Abstract

Background

The 13-item Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) is a widely used symptom measurement tool yet a systematic review summarizing the symptom knowledge generated from its use in patients with advanced cancer is nonexistent.

Objectives

We performed a systematic review of the research literature in which investigators utilized the SDS as the measure of symptoms in patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

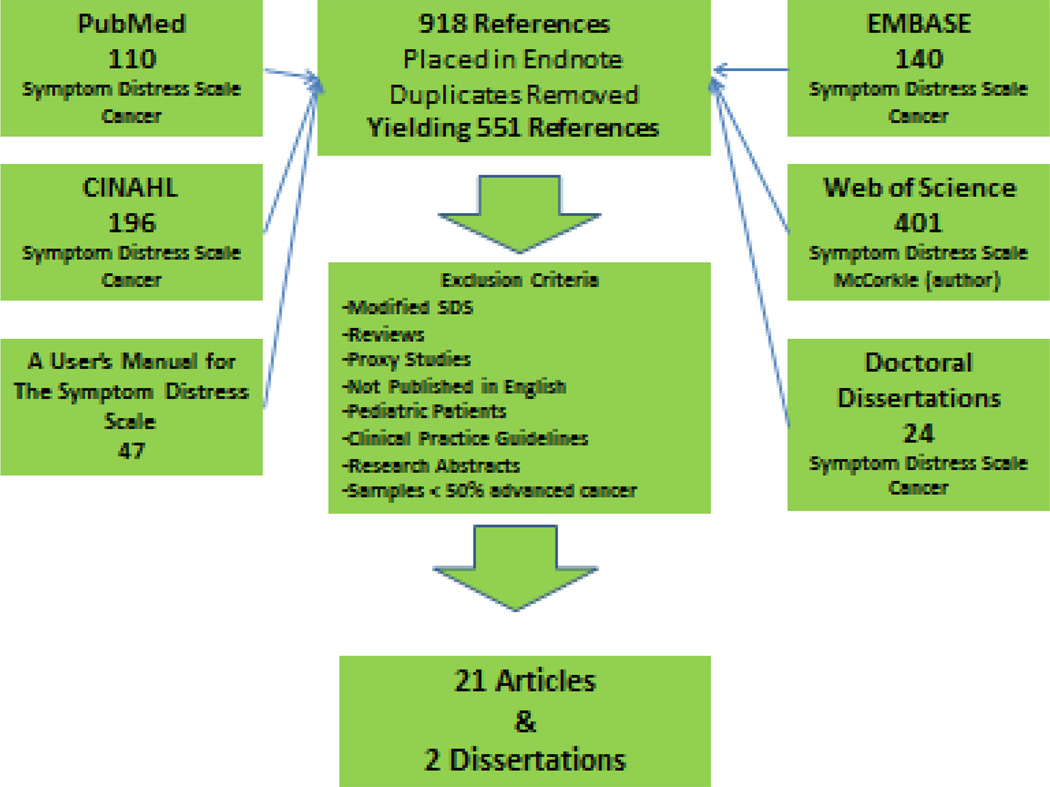

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Web-of-Science for primary research studies published between 1978 through 2013 that utilized the SDS as the measurement tool in patients with advanced cancer. 918 documents were found. Applying inclusion/exclusion criteria, 21 articles and 2 dissertations were included.

Results

The majority of investigators utilized descriptive, cross-sectional research designs conducted with convenience samples. Inconsistent reporting of SDS total scores, individual item scores, age ranges and means, gender distributions, cancer types, cancer stages, and psychometric properties made comparisons difficult. Available mean SDS scores ranged from 17.6–38.8. Reports of internal consistency ranged from .67 to .88. Weighted means indicated fatigue to be the most prevalent and distressing symptom. Appetite ranked higher than pain intensity and pain frequency.

Conclusions

The SDS captures the patient’s symptom experience in a manner that informs the researcher or clinician about the severity of the respondents’ reported symptom distress.

Implications for Practice

The SDS is widely used in a variety of cancer diagnoses. The SDS is a tool clinicians can use to assess 11 symptoms experienced by patients with advanced cancer.

Keywords: Symptom Distress Scale, Systematic Review, Advanced Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Oncology clinicians are well aware that patients with advanced cancer rarely present with just one symptom. Instead, patients are often poly-symptomatic frequently experiencing symptoms such as depression, anxiety, fatigue, pain, poor appetite, and dyspnea 1. Symptom assessment and management affect the patient's quality of life and symptom assessment tools contribute to the identification of symptoms. The Symptom Distress Scale (SDS) 2 has been widely used as a symptom measurement tool in patients with cancer yet a systematic review summarizing the symptom knowledge generated from its use in patients with advanced cancer is nonexistent. Comprehending the knowledge generated from investigations utilizing the SDS is a prerequisite to determining if the tool provides essential data for further research and clinical practice. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of the research literature in which investigators used the 13-item SDS as the measure of symptoms in patients with advanced cancer.

A Brief History of the Development of the Symptom Distress Scale

The 13-item SDS is the seminal product of researchers McCorkle and Young 2. The SDS was created to measure symptoms associated with cancer after the construct of symptom distress was induced from literature reviews, previously developed scales, and patient interviews. McCorkle and Young 2 defined symptom distress as “the degree of discomfort from the specific symptom as reported by the patient.” It is important to note that “distress” was not differentiated according to whether it resulted from the disease itself or from its treatment 3.

The first SDS was comprised of eight symptoms; nausea, mood disturbance, appetite, insomnia, pain, mobility, fatigue, and bowel pattern 3 that were the major concerns identified from previous studies. A group of 60 participants (50% men) from oncology (87%) and medical clinics participated in studies to test the initial SDS. As these 60 participants were interviewed regarding the scale, the investigators added “concentration” to the initial SDS because several participants asked for questions and directions to be repeated. “Appearance” was also added during this phase of scale development due to the concern that several female participants expressed about recent weight gain apparently caused by treatment side effects. Eventually, “mood disturbance” was changed to “outlook” and “breathing” and “cough” were added based on respondents’ reports of complications associated with breathing and coughing 3.

The 13-Item Symptom Distress Scale

The current 13-item SDS questionnaire measures 11 symptoms associated with cancer 3. These items include nausea, appetite, insomnia, pain, fatigue, bowel pattern, concentration, appearance, breathing, outlook, and cough. Nine SDS item responses are designed on a five-point Likert scale with responses ranging from “1” (representing normal or no distress for a given symptom) to “5” (representing extensive distress). Four items concerning the frequency and intensity of pain and nausea have a similar “1” to “5” scale where “1” represents “almost never/mild” and “5” represents “almost constantly/unbearable.” Total SDS scores range from 13 to 65. Initial internal consistency results include an alpha of 0.83 for adults with lung cancer and 0.75 for adults with myocardial infarction 4. Subjects typically require five to 10 minutes to complete the 13-item SDS.

Reliability and Validity of the 13-item Symptom Distress Scale

There are advantages to using the 13-item SDS in research and clinical situations. The SDS is one of the most widely tested instruments for the evaluation of symptom distress 5. The SDS integrates the frequently identified symptoms acknowledged by cancer patients (Table 1). Additionally, the SDS can be completed in a short length of time 6, thereby limiting patient/participant burden. Peruselli and colleagues 5 emphasize that even though the SDS does not include all possible symptoms a patient may experience; it does consider common symptoms that are of most concern sometime through the course of a patient’s cancer trajectory. The SDS does not include the symptom “vomiting” nor does it address oral mucositis, dry mouth, taste changes along with pain and dysfunction due to oral complaints. Rhodes and colleagues 7 are of the opinion that the symptom terminology (e.g., bowel pattern) is confusing and may not be commonly understood. Notwithstanding these criticisms, clinicians and researchers often choose the 13-item SDS to quantify symptom distress in a variety of cancer populations.

Table 1.

SDS Concurrent Validity Studies

| Author | Year | Scale | Correlations with SDS Total Scores |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boehmke | 2004 | Rhodes Adapted Symptom Distress Scale (RASDS) |

T1 (r = .90) T2 (r = .84) T3 (r = .77) |

| 2 | Moro | 2006 | Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale - Italian |

r = 0.77 |

| 3 | Locke | 2007 | Linear Analog Scale Assessments |

T1 (r = .53) T2 (r = .56) T3 (r = .57) |

From Boehmke, 2004; Locke et al., 2007; Moro et al., 2006

Cut points categorizing participants into mild, moderate, or severe distress have not been validated with empirical evidence, only suggested by the author based on professional experience 3. Combining the results of studies over time may provide the empirical evidence necessary to determine what constitutes mild, moderate, and severe distress.

Concurrent validity between the SDS and numerous symptom assessment tools are available in the user’s manual 3. Table 2 contains additional information regarding concurrent validity from articles published after the 1995 user’s manual was in print.

Table 2.

Frequently Reported Symptoms of Cancer Patients in Hospice/Palliative Care (PC)

| Author | Ng | Mercadante | Walsh | Potter | Stromgren |

| Setting | Hospice | PC | PC | PC | PC |

| Sample Size | 1000 | 400 | 100 | 400 | 175 |

| Symptom | Percentages of sample reporting the symptom | ||||

| Pain | 49 | 87 | 84 | 64 | 80 |

| Fatigue | 81 | 69 | 57 | ||

| Anorexia | 70 | 66 | 34 | 8 | |

| Insomnia | 23 | 49 | 12 | ||

| Constipation | 35 | 33 | 52 | 32 | 18 |

| Dyspnea | 61 | 28 | 50 | 31 | |

| Cough | 52 | 38 | 15 | ||

| Nausea | 30 | 25 | 36 | 29 | 26 |

| Memory Problems | 12 | 8 | |||

| Diarrhea | 5 | 8 | 10 | ||

Abbreviations: PC, Palliative Care

Extracted from Mercadante, Casuccio, & Fulfaro, 2000; Ng & von Gunten, 1998; Potter, Hami, Bryan, & Quigley, 2003; Stromgren et al., 2006; Walsh, Donnelly, & Rybicki, 2000

In their studies, the 13-item SDS authors demonstrated reliability [test-retest (r = .78), Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70 to 0.85] 4, 8 along with content validity 2 and construct validity 8 in cancer populations. The 13-item SDS was one of the initial valid and reliable symptom assessment tools developed for symptom assessment in oncology study participants 9 during the time when cancer study participants were surviving longer while experiencing terrible side effects.

Our purpose is to present a systematic review of empirical studies that utilized the 13-item SDS as the symptom measurement tool in participants with advanced cancer. Specifically, we aim to:

Describe the characteristics of studies using the 13-item SDS to assess symptoms experienced by study participants with Stage III and Stage IV cancer.

Examine 13-item SDS scores by cancer site.

Discuss the evidence for 13-item SDS scores that represent mild, moderate, and severe levels of distress.

Methods

A comprehensive, electronic search of PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases provided an initial list of potential articles for review; a hand search of references lists provided additional articles. Since the 13-item SDS first appeared in the literature in 1978, searches included articles published beginning that year. Initial search terms included “symptom distress scale” and “cancer.” We also used Web of Science to capture the articles that cited the first publication of the 13-item SDS. We found 918 articles before removing duplicates. A total of 551 articles (Figure 1) were identified for further review.

Figure.

Search Strategy

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We reviewed abstracts of the 551 articles to determine if inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. English language articles in which the 13-item SDS was used to measure symptom distress in participants with advanced cancer were included. Our definition of advanced cancer incorporated the descriptors “advanced cancer,” “terminal,” “hospice,” and samples with greater than 50% of participants having Stage III or IV cancer. We excluded studies focused on pediatric cancer populations. We only included studies utilizing the 13-item SDS and excluded studies using the 10-item SDS, studies modifying the 13-item SDS, studies only using SDS item “fatigue,” studies using a 14 or 15-item SDS and studies using altered 13-item SDS scoring. We excluded articles that did not include numerical information about each component of the 13-item SDS. Also excluded were review articles, proxy studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

RESULTS

A sample of 21 articles and 2 dissertations remained for the final review. We obtained hard copies of the 23 documents and extracted the following information: a) author, publication year, first author’s credentials, country; b) setting, design, statistical techniques; c) cancer stage; d) age range (Mean, standard deviation); e) gender sample size; f) cancer type; g) SDS total mean (SD); h) Cronbach’s alpha; i) SDS range; j) cut scores; k) SDS item scores; and l) findings.

Characteristics of the Studies

In Table 3, we present a summary of the literature included in this review. The publication timeframe of the reviewed studies ranged from 1985 through 2013. Nurses were first authors on the majority of studies (79%) with physicians (13%), a gerontologist, and an author with no professional credentials reported accounting for the remaining first authors. Two studies were dissertations conducted by nurses. Only two investigators reported that the paper version of the 13-item-SDS required 5–10 minutes to complete.

Table 3.

Summary of Literature using the Symptom Distress Scale as the Symptom Assessment Tool

| Author, Year, First Author’s Credentials Country |

Setting, Design, Statistical Techniques |

CA Stage | Age Range (Mean, SD) | Gender | CA Type(s) | SDS Total Mean (SD) | Cronbach's Alpha | SDS Range | Cut Scores | SDS Item Scores | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germino 1985 Nurse USA |

Radiation Outpatient Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Life Threatening |

NR NR |

Male (62.5%) Female (37.5%) N=56 |

Lung (100%) | T1 = 26.8 (8.4) T2 = 26.4 (8.4) |

α= .79 | NR | 1 = least distress 2,3,4 = intermediate 5=extreme |

No | Patients with cancer with high levels of symptom distress had higher levels of acknowledged awareness of symptoms. |

| Degner 1987 Nurse Canada |

Palliative Care Corr Cross-Sect |

Terminal | 33–89 65.5 |

Male (52%) Female (48%) N=29 |

NR | T1= 33.8 T2= 25.7 |

T1 α=.67 T2 α=.72 |

NR | 1 (no distress) 5 (extreme) Higher = greater |

No | Demonstrated the SDS was a useful measure to evaluate the effectiveness of palliative care. |

| Frederickson 1991 Nurse USA |

Oncology Unit Corr Cross-Sect |

Advanced Unresectable Cancer |

19–61 45(11) |

Male (56%) Female (44%) N=45 |

Melanoma (42%) Renal Cell (38%) Breast (7%) Colon (7%) |

17.6 (5.9) | NR | NR | NR | No | Demonstrated that perception of symptoms is positively correlated with psychosocial adaptation - not with actual psychological status. |

| Peruselli 1993 Nurse Italy |

Palliative Care Corr Cross-Sect |

Advanced Cancer |

45–88 67 |

Not Reported N=43 |

Lung (35%) GU (26%) Breast (9%) Bowel (9%) |

NR | α=.78 | NR | 4,5 = Serious | No | Confirmed the validity of QOL monitoring system that uses self-rating assessment instruments. |

| Sarna 1993 Nurse USA |

Medical Ctr Private Offices Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Advanced Lung Cancer |

32–86 61(11) |

Male (0 %) Female (100%) N=69 |

Lung (100%) | 23.4 (6.9) | NR | NR | NR | No | Reported physical, emotional, and social disruptions in the QOL of women with lung cancer. |

| DegnerA 1995 Nurse Canada |

Tertiary Referral Clinics Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Early (12%) Late (72%) |

NR 64.2 (9.72) |

Male (61%) Female (39%) N=82 |

Lung (100%) | 26.97(7.79) | α=.81 | NR | NR | No | Measuring symptom distress was a significant predictor of survival in patients with lung cancer. |

| Northouse 1995 Nurse USA |

Clinic Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Recurrent Breast Cancer |

30–82 53.8 (12.0) |

Female (100%) N=81 |

Breast (100%) | NR | α=.84 | NR | Higher = greater | No | Suggest that there are multiple factors that could influence a couple's adjustment to recurrent breast cancer. |

| BarnesC 1997 Nurse USA |

Hospice Home Care Descriptive Long |

NR | 31–95 66 |

Male (43.3%) Female (56.7%) N=30 |

NR | 29.12 (8.58) |

α=.79 | NR | Higher = greater | No | Identified that caregiver perceived symptom distress was closely correlated to patient's actual distress. |

| Lobchuk 1997 Nurse Canada |

Palliative Care Oncology Units Descriptive Long |

Stage I (11%) Stage II (15%) Stage III (59%) Stage IV (15%) |

NR NR |

Male (68%) Female (32%) N=41 |

Lung (100%) | 27.76 (9.44) |

α=.88 | NR | Higher = greater | Yes | Demonstrated little differences between patients and primary family caregivers’ perception of symptoms. |

| Peruselli 1997 Physician Italy |

Palliative Care Descriptive Long |

Advanced Cancer |

30–85 NR |

Male (52.1%) Female (47.9%) N=73 |

GI Tract(22%) Bowel (18%) Lung (16%) Breast (9%) |

T1 = 30.3 T2 = 29.2 T3 = 33.1 |

NR | NR | NR | No | Some individual trajectory of changes in palliative care patients could be identified relative to the treatments performed. |

| Sarna 1993 Nurse USA |

Oncology Unit Clinics Private Offices Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Advanced Lung Cancer |

33–80 58.3 (9.7) |

Male (0%) Female (100%) N=69 |

Lung (100%) | 25.5 (6.94) |

NR | 14–44 | ≥3 = serious distress | Yes | Identified clusters of symptoms in women with advanced lung cancer |

| Kristjanson 1998 Nurse Australia |

Home Hospice Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Stage III Stage IV |

NR 65.5 (10.8) |

Male (51%) Female (49%) N=78 |

Breast (20.5%) Genitourinary (15.4%) Colon (15.4%) Lung (14.1%) |

29.6 (7.5) | α= .74 | 13–52 | 1 (no distress) 5 ( extreme) |

Yes | Supports previous work indicating family members may function as proxy to rate patient's symptom distress. |

| Morasso 1999 N/A Italy |

Palliative Care Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Terminal | NR 64.8 (11.1) |

Male (57.3%) Female (42.7%) N=94 |

Lung (22.7%) Breast (18.2%) Stomach (11.4%) Colorectal (11.4%) |

31.0 (8.0) | α= .76 | NR | 1 (no distress) 5 ( extreme) Higher = greater |

No | Addresses concerns that should be addressed during the late stage of cancer |

| Porock 2000 Nurse Australia |

Home Hospice Descriptive Long |

Advanced Cancer |

51–77 59.9 (9.8) |

Male (34%) Female (66%) N=9 |

Bowel (44%) Pancreas (22%) Melanoma (11%) Breast (11%) |

NR | NR | 22–27 | Higher = greater | Yes | Patients with cancer in home hospice enjoyed the individual approach to exercise, and in no instance was fatigue made worse. |

| BoucherC 2002 Nurse USA |

Cancer Clinic Exp. Long |

Early (28%) Late (55%) |

NR 56.9 (10.9) 55.2 (14.5) |

Male (44%) Female (66%) N=100 |

Breast (30%) Lung (19%) Lymphoma (13%) Prostate (10%) |

23.4 (5.60) |

α=.71 | NR | Higher = greater | No | Reduced symptom distress was related to positive mood states. |

| ChochinovB 2002 Physician Canada |

Palliative Care Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Terminal | NR 69 (12.6) |

Male (45%) Female (55%) N=213 |

Lung (31%) GI Tract (23%) GU (17%) Breast (14%) |

NR | NR | NR | Higher = greater | No | Identified when loss of dignity is a concern, more psychological and symptom distress is reported. |

| Tang 2003 Nurse Taiwan |

Hospice Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Terminal | 34–88 66.8 |

Male (41.7%) Female (58.2%) N=127 |

Lung (29.1%) Breast (15.8%) Ovarian (7.1%) Colon (7.1%) |

NR | α=.75 | NR | Higher = greater | No | The availability of home hospice did not influence its use. |

| HackB 2004 Physician Canada |

Palliative Care Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Terminal | NR 69.0 (12.6) |

Male (45%) Female (55%) N=213 |

Lung (31%) GI (23%) GU (17%) Breast (14%) |

NR | NR | NR | Higher = greater | No | Dignity is a fundamental component of end of life care and should be addressed by healthcare professionals. |

| Oh 2004 Nurse Korea |

Respiratory and Oncology Units Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Stage I (3%) Stage II (6%) Stage III (32%) Stage IV (54%) |

NR 60.9 (10.4) |

Male (76.4%) Female (23.6%) N=106 |

Lung (100%) | 32.74 (10.75) |

α=.87 | NR | NR | Yes | Korean patients with lung cancer appear to experience higher symptom distress scores than western countries. |

| Tang 2006 Nurse Taiwan |

Medical Ctr Oncology Units Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Terminal | 20–89 Median 60 |

Male (43%) Female (57%) N= 114 |

Hematologic (18.4%) Lung (16.7%) Breast (14.9%) Colorectal (14.9%) |

27.8 (9.0) | α= .85 | NR | 1 (no distress) 5 ( extreme) Higher = greater |

Yes | Confirmed ability of family caregivers to act as reasonably reliable source of QOL data. |

| Schulman- Green 2008 Gerontologist USA |

Cancer Center Descriptive Cross-Sect |

Early (33.8%) Late (65.5%) |

21–86 60.8 (11.8) |

Female (100%) N=145 |

Ovarian (100%) | 27.83 (8.98) |

α=.74 | 13–52 | Higher = greater | NR | Women undergoing ovarian surgeries for cancer have psychological needs that offer are considered secondary to their physical needs. |

| McCorkle 2009 Nurse USA |

Cancer Center Exp Long |

Early (33%) Late (66%) |

NR I-58.4 (11.3) C-62.2 (12.7) |

Female (100%) N=123 |

Ovarian (61.8%) | Baseline I = 29.0 (6.7) C = 26.8 (6.6) One Month I = 25.3 (6.9) C = 23.2 (6.3) Three Months I = 24.7 (6.2) C = 22.0 (6.4) Six Months I = 22.9 (6.8) C = 19.9 (5.1) |

NR | NR | NR | NR | Nurse interventions targeting both physical and psychological aspects of QOL produce stronger outcomes than targeting only 1 QOL aspect. |

| Wallen 2012 Nurse USA |

Outpatient Clinic & Surgical Oncology Long Mixed- Methods |

Advanced Malignancy |

NR | Male (53.2%) Female (46.7%) |

NR | Reported baseline and post- op for PPCS and Standard of Care |

NR | 22.19 (6.6) 28.37 (6.9) |

NR | NR | Participants in the PPCS group tended to have lower SDS scores, although not significantly different from the standard of care. |

| Van Cleave 2013 Nurse USA |

Cancer Center Long |

Early (52.8%) Late (35.9%) Unknown (11.3%) |

71.8 (5.4) |

Male (49.7%) Female (49.4%) |

Digestive (22.4%) Thoracic (27.6%) Gyne (23.0%) GU (27.0%) |

Reported baseline, at 3 and 6 months in 3 age categories |

NR | 17.0 (5.1) 29.3 (7.2) |

NR | NR | Patients with heightened symptom distress had worse mental health and decreased function. Thoracic, digestive, and gyne cancer patients experienced greater symptom distress. Patients reporting 3 or more co-morbidities experienced greater distress. |

Abbreviations: Corr, Correlational; Cross-Sect, Cross Sectional; Exp, Experimental; Gyne, Gynecological; Long, Longitudinal; NR, Not Reported; PPCS, Pain and Palliative Care Service.

Only used Lung cancer participants due to inability to calculate cancer stage percentages in the mixed cancer sample.

Used same sample

Dissertation

The 13-item SDS has been used in many countries and settings. The United States (n=10) was the country where most studies were conducted. Other investigators were from Canada (n=5), Italy (n=3), Australia (n=2), Taiwan (n=2) and Korea (n=1). Studies were conducted in medical center clinics or inpatient units (n=7), palliative care (n=7), home or in-patient hospice settings (n=4), or oncology clinics/units (n=5).

Characteristics of Study Designs

Researchers used descriptive (n=17), correlational (n=4), interventional (n=1), or mixed-methods (n=1) designs. There were 14 studies utilizing a cross-sectional data collection process and ten studies utilizing a longitudinal data collection process. Statistical analyses included bivariate (n=16) and multivariate (n=8) techniques.

Characteristics of Study Samples

Sample sizes ranged from nine to 213 participants. There were six studies with less than 50 participants, nine studies with samples between 51 to100 participants, six studies with 101 to 200 participants, and two publications from a study of the same 213 participants.

Ages of participants ranged from 19 years to 95 14 with the mean ages of participants ranging from mean of 45 (SD=11) to mean of 69 (SD = 12.6) years. In five studies 100% of the sample was female with the remaining studies having nearly equal gender distribution or either 60% to 40% male to female or 60% to 40% female to male distributions.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency was reported using Cronbach’s alpha in 14 of the 23 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. These reported values ranged from α = .67 to α = .88.

Characteristics of Study Participants’ Type of Cancer

Researchers who reported participants’ cancer stages categorized their participants as advanced (n=7), terminal (n=6), life threatening (n=1), or recurrent (n=1). These researchers enrolled 55% to 86% of participants with stage III and stage IV cancer. Researchers investigated samples with single site cancers including lung (n=6), ovarian (n=2) and breast (n=1). In studies of mixed cancer sites, study participants with lung cancer ranged from 16% to 35%, breast cancer 7% to 30%, colorectal 7% to 44%, gastric (stomach) 11.4% to 23%, melanoma 11% to 42%, renal cell 38%, pancreas 22%, lymphoma 13% and 18% hematologic cancers 15. Overall, 1,896 study participants are included in this review. The three most frequently enrolled subjects included study participants with lung cancer [n=655 (37.5%)], ovarian cancer [n=277 (15.9%)] and breast cancer [n=238 (13.7%)].

Weighted Means

Weighted means allow the researcher to determine the relative importance of each item across studies with consideration of the size of the sample that contributed to the study mean score. To compare item scores across studies, we placed the SDS item scores from researchers reporting individual scores in a table and computed weighted means for each item. We multiplied the mean scores for each SDS item by the number of participants in that study. We then added each product (mean score times number of participants) for each SDS item score across the six studies, dividing this number by the total number of participants, yielding weighted mean results.

Total 13-Item SDS and Individual Item Scores

Total SDS Scores

Seventeen investigators reported mean SDS total scores that ranged from 17.6 (SD = 5.9) to 32.74 (SD = 10.75). Five investigators reported means and standard deviations for the 13 item scores and SDS total scores (Table 4). Porock 16 reported mean scores without standard deviations for the 4 most distressing 13-item SDS symptom items and the 4 least distressing symptoms items (Table 4).

Table 4.

SDS Item and Total Scores, Weighted Means and Rank Order

| Lobchuk (1997) |

Sarna (1997) |

Kristjanson (1998) |

Porock (2000) |

Oh (2004) |

Tang (2006) |

Weighted Mean |

Rank Order |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=41 | n=60 | n=78 | n=9 | n=106 | n=114 | |||||||||

| Score | SD | Score | SD | Score | SD | Score | SD | Score | SD | Score | SD | |||

| Fatigue | 2.95 | 1.22 | 2.80 | 1.12 | 3.21 | 1.14 | 2.60 | NR | 2.97 | 1.20 | 2.75 | 1.30 | 2.92 | 1 |

| Appetite | 2.14 | 1.16 | 1.98 | 1.07 | 2.47 | 1.38 | NR | NR | 3.13 | 1.39 | 2.61 | 1.20 | 2.52 | 2 |

| Pain (Frequency) | 2.35 | 1.27 | 2.23 | 1.28 | 2.60 | 1.30 | 2.80 | NR | 2.68 | 1.66 | 2.33 | 1.30 | 2.47 | 3 |

| Appearance | 1.92 | 0.92 | 1.70 | 0.83 | 2.53 | 1.29 | NR | NR | 2.78 | 1.37 | 2.58 | 1.20 | 2.37 | 4 |

| Insomnia | 2.22 | 1.25 | 2.12 | 1.25 | 2.18 | 1.10 | NR | NR | 2.49 | 1.27 | 2.76 | 1.30 | 2.37 | 4 |

| Cough | 2.57 | 1.07 | 2.07 | 1.07 | 1.97 | 1.01 | 1.28 | NR | 2.74 | 1.38 | 2.23 | 1.30 | 2.30 | 5 |

| Outlook | 2.24 | 1.26 | 2.27 | 0.88 | 2.23 | 1.13 | 2.56 | NR | 2.76 | 1.12 | 1.61 | 1.00 | 2.21 | 6 |

| Pain (Intensity) | 1.87 | 0.95 | 1.80 | 0.96 | 2.12 | 0.95 | NR | NR | 2.56 | 1.45 | 2.04 | 1.10 | 2.09 | 7 |

| Concentration | 1.78 | 1.06 | 1.80 | 0.86 | 2.18 | 1.07 | NR | NR | 2.65 | 1.29 | 1.76 | 0.90 | 2.04 | 8 |

| Breathing | 2.22 | 1.26 | 2.27 | 0.88 | 2.23 | 1.13 | 2.56 | NR | 2.48 | 1.34 | 1.64 | 1.00 | 2.02 | 9 |

| Bowel Pattern | 2.00 | 1.39 | 1.62 | 0.96 | 2.31 | 1.38 | 2.52 | NR | 1.85 | 1.06 | 1.85 | 1.10 | 1.93 | 10 |

| Nausea (Intensity) | 1.72 | 0.91 | 1.73 | 1.01 | 1.77 | 1.15 | 1.52 | NR | 1.89 | 1.12 | 1.90 | 1.20 | 1.82 | 11 |

| Nausea (Frequency) | 1.72 | 0.85 | 1.58 | 0.93 | 1.90 | 1.09 | 1.47 | NR | 1.90 | 1.34 | 1.81 | 1.10 | 1.80 | 12 |

| Total SDS | 27.76 | 9.44 | 25.50 | 6.94 | 29.59 | 7.54 | NR | NR | 32.74 | 10.75 | 27.80 | 9.00 | ||

| Gender | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||||||||

| Male | 68 | Male | 0 | Male | 51 | Male | 34 | Male | 76 | Male | 43 | |||

| Female | 32 | Female | 100 | Female | 49 | Female | 66 | Female | 24 | Female | 57 | |||

In a comparison study investigating perceived awareness of life threatening illness 17, participants were surveyed at one and two months after initial diagnosis. Results indicate higher 13-item SDS total scores for study participants with cancer at one month (mean = 26.8, SD = 8.4) and two months (mean = 26.4, SD = 8.4) compared to study participants with myocardial infarction at one month (mean = 19.2, SD = 4.6) and two months (mean = 19.1, SD = 4.8).

SDS Item Scores

Of the six studies in which investigators reported SDS item scores, fatigue ranked as the most distressing 18–20 or second most distressing symptom 15,16,21. Nausea frequency, nausea intensity, bowel pattern, outlook, and breathing were the lowest item scores.

Weighted Means

Table 4 also shows the calculated weighted means (WM) from the six investigators who reported SDS item scores and demonstrated that fatigue (WM = 2.92) was the most distressing item with nausea frequency (WM = 1.90) as the least distressing item. Weighted mean results also indicated appetite ranked higher than pain frequency and pain intensity.

SDS Scores by Cancer Type

Degner and Sloan 22 recruited a sample of 434 newly diagnosed cancer study participants. Demographic and disease characteristics were reported for the total sample and a subsample of participants with lung cancer (n = 82). These researchers excluded 37% (n=159) of the general sample because cancer stage information was unavailable. The remaining 63% (n=275) of participants in the general sample with documented cancer stages were dichotomized as early stage cancer (n = 127) with SDS total scores (mean = 21.56, SD 5.60) and late stage cancer (n = 148) with SDS scores (mean = 26.08, SD = 7.80). There was a statistically significant difference (t (273) = 5.44, p < .0001) between participants with early stage cancer and those with late stage cancer indicating that participants with later stage cancer reported higher symptom distress. These researchers conducted a separate analysis of participants with lung cancer undergoing treatment. Fifty-nine (72%) of the participants were reported to have advanced stage lung cancer, 11 (13%) early stage cancer and 12 (15%) had missing cancer stage information. There was only one reported SDS total score (mean = 26.97, SD = 7.79) for these 82 participants. However, there was no statistical difference (t (228) = .83, p<.40) between participants with advanced stage cancer and participants with lung cancer in this sample.

The majority of studies in this review included samples that were heterogeneous for type of cancer. Unlike Degner and Sloan 22 who differentiated a sub-sample of participants with lung cancer from the remainder of the sample, other investigators did not report similarities or differences in SDS scores by different cancer types. However, findings from several researchers studying samples homogeneous for lung or ovarian 23,24 cancer allow for comparison of SDS total scores by cancer type. Mean SDS total scores for lung cancer participants ranged from 23.4, SD = 6.9 25 to 32.7, SD = 10.75 21 whereas mean SDS total scores for ovarian cancer participants ranged from 27.83, SD = 8.98 24 to 29.0, SD = 6.723.

Determining Distress

Two investigators used the categories of “1” meaning the “least” amount of distress, “2, 3, 4” meaning the participant is experiencing “intermediate” amount of distress, and “5” indicating “extreme” distress 12,17. No information was provided that would allow for analyzing the distribution of symptom distress by cancer type in these two articles except Germino and McCorkle 17 only recruited participants with lung cancer. Only one investigator differentiated distress by two levels 22 identifying “1” or “2” as low distress and “3”, “4”, “5” identified as high distress. Degner and Sloan 22 report that participants with lung cancer have the highest symptom distress and men with genitourinary cancer have the least distress. Peruselli and colleagues 5 dichotomized total symptom distress scores <36 to indicate “low” symptom distress and ≥ 36 to represent “high” symptom distress. Although a heterogeneous cancer sample was recruited, only total SDS scores were reported at the beginning of home palliative care, the total SDS score after two weeks and the highest SDS score over the last two weeks of life. Therefore, we were unable to analyze SDS total scores by cancer type in this sample.

Twelve investigators described individual SDS item scores using 1 (normal or no distress) to 5 (extensive distress). Seven investigators reported SDS total scores ranging from 13 (lowest distress) to 65 (highest distress). Although these scores represent the complete range of possible scores, insufficient data regarding the distribution of cancer type were presented in these studies to determine individual SDS scores by cancer type.

Determining mild, moderate, and severe distress with the 13-ITEM-SDS

Three investigators indicated that the higher the scores, the greater the symptom distress 10,26,27. Specifically, Chochinov and colleagues 10 investigated dignity in the terminally ill study participants and identified that participants with a fractured sense of dignity had increased awareness of their appearance and increased pain intensity compared to those whose sense of dignity remained intact. The investigators report SDS item means and standard deviations for SDS items pain severity, pain frequency, bowel concerns, appearance, and outlook, but not for the eight remaining SDS items. The investigators concluded those with a fractured sense of dignity experienced higher symptom distress. Total SDS scores, means, or standard deviations were not reported. Northouse and colleagues 26 identified a moderate correlation between a woman’s symptom distress and hopelessness (r = .53, p <. 0.01), emotional distress (r = .42, p < 0.01) and the decreased ability to carry out psychosocial roles (r = .52, p < 0.01), but did not report SDS total or item scores. Sarna 25 found a strong relationship between symptom distress and quality of life (r = .72, p < 0.05) as measured by the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES-SF) 28,29. Higher scores on the CARES-SF indicate increased disruption. Therefore, the higher the symptom distress, the lower the quality of life. However, Sarna 25 reports only a mean SDS score for the entire sample.

DISCUSSION

We critically evaluated the literature where the 13-item SDS was utilized as the symptom measurement tool in patients with advanced cancer in an attempt to: 1) describe the characteristics of the studies, 2) examine SDS scores by cancer site, and 3) discuss the evidence for SDS scores that represent mild, moderate, and severe levels of distress. The structure of the 13-item SDS captures 11 symptoms associated with cancer while allowing for individualized reflection of the symptom experience. Investigators’ inconsistent reporting of SDS total scores, individual item scores, age ranges and means, and psychometric properties made comparisons challenging. Despite these difficulties, our review clearly demonstrates the 13-item SDS scale is a useful symptom measurement tool in the advanced cancer patient population. However, based on the evidence, we were unable to determine ranges that would support classifying mild, moderate, or severe symptom distress.

Study Characteristics

Our findings demonstrate the majority of investigators utilized descriptive, cross-sectional research designs conducted with convenience samples in a variety of settings. These settings included cancer centers, clinics, hospices, patient homes, and inpatient oncology units. Percentages of male and female participants appear to be representative of the general population unless the researchers were studying a gender specific type of cancer such as ovarian cancer. Researchers reported moderate (α=0.65 to 0.79) to strong (α>0.80) reliability thereby demonstrating the consistency of the SDS.

SDS Item Scores

This review of the 13-item SDS scale demonstrated pain often is not the most distressing symptom reported by the participants with advanced cancer. Investigators reporting SDS item scores indicated that fatigue scores (1–5) ranged from 2.6 (SD = NR) to 3.21 (SD = 1.14), whereas pain frequency ranged from 2.23 (SD = 1.28) to 2.8 (SD = NR) and pain intensity ranged from 1.0 (SD = 0.95) to 2.76 (SD = 1.12). These findings, which are similar to findings from other investigators 30,31, indicate fatigue is a highly prevalent and distressing symptom in lung, breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers.

Arguably, SDS items bowel pattern, concentration, appearance, and outlook are not what one thinks about when listing symptoms, rather they represent a combination of symptoms. For example, when assessing for symptoms associated with the bowel, study participants are often asked questions regarding the presence of diarrhea or constipation along with the number of stools per day. The SDS bowel pattern item groups all bowel symptoms into one item and then asks if the patient is experiencing normal bowel patterns. If they are not experiencing normal bowel patterns, the SDS scale then elicits how an increasing intensity or increasing frequency of the bowel pattern leads to increasing distress for the participant. The SDS is a tool to screen for symptoms that may require a more in depth assessment and/or measurement. For example, further investigation is warranted when a participant reports distress from SDS item bowel pattern, before further measurement is conducted or treatment is provided.

There are other SDS item scores of interest. For example, SDS items “appearance” [mean 2.53, (SD = 1.29)] and “appetite” [mean 2.47, (SD = 1.38)] in a heterogeneous cancer sample 18 are ranked the third and fourth most distressing symptoms with “fatigue” [mean 3.21 (SD = 1.14)] and “pain frequency” [mean 2.60 (SD = 1.30)] ranked first and second. In describing the symptom experience of 106 Korean adults with lung cancer (Oh, 2004) the 13-ITEM-SDS item “appetite” [mean 3.13 (SD = 1.39)] ranked higher than “fatigue” [mean 2.97 (SD = 1.20)] and “pain frequency” [mean 2.68 (SD = 1.66)]. Findings from these studies suggest multiple, distressing symptoms occur. Symptom Distress Scale items such as appearance and appetite, along with other SDS items scores taken individually may not be the most distressing symptoms, but when co-occurring with other SDS items may add to respondents’ symptom distress.

SDS Scores by Cancer Site

Patients with advanced lung, breast, gyne, and prostate cancers account for the majority of cancer sites within this review. A consistent finding in this analysis indicates that results generated from investigators who recruited a sample with high percentages of lung cancer participants tend to have higher total SDS scores. Degner and Sloan 22 in their cross-sectional sample of early stage, late stage, and participants with lung cancer demonstrate SDS scores increase with cancer stage. Oh 21 reports in a sample of Korean adults with lung cancer higher scores compared to scores reported in Western countries. Possible reasons for these higher scores may be due to 91% of the participants being diagnosed with stage III and IV cancers and the high portion of participants who were receiving active treatment. These results add evidence to the growing body of knowledge indicating participants with lung cancer experience more symptom distress than participants with other cancers. However, the SDS items focused on “breathing” and “cough” distress, which are two symptoms often seen in participants with lung cancer and may affect total SDS scores. Further research is needed to explore the cumulative effect of SDS items “breathing” and “cough” on total SDS scores in participants with lung cancer who typically present with late stage cancer. Determination if participants with lung cancer experience an overall greater symptom distress or is there greater symptom distress in each cancer stage compared to cancer study participants with other types of cancer.

Determining levels of distress

Findings from our analysis of studies using the 13-item SDS indicate participants with advanced cancer experienced total symptom distress scores ranging from a mean of 17.6 (SD = NR) to a mean of 33.8 (SD = NR). However, our investigation shows that determining the categories for the degree of symptom distress (mild, moderate, and severe) has not been accomplished from sufficient empirical evidence. Our review demonstrates that researchers defined symptom distress based on total SDS scores or individual SDS item scores. Researchers either followed suggested guidelines set by the SDS developers 23, categorized symptom distress as least, intermediate, and severe or dichotomized distress levels as low or high distress. When defining symptom distress no researcher used another measurement tool to establish symptom severity levels. Conducting studies to establish concurrent validity with another measurement tool with defined degrees of distress may solve this issue.

LIMITATIONS

This review is not without limitations. First, we did not include end-of-life as one of our search terms which may have captured articles not captured by the term advance cancer. Second, non-reported, or incomplete demographic, total SDS scores, individual item scores, cancer staging, or internal consistency information limits the interpretation of the results. Third, limiting inclusion criteria to articles using the English language may have excluded pertinent studies. Fourth, our definition of advanced cancer incorporated studies that included Stage I and Stage II cancers as long as ≥ 50% of the participants were diagnosed with Stage III or IV cancers. It is impossible to elicit whether inclusion of these participants with early cancer stages might have skewed the SDS scores. Fifth, the majority of included studies were descriptive, cross-sectional designs with limited generalizability. Finally, the primary author as the only reviewer may have introduced bias to the results of this review.

IMPLICATIONS PRACTICE

Findings from this study inform the knowledge gained from the utilization of the 13-item SDS scale by investigators exploring the symptom experience of participants with advanced cancer. The SDS scale provides a measure of distress on 11 symptoms experienced by participants with cancer. In an era of scarce resources, utilizing an established, valid, and reliable symptom assessment tool that measures symptoms in study participants with cancer is sensible.

The 13-Item SDS in Clinical Practice

Clinicians will find the SDS a valuable symptom measurement tool that determines the severity of symptom distress and is especially useful as a screening tool for symptoms commonly experienced by patients with cancer. The SDS can be used as part of the routine clinical monitoring of patients with cancer. Using suggested cut points for mild, moderate, and severe distress may provide the necessary data when triaging which study participants need your immediate assistance.

Future Research

We recommend future researchers who utilize the SDS report mean total scores with standard deviations, individual item scores by cancer type, cancer stage, and item correlations. Reporting these findings will enhance the ability of researchers to address additional hypotheses that may be answered by combining findings from published studies using the SDS and performing meta-analyses. Further research is needed to empirically define cut scores. Additionally, interventions may be developed to address study participants reporting mild, moderate, or severe distress.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the 13-item SDS scale is a valid and reliable, widely used in a variety of cancer diagnoses. These findings add to the knowledge generated regarding the experiences of study participants with cancer. In particular this review support the research that demonstrates fatigue is the most prevalent symptom, not pain. Our review also demonstrates the SDS captures the patient’s symptom experience in a manner that informs the researcher or clinician about the severity of the respondents’ reported symptom distress. The use of simple, yet informative measurement tools that captures the patient’s symptom experience is paramount to providing effective symptom management in all phases of the cancer trajectory.

Acknowledgement

Grant Number 1F31NR010048 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research, supported this publication. Grant Number R01 NR009092 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research supported data collection and P30 NR010680 supported manuscript preparation. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research. The final peer-reviewed manuscript is subject to the National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Chen E, Nguyn J, Cramarossa G, et al. Symptom clusters in patients with advanced cancer: Sub-analysis of patients reporting exclusively non-zero ESAS scores. Palliat Med. 2012;26(6):826. doi: 10.1177/0269216311420197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCorkle R, Young K. Development of a symptom distress scale. Cancer Nurs. 1978;1(5):373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCorkle R, Cooley M, Shea J. A user's manual for the symptom distress scale. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCorkle R, Benoliel J, Donaldson G, Georgiadou F, Moinpour C, Goodell B. A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer. 1989;64(6):1375–1382. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890915)64:6<1375::aid-cncr2820640634>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peruselli C, Paci E, Franceschi P, Legori T, Mannucci F. Outcome evaluation in a home palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider S, Prince Paul M, Allen M, Silverman P, Talaba D. Virtual reality as a distraction intervention for women receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(1):81–88. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes VA, Watson PM, Johnson MH, Madsen RW, Beck NC. Patterns of nausea, vomiting, and distress in patients receiving antineoplastic drug protocols. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1987;14(4):35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCorkle R, Quint Benoliel J. Symptom distress, current concerns and mood disturbance after diagnosis of life-threatening disease. Social science medicine. 1983;17(7):431–438. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esther Kim J, Dodd M, Aouizerat B, Jahan T, Miaskowski C. A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):715–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chochinov H, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson L, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity in the terminally ill: A cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2026–2030. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)12022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hack T, Chochinov H, Hassard T, Kristjanson L, McClement S, Harlos M. Defining dignity in terminally ill cancer patients: A factor-analytic approach. Psychooncology. 2004;13(10):700–708. doi: 10.1002/pon.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peruselli C, Camporesi E, Colombo AM, Cucci M, Mazzoni G, Paci E. Quality-of-life assessment in a home care program for advanced cancer patients: A study using the symptom distress scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8(5):306–311. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90159-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morasso G, Capelli M, Viterbori P, et al. Psychological and symptom distress in terminal cancer patients with met and unmet needs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(6):402–409. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes C. Cohesion, flexibility, symptom distress, and coping in hospice home care families. [Doctoral] Medical College of Georgia; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang S. Concordance of quality-of-life assessments between terminally ill cancer patients and their primary family caregivers in Taiwan. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(1):49–57. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porock D, Kristjanson LJ, Tinnelly K, Duke T, Blight J. An exercise intervention for advanced cancer patients experiencing fatigue: A pilot study. J Palliat Care. 2000;16(3):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germino B, McCorkle R. Acknowledged awareness of life-threatening illness. Int J Nurs Stud. 1985;22(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(85)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristjanson LJ, Nikoletti S, Porock D, Smith M, Lobchuk M, Pedler P. Congruence between patients' and family caregivers' perceptions of symptom distress in patients with terminal cancer. J Palliat Care. 1998;14(3):24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobchuk MM, Kristjanson L, Degner L, Blood P, Sloan JA. Perceptions of symptom distress in lung cancer patients: I. congruence between patients and primary family caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14(3):136–146. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarna L, Brecht ML. Dimensions of symptom distress in women with advanced lung cancer: A factor analysis. Heart Lung. 1997;26(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh E. Symptom experience in Korean adults with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Symptom distress in newly diagnosed ambulatory cancer patients and as a predictor of survival in lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(6):423–431. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCorkle R, Dowd M, Ercolano E, et al. Effects of a nursing intervention on quality of life outcomes in post-surgical women with gynecological cancers. Psychooncology. 2009;18(1):62–70. doi: 10.1002/pon.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman Green D, Ercolano E, Dowd M, Schwartz P, McCorkle R. Quality of life among women after surgery for ovarian cancer. Palliative supportive care. 2008;6(3):239–247. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarna L. Correlates of symptom distress in women with lung cancer. Cancer Pract. 1993;1(1):21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northouse LL, Dorris G, Charron Moore C. Factors affecting couples' adjustment to recurrent breast cancer. Social science medicine. 1995;41(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00302-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarna L. Women with lung cancer: Impact on quality of life. Quality of life research. 1993;2(1):13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00642885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schag CA, Heinrich RL. Cancer rehabilitaiton evaluation system: CARES manual. Los Angeles: CARES Consultants; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schag CA, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Cancer inventory of problem situation; an instrument for assessing cancerpatient's rehabilitation needs. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1983;1:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheville A. Cancer-related fatigue. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2009;20(2):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman A, Given B, von Eye A, Gift A, Given C. Relationships among pain, fatigue, insomnia, and gender in persons with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(4):785–792. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.785-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]