Abstract

Objective

Weight gain after kidney transplantation (Tx) is considered a risk factor for poor outcomes. Increased oxidative stress is associated with not only chronic renal disease and Tx, but also obesity and cardiovascular disease. The aim of this pilot study was to test whether oxidative stress is related to weight gain at 12-months after kidney Tx and to obtain preliminary insight into potential mechanisms involved.

Design & Methods

Recipients (n=33) were classified into two groups; weight loss and weight gain, based on their weight changes at 12-months post-transplant. Total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) and lipid peroxidation (TBARS) were measured to evaluate oxidative stress from plasma at baseline and 12-months. A secondary data analysis was conducted to identify potential gene regulation.

Results

Seventeen recipients lost (−6.63±5.52 kg), and sixteen recipients gained weight (8.94±6.18 kg). TAOC was significantly decreased at 12-months compared to baseline for the total group, however, there was no significant difference between groups at either time point. TBARS was higher in weight gain group, at both time points, and it was significantly higher at 12-months (p=0.012). Gene expression profiling analysis showed that 7 transcripts annotated to reactive oxygen species related genes in adipose tissue were expressed significantly lower in weight gain group at baseline, which might be a negative feedback mechanism to reduce oxidative stress.

Conclusion

These results may indicate that elevated oxidative stress (TBARS) is associated with weight gain after kidney Tx and that incorporating early clinical prevention strategies known to decrease oxidative stress could be recommended.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, oxidative stress, weight gain

1. Introduction

Epidemiological data from the past decade suggest that the global burden of patients with renal failure who receive kidney transplantation exceeds 1.4 million and this number is growing by about 8% a year [1]. Rapid advances have been made in decreasing acute rejection rates and improving short-term graft survival in kidney transplant recipients with most centers reporting survival rates of greater than 90% at 1 year [2, 3]. However, long-term success has been difficult to accomplish as evident by the marginal increase in patients and graft survival rates over the past 15 years from a half-life of 6.6 years in 1989 to an approximately 8.8 years in 2005 [4].

Kidney transplantation recipients are highly exposed to the risk of oxidative stress, which is an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species and the antioxidants defense system. Reactive oxygen species is easily increased by end stage renal disease, which most recipients commonly suffered for a long time before transplant. Ischemia-reperfusion injury and long-term use of immunosuppressant drugs after transplantation also increase oxidative stress [5]. Moreover, oxidative stress is known to play an important role in the pathogenesis of cancer, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular diseases, which are common comorbidities of transplantation recipients [5, 6].

Oxidative stress is also associated with obesity, which commonly occurs following kidney transplantation. Although the mechanism is unclear, numerous studies indicate that oxidative stress is elevated overall in obese individuals compared to non-obese in the general population [7, 8]. For kidney transplant recipients, weight gain and obesity are significant issues, which might complicate long-term graft success and contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease [9, 10]. It is reported that kidney transplant recipients experience a mean weight gain of 10–12 kg during the first year after transplantation [9, 11]. Studies conducted to reveal the cause of the dangerous weight gain have been inconclusive attributing it to a combination of multiple factors. Three primary factors, inappropriate dietary intake, reduced physical activity, and immunosuppressant drug therapy, were frequently considered as either its cause or therapeutic solution [12, 13].

Recently, we explored a potential genomic contribution by examining the association between gene expression from adipose tissue obtained during kidney transplantation and weight gain after transplantation [14]. This study reported that expression levels of 1,553 genes were significantly associated with weight change. In the gene list related to weight gain, there were oxidative stress-related genes including NADH dehydrogenase, ATP synthase, and glutathione s-transferase kappa 1. It was reported that these genes might affect to weight changes in the animal study and clinical trials [15–17].

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that oxidative stress is associated with weight gain after kidney transplantation. In order to test our hypothesis, we conducted an exploratory study to measure and compare oxidative stress level from plasma obtained at the time of transplantation (baseline) and 12-months after transplantation in two groups, recipients who gained vs. those who lost weight in 12-months.

2. Materials and methods

From 2006 to 2011, investigators from a regional MidSouth transplant institute recruited 153 kidney transplant recipients to participate in a larger study examining genetic and environmental factors (e.g. diet and physical activity) associated with weight gain following transplantation. This study is a substudy with 37 recipients whose plasma samples were collected at both baseline and 12-months after transplantation. Four recipients were excluded due to their multi-racial ancestry, thus, final analysis was done with 33 kidney transplantation recipients.

All adults approved for kidney transplantation surgery at the transplant institute were eligible for participation in the parent study regardless of race and gender. However, recipients were excluded if at time of kidney transplantation they were taking prednisone or other immunosuppressant therapy, to control for any effect of pre-transplantation immunosuppressant therapy on baseline weight. This research was approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Institutional Review Board and the Office of Human Subject Research Protection at the National Institution of Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all recipients.

Demographic features and clinical information including age, gender, race, weight, body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), laboratory results and medication history were obtained from all participants at the time of transplant (baseline) and 12-months after transplant. Dietary data were obtained by experienced research team members who were trained in gathering recall data. Briefly, interviews were conducted approximately two weeks following transplantation because this period most likely reflected the return to regular eating patterns. Physical activity recall was elicited by telephone interview using the well-established Physical Activity Report [18]. Based on participants’ response, five subsets of physical activity (sleep, light, moderate, hard, and very hard) were recorded, and average energy expenditure was determined with it.

Blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein into EDTA and sodium-heparin tubes at baseline and 12-months after transplantation. Plasma was separated immediately after the blood collection by centrifugation at 1,000g for 10min at 4°C and stored at −80°C until assay.

The ABTS assay was used to determine the total antioxidants capacity (TAOC). This assay relies on the ability of antioxidants in the plasma to inhibit the oxidation of 3-ethylbenzothiazo-line 6-sulfonate (ABTS) by metmyoglobin. Antioxidants suppressed the production of the radical cation in a concentration dependent manner and the color intensity decreases proportionally, which was determined at 405nm with SpectraMax® M3 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Trolox, a water-soluble vitamin E analogue, serves as a standard or control antioxidant, and the capacity of the antioxidants was quantified as mM Trolox equivalents. Detailed procedure was followed by manufacturer’s direction (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

The thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay was conducted to measure the lipid peroxidation contents in plasma. It was determined by malondialdehyde (MDA) production and assayed based on the reaction with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and MDA. The TBA-MDA adducts formed by the reaction under high temperature and acidic condition were measured fluorometrically at an excitation wavelength of 530nm and an emission wavelength of 550nm with SpectraMax® M3 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Readings were converted into μM using the calibration curve. Detailed procedure was followed by manufacturer’s direction (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI).

To explore the gene expression profiles of oxidative stress-related genes from kidney transplantation recipients, data obtained from a previous substudy were analyzed. The study was fully described by Cashion et al. [14]. In the previous study, gene expression profiling was conducted with GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST Arrays (Affymetrix Inc, Santa Clara, CA) from adipose tissue and whole blood obtained at the time of transplant. Among twenty six recipients of the previous study, twelve (46.15%) were included in the current study. Briefly, the subject characteristics (n=26) are; eleven were men (42.13%), fifteen were African American (57.69%), and mean age was 47.73±4.07 years old. Recipients gained a mean of 8.15±21.01 kg by 12-months post-transplant; ten recipients showed weight loss (−10.34±11.65 kg) and sixteen recipients showed weight gain (19.71±16.85 kg, p=0.000049). Age, gender, race and immunosuppressant drugs were not significantly different between weight loss and weight gain groups. Oxidative stress-related genes were selected using DAVID bioinformatics resources (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) [19]. From 33,297 transcripts profile, 648 genes were chosen from oxidation reduction process category of Gene Ontology (632 genes) and oxidoreductase category of SP PIR KEYWORDS (557 genes). Then, 648 genes were classified with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) into 8 categories, and 92 genes were selected from oxidative phosphorylation and glutathione metabolism category. The expression of those genes was compared between weight loss group and weight gain group.

Independent/paired t-test and Chi-square test were used to identify significant differences. Pearson product moment correlation was used to estimate the relationship between TBARS and body weight. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results

Thirty-three transplant recipients were included in this study and their general characteristics are given in Table 1; twenty-one were men (63.64%), fifteen were African American (45.45%) and mean age was 52.24±10.42 years old. Body weight and BMI were measured at both baseline and 12-months. It was shown that 66.67% were overweight (BMI, 25.00 to 29.99 kg/m2) or obese (BMI, ≥30.00 kg/m2) at 12-months after transplantation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of recipients at time of transplant (baseline) and 12-months after transplant

| Entire recipients n=33 | Weight loss group n=16 | Weight gain group n=17 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | baseline | 12-months | baseline | 12-months | baseline | 12-months | |

| Age (year) | 52.24±10.42 | 55.88±9.47 | 48.82±10.36 | ||||

| Gender (Male) | n (%) | 21 (63.64%) | 11 (68.75%) | 10 (58.82%) | |||

| Race | AA, n (%) | 15 (45.45%) | 8 (50.00%) | 7 (41.18%) | |||

| C, n (%) | 18 (54.55%) | 8 (50.00%) | 10 (58.82%) | ||||

| Hypertension | n (%) | 33 (100.00%) | 29 (93.55%) | 16 (100.00%) | 14 (93.33%) | 17 (100.00%) | 15 (93.75%) |

| Diabetes | n (%) | 5 (15.15%) | 8 (25.00%) | 2 (12.50%) | 5 (31.25%) | 3 (17.65%) | 3 (17.65%) |

| Body weight (Kg) | 83.57±18.42 | 84.96±23.04 | 78.86±18.55# | 72.24±16.99#* | 88.00±17.69# | 96.94±21.84#* | |

| Δ Body weight (Kg) | 1.39±9.79 | −6.63±5.52* | 8.94±6.18* | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.54±4.48 | 28.94±6.05 | 27.34±4.35# | 25.05±4.14#* | 29.67±4.43# | 32.60±5.26#* | |

| Δ BMI (kg/m2) | 0.40±3.23 | −2.30±1.90* | 2.94±1.83* | ||||

| Prednisone (mg/day) | 18.03±3.94# | 5.16±2.95# | 17.81±3.64# | 5.67±4.17# | 18.24±4.31# | 4.69±0.85# | |

| Tacrolimus (mg/day) | 4.52±2.44 | 5.58±3.57 | 4.63±2.19 | 5.19±3.99 | 4.41±2.72 | 5.94±3.20 | |

| Mycophenolate (mg/day) | 1769. 70±343.37# | 1109.09±815.72# | 1770.00±406.74# | 953.75±616.13# | 1769.41±284.09# | 1255.29±963.37# | |

| Energy intake (cal) | 1768.39±734.90 | 1791.16±772.91 | 1499.22±491.98* | 1578.46±558.34 | 2021.73±844.15* | 1991.36±902.60 | |

| Δ Energy intake (cal) | 22.78±964.54 | 79.24±652.12 | −30.37±1206.56 | ||||

| Ave. daily energy expenditure | 32.34±1.30# | 34.25±4.32# | 32.93±1.33* | 35.35±5.85 | 31.79±1.01#* | 33.22±1.71# | |

| Δ Ave. daily energy expenditure | 1.91±4.41 | 2.42±6.18 | 1.44±1.65 | ||||

Note : Data are presented as mean±SD. SD=standard deviation, AA=African American, C=Caucasian, BMI=body mass index, kg=kilogram, m=meter, Δ =change.

means p<0.05 between weight loss and weight gain group.

means p<0.05 between baseline and 12-months in the same group.

Recipients were classified into two groups by the change of body weight in 12-months (Table 1 and Figure 1). Among 33 recipients, seventeen recipients showed weight loss (−6.63±5.52 kg), whereas sixteen recipients showed weight gain (8.94±6.18 kg) at 12-months post-transplant. Most importantly, although all recipients were at a normal BMI, or slightly above, over 36% (n=12) gained greater than 5% of their baseline weight and 27% gained greater than 10% (n=9) of their baseline weight. This demonstrates the significant increase in weight experienced by some recipients, which can result in adverse comorbid conditions. BMI and body weight were not significantly different at baseline between groups, however as expected, at 12-months, both were significantly higher in weight gain group.

Figure 1. Changes of weight and body mass index (BMI) at 12-months after kidney transplantation.

Body weight (A) and BMI (B) were significantly increased in weight gain group compared to weight loss group after 12-months of kidney transplantation. Values are means±SE.

Other demographic characteristics including age, race, gender, hypertension, and diabetes status were not found to be significantly different between groups (Table 1). A standard immunosuppressant post-transplant protocol was followed, therefore, the medications were not significantly different between weight loss and weight gain groups. In general, prednisone (20 mg/day) was prescribed at transplant and tapered to 5 mg/day by 12-months. Over 90% of recipients were also taking tacrolimus and mycophenolate at either time point. No recipients were prescribed cyclosporine.

Energy intake did not significantly change from baseline to 12-months for the total group. Interestingly, it was significantly higher in weight gain group at baseline compared to the weight loss group (p=0.039), however, this difference disappeared at 12-months. The average daily energy expenditure significantly increased from baseline to 12-months for the total group (p=0.018). When examined by groups, it was significantly higher in weight loss group at baseline compared to weight gain group (p=0.009), however, there was no difference between groups at 12-months.

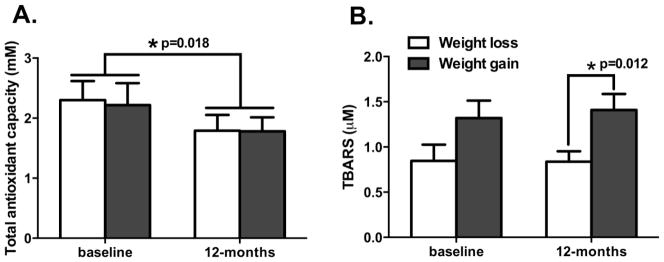

To determine whether oxidative stress was associated with body weight, total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) and lipid peroxidation (TBARS) were measured from plasma which was collected at baseline and 12-months after transplantation (Figure 2). Overall, TAOC was significantly decreased at 12-months (1.79±0.98 mM) compared to baseline (2.26±1.37 mM) for the total group (p=0.018), however, it was not significantly different between weight loss and gain groups at both baseline and 12-months. TBARS did not significantly change from baseline to 12 months for the total group (1.09±0.79 μM at baseline and 1.13±0.68 μM at 12-months, p=0.787). However, when examined by groups, it was relatively higher in the weight gain group compared to the weight loss group at baseline (1.32±0.79 μM and 0.85±0.72 μM, respectively; p=0.082) and significantly higher in the weight gain group compared to the weight loss group at 12-months (1.41±0.18 μM and 0.84±0.12 μM, respectively; p=0.012).

Figure 2. Changes of total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) and lipid peroxidation (TBARS) at 12-months after kidney transplantation.

A. Total antioxidant capacity was significantly decreased at 12-months compared to baseline from all recipients, however, it was not significantly different between weight loss and weight gain groups at baseline and 12-months after transplantation. B. TBARS was increased in weight gain group in baseline of transplantation (p=0.082) and it was significantly increased at 12-months after transplantation (p=0.012). Values are means±SE.

Baseline body weight was not correlated with baseline TBARS (r=0.053, p=0.769), however, 12-months body weight was significantly correlated with 12-months TBARS (r=0.453, p=0.008). Correlation between immunosuppressant and TBARS or TAOC was also tested. Dosage of each drug was not correlated with TBARS or TAOC at both time points, although change of tacrolimus dose was significantly correlated with change of TBARS (r=−0.398, p=0.022).

To begin exploring mechanistic pathways, we conducted a secondary database analysis from our previous data [14] to identify oxidative stress-related genes differentially expressed between transplant recipients who lost and gained weight from two different tissues, adipose tissue and whole blood (Table 2). In the adipose tissue gene expression profile, transcripts annotated to seven genes (MT-TK, NDUFS2, SDHD, UQCRC2, NDUFA5, ND2, and CCDC104) and one unannotated transcript were expressed significantly lower in weight gain group. Interestingly, transcripts annotated to three genes (IDH1, COX1 and CYTB) showed opposite trend in the whole blood gene expression profile, without statistical significance, i.e. higher expression in weight gain group.

Table 2. Candidate genes and their transcript expression level at baseline from adipose tissue and whole blood.

from a subgroup of 26 recipients from the previous study [14], 46.15% were included in the current study.

| Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Weight loss group | Weight gain group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose tissue | NDUFS2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 2, 49kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase) | 9.58±0.22 | 9.33±0.20 | 0.00834712 |

| UQCRC2 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein II | 10.67±0.21 | 10.42±0.31 | 0.02713103 | |

| MT-TK | Mitochondrially encoded tRNA lysine | 10.44±0.46 | 9.98±0.51 | 0.02814656 | |

| SDHD | Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit D, integral membrane protein | 8.49±0.24 | 8.23±0.32 | 0.03643888 | |

| MTND2 | Mitochondrially encoded NADH dehydrogenase 2 | 11.43±0.38 | 11.12±0.34 | 0.04000202 | |

| NDUFA5 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 5, 13kDa | 8.56±0.15 | 8.33±0.32 | 0.04238961 | |

| CCDC104 | Coiled-coil domain containing 104 | 12.81±0.20 | 12.64±0.19 | 0.04867911 | |

| Whole blood | IDH1 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+), soluble | 9.33±0.46 | 9.61±0.25 | 0.05656491 |

| COX1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 | 13.52±0.16 | 13.62±0.10 | 0.08233270 | |

| CYTB | Cytochrome b | 13.52±0.17 | 13.62±0.12 | 0.09276942 |

4. Discussion

Significant weight gain was a post-transplant reality for over 30% of our sample, with approximately 27% gaining more than 10% of their baseline weight. For those individuals, complications associated with oxidative stress are concern. In this study, we demonstrated that oxidative stress is associated with weight change at 12-months after kidney transplantation. We compared oxidative stress levels by measuring total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) and lipid peroxidation (TBARS) between weight loss and weight gain groups at baseline and 12-months of post-transplant. TAOC was not different between groups at either time point, however, TBARS showed a noticeable higher trend in the weight gain group at baseline, and was significantly greater at 12-months, compared to the weight loss group. Weight gain at 12-months was not related to immunosuppressant administration, energy intake and physical activity between groups. This study would be the first demonstration to show that oxidative stress (TBARS) is associated with body weight at 12-months after kidney transplantation.

Our findings are congruent with other studies which reported decreased TAOC at 12 days [20], 6 months [21] and 12 months [22] after kidney transplantation. However, the mechanism which induced decreased TAOC is controversial. It was suggested that it might be caused by the reduction of uric acid which may lead to major variations of the internal redox state [20]. Meanwhile, it was also suggested that TAOC may not be related or insufficiently sensitive to oxidative stress after kidney transplantation [21, 22]. Immunosuppressant is considered to be an important factor for the change of TAOC, however, the effect of immunosuppressant is also controversial. It was reported that recipients treated with cyclosporine had significantly greater TAOC compared with those treated with tacrolimus [23], while another study found no significant difference in TAOC between recipients treated with cyclosporine versus tacrolimus [22]. Because over 90% of recipients in our study were treated with tacrolimus and mycophenolate, we could not define the role of each medication to TAOC in this study. Since previous study results lack consensus on whether TAOC is a useful parameter for oxidative stress and how immunosuppressant therapies affect TAOC, other parameters such as TBARS need to be considered along with TAOC to determine the role of oxidative stress on weight gain.

The TBARS was not significantly changed at 12-months compared to baseline for all recipients. In contrast, other studies reported significantly increased TBARS at 2 weeks [24] and 52 weeks [25] or significantly decreased TBARS at 28 days [26] and 1 year [27] after kidney transplantation. The lack of consistency in results might be explained by the variation among studies in measurement time point and characteristics of the population, though most studies overall suggested that TBARS change might be related to the type of immunosuppressant administration. It is known that calcineurin-inhibitors, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus may induce oxidative stress, in contrast, mycophenolate ameliorates it [5], although tacrolimus is known to have more beneficial effects on the level of oxidative stress compared to cyclosporine [28]. In our study, we observed that immunosuppressant therapies were not correlated to TBARS at both time points, however a decrease in tacrolimus dosage was associated with an increase in TBARS, which is consistent with finding with another study [28]. Considering all recipients were treated with mycophenolate and tacrolimus, it may not represent the direct correlation between tacrolimus and TBARS. Taken together with decreased TAOC, it may suggest that oxidative stress might be increased at 12-months post-transplant in this study for the total group, although the background mechanism related to TBARS is not clear.

Oxidative stress is an important factor related to weight gain or obesity, which is supported by the results of animal and clinical studies [7, 29]. Many studies in the general population have shown that TBARS was significantly higher in obese groups, and it is known that accumulation of oxidative stress might be induced by increased adipose tissue at the early stage of weight gain [7, 30]. For kidney transplant recipients, Chan et al. proposed that increased BMI induces sarcopenic obesity, then decreased muscle mass may cause impaired muscle-based oxidative mechanism, which leads to break down oxidative defense system [31]. Our study also showed that TBARS was significantly higher in the weight gain group at 12-months as compared to the weight loss group, but that same significant difference was not present at baseline. Notably there is a similar pattern seen with body weight and BMI, such that there is a significant difference between groups at 12-months that was not present at baseline. Based on this finding, we suggest that TBARS is associated with weight gain after kidney transplantation.

Many studies have been conducted with transplant recipients to determine factors related to weight gain. Some studies demonstrated that gender differences may impact weight gain or obesity [32, 33]. And some studies showed African Americans gain weight easier than Caucasians [34, 35]. In our study, gender and race were not statistically different between weight loss and gain group suggesting that it may not be a primary factor affecting weight changes in the first year following kidney transplantation. Energy intake is also considered as a key factor to induce weight gain and obesity as the improved appetite and sense of well-being may lead to augmented caloric intake. There are some reports that nutrition intervention may assist to inhibit weight gain after transplantation [36, 37]. In our study, there was no difference in energy intake between weight loss and weight gain group. Rather, energy intake was slightly decreased in weight gain group at 12-months. This could be explained by the possibility that some recipients may make an effort to reduce their body weight to avoid complications from obesity, which could be supported by the significantly increased average daily energy expenditure in the weight gain group at 12 month (p=0.002). Therefore, increased energy intake and decreased physical activity could be ruled out as a factor for the weight gain in our population. Immunosuppressant therapy is also a candidate to increase the body weight after transplantation, however, its effect on weight gain is also controversial [13, 38, 39]. In our study, the application dosage of prednisone, tacrolimus and mycophenolate was statistically similar between groups. Taken together, we suggest that gender, race, energy intake, physical activity and immunosuppressant medication may not have any significant impact on weight changes in this study.

Expression of reactive oxygen species (ROS) related gene profile was different between adipose tissue and whole blood. Unexpectedly, the expression of ROS related genes in the adipose tissue was significantly lowered in weight gain group. On the contrary, in the whole blood, the expression of ROS related genes showed increased tendency in weight gain group. Similar trends were shown in both oxidative stress (TBARS) and body weight, which were higher in weight gain group at the baseline. Based on this, we suggest that increased body weight might be associated with increased oxidative stress at the baseline. And these modestly activated factors in whole blood and body weight might induce a lower expression of ROS related genes in adipose tissue in weight gain group. We suggest that it might be because of a negative feedback mechanism that maintains the redox homeostasis after transplantation. Due to this mechanism in our body, excessive increase of oxidative stress after transplantation could be avoided in the weight gain group. It may support our result that TBARS was almost the same at 12-months in the weight gain group.

In this study, our small sample size is a limitation. Another limitation is the use of different samples to obtain gene expression data, even though almost half of recipients are in both studies. A larger population is needed to investigate how oxidative stress is associated with weight gain after transplantation.

Our study is the first to show that oxidative stress is increased in kidney transplant recipients who gain weight. We suggest that oxidative stress may play a role in weight gain after kidney transplantation. In combination, weight gain and oxidative stress, further increases the risk of cardiovascular complications and may explain some of the underlying physiology related to these events. It may suggest the future therapeutic direction, such as antioxidant therapy to prevent cardiovascular complications after kidney transplantation.

Highlights.

Recipients who gained vs. lost weight after kidney transplant were compared.

Total antioxidant capacity and lipid peroxidation were measured from plasma.

Lipid peroxidation (TBARS) was significantly increased in weight gain group.

Expression of ROS-related genes were explored.

Elevated oxidative stress might be associated with post-transplant weight gain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colleagues at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee for help in patient recruitment, plasma sample collection and genomic data management. Research reported in this study was supported by National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01NR009270, and National Institute of Nursing Research intramural funding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Young-Eun Cho, Email: young-eun.cho@nih.gov.

Hyung-Suk Kim, Email: kimhy@mail.nih.gov.

Chen Lai, Email: laichi@mail.nih.gov.

Ansley Stanfill, Email: stanfill@pitt.edu.

Ann Cashion, Email: ann.cashion@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Womer KL, Kaplan B. Recent developments in kidney transplantation--a critical assessment. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9:1265–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashiani AA, Rajaeefard A, Hasanzadeh J, Kakaei F, Behbahan AG, Nikeghbalian S, et al. Ten-year graft survival of deceased-donor kidney transplantation: A single-center experience. Renal failure. 2010;32:440–7. doi: 10.3109/08860221003650347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briggs JD. Causes of death after renal transplantation. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2001;16:1545–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.8.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb KE, Lodhi S, Meier-Kriesche HU. Long-term renal allograft survival in the united states: A critical reappraisal. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2011;11:450–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nafar M, Sahraei Z, Salamzadeh J, Samavat S, Vaziri ND. Oxidative stress in kidney transplantation: Causes, consequences, and potential treatment. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2011;5:357–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cottone S, Palermo A, Vaccaro F, Vadala A, Buscemi B, Cerasola G. Oxidative stress and inflammation in long-term renal transplanted hypertensives. Clinical nephrology. 2006;66:32–8. doi: 10.5414/cnp66032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:1752–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankhla M, Sharma TK, Mathur K, Rathor JS, Butolia V, Gadhok AK, et al. Relationship of oxidative stress with obesity and its role in obesity induced metabolic syndrome. Clin Lab. 2012;58:385–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clunk JM, Lin CY, Curtis JJ. Variables affecting weight gain in renal transplant recipients. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2001;38:349–53. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.26100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baum CL. Weight gain and cardiovascular risk after organ transplantation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001;25:114–9. doi: 10.1177/0148607101025003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel MG. The effect of dietary intervention on weight gains after renal transplantation. Journal of renal nutrition : the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998;8:137–41. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(98)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Oliveira CM, Moura AE, Goncalves L, Pinheiro LS, Pinheiro FM, Jr, Esmeraldo RM. Post-transplantation weight gain: Prevalence and the impact of steroid-free therapy. Transplantation proceedings. 2014;46:1735–40. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elster EA, Leeser DB, Morrissette C, Pepek JM, Quiko A, Hale DA, et al. Obesity following kidney transplantation and steroid avoidance immunosuppression. Clinical transplantation. 2008;22:354–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cashion A, Stanfill A, Thomas F, Xu L, Sutter T, Eason J, et al. Expression levels of obesity-related genes are associated with weight change in kidney transplant recipients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lomba A, Martinez JA, Garcia-Diaz DF, Paternain L, Marti A, Campion J, et al. Weight gain induced by an isocaloric pair-fed high fat diet: A nutriepigenetic study on fasn and ndufb6 gene promoters. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2010;101:273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goncalves VF, Zai CC, Tiwari AK, Brandl EJ, Derkach A, Meltzer HY, et al. A hypothesis-driven association study of 28 nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes with antipsychotic-induced weight gain in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1347–54. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theodoratos A, Blackburn AC, Coggan M, Cappello J, Larter CZ, Matthaei KI, et al. The impact of glutathione transferase kappa deficiency on adiponectin multimerisation in vivo. International journal of obesity. 2012;36:1366–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the five-city project. American journal of epidemiology. 1985;121:91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using david bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahmatkesh M, Kadkhodaee M, Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Ghaznavi R, Hemati M, Seifi B, et al. Oxidative stress status in renal transplant recipients. Experimental and clinical transplantation : official journal of the Middle East Society for Organ Transplantation. 2010;8:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vostalova J, Galandakova A, Svobodova AR, Orolinova E, Kajabova M, Schneiderka P, et al. Time-course evaluation of oxidative stress-related biomarkers after renal transplantation. Renal failure. 2012;34:413–9. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.649658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zadrazil J, Horak P, Strebl P, Krejci K, Kajabova M, Schneiderka P, et al. In vivo oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-ldl) aopp and tas after kidney transplantation: A prospective, randomized one year study comparing cyclosporine a and tacrolimus based regiments. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 2012;156:14–20. doi: 10.5507/bp.2012.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chrzanowska M, Kaminska J, Glyda M, Duda G, Makowska E. Antioxidant capacity in renal transplant patients. Die Pharmazie. 2010;65:363–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez Fernandez R, Martin Mateo MC, De Vega L, Bustamante Bustamante J, Herrero M, Bustamante Munguira E. Antioxidant enzyme determination and a study of lipid peroxidation in renal transplantation. Renal failure. 2002;24:353–9. doi: 10.1081/jdi-120005369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joannides R, Monteil C, de Ligny BH, Westeel PF, Iacob M, Thervet E, et al. Immunosuppressant regimen based on sirolimus decreases aortic stiffness in renal transplant recipients in comparison to cyclosporine. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2011;11:2414–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vural A, Yilmaz MI, Caglar K, Aydin A, Sonmez A, Eyileten T, et al. Assessment of oxidative stress in the early posttransplant period: Comparison of cyclosporine a and tacrolimus-based regimens. American journal of nephrology. 2005;25:250–5. doi: 10.1159/000086079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joo DJ, Huh KH, Cho Y, Jeong JH, Kim JY, Ha H, et al. Change in serum lipid peroxide as an oxidative stress marker and its effects on kidney function after successful kidney transplantation. Transplantation proceedings. 2010;42:729–32. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dlugosz A, Srednicka D, Boratynski J. the influence of tacrolimus on oxidative stress and free-radical processes. Postepy higieny i medycyny doswiadczalnej. 2007;61:466–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincent HK, Taylor AG. Biomarkers and potential mechanisms of obesity-induced oxidant stress in humans. International journal of obesity. 2006;30:400–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dandona P, Mohanty P, Ghanim H, Aljada A, Browne R, Hamouda W, et al. The suppressive effect of dietary restriction and weight loss in the obese on the generation of reactive oxygen species by leukocytes, lipid peroxidation, and protein carbonylation. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2001;86:355–62. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan W, Bosch JA, Jones D, McTernan PG, Phillips AC, Borrows R. Obesity in kidney transplantation. Journal of renal nutrition : the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation. 2014;24:1–12. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandes JF, Leal PM, Rioja S, Bregman R, Sanjuliani AF, Barreto Silva MI, et al. Adiposity and cardiovascular disease risk factors in renal transplant recipients: Are there differences between sexes? Nutrition. 2013;29:1231–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fall T, Hagg S, Ploner A, Magi R, Fischer K, Draisma HH, et al. Age- and sex-specific causal effects of adiposity on cardiovascular risk factors. Diabetes. 2015 doi: 10.2337/db14-0988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cashion AK, Sanchez ZV, Cowan PA, Hathaway DK, Lo Costello A, Gaber AO. Changes in weight during the first year after kidney transplantation. Progress in transplantation. 2007;17:40–7. doi: 10.1177/152692480701700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among us adults, 1999–2000. Jama. 2002;288:1723–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cupples CK, Cashion AK, Cowan PA, Tutor RS, Wicks MN, Williams R, et al. Characterizing dietary intake and physical activity affecting weight gain in kidney transplant recipients. Progress in transplantation. 2012;22:62–70. doi: 10.7182/pit2012888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otsu M, Hamatani R, Hattori M. Nutrient intake and dietary habit in pediatric, adolescent, and young adult kidney transplant recipients. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai shi. 2013;55:1320–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Ham EC, Kooman JP, Christiaans MH, Nieman FH, van Hooff JP. Weight changes after renal transplantation: A comparison between patients on 5-mg maintenance steroid therapy and those on steroid-free immunosuppressive therapy. Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 2003;16:300–6. doi: 10.1007/s00147-002-0502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodle ES, Peddi VR, Tomlanovich S, Mulgaonkar S, Kuo PC, Investigators TS. A prospective, randomized, multicenter study evaluating early corticosteroid withdrawal with thymoglobulin in living-donor kidney transplantation. Clinical transplantation. 2010;24:73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]