickler MN, et al. When you look matters: The effect of assessment schedule on progression-free survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:428–432. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paridaens R, Biganzoli L, Bruning P, et al. Paclitaxel versus doxorubicin as first-line single-agent chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: A European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Randomized Study with cross-over. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:724–733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parnes HL, Cirrincione C, Aisner J, et al. Phase III study of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and fluorouracil (CAF) plus leucovorin versus CAF for metastatic breast cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9140. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1819–1824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perry MC, Kardinal CG, Korzun AH, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in advanced carcinoma of the breast: Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocol 8081. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1534–1545. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.10.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pierga JY, Jouve M, Asselain B, et al. Randomized trial comparing two different modalities of administration of the same cytotoxic drugs in metastatic breast cancer. J Infus Chemother. 1995;5:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierga JY, Jouve M, Asselain B, et al. Randomized trial comparing protracted infusion of 5-fluorouracil with weekly doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide with a monthly bolus FAC regimen in metastatic breast carcinoma (SPM90) Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1474–1479. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, Haller DG, et al. Disease-free survival versus overall survival as a primary end point for adjuvant colon cancer studies: Individual patient data from 20,898 patients on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8664–8670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sargent DJ, Patiyil S, Yothers G, et al. End points for colon cancer adjuvant trials: Observations and recommendations based on individual patient data from 20,898 patients enrolled onto 18 randomized trials from the ACCENT Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4569–4574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sargent DJ, Hayes DF. Assessing the measure of a new drug: Is survival the only thing that matters? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1922–1923. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sjostrom J, Blomqvist C, Mouridsen H, et al. Docetaxel compared with sequential methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced breast cancer after anthracycline failure: A randomised phase III study with crossover on progression by the Scandinavian Breast Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1194–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sledge GW, Neuberg D, Bernardo P, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and the combination of doxorubicin and paclitaxel as front-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: An intergroup trial (E1193) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:588–592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sledge GW, Jr, Hu P, Falkson G, et al. Comparison of chemotherapy with chemohormonal therapy as first-line therapy for metastatic, hormone-sensitive breast cancer: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:262–266. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith RE, Brown AM, Mamounas EP, et al. Randomized trial of 3-hour versus 24-hour infusion of high-dose paclitaxel in patients with metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol B-26. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3403–3411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Speyer JL, Green MD, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, et al. ICRF-187 permits longer treatment with doxorubicin in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:117–127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang PA, Bentzen SM, Chen EX, Siu LL. Surrogate end points for median overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: literature-based analysis from 39 randomized controlled trials of first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4562–4568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3.0: Development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.V. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) & Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting.Dec 16, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 65.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) & Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for Industry Clinical trial endpoints for the approval of cancer drugs and biologics. 2005:1–26. [Draft Guidance] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winer EP, Berry DA, Woolf S, et al. Failure of higher-dose paclitaxel to improve outcome in patients with metastatic breast cancer: Cancer and leukemia group B trial 9342. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2061–2068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu RX, Holmgren E. Endpoints for agents that slow tumor growth. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zielinski C, Beslija S, Mrsic-Krmpotic Z, et al. Gemcitabine, epirubicin, and paclitaxel versus fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide as first-line chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: A Central European Cooperative Oncology Group International, multicenter, prospective, randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1401–1408. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]