Abstract

Background

Latino smokers are a rising public health concern who experience elevated tobacco related health disparities.

Purpose

Additional information on Latino smoking is needed to inform screening and treatment.

Analysis

Latent class analysis using smoking frequency, cigarette preferences, onset, smoking duration, cigarettes per day and minutes to first cigarette were used to create multivariate latent smoking profiles for Latino men and women.

Results

Final models found seven classes for Latinas and nine classes for Latinos. Despite a common finding in the literature that Latino smokers are more likely to be low-risk, intermittent smokers, the majority of classes, for both males and females, described patterns of high-risk, daily smoking. Gender variations in smoking classes were noted.

Conclusions

Several markers of smoking risk were identified among both male and female Latino smokers including long durations of smoking, daily smoking and preference for specialty cigarettes, all factors associated with long-term health consequences.

Keywords: Smoking, Latino, Health disparities, Latent class, Gender, Nicotine

Introduction

Smoking among Latinos has been identified as a rising public health concern (1–4). Cigarette smoking remains the number one cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States (5, 6). Despite the relative success of public health programs and the accompanying decline in the overall prevalence in smoking (7), sub-groups of smokers, such as Latino smokers, have not seen the same decline in smoking and are among the priority subgroups experiencing tobacco related health disparities (8). Smoking related cancer is a leading cause of death among Latinos and Latinos face unique smoking related health disparities related to reduced treatment accessibility and physician guidance on quitting (2, 4). These disparities are believed to result from differential smoking careers and other associated health factors (9). With 52 million people in 2012, Latinos are the largest and fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S. (10, 11). Reducing the health burden of smoking and related health disparities faced by Latinos has been identified as a priority issue by federal agencies, such as the National Cancer Institute, and Latino community leaders alike (12, 13) making Latino smokers an important target group for increased research and treatment efforts.

Latino smoking is not well understood. Most smoking research has focused on heavy, daily smokers (14) or approaches smoking as a singular behavior, using broad classifications to capture smoking (e.g. ever/never) which limits our ability to tailor screening and prevention efforts and may misclassify individuals with the potential to overlook them entirely (15). This is of particular concern for populations like Latinos, who appear to have different cigarette consumption patterns (16) such as intermittent smoking but who continue to experience similar rates of health disparities due to their smoking (17–20). A better understanding of smoking characterization among priority populations (e.g. Latinos) is needed in order to inform tailored screening and prevention efforts (2, 21).

When research does focus on Latino smoking the investigation is often limited. Most studies are generally descriptive or focus on a narrow subset of smoking outcomes such as current smoking or smoking frequency and use means-based analytic methods (e.g. regression) that average across individuals (15, 22). Few studies take a comprehensive approach to investigating Latino smoking. The current study adopts a multivariate investigation of Latino smoking using exploratory latent class analysis based upon several cigarette smoking items, among a nationally representative sample of Latino men and women living in the United States. It is exploratory because there is little guidance on what patterns to expect among Latino smokers. However, this descriptive work may contribute to an improved understanding of the variability in Latino smoking careers and diverse smoking profiles which can inform culturally tailored screening and prevention programs.

Review of the Literature

Latino Smoking

Latino smokers appear to be cut from a different cloth. National and regional surveys of smoking indicate that Latinos have lower rates of current smoking compared to white smokers (23), smoke less frequently and consume fewer cigarettes per day than white smokers (3, 24, 25), and initiate smoking at a later age than white smokers but earlier than African American (AA) smokers (3, 26) all extant markers of lower risk for health consequences. Findings are mixed regarding duration of smoking with some evidence to suggest that Latinos smoke for longer periods than whites (26) while other studies find that Latinos smoke for shorter durations than white or black smokers (27). However, the term “Latinos” clusters together a diverse array of ethnicities, nationalities and races (28). Differing subsets of Latino ethnicity has been found to influence smoking differently across groups (22).

While some of these generalized statistics appear promising (e.g. consuming fewer cigarettes per day), some are deeply concerning. For example, Burns’ (26) findings that Latino smokers initiated later (18.4 versus 17.7) but also smoked on average three years longer over their lifetime than white smokers. Notably, longer duration of smoking is associated with increased risk for lung cancer (29), lung cancer death (30), and coronary heart disease (31), while shorter durations of smoking are associated with increased life expectancy (32).

Latino smokers are also more likely to be never-daily, occasional, intermittent or light smokers and consume fewer than 10 cigarettes per day compared to white smokers (22–24, 33–35). Some evidence, based on a sample of white smokers, suggests that low level smokers are more likely to quit, have lower levels of withdrawal, and have increased success at quitting (36) but it is not known if this is true among Latino smokers. In fact, there is evidence to the contrary. In a study by Reitzel and colleagues (2) Latino light smoking levels were not associated with increased quitting attempt or cessation success suggesting that Latino light smokers while not smoking heavily may be at risk for persistent light smoking. Light or intermittent smokers are not usually included in clinical trials examining smoking cessation due to their lower risk for health problems and that heavy smokers are a greater priority in smoking research (2, 16). This exclusion potentially omits a large group of Latino smokers despite the fact that even light smokers have been found to have rates of death from lung cancer two-fold higher for women and four-fold higher for men compared to their non-smoking counterparts (37).

In addition to differing risky smoking behaviors (e.g. onset, frequency, and duration), Latinos also report higher preference for mentholated cigarettes (3, 38) compared to whites. Menthol is a flavoring added to most US commercial cigarettes, though in non-mentholated brands it is typically in quantities too low to be noticed (39). Furthermore, menthol may have a role in smoking onset and elevated dependence (39, 40) though this has received mixed support in the literature (41–43). Gandhi (38) found that Latino smokers who preferred mentholated cigarettes, compared to non-mentholated, were more likely to smoke sooner after waking and reported more interrupted sleep, two indicators of nicotine dependence. Smokers preferring menthol were also less likely to be abstinent at the 4 week and six month follow ups (38). Interestingly, the study also found that Latino smokers who smoked mentholated cigarettes smoked less cigarettes per day (38) suggesting that cigarette choice plays a critical role in Latino smoking frequency and cessation success.

Gender Differences in Latino Smoking

Smoking related health disparities exhibited by Latinos have been hypothesized to be in part driven by smoking pattern differences among Latinos and Latinas. Substantial and consistent differences exist between Latino men and women across Latino sub populations such as Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Mexican/Mexican Americans (22, 35). Latinos, compared to Latinas, have been found to smoke earlier in life (26), have higher rates of current smoking (22); be heavier smokers (22), and have longer durations of smoking (26). Latinas in contrast are more likely to choose mentholated cigarettes (38), report smoking for different reasons such as anxiety and the need to feel thin (44), have different risk factors associated with smoking (22) and different health outcomes (45) compared to Latinos. For instance, acculturation appears to be a key factor in Latino smoking but in the opposite directions for men and women. For women being more acculturated significantly increased the chances of current smoking whereas for men acculturation decreased the likelihood of being a current smoker (22).

These gender differences are also present when compared across ethnic groups. In a review of several national and regional smoking studies, Marcus and Crane (1985) concluded that, overall, Latino males smoke equivalently with white males but Latinas smoke significantly less than white female counterparts. The review noted that when averaged across gender it looks as if Latinos smoke less than white smokers. When separated by gender the gap between Latino and White smokers narrow for men but persist for women. Other studies have identified a similar pattern. Latino boys initiate only 1 year later that Caucasian adolescents while Latinas onset approximately 2 years later than their white counterparts (3). Rates of current smoking reflect a similar pattern with 21% of Latino males reporting current use versus 25% of white males, compared to 11% of Latinas reporting current smoking to 23% of white females (46). Lastly, epidemiological data find that Latino males eventually catch up and surpass the smoking of their white male counterparts in middle to older adulthood, between the ages 45–64, despite later onset and a slower growth of current use. Latinas consistently display lower rates of current smoking and at no developmental period approach the prevalence of their white smoking counterparts (9).

It has been suggested that more research is needed to understand smoking and profiles that are distinct for Latinos and Latinas (35) and that future smoking programs for Latinos may have to be gender-sensitive due to the differing behaviors in this population (22).

Multivariate Approach to Smoking

As evidenced above Latino smoking is multifaceted with differing components and variation by gender. A behavior as complex as smoking may best be investigated by considering how each component (e.g. onset, frequency, cigarette preference, etc.) contributes to a larger smoking profile and career. To date most cigarette smoking studies focus on classifying tobacco use by singular outcomes such as the amount an individual consumes or the frequency at which an individual uses tobacco (e.g. (15, 47). This approach may not capture the complex nature of smoking. One approach that has been suggested, but utilized in few studies, is latent class analysis. This approach decomposes the overall population variability in cigarette smoking by identifying homogenous smoking classes or patterns based on multiple measures. This technique may be particularly relevant for priority populations such as Latino smokers whose smoking is less well understood than their white counterparts.

Latent class analysis has been used to characterize heterogeneity among other subgroups of smokers including current daily smokers (15); young women (48) and diabetic smokers (49) and has been used to categorize smokers based on tobacco product utilization (50, 51), nicotine dependence symptoms (15, 51–54) and comorbid smoking - mental health profiles (55). However, these studies’ samples are primarily composed of white smokers: Erickson et al. 2014 (89% White) (50); Timberlake et al., 2008 (41.4% white, 11.1% AA, 20.7% Latino) (51); Furberg et al., 2005 (100% white) (15) and, Gariepy et al., 2012 (94% Caucasian)(49). In addition, when latent class analysis is used in smoking research, gender is either not a focal point of the analysis (55) or is used as an indicator for classes (15, 49).

The goal of the current study is to explore the prevalence and variability of different smoking patterns/classes/types among Latino men and women. While exploratory, the identified classes may begin to extend our understanding of Latino smoking, as well as identify possible variations between men and women. Findings from this study can begin to inform tailored tobacco use screening and prevention among Latinos.

Methods

Sample

The latent class model was used to explore the prevalent patterns of smoking among Latinos participating in the 2003 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS). The Current Population Survey is a monthly national survey of basic economic and labor data. The Tobacco Use Supplement is developed by the National Cancer Institute and includes questions on general tobacco use, including onset, use and cessation. It was included in the February, June and November Current Population Surveys. (For more information on the Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey, please go to the National Cancer Institute’s webpage on the survey, http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/studies/tus-cps/.)

After combining the three months, the total sample of people providing data was 191,169. Proxy interviews were not included in the current study. The cigarette smoking items were only asked of people who had ever smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lives reducing the sample size to 35,359. The sample was then limited to men and women identifying themselves as Latino. Individuals identifying as more than one racial or ethnic group were not included. The final sample sizes were 959 Latinas and 1292 Latinos.

Measures: Latent Class Items

The 2003 Tobacco Use Supplement had a brief set of shared questions and then separate forms based upon whether or not a respondent indicated being a daily or intermittent smoker. All the items used here were either the same for daily and intermittent smokers, or else a comparable quantity could be calculated from the survey questions. There are four categorical and four metric items.

The first item was “Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days or not at all? Those replying “Not at all” were removed from the data, and every day was coded as 1 and some days was coded as 2. The second item “Around this time 12 MONTHS AGO, were you smoking cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?” was coded as 1 = Every day; 2 = Some days and 3 = Not at all. The third categorical item “Is your usual cigarette brand menthol or non-menthol?” was coded as 1 = Non-menthol and 2 = Menthol. The original item had a third category, “No usual type” which was recoded as missing. The fourth categorical item was “What type of cigarette do you now smoke most often -- a regular, a light, an ultralight, or some other type?” It was coded as 1 = Regular and 2 = light or ultra-light. Responses of “No usual type” and “Some other type” were recoded as missing. In analyzing these last two items with responses recoded to missing as described, an assumption is being made that the associations between the rest of the items are the same whether or not someone is missing the menthol and/or light cigarette items.

The first of the four metric items is “How old were you when you first started smoking cigarettes FAIRLY REGULARLY?” and age by year was recorded. Anyone giving an age below six was coded as missing. The second item was “What is the total number of years you have smoked EVERY DAY?” Current intermittent smokers were asked if they ever smoked every day. If they indicated Yes, they were asked how many years they smoked every day. If they had never smoked every day, they were coded as a zero. The third item was a measure of respondents’ daily exposure in terms of a number of cigarettes. For daily smokers, this was simply their response to the question “On the average, about how many cigarettes do you now smoke each day?” Intermittent smokers replied to the following questions: “On how many of the past 30 days did you smoke cigarettes?” and “On the average, on those (number of) days, how many cigarettes did you usually smoke each day?” To compute the daily exposure for some day smokers, the answers to these two questions were multiplied and the product divided by 30 to form a daily exposure. The last of the metric items was the number of minutes after waking until the respondent had his or her first cigarette. Daily smokers were asked “How soon after you wake up do you typically smoke your first cigarette of the day?” and intermittent smokers were asked “On the days that you smoke, how soon after you wake up do you typically smoke your first cigarette of the day?”

Measures: Relevant Demographic Items

In order to gain better insight into the identified classes of smokers, we estimated associations between the latent classes and important demographic items including marital status, educational attainment, age of respondent and if the respondent was living in poverty. Selection of associated demographic variables was based upon literature pointing to the potential relevance of these variables and their availability in the Current Population Survey – Tobacco Use Supplement data set. Marital status was a dichotomized yes/no if the participant was currently married. Those who were separated, widowed, divorced were coded as not married. Educational attainment was a categorical variable based upon participants self-reported highest level of education completed at the time of interview. Education was coded as follows: 1 – Less than High School, 2 – High School graduate, 3 – Some college, 4 – College graduate and 5 – Advanced educational attainment (masters or doctoral degree). Age was based on participant report of age at time of interview and recoded as a developmentally categorical variable where 1 – Adolescent/Young Adulthood (15–24), 2- Adulthood (25–34), 3 – Middle Adulthood (35–65), and 4 – Older Adulthood (66–80). Lastly, living in poverty was a dichotomized yes/no variable calculated by combining two variables: household income and number of people in the household and then using this variable compared against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014 poverty guidelines outlined at (http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm) (56).

Four additional demographic items regarding respondent’s nationality and acculturation in the U.S. were also added to better understand class composition specifically among Latino smokers. Being born in the U.S. was a dichotomous yes/no variable based upon participant self-report. Length of time in the U.S. was a categorical variable based upon self-reports of year of immigration which were then subtracted from the year of assessment and coded to describe the approximate length of time living in the U.S. : 1-0–10 years, 2- 11–20 years, 3 – 21 or more years, and 4 – those born in the U.S.. Second generation status combined three variables reported by the respondent – mother’s country of birth, father’s country of birth and respondent’s country of birth – to create a categorical variable where (1) were U.S. born respondents whose parents were both born in the U.S., (2) were respondents born in the U.S. who had either one or both parents born outside the U.S. and (3) were respondents born outside the U.S. and whose parents were born outside the U.S.. Category (2) was considered second generation Americans. Lastly, respondent’s reports of country of origin were used to create a categorical nationality variable. Due to scarcity across multiple countries the variable was collapsed to capture the top three countries of origin including 1 – U.S., 2 – Mexico, 3 – Puerto Rico and 4 – Other Latin country of origin.

Missing Data

Missing data rates were modest, ranging from about 1% to 15%. Minutes to the first cigarette was missing most often. Missing data for menthol and light/ultra-light cigarette preferences ranged from 3 to 10% among Latino men and women respectively. In all cases, responses of “Refused”, “Don’t know”, etc., were coded as missing and retained in the analysis.

Analysis

The standard latent class model is a categorical data latent variable model that links responses to categorical items to an unobservable (latent) categorical variable that indexes the sub-groups (classes) in a population; for an overview of these models see references such as (57, 58). Latent variable models, such as factor analysis and latent class models, assume that an unobserved variable is largely responsible for observed item responses. In the latent class case, membership in a particular class is expected to be predictive of responses made to a set of items. These parameters are the response probabilities. The latent class model also includes latent class proportions, which are simply the proportion of the population expected to be members of each latent class. Note, the sum of all the estimated latent class proportions is 1.0 because it is assumed that everyone in the population belongs to one and only one of the classes. The statistical model used here is an expansion of the standard latent class model for situations where some items are categorical and others are metric or quantitative (59, 60). Response probabilities are still estimated for the categorical items but in addition, means and variances are estimated for the metric variables. That is, classes may now vary on both response probabilities for categorical items and class means for metric items.

Exploratory latent class models were run separately for Latino and Latinas. One (i.e., the full independence model) through twelve class models were fit to each data set. Metric variables were transformed so that normal distribution assumptions were more plausible and then standardized. The age one first smoked regularly and the number of years one has smoked daily were both transformed by taking the square root. Daily exposure and minutes to first cigarette were transformed by taking the natural logarithm. For each model (i.e., a number of classes), 2000 sets of random start values were run in order to assess the identification of each solution. The models were estimated using a Fortran program written and maintained by the second author.

Model Selection

Fit assessment and model selection in latent class and mixture models is challenging, and continues to be an active applied statistics research topic. Reviewing this area is beyond the scope of this paper, but in short, no statistical measure of fit has yet emerged as the gold standard for latent class models across research situations. Therefore, following general model selection recommendations by Browne and Cudek (61) and Flaherty (62), we have used widely accepted statistical indices along with a close examination of the scientific and substantive implications of a specific model.

Latent class models with both metric and categorical indicators have no clear degrees of freedom or fit statistics. As such one must use some relative fit assessment quantity. We chose to use two relative indices with clear statistical foundations and broad support in the applied statistics literature: Akaike’s (63) and Bayes’ information criteria (64, 65) (AIC and BIC, respectively). These both penalize the final loglikelihood value in order to try to balance model fit with model complexity. More complex models will always fit better than less complex ones, but the more complex a model becomes the more likely it may be reproducing noise in the data, rather than substantively meaningful features. However, it is also possible that information criteria such as BIC may point to a less complex model, when a more complex model is substantively more compelling. Therefore, AIC and BIC were used as initial guides to indicate a preferred model size. Following this, model identification and the substantive interpretation of neighboring models were examined. For example, if BIC suggested a 7 class model, it was substantively compared with the solutions for a 6 and 8 class model. Final selected models were therefore arrived at through a combination of substantive story and statistical fit.

If a solution had one or more uninterpretable classes, it was rejected. Similarly, very small latent classes were generally considered undesirable because they may only reflect the data of very few people, or random noise.

Univariate associations with demographics

After choosing models for Latinos and Latinas, univariate associations between the classes and relevant demographics were estimated. This was done as a two-step process. Following estimation of the latent class model, the measurement estimates (response probabilities and means) were held constant and conditional distributions of the demographic variables were estimated. Estimating latent class models with outcomes is an active research area with no clear preferred method yet. This approach retains the uncertainty of class assignments that a hard classification approach (such as saving out classes) ignores, but maintains the desired class structure. Our approach estimated these associations via an algorithm that does not yield standard errors. Therefore, the association estimates between latent classes and demographics in the current analysis do not have uncertainty estimates. However, the purpose of these associations is to serve as a preliminary understanding of class composition and to provide a sense of construct validity with the classes (for example, does age as an outcome co-vary sensibly with number of years smoked daily?). Additionally, the estimates provide insight into any interesting or large differences between the distributions across classes that might bear further investigation.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

Latinos, across gender, in the current sample identified as being current daily smokers (65%) and intermittent smokers (34%) defined here as those individuals who smoke less than daily. Men and women were equally as likely to report being a daily or intermittent smoker. Among Latino smokers, there were gender differences in smoking. Specifically, men began smoking slightly earlier than women (17.9 vs. 18.4), and were more likely to be an intermittent smoker in the previous year, and prefer regular, non-mentholated cigarettes. Women, compared to men, were more likely to report daily smoking in the previous year and reported a stronger preference for light cigarettes. Overall there were relatively few gender differences in the indicators including average minutes until first cigarette upon waking, duration of years of regular use, and total number of cigarettes consumed per day. Descriptive information is provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Prevalence and mean differences between Latino males and females among Latent Class Indicators - Categorical Indicators

| Indicator | Range | Males (N=1292) | Females (N=959) | χ2 difftest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Menthol | 1–2 | 26.0(1), p<.05 | ||

| Not Menthol | 890 (76.4%) | 605 (66.3%) | ||

| Menthol Preference | 275 (23.6%) | 308 (33.7%) | ||

| Light Cigarettes | 1–2 | 42.7(1), p<.05 | ||

| Regular Cigarettes | 741 (58.9%) | 420 (44.8%) | ||

| Light Cigarettes | 517 (41.1%) | 517 (55.2%) | ||

| Current Smoking Frequency | 1–2 | 1.82(1), p>.05 | ||

| Daily Smoker | 822 (64.3%) | 636 (67.0%) | ||

| Intermittent Smoker | 457 (35.7%) | 313 (33.0%) | ||

| Past Year Smoking Level | 1–3 | |||

| Daily Smoker | 717 (57.3%) | 571 (61.6%) | 4.1(2), p<.05 | |

| Intermittent Smoker | 436 (34.8%) | 285 (30.7%) | ||

| Non-Smoker | 99 (7.9%) | 71 (7.7%) |

Notes: Significant mean and proportion differences between males and females are in bold.

M(SD) = Mean and (St. Deviation); N (%) = Number of participants and (prevalence).

Table 2.

Prevalence and mean differences between Latino males and females among Latent Class Indicators – Continuous Indicators

| Indicator | Range | Full Sample | Males (N=1292) | Females (N=959) | χ2 difftest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Age of Smoking Onset | 7–65 | 18.1 (5.5) | 17.9 (5.2) | 18.4 (5.8) | −1.96, p<.05 |

| Duration of Years Smoking | 1–86 | 13.6 (13.7) | 13.7 (14.2) | 13.4 (13.0) | .64, p>.05 |

| Cigarettes Smoked Per Day | .3–60 | 8.8 (8.4) | 9.1 (8.7) | 8.5 (7.9) | 1.81, p>.05 |

| Minutes to Smoking | 1–5400 | 194.5 (306.8) | 189.9 (304.8) | 200.5(309.5) | −.75, p>.05 |

Notes: Significant mean and proportion differences between males and females are in bold.

M(SD) = Mean and (St. Deviation); N (%) = Number of participants and (prevalence).

Model Selection

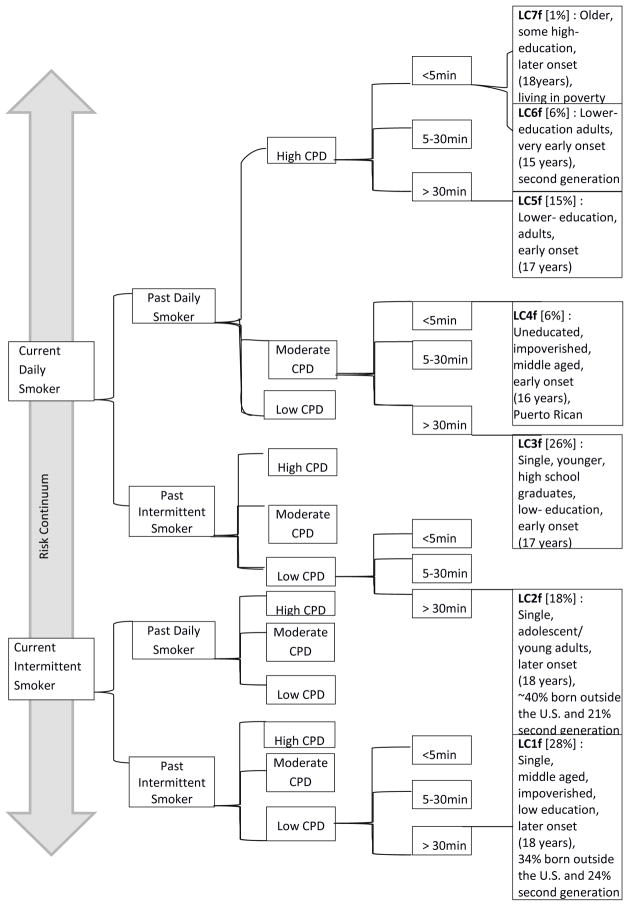

AIC did not reach a minimum for either Latina or Latino smokers, therefore, we relied upon BIC. Among Latinas, BIC indicated the seven class model and this is reported (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Latent Classes of Female Latina Smokers along a Risk Continuum.

CPD: Cigarettes per day. High 16+; Moderate: 3–15; Low: 0–2

Min: Minutes. LC#f Latent Class (#) females.

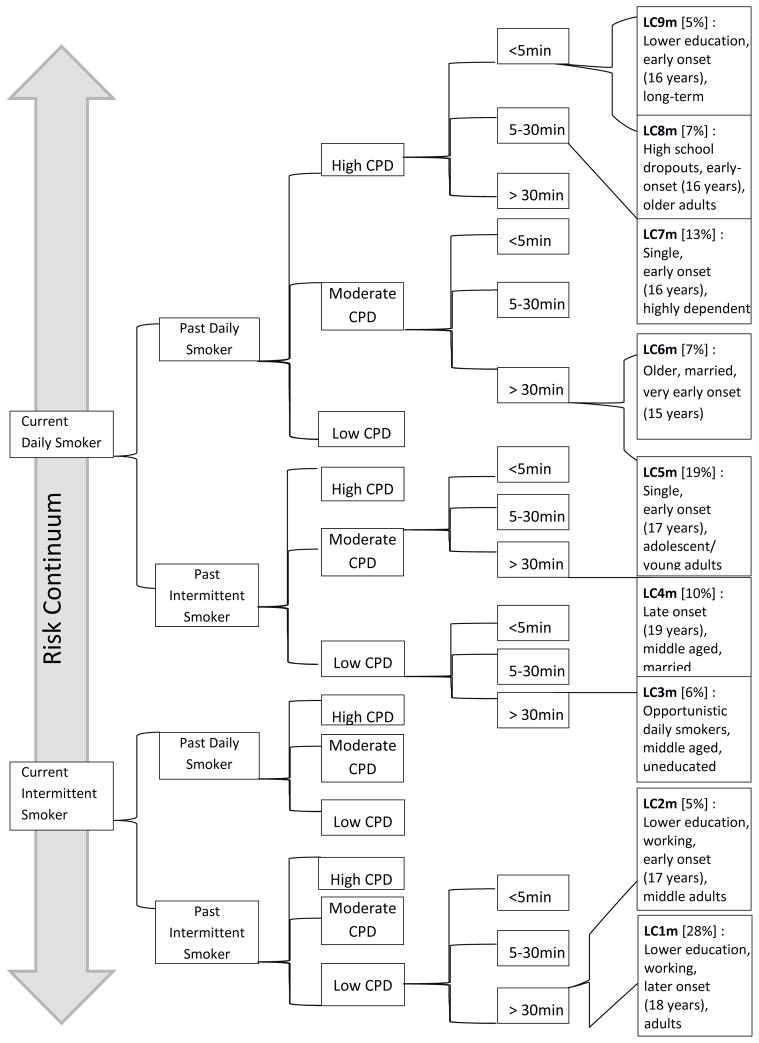

A nine class model was selected for Latinos (Figure 2). The BIC indicated that eleven classes was the best choice, however, the eleven class solution did not appear identified. There were substantial differences between the best two solutions. The ten class model had a small class (approximately 1%, or about 15 people) that was only noteworthy in that they were likely to have started smoking later in life. The other features of the class mirrored a class in the nine class model. Therefore, the slightly simpler nine class model is presented. Tables of the latent class analysis fit statistics and parameter estimates are available as supplemental materials online.

Figure 2.

Latent Classes of Male Latino Smokers along a Risk Continuum.

CPD: Cigarettes per day. High 16+; Moderate: 3–15; Low: 0–2

Min: Minutes. LC#m Latent Class (#) males.

A description of each class is provided separately for men and women below. Descriptions of the class are based upon conditional probabilities of response patterns given a participants latent class membership. For example when we report that a class reports consistent daily smoking (both current and in the past) this is reflecting that participants in this class overall have a high likelihood of reporting being a current daily smoker and daily smoker in the past year. Classes are reported along a continuum of risk based upon extant literature mentioned above that cites early onset, daily smoking, dependence and long duration as higher risk indicators of smoking compared to later onset, non-dependent short duration smoking (3, 24, 25, 26, 29).

Model Interpretation – Latina Women

The model for the Latina women had 6 daily smoker classes, that accounted for 72% of the sample and 1 intermittent smoker class that accounted for 28% of the sample. Notably, there is a fair amount of variability (29–64%) for the light/regular cigarette item. In contrast, there is little variability across the classes for the age first smoked regularly (15–18) and preference for menthol.

Among the Latina female smokers, there was only one intermittent smoker class (LC1f) that was the largest of all the smoking classes for this group (28%). Members of this class were more likely to consistently report intermittent smoking both currently and historically, onset at age 18, have a preference for light cigarettes and display low nicotine dependence with time to first cigarette at approximately four hours after waking on average. This profile and smoking career is what the majority of literature characterizes Latino women as falling into (9). On the risk scale these women represent lower-risk intermittent smokers.

While intermittent female smokers made up the largest class, 72% of participants were classified as daily smokers across 6 classes. The next class based off of risk factors was LC2f (18%) which grouped Latina smokers as those who were more likely to report current daily smoking but a subset (26%) of which reported that they had been intermittent smokers the year before. This may suggest a group of women increasing in their smoking. LC2f women were more likely to begin smoking around age 18, had lower signs of dependence (6 hours to first cigarette), only smoked about 3 cigarettes a day, and had a higher likelihood of showing a preference for light cigarettes. LC2f reported over a decade of regular smoking on average. This group is notable for its low dependence and consumption, its escalating smoking and high duration of regular use.

Of the six daily smoker classes for women, the largest daily smoking class and the class highest in the risk spectrum, was LC3f, representing 26% of Latinas. LC3f was characterized by high likelihoods of consistent reports of daily smoking, consuming about a half a pack of cigarettes per day, adolescent smoking onset (17 years of age), over a decade of regular smoking on average but displayed marginal dependence criteria with average time to first cigarette being within an hour of waking. While these women are reflective of more traditional standards of high risk smoking, the longer time to first cigarette is notable.

LC4f is similar to LC3f in terms of higher risk smoking with the exception that LC4f also demonstrate high dependence with an average time to first cigarette of only 3 minutes on average. These women would be considered by current standards in the extant literature as high risk, most likely to be included in cessation trials, and identified as risky smokers by physicians. It is important to note that this class is only capturing 6% of Latina smokers which is reflective of the low prevalence of high risk Latina smokers noted in available epidemiological literature (3).

LC5f and LC6f are similar smoking profiles distinguished by the severity of their dependence and age of onset. Both classes are consistently daily smokers, consume about a pack of cigarettes a day, and have over 20 years of regular smoking on average. Both exhibit high dependence with an average time to first cigarettes of 3 minutes for LC6f and LC5f slightly less dependent at 30 minutes. The main difference between these two classes appears to be in the timing of onset among these women. LC5f has an average age of onset of 17 years, which is closer to the average age of onset among the Latino population (18 years) noted in national studies (3, 26). LC6f onsets at 15 years of age, far earlier than what is normally noted among Latinos in general and especially early for Latinas suggesting that of the two classes LC6f is the higher-risk class.

The last class (LC7f) is the smallest latent class and captures 1% of Latinas. This class was retained for its substantive relevance. In LC7f we see Latinas who are consistent daily smokers, onset around 18 years of age, have almost two decades of regular smoking, high dependence symptoms and a preference for non-mentholated, regular type cigarettes. This class is notable for its extraordinarily high daily cigarette consumption with reports of average number of cigarettes per day at 45 units representing over two packs a day.

Model Interpretation – Latino Men

Latino men also demonstrated a high variability in smoking. Seven classes of daily smokers accounted for 67% of the sample and two intermittent smoker classes made up the balance of 33%. The largest class of smokers, at 28% of the sample (LC1m), were more likely to report being consistent intermittent smokers with low dependence symptoms (> 4hours to first cigarette), initiating on average at age 18, had never been daily smokers and a high likelihood of reporting a greater preference for non-mentholated cigarettes while only half preferred light brands. Unlike women, men had one other class categorized by intermittent smokers. LC2m was also categorized by current intermittent smokers with low cigarette consumptions, low dependence symptoms and similarly low preference for mentholated and light cigarettes. The primary difference in these two classes lies in the length of duration of regular smoking with LC1m having no years of regular smoking accumulated in their career whereas LC2m reports 8 years of regular smoking in their career on average. LC2m also had a small subset of men who smoked daily in the prior year (24%) suggesting a decrease in using behavior.

In terms of risk behaviors in smoking indicators the class LC3m is unique among the seven daily smoker classes in that this class is made up of earlier onset, low consumption (3 cigarettes per day on average), current daily smokers with low nicotine dependence but who report intermittent smoking in the past year for one third of this class. LC3m is similar to women’s LC2f class in that it represents a class of escalating smokers. For men LC3m represents only 6% of the sample.

The remaining six daily smoking classes of Latino males can be simplified in explanation by a set of similarly patterned dyad of classes. For instance, LC4m and LC5m, the next two classes in terms of risk, both describe late adolescent onset, daily smokers who are more likely to report low consumption of cigarettes per day, have low dependence symptoms and exhibit no preference for specialty cigarettes. The second largest group of Latino smokers was LC5m (19%). Latino men in LC5m were consistent daily smokers, with onset around 17 years of age, over a decade of daily smoking, greater preference for non-mentholated (77%) cigarettes and a slightly higher preference for regular cigarettes versus light brands (59%). Interestingly this group, despite the risk markers of increased duration and high frequency smoking did not exhibit typical dependence criteria reporting an average time of first use 2 hours after waking. LC5m has over 13 years of reported smoking duration while LC4m only has 4 years of regular smoking suggesting that men in LC4m are at the beginning of their smoking careers and may mirror LC5m over time.

Likewise, LC6m & LC7m similarly describe earlier adolescent onset (15 and 16 years respectively) classes. Both LC6m and LC7m display consistent daily smoking, moderate consumption patterns, and elevated risk for dependence since they both smoke within 30 minutes of waking. Once again we see that LC6m is distinguished by a longer duration of reported regular smoking (42 years) compared to 21 years of regular smoking in LC7m.

LC8m and LC9m are classes of daily heavy smokers with early adolescent onset and high dependence symptoms distinguished, once again, by the length of regular smoking duration. LC9m has 31 years of regular smoking while LC8m has 7 years; LC8m and LC9m represent commonly targeted smokers, considered at highest risk, and represent those men most likely to be in clinical trials or involved in public health programming. It is notable that these two classes combined only constitute 12% of Latino participants.

Associations with Demographics

To better understand who was in each class of smokers identified via latent class analysis, we examined associations between the classes and smoking-relevant demographic variables including, developmental age, living in poverty, marital status, education level, being born in the U.S., time lived in the U.S. among those who immigrated, whether the respondent was second generation American (born in U.S. to one or two immigrant parents) and reported nationality. Demographic factors were not used in the latent class analysis. The associations elucidated a number of class differences both within gender and between genders. Any variations in associations across men and women are discussed for substantive interest as men and women have separate model solutions and tests of difference are not applicable in the current study.

Age of respondent aided in differentiating classes. For men, LC1m appears to be men who are at the start of a similar smoking history to LC2m. LC1m was composed of men approximately 10 years younger than LC2m. This age gap could explain the 8 year difference in smoking duration between LC1m who had no years of regular smoking, and LC2m who had 8 years of regular smoking. The similarities between the two classes would suggest that prevention and intervention efforts aimed at LC1m may reduce the smoking related health burden associated with both classes.

Age of respondent was also associated with other key demographics and high-risk smoking profiles. Of concern is the high prevalence of adolescence (51%) in LC8m a high-risk smoking group among men. This group also had the highest amount of U.S. born participants and lowest percentage of second generation suggesting that for men acculturation plays an important role for smoking particularly among Latino youth. This trend was not detected among Latina smoking classes. This is contrary to the findings that for women but not men acculturation plays a significant role in smoking behavior (22).

For women, the group with the largest prevalence of adolescents and young adults was LC3f (23%), moderate-consumption, dependent, daily smokers. Unlike younger male smokers who were higher-risk this group of younger women smokers were more similar to the lower-risk intermittent smoking group LC1f. Similar to LC1f, younger women smokers in LC3f were also more likely to be single and not living in poverty but these young women reported less educational attainment (72% had completed High School or less at the time of the assessment) and were more likely to report being born in the U.S. (75%) than their lower risk counterparts. It may be that for young Latina women additional resources gained through educational attainment and work, i.e. medical insurance and cessation support, or work based restrictions, i.e. smoking bans in the work place, support women in LC1f from smoking as often or it may be a generational-acculturation impact where younger Latinas in LC3f were more likely born in the U.S. and were more likely to adopt smoking due to acculturation. Further investigation into the role that acculturation plays in smoking related gender differences among Latino is needed.

For both men and women the lowest risk intermittent smoking groups also had the highest number of participants born outside the United States. For lower-risk intermittent smoking women only 66% reported being born in the U.S. (LC1f) and 62% among the next lowest risk increaser group (LC2f). A similar pattern is seen among the first intermittent smoking classes for men (LC1m) and the increaser group (LC3m) with 37% and 36% of men in these groups respectively reporting being born in the United States. The increaser classes, for both men and women, also had foreign born respondents who had been living in the U.S. for a longer period of time than their consistent intermittent smoking counter parts. For example among intermittent smoking foreign born men in LC1m 21% reporting living in the U.S. for 20 or more years compared to the escalating smoking class LC3m where 55% of foreign born men reported living in the U.S. for twenty years or more. Interestingly, the second intermittent smoking class among men (LC2m) reported a high prevalence of U.S. born respondents (55%) distinguishing it from the other lower-risk smoking classes who were foreign born. This suggests that among a small group of Latino U.S. born males there are protective factors buffering them from acculturation.

Another association that generalizes across gender is that the highest risk smoking groups were associated with higher prevalence of living in poverty. Among men our highest risk smokers are LC7m, LC6m, LC8m and LC9m were early onset, dependent, daily smokers, who smoke long-term with the exception of LC8m. Class 3 emerged as a primarily middle aged group (82%) and appear to be a younger class of similar smokers to LC6m (33% of which were 66 years and older) and LC9m who was made up completely of middle aged participants. LC9m is distinct from LC6m due to the severity of dependence and that 73% of this class of high-risk smoking men reported living in poverty. For women, LC7f, consistent daily, long duration, high consumption and severely dependent smokers more than two-thirds of women reported living in poverty (67%). Both LC9m and LC7f also reported lower levels of educational attainment. Between these two groups men reported being married (60%) more often than women (43%).

Discussion

This paper presents the results of an exploratory latent class analysis of Latino men and women smokers in the 2003 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey. Eight items measuring aspects of current use, smoking history and cigarette preferences were examined. The primary goal of this work was to examine heterogeneity in Latino smoking patterns separately by gender. More distal goals are to possibly inform future prevention and screening efforts among Latino smokers (62). The current study findings highlight diverse smoking patterns across Latino and Latina smokers. Seven and nine classes were needed to summarize the data for men and women respectively and fit the data well. This indicates the wide range of behavior and patterns in the data.

The use of a multivariate approach to smoking among Latinos appears promising. The current study, when only considering average single indicators of smoking which is the norm in smoking research, found that Latino men and women both appear to be lower risk smokers and onset around age 18. Early onset is strongly associated with an individual’s risk for ongoing smoking and dependence (66) and beginning to smoke after adolescence has been found to lower an individual’s likelihood of becoming a regular smoker (67). As a group, they also have later time to first cigarette. The Heaviness of Smoking Index for Nicotine Dependence (68) provides common cutoffs for time to first cigarette upon waking used to gradate dependence (in order of increasing severity): 61+ minutes, 31–60 minutes, 6–30 minutes and less than 5 minutes. Latinos average of three hours to first cigarette clearly categorizes the group as low dependence and hence, lower risk. Further, cigarette consumption in the Heaviness of Smoking Index, also gradated by severity, is classified as1–10 cpd, 11–20cpd, 21–30 cpd, or 31+ cpd. Latinos in our sample smoke on average 9 cigarettes a day, also indicating their lower risk as a group on average.

However, other indicators suggest that Latinos are higher risk smokers. In our sample the average duration of regular use exceeds 13 years for both men and women. The Heaviness of Smoking Index’s definition of hard core smoking are those smokers who smoke regularly for at least 5 years suggesting that Latinos represent a high risk sub group of smokers. Lastly, the majority of Latino smokers report daily smoking versus intermittent smoking, also a marker of higher risk. Had only one of these indicators been used as outcomes, the full picture of Latino smoking risk may have been minimized or overlooked.

Using the multivariate approach to smoking behavior allowed the current study to identify distinct and developmentally unique risk groups among the latent classes. For instance LC3f, LC4m and LC8m represent developmentally distinct risk groups. Classes LC3f and LC8m were composed of early adolescent onset, regular smokers, with dependence, had the benefit of being targeted by current prevention efforts focused on preventing adolescent onset of smoking but despite this exposure continued to exhibit higher risk smoking behaviors including daily smoking, moderate consumption and moderate to severe dependence. This finding suggests that for a subset of Latino adolescents current smoking prevention efforts are not effective. In addition, LC4m represents similar smoking but poses unique risk. As adolescent late onset (age 19) escalating smokers without dependence, this group is largely missed by smoking prevention efforts and is not targeted by clinicians due to the low dependence symptoms.

Gender variations in the latent classes

Latent classes in association with relevant demographics were largely consistent across gender but some variations between Latina and Latino smokers were noted. For example, cigarette type preference displayed variations between genders. Latinas were more likely to prefer light cigarettes than men, which is consistent with the general smoking literature. Overall, women compared to men, regardless of ethnic background, prefer light cigarettes and women compared to men are identified as the primary targets of light cigarette marketing (69). Thus, our findings that more classes of Latina smokers were distinguished by a preference for light type cigarettes compared to men highlight the universal susceptibility to big tobacco marketing strategies. Additionally, menthol has been suggested to play a role in more rapid onset and stronger dependence (39, 40), but these results are mixed. Among Latina women daily smokers, where there was some variability in menthol preference across classes, higher menthol preference co-occurred with lower cpd and more time to first cigarette. This runs against the notion that menthol aggravates onset and dependence but is consistent with Gandhi’s (38) finding among Latinos that mentholated cigarette preference is associated with lower consumption. One interpretation of these findings and the mixed results in the literature is that menthol preference may not simply have a main effect on onset and dependence, but rather it may be moderated by factors associated with gender and culture.

Limitations

The current study has limitations that are worth noting. Model fit assessment in latent class and mixture models can be challenging, however, in the mixed indicator model employed here it is even more complex. Due to the exploratory nature of these analyses, we opted to balance numerical criteria and the substantive story of a solution. As with most research, replication will be important if classes such as those identified here are to be used to for intervention and/or treatment design.

The analyses presented here were conducted separately within gender. This allowed gender variation to emerge. However, other researchers might have chosen to analyze the data together and use gender as a predictor of class membership. An assumption of this latter approach is that measurement and class structure are the same across men and women. Given research literature suggesting that Latino and Latina smokers have different patterns of use, we chose to examine class structure separately.

In the present analysis identified classes were not associated with smoking cessation outcomes and attempts thus precluding predictive validity. The current study design was cross-sectional which limited our ability to link identified classes with long-term health consequences of their smoking. Longitudinal studies with the ability to replicate multivariate smoking profiles among Latinos are needed in order to see how differing smoking careers contribute to smoking related health disparities.

Implications

Despite these limitations the current study offers several strengths. Other studies have used latent class analysis (ex. Furberg et al., 2005) but were not able to include intermittent smokers due to a data limitation. To our knowledge, latent class analysis has also not been previously used on a Latino sample. Thus, the current study expands upon a limited subset of research utilizing latent class analysis to better understand the heterogeneity of smoking careers among priority populations, in this case Latino smokers, in order to better inform culturally tailored screening and prevention programming. Findings of differences in smoking careers and profiles among Latino men and women support the clinical utility of targeting subgroups of smokers in the general Latino population in order to more effectively impact smoking in this population.

The results of the current study point to several classes of Latino/as who began smoking much later in life. An implication for policy and prevention would be to focus smoking prevention efforts on Latino/a young-adults in addition to current adolescent-focused prevention efforts. Also the finding that most Latino/as had markedly lower smoking frequency but still demonstrated dependence symptoms may suggest that current physician screenings for problem smoking needs to be adapted for Latinos and that doctors should consider that for some of their Latino patients smoking should be assessed with multiple indicators. Instead of asking the screen question of do you smoke daily a fuller assessment may be necessary for this population.

A clear outcome of these results is that the perception that Latino smokers are lower risk and smoke less than other ethnic groups is incorrect. A large number of Latino smokers, both men and women, are long-term daily smokers. The presence of these classes in this study and the relative low prevalence of Latinos in cessation trials or low rates of doctor advice to quit is concerning. Traditional methods of identification, and prevention efforts may not work as well for Latino smokers. Latinos are less likely than white smokers to utilize smoking cessation aids, or engage in smoking related healthcare provision and are less likely to receive physician advice to quit smoking (3, 23, 70). It is not known if current smoking treatments are as effective for Latino smokers (71) and there are few randomized clinical trials of smoking cessation programs targeting Latinos (2, 72). What is known of smoking cessation in the Latino population is not optimistic, showing limited successes, particularly when cessation is followed out over longer periods (2, 44, 72, 73). Information from the current study can be used to inform treatment providers and researchers about potential behavior points for screening in order to reduce the public health burden of smoking among Latinos.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant # 5R37DA018673-11 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by the American Legacy Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors involved in the writing of the manuscript entitled “Latino cigarette smoking patterns by gender in a US national sample of Hispanic respondents, Allison N. Kristman-Valente and Brian P. Flaherty declare that there are no known conflicts of interest.

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards for research with human participants and was approved by the human subjects review committee of the University of Washington.

Contributor Information

Allison Kristman-Valente, University of Washington

Brian P. Flaherty, University of Washington

References

- 1.Fiore MC. US public health service clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence. Resp Care. 2000;45:1200–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reitzel LR, Costello TJ, Mazas CA, et al. Low-level smoking among Spanish-speaking Latino smokers: Relationships with demographics, tobacco dependence, withdrawal, and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:178–184. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco use among US racial/ethnic minority groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A report of the surgeon general. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years--United States, 2005–2010. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaVeist T. Minority Populations and Health: An introduction to health disparities in the United States. Vol. 4. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2011. Hispanic/Latino health issues; pp. 260–279. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein R. Nation’s population one-third minority. [Accessed February 1, 2015];US Census Bureau News. 2006 May 10; http://www.ime.gob.mx/investigaciones/2006/migracion/Nations%20Population%20One-Third%20Minority.pdf.

- 11.Ennis S, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert N. The Hispanic population: 2010. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez AG, Gallion KJ, Suarez L, et al. A national agenda for Latino cancer prevention and control. Cancer. 2005;103:2209–2215. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, Garza MA. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagan P, Rigotti NA. Light and intermittent smoking: The road less traveled. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:107–110. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furberg H, Sullivan PF, Bulik C, et al. The types of regular cigarette smokers: A latent class analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:351–360. doi: 10.1080/14622200500124917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu SH, Pulvers K, Zhuang Y, Báezconde-Garbanati L. Most Latino smokers in California are low-frequency smokers. Addiction. 2007;102:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults--United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2007;56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Accessed on Fenruary 1, 2015]. pp. 1961–1971. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humble CG, Samet JM, Pathak DR, Skipper BJ. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer in ‘Hispanic’ whites and other whites in New Mexico. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:145–148. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prochazka AV. New developments in smoking cessation. CHEST Journal. 2000;117:169S–175S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4_suppl_1.169s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Stable EJ, Ramirez A, Villareal R, et al. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1424–1430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levinson AH, Pérez-Stable EJ, Espinoza P, Flores ET, Byers TE. Latinos report less use of pharmaceutical aids when trying to quit smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haynes SG, Harvey C, Montes H, Nickens H, Cohen BH. Patterns of cigarette smoking among Hispanics in the United States: results from HHANES 1982–84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:47–53. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns EK, Levinson AH, Lezotte D, Prochazka AV. Differences in smoking duration between Latinos and Anglos. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:731–737. doi: 10.1080/14622200701397882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siahpush M, Singh G, Jones P, Timsina L. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in duration of smoking: results from 2003, 2006 and 2007 Tobacco Use Supplement of the Current Population Survey. J Public Health. 2010;32:210–218. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falcon A, Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW. Latino health policy: Beyond demographic determinism. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Mollina CW, Zambrana RE, editors. Health Issues in the Latino Community. 2001. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alberg AJ, Samet JM. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123:21S–49S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.21s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flanders WD, Lally CA, Zhu B-P, Henley SJ, Thun MJ. Lung Cancer Mortality in Relation to Age, Duration of Smoking, and Daily Cigarette Consumption Results from Cancer Prevention Study II. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6556–6562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns DM. Epidemiology of smoking-induced cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46:11–29. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(03)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans NJ, Gilpin E, Pierce JP, et al. Occasional smoking among adults: evidence from the California Tobacco Survey. Tob Control. 1992;1:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Husten CG, McCarty MC, Giovino GA, Chrismon JH, Zhu B. Intermittent smokers: a descriptive analysis of persons who have never smoked daily. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:86–89. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marcus AC, Crane LA. Smoking behavior among US Latinos: an emerging challenge for public health. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:169–172. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiffman S, Balabanis M, Fertig J, Allen J. Associations between alcohol and tobacco. In: Fertig JB, Allen JP, editors. Alcohol and tobacco: from basic science to clinical practice. Vol. 30. Washington DC: U.S Govt Printing Office; 1995. pp. 17–36. NIAAA Res Monograph. No. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U. S. D. o. H. Services and Human, editor. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Cancer A Report of the Surgeon General. Public Health Service: Office on Smoking and Health; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandhi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg M, Lu SE, Williams J. Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol cigarette smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henningfield JE, Benowitz NL, Ahijevych K, et al. Does menthol enhance the addictiveness of cigarettes? An agenda for research. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:9–11. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000070543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hersey JC, Ng SW, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Are menthol cigarettes a starter product for youth? Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:403–413. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks DR, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Rosenberg L. Menthol cigarettes and risk of lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:609–616. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins CC, Moolchan ET. Shorter time to first cigarette of the day in menthol adolescent cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1460–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muscat JE, Stellman SD, Caraballo RS, Richie JP. Time to first cigarette after waking predicts cotinine levels. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3415–3420. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sias JJ, Urquidi UJ, Bristow ZM, Rodriguez JC, Ortiz M. Evaluation of smoking cessation behaviors and interventions among Latino smokers at low-income clinics in a US–Mexico border county. Addict Behav. 2008;33:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa ML, et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308:1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Center for Health Statistics; N. C. f. H. Statistics, editor. Health in the United States, 2005: With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutfin EL, Reboussin BA, McCoy TP, Wolfson M. Are college student smokers really a homogeneous group? a latent class analysis of college student smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:444–454. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson C, et al. A latent class typology of young women smokers. Addiction. 2007;102:1310–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gariepy G, Malla A, Wang J, et al. Types of smokers in a community sample of individuals with Type 2 diabetes: a latent class analysis. Diabet Med. 2012;29:586–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erickson DJ, Lenk KM, Forster JL. Latent Classes of Young Adults Based on Use of Multiple Types of Tobacco and Nicotine Products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:1056–1062. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Timberlake DS. A latent class analysis of nicotine-dependence criteria and use of alternate tobacco. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:709–717. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Storr CL, Zhou H, Liang K-Y, Anthony JC. Empirically derived latent classes of tobacco dependence syndromes observed in recent-onset tobacco smokers: Epidemiological evidence from a national probability sample survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:533–545. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001696493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Storr CL, Reboussin BA, Anthony JC. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a comparison of standard scoring and latent class analysis approaches. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xian H, Scherrer JF, Eisen SA, et al. Nicotine dependence subtypes: Association with smoking history, diagnostic criteria and psychiatric disorders in 5440 regular smokers from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry. Addict Behav. 2007;32:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Batra A, Collins SE, Torchalla I, Schröter M, Buchkremer G. Multidimensional smoker profiles and their prediction of smoking following a pharmacobehavioral intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.2014 Poverty Guidelines. U.S. Department of Human and Health Services; [Accessed February 1, 2014]. http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clogg CC. Latent class models. In: Arminger G, Clogg CC, Sobel ME, editors. Handbook of statistical modeling for the social and behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Springer; 1995. pp. 311–359. [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCutcheon AL. Latent Class Analysis, No. 64. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flaherty BP. Continuous and Categorical Indicator Latent Class Models [dissertation] State College, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moustaki I. A latent trait and a latent class model for mixed observed variables. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1996;49:313–334. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Socio Meth Res. 1992;21:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flaherty BP. Cigarette Smoking Patterns as a Case Study of Theory-Oriented Latent Class Analysis. In: Scheier LM, editor. Handbook of Adolescent Drug Use Prevention: Research, Intervention Strategies, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. pp. 437–458. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–332. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raftery AE. Bayesian Model Selection in Social Research. Socio Method. 1985;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lando HA, Thai DT, Murray DM, et al. Age of initiation, smoking patterns, and risk in a population of working adults. Prev Med. 1999;29:590–598. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Breslau N, Peterson EL. Smoking cessation in young adults: age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:214–220. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 2005;100:837–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trinidad DR, Pérez-Stable EJ, White MM, Emery SL, Messer K. A nationwide analysis of US racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:699–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piper ME, Welsch SK, Baker TB, Fox BJ, Fiore MC. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in tobacco-dependence treatment: a commentary and research recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:291–297. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woodruff S, Talavera G, Elder J. Evaluation of a culturally appropriate smoking cessation intervention for Latinos. Tob Control. 2002;11:361–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nevid JS, Javier RA. Preliminary investigation of a culturally specific smoking cessation intervention for Hispanic smokers. Am J Health Promo. 1997;11:198–207. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.