Abstract

Rationale

Accurate knowledge of the cellular composition of the heart is essential to fully understand the changes that occur during pathogenesis and to devise strategies for tissue engineering and regeneration.

Objective

To examine the relative frequency of cardiac endothelial cells, hematopoietic-derived cells and fibroblasts in the mouse and human heart.

Methods and Results

Using a combination of genetic tools and cellular markers, we examined the occurrence of the most prominent cell types in the adult mouse heart. Immunohistochemistry revealed that endothelial cells constitute over 60%, hematopoietic-derived cells 5–10%, and fibroblasts under 20% of the non-myocytes in the heart. A refined cell isolation protocol and an improved flow cytometry approach provided an independent means of determining the relative abundance of non-myocytes. High dimensional analysis and unsupervised clustering of cell populations confirmed that endothelial cells are the most abundant cell population. Interestingly, fibroblast numbers are smaller than previously estimated, and two commonly assigned fibroblast markers, Sca-1 and CD90, underrepresent fibroblast numbers. We also describe an alternative fibroblast surface marker that more accurately identifies the resident cardiac fibroblast population.

Conclusions

This new perspective on the abundance of different cell types in the heart demonstrates that fibroblasts comprise a relatively minor population. By contrast, endothelial cells constitute the majority of non-cardiomyocytes and are likely to play a greater role in physiologic function and response to injury than previously appreciated.

Subject Terms: Basic Science Research, Coronary Circulation, Endothelium/Vascular Type/Nitric Oxide, Myocardial Biology

Keywords: Endothelial cell, fibroblasts, leukocyte, flow cytometry, heart, SPADE

INTRODUCTION

While cardiomyocytes account for approximately 25–35% of all cells in the heart1, 2, there is a lack of consensus regarding the composition of the cardiac non-myocyte cell population. In mammals, cardiomyocytes reside in close proximity to capillaries, and the calculated ratio of endothelial cells to cardiomyocytes is 3:13, 4. This estimated number of endothelial cells contradicts studies that have previously characterized heart cellular composition, where findings suggested that fibroblasts constitute the principal non-myocyte cell type1, 2, 5, 6. Often these analyses relied on the expression of singular proteins for identifying specific cell types; this approach may have resulted in exclusion of or loss of distinct cell populations. Because of the incongruence between these data sets and recent advances in our knowledge of heart resident immune cells7, 8, we revisited the issue of cardiac cellular composition. Using newly available genetic tracers and enhanced flow cytometry techniques to analyze the relative abundance of different cell types in the human and mouse heart, we document that fibroblasts comprise a relatively minor cell population and that endothelial cells are the most abundant cell type.

METHODS

Cardiac single cell preparation

Mouse hearts were isolated for single cell preparation as previously described9 with atria and valves removed. Isolated mouse hearts were digested using one of three protocols (designated Protocol 1, 2 and 3). For Protocol 1, each mouse heart was divided in approximately 20 pieces, placed in 10 ml of Protocol 1 digestion buffer [2 mg/ml collagenase type II in 1× HBSS (Worthington Biochemical Corporation)] in gentleMacs C-tubes (Miltenyi Biotec), dissociated using Heart 1 program of a gentleMacs Dissociator, and incubated at 37° C for 40 min with gentle agitation. Following incubation, tissue was further dissociated using Heart 2 program before placing on ice. For Protocol 2, isolated hearts were finely minced using forceps to ~2 mm pieces and placed in 3 ml of Protocol 2 digestion buffer [2 mg/ml collagenase type IV (Worthington Biochemical Corporation) and 1.2 U/ml dispase II (Sigma-Aldrich or Thermofisher Scientific) in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) supplemented with 0.9 mM CaCl2]. Tissue was incubated at 37° C for 15 min with gentle rocking. Following incubation, tissue digestion buffer with tissue clusters was triturated by pipetting 12 times using a 10 ml serological pipette. Dishes were again incubated at 37° C and triturated twice more (45 min of total digestion time). The final trituration was conducted by pipetting 30 times with a p1000 pipette. For Protocol 3, isolated mouse hearts were finely minced using forceps, placed in 10 ml Protocol 3 digestion buffer [125 U/ml collagenase type XI (Sigma-Aldrich), 60 U/ml hyaluronidase type I-s (Sigma-Aldrich), and 60 U/ml DNase 1 (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS supplemented with 0.9 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM HEPES] incubated at 37° C for 1 hour with gentle agitation, triturated 20 times using a 10 ml serological pipette, and placed on ice. All cell suspensions were filtered using a 40 µm cell strainer. Filtered suspensions were placed into 50 ml tubes with 40 ml of DPBS and centrifuged at 200 g for 20 min with centrifuge brakes deactivated to remove small tissue debris. Cell pellets were resuspended in 250 µl 2% FBS/HBSS solution before staining with various antibodies and reagents for flow cytometry or FACS.

Antibody, nuclear and metabolically active cell staining for flow cytometry

Antibody staining for specific antigens (Online Table I) was conducted in 100 µl of single cell suspension (in 2% FBS/HBSS) using Protocols 1, 2, or 3 after FC receptor blocking with CD16/CD32 antibody. Following 1 hour antibody incubation at 4° C, calcein (calcein-AM or calcein-violet; Life Technologies) and/or Vybrant® DyeCycle™ Orange (VDO; Life Technologies) were added to antibody/cell suspensions at final concentrations of 5 and 2.5 µM, respectively. Samples with dyes added were incubated in a 37° C water bath for 10 min, before placing samples on ice. Samples were washed with 2% FBS/HBSS and resuspended in 2% FBS/HBSS with or without the viability dyes DAPI or 7-AAD. All flow cytometry was conducted on LSR II Fortessa Flow Cytometers (BD Biosciences) or LSR II Flow Cytometers (BD Biosciences). For compensation of fluorescence spectral overlap, UltraComp eBeads (eBioscience, Inc.) were used following the manufacturer’s protocols. FCS 3.0 files generated by flow cytometry were initially processed using FlowJo Software (Tree Star, Ashland, USA) for automated compensation. Dye-positive or negative cell populations were gated and exported as new FCS 3.0 files and uploaded to Cytobank Premium for subsequent SPADE analyses. For analysis of total cardiac cells (Figure 2), metabolically active (calcein+), nucleated (VDO+), and viable (DAPI−) events were gated as shown (Figure 2A). Events were gated on viable (7-AAD−) single cells, before gating on CD31+CD45− or CD45+ events for analysis of endothelial cells and leukocytes, respectively (Figure 3A–F). Events were gated on calcein+, viable (7-AAD−), CD31−CD45− events for analysis of resident mesenchymal cells, RMC, (Figure 3G–J; Online Figures V and VI). All SPADE analyses were conducted with the target number of nodes set at 200 or 100 and down-sampled events target set at 100%.

Figure 2. Flow cytometry analysis of cardiac composition.

(A) Gating of nucleated (VDO+), viable (DAPIlo/−), and metabolically active (calcein+) cells with subsequent distribution based on CD31 and CD45 expression. (B) Expression of cell surface markers. (C) Unsupervised cell clustering using SPADE analysis following gating on VDO+DAPIlo/−calcein+ events. Cell clustering based on CD31, CD102, Sca-1, CD45, CD90 and CD11b expression. Dendrogram node color represents relative expression as indicated by heat map. (D) SPADE dendrogram with endothelial cells (ECs), leukocytes (Leuks), and resident mesenchymal cells (RMC) manually annotated. Clustering based on CD31, C102, Sca-1, CD45, CD90 and CD11b expression, following manual gating on nucleated, calcein+ DAPIlo/− cells. (E) Proportions of cells within branches corresponding to ECs, Leuks or RMC identified in the SPADE dendrogram in D (n=8). Heat map indicates level of expression.

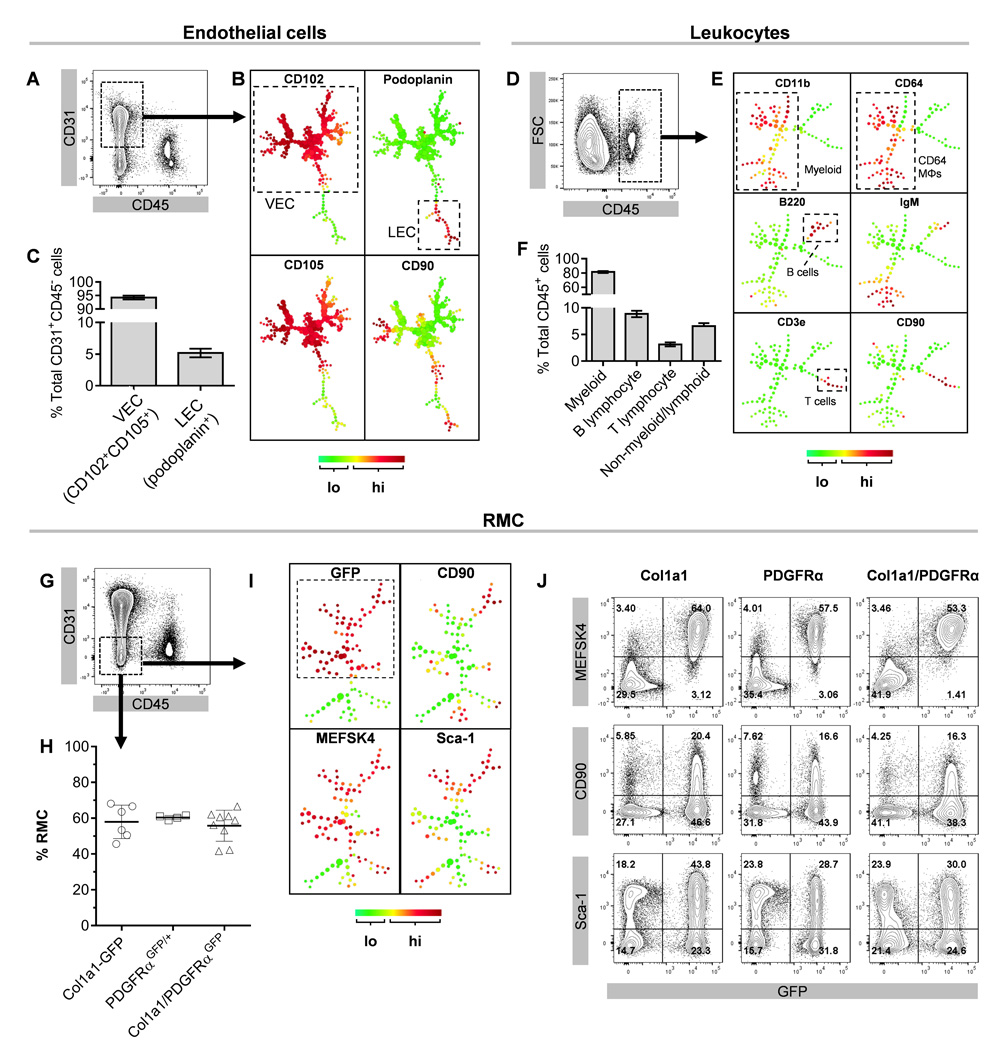

Figure 3. Major cardiac cell subsets.

(A) Representative gating of cardiac CD31+CD45− cells for SPADE analysis. (B) Unsupervised SPADE clustering of CD31+CD45− cells. Cell clustering based on CD102, podoplanin, CD105 and CD90 expression. (C) Proportions of VECs and LECs of total CD31+CD45− cells. (D) Gating of cardiac CD45+ cells for SPADE analysis. (E) Unsupervised SPADE clustering of CD45+ cells. Cell clustering based on CD11b, CD64, B220, IgM, CD3ε and CD90 expression. MΦs, macrophages. (F) Proportions of cardiac leukocytes based on surface marker expression. n=3–4 for 3A–F. (G) Representative gating of cardiac CD31−CD45− cells (RMC) for SPADE analysis. (H) Percent of GFP+ cells in RMC from indicated genotypes (n=6–9). (I) Unsupervised SPADE clustering of RMC from Col1a1-GFP mouse hearts. Cell clustering based on MEFSK4, GFP, CD90, and Sca-1 expression. (J) Contour plots of MEFSK4 staining, CD90, or Sca-1 concomitant with GFP expression in cells from the indicated mice (CD31−CD45− population). All above populations were gated following pre-gating on calcein+ singlet cells that were either DAPI− or 7-AAD−. Heat maps indicate level of expression.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 6 for Windows software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, USA). Statistical variability expressed as means ± SD.

See Online Materials and Methods for additional information.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemical analysis of cardiac cellular composition

To determine the proportions of the major types of non-myocyte cells in the adult murine heart, we conducted histological analysis of cardiac tissue from adult Cx3cr1GFP/+ mice10, which express GFP in monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells including subsets of cardiac tissue macrophages11, 12. In addition to GFP, we stained tissue sections with a hematopoietic lineage antibody cocktail (Lin 1) targeting leukocyte antigens: CD45, Mrc1, B220 and MHC class II, to distinguish a broad cross-section of cardiac leukocytes (Online Figure IA). Cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells were identified by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and isolectin B4 (IB4), respectively. Using this combination of reagents, we were able to examine regional differences in cardiac cellular composition (cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and leukocytes) in both ventricles and the interventricular septum by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1A–B, Online Figures IA and IIA–C). We found approximately 31.0 ± 4.2% of nuclei were cardiomyocytes, 43.6 ± 4.1% endothelial cells, and 4.7 ± 1.5% leukocytes. These proportions remained similar in all regions of the heart (Online Figure IIB). Unmarked cells accounted for approximately 20.7 ± 4.5% of nuclei. When considering only non-myocytes (Online Figure IIC), our analysis indicates that approximately 63.3 ± 5.4% are endothelial cells, 6.8 ± 2.1% are leukocytes, and 29.9 ± 5.9% were unmarked.

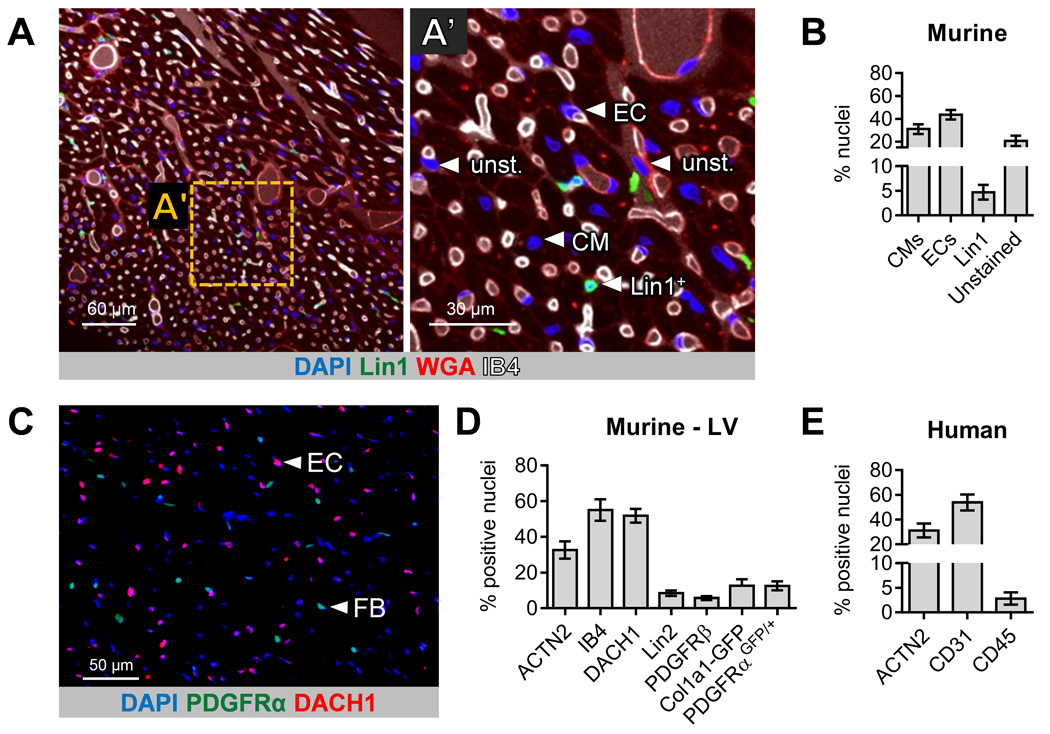

Figure 1. Quantification of major cardiac cell types.

(A) Representative confocal microscopy optical section of cardiac tissue stained from a 10 week old Cx3cr1GFP/+ mouse. (A’) Magnified view of image shown in A. Nuclei (DAPI); cardiomyocyte boundaries (wheat germ agglutinin, WGA); endothelial cells (isolectin B4, IB4); and leukocytes (Lin1 cocktail: GFP, CD45, Mrc1, MHCII and B220). Arrowheads indicate a representative cardiomyocyte (CM), endothelial cell (EC), leukocyte (Lin1+) and unstained cells (unst.). 0.969 µM optical sections. (B) Average proportions from all myocardial regions examined (48 micrographs from 4 hearts). (C) Representative fluorescence microscopy image of cardiac tissue from a PDGFRαGFP/+ mouse stained for DACH1. Arrowheads indicate a representative endothelial cell (EC) and fibroblast (FB). (D) Alternative quantification of cells in mouse left ventricle (LV) with identification of VSMCs/pericytes and fibroblasts. Lin2 cocktail (CD5, CD11b, B220, 7-4, Gr-1, and Ter-119): leukocytes; PDGFRβ: VSMCs/pericytes; IB4: endothelial cells; DACH1: endothelial cell nuclei; α actinin 2 (ACTN2): cardiomyocytes; Col1a1-GFP or PDGFRαGFP: fibroblasts. (E) Quantification of ACTN2+ cardiomyocytes; CD31+ endothelial cells and CD45+ leukocytes in human heart tissue. Data averaged from all quantified myocardial regions (ventricular septum, and left and right ventricles). Tissue from 3 independent, adult, healthy, human heart samples.

As a number of studies have suggested that fibroblasts constitute the majority of non-myocytes in the heart, similar analyses were performed in cardiac tissues from mice containing either a nuclear localized H2B-eGFP expressed from the PDGFRα locus13, PDGFRαGFP, (Figure 1C and Online Figure IB) or GFP driven by a Col1a1 promoter (3.2 kb) and HS 4,5 enhancer (1.7 kb), Col1a1-GFP14. These two mouse lines drive expression of GFP in both epicardial and endocardial lineages of fibroblasts15–17. Using these two strains and focusing on the left ventricle, we independently stained for cardiomyocytes (ACTN2), endothelial cells (IB4 or DACH1), hematopoietic lineage cocktail (Lin 2) which contains anti-CD5, -CD11b, -B220, -7-4, -Gr-1 (Ly6G/C), and -Ter-119 antibodies, and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)/pericytes18 (anti-PDGFRβ) (Figure 1C, Online Figure IB, and data not shown). Approximately 32.6 ± 4.8% of nuclei corresponded to cardiomyocytes, 55.0 ± 6.0% to IB4+ endothelial cells, 5.7 ± 1.1% to VSMCs/pericytes, 8.5 ± 1.5% to leukocytes, and 12.6 ± 2.5%, and 12.7 ± 3.6% to fibroblasts (PDGFRαGFP/+ and Col1a1-GFP mice, respectively; Figure 1D). Because the endothelial values were considerably higher than previous reports5, expression of DACH1 was used as an independent marker for endothelial cells (Figure 1C and D). DACH1 is expressed in the nuclei of coronary vessel endothelial cells (Online Figure IB) but not in endocardial cells19, 20 and therefore, was a reliable marker for quantification of coronary endothelial cells. Figure 1C illustrates the frequency of endothelial cells and fibroblasts relative to other nuclei. DACH1+ endothelial cells constituted 51.8 ± 3.9% of the nuclei. The sum of these data may be greater than 100%, due to inaccuracies in attributing nuclei to cells stained for plasma membrane components. Nonetheless, these independent data sets demonstrate that endothelial cells are the major cell type in the adult murine ventricle. Surprisingly, these results also show that fibroblasts, marked by two unrelated mouse GFP reporter lines, contributed to <20% of total non-myocyte nuclei.

To determine whether human tissue mirrors these findings, we analyzed healthy, adult human heart samples, using antibodies that recognize cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and leukocytes (Figure 1E and Online Figures IC and IID). Unfortunately, none of the antibodies surveyed consistently delineated human resident mesenchymal cells (RMC). Examination of human tissues demonstrated that 31.2 ± 5.6% of nuclei correspond to cardiomyocytes (ACTN2), 53.8 ± 6.4% to endothelial cells (CD31) and 2.8 ± 1.2% to leukocytes (CD45). DACH1 also identified human endothelial cells, and 51.1% ± 2.9% of the nuclei in the human heart were DACH1+ (Online Figure IID). Thus, estimations of endothelial abundance in the human heart reflect those observed in the murine heart.

Flow cytometry analysis of nucleated metabolically active cells

We next performed flow cytometry analysis of single cell preparations as an alternative approach for evaluating cardiac cellular composition. When using conventional methods, a number of technical issues limit the accurate assessment of relative cell proportions by flow cytometry. These issues include the ability to clearly discriminate viable, nucleated cells from tissue debris and cell clusters. Normally, this issue is mitigated by using light-scattering properties of cells such as forward- and side-scatter (FSC and SSC). However, such approaches can skew data regarding the relative proportions of cell types. Therefore, for analysis of relative proportions of broad cardiac non-myocyte cell types (endothelial cells, leukocytes, and RMC), we developed a reliable approach for resolving nucleated cells from tissue debris using Vybrant® DyeCycle™ Orange (VDO), calcein AM (metabolically active cells) and DAPI (cells with compromised membranes) (Online Figure IIIA). To determine the correct gating position for nucleated VDO+ cells within the DAPI−, calcein+ gated population (Online Figure IIIB), we isolated and analyzed cells from 4 regions (R1–4) with differential VDO labeling (Online Figure IIIB–D) by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Microscopy showed that R1 and R4 contained predominantly small cell fragments or clusters, whereas R2 and R3 contained mainly nucleated single cells. Analysis of FSC-H and FSC-A parameters confirmed R1 and R4 comprise small and large elements, respectively; R2 and R3 were cells with a narrower size distribution (Online Figure IIIC). Further analysis of R1 events showed that almost all of these entities are CD31+ and CD105+ (data not shown), indicating that a potentially significant proportion of these entities may be non-nucleated endothelial microparticles (EMPs) or apoptotic bodies21. These results point to reliable criteria for distinguishing dead cells and debris from viable, single cells. However, it should be noted that the VDO component could be replaced by conventional singlet gating with some contamination of R1 and R4 elements. In consideration of the enhanced accuracy conferred by the incorporation of the nuclear-staining dye, we have employed it for flow cytometric survey of all nucleated non-myocytes in the myocardium.

We used this approach to identify a tissue dissociation protocol that yields the greatest number of viable, nucleated cells. Three cardiac single cell suspension protocols with distinct dissociation enzyme cocktails were compared: Protocol 111, Protocol 222, and Protocol 323. The total number of nucleated cells isolated per milligram of tissue was 4241.8 ± 517.4, 11223.3 ± 1194.3, and 6728.9 ± 491.7 for Protocols 1, 2, and 3 respectively (Online Figure IVA). All three protocols demonstrated >95% calcein labeling in nucleated/viable cells (Online Figure IVB). Given the high yield of nucleated/viable cells, we used Protocol 2 for subsequent analyses. It should be noted that during the process of protocol screening we assessed Langendorff perfusion for cell isolation using several commonly referenced digestion cocktails. We found that these methods yielded fewer viable non-cardiomyocytes and contained contamination by valvular interstitial cells (data not shown).

Two identification methods were used to determine if mural cells (such as VSMCs and pericytes) could be recovered from Protocol 2 isolates. To mark VSMCs, we employed a lineage tagging system in a transgenic mouse that expresses Cre controlled by an αSMA promoter (SMACreERT2)24 and a Cre reporter (ROSA26RtdTomato)25. An anti-NG2 antibody was used to identify pericytes26. We found that VSMCs and pericytes could be observed after isolation with Protocol 2 (Online Figure V), suggesting that this population of cells will be included when determining relative cardiac cell proportions.

Cardiac non-myocyte cellular composition

To determine cardiac non-myocyte cell composition, we conducted flow cytometry with antibodies for endothelial cells (CD31 and CD102), leukocytes (CD45 and CD11b) and RMC (CD90 and Sca-1) in addition to nuclear and metabolic activity stains described above. Flow cytometric analyses with manual gating of nucleated, calcein+ cells indicated that CD31+CD45− cells (endothelial cells) constituted 62.1 ± 3.9%, CD45+ cells (leukocytes) 9.6 ± 1.3%, and CD31−CD45− cells (RMC) 27.3 ± 5.3% of all non-myocytes (Figure 2A).

To better define cell populations represented by this antibody panel (Figure 2B), we conducted high-dimensional analysis of our flow cytometry data using the SPADE (Spanning-tree Progression Analysis of Density-normalized Events) algorithm27, 28. SPADE utilizes agglomerative clustering to identify groups of cells (referred to as ‘nodes’) that are phenotypically similar based on multiple surface or genetic markers (described in detail previously28). Schematically, nodes are represented as colored circles that are interconnected within a dendrogram. Direct connection of one node to another signifies phenotypic similarity between the two nodes, and their size represents the number of cells within the node. Node color may indicate a range of statistical parameters. For example, all nodes within the dendrogram may be colored relative to the expression level of specific markers that define cell populations. This enables systematic annotation and categorization of individual nodes or groups of nodes as specific cell types. After annotation, nodes may be selected to derive statistical data, such as relative cell proportion.

Following generation of SPADE dendrograms for cardiac cells using the aforementioned markers (Figure 2B), dendrogram branches corresponding to leukocytes, endothelial cells, and RMC were manually annotated based on marker expression levels (Figure 2C and D). Branches with high CD45 expression, encompassing nodes and branches with high CD11b (myeloid cells) and CD90 (T cells), were classified as leukocytes (Figure 2D). Similarly, branches expressing CD31, CD102 but not CD45 were identified as endothelial cells. Remaining nodes, including nodes with high expression of commonly used fibroblast/mesenchymal markers, Sca-1 and CD90, were classified as RMC. Statistical analysis of SPADE branches identified 63.9 ± 3.4% of cardiac cells as endothelial cells, 9.4 ± 1.6% as leukocytes and 26.7 ± 4.0% as RMC (Figure 2E). These values were consistent with histological analyses described above. Moreover, the SPADE data is consistent with the flow cytometry analyses conducted on nucleated cardiac cells manually gated for endothelial cells (CD31+CD45− cells), leukocytes (CD45+), and RMC (CD31−CD45−) (Figure 2A). Together these findings confirm that endothelial cells are the most prevalent cell type in the adult murine heart.

Endothelial and leukocyte diversity

To determine the diversity of cardiac endothelial cells and leukocytes, we also conducted SPADE analysis following gating on viable, nucleated CD31+CD45− endothelial cells or CD45+ leukocytes. Endothelial cells were clustered based on surface expression of CD102, CD105, podoplanin, and CD90. We found 94.3 ± 0.7% corresponded to vascular endothelial cells (VEC; CD102+CD105+ nodes) and 5.2 ± 0.7% corresponded to lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC; podoplanin+ nodes) (Figure 3A–C). To characterize leukocyte subsets, we clustered CD45+ cells based on surface expression of CD11b, CD64, B220, IgM, CD3ε, and CD90 (Figure 3D and E). Myeloid cells (CD11b+ nodes), B cells (CD11b−B220+ nodes), T cells (CD11b−CD3ε+ nodes), and non-myeloid/lymphoid (CD11b−B220−CD3ε− nodes) cells were clearly identified within dendrograms. Consistent with cell identity, CD64, IgM, and CD90 were highly expressed in nodes corresponding to myeloid cell, B cell, and T cell clusters, respectively. Statistical analysis showed 81.4 ± 1.4%, 8.9 ± 0.6%, 3.1 ± 0.4% and 6.6 ± 0.6% of leukocytes corresponded to myeloid cells (CD11b+), B cells (B220+), T cells (CD3ε+), and non-myeloid/lymphoid cells (CD11b−B220−CD3ε−), respectively (Figure 3F).

RMC composition

While endothelial cells and leukocytes can be identified using a variety of antibodies that recognize surface proteins, reagents for classifying fibroblasts and mural cells (VSMC and pericytes) are limited. Consequently, we attempted to identify uniform and specific antibodies suitable for flow cytometric identification of these two populations. In the murine context, an anti-PDGFRβ antibody would be a candidate for mural cells. Flow cytometry demonstrated that the PDGFRβ monoclonal antibody, APB5, did not label primary cells to a satisfactory level (data not shown for six independent sources), although the same monoclonal antibody can be used for immunohistochemistry.

Unlike the mural cell population, we were able to clearly identify the proportion of RMC that were cardiac fibroblasts by using genetically-tagged Col1a1-GFP, PDGFRαGFP/+ and Col1a1-GFP;PDGFRαGFP/+ transgenic mice that express GFP in resident fibroblasts as described above. By gating upon the CD45−CD31− population, we observed that more than half of the RMC were GFP+ (Figure 3G and H). To determine whether GFP cells from Col1a1-GFP and PDGFRαGFP/+ mice represent similar cardiac cell populations, we conducted SPADE analysis by clustering on CD31, CD102, CD45, CD11b, CD90 and Sca-1. A high degree of overlap occurred when comparing dendrograms for Col1a1-GFP and PDGFRaGFP labeled cells (Online Figure VI).

While cells from the two GFP fibroblast mouse lines were convenient for categorizing and surveying the fibroblast population, use of these transgenic mice as a universal tool to analyze fibroblasts is not always feasible. Because antibodies validated for flow cytometry were readily available for three commonly used fibroblast surface antigens, Sca-1, CD90, and PDGFRα, we surveyed these by flow cytometry. PDGFRα antibodies were assessed on NIH3T3 fibroblasts, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), including PDGFRα null MEFs29, and primary cardiac single cell isolates from wild type and PDGFRαGFP/+ mice. None of the PDGFRα antibodies examined clearly and uniquely distinguished a positive cell population (Online Table I and data not shown), although PDGFRα expression was observed in cardiac fibroblasts by immunohistochemistry (Online Figure VII). Interestingly, following unsupervised SPADE clustering of RMC from Col1a1-GFP mice, we found that most GFP+ nodes were also MEFSK4+ (Figure 3I). Notably, similar correlation of gene expression within these nodes was not observed for CD90 or Sca-1. The MEFSK4 antibody has been used to identify and remove MEFs during culture of induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells. This antibody identifies MEFs from C57BL/6, CF1, CF6, and DR4 mouse strains and an epitope on NIH3T3 cells30. The close correlation of GFP expression and MEFSK4 detection was further underscored when comparing GFP expression to MEFSK4, CD90, or Sca-1 profiles (Figure 3J). Indeed, almost all GFP+ RMC from Col1a1-GFP mice, PDGFRαGFP/+ mice, or Col1a1-GFP;PDGFRαGFP/+ double transgenic mice were MEFSK4+, and most MEFSK4+ RMC were GFP+ (Online Figure VIII). MEFSK4 antigen expression was independent of activation status, as surface staining was not decreased after TGFβ1 stimulation of MEFs or after myocardial infarction (data not shown). It should be noted, however, that the antibody also stains a subpopulation of CD11b+ leukocytes (data not shown). Therefore, this population must be excluded from analysis before considering the fibroblast lineage by flow cytometry. We have not been successful in tissue staining with the MEFSK4 antibody. To further investigate the MEFSK4+ RMC population by flow cytometry, we co-stained for the pericyte marker, NG2. NG2+ cells express the MEFSK4 epitope at lower levels than GFP+ cells, and NG2+ cells account for a majority of the MEFSK4+ GFP− RMC population (Online Figure IX).). To further define MEFSK4+ cells, we isolated CD31−,CD45−, MEFSK4+ cells by FACS and found that fibroblast gene expression is enriched in this cell population compared to whole ventricle (Online Figure X). These findings indicate that Sca-1 and CD90 are suboptimal markers of resident cardiac fibroblasts and that MEFSK4 may be a suitable surrogate marker for cardiac fibroblasts.

Cardiac fibroblast diversity

To further examine the spectrum of fibroblasts labeled by PDGFRαGFP, Col1a1-GFP and MEFSK4, we performed lineage tracing by intercrossing Tcf21iCre/+; ROSA26RtdTomato mice with the fibroblast GFP-expressing mouse lines. In the Tcf21iCre mouse model, resident fibroblasts and their descendants are indelibly tagged with tdTomato fluorescence following Cre induction15,31. We induced Cre-mediated recombination at either embryonic day 16.5 (Tcf21iCre/+;ROSA26RtdTomato;Col1a1-GFP) or in the adult (Tcf21iCre/+; ROSA26RtdTomato;PDGFRαGFP/+) and conducted flow cytometry 2–6 months after induction to determine the proportion of tdTomato+ cells (cardiac fibroblasts) that were GFP+. Gating on the tdTomato+ cells revealed that ~95% were positive for GFP and MEFSK4 (Figure 4 and data not shown), demonstrating that cardiac GFP+ cells from PDGFRαGFP/+ and Col1a1-GFP mice comprise Tcf21 lineage fibroblasts. Taken together, these data suggest that the population of cells identified as fibroblasts is relatively uniform as determined by four independent markers (PDGFRαGFP, Col1a1-GFP, MEFSK4 and Tcf21 lineage). Furthermore, our analysis indicates that this cell population constitutes 15% of the non-myocyte cell pool, equating to ~11% of the total cells of the heart when assuming ~30% of the cells are cardiomyocytes.

Figure 4. MEFSK4 staining and fibroblast GFP expression overlap in Tcf21 lineage fibroblasts.

Flow cytometry contour plots displaying gating of Tcf21 lineage cells (tdTomato+) from (A) Tcf21iCre/+;ROSA26RtdTomato;PDGFRαGFP/+ or (B) Tcf21iCre/+; ROSA26RtdTomato;Col1a1-GFP mice with subsequent analysis of MEFSK4 staining and GFP expression. Cell analysis performed a minimum of 2 months following tamoxifen induction. Representative contour plots.

DISCUSSION

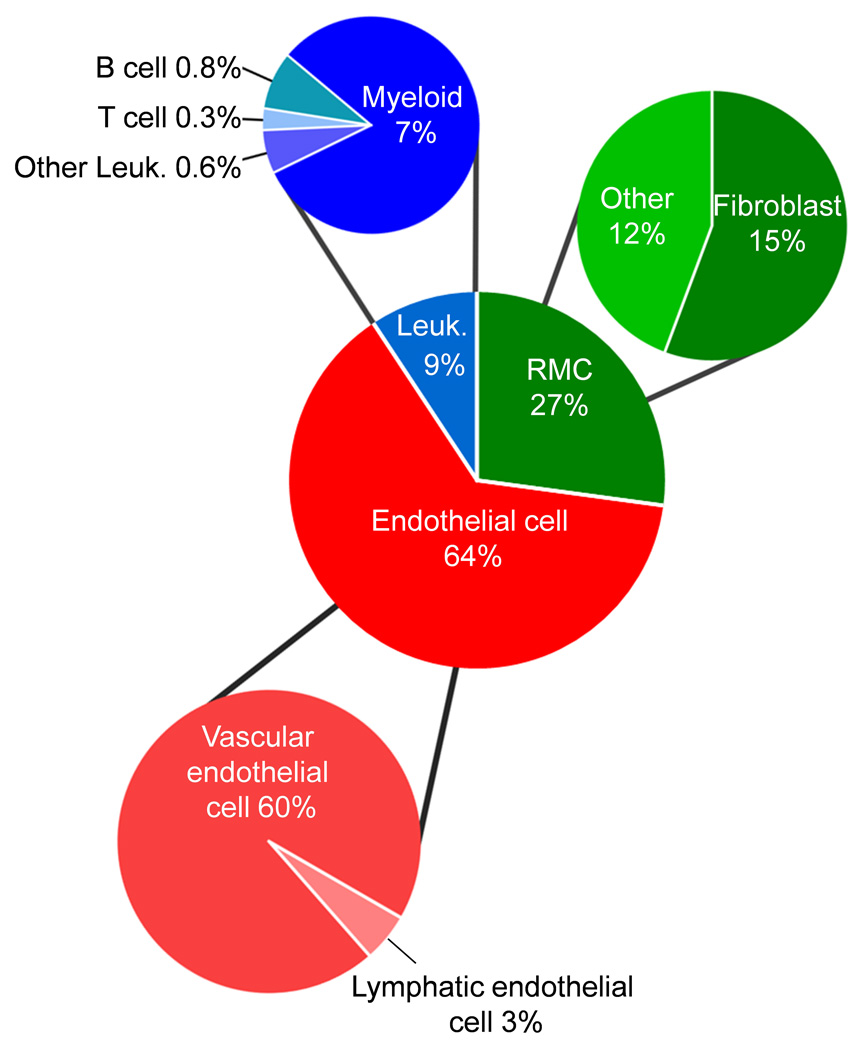

A comprehensive understanding of cardiac cellular composition will guide development of therapeutics that promote heart repair and regeneration. To date, attempts to survey the cellular composition of the heart, even in model organisms such as the mouse and rat, have been hindered by difficulties in cell identification and isolation. Here, using recently developed techniques and genetic tools, we demonstrate that endothelial cells outnumber other cell types in the adult mouse heart ventricles (Figure 5) and that the cardiac fibroblast population is much smaller than previously reported. Nonetheless, classic fibroblast markers such as CD90 and Sca-1 underrepresent the resident fibroblast population.

Figure 5. Distribution of major non-myocyte cardiac cell types.

Combined data demonstrating relative cell numbers determined by flow cytometry with exclusion of cardiomyocytes.

While the accuracy and reliability of immunohistochemical data depends on the specificity and sensitivity of the antibodies used, it can be a powerful approach for evaluating cell populations within a tissue. Here, two histological approaches in separate colonies of mice generated highly analogous results that were further corroborated by the analysis of human tissue sections. Using histological analyses, however, we were unable to evaluate the proportion of myocytes relative to non-myocytes with a high level of precision. This is due to the variability and dynamism of the number of nuclei per cardiomyocyte in addition to the differences between rodents and humans—most murine cardiomyocytes are binucleated32,33, while most human cardiomyocytes are mononucleated2,34. Therefore, estimations of myocyte to non-myocyte ratios will differ depending on the species and age.

There are a number of explanations as to why our findings regarding the number and proportion of endothelial cells in the heart differ from those of previous studies. First, access to new and enhanced reagents enabled more accurate identification of cell populations than was previously possible. Second, use of an isolation protocol that yielded the greatest number of viable cells at the expense of cardiomyocytes may explain why flow cytometry results strongly correlated with results from immunohistochemical analyses but produced different outcomes compared to previous studies2, 5, 35. Many published protocols use digestion conditions that favor the isolation of cardiomyocytes with non-cardiomyocytes being the byproducts of the isolation. Third, establishment of the criteria of cell nucleation and vitality to determine cell frequency enabled us to perform a more accurate analysis. This approach eliminates the dependency on using light-scattering (forward- and side-scatter) properties of cells for identifying viable cells, a practice that could lead to over- or under-representation of cell types and inclusion of tissue debris as cellular events. Fourth, in classifying cell populations we used an unsupervised clustering algorithm (SPADE) following objective cell gating. SPADE and similar clustering algorithms enable superimposition of expression data for multiple cellular markers to visualize and quantify non-myocyte cardiac cell populations. The identity of endothelial cells was confirmed using multiple endothelial markers including CD31, CD102, and CD105, in addition to exclusion of leukocyte markers CD45 and CD11b.

While the recovery of cell populations and flow cytometry data presented here correlates with the cellular distribution documented by immunohistochemistry, the possibility remains that not all cells have been included in the current assessment. These may include cells that are more sensitive to the digestion protocol or are not recovered due to insufficient digestion. Notably, we have not tested the efficacy of the nuclear and metabolic activity (VDO and calcein) staining approach to distinguish between activated, proliferating, and quiescent cell populations.

The discrepancy in leukocyte proportions determined by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry may be attributed to inefficiencies in antigen detection in fixed tissues. Indeed, this is likely for leukocyte staining using anti-CD45 antibodies, which do not reveal stellate-shaped myeloid cells in fixed human or mouse tissue. Utilizing antibody cocktails for staining mouse cardiac tissue may overcome this issue; nevertheless, immunohistochemical analyses of leukocytes may still fail to detect all cells. By flow cytometry analysis— focusing on nucleated metabolically active cells and SPADE—we have estimated that leukocytes comprise approximately 7–10% of all non-myocytes. The vast majority of these cells were identified as myeloid cells and, in particular, macrophages. A number of lymphocytes were also detected, although at a much lower prevalence.

Histologic and flow cytometric analysis also suggests that the relative number of fibroblasts in the heart may have been over-estimated in the past. The lack of a clear definition for fibroblasts has been at the root of many difficulties in quantifying and tracking these cells in vivo. In some cases, cardiac fibroblasts have been quantified by excluding cells that lack structural elements corresponding to endothelial cells, VSMCs, or cardiomyocytes1. According to this definition, pericytes and leukocytes would also be classified as fibroblasts. Another confounding factor is that markers such as DDR2, CD90, Sca1, and vimentin are not unique to fibroblasts, and not all fibroblasts express these proteins. While resident cardiac fibroblasts derive from two embryonic sources, the consensus is that PDGFRα is expressed in both populations. The utility of CD90 for identification of fibroblasts, on the other hand, remains a point of debate17,35. Previously, we have shown that cardiac Tcf21 lineage cells, and GFP+ cells from PDGFRαGFP and Col1a1-GFP mouse hearts have similar levels of fibroblast gene expression including Col3a1, Col6a1, Dcn, and MMP2 with lack of expression of smooth muscle, endothelial, and cardiomyocyte genes15. As flow cytometric results demonstrate that the MEFSK4 antibody detects Tcf21 lineage cells, and GFP+ cells from PDGFRαGFP and Col1a1-GFP mouse hearts, and surface staining by the MEFSK4 antibody correlates with GFP-expressing cells when excluding leukocytes, this antibody can used to identify cardiac fibroblasts by flow cytometry when use of the genetic systems is not feasible. Our results also suggest that CD90 and Sca1 only capture a fraction of the resident fibroblasts. This analysis represents the most comprehensive estimation of cardiac fibroblasts to date.

Recent reports have proposed that pericytes contribute significantly to the cardiovascular remodeling process36,37. In the uninjured heart, we show that these cells account for approximately 5% of non-cardiomyocytes and that they also express MEFSK4, albeit at lower levels compared to fibroblasts. Further investigation will be required to determine MEFSK4 expression in the activated pericyte population. The establishment of these cellular proportions at baseline will pave the way for future work examining how these populations vary in the postnatal, aged, and injured heart.

Although the role of the endothelial cell as a dynamic regulator of tissue responses is increasingly recognized, their abundance and roles in the heart are commonly underappreciated. The proximity of endothelial cells to the coronary circulation and cardiomyocytes provides an access point for therapeutic manipulation. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of these potential cellular interactions will be required. Taken together, our findings redefine the cellular composition of the adult murine and human heart and point to the cardiac endothelial cell as a potentially important protagonist in cardiac homeostasis, disease, and aging.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

While cardiomyocytes constitute the vast majority of cardiac cell mass, non-cardiomyocytes account for the majority of cells in the heart.

Non-cardiomyocytes are diverse and include fibroblasts, endothelial cells, leukocytes, smooth muscle cells, and pericytes.

The prevailing view is that fibroblasts are the most abundant non-cardiomyocyte cell type in the heart.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Endothelial cells outnumber all other cell types in the heart, comprising greater that 60% of the non-cardiomyocyte cells.

Fibroblast numbers are lower than previous estimates and constitute less than 20% of the non-cardiomyocyte cells.

Accurate characterization of the cell types found in the heart is essential for understanding cardiac development, homeostasis, aging, and injury responses. This study provides the first comprehensive survey of major cell types found in the human and mouse heart and their relative abundance. We find that endothelial cells are the most abundant cell type in both the mouse and human heart and that fibroblasts comprise a much smaller proportion of non-cardiomyocyte cells than previously thought. In addition, we demonstrate a standardized approach for identifying cell types in the heart that permits simultaneous surveying of multiple non-cardiomyocyte cell populations. The findings of this study fundamentally redefine our understanding of the cellular composition of the heart and may have implications for studies concerned with cardiac cellular biology in a range of developmental and disease contexts.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by Stem Cells Australia, a grant from the Australian Research Council and a Grant-in-Aid (G 12M 6627) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants [HL074257, HL100401 to M.D.T.]; [F31HL126512 to M.J.I]; and an Institutional Cardiology Training Grant [T32 HL115505 to J.T.K.]. The University of Hawaii Biorepository was supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grants [U54MD007584 and G12MD007601] and a National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant [P20GM103466]. The Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute is supported by grants from the State Government of Victoria and the Australian Government. N.R. is a National Health and Medical Council Australia Fellow.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- αSMA

α smooth muscle actin

- CM

cardiomyocyte

- EC

endothelial cell

- EMP

endothelial microparticles

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- FSC-A

forward scatter-area

- FSC-H

forward scatter-height

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IB4

isolectin B4

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cell

- Lin

lineage

- LV

left ventricle

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MHC class II

major histocompatibility complex class II

- RMC

resident mesenchymal cells

- SPADE

spanning-tree progression analysis of density-normalized events

- VDO

Vybrant® DyeCycle™ Orange

- VEC

vascular endothelial cell

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nag AC. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: A fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios. 1980;28:41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Bernard S, Sjostrom SL, Szewczykowska M, Jackowska T, Dos Remedios C, Malm T, Andra M, Jashari R, Nyengaard JR, Possnert G, Jovinge S, Druid H, Frisen J. Dynamics of cell generation and turnover in the human heart. Cell. 2015;161:1566–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brutsaert DL. Cardiac endothelial-myocardial signaling: Its role in cardiac growth, contractile performance, and rhythmicity. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:59–115. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsieh PC, Davis ME, Lisowski LK, Lee RT. Endothelial-cardiomyocyte interactions in cardiac development and repair. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:51–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.124629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Price RL, Borg TK, Baudino TA. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1883–H1891. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souders CA, Borg TK, Banerjee I, Baudino TA. Pressure overload induces early morphological changes in the heart. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1226–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frieler RA, Mortensen RM. Immune cell and other noncardiomyocyte regulation of cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Circulation. 2015;131:1019–1030. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto AR, Godwin JW, Rosenthal NA. Macrophages in cardiac homeostasis, injury responses and progenitor cell mobilisation. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13:705–714. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto AR, Chandran A, Rosenthal NA, Godwin JW. Isolation and analysis of single cells from the mouse heart. J Immunol Methods. 2013;393:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor cx(3)cr1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinto AR, Paolicelli R, Salimova E, Gospocic J, Slonimsky E, Bilbao-Cortes D, Godwin JW, Rosenthal NA. An abundant tissue macrophage population in the adult murine heart with a distinct alternatively-activated macrophage profile. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto AR, Godwin JW, Chandran A, Hersey L, Ilinykh A, Debuque R, Wang L, Rosenthal NA. Age-related changes in tissue macrophages precede cardiac functional impairment. Aging (Albany NY) 2014;6:399–413. doi: 10.18632/aging.100669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton TG, Klinghoffer RA, Corrin PD, Soriano P. Evolutionary divergence of platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor signaling mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4013–4025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.4013-4025.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yata Y, Scanga A, Gillan A, Yang L, Reif S, Breindl M, Brenner DA, Rippe RA. Dnase i-hypersensitive sites enhance alpha1(i) collagen gene expression in hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:267–276. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acharya A, Baek ST, Huang G, Eskiocak B, Goetsch S, Sung CY, Banfi S, Sauer MF, Olsen GS, Duffield JS, Olson EN, Tallquist MD. The bhlh transcription factor tcf21 is required for lineage-specific emt of cardiac fibroblast progenitors. Development. 2012;139:2139–2149. doi: 10.1242/dev.079970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith CL, Baek ST, Sung CY, Tallquist MD. Epicardial-derived cell epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fate specification require pdgf receptor signaling. Circ Res. 2011;108:e15–e26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.235531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore-Morris T, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Banerjee I, Zambon AC, Kisseleva T, Velayoudon A, Stallcup WB, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Cedenilla M, Gomez-Amaro R, Zhou B, Brenner DA, Peterson KL, Chen J, Evans SM. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2921–2934. doi: 10.1172/JCI74783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armulik A, Genove G, Betsholtz C. Pericytes: Developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Dev Cell. 2011;21:193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gay L, Miller MR, Ventura PB, Devasthali V, Vue Z, Thompson HL, Temple S, Zong H, Cleary MD, Stankunas K, Doe CQ. Mouse tu tagging: A chemical/genetic intersectional method for purifying cell type-specific nascent rna. Genes Dev. 2013;27:98–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.205278.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen HI, Sharma B, Akerberg BN, Numi HJ, Kivela R, Saharinen P, Aghajanian H, McKay AS, Bogard PE, Chang AH, Jacobs AH, Epstein JA, Stankunas K, Alitalo K, Red-Horse K. The sinus venosus contributes to coronary vasculature through vegfc-stimulated angiogenesis. Development. 2014;141:4500–4512. doi: 10.1242/dev.113639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dignat-George F, Boulanger CM. The many faces of endothelial microparticles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:27–33. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.218123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ieronimakis N, Hays AL, Janebodin K, Mahoney WM, Jr, Duffield JS, Majesky MW, Reyes M. Coronary adventitial cells are linked to perivascular cardiac fibrosis via tgfbeta1 signaling in the mdx mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;63:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galkina E, Kadl A, Sanders J, Varughese D, Sarembock IJ, Ley K. Lymphocyte recruitment into the aortic wall before and during development of atherosclerosis is partially l-selectin dependent. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1273–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wendling O, Bornert JM, Chambon P, Metzger D. Efficient temporally-controlled targeted mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells of the adult mouse. Genesis. 2009;47:14–18. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, Lein ES, Zeng H. A robust and high-throughput cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozerdem U, Grako KA, Dahlin-Huppe K, Monosov E, Stallcup WB. Ng2 proteoglycan is expressed exclusively by mural cells during vascular morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:218–227. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir el AD, Krutzik PO, Finck R, Bruggner RV, Melamed R, Trejo A, Ornatsky OI, Balderas RS, Plevritis SK, Sachs K, Pe'er D, Tanner SD, Nolan GP. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu P, Simonds EF, Bendall SC, Gibbs KD, Jr, Bruggner RV, Linderman MD, Sachs K, Nolan GP, Plevritis SK. Extracting a cellular hierarchy from high-dimensional cytometry data with spade. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews A, Balciunaite E, Leong FL, Tallquist M, Soriano P, Refojo M, Kazlauskas A. Platelet-derived growth factor plays a key role in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2683–2689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knoebel S, Kurtz A, Schwarz C, Eckardt D, Barral S, Bossio A. Novel fibroblast-specific marker for rapid, efficient removal of MEFs from stem cell cultures by magnetic separation. Abstract. ISSCR. 2010:1256. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song K, Nam YJ, Luo X, Qi X, Tan W, Huang GN, Acharya A, Smith CL, Tallquist MD, Neilson EG, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soonpaa MH, Kim KK, Pajak L, Franklin M, Field LJ. Cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and binucleation during murine development. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2183–H2189. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.5.H2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li F, Wang X, Capasso JM, Gerdes AM. Rapid transition of cardiac myocytes from hyperplasia to hypertrophy during postnatal development. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:1737–1746. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mollova M, Bersell K, Walsh S, Savla J, Das LT, Park SY, Silberstein LE, Dos Remedios CG, Graham D, Colan S, Kuhn B. Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1446–1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214608110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ali SR, Ranjbarvaziri S, Talkhabi M, Zhao P, Subat A, Hojjat A, Kamran P, Muller AM, Volz KS, Tang Z, Red-Horse K, Ardehali R. Developmental heterogeneity of cardiac fibroblasts does not predict pathological proliferation and activation. Circ Res. 2014;115:625–635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson NC, Arnold TD, Katamura Y, Giacomini MM, Rodriguez JD, McCarty JH, Pellicoro A, Raschperger E, Betsholtz C, Ruminski PG, Griggs DW, Prinsen MJ, Maher JJ, Iredale JP, Lacy-Hulbert A, Adams RH, Sheppard D. Targeting of alphav integrin identifies a core molecular pathway that regulates fibrosis in several organs. Nat Med. 2013;19:1617–1624. doi: 10.1038/nm.3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, Machado F, Fleig S, Bondzie PA, Henderson JM, Ebert BL, Humphreys BD. Perivascular gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.