Abstract

Type 1 innate lymphocytes comprise two developmentally divergent lineages, type 1 helper innate lymphoid cells (hILC1s) and conventional NK cells (cNKs). All type 1 innate lymphocytes (ILCs) express the transcription factor T-bet, but cNKs additionally express Eomesodermin (Eomes). We show that deletion of Eomes alleles at the onset of type 1 ILC maturation using NKp46-Cre imposes a substantial block in cNK development. Formation of the entire lymphoid and non-lymphoid type 1 ILC compartment appears to require the semi-redundant action of both T-bet and Eomes. To determine if Eomes is sufficient to redirect hILC1 development to a cNK fate, we generated transgenic mice that express Eomes when and where T-bet is expressed using Tbx21 locus control to drive expression of Eomes codons. Ectopic Eomes induces cNK-like properties across the lymphoid and non-lymphoid type 1 ILC compartments. Subsequent to their divergent lineage specification, hILC1s and cNKs thus possess substantial developmental plasticity.

Introduction

Innate lymphoid cells are enriched at mucosal barriers in close proximity to epithelial surfaces, where they exert crucial functions during infection, tissue injury, and inflammation. Type 1 innate lymphocytes (ILCs) express the NK1.1 and NKp46 lineage antigens as well as the transcription factor T-bet. Type 1 ILCs can be further subdivided into discrete populations based on expression of Eomesodermin (Eomes), a close homolog of T-bet (1, 2). Eomes+ conventional NK cells (cNKs) express integrin CD49b (DX5) and MHC class I-specific Ly49 receptors and circulate through lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs. In contrast, Eomes− helper innate lymphoid cells (hILC1s) express integrin CD49a and are anchored to their tissues and mucosal sites of origin (1–7). hILC1s and cNKs are thought to arise from separate lymphoid progenitors (6, 8). Nonetheless, type 1 ILC lineages are closely related transcriptionally and temporal deletion of Eomes from cNKs unveils latent hILC1-like characteristics (1, 9). We used genetic approaches to test the necessity and sufficiency of Eomes to determine the outcome of type 1 ILC maturation. Our results lead us to the conclusion that Eomes expression is a key determinant of cNK versus hILC1 maturation following lineage specification.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions and used in accordance with the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee’s guidelines. C57BL/6 Eomesflox/flox, Tbx21flox/flox, Tbx21−/− (10, 11), NKp46-Cre+ (12), and Id2hCD5/hCD5 reporter (13) mice were generated as previously described. They were bred locally to obtain the compound genotypes Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+, Tbx21flox/flox NKp46-Cre+, and Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ Tbx21−/−.

Detailed characterization of the Tbx21-Eomes transgenic (Tg) mouse strain will appear elsewhere. Briefly, Eomes cDNA followed by an SV40-PolyA site was inserted into the ATG translational start site of T-bet in the Tbx21 BAC clone RP23-237M14 (CHORI) by Red/ET recombination technology (Gene Bridges). This strategy enabled T-bet regulatory elements to drive Eomes expression instead of T-bet expression from the transgenic allele. The BAC construct was used for pronuclear injection of C57BL/6 zygotes. For some experiments, transgenic mice were crossed to Id2hCD5/hCD5 reporter mice that express human CD5 from an IRES-driven cassette knocked-in to the 3′-UTR of Id2 (13). Furthermore, transgenic mice were crossed to Tbx21−/− mice for some analyses. Aged transgenic mice had no evidence of skin lesions, intestinal inflammation, or hepatosplenomegaly.

Cell Isolation and flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from liver, spleen, bone marrow, uterus, salivary gland, thymus, and lung tissues. Liver lymphocytes were isolated at the interphase of a 40/60% Percoll gradient (1). Uterus and salivary gland were digested in the presence of DNase I and collagenase D or liberase TL (5, 7), while lung digestion additionally incorporated trypsin inhibitor. Cells were stained with a LIVE/DEAD fixable dead cell stain kit (Invitrogen) and blocked with antibodies against CD16/CD32 (BD) prior to staining with antibodies for CD3, CD11b, CD27, CD43, CD122, human CD5, integrin αv, KLRG1, Ly49G2, Ly49H, NKp46, and TRAIL (eBioscience); CD19, CD49a, CD49b, CD127, Ly49D, Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1), NK1.1, NKG2A/C/E, and TER-119 (BD). Cells were treated with cytofix/cytoperm kits prior to staining with antibodies for the transcription factors T-bet (eBioscience) and Eomes (eBioscience) or the cytokine TNF-α (BD).

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were calculated using Prism (GraphPad Software). Differences between groups were quantified using the unpaired t-test. Statistical significance was reached at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

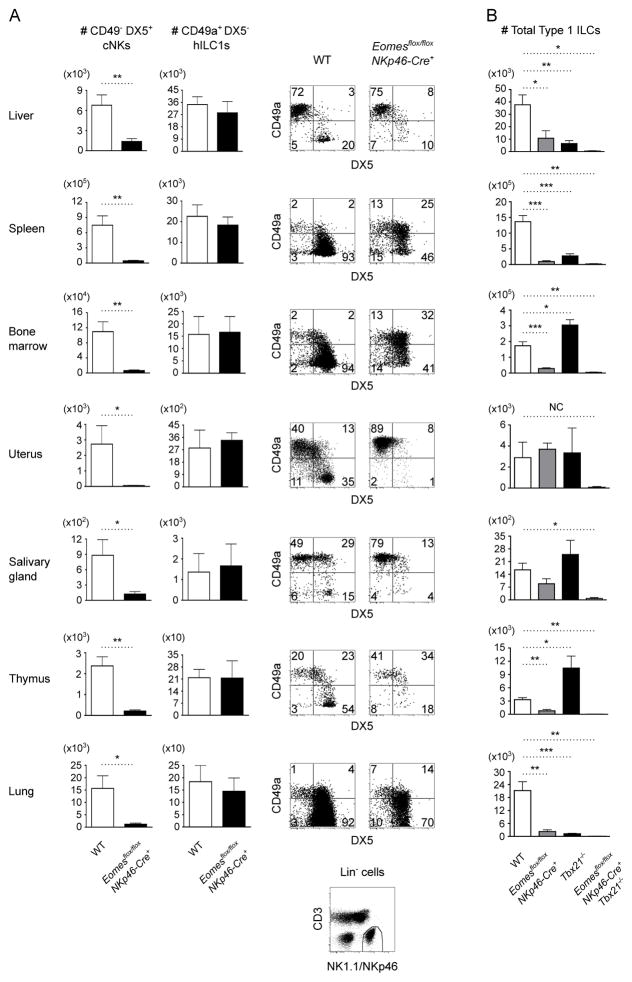

Deletion of Eomes in NKp46+ ILCs blocks cNK differentiation

Within various lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues examined, we could identify hILC1s and cNKs among lineage-negative, NK1.1+ NKp46+ cells based on reciprocal expression of integrins CD49a and CD49b (DX5), respectively (Fig. 1A). We previously examined cNK development in mice with pan-hematopoietic deficiency of Eomes (1). To determine if Eomes expression at the onset of ILC development is necessary for cNK differentiation, we intercrossed Eomesflox/flox and NKp46-Cre+ mice (12). Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ mice had a substantial loss of CD49a− DX5+ cNKs (Fig. 1A), which supports the prior suggestion that Eomes is genetically upstream of CD49b induction (1). Remnant NK1.1+ NKp46+ cells in Eomes conditional knockout (cKO) mice were CD49a+ DX5−, CD49a+ DX5+, or CD49a− DX5+ cells (Fig. 1A), and the persistence of these cells did not appear to result from inefficient deletion of Eomes (Supplemental Fig. 1A). These findings are consistent with a role for Eomes upstream of CD49a repression, which is supported by prior evidence of direct binding of Eomes to the locus encoding CD49a (14). Examination of TRAIL, CD127, and integrin αv confirmed that deletion of Eomes shifts the balance of type 1 ILCs from cNKs to helper-like ILC1s (Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Loss of Eomes in NKp46+ ILCs impairs cNK development.

(A) Representative flow cytometry of CD49a+ DX5− hILC1 and CD49a− DX5+ cNK subsets among type 1 ILCs [Lin (CD3, Gr-1, TER-119, CD19) − NK1.1+ NKp46+] from the indicated organs of wild-type (WT) and Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ mice (n=4–5 mice per genotype). Absolute numbers of hILC1s and cNKs are indicated. The NK1.1/NKp46 gate is shown at the bottom. (B) Absolute numbers of total type 1 ILCs from the indicated organs of WT, Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+, Tbx21−/−, and Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ Tbx21−/− mice (n=3–5 mice per genotype). Statistics were not calculated (NC) for the difference between WT and Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ Tbx21−/− uterus because the Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ Tbx21−/− uterus group represents the average of 2 mice. All other data are mean ± SEM representative of 3–5 independent experiments; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To test the contribution of T-bet to residual type 1 ILC development in Eomes cKO mice, we examined Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ Tbx21−/− mice (Fig. 1B). We used mice with a germline Tbx21 deletion because Tbx21flox/flox NKp46-Cre+ mice underwent substantial development or expansion of hILC1s that escaped Tbx21 deletion (Supplemental Fig. 1C, 1D). Compound deficiency of T-bet and Eomes resulted in almost complete elimination of the type 1 ILC compartment in all tissues examined (Fig. 1B). Together with previous findings (1, 6, 7), the present results suggest that both T-bet and Eomes are required in order to develop the spectrum of lymphoid and non-lymphoid type 1 ILCs. Eomes, furthermore, seemingly plays its essential role in type 1 ILC maturation after the onset of NKp46 expression.

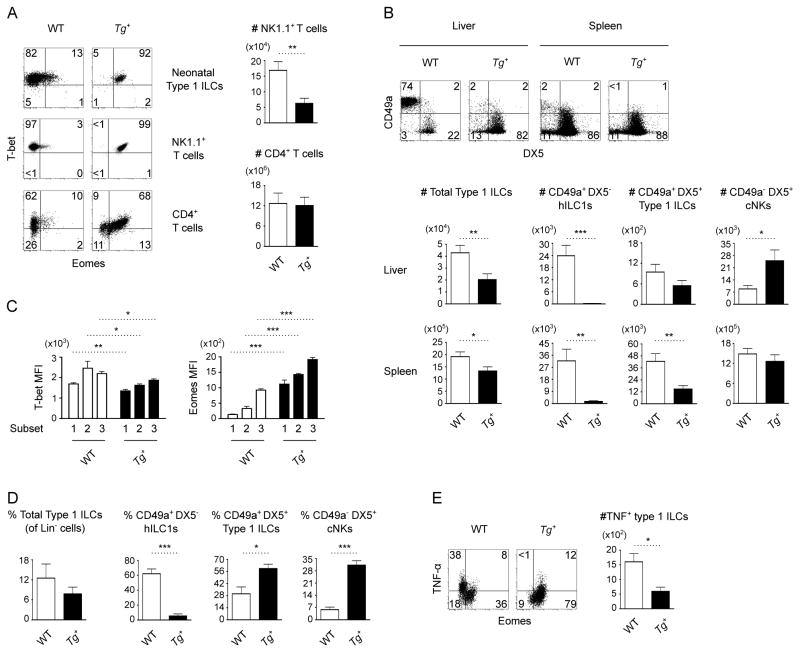

Eomes induces cNK properties among type 1 ILCs

Because loss of Eomes at the NKp46-expressing stage illustrates the necessity of Eomes for cNK development (Fig. 1A), we wished to test if Eomes expression at the onset of hILC1 lineage maturation would be sufficient to redirect hILC1s into a cNK identity. T-bet-dependent hILC1s lack endogenous Eomes expression (1, 2, 4, 6, 7). To enforce Eomes expression in developing hILC1s, we generated transgenic mice in which Tbx21 locus control elements drive expression of Eomes codons. Because T-bet is not expressed at substantial levels until type 1 ILCs acquire the lineage antigens NK1.1 and NKp46 (1, 15), we could determine the effect of transgenic Eomes expression following divergent lineage specification from NK1.1− NKp46− progenitors (6, 8).

We first verified that transgenic Eomes is expressed when and where T-bet is expressed by examining the pattern of Eomes expression in 3 cell populations that ordinarily express T-bet but not Eomes: neonatal type 1 ILCs, NK1.1+ T cells, and developing Th1 cells (1, 16). In each case, transgenic cells expressed Eomes in proportion to T-bet (Fig. 2A). Analyses of type 1 ILCs revealed that transgenic Eomes also perturbed the normal spatial and temporal pattern of hILC1 development. Transgenic Eomes caused a shift in frequency and absolute numbers toward CD49b (DX5) expression among NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues of adult mice (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Fig. 2A, 2Bxs). Examination of T-bet and Eomes levels revealed repressed T-bet expression in transgenic type 1 ILC subsets (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. 2C), suggesting that repression of T-bet by transgenic Eomes may at least partly explain the phenotypic shift. In addition to the shift in adult ILC subsets, transgenic neonates exhibited precocious development of DX5+ type 1 ILCs, compared to the minor population evident in WT neonates (Fig. 2D). Finally, Eomes− hILC1s have been suggested to express higher levels of TNF-α than Eomes+ cNKs (1, 6, 7). Consistent with the observed shift in integrin expression, we found that transgenic Eomes attenuated TNF-α expression by hepatic type 1 ILCs (Fig. 2E). Eomes expression, thus, appears sufficient to redirect hILC1s into a more cNK-like fate.

Figure 2. Eomes induces cNK attributes among type 1 ILCs.

(A) Transgenic (Tg+) Eomes expression in 3 cell populations (from at least 3 mice per genotype) that usually express T-bet but not Eomes: Lin− NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs from 3-day old neonatal livers; NK1.1+ CD3+ T cells from adult livers; and CD4+ T cells from adult spleens after αCD3- and αCD28-stimulation for 48 hours. Absolute numbers of NK1.1+ T cells and CD4+ T cells are indicated. Transgenic Eomes does not affect the development of CD4+ T cells, but it results in moderate reduction of the number of hepatic NK1.1+ T cells. (B) Flow cytometry of CD49a+ DX5−, CD49a+ DX5+, and CD49a− DX5+ type 1 ILC subsets from the livers and spleens of WT and Tg+ mice (n=5 mice per genotype). (C) T-bet and Eomes expression by hepatic CD49a+ DX5− (1), CD49a+ DX5+ (2), and CD49a− DX5+ (3) type 1 ILC subsets from WT and Tg+ mice (n=4 mice per genotype). (D) Frequency of total type 1 ILCs (among Lin− cells) and frequency of indicated subsets (among total type 1 ILCs) from the livers of WT and Tg+ neonates (n=4 mice per genotype). Transgenic Eomes does not affect the overall frequency of neonatal type 1 ILCs. (E) Flow cytometry of TNF-α expression by hepatic type 1 ILCs from WT and Tg+ mice (n=4 mice per genotype) after stimulation with 200 ng/mL PMA and 5 μg/mL Ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug (Invitrogen) for 4 hours. All data were obtained from mice that have 1 copy of the transgene (Tg+). Data are mean ± SEM representative of 2–5 independent analyses; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

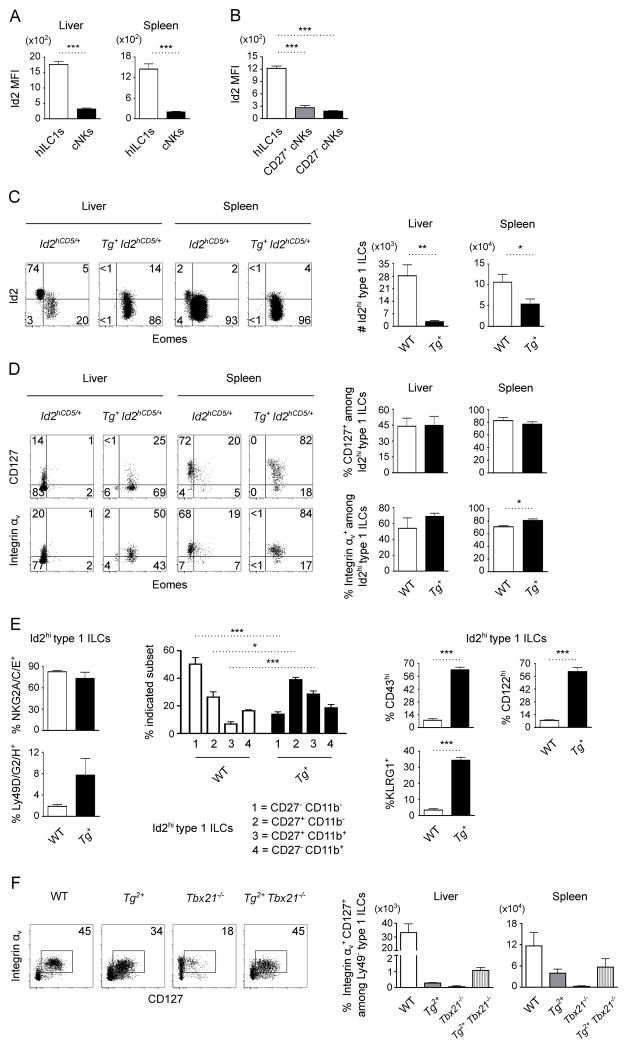

Eomes is permissive to some hILC1 attributes

Emerging evidence suggests that progenitor cells of all helper ILCs are distinct from progenitor cells of cNKs, and that helper ILC progenitors are marked by abundant expression of the transcription factor Id2 (6). We found that the descendant lineages of the distinct precursors, Eomes− hILC1s versus Eomes+ cNKs, continue to express high versus intermediate levels of Id2, respectively (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 2D). Eomes− hILC1s expressed higher levels of Id2 than Eomes+ cNKs regardless of their maturation (Fig. 3B). Examination of transgenic NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs revealed a subpopulation of Id2hi Eomes+ cells, suggesting the possibility that some cells arose from helper ILC precursors and were subsequently diverted into a cNK-like fate (Fig. 3C, Supplemental Fig. 2E). In support of the notion that the Id2hi subpopulation may have arisen from helper ILC precursors, we detected other characteristics of hILC1s (1, 6, 17), including expression of CD127, integrin αv (Fig. 3D and Supplemental Fig. 2F), NKG2A/C/E receptors, and a restricted Ly49 receptor repertoire (Fig. 3E and Supplemental Fig. 2G, 2H). The Id2hi subset of transgenic type 1 ILCs, nonetheless, also acquired numerous cNK features. Transgenic Eomes promoted upregulation of CD11b, CD43, KLRG1, and CD122 expression among Id2hi cells in the liver, and to a lesser degree in the spleen (Fig. 3E and Supplemental Fig. 2G, 2H). Despite increased maturity, Id2hi transgenic type 1 ILCs did not transition to the most terminal CD27− stages (18) of cNK maturation (Fig. 3E and Supplemental Fig. 2G, 2H). Together, these findings suggest that Eomes is sufficient to convert some but not all attributes of hILC1s to those of cNKs.

Figure 3. Eomes is permissive to some hILC1 attributes.

(A) Id2 expression by CD49a+ DX5− hILC1s and CD49a− DX5+ cNKs among Lin− NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs from the livers and spleens of Id2hCD5/+ mice (n=4 mice). (B) Id2 expression by CD49a+ Eomes− hILC1s, CD27+ Eomes+ immature cNKs, and CD27− Eomes+ mature cNKs from the spleens of Id2hCD5/+ mice (n=4 mice). (C) Flow cytometry of Id2 and Eomes expression by NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs from the livers and spleens of Id2hCD5/+ and Tg+ Id2hCD5/+ mice (n=5 mice per genotype). Absolute numbers of Id2hi cells are indicated. (D) Flow cytometry of CD127 and integrin αv expression by Id2hi NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs from the livers and spleens of Id2hCD5/+ and Tg+ Id2hCD5/+ mice (n=3–4 mice per genotype). (E) Frequency of NKG2A/C/E, Ly49D/G2/H, CD27, CD11b, CD43, KLRG1, and CD122 expression by Id2hi NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs from the livers of Id2hCD5/+ and Tg+ Id2hCD5/+ mice (n=4 mice per genotype). (F) Flow cytometry of helper-like (CD127+ integrin αv+) cells among Ly49− NK1.1+ NKp46+ type 1 ILCs from the spleens of WT, Tg2+, Tbx21−/−, and Tg2+ Tbx21−/− mice. Absolute numbers of hILC1-like cells in the livers and spleens of n=2 mice per genotype are summarized. (A-F) Data were obtained from mice that have 1 (Tg+) or 2 (Tg2+) copies of the transgene as indicated. Data are mean ± SEM representative of 2–5 independent experiments; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

To determine whether the hILC1-like characteristics in a subset of transgenic type 1 ILCs were T-bet-dependent, we examined transgenic mice with genetic deletion of both endogenous Tbx21 alleles. In the absence of an Id2 reporter allele, we used Ly49− NK1.1+ NKp46+ as surrogate markers for hILC1s. Transgenic Eomes was sufficient to partially rescue the development of cells with hILC1 features (expression of CD127 and integrin αv) in Tbx21−/− mice (Fig. 3F), indicating that the residual hILC1-like characteristics of the transgenic line are not likely to be T-bet-dependent. Therefore, the structural homology between the two transcription factors may enable Eomes to partially substitute for T-bet in hILC1 development. Similarly, T-bet may partially substitute for Eomes during cNK development insofar as Eomesflox/flox NKp46-Cre+ mice contain fewer cNK cells when intercrossed to T-bet-deficient mice (Fig. 1A, 1B).

Our findings suggest that type 1 ILCs with distinct lineage origins have the potential for substantial developmental plasticity. Our data is consistent with a model in which separate type 1 ILC lineages are specified from distinct precursors and the absence or presence of Eomes subsequently directs or switches, albeit incompletely, their determination as hILC1s or cNKs. In an analogous manner, CD4+ T cells can acquire cytotoxic T cell attributes and lose helper attributes when ThPOK expression decreases and Runx3 expression increases, yet they can still continue to express the CD4 marker (19, 20). Understanding the nature of the inter-relatedness and plasticity between type 1 ILC subsets will help harness their therapeutic potential in infection, inflammation, and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 AI061699 and R01 AI113365 (to S.L.R.) and Grant F30 AI113963 (to O.P.).

We thank Dr. Jeff Zhu for advice in designing the transgene and Dr. Victor Lin of the Transgenic Mouse Shared Resource for micro-injection and production of the transgenic line.

Abbreviations used in this article

- Eomes

Eomesodermin

- Type 1 ILCs

type 1 innate lymphocytes

- hILC1s

type 1 helper innate lymphoid cells

- cNKs

conventional NK cells

- WT

wild-type

- cKO

conditional knockout

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gordon SM, Chaix J, Rupp LJ, Wu J, Madera S, Sun JC, Lindsten T, Reiner SL. The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daussy C, Faure F, Mayol K, Viel S, Gasteiger G, Charrier E, Bienvenu J, Henry T, Debien E, Hasan UA, Marvel J, Yoh K, Takahashi S, Prinz I, de Bernard S, Buffat L, Walzer T. T-bet and Eomes instruct the development of two distinct natural killer cell lineages in the liver and in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2014;211:563–577. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs A, Vermi W, Lee JS, Lonardi S, Gilfillan S, Newberry RD, Cella M, Colonna M. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-gamma-producing cells. Immunity. 2013;38:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng H, Jiang X, Chen Y, Sojka DK, Wei H, Gao X, Sun R, Yokoyama WM, Tian Z. Liver-resident NK cells confer adaptive immunity in skin-contact inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1444–1456. doi: 10.1172/JCI66381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortez VS, Fuchs A, Cella M, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. Cutting edge: Salivary gland NK cells develop independently of Nfil3 in steady-state. J Immunol. 2014;192:4487–4491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klose CS, Flach M, Mohle L, Rogell L, Hoyler T, Ebert K, Fabiunke C, Pfeifer D, Sexl V, Fonseca-Pereira D, Domingues RG, Veiga-Fernandes H, Arnold SJ, Busslinger M, Dunay IR, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sojka DK, Plougastel-Douglas B, Yang L, Pak-Wittel MA, Artyomov MN, Ivanova Y, Zhong C, Chase JM, Rothman PB, Yu J, Riley JK, Zhu J, Tian Z, Yokoyama WM. Tissue-resident natural killer (NK) cells are cell lineages distinct from thymic and conventional splenic NK cells. eLife. 2014;3:e01659. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinette ML, Fuchs A, Cortez VS, Lee JS, Wang Y, Durum SK, Gilfillan S, Colonna M C. the Immunological Genome, and C. the Immunological Genome. Transcriptional programs define molecular characteristics of innate lymphoid cell classes and subsets. Nat Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ni.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, Mullen AC, Gasink CR, Kaech SM, Miller JD, Gapin L, Ryan K, Russ AP, Lindsten T, Orange JS, Goldrath AW, Ahmed R, Reiner SL. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Intlekofer AM, Banerjee A, Takemoto N, Gordon SM, Dejong CS, Shin H, Hunter CA, Wherry EJ, Lindsten T, Reiner SL. Anomalous type 17 response to viral infection by CD8+ T cells lacking T-bet and eomesodermin. Science. 2008;321:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1159806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narni-Mancinelli E, Chaix J, Fenis A, Kerdiles YM, Yessaad N, Reynders A, Gregoire C, Luche H, Ugolini S, Tomasello E, Walzer T, Vivier E. Fate mapping analysis of lymphoid cells expressing the NKp46 cell surface receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18324–18329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112064108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones-Mason ME, Zhao X, Kappes D, Lasorella A, Iavarone A, Zhuang Y. E protein transcription factors are required for the development of CD4(+) lineage T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teo AK, Arnold SJ, Trotter MW, Brown S, Ang LT, Chng Z, Robertson EJ, Dunn NR, Vallier L. Pluripotency factors regulate definitive endoderm specification through eomesodermin. Genes Dev. 2011;25:238–250. doi: 10.1101/gad.607311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsend MJ, Weinmann AS, Matsuda JL, Salomon R, Farnham PJ, Biron CA, Gapin L, Glimcher LH. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477–494. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazarevic V, Glimcher LH, Lord GM. T-bet: a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13:777–789. doi: 10.1038/nri3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda K, Cretney E, Hayakawa Y, Ota T, Akiba H, Ogasawara K, Yagita H, Kinoshita K, Okumura K, Smyth MJ. TRAIL identifies immature natural killer cells in newborn mice and adult mouse liver. Blood. 2005;105:2082–2089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiossone L, Chaix J, Fuseri N, Roth C, Vivier E, Walzer T. Maturation of mouse NK cells is a 4-stage developmental program. Blood. 2009;113:5488–5496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-187179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mucida D, Husain MM, Muroi S, van Wijk F, Shinnakasu R, Naoe Y, Reis BS, Huang Y, Lambolez F, Docherty M, Attinger A, Shui JW, Kim G, Lena CJ, Sakaguchi S, Miyamoto C, Wang P, Atarashi K, Park Y, Nakayama T, Honda K, Ellmeier W, Kronenberg M, Taniuchi I, Cheroutre H. Transcriptional reprogramming of mature CD4(+) helper T cells generates distinct MHC class II-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:281–289. doi: 10.1038/ni.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis BS, Rogoz A, Costa-Pinto FA, Taniuchi I, Mucida D. Mutual expression of the transcription factors Runx3 and ThPOK regulates intestinal CD4(+) T cell immunity. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:271–280. doi: 10.1038/ni.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.