Abstract

Aim

Patient‐reported outcome (PRO) measures (PROMs) are standard measures in the assessment of colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment, but the range and complexity of available PROMs may be hindering the synthesis of evidence. This systematic review aimed to: (i) summarize PROMs in studies of CRC surgery and (ii) categorize PRO content to inform the future development of an agreed minimum ‘core’ outcome set to be measured in all trials.

Method

All PROMs were identified from a systematic review of prospective CRC surgical studies. The type and frequency of PROMs in each study were summarized, and the number of items documented. All items were extracted and independently categorized by content by two researchers into ‘health domains’, and discrepancies were discussed with a patient and expert. Domain popularity and the distribution of items were summarized.

Results

Fifty‐eight different PROMs were identified from the 104 included studies. There were 23 generic, four cancer‐specific, 11 disease‐specific and 16 symptom‐specific questionnaires, and three ad hoc measures. The most frequently used PROM was the EORTC QLQ‐C30 (50 studies), and most PROMs (n = 40, 69%) were used in only one study. Detailed examination of the 50 available measures identified 917 items, which were categorized into 51 domains. The domains comprising the most items were ‘anxiety’ (n = 85, 9.2%), ‘fatigue’ (n = 67, 7.3%) and ‘physical function’ (n = 63, 6.9%). No domains were included in all PROMs.

Conclusion

There is major heterogeneity of PRO measurement and a wide variation in content assessed in the PROMs available for CRC. A core outcome set will improve PRO outcome measurement and reporting in CRC trials.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, surgery, patient‐reported outcomes, core outcome set, systematic review

Introduction

The measurement of patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) has become standard in the assessment of colorectal cancer (CRC) treatments, and their use is recommended by funding and regulatory agencies 1. Many patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) have therefore been developed for a variety of purposes 2. Some are generic, and allow comparisons between patients with other conditions (e.g. SF‐36, EQ‐5D), others are designed for patients with cancer (e.g. EORTC QLQ‐C30, FACT‐G), and some are specific for CRC (e.g. EORTC‐CR29, FACT‐C). To add further complexity, each of these PROMs typically consists of a number of questions (items), which are often grouped together to represent similar concepts (scales). For example, two questions regarding activities of daily living and leisure activities in the EORTC QLQ‐C30 measure are grouped into a single ‘role function’ scale. There are therefore a multitude of ways to measure PROs to evaluate treatment for CRC, and this creates problems that may influence the conduct and clinical impact of trials.

Trials may use different PROMs 3, 4 making it impossible to synthesize data across trials or undertake meta‐analyses. The multiplicity of results available from trials means that it is difficult to interpret findings in the context of clinical practice because of a lack of familiarity with the number of measures, scales and items 2. For example, the scale ‘physical function’ exists in several different PROMs, but individual items in these scales vary considerably between questionnaires. This is confusing for clinicians, who may not be aware of the differences between PROMs, and it is likely to limit the meaningful use of the data in practice. Finally, the opportunities for measuring multiple outcomes may lead to selective reporting of significant findings. This can generate bias and influence clinical interpretation of trials 5.

A proposed solution to these issues are ‘core outcome sets’. Core outcomes are the minimum set of outcomes that patients and professionals agree should be measured in all trials of a certain condition 6. They aim to facilitate comparisons between trials and aid meta‐analysis by standardizing outcome measurement, including PROs. The use of core sets may also facilitate the clinical communication of data. Many core outcome sets have now been developed in different clinical areas, including rheumatology 7, paediatrics 8 and obstetrics 9, but not in CRC surgery. This systematic review aims to examine the measurement of PROs in CRC surgical studies, and use the data to inform the development of the core outcome set.

Method

A systematic review of prospective CRC surgical studies measuring PROs was undertaken to: (i) summarize PRO measurement in CRC surgical studies, and (ii) examine each PROM in detail and categorize analogous concepts into domains to inform the future development of a core outcome set.

Systematic search and data extraction

This systematic review adhered to a predefined protocol (available on request from the authors). Validated terms relating to ‘surgery’, ‘colorectal cancer’ and ‘prospective studies’ (Table 1) were used to search the OVID SP versions of MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A validated filter for ‘prospective studies’ was used because PRO data are typically collected prospectively. The search was limited to studies conducted in humans aged 18 years and over, reported in the English language between January 2009 and December 2010. Previous reviews have considered PROs of CRC surgery in terms of elderly patients 10, methodological challenges in measuring PROs in CRC 11, laparoscopic surgery 12, long‐term survivors 13, rectal cancer 3 and CRC before 2009 14. The studies identified in these reviews were included. All citations were collated with reference manager 12 (Thomson Reuters, New York city, New York, USA) and the duplicates removed.

Table 1.

OvidSP version of Medline search strategy

| Search criteria | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer | 1. exp Colonic Neoplasms/ |

| 2. exp Rectal Neoplasms/ | |

| 3. ((colorect$ or colon or colonic or rect$) adj3 (cancer$ or tumo?r$ or neoplasm$ or carcinoma$ or adenocarcinoma$ or malignan$)).tw. | |

| 4. or/1‐3 | |

| Surgery | 1. exp Specialties, Surgical/ |

| 2. surg$.tw. | |

| 3. operat$.tw. | |

| 4. intervention$.tw. | |

| 5. procedur$.tw. | |

| 6. resect$.tw. | |

| 7. or/1‐6 | |

| Randomized controlled trials/prospective studies | 1. randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. | |

| 3. randomized controlled trials.sh. | |

| 4. random allocation.sh. | |

| 5. double blind method.sh. | |

| 6. single‐blind method.sh. | |

| 7. or/1‐6 | |

| 8. exp animals/not human/ | |

| 9. 7 not 8 | |

| 10. clinical trial.pt. | |

| 11. exp clinical trials/ | |

| 12. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. | |

| 13. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. | |

| 14. placebos.sh. | |

| 15. placebo$.ti,ab. | |

| 16. random$.ti,ab. | |

| 17. research design.sh. | |

| 18. or/10‐17 | |

| 19. 18 not 8 | |

| 20. 19 not 9 | |

| 21. comparative study.sh. | |

| 22. exp evaluation studies/ | |

| 23. follow up studies.sh. | |

| 24. prospective studies.sh. | |

| 25. (control$ or prospective$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. | |

| 26. or/21‐25 | |

| 27. 26 not 8 | |

| 28. 27 not (9 or 20) | |

| 29. 9 or 20 or 28 |

Titles and abstracts of identified publications were screened by one researcher. If there was uncertainty about the eligibility of a publication the full paper was also accessed. Articles were included if they were original research papers reporting PROs of CRC surgery (curative or palliative), with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies, or systematic reviews of such publications. PROs were defined as end‐points provided by patients themselves and not interpreted by observers. Studies of nonbiomedical interventions (e.g. alternative medicine), palliative treatments that did not include a surgical component (e.g. palliative chemotherapy), screening studies, treatment of colorectal metastases and molecular and genetic prognostic studies were all excluded. Studies of more than one cancer site or of mixed benign and malignant disease were included provided the data for CRC patients was presented separately from that of the other diseases.

Data extraction included: participant demographics (number, age and gender); treatment received (surgery, neoadjuvant radiotherapy/chemoradiation and adjuvant chemotherapy); treatment intent (curative or palliative); the study design (randomized trial, case–control study, cohort study, cross‐sectional study, prospective case series or other design); the PRO questionnaire used; and the individual items included in each questionnaire. When the individual questionnaires were not available in publications, internet searches and direct contact with authors were used to obtain the information. All data were entered into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) database to facilitate data management and analyses. The data extraction was checked by a second reviewer (ROF) for a sample of included articles (n = 25) and any disagreements were discussed and resolved with the senior author (JMB).

Summary of PRO measurement in CRC surgery

The number of publications reporting each PROM was tabulated and descriptive statistics used to summarize PRO measurement. The popularity of PROMs was assessed by comparing their frequency of use in studies. A summary of each PROM is provided in terms of the numbers of items, scales and whether a total score was used. The distribution of items among PROMs was examined by calculating the median number and range of items per PROM. Questionnaires were categorized as: (i) generic (for use in all patients), (ii) cancer specific (for use in all cancer patients), (iii) CRC specific (for use in CRC patients), (iv) symptom specific (to assess a single symptom, e.g. pain), or (v) ad hoc.

Examination of PROs and domain categorization

Individual items from all questionnaires were extracted and formed into a long‐list before categorization into health domains by two researchers (RNW and JR). Both were kept masked as to which PRO questionnaire the items were derived from. Two patient representatives (JEJ and GS) and one consultant colorectal surgeon (AMP) subsequently checked this process. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved with the senior author (JMB).

Categorization was summarized using descriptive statistics to explore the distribution of items and PROMs between domains. The number of items included in each domain was counted, as were the number of PROMs from which they were sourced. The contribution of each source PROM was demonstrated by calculating the median number and range of items included from the measures.

Results

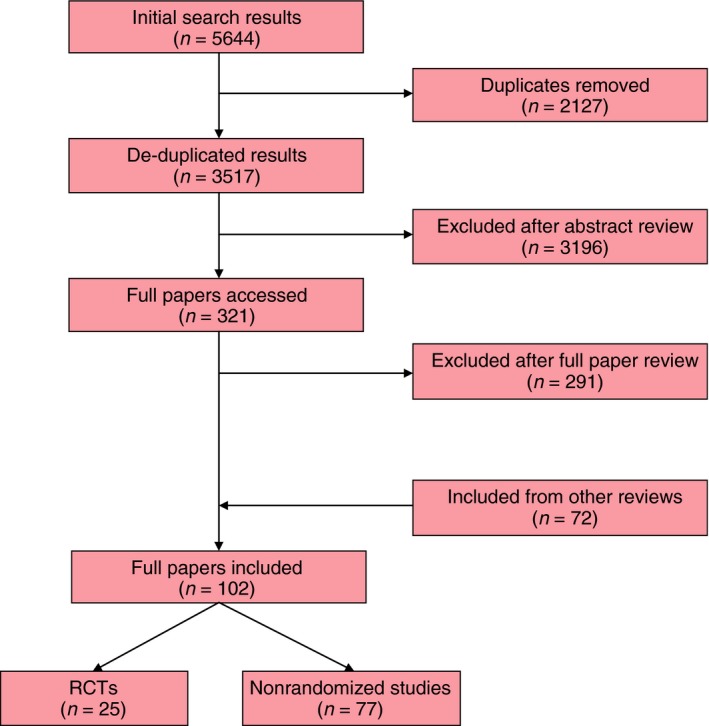

A total of 5644 titles and abstracts were identified, of which 2127 were duplicates. The remaining 3517 were screened and 29 original research articles included. In addition to this, six systematic reviews of PROs in CRC surgery identified a further 72 original research articles (Fig. 1). In total, 102 original publications including 25 randomized controlled trials (25%) and 77 nonrandomized studies (75%) reporting the outcome for 66 386 patients with CRC 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116 were included. The studies are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) diagram of studies considered for the systematic review.

Table 2.

Summary of included articles

| All studies (n = 102) | Randomized trials (n = 25) | Nonrandomized studies (n = 77) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 66 386 | 7172 | 59 214 |

| Age range of participants (years) | 18–99 | 29–89 | 18–99 |

| Number of participating centres (%) | |||

| Single | 58 (57) | 13 (52) | 45 (58) |

| Multiple | 44 (43) | 12 (48) | 32 (42) |

| IRB or ethical approval reported (%) | 52 (51) | 14 (56) | 38 (49) |

| Tumour site (%) | |||

| Colon | 10 (9) | 2 (8) | 7 (9) |

| Rectum | 54 (53) | 11 (44) | 44 (55) |

| Mixed colon and rectum | 38 (38) | 12 (48) | 26 (34) |

| Surgical approach (%) | |||

| Laparoscopy | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hand‐assisted laparoscopy | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Open | 5 (5) | 1 (4) | 4 (5) |

| Mixed | 13 (12) | 9 (36) | 5 (6) |

| Not reported or incomplete information reported | 83 (81) | 15 (60) | 67 (87) |

| Neoadjuvant treatmenta (%) | |||

| Radiotherapy alone | 20 (20) | 9 (36) | 11 (14) |

| Chemotherapy alone | 0 | 0 | 0v (0.0) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 22 (22) | 3 (12) | 18 (24) |

| None | 7 (7) | 1 (4) | 6 (8) |

| Not reported or incomplete information reported | 53 (51) | 12 (48) | 42 (54) |

| Adjuvant treatmenta (%) | |||

| Chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy | 56 (55) | 16 (64) | 40 (52) |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not reported or incomplete information reported | 46 (45) | 9 (36) | 37 (48) |

| Number of PROMs reported | |||

| 1 | 43 | 10 | 33 |

| 2 | 47 | 12 | 35 |

| 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

IRB, Institutional Review Board.

Some studies included patients with or without neoadjuvant therapy, some patients underwent different neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment within the same study.

Summary of PROM in CRC surgery

Fifty‐eight different PRO questionnaires were identified and these were reported 184 times in the included publications (Table 3). There were 23 (39.7%) generic questionnaires, four (6.9%) cancer‐specific questionnaires, 11 (19.0%) CRC‐specific questionnaires and 17 (29.3%) symptom‐specific questionnaires. Three ad hoc questionnaires (those devised specifically for the study) were not categorized.

Table 3.

Summary of identified patient‐reported outcome measures (questionnaires) (n = 58)

| Number of items | Number of scales | Overall score | Frequency (n = 184) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of generic questionnaire (n = 23) | ||||

| Short Form‐36 | 36 | 8 | No | 21 |

| EuroQol‐5D | 6 | 6 | Yes | 3 |

| Rotterdam Symptom Checklist | 35 | 4 | No | 3 |

| Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index | 36 | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Functional Difficulty Index | 15 | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Illness Impact Scale | 9 | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Visual Analogue Scale (overall health) | 1 | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Self‐rated healtha | – | – | – | 1 |

| Freiburger Illness Coping Strategies questionnairea | – | – | – | 1 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory‐18 | 18 | 3 | Yes | 1 |

| Constructed Meaning Scale | 8 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Surgical Recovery Score | 31 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Nottingham Health Profile | 45 | 6 | Yes | 1 |

| Duke Generic Instrument | 17 | 11 | Yes | 1 |

| Instrumental Activities of Daily Living | 7 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Profile of Moods States | 65 | 6 | Yes | 1 |

| Health and Activities Limitation Index | 8 | 2 | Yes | 1 |

| Health Utility Index | 7 | 7 | Yes | 1 |

| Spitzer Quality of Life Index | 5 | 5 | Yes | 1 |

| Global Quality of Lifea | – | – | – | 1 |

| Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnairea | – | – | – | 1 |

| Symptom Experience Scale | 24 | 6 | Yes | 1 |

| Ad hoc satisfaction questionnaireb | 6 | 6 | Yes | 1 |

| Name of cancer‐specific questionnaire (n = 4) | ||||

| EORTC QLQ‐C30 | 30 | 15 | No | 50 |

| Cancer‐related Health Worries Scale | 4 | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Quality of Life – Cancer Survivors | 41 | 4 | No | 1 |

| Cancer Problems in Living Scale | 31 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Name of disease‐specific questionnaire (n = 11) | ||||

| EORTC QLQ‐CR38 | 38 | 9 | No | 33 |

| Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Colorectal | 37 | 5 | Yes | 5 |

| Modified City of Hope Quality of Life – Ostomy | 41 | 6 | Yes | 2 |

| EORTC QLQ‐CR29 | 34 | 4 | No | 1 |

| University of Padova Bowel Function Questionnaire | 8 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Bowel Function Questionnaire | 8 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Bowel Problems Scale | 7 | 7 | No | 1 |

| Late Effects Normal Tissue – subjective, objective, management, analytic scalea | – | – | – | 1 |

| Quality of Life Index for Colostomy Patients | 23 | 3 | No | 1 |

| Colorectal Cancer Quality of Life | 62 | 4 | Yes | 1 |

| COloREctal Functional Outcome Questionnaire | 26 | 5 | Yes | 1 |

| Name of symptom‐specific questionnaire (n = 17) | ||||

| International Index of Erectile Function | 15 | 5 | Yes | 4 |

| Faecal Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire | 29 | 4 | No | 3 |

| Wexner Incontinence Scale | 5 | 0 | Yes | 3 |

| Visual Analogue Scale (pain) | 1 | 0 | Yes | 3 |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression | 20 | 6 | Yes | 3 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 14 | 0 | Yes | 2 |

| Holschneider Questionnaire | 8 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Internation Index of Erectile Function‐5 | 5 | 5 | Yes | 1 |

| Body Image Questionnaire | 10 | 2 | No | 1 |

| Body Image Scale | 10 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Faecal Incontinence Scoring System | 5 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptom Scale | 12 | 3 | Yes | 1 |

| Present Pain Intensity Index | 1 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Satisfaction with Sexual Function | 1 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Visual Analogue Scale (wound satisfaction) | 1 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Symptom Distress Scale | 15 | 0 | Yes | 1 |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory‐20 | 20 | 5 | No | 1 |

| Name of questionnaire (n = 3) | ||||

| Ad hoc QOL questionnaire Aa, b | – | – | – | 1 |

| Ad hoc QOL questionnaire Ba, b | – | – | – | 1 |

| Ad hoc QOL questionnaire Ca, b | – | – | – | 1 |

EORTC, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; QOL, quality of life.

Questionnaire not available.

PROM not validated.

Most questionnaires were reported only once (n = 40, 69.0%). The most frequently reported were the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ‐C30 (50 studies, 48%), the EORTC QLQ‐CR38 (33 studies, 32%) and the Medical Outcome Study Short Form‐36 (21 studies, 21%). The median number of items per PROM was 14, ranging from one [five PROMs: Visual Analogue Scale (overall, pain and wound satisfaction), Satisfaction with Sexual Function, and Present Pain Intensity Index)] to 65 (the Profile of Mood States). Some 159 scales were evident, and most PROMs (n = 48, 83%) included a total score.

Examination of PROs and domain categorization

Fifty (86.2%) full questionnaires were available. Reasons for unavailability were inability to obtain the questionnaires from authors or web searches (n = 6) or lack of an English language translation (n = 2). The 50 questionnaires comprised some 917 individual items, and were categorized into 51 domains as described above (Table 4). The full categorization is presented in Table S1. The domains comprising the most items were ‘anxiety’ (n = 85, 9.2%), ‘fatigue’ (n = 67, 7.2%) and ‘physical function’ (n = 63, 6.8%). The disease‐specific domains comprising most items were ‘faecal incontinence’ (n = 53, 5.7%) and ‘stoma problems’ (n = 52, 5.6%). Most domains (n = 27, 53%) contained 10 or more items.

Table 4.

Summary of domain categorization including number of items per domain, numbers of PROMs and median items per PROM

| PRO domain (n = 51) | Number of items (n = 917 (%) | Number of PROMs (n = 50) (%) | Median items per source PROM (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological domains | |||

| Anxiety | 85 (9.2) | 22 (44) | 2.5 (1–12) |

| Fatigue | 67 (7.2) | 21 (42) | 1.0 (1–23) |

| Depression | 47 (5.1) | 16 (32) | 1.5 (1–12) |

| Body image | 37 (4.0) | 13 (26) | 1.0 (1–10) |

| Frustration/irritability | 15 (1.6) | 7 (14) | 1.0 (1–9) |

| Outlook on life | 13 (1.4) | 5 (10) | 2.0 (1–6) |

| Self‐esteem | 11 (1.2) | 6 (12) | 2.0 (1–3) |

| Coping | 10 (1.1) | 6 (12) | 1.0 (1–3) |

| Spiritual | 7 (0.7) | 2 (4) | 3.5 (3–4) |

| Regret | 5 (0.5) | 2 (4) | 2.5 (1–4) |

| Control | 3 (0.3) | 3 (6) | 1.0 (1) |

| Functional domains | |||

| Physical function | 63 (6.8) | 19 (38) | 1.0 (1–9) |

| Role function | 51 (5.5) | 20 (40) | 2.0 (1–7) |

| Social function | 50 (5.4) | 22 (44) | 2.0 (1–8) |

| Sexual function | 44 (4.7) | 13 (26) | 1.0 (1–15) |

| Cognitive function | 30 (3.2) | 14 (28) | 1.0 (1–7) |

| Symptom domains | |||

| Faecal incontinence | 53 (5.7) | 12 (24) | 2.0 (1–27) |

| Stoma problems | 52 (5.6) | 5 (10) | 7.0 (7–21) |

| Pain | 50 (5.4) | 18 (36) | 1.5 (1–8) |

| Insomnia | 18 (1.9) | 13 (26) | 1.0 (1–4) |

| Appetite/eating problems | 17 (1.8) | 10 (20) | 1.5 (1–3) |

| Faecal frequency | 14 (1.5) | 8 (16) | 2.0 (1–3) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 12 (1.3) | 8 (16) | 1.0 (1–3) |

| Faecal Urgency | 11 (1.2) | 8 (16) | 1.0 (1–2) |

| Flatulence or gas | 11 (1.2) | 7 (14) | 1.0 (1–3) |

| Treatment problems | 11 (1.2) | 7 (14) | 1.0 (1–3) |

| Rectal blood or mucus | 10 (1.1) | 8 (16) | 1.0 (1–2) |

| Bloating | 7 (0.7) | 6 (12) | 1.0 (1–2) |

| Diarrhoea | 7 (0.7) | 7 (14) | 1.0 (1) |

| Tenesmus | 7 (0.7) | 4 (8) | 2.0 (1–2) |

| Constipation | 6 (0.6) | 5 (10) | 1.0 (1–2) |

| Shortness of breath | 5 (0.5) | 5 (10) | 1.0 (1) |

| Urinary frequency | 5 (0.5) | 3 (6) | 2.0 (1–2) |

| Faint or dizzy | 4 (0.4) | 4 (8) | 1.0 (1) |

| Hair problems | 4 (0.4) | 4 (8) | 1.0 (1) |

| Discrimination | 3 (0.3) | 3 (6) | 1.0 (1) |

| Dry mouth | 3 (0.3) | 3 (6) | 1.0 (1) |

| Menstruation | 3 (0.3) | 3 (6) | 1.0 (1) |

| Taste | 3 (0.3) | 3 (6) | 1.0 (1) |

| Duration of bowel movement | 2 (0.2) | 2 (4) | 1.0 (1) |

| Dyspepsia | 2 (0.2) | 2 (4) | 1.0 (1) |

| Dysphagia | 2 (0.2) | 1 (2) | 2.0 (2) |

| Dysuria | 1 (0.1) | 1 (2) | 1.0 (1) |

| Urinary incontinence | 1 (0.1) | 1 (2) | 1.0 (1) |

| Global domains | |||

| Global quality of life | 12 (1.3) | 9 (18) | 1.0 (1–2) |

| Self‐care | 10 (1.1) | 10 (20) | 1.0 (1) |

| Financial | 8 (0.9) | 5 (10) | 1.0 (1–4) |

| Satisfaction with care | 6 (0.6) | 1 (2) | 6.0 (6) |

| Information needs | 1 (0.1) | 1 (2) | 1.0 (1) |

There was little evidence of consistency between PROMs. No domains were measured in all the PROMs. The two domains that were best represented were ‘anxiety’ and ‘social function’, each measured by 22 (44%) PROMs. Otherwise, most domains (n = 39, 76%) were measured by less than a quarter of PROMs, highlighting further heterogeneity. There were two domains with a high median number of items included per PROM: ‘stoma problems’, which contained 52 items from only five PROMs (median seven items per PROM) and ‘satisfaction with care’, which featured six items from just one PROM. This may reflect specialization of PROMs, with some measures focusing on very specific concepts.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to summarize PRO measurement in current CRC surgical studies and categorize PRO items into analogous concepts to inform the development of a core outcome set. There was evidence of significant heterogeneity of PRO measurement in the included studies. Fifty‐eight different PROMs were used to assess patient experience of colorectal surgery. Most (n = 40, 69.0%) were only ever used once, and even the most common (EORTC QLQ‐C30) was measured in less than half of the studies. PROMs also varied greatly in terms of their content, with some as simple as a single item while others included up to 65. Most (52%) PROMs were not designed to be specific to CRC surgery or symptoms thereof, and although this may bring benefits in terms of comparison between diseases they may not be sensitive enough to issues that are of specific importance to patients with CRC. Over 900 individual questionnaire items were evident from 50 PROMs, and through a rigorous process, these were categorized into 51 ‘health domains’. This demonstrated a further lack of consistency, with no domains being measured in all the PROMs, and most health domains only being measured by less than a quarter of PROMs. All of this highlights potentially major questions for evidence synthesis and clinical interpretation of results in studies of CRC surgery, and demonstrates the need for a standardized core outcome set.

Other studies have highlighted the problem with outcome heterogeneity for clinical and PRO data. A recently published systematic review identified 194 studies of CRC surgery that measured 766 different clinical outcomes, with no single outcome reported in all 117. Even considering a seemingly simple outcome such as mortality, there were over 84 different ways in which this was defined and measured. The same problem has been highlighted in studies of oesophageal cancer surgery 118, where a review of 122 articles reported 210 unique complications and 10 different measures of operative mortality, and breast reconstruction following mastectomy for cancer 119, which identified 134 studies reporting 950 unique complications. Problems with the multiplicity of PRO measures have also been described previously in oesophageal surgery 120, but there is no evidence of this issue in trials of CRC surgery.

This study is the largest systematic review of PROs in CRC and was conducted with rigorous methodology, but there are some limitations. The review covers published CRC studies in English up until 2010. A more exhaustive search over a more recent period of time, or inclusion of unpublished data or non‐English publications may have yielded further PROs, but all the most commonly used PROs were captured by these inclusion criteria and extending the review would have probably only identified additional rare PROs. The categorization process could be criticized as arbitrary, but efforts were made to objectify the process. First, two researchers categorized the questionnaire items independently, each blinded to the other. Second, categorization was checked for face validity by a patient representative. Finally, there has been full disclosure of the categorization in this article to allow scientific scrutiny of the process.

Having identified all the potential patient reported health domains measured in CRC surgical studies, the next phase of this research is to gain a consensus on which outcomes it is essential to measure in all trials. Recommended methods to achieve this have been defined by the international Core Outcome Measurement in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) group 6. Domains will be combined with clinical outcomes generated from a previous systematic review 117 to create an exhaustive long‐list of all potential outcomes. Key stakeholders, including patients and professionals, will then consider the importance of these outcomes and undertake a prioritization exercise called the Delphi process. This will allow the outcomes of lesser importance to be discarded from the core set. Finally, when the number of outcomes has been reduced, face‐to‐face meeting will be conducted to allow for debate about their relative merits before the final core set is agreed.

In conclusion, this systematic review of CRC surgery demonstrated significant heterogeneity of PRO measurement that may hinder comparisons between studies, limit meta‐analysis and allow outcome reporting bias. A long‐list of patient reported ‘health domains’ was generated using robust methodology to inform the development of a core outcome set.

Supporting information

Table S1. Full categorization of patient reported outcome items.

References

- 1. Speight J, Barendse SM. FDA guidance on patient reported outcomes. BMJ 2010; 340: c2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNair AG, Blazeby JM. Health‐related quality‐of‐life assessment in GI cancer randomized trials: improving the impact on clinical practice. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2009; 9: 559–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pachler J, Wille‐Jørgensen P. Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; (12):CD004323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parameswaran R, McNair A, Avery KN et al The role of health‐related quality of life outcomes in clinical decision making in surgery for esophageal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 2372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG et al The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010; 340: c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM et al Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012; 13: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boers M, Brooks P, Strand CV, Tugwell P. The OMERACT filter for outcome measures in rheumatology. J Rheumatol 1998; 25: 198–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC et al Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008; 9: 771–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Horey D, OBoyle C. Evaluating maternity care: a core set of outcome measures. Birth 2007; 34: 164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanoff HK, Goldberg RM, Pignone MP. A systematic review of the use of quality of life measures in colorectal cancer research with attention to outcomes in elderly patients. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2007; 6: 700–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Efficace F, Bottomley A, Vanvoorden V, Blazeby JM. Methodological issues in assessing health‐related quality of life of colorectal cancer patients in randomised controlled trials. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40: 187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bartels SA, Vlug MS, Ubbink DT, Bemelman WA. Quality of life after laparoscopic and open colorectal surgery: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16: 5035–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Quality of life among long‐term (>= 5 years) colorectal cancer survivors – Systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46: 2879–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gujral S, Avery KN, Blazeby JM. Quality of life after surgery for colorectal cancer: clinical implications of results from randomised trials. Support Care Cancer 2008; 16: 127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allal AS, Bieri S, Pelloni A et al Sphincter‐sparing surgery after preoperative radiotherapy for low rectal cancers: feasibility, oncologic results and quality of life outcomes. Br J Cancer 2000; 82: 1131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allal AS, Gervaz P, Gertsch P et al Assessment of quality of life in patients with rectal cancer treated by preoperative radiotherapy: a longitudinal prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 61: 1129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anthony T, Jones C, Antoine J, Sivess‐Franks S, Turnage R. The effect of treatment for colorectal cancer on long‐term health‐related quality of life. Ann Surg Oncol 2001; 8: 44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anthony T, Long J, Hynan LS et al Surgical complications exert a lasting effect on disease‐specific health‐related quality of life for patients with colorectal cancer. Surgery 2003; 134: 119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: a population‐based study. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4829–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Restrictions in quality of life in colorectal cancer patients over three years after diagnosis: a population based study. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42: 1848–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bailey C, Corner J, Addington‐Hall J, Kumar D, Haviland J. Older patients’ experiences of treatment for colorectal cancer: an analysis of functional status and service use. Eur J Cancer Care 2004; 13: 483–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, West MM. Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer 2005; 104: 2565–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bloemen JG, Visschers RG, Truin W, Beets GL, Konsten JL. Long‐term quality of life in patients with rectal cancer: association with severe postoperative complications and presence of a stoma. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Borras JM, Sanchez‐Hernandez A, Navarro M et al Compliance, satisfaction, and quality of life of patients with colorectal cancer receiving home chemotherapy or outpatient treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 2001; 322: 826–8A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Civelli V, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic vs. open colectomy in cancer patients: long‐term complications, quality of life, and survival. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 2217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruheim K, Guren MG, Skovlund E et al Late side effects and quality of life after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 76: 1005–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bruheim K, Tveit KM, Skovlund E et al Sexual function in females after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2010; 49: 826–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Caffo O, Amichetti M, Romano M, Maluta S, Tomio L, Galligioni E. Evaluation of toxicity and quality of life using a diary card during postoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 459–65; discussion 65–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Camilleri‐Brennan J, Steele RJ. Objective assessment of morbidity and quality of life after surgery for low rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2002; 4: 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Canda AE, Terzi C, Gorken IB, Oztop I, Sokmen S, Fuzun M. Effects of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on anal sphincter functions and quality of life in rectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010; 25: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Celentano V, Fabbrocile G, Luglio G, Antonelli G, Tarquini R, Bucci L. Prospective study of sexual dysfunction in men with rectal cancer: feasibility and results of nerve sparing surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010; 25: 1441–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chambers SK, Lynch BM, Aitken J, Baade P. Relationship over time between psychological distress and physical activity in colorectal cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D et al Longitudinal quality of life and quality adjusted survival in a randomised controlled trial comparing six months of bolus fluorouracil/leucovorin vs. twelve weeks of protracted venous infusion fluorouracil as adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41: 1551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen RC, Mamon HJ, Chen YH et al Patient‐reported acute gastrointestinal symptoms during concurrent chemoradiation treatment for rectal cancer. Cancer 2010; 116: 1879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney HA, Fields AL, Jones LW, Fairey AS. A randomized trial of exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care 2003; 12: 347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Wagner LJ, Kahana B. Cancer‐related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long‐term cancer survivors. Psycho‐Oncology 2006; 15: 306–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Deimling GT, Schaefer ML, Kahana B, Bowman KF, Reardon J. Racial differences in the health of older‐adult long‐term cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 2002; 20: 71–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deimling GT, Sterns S, Bowman KF, Kahana B. The health of older‐adult, long‐term cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 2005; 28: 415–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dobrowolski S, Hac S, Kobiela J, Sledzinski Z. Should we preserve the inferior mesenteric artery during sigmoid colectomy? Neurogastroent Motil 2009; 21: 1288–e123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger‐Raab A, Eckel R, Sauer H, Holzel D. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients: a four‐year prospective study. Ann Surg 2003; 238: 203–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fields AL, Keller A, Schwartzberg L et al Adjuvant therapy with the monoclonal antibody Edrecolomab plus fluorouracil‐based therapy does not improve overall survival of patients with stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1941–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fucini C, Gattai R, Urena C, Bandettini L, Elbetti C. Quality of life among five‐year survivors after treatment for very low rectal cancer with or without a permanent abdominal stoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 1099–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fujii S, Ota M, Ichikawa Y et al Comparison of short, long‐term surgical outcomes and mid‐term health‐related quality of life after laparoscopic and open resection for colorectal cancer: a case‐matched control study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010; 25: 1311–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Furst A, Burghofer K, Hutzel L, Jauch KW. Neorectal reservoir is not the functional principle of the colonic J‐pouch: the volume of a short colonic J‐pouch does not differ from a straight coloanal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 660–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Given B, Given C, Azzouz F, Stommel M. Physical functioning of elderly cancer patients prior to diagnosis and following initial treatment. Nurs Res 2001; 50: 222–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gosselink MP, Busschbach JJ, Dijkhuis CM, Stassen LP, Hop WC, Schouten WR. Quality of life after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2006; 8: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grumann MM, Noack EM, Hoffmann IA, Schlag PM. Comparison of quality of life in patients undergoing abdominoperineal extirpation or anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2001; 233: 149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H et al Short‐term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic‐assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 365: 1718–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guren MG, Dueland S, Skovlund E, Fossa SD, Poulsen JP, Tveit KM. Quality of life during radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39: 587–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guren MG, Eriksen MT, Wiig JN et al Quality of life and functional outcome following anterior or abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005; 31: 735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hamashima C. Long‐term quality of life of postoperative rectal cancer patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 17: 571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harisi R, Bodoky G, Borsodi M, Flautner L, Weltner J. Rectal cancer therapy: decision making on basis of quality of life? Zentralbl Chir 2004; 129: 139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hirche C, Mrak K, Kneif S et al Perineal colostomy with spiral smooth muscle graft for neosphincter reconstruction following abdominoperineal resection of very low rectal cancer: long‐term outcome. Dis Colon Rectum 2010; 53: 1272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bramhall SR, Hallissey MT, Whiting J et al Marimastat as maintenance therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer 2002; 86: 1864–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hoerske C, Weber K, Goehl J, Hohenberger W, Merkel S. Long‐term outcomes and quality of life after rectal carcinoma surgery. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 1295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Holzner B, Kemmler G, Greil R et al The impact of hemoglobin levels on fatigue and quality of life in cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2002; 13: 965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Janson M, Lindholm E, Anderberg B, Haglind E. Randomized trial of health‐related quality of life after open and laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer. Surg Endosc 2007; 21: 747–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H et al Randomized trial of laparoscopic‐assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3‐year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 3061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jess P, Christiansen J, Bech P. Quality of life after anterior resection versus abdominoperineal extirpation for rectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002; 37: 1201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY et al Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short‐term outcomes of an open‐label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 637–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kerr J, Engel J, Schlesinger‐Raab A, Sauer H, Holzel D. Doctor‐patient communication: results of a four‐year prospective study in rectal cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 1038–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim DJ, Kim TI, Suh JH et al Oral tegafur‐uracil plus folinic acid versus intravenous 5‐fluorouracil plus folinic acid as adjuvant chemotherapy of colon cancer. Yonsei Med J 2003; 44: 665–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim NK, Min JS, Park JK et al Intravenous 5‐fluorouracil versus oral doxifluridine as preoperative concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer: prospective randomized trials. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001; 31: 25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings P et al Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme. Br J Surg 2006; 93: 300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings P, Kennedy RH. Detailed evaluation of functional recovery following laparoscopic or open surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008; 23: 795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ko CY, Maggard M, Livingston EH. Evaluating health utility in patients with melanoma, breast cancer, colon cancer, and lung cancer: a nationwide, population‐based assessment. J Surg Res 2003; 114: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Koda K, Yasuda H, Hirano A et al Evaluation of postoperative damage to anal sphincter/levator ani muscles with three‐dimensional vector manometry after sphincter‐preserving operation for rectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg 2009; 208: 362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kopp I, Bauhofer A, Koller M. Understanding quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer: comparison of data from a randomised controlled trial, a population based cohort study and the norm reference population. Inflamm Res 2004; 53(Suppl 2): S130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Krouse RS, Herrinton LJ, Grant M et al Health‐related quality of life among long‐term rectal cancer survivors with an ostomy: manifestations by sex. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4664–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Predictors of depressive symptomatology of geriatric patients with colorectal cancer: a longitudinal view. Support Care Cancer 2002; 10: 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kuzu MA, Topcu O, Ucar K et al Effect of sphincter‐sacrificing surgery for rectal carcinoma on quality of life in Muslim patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; 45: 1359–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lundy JJ, Coons SJ, Wendel C et al Exploring household income as a predictor of psychological well‐being among long‐term colorectal cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 157–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Marijnen CA, van de Velde CJ, Putter H et al Impact of short‐term preoperative radiotherapy on health‐related quality of life and sexual functioning in primary rectal cancer: report of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1847–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mik M, Narbutt P, Tchorzewski M, Dziki A. Functional outcomes after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Clin Exp Med Lett 2009; 50: 193–6. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mosconi P, Apolone G, Barni S, Secondino S, Sbanotto A, Filiberti A. Quality of life in breast and colon cancer long‐term survivors: an assessment with the EORTC QLQ‐C30 and SF‐36 questionnaires. Tumori 2002; 88: 110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mosher CE, Sloane R, Morey MC et al Associations between lifestyle factors and quality of life among older long‐term breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer 2009; 115: 4001–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ong J, Ho KS, Chew MH, Eu KW. Prospective randomised study to evaluate the use of DERMABOND ProPen (2‐octylcyanoacrylate) in the closure of abdominal wounds versus closure with skin staples in patients undergoing elective colectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010; 25: 899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Park JG, Lee MR, Lim SB et al Colonic J‐pouch anal anastomosis after ultralow anterior resection with upper sphincter excision for low‐lying rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 2570–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Perez Lara FJ, Navarro Pinero A, de la Fuente Perucho A. Study of factors related to quality of life in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2004; 96: 746–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Persson CR, Johansson BB, Sjoden PO, Glimelius BL. A randomized study of nutritional support in patients with colorectal and gastric cancer. Nutr Cancer 2002; 42: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Phipps E, Braitman LE, Stites S, Leighton JC. Quality of life and symptom attribution in long‐term colon cancer survivors. J Eval Clin Pract 2008; 14: 254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pietrangeli A, Pugliese P, Perrone M, Sperduti I, Cosimelli M, Jandolo B. Sexual dysfunction following surgery for rectal cancer – a clinical and neurophysiological study. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2009; 28: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pollack J, Holm T, Cedermark B et al Late adverse effects of short‐course preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2006; 93: 1519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pucciarelli S, Del Bianco P, Toppan P et al Health‐related quality of life outcomes in disease‐free survivors of mid‐low rectal cancer after curative surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 1846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ramsey SD, Berry K, Moinpour C, Giedzinska A, Andersen MR. Quality of life in long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rauch P, Miny J, Conroy T, Neyton L, Guillemin F. Quality of life among disease‐free survivors of rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ravasco P, Monteiro‐Grillo I, Vidal PM, Camilo ME. Cancer: disease and nutrition are key determinants of patients' quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12: 246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ravasco P, Monteiro‐Grillo I, Vidal PM, Camilo ME. Dietary counseling improves patient outcomes: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial in colorectal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1431–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ross L, Abild‐Nielsen AG, Thomsen BL, Karlsen RV, Boesen EH, Johansen C. Quality of life of Danish colorectal cancer patients with and without a stoma. Support Care Cancer 2007; 15: 505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sailer M, Fuchs KH, Fein M, Thiede A. Randomized clinical trial comparing quality of life after straight and pouch coloanal reconstruction. Br J Surg 2002; 89: 1108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sammour T, Kahokehr A, Hayes J, Hulme‐Moir M, Hill AG. Warming and humidification of insufflation carbon dioxide in laparoscopic colonic surgery: a double‐blinded randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 1024–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sapp AL, Trentham‐Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Hampton JM, Moinpour CM, Remington PL. Social networks and quality of life among female long‐term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer 2003; 98: 1749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Scarpa M, Erroi F, Ruffolo C et al Minimally invasive surgery for colorectal cancer: quality of life, body image, cosmesis, and functional results. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Schmidt C, Daun A, Malchow B, Kuchler T. Sexual impairment and its effects on quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107: 123–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, Longo WE, Kremer B. Ten‐year historic cohort of quality of life and sexuality in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, Longo WE, Kremer B. Impact of age on quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg 2005; 29: 190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Schwenk W, Studiengruppe LC. [The LAPDIV‐CAMIC Study. Multicenter prospective randomized study of short‐term and intermediate‐term outcome of laparoscopic and conventional sigmoid resection in diverticular disease]. Chirurg 2004; 75: 706–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Siassi M, Weiss M, Hohenberger W, Losel F, Matzel K. Personality rather than clinical variables determines quality of life after major colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 662–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sideris L, Zenasni F, Vernerey D et al Quality of life of patients operated on for low rectal cancer: impact of the type of surgery and patients' characteristics. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 2180–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Song PH, Yun SM, Kim JH, Moon KH. Comparison of the erectile function in male patients with rectal cancer treated by preoperative radiotherapy followed by surgery and surgery alone. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010; 25: 619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Stamopoulos P, Theodoropoulos GE, Papailiou J et al Prospective evaluation of sexual function after open and laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 2665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Stephens RJ, Thompson LC, Quirke P et al Impact of short‐course preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer on patients' quality of life: data from the Medical Research Council CR07/National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group C016 randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 4233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sultan S, Fisher DA, Voils CI, Kinney AY, Sandler RS, Provenzale D. Impact of functional support on health‐related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer 2004; 101: 2737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tiv M, Puyraveau M, Mineur L et al Long‐term quality of life in patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative (chemo)‐radiotherapy within a randomized trial. Cancer Radiother 2010; 14: 530–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tjandra JJ, Reading DM, McLachlan SA et al Phase II clinical trial of preoperative combined chemoradiation for T3 and T4 resectable rectal cancer: preliminary results. Dis Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 1113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Trentham‐Dietz A, Remington PL, Moinpour CM, Hampton JM, Sapp AL, Newcomb PA. Health‐related quality of life in female long‐term colorectal cancer survivors. Oncologist 2003; 8: 342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Trninic Z, Vidacak A, Vrhovac J, Petrov B, Setka V. Quality of life after colorectal cancer surgery in patients from University Clinical Hospital Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Coll Antropol 2009; 33(Suppl 2): 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Tsunoda Y, Watanabe M, Matsui N. Health‐related quality of life of colorectal cancer patients receiving oral UFT plus leucovorin compared with those with surgery alone. Int J Clin Oncol 2010; 15: 153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. van den Brink M, van den Hout WB, Kievit J et al The impact of diagnosis and treatment of rectal cancer on paid and unpaid labor. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Velenik V, Oblak I, Anderluh F. Long‐term results from a randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant combined‐modality therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol 2010; 5: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Vironen JH, Kairaluoma M, Aalto AM, Kellokumpu IH. Impact of functional results on quality of life after rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 568–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, Sargent D, Schroeder G, Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study G . Short‐term quality‐of‐life outcomes following laparoscopic‐assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2002; 287: 321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Whistance RN, Conroy T, Chie W et al Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ‐CR29 questionnaire module to assess health‐related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 3017–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Whistance RN, Gilbert R, Fayers P et al Assessment of body image in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010; 25: 369–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Yau T, Watkins D, Cunningham D, Barbachano Y, Chau I, Chong G. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life in rectal cancer patients with or without stomas following primary resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 669–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yoo HJ, Kim JC, Eremenco S, Han OS. Quality of life in colorectal cancer patients with colectomy and the validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐Colorectal (FACT‐C), Version 4. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005; 30: 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Whistance RN, Forsythe RO, McNair AG et al A systematic review of outcome reporting in colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 2013; 15: e548–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Blencowe NS, Strong S, McNair AG et al Reporting of short‐term clinical outcomes after esophagectomy: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Potter S, Brigic A, Whiting PF et al Reporting clinical outcomes of breast reconstruction: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Macefield RC, Jacobs M, Korfage IJ et al Developing core outcomes sets: methods for identifying and including patient‐reported outcomes (PROs). Trials 2014; 15: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Full categorization of patient reported outcome items.