Abstract

Aims

To confirm, in a 26‐week extension study, the sustained efficacy and safety of a fixed combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) compared with either insulin degludec or liraglutide alone, in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Insulin‐naïve adults with type 2 diabetes randomized to once‐daily IDegLira, insulin degludec or liraglutide, in addition to metformin ± pioglitazone, continued their allocated treatment in this preplanned 26‐week extension of the DUAL I trial.

Results

A total of 78.8% of patients (1311/1663) continued into the extension phase. The mean glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration at 52 weeks was reduced from baseline by 1.84% (20.2 mmol/mol) for the IDegLira group, 1.40% (15.3 mmol/mol) for the insulin degludec group and 1.21% (13.2 mmol/mol) for the liraglutide group. Of the patients on IDegLira, 78% achieved an HbA1c of <7% (53 mmol/mol) versus 63% of the patients on insulin degludec and 57% of those on liraglutide. The mean fasting plasma glucose concentration at the end of the trial was similar for IDegLira (5.7 mmol/l) and insulin degludec (6.0 mmol/l), but higher for liraglutide (7.3 mmol/l). At 52 weeks, the daily insulin dose was 37% lower with IDegLira (39 units) than with insulin degludec (62 units). IDegLira was associated with a significantly greater decrease in body weight (estimated treatment difference, −2.80 kg, p < 0.0001) and a 37% lower rate of hypoglycaemia compared with insulin degludec. Overall, all treatments were well tolerated and no new adverse events or tolerability issues were observed for IDegLira.

Conclusions

These 12‐month data, derived from a 26‐week extension of the DUAL I trial, confirm the initial 26‐week main phase results and the sustainability of the benefits of IDegLira compared with its components in glycaemic efficacy, safety and tolerability.

Keywords: diabetes therapy, hypoglycaemia, insulin degludec, liraglutide

Introduction

Basal insulin and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1RAs) have complementary modes of action, and combination treatment has generated considerable interest as a treatment option for patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). GLP‐1RAs reduce food intake and promote weight loss 1 and have the additional benefit of a low risk of hypoglycaemia compared with basal insulin 2, 3. These features may be helpful in overcoming some aspects of clinical inertia with respect to intensifying therapy in patients with T2D 4. A fixed‐ratio soluble combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide [IDegLira; 100 units and 3.6 mg/ml, respectively (Xultophy®)] was approved in 2014 by the European Medicines Agency and is delivered via pen‐device. This combination allows both active ingredients to be administered with a single injection.

Results from the previously published, 26‐week randomized, controlled trial (DUAL I) showed that treatment with IDegLira resulted in a substantial improvement in glycaemic control, in conjunction with a lower risk of hypoglycaemia and weight loss compared with insulin degludec alone, and with better glucose control and fewer gastrointestinal (GI) side effects compared with liraglutide alone 5. The objectives of the present extension study were to assess the sustainability of the treatment response of IDegLira over 52 weeks and to obtain additional data regarding safety. Data were also analysed post hoc to evaluate whether the effects of IDegLira were applicable to different body mass index (BMI) categories, given that obesity is one of the most common comorbidities for patients with T2D.

The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under the number: NCT01336023.

Methods

We describe the 26‐week extension of DUAL I, a phase III, randomized, open‐label, three‐arm, parallel‐group, 26‐week trial in insulin‐naïve adults (≥18 years) with T2D conducted at 271 sites (19 countries). The original study has been described previously 5 and further detail on study methods is also provided in Table S1 of File S1. Briefly, patients were randomized (2 : 1 : 1) to once‐daily injections of IDegLira, insulin degludec or liraglutide (open‐label), with patients stratified for the following factors: baseline glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration [HbA1c ≤8.3 or >8.3% (≤67 or >67 mmol/mol)]; concomitant oral antidiabetic drug (OAD) treatment (metformin background or metformin + pioglitazone background); and participation in a substudy involving a standardized meal test and continuous glucose monitoring 6, 7.

IDegLira (insulin degludec 100 U/ml plus liraglutide 3.6 mg/ml), insulin degludec (100 U/ml) and/or liraglutide (6 mg/ml) were all administered subcutaneously. The IDegLira dosing unit is defined as a dose step, with one dose step comprising 1 unit of insulin degludec and 0.036 mg liraglutide in a volume of 0.01 ml. IDegLira was started at 10 dose steps (10 U insulin degludec plus 0.36 mg liraglutide, once daily).

As in the original 26‐week trial, adjustment of IDegLira was performed twice weekly based on the mean of three consecutive daily fasting self‐monitored blood glucose (SMBG) measurements immediately before dose adjustment. Adjustments occurred in two dose steps (2 U insulin degludec and 0.072 mg liraglutide) to the fasting glycaemic target of 4.0–5.0 mmol/l (72–90 mg/dl). Insulin degludec treatment was initiated with 10 U, and titrated twice weekly to the fasting glycaemic target of 4.0–5.0 mmol/l (72–90 mg/dl) based on the mean SMBG (fasting) from three preceding measurements as described for IDegLira. IDegLira, at the maximum allowable dose of 50 dose steps, provides 50 units of insulin degludec and 1.8 mg of liraglutide. There was no limit to the titration of insulin degludec. Liraglutide treatment was started at 0.6 mg/day and subsequently increased by 0.6 mg in weekly dose escalation steps to a maximum dose of 1.8 mg/day. Liraglutide dose was to remain unchanged after dose escalation to 1.8 mg/day. In the extension phase, the twice‐weekly adjustment of IDegLira and insulin degludec, aiming at the same fasting glucose target, was to be continued.

The primary endpoint of DUAL 1 was change from baseline in HbA1c at 26 weeks of treatment. The 52‐week secondary endpoints included change from baseline in HbA1c concentration, percentage of patients reaching HbA1c targets of <7 and ≤6.5%, and changes from baseline in laboratory‐measured fasting plasma glucose (FPG), body weight, insulin dose and nine‐point SMBG profiles. Post hoc analyses were performed to examine whether the effects of IDegLira (regarding HbA1c, insulin dose and hypoglycaemia) were consistent across the range of baseline BMI categories.

Protocol‐defined safety variables are presented in Table S1 of File S1. With respect to relationship to trial product, ‘probably’ related adverse events (AEs) were those with good reason and sufficient documentation to assume a causal relationship, ‘possibly’ related AEs were those for which a causal relationship was conceivable and could not be dismissed. AEs determined to be ‘unlikely’ to be related to trial products were those that did not fit into either one of the above categories. Certain types of AEs (pancreatitis or suspicion of pancreatitis, neoplasms, thyroid disease requiring thyroidectomy and cardiovascular disease) were adjudicated by an independent external adjudication committee (EAC) that was blinded to treatment assignment (Table S2, File S1). The EAC was divided into three subcommittees that evaluated events according to areas of expertise: cardiovascular events (two cardiologists and two neurologists); pancreatitis events (two gastroenterologists); neoplasms; and thyroid disease requiring thyroidectomy (two oncologists and one endocrinologist). Diagnostic criteria for the individual adjudicated AEs were established via a specific EAC Charter before the trial initiation. Positively adjudicated events were those AEs which the EAC confirmed met these predefined criteria. Calcitonin monitoring was included in the trial, supervised by an independent calcitonin monitoring committee of thyroid experts.

Statistical Analysis

An analysis of covariance (ancova) model was used for efficacy analysis (HbA1c) on the full analysis set, with treatment, previous OADs, baseline HbA1c stratum, substudy participation and country as fixed factors, and the corresponding baseline value as covariate. The last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach was used to impute missing values for endpoints derived at 52 weeks of treatment. Changes from baseline after 52 weeks of treatment in body weight, laboratory‐measured FPG, and endpoints derived from nine‐point SMBG profiles were analysed separately using a similar ancova model to that used for the primary endpoint; however, for end‐of‐trial dose, baseline HbA1c was included as a covariate instead of baseline dose. The number of confirmed hypoglycaemic episodes was analysed using a negative binomial regression model with a log‐link function and treatment, previous OADs, baseline HbA1c stratum, substudy participation and country as fixed factors, and the logarithm of the exposure time as offset 8. As post hoc analyses, change in HbA1c from baseline, end‐of‐trial insulin dose and the number of confirmed hypoglycaemic episodes were analysed for the following baseline BMI categories: <25; ≥25 to <30; ≥30 to <35; and ≥35 kg/m2. All post hoc endpoints were analysed using the prespecified models as described above. Additional information about statistical methods is available in the publication of the 26‐week main trial 5 and in Table S1 of File S1.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1 and Figure S1 of File S1 shows the patient disposition. Treatment groups remained well matched, and similar proportions of patients randomized in the main trial continued into the extension phase (79.7, 80.4 and 75.4% for IDegLira, insulin degludec and liraglutide, respectively). The lower proportion for the liraglutide arm reflects the higher discontinuation rate at the initiation of treatment, mainly as a result of GI side effects.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | IDegLira, n = 833* | Insulin degludec, n = 413* | Liraglutide, n = 414* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 398 (47.8%) | 213 (51.6%) | 206 (49.8%) |

| Race: white/black/Asian/other, % | 61.6/8.6/27.3/2.4 | 62.2/5.6/29.1/3.2 | 62.3/6.8/28.1/2.9 |

| Age, years | 55.1 (9.9) | 54.9 (9.7) | 55.0 (10.2) |

| Weight, kg | 87.2 (19.0) | 87.4 (19.2) | 87.4 (18.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.2 (5.2) | 31.2 (5.3) | 31.3 (4.8) |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 6.6 (5.1) | 7.0 (5.3) | 7.2 (6.1) |

| HbA1c, % | 8.3 (0.9) | 8.3 (1.0) | 8.3 (0.9) |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 67 (9.7) | 67 (10.7) | 67 (10.3) |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/l | 9.2 (2.4) | 9.4 (2.7) | 9.0 (2.6) |

| OAD at screening, n (%) | |||

| Metformin | 691 (83.0) | 343 (83.1) | 338 (81.6) |

| Metformin + pioglitazone† | 142 (17.0) | 70 (16.9) | 75 (18.1) |

Data are mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise stated. IDegLira, insulin degludec/liraglutide combination; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug.

Full analysis set.

One patient in the liraglutide group was receiving metformin + glimepiride at screening; the median daily dose of metformin at screening was 2000 mg; the median daily dose of pioglitazone at screening was 30 mg.

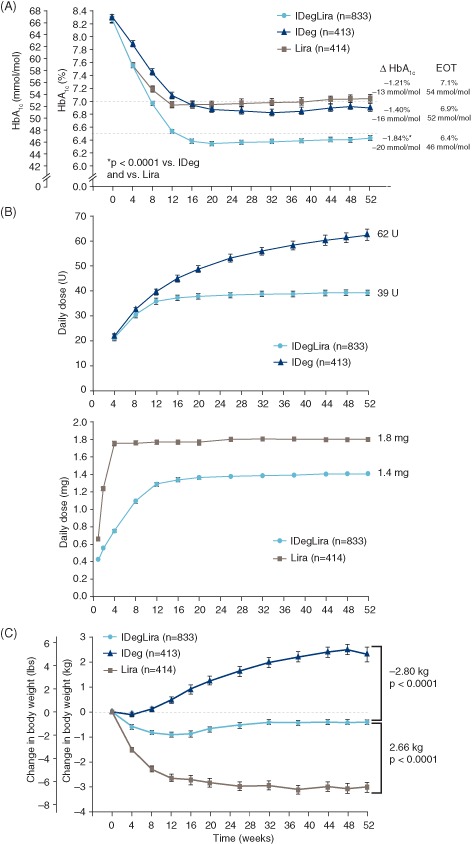

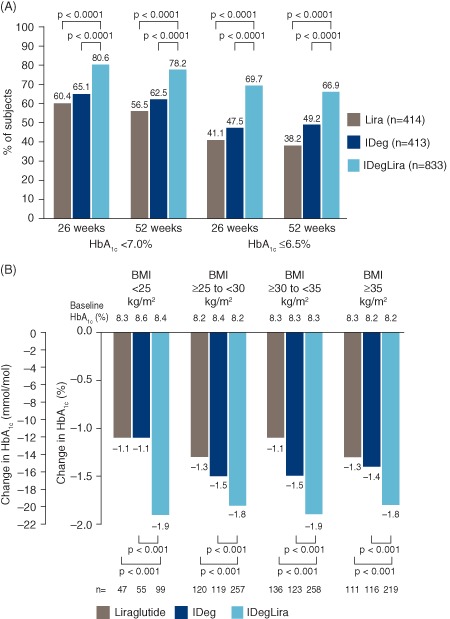

At 52 weeks, the mean HbA1c concentration was reduced to a significantly greater extent with IDegLira compared with insulin degludec alone [−1.84 vs −1.40% (−20.2 vs −15.3 mmol/mol); estimated treatment difference (ETD) −0.46%, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.57, −0.34 (−5.0 mmol/mol, 95% CI −6.3, −3.7); p < 0.0001] and compared with liraglutide alone [−1.84 vs −1.21% (20.2 vs 13.2 mmol/mol); ETD −0.65%, 95% CI −0.76, −0.53 (−7.1 mmol/mol, 95% CI −8.3, −5.8); p < 0.0001 (Figure 1A)], mirroring the main trial results after 26 weeks. The sensitivity analyses on the per protocol set, the completer analysis set and the mixed model for repeated measurement analysis confirmed these results (Table S3, File S1). After 52 weeks, a significantly greater proportion of patients using IDegLira (78.2 vs 66.9%) reached HbA1c targets of either <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol), respectively, compared with either insulin degludec (62.5 vs 49.2%) or liraglutide [56.5 vs 38.2%: all comparisons vs IDegLira; p < 0.0001 (Figure 2A)]. The percentage of responders without weight gain and without confirmed hypoglycaemia is shown in Table S4 of File S1. In the post hoc analysis, the decrease in HbA1c concentration was significantly greater for IDegLira than for either insulin degludec or liraglutide across all baseline BMI categories [all comparisons p < 0.001 (Figure 2B)].

Figure 1.

(A) Mean glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration over time, by treatment group. Mean values with error bars [standard error of the mean (s.e.m.)] based on the full analysis set (FAS) and LOCF‐imputed data. p values from an analysis of covariance (ancova) model. Dashed lines (‐‐): American Diabetes Association HbA1c target <7.0%; International Diabetes Federation HbA1c target ≤6.5%. (B) Mean daily doses of insulin degludec and liraglutide components of treatment, over time. Mean values with error bars (s.e.m.) based on safety analysis set and LOCF‐imputed data; n for each treatment based on FAS; week 52 dose is observed dose based on FAS. (C) Change in mean body weight over time, by treatment group. Mean values with error bars (s.e.m.) based on FAS and LOCF‐imputed data. Estimated treatment differences and p values are from an ancova model. EOT, end of trial; IDeg, insulin degludec; IDegLira, insulin degludec/liraglutide combination; Lira, liraglutide. Results at 26 weeks are from the main phase of the DUAL I trial and have been reported previously 5).

Figure 2.

(A) Percentage of subjects reaching a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) target of <7.0 or ≤6.5% at 26 and 52 weeks, by treatment group. Values based on full analysis set (FAS) and LOCF‐imputed data; p values are from a logistic regression model. HbA1c target <7.0% (53 mmol/mol) is from American Diabetes Association and HbA1c target ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol) is from the International Diabetes Federation. (B) HbA1c reduction at 52 weeks by treatment group, stratified by baseline BMI. Data are mean from observed values based on FAS and LOCF‐imputed data; p values from ancova model. n, number of subjects contributing to the analysis. IDeg, insulin degludec; IDegLira, insulin degludec/liraglutide combination; Lira, liraglutide. Results at 26 weeks are from the main phase of the DUAL I trial and have been reported previously 5.

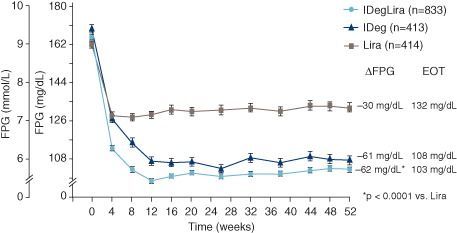

At 52 weeks, mean [± standard deviation (s.d.)] FPG was 5.7 (±2.0) mmol/l for IDegLira, compared with 6.0 (±2.5) mmol/l for insulin degludec and 7.3 (±2.5) mmol/l for liraglutide. The decrease in FPG from baseline at 52 weeks was similar for IDegLira versus insulin degludec (ETD −0.20 mmol/l, 95% CI −0.45, 0.05; p = 0.11). The reduction in mean FPG was twofold greater for IDegLira compared with liraglutide [change from baseline −3.45 mmol/l compared with −1.67 mmol/l for IDegLira and liraglutide, respectively; ETD −1.67 mmol/l, 95% CI −1.92, −1.42; p < 0.0001 (Figure 3)]. The overall mean nine‐point SMBG profiles decreased across all treatment groups by 52 weeks (Figure S2, top, File S1). The overall mean nine‐point SMBG for IDegLira was significantly lower compared with insulin degludec (ETD −0.30 mmol/l, 95% CI −0.50, −0.11; p = 0.0025) and liraglutide (ETD −0.99 mmol/l, 95% CI −1.19, −0.80; p < 0.0001). The postprandial glucose increment was significantly lower for IDegLira than for insulin degludec after all main meals (Figure S2, bottom, File S1).

Figure 3.

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) from 0 to 52 weeks by treatment group. Mean values with error bars (standard error of the mean) based on full analysis set and LOCF‐imputed data; p value is from an analysis of covariance model. IDeg, insulin degludec; IDegLira, insulin degludec/liraglutide combination; Lira, liraglutide. Results at 26 weeks are from the main phase of the DUAL I trial and have been reported previously 5.

Mean daily doses of the insulin degludec and liraglutide components were significantly lower with combination therapy than with either product used alone (Figure 1B). At 52 weeks, the mean (± s.d.) daily insulin dose was 39 (± 13) units and 62 (± 42) units for patients treated with IDegLira and insulin degludec, respectively (ETD −23.4 units, 95% CI −26.4, −20.3; p < 0.0001). The lower insulin dose in patients treated with IDegLira compared with insulin degludec was significant regardless of baseline BMI category (all p < 0.0001). During the 26‐week extension, the mean daily insulin dose continued to increase for insulin degludec, with only a one‐dose step increase for IDegLira. The mean liraglutide dose was lower for the IDegLira group than for the liraglutide group throughout the trial and at week 52 (1.4 ± 0.5 vs 1.8 ± 0.7 mg, respectively). At the completion of the extension period, a higher percentage of patients, 351/621 (56.5%), had reached the maximum dose of IDegLira (50 dose steps) compared with the initial 26 weeks (end of main phase of the trial): 324/734 (44.1%). The mean (± s.d.) HbA1c values for IDegLira were 6.6 ± 1.1 and 6.5 ± 1.0%, at 52 and 26 weeks, respectively The proportion of patients on maximum dose of IDegLira reaching the American Diabetes Association (ADA) target of HbA1c <7.0% was 70.1% at the end of the extension trial, which was similar to that at 26 weeks (73.8%).

With IDegLira, body weight remained relatively stable throughout the trial, whereas it increased with insulin degludec both in the original 26‐week main phase as well as during the 26‐week extension; the weight decrease with liraglutide occurred primarily during the original 26 weeks, but was sustained throughout the 26‐week extension period (Figure 1C). At 52 weeks of treatment, change in body weight from baseline was −0.4, +2.3 and −3.0 kg with IDegLira, insulin degludec and liraglutide, respectively, and the treatment differences were statistically significant for IDegLira versus both insulin degludec and liraglutide (Figure 1C). As shown in Table S4 of File S1, more patients randomized to IDegLira achieved either ADA (HbA1c < 7.0%) or American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE)/International Diabetes Federation (IDF) targets (HbA1c ≤ 6.5%) without weight gain and/or without confirmed hypoglycaemia than patients randomized to insulin degludec (all comparisons p < 0.0001). The largest proportion of patients achieving the ADA target without weight gain and without confirmed hypoglycaemia was in the group allocated to liraglutide (p = 0.0007). These findings were generally similar to those reported at 26 weeks 5.

The rates of confirmed hypoglycaemic events per 100 patient‐years of exposure (PYE) were 176.7, 279.1 and 19.1 for IDegLira, insulin degludec and liraglutide, respectively. The rate of confirmed hypoglycaemia after 52 weeks of treatment was significantly lower for IDegLira versus insulin degludec [rate ratio 0.63 (95% CI 0.50, 0.79); p < 0.0001] and significantly greater for IDegLira versus liraglutide [rate ratio 8.52 (95% CI 6.09, 11.93); p < 0.0001] (Figure S3, top, File S1). The rates of confirmed nocturnal hypoglycaemic events were 22.3, 36.6 and 1.8 per 100 PYE, for IDegLira, insulin degludec and liraglutide, respectively. There was a significant difference in the number of confirmed nocturnal hypoglycaemic episodes between IDegLira and liraglutide [rate ratio 11.99 (95% CI 4.85, 29.63); p < 0.0001] with fewer in the liraglutide group, but there was no significant difference between IDegLira and insulin degludec [rate ratio 0.68 (95% CI 0.44, 1.06); p = 0.09 (Figure S3, bottom, File S1)]. There were three confirmed severe events with IDegLira, two with insulin degludec and two with liraglutide. When stratified by baseline BMI, the rate of confirmed hypoglycaemia per 100 PYE versus insulin degludec was numerically lower for all categories of baseline BMI, with the rate ratio being statistically significant for BMI ≥30 to <35 kg/m2 (p = 0.0116) and for BMI ≥35 kg/m2 (p = 0.0105). The rate of confirmed hypoglycaemic episodes was significantly greater for IDegLira versus liraglutide at all levels of baseline BMI [p < 0.0001 (Figure S4, File S1)].

Similar to the first 26 weeks, the most frequently reported AEs were headache, nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection. The majority of AEs in all groups were mild in severity and judged to be unlikely to be related to trial products by the investigator (Table 2). The overall rate of AEs was similar with IDegLira and insulin degludec and lower than with liraglutide (407.9 vs 383.3 vs 507.3 events per 100 PYE, respectively). During the 52‐week treatment period, the proportion of patients with AEs leading to withdrawal was lower with IDegLira (n = 14, 1.7%) and insulin degludec (n = 9, 2.2%) than with liraglutide (n = 26, 6.3%). This appeared to be attributable to AEs occurring during the early weeks of the main trial. When only the 26‐week extension phase was considered, withdrawals because of AEs were fewer, and there were similar rates for all three treatment groups (n = 5, 0.6%; n = 1, 0.2%; and n = 2, 0.5% for IDegLira, insulin degludec and liraglutide, respectively). The increased numbers of AEs possibly or probably related to treatment and withdrawals attributable to AEs in the liraglutide group were related to the higher frequency of GI events shortly after initiating liraglutide. The incidence of nausea was similar in all three treatment groups during the extension phase (Figure S5, File S1).

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events

| IDegLira, n = 825* | Insulin degludec, n = 412* | Liraglutide, n = 412* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Week 26 | Week 52 | Week 26 | Week 52 | Week 26 | Week 52 |

| Percentage of patients with AEs† | 63.2 | 71.2 | 60.2 | 70.6 | 72.6 | 77.2 |

| AE rate per patient‐year of exposure | 4.8 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 6.4 | 5.1 |

| Percentage of subjects with serious AEs† | 2.3 | 4.6 | 1.9 | 5.3 | 3.4 | 5.8 |

| Serious AE rate per PYE | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

AE, adverse event; IDegLira, insulin degludec/liraglutide combination; PYE, patient‐year of exposure.

Safety analysis set.

Percentage of patients with ≥1 event. Results at 26 weeks are from the main phase of the DUAL I trial and have been reported previously 5.

There were 109 serious AEs (SAEs) reported in 5.1% of the patients (n = 84) over 52 weeks. The overall rate of SAEs was 6.7 per 100 PYE with IDegLira, 8.9 per 100 PYE with insulin degludec and 9.3 per 100 PYE with liraglutide. The majority of SAEs were unlikely to be related to trial product, but 10 SAEs reported in 9 patients (four SAEs with IDegLira, one with insulin degludec and five with liraglutide) were possibly or probably related to trial product.

The definition of a treatment‐emergent AE has been described previously 5. There were five AEs reported as pancreatitis by the investigators (three treatment‐emergent AEs: two with IDegLira and one with liraglutide; two non‐treatment‐emergent AEs: one with insulin degludec and one with liraglutide), all of which were adjudicated by the blinded EAC. Of these, one treatment‐emergent AE (reported as acute pancreatitis in connection to a metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma), was positively adjudicated in the liraglutide group, and one non‐treatment emergent AE was positively adjudicated in a patient who had been in the insulin degludec group. Additionally, 16 AEs of increased lipase and/or amylase (one screening event during the main trial and 15 treatment‐emergent AEs: 7 with IDegLira, 2 with insulin degludec and 6 with liraglutide) were identified using predefined searches of the safety database and assessed by the EAC. Of these, one treatment‐emergent AE (reported as increased lipase) was adjudicated as pancreatitis in the liraglutide group. All of the positively adjudicated events were considered unlikely to be related to the trial drug by the local investigator. The EAC did not assess causality with respect to trial product for the adjudicated events.

A total of 38 treatment‐emergent cardiovascular events in 24 patients were assessed by the EAC. Of these, 20 events in 13 patients were positively adjudicated (eight with IDegLira, eight with insulin degludec and four with liraglutide), six of which were classified as major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), while the remaining 14 events were classified as non‐MACE (Table S2, File S1). Of the six MACE, four occurred in the IDegLira group (two myocardial infarctions and two cardiovascular deaths) and one (myocardial infarction) in each of the insulin degludec and liraglutide groups. Of the two cardiovascular deaths positively adjudicated in the IDegLira group, one was attributed to sudden death for unknown reasons and one was a result of cardiopulmonary arrest caused by sepsis. Out of the 14 non‐MACE, 4 occurred in the IDegLira group [coronary revascularization (4)], 7 occurred in the insulin degludec group [coronary revascularization (4), unstable angina pectoris (2), heart failure (1)] and 3 occurred in the liraglutide group [coronary revascularization (2), unstable angina pectoris (1)]. Furthermore, two non‐treatment cardiovascular events were sent for adjudication, one of which was confirmed as a non‐MACE (coronary revascularization) in a patient previously on liraglutide.

No medullary thyroid carcinomas were reported, and there were no EAC‐confirmed thyroid neoplasms. An increase in pulse was observed in the IDegLira (mean 1.8 beats/min) and liraglutide (mean 1.4 beats/min) groups, whereas pulse remained unchanged with insulin degludec. The ETD regarding mean change in systolic blood pressure from baseline to week 52 between IDegLira and insulin degludec was −1.54 mmHg (95% CI −2.89, −0.19; p = 0.0256), while there was no significant difference in systolic blood pressure between IDegLira and liraglutide. Regarding diastolic pressure, there was no significant difference between treatment groups from baseline to week 52. An increase from baseline to end of treatment in lipase was observed in the IDegLira and liraglutide groups (mean 8.3 vs 12.5 units/l, respectively), whereas a decrease was seen in the insulin degludec group (−7.1 units/l). A lesser absolute mean increase was observed for amylase with the groups treated with IDegLira or liraglutide. No clinically relevant changes in other biochemical or haematological variables, physical examination, fundoscopy or ECG findings were observed from baseline to end of treatment in any of the treatment groups.

Discussion

The 52‐week data followed the trends of the 26‐week results (shown in Figures 1, 2A, 3; Figures S3 and S5, File S1) from the DUAL I trial and show sustainability of the glucose‐lowering effect of IDegLira in insulin‐naïve patients with T2D previously inadequately controlled on OADs. No new safety issues were observed with the longer exposure. The mean HbA1c concentration with IDegLira at 52 weeks [6.4% (47 mmol/mol)] was significantly lower compared with either insulin degludec [6.9% (52 mmol/mol)] or liraglutide [7.1% (54 mmol/mol)]. The prespecified sensitivity analyses were consistent with these results (Table S3, File S1). The superior glucose‐lowering effects relative to insulin degludec or liraglutide were observed irrespective of baseline BMI. A higher percentage of patients receiving IDegLira achieved HbA1c <7.0% (ADA target) or ≤6.5% (AACE/IDF target) compared with the percentages for insulin degludec and liraglutide. This improvement in glucose control with IDegLira occurred despite the fact that IDegLira and insulin degludec were titrated to an identical prebreakfast plasma glucose target.

In contrast to basal insulin degludec insulin used alone, GLP‐1RAs, such as liraglutide, address postprandial glucose with glucose‐dependent stimulation of pancreatic insulin secretion and glucose‐dependent suppression of glucagon 9, 10. The combined effects of IDegLira on fasting glucose and of liraglutide on postprandial glucose are the presumed mechanism for the advantages of IDegLira.

Compared with insulin degludec alone, IDegLira was associated with a 37% lower mean daily insulin dose at 52 weeks. This difference in insulin dose was observed for all baseline BMI categories. Despite the lower insulin dose in the IDegLira group, the mean FPG was close to the glycaemic target and similar in both groups. As might be expected with a substantially lower insulin dose and a weight‐decreasing effect from the liraglutide component, weight gain was avoided with IDegLira, compared with weight gain with insulin degludec. The presence of the insulin component in IDegLira was associated with a higher incidence of hypoglycaemia than liraglutide but a significantly lower incidence than with insulin degludec, despite the lower mean HbA1c concentration achieved.

During the 26‐week extension of the DUAL I trial, IDegLira continued to be generally well tolerated without any safety concerns in relation to the comparators in terms of standard safety assessments, consistent with the initial 26‐week main phase of the trial. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, over 52 weeks of treatment, the cumulative incidence of confirmed hypoglycaemia was 37% lower with IDegLira than with insulin degludec, despite glycaemic control being significantly better with IDegLira (lower HbA1c). This lower risk of hypoglycaemia with IDegLira compared with insulin degludec was observed across all four categories of baseline BMI, and was statistically significant for the two highest categories.

A greater proportion of patients randomized to liraglutide withdrew during the 26 weeks of the main phase, compared with IDegLira or insulin degludec 5 primarily because of the higher frequency of adverse GI events with liraglutide that were deemed probably or possibly related to treatment, but a similar proportion of completers in each group continued in the extension phase. During the extension trial, GI side effects were infrequent: all three treatments showed very low rates of nausea.

With respect to limitations, this trial was open‐label because the different treatment regimens required different titration schemes and different injection devices. A double‐dummy design to achieve blinding was regarded as unfeasible because it would have increased the number of injections to an unacceptable level. The trial assessment was based on objective laboratory values. The analyses of key endpoints by categories of baseline BMI were not prespecified.

In summary, data from this DUAL I extension trial show that the glucose‐lowering effect of IDegLira was sustained for a full year without compromising safety and mitigated the side effects seen with use of the components individually. Compared with insulin degludec, IDegLira was associated with a significantly greater reduction in HbA1c concentration, significantly lower risk of hypoglycaemia, and no (mean) weight gain over the 52‐week treatment period. Compared with liraglutide, IDegLira was associated with a significantly greater reduction in HbA1c, significantly greater reduction in FPG during the entire trial period, and fewer GI adverse events, especially at treatment initiation. With its effective glycaemic control and lower incidence of side effects, IDegLira could be an attractive alternative for insulin‐naïve patients to current treatment intensification options such as initiation of either basal insulin or GLP‐1RAs alone. Because of the lower frequency of GI events compared with GLP‐1RAs and the lower frequency of hypoglycaemia compared with basal insulin, and because both active ingredients can be co‐administered with a single‐daily injection using a simple pen device, IDegLira may also help overcome clinical inertia with respect to intensifying therapy 4.

Conflict of Interest

S. C. L. G has served on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk A/S, Sanofi, Takeda, and Eli Lilly and Company, and has received research support from Novo Nordisk A/S, Sanofi, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd. B. W. B has served on advisory panels and as a consultant for Novo Nordisk A/S, Janssen and Company, and Sanofi, has received research support from Novo Nordisk A/S, Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi, Merck, and Johnson & Johnson, and has served as a speaker for Novo Nordisk A/S, Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi, Merck, GSK and AstraZeneca. V. C. W has served on advisory panels and as a speaker for Novo Nordisk A/S, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH & Co. KG, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Sanofi, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Johnson & Johnson, Roche Pharmaceuticals and Abbott Laboratories, Inc. H. W. R has served on advisory panels for Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Biodel, Inc., Bayer Health Care, LLC, Novo Nordisk A/S, Roche Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi, as a consultant for Biodel, Inc., Roche Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., has received research support from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Biodel, Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Hamni, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Novo Nordisk A/S, Roche Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi, and has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Novo Nordisk A/S, Sanofi, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc. S. L. has served on advisory panels for Novo Nordisk Australia. M. Z. and P. D. R. are employees of Novo Nordisk A/S and hold shares of stock in the company. J. B. B. has served as investigator and/or consultant without any direct financial benefit under contracts between his employer and the following companies: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Andromeda, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Dance Biopharm, Elcelyx Therapeutics Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, GI Dynamics, GlaxoSmithKline, Halozyme Therapeutics, F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd., Intarcia Therapeutics, Johnson & Johnson, Lexicon, LipoScience, Medtronic, Merck, Metavention, Novo Nordisk A/S, Orexigen Therapeutics Inc., Osiris Therapeutics Inc., Pfizer Inc., Quest Diagnostics, Sanofi, Santarus, Scion NeuroStim, Takeda, ToleRx and TransTech Pharma. He is a consultant to PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals Inc. and has personally received stock options and payments for that work. No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

All authors (S. C. L. G., B. W. B., V. C. W., H. W. R., S. L., M. Z., P. D. R. and J. B. B.) confirm that they meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) uniform requirements for authorship and that they have contributed to: critical analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting/critically revising the article and sharing in the final responsibility for the content of the manuscript and the decision to submit it for publication.

Supporting information

File S1. Supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by Novo Nordisk A/S. The authors would like to thank Gary Patronek and Mark Nelson at Watermeadow Medical for medical writing and editorial assistance.

References

- 1. van Can J, Sloth B, Jensen CB, Flint A, Blaak EE, Saris WH. Effects of the once‐daily GLP‐1 analog liraglutide on gastric emptying, glycemic parameters, appetite and energy metabolism in obese, non‐diabetic adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 784–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eng C, Kramer CK, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist and basal insulin combination treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2014; 384: 2228–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldenberg R. Insulin plus incretin agent combination therapy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 2014; 30: 431–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strain WD, Blüher M, Paldánius P. Clinical inertia in individualising care for diabetes: is there time to do more in type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Ther 2014; 5: 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gough SC, Bode B, Woo V et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) compared with its components given alone: results of a phase 3, open‐label, randomised, 26‐week, treat‐to‐target trial in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 885–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holst JJ, Buse J, Gough SCL et al. A novel fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide improves postprandial glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from a standardised meal test. Diabetologia 2013; 56: S359. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buse JB, Gough SCL, Rodbard HW et al. Postprandial glycaemic control following a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide compared to each component individually in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2013; 56: S417. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vora J, Bain SC, Damci T et al. Incretin‐based therapy in combination with basal insulin: a promising tactic for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab 2013; 39: 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Balena R, Hensley IE, Miller S, Barnett AH. Combination therapy with GLP‐1 receptor agonists and basal insulin: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15: 485–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File S1. Supplementary material.