Abstract

Objective

To study national-level trends in ART treatments and outcomes, as well as the characteristics of women who have sought this form of infertility treatment.

Design

CDC registry data of clinics and pooled data from three cycles (1995, 2002, and 2006–10) of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a repeated nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of women aged 15–44 years.

Setting

Population based.

Patients

CDC: All reporting clinics from 1996–2010. NSFG: For the logistic analysis, the sample includes 2,325 women aged 22–44 who have ever used medical help to get pregnant, excluding women who used only miscarriage prevention services.

Interventions

None.

Main Outcome Measures

CDC data: number of cycles, live birth deliveries, live births, patient diagnoses. NSFG data: individual utilization of ART procedures.

Results

Between 1995 and 2010, utilization of ART increased. Parity and age are strong predictors of utilizing ART procedures; other correlates are higher education, having had tubal surgery, and having a current fertility problem.

Conclusions

The two complementary data sets highlight the trends of ART utilization. Increase in the utilization of ART services over this time period is seen in both data sources; nulliparous women aged 35–39 are the most likely to have ever used ART services.

Keywords: ART utilization, ever use of medical help to get pregnant, ART cycles, live birth deliveries, births

The percentage of women aged 15–44 in the United States who have ever used infertility services increased from 9 percent in 1982 to 15 percent in 1995, then in 2002 declined to 12 percent, and remained at that level in 2006–10 (1, 2). Although the number and percentage of women utilizing assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has increased consistently over this time period, the number of births resulting from an ART procedure remains low at 1 percent or less of all births. In 2011, 0.7 percent of all births in the United States were a result of in vitro fertilization and related techniques, based on birth certificate data from 27 states and the District of Columbia (2, 3).

Previous analyses have shown that women who make use of medical help for infertility tend to be a highly select group, which may reflect the fact that women of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to have adequate health insurance coverage and other financial resources to afford the necessary diagnostic or treatment services (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). We anticipate that women who utilize ART are an even more select group given the expense and duration of treatment, and limited insurance coverage for ART.

Our goal in this paper is to provide a better understanding of the supply and demand of assisted reproductive technologies in the United States. We use national clinic-based data to look at the supply of services through trends in diagnoses, procedures, and outcomes of provider-reported ART cycles from 1999–2010 and nationally-representative data of women aged 22 and over to investigate individual demand and self-reported use of infertility services. By utilizing data from two sources, our analyses illuminate the national-level trends in ART treatments and outcomes, as well as the characteristics of women who have sought this form of infertility treatment.

METHODS

CDC Data

The first set of analyses use published and unpublished data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act (FCSRCA, or Public Law 102–493) passed in 1992 mandates that all ART clinics report success rate data to the federal government in a standardized manner. Starting in 1996 the CDC partnered with the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies (SART) to obtain data from fertility medical centers located in the United States (and its territories) on ART cycles including patient medical history and infertility diagnoses, clinical information pertaining to the ART procedure, and information regarding resultant pregnancies and births, as well as limited demographic information on the patient. In 2004 CDC started development on the National ART Surveillance System (NASS) with a contract to Westat, Inc. This model builds on previous data collection systems and implements CDC model standards for surveillance, and in 2006 NASS was launched. The CDC continues a partnership with the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and SART, who are involved in collecting and reporting data from member clinics. In spite of the federal mandate, not all clinics report data; across the years approximately 90 percent of all clinics reported data representing approximately 95 percent of all cycles. The data file contains one record per ART procedure performed; consequently, multiple procedures from a single patient are not linked (11). The terms CDC data and clinic-based data will be used in this analysis to refer to the data across time. The data prior to 2006 are commonly known as CDC/SART data; the data from 2006 on are from the NASS data collection system.

The medical director of each clinic verifies the accuracy of success rates. The CDC samples reporting clinics each year to validate the data. Site visits are made to clinics where medical records are reviewed for a sample of the patients (12).

Clinic-based data allow us to determine trends at the national level of the methods of ART that are being used--such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), and zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT)--in addition to diagnoses, numbers of cycles, and resulting live births. Data for cycles and outcomes are available starting in 1996. We use 2010 as the end date to correspond with the timing of the cross-sectional data of the second data source. The diagnoses categories changed in 1999 from earlier years, so data from 1999–2010 are used for that portion of this analysis.

Infertility diagnoses are given for one factor in one partner or multiple factors in one or both partners. If multiple factors exist then those factors are not detailed:

tubal factor --- the woman’s fallopian tubes are blocked or damaged, causing difficulty for the egg to be fertilized or for an embryo to travel to the uterus;

ovulatory dysfunction --- the ovaries are not producing eggs normally; such dysfunctions include polycystic ovarian syndrome and multiple ovarian cysts;

diminished ovarian reserve --- the ability of the ovary to produce eggs is reduced; reasons include congenital, medical, or surgical causes or advanced age;

endometriosis --- tissue similar to the uterine lining is growing in abnormal locations in the abdominal cavity; this condition can affect both fertilization of the egg and embryo implantation;

uterine factor --- a structural or functional disorder of the uterus is resulting in reduced fertility;

male factor --- a low sperm count or problems with sperm function are causing difficulty for a sperm to fertilize an egg under normal conditions;

other causes of infertility --- immunologic problems or chromosomal abnormalities, cancer chemotherapy, or serious illnesses;

unexplained cause --- no cause of infertility was detected in either partner;

multiple factors, female --- diagnosis of one or more female cause; or

multiple factors, male and female --- diagnosis of one or more female cause and male factor infertility (13).

Cycles include fresh non-donor, frozen non-donor, fresh donor, and frozen donor cycles.

NSFG Data

The second set of analyses utilizes data from the 1995, 2002, and 2006–2010 National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG), conducted by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm). Each of these surveys is a multistage probability-based survey that is representative of the national household population of women aged 15–44 in the United States (since 1973) and men (since 2002), and includes oversamples of Hispanics, Blacks, and teens aged 15–19. The NSFG is conducted in respondents’ homes using in-person interviews. It is designed to yield nationally representative estimates for the household-based (non-institutionalized) population of men and women 15–44 in the U.S. on a wide range of topics related to fertility, family formation, and reproductive health. All data gathered from respondents are self-report only; no biological or clinical data are collected from respondent or their health care providers. Further details on the methodology and design of the NSFG have been published elsewhere (14, 15, 16). All analyses presented in our paper are based on weighted data, using the fully adjusted, post-stratified case weights, and variances are estimated using SAS version 9.2 Survey procedures to account for the complex survey design features of the NSFG (www.sas.com).

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides financial support through Project Number AHD12020001-1-0–1. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approval was obtained for the NSFG protocols for 2002 (#2002-02) and 2006–2010 (#2006–01).

The 2002 NSFG response rate for women was 80 percent, and for 2006–2010 NSFG, it was 78 percent. Like all population-based, voluntary surveys, the NSFG sample includes individuals who choose not to participate in the survey or cannot be contacted at all, despite considerable effort to locate them at home. These nonresponse rates have increased over recent decades across all surveys for a number of broader societal reasons such as busier schedules, locked buildings precluding access to selected respondents, and greater reluctance to participate in surveys.

In keeping with the methods in earlier NSFG-based studies of infertility services, we use age 22 as a lower bound for our sample. This threshold allows for all individuals in the analysis to have potentially completed college or entered their first marriage or cohabiting union (17, 18, 19). Based on data from the 2006–10 NSFG Manning et al. found that the median age at first union for women was 22.2 years; median age at first marriage was 26.5 years and first cohabitation was 21.8 years (20). The age restriction to 22 also improves the reliability of reports of two key variables in this analysis: household income measured as a percent of poverty level and current fertility problems (21).

Our sample includes women aged 22–44 who have ever used infertility services, and then we restrict our sample to women aged 22–44 who sought medical help to get pregnant. The sample does not include women who used only miscarriage prevention services, although some analyses of infertility services do include both types of medical help.

NSFG Analysis plan

We utilize logistic regression to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios associated with covariates for the use of ART services using a pooled data set for 1995, 2002, and 2006–10. The pooled data set allows us to assess the net effect of time period on the odds of ever having used ART after controlling for any compositional changes in the population.

The dependent variable for our logistic analysis is a binary variable indicating whether the woman ever used ART versus only using other types of medical help to become pregnant, which could include advice, infertility testing, artificial insemination (including intrauterine or intracervical insemination); surgery for blocked tubes, endometriosis, fibroids; or ovulation-inducing drugs (without any ART or insemination component). We limited our analysis to those women who ever used medical help to get pregnant for two reasons. First, we wanted to look at the possible role of private health insurance in covering such costs and that question was only asked of women who reported using medical help to get pregnant. Second, we focus on distinguishing women who used ART from those who used other less-costly forms of medical help to get pregnant.

We selected variables for binary logistic regression modeling based on bivariate associations with this dependent variable and findings from prior research. Survey year is included with 1995 as the reference category. The correlates of service use included in the analysis are: age, parity, education, marital/cohabitation status, income, race and Hispanic origin, private health insurance to cover the costs of medical help to get pregnant, whether the woman ever had tubal surgery, and whether the woman has current fertility problems.

Age and parity are shown as a combined term, with a reference category of parous women 22–29 years of age, based on evidence that all other groups are generally more likely to have ever used medical help to get pregnant than this reference group. Age is shown in 5-year categories, except for the youngest age group (22–29) since there are fewer women below age 30 who report or are aware of fertility impairments. For the purposes of this composite variable, parity has been dichotomized as 0 for nulliparous women and 1 for women with one or more births. This allows us to distinguish women who definitely used services prior to any live births from those who may or may not have done so (because data on service use in the NSFG do not permit ascertainment of relative timing).

Marital/cohabitation status at interview includes informal union status, as well as whether a woman is currently married, with the latter group as the reference group. This distinction allows us to determine if women who are currently cohabiting use ART at the same levels as married women or if they are more similar to other unmarried women.

Education and income as a percent of poverty level are dichotomous variables, with break points based on previous research showing significant relationships with use of infertility services. Education is dichotomized at a Bachelor’s (4-year) degree or higher. Household income is dichotomized at 400 percent of poverty level income or higher, which was equivalent to $39,732 for a two-person household in 1995 and $58,408 for a two-person household in 2010 (22, 23).

Race/ethnicity is defined as Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic other, with non-Hispanic whites as the reference category.

Our variable representing insurance coverage is specific to whether the respondent had private insurance coverage to cover the medical costs for getting pregnant. This question was asked in all three NSFG surveys included in this analysis. This question is a yes/no item, worded as follows: “Did either of you have private health insurance to cover any of the costs of medical help for becoming pregnant?” This question is only asked of female respondents who answered yes to an initial question about ever using medical help to get pregnant.

The tubal surgery variable is included as a proxy variable for tubal factor infertility, which has traditionally been a primary indication for ART. Respondents reporting that they have had tubal surgery are coded as yes, with no as the reference category for the logistic model. Thus, the coefficient for the tubal surgery variable will represent the effect of the condition most directly and specifically indicating a medical need for ART.

The final variable included in the logistic analysis is a composite measure indicating current fertility problems. This variable is coded yes if the woman has either 12-month infertility or impaired fecundity, which are the two standard measures of fertility problems defined by the NSFG. Twelve-month infertility is defined for married or cohabiting women only, and indicates they have had no pregnancy in at least 12 consecutive months of unprotected intercourse with their current husband or partner. Impaired fecundity, the second NSFG-based measure of fertility problems, is defined for all women regardless of relationship status and recent coital and contraceptive patterns, and encompasses problems with pregnancy loss as well as with conception. Trends for these two separate measures of fertility problems have been published elsewhere (19, 24, 25, 26, 27). Although the composite measure reflects current status, the impaired fecundity component in particular may represent a continuing perception based on past experience of being unsuccessful in conceiving or carrying to term without medical assistance, even if overcome at some point with medical assistance. Past research has found a strong correlation of current fertility problems, especially impaired fecundity, with ever-use of infertility services.

RESULTS

Supply of Services: the CDC clinic data

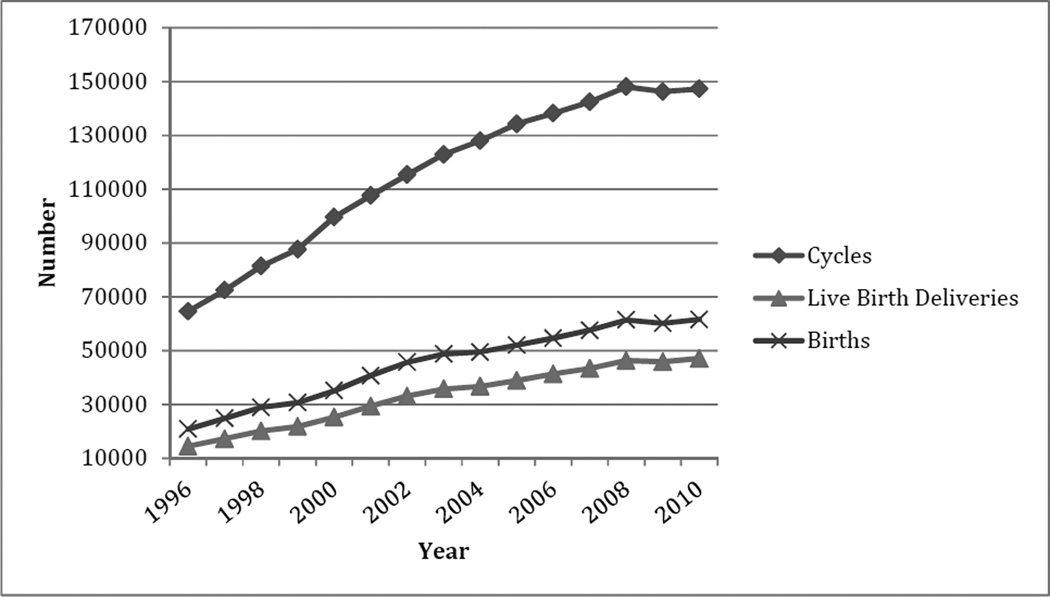

Figure 1 shows the aggregate number of cycles started for all reporting clinics, as well as the live birth deliveries and live births for 1996–2010 (28). The live births exceed the deliveries because of the high rate of multiples among ART births; for instance in 2009, 47.4 percent of all ART births were twins or higher order multiples (29). Between 1996 and 2010, the number of cycles slightly more than doubled, from 64,583 to 147,260, while live birth deliveries and total births tripled, from 14,538 to 47,090 and from 20,870 to 61,564 respectively. The increases in the late 1990s for all three measures slowed in the late 2000s, with a plateau effect from 2008 to 2010.

Figure 1.

Cycles, live birth deliveries, and births: 1996–2010

Two competing goals of ART are captured by these data. The first is the maximization of live birth deliveries, and the second is the maximization of singleton births. Because of the concern over adverse birth outcomes for multiple-births, a healthy singleton birth is the ideal outcome for an ART procedure. However because treatments are expensive and often are not covered by insurance plans, one approach to increase the potential success of any one cycle leading to a live birth is to transfer multiple embryos during an in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure. As the percentage of multiple births increased among ART births, however, and the percentage of low birthweight babies increased, the guidelines on the ideal number of embryos transferred were revised downward four times between 2004 and 2009 by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (30, 31, 32, 33). In 2011 the ASRM Practice Committee declared that the most direct way to limit the risk of multiple gestations from ART is to transfer a single embryo at a time (34). The difference in practice of embryo transfer from 1996 to 2010 is evident; the mode decreased from 4+ embryos (62 percent) in 1996 to 2 embryos (53 percent) in 2010 (35, 36). In 1996, 16 percent of transfers were of 1 or 2 embryos and by 2010 over two-thirds (68 percent) of transfers were of 1 or 2 embryos.

The second factor of note over time is the differences among diagnoses. For instance tubal factors declined from 16 percent in 1999 to 7 percent in 2010, while diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) more than doubled from 7 percent in 1999 to 15 percent in 2010.

To investigate whether the increase in the representation of DOR patients was driven by increases the composition of the patient population who had delayed their childbearing to older ages, we examined the relative distribution of cycles by age for patients and patients with a DOR diagnosis under the age of 40. The definition of DOR in the Federal Register Notice and used in NASS during the study years states that all women 40 years of age and older should be reported as having DOR. This complicates interpretation of the age distribution of women aged 40 and over with a DOR diagnosis, thus we limit our analysis to women under the age of 40. We also examined the age distribution of cycles among patients with a DOR diagnosis who used donor eggs because this patient population might otherwise be turned away from ART using their own eggs because of a small likelihood of success. Donor egg offers physicians a way to keep DOR patients in the ART treatment group.

Although the number of cycles of patients with DOR more than tripled from 1999 to 2010, the age pattern remained fairly stable, with a predominance in the 35–39 age group (Table 1). In 1999 and 2010 68 percent and 69 percent (respectively) of cycles for a DOR diagnosis were for women aged 35–39. The percentage of ART cycles to women with DOR who used donor egg also is most prevalent among the 35–39 age group. We show the total number of cycles for women aged 40 and over in the far right column of this table, but because of the coding problem noted above, the percentage distribution is for women younger than 40.

Table 1.

Percentage distribution and number of women by broad age groups of all ART cycles, cycles for women with a diminished ovarian reserve diagnosis, and cycles for women with a diminished ovarian reserve diagnosis who used donor oocytes: 1999 and 2010

| All cycles | <=29 | 30–34 | 35–39 | Total Number aged <=39 |

Total number aged >=40 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 14.96 | 39.80 | 45.24 | 68,288 | 19,348 | |

| 2010 | 14.77 | 38.50 | 46.73 | 107,563 | 39,697 | |

| DOR diagnosis | ||||||

| 1999 | 5.82 | 26.62 | 67.56 | 5,086 | 7,917 | |

| 2010 | 5.55 | 25.01 | 69.44 | 17,622 | 24,088 | |

| DOR diagnosis, with Donor oocytes | ||||||

| 1999 | 6.14 | 26.46 | 67.40 | 1,678 | 4,233 | |

| 2010 | 5.95 | 23.33 | 70.72 | 3,330 | 9,860 | |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ART Report, National Summaries for 1999 and 2010, and written communication with the Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August 2013.

We now turn to the individual-level, self-reported data from the NSFG to determine population trends in the utilization of ART and other medical help to get pregnant.

Demand for Services: NSFG Data

Table 2 shows the population-based percentages of reports of ever use of specific types of infertility services among all women aged 22–44, and the distribution across the subgroup of women who ever sought medical help to get pregnant. Women could and generally did report using multiple services.

Table 2.

Percentage of women aged 22–44 who have ever used infertility services and percentage of women aged 22–44 who sought medical help to get pregnant by type of service, United States: 1995, 2002 and 2006–10 National Survey of Family Growth

| Infertility services | Women aged 22–44 | Women aged 22–44 who sought medical help to get pregnant |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2002 | 2006–2010 | 1995 | 2002 | 2006–2010 | |

| Total | 18.8 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Medical help to get pregnant | 10.6 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Advice | 7.9 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 76.9 | 73.8 | 74.8 |

| Infertility testing (male or female) | 2.5 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 51.7 | 57.4 | 58.1 |

| Female testing | 4.7 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 45.4 | 52.8 | 50.5 |

| Male testing | 3.9 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 37.5 | 43.2 | 44.2 |

| Ovulation drugs | 3.8 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 36.8 | 45.3 | 46.1 |

| Surgery or treatment for blocked tubes | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 18.0 | 8.6 | 10.1 |

| Artificial insemination (incl. intrauterine) | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 13.5 |

| Assisted reproductive technology | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 5.2 |

Source: NSFG (1995, 2002, 2006–10).

Note: Women could report as many services that they ever used, thus the columns do not add to 100.

The percentage of women aged 22–44 who have ever used ART was 0.1 percent in 1995 and 0.6 percent in 2006–10. In absolute numbers this is an increase from about 50,000 women aged 15–44 in 1995 to 280,000 women in 2006–10. Similarly in the CDC clinic data, we observed the nearly 2.5-fold increase in ART cycles performed over this time period, while the number of facilities reporting data increased from 315 in 1996 to 443 in 2010.

When the sample is limited to women aged 22–44 who had ever used medical services to get pregnant, the percentage who ever had ART increased from 1.0 percent in 1995 to 5.2 percent in 2006–10. The percentage of women who had surgery or treatment for blocked tubes decreased from 18 percent in 1995 to 10 percent in 2006–10, which mirrors the findings from the CDC clinic data indicating that the tubal factor diagnoses had decreased from 16 percent in 1999 to 7 percent in 2010.

Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the logistic analysis modeling ever-use of ART relative to all other types of medical help to get pregnant. The unadjusted odds ratios are included for comparison purposes; the discussion of the table focuses on the adjusted odds ratios, which reflect adjustment for all variables shown in the table.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for having ever used ART procedures among women aged 22–44 who ever used medical help to get pregnant, United States: 1995, 2002, 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth

| Characteristic | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Parity and age | ||

| 0 births/22–29 years | 2.78 (0.23–33.06) | 1.32 (0.11–15.98) |

| 0 births/30–34 years | 22.67 (2.88–178.33)** | 12.72 (1.62–99.77)* |

| 0 births/35–39 years | 44.20 (5.51–355.11)** | 21.32 (2.25–201.74)** |

| 0 births/40–44 years | 35.74 (4.75–269.16)** | 12.80 (1.53–107.17)* |

| 1 or more births/22–29 years (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1 or more births/30–34 years | 7.17 (0.91–56.75) | 3.97 (0.49–32.05) |

| 1 or more births/35–39 years | 17.73 (2.78–112.99)** | 9.36 (1.48–59.34)* |

| 1 or more births/40–44 years | 19.073 (2.67–136.51)** | 11.80 (1.69–82.28)* |

| Marital or cohabiting status | ||

| Currently married (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Currently cohabiting | 0.09 (0.01–0.60)* | 0.15 (0.02–1.21) |

| Not currently married or cohabiting | 0.78 (0.35–1.73) | 0.94 (0.39–2.25) |

| Education | ||

| Less than a bachelor’s degree | 0.32 (0.18–0.58)** | 0.43 (0.24–0.80)** |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Private insurance coverage to cover medical costs for getting pregnant | ||

| Yes | 1.17 (0.63–2.16) | 1.06 (0.51–2.22) |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Percent of poverty level | ||

| Less than 400 percent of poverty level | 0.50 (0.27–0.91)* | 0.75 (0.36–1.54) |

| 400 percent or higher (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Survey year | ||

| 1995 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2002 | 3.13 (1.40–6.99)** | 3.83 (1.55–9.38)** |

| 2006–10 | 5.44 (2.51–11.79)** | 7.28 (3.13–16.95)** |

| Ever had tubal surgery | ||

| Yes | 3.66 (2.08–6.42)** | 4.27 (2.06–8.85)** |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 0.50 (0.20–1.25) | 0.87 (0.36–2.11) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.67 (0.21–2.14) | 0.64 (0.20–2.01) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1.27 (0.52–3.14) | 0.78 (0.24–2.57) |

| Non-Hispanic White (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Current fertility problem | ||

| Yes | 2.37 (1.23–4.55)** | 2.23 (1.10–4.53)* |

| No (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Model summary | ||

| Unweighted n | 2325.0 | |

| Approximate chi-square (df) | 733.78** (19) |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Source: NSFG (1995, 2002, 2006–10).

Note: Adjusted odds ratios reflect adjustment for all other variables shown in this table.

Parity and age are very strong correlates of ART ever-use. Nulliparous women aged 35–39 are 21 times more likely to have ever used ART than parous women aged 22–29, with nulliparous women aged 30–34 and 40–44 nearly 13 times more likely to have used ART. Among women with at least one child, women aged 35–39 were 9 times as likely to have used ART and women aged 40–44 nearly 12 times as likely to have used ART as parous women aged 22–29.

Women with less than a bachelor’s degree were less than half as likely to have utilized ART services as women with at least a bachelor’s degree. Women who have had tubal surgery are four times as likely and women with a current fertility problem are twice as likely to have used ART services than are their reference groups. The former is logical because blocked tubes (rather than DOR) is the traditional indication for ART. The latter suggests a general increase in the use of ART above and beyond the period effects that are captured by the survey year indicators. Also of interest is the survey year variable, which mirrors trends in ART cycles from the CDC clinic data. Women in 2002 were nearly 4 times more likely to have used ART and women in 2006–10 were over 7 times more likely to have ever used ART than women in 1995.

Although we had hypothesized that there would be an effect of insurance and income on utilization of ART services, the net effects are not significant for these two variables as seen in the right-hand column of Table 3.

DISCUSSION

These two data sets document the increased number of clinics and the correlates of ART users in the United States over the past two decades. As a result of increasingly refined ART treatment options that are available to women and couples, live birth deliveries and births have increased three-fold over the same time period that the number of cycles increased two-fold, despite the reduction in the modal number of embryos transferred.

Although ART remains a small percentage of overall infertility service use among women aged 22–44, the increase may reflect more options that are available to patients: significant laboratory, clinical, and technological advances leading to higher success rates, a greater variety of payment plan options, increased number and geographic distribution of clinics, and comprehensive insurance mandates in some states. Our multivariate analysis of the odds of having ever used ART, relative to other medical help to get pregnant, highlights the importance of parity and age, as well as educational attainment, experience with tubal surgery, and whether the respondent has current fertility problems. Nulliparous women aged 35–39 have the highest odds of having ever used ART in comparison with parous women aged 22–29. Although we had expected that having private health insurance for medical costs for getting pregnant would be significantly associated with ART use, it showed no net effect after controlling for the other variables among women who did receive some form of medical help to get pregnant. The larger issue behind why this variable does not show an unadjusted or adjusted effect on the odds of having used ART may be that the comparison can only be made with those who used other types of medical help to get pregnant. The private insurance coverage question was not asked unless the woman reported using some form of medical help to get pregnant, and the effect of such coverage may be seen primarily with use of any such medical help, relative to none. Survey year was highly significant, net of the other control variables, indicating that women in 2006–10 were seven times as likely to have utilized ART as women in 1995 who reported medical help to get pregnant.

Additionally, the association with current fertility problems is of note because many of these respondents are reporting retrospectively on past treatments, some of which may have resulted in live births. Further analyses could explore whether these women were disproportionately unsuccessful in their treatment experience or were successful yet continue to meet the definition of these fertility impairments at time of interview. The relevant period on which older women in the 1995 sample are reporting could have occurred in the previous decade when assisted reproductive technologies were less developed and available. Thus, some of the increase may be an effect of changing times both in terms of technology and social acceptability of these procedures.

The strength of this analysis is the utilization of two data sources to examine both the supply and demand for ART services. The two data sources should be seen as complementary, with each having its own strengths and weaknesses. The CDC clinic data allow us to see trends at the national level, based on clinic/provider-based data. However, the clinic-based data utilize ART cycles rather than women, so we cannot make any population-based estimates for women or couples. Also the clinic-based data contain very limited demographic characteristics of women undergoing ART. Another limitation of the data is that approximately 90 percent--but not 100 percent of the clinics--report data each year, although it is estimated that the reporting clinics represent 95 percent of the ART procedures in any given year because non-reporting clinics tend to be small (e.g., perform fewer cycles).

The NSFG data provide nationally representative data on women aged 15–44 so we are able to make population-based estimates of how many women have ever used specific services, including ART services, rather than the number of cycles as in the CDC clinic-based data. Because of the consistency of measures in the NSFG surveys over time, we were able to pool the 1995, 2002, and 2006–10 data sets to have a large enough sample for a multivariate analysis of ART service use at the individual level. However, the restriction to women aged 44 years and younger in the NSFG data excludes women aged 45 and over who may utilize ART services and who would be included in the CDC/SART data.

The trends in the CDC clinic-based data echo through the NSFG data. The number of clinics included the CDC reports increased from 301 in 1996 to 443 in 2010—a 47 percent increase—while the numbers of cycles more than doubled between 1996 and 2010, and the number of live birth deliveries and births tripled in that same time period. We cannot compare the NSFG numbers directly to the CDC clinic-based increases since the NSFG are for women and for ever-use rather than being reported on an annual basis, but the percentage of all women aged 22–44 who have ever used ART increased over six-fold from 1995 to 2006–10.

There are some findings from this research that will require additional analyses. For instance, while we do not have data in the two sources that perfectly match in terms of diagnoses, we observe in both a decrease in the representation of tubal factor infertility. Kawwass also found a decrease in the prevalence of tubal factor infertility between 2000 and 2010 using the NASS (37). One possibility suggested by this decline is that the increase in reported chlamydia rates at the national level may result in earlier treatment leading to fewer long-term complications that might result in tubal-factor infertility (38). Another interpretation is that providers are moving patients with other diagnoses more quickly and frequently into ART. Recent studies suggest that fast-tracking certain groups of patients to IVF results in optimal outcomes (39, 40, 41).

Likewise we had expected that the increase in DOR noted in the CDC clinic-based data was indicative of delayed childbearing, which is evident over the past several decades in the United States, and which has contributed to a larger population seeking to become pregnant in their late 30s and 40s when fecundity is decreasing (42, 43). However, we did not find any obvious changes in the age distribution of patients across ART cycles, which may be a result of the definition of DOR used during this time period, even when we refine the sample to women with DOR and who used donor oocytes. Another possibility for the increase in the diagnosis may be more refined testing for the detection of DOR or earlier testing of women who are seeking to become pregnant.

Although there are unanswered questions, this analysis highlights the increasing demand for and supply of ART. An understanding of both clinic-level and individual-level data is critical in order to have a more complete picture of access to this specialized form of medical care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Sheree Boulet, Amy Branum, Rebecca Clark, Jennifer Madans, Hanyu Ni and Samuel Posner for valuable and critical comments on the paper. Dmitry Kissin of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided additional data not available in published reports. The East-West Center and Georgetown University provided space and time for the first author to complete the paper. Katrina Kleck and Rachel Ryu provided research assistance.

The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) conducts the National Survey of Family Growth, one of the primary data sources for this analysis. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides financial support through Project Number AHD12020001-1-0-1. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approval was obtained for the NSFG protocols for 2002 (#2002-02) and 2006–2010 (#2006-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 27th International Population Conference, Busan, South Korea, August 26–30, 2013.

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the organizations at which they are employed. The authors have no financial considerations or involvements for this paper.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Hervey Stephen, Georgetown University

Anjani Chandra, CDC/National Center for Health Statistics

Rosalind Berkowitz King, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development

Reference

- 1.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982–2010. Natl Health Stat Reports. 2014;(73) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Flowers L, Anderson JE, Folger SG, Jamieson DJ, Barfield WD. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance — United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012 Nov;61:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thoma ME, Boulet S, Martin JA, Kissin D. Births resulting from assisted reproductive technology: comparing birth certificate and national ART Surveillance System Data, 2011. Natl Vital Stat Reports. 2014 Dec 10;63(8) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Stephen EH. Infertility service use among U.S. women 1995 and 2002. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greil AL, McQuillan J, Shreffler KM, Johnson KM, Slauson-Blevins KS. Race-ethnicity medical services for infertility: stratified reproduction in a population-based sample of U.S. women. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(4):493–509. doi: 10.1177/0022146511418236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huddleston HG, Cedars MI, Sohn SH, Giudice LC, Fujimoto VY. Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;202(5):413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Missmer SA, Seifer DB, Jain T. Cultural factors contributing to health care disparities among patients with infertility in Midwestern United States. Fertil Steril. 2011 May;95(6):1943–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nachtigall RD. Fertil Steril. 4. Vol. 85. Webb NJ: Staniec JFO; 2006. Apr, International disparities in access to infertility services; pp. 871–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vahratian A. Utilization of infertility services: How much does money matter? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3):971–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00640.x. Part 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vahratian A. Utilization of fertility-related services in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(4):1317–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright VC, Schieve L, Reynolds MA, Jeng G, Kisin D. Assisted reproductive surveillance—United States, 2001. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004 Apr;53:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed May 22, 2015];National ART surveillance. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/art/NASS.htm.

- 13.Wright VC, Chang J, Jeng G, Macaluso M. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance--United States 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepkowski J, Mosher WD, Davis K, Groves RM, van Hoewyk J, Willem J. National Survey of Family Growth, cycle 6: sample design, weighting, imputation, and variance estimation. Vital Health Stat. 2006;2(142) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepkowski JM, Mosher WD, Groves RM, West BT, James Wagner J, Haley Gu H. Responsive design, weighting, and variance estimation in the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2013;2(158) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groves RM, Mosher WD, Lepkowski J, Kirgis NG. Planning and development of the continuous National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2009;1(48) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copen CE, Daniels K, Vespa J, Mosher WD. First marriages in the United States: data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Reports. 2012;(49) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copen CE, Daniels K, Mosher WD. First premarital cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Reports. 2013;(64) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodwin P, McGill B, Chandra A. Who marries and when? Age at first marriage in the United States: 2002. NCHS data brief. 2009;(19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manning WD, Brown SL, Payne KK. Two decades of stability and change in age at first union framework. J Marriage Fam. 2014;76:247–260. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Reports. 2013;(67) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baugher E, Lamison-White L. Current Population Reports P60–194. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1996. Poverty in the United States: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60–239. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2011. Appendix B of income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p60-239.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of US Women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2005;23(25) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandra A, Mosher WD. The demography of infertility and the use of medical care for infertility. Infertil Reprod Med Clin North Am. 1993;52(2):283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra A, Stephen EH. Impaired fecundity in the United States: 1982–1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(1):34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosher WD, Pratt WF. Fecundity and infertility in the United States, 1965–1988. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics. 1990:192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Analyses of the National ART Surveillance System (NASS) data. Written communication with the Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2013 Aug [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Flowers L, Anderson JE, Folger SG, Jamieson DJ, Barfield WD. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance — United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012 Nov;61:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on the number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(Suppl 1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on the number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(Suppl 5):S51–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on the number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(Suppl 3):S163–S164. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on the number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1518–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Multiple gestation associated with infertility therapy: an ASRM Practice Committee Opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:825–834. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2005 Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2010 Assisted Reproductive Technology National Summary Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawwass JF, Crawford S, Kissin DM, Session DR, Boulet S, Jamieson DJ. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jun;121(6):1263–1271. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31829006d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control. Chlamydia screening percentages reported by commercial and Medicaid plans by State and Year. http://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/female-enrollees-00-08.htm.

- 39.Goldman MB, Thornton KL, Ryley D, Alper MM, Fung JL, Hornstein MD, Reindollar RH. A randomized clinical trial to determine optimal infertility treatment in older couples: the Forty and Over Treatment Trial (FORT-T) Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1574–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaser DJ, Goldman MB, Fung JL, Alper MM, Reindollar RH. When is clomiphene or gonadotropin intrauterine insemination futile? Results of the fast track and standard treatment trial and the Forty and Over Treatment Trial, two prospective randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1331–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.07.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reindollar RH, Regan MM, Neumann PJ, Levine BS, Thornton KL, Alper MM, Goldman MB. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate optimal treatment for unexplained infertility; the fast track and standard treatment (FASTT) trial. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:888–899. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Delayed childbearing: more women are having their first child later in life. NCHS Data Brief. 2009 Aug;(21) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db21.pdf. [PubMed]

- 43.Sharara FI, Scott RT, Seifer DM. The detection of diminished ovarian reserve in infertile women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:804–812. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]