Abstract

Purpose

While overall survival from gynecologic malignancies has greatly improved over the last 3 decades, required treatments can lead to multiple health issues for survivors. Our objective was to identify health concerns that gynecologic cancer survivors face.

Methods

A systematic, stratified sample of women with gynecologic malignancies was surveyed for 18 health issues occurring before, during, or after treatment. The impact of clinical features and treatment modality on health issues was assessed through multivariate logistic regression models.

Results

Of 2,546 surveys mailed, 622 were not received by eligible subjects secondary to invalid address, incorrect diagnosis, or death. Thus, 1,924 survivors potentially received surveys. Of the 1,029 surveys (53.5%) completed, median age was 59 years; diagnoses included 29% cervical, 26% endometrial, 26% ovarian/primary peritoneal/fallopian tube, 12.1% vulvar, and 5.4% vaginal cancers. The most frequently reported health issues included: fatigue (60.6%), sleep disturbance (54.9%), urinary difficulties (50.9%), sexual dysfunction (48.4%), neurologic issues (45.4%), bowel complaints (42.0%), depression (41.3%), and memory problems (41.2%). These rankings were consistent with patients’ self-reported rankings of “highest impact” personal issues. After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, multivariate analyses revealed treatment modality impacted the odds of experiencing a given health issue.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates gynecologic cancer survivors experience a high frequency of health conditions and highlights the association between treatment modality and specific health concerns.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

The study findings highlight the multiple health concerns experienced by gynecologic cancer survivors and suggest the potential for developing interventions to mitigate these concerns in survivorship.

Keywords: Gynecologic Malignancy, Survivorship, Health Issues, Quality of Life, Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Currently, there are an estimated one million gynecologic cancer survivors in the United States [1]. Overall survival from gynecologic cancers has increased greatly over the last three decades [2]. This improvement is most pronounced among women with early stage uterine, ovarian, and cervical cancer, where cure is possible through tailored combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation. However, the treatments employed can lead to myriad health concerns for survivors. Further, after completion of cancer therapy, cancer survivors face increased risk for co-morbid conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, endocrine dysfunction, and general health decline [3, 4]. This growing population of gynecologic cancer survivors represents a critical group to study due to health issues that may impact their overall health and well-being.

Although research exists exploring the psychosocial impact of cancer treatment on this population [5–7], there is little work detailing the physical issues and conditions that impact gynecologic survivor health [8–12]. Available literature has been issue-specific (ie. lymphedema) or focused by cancer type [8, 13]. To date, there has not been a comprehensive survey to address each health issue that gynecologic cancer survivors potentially face.

The objective of this study was to identify current health-related issues faced by gynecologic cancer survivors. Health-related concerns included general medical problems and those related to consequences of treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population and Study Design

As part of an M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved study, women with gynecologic cancers seen at our institution between January 1, 1997 and June 1, 2007 were identified through the tumor registry. The National Cancer Institute’s definition of survivor was utilized, including patients from the time of cancer diagnosis throughout the remainder of life [14]. Survivors had to be at least 18 years of age at the time of enrollment, able to read and write in English, and live in the United States. Women with pre-invasive gynecologic disease were excluded. To improve response rate, subjects were excluded if the date of last institutional contact was greater than five years prior to study activation date.

A list of 6,295 patients was generated from the tumor registry. Sampling was stratified by primary cancer site with a goal of 400 patients with each major gynecologic cancer. For cancers with less than 400 cases during the study period (vulvar, vaginal, fallopian tube), all patients were included. For the common gynecologic cancers (uterine, ovarian/primary peritoneal, cervical), a systematic sample was performed. The interval of the systematic sample was chosen based on the number of eligible patients to invite 400 participants per cancer type. Of note, the sample number for cervical cancer was increased to 800 subjects, given known challenges in collecting patient-reported outcomes in this population [15].

Prospective participants were mailed survey materials with a unique linking identifier. Survey packets included the study questionnaire and cover letter stating that completion of the questionnaire implied informed consent. Subjects were given the opportunity to opt out. Non-responders were contacted approximately four weeks after mailing by the study manager to offer questionnaire completion by phone or during an upcoming clinic visit.

Instrument Design

The study questionnaire was developed internally by the principal investigator, collaborators, survivors, clinicians, and nurses. The questionnaire included demographic and clinical information. Clinical responses were verified through the electronic medical record.

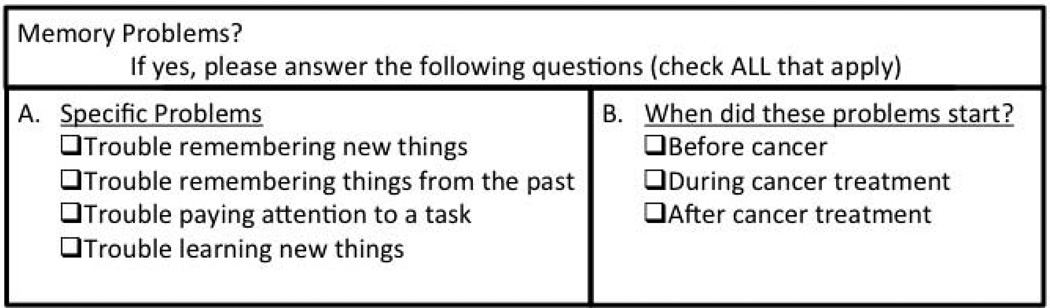

The remainder of the questionnaire consisted of a checklist regarding current health issues affecting the survivor. Health issues were selected based on literature in other cancer sites as well as upon clinical experience. Concerns included general medical problems such as cardiac and endocrine dysfunction, as well as potential complications of cancer treatment including genitourinary and neurologic dysfunction. A sample item from the questionnaire is shown in Figure 1. Survivors were asked to clarify details related to each health concern and whether it started before, during, or after cancer treatment. Responders ranked their top three health concerns and space was provided to write in other issues of importance.

Figure 1. Sample item from questionnaire.

The questionnaire explored a wide range of health issues in gynecologic cancer survivors. This item demonstrates description of specific memory issues experienced by the patient as well as clarification of timing of onset of these issues.

The questionnaire was administered to 20 patients attending the gynecology clinic prior to study onset to assess face validity of the instrument and identify necessary modifications prior to formal data collection. A copy of the questionnaire is available from the authors by request.

Statistical Analysis

Overall prevalence of given health issues before, during, and after cancer treatment was determined. Multivariate logistic regression models were constructed with backwards-stepwise elimination to assess the impact of covariates on the presence of health issues. SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL) was utilized for all analyses. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participation

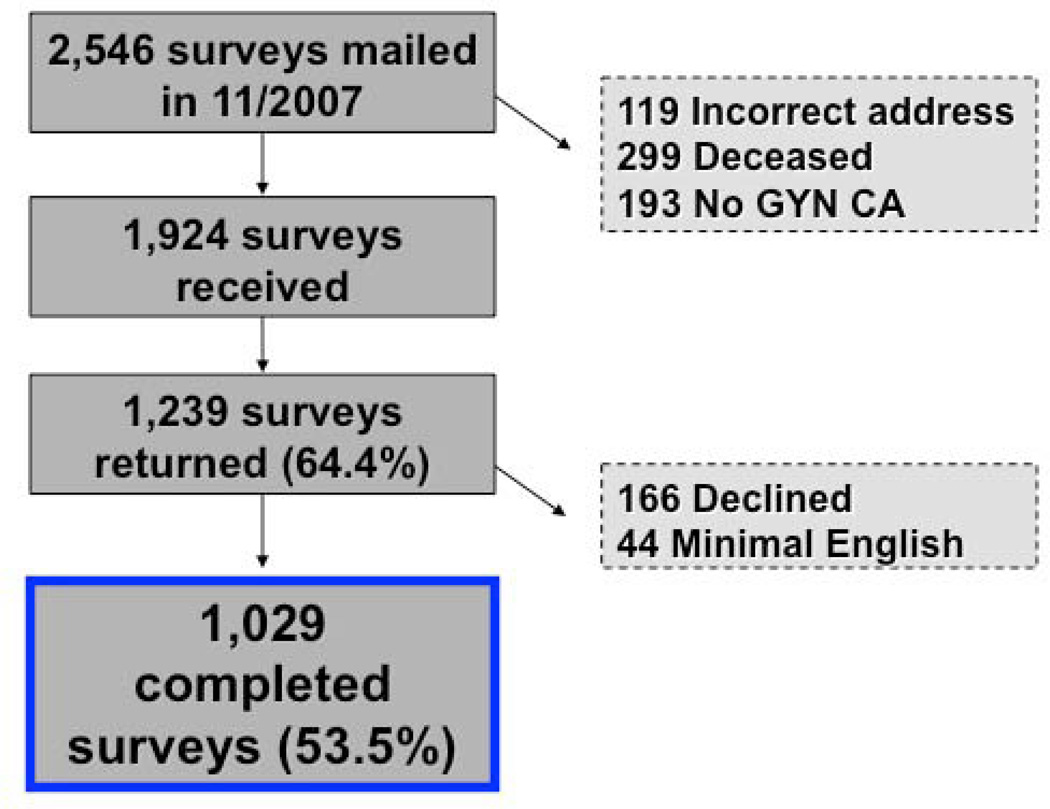

Figure 2 describes the participation of gynecologic cancer survivors in this survey study. The total number of responses was 1,239 (64.4%). One hundred sixty-six declined to complete the survey and 44 were unable to complete the survey secondary to inability to read and/or write English. Thus, 1,029 completed questionnaires (53.5%) were available for analysis.

Figure 2. Flow chart outlining gynecologic cancer survivor participation and inclusion.

Surveys were sent to 2,546 gynecologic cancer survivors. Of those, 1,924 surveys were received by subjects who met the inclusion criteria. The total number of responses was 1,239 (64.4%). One hundred sixty-six declined to complete the survey and 44 were unable to complete the survey secondary to inability to read and/or write English. Thus, 1,029 valid completed questionnaires (53.5%) were available for analysis. GYN CA; Gynecologic cancer

Demographics/Clinical

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the responders are described in Table 1. Median age was 59 years; median time from diagnosis was 4.9 years. The proportion of responders with the three most common gynecologic cancers was well balanced. Subjects received a variety of treatments and treatment combinations, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of respondents (N=1,029)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, median years (mean) | 59.0 (58.3) |

| Range | 22 – 102 |

| BMI1, median kg/m2 (mean) | 26.6 (28.2) |

| Range | 16.3 – 96.1 |

| Time from diagnosis, median years (mean) | 4.9 (7.1) |

| Range | 0.1 – 57.6 |

| n(%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 826 (80.3) |

| Hispanic | 113 (11.0) |

| Black | 56 (5.4) |

| Asian | 24 (2.3) |

| Other | 4 (0.4) |

| Marital status2 | |

| Married/Living with partner | 651 (63.3) |

| Separated/Divorced | 173 (16.8) |

| Widowed | 140 (13.6) |

| Never married | 64 (6.2) |

| Insurance status3 | |

| Medicare | 371 (36.1) |

| Medicaid | 35 (3.4) |

| Private Insurance | 488 (47.4) |

| Government Insurance | 32 (3.1) |

| Other | 17 (1.7) |

| No insurance | 64 (6.2) |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| Cervical | 303 (29.4) |

| Ovarian/primary peritoneal | 270 (26.2) |

| Endometrial | 269 (26.1) |

| Vulvar | 125 (12.1) |

| Vaginal | 56 (5.4) |

| Other | 6 (0.6) |

| Treatment modalities received4 | |

| Surgery alone | 340 (33.0) |

| Chemotherapy alone | 7 (0.7) |

| Radiation alone | 41 (4.0) |

| Surgery and chemotherapy | 225 (21.9) |

| Surgery and radiation | 141 (13.7) |

| Chemotherapy and radiation | 85 (8.3) |

| Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation | 187 (18.2) |

BMI, Body Mass Index

Missing data for 26 respondents

Missing data for 1 respondent

Missing data for 22 respondents

Missing data for 3 respondents

There were several significant differences between respondents and non-respondents. Respondents were older than non-respondents (median age 59 vs. 56 years, p=0.003). The proportion responding among whites (59.3%) and Asians (58.5%) was higher than the proportion responding among black (33.7%) and Hispanic (42.5%) patients (p<.001). In addition, the highest proportion of non-respondents was found among cervical (55.4%) compared to endometrial (41.2%), ovarian (37.2%), and other cancer survivors (40.7%; p<0.001).

Health-Related Issues Reported by Survivors

Gynecologic cancer survivors reported experiencing a variety of health-related issues. Table 2 lists the 18 health issues surveyed in order of most to least, regardless of whether problems started before, during, or after cancer treatment. The second column depicts the frequency of health issues that started during or after treatment. In a separate question, survivors were asked to list the three “most important” health concerns. Interestingly, the top three were sexual dysfunction, bowel-related concerns, and urinary difficulties.

Table 2.

Health-related issues reported by gynecologic cancer survivors in order of most to least prevalent

| Health Issues | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Before, during, and after treatment |

N (%) | During and after treatment |

N (%) |

| 1 | Fatigue | 624 (60.6) | Fatigue | 456 (44.3) |

| 2 | Sleep disturbance | 565 (54.9) | Sexual dysfunction | 367 (35.7) |

| 3 | Urinary dysfunction | 524 (50.9) | Sleep disturbance | 363 (35.3) |

| 4 | Sexual dysfunction | 498 (48.4) | Neurologic symptoms | 362 (35.2) |

| 5 | Neurologic symptoms | 467 (45.4) | Urinary dysfunction | 340 (33.0) |

| 6 | Bowel problems | 432 (42.0) | Bowel problems | 321 (31.2) |

| 7 | Depression | 425 (41.3) | Memory problems | 317 (30.8) |

| 8 | Memory problems | 424 (41.2) | Depression | 272 (26.4) |

| 9 | DJD | 374 (36.3) | Anxiety | 199 (19.3) |

| 10 | Cardiac problems | 344 (33.4) | Leg swelling/Lymphedema | 181 (17.6) |

| 11 | Anxiety | 329 (32.0) | Osteoporosis | 162 (15.7) |

| 12 | Osteoporosis | 274 (26.6) | DJD | 158 (15.4) |

| 13 | Bone fracture | 274 (26.6) | Cardiac problems | 118 (11.5) |

| 14 | Leg swelling/Lymphedema | 252 (24.5) | Bone fracture | 104 (10.1) |

| 15 | Thyroid problems | 232 (22.5) | Thyroid problems | 85 (8.3) |

| 16 | Diabetes | 142 (13.8) | Diabetes | 68 (6.6) |

| 17 | Reproductive issues | 128 (12.4) | Reproductive issues | 63 (6.1) |

| 18 | Renal dysfunction | 80 (7.8) | Renal dysfunction | 60 (5.8) |

DJD, Degenerative Joint Disease;

Impact of Treatment on Health-Related Issues

To assess impact of disease site and treatment modality on health issues, analyses were performed on health issues that occurred during or after treatment. Multivariate logistic regression models were created to assess the impact of clinical and demographic variables on the presence of each health concern. The following variables were included in regression models for each health concern: age (at survey response), body mass index, current smoking status, race, marital status, cancer disease site, time since diagnosis, point in disease spectrum (primary treatment, remission/no treatment, or treatment for recurrence), and treatment modality. The full results of the multivariate regression analyses for the 8 most commonly identified health issues are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression for top 8 health issues of gynecologic cancer survivors

| Fatigue | Sexual | Neurologic | Urinary | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variablea | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p |

| Age (≤ 40 yrs) | .00 | |||||||||||

| 41–50 yrs | 0.95 | 0.57, 1.58 | .83 | |||||||||

| 51–60 yrs | 0.62 | 0.38, 1.00 | .05 | |||||||||

| 61–70 yrs | 0.30 | 0.18, .51 | .00 | |||||||||

| 71+ yrs | 0.09 | 0.04, 0.17 | .00 | |||||||||

| BMI (ref=under/normal weight <25) | .09 | |||||||||||

| Overweight 25.0 – 29.9 | 1.30 | .92, 1.83 | .14 | |||||||||

| Obese 30.0 + | 1.44 | 1.03, 2.0 | .03 | |||||||||

| Current smoker (ref=no) | 1.54 | 1.01, 2.35 | .04 | 1.98 | 1.26, 310 | .00 | 2.02 | 1.30, 3.13 | .00 | 1.55 | 1.02, 2.37 | .04 |

| Race (ref=White) | ||||||||||||

| Black | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | ||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||

| Marital (ref=Married/partner) | ||||||||||||

| Not married/no partner | 0.44 | .32, .61 | .00 | 1.38 | 1.03, 1.85 | .03 | ||||||

| Cancer dx (ref=Endometrial) | ||||||||||||

| Cervical | ||||||||||||

| Ovarian | ||||||||||||

| Vaginal | ||||||||||||

| Vulvar | ||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||

| Time since dx (ref=<3 yrs) | .05 | .01 | .00 | |||||||||

| 3–5 yrs | 0.99 | .67, 1.46 | .96 | 1.28 | 0.84, 1.94 | .25 | 1.65 | 1.08, 2.53 | .02 | |||

| 5–10 yrs | 1.25 | .89, 1.76 | .20 | 1.72 | 1.19, 2.50 | .00 | 2.65 | 1.83, 3.85 | .00 | |||

| 10+ yrs | 1.71 | 1.12, 2.61 | .01 | 2.07 | 1.30, 3.31 | .00 | 2.86 | 1.83, 4.45 | .00 | |||

| Point in disease spectrum (ref=NED) | .00 | .01 | ||||||||||

| Recurrent disease | 2.25 | 1.47, 3.42 | .00 | 1.83 | 1.21, 2.75 | .00 | ||||||

| Primary treatment | 4.12 | 0.72, 23.6 | .11 | 2.01 | .43, 9.35 | .37 | ||||||

| Treatment modality (ref=Surgery) | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | ||||||||

| Surgery, chemotherapy | 3.45 | 2.34, 5.08 | .00 | 1.57 | 1.04, 2.36 | .03 | 4.04 | 2.68, 6.10 | .00 | 0.68 | 0.45,1.04 | .08 |

| Surgery, radiation | 1.83 | 1.19, 2.80 | .01 | 2.29 | 1.43, 3.67 | .00 | 1.80 | 1.12, 2.89 | .01 | 1.85 | 1.21,2.83 | .00 |

| Chemotherapy, radiation | 3.21 | 1.92, 5.38 | .00 | 2.05 | 1.18, 3.56 | .01 | 2.72 | 1.58, 4.67 | .00 | 2.49 | 1.48, 4.18 | .00 |

| Surgery, chemo, radiation | 4.01 | 2.68, 6.00 | .00 | 3.29 | 2.16, 5.01 | .00 | 5.93 | 3.89, 9.03 | .00 | 2.03 | 1.37, 3.02 | .00 |

| Radiation only | 1.73 | 0.87, 3.44 | .12 | 3.36 | 1.49, 7.62 | .02 | 1.10 | 0.48, 2.54 | .82 | 2.10 | 1.06, 4.14 | .03 |

| Chemotherapy only | 0.57 | 0.07, 4.81 | .60 | 1.21 | 0.20, 7.17 | .83 | 1.86 | 0.35, 9.91 | .47 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 1.0 |

| Hormonal therapy | 0.75 | 0.06, 10.1 | .83 | 0.80 | 0.07, 9.10 | .86 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 1.0 |

| Sleep | Bowel | Memory | Depression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variablea | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p |

| Age (ref = ≤ 40 yrs) | .00 | .00 | .00 | |||||||||

| 41–50 yrs | 1.30 | 0.77, 2.19 | .33 | 0.84 | 0.48, 1.46 | .54 | .77 | .46, 1.30 | .33 | |||

| 51–60 yrs | 0.94 | 0.57, 1.53 | .80 | 0.59 | 0.35, 1.00 | .05 | .65 | .40, 1.07 | .09 | |||

| 61–70 yrs | 0.70 | 0.42, 1.16 | .17 | 0.37 | 0.21, 0.64 | .00 | .43 | .26, .73 | .00 | |||

| 71+ yrs | 0.51 | 0.29, 0.89 | .02 | 0.27 | 0.15, 0.49 | .00 | .32 | .18, .57 | .00 | |||

| BMI (ref=under/normal weight <25) | .10 | |||||||||||

| Overweight 25.0 – 29.9 | .74 | 0.53, 1.05 | .10 | |||||||||

| Obese 30.0 + | .71 | 0.50, 1.00 | .05 | |||||||||

| Current smoker (ref=no) | 1.95 | 1.24, 3.06 | .01 | 1.77 | 1.12, 2.82 | .02 | 1.46 | 0.94, 2.26 | .09 | |||

| Race (ref=White) | .04 | .05 | ||||||||||

| Black | 1.74 | 0.96, 3.15 | .07 | 1.67 | 0.91, 3.09 | .10 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.67 | 1.08, 2.59 | .02 | 1.27 | 0.80, 2.02 | .31 | ||||||

| Other | 0.87 | 0.39, 1.91 | .72 | 2.41 | 1.13, 5.11 | .02 | ||||||

| Marital (ref=Married/partner) | ||||||||||||

| Not married/no partner | ||||||||||||

| Cancer dx (ref=Endometrial) | .05 | |||||||||||

| Cervical | 1.51 | 0.98, 2.33 | .06 | |||||||||

| Ovarian | 1.52 | 0.93, 2.49 | .10 | |||||||||

| Vaginal | 2.75 | 1.44, 5.29 | .00 | |||||||||

| Vulvar | 1.10 | 0.62, 1.94 | .74 | |||||||||

| Other | 1.24 | 0.20, 7.54 | .82 | |||||||||

| Time since dx (ref=<3 yrs) | .00 | .00 | .04 | |||||||||

| 3–5 yrs | 0.95 | 0.63. 1.42 | .80 | 2.41 | 1.58, 3.69 | .00 | 1.03 | .67, 1.57 | .91 | |||

| 5–10 yrs | 1.63 | 1.15, 2.31 | .01 | 2.16 | 1.46, 3.19 | .00 | 1.32 | .91, 1.93 | .14 | |||

| 10+ yrs | 2.19 | 1.41, 3.39 | .00 | 2.41 | 1.49, 3.92 | .00 | 1.87 | 1.18, 2.95 | .01 | |||

| Point in disease spectrum (ref=NED) | ||||||||||||

| Recurrent disease | ||||||||||||

| Primary treatment | ||||||||||||

| Treatment modality (ref=Surgery) | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | ||||||||

| Surgery, chemotherapy | 3.07 | 2.08, 4.52 | .00 | 2.50 | 1.47, 4.25 | .00 | 2.90 | 1.94, 4.33 | .00 | 1.92 | 1.27, 2.89 | .00 |

| Surgery, radiation | 1.85 | 1.18, 2.91 | .01 | 4.54 | 2.79, 7.39 | .00 | 0.97 | 0.58, 1.60 | .89 | 1.26 | 0.77, 2.07 | .35 |

| Chemotherapy, radiation | 2.65 | 1.56, 4.50 | .00 | 4.00 | 2.26, 7.08 | .00 | 2.24 | 1.24, 4.05 | .01 | 2.41 | 1.40, 4.17 | .00 |

| Surgery, chemo, radiation | 2.82 | 1.88, 4.24 | .00 | 5.08 | 3.28, 7.89 | .00 | 2.64 | 1.74, 4.03 | .00 | 1.79 | 1.17, 2.74 | .01 |

| Radiation only | 2.20 | 1.07, 4.52 | .03 | 2.75 | 1.30, 5.81 | .01 | 1.01 | 0.41, 2.47 | .99 | 1.56 | 0.70, 3.44 | .27 |

| Chemotherapy only | 0.49 | 0.05, 4.33 | .52 | 2.02 | 0.36, 11.4 | .43 | 1.18 | 0.21, 6.64 | .85 | 0.62 | 0.07, 5.33 | .66 |

| Hormonal therapy | 1.63 | 0.14, 19.1 | .70 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 1.0 | 1.61 | 0.14, 18.4 | .70 | 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00 | 1.0 |

The following variables were included in all regression models: age, BMI, smoking status, race, marital status, cancer disease site, time since cancer diagnosis, point in disease spectrum, and treatment modality.

Treatment modality was consistently found to have a significant impact on the most commonly experienced health concerns (p≤.001). Indeed, only degenerative joint disease, cardiac issues, bone fracture, thyroid problems, diabetes, and infertility were not significantly associated with the type of treatment received. In general, as compared to patients treated with surgery alone, patients treated with multi-modality therapy had higher odds of the surveyed health issues. Specifically, patients who underwent surgery, chemotherapy and radiation were the most likely to experience problems with fatigue (HR=4.01, 95%CI [2.68, 6.00], p≤.001), sexual dysfunction (HR=3.29, 95%CI [2.16, 5.01], p≤.001), neurologic symptoms (HR=5.93, 95%CI [3.89, 9.03], p≤.001), bowel complaints (HR=5.08, 95%CI [3.28, 7.89], p≤.001), osteoporosis (HR=2.36, 95%CI [1.37, 4.05], p≤.001), and lymphedema (HR=4.36, 95%CI [2.60, 7.20], p≤.001). Patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation were the most likely to experience urinary problems (HR=2.49, 95%CI [1.48, 4.18], p≤.001) and depression (HR=2.41, 95%CI [1.40, 4.17], p≤.001). Treatment with both surgery and chemotherapy was most highly associated with memory difficulties (HR=2.90, 95%CI [1.94, 4.33], p≤.001), sleep disturbance (HR=3.07, 95%CI [2.08, 4.52], p≤.001), and anxiety (HR=2.35, 95%CI [1.50, 3.68], p≤.001).

We also examined the influence a subset of covariates on the top 8 health concerns stratified by cancer disease site. Across cancer disease sites, treatment modality was associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing health concerns (detailed data provided in Supplemental Tables 1–9). For ovarian cancer survivors, treatment modality was associated with increased likelihood of fatigue (p<.001), neurologic symptoms (p=.001), and memory problems (p=.002). For cervical cancer survivors, treatment modality was associated with an increased risk of sexual dysfunction (p=.03), bowel problems (p=.001), neurologic symptoms (p=.001) and depression (p=.01). For endometrial cancer survivors, treatment modality was associated with an likelihood of fatigue (p=.001), neurologic symptoms (p=.001), urinary dysfunction (p=.006), and bowel problems (p<.001).

DISCUSSION

Despite successful treatment of their cancer, gynecologic cancer survivors surveyed endorsed a high proportion of health issues. These concerns included general medical problems and potential adverse effects of treatment. To our knowledge, this is one of the most comprehensive prospective surveys of the health needs of gynecologic cancer survivors.

In the National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship, the Centers for Disease Control and the Livestrong Foundation promoted identification of factors associated with ongoing health concerns of cancer survivors to effectively address cancer survivorship and improve quality of life after diagnosis and treatment [16]. Further, the Institute of Medicine recognized cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer treatment and recommended development of a plan to improve clinical care and outcomes of survivors [17]. Our study responds to this call to action by providing essential information regarding health issues encountered by gynecologic cancer survivors.

Along with emphasis by government and advocacy organizations, patients have endorsed the identification of health issues after cancer treatment as a priority. In a study of the information needs of gynecologic cancer survivors, Papadakos and colleagues found that participants selected adverse effects and disadvantages of treatment among the highest priority discussion topics [18]. The current study yields specific details that can be provide to patients about how treatment affects future health.

The most prevalent health issues across all participants were fatigue and sleep disturbance, defined as the inability to fall asleep or stay asleep through the night. Although associated with all treatment modalities, these issues were especially prevalent in survivors who received combination therapy. Cancer-related fatigue and sleep disturbance are almost universally reported by patients receiving treatment and may persist after therapy completion [19]. It is challenging to address fatigue and sleep disturbance as separate health issues versus symptoms of other conditions including depression or anxiety. Further, since providers often consider these issues as a normal reaction to cancer diagnosis and treatment, there has been limited proactive intervention [20]. In a small feasibility study, Donnelly and colleagues randomized patients with gynecologic cancers to a physical activity and behavioral change intervention versus standard care. Over 6 months, there was a slight improvement in fatigue by the validated Multi-dimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form. These findings require validation in a larger population [21].

Treatment combinations including radiation correlated with endorsement of sexual dysfunction and urinary difficulties. The overall prevalence of sexual dysfunction, including lack of desire, pain with intercourse, and inability to achieve orgasm, was consistent with the upper end of ranges reported for women without cancer [22, 23]. Sexual dysfunction has been analyzed in gynecologic cancer, especially among cervical cancer survivors. Radiation therapy (compared to radical surgery) has been associated with sexual dysfunction among gynecologic cancer survivors [24, 13]. In the current study, we found that sexual dysfunction was an issue for patients with all types of gynecologic cancers, regardless of history of radiation. Despite adequate evidence that this is a serious health concern, it appears that sexual dysfunction is often overlooked. A recent survey revealed that over 40% of breast and gynecologic cancer survivors were interested in participation in a sexual health program, although only 7% addressed this issue with a provider [25].

In our questionnaire, urinary problems were defined as leaking urine with cough or sneeze, feelings of urgency, and frequent urinary tract infections. These issues were found primarily in survivors who received radiation. Few studies have explored the impact of urinary dysfunction on quality of life of gynecologic cancer survivors. A population-based cross-sectional survey of 176 gynecologic cancer survivors and 521 controls revealed reduced quality of life scores in patients with urinary incontinence [26]. In an associated study, there was no difference in the urinary incontinence prevalence between healthy controls and gynecologic cancer survivors, although impact of radiation treatment was not addressed [27].

In our study, chemotherapy was closely associated with the experience of cognitive difficulties including short- and long-term memory loss, attention deficits, and difficulty learning new information. This is consistent with findings in women treated for breast cancer, including chemotherapy-induced changes in memory, attention, and psychomotor function [28]. Proposed mechanisms for chemotherapy-related cognitive dysfunction include demyelination, microvascular injury, and intracranial inflammatory responses [29]. A recent study in patients treated with chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer by Deprez and colleagues found changes in the cerebral white matter tissue organization that correlated to cognitive dysfunction [30]. Results in patients with ovarian cancer have been conflicting. In a study of 27 patients with advanced ovarian cancer, 80% demonstrated decline in one marker of cognitive impairment. However, Hensley and colleagues reported that markers remained stable or improved over time during therapy [31]. While it appears that patients may report cognitive issues after chemotherapy, these complaints are not necessarily supported by data from cognitive testing [32, 33]. Our findings rely solely on self-report, which may explain the high proportion of survivors with memory complaints compared to studies utilizing objective measurements.

Peripheral neurologic symptoms including numbness, tingling, and hearing problems, were associated with treatment incorporating chemotherapy. These symptoms are well-known side effects of chemotherapy and are often dose-limiting toxicities. The primary chemotherapeutic compounds used for gynecologic malignancies, taxane- and platinum-based treatment, are amongst the most common causes of peripheral neuropathy [34]. Thus far, the majority of literature regarding neurologic symptoms experienced among gynecologic cancer patients has been obtained from patients participating in treatment trials [35, 36]. Little data are available regarding the incidence of residual neurologic symptoms after therapy completion. A retrospective analysis of ovarian cancer patients that participated in the MITO-4 (Multicenter Italian Trial of Ovarian Cancer) trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel found that 15% experienced persistent neuropathy symptoms 6 months after treatment [37]. Another study of 49 early stage ovarian cancer survivors found that 39% experienced residual neurotoxicity [38]. Prevention of these adverse events at the time of chemotherapy administration would be ideal, however, use of neuro-protective agents has demonstrated mixed success [34, 39].

Given the impact of disease site on health concerns in the multivariate analysis, we examined the influence of specific covariates on top health concerns stratified by cancer disease site. Although we found the prevalence of top health concerns differed across disease sites, key health concerns were repetitively noted within each group of cancer survivors. Further, treatment modality was consistently associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing these health issues.

The strengths of this study lie in the large number of survivors that participated. We were able to attain a reasonable response rate due to our inclusion criteria and utilization of a structured follow-up plan for non-responders. The over-sampling of cervical cancer resulted in an equivalent number of subjects responding among the three most common cancers. Cervical cancer patients traditionally have lower socioeconomic indicators, including lower education, lower levels of employment, fewer financial resources, difference in primary language, lower health literacy and lower literacy levels. We can speculate that these factors all have, en masse, contributed to lower response rates due to apprehension of the medical care system, competing demands for time, as well as lower reading comprehension levels to complete optional surveys [15].

Although we did not utilize validated instruments, this survey allowed us to query a broad range of potential health issues. The use of multiple, multi-question validated instruments would have limited the expanse of the study by creating a larger burden on respondents. This survey was meant to create a broad base for future focused research efforts and interventions; therefore, use of self-reported issues is reasonable. Interestingly, specific issues previously studied in gynecologic cancer survivors, such as lymphedema [8], were endorsed by a modest proportion of patients in our study. This finding is likely related to our exploration of psychosocial issues not studied previously in this setting. The importance of these issues is underscored by the fact that patients ranked these specific concerns as paramount.

The data generated from this study must be interpreted with caution given the limitations inherent to the study design. Response bias may be an issue as patients were asked to remember if health concerns occurred before their diagnosis and treatment for cancer. To attempt to mitigate this limitation, responses were intermittently verified in the medical record to confirm validity. The median time from diagnosis to survey participation was approximately 5 years, which may have helped to minimize response bias. The health concern assessed may be related to a variety of different factors other than cancer treatment. We performed a multivariate analysis to attempt to identify factors outside of treatment that would impact occurrence of health concerns, however, there may be factors of importance that were not included in the analysis. The details provided about each of the health concerns were often limited to the organ system without obtaining additional detail about the symptom specifics. Further, we did not assess the severity of the health issues. Certainly, there may be health concerns which are highly prevalent but not severe enough to warrant intervention. Prior to creation of interventions, additional study will be necessary on identified health issues to determine which should be prioritized. Once a health concern is chosen for further evaluation, we will assess severity of distress and obtain further details that will guide intervention.

Gynecologic cancer survivors experience a broad array of health issues before, during, and after cancer treatment. While multi-modality therapy has improved survival and outcomes among patients with gynecologic malignancies, it is also associated with higher odds of experiencing several significant health issues. As this population continues to grow, it is critical to address issues that may be preventable and counsel patients regarding potential long-term medical issues related to their disease and treatments employed against their cancer. The information obtained through this survey provides a foundation for future research and may directly impact the current care of gynecologic cancer survivors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding: This study and/or study investigators were funded by the following grants –

National Institutes of Health 5T32 CA10164202 T32 Training Grant

National Institutes of Health K12CA088084 K12 Calabresi Scholar Award

National Institutes of Health 2P50CA098258-06 SPORE in Uterine Cancer

National Institutes of Health 2P50CA083639 SPORE in Ovarian Cancer

National Institutes of Health P30CA016672 MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altekruse S, Kosary C, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, et al. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010. [Accessed February 18 2011]. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. doi:355/15/1572 [pii] 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stull VB, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W. Lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors: designing programs that meet the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. J Nutr. 2007;137(1 Suppl):243S–248S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.243S. doi:137/1/243S [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson B, Lutgendorf S. Quality of life in gynecologic cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 1997;47(4):218–225. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.47.4.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell B, Smith SL, Cullinane CA, Melancon C. Psychological well being and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Cancer. 2003;98(5):1061–1071. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, Hunt GE, Stenlake A, Hobbs KM, et al. Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104(2):381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beesley V, Janda M, Eakin E, Obermair A, Battistutta D. Lymphedema after gynecological cancer treatment : prevalence, correlates, and supportive care needs. Cancer. 2007 doi: 10.1002/cncr.22684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lockwood-Rayermann S. Survivorship issues in ovarian cancer: a review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(3):553–562. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.553-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz PN, Beck ML, Stava C, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R. Health profiles in 5836 long-term cancer survivors. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(4):488–495. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz PN, Stava C, Beck ML, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R. Ethnic/racial influences on the physiologic health of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;100(1):156–164. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salani R. Survivorship planning in gynecologic cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(2):389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR, Munsell MF, Jhingran A, Wharton JT, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7428–7436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996. doi:23/30/7428 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. [Accessed November 28 2012];2012 http://www.cancer.gov/dictionary?cdrid=445089.

- 15.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Kagawa-Singer M, Tucker MB, et al. Cervical cancer survivorship in a population based sample. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(2):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. CDC Lance Armstrong Foundation. 2004 Apr [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–5116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadakos J, Bussiere-Cote S, Abdelmutti N, Catton P, Friedman AJ, Massey C, et al. Informational needs of gynecologic cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prue G, Rankin J, Allen J, Gracey J, Cramp F. Cancer-related fatigue: A critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(7):846–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.026. doi:S0959-8049(05)01134-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savard J, Morin CM. Insomnia in the context of cancer: a review of a neglected problem. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):895–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly CM, Blaney JM, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin JP, Campbell A, McCrum-Gardner E, et al. A randomised controlled trial testing the feasibility and efficacy of a physical activity behavioural change intervention in managing fatigue with gynaecological cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(3):618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.029. doi:S0090-8258(11)00426-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips NA. Female sexual dysfunction: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(1):127–136. 41–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D'Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5(2):357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00672.x. doi:JSM672 [pii] 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(4):937–949. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00362-6. doi:S0360301603003626 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Wroblewski K, Wenrich ER, et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors' sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/cncr.25832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skjeldestad FE, Rannestad T. Urinary incontinence and quality of life in long-term gynecological cancer survivors: a population-based cross-sectional study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(2):192–199. doi: 10.1080/00016340802582041. doi:905968359 [pii] 10.1080/00016340802582041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skjeldestad FE, Hagen B. Long-term consequences of gynecological cancer treatment on urinary incontinence: a population-based cross-sectional study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(4):469–475. doi: 10.1080/00016340801948326. doi:791207832 [pii] 10.1080/00016340801948326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, Cole B, Mott LA, Skalla K, et al. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):485–493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuxen MK, Hansen SW. Neurotoxicity secondary to antineoplastic drugs. Cancer Treat Rev. 1994;20(2):191–214. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deprez S, Amant F, Smeets A, Peeters R, Leemans A, Van Hecke W, et al. Longitudinal assessment of chemotherapy-induced structural changes in cerebral white matter and its correlation with impaired cognitive functioning. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(3):274–281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8571. doi:JCO.2011.36.8571 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hensley ML, Correa DD, Thaler H, Wilton A, Venkatraman E, Sabbatini P, et al. Phase I/II study of weekly paclitaxel plus carboplatin and gemcitabine as first-line treatment of advanced-stage ovarian cancer: pathologic complete response and longitudinal assessment of impact on cognitive functioning. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102(2):270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.042. doi:S0090-8258(05)01115-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Correa DD, Zhou Q, Thaler HT, Maziarz M, Hurley K, Hensley ML. Cognitive functions in long-term survivors of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(2):366–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.06.023. doi:S0090-8258(10)00474-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Correa DD, Hess LM. Cognitive function and quality of life in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.005. doi:S0090-8258(11)00895-X [pii] 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verstappen CC, Heimans JJ, Hoekman K, Postma TJ. Neurotoxic complications of chemotherapy in patients with cancer: clinical signs and optimal management. Drugs. 2003;63(15):1549–1563. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang HQ, Brady MF, Cella D, Fleming G. Validation and reduction of FACT/GOG-Ntx subscale for platinum/paclitaxel-induced neurologic symptoms: a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17(2):387–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cella D, Huang H, Homesley HD, Montag A, Salani R, De Geest K, et al. Patient-reported peripheral neuropathy of doxorubicin and cisplatin with and without paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced endometrial cancer: Results from GOG 184. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(3):538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pignata S, De Placido S, Biamonte R, Scambia G, Di Vagno G, Colucci G, et al. Residual neurotoxicity in ovarian cancer patients in clinical remission after first-line chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel: the Multicenter Italian Trial in Ovarian cancer (MITO-4) retrospective study. BMC cancer. 2006;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wenzel LB, Donnelly JP, Fowler JM, Habbal R, Taylor TH, Aziz N, et al. Resilience, reflection, and residual stress in ovarian cancer survivorship: a gynecologic oncology group study. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):142–153. doi: 10.1002/pon.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pace A, Giannarelli D, Galie E, Savarese A, Carpano S, Della Giulia M, et al. Vitamin E neuroprotection for cisplatin neuropathy: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;74(9):762–766. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d5279e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.