Abstract

Tuberculosis of the pancreas is extremely rare and in most of the cases mimics pancreatic carcinoma. There are a number of case reports on pancreatic tuberculosis with various different presentations, but only a few case series have been published, and most of our knowledge about this disease comes from individual case reports. Patients of pancreatic tuberculosis may remain asymptomatic initially and manifest as an abscess or a mass involving local lymph nodes and usually present with non-specific features. Pancreatic tuberculosis may present with a wide range of imaging findings. It is difficult to diagnose tuberculosis of pancreas on imaging studies as they may present with masses, cystic lesions or abscesses and mass lesions in most of the cases mimic pancreatic carcinoma. As it is a rare entity, it cannot be recommended but suggested that pancreatic tuberculosis should be considered in cases with a large space occupying lesions associated with necrotic peripancreatic lymph nodes and constitutional symptoms. Ultrasonography/computed tomography/endosonography-guided biopsy is the recommended diagnostic technique. Most patients achieve complete cure with standard antituberculous therapy. The aims of this study are to review clinical presentation, diagnostic studies, and management of pancreatic tuberculosis and to present our experience of 5 cases of pancreatic tuberculosis.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Pancreas, Difficult diagnosis before laparotomy, Antituberculous therapy

Introduction

Tuberculosis of the pancreas is extremely rare and in most of the cases mimics pancreatic carcinoma. In abdominal tuberculosis, ileocaecal region is most commonly affected; solid organs like kidney, spleen, and liver get involved with tuberculosis much more commonly than the pancreas. In most of the series and studies of abdominal tuberculosis, pancreatic tuberculosis has never been described in detail [1]. Pancreatic tuberculosis is very rare even in regions with high prevalence of tuberculosis, with an incidence reported to be less than 4.7 % (14/297 cases) in an autopsy series on tuberculosis patients in 1944 [2] and 2 % (11/526 cases) in another autopsy series in 1966 [3]. There are a number of case reports on pancreatic tuberculosis with various different presentations, but only a few case series have been published, and most of our knowledge about this disease comes from individual case reports. The authors encountered 5 cases of pancreatic tuberculosis in the last 10 years. Out of these 5 cases, pancreatic tuberculosis was a part of generalized disease, i.e., miliary tuberculosis in 3 patients, 1 patient had tuberculous pancreatic abscess, and 1 patient was found to have isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. The aims of this study were to review clinical presentation, diagnostic studies, and management of pancreatic tuberculosis and to present our experience of 5 cases of pancreatic tuberculosis.

Methods

Electronic searches were undertaken in MEDLINE and PUBMED using the MeSH terms “pancreas” in combination with “tuberculosis,” “tuberculous,” “tubercular,” “tuberculosis in immunocompromised patients.” A total of 330 cases have been identified in various case reports and series. All resulting titles, abstract, and full text, when available, were read and kept for reference and the findings summarized. Both immunocompetent as well as immunocompromised cases were reviewed.

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis is one of the most important infectious diseases in the world. It is a disease of great public health importance in India. With 20 % cases, India accounts for the highest TB burden in the world. Not only does tuberculosis afflict 3.1 million people in India, it is also estimated that the lifetime risk for acquiring tuberculosis is 10 % [4] and this figure is understandably higher for medical professionals. With the rise of HIV/AIDS, there has been a resurgence of tuberculosis as an opportunistic infection in developed countries. While Mycobacterium tuberculosis most commonly afflicts the lungs, it also affects lymphoid tissue in the form of lymphadenitis, and lymphoid involvement is the most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, and abdominal tuberculosis is the sixth most common type [1], but pancreatic involvement is extremely rare. In majority of the published studies, patients in the age group of 21–40 are most commonly affected with no sex predilection [1, 5].

Though there has been increase in tuberculosis cases in western world due to human immunodeficiency virus in recent decades, still there is no increase in cases of pancreatic tuberculosis. There are a number of reports and a few series on pancreatic tuberculosis cases in immunocompromised as well as immunocompetent patients. In a study of 32 cases by Nagar et al. [5], 16 patients were seropositive for HIV-1 while Xia et al. [6] reported a study of 16 immunocompetent pancreatic tuberculosis cases. Besides this, there are a number of case reports of pancreatic tuberculosis in immunocompromised patients [7–10] and in immunocompetent patients [8, 11, 12]. Meesiri et al. [10] reviewed 43 cases HIV positive cases of pancreatic tuberculosis.

Clinical Presentation

Patients of pancreatic tuberculosis may remain asymptomatic initially and manifest as an abscess or a mass involving local lymph nodes and resembling carcinoma. Patients usually present with non-specific features. Symptomatic patients may show evidence of tuberculous toxaemia. The presenting symptoms of pancreatic TB include abdominal pain, abdominal mass, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, night sweats, backache, jaundice, and fever. If the head is involved, obstructive jaundice and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms. One of our patients with isolated pancreatic tuberculosis presented with abdominal pain and jaundice. In a report by Ladas et al., a patient presented with iron deficiency anemia and severe weight loss. Nagar et al. [5] in his study on 32 patients reported that most common symptom was abdominal pain localized to epigastric region. Xia et al. [6] also reported that most common symptom is abdominal pain and nodule present in 75 % of cases followed by malaise and weakness. Fever was the most common symptom in a case series of 13 patients [13]. There are many case reports with different presentations of pancreatic tuberculosis like dyspeptic symptoms [14], gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to secondary to splenic vein thrombosis [15], acute/chronic pancreatitis [16], or secondary diabetes [17]. Pancreatic head masses may result in obstructive cholangiopathy and portal vein thrombosis. Clinically, an epigastric lump is the most common, lump may be tender, or epigastric tenderness without the lump is second most common presentation (Table 1). Splenomegaly and hyperslenism have also been reported [13].

Table 1.

Different presentations in various case reports

| Author | Year | Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Chandrasekhara et al. [18] | 1985 | Carcinoma pancreas |

| Wu et al. [19] | 1994 | |

| Rezeig et al. [20] | 1998 | |

| Kourakalis et al. [21] | 2001 | |

| Weiss et al. [22] | 2005 | |

| Yavuz et al. [23] | 2012 | |

| Raghvan et al. [12] | 2012 | |

| Crowson et al. [24] | 1983 | Obstructive jaundice |

| Chen et al. [25] | 1999 | |

| Ozkan et al. [26] | 2013 | |

| Ruttenberg et al. [27] | 1991 | Portal hypertension |

| Li et al. [28] | 1999 | |

| Schneider et al. [29] | 2002 | |

| Rushing et al. [16] | 1978 | Pancreatitis |

| Fan et al. [15] | 1986 | Massive gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Zalev et al. [30] | 1997 | Metastatic ovarian carcinoma |

| Ladas et al. [9] | 1998 | Iron deficiency anaemia |

| Patankar et al. [17] | 1999 | Diabetes mellitus |

| Evans et al. [31] | 2000 | Metastatic pancreatic carcinoma |

| Veerabadran et al. [32] | 2007 | Pancreatic abscesses and colonic perforation |

| Nakai et al. [33] | 2007 | Pancreatbiliary fistula |

| Chang et al. [7] | 2008 | Progressive dysphagia |

| Pandita et al. [14] | 2009 | Dyspepsia |

| Rana et al. [34] | 2010 | Focal pancreatitis and segmental portal hypertension |

| Hellara et al. [35] | 2012 | Pseudotumoral presentation |

Pancreatic tuberculosis may manifest as an abscess (Table 2), mass, or a cystic lesion in the pancreas. Twenty-one cases of pancreatic tuberculous abscess have been reported so far. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess are more common in HIV positive patients probably because of lower immunological response and higher bacterial load. Kumar et al. reported 2 cases of pancreatic tuberculosis, one patient had multiple small abscesses in the pancreas while the other one had a pancreatic head mass with peripancreatic lymph nodes. Our patient with tuberculous pancreatic abscess presented with fever, malaise, weakness, and anorexia. Chang et al. [7] reported a case in which the patient had a cystic mass in the body of the pancreas with portal and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Other presentations like multicystic pancreatic masses, bulky pancreas, calcifications, and peripancreatic nodules have also been described.

Table 2.

Pancreatic tuberculous abscess

| Author | Year | HIV status |

|---|---|---|

| Stambler et al. [36] | 1982 | _ |

| De Miguel et al. [37] | 1985 | _ |

| Aggarwal et al. [38] | 1989 | _ |

| Berson et al. [39] | 1989 | Positive |

| Tetzeli et al. [40] | 1989 | Positive |

| Meinke et al. [41] | 1989 | Positive |

| Cho et al. [42] | 1990 | Positive |

| Cappell et al. [43] | 1990 | Positive |

| Watanapa et al. [44] | 1991 | _ |

| Lupatkin et al. [45] | 1992 | Positive |

| Levine et al. [46] | 1992 | Negative |

| Park et al. [47] | 1993 | _ |

| Jaber et al. [48] | 1995 | Positive |

| Desmond et al. [49] | 1995 | Positive |

| Molina et al. [50] | 1997 | Positive |

| Jenney et al. [51] | 1998 | Negative |

| Ayala et al. [52] | 1998 | Positive |

| Jena et al. [53] | 1999 | Positive |

| Chaudhary et al. [54] | 2002 | Negative |

| Kumar et al. [8] | 2003 | Positive |

| Veerabadran et al. [32] | 2007 | Negative |

| Mangla et al. [55] | 2013 | _ |

| Meesiri et al. [12] | 2014 | Positive |

Pathogenesis

Pancreas is relatively resistant to tuberculosis because of destruction of the pathogen by pancreatic enzymes. The role of antibacterial pancreatic factors has also been proposed as a factor responsible for rare occurrence of pancreatic tuberculosis. Also, an antimycobacterial effect from pancreatic extracts and purified lipases and deoxyribonucleases has been reported [56].

The most common route of spread of tuberculosis to the solid organs of abdomen is the haematogenous route and less commonly the lymphatic route. Pancreatic TB is most often the result of haematogenous or lymphatic dissemination or direct spread from adjacent organs. Three forms of pancreatic tuberculosis have been described: (a) as a part of miliary tuberculosis, (b) spread to the pancreas from retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and (c) localized pancreatic tuberculosis which is mostly due to M. tuberculosis secondary to primary tubercular infection of the intestinal tract [57].

Pancreatic involvement in tuberculosis is most commonly a part of military tuberculosis (type (a) as mentioned above), but Nagar et al. [5] in his study reported that out of 32 patients 18 patients were diagnosed to have pancreatic and peripancreatic involvement as first manifestation of tuberculosis.

Role of Imaging Studies

Less than half the patients have past history of tuberculosis or evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis on chest X-ray. Pancreatic tuberculosis may present with a wide range of imaging findings. It is difficult to diagnose tuberculosis of pancreas on imaging studies as they may present with masses, cystic lesions or abscesses, and mass lesions in most of the cases mimic pancreatic carcinoma. As it is a rare entity, it cannot be recommended but suggested that pancreatic tuberculosis should be considered in cases with a large space occupying lesions associated with necrotic peripancreatic lymph nodes and constitutional symptoms. Woodfield et al. [58] in his study concluded that radiological appearances may be similar to a mucinous cystic neoplasm or could show a pancreatic mass with involvement of peripancreatic lymph nodes or a mass centered in a peripancreatic lymph node.

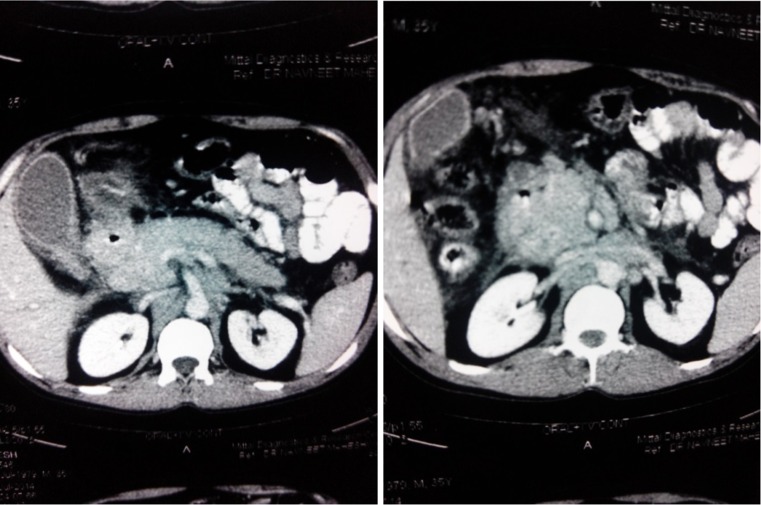

The diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis is not suspected before laparotomy in majority of cases [13, 57]. Since this disease is curable with chemotherapy, it is important to diagnose it on imaging studies to avoid any major surgery and its associated morbidity. Ultrasound shows bulky inhomogenous pancreas or a cystic lesion or one or more solid hypoechoic masses in the pancreatic parenchyma that may sometimes show central liquefaction and does not show any specific feature suggestive of tuberculosis of pancreas. CT scan was done in almost all of the reported studies but failed to diagnose pancreatic tuberculosis in majority of cases as there are pathognomonic features suggestive of tuberculosis. CT features of pancreatic tuberculosis are non-specific (Fig. 1) and include hypodense, hypovascular well-defined mass with irregular margins and peripheral enhancement; areas of central enhancement may result in a multiloculated appearance with adjacent necrotic or non-necrotic lymphadenopathy. These features may resemble these of inflammatory or neoplastic cystic lesions of the pancreas. In a study by Nagar et al. [5], CT showed hypodense collections within the pancreas associated with peripancreatic lymphadenopathy in 29 patients while 3 patients had a complex pancreatic mass lesion. Xia et al. [6] in a study on 16 patients reported that CT showed pancreatic mass with heterogenous hypodensity focus in all patients with calcification in 9 patients and peripancreatic nodules in 6 patients. In cases of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, the pancreatic duct is dilated in centrally located tumors of the pancreatic head while the common bile duct and pancreatic head have been reported to be normal in patients with pancreatic tuberculosis, even if the mass is positioned centrally in the head of the pancreas [34, 59]. It has also been reported that in patients with pancreatic tuberculosis, obstruction and dilatation of common bile duct and intrahepatic bile ducts are rare [24]. Also, in cases of pancreatic tuberculosis, there is absence of vascular invasion and pancreatic duct dilatation.

Fig. 1.

CECT showing pancreatic mass in head with hypodense collection

Chatterji et al. [60] in his study concluded that endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is the diagnostic modality of choice for pancreatic tuberculosis. Linear EUS allows high-resolution imaging that can readily differentiate pancreatic and peripancreatic masses. Woodfield et al. [58] also recommended that EUS is a preffered technique for diagnosing pancreatic tuberculosis. De Backer et al. [59] described MRI features of pancreatic tuberculosis in 3 patients and concluded that in cases of focal involvement, MRI showed sharply delineated mass located in the pancreatic head, showing heterogenous enhancement, and diffuse involvement is characterized by pancreatic enlargement with narrowing of the main pancreatic duct and heterogenous enhancement.

Role of FNAC/Trucut Biopsy/Laparotomy in Diagnosis

Ultrasound cannot diagnose tuberculosis of pancreas but in cases suspected of tuberculosis US helps in taking sample for fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). FNAC is the easiest and non-invasive method of diagnosing pancreatic tuberculosis. In suspected cases, FNAC can be taken from pancreatic lesion or peripancreatic lymph nodes. As most of the cases of pancreatic tuberculosis are confused with malignancy, FNAC not only confirms tuberculous etiology but also rules out malignancy. There are a number reports which recommends FNAC for diagnosing tuberculosis [60–62]. FNAC can be done under US/EUS/CT guidance. As reported by Chatterji et al. [60], EUS-guided FNAC is better for diagnosing these cases as it facilitates high-resolution imaging. Mallery et al. [61] retrospectively compared sensitivity and specificity of EUS, US, and CT scan for taking sample in pancreatic pathologies and concluded that EUS-guided tissue sampling is as accurate as CT/US-guided sampling and surgical biopsies. American joint commission on cancer also recommends EUS-FNAC as the diagnostic modality of choice for identifying the etiology of pancreatic masses [63]. Acid-fast bacilli are commonly not seen with FNAC. FNAC reveals the presence of granulomatous inflammation with aggregates of plasma cells, epitheloid cells, and lymphocytes.

Trucut biopsy is usually not possible in cases of pancreatic lesions and peripancreatic lymph nodes as there is a risk of injury to the intestine as well as vessels.

Though there have been case reports of biliary cytology confirming the diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis, in most of the cases, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography has been found to be normal and usually not helpful [64].

The best way of diagnosing tuberculosis is direct histopathological proof by taking excisional biopsy. Direct histopathological examination by laparotomy should only be done in cases imaging studies and FNAC fail to confirm diagnosis. There have been a number of studies where diagnosis of tuberculosis was not even suspected [13, 57] and final histopathological report came as a surprise. Biopsy is usually taken from pancreatic lesion and/or peripancreatic lymph node. There is case report in which diagnosis was made after excision of pancreatic tail and spleen because preoperatively, a diagnosis of advanced pancreatic tail malignancy was made [65]. In a study by Xia et al. [6], laparotomy was performed in 12 out of 16 patients, and Yan et al. [13] reported that out of 13 patients, 12 required laparotomy. The success rate of identifying acid fast bacilli from the biopsy specimen has been reported to be between 20 and 40 % [66]. Cultures were found to be positive in 77 % cases [9]. In our patients with isolated pancreatic tuberculosis and tuberculous pancreatic abscess, CT scan and guided FNAC failed to diagnose them, and PCR was not done as we did not suspect tuberculosis as etiological factor in both the cases and final diagnosis was confirmed by direct histopathological examination by laparotomy, but no major surgical procedure was done in these patients.

Role of Polymerase Chain Reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are diagnostic in most patients presenting with rare manifestation of tuberculosis including pancreatic and hepatobiliary tuberculosis because conventional methods many times fail to diagnose extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Makeshkumar et al. [67] in a study on 178 patients concluded that PCR was able to pick up more extra pulmonary tuberculosis patients as compared to conventional methods. PCR assays have been found to be superior to smear and culture in detecting mycobacterium tuberculosis. It has a sensitivity of 64 % [68]. PCR assay is helpful in diagnosis, and laparotomy can be avoided. Ayesha et al. [69] and Chatterji et al. [60] utilized PCR assay in conjunction with EUS-guided FNAC to diagnose pancreatic tuberculosis. PCR assay in conjunction with other non-invasive modalities is helpful in diagnosing pancreatic tuberculosis. Meesiri et al. [10], in a review on 43 cases, reported that PCR was done in 4 cases and all 4 were positive for M. tuberculosis DNA. Drug susceptibility cannot be reliably determined with PCR assay. In a review by Meesiri et al., drug susceptibility was studied in 9 samples, and 1 was found to be resistant to streptomycin, and others were sensitive to first-line antituberculous drugs.

Other Investigations

HIV testing should always be done in all the patients suspected to have pancreatic tuberculosis. No other investigation is contributory for diagnosis or prognosis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for pancreatic tuberculosis includes pancreatic cancer, metastases, cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, focal chronic pancreatitis, fungal infections, castlemann’s disease, and sarcoidosis.

Treatment

Pancreatic tuberculosis is usually difficult to diagnose, but once diagnosed, it is potentially curable with antituberculous drugs. The treatment of pancreatic tuberculosis is same as any other type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis [70]. Standard antituberculous therapy involving the use of at least four drugs remains the cornerstone of treatment [5, 6, 13, 57, 58]. As reported in almost all the studies, patients with pancreatic tuberculosis respond very well with conventional antituberculous treatment. Reported literature recommends the use of antituberculous drugs for 6–12 months [5, 6, 58]. Treatment consists of fourfold combination: isoniazid (5 mg/kg BW/ ay), rifampicin (10 mg/kg BW/day), pyrazinamide (30 mg/kg BW/day), ethambutol (20 mg/kg BW/day) generally for 2–4 months, subsequently isoniazid and rifampicin for 6–12 months. Multidrug-resistant organisms and hepatotoxicity of the agents require alternative regimens [70]. Drug-induced liver injury secondary to antituberculous drugs, especially isoniazid, is idiosyncratic and potentially lethal. Careful monitoring for drug-induced hepatitis may obviate fatality. For follow-up and guiding clinicians regarding complete resolution and duration of therapy, CT imaging is helpful [69]. In a retrospective study by Kim et al. [71], out of 42 patients with pancreatic tuberculosis, only 1 patient had progressive disease on CT imaging.

In cases of biliary obstruction, there is a need of endoscopic or surgical intervention to relieve the obstruction as the narrowing might persist despite antituberculous therapy, and this intervention should be done at an early stage during the course of treatment [57]. In 43 HIV-positive patients reviewed by Meesiri et al. [10], duration of antituberculous therapy ranged from 3 weeks to 2 years. The authors report that out of 5 patients, 1 patient with miliary tuberculosis died due to septic shock and multiorgan failure while the other 4 patients recovered well with standard antituberculous treatment.

As surgery is often required for diagnosing pancreatic tuberculosis, it is recommended not to do any major surgical procedure other than taking tissue for histopathology but abscess needs to be drained. Whipple’s pancreaticoduodenectomy was done in many reported studies for pancreatic tuberculosis because most common presentation is pancreatic mass which is difficult to differentiate from pancreatic cancer [57]. Whipple’s pancreaticoduodenectomy was done in 3 patients [57] and distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy in 1 patient [57, 65].

Conclusion and Recommendations

Abdominal tuberculosis is the sixth most common type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, but pancreatic tuberculosis is very rare. Most cases of pancreatic tuberculosis are secondary to tuberculous infection elsewhere in the body and are associated with military tuberculosis. It is difficult to diagnose this entity only on imaging studies, EUS-guided FNAC helps in diagnosing this condition. Once diagnosed, it is possible to cure pancreatic tuberculosis with standard antituberculous therapy. The author recommends

The most important factor in making a correct diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis is first to consider the possibility, as the symptoms and imaging findings may be subtle or confusing. Diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis should always be considered in young patients who present with non-specific symptoms and a pancreatic mass with peripancreatic lymphadenopathy on imaging studies. Pancreatic mass in an immunocompromised patient or in a patient who is from a region with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, like in developing countries, pancreatic tuberculosis should be considered.

It is important to review imaging studies properly before planning any form of surgical treatment.

Direct histopathological examination is the best way of diagnosing tuberculosis. US/CT/EUS-guided biopsy is the recommended diagnostic technique. EUS-guided biopsy is better than US or CT-guided biopsy. Under image guidance, if FNA fails once, it is advisable to go for second attempt under-image guidance because this might avoid laparotomy.

In cases where definite diagnosis is not possible or fails with image-guided biopsy but clinically there is a strong suspicion for pancreatic tuberculosis, PCR needs to be done for diagnosis.

Laparotomy should be avoided for diagnostic purpose for its associated morbidity. Most of the patients who required major surgical intervention, the preoperative diagnosis was malignancy and not tuberculosis. To avoid major surgery in pancreatic tuberculosis, the author recommends attempted identification of these patients early in the evaluation.

Most patients achieve complete cure with standard antituberculous therapy.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

None

Funding

None

References

- 1.Sharma MP, Bhatia A. Abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:6371–6375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach O. Acute generalized military tuberculosis. Am J Pathol. 1944;20:121–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paraf A, Menager C, Texier J. La tuberculose du pancreas et la tuberculose des ganglions de l’etage superieur de l’abdomen. Rev Med Chir Mal Foie. 1966;41:101–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park K (2011) Epidemiology of communicable diseases. Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine, 21st ed. Bhanot Jabalpur 64–68

- 5.Nagar AM, Raut AA, Morani AC, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis: a clinical and imaging review of 32 cases. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:136–141. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31816c82bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia F, Poon RT, Wang SG, et al. Tuberculosis of pancreas and peripancreatic lymph nodes in immunocompetent patients: experience from China. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1361–1364. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i6.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang J, Tadi K, Halpern M, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis in a human immunodeficiency virus positive patient: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:939–940. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar R, Kapoor D, Singh J, et al. Isolated tuberculosis of the pancreas: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Trop Gastroenterol. 2003;24:76–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladas SD, Vaidakis E, Lariou C, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis in non-immunocompromised patients: reports of two cases, and a literature review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:973–976. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meesiri S. Pancreatic tuberculosis with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a case report and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:720–726. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i7.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandya G, Dixit R, Shelat V, et al. Obstructive jaundice: a manifestation of pancreatic tuberculosis. J Indian Med Assoc. 2007;105:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghavan P, Rajan D. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking malignancy in an immunocompetent host. Case Rep Med. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/501246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan CQ, Guo JC, Zhao YP. Diagnosis and management of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis; experience of 13 cases. Chin Med Sci J. 2007;22:152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandita KK, Sarla, Dogra S. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:259–260. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.53212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan ST, Yan KW, Lau WY, et al. Tuberculosis of the pancreas: a rare cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding. Br J Surg. 1986;73:373. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rushing JL, Hanna CJ, Selecky PA. Pancreatitis as the presenting manifestation of military tuberculosis. West J Med. 1978;129:432–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patankar T, Prasad S, Laxminarayan R. Diabetes mellitus: an uncommon manifestation of tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:938–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandrasekhara KL, Iyer SK, Stanek AE, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:386–388. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(85)72255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CS, Wang SH, Kuo TT. Pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic head carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Infection. 1994;22:287–289. doi: 10.1007/BF01739920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezeig MA, Fashir BM, Al-Suhaibani H, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic carcinoma: four case reports and review of literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:329–331. doi: 10.1023/A:1018854305652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kouraklis G, Glinavou A, Karayiannakis A, et al. Primary tuberculosis of the pancreas mimicking a pancreatic tumor. Int J Pancreatol. 2001;29:151–153. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:29:3:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss ES, Klein WM, Yeo CJ. Peripancreatic tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic neoplasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yavuz A, Bulus H, Aydin A, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking inoperable pancreatic cancer. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2012;23:95–97. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2012.0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowson MC, Perry M, Burden E. Tuberculosis of the pancreas: a rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg. 1983;71:239. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CH, Yang CC, Yeh YH, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis with obstructive jaundice—a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2534–2536. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozkan F, Bulbuloglu E, Inci MF, et al. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking malignancy and causing obstructive jaundice. J Gastointest Cancer. 2013;44:118–120. doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9374-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruttenberg D, Graham S, Burns D, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis: a cause of portal vein thrombosis and portal hypertension. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:112–115. doi: 10.1007/BF01300098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li XH, Wang YL, Yao YM. A case of local portal hypertension caused by pancreatic TB. Zhonghua Gandan Waike Zazhi. 1999;4:28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider A, Von-Birgelen U, Duhrsen G, et al. Two cases of pancreatic tuberculosis in non-immunocompromised patients: a diagnostic challenge and a rare cause of portal hypertension. Pancreatology. 2002;2:69–73. doi: 10.1159/000049451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zalev AH, Sacks JS, Warren RE. Pancreaticoduodenal tuberculosis simulating metastatic ovarian carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997;11:41–43. doi: 10.1155/1997/107435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans JD, Hamanaka Y, Olliff SP, et al. Tuberculosis of the pancreas presenting as metastatic pancreatic carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2000;17:183–187. doi: 10.1159/000018828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veerabadran P, Sasnur P, Subramanain S, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis- abdominal tuberculosis presenting as pancreatic abscess and colonic perforation. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:478–479. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakai Y, Tsujino T, Kawabe T, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis with a pancreatobiliary fistula. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1225–1228. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9471-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Rao C, et al. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking focal pancreatitis and causing segmental portal hypertension. JOP. 2010;11:393–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hellara O, Noomene F, Toumi O. A pseudotumoral presentation of pancreatic tuberculosis. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e282–e283. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stambler JB, Klibaner MI, Bliss CM, et al. Tuberculous abscess of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:922–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Miguel F, Beltran J, Sabas JA. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess. Br J Surg. 1985;72:438. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal P, Wali JP, Jain R, et al. Tubercular abscess of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:985–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berson BD, Mendelson DS, Janus CL. Tuberculous abscess of the pancreas in AIDS: CT findings. Mt Sinai J Med. 1989;56:297–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tetzeli JP, Pisegna JR, Barkin JS. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess as a manifestation of AIDS. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:581–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meinke AK. Pancreatic tuberculous abscess. Conn Med. 1989;53:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho KC, Lucak SL, Delany HM, et al. CT appearance in tuberculous pancreatic abscess. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14:152–154. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199001000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cappell MS, Laveed M. Pancreatic abscess due to Mycobacterial infection associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:423–429. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanapa P, Vathanopas V. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess: a rare condition mimicking carcinoma. HPB Surg. 1992;5:209–213. doi: 10.1155/1992/79652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lupatkin H, Brau N, Flomenberg P, et al. Tuberculous abscesses in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:1040–1044. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.5.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine R, Tenner S, Steinberg W, et al. Tuberculous abscess of the pancreas. Case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1141–1144. doi: 10.1007/BF01300301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park AJ. Pancreatic tubercular abscess. Pancreas. 1993;8:137–138. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199301000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jaber B, Gleckman R. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess as an initial AIDS-defining disorder in a patient with the human immunodeficiency virus: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:890–894. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desmond NM, Kingdon E, Beale TJ, et al. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess: an unusual manifestation of HIV infection. J R Soc Med. 1995;88:109–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molina M, Ortega G, Redondo C, et al. Tuberculous abscess of the pancreas as initial manifestation of AIDS. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;20:165–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenney AW, Pickles RW, Hellard ME, et al. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess in an HIV antibody-negative patient: case report and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:99–104. doi: 10.1080/003655498750003438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ayala HI, Martinez GM, Halabe CJ. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess as initial manifestation of AIDS. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 1998;63:220–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jena GP, Manoharan GR, Mbete DL, et al. Tuberculous pancreatic abscess in HIV-positive patient. A report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. S Afr J Surg. 1999;37:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chaudhary A, Negi SS, Sachdev AK, et al. Pancreatic tuberculosis: still a histopathological diagnosis. Dig Surg. 2002;19:389–392. doi: 10.1159/000065832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mangla V, George J, Das P, et al. Tubercular pancreatic abscess: diagnostic dilemma and management. Trop Gastroenterol. 2013;34:178–180. doi: 10.7869/tg.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knowles KF, Saltman D, Robson HG, et al. Tuberculous pancreatitis. Tubercle. 1990;71:65–68. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(90)90064-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saluja SS, Ray S, Pal S, et al. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic tuberculosis: a two decade experience. BMC Surg. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodfield JC, Windsor JA, Godfrey CC, et al. Diagnosis and management of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis: recent experience and literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:368–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Backer AI, Mortele KJ, Bomans P, et al. Tuberculosis of the pancreas: MRI features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:50–54. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chatterji S, Schmid ML, Anderson K, et al. Tuberculosis and the pancreas: a diagnostic challenge solved by endoscopic ultrasound. A case series. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2012;21:105–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mallery JS, Centeno BA, Hahn P, et al. Pancreatic tissue samplingguided bu EUS, CT/US, and surgery: a comparison of sensitivity and specificity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:218–224. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(02)70181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song TJ, Lee SS, Park do H, et al. Yield of EUS-guided FNA on the diagnosis of pancreatic/peripancreatic tuberculosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaushik N, Schoedel K, McGrath K. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: a case report. JOP. 2006;7:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D’Cruz S, Sachdev A, Kaur L, et al. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. A case report and review of literature. JOP. 2003;4:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rong YF, Lou WH, Jin DY. Pancreatic tuberculosis with splenic tuberculosis mimicking advanced pancreatic cancer with splenic metastases: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:84. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franco-Parades C, Leonard M, Jurado R, et al. Tuberculosis of the pancreas: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323:54–58. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Makeshkumar V, Madhavan R, Narayanan S. Polymerase chain reaction targeting insertion sequence for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:161–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gan HT, Chen YQ, Ouyang Q, et al. Differentiation between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease in endoscopic biopsy specimens by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1446–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Salahuddin A, Saif MW. Pancreatic tuberculosis or autoimmune pancreatitis. Case Rep Med. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/410142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chaudhary P. Hepatobiliary tuberculosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:207–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim JB, Lee SS, Kim SH, et al. Peripancreatic tuberculous lymphadenopathy can masquerade as pancreatic malignancy: a single centre experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:409–416. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]