Abstract

The mechanism behind the selective depletion of CD4+ cells in HIV infections remains undetermined. Although HIV selectively infects CD4+ cells, the relatively few infected cells in vivo cannot account for the extent of CD4+ T cell depletion suggesting indirect or bystander mechanisms. The role of virus replication, Env glycoprotein phenotype and immune activation (IA) in this bystander phenomenon remains controversial. Using samples derived from HIV-infected patients; we demonstrate that while IA in both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets correlates with CD4 decline, apoptosis in CD4+ and not CD8+ cells is associated with disease progression. As HIV-1 Env glycoprotein has been implicated in bystander apoptosis, we cloned full length Envs from plasma of viremic patients and tested their Apoptosis Inducing Potential (AIP). Interestingly, AIP of HIV-1 Env glycoproteins were found to correlate inversely with CD4:CD8 ratios suggesting a role of Env phenotype in disease progression. In vitro mitogenic stimulation of PBMCs resulted in upregulation of IA markers but failed to alter the CD4:CD8 ratio. However, co-culture of normal PBMCs with Env expressing cells resulted in selective CD4 loss that was significantly enhanced by IA. Our study demonstrates that AIP of HIV-1 Env and IA collectively determine CD4 loss in HIV infection.

Introduction

Progressive depletion of CD4+ T cells by HIV-1 results in AIDS. As HIV-1 selectively infects CD4+ T cells, it is not surprising that the disease is characterized by several immune manifestations. Virus replication, CD4+ T cell apoptosis and immune activation are some of the hallmarks associated with disease progression and AIDS development. As there is a strikingly strong correlation between immune activation (defined by upregulation of activation markers like CD38, HLADR, CCR5 and PD-1) on T cells and CD4+ loss in AIDS, it is believed that immune activation is the driving force behind this HIV pathology (1). Surprisingly, the mechanism of immune activation remains controversial and roles for virus replication (2, 3), gut leakage and LPS translocation (4, 5) have been proposed as mechanisms influencing CD4+ decline.

While immune activation is an immunopathological hallmark of HIV infection and CD4+ T cell decline in patients correlates with this phenomenon, it is also true that suppressing virus replication with ART in many cases reduces immune activation (2, 6–9). This suggests that some viral component or active virus replication enhances immune activation. Interestingly, majority of activated cells defined as CD38+HLADR+ are in the CD8+ compartment (10) while the majority of T cell loss leading to AIDS is in the CD4+ compartment. Hence, the mechanism of the immune activation, its role in CD4+ T cell loss and the role played by the virus in this process remains uncertain.

The HIV Envelope (Env) glycoprotein is a major determinant of virus transmission and has been implicated in HIV pathogenesis via a variety of mechanisms (11). Amongst these, induction of bystander apoptosis via interactions between infected Env expressing cells and receptor/co-receptor expressing uninfected bystander cells has been suggested as one of the mechanisms contributing to CD4+ T cell decline (12–17). We have previously demonstrated the phenomenon of bystander apoptosis mediated by HIV Env both in vitro (18, 19) and in vivo (20), and found that Env fusogenic activity correlates with bystander apoptosis and CD4 decline, but not virus replication. This phenomenon is not limited to lab adapted viruses but also seen with a variety of Envs derived from HIV-infected patients (21). The high variability in the bystander apoptosis inducing potential (AIP) of primary Envs suggests that phenotypic variability may play a role in the differential rates of disease progression. However, does HIV Env-mediated bystander apoptosis correlate with other immunopathological markers such as immune activation, and whether these factors independently or collectively determine CD4 loss remains unknown. Moreover, while it is clear that selective apoptosis of uninfected bystander CD4+ T cells is a driving force behind T cell loss, the mechanism of bystander apoptosis remains highly debated (22, 23). Halt in CD4 decline/apoptosis and partial recovery of CD4+ cells in HAART suppressed patients (24, 25) further supports a role of virus and/or viral proteins in mediating CD4+ loss.

In this study, we analyzed samples from 50 HIV-infected patients for multiple immunopathological markers including those for immune activation as well as apoptosis in CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Furthermore, we cloned full-length functional env genes from 11 viremic HIV+ patients and characterized the derived Env glycoproteins for their Apoptosis Inducing Potential (AIP) using a unique assay developed in our lab (21). Our results demonstrate that the AIP of patient Envs correlates inversely with the CD4:CD8 ratios. Interestingly, our data also demonstrates that HIV-1 Env-mediated bystander apoptosis in PBMCs is enhanced by immune activation. Multivariate analysis shows that the AIP of Envs in combination with immune activation is highly predictive of CD4+ decline. We demonstrate here, for the first time, that Env glycoprotein phenotype, as assessed by AIP, in combination with immune activation plays a significant role in CD4 decline and HIV pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center’s regional Institutional Review Board. The study design was cross-sectional and the study number recorded as IRB# E12092, approval date 07/31/2012. All participants were provided with written and oral information about the study. Written informed consent of all study participants in accordance with the Institutional policy was documented. All participants were identified by coded numbers to assure anonymity and all patient records kept confidential.

Study population

A cohort of 50 HIV-infected individuals was recruited from the outpatient HIV clinic at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at El Paso (Table S1). The mean age of the patient population was 37.9 ± 11.9. The population comprised of 9 females (18.0 %) and 41 males (82.0 %). Samples were collected randomly as per availability and the patients were at different stages of HIV disease progression. An age and gender matched healthy population control group (n=17) was also recruited from the same geographical location and comprised of 3 females (17.7%) and 14 males (82.4%). The mean age of the healthy control group was 35.4 ± 11.8. Clinical data including plasma viremia, CD4 counts, ethnicity and HAART status were recorded from the patient charts (Table S1).

Sample collection and storage

Blood (20ml) from each patient was collected in EDTA vacutainer tubes, stored cold and transported immediately to the lab for processing. Blood was then separated into cell components and plasma by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min. Plasma samples were aliquoted, labeled by unique patient identification codes and stored at −70°C until needed for further assays. Thereafter, lymphocytes were separated from whole blood using the sucrose density gradient (Ficoll) centrifugation protocol (GE Healthcare) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. The PBMCs separated via Ficoll were washed extensively, resuspended in freezing media (90% FBS/10%DMSO) and cryopreserved for future analyses.

Immunostaining and in-vitro T cell activation

Cryopreserved lymphocytes isolated from the blood samples obtained from HIV-infected or normal patients were quickly thawed in a 37°C water bath and washed with PBS. Cells were then stained for cell surface markers using specific antibodies. The immune activation panel consisted of antibodies CD3-Cy7, CD4-Tx red, CD8-APC along with immune activation markers CD38 PE and HLA-DR FITC (BD Pharmingen) (Figure S1A). The apoptosis panel comprised of the following antibodies CD3-Cy7, CD4-Tx Red, CD8-APC (Beckman Coulter) along with CaspACE FITC-VAD-FMK (Promega) (Figure S1B). Stained cells were washed and fixed using Cytofix reagent (Beckman coulter) and acquired on a 10 color Beckman Coulter Gallios flow cytometer. At least 20,000 events for each sample were acquired. Data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). Cells were first gated on CD3+ population and immune activation/apoptosis on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets determined (Figure S1A & B). For in vitro T cell activation, lymphocytes were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS and Phytoheamagglutinin (Sigma) at 2.5 μg/ml and IL-2 (Roche) at 10U/ml for 48h, stained and analyzed as above for immune activation markers and CD4:CD8 ratios (Figure S2).

Env cloning

Viral RNA was isolated from the plasma samples using the QiaAmp viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol followed by cDNA synthesis using the ProtoScript II first strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England Biolabs). The full length Env region (containing the open reading frames for the Env and Rev genes) was then amplified with subtype B specific primers and a nested PCR reaction using the Phusion High Fidelity PCR kit (New England Biolabs). The amplified Env region was cloned into the pCDNA3.1+ vector using the pCDNA3.1 directional TOPO® expression kit (Invitrogen) followed by full length sequencing analysis to verify the authenticity of the inserts. Contigs were established using DNA star software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) and Env Open reading frames for all constructs established. Functionality of each Env was determined by generating pseudotyped HIV particles using Env constructs and pNLLuc R-/E- as described below.

Cell Lines and Transfections

SupT1 cells expressing CCR5 were maintained in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin streptomycin (5000U/ml) and Blasticidin at a concentration of 3μg/ml. 293T, HeLa and TZM-bl cells (NIH AIDS research and reference reagent program) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagles medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin streptomycin (5000U/ml). U87-CXCR4 and U87-CCR5 cells were maintained in DMEM-10% FBS supplemented with 1 μg/ml Puromycin and 300 μg/ml G418. All transfections were conducted using the Turbofect Transfection reagent (Fermentas) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Virus Infectivity Assays

293T cells were transfected with the pNLLuc-R-/E- (26) HIV backbone along with different Env constructs. Virus stocks were harvested 48h post transfection and used to infect the indicator TZM-bl cells line in the presence of 20μg/ml DEAE dextran (Sigma). Luciferase activity was determined 48h post infection using the BriteLite Plus Luciferase assay substrate (PerkinElmer). Infectivity for each Env was calculated as percent of YU-2 Env control after subtraction of the background derived from pcDNA3.1 empty vector transfected cells. CXCR4 and CCR5 antagonists AMD-3100 and Maraviroc respectively were used as described below.

Bystander apoptosis assay

Bystander apoptosis inducing potential of cloned Envs was determined using a co-culture assay described previously (21). Briefly, HeLa cells transfected with the lab adapted or cloned primary Env constructs were co-cultured either with SupT-R5-H6 cells (27) or resting or activated PBMCs. 24 hours post co-culture apoptosis was determined using Caspase Glo 3/7 assay (Promega) that detects caspase 3/7 activity in culture lysates. Lai (CXCR4 tropic) or YU-2 (CCR5 tropic) Envs were used as a positive controls and pcDNA 3.1+ empty vector as the negative control. Percent apoptosis was determined after normalizing data to YU-2 control as 100% and pcDNA 3.1 as 0%. For some experiments AMD-3100 (4μM), Maraviroc (MVC) (2μM), T-20 (8μM), DEVD (50μM) was added at the time of co-culture. For treatment with VX765 (10μM) the cells were preincubated for 4h prior to co-culture.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA) and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Differences between groups were assessed using the Fisher’s exact test or the two-sample t-test as appropriate. All p values were two-sided and data were considered significant at p<0.05. Spearman’s correlation with linear regression was used for all correlation determination using the GraphPad Prism Software. For multivariate analysis of AIP, CD4 immune activation and plasma viremia in predicting CD4 loss in AIDS patients, the calculation of Spearman rank correlation coefficients was followed by multiple linear regression analyses in which overall and partial F tests were performed using an alpha of 0.05.

Results

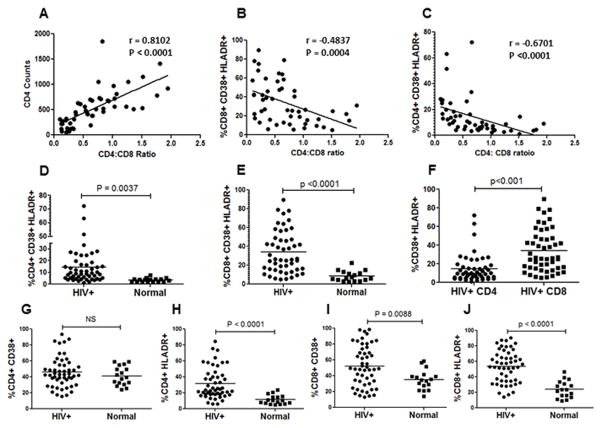

Immune activation in CD8+ T cells is significantly higher than CD4+ T cells in HIV infected individuals

Immune activation, defined by the overexpression of CD38 and HLADR on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, is recognized as a highly correlative marker of HIV disease progression and CD4 loss (28, 29). Recently, CD4:CD8 ratios have been shown as a better lab predictor of combined T cell pathogenesis in HIV-infected patients (30). Hence, in our study population we asked whether these markers were upregulated on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and whether they correlated with CD4 decline. As expected, in our study population, we found the CD4:CD8 ratios to be very strongly associated with CD4+ T cell counts (Figure 1A). We also found the CD4:CD8 ratios to be inversely associated with the immune activation markers CD38 and HLADR in both CD8+ (Figure 1B) and CD4+ T cells (Figure 1C). We next asked whether the percentage of CD38+HLADR+ cells within the CD8+ and CD4+ T cell populations were different between HIV+ individuals and healthy controls. As evident in Figure 1D and E, we found the CD38+HLADR+ population to be increased in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the HIV-infected population. However, the level of immune activation in CD8+ cells was strikingly higher than that seen in CD4+ cells (Figure 1F) (p<0.001). It is important to make this distinction, as it is evident that although immune activation is higher in CD8+ cells in HIV infections, the loss of T cells is largely limited to the CD4+ population. When analyzing for CD38 and HLADR individually, we found that while HLADR upregulation on CD4+ cells was significantly different between HIV positive and healthy controls, CD38 expression was not (Figure 1G and 1H). A similar trend was seen in CD8+ cells with differences in HLADR expression being more pronounced than CD38 upregulation (Figure 1I and J). This suggests that the immune activation phenotype in HIV infection is largely driven by an upregulation of HLADR on CD4+, and to a greater extent on CD8+ T cells. Taken together, these findings suggest that our study population represents an immune activation phenotype consistent with HIV pathology and suitable for further analysis. Also, the disconnect between the higher CD8+ immune activation and a greater CD4+ T cell loss in AIDS merits highlighting.

Figure 1. Immune activation in CD8+ T cells correlates better with CD4+ T cell decline than CD4 immune activation.

PBMCs purified from HIV+ patients or healthy controls were stained for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD38 and HLADR expression followed by flow cytometry analysis. CD4:CD8 ratios were correlated with (A) CD4+ counts (B) immune activation in CD8+ cells (C) immune activation in CD4+ cells in HIV-infected patients. Comparison of (D) CD4+CD38+HLADR+ and (E) CD8+CD38+HLADR+ T cells in HIV-infected versus healthy controls. (F) The percentage of activated CD38+HLADR+ cells is significantly higher (p<0.01) in the CD8+ versus the CD4+ T cell population in HIV-infected individuals. Comparison of (G) CD4+CD38+ (H) CD4+HLADR+ (I) CD8+CD38+ and (J) CD8+HLADR+ cells in HIV-infected versus heathy controls.

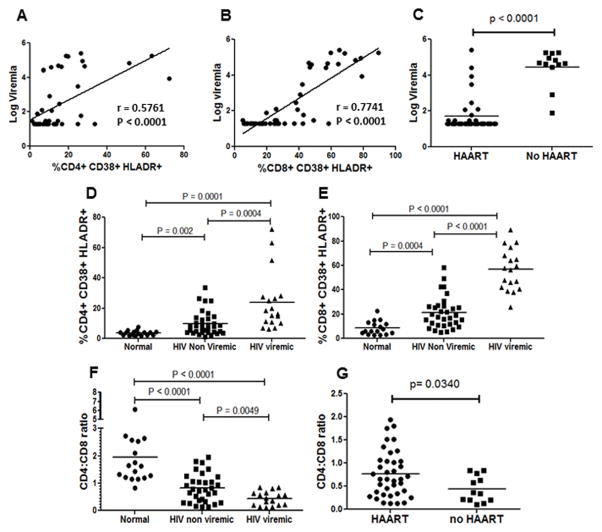

Immune activation correlates with plasma viremia

One of the most extensively investigated questions in HIV research has been the mechanism behind virus mediated immune activation. Many different hypotheses have been put forward including LPS translocation from the gut, role of interferons, activation of Toll Like Receptors (TLRs) etc (1). Despite these numerous hypotheses, the fact that remains undisputed is that virus replication/viremia significantly enhances immune activation (31). This causation hypothesis is further supported by the fact that suppression of virus replication to undetectable levels significantly reduces immune activation (2, 9) and that low levels of virus replication may be associated with residual CD8+ T cell activation (2, 32–34). Therefore, we asked whether immune activation correlates with viral load in our patient samples. A regression analysis revealed that viral load does correlate with CD38+HLADR+ cells in both the CD4+ and CD8+ populations (Figure 2A and B). We also compared viremia between patients on HAART vs no HAART and found that all untreated individuals had detectable viremia and some on HAART were failing therapy (Figure 2C). We next divided our samples into three groups: normal, HIV+ non-viremic and HIV+ viremic (viremia defined as ≥100 virus copies/ml) to determine whether there were differences in immune activation status within these groups. Interestingly, HIV+ viremic group showed the highest immune activation in both the CD4+ (Figure 2D) as well as CD8+ populations (Figure 2E). Once again, immune activation in CD8+ cells was significantly higher than the CD4+ population. Taken together, this set of data supports the hypothesis that virus replication is fundamental to immune activation. Moreover, it is also clear that immune activation in the HIV+ non-viremic group is higher than the normal healthy controls (Figure 2D and E) and a similar trend is seen with the CD4:CD8 ratios (Figure 2F). Significant difference in the CD4:CD8 ratio was also seen between patients on HAART vs no HAART (Figure 2G). Our findings are in agreement with recent reports (33–35) suggesting that virus replication correlates with T cell activation; although, the causality relationship between virus replication and immune activation cannot be concluded.

Figure 2. Immune activation correlates with plasma viremia.

Correlation analysis between log viremia and (A) CD4+CD38+HLADR+ and (B) CD8+CD38+HLADR+ cells in HIV-infected patients. (C) Comparison of viral load in patients on HAART versus no therapy. Comparison of percent (D) CD4+CD38+HLADR+ and (E) CD8+CD38+HLADR+ cells in normal healthy controls, HIV-infected non-viremic and HIV-infected viremic patients. (F) Comparison of CD4:CD8 ratios in normal healthy controls, HIV-infected non-viremic and HIV-infected viremic patients. (G) CD4:CD8 ratios in patients on HAART versus no therapy.

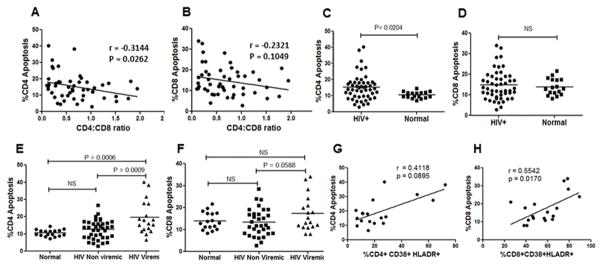

CD4+ but not CD8+ T cell apoptosis correlates with CD4 decline

Apoptosis of CD4+ cells has been recognized as one of the factors leading to the progressive loss of CD4+ cells resulting in immunodeficiency (36). Multiple studies in HIV-infected patients, SIV and humanized mouse model have demonstrated the presence of uninfected bystander cells dying of apoptosis in HIV infections (20, 37–39). PBMCs derived from HIV-infected patients have also been shown to have a higher percentage of apoptotic phenotype (24, 25, 40, 41). Finally, caspase activation has been recognized as a critical mediator of apoptosis seen in HIV-infected patients as well as animal model systems (20, 38). We hence asked whether apoptosis in CD4+ or CD8+ T cell populations was increased in HIV-infected patients. Apoptosis was detected in cells using FITC-VAD-FMK, a peptide that binds to active caspases, along with staining for CD3, CD4 and CD8 to distinguish the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations. We found that while CD4+ apoptosis correlated inversely with CD4:CD8 ratios (p=0.026) (Figure 3A), CD8+ apoptosis did not (p=0.10) (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we found that CD4+ T cell apoptosis was significantly higher in HIV+ patients (p<0.05) (Figure 3C) compared to healthy controls while CD8+ apoptosis was not statistically different (Figure 3D). This data is consistent with our hypothesis that selective apoptosis of CD4+ cells in HIV infections is a major contributing factor in CD4+ T cell loss and AIDS development.

Figure 3. CD4+ but not CD8+ T cell apoptosis correlates with CD4 decline.

PBMCs purified from HIV+ patients or healthy controls were stained for various cell surface markers along with CaspACE FITC-VAD-FMK. Correlation analysis of CD4:CD8 ratios with (A) CD4+ apoptosis (B) CD8+ apoptosis in PBMCs derived from HIV-infected individuals. Analysis of (C) percent CD4+ apoptosis (D) percent CD8+ apoptosis in HIV-infected versus normal healthy controls. Comparison of (E) percent CD4+ apoptosis and (F) percent CD8+ apoptosis in normal uninfected controls, HIV-infected non-viremic and HIV-infected viremic patients. Correlation analysis of (G) CD4+ activation versus CD4 apoptosis and (H) CD8+ activation versus CD8 apoptosis in HIV infected viremic patients.

Based on the observation that CD4+ apoptosis in HIV+ patients is higher, and our previous findings that CD4+ apoptosis is mediated via the HIV Env glycoprotein, (18, 20, 22) we hypothesized that apoptosis should most likely be higher in viremic patients. Moreover, in the absence of significant amounts of virus, as in non-viremic patients, Env-mediated apoptosis would be irrelevant. We again divided our patient population based on viral load into normal, HIV viremic (≥100 virus copies/ml) and HIV non-viremic (<100 virus copies/ml). Interestingly, we found that in the viremic group, CD4+ apoptosis was significantly higher than both HIV non-viremic (P<0.001) and the healthy controls (p<0.001) (Figure 3E). On the other hand, CD8+ apoptosis between the viremic and non-viremic groups, although different, did not reach statistical significance (p=0.058) (Figure 3F). Further analyses of the viremic patients showed that while immune activation correlates with apoptosis for the CD8 group (p= 0.017) (Figure 3H) it does not for the CD4 group (p= 0.0895) (Figure 3G). This suggests that cell death in CD4 and CD8 cells is likely via different mechanism in HIV patients. These findings are further supportive of the idea that selective apoptosis of CD4+ cells in viremic patients may be a contributing factor in CD4+ T cell decline and HIV disease progression. It is worth mentioning that CD4+ apoptosis in the viremic group was variable with some samples showing higher apoptosis than others. It is reasonable to speculate that some of this variability may be a result of lower viral load which would translate to lower Env glycoprotein expression and reduced bystander apoptosis. However, another possibility could be differences in apoptosis inducing potential (AIP) of the viruses these individuals harbor.

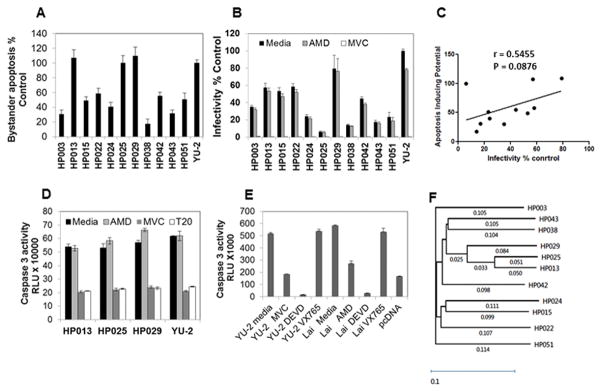

Apoptosis inducing potential (AIP) of Primary Envs is variable

Previously we have demonstrated in a panel of HIV Env glycoprotein variants derived from patients that the bystander apoptosis inducing potential of Envs varies considerably (21). Whether this variability correlates with CD4 decline in vivo and HIV pathogenesis remains unclear. In our set of patient samples, we observed that not all viremic patients showed high CD4 apoptosis or low CD4:CD8 ratios. We hence speculated that these variations were likely due to differences in the Apoptosis Inducing Potential (AIP) of different Envs. To test this, we cloned full length functional Envs from patient plasma samples to determine the AIP of the infecting virus. We were able to clone 11 functional Envs from a total of 18 viremic patients. The clones were sequenced and found to be unique HIV Env sequences, non-identical to any known HIV Env in the NCBI database. The sequence accession numbers are listed in Table 1. A phylogenetic tree showing Env relatedness is depicted in Figure 4F. The Envs were characterized for various phenotypic features including AIP, infectivity and co-receptor usage (Table 1). All the Envs were found to be CCR5 tropic based on U87 tropism assay (Table 1) and inhibition via MVC (Figure 4B). Interestingly, we found that the Envs varied considerably in their AIP with clones HP029, HP025 and HP013 showing highest apoptosis while clones HP003, HP038 and HP043 being towards the lower end of apoptosis inducers (Figure 4A). This variability was also seen for virus infectivity in a single round infectivity assay (Figure 4B). The correlation between infectivity and apoptosis was not statistically significant, (Figure 4C) consistent with our previous observation that AIP and infectivity do not correlate in every case (21). This also supports the notion that Envs or viruses that lack apoptosis inducing activity can still infect and replicate in vivo, as shown previously (20). Interestingly, apoptosis was inhibited in the presence of the CCR5 antagonist Maraviroc and the Fusion inhibitor T-20 suggesting an Env specific effect and a role of HIV fusion activity in this phenomenon (Figure 4D). We also tested whether apoptosis in our co-culture model was dependent on caspase-1. In our model, caspase 1 specific inhibitor VX765 failed to inhibit caspase 3 activity in Env exposed cells while caspase 3 inhibitor Ac-DEVD-fmk inhibited caspase 3 activity in our assay (Figure 4E). Phylogenetic analysis showed a close relatedness between HP013, HP025 and HP029 (Figure 4F), all high apoptosis inducers, further supporting a role of Env glycoprotein in CD4+ cell apoptosis. A complete profile analysis of the patients revealed two highly interesting phenotypes with HP029 and HP043 representing two extreme ends of HIV pathogenesis spectrum (Table 1). While both patients were viremic and showed similar immune activation, they were markedly different in AIP (109 vs 31) and in vivo CD4 apoptosis (40.17 vs 11.51). This difference was further reflected in their CD4:CD8 ratios (0.13 vs 0.57) and absolute CD4 counts (69 vs 426). This pair represents a perfect example demonstrating the role of Env phenotype in determining CD4 loss and AIDS development.

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Data for the 11 Env clones obtained from viremic HIV+ patients.

| Sample | Age | Sex | CD4 counts | CD8 Activation | CD4 Activation | In vivo CD4 Apoptosis | Viremia | CD4: CD8 ratio | AIP | Infectivity | Subtype | Tropism U87 assay | Tropism MVC inhibition | Geno2Phe no FPR (Tropism) | GenBank accession numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP003 | 36 | M | 119 | 59.7 | 18.6 | 27.82 | 181680 | 0.34 | 30 | 35 | B | R5 | R5 | 58.3 (R5) | KP754463 |

| HP013 | 36 | F | 292 | 68.3 | 19.8 | 11.43 | 164460 | 0.20 | 107 | 57 | B | R5 | R5 | 48.9 (R5) | KP754464 |

| HP015 | 32 | F | 49 | 89.4 | 63.2 | 27.61 | 177430 | 0.21 | 49 | 53 | B | R5 | R5 | 78.8 (R5) | KP754465 |

| HP022 | 28 | M | 323 | 71.5 | 23.4 | 16.49 | 67700 | 0.20 | 58 | 58 | B | R5 | R5 | 14.3 (R5) | KP754466 |

| HP024 | 23 | M | 413 | 47.8 | 10.9 | 18.66 | 40430 | 0.57 | 40 | 24 | B | R5 | R5 | 82.4 (R5) | KP754467 |

| HP025 | 29 | M | 456 | 45.9 | 14.7 | 18.15 | 48750 | 0.37 | 100 | 6 | B | R5 | R5 | 24.7 (R5) | KP754468 |

| HP029 | 36 | M | 69 | 78.3 | 27.3 | 40.17 | 91190 | 0.13 | 109 | 79 | B | R5 | R5 | 7.4 (R5) | KP754469 |

| HP038 | 32 | F | 466 | 46.8 | 6.99 | 9.72 | 27810 | 0.84 | 17 | 14 | A or AG | R5 | R5 | 34.3 (R5) | KP754470 |

| HP042 | 25 | M | 482 | 56.5 | 6.9 | 15.14 | 25420 | 0.54 | 55 | 44 | B | R5 | R5 | 35.3 (R5) | KP754471 |

| HP043 | 27 | M | 426 | 65 | 26.3 | 11.51 | 259100 | 0.57 | 31 | 17 | B | R5 | R5 | 76.5 (R5) | KP754472 |

| HP051 | 18 | F | 191 | 64.2 | 16.3 | 12.74 | 41400 | 0.62 | 51 | 23 | B | R5 | R5 | 9.2 (R5) | KP754473 |

Figure 4. Apoptosis inducing potential of Primary Envs correlates with CD4 decline.

(A) HeLa cells transfected with the cloned primary Env constructs were co-cultured with SupT-R5-H6 cells. 24 hours post co-culture, apoptosis was determined using the caspase glo 3/7 assay. YU-2 Env was used as a positive controls and pcDNA 3.1+ empty vector as the negative control. Percent apoptosis was determined after normalizing data to YU-2 control as 100% and pcDNA 3.1 as 0%. (B) Infectivity of the cloned primary Env constructs. Virus stocks were prepared by co-transfecting 293T cells with the pNL-Luc backbone along with the indicated Env constructs. Equal RT cpm of culture supernatants were used to infect TZM-bl cells in the presence of AMD-3100 (4μM) or Maraviroc (2μM) and luciferase activity determined. Infectivity is normalized to YU-2 Env as 100%. (C) Correlation of apoptosis inducing potential of the primary Env constructs with percent infectivity. (D) The co-culture assay described in part A above was conducted with selected primary Envs in the presence of media, AMD-3100 (4μM), Maraviroc (2μM) or T-20 (8μM) added at the time of co-culture. (E) YU-2 or Lai Env expressing HeLa cells were co-cultured with SupT-R5-H6 cells in the presence of indicated inhibitors and apoptosis was determined using the caspase glo 3/7 assay. (F) Phylogenetic analysis of the primary HIV Env clones used in the study. A phylogenetic tree showing Env relatedness was derived using the DNA Star software.

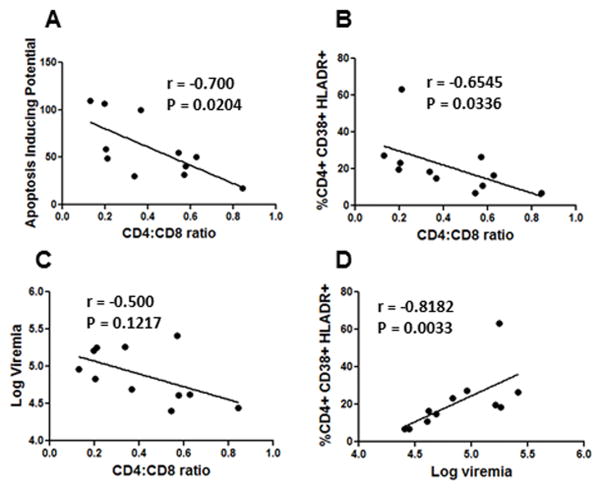

CD4 loss in vivo is a combination of apoptosis inducing potential of Envs and immune activation

Due to the variability in the AIP of the cloned Envs, we next asked whether AIP is associated with in vivo CD4+ T cell loss and disease progression. We hence correlated AIP of Envs with CD4:CD8 ratios and found a strong inverse correlation between the two phenomenon Spearman’s r =−0.70, p=0.020 (Figure 5A). The fact that Envs with higher AIP were associated with lower CD4:CD8 counts and vice versa suggests that AIP of the Envs may have a causal effect on CD4:CD8 ratios during HIV disease progression. This is consistent with our hypothesis that Env glycoprotein phenotype is one of the determinants of CD4 loss and AIDS development. Having characterized the AIP of Envs and establishing a correlation between AIP and CD4:CD8 ratios, we next asked whether AIP alone is responsible for the CD4 loss seen in patients or if other factors like immune activation and viremia also contribute to T cell pathology in vivo. Interestingly, we found that the CD4:CD8 ratios also correlated with immune activation Spearman’s r= −0.6545, p= 0.0336 (Figure 5B). However a correlation between viremia and CD4:CD8 ratios in this group of viremic patients could not be established, Spearman’s r= −0.50, p=0.121 (Figure 5C). This is not surprising considering that all viruses are different in terms of AIP. Nonetheless, viremia and immune activation correlated well in this group Spearman’s r= −0.8182 p=0.0033 (Figure 5D), further supporting the notion that viremic patients have higher immune activation and that virus replication likely plays a role in this process. The fact that in vivo CD4 immune activation and AIP correlate with CD4 decline suggests that bystander apoptosis as well as immune activation are important for the loss of CD4 cells. At the same time, viremia did not necessarily correlate with T cell pathology in “viremic” patients suggesting that all viruses are not the same. A multivariate analysis (Table 2) showed that AIP was an adequate predictor of CD4:CD8 ratios (R2=0.40 p=0.021); however, inclusion of CD4 immune activation in the model significantly improved the prediction of CD4:CD8 ratios (R2=0.65, p=0.006) further establishing that these two variables collectively determine CD4 loss. In the same model, adding log viremia did not increase the significance or correlation any further. Hence, within patients with similar viremia, (>20,000 copies/ml) the determinants of CD4 loss are largely AIP of the infecting virus and immune activation.

Figure 5. CD4 loss in vivo is a combination of Apoptosis Inducing Potential (AIP) of Envs and immune activation.

(A) Correlation analysis of AIP of Envs with CD4:CD8 ratios shows an inverse correlation between the two phenomenon. (B) Correlation of CD4:CD8 ratios with CD4+ immune activation. (C) Correlation analysis between plasma viremia and CD4:CD8 ratios. (D) Correlation analysis between patient plasma viremia and CD4+ immune activation.

Table 2.

A multivariate analysis of AIP, CD+ immune activation and log viremia as a predictor of CD4:CD8 ratios in HIV-infected patients.

| Model | Predictors in the model | Adjusted R2 | Overall P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apoptosis inducing potential (AIP) | 0.40 | 0.021 |

| 2 | AIP, CD4 immune activation | 0.65 | 0.006 |

| 3 | AIP, CD4 immune activation, Log viremia | 0.67 | 0.013 |

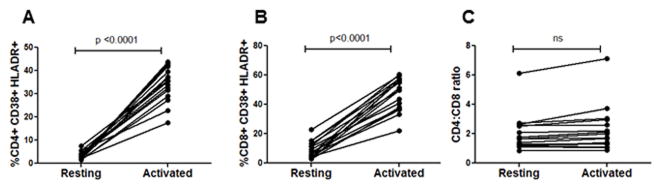

In vitro mitogenic stimulation induces immune activation without altering CD4:CD8 ratios

Chronic immune activation is believed to be a major contributor of immune dysfunction in HIV infections (1). Our findings above also suggest that immune activation in combination with AIP correlates with CD4+ T cell loss. We next asked whether in vitro stimulation of PBMCs using mitogens would mimic the immune activation profile seen in HIV infection. For this, PBMCs from healthy donors were stimulated with PHA and IL-2 and cells stained for various markers prior to and 48 hours post stimulation including estimation of CD4:CD8 ratios. This method of stimulation resulted in an upregulation of CD38 and HLADR on both CD4+ (Figure 6A) and CD8+ (Figure 6B) T cell populations similar to that seen in HIV-infected patients. Although there was an increase in CD38+HLADR+ cells in all the samples, (Figure 6A and B) activation of cells in vitro did not alter the CD4:CD8 ratio (Figure 6C). This suggests that in vitro mitogenic stimulation generates cells with an activated phenotype without altering the CD4:CD8 ratios. In a more relevant in vivo model, Hofer et al (42) demonstrated that experimental induction of intestinal damage and microbial translocation in humanized mice resulted in immune activation but failed to alter CD4:CD8 ratio or induce a specific loss of CD4+ T cells.

Figure 6. Immune activation per se does not alter the CD4:CD8 ratios.

Lymphocytes obtained from HIV negative healthy donors were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS and phytoheamagglutinin at 2.5 μg/ml and IL-2 at 10U/ml for 48h. Cells were then stained for immune activation markers as described in Figure 1. Increase in percentage of CD38+HLADR+ cells in the (A) CD4+ (B) CD8+ population after 48h of activation. (C) No significant alteration in the CD4:CD8 ratio after 48h of immune activation in vitro.

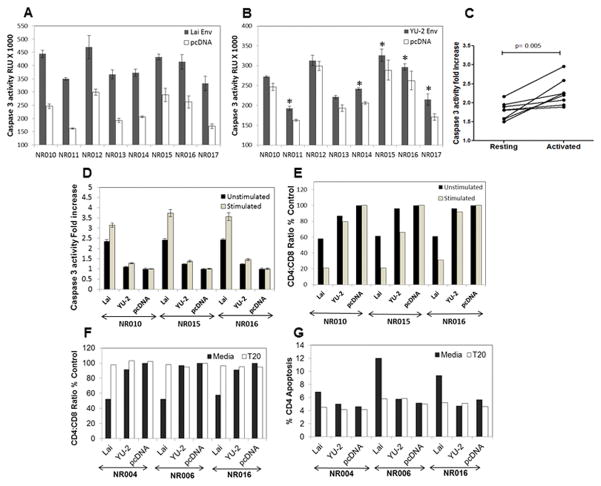

Immune activation enhances Env-mediated bystander apoptosis in PBMCs

Several lines of evidence suggest that immune activation, specifically in CD4+ cells, can enhance virus replication by creating additional targets for HIV infection (31). Our data suggests that AIP of primary Envs in combination with immune activation correlates strongly with in vivo CD4+ apoptosis as well as declining CD4:CD8 ratios. We hence asked whether immune activation can enhance bystander apoptosis mediated by HIV Env and if the presence of viral Env in the culture conditions in Figure 6C would induce apoptosis in activated PBMCs. To address this, we utilized an assay where PBMCs from heathy donors were co-cultured with cells expressing Lai Env (X4), YU-2 Env (R5) or a vector control (pcDNA3.1). Apoptosis was determined 24h later via caspase 3 activity measurement. Interestingly, we found that both X4 (Lai) (Figure 7A) as well as an R5 Env (YU-2) (Figure 7B) were able to induce caspase 3 activation in resting PBMCs. Apoptosis induction by YU-2 Env, although higher than vector control in 5 out of the 8 samples was not comparable to Lai Env. This is most likely due to the paucity of CD4+ CCR5+ cells in peripheral blood (Figure S3B), consistent with our previous report where X4 Env induced higher apoptosis than R5 Env in peripheral blood purified CD4+ T cells (21). More interestingly, when cells were activated with PHA and IL-2 and then co-cultured with Lai Env expressing cells, apoptosis induction in the co-cultures was significantly higher than in resting cells for all the donors p<0.005 (Figure 7C). These studies suggest that while immune activation is a pathological hallmark associated with AIDS, this phenomenon per se in the absence of HIV Env fails to induce specific loss of CD4+ cells as seen in HIV infections. However, from the above experiment it remains uncertain whether CD4+ cells were the actual source of caspase 3 activation and whether Env-mediated apoptosis leads to a specific loss of CD4+ cells. Hence, we repeated the above experiments to perform staining for CD4+ and CD8+ cells in parallel with caspase 3 activity determinations. Once again, we found that both X4 (Lai) as well as an R5 (YU-2) Env was able to induce caspase 3 activation in unstimulated PBMCs which was enhanced when cells were activated with PHA and IL-2 (Figure 7D). Interestingly, we found that co-culture with Env expressing cells resulted in a decrease in CD4:CD8 ratio much in line with what is seen in HIV-infected patients (Figure 7E). Furthermore, the decrease in CD4:CD8 ratio was more pronounced in activated cells than unstimulated PBMCs (Figure 7E) in accordance with greater increase in caspase 3 activity in activated cultures (Figure 7D). We also found that increase in CD4+ apoptosis as well as decrease in CD4:CD8 ratios were both inhibited by the HIV Env fusion inhibitor T20 (Figure 7F and G and Figure S3A) confirming that apoptosis was specific to CD4+ cells and mediated by the fusion activity of Env glycoprotein. Surprisingly, these in vitro assays, whereby PBMCs were exposed to Env expressing cells, reproduced many of the pathological features seen in HIV infection in vivo including a specific loss of CD4 cells and increased CD4 depletion via immune activation. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that Env-mediated bystander apoptosis is the major cause of CD4+ loss during AIDS progression with immune activation playing a significant role in enhancing this phenomenon.

Figure 7. Immune activation enhances Env-mediated bystander apoptosis in PBMCs.

Unstimulated PBMCs from heathy donors were co-cultured with HeLa cells expressing either (A) Lai Env or (B) YU-2 Env along with a vector control. Apoptosis was determined 24h later via caspase 3 activity measurement (*=p<0.05). (C) Fold increase in caspase 3 activity in resting versus PHA+IL-2 activated PBMCs when co-cultured with Lai Env expressing HeLa cells. (D) PBMCs derived from healthy donors NR010, NR015 and NR016 were either left unstimulated or activated with PHA and IL-2. These PBMCs were then co-cultured with HeLa cells expressing Lai Env, YU-2 Env or vector control followed by measurement of caspase 3 activity in cultures after 24 hrs. (E) Experiment in part D was repeated to determine the CD4:CD8 ratios by flow cytometry after 24 hrs of co-culture. The CD4:CD8 ratio was determined after normalizing to control pCDNA3.1 transfected cells. (F) PBMCs derived from healthy donors NR004, NR006 and NR016 were activated and then co-cultured with Lai Env, YU-2 Env or pCDNA3.1 control vector expressing HeLa cells. In some cultures, T-20 was added at the time of co-culture. CD4:CD8 ratios were determined after staining for surface CD4 and CD8 expression. (G) Percent CD4 apoptosis was determined via surface CD4 and CaspACE FITC-VAD-FMK staining followed by flow cytometry.

Discussion

After more than 30 years of research, the mechanism via which HIV infection leads to CD4+ T cell depletion and AIDS development remains unclear. Two critical immunopathological markers of HIV infections are bystander apoptosis (37) and immune activation (1). While both apoptosis and immune activation correlate with disease progression and AIDS development, the interdependence of these factors remains unclear. Whether immune activation leads to apoptosis of CD4+ cells or does loss of CD4+ cells by apoptosis and/or virus replication drives immune activation remains a fundamental yet unanswered question. Another critical player in HIV pathogenesis is the viral Env glycoprotein, which is known to vary both between and within individuals and with the stage of the disease (43–46). The higher rate of disease progression in animal models in many cases can be traced back to the phenotype of Env glycoprotein in both SHIV model in Macaques (47–49) and HIV infection in humanized mice (20).

Apoptosis of uninfected bystander cells has long been believed to be the cause of CD4+ decline and AIDS development (11, 22, 37). The Env glycoprotein comes forth as a likely mediator in the process as it specifically binds to the CD4 receptor and is expressed on the surface of infected cells whereby it can interact with bystander cells. Interestingly, Env glycoprotein expressed on the surface of effector cells has the potential to mediate bystander apoptosis in CD4+ T cells (14, 16, 18, 46, 50). This phenomenon is dependent on membrane fusion potential of the Env glycoprotein (11, 12) and varies considerably between primary Envs (21). We have previously demonstrated that altering the fusion capacity of Env glycoprotein can alter bystander apoptosis and CD4+ decline in humanized mouse model without affecting virus replication (20). Based on these model systems, it is reasonable to speculate that the Apoptosis Inducing Potential (AIP) of Env glycoprotein could potentially be related to CD4+ decline and AIDS development and explains why some individuals progress to AIDS faster than others (45, 46, 51, 52).

While a vast majority of studies support the hypothesis that bystander cells are lost via classical apoptosis (36, 37, 53, 54) in HIV infection; recently a different mechanism of cell death termed pyroptosis has been implicated in HIV mediated CD4+ T cell loss (55). Early studies suggested that abortive infection by HIV particles initiates caspase 1 dependent pyroptosis of bystander cells (56) as well as IL-1 production (55). In our system we have measured apoptosis using FITC-VAD-fmk reagent that binds all active caspases and not caspase 3 specifically. Whether some cells in our assays are dying via caspase-1 dependent pyroptosis cannot be ruled out. However, a recent study suggests that close cell to cell contact is essential even for pyroptotic death in human lymphoid aggregate cultures (HLAC) (57) which is consistent with our model of close contact between Env expressing and bystander target cells. Differences in the mechanism of cell death in vitro may be a consequence of different cell systems used as demonstrated by other groups (15). Nevertheless in vivo evidence for a role of caspase 3 dependent apoptosis in CD4 T cell loss in HIV/SIV infections is overwhelming (12, 20, 38, 39, 58, 59).

The fundamental question in our study was how immune activation, CD4+ T cell apoptosis and Env glycoprotein phenotype collectively determine AIDS progression. Firstly, we found that CD8+ immune activation was higher than CD4+ T cell activation in HIV+ individuals. More interestingly, viremic patients showed higher immune activation than non-viremic, indicating a role for virus replication in driving immune activation, which is consistent with several recent reports linking viremia to immune activation in CD8+ cells (32, 33, 60). The mechanism by which viremia may induce immune activation could be via plasmacytoid dendritic cells as recently suggested by Li et al (3), or direct damage of intestinal integrity, or depletion of Th17 cells in the gut mucosa by HIV leading to microbial translocation (9, 58). Intensification of HAART therapy using raltegravir has recently been shown to reduce CD8+ T cell activation further supporting a causal relationship between viremia and immune activation (2). Secondly, we found that while CD4+ apoptosis was higher in HIV+ individuals compared to normal controls, CD8+ apoptosis was not statistically different. This in turn indicates that immune activation may not be the direct cause of HIV mediated CD4 loss, as the cells dying in HIV infection are CD4+, although activation is higher in CD8+ cells.

To specifically address the role of Env phenotype in CD4+ loss and AIDS progression, we cloned 11 full length functional Envs from viremic patients and asked whether the AIP of the Envs correlated with CD4+ decline. We show here for the first time, that indeed the bystander apoptosis inducing potential or AIP of Envs is inversely related to CD4:CD8 ratios, a well characterized marker of HIV mediated immunopathology and CD4+ decline (30). While AIP alone was a strong predictor of CD4+ T cell pathology (CD4:CD8 ratio); addition of immune activation in a multivariate analysis significantly enhanced the correlation. This supports the idea that immune activation and Env glycoprotein may synergize in mediating bystander CD4+ T cell apoptosis. In the same analysis, immune activation and viremia strongly correlated in the selected group of high viremic patients. This further emphasizes the multifactorial nature of HIV mediated CD4+ loss and supports the hypothesis that immune activation as well as Env phenotype collectively determine bystander apoptosis.

To further investigate the issue of Env glycoprotein and immune activation synergy, we first determined whether immune activation per se would alter CD4:CD8 ratios. In vitro stimulation of normal PBMCs failed to induce a specific CD4+ decline although the cells exhibited CD38+HLADR+ upregulation similar to that seen in HIV infections. In other more relevant in vivo models, experimental induction of immune activation failed to induce a specific CD4+ decline in both humanized mice (42) and Macaques (61) in the absence of HIV infection. Hence, we hypothesized that presence of virus/Env glycoprotein in the cultures would be essential for mediating specific CD4+ loss. Interestingly, while HIV Env (specifically Lai Env) was capable of inducing bystander apoptosis and CD4 decline in unstimulated cells; immune activation significantly enhanced apoptosis and CD4 decline in this model. Interestingly, this model system recapitulates many of the immunopathological changes seen in HIV infection including specific loss of CD4 cells, inversion of CD4:CD8 ratios and increased pathology via immune activation. In this same model, we were able to demonstrate the requirement of Env glycoprotein mediated membrane fusion in inducing CD4+ cell loss by specifically inhibiting the process via the gp41 inhibitor T20 as seen previously (18, 19). Although similar, the effects were less dramatic with the R5 Env (YU-2), which was expected due to a paucity of CCR5 positive cells in the peripheral blood, also seen previously (21). In this regard, one must keep in mind that most of the pathology of R5 viruses is in the Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) (62) due to an abundance of CCR5+ cells and the same mechanisms would be far more dramatic in the GALT.

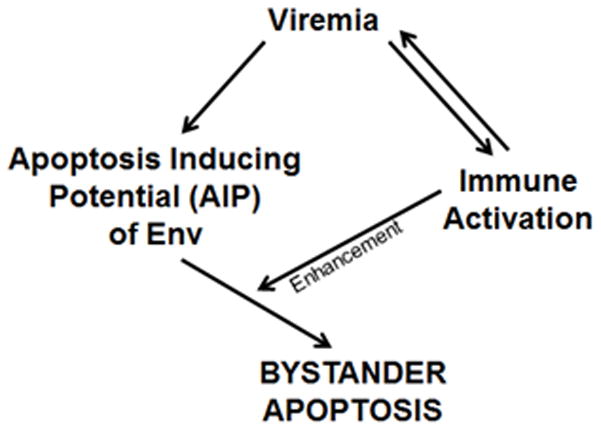

Based on these findings, we provide a simplistic model of HIV pathology (Figure 8). In this model, virus replication or viremia is responsible for immune activation and for the Env phenotype or AIP to be manifested. In the absence of viremia, Env-mediated apoptosis would be irrelevant. Once there is viremia, in the presence of an apoptosis inducing Env (high AIP), this would lead to bystander apoptosis in CD4+ T cells which in turn would be significantly enhanced by immune activation resulting in reduced CD4:CD8 ratios. Another important manifestation would be enhancement of virus replication via immune activation and consequently an increase in the number of Env expressing cells. Hence, immune activation in vivo is likely working on two fronts by a) enhancing the number of infected cells expressing Env b) rendering the uninfected bystander cells more vulnerable to apoptosis via the Env glycoprotein (Figure 8). This trifecta of virus replication, immune activation and Env-mediated apoptosis would result in progressive loss of CD4 cells leading to AIDS.

Figure 8.

Model proposing how virus replication, immune activation and Env-mediated apoptosis would result in progressive loss of CD4+ cells during HIV disease progression leading to AIDS.

Although this model is simplistic, it explains why patients HP029 and HP043 have different outcomes in terms of CD4+ cells in spite of similar virus replication and immune activation. A lack of AIP (as determined in our study) for HP043 Env is manifested by preservation of CD4+ cells despite the presence of high viremia, while HP029 represents the opposite scenario. This pair is also reminiscent of our humanized mouse study where the V38E Env mutant virus (similar to HP043 Env) that lacks AIP (19) replicated to high levels and induced immune activation without causing CD4 apoptosis and decline (20). Our model may also provide an explanation for a number of recent clinical findings. For example, in viremic slow progressors (VSP), virus replication and immune activation are not sufficient for CD4+ loss as reported by Shaw (63) and Klatt et al (64). In fact, Shaw et al suggested a possible role of virological features in preservation of CD4+ cells which is in agreement with our findings. Interestingly, differences in the nef gene do not account for the preservation of CD4+ cells in these patients (64, 65). It is hence tempting to speculate that differences in AIP of the infecting virus or differences in the ability of CD4+ T cells from VSPs to undergo bystander apoptosis may be responsible for these effects. In this context, one must also consider the CCR5 gene and prompter polymorphisms in these patients which have been found to be associated with disease progression (66, 67). We have previously shown that lower levels of CCR5 can limit bystander apoptosis of Env while maintaining the virus replication potential (27). Our findings also suggest that in highly pathogenic SIV models like SIVsab in pig tailed macaques (PTM), the high AIP of the infecting virus may overcome the immune activation dependence for CD4 loss. Hence, altering immune activation in these animals would have little effect on CD4 loss as seen by Kristoff et al (68). Furthermore, in natural infections in SIV (SIV AGM, SIV SM), a low AIP of the SIV variants in combination with lack of immune activation may protect the uninfected CD4+ cells from bystander apoptosis resulting in a non-pathogenic infection. Reduced cell surface expression of CCR5 co-receptor in natural SIV hosts (69, 70), might also protect against bystander apoptosis in certain subsets of CD4+ T cells. In fact, lack of bystander apoptosis in natural SIV infections is a prominent differentiating marker from pathogenic SIV infections in macaques (38, 39).

Finally, our data suggests that suppressing virus replication would be the best way to inhibit Env-mediated bystander apoptosis and slow disease progression in line with recent clinical findings (24, 25). Our findings also suggest that reducing immune activation may have mixed results in terms of clinical benefits (71–73) due to the high variability in the AIP of Env glycoprotein and viruses with different AIP may benefit differentially from immune activation reduction.

Overall, our study is the first to demonstrate a clear correlation between the Apoptosis Inducing Potential (AIP) of primary Envs and CD4 decline. Our study is also the first to demonstrate the synergy between immune activation and Env glycoprotein mediated bystander apoptosis. Hence, the role of Env-mediated bystander effects and role of immune activation in disease progression may not be exclusive but work in concert to mediate CD4+ loss. Our data supports a hybrid hypothesis whereby the primary mediator of T cell apoptosis is most likely the Env glycoprotein while immune activation acts as an accelerant by enhancing Env-mediated apoptosis as well as virus replication and consequently disease progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This study was supported in part by NIH R15 grant AI116240-01A1 (HG) and the Texas Tech University’s intramural seed grant program.

We would like to thank the patients who agreed to participate in the study by providing valuable samples and the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for providing necessary reagents.

References

- 1.d’Ettorre G, Paiardini M, Ceccarelli G, Silvestri G, Vullo V. HIV-associated immune activation: from bench to bedside. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:355–364. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzon MJ, Massanella M, Llibre JM, Esteve A, Dahl V, Puertas MC, Gatell JM, Domingo P, Paredes R, Sharkey M, Palmer S, Stevenson M, Clotet B, Blanco J, Martinez-Picado J. HIV-1 replication and immune dynamics are affected by raltegravir intensification of HAART-suppressed subjects. Nat Med. 2010;16:460–465. doi: 10.1038/nm.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li G, Cheng M, Nunoya J, Cheng L, Guo H, Yu H, Liu YJ, Su L, Zhang L. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells suppress HIV-1 replication but contribute to HIV-1 induced immunopathogenesis in humanized mice. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004291. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douek D. HIV disease progression: immune activation, microbes, and a leaky gut. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2007;15:114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazenberg MD, Stuart JW, Otto SA, Borleffs JC, Boucher CA, de Boer RJ, Miedema F, Hamann D. T-cell division in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection is mainly due to immune activation: a longitudinal analysis in patients before and during highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Blood. 2000;95:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, Bredt B, Hagos E, Lampiris H, Deeks SG. T cell activation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell gains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with sustained viral suppression during antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1534–1543. doi: 10.1086/374786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohri H, Perelson AS, Tung K, Ribeiro RM, Ramratnam B, Markowitz M, Kost R, Hurley A, Weinberger L, Cesar D, Hellerstein MK, Ho DD. Increased turnover of T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection and its reduction by antiretroviral therapy. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1277–1287. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuetz A, Deleage C, Sereti I, Rerknimitr R, Phanuphak N, Phuang-Ngern Y, Estes JD, Sandler NG, Sukhumvittaya S, Marovich M, Jongrakthaitae S, Akapirat S, Fletscher JL, Kroon E, Dewar R, Trichavaroj R, Chomchey N, Douek DC, OCRJ, Ngauy V, Robb ML, Phanuphak P, Michael NL, Excler JL, Kim JH, de Souza MS, Ananworanich J. Initiation of ART during Early Acute HIV Infection Preserves Mucosal Th17 Function and Reverses HIV-Related Immune Activation. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004543. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villacres MC, Kono N, Mack WJ, Nowicki MJ, Anastos K, Augenbraun M, Liu C, Landay A, Greenblatt RM, Gange SJ, Levine AM. Interleukin 10 responses are associated with sustained CD4 T-cell counts in treated HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:780–789. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg H, Blumenthal R. Role of HIV Gp41 mediated fusion/hemifusion in bystander apoptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3134–3144. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8147-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meissner EG, Zhang L, Jiang S, Su L. Fusion-induced apoptosis contributes to thymocyte depletion by a pathogenic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope in the human thymus. J Virol. 2006;80:11019–11030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01382-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferri KF, Jacotot E, Blanco J, Este JA, Zamzami N, Susin SA, Xie Z, Brothers G, Reed JC, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Apoptosis control in syncytia induced by the HIV type 1-envelope glycoprotein complex: role of mitochondria and caspases. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1081–1092. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanco J, Barretina J, Ferri KF, Jacotot E, Gutierrez A, Armand-Ugon M, Cabrera C, Kroemer G, Clotet B, Este JA. Cell-surface-expressed HIV-1 envelope induces the death of CD4 T cells during GP41-mediated hemifusion-like events. Virology. 2003;305:318–329. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunyat F, Curriu M, Marfil S, Garcia E, Clotet B, Blanco J, Cabrera C. Evaluation of the cytopathicity (fusion/hemifusion) of patient-derived HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins comparing two effector cell lines. Journal of biomolecular screening. 2012;17:727–737. doi: 10.1177/1087057112439890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biard-Piechaczyk M, Robert-Hebmann V, Richard V, Roland J, Hipskind RA, Devaux C. Caspase-dependent apoptosis of cells expressing the chemokine receptor CXCR4 is induced by cell membrane-associated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein (gp120) Virology. 2000;268:329–344. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banda NK, Bernier J, Kurahara DK, Kurrle R, Haigwood N, Sekaly RP, Finkel TH. Crosslinking CD4 by human immunodeficiency virus gp120 primes T cells for activation-induced apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1099–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg H, Blumenthal R. HIV gp41-induced apoptosis is mediated by caspase-3-dependent mitochondrial depolarization, which is inhibited by HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:351–362. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0805430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg H, Joshi A, Blumenthal R. Altered bystander apoptosis induction and pathogenesis of enfuvirtide-resistant HIV type 1 Env mutants. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:811–817. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garg H, Joshi A, Ye C, Shankar P, Manjunath N. Single amino acid change in gp41 region of HIV-1 alters bystander apoptosis and CD4 decline in humanized mice. Virol J. 2011;8:34. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi A, Lee RT, Mohl J, Sedano M, Khong WX, Ng OT, Maurer-Stroh S, Garg H. Genetic signatures of HIV-1 envelope-mediated bystander apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:2497–2514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg H, Mohl J, Joshi A. HIV-1 induced bystander apoptosis. Viruses. 2012;4:3020–3043. doi: 10.3390/v4113020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahr B, Robert-Hebmann V, Devaux C, Biard-Piechaczyk M. Apoptosis of uninfected cells induced by HIV envelope glycoproteins. Retrovirology. 2004;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roger PM, Breittmayer JP, Durant J, Sanderson F, Ceppi C, Brignone C, Cua E, Clevenbergh P, Fuzibet JG, Pesce A, Bernard A, Dellamonica P. Early CD4(+) T cell recovery in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving effective therapy is related to a down-regulation of apoptosis and not to proliferation. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:463–470. doi: 10.1086/338573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roger PM, Breittmayer JP, Arlotto C, Pugliese P, Pradier C, Bernard-Pomier G, Dellamonica P, Bernard A. Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) is associated with a lower level of CD4+ T cell apoptosis in HIV-infected patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:412–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He J, Choe S, Walker R, Di Marzio P, Morgan DO, Landau NR. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi A, Nyakeriga AM, Ravi R, Garg H. HIV ENV glycoprotein-mediated bystander apoptosis depends on expression of the CCR5 co-receptor at the cell surface and ENV fusogenic activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36404–36413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Cumberland WG, Hultin LE, Prince HE, Detels R, Giorgi JV. Elevated CD38 antigen expression on CD8+ T cells is a stronger marker for the risk of chronic HIV disease progression to AIDS and death in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study than CD4+ cell count, soluble immune activation markers, or combinations of HLA-DR and CD38 expression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;16:83–92. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199710010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giorgi JV, Detels R. T-cell subset alterations in HIV-infected homosexual men: NIAID Multicenter AIDS cohort study. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;52:10–18. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(89)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buggert M, Frederiksen J, Noyan K, Svard J, Barqasho B, Sonnerborg A, Lund O, Nowak P, Karlsson AC. Multiparametric bioinformatics distinguish the CD4/CD8 ratio as a suitable laboratory predictor of combined T cell pathogenesis in HIV infection. J Immunol. 2014;192:2099–2108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klatt NR, Chomont N, Douek DC, Deeks SG. Immune activation and HIV persistence: implications for curative approaches to HIV infection. Immunol Rev. 2013;254:326–342. doi: 10.1111/imr.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatano H, Jain V, Hunt PW, Lee TH, Sinclair E, Do TD, Hoh R, Martin JN, McCune JM, Hecht F, Busch MP, Deeks SG. Cell-based measures of viral persistence are associated with immune activation and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)-expressing CD4+ T cells. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:50–56. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng L, Taiwo B, Gandhi RT, Hunt PW, Collier AC, Flexner C, Bosch RJ. Factors associated with CD8+ T-cell activation in HIV-1-infected patients on long-term antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:153–160. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eller MA, Opollo MS, Liu M, Redd AD, Eller LA, Kityo C, Kayiwa J, Laeyendecker O, Wawer MJ, Milazzo M, Kiwanuka N, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Sewankambo NK, Quinn TC, Michael NL, Wabwire-Mangen F, Sandberg JK, Robb ML. HIV Type 1 Disease Progression to AIDS and Death in a Rural Ugandan Cohort Is Primarily Dependent on Viral Load Despite Variable Subtype and T-Cell Immune Activation Levels. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eller MA, Blom KG, Gonzalez VD, Eller LA, Naluyima P, Laeyendecker O, Quinn TC, Kiwanuka N, Serwadda D, Sewankambo NK, Tasseneetrithep B, Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Marovich MA, Michael NL, de Souza MS, Wabwire-Mangen F, Robb ML, Currier JR, Sandberg JK. Innate and adaptive immune responses both contribute to pathological CD4 T cell activation in HIV-1 infected Ugandans. PloS one. 2011;6:e18779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantaleo G, Fauci AS. Apoptosis in HIV infection. Nat Med. 1995;1:118–120. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finkel TH, Tudor-Williams G, Banda NK, Cotton MF, Curiel T, Monks C, Baba TW, Ruprecht RM, Kupfer A. Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat Med. 1995;1:129–134. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meythaler M, Martinot A, Wang Z, Pryputniewicz S, Kasheta M, Ling B, Marx PA, O’Neil S, Kaur A. Differential CD4+ T-lymphocyte apoptosis and bystander T-cell activation in rhesus macaques and sooty mangabeys during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:572–583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meythaler M, Pryputniewicz S, Kaur A. Kinetics of T lymphocyte apoptosis and the cellular immune response in SIVmac239-infected rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol. 2008;37(Suppl 2):33–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitrak DL, Novak RM, Estes R, Tschampa J, Abaya CD, Martinson J, Bradley K, Tenorio AR, Landay AL. Apoptosis Pathways in HIV-1-Infected Patients Before and After Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: Relevance to Immune Recovery. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014 doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groener JB, Seybold U, Vollbrecht T, Bogner JR. Short communication: decrease in mitochondrial transmembrane potential in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HIV-uninfected subjects undergoing HIV postexposure prophylaxis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:969–972. doi: 10.1089/AID.2010.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hofer U, Schlaepfer E, Baenziger S, Nischang M, Regenass S, Schwendener R, Kempf W, Nadal D, Speck RF. Inadequate clearance of translocated bacterial products in HIV-infected humanized mice. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1000867. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curlin ME, Zioni R, Hawes SE, Liu Y, Deng W, Gottlieb GS, Zhu T, Mullins JI. HIV-1 envelope subregion length variation during disease progression. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1001228. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shankarappa R, Margolick JB, Gange SJ, Rodrigo AG, Upchurch D, Farzadegan H, Gupta P, Rinaldo CR, Learn GH, He X, Huang XL, Mullins JI. Consistent viral evolutionary changes associated with the progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1999;73:10489–10502. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10489-10502.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shankarappa R, Gupta P, Learn GH, Jr, Rodrigo AG, Rinaldo CR, Jr, Gorry MC, Mullins JI, Nara PL, Ehrlich GD. Evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope sequences in infected individuals with differing disease progression profiles. Virology. 1998;241:251–259. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wade J, Sterjovski J, Gray L, Roche M, Chiavaroli L, Ellett A, Jakobsen MR, Cowley D, da Pereira FC, Saksena N, Wang B, Purcell DF, Karlsson I, Fenyo EM, Churchill M, Gorry PR. Enhanced CD4+ cellular apoptosis by CCR5-restricted HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein variants from patients with progressive HIV-1 infection. Virology. 2010;396:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etemad-Moghadam B, Rhone D, Steenbeke T, Sun Y, Manola J, Gelman R, Fanton JW, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Axthelm MK, Letvin NL, Sodroski J. Understanding the basis of CD4(+) T-cell depletion in macaques infected by a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. Vaccine. 2002;20:1934–1937. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Etemad-Moghadam B, Rhone D, Steenbeke T, Sun Y, Manola J, Gelman R, Fanton JW, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Axthelm MK, Letvin NL, Sodroski J. Membrane-fusing capacity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope proteins determines the efficiency of CD+ T-cell depletion in macaques infected by a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2001;75:5646–5655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5646-5655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Etemad-Moghadam B, Sun Y, Nicholson EK, Fernandes M, Liou K, Gomila R, Lee J, Sodroski J. Envelope glycoprotein determinants of increased fusogenicity in a pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-KB9) passaged in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4433-4440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biard-Piechaczyk M, Robert-Hebmann V, Roland J, Coudronniere N, Devaux C. Role of CXCR4 in HIV-1-induced apoptosis of cells with a CD4+, CXCR4+ phenotype. Immunol Lett. 1999;70:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(99)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Troyer RM, Collins KR, Abraha A, Fraundorf E, Moore DM, Krizan RW, Toossi Z, Colebunders RL, Jensen MA, Mullins JI, Vanham G, Arts EJ. Changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fitness and genetic diversity during disease progression. J Virol. 2005;79:9006–9018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9006-9018.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meissner EG, Duus KM, Gao F, Yu XF, Su L. Characterization of a thymus-tropic HIV-1 isolate from a rapid progressor: role of the envelope. Virology. 2004;328:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gougeon ML, Lecoeur H, Dulioust A, Enouf MG, Crouvoiser M, Goujard C, Debord T, Montagnier L. Programmed cell death in peripheral lymphocytes from HIV-infected persons: increased susceptibility to apoptosis of CD4 and CD8 T cells correlates with lymphocyte activation and with disease progression. J Immunol. 1996;156:3509–3520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grivel JC, Malkevitch N, Margolis L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 induces apoptosis in CD4(+) but not in CD8(+) T cells in ex vivo-infected human lymphoid tissue. J Virol. 2000;74:8077–8084. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8077-8084.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doitsh G, Galloway NL, Geng X, Yang Z, Monroe KM, Zepeda O, Hunt PW, Hatano H, Sowinski S, Munoz-Arias I, Greene WC. Cell death by pyroptosis drives CD4 T-cell depletion in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 2014;505:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature12940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doitsh G, Cavrois M, Lassen KG, Zepeda O, Yang Z, Santiago ML, Hebbeler AM, Greene WC. Abortive HIV infection mediates CD4 T cell depletion and inflammation in human lymphoid tissue. Cell. 2010;143:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galloway NL, Doitsh G, Monroe KM, Yang Z, Munoz-Arias I, Levy DN, Greene WC. Cell-to-Cell Transmission of HIV-1 Is Required to Trigger Pyroptotic Death of Lymphoid-Tissue-Derived CD4 T Cells. Cell reports. 2015;12:1555–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Q, Estes JD, Duan L, Jessurun J, Pambuccian S, Forster C, Wietgrefe S, Zupancic M, Schacker T, Reilly C, Carlis JV, Haase AT. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced intestinal cell apoptosis is the underlying mechanism of the regenerative enteropathy of early infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:420–429. doi: 10.1086/525046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, Ma ZM, Rourke T, Wang Y, Reilly C, Carlis J, Miller CJ, Haase AT. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;434:1148–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cockerham LR, Siliciano JD, Sinclair E, O’Doherty U, Palmer S, Yukl SA, Strain MC, Chomont N, Hecht FM, Siliciano RF, Richman DD, Deeks SG. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation are associated with HIV DNA in resting CD4+ T cells. PloS one. 2014;9:e110731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bao R, Zhuang K, Liu J, Wu J, Li J, Wang X, Ho WZ. Lipopolysaccharide induces immune activation and SIV replication in rhesus macaques of Chinese origin. PloS one. 2014;9:e98636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shaw JM, Hunt PW, Critchfield JW, McConnell DH, Garcia JC, Pollard RB, Somsouk M, Deeks SG, Shacklett BL. Increased frequency of regulatory T cells accompanies increased immune activation in rectal mucosae of HIV-positive noncontrollers. J Virol. 2011;85:11422–11434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05608-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaw JM, Hunt PW, Critchfield JW, McConnell DH, Garcia JC, Pollard RB, Somsouk M, Deeks SG, Shacklett BL. Short communication: HIV+ viremic slow progressors maintain low regulatory T cell numbers in rectal mucosa but exhibit high T cell activation. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:172–177. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klatt NR, Bosinger SE, Peck M, Richert-Spuhler LE, Heigele A, Gile JP, Patel N, Taaffe J, Julg B, Camerini D, Torti C, Martin JN, Deeks SG, Sinclair E, Hecht FM, Lederman MM, Paiardini M, Kirchhoff F, Brenchley JM, Hunt PW, Silvestri G. Limited HIV infection of central memory and stem cell memory CD4+ T cells is associated with lack of progression in viremic individuals. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004345. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heigele A, Camerini D, van’t Wout AB, Kirchhoff F. Viremic long-term nonprogressive HIV-1 infection is not associated with abnormalities in known Nef functions. Retrovirology. 2014;11:13. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carrington M, Dean M, Martin MP, O’Brien SJ. Genetics of HIV-1 infection: chemokine receptor CCR5 polymorphism and its consequences. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1939–1945. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley GA, Smith MW, Allikmets R, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder SP, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O’Brien SJ. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, ALIVE Study. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kristoff J, Haret-Richter G, Ma D, Ribeiro RM, Xu C, Cornell E, Stock JL, He T, Mobley AD, Ross S, Trichel A, Wilson C, Tracy R, Landay A, Apetrei C, Pandrea I. Early microbial translocation blockade reduces SIV-mediated inflammation and viral replication. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2802–2806. doi: 10.1172/JCI75090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paiardini M, Cervasi B, Reyes-Aviles E, Micci L, Ortiz AM, Chahroudi A, Vinton C, Gordon SN, Bosinger SE, Francella N, Hallberg PL, Cramer E, Schlub T, Chan ML, Riddick NE, Collman RG, Apetrei C, Pandrea I, Else J, Munch J, Kirchhoff F, Davenport MP, Brenchley JM, Silvestri G. Low levels of SIV infection in sooty mangabey central memory CD(4)(+) T cells are associated with limited CCR5 expression. Nat Med. 2011;17:830–836. doi: 10.1038/nm.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pandrea I, Apetrei C, Gordon S, Barbercheck J, Dufour J, Bohm R, Sumpter B, Roques P, Marx PA, Hirsch VM, Kaur A, Lackner AA, Veazey RS, Silvestri G. Paucity of CD4+CCR5+ T cells is a typical feature of natural SIV hosts. Blood. 2007;109:1069–1076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murray SM, Down CM, Boulware DR, Stauffer WM, Cavert WP, Schacker TW, Brenchley JM, Douek DC. Reduction of immune activation with chloroquine therapy during chronic HIV infection. J Virol. 2010;84:12082–12086. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01466-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paton NI, Goodall RL, Dunn DT, Franzen S, Collaco-Moraes Y, Gazzard BG, Williams IG, Fisher MJ, Winston A, Fox J, Orkin C, Herieka EA, Ainsworth JG, Post FA, Wansbrough-Jones M, Kelleher P. Effects of hydroxychloroquine on immune activation and disease progression among HIV-infected patients not receiving antiretroviral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;308:353–361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vaccari M, Fenizia C, Ma ZM, Hryniewicz A, Boasso A, Doster MN, Miller CJ, Lindegardh N, Tarning J, Landay AL, Shearer GM, Franchini G. Transient increase of interferon-stimulated genes and no clinical benefit by chloroquine treatment during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection of macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30:355–362. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.