Abstract

Lipid droplets (LDs) in steroidogenic tissues have a cholesteryl ester (CE) core surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer that is coated with associated proteins. Compared with other tissues, they tend to be smaller in size and more numerous in numbers. These LDs are enriched with PLIN1c, PLIN2 and PLIN3. Both CIDE A and B are found in mouse ovary. Free cholesterol (FC) released upon hormone stimulation from LDs is the preferred source of cholesterol substrate for steroidogenesis, and HSL is the major neutral cholesterol esterase mediating the conversion of CEs to FC. Through the interaction of HSL with vimentin and StAR, FC is translocated to mitochondria for steroid hormone production. Proteomic analyses of LDs isolated from loaded primary ovarian granulosa cells, mouse MLTC-1 Leydig tumor cells and mouse testes revealed LD associated proteins that are actively involved in modulating lipid homeostasis along with a number of steroidogenic enzymes. Microscopy analysis confirmed the localization of many of these proteins to LDs. These studies broaden the role of LDs to include being a platform for functional steroidogenic enzyme activity or as a port for transferring steroidogenic enzymes and/or steroid intermediates, in addition to being a storage depot for CEs.

Keywords: lipid droplet proteins, PLIN, adrenal gland, gonads, steroid synthesizing enzymes, steroidogenesis, cholesteryl esters

Introduction

Intracellular lipid droplets (LDs) are dynamic organelles that are composed of a neutral lipid core, a surface phospholipid monolayer and proteins that are embedded in or bound to the phospholipid layer. They are found in nearly all types of eukaryotic cells and are involved in multiple intracellular processes, such as membrane trafficking, lipid metabolism and cell signaling (1). Depending on the tissue in which the LD accumulates and the metabolic function of the tissue, the size and the lipid content of the LDs are different. Mature adipocytes contain LDs that can be >50 µm in size and occupy the entire cell volume and function as a long-term energy storage depot (2). The LDs in other cell types are usually much smaller than those in adipocytes and they are thought to be involved in the temporal storage and effective utilization of lipids. Although both triacylglycerol (TAG) and cholesteryl esters (CE) accumulate in LDs, they seem to form distinct LD particles in some cells; the compositions of LDs can vary greatly in different tissues. While the intracellular LDs in adipocytes, liver, and muscle cells consist primarily of TAG and diacylglycerol (DAG), the LDs in steroidogenic cells, such as ovarian granulosa and adrenocortical cells, as well as testicular Leydig cells, primarily accumulate CE (3–5). Over the past decade, the employment of genetic and proteomic approaches have allowed the identification of many proteins on the LD surface and have provided clues to their function in cellular and LD physiology (6–10). Here we aim at providing a review of the findings related to LD function in steroidogenic cells.

General properties of LDs in steroidogenic tissues

Steroid hormones are synthesized de novo from cholesterol in mitochondria and the ER, and are secreted from specialized endocrine cells in the adrenal cortex, testes and ovaries. Unlike cells that produce polypeptide hormones, which can store large amounts of mature hormones for rapid release, there is very little steroid hormone storage in steroidogenic cells. Therefore, upon stimulation, there is a rapid response in steroidogenic cells to synthesize new steroids (11, 12), a process that requires a constant supply of cholesterol as a precursor for conversion to steroids. Within steroidogenic tissue, cholesterol is stored in LDs in the form of cholesterol esters (CEs), and the mobilization of these stored CEs is the preferred source of cholesterol for steroidogenesis upon hormone stimulation. There are generally numerous quantities of cytosolic CE-enriched LDs in steroidogenic cells, which usually are small with a diameter of 0.5–1.5 µm (13). When loaded with fatty acids, steroidogenic cells can also form LDs composed of TAG. In a study using specific fatty acid and cholesterol fluorescent probes in mouse Y1 adrenocortical tumor cells, Hsieh et al. (14) observed relatively limited mixing of lipid species in LDs when loaded simultaneously with fatty acids and cholesterol and noticed a distinctive separation of TAG-rich and CE-rich LDs in discrete LDs.

LD associated proteins in steroidogenic tissues

Since the initial identification of perilipin (now named PLIN1), which coats the surface of LDs, numerous proteins have been shown, based on genetic as well as proteomic analyses, to associate with LDs. Moreover, the protein composition of LDs changes under different physiological conditions.

PLIN, CIDE and lipase protein families

Two particular families of proteins intimately associated with LDs are the PLIN and CIDE protein families.

PLIN1 was the first protein identified to be associated with LDs (15). The family has since expanded to include not only perilipin (PLIN1), but also PLIN2 (ADRP), PLIN3 (TIP47), PLIN4 (S3-14) and PLIN5 (OXPAT/LSDP5) (16–19). PLIN family members display different tissue distributions and different preferences to associate with TAG-enriched or CE-enriched LDs (14). A single Peri gene encodes 4 different alternatively spliced variants of PLIN1 a-d; PLIN1a and PLIN1b are expressed both in adipose and steroidogenic tissues, while PLIN1c and PLIN1d are limited to steroidogenic tissues (20). In white adipocytes, PLIN1 is highly expressed and active, modulating LD enlargement as well as LD lipolysis through interactions with FSP27, HSL and CGI-58 (21–24). PLIN2 is suggested to interact with LDs within the monolayer or at the monolayer surface and may play a role in increasing LD membrane size during LD expansion (25, 26). Down-regulation of PLIN2 was shown to decrease lipid accumulation in liver and attenuate the growth of tumor cells (27, 28). In contrast, higher levels of PLIN2 have been suggested to be protective against lipotoxicity and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle (29). Most recently, a missense polymorphism of PLIN2, Ser251Pro, was shown to promote cellular lipid accumulation, increase the number of small LDs, decrease lipolysis, and decrease plasma triglyceride concentrations. This is the first functional variant of PLIN2 that is associated with plasma VLDL and triglyceride levels (30). PLIN3 is widely expressed in hepatocytes, enterocytes, and macrophages, as well as in testicular cells (14), and has unique dual functions: involvement in mannose 6-phosphate receptor recycling and in lipid biogenesis (31). The newest member of the family, PLIN5, was shown to be involved in regulation of fatty acid oxidation in various tissues including adipose, heart, liver and muscle (32).

PLIN1c, PLIN2, as well as PLIN3, have all been shown to be present in steroidogenic tissues, and expression of PLIN1c and PLIN4 was shown to be enhanced by cellular cholesterol loading (14). In a recent study from our group, PLIN2 was shown to be the predominant PLIN in granulosa cells (adipose differentiation-related protein, ADRP) (10), which confirms a previous finding of ADRP in primate granulosa cells (33).

CIDE (cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector) protein family (CIDEA, CIDEB and CIDEC, also known as FSP27) has been shown to reside on LDs and to be found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). CIDE-A was identified as a regulator of energy homeostasis and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue (34), whereas CIDE-B controls lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation in the liver (35). CIDE C (FSP27) was shown to interact with PLIN1 through its CIDE-N domain, leading to increased lipid transfer activity (22). Meanwhile, we have shown that FSP27 interacts with nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 (NFAT5) at the LD surface and modulates the cellular response to osmotic stress by preventing NFAT5 from translocating to the nucleus and activating its down-stream targets (36). Both CIDE A and CIDE B have been shown to be expressed in mouse ovary (37).

It is worth noting that while PLIN1, PLIN2, CIDE A and CIDE B have all been detected in the mouse ovary, the expression of PLIN2 was distinct from that of the other three LD proteins. PLIN2 was co-localized with LDs in oocytes (37).

For the lipid content of LDs to be utilized, lipases need to act upon the stored TAG, CE or various retinyl esters to release FA and glycerol from TAG, FA and cholesterol from CE, and FA and retinol from retinyl esters. Proteomic analyses have shown that the lipases and lipase activators, which are responsible for the catabolism of stored LDs to be utilized, reside on LDs in steroidogenic tissue and include: ATGL, HSL, CGI-58, Tgh/Ces3, MglI, Ldah, LMf2 (38). ATGL hydrolyzes TAG and is the primary enzyme responsible for the breakdown of TAG to DAG (39). HSL can hydrolyze DAG and CE, as well as retinyl esters (40). CGI-58 does not have lipase activity by itself, and upon hormone stimulation acts as an activator of ATGL hydrolytic activity. Most recently, ATGL and CGI-58 were reported to possibly be involved in the mobilization of retinoids in hepatic stellate cells (41, 42). MglI only hydrolyzes monoacylglycerol (43). Tgh/Ces3 can hydrolyze TAG and DAG and is involved in VLDL assembly and LD maturation (44).

Other LD proteins in steroidogenic tissue

Recently, in order to better understand the proteins found on CE-enriched LDs in steroidogenic cells, we compared the LD proteins isolated from CE-enriched LDs to proteins found on TAG-enriched LDs in steroidogenic cells using tandem mass tags (TMT) for protein identification and quantification (10). For these studies, isolated primary rat granulosa cells were loaded with either HDL to produce CE-enriched LDs or fatty acids to produce TAG-enriched LDs. Sixty-one proteins were found to be preferentially associated with CE-enriched LDs and 40 proteins preferentially found in TAG-enriched LDs, with 278 proteins observed in similar amounts in the two types of LDs. Most of these proteins have been previously identified to associate with LDs in proteomics studies of TAG-enriched LDs isolated from a variety of cell types, including adipose, liver, CHO cells, etc (6–10). Protein expression was further validated by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) mass spectrometry (MS) (45). SRM verified expression of 24 of 27 peptides that were previously detected by tandem mass tagging MS. Among those are Hsd3b1, Plin 2, Rab 8A, Scarb1, Slc27a1, Vdac1 and 2, vimentin.

It is likely that the presence of some of the unique proteins identified in CEenriched LDs is due to the lipid composition of the LDs. Of the proteins preferentially associated with CE-enriched LDs by our shotgun proteomic analysis, 34 proteins were seen in a study using photoreactive sterol probes in combination with quantitative mass spectrometry to map cholesterol-protein interactions (31). These proteins include Vdac 1 and 2, 17-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, Vapa, Scarb1, and solute carrier family 27 (Slc27). Some of the proteins that were detected on the CE-enriched LDs were not found on the list of direct cholesterol-protein interactions. Thus, those proteins might not directly bind to cholesterol moieties, perhaps instead interacting with proteins surrounding the LDs or interacting with the phospholipid monolayer surrounding the LD.

Of the detected proteins, Vdac1 and 2 are particularly notable, due to recent findings of their involvement in lipid transfer within the mitochondria. VDACs are the most abundant mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) proteins and serve as a large channel that functions in the pathway for mitochondrial respiration, allowing substrates to cross the MOM, thus functioning as global regulators of mitochondrial function (46, 47). Interestingly, Vdac1 was found to interact with steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein to facilitate the transfer of cholesterol into the inner mitochondrial membrane (26) for steroidogenesis. Although there is the possibility of mitochondrial protein contamination due to the close apposition of mitochondria and LDs following hormonal stimulation, our findings that Vdac appears to be present at higher levels on CE-enriched LDs compared to TAG-enriched LDs may signify a role for VDAC in binding CE-enriched LDs or facilitation of CE movement into the mitochondria. In a similar fashion, vimentin, an intermediate filament that has been found to be associated with LDs (7, 48, 49) and involved in steroidogenesis (50), was increased in CE-enriched LDs. Ablation of vimentin in mice decreases movement of cholesterol to the mitochondria in adrenals and ovaries, resulting in decreased corticosterone and progesterone production (51).

Other proteomics studies of LDs isolated from steroidogenic tissues and cells are very limited, but two other groups have recently and almost simultaneously reported proteomic studies of LDs from testicular steroidogenic tissue, one from murine testes and one from mouse MLTC-1 Leydig tumor cells. Isolating LDs from testes of 10 week old C57BL/6 mice, Wang et al. (38) performed proteomic analysis using a 2D-HPLC system coupled to a linear ion-trap mass spectrometer followed by immunodetection of the proteins identified. Among the 337 proteins they identified, 144 were previously reported to be associated with LDs, and 44 were confirmed by microscopy. They identified multiple Rab GTPases, members of the PLIN family and classic lipase/esterase superfamily, chaperones, and proteins involved in glucuronidation, ubiquination and transport. The presence of PLIN1a-d, PLIN2-4, lipases such as ATGL, HSL and CGI58, Cav1 and 3, and HSD3b1 was further confirmed by Western blotting.

At the same time, Yamaguchi et al. (13) reported the characterization of LDs isolated from MLTC-1 cells. Comparing proteins isolated from LDs from J774 macrophages and Hepa-1 hepatoma cell lines, the protein profile from LD proteins isolated from MLTC-1 cells showed a distinct pattern, and LC-MS/MS analysis using Q-TOF micro mass spectrometer identified eighty proteins, including HSD3b1 and HSD17b11, which they later showed to localize to both LDs and ER. Consistent with the other two reports discussed above, among the eighty proteins identified were PLIN family members, lipase superfamily proteins, Rab proteins, and chaperones, as well as proteins involved in intracellular transport. Among the proteins prominently identified in all three reports are enzymes involved in steroidogenesis. Table 1 summarizes the major categories of proteins found to be associated with lipid droplets isolated from steroidogenic cells, selected examples within each of the categories, along with relevant references.

Table 1.

Lipid Droplet Associated Proteins in Steroidogenic Tissues

| Pathway | Proteins | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol-interacting Proteins | ||

| HSD17b1 | (31) | |

| Vdac 1, Vdac2, VaPa | ||

| Rab8A, Scarb1, Slc 27 | ||

| Lipid Synthesis Enzymes | ||

| GPAT4, AGPAT3, and DGAT2 | (52) | |

| Lipid Droplet Expansion | ||

| FSP27, PLIN1, PLIN5, SNAP23, γ-synuclein | (68) | |

| Atg2 | (69) | |

| Aup1 | (54, 57) | |

| Rdh10 | (67) | |

| PLIN, CIDE and Esterase/Lipases | ||

| PLIN1a-d, 2, 3, 4 | (38) | |

| CIDE A, B | ||

| ATGL, HSL, CGI-58, Tgh/Ces3 | (37) | |

| MglI, Ldah, LMf2 | ||

| Proteins that interact with other Organelles | Aup1 | (57) |

| PLIN5 | (61) | |

| Rdh10 | (62) | |

| Ubx2, Ubxd8 | (58–59) | |

| Steroidogenic Enzymes | ||

| ALDH1a1, ABCd3 | (10, 13, 38) | |

| CYP11a1, CYP17a1 | ||

| Dhrs 1, 3 and X | ||

| Hsd3b1 and 7, Hsd17b4, Hsd17b7 and 11, Hsd12 | ||

| LSS, NSDH1, mEH, Rdh 10 and 14 | ||

| Scarb1 | ||

| Transport Proteins | ||

| Vdac 1, 2 | ||

| Rab GTPases | ||

| SNAP23 | (70) | |

LD interaction with other cellular organelles

Many studies using electron microscopy and fluorescent imaging techniques have shown that LDs actively interact with other organelles, such as the ER and mitochondria (52–55). It is believed that LDs form in the ER and the interaction between ER resident proteins, such as FATP1, and LD proteins, such as DGAT2, facilitates LD expansion. However, there is also evidence that several of the enzymes required for latter stages of neutral lipid synthesis are found on the LD surface and can mediate LD expansion (56). Members of the small GTPase family, Rab proteins, have been suggested to function in LD trafficking within the ER and LD formation, and Rab32 can also affect lipid storage through its effects on autophagy (53).

Recent studies have also revealed unique mechanisms in regulating neutral lipid storage involving ER-associated degradation (ERAD). For mediating cholesterol homeostasis, Aup1, which has a single domain that allows for its insertion into the ER as well as into LDs (57), was shown to interact with ERAD and facilitate binding of gp78 and Trc8 to ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Ubc7) at the LD surface (54). UBX-domain containing protein (Ubx2), which is an ER protein and selectively transports misfolded proteins for ERAD, was shown to be crucial in LD maintenance, with its deletion leading to a 50% decrease in intracellular TAG accumulation (58). Similarly, Ubxd8 was found to bind to ATGL, thus contributing to LD turnover and maintaining LD size, as well as providing an important mechanism for regulating energy balance (59).

In the recent study of LD proteins in the steroidogenic Leydig MLTC-1 cell line (13), PLIN1 immunostaining signal was seen in perinuclear LDs; whereas upon hormone stimulation of steroidogenesis, PLIN1 signal was seen on small LDs throughout the cytoplasmic space and overlapped with calnexin. These observations suggest that the perinuclear LDs in steroidogenic tissue undergo remodeling to small LDs with hormone stimulation, and these small LDs are closely associated with the ER.

In addition to the ER, LDs are known to interact with mitochondria for FA metabolism or steroidogenesis. Recent studies show that PLIN5 is highly expressed in muscle tissue, being expressed on both LDs and mitochondria, and involved in directing FA transfer from LDs to mitochondria for FA oxidation (55). Exercise was found to increase transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α, leading to an increase in genes involved in LD assembly and mobilization and mitochondrial remodeling, including PLIN5 (60, 61). Retinyl esters, the storage form of retinal, accumulate within LDs and have been observed to utilize a complex between the ER, LDs, and mitochondria for synthesis and metabolism. Retinol dehydrogenase Rdh10 is localized to mitochondria and the mitochondria associated membrane (MAM) of the ER, but translocates to LDs during retinyl acyl ester biosynthesis, colocalizing with cellular retinol-binding protein (Crbp1) and lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (Lrat1), an ER protein (62). Activation of hepatic stellate cells into myofibroblasts leads to a replacement of retinyl esters by polyunsaturated FAs in LDs, suggesting a dynamic and regulated process at the LD (63).

LD metabolism and Steroidogenesis

Since steroidogenic cells do not store significant quantities of steroidogenic hormones, there is a need to synthesize new steroids upon stimulation, a process that requires a constant supply of cholesterol as a precursor for conversion to steroid hormones. The cholesterol utilized for steroidogenesis can be derived from a combination of sources: 1) de novo cellular cholesterol synthesis in the ER, 2) the mobilization of CEs stored in LDs, and 3) lipoprotein-derived CEs obtained by either LDL receptor-mediated endocytic uptake or “selective” cellular uptake via the scavenger receptor, class B type I (SR-BI). For the initiation of steroid production in the adrenal and ovary, but apparently not the normal testis, the mobilization of cholesterol from LDs and its transport to mitochondria is a preferred pathway.

Hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) has been shown to be the major neutral cholesteryl ester hydrolase in steroidogenic tissue (64). In HSL−/− mice, the neutral CEH activity in adrenal was reduced more than 98% compared with controls. Female HSL−/− mice showed a reduction in stimulated corticosterone values (65). In our study of cholesterol movement to mitochondria for steroidogenesis, we have shown that HSL interacts with vimentin, as well as with StAR, for the transfer of lipolytic product, e.g., cholesterol, to the mitochondria for steroid hormone synthesis (66, 67). In vimentin−/− mice there is an over accumulation of CE in the adrenal, and there are significant defects in adrenal and ovarian steroidogenesis. Although there are no abnormalities in human chorionic gonadotropin-stimulated testosterone production observed in male vimentin−/− mice, progesterone production is decreased 70% in female vimentin−/− mice after pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin and human chorionic gonadotropin stimulation. At the same time, cosyntropin-stimulated corticosterone production is decreased 35 and 50 % in male and female vimentin−/− mice, respectively. Further studies show a defect in the movement of cholesterol from the cytosol to mitochondria in vimentin−/− cells.

In our recent studies of the LD proteome of primary granulosa cells, several steroidogenic enzymes were detected in our analysis, including 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/δ5-4 isomerase type 1 and 2 (Hsd3b1 and Hsd3b2), which were elevated in CE-enriched LDs compared to TAG-enriched LDs, suggesting that these enzymes might act directly upon the LDs for steroid production (10). This observation is echoed by two other independent proteomic studies in the male steroidogenic system, one using MLTC-1 Leydig cell LDs and one using murine testes LDs (13, 38).

In addition to Hsd3b1 and Hsd17b11, the LD fraction from MLTC-1 cells also included Cyp11A1 (cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme) and Cyp17, enzymes involved in the production of testosterone, which is the major product of Leydig cells (13). Furthermore, treatment of MLTC-1 cells with luteinizing hormone or 8-bromo-cAMP, which can stimulate steroidogenesis in Leydig cells, caused the fragmentation of perinuclear LDs and resulted in much smaller LDs that are dispersed throughout the cytosol. In the proteomic analysis of murine testes LDs, which are also CE-enriched, Wang et al. showed that testicular LDs contained nineteen of the enzymes classically involved in cholesterol metabolism and steroid synthesis, including LSS, NSDH1, CYP17a1, Hsd3b1 and 7, Hsd17b4, Hsd17b7 and 11, Hsd12, Rdh 10 and 14, Aldh1a1, Dhrs 1,3 and X, mEH, Abcd3, as well as Scarb1(13).

In view that classically many of these enzymes are found either in ER or mitochondria, there is the possibility of contamination of the isolated LDs with other organelles due to their close association with LDs; however, localization studies of some of these proteins suggest that they truly do associate with LDs. These studies further suggest that LDs in steroidogenic tissue are actively involved in the regulation of steroidogenesis, that they function not merely by serving as storage depots for cholesterol esters, but could also function by either providing a platform for active enzymes for steroidogenesis or as a port for transferring steroidogenic enzymes and/or steroid intermediates.

Conclusion

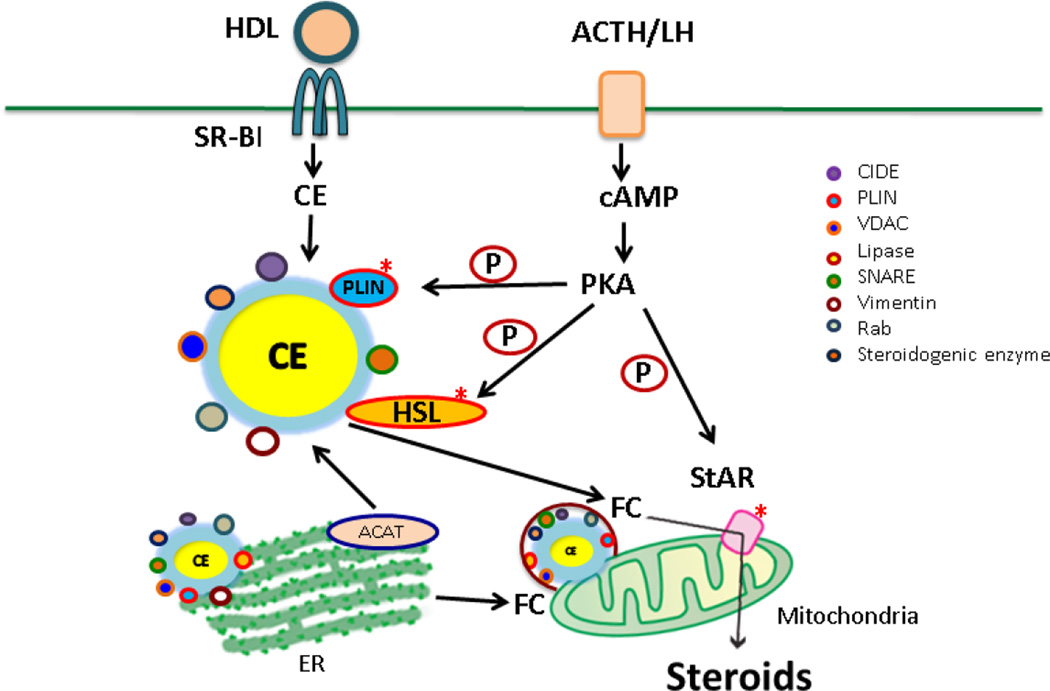

LDs in steroidogenic tissue are CE enriched, smaller in size, present in greater numbers compared with other tissues, and are coated with unique proteins (Figure 1). Upon hormone stimulation there is a rapid response of LDs to release FC as substrate for steroid hormone synthesis. LDs from steroidogenic tissue are actively involved in regulation of lipid homeostasis and steroidogenesis through their interaction with mitochondria and ER.

Figure 1. Lipid droplets in steroidogenic tissues.

LDs in steroidogenic tissues are CE enriched, about 0.5–1.5 µm in diameter, and are coated with many proteins including PLINs, CIDEs, lipases, SNAREs, vimentin, Rabs, VDACs, and some steroidogenic enzymes. Upon hormone stimulation, HSL acts on CEs in LDs to release FC. Through HSL-vimentin and HSL-StAR interactions, FC traffics to mitochondria for steroid hormone production. LDs interact with mitochondria and ER. Recent findings suggest that LDs could function either as a platform for functional steroidogenic enzyme activity or as a port for transferring steroidogenic enzymes and/or steroid intermediates, in addition to being a storage depot for CEs

Highlights.

In steroidogenic tissue:

LDs are CE enriched, about 0.5–1.5 µm in diameter, and are coated with many proteins including PLINs, CIDEs, lipases, SNAREs, vimentin, Rabs, VDACs, and some steroidogenic enzymes.

Upon hormone stimulation, HSL acts on CEs in LDs to release FC. Through HSL-vimentin and HSL-StAR interactions, FC traffics to mitochondria for steroid hormone production.

LDs interact with mitochondria and ER. Recent findings suggest that LDs could function either as a platform for functional steroidogenic enzyme activity or as a port for transferring steroidogenic enzymes and/or steroid intermediates, in addition to being a storage depot for CEs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service (SA, FBK) and by grant 2R01HL33881 (SA) from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CE

cholesteryl ester

- CIDE

cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

ER-associated degradation

- FC

free cholesterol

- HSL

hormone sensitive lipase

- LD

lipid droplet

- MOM

mitochondrial outer membrane

- SNARE

soluble NSF attachment protein receptor

- StAR

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- SRM

selected reaction monitoring

- TMT

tandem mass tags

- VDAC

voltage-dependent anion-selective channel

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Lipid droplets finally get a little R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Cell. 2009;139(5):855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy DJ. The biogenesis and functions of lipid bodies in animals, plants and microorganisms. Prog Lipid Res. 2001;40(5):325–438. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato S, et al. Proteomic profiling of lipid droplet proteins in hepatoma cell lines expressing hepatitis C virus core protein. J Biochem. 2006;139(5):921–930. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestler JETK, Strauss JF., III . Lipoprotein and cholesterol metabolism in cell sthat synthesize steroid hormones. In: Esfahani M, Swaney J, editors. Advances in Cholesterol Research. The Telford Press; 1990. pp. 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plump AS, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I is required for cholesteryl ester accumulation in steroidogenic cells and for normal adrenal steroid production. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(11):2660–2671. doi: 10.1172/JCI118716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Londos C, et al. On the control of lipolysis in adipocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brasaemle DL, Dolios G, Shapiro L, Wang R. Proteomic analysis of proteins associated with lipid droplets of basal and lipolytically stimulated 3T3- L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46835–46842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu P, et al. Chinese hamster ovary K2 cell lipid droplets appear to be metabolic organelles involved in membrane traffic. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(5):3787–3792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krahmer N, et al. Protein correlation profiles identify lipid droplet proteins with high confidence. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(5):1115–1126. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.020230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khor VK, et al. The proteome of cholesteryl-ester-enriched versus triacylglycerol-enriched lipid droplets. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garren LD, Ney RL, Davis WW. Studies on the role of protein synthesis in the regulation of corticosterone production by adrenocorticotropic hormone in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965;53(6):1443–1450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.53.6.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis W, Garren L. On the mechanism of action of adrenocorticotropic hormone: the inhibitory site of cycloheximide in the pathway of steroid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:5153–5157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamaguchi T, et al. Characterization of lipid droplets in steroidogenic MLTC-1 Leydig cells: Protein profiles and the morphological change induced by hormone stimulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851(10):1285–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh K, et al. Perilipin family members preferentially sequester to either triacylglycerol-specific or cholesteryl-ester-specific intracellular lipid storage droplets. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 17):4067–4076. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg AS, et al. Perilipin, a major hormonally regulated adipocytespecific phosphoprotein associated with the periphery of lipid storage droplets. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(17):11341–11346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang HP, Serrero G. Isolation and characterization of a full-length cDNA coding for an adipose differentiation-related protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(17):7856–7860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz E, Pfeffer SR. TIP47: a cargo selection device for mannose 6- phosphate receptor trafficking. Cell. 1998;93(3):433–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherer PE, Bickel PE, Kotler M, Lodish HF. Cloning of cell-specific secreted and surface proteins by subtractive antibody screening. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16(6):581–586. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalen KT, et al. LSDP5 is a PAT protein specifically expressed in fatty acid oxidizing tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771(2):210–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu X, et al. The murine perilipin gene: the lipid droplet-associated perilipins derive from tissue-specific, mRNA splice variants and define a gene family of ancient origin. Mamm Genome. 2001;12(9):741–749. doi: 10.1007/s00335-01-2055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg AS, et al. Stimulation of lipolysis and hormone-sensitive lipase via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):45456–45461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grahn TH, et al. FSP27 and PLIN1 interaction promotes the formation of large lipid droplets in human adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432(2):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi F, et al. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410(6832):1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bronner M, Hertz R, Bar-Tana J. Kinase-independent transcriptional co-activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha by AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem J. 2004;384(Pt 2):295–305. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee WJ, et al. AMPK activation increases fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle by activating PPARalpha and PGC-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340(1):291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose M, Whittal RM, Miller WL, Bose HS. Steroidogenic activity of StAR requires contact with mitochondrial VDAC1 and phosphate carrier protein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(14):8837–8845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stocco DM. StAR protein and the regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer FB. Adrenal cholesterol utilization. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;265–266:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jagerstrom S, et al. Lipid droplets interact with mitochondria using SNAP23. Cell Biol Intern. 2009;33(9):934–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magne J, et al. The minor allele of the missense polymorphism Ser251Pro in perilipin 2 (PLIN2) disrupts an alpha-helix, affects lipolysis, and is associated with reduced plasma triglyceride concentration in humans. FASEB J. 2013;27(8):3090–3099. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-228759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hulce JJ, Cognetta AB, Niphakis MJ, Tully SE, Cravatt BF. Proteomewide mapping of cholesterol-interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10(3):259–264. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picotti P, Bodenmiller B, Mueller LN, Domon B, Aebersold R. Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell. 2009;138(4):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seachord CL, VandeVoort CA, Duffy DM. Adipose differentiation-related protein: a gonadotropin- and prostaglandin-regulated protein in primate periovulatory follicles. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(6):1305–1314. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Z, et al. Cidea-deficient mice have lean phenotype and are resistant to obesity. Nat Genet. 2003;35(1):49–56. doi: 10.1038/ng1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li JZ, et al. Cideb regulates diet-induced obesity, liver steatosis, and insulin sensitivity by controlling lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. Diabetes. 2007;56(10):2523–2532. doi: 10.2337/db07-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueno M, et al. Fat-specific protein 27 modulates nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 and the cellular response to stress. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(3):734–743. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M033365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, et al. Identification of perilipin-2 as a lipid droplet protein regulated in oocytes during maturation. Reprod Fer Devel. 2010;22(8):1262–1271. doi: 10.1071/RD10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W, et al. Proteomic analysis of murine testes lipid droplets. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12070. doi: 10.1038/srep12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann R, et al. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306(5700):1383–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1100747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kraemer F, Shen W. Hormone-sensitive lipase: control of intracellular tri-(di)acylglycerol and cholesteryl ester hydrolysis. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:1585–1594. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200009-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eichmann TO, et al. ATGL and CGI-58 are lipid droplet proteins of the hepatic stellate cell line HSC-T6. J Lipid Res. 2015;56(10):1972–1984. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M062372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taschler U, et al. Adipose triglyceride lipase is involved in the mobilization of triglyceride and retinoid stores of hepatic stellate cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851(7):937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scalvini L, Piomelli D, Mor M. Monoglyceride lipase: Structure and inhibitors. Chem Phys Lipids. 2015 Jul 26; doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2015.07.011. pii: S0009-3084(15)30016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei E, et al. Loss of TGH/Ces3 in mice decreases blood lipids, improves glucose tolerance, and increases energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2010;11(3):183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bostrom P, et al. SNARE proteins mediate fusion between cytosolic lipid droplets and are implicated in insulin sensitivity. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(11):1286–1293. doi: 10.1038/ncb1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. VDAC regulation: role of cytosolic proteins and mitochondrial lipids. J Bioenerg Biomemb. 2008;40(3):163–170. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoshan-Barmatz V, et al. VDAC, a multi-functional mitochondrial protein regulating cell life and death. Mol Aspects Med. 2010;31(3):227–285. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu CC, Howell KE, Neville MC, Yates JR, 3rd, McManaman JL. Proteomics reveal a link between the endoplasmic reticulum and lipid secretory mechanisms in mammary epithelial cells. Electrophoresis. 2000;21(16):3470–3482. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(20001001)21:16<3470::AID-ELPS3470>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartz R, et al. Dynamic activity of lipid droplets: protein phosphorylation and GTP-mediated protein translocation. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(8):3256–3265. doi: 10.1021/pr070158j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almahbobi G, Hall PF. The role of intermediate filaments in adrenal steroidogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1990;97(Pt 4):679–687. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen WJ, et al. Ablation of vimentin results in defective steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153(7):3249–3257. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu N, et al. The FATP1-DGAT2 complex facilitates lipid droplet expansion at the ER-lipid droplet interface. J Cell Biol. 2012;198(5):895–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang C, Liu Z, Huang X. Rab32 is important for autophagy and lipid storage in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jo Y, Hartman IZ, DeBose-Boyd RA. Ancient ubiquitous protein-1 mediates sterol-induced ubiquitination of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase in lipid droplet-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(3):169–183. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bosma M, et al. The lipid droplet coat protein perilipin 5 also localizes to muscle mitochondria. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;137(2):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0888-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo Y, et al. Functional genomic screen reveals genes involved in lipiddroplet formation and utilization. Nature. 2008;453(7195):657–661. doi: 10.1038/nature06928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stevanovic A, Thiele C. Monotopic topology is required for lipid droplet targeting of ancient ubiquitous protein 1. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(2):503–513. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M033852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang CW, Lee SC. The ubiquitin-like (UBX)-domain-containing protein Ubx2/Ubxd8 regulates lipid droplet homeostasis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 12):2930–2939. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olzmann JA, Richter CM, Kopito RR. Spatial regulation of UBXD8 and p97/VCP controls ATGL-mediated lipid droplet turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(4):1345–1350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213738110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koves TR, et al. PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha contributes to exerciseinduced regulation of intramuscular lipid droplet programming in mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(2):522–534. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P028910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, et al. LSDP5 enhances triglyceride storage in hepatocytes by influencing lipolysis and fatty acid beta-oxidation of lipid droplets. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e36712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang W, Napoli JL. The retinol dehydrogenase Rdh10 localizes to lipid droplets during acyl ester biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(1):589–597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.402883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Testerink N, et al. Replacement of retinyl esters by polyunsaturated triacylglycerol species in lipid droplets of hepatic stellate cells during activation. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kraemer FB, et al. Adrenal neutral cholesteryl hydrolase: identification, subcellular distribution and sex differences. Endocrinology. 2002;143(801–806) doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kraemer FB, et al. Hormone-sensitive lipase is required for high-density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester-supported adrenal steroidogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(3):549–557. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shen WJ, Patel S, Eriksson JE, Kraemer FB. Vimentin is a functional partner of hormone sensitive lipase and facilitates lipolysis. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(4):1786–1794. doi: 10.1021/pr900909t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shen WJ, et al. Interaction of hormone-sensitive lipase with steroidogenic acute regulatory protein: facilitation of cholesterol transfer in adrenal. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(44):43870–43876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilfling F, et al. Triacylglycerol synthesis enzymes mediate lipid droplet growth by relocalizing from the ER to lipid droplets. Dev Cell. 2013;24(4):384–399. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Velikkakath AK, Nishimura T, Oita E, Ishihara N, Mizushima N. Mammalian Atg2 proteins are essential for autophagosome formation and important for regulation of size and distribution of lipid droplets. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(5):896–909. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Millership S, et al. Increased lipolysis and altered lipid homeostasis protect gamma-synuclein-null mutant mice from diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(51):20943–20948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210022110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]