Abstract

Measurement of antigen-specific T follicular helper (TFH) cell activity in rhesus macaques has not previously been reported. Given that rhesus macaques are the animal model of choice for evaluating protective efficacy of HIV/SIV vaccine candidates and that TFH cells play a pivotal role in aiding B cell maturation, quantifying vaccine-induction of HIV/SIV-specific TFH cells would greatly benefit vaccine-development. Here we quantified SIV Env-specific IL-21-producing TFH cells for the first time in a non-human primate vaccine study. Macaques were primed twice mucosally with Adenovirus 5 host range mutant (Ad5hr) recombinants encoding SIV Env, Rev, Gag and Nef followed by two intramuscular boosts with monomeric SIV gp120 or oligomeric SIV gp140 proteins. Two weeks after the second protein boost we obtained lymph node biopsies and quantified the frequency of total and SIV Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells and total germinal center (GC) B cells, the size and number of GCs, and the frequency of SIV-specific antibody secreting cells in B cell zones. Multiple correlation analyses established the importance of TFH for development of B cell responses in systemic and mucosally localized compartments including blood, bone marrow, and rectum. Our results suggest that the SIV-specific TFH cells, initially induced by replicating Ad-recombinant priming, are long-lived. The multiple correlations of SIV Env-specific TFH cells with systemic and mucosal SIV-specific B cell responses indicate that this cell population should be further investigated in HIV vaccine development as a novel correlate of immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the fact that protective immunity involves the coordinated work of humoral and cellular mechanisms, most functional vaccines available today prevent pathogen acquisition through the induction of antibodies (1, 2). During HIV infection a small fraction of individuals produce broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which possess potent cross-clade neutralizing activity, widely considered a necessary component of a protective HIV vaccine (3, 4). A common characteristic of bNAbs is their high degree of somatic hypermutation (5), which typically results from extensive affinity maturation and antigen-specific interaction with T follicular helper (TFH) cells within the germinal centers (GC) of secondary lymphoid organs (6, 7).

TFH cells are a highly specialized CD4+ T cell subset that provides help to B cells by contact-dependent and independent mechanisms. Phenotypically, human CD4+ TFH cells are characterized by expression of CXCR5, PD-1, CD95, ICOS, and the transcription factor Bcl-6, which mediates their lineage development (8, 9). Although TFH cells can arise from multiple precursor T helper cell lineages (10-13), their generation is strongly dependent on IL-21, IL-6 and Bcl-6 (14, 15). Localized within immune-protected B cell follicular areas of secondary lymphoid organs, TFH cells have been identified as the major CD4+ T cell compartment for HIV and SIV persistence during chronic infection even under elite controlling conditions (16-20). Nonetheless, TFH cells increase in both HIV (21, 22) and SIV (23, 24) infection in association with GC expansion (25). Indeed, TFH dynamics display multiple adverse effects attributed to infection (25).

Rhesus macaques are the animal model of choice for evaluating pre-clinical HIV/SIV vaccine candidates (26). Although several studies have phenotypically and functionally characterized the total population of macaque TFH cells in naïve and SIV-infected animals (23, 27-31), quantification of vaccine-induced SIV-specific IL-21-producing macaque TFH cells has not yet been reported. In order to better understand the development of humoral immune responses and the contribution of TFH to protective efficacy, in the present study we have identified and quantified SIV-specific LN-resident IL-21+ TFH cells for the first time in a pre-clinical non-human primate vaccine trial. Rhesus macaques were initially vaccinated with mucosally-delivered replicating Adenovirus type 5 host-range mutant (Ad5hr)-recombinants expressing SIV Env, Rev, Gag and Nef proteins followed by intramuscular boosting with either monomeric SIV gp120 or oligomeric SIV gp140 proteins as detailed in a previous study (32). At the end of the vaccination regimen LNs were collected and stored. We measured the frequency of SIV-specific IL-21-producing TFH cells in the LNs together with GC B cells. The results correlated with multiple systemic and mucosal humoral immune responses. Subsequently we analyzed the data with regard to the challenge outcome of the vaccine study, which showed a sex bias in protective efficacy. Namely, the vaccinated female but not male macaques exhibited delayed SIV acquisition associated with vaccine-induced mucosal B cell responses (32). Here we report that the vaccine regimen elicited SIV-specific TFH cells, critically important for development of B cell immunity, and initially induced by the replicating Ad5hr-SIV-recombinant priming immunizations. Furthermore, elevated TFH levels were observed in vaccinated females compared to males. Together with correlations obtained in females between TFH cells and some B cell responses, our data support continued investigation of a potential contribution of TFH cells to sex-based differences in vaccine-induced immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, immunization regimen and sample collection

The rhesus macaques used in this study were housed and cared for at Advanced Bioscience Laboratories, Inc. (Rockville, MD) and at Bioqual, Inc. (Rockville, MD) under the guidelines of the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and according to the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Prior to initiation, all protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the respective facility. Initially, to develop a protocol for identification of LN-resident TFH cells (Fig. 1), viably frozen LN cells obtained from inguinal LN biopsies from naïve (n=10) and chronically SIV-infected (n=10) Indian rhesus macaques (33) were used. Subsequently, vaccine-induced SIV-specific TFH cell function was evaluated in LN biopsies obtained from sixty Indian rhesus macaques vaccinated as previously reported (32) and outlined in Table 1. Antibody and B cell responses used in correlation analyses were also previously reported in the same publication (32). Inguinal LN biopsies were collected from the vaccinated macaques prior to immunization and at week 53 (2 weeks following the second Env protein boost), minced and passed through a 40-μm cell strainer before contaminating RBCs were lysed. Cells were washed and resuspended in R10 medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate and antibiotics). Cells were used fresh for the determination of total and SIV-specific TFH cell populations and remaining cells were viably frozen (FBS + 10% DMSO) for later GC B cell assays. Additional LN biopsies from a subset of macaques (12 from gp120-immunized, 12 from gp140-immunized and 6 from control macaques) were fixed in SafeFix II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and embedded in paraffin for later sectioning and analysis.

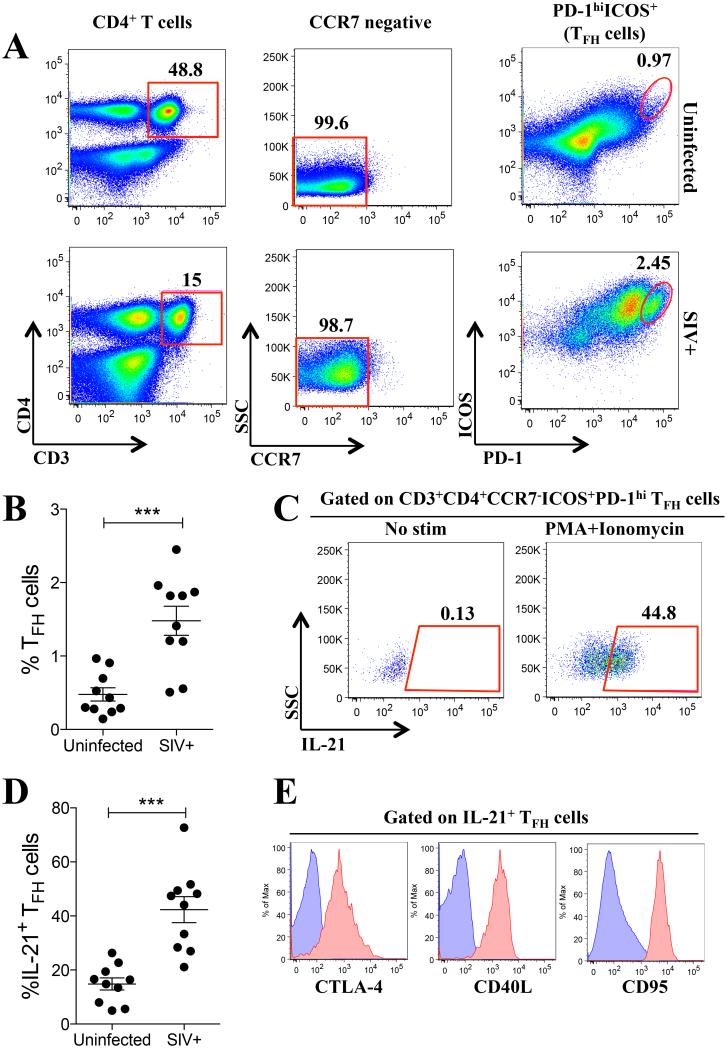

Fig. 1. Phenotypic characterization of macaque IL-21-producing TFH cells.

Inguinal lymph nodes (LN) were collected, processed into single-cell suspensions, and used fresh for flow cytometry phenotypic analysis. (A) Gating strategy used to define LN-resident TFH cells as live CD3+CD4+CCR7−ICOS+PD-1hi in naïve (top) and SIV-infected (bottom) rhesus macaques. (B) Percentage of TFH cells in naïve and SIV-infected macaques. (C) IL-21 production by TFH cells in response to PMA/Ionomycin treatment. (D) Percent of IL-21-producing TFH cells in naïve and SIV-infected macaques. (E) CTLA-4, CD40L and CD95 expression in IL-21+ TFH cells (red histograms) compared to non-TFH cells (naïve CD4+ T cells, blue histograms). Data reported are means ± SEM. ***, p<0.001 indicates statistically significant differences between the compared groups by the Mann-Whitney test.

Table 1.

Summary of immunization regimen of macaques used in this study.

| Immunization group |

Week 0 | Week 12 | Week 39 | Week 51 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gp120 group (n = 24) |

Ad5hr-SIV recombinants* (IN + O) |

Ad5hr-SIV recombinants (IT) |

Monomeric SIV gp120 in MF59 (IM) |

Monomeric SIV gp120 in MF59 (IM) |

| gp140 group (n = 24) |

Ad5hr-SIV recombinants (IN + O) |

Ad5hr-SIV recombinants (IT) |

Oligomeric SIV gp140 in MF59 (IM) |

Oligomeric SIV gp140 in MF59 (IM) |

| Controls (n = 12) |

Ad5hr empty vector (IN + O) |

Ad5hr empty vector (IT) |

MF59 only (IM) | MF59 only (IM) |

Three Ad5hr-SIV recombinants separately encoding SIVsmH4 env(gp140)/rev; SIVmac239 gag; and SIVmac239 nefΔ1-13 were administered by the indicated routes at 5× 108 pfu/recombinant/route. The control macaques received a total dose of 1.5 × 109 pfu/route of the empty Ad vector. SIVmac239 Env proteins were given at a dose of 100 ug. IN = intranasal; O = oral; IT = intratracheal; IM = intramuscular.

Detection of GCs and TFH cells in fixed LNs

GCs and GC-resident TFH cells were detected using immunofluorescence staining. Briefly, 6-μm sections were cut and adhered to silanized slides and stained with the following antibodies: mouse anti-human CD4 (1F6, Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL), goat anti-human PD-1 (AF1086, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), or goat anti-human CD20 (MS4A1, Origene, Rockville, MD) and rabbit anti-human Ki67 (SP6, ThermoFisher Scientific). Sections on slides were pretreated in 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) in a Presto pressure cooker (National Presto Industries, Eau Claire, WI) at 121°C for 35 seconds to unmask antigens. Sections were blocked with normal horse serum, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing in PBS, the slides were incubated at room temperature for 2 h with donkey AlexaFluor 647 anti-mouse IgG, AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG and AlexaFluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG and counterstained with DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), all from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). After washing in PBS, the slides were coverslipped and examined using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope system (Nikon, Melville, NY). GCs were enumerated and size quantified using ScanScope slide scanner and ImageScope software (Aperio-Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Quantification of GC-resident TFH cells in fixed LNs

Expression levels were extracted from confocal images by first using the interactive segmentation software ilastik (v. 1.1.5) to separate cells from the background based on features defined by color/intensity, edges, and texture in all image channels (34). Although the ilastik segmentation efficiently delineated cells from the image background, groups of cells were not adequately separated from each other. Therefore, the segmentation mask, along with the raw confocal images was imported into custom software written in MATLAB (R2015a, Mathworks, Natick, MA), with use of the image processing toolbox. The custom software performed morphological erosion on the segmentation mask to isolate individual cells, which were then each given a unique identification number, and then returned to their original size by use of morphological dilation. Fluorescence levels in each confocal channel were then calculated for the individual cells by summing the pixel intensities within each cell boundary, and dividing by the number of pixels.

Detection of SIV-specific B cells in fixed LNs by inverse immunohistochemistry

SIV-specific B cells were detected in safe fixed tissues using biotin conjugated SIV gp120 or gp140 and inverse immunohistochemical staining. Briefly, sections on slides were pretreated in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) in a waterbath (National Presto Industries, Eau Claire, WI) at 98°C for 15 minutes to unmask antigens. Endogenous biotin was blocked using Dako Biotin Blocking System (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Biotin-SIV gp120 or gp140 was added to sections and allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed with TBS (pH 8.0), and allowed to incubate with streptavidin-HRP for 1 hr at room temperature and washed with TBS (pH 8.0). Signal was amplified using a Tyramide (TSA) Biotin amplification system following the manufacturer’s instructions (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Flow cytometric detection of TFH cells

Anti-human fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs known to cross-react with rhesus macaque antigens were used in this study, including PE anti-IL-21 (3A3-N2.1), PE-CF594 anti-CD95 (DX2), PE-Cy5 anti-CD154 (TRAP1), APC anti-CD152 (BNI3) and Alexa Fluor 700 anti-CD3 (SP34-2) (all from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); PerCP-eFluor710 anti-CD279 (eBioJ105) and APC-eFluor780 anti-CD197 (3D12) (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA); PE-Cy7 anti-IL-17A (BL168) and Pacific Blue anti-CD278 (C398.4A) (BioLegend, San Diego, CA); and QDot605 anti-CD4 (T4/19Thy5D7) (NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource, Boston, MA). The Yellow LIVE/DEAD viability dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to exclude dead cells. At least 500,000 singlet events were acquired on a SORP LSRII (BD Biosciences and analyzed using FlowJo Software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR). For all samples gating was established using a combination of isotype and fluorescence-minus-one controls.

SIV-specific IL-21-producing TFH cell detection

SIV-specific production of IL-21 by LN-resident TFH cells was assayed by stimulating 2 × 106 LN cells with 1 μg/ml SIVmac239 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) or SIVsmH4 (Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Inc., Rockville, MD) Env peptide pools (complete sets of 15-mer peptides, overlapping by 11aa) for 6 h. Stimulation was performed in the presence of 2 μg/ml anti-CD49d and anti-CD28 (BD Biosciences), BD Golgi Plug, BD Golgi Stop, and APC-eFluor780 anti-CD197 at the manufacturer’s recommended concentrations. Subsequently, cells were washed and surface stained before fixation and permeabilization with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm and intracellular staining. Stimulation with PMA plus Ionomicyn was used to elicit IL-21 production by TFH cells.

Detection of GC B cells by flow cytometry

Frozen LN cells were thawed, washed in PBS, and 2x106 cells stained with Aqua LIVE/DEAD viability dye (Invitrogen). Surface staining was performed in PBS/0.5% BSA/2mMEDTA with the following fluorochrome-conjugated Abs known to cross-react with rhesus macaque antigens: Qdot605 anti-CD14 (Tuk4) and anti-CD2 (S5.5) (Invitrogen); eFL650NC anti-CD20 (2H7) (eBioscience); PECy5 anti-CD19 (J3-119) (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA); and Texas Red goat polyclonal anti-IgD (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Intra-nuclear staining for Alexa Fluor 700 anti-Ki67 (B56) and Alexa Fluor 647 anti-Bcl6 was performed using the Transcription Factor Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (all reagents from BD Biosciences). At least 250,000 singlet events were acquired on a LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo Software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR). Gating was established using a combination of isotype and fluorescence-minus-one controls.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed as described in figure legends using Prism (v6.01, GraphPad Software). A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of IL-21-producing LN resident TFH cells and their correlation with vaccination-induced humoral immune responses

At the time of experimentation the only rhesus macaque anti-CXCR5 antibody available was from the NIH Non-human Primate Reagent Resource; however, this antibody does not specifically label rhesus TFH cells (23, 24). Therefore we used other available phenotypic markers to identify rhesus macaque LN-resident TFH cells. Initially, LN from naïve and chronically SIV-infected macaques were used to identify the total population of LN-resident TFH cells as live CD3+CD4+CCR7−ICOS+PD-1hi cells (Fig. 1A), hereafter termed total TFH cells. These cells represented ~0.5% of the total LN-resident CCR7−CD4+ T cell pool present in naïve animals and their proportion was increased approximately 3-fold in chronically SIV-infected macaques (p < 0.001; Fig. 1B). Within the LN TFH cell population from naïve macaques, approximately 15% were capable of producing IL-21 in response to PMA plus ionomycin stimulation (Fig. 1C, D). Similarly, the proportion of IL-21 producing cells was increased approximately 3-fold in chronically SIV-infected macaques when compared to naïve animals (p < 0.001; Fig. 1D). The IL-21 producing TFH cells were IL-17 negative (data not shown), and the majority expressed CTLA-4, CD40L and CD95, a further indication that the IL-21-producing cells were indeed TFH cells (Fig. 1E). Given that no rhesus macaque cross-reacting anti-CXCR5 antibody was available at the time of this study, our phenotypic identification of total TFH cells may have included some CXCR5−/lo pre-TFH cells (35).

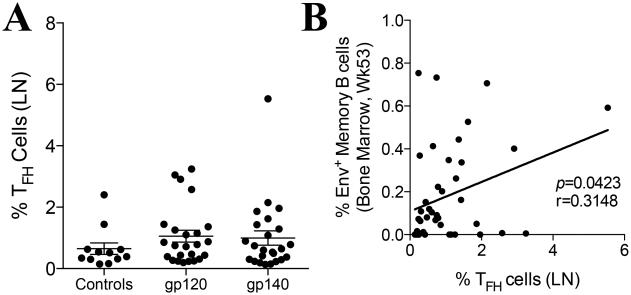

Following phenotypic and functional identification of macaque TFH cells in LN of naïve and SIV-infected animals, we proceeded to measure the frequency of these cells after priming with Ad5hr-SIV recombinants and boosting with monomeric gp120 (gp120 Group) or oligomeric gp140 (gp140 Group) SIV Env proteins (Table 1). Inguinal LN biopsies were taken at week 53, two weeks after the second intramuscular protein immunization, and processed to quantify total TFH cells. No significant increases in the abundance of these cells were seen in the vaccinated groups compared to the controls (Fig. 2A). This is not surprising as the total population of LN-resident TFH cells includes cells of many different antigenic specificities. Moreover, the controls received empty Ad vector and adjuvant, only differing from the vaccinated groups in the SIV transgenes and Env protein immunogens (Table 1). Nonetheless, the percentage of LN-resident TFH cells present in all vaccinated macaques had a significant positive correlation with the percentage of SIV Env-specific memory B cells in the bone marrow at week 53 (Fig. 2B), highlighting the role of TFH cells in driving B cell responses.

Fig. 2. Correlation between humoral responses and TFH cell abundance in vaccinated rhesus macaques.

(A) Percentage of TFH cells in the inguinal LN of vaccinated and control macaques at week 53 of the study. Data reported are means ± SEM. (B) Correlation between abundance of total LN TFH cells at week 53 and SIV Env-specific memory B cells in the bone marrow at week 53 in vaccinated macaques. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine statistical significance. Env-specific memory B cell data are from ref. 32.

Effects of vaccination on GC and TFH cells

After initial pre-GC interactions, TFH are known to bind B cells within the GC regions of secondary lymphoid organs and selectively reinforce a program of proliferation and somatic hypermutation. To more directly assess the role of TFH within GCs, we measured GC (CD20+Ki67+) areas and quantified the number of GC-resident TFH cells (CD4+PD-1hi within Ki67+ areas) in vaccinated rhesus macaques by immunofluorescence. Although ICOS expression was not used to identify GC-resident TFH cells by confocal microscopy, the use of CD4 and PD-1 markers in Ki67 rich areas has previously been described as a valid approach to identify LN-resident TFH cells (23, 24). LN tissue sections were collected at week 53 and stained for Ki67, CD20 and CD4 to enumerate and measure GCs (Fig. 3A), and with CD4, PD-1 and Ki67 to enumerate TFH cells within GCs (Fig. 3B). No significant differences were observed in the number (Fig. 3C) or area (Fig. 3D) of GCs between vaccinated and control macaques. Additionally, a software-based approach was used to enumerate TFH cells (CD4+PD-1hi cells) within Ki67 rich GC areas (Fig. 3E). As shown in Fig. 3F, no significant differences were observed in the abundance of GC-resident TFH cells between vaccinated and control macaques. These results are again consistent with the fact that both control and vaccinated macaques received equivalent doses of the Ad vector and MF59 adjuvant (Table 1) as discussed above.

Fig. 3. Effect of vaccination on GC size and TFH cell number.

(A-F) LN biopsies from a subset of vaccinated macaques were collected at week 53 and fixed in 10% formalin prior to paraffin embedding. (A-B) Tissue sections were recovered and stained specifically with Ki67, CD20 and CD4 to identify and measure the size of GCs (A), and with CD4, PD-1 and Ki67 to identify and enumerate GC-resident TFH cells (B). Bars represent 100 and 50μm in A and B, respectively. (C-D) The number of GCs (C) and the average GC area per animal (D) were measured in LN sections as displayed in A with Aperio ImageScope Quantification Software. (E-F) Confocal images of LN sections stained as in B were analyzed as described in Materials and Methods to determine PD-1 and CD4 expression intensity levels on an individual cell basis. Gates (red line) were drawn to enumerate TFH (PD-1hiCD4+) cells per GC (E) and to compare between vaccinated and control macaques (F). Data reported are means ± SEM

Within GCs, B cells may cycle through multiple rounds of antigen-specific selection, proliferation, and somatic hypermuation before exiting the GC as memory B cells or plasma cells (PC). GC B cells are classified either as centrocytes, which compete for TFH binding in the light zone or positively-selected, proliferating centroblasts which reside in the dark zone (36, 37). We measured the abundance of total GC-resident B cells in the LN of control and vaccinated macaques. Fig. 4A shows the gating strategy used to identify total GC B cells (IgD−CD20+Bcl6+), as well as dark zone centroblasts (IgD−CD20+Bcl6+Ki67hi) and light zone centrocytes (IgD−CD20+Bcl6+Ki67neg/lo) by flow cytometry. The gate for centrocytes includes both Ki67− and Ki67lo cells because as depicted in Figure 3A, the light zone likely accommodates both newly-arrived, Ki67− cells as well B cells recently returned from the dark zone, expressing low levels of Ki67. As was noted for TFH cells, no significant increase in the frequency of total GC B cells (Fig. 4B) or in the centroblast (Fig. 4C) and centrocyte (4D) subpopulations was observed in vaccinated macaques compared to controls.

Fig. 4. Effect of vaccination on GC-resident B cell subpopulations.

(A-D) Frozen inguinal lymph node cells from controls and vaccinated macaques were thawed and stained (A) in order to identify the absolute population of IgD−CD20+Bcl6+ GC cells (B), IgD−CD20+Bcl6+Ki67hi centroblasts (C) and IgD−CD20+Bcl6+Ki67neg/lo centrocytes (D) by flow cytometry. Data reported are means ± SEM.

Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 5A, we detected a positive correlation in vaccinated macaques between the numbers of GCs after the last immunization (Fig. 3C) and the abundance of total TFH cells detected by flow cytometry. Similarly, the number of GCs in vaccinated macaques at week 53 also correlated positively with SIVgp140- and SIVgp120-specific binding titers in serum at week 57 (Fig. 5B) and with the Env-specific IgA secreting plasma cells in the bone marrow at week 53 (Fig. 5C). Although vaccination did not induce a significant increase in the number of GCs or in the number of GC-resident TFH cells compared to controls (Figs. 3C and 3F), we did observe a direct correlation between the number of GC-resident TFH cells and the number (Fig. 5D) and area (Fig.5E) of GCs in the LN. Moreover, the number of GC-resident TFH cells as determined by histological analysis significantly correlated with the abundance of total TFH cells as determined by flow cytometry at week 53 in vaccinated rhesus macaques (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5. Correlations between GC parameters and GC B cells with humoral immune responses and total TFH cells.

Correlations in vaccinated macaques between the number of histologically-determined GCs in the LN at week 53 and the abundance of flow cytometry-determined absolute TFH cells at week 53 (A), SIV-specific gp120 and gp140 serum binding titers at week 57 (B) and SIV Env-specific IgA activity in bone marrow at week 53 (C). Correlations between the number of histologically-determined TFH cells per GC at week 53 and the number of GCs per LN (D), the average GC area (E), and the abundance of TFH cells as determined by flow cytometry (F). (G-H) Correlation analyses of the abundance of flow cytometry-determined TFH cells and the abundance of IgD−CD20+Bcl6+ GC B cells (G) and IgD−CD20+Bcl6+Ki67hi GC centroblasts (H) at week 53. Note, histologically-determined GC data were obtained on only half of the vaccinated and control macaques as described in Materials and Methods. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine statistical significance. Humoral immune response data are from ref. 32.

Further validating the role TFH cells play in helping B cell responses, a significant correlation was observed between total TFH cells and total GC cells (Fig. 5G). Similarly, we observed a significant positive correlation between the abundance of total TFH cells and centroblast B cells in the LN (Fig. 5H). No correlation with centrocyte B cells was observed (data not shown). The correlation with centroblasts may be a reflection of the direct stimulation that occurs between GC B cells and TFH cells which results in their movement to the dark zone and subsequent proliferation as centroblasts. In contrast, depending on their affinity and receptor expression level, not all centrocytes will interact productively with TFH cells. Moreover, centrocytes that have successfully completed their transit through the GC cycle will mature and migrate out of the light zone, again leading to a lack of correlation. The dynamics of GC B cells and the influence of TFH cells on GC function are areas in need of further study.

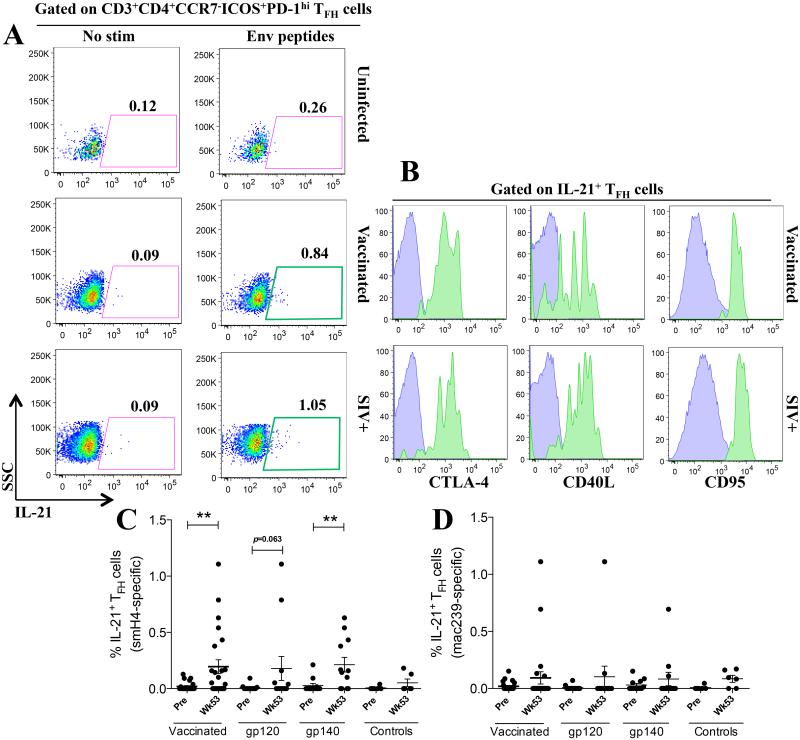

Measurement of SIV-specific IL-21-producing TFH cells

Given that total TFH cells represent a population of cells with many different antigenic specificities, we sought to functionally identify the proportion of TFH cells specific for SIV. We initially evaluated LN cells from chronically SIVmac251-infected animals by stimulating with SIVmac239 Env peptides. Upon stimulation a small subset of the total LN TFH cells produced IL-21 (Fig. 6A). To further identify these cells as SIV Env-specific TFH cells, we confirmed expression of CTLA-4, CD40L and CD95 within the IL-21+ TFH cells (Fig. 6B). To determine the frequency of SIV Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells in the vaccinated macaques we split the animals into two groups. Cells from one group were stimulated with SIVsmH4 Env peptides, matching the SIV Env encoded in the Ad5hr recombinant, and cells of the other with SIVmac239 Env peptides, matching the strain of the Env protein boosts. Interestingly, stimulation with SIVsmH4 Env peptides from the Ad prime elicited significant production of IL-21 by Env-specific LN-resident TFH cells in all vaccinated macaques (Fig. 6C). When macaques were separated based on the boosting immunogen, we observed a marginally non-significant upregulation of SIV-specific IL-21 in gp120-boosted macaques and a significant upregulation of IL-21 production by gp140-immunized macaques (Fig. 6C). It may be that the TFH cells from the gp140-immunized macaques received additional stimulation from the gp41 peptides present in the peptide pool, whereas the gp120-immunized macaques did not. Stimulation with SIVmac239 Env peptides did not induce significant IL-21 production by LN-resident TFH cells in vaccinated macaques (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6. SIV-specific production of IL-21 by TFH cells in vaccinated rhesus macaques.

(A) IL-21 production by LN-resident TFH cells of vaccinated and SIV+ macaques in response to SIV envelope peptide stimulation. (B) CTLA-4, CD40L and CD95 expression by IL-21+ SIV-specific TFH cells. SIVsmH4- (C) and SIVmac239-specific (D) IL-21 production by TFH cells at week 53 post-vaccination. Vaccinated data in C and D include macaques of both vaccination groups. Data reported are means ± SEM. **, p<0.01 indicates statistically significant differences between the indicated time points by the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

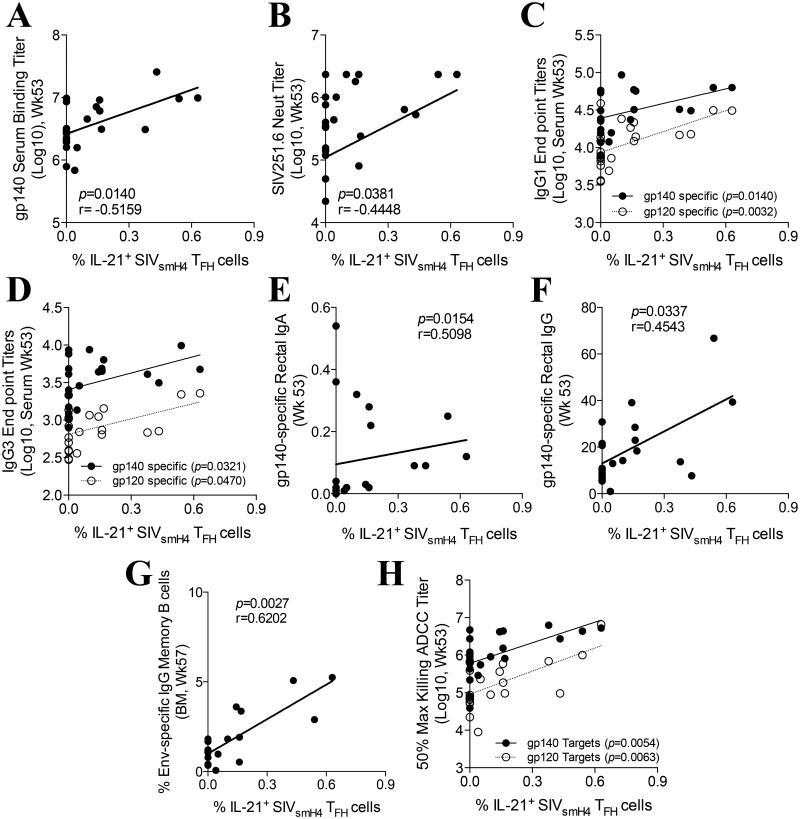

The identification and quantification of SIV Env-specific IL-21+ LN-resident TFH cells of vaccinated macaques subsequently linked the antigen specific process of B cell maturation in GCs with numerous mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses reported previously (32). SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells in all vaccinated animals (boosted either with gp120 or gp140) correlated significantly with the presence of gp140-specific binding antibodies in serum (Fig. 7A) and with the presence of SIV251.6-specific neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 7B) both at week 53. Moreover, both gp120- and gp140-specfic IgG1 and IgG3 binding titers were significantly correlated with SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells (Fig. 7C,D). Further, SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells correlated significantly with SIV gp140-specific IgA (Fig. 7E) and IgG (Fig. 7F) present in rectal secretions at week 53. Finally, SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells were also positively correlated with the presence of Env-specific IgG memory B cells in the bone marrow at week 57 (Fig. 7G) and with serum ADCC activity against SIVgp120- and SIVgp140-coated target cells (Fig. 7H) at week 53.

Fig. 7. Correlation between SIV-specific humoral responses and SIV-specific TFH cell activity.

(A-H) Correlations between SIVsmH4-specific IL-21 production by LN-resident TFH cells at week 53 post-vaccination and SIVgp140-specific week 53 serum binding titers (A), SIV251.6 neutralizing antibodies in serum at week 53 (B), gp140- and gp120-specific IgG1 (C) and IgG3 (D) end point titers measured by ELISA, SIVgp140-specific IgA (E) and IgG (F) antibodies in rectal secretions at week 53 as measured by ELISA, IgG Env-specific memory B cell activity in bone marrow at week 57 as measured by ELISPOT (G) and gp140- and gp120-specific 50% maximum killing ADCC titers as measured by the RFADCC assay (H). Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine statistical significance. Humoral immune response data are from ref. 32.

Evaluation of GC B cells and TFH cells in vaccinated male and female macaques

We previously reported that vaccinated female but not male macaques exhibited delayed SIV acquisition correlated with Env-specific IgA in rectal secretions, rectal Env-specific memory B cells, and total rectal plasma cells (32). This sex bias was most evident in the gp120 group of immunized macaques. Therefore, we asked whether there was a sex bias in vaccine-induced generation of GC B cells and LN-resident TFH cells. No sex differences were observed in the number or area of GC; SIV Env-specific ASC in LN B cell zones; the abundance of total GC B cells, centroblasts or centrocytes; or the number or percentage of TFH per GC (data not shown). However, analyses of total and SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ LN-resident TFH cells revealed differences. Although no differences in pre or post-vaccination (wk 53) levels of total TFH cells were seen when macaques were stratified by sex, at the end of the vaccine regimen (week 53) female macaques exhibited significantly greater proportions of total TFH cells compared to males (Fig. 8A). Further, following vaccination, females exhibited significantly elevated levels of SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells compared to pre-immunization levels whereas males did not (Fig. 8B). However, it is possible that because the vaccinated macaques were divided for stimulation with either SIVsmH4 or SIVmac239 Env peptides, the resulting small number of males available for analysis may have contributed to a lack of significance.

Fig. 8. Total and SIV Env-specific TFH cell responses in female versus male rhesus macaques.

(A) Abundance of total TFH cells before and after vaccination in male and female rhesus macaques. *, p<0.05 indicates statistically significant differences between the indicated groups by the Mann-Whitney test. (B) Vaccine-induced SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells in male and female rhesus macaques. **, p<0.01 and *, p<0.05 indicate statistically significant differences between the indicated time points by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Data reported are means ± SEM. (C-D) Correlations between total TFH cells at week 53 post-vaccination and gp120-specific serum binding titer at week 57 as measured by ELISA (C), and the abundance of rectal plasmablasts 2 weeks post-infection (D) in vaccinated female macaques. Correlation between SIVsmH4-specific IL-21 production by LN-resident TFH cells at week 53 post-vaccination and gp120-specific 50% maximum killing ADCC titers as measured by the RFADCC assay in vaccinated female macaques. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine statistical significance. Humoral immune response data are from ref. 32.

We subsequently conducted further correlation analyses by sex. No correlations were observed with vaccinated male macaques. As shown, in females we observed correlations between total TFH cells and gp120 antibody binding titers (Fig. 8C), as well as with rectal plasmablasts 2 weeks post-infection (Fig. 8D). Note, the correlation with rectal plasmablasts remained significant when apparent outliers were removed (2 outliers removed: r = 0.4825, p = 0.0069; 3 outliers removed, r = 0.4350, p = 0.018). Additionally, a significant correlation between SIVsmH4 Env specific IL-21+ TFH cells and ADCC activity against gp120-coated target cells was obtained. Marginally non-significant correlations were seen between SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells and ADCC activity against gp140-coated target cells (p = 0.061) and neutralizing activity against SIV251.6 (p = 0.054) (data not shown).

Effect of vaccination on SIV-specific B cell responses

Having shown that the proportion of LN TFH cells is directly correlated with the proportion of GC B cells and centroblasts (Fig. 5G-H) and that SIV-specific IL-21+ TFH cells are directly correlated with numerous humoral immune responses, we next examined SIV Env-specific B cells in LN of vaccinated macaques. Using reverse immunohistochemistry we identified and enumerated SIV Env-specific antibody secreting cells (ASC) in B cell areas of LN obtained at week 53. As shown in Fig. 9A, equivalent numbers of SIV Env-specific ASC were observed in SIVgp120 and SIVgp140 boosted macaques. Similarly, no difference was observed in numbers of SIV Env-specific ASC between male and female macaques (data not shown). We were not able to determine if the number of SIV Env-specific ASC correlated with site-specific SIV Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells because the values were obtained from different LN by different techniques (reverse immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry, respectively). Interestingly, however, the abundance of LN-resident SIV Env-specific ASCs inversely correlated with the plasma viral load at week 1 post-infection in vaccinated female but not male macaques (Fig. 9B). As previously reported, the vaccinated macaques in this study modestly controlled acute viremia (32), so such transient control of viremia in the first week following SIV acquisition was not unexpected. This acute control was previously correlated with CD8+ T cell responses in all vaccinated macaques and vaccinated males but not females (32). We speculated that the result in females reflected a waning of the cellular response during their significant delay in SIV acquisition. Here our result suggests that SIV Env-specific ASC may contribute to control of viremia in females, but that SIV specific antibody may similarly exhibit a waning effect due to acquisition delay.

Fig. 9. Histological identification of SIV-specific B cells in the LN of vaccinated macaques.

LN biopsies from a subset of vaccinated macaques were collected at week 53 and fixed in 10% formalin prior to paraffin embedding. (A) Tissue sections were recovered, processed and stained for inverse-IHC using biotin-SIVgp120 or gp140. Images were captured using a ScanScope Slide scanner and analyzed using ImageScope software. Graph represents the number of SIV-specific antibody secreting cells (ASC) per mm2 of LN B cell zone. Data reported are means ± SEM. (B) Correlation between the number of SIV-specific ASC at week 53 and the plasma viral load at week 1 post-infection in female macaques (from ref. 32). Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

A complex and unique mixture of signals, factors and cellular processes are involved in the interaction between TFH cells and B cells within the GC. These contact-dependent and –independent interactions influence B cell survival, proliferation, hypermutation, and immunoglobulin class switching (38). Among these interactions, TFH-derived IL-21 together with CD40L and IL-4 play pivotal roles in regulating B cell activation and maturation (39). Although total TFH cell dynamics have been previously studied in rhesus macaque models of SIV/HIV infection, the quantification of SIV-specific TFH cell activity induced through vaccination has not been previously shown. To examine this question, we took advantage of a pre-clinical vaccine trial (32) in which LN biopsies were obtained prior to vaccination and 2 weeks following the last immunization (wk 53). Although this sampling time point may have missed peak TFH responses, we were nevertheless able to detect and quantify LN-resident vaccination-induced SIV-specific IL-21+ TFH cells. We found that total TFH cells correlated with bone marrow Env-specific memory B cells and with GC B cells, in particular, centroblasts. Further, measurements of SIV Env-specific TFH activity provided correlations with multiple functional systemic and mucosal humoral responses observed at the time of LN biopsy (wk 53) and/or 4 weeks later (wk 57). Thus, vaccine-induced SIV Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells were shown to be directly associated with the development of a variety of vaccine-elicited B cell responses. Future studies using flow cytometry to evaluate both SIV Env-specific TFH and Env-specific GC B cells from the same LN should further support this relationship. Overall, the evaluation of antigen-specific TFH cells can provide insight into vaccine-induced humoral immune responses and further elucidate potential correlates of protective immunity.

Our data suggest that the initial priming immunization used in our vaccination protocol induced a long-lasting SIV-specific TFH response, persisting at least 53 weeks past the first immunization. Whether this response was due to memory TFH or persistent antigen expression is unknown. It is not yet clear whether memory TFH cells are generated within the GC or from non-GC TFH cells, or whether they remain in LNs after GC resolution or exit to the blood (40, 41). It is conceivable that the long-lasting SIV-specific TFH response we observed reflects persistent antigen exposure as opposed to memory since the replication-competent Ad5hr-recombinant priming immunogens we used have been shown to persist at least 25 weeks following administration (42). Further studies are warranted to address these questions. Moreover as all data here were obtained at week 53, a more complete picture of the effects of Ad5hr-recombinant priming and overall kinetics of TFH cell development could be revealed by studying additional, earlier time points. This approach is being pursued in an ongoing pre-clinical vaccine trial. Regardless, it is evident from this study that Ad5hr-SIV recombinant priming induced SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells that contributed to the development of both systemic and mucosal B cell responses.

While antigen-specific TFH cells are beneficial for antibody induction, few studies have explored strategies to enhance development of this cell population. We found that induction of SIVmac239 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells was not as robust following the boosting immunizations compared to the induction following the Ad5hr-recombinant priming. Yet MF59, the adjuvant used for protein boosting in this pre-clinical vaccine study, has been shown to promote GC B cell differentiation and TFH induction (43, 44). It may be that the modest elicitation of SIVmac239 Env-specific compared to the SIVsmH4 Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells reflects a difference between persistent antigen exposure from Ad5hr-SIVenv recombinant and short-term antigen exposure from the Env protein boosts. If so, this highlights the potential benefits of replicating vaccine vectors. In any case, additional adjuvant formulations that can enhance TFH development should be explored. Other approaches directed at TFH cell induction have included nanoparticle vaccines, shown to expand TFH cell populations and promote GC development, leading to enhanced humoral immunity (45). Vaccine strategies incorporating DNA priming have facilitated TFH and GC development along with associated antigen-specific antibody responses compared to immunization with protein alone (46). In view of the strong associations of SIV-specific TFH cells with multiple systemic and mucosal antibody responses seen here, continued exploration of strategies to enhance antigen-specific TFH development through the modulation of vaccine regimens is warranted.

The LN studied here were obtained from macaques that exhibited a clear sex bias in vaccine-induced protective efficacy (32). This outcome was consistent with the known sex differences in the pathogenesis of viral diseases including HIV infection, where women initially control the disease better than men (47). This sex bias has been associated with differences in immune responses. Females have been reported to have better antigen recognition by pattern recognition receptors, enhanced induction of innate and adaptive immune responses, and elevated production of inflammatory cytokines compared to men. They exhibit both greater antigen-specific humoral responses and higher basal immunoglobulin levels (48). Having identified and quantified vaccine-induced SIV Env-specific TFH cells, we asked whether there was a similar sex bias in the induction of these cells, and how these cells might relate to the protective immune responses previously correlated with delayed SIV acquisition in vaccinated females. Initially we noted that females had elevated levels of both total TFH cells and SIVsmH4-Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells compared to males (Fig. 8A,B). The origin of TFH cells is not well defined. Rather than arising from pre-existing TFH cells, they may develop from memory CD4+ T cell populations committed to a TFH lineage (12, 13). Thus the higher level of total TFH cells we observed in female macaques may not have significantly influenced the subsequent development of viral-specific TFH cells; rather it may indicate that females have an enhanced mechanism for generating and maintaining this cell population.

With regard to contributions of TFH cells in females to B cell responses previously associated with delayed acquisition, the correlation of TFH cells with rectal plasmablasts (Fig. 8D) is of interest as mucosal B cell responses were a clear factor in the observed sex bias (32). This correlation is presumably linked to the Ad5hr-recombinant priming immunizations administered to the upper respiratory tract and gut to target mucosal inductive sites resulting in both SIV Env-specific IL-21+ TFH cells and rectal plasmablasts. While here we studied inguinal LNs, future examination of mesenteric LN of similarly vaccinated macaques might help identify additional mucosal immune responses correlated with induction of TFH cells and potentially the female sex bias in protective efficacy.

The previous study also reported that the vaccinated male macaques developed higher antibody titers than the females, yet the females exhibited equivalent antibody-dependent functional activities (32). Thus the correlation here of SIVsmH4 Env-specific TFH in females with gp120-specific ADCC activity (Fig. 8E) and the marginally non-significant correlations with gp140-specific ADCC and neutralizing antibody activities suggest a hypothesis that elevated TFH cell levels compensated for lower antibody titers by promoting better quality antibody in the female macaques. This hypothesis can be pursued by in-depth characterization and functional analyses of the antibodies elicited and further investigation in future pre-clinical studies.

Overall this study illustrates the importance of antigen specific TFH cells for the development of B cell immunity, critical for vaccine-induced protective efficacy. Continued studies are needed to elucidate how best to enhance this population in vaccine protocols. Further, our results suggest that SIV-specific TFH cells should be routinely investigated as a correlate of protective immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the animal caretakers at Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Inc, and Bioqual, Inc. We thank Katherine McKinnon (Vaccine Branch Flow Core, NCI) for expert advice in Flow Cytometry. We thank Christian Elowsky (UNL Microscopy Core) for assistance with confocal microscopy. The following reagent was obtained through the NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource: QDot605 anti-CD4. The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: SIVmac239 Env peptides (complete set).

This study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, and by grant R01 DK087625-01 to QL.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1055–1065. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plotkin SA. Vaccination against the major infectious diseases. C R Acad Sci III. 1999;322:943–951. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(00)87191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein F, Mouquet H, Dosenovic P, Scheid JF, Scharf L, Nussenzweig MC. Antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine development and therapy. Science. 2013;341:1199–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.1241144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGuire AT, Dreyer AM, Carbonetti S, Lippy A, Glenn J, Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Stamatatos L. HIV antibodies. Antigen modification regulates competition of broad and narrow neutralizing HIV antibodies. Science. 2014;346:1380–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.1259206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamatatos L, Morris L, Burton DR, Mascola JR. Neutralizing antibodies generated during natural HIV-1 infection: good news for an HIV-1 vaccine? Nat Med. 2009;15:866–870. doi: 10.1038/nm.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumjohann D, Preite S, Reboldi A, Ronchi F, Ansel KM, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Persistent antigen and germinal center B cells sustain T follicular helper cell responses and phenotype. Immunity. 2013;38:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Tanaka S, Matskevitch TD, Wang YH, Dong C. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. Germinal center B and follicular helper T cells: siblings, cousins or just good friends? Nat Immunol. 2011;12:472–477. doi: 10.1038/ni.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glatman Zaretsky A, Taylor JJ, King IL, Marshall FA, Mohrs M, Pearce EJ. T follicular helper cells differentiate from Th2 cells in response to helminth antigens. J Exp Med. 2009;206:991–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahey LM, Wilson EB, Elsaesser H, Fistonich CD, McGavern DB, Brooks DG. Viral persistence redirects CD4 T cell differentiation toward T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:987–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fairfax KC, Everts B, Amiel E, Smith AM, Schramm G, Haas H, Randolph GJ, Taylor JJ, Pearce EJ. IL-4-Secreting Secondary T Follicular Helper (Tfh) Cells Arise from Memory T Cells, Not Persisting Tfh Cells, through a B Cell-Dependent Mechanism. J Immunol. 2015;194:2999–3010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale JS, Youngblood B, Latner DR, Mohammed AU, Ye L, Akondy RS, Wu T, Iyer SS, Ahmed R. Distinct memory CD4+ T cells with commitment to T follicular helper- and T helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity. 2013;38:805–817. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, Wang YH, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale JS, Ahmed R. Memory T follicular helper CD4 T cells. Front Immunol. 2015;6:16. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukazawa Y, Lum R, Okoye AA, Park H, Matsuda K, Bae JY, Hagen SI, Shoemaker R, Deleage C, Lucero C, Morcock D, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Hirsch VM, Edlefsen PT, Piatak M, Jr., Estes JD, Lifson JD, Picker LJ. B cell follicle sanctuary permits persistent productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in elite controllers. Nat Med. 2015;21:132–139. doi: 10.1038/nm.3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukazawa Y, Park H, Cameron MJ, Lefebvre F, Lum R, Coombes N, Mahyari E, Hagen SI, Bae JY, Reyes MD, 3rd, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Sylwester A, Hansen SG, Smith AT, Stafova P, Shoemaker R, Li Y, Oswald K, Axthelm MK, McDermott A, Ferrari G, Montefiori DC, Edlefsen PT, Piatak M, Jr., Lifson JD, Sekaly RP, Picker LJ. Lymph node T cell responses predict the efficacy of live attenuated SIV vaccines. Nat Med. 2012;18:1673–1681. doi: 10.1038/nm.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klatt NR, Vinton CL, Lynch RM, Canary LA, Ho J, Darrah PA, Estes JD, Seder RA, Moir SL, Brenchley JM. SIV infection of rhesus macaques results in dysfunctional T- and B-cell responses to neo and recall Leishmania major vaccination. Blood. 2011;118:5803–5812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connick E, Folkvord JM, Lind KT, Rakasz EG, Miles B, Wilson NA, Santiago ML, Schmitt K, Stephens EB, Kim HO, Wagstaff R, Li S, Abdelaal HM, Kemp N, Watkins DI, MaWhinney S, Skinner PJ. Compartmentalization of simian immunodeficiency virus replication within secondary lymphoid tissues of rhesus macaques is linked to disease stage and inversely related to localization of virus-specific CTL. J Immunol. 2014;193:5613–5625. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connick E, Mattila T, Folkvord JM, Schlichtemeier R, Meditz AL, Ray MG, McCarter MD, Mawhinney S, Hage A, White C, Skinner PJ. CTL fail to accumulate at sites of HIV-1 replication in lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 2007;178:6975–6983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindqvist M, van Lunzen J, Soghoian DZ, Kuhl BD, Ranasinghe S, Kranias G, Flanders MD, Cutler S, Yudanin N, Muller MI, Davis I, Farber D, Hartjen P, Haag F, Alter G, Schulze zur Wiesch J, Streeck H. Expansion of HIV-specific T follicular helper cells in chronic HIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3271–3280. doi: 10.1172/JCI64314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perreau M, Savoye AL, De Crignis E, Corpataux JM, Cubas R, Haddad EK, De Leval L, Graziosi C, Pantaleo G. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J Exp Med. 2013;210:143–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong JJ, Amancha PK, Rogers K, Ansari AA, Villinger F. Spatial alterations between CD4(+) T follicular helper, B, and CD8(+) T cells during simian immunodeficiency virus infection: T/B cell homeostasis, activation, and potential mechanism for viral escape. J Immunol. 2012;188:3247–3256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, Gerner MY, Boswell KL, Wloka K, Smith EC, Ambrozak DR, Sandler NG, Timmer KJ, Sun X, Pan L, Poholek A, Rao SS, Brenchley JM, Alam SM, Tomaras GD, Roederer M, Douek DC, Seder RA, Germain RN, Haddad EK, Koup RA. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3281–3294. doi: 10.1172/JCI63039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrovas C, Koup RA. T follicular helper cells and HIV/SIV-specific antibody responses. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9:235–241. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan C, Marthas M, Miller C, Duerr A, Cheng-Mayer C, Desrosiers R, Flores J, Haigwood N, Hu SL, Johnson RP, Lifson J, Montefiori D, Moore J, Robert-Guroff M, Robinson H, Self S, Corey L. The use of nonhuman primate models in HIV vaccine development. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu H, Wang X, Lackner AA, Veazey RS. PD-1(HIGH) Follicular CD4 T Helper Cell Subsets Residing in Lymph Node Germinal Centers Correlate with B Cell Maturation and IgG Production in Rhesus Macaques. Front Immunol. 2014;5:85. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onabajo OO, George J, Lewis MG, Mattapallil JJ. Rhesus Macaque Lymph Node PD-1(hi)CD4(+) T Cells Express High Levels of CXCR5 and IL-21 and Display a CCR7(lo)ICOS(+)Bcl6(+) T-Follicular Helper (Tfh) Cell Phenotype. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi S, Seki S, Matano T, Yamamoto H. IL-21-producer CD4+ T cell kinetics during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T, Lynch RM, Gautam R, Matus-Nicodemos R, Schmidt SD, Boswell KL, Darko S, Wong P, Sheng Z, Petrovas C, McDermott AB, Seder RA, Keele BF, Shapiro L, Douek DC, Nishimura Y, Mascola JR, Martin MA, Koup RA. Quality and quantity of TFH cells are critical for broad antibody development in SHIVAD8 infection. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:298ra120. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackburn MJ, Zhong-Min M, Caccuri F, McKinnon K, Schifanella L, Guan Y, Gorini G, Venzon D, Fenizia C, Binello N, Gordon SN, Miller CJ, Franchini G, Vaccari M. Regulatory and Helper Follicular T Cells and Antibody Avidity to Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Glycoprotein 120. J Immunol. 2015;pii:1402699. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuero I, Mohanram V, Musich T, Miller L, Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Demberg T, Venzon D, Kalisz I, Kalyanaraman VS, Pal R, Ferrari MG, LaBranche C, Montefiori DC, Rao M, Vaccari M, Franchini G, Barnett SW, Robert-Guroff M. Mucosal B Cells Are Associated with Delayed SIV Acquisition in Vaccinated Female but Not Male Rhesus Macaques Following SIVmac251 Rectal Challenge. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005101. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Xiao P, Hogg AE, Demberg T, McKinnon K, Venzon D, Brocca-Cofano E, Dipasquale J, Lee EM, Hudacik L, Pal R, Sui Y, Berzofsky JA, Liu L, Langermann S, Robert-Guroff M. Immune targeting of PD-1(hi) expressing cells during and after antiretroviral therapy in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Virology. 2013;447:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommer C, Kothe U, Hamprecht FA. ilastik: Interactive Learning and Segmentation Toolkit. Eighth IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 2011:230–233. S. C. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma CS, Suryani S, Avery DT, Chan A, Nanan R, Santner-Nanan B, Deenick EK, Tangye SG. Early commitment of naive human CD4(+) T cells to the T follicular helper (T(FH)) cell lineage is induced by IL-12. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:590–600. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bannard O, Horton RM, Allen CD, An J, Nagasawa T, Cyster JG. Germinal center centroblasts transition to a centrocyte phenotype according to a timed program and depend on the dark zone for effective selection. Immunity. 2013;39:912–924. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Silva NS, Klein U. Dynamics of B cells in germinal centres. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:137–148. doi: 10.1038/nri3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crotty S. A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:185–189. doi: 10.1038/nri3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nojima T, Haniuda K, Moutai T, Matsudaira M, Mizokawa S, Shiratori I, Azuma T, Kitamura D. In-vitro derived germinal centre B cells differentially generate memory B or plasma cells in vivo. Nat Commun. 2011;2:465. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ueno H. Phenotype and functions of memory Tfh cells in human blood. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suh WK. Life of T follicular helper cells. Mol Cells. 2015;38:195–201. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patterson LJ, Kuate S, Daltabuit-Test M, Li Q, Xiao P, McKinnon K, DiPasquale J, Cristillo A, Venzon D, Haase A, Robert-Guroff M. Replicating adenovirus-simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vectors efficiently prime SIV-specific systemic and mucosal immune responses by targeting myeloid dendritic cells and persisting in rectal macrophages, regardless of immunization route. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:629–637. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00010-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lofano G, Mancini F, Salvatore G, Cantisani R, Monaci E, Carrisi C, Tavarini S, Sammicheli C, Rossi Paccani S, Soldaini E, Laera D, Finco O, Nuti S, Rappuoli R, De Gregorio E, Bagnoli F, Bertholet S. Oil-in-Water Emulsion MF59 Increases Germinal Center B Cell Differentiation and Persistence in Response to Vaccination. J Immunol. 2015;195:1617–1627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mastelic Gavillet B, Eberhardt CS, Auderset F, Castellino F, Seubert A, Tregoning JS, Lambert PH, de Gregorio E, Del Giudice G, Siegrist CA. MF59 Mediates Its B Cell Adjuvanticity by Promoting T Follicular Helper Cells and Thus Germinal Center Responses in Adult and Early Life. J Immunol. 2015;194:4836–4845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moon JJ, Suh H, Li AV, Ockenhouse CF, Yadava A, Irvine DJ. Enhancing humoral responses to a malaria antigen with nanoparticle vaccines that expand Tfh cells and promote germinal center induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1080–1085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112648109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hollister K, Chen Y, Wang S, Wu H, Mondal A, Clegg N, Lu S, Dent A. The role of follicular helper T cells and the germinal center in HIV-1 gp120 DNA prime and gp120 protein boost vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:1985–1992. doi: 10.4161/hv.28659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Addo MM, Altfeld M. Sex-based differences in HIV type 1 pathogenesis. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(Suppl 3):S86–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein SL. Sex influences immune responses to viruses, and efficacy of prophylaxis and treatments for viral diseases. Bioessays. 2012;34:1050–1059. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]