Abstract

Objective(s):

To study the effect of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) on nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and cytokine expression and pulmonary function in dogs.

Materials and Methods:

Twelve male mongrel dogs were divided into a methylprednisolone group (group M) and a control group (group C). All animals underwent aortic and right atrial catheterization under general anesthesia. Changes in pulmonary function and hemodynamics were monitored and the injured site was histologically evaluated.

Results:

The activity of NF-κB and myeloperoxidase (MPO), levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, and the wet/dry (W/D) weight ratio were significantly higher after CPB than before CPB in both groups (P<0.01), with the lower values in group M than in group C, at different time points (P<0.01). Histological evaluation revealed neutrophilic infiltration and thickening of the alveolar interstitium in both groups; however, the degree of pathological changes was significantly lower in group M than in group C. The alveolar–arterial O2 tension difference (PA-aDO2) was significantly higher after CPB than before CBP (P<0.01), and lower in group M than in group C (P<0.01). The pulmonary compliance after removal of the aortic clamp obviously decreased in group C (P<0.05), with no significant change in group M.

Conclusion:

CPB can significantly enhance the activation of NF-κB in lung tissues and increase the expression of inflammatory cytokines, thus inducing lung injury. Methylprednisolone can inhibit the NF-κB activation, thus inhibiting the release of cytokines and protecting the lung function.

Keywords: Acute lung injury, Cardiopulmonary bypass Cytokines, Methyl-prednisolone, NF-κB

Introduction

Lung dysfunction following cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is a severe and life-threatening complication of heart surgery. Systemic inflamma-tory responses, nonphysiological CPB, and oxygenators play significant roles in inducing lung injury (1, 2). Lung ischemia–reperfusion further aggravates pulmonary injury through upregulation of the expression of several proinflammatory genes, increase of the neutrophil and macrophage adhesion to the vascular endothelium, and the release of many free radicals and enzymes by activated neutrophils (3). In recent years, although several measures have been adopted to prevent lung injury, such as the use of anti-inflammatory drugs (4, 5), continued ventilation and pulsatile pulmonary perfusion during CPB (6-8), leukocyte-depleting filters (9), and heparin-bonded circuits (10, 11), lung dysfunction.

following CPB is considered an important cause of postoperative mortality and the most common complication of cardiac surgery (1, 2, 5-7, 9, 12). Interestingly, complements, cytokines, and adhesion molecules constitute a complicated network during CPB, and the triggering of inflammatory responses by this network can generate a cascade of events (1, 3, 11). Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) (13-15), a nuclear transcription factor, has mostly been studied in recent years. It controls the expression of several genes, including cytokines and adhesion molecules, and is involved in immune response and cell growth, survival, differentiation, and apoptosis. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of CPB. on NF-κB activity, cytokines expression, and pulmonary function in dogs.

Materials and Methods

Animals and grouping

In total, 12 healthy male mongrel dogs (weight, 24–28 kg) provided by Fudan University affiliated with Zhongshan hospital were randomly divided into two groups: a methylprednisolone group (group M) and a control group (group C). In group M, the dogs were treated with 5 mg/kg/10 ml of methylprednisolone (Pfizer Manufacturing Belgium NV, Rijksweg 12, 2870 Puurs, Belgium) after the induction of anesthesia, while in group C, the dogs were treated with 10 ml of normal saline. This study was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health.

Anesthesia

The dogs were placed in the supine position after IV anesthesia with 30 mg/kg napental, and then the IV injection of 5 ug/kg fentanyl and 4 mg pipecuronium bromide; tracheal tubes with an internal diameter of 9.5 mm were inserted through the oral cavity for mechanical ventilation. The fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was 100%, tidal volume was 15 ml/kg, and respiratory frequency was 10-20 breaths per min. Meanwhile, the arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) was maintained at 35-45 mmHg through regulation of the respiratory frequency. Anesthesia was maintained by the continuous infusion of 2.5 mg/kg/min propofol via a pump and intermittent IV administration of fentanyl and pipecuronium bromide. All vital signs were checked, including the body temperature monitored using a temperature probe placed in the esophagus and electrocardiograms. Blood samples were obtained by femoral artery puncture. After heparinization, CPB was performed by inserting tubes into the ascending aorta and right auricle. Ventilation was ceased after CPB, and the aorta was clamped for 120 min. Rewarming was performed 110 min after aortic clamping. Then, CPB was gradually ceased after removal of the clamp, with cardiac resuscitation and the establishment of steady circulatory dynamics. All parameters were monitored for 90 min after removal of the aortic clamp, following which all the dogs were killed by F.vs.[lz1].

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB)

The priming solution used for CPB included 30 ml/kg of 20% mannite and 5% NaHCO3 each and 0.6 mg/ml of heparin, with Ringer’s lactate solution and gelofusine in a 1:8 proportion. The heart-lung machine used in this study was purchased from Jostra, Germany; the children’s membrane oxygenator and blood reservoir from Baxter; and tubes from the Shanghai Xiangsheng factory for medical instruments. After heparinization, CPB was initiated. The aorta was cross-clamped when the esophageal temperature dropped to 28-30 °C. Meanwhile, cold crystalloid cardioplegic solution (97.9 mmol/l NaCl, 13.4 mmol/l postassium glutamate and KCl, 2 mmol/l CaCl2, 16 mmol/l MgCl2, 1.9 mmol/l procaine, and 28.6 mmol/l NaHCO3) was perfused from the aortic root to achieve a flat line electrocardiogram. During CPB, the perfusion volume was maintained at 50-70 ml/kg, and the mean arterial pressure (MAP) at 50-70 mmHg. The gas volume was appropriately adjusted according to the PaCO2 value. The aortic clamp was removed at 35 °C after 110 min, and cardiac resuscitation was performed to restore normal ventilation. CPB was gradually ceased under a steady circulation, following which nucleoprotamine was administered to neutralize the effects of heparin. Steroid hormones were not administered to any animal during the experiment.

Test indices and measurements

Electrocardiograms, MAP, and the mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP) were continuou-.

sly measured. CVP, PCWP, CO[lz2], lung compliance, and arterial blood gases (ABGs) were also assessed before CPB (T0) and 30 (T2) and 90 (T3) min after aortic clamp removal. PVR, CI[lz3], and PA-aO2 were calculated, with PA-aO2 calculated using the following formula: [FiO2 × (atmospheric pressure − 47) − (PaCO2 × 1.25) − PaCO2]. Serum was separated from arterial blood at T0, T1 (before aortic clamp removal), T2, and T3. Cytokines levels were measured by radioimmunoassay kits, such as 125I-labeled kit. The hematocrit value was used to adjust the effects of blood dilution; with the correction value calculated using the following formula: hematocrit before anesthesia/factual hematocrit × testing value. Tissues were obtained from the upper left lung lobe at T0, T1, T2, and T3. Nucleoprotein from the lung tissue cells was extracted using the Derychere F method (16), and NF-κB activity was measured by the Western blot assay. The wet/dry (W/D) weight ratio was calculated after placing the lung tissue at 85 °C for 72 hr. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels were measured using colorimetry, and pathological changes in the lungs were assessed by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software, and all data are expressed as means±standard deviations (SDs). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for within-group comparisons; while Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test was used for between-group comparisons. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

The weight, height, hematocrit value, and dose of vasoactive drugs used during the cardiac resuscitation period and CPB-off time showed no significant differences between the two groups (P>0.05).

Hemodynamic changes

MAP and CI showed no significant difference at any time point between the two groups. PVR was significantly higher at T2 and T3 than at T0 in group C (P<0.05), while there was no significant difference in group M (P>0.05).

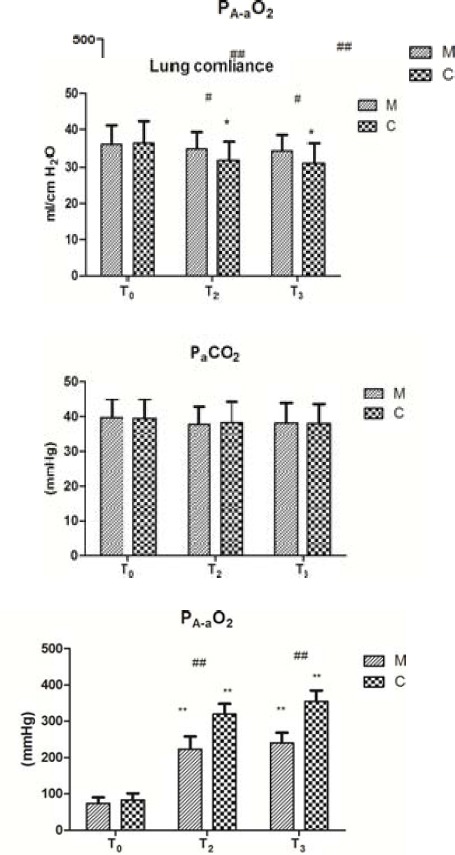

Pulmonary function changes

Compared to that at T0, PA-aDO2 at T2 and T3 was significantly increased (Figure 1, P<0.01). This increase was greater in group C than in group M. However, PaCO2 showed no significant difference between the two groups at any time point. The lung compliance was significantly decreased at T2 and T3 compared with that at T0 in group C (Figure, P>0.05); however, there was no significant difference in group M (Figure 1, P>0.05).

Figure 1.

Lung function changes (mean±SD).

Impacts of CPB on lung compliance, PA-aO2, and PaCO2 between the two groups. Data are expressed as the mean±SD (n=5 per group). #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, compared with the control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with the T0 (T0: before CPB, T2: 30 min after aortic clamp removal, and T3: 90 min after aortic clamp removal)

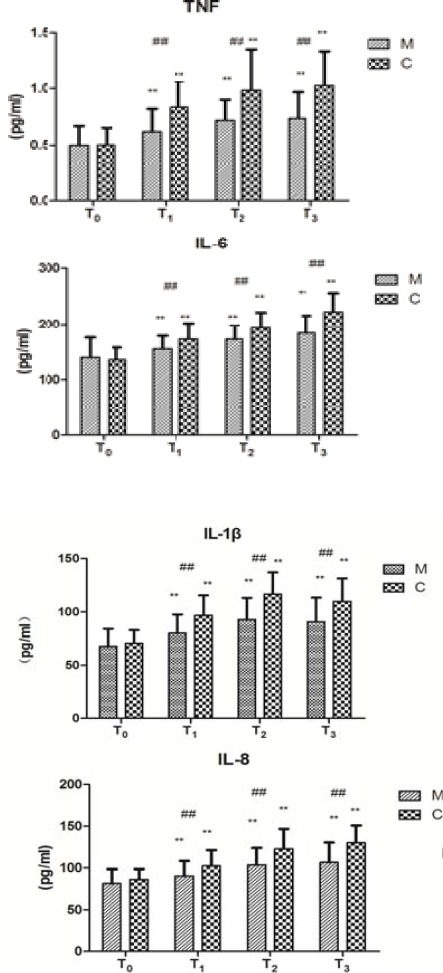

Cytokine levels

The cytokines levels were significantly higher at T1, T2, and T3 than at T0 (Figure 2, P<0.01), with those at T2 being significantly higher than those at T1 (Figure 2, P<0.05). The cytokines levels at T1, T2, and T3 were significantly lower in group M than in group C (Figure 2, P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Changes of cytokines levels (mean±SD).

Changes of NF-κB P65 activities of the two groups before and after CPB. NF-κB P65 activity was measured by the Western blot assay. NF-κB P65 activity indicates the intensity of bands on Western blot (IOD). Data are expressed as the mean±SD, (n=5 per group). ##P<0.01, compared with the control group; **P<0.01, compared with the T0 (T0: before CPB, T1: before aortic clamp removal, T2: 30 min after aortic clamp removal, and T3: 90 min after aortic clamp removal)

NF-κB P65 activity

The NF-κB P65 activity was significantly higher at T1, T2, and T3 than at T0 in both groups (Figure 3, P < 0.01). The activity at T2 was significantly higher than that at T1 (Figure 3, P < 0.05) in group C, whereas there was no significant difference in group M (Figure 3, P > 0.05). The NF-κB P65 activity at T1, T2, and T3 was lower in group M than in group C (Figure 3, P<0.01).

Figure 3.

Changes of NF-κB P65 activity (mean±SD).

Changes of NF-κB P65 activities of the two groups before and after CPB. NF-κB P65 activity was measured by the Western blot assay. NF-κB P65 activity indicates the intensity of bands on Western blot (IOD). Data are expressed as the mean±SD, (n=5 per group). ##P<0.01, compared with the control group; **P<0.01, compared with the T0 (T0: before CPB, T1: before aortic clamp removal, T2: 30 min after aortic clamp removal, and T3: 90 min after aortic clamp removal)

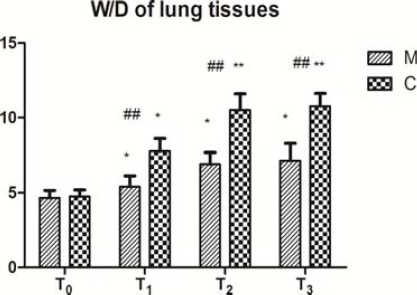

W/D weight ratio

The W/D weight ratio was significantly higher at T1, T2, and T3 than at T0 in both groups (Figure 4, P<0.05), with the values being significantly lower in group M than in group C (Figure 4, P<0.01).

Figure 4.

W/D of lung tissues (mean±SD).

Changes of wet/dry (W/D) weight ratios of the two groups before and after CPB. The W/D weight ratio was calculated after placing the lung tissue at 85 °C for 72 hr. Data are expressed as the mean±SD, (n=5 per group). ##P<0.01, compared with the control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with the T0 (T0: before CPB, T1: before aortic clamp removal, T2: 30 min after aortic clamp removal, and T3: 90 min after aortic clamp removal)

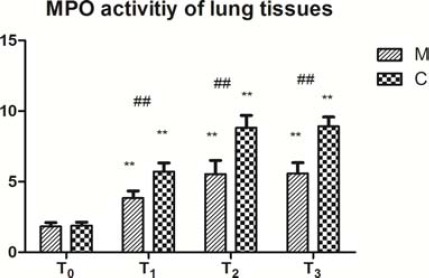

MPO activity

The MPO activity was significantly higher at T1, T2, and T3 than that at T0 in both groups (Figure 5, P<0.01). The activity at T2 was significantly higher than that at T1 in group C (Figure 5, P<0.05), while there was no significant difference in group M (Figure 5, P>0.05). Furthermore, the activity at T1, T2, and T3 was significantly lower in group M than in group C (Figure 5, P<0.01).

Figure 5.

MPO activity of lung tissues (mean±SD).

Changes of MPO activities in lung tissues of the two groups before and after CPB. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels were measured using colorimetry. Data are expressed as the mean±SD, (n=5 per group). ##P<0.01, compared with the control group; **P<0.01, compared with the T0 (T0: before CPB, T1: before aortic clamp removal, T2: 30 min after aortic clamp removal, and T3: 90 min after aortic clamp removal)

Pathological changes

At T0, the aortopulmonary septum was narrow without exudation in the alveolar spaces, while at T1, T2, and T3, the septum was widened with some exudation in the alveolar spaces. The degree of pathological changes at the three time points was lower in group M than in group C.

Discussion

Lung injury is the most common complication and the main cause of death after cardiac surgery under CPB (17, 30). Mild lung injury after CPB only leads to an increase in PA-aDO2; however, severe lung injury can develop into acute respiratory distress syndrome (1, 17, 18). Up to now, the detailed mechanisms of post-CPB lung injury are not very clear, the vast majority of scholars believed that CPB-induced systemic inflammatory responses were the main cause of lung injury. During CPB, blood contacts the nonphysiological CPB circuit system to activate the complement bypass system, following which the classical complement pathway is activated by the protamine-heparin complex to generate complement fragments (19-21) such as C3a, C5a, and C5b–9, which make up the complex to increase vascular permeability, activate neutrophilic granulocytes, and release histamine and several 3-cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (1, 2, 7). TNF-α increases the microvascular permeability to induce multiorgan dysfunction (22); IL-6 is considered a marker of severe tissue injury and a prognostic indicator in patients with infectious shock; and IL-8, a major chemotactic factor in neutrophilic granulocytes, regulates lung injuries mediated by neutrophilic granulocytes. Cytokines induce the expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules such as P-selectin and E-selectin, which promote adhesion and activation of neutrophilic granulocytes that cause lung injury through the release of many active substances such as collagenase, metalloproteinase, and MPO in the lung capillaries (23, 24). In recent years, with the purpose of reducing the inflammatory cytokines in blood, CPB techniques have been developed by heparin-coated CPB circuit, pulmonary perfusion, CPB ultrafiltration, leukocyte filtration, miniature CPB and intra-CPB pulmonary ventilation, etc. (9, 11, 31-34), but these techniques still could not significantly reduce the incidence of post-CPB lung injury. We believed that these techniques have only reduced the levels of inflammatory cytokines to some extent, while did not eliminate the triggers of lung injury. The inflammatory cytokines would form a complex network inside body, and the elevated levels of cytokines would cause a cascading waterfall effect and consequently rapid increase of cytokines, thus induce a series of pathophysiological changes. Many cytokines and adhesion molecule genes have binding sites on NF-κB and play an important regulatory role in the transcription and expression of NF-κB (13-15). Usually, NF-κB is sequestered in an inactive form in the cytoplasm because of its association with the inhibitory protein IκB. When stimulated, after the proteasomal degradation of IκB, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and binds to the target DNA elements in the promoters of different genes. Some studies[lz4] have also reported that an inactive NF-κB/I-κB complex exists in the cytoplasm. When the p32 and p36 serines of I-κB are phosphorylated under hypoxic conditions, I-κB is separated from the NF-κB/I-κB complex, and the activated NF-κB enters the nucleolus to combine with the special κB site and regulate gene transcription. During CPB, active complements, inflammatory responses, and hypoxia can quickly activate NF-κB and increase the cytokines levels. At the same time, increased TNF-α and IL-1β levels also stimulate NF-κB, resulting in positive feedback. Therefore, NF-κB probably plays a much important role in lung injury (13). We established canine CPB model to completely simulate post-CPB lung injury. The clinical results showed that at each time point after CPB (T1-T3), the activities of NF-κB in lung tissues were increased significantly than before CPB, meanwhile, the inflammatory cytokines at corresponding time point were also significantly increased than that before CPB. The MPO activity in lung was significantly increased., and the pathological results of lung tissues showed pulmonary interstitial edema and neutrophil infiltration; pulmonary compliance was also reduced and PA-aO2 was increased, thus inducing acute lung injury. The comparison of NF-κB activity and cytokine levels at T2 and T3 showed small changes than those at T1, but the pulmonary MPO activity, W/D ratio, and pathological changes were further aggravated, indicating that pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion increased lung injury (because lung functions could not be monitored at T1, so this study did not compare those data among T1, T2, and T3). The advantages of animal experiments lied in that healthy animals with completely normal heart and lung functions could be selected, so that the differences among individuals were small, and it could also avoid the impacts of medical diseases and surgeries of clinical patients on the results. [lz5]Through this experiment, we believed that in the pathogenesis of CPB-induced lung injury, NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines played important roles, so selecting effective NF-κB inhibitor to block the activation of NF-κB could effectively prevent and reduce inflammatory responses.

Methylprednisolone was a commonly used anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agent, while its anti-inflammatory mechanism was not very clear. Methylprednisolone might inhibit the activity of NF-κB and exert anti-inflammatory effects through the following three pathways: First, themethylpredni-solone-glucocorticoid receptor complex competes with the p65 subsite to inhibit NF-κB-dependent transcription in the nucleolus (25). Second, the complex induces I-κB synthesis to suppress NF-κB activation in the cytoplasm (26). Third, the complex competes against transcriptional cofactors with NF-κB (27, 28). Lodge AJ et al (29) and Tassani P et al (35) found through animal experiments and clinical observations, respectively, that the single application of high-dose corti-costeroids or combined with aprotinin could significantly reduce the release of inflammatory cytokines and improve lung functions. While Chaney MA et al (36) found corticosteroids could not improve lung functions, so that it could not be helpful to achieve the early removal of endotracheal tube. The comparison of the above two implementation methods revealed that the effects of glucocorticoids were poor when added at the beginning of surgery or in CPB, while the effects would be better when added before anesthesia or when the surgery is prolonged. Under exogenous stimulation, phosphorylated I-κB is not steady and degrades in 10-15 min. Because methylprednisolone inhibits NF-κB activation by inducing the synthesis of I-κB, the treatment duration seems to play an important role (29). In view of the possible inhibitory mechanisms of methylprednisolone on NF-κB activation, a small-dose of methylpredni-solone (5 mg/kg) was applied 60 min before the start of CPB. The results showed that the activity of NF-κB in the treatment group at each post-CPB time point was significantly lower than the control group, and also the levels of cytokines, the MPO activity in lung tissues, the neutrophil infiltration, the pulmonary edema, and the PA-aO2 level were significantly decreased, however lung functions were significantly improved; the similar results were obtained by repeated administration of high-dose (30 mg/kg) glucocorticoids (at 8 hr and 1.5 hr before surgery) (29), meanwhile, the side effects were reduced. In addition to the inflammatory responses, pneumal [lz6]ischemia-reperfusion, surgical trauma, and anesthesia s might affect the changes of lung functions and cause CPB-derived lung injury (30). Therefore, the prevention and treatment of lung injury after cardiac surgery under CPB should be further investigated.

Conclusion

CPB can activate NF-κB in the lung tissues and significantly increase the release of inflammatory cytokines to cause pulmonary inflammation and edema through neutrophil and monocyte infiltration and pulmonary injuries characterized by a decline in gas exchange. Methylprednisolone (5 mg/kg) can inhibit the activity of NF-κB, decrease the release of cytokines, inhibit infiltration and inflammation caused by pulmonary inflammatory cells, improve gas exchange, and decrease the degree of CPB-associated lung injuries.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the Department of Anesthesiology, The Affiliated Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, China. The results described in this paper were part of postgraduate thesis.

References

- 1.Apostolakis E, Filos KS, Koletsis E, Dougenis D. Lung dysfunction following cardiopulmonary bypass. J Card Surg. 2010;25:47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2009.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onorati F, Rubino AS, Nucera S, Foti D, Sica V, Santini F, et al. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery versus standard linear or pulsatile cardiopulmonary bypass:endothelial activation and inflammatory response. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng CS, Hui CW, Wan S, Wan IY, Ho AM, Lau KM, et al. Lung ischaemia-reperfusion induced gene expression. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1411–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen BM, Goonewardene LA, Joffe AR, Van Aerde JE, Field CJ, Olstad DL, et al. Pre-treatment with an intravenous lipid emulsion containing fish oil (eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid) decreases inflammatory markers after open-heart surgery in infants:a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearl JM, Schwartz SM, Nelson DP, Wagner CJ, Lyons JM, Bauer SM, et al. Preoperative glucocorticoids decrease pulmonary hypertension in piglets after cardiopulmonary bypass and circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng CS, Arifi AA, Wan S, Ho AM, Wan IY, Wong EM, et al. Ventilation during cardiopulmonary bypass:impact on cytokine response and cardiopulmonary function. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goebel U, Siepe M, Mecklenburg A, Doenst T, Beyersdorf F, Loop T, et al. Reduced pulmonary inflammatory response during cardiopulmonary bypass:effects of combined pulmonary perfusion and carbon monoxide inhalation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onorati F, Santarpino G, Tangredi G, Palmieri G, Rubino AS, Foti D, et al. Intra-aortic balloon pump induced pulsatile perfusion reduces endothelial activation and inflammatory response following cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:1012–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onorati F, Santini F, Mariscalco G, Bertolini P, Sala A, Faggian G, et al. Leukocyte filtration ameliorates the inflammatory response in patients with mild to moderate lung dysfunction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangoush O, Purkayastha S, Haj-Yahia S, Kinross J, Hayward M, Bartolozzi F, et al. Heparin-bonded circuits versus nonheparin-bonded circuits:an evaluation of their effect on clinical outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1058–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunaydin S, McCusker K, Sari T, Onur MA, Zorlutuna Y. Clinical performance and biocompatibility of hyaluronan-based heparin-bonded extracorporeal circuits in different risk cohorts. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:371–376. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.220756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ruzzeh S, Ambler G, Asimakopoulos G, Omar RZ, Hasan R, Fabri B, et al. Off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery reduces risk-stratified morbidity and mortality:a United Kingdom Multi-Center Comparative Analysis of Early Clinical Outcome. Circulation. 2003;108:II1–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087440.59920.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu SF, Malik AB. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L622–645. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava SK, Ramana KV. Focus on molecules:nuclear factor-kappaB. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:2–3. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin AS., Jr The NF-kappa B I kappa B proteins:new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deryckere F, Gannon F. A one-hour minipreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from animal tissues. Biotechniques. 1994;16:405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens RS, Shah AS, Whitman GJ. Lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1122–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman C. Pulmonary complications after cardiac surgery. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;8:185–211. doi: 10.1177/108925320400800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovrum E, Mollnes TE, Fosse E, Holen EA, Tangen G, Abdelnoor M, et al. Complement and granulocyte activation in two different types of heparinized extracorporeal circuits. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:1623–1632. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(95)70023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirklin JK, Chenoweth DE, Naftel DC, Blackstone EH, Kirklin JW, Bitran DD, et al. Effects of protamine administration after cardiopulmonary bypass on complement, blood elements, and the hemodynamic state. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;41:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shastri KA, Logue GL, Stern MP, Rehman S, Raza S. Complement activation by heparin-protamine complexes during cardiopulmonary bypass:effect of C4A null allele. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:482–488. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khabar KS, elBarbary MA, Khouqeer F, Devol E, al-Gain S, al-Halees Z. Circulating endotoxin and cytokines after cardiopulmonary bypass:differential correlation with duration of bypass and systemic inflammatory response/multiple organ dysfunction syndromes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;85:97–103. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark SC. Lung injury after cardiopulmonary bypass. Perfusion. 2006;21:225–228. doi: 10.1191/0267659106pf872oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Dai Q, Huang X. Neutrophils in acute lung injury. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2278–2283. doi: 10.2741/4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. Cross-talk between nuclear factor-kappa B and the steroid hormone receptors:mechanisms of mutual antagonism. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:45–56. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.1.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auphan N, DiDonato JA, Rosette C, Helmberg A, Karin M. Immunosuppression by glucocorticoids:inhibition of NF-kappa B activity through induction of I kappa B synthesis. Science. 1995;270:286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. CBP (CREB binding protein) integrates NF-kappaB (nuclear factor-kappaB) and glucocorticoid receptor physical interactions and antagonism. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1222–1234. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. The interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB or activator protein-1:molecular mechanisms for gene repression. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:488–422. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lodge AJ, Chai PJ, Daggett CW, Ungerleider RM, Jaggers J. Methylprednisolone reduces the inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass in neonatal piglets:timing of dose is important. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:515–522. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan SM. Postperfusion lung syndrome:physio-pathology and therapeutic options. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc. 2014;29:414–425. doi: 10.5935/1678-9741.20140071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Apostolakis EE, Koletsis EN, Baikoussis NG, Siminelakis SN, Papadopoulos GS. Strategies to prevent intraoperative lung injury during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiessling AH, Guo FW, Gökdemir Y, Thudt M, Reyher C, Scherer M, et al. The influence of selective pulmonary perfusion on the inflammatory response and clinical outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18:732–739. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivu062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torina AG, Silveira-Filho LM, Vilarinho KA, Eghtesady P, Oliveira PP, Sposito AC, et al. Use of modified ultrafiltration in adults undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with inflammatory modulation and less postoperative blood loss:a randomized and controlled study. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curtis N, Vohra HA, Ohri SK. Mini extracorporeal circuit cardiopulmonary bypass system:a review. Perfusion. 2010;25:115–124. doi: 10.1177/0267659110371705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tassani P, Richter JA, Barankay A, Braun SL, Haehnel C, et al. Does high-dose methylprednisolone in aprotinin-treated patients attenuate the systemic inflammatory response during coronary artery bypass grafting procedures? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(99)90081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaney MA, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Nikolov MP, Blakeman BP, Bakhos M. Methylprednisolone does not benefit patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting and early tracheal extubation. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:561–569. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.112343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]