Abstract

Second-harmonic generation (SHG) originates from the interaction between upconverted fields from individual scatterers. This renders SHG microscopy highly sensitive to molecular distribution. Here, we aim to take advantage of the difference in SHG between aligned and partially aligned molecules to probe the degree of molecular order during biomechanical testing, independently of the absolute orientation of the scattering molecules. Toward this goal, we implemented a circular polarization SHG imaging approach and used it to quantify the intensity change associated with collagen fibers straightening in the arterial wall during mechanical stretching. We were able to observe the delayed alignment of collagen fibers during mechanical loading, thus demonstrating a simple method to characterize molecular distribution using intensity information alone.

Main Text

Many cardiovascular diseases have been linked to altered mechanical functions in arteries (1). Understanding their pathomechanics and developing treatments require a deeper understanding of the interplay between the mechanical properties at the tissue level and the extracellular matrix (ECM) organization at the microstructural level, a multi-scale problem. Collagen fibers are one of the principal ECM components involved in arterial wall mechanics and can be imaged label-free with second-harmonic microscopy (2). Extracting structural information, however, involves time consuming analysis of multiple second-harmonic images (3). Recently, circularly polarized nonlinear optics was shown to have the ability to quantify molecular symmetry after the acquisition of a minimal number of images using exclusively intensity information (4). We therefore set out to explore if circularly polarized illumination can be exploited to quantify the molecular alignment in arterial collagen with a single image during mechanical loading.

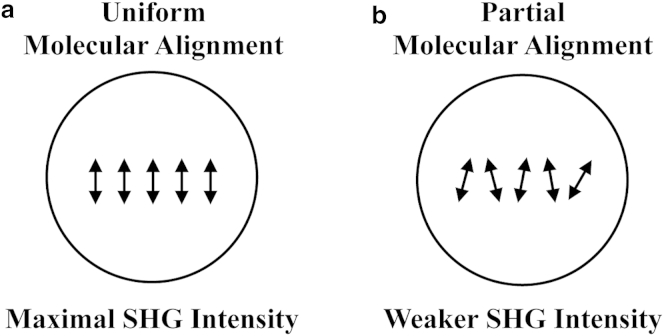

Second-harmonic scattering of a single molecule is a coherent parametric process during which the energy of two incident photons at frequency is redirected to a single photon at frequency . The coherence of second-harmonic scattering implies that the generated light depends on both the amplitude and the phase of the incident field. Thus, when multiple scatterers are present, the second-harmonic fields will interfere together and generate an often complex radiation pattern. This is second-harmonic generation (SHG). For a given distribution, the SHG signal is maximal when all scattering molecules possess the same orientation (Fig. 1 a) (5, 6). In biomedical applications, observing a perfect alignment of molecules is unlikely. Even highly organized structures, such as cell membranes or collagen fibrils, are likely to have some angular distribution in their dipole orientation (Fig. 1 b), resulting in weaker SHG signal.

Figure 1.

The intensity originating from second-harmonic fields depends on molecular alignment for any incident polarization state. (a) The SHG signal is maximal if all molecules are aligned. (b) Partial alignment of molecules results in weaker SHG signal.

The above discussion implies that changes in molecular organization on the scale of the phase coherence length can be monitored by intensity measurements alone. The dynamics of dye reorientation within lipid bilayers was previously followed using the variation in second-harmonic intensity relative to two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF) (5). The relative gain or loss in SHG signal was quantified using: . During mechanical stretching of arterial tissue, collagen fibers are known to straighten (3). This alignment of collagen is expected to lead to changes in the molecular orientation, hence changes in . Here, our goal is to demonstrate that such changes in can be detected during the deformation of arteries, thus enabling the characterization of fiber engagement with simple normalized intensity measurements.

Second-harmonic imaging was performed on a custom laser scanning microscope described in detail elsewhere (7). Collagen was imaged at 30 frames/s with 25 mW from a mode-locked Ti:sapph laser at 800 nm (Maitai-HP, Spectra-Physics, Santa Clara, CA) through a 60X objective lens (NA1.0 W, LUMPlanN, Olympus, Waltham, MA) (3). Circular polarization of the illumination light was obtained by placing a quarter-wave plate just before the objective. The polarization was verified to be maintained at the focus by rotating mouse tail tendons and imaging spherical cells (NALM6, a leukemic cell line) labeled with Di-8-ANEPPS (, n=60) (8). Imaging was performed on the adventitia, the external portion of arterial walls, of excised pig aorta down to a depth of 60 μm. Arteries (n = 6) were placed on a stretching device according to standard testing procedures (3).

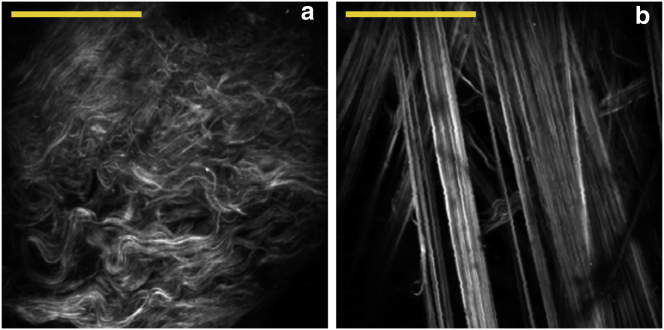

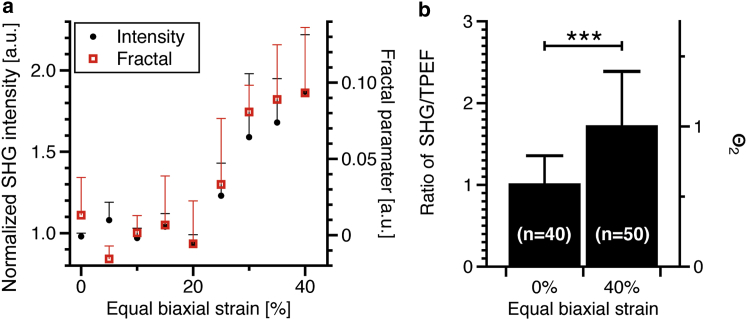

To test for changes in second-harmonic intensity, we imaged freshly excised aorta under equal biaxial strains from 0 to 40% with 5% increments at multiple random locations (nine regions over a 1 cm2 area). The strain was always equal biaxial (i.e., the same in the longitudinal and circumferential direction) and defined as , where is the unstretched tissue length and is the length at strain i. Using this approach, together with a manual measurement of fiber waviness or an automated fractal analysis (3), we previously reported a delayed realignment of adventitial collagen. Collagen fibers are highly wavy at 0% strain (Fig. 2 a) but are completely straight at 40% (Fig. 2 b). The adventitial collagen undergoes large structural changes that can be characterized with direct biophysical measurements, making it an ideal site to validate new experimental strategies. Analyses were performed on maximum intensity projection images of axial stacks over 110 × 110 μm regions. For image intensity measurements, a fixed threshold of 10 on a 8-bit scale was used to isolate all fibers, and the average image intensity was calculated using only pixels where fibers were present. This procedure ensured that the amount of fibers did not bias the intensity evaluation. Fig. 3 a shows that the intensity was constant between 0 and 20% strain. The increase in intensity >20% strain revealed the same delayed fiber recruitment, as described previously, without the need to perform tedious manual measurements or employ advanced image analysis methods.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the engagement of collagen fibers during mechanical loading by systematic random imaging. Second-harmonic images of adventitial collagen at strains of (a) 0% and (b) 40% showing fiber straightening (scale bar, 180 μm, 30 frames average).

Figure 3.

Collagen fibers straightening. (a) The fractal analysis from Chow et al. (3) and the normalized intensity measurement both show delayed collagen fiber realignment (n = 6). (b) The ratio between SHG and TPEF intensity in collagen fiber bundles stained with fluorescein was evaluated at strains of 0 and 40%. Mann-Whitney U-test with ∗∗∗.

Tissue stretching in the longitudinal and circumferential axes also impacts the radial thickness (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). Therefore, the absolute depth of objects could be altered by volumetric deformation (i.e., collagen fibers might become more superficial). To verify if the increased was due to volumetric deformation, was compared to , a fully incoherent process. For this purpose, arteries were incubated at 4°C overnight in a PBS solution containing fluorescein, which possesses a strong TPEF cross section. After imaging, the SHG and TPEF intensities were evaluated in individual collagen fiber bundles at strains of 0, 20, and 40% by cropping 18 × 18 μm regions. The SHG intensity from each region was then normalized to the TPEF signal from fluorescein. A significant increase in the SHG/TPEF ratio was observed at 40% strain, but not 20% (Fig. 3 b). This indicates that the increase in SHG intensity is associated with changes in molecular organization and not volumetric deformation.

The information on the molecular distribution within a nonlinear excitation volume can be obtained using polarimetric second-harmonic imaging (9, 10). By acquiring multiple images with a linearly polarized illumination with different orientation, the nonlinear susceptibility tensor can be probed ( and ) using:

| (1) |

where (see Supporting Material for the derivation of Eq. 1) (11, 12, 13). is a bulk property and dependent on molecular arrangement. It is usually assumed that the susceptibility of individual molecules remains unchanged. Effective changes in susceptibility are instead attributed to an increase or decrease molecular order. This method was previously applied to mechanical testing on tendons and shown to be sensitive to collagen fiber straightening and alignment (10, 14). To link our relative intensity measurement to polarimetric imaging, we derived an expression equivalent to Eq. 1 for circularly incident illumination (see Supporting Material):

| (2) |

When a strain of 40% is applied on an artery, collagen fibers are fully aligned, and it can be assumed that the second-harmonic signal is maximal. The relative decrease in intensity at lower strain can therefore be expressed as:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Polarimetric second-harmonic imaging has the advantage of providing absolute values for , but the imaging speed is limited by the need to acquire multiple images at a single location and to control the incident light polarization (15). In contrast, our intensity measurement with circular polarization provides relative values at greater imaging speed and experimental simplicity, eliminating the need to acquire multiple images at different polarizations. It should be possible to implement the method for intravital imaging applications of rapidly deforming tissue, such as arteries and contracting muscles (16).

Our method relies critically on the circularly polarized excitation beam. Because this polarization will not be maintained after propagation in tissue, only the most superficial layer of collagen was analyzed in this work. This was accomplished by taking the maximum intensity projection of the image stack. More sophisticated methods requiring full polarimetry will be needed to account for altered polarization due to birefringence and diattenuation when imaging deeper into tissue (10, 17).

In summary, we demonstrate a method for characterizing mechanical functions of arterial collagen at the molecular level with single SHG images acquired with circularly polarized light. During tissue stretching, we observed an increase in second-harmonic intensity, attributable to increased molecular order and directly related to changes in the nonlinear susceptibility tensor of the material (Eq. 4). The SHG intensity with circularly polarized light is not sensitive to the absolute orientation of the scatterers, thus enabling characterization of their relative degree of order with a single image per tissue state. Finally, we believe that the simplicity of our approach will enable characterization of tissue properties in several biomedical applications, especially when fast image acquisition is required.

Author Contributions

R.T., J.M.M., and J.W.W. performed the experiments. R.T., Y.Z. and C.L.P. wrote the manuscript and designed the experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ming-Jay Chow for his help with mechanical testing.

This work is supported in part by NIH grant Nos. U01 HL099997 (to C.L.P.) and NIH R01 HL098028 (to Y.Z.). R.T. was supported by a FRQNT PhD Fellowship and a Wellman Center for Photomedicine Graduate Student Fellowship.

Editor: Andrew McCulloch

Footnotes

Supporting Mathematical Derivation and one figure are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)00002-3.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Safar M.E., O’Rourke M.F., Frohlich E.D. Springer-Verlag; London: 2014. Blood Pressure and Arterial Wall Mechanics in Cardiovascular Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zoumi A., Lu X., Tromberg B.J. Imaging coronary artery microstructure using second-harmonic and two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2778–2786. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow M.-J., Turcotte R., Zhang Y. Arterial extracellular matrix: a mechanobiological study of the contributions and interactions of elastin and collagen. Biophys. J. 2014;106:2684–2692. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duboisset J., Rigneault H., Brasselet S. Filtering of matter symmetry properties by circularly polarized nonlinear optics. Phys. Rev. A. 2014;90:063827. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreaux L., Sandre O., Mertz J. Coherent scattering in multi-harmonic light microscopy. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mertz J. Roberts and Company Publishers; Greenwood Village, CO: 2009. Introduction to Optical Microscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veilleux I., Spencer J.A., Lin C.P. In vivo cell tracking with video rate multimodality laser scanning microscopy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. 2008;14:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X., Nadiarynkh O., Campagnola P.J. Second harmonic generation microscopy for quantitative analysis of collagen fibrillar structure. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:654–669. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campagnola P.J., Dong C.-Y. Second harmonic generation microscopy: principles and applications to disease diagnosis. Laser Photonics Rev. 2011;5:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gusachenko I., Tran V., Schanne-Klein M.C. Polarization-resolved second-harmonic generation in tendon upon mechanical stretching. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2220–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butcher P.N., Cotter D. Cambridge University Press; London: 1990. The Elements of Nonlinear Optics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plotnikov S.V., Millard A.C., Mohler W.A. Characterization of the myosin-based source for second-harmonic generation from muscle sarcomeres. Biophys. J. 2006;90:693–703. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen W.L., Li T.H., Dong C.Y. Second harmonic generation χ tensor microscopy for tissue imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;94:2007–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goulam Houssen Y., Gusachenko I., Allain J.M. Monitoring micrometer-scale collagen organization in rat-tail tendon upon mechanical strain using second harmonic microscopy. J. Biomech. 2011;44:2047–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bélanger E., Turcotte R., Côté D.C. Maintaining polarization in polarimetric multiphoton microscopy. J. Biophotonics. 2015;8:884–888. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201400116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Psilodimitrakopoulos S., Loza-Alvarez P., Artigas D. Fast monitoring of in-vivo conformational changes in myosin using single scan polarization-SHG microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2014;5:4362–4373. doi: 10.1364/BOE.5.004362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gusachenko I., Latour G., Schanne-Klein M.C. Polarization-resolved Second Harmonic microscopy in anisotropic thick tissues. Opt. Express. 2010;18:19339–19352. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.019339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.